- 1Department of Anxiety Disorders, Shenzhen Mental Health Center, Shenzhen Kangning Hospital, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

- 2Graduate School of Arts & Science, New York University, New York, NY, United States

- 3College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

Objectives: Although sexual minorities have reported higher levels of suicidal ideation than heterosexuals across cultures, the role of various psychosocial factors underlying this disparity among young men has been understudied, particularly in China. This study examined the multiple mediating effects of psychosocial factors between sexual orientation and suicidal ideation in Chinese sexual minority and heterosexual young men.

Methods: 302 Chinese cisgender men who identified as gay or bisexual, and 250 cisgender heterosexual men (n=552, aged 18-39 years) completed an online questionnaire measuring perceived social support, self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation.

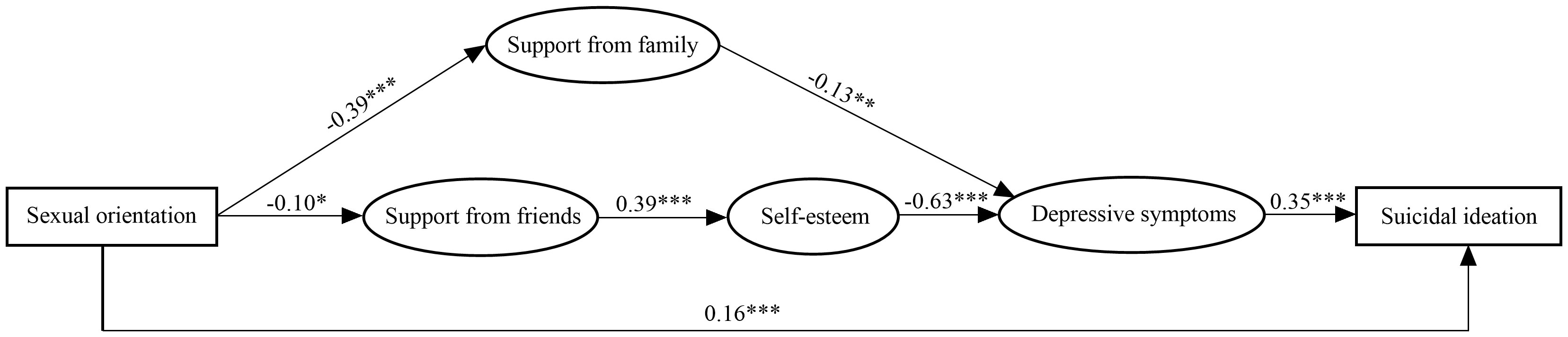

Results: Young sexual minority men reported significantly higher suicidal ideation and lower social support than their heterosexual peers. Structural equation modelling revealed two multiple indirect pathways. One pathway indicated that sexual orientation was indirectly related to suicidal ideation via family support and depressive symptoms. Another pathway indicated that sexual orientation was indirectly related to suicidal ideation via support from friends, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms.

Conclusions: This study is among the first to examine the potentially cascading relationships between sexual orientation and psychosocial factors with suicidal ideation in a Chinese sample of young men. The findings highlight several promising psychosocial targets (i.e., improving family/friend support and increasing self-esteem) for suicide interventions among sexual minority males in China.

Introduction

The mental health challenges faced by individuals in sexual minority groups are becoming an increasingly significant public health issue (1–4). Results from the meta-analysis demonstrated a greater prevalence of depression and suicidality in sexual minority individuals than in heterosexuals in both Western countries and China (5–9). In addition, adverse mental health outcomes are most common among young adults, which could include suicide, the second leading cause of youth death globally (10). Youths with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender (LGBT) identities suffer more psychological distress (11–13). Meyer proposed a minority stress model as the theoretical framework to explain these differences caused by their disadvantaged sexual orientation status (14–16). Hatzenbuehler also proposed a psychological mediation framework and postulated that the mediation effects of social and cognitive processes for sexual minority individuals confer the risk for psychopathology (17). However, most of their theories are based on Western samples, and the associations between sexual orientation and negative mental health outcomes and the potential mechanisms underlying this association in young men are understudied in China.

Moreover, while there is good evidence of poor mental health outcomes and a higher rate of suicidality among sexual minority people, few studies investigate the social determinants of this disparity in China. Thus, the current study has three parts. First, the study will investigate the difference in suicidal ideation between sexual minority and heterosexual young men in China. Second, the study aims to examine the psychosocial factors through which sexual orientation leads to psychopathology (depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation) among Chinese sexual minority young men and heterosexual young men. Finally, the study will explore the role of depressive symptoms in the association between sexual orientation and suicidal ideation.

