94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry, 29 May 2024

Sec. ADHD

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1291096

Background: Recent observational research suggests a potential link between celiac disease (CeD) and an increased incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). However, the genetic relationship between CeD and ADHD remains unclear. In order to assess the potential genetic causality between these two conditions, we conducted a Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis.

Methods: We performed a bidirectional MR analysis to investigate the relationship between CeD and ADHD. We carefully selected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from publicly available large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) databases, employing rigorous quality screening criteria. MR estimates were obtained using four different methods: fixed-effect inverse variance weighted (fe-IVW), random-effect inverse variance weighting (re-IVW), weighted median (WM), and MR-Egger. The robustness and reliability of our findings were confirmed through sensitivity analyses, assessment of instrumental variable (IV) strength (F-statistic), and statistical power calculations.

Results: Our MR analyses did not reveal any significant genetic associations between CeD and ADHD (fe-IVW: OR = 1.003, 95% CI = 0.932–1.079, P = 0.934). Similarly, in the reverse direction analysis, we found no evidence supporting a genetic relationship between ADHD and CeD (fe-IVW: OR = 0.850, 95% CI = 0.591–1.221, P = 0.378). Various MR approaches consistently yielded similar results. Sensitivity analysis indicated the absence of significant horizontal pleiotropy or heterogeneity. However, it’s important to note that the limited statistical power of our study may have constrained the causal analysis of the exposure’s influence on the outcome.

Conclusions: Our findings do not provide compelling evidence for a genetic association between CeD and ADHD within the European population. While the statistical power of our study was limited, future MR research could benefit from larger-scale datasets or datasets involving similar traits. To validate our results in real-world scenarios, further mechanistic studies, large-sample investigations, multicenter collaborations, and longitudinal studies are warranted.

Celiac disease (CeD) is an immunological disorder triggered by the consumption of gluten in genetically susceptible individuals (1). Reports suggest that CeD affects approximately 1% of individuals in most populations; however, a significant number of patients remain undiagnosed (1, 2). CeD is a lifetime illness that can manifest at any age (3). It represents a systemic ailment characterized by a complex pathophysiology and diverse clinical presentations. These include not only common nonspecific symptoms like bloating, vomiting, and abdominal pain but also typical gastrointestinal manifestations such as chronic diarrhea and weight loss. Moreover, a wide array of symptoms affecting multiple organs constitute its extra-intestinal presentations (4). Notably, many foods contain the gluten that causes celiac disease (5), and some commonly used food additives (like monosodium glutamate) are also derived from gluten (6, 7). As a result, food contamination with gluten is a common issue, making the issues related to celiac disease all the more critical to consider.

Untreated CeD patients exhibit a prevalence of psychiatric disorders of up to 21% (4). However, the precise mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology and development of behavioral and mental disorders associated with CeD remain a mystery. One hypothesis suggests that the ingestion of gluten and its subsequent breakdown into immunogenic peptides may lead to the leakage of these peptides through the intestinal wall. Subsequently, these peptides could breach the blood-brain barrier, potentially triggering mild brain inflammation (4). These immune pathways may play a role in influencing the development and manifestation of ADHD (8–10).

ADHD, a neurological condition characterized by age-inappropriate levels of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity, coupled with functional impairments across various settings, often endures from childhood into adolescence and adulthood (11). Globally, the prevalence of ADHD in individuals under the age of 18 is approximately 5% (12), and over the past three decades, this prevalence has remained stable (13). In recent years, the relationship between ADHD and CeD has garnered significant attention. Several case-control studies have shown no significant difference between individuals with celiac disease (CeD) and control groups concerning the prevalence of ADHD or ADHD-like symptoms (14, 15). Conversely, contrasting findings have been reported in other studies, indicating a notably higher incidence of ADHD among individuals with CeD compared to control groups (16–18). Consequently, the correlation between CeD and ADHD warrants further comprehensive investigation.

Mendelian randomization (MR) is a robust statistical method that employs genetic variables as instrumental variables to discern the genetic relationship between an exposure and an outcome (19). Given the stability of genes post-fertilization, MR analysis is particularly effective in mitigating reverse causality issues (20). Additionally, MR analysis can help mitigate confounding effects by randomly allocating alleles (21). In our study, we investigated the potential association between CeD and ADHD utilizing publicly available large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) datasets through a two-sample bidirectional MR analysis.