The mediating effect of social support

In Meyer’s model and social network theory, social support is an essential coping resource and an integral part of the minority stress process (15, 18). Individuals who perceived support from family members, friends, or others tended to be mentally healthier than those who lacked social support (19–22). However, marginalized social groups like sexual minority people are exposed to more stress and receive less social support than their heterosexual counterparts (23, 24). Less social support is associated with higher depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among sexual minority people, as reported in recent cross-sectional studies (22, 25–30). The psychological mediation framework conceptualized social support as a mediator of the stress-psychopathology relationship (17). Although a cross-sectional study discovered a full mediation effect of social support from family in the association between sexual orientation and depressive symptoms (31), there has been less investigation of different sources of support contributing to possible consequences of sexual orientation.

Up to recently, only a few studies examined the impacts of different sources of social support on mental health in LGBT youth. For example, the study by Needham and Austin found that parental support partially mediated the relationship between gay identity and suicidal ideation in gay and heterosexual young adults (32). Additionally, another study indicated that the total score of perceived social support fully mediated sexual orientation victimization and depression among LGB youths (33). Given the essential role of the family in Chinese Confucian culture, it is probable that support from family, friends, and others may have a different impact on the association. The present study wants to determine whether different dimensions of perceived social support account for different mediation effects in the Chinese population on the relationship between sexual orientation and depressive symptoms, which in turn influence suicidal ideation.

The mediating effect of self-esteem

The psychological mediation framework also conceptualized self-esteem as a related cognitive risk factor in developing psychological distress, including suicidality (17). Recent evidence suggests that self-esteem is another critical psychosocial variable indirectly affecting the well-being and psychopathology of the sexual minority population (16, 29, 34, 35). Indeed, low self-esteem is likely to be caused by not receiving enough social support, which in turn confers the risk of psychological problems. Relatedly, former studies demonstrated that insufficient social support was associated with negative self-esteem in the sexual minority group (22, 29). Researchers also identified that self-esteem mediated the relationship between perceived social support and depressive symptoms among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive men who had sex with men in China (36).

Further, a study on sexual minority youth in the United Kingdom showed that depressive symptoms worked as a mediator between self-esteem and suicidal ideation (16). Another study of Chinese LGB individuals also demonstrated that self-esteem mediated the influence of friend support on psychological distress (37). However, to date, no studies have examined the mediating role of self-esteem and different sources of social support in the association between sexual orientation, depression, and suicidal ideation in the Chinese population.

Present investigation

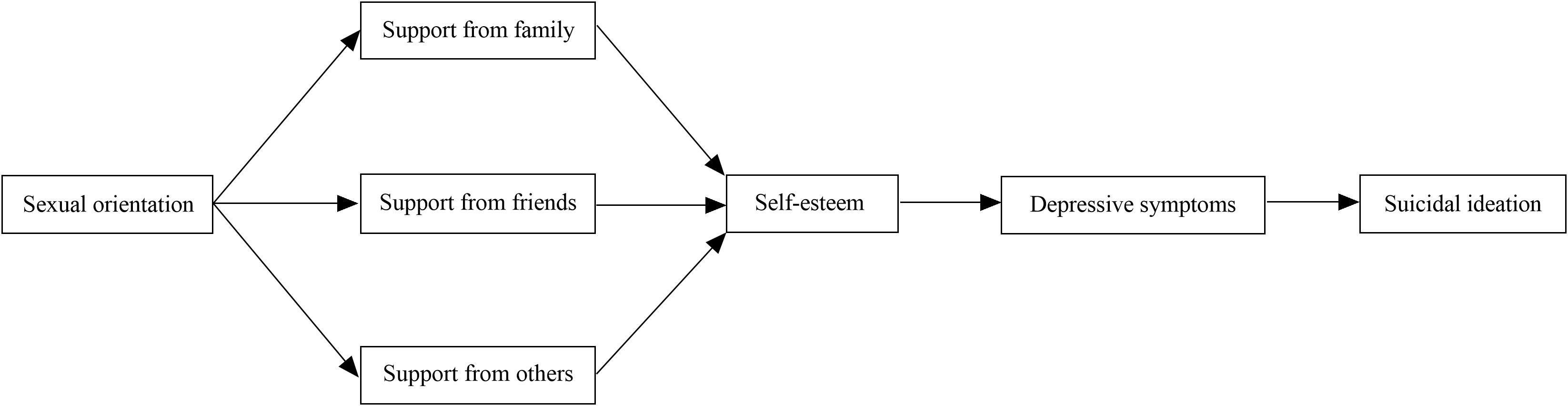

In the current study, we intend to extend previous studies by examining the mediating roles of different sources of perceived social support and self-esteem in the association between sexual orientation and depressive symptoms, consequently affecting suicidal ideation among Chinese young men. None of the research has studied these associations, especially in the Chinese sexual minority population. Since same-sex marriage has not been legalized in China, some Chinese people still discriminate against the sexual minority population (38, 39). Chinese sexual minorities may face more minority stress than the sexual minority group in Western countries. To better understand the psychological well-being of the sexual minority population, the present study proposed a conceptual model to explore the link between sexual orientation and suicidal ideation (shown in Figure 1). Based on prior research and previous findings, this study had three following hypotheses:

(1) Compared to heterosexual men, sexual minority men would perceive less social support, lower self-esteem, more depressive symptoms, and more suicidal ideation.