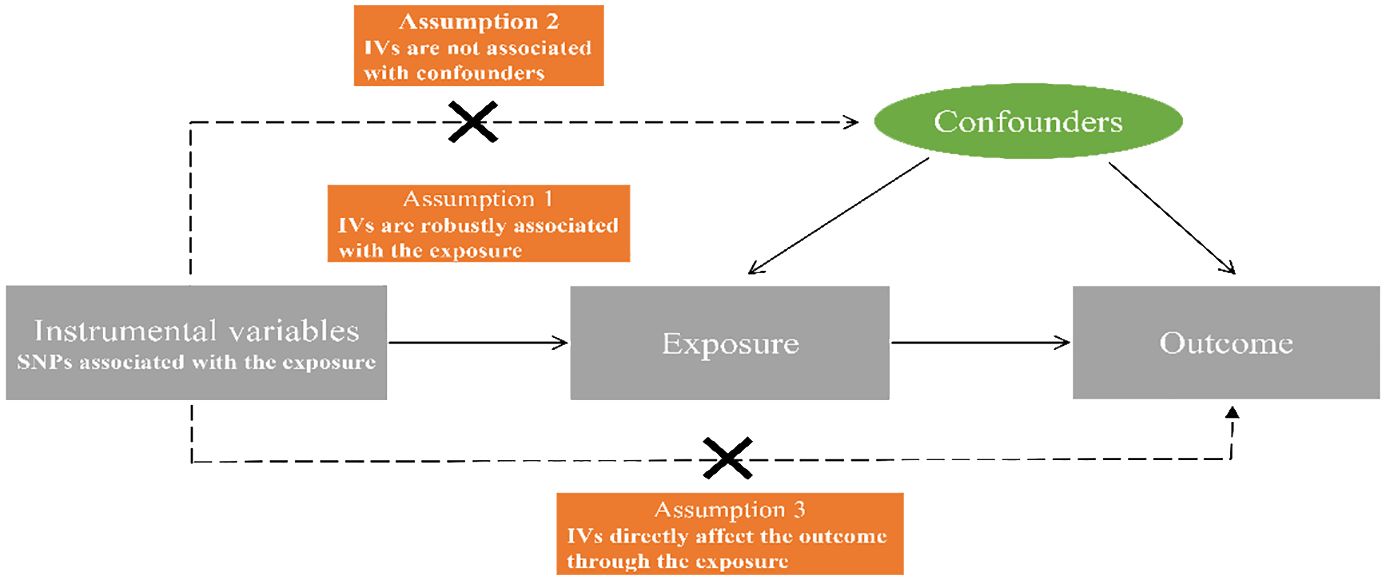

In MR research, three crucial assumptions (22) must be satisfied by the instrumental variables (IVs), as illustrated in Figure 1: (1) IVs should exhibit a significant correlation with the exposure; (2) IVs should remain unconfounded in the relationship between exposure and outcome; (3) IVs should not exert any influence on the outcome through mechanisms other than the exposure itself.

Figure 1 Diagrammatic representation of the Mendelian randomization analysis’s underlying assumptions. SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms; IVs, instrumental variables.

Our study placed a high priority on using the most recent Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) data from published studies or readily accessible GWAS statistics. For CeD, we sourced summary statistics from the MR-base platform (23), a resource developed by Trynka et al. (24) (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/ieu-a-1058/). Regarding Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), we obtained GWAS data from a meta-analysis published within the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium’s dataset (https://pgc.unc.edu/) (25). However, in our attempts to conduct a reverse Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to explore the relationship between ADHD (exposure) and CeD (outcome), our instrumental variables (IVs) failed to extract relevant information for the outcome variable. Consequently, we switched to another GWAS database for celiac disease, provided by Dubois et al. (26) (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/ieu-a-276/). Detailed data can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

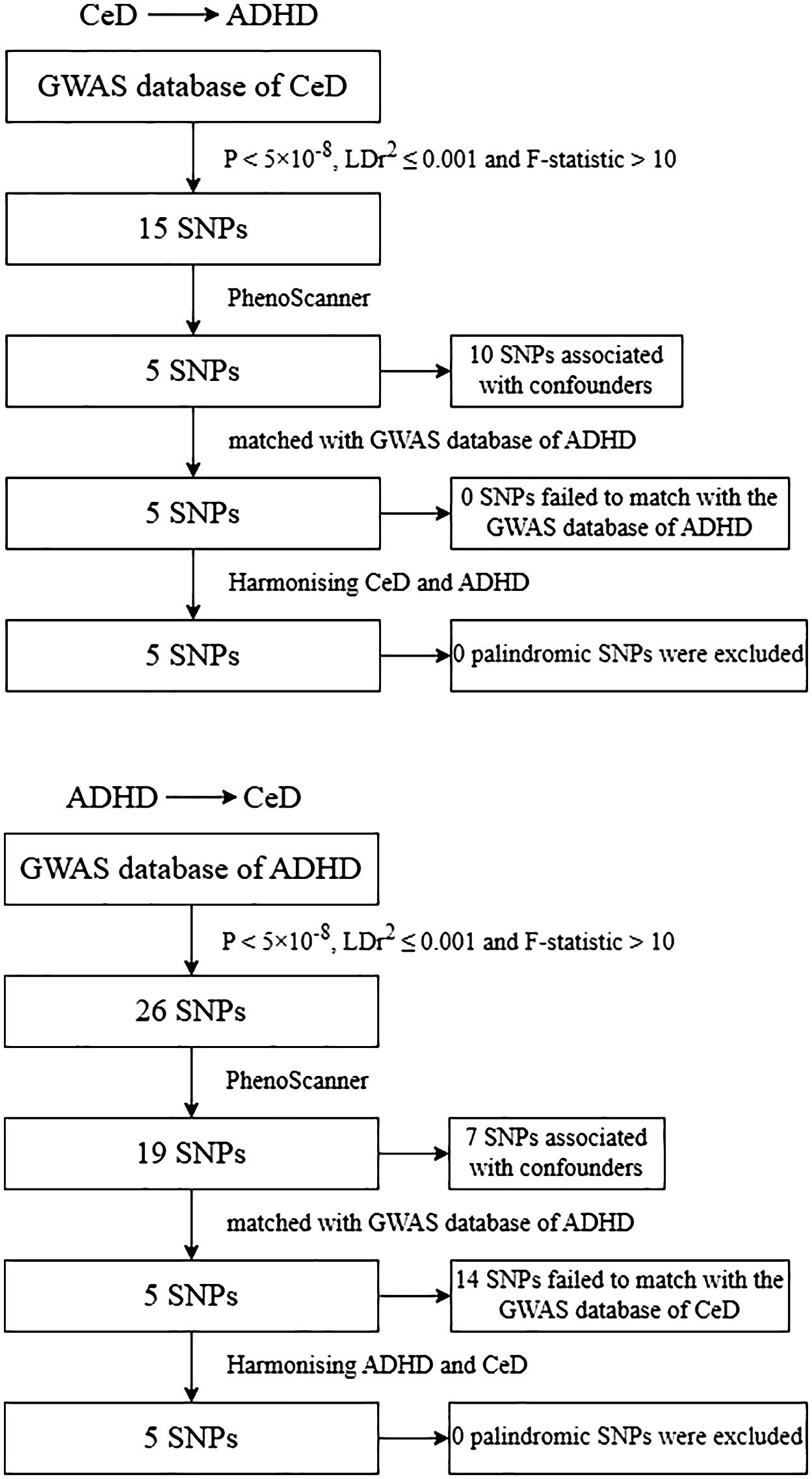

The genetic instrument’s production and analysis process is illustrated in Figure 2. Initially, we employed the genome-wide significance criterion (P<5 ×10− 8) to identify SNPs and subsequently filtered out highly correlated variants with to mitigate linkage disequilibrium (LD) within a 10,000KB range (27, 28). For each IV, we assessed its strength using the F-statistic of SNPs, calculated as follows: , where represents the proportion of variance in the exposure explained by the genetic instrument, and N signifies the sample size (29). A recommended F-statistic threshold of greater than 10 was utilized to ensure the use of robust genetic instruments (29). R2 for the SNP instrument was determined using the formula: , with EAF representing the effect allele frequency and beta indicating the estimated genetic effect on exposure (30). We employed PhenoScanner V2 (www.phenoscanner.medschl.cam.ac.uk) (31) and previous MR studies (32–35) to exclude SNPs associated with potential confounding factors. In the final stage, certain SNPs were excluded either due to their lack of correspondence with data in the GWAS outcome database or the presence of palindromic structures.

Figure 2 Flowchart of the genetic instruments’ generating and analysis. CeD, celiac disease; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism. GWAS, genome‐wide association studies.