(2) Sexual orientation (code 1 as heterosexual status and 2 as sexual minority status in the final data analysis) will be positively associated with suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms but negatively correlated with social support and self-esteem.

(3) Perceived social support, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms sequentially mediate the association between sexual orientation and suicidal ideation. Further, different sources of perceived social support may serve different mediating roles in the conceptual model.

Methods

Participants

794 Chinese participants completed the survey, and 552 valid questionnaires were included in the data analysis. Given our focus on sexual minority and heterosexual men, the exclusion criteria (N = 242) were as follows: a. insufficient number of female participants (N = 57); b. missing data on age (N = 69); c. mismatch between biological sex and self-identified gender (N = 93); d. self-reported as unsure of their sexual orientation (N = 2); e. age under 18 or over 40 (N = 21). The final sample consisted of 250 cisgender heterosexual men (who identified themselves as heterosexual) with an age mean, median of 23.89, 23 (SD = 3.98), and 302 cisgender sexual minority men (50 men identified themselves as bisexual, 252 men identified themselves as gay) with an age mean, median of 23.99, 23 (SD = 3.68). Demographic information is presented in Table 1. The dataset can be found in Supplementary Material.

Procedures

The Chinese sexual minority participants were recruited from the LGBT social groups on the following Chinese online platforms: QQ application and douban.com. To maximize the comparability of participants, we recruited heterosexual participants on the same platforms (QQ application and douban.com). These participants were blind as to the comparison but knew the general purpose of the study. Chi-squared analyses and independent t-tests demonstrated no difference between the groups in age, whether only child, education level, occupation, or income. These groups did differ significantly in marital status.

The present study was a cross-sectional online survey approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangning Hospital. All participants needed to fill out the informed consent form before the survey and were informed of the right to withdraw from the survey at any time. After the survey, all participants were compensated with a small reward by Alipay [10 Chinese yuan renminbi (CNY), approximately 1.5 U.S. dollars (USD)].

Measures

Social support. The Chinese version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) was used to examine participants’ perceived social support (40). The MSPSS is a 12-item self-reported scale with three dimensions: family, friend, and others. This is a seven-point Likert scale from 1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree. The average score of the three dimensions presents the participants’ MSPSS score, and a higher MSPSS score indicates a higher perceived social support in family, friends, or others. For the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficient for the MSPSS was 0.92, and for the three subscales: support from family was 0.87, support from friends was 0.89, and support from others was 0.84.

Self-esteem. The Chinese version of the Self-esteem Scale (SES) was used to evaluate participants’ self-esteem levels (41). The questionnaire includes ten items measured on a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. The higher average of the total score suggests a higher level of self-esteem. The Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.88.

Depressive symptoms. The Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to measure participants’ depressive symptoms during the last week (42). The CES-D scale consists of 20 items, rating from 0 = rarely or none of the time to 3 = most or all the time. The total score is 60, and a higher score indicates more severe depressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this measure was 0.90.

Sexual orientation. The participants’ sexual orientation was assessed by the question: “What is your sexual orientation?”. The alternative answers were heterosexual, gay and lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and unsure. Participants who identified themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual were combined and entered as the sexual minority group. Participants who identified themselves as heterosexual were analyzed as the heterosexual group (1= heterosexual, 2 = sexual minority). Two participants who were not sure about their sexual orientation were excluded from the current study. None of the participants identified as transgender.

Suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation was assessed by the question: “Do you have any suicidal thoughts during the past 12 months?”. Participants were asked to rate from three levels: 0 = Never, 1 = Sometimes, and 2 = Often.

Statistical analysis

First, IBM SPSS statistical version 26.0 (IBM Corp) was used to describe demographic information, main variables in sexual minority and heterosexual groups, and main variables inter-correlations. We used independent sample t-tests for continuous variables, Chi-square tests for categorical variables, and Point-biserial for correlations. Second, Mplus 8.3 was used to evaluate the conceptual multiple mediation model by conducting structural equation modeling. The latent variables of support from family, support from friends, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms were indicated by items. Demographics (age, marital status, whether only-one child, education level, occupation, and income) were entered as control variables, and the independent variable sexual orientation was coded as 1= heterosexual and 2 = sexual minority in model testing. Bootstrapping was set at 5000 samples and evaluated the model fit with the following indices: χ2/df ratio (lower than 3), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; lower than 0.08), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI; greater than 0.90), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI; greater than 0.09) (43).