We employed four distinct methods to assess the Mendelian Randomization (MR) estimates for the relationship between CeD and ADHD: fixed effect inverse variance weighting (fe-IVW), random effect inverse variance weighting (re-IVW), weighted median (WM), and MR-Egger. The primary statistical model used for aggregating SNP-specific Wald-ratio estimates was fe-IVW (36). This traditional MR method yields robust results when all instrumental variables (IVs) are valid and free from pleiotropic effects (37). In cases with substantial heterogeneity among SNPs, the IVW in the random effects model can provide more dependable estimates (38). The presence of pleiotropy in MR studies can introduce bias and render MR estimates unstable (39). Consequently, as supplementary MR estimations, we applied MR-Egger and WM. The MR-Egger analysis includes an intercept test to detect horizontal pleiotropy (40). Even in the presence of pleiotropic IVs, the MR-Egger technique offers a cautious assessment of causal effects, with resulting statistics resistant to exaggeration (41). The WM method accommodates the possibility of up to 50% of the variables in the SNPs being non-valid instrumental variables (42), allowing for a consistent evaluation of causal effects.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to ensure the reliability of our MR results. In our study, we employed Cochran’s Q statistic (P< 0.05) to identify significant heterogeneity among the estimates of each included SNP (43). Indications of horizontal pleiotropy were evaluated through the MR-Egger regression’s intercept (P< 0.05, suggesting potential horizontal pleiotropy). Likewise, MR-Pleiotropy Residual Sum and Outlier methods (MR-PRESSO) were employed to find outliers and possible horizontal pleiotropy (global test P< 0.05 implies the presence of horizontal pleiotropy) (44). If outliers were detected, they were excluded to obtain a more accurate corrected estimate (44). In addition, the stability of MR estimates after the exclusion of the particular SNP was assessed using the leave-one-out method (45).

In an effort to rule out the possibility of reverse causality, we also changed the outcome and exposure and reran the MR and sensitivity analyses. The R packages “Two Sample MR” and “MR-PRESSO” were used for MR analysis, and R version 4.2.1 was utilized for all studies. Using the online calculator (https://cnsgenomics.shinyapps.io/mRnd/) (46), power calculations were done using the outcome sample size, proportion of cases, R2 sum, and a type I error rate of 0.05.

Following a rigorous process for identifying suitable instrumental variables (IVs), we identified 5 SNPs strongly associated with CeD to serve as IVs in our Mendelian Randomization (MR) analysis. These selected SNPs collectively account for 3.24 percent of the variance in CeD across the population. Their F-statistics, presented in Supplementary Table 2, ranged from 123.78 to 233.67. The MR results, as detailed in Supplementary Table 3, indicate that based on the fe-IVW analysis, no statistically significant causal relationship between CeD and the risk of ADHD was observed (OR = 1.003, 95% CI = 0.932–1.079, P = 0.934). Similarly, the re-IVW (OR = 1.003, 95% CI = 0.909–1.107, P = 0.951), MR-Egger (OR = 1.337, 95% CI = 0.719–2.486, P = 0.426), and WM method (OR = 1.001, 95% CI = 0.903–1.109, P = 0.985) yielded consistent results. Furthermore, Cochran’s Q statistic did not reveal significant heterogeneity in estimating the included SNPs (P = 0.129), and leave-one-out analysis confirmed the stability of our MR estimations (Supplementary Figure 1B). The MR-Egger intercept of -0.038 (P = 0.425), as shown in Supplementary Table 3, indicates no apparent horizontal pleiotropy. Using MR-PRESSO, no significant horizontal pleiotropy was detected (global test P = 0.179), and our sample exhibited no outliers (Supplementary Table 3). However, it is important to note that our study had limited statistical power, with only 5.00% power to detect an association between ADHD and the IVs of CeD (Supplementary Table 4).

In the reverse MR analysis, 5 SNPs were utilized as IVs for ADHD and collectively accounted for 1.04% of the phenotypic variation. The F-statistics ranged from 331.86 to 810.67, all of which exceeded 10, indicating the absence of weak instrument bias (Supplementary Table 2). The results presented in Supplementary Table 3 revealed no significant causal relationship between ADHD and CeD when employing various methods, including fe-IVW (OR = 0.850, 95% CI = 0.591–1.221, P = 0.378), re-IVW (OR = 0.850, 95% CI = 0.489–1.476, P = 0.563), MR-Egger (OR = 0.162, 95% CI = 0.018–1.485, P = 0.206), and the WM method (OR = 0.955, 95% CI = 0.565–1.613, P = 0.862). Meanwhile, Cochran’s Q test did not indicate any noteworthy heterogeneity (P = 0.45). A leave-one-out analysis did not identify any single SNP significantly influencing our MR estimates (Supplementary Figure 2B). The MR-Egger intercept was 0.0019 (P = 0.054), indicating the absence of detectable horizontal pleiotropy (Supplementary Table 3). In the MR-PRESSO examination, no significant horizontal pleiotropy or outliers were detected (global test P = 0.097). It is worth noting that the power to detect the association between CeD and the IVs of ADHD was modest, at 15.00% (Supplementary Table 4). For a visual representation of our study data, please refer to the forest plots, leave-one-out plots, scatterplots, and funnel plots displayed in Supplementary Figures 1, 2.

Our results clearly demonstrate that there is no significant link between CeD and an increased risk of developing ADHD. Moreover, the evidence supporting a causal connection between CeD risk and the occurrence of ADHD is scant. Nevertheless, it’s important to acknowledge that the precision of these findings might be somewhat diminished due to constraints in statistical power.

In 2015, a systematic review delved into the ongoing debate surrounding the potential link between CeD and ADHD. Intriguingly, its conclusions diverged from the consensus, finding no apparent correlation (47). But up until now, prior to this review, numerous observational studies had put forth compelling evidence demonstrating a substantial association between CeD and ADHD. A population-based study, after accounting for factors such as country of birth, parental education, birth weight, Apgar score, and psychiatric history, found that children with celiac disease had a 1.2-fold higher risk of ADHD compared to the general population (95% CI: 1.0–1.4) (48). In a substantial prospective cohort study, individuals with CeD had a higher ADHD risk compared to matched counterparts (HR = 1.19, 95% CI: 0.99–1.42). Stratified analyses by sex, age, calendar year, and follow-up time further confirmed this elevated risk (18). The findings from a meta-analysis lent further weight to these observations (16). On the other hand, in some other observational studies, the prevalence of celiac disease in populations with ADHD does not seem to be significantly different from that in control populations, and the findings do not support the view that CeD is more common in kids with ADHD than in kids without the disorder (49).

Our conclusion diverges from previous observational studies due to several critical factors: (i) The MR analysis approach carefully selects appropriate genetic variations (SNPs) as instrumental variables, leveraging GWAS databases to effectively mitigate the influence of confounding factors such as lifestyle and social environment on disease outcomes. CeD treatment solely involves a lifelong gluten-free diet (GFD) (50), but an imbalanced GFD can elevate the risk of obesity (51). An MR analysis has highlighted a positive causal link between obesity and a higher risk of ADHD (52). (ii) Since studies have demonstrated how DNA methylation or copy number variants can independently alter the risks of AD or ADHD, it is possible that the genetic relationship between the two could be mediated by epigenetic changes in copy number variations (53–56). (iii) Our study benefits from a large sample size in the MR analysis, enhancing its persuasiveness compared to earlier observational studies with smaller samples. Moreover, previous studies relied on cohort designs, which were relatively simplistic and lacked the ability to differentiate between causality and chronological order and were often constrained by geographical limitations. (iv) The disparities in our study findings compared to previous research linking CeD and ADHD may stem from differences in population inclusion and diagnostic criteria for the disease. Our study encompassed a broad spectrum of European countries, incorporating various European ethnic groups, whereas previous studies often focused on large cohorts within a single country or non-European populations (17, 18, 57). Furthermore, the GWAS database we used for our research followed strict guidelines for selecting case samples. For instance, in the case of CeD, diagnostic information encompassed not only clinical symptomatology and serological markers but also histopathological identification (24, 26). On the other hand, some past studies might have just used quick diagnostic tests for CeD in the absence of such thorough diagnostic protocols (57, 58).

Our research boasts several distinct advantages. Firstly, it represents the pioneering use of Mendelian randomization to investigate the relationship between CeD and ADHD. Our methodological contribution lies in systematically employing genetic instruments as proxies for modifiable risk factors, thereby enabling us to infer causality and mitigate common biases encountered in traditional observational studies. In addition, we conducted sensitivity tests to ensure the robustness of our final results. Secondly, we conducted bidirectional Mendelian randomization analyses, a valuable approach for examining potential reverse causal associations and enhancing the stability and reliability of our findings.