Results

Descriptive and correlation results

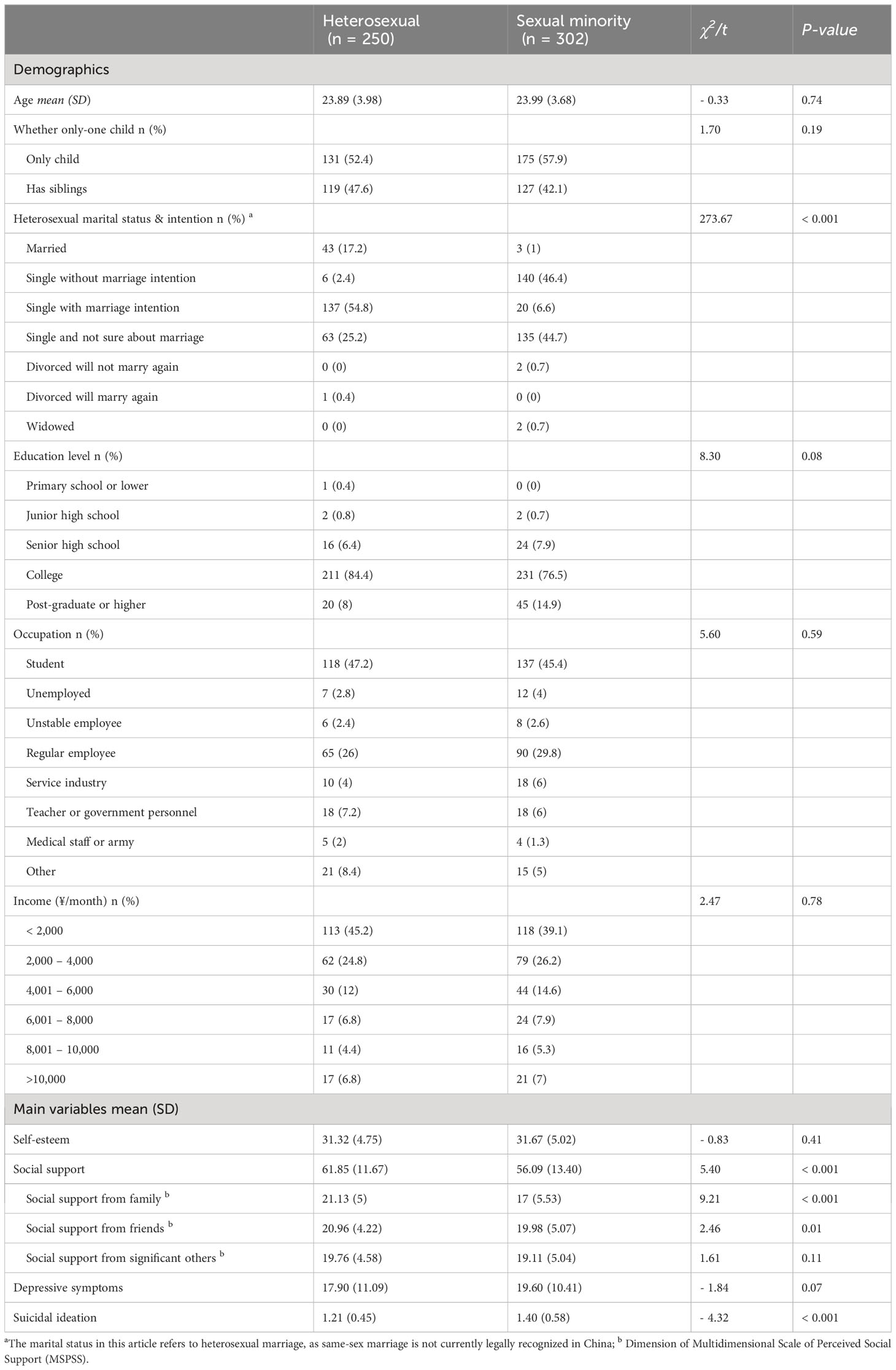

The demographic information and the difference in main variables were summarized in Table 1. The results indicated a significant difference in marital status (χ2 =273.67, p < 0.001) between heterosexual and sexual minority groups. Similar to the previous study, sexual minority participants showed less marriage intention than heterosexual participants in the current study (35). The differences in other demographics were not significant between groups (ps > 0.05). For the key variables, participants in the sexual minority group reported a significantly lower level of social support (t = 5.40, p < 0.001), social support from family (t = 9.21, p < 0.001), social support from friends (t = 2.46, p = 0.01) than heterosexual; and more suicidal ideation (t = - 4.32, p < 0.001) than heterosexual.

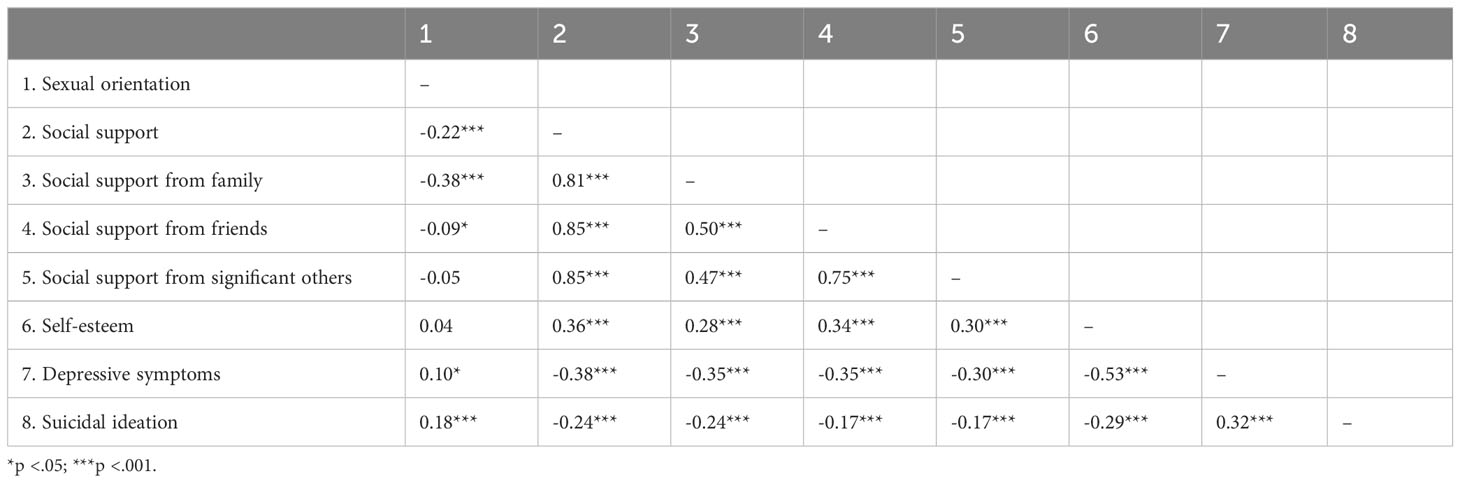

Table 2 shows the intercorrelations of the main variables in all participants. Sexual orientation was negatively correlated with social support (r = - 0.22, p < 0.001), social support from family(r = - 0.38, p < 0.001), and social support from friends (r = - 0.09, p = 0.045); was positively correlated with suicidal ideation (r = 0.18, p < 0.001). Self-esteem was positively correlated with support from family (r = 0.28, p < 0.001) and support from friends (r = 0.34, p < 0.001). Depressive symptoms were positively correlated with suicidal ideation (r = 0.32, p < 0.001); were negatively correlated with self-esteem (r = - 0.53, p < 0.001).