However, this study has several limitations that should be taken into consideration. Firstly, addressing epigenetic factors such as DNA methylation, non-coding RNA regulation, and chromatin remodeling poses challenges in MR studies (43). Secondly, the phenomenon known as the winner’s curse could potentially inflate the genetic associations between exposure and outcome (59). To mitigate this bias, we employed four different MR methods to assess the MR estimates. Fortunately, these methods yielded consistent results, indicating that the winner’s curse only marginally affected our MR analysis. Thirdly, the statistical power of our primary analyses fell below the recommended threshold of 80%. This could be attributed to the limited variability in exposure explained by the chosen instrumental variables (37). Hence, caution should be exercised when interpreting the findings. Fourthly, the majority of individuals in the analyzed databases had European ancestry, limiting the generalizability of our findings to populations with more diverse ethnic backgrounds. Lastly, our ability to conduct additional subgroup analyses was constrained due to the unavailability of complete demographic and clinical data. Specifically, as ADHD is more prevalent in males, the lack of gender-stratified statistics in the database prevented us from assessing the impact of ADHD on the risk of CeD in different age groups and genders (60). This limitation may introduce bias into the study results.

In conclusion, our MR investigation failed to establish a causal link between CeD and ADHD. Furthermore, we did not detect any compelling evidence supporting an association between these two conditions. To bolster future MR studies, we anticipate the availability of more extensive datasets, particularly those encompassing related factors, as the evidence in our study was hampered by its limited statistical power. To validate our findings in a practical context, additional mechanistic research, alongside large-scale, multicenter, and longitudinal studies, is imperative.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

JC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. QZ: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. LL: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZX: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Our research was supported by Traditional Chinese Medicine Inheritance and Development Project of Shanghai Medical Innovation & Development Foundation: Construction of Studios of Famous Chinese Medicine Practitioners (Orientation A, No. WLJH2022ZY-GZSA001) and High-level Chinese Medicine Key Discipline Construction Project - Paediatrics of Chinese Medicine (No. B01A2).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1291096/full#supplementary-material

1. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet. (2018) 391:70–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31796-8

2. Hujoel IA, Van Dyke CT, Brantner T, Larson J, King KS, Sharma A, et al. Natural history and clinical detection of undiagnosed coeliac disease in a North American community. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2018) 47:1358–66. doi: 10.1111/apt.14625

3. Hill ID, Dirks MH, Liptak GS, Colletti RB, Fasano A, Guandalini S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2005) 40:1–19. doi: 10.1002/j.1536-4801.2005.tb00917.x

4. Hallert C, Astrom J, Sedvall G. Psychic disturbances in adult coeliac disease. III. Reduced central monoamine metabolism and signs of depression. Scand J Gastroenterol. (1982) 17:25–8. doi: 10.3109/00365528209181039

5. Akhondi H, Ross AB. Gluten-Associated Medical Problems. Treasure Island (FL: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC (2024). StatPearls.

6. Subramanian A, Tamilanban T, Sekar M, Begum MY, Atiya A, Ramachawolran G, et al. Neuroprotective potential of Marsilea quadrifolia Linn against monosodium glutamate-induced excitotoxicity in rats. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1212376. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1212376

7. Tonouchi N, Ito H. Present global situation of amino acids in industry. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. (2017) 159:3–14. doi: 10.1007/10_2016_23

8. Terrone G, Parente I, Romano A, Auricchio R, Greco L, Del Giudice E. The Pediatric Symptom Checklist as screening tool for neurological and psychosocial problems in a paediatric cohort of patients with coeliac disease. Acta paediatrica (Oslo Norway: 1992). (2013) 102:e325–8. doi: 10.1111/apa.12239

9. Verlaet AA, Noriega DB, Hermans N, Savelkoul HF. Nutrition, immunological mechanisms and dietary immunomodulation in ADHD. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2014) 23:519–29. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0522-2

10. Esparham A, Evans RG, Wagner LE, Drisko JA. Pediatric integrative medicine approaches to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Children (Basel). (2014) 1:186–207. doi: 10.3390/children1020186

11. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publisher (2013).

12. Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. (2014) 43:434–42. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt261

13. Sayal K, Prasad V, Daley D, Ford T, Coghill D. ADHD in children and young people: prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. Lancet Psychiatry. (2018) 5:175–86. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30167-0

14. Ruggieri M, Incorpora G, Polizzi A, Parano E, Spina M, Pavone P. Low prevalence of neurologic and psychiatric manifestations in children with gluten sensitivity. J pediatrics. (2008) 152:244–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.06.042

15. Walters K, Rubenstein J, Holevinski L, Kao J. The prevalence of ADHD in adults and children previously diagnosed with celiac disease: A hospital-based study. Gastroenterology. (2013) 144:S–251. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(13)60891-4