Model testing

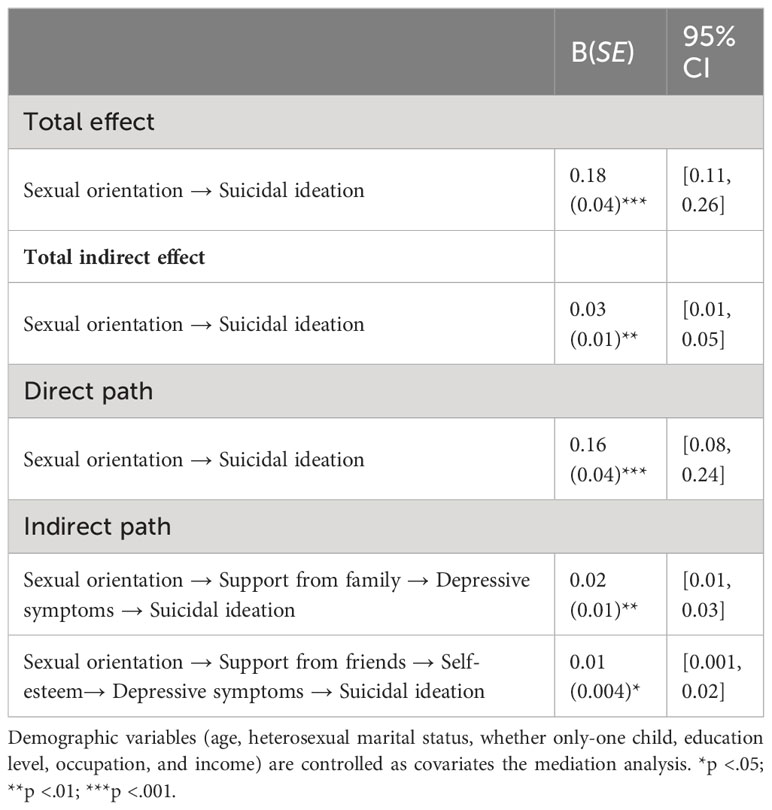

We examined the conceptual multiple multiple mediation model mentioned in the introduction, investigating three possible indirect pathways in the association of sexual orientation and suicidal ideation. The results of the conceptual model suggested that the pathway that included support from others was insignificant (B = 0.002, p = 0.31). Therefore, this pathway was deleted from the final model. We confirmed the final structural model (Figure 2), including two indirect pathways and a direct pathway, and all indices indicate good model fit: χ2/df = 2.06, RMSEA = 0.04, TLI = 0.90, CFI = 0.91. The parameter estimate of the final model is presented in Table 3. The direct effect of sexual orientation and suicidal ideation was 0.18 (95% CI = 0.11, 0.26), and the total indirect effect was 0.03 (95% CI = 0.01, 0.05). The model revealed that sexual orientation (identifying as 1 = heterosexual or 2 = sexual minority) was negatively related to support from family (B = - 0.39, p < 0.001) and support from friends (B = - 0.10, p = 0.03). Support from friends (B = 0.39, p < 0.001) was positively related to self-esteem. Both self-esteem (B = - 0.63, p < 0.001) and support from family (B = - 0.13, p = 0.004) were negatively related to depressive symptoms. More depressive symptoms predicted more suicidal ideation (B = 0.35, p < 0.001).

Figure 2 Path diagram for the relationship between sexual orientation and suicidal ideation. Coefficients are standardized and adjusted for age, education, occupation, marital status, income, and whether only-one child. Note. Support from family and Support from friends are the two dimensions of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). Self-esteem presents the Chinese version of the Self-esteem Scale (SES); Depressive symptoms present the Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D). Latent variables (enclosed in oval-shaped frames) are measured by the observable variables (scale items). Note. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Discussion

Using a sample of sexual minority and heterosexual young men in mainland China, this study was one of the first to examine the multiple mediating roles of different sources of social support, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms in the association between sexual orientation and suicidal ideation. We found two mediating pathways for the association. One pathway indicated that Chinese sexual minority men endorsed less family support in their social networks, which mediated the relationship between sexual orientation and depressive symptoms, resulting in more suicidal ideation. Another pathway indicated that lower friend support in Chinese sexual minority young men led to lower self-esteem than in heterosexuals, which in turn predicted depressive symptoms and accounted for more suicidal ideation. These results created a path model linking sexual orientation to suicidal ideation through a series of psychosocial factors for Chinese young men.

Consistent with previous studies, our findings showed that sexual minority young men reported significantly less social support, marginally more depressive symptoms, and more suicidal ideation compared to heterosexual men (7–9, 44). The mediation analysis conducted in this study uncovered significant chain mediating effects of social support, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms on the association between sexual orientation and suicidal ideation. It is important to note that only support from family and friends contributed to the mediation effect in the association but not support from others. Unlike previous western studies unveiling the mediation effect of the total score of social support or only the score of family support, our results showed that family support and friends’ support are prominent protective factors in Chinese sexual minority young men (32, 33). Individuals with lower family support and friends’ support may face more challenges and become more vulnerable to depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation (35, 45, 46). An explanation that can account for these results may be that in Asian culture, sexual minority youth were more likely to rely more on family and friends’ support rather than support from others.

Notably, self-esteem only mediated support from friends but not support from family. Given that peers play an important part in young adult life, peer support can increase people’s self-esteem and sense of control (47). Chinese sexual minority young men with a lower level of support from friends experienced lower self-esteem, which was associated with more depressive symptoms and more suicidal ideation. Altogether, young sexual minority men in China lacking family support and peer support may be particularly vulnerable to self-esteem and at risk for depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation.

Limitations

Several limitations to the current study should be acknowledged. First, the study was cross-sectional, which could not make causal inferences. Longitudinal methodologies are needed to verify the causality. In addition, we only studied homosexual and bisexual cisgender men as the sexual minority group. It is unknown whether this conclusion can be generalized to lesbian groups, asexuals, or transgender. Finally, due to the difficulty of collecting data from special social groups, our sample size may not be large enough to represent sexual minority individuals in China.

Implications

Nevertheless, the results of the current study may have important implications. First, these findings contribute to the literature on suicidality among Chinese sexual minority young men and may promote the development of interventions for high-risk individuals. Second, interventions to prevent adverse mental health outcomes by enhancing family and friend support may yield better outcomes. Third, self-esteem and perceived family and friend support may be valuable measures for psychological counseling of sexual minority youth at risk for depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. Finally, LGBTQ+ movements, such as independent pride events for sexual minority groups in China, are needed to promote self-esteem.

Conclusions

These results showed that different sources of social support explained different pathways in the development of suicidal ideation among Chinese sexual minority men. First, family support mediated the relationship between sexual orientation, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation. In contrast, friend support mediated the relationship between sexual orientation and self-esteem, which in turn conferred risk for depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. They suggest that interventions to reduce suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms among young sexual minority men should focus on enhancing social support from family and friends and promoting their self-esteem in Chinese society.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of Kangning Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YH: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JL: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. GH: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. DZ: Validation, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Youth Foundation Project of Humanities and Social Sciences from Chinese Ministry of Education (No. 22YJC190008) and Shenzhen Fundamental Research Program (No. JCYJ20220530165003007 & No. JCYJ20230807142359032) to JH; and the Shenzhen Fund for Guangdong Provincial High Level Clinical Key Specialties (No. SZGSP013). The current study is part of a research project approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shenzhen Kangning Hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants in this study, without whom this project would not be possible.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1265722/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Huang Y, Li P, Lai Z, Jiax X, Xiao D, Wang T, et al. Association between sexual minority status and suicidal behavior among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. J Affect Disord. (2018) 239:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.004

2. Plöderl M, Tremblay P. Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2015) 27(5):367–85. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949

3. Rentería R, Benjet C, Gutierrez-Garcia RA, Ramírez AA, Albor Y, Borges G, et al. Suicide thought and behaviors, non-suicidal self-injury, and perceived life stress among sexual minority Mexican college students. J Affect Disord. (2021) 281:891–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.038

4. Swannell S, Martin G, Page A. Suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual and heterosexual adults: Findings from an Australian national study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2016) 50(2):145–53. doi: 10.1177/0004867415615949

5. Legleye S, Beck F, Peretti-Watel P, Chau N, Firdion JM. Suicidal ideation among young French adults: Association with occupation, family, sexual activity, personal background and drug use. J Affect Disord. (2010) 123(1–3):108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.10.016

6. Hottes TS, Bogaert L, Rhodes AE, Brennan DJ, Gesink D. Lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among sexual minority adults by study sampling strategies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106(5):e1–e12. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303088

7. Luo Z, Feng T, Fu H, Yang T. Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation among men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. (2017) 17:406. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1575-9

8. Mu H, Li Y, Liu L, Na J, Yu L, Bi X, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for lifetime suicide ideation, plan and attempt in Chinese men who have sex with men. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:117. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0830-9

9. Wei D, Wang X, You X, Luo X, Hao C, Gu J, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and suicide among men who have sex with men in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2020) 29:e136. doi: 10.1017/S2045796020000487

10. Arensman E, Scott V, Leo DD, Pirkis J, et al. Suicide and suicide prevention from a global perspective. Crisis. (2020) 41(Suppl.1):S3–7. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000664

11. Baams L, Grossman AH, Russell ST. Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Dev Psychol. (2015) 51(5):688–96. doi: 10.1037/a0038994

12. Marshal MP, Dermody SS, Cheong J, Cheong JW, Burton CM, Friedman MS, et al. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and suicidality among heterosexual and sexual minority youth. J Youth Adolesc. (2013) 42(8):1243–56. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9970-0

13. Wei C, Liu W. Coming out in Mainland China: A national survey of LGBTQ students. J LGBT Youth. (2019) 16(2):192–219. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2019.1565795

14. Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in Gay men. J Health Soc Behav. (1995) 36(1):38–56. doi: 10.2307/2137286

15. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. (2003) 129(5):674–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

16. Oginni OA, Robinson EJ, Jones A, Rahman Q, Rimes KA, et al. Mediators of increased self-harm and suicidal ideation in sexual minority youth: a longitudinal study. Psychol Med. (2019) 49(15):2524–32. doi: 10.1017/S003329171800346X

17. Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. (2009) 135(5):707–30. doi: 10.1037/a0016441

18. Krause J, Croft DP, James R. Social network theory in the behavioural sciences: potential applications. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. (2007) 62:15–27. doi: 10.1007/s00265-007-0445-8

19. Kessler RC, McLeod JD. Social support and mental health in community samples. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Social support and health. San Francisco: Academic Press. (1985). p. 219–40.

20. De Silva MJ, McKenzie K, Harpham T, Huttly SRA. Social capital and mental illness: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2005) 59(8):619–27. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029678

21. Watson RJ, Grossman AH, Russell ST. Sources of social support and mental health among LGB youth. Youth Soc. (2019) 51(1):30–48. doi: 10.1177/0044118X16660110

22. Wilkerson JM, Schick VR, Romijnders KA, Bauldry J, Butame SA. Social support, depression, self-esteem, and coping among LGBTQ adolescents participating in hatch youth. Health Promot Pract. (2017) 18(3):358–65. doi: 10.1177/1524839916654461

23. Corliss HL, Austin SB, Roberts AL, Molnar BE. Sexual risk in “mostly heterosexual” young women: Influence of social support and caregiver mental health. J Womens Health. (2009) 18(12):2005–10. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1488

24. Frost DM, Meyer IH, Schwartz S. Social support networks among diverse sexual minority populations. Am J Orthopsychiatry. (2016) 86(1):91–102. doi: 10.1037/ort0000117

25. Carter SP, Allred KM, Tucker RP, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Lehavot K, et al. Discrimination and suicidal ideation among transgender veterans: The role of social support and connection. LGBT Health. (2019) 6(2):43–50. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0239

26. Hill RM, Rooney EE, Mooney MA, Kaplow JB. Links between social support, thwarted belongingness, and suicide ideation among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual college students. J Fam Strengths. (2017) 17(2):6. doi: 10.58464/2168-670X.1350