16. Clappison E, Hadjivassiliou M, Zis P. Psychiatric manifestations of coeliac disease, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. (2020) 12:142. doi: 10.3390/nu12010142

17. Lebwohl B, Haggard L, Emilsson L, Soderling J, Roelstraete B, Butwicka A, et al. Psychiatric disorders in patients with a diagnosis of celiac disease during childhood from 1973 to 2016. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2021) 19:2093–101 e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.018

18. Hansen S, Osler M, Thysen SM, Rumessen JJ, Linneberg A, Karhus LL. Celiac disease and risk of neuropsychiatric disorders: A nationwide cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2023) 148:60–70. doi: 10.1111/acps.13554

19. Emdin CA, Khera AV, Kathiresan S. Mendelian randomization. JAMA. (2017) 318:1925–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17219

20. Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet. (2014) 23:R89–98. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu328

21. Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Mendelian randomization: prospects, potentials, and limitations. Int J Epidemiol. (2004) 33:30–42. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh132

22. Boef AG, Dekkers OM, le Cessie S. Mendelian randomization studies: a review of the approaches used and the quality of reporting. Int J Epidemiol. (2015) 44:496–511. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv071

23. Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, Wade KH, Haberland V, Baird D, et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife. (2018) 7:e34408. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34408

24. Trynka G, Hunt KA, Bockett NA, Romanos J, Mistry V, Szperl A, et al. Dense genotyping identifies and localizes multiple common and rare variant association signals in celiac disease. Nat Genet. (2011) 43:1193–201. doi: 10.1038/ng.998

25. Demontis D, Walters GB, Athanasiadis G, Walters R, Therrien K, Nielsen TT, et al. Genome-wide analyses of ADHD identify 27 risk loci, refine the genetic architecture and implicate several cognitive domains. Nat Genet. (2023) 55:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2022.07.018

26. Dubois PC, Trynka G, Franke L, Hunt KA, Romanos J, Curtotti A, et al. Multiple common variants for celiac disease influencing immune gene expression. Nat Genet. (2010) 42:295–302. doi: 10.1038/ng.543

27. Savage JE, Jansen PR, Stringer S, Watanabe K, Bryois J, de Leeuw CA, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nat Genet. (2018) 50:912–9. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0152-6

28. Park S, Lee S, Kim Y, Cho S, Kim K, Kim YC, et al. Causal effects of atrial fibrillation on brain white and gray matter volume: a Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med. (2021) 19:274. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02152-9

29. Burgess S, Thompson SG, Collaboration CCG. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol. (2011) 40:755–64. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr036

30. Papadimitriou N, Dimou N, Tsilidis KK, Banbury B, Martin RM, Lewis SJ, et al. Physical activity and risks of breast and colorectal cancer: a Mendelian randomisation analysis. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:597. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14389-8

31. Kamat MA, Blackshaw JA, Young R, Surendran P, Burgess S, Danesh J, et al. PhenoScanner V2: an expanded tool for searching human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics. (2019) 35:4851–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz469

32. Riglin L, Stergiakouli E. Mendelian randomisation studies of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. JCPP Adv. (2022) 2:e12117. doi: 10.1002/jcv2.12117

33. Leppert B, Riglin L, Wootton RE, Dardani C, Thapar A, Staley JR, et al. The effect of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder on physical health outcomes: A 2-sample mendelian randomization study. Am J Epidemiol. (2021) 190:1047–55. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa273

34. A G, Sun C, Shan Y, Husile H, Bai H. Bidirectional causal link between inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease: A two-sample mendelian randomization analysis. Front Genet. (2022) 13:993492. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.993492

35. Li T, Feng Y, Wang C, Shi T, Huang X, Abuduhadeer M, et al. Causal relationships between autoimmune diseases and celiac disease: A Mendelian randomization analysis. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. (2023) 23:1–16. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2023.2215039

36. Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. (2013) 37:658–65. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21758

37. Chen H, Chen S, Ye H, Guo X. Protective effects of circulating TIMP3 on coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction: A mendelian randomization study. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. (2022) 9:277. doi: 10.3390/jcdd9080277

38. Bowden J, Del Greco MF, Minelli C, Davey Smith G, Sheehan N, Thompson J. A framework for the investigation of pleiotropy in two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization. Stat Med. (2017) 36:1783–802. doi: 10.1002/sim.7221

39. Hartwig FP, Davies NM, Hemani G, Davey Smith G. Two-sample Mendelian randomization: avoiding the downsides of a powerful, widely applicable but potentially fallible technique. Int J Epidemiol. (2016) 45:1717–26. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx028