27. Kleiman EM, Riskind JH. Utilized social support and self-esteem mediate the relationship between perceived social support and suicide ideation. A test multiple mediator model. Crisis. (2013) 34(1):42–9. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000159

28. Li R, Cai Y, Wang Y, Sun Z, Zhu C, Tian Y, et al. Psychosocial syndemic associated with increased suicidal ideation among men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China. Health Psychol. (2016) 35(2):148–56. doi: 10.1037/hea0000265

29. McDonald K. Social support and mental health in LGBTQ adolescents: A review of the literature. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2018) 39(1):16–29. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2017.1398283

30. Mustanski B, Liu RT. A longitudinal study of predictors of suicide attempts among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender youth. Arch Sex Behav. (2013) 42(3):437–48. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0013-9

31. Hu J, Tan L, Huang G, Yu W. Disparity in depressive symptoms between heterosexual and sexual minority men in China: The role of social support. PloS One. (2020) 15(1):e0226178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226178

32. Needham BL, Austin EL. Sexual orientation, parental support, and health during the transition to young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. (2010) 39(10):1189–98. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9533-6

33. Chen JK, Hung FN. Sexual orientation victimization and depression among Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual youths in Hong Kong: The mediating role of social support. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2021) 30(5):679–93. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2020.1821853

34. Hu J, Hu J, Huang G, Zheng X. Life satisfaction, self-esteem, and loneliness among LGB adults and heterosexual adults in China. J Homosex. (2016) 63(1):72–86. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1078651

35. Wu C, Chau PH, Choi EPH. Quality of life and mental health of chinese sexual and gender minority women and cisgender heterosexual women: Cross-sectional survey and mediation analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2023) 9:e42203. doi: 10.2196/42203

36. Yan H, Li X, Li J, Wang W, Yang Y, Yao X, et al. Association between perceived HIV stigma, social support, resilience, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms among HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM) in Nanjing, China. AIDS Care. (2019) 31(9):1069–76. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1601677

37. Song C, Pang Y, Wang J, Fu Z. Sources of social support, self-esteem and psychological distress among Chinese Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual people. Int J Sex Health. (2023) 35(1):130–8. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2022.2157920

38. Jeffreys E, Wang P. Pathways to legalizing same-sex marriage in China and Taiwan: globalization and “Chinese values”. In: Winter B, Forest M, Sénac R, editors. Global perspectives on same-sex marriage. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2017). p. 197–219.

39. Wang Y, Miao N, Chang S. Internalized homophobia, self-esteem, social support and depressive symptoms among sexual and gender minority women in Taiwan: An online survey. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2021) 28(4):601–10. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12705

40. Guan NC, Seng LH, Hway Ann AY, Hui KO. Factorial validity and reliability of the Malaysian simplified Chinese version of multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS-SCV) among a group of university students. Asia Pac J Public Health. (2015) 27(2):225–31. doi: 10.1177/1010539513477684

41. Chen F, Bi C, Han M. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the revised-positive version of Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Adv Psychol. (2015) 5(9):531–5. doi: 10.12677/AP.2015.59068

42. Cheung CK, Bagley C. Validating an American scale in Hong Kong: The center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D). J Psychol. (1998) 132(2):169–86. doi: 10.1080/00223989809599157

43. Ullman JB. Structural equation modeling: Reviewing the basics and moving forward. J Pers Assess. (2006) 87(1):35–50. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8701_03

44. Lian Q, Zuo X, Lou C, Gao E, Cheng Y. Sexual orientation and risk factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: A multi-centre cross-sectional study in three Asian cities. J Epidemiol. (2015) 25(2):155–61. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20140084

45. Chang CW, Yuan R, Chen JK. Social support and depression among Chinese adolescents: The mediating roles of self-esteem and self-efficacy. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2018) 88:128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.001

46. Wan LP, Yang XF, Liu BP, Zhang YY, Liu XC, Jia CX, et al. Depressive symptoms as a mediator between perceived social support and suicidal ideation among Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. (2022) 302:234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.061

Keywords: suicidal ideation, Chinese sexual minority, young men, social support sources, self-esteem, depressive symptoms

Citation: Huang Y, Liu J, Huang G, Zhu D, Zhou Y and Hu J (2024) Understanding suicidal ideation disparity between sexual minority and heterosexual Chinese young men: a multiple mediation model of social support sources, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Front. Psychiatry 15:1265722. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1265722

Received: 23 July 2023; Accepted: 23 January 2024;

Published: 15 March 2024.

Edited by:

Yuan Yuan Wang, South China Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Elizabeth Morgan, Springfield College, United StatesYong Cai, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China

Copyright © 2024 Huang, Liu, Huang, Zhu, Zhou and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jingchu Hu, aHVqaW5nY2h1QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; Yunfei Zhou, emhvdXl1bmZlaUBza2gubmV0

Yiting Huang

Yiting Huang Jiayu Liu

Jiayu Liu Gang Huang1

Gang Huang1 Jingchu Hu

Jingchu Hu