40. Bowden J, Del Greco MF, Minelli C, Davey Smith G, Sheehan NA, Thompson JR. Assessing the suitability of summary data for two-sample Mendelian randomization analyses using MR-Egger regression: the role of the I2 statistic. Int J Epidemiol. (2016) 45:1961–74. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw220

41. Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol. (2017) 32:377–89. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0255-x

42. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. (2016) 40:304–14. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21965

43. Gao YF, Jin TY, Chen Y, Ding YH. No causal genetic relationships between atrial fibrillation and vascular dementia: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 10:1071574. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1071574

44. Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. (2018) 50:693–8. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7

45. Kennedy OJ, Pirastu N, Poole R, Fallowfield JA, Hayes PC, Grzeszkowiak EJ, et al. Coffee consumption and kidney function: A mendelian randomization study. Am J Kidney Dis. (2020) 75:753–61. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.08.025

46. Brion MJ, Shakhbazov K, Visscher PM. Calculating statistical power in Mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol. (2013) 42:1497–501. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt179

47. Singh P, Arora S, Lal S, Strand TA, Makharia GK. Risk of celiac disease in the first- and second-degree relatives of patients with celiac disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. (2015) 110:1539–48. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.296

48. Butwicka A, Lichtenstein P, Frisén L, Almqvist C, Larsson H, Ludvigsson JF. Celiac disease is associated with childhood psychiatric disorders: A population-based study. J pediatrics. (2017) 184:87–93.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.043

49. Kedem S, Yust-Katz S, Carter D, Levi Z, Kedem R, Dickstein A, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and gastrointestinal morbidity in a large cohort of young adults. World J Gastroenterol. (2020) 26:6626–37. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i42.6626

50. Medza A, Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz A. Nutritional status and metabolism in celiac disease: Narrative review. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:5107. doi: 10.3390/jcm12155107

51. Marciniak M, Szymczak-Tomczak A, Mahadea D, Eder P, Dobrowolska A, Krela-Kazmierczak I. Multidimensional disadvantages of a gluten-free diet in celiac disease: A narrative review. Nutrients. (2021) 13:643. doi: 10.3390/nu13020643

52. Chen W, Feng J, Jiang S, Guo J, Zhang X, Zhang X, et al. Mendelian randomization analyses identify bidirectional causal relationships of obesity with psychiatric disorders. J Affect Disord. (2023) 339:807–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.07.044

53. Mirkovic B, Chagraoui A, Gerardin P, Cohen D. Epigenetics and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: New perspectives? Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:579. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00579

54. Ramos-Quiroga JA, Sanchez-Mora C, Casas M, Garcia-Martinez I, Bosch R, Nogueira M, et al. Genome-wide copy number variation analysis in adult attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder. J Psychiatr Res. (2014) 49:60–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.10.022

55. Fernandez-Jimenez N, Castellanos-Rubio A, Plaza-Izurieta L, Gutierrez G, Castano L, Vitoria JC, et al. Analysis of beta-defensin and Toll-like receptor gene copy number variation in celiac disease. Hum Immunol. (2010) 71:833–6. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.05.012

56. Gnodi E, Meneveri R, Barisani D. Celiac disease: From genetics to epigenetics. World J Gastroenterol. (2022) 28:449–63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i4.449

57. Mohammadi MH, Hesaraki M. Are children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) more likely to develop celiac disease? A prospective study. Postep Psychiatr Neurol. (2023) 32:92–5. doi: 10.5114/ppn.2023.127573

58. Niederhofer H. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and celiac disease: a brief report. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. (2011) 13:PCC.10br01104. doi: 10.4088/PCC.10br01104

59. Jiang T, Gill D, Butterworth AS, Burgess S. An empirical investigation into the impact of winner's curse on estimates from Mendelian randomization. Int J Epidemiol. (2023) 52:1209–19. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyac233

Keywords: celiac disease, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, Mendelian randomization, causality, genetic

Citation: Chen J, Zhu Q, Li L and Xue Z (2024) Celiac disease and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization analysis. Front. Psychiatry 15:1291096. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1291096

Received: 08 September 2023; Accepted: 16 May 2024;

Published: 29 May 2024.

Edited by:

Kyle Williams, Harvard Medical School, United StatesReviewed by:

Tamilanban T, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, IndiaCopyright © 2024 Chen, Zhu, Li and Xue. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zheng Xue, eHVlemhlbmdAc2h1dGNtLmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.