- 1Institute for Advanced Consciousness Studies, Santa Monica, CA, United States

- 2Media Lab, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

Introduction

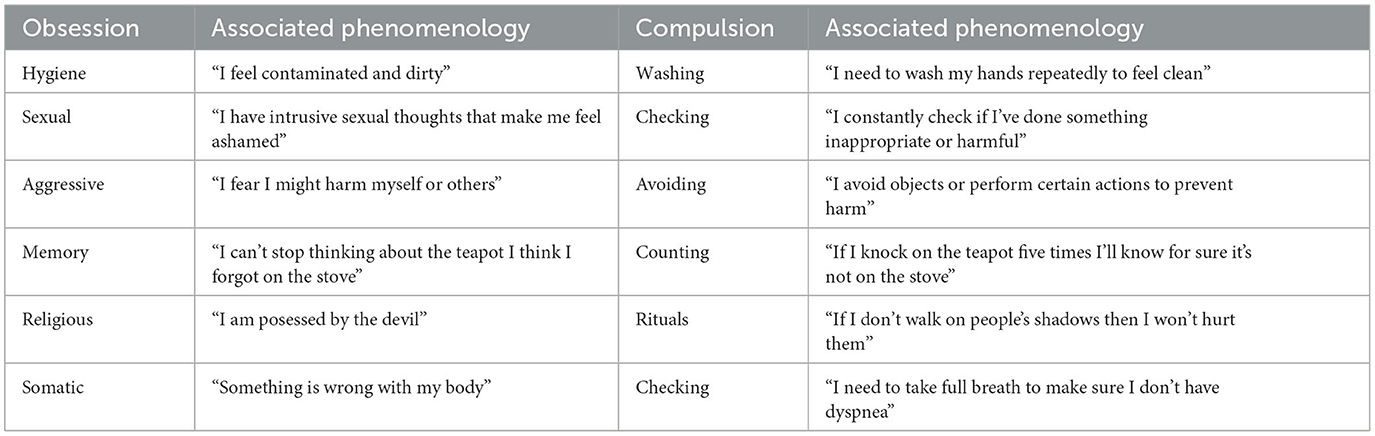

Obessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by distressing, ego-dystonic thoughts (a.k.a., obsessions, O) and repetitive behaviors (a.k.a., compulsions, C) aimed at reducing the anxiety they generate (1). OCD affects 2%−3% of the US population and severely impairs functioning (2). OCD obsessions are characterized by exaggerated doubts disconnected from reality (3). Common themes include contamination (“I may be sick or dirty”), responsibility for harm (“I may harm people or myself”), inability to control thoughts (“I may lose control of my mind”), or being immoral (“I may be a pedophile or evil”). While illogical, doubts persist despite contradictory evidence (4), a source of considerable distress, which clinical diagnosis usually relieves (Table 1). In this short opinion article, we discuss how viewing OCD as pathological self-uncertainty provides novel insights into targeting core cognitive representations for effective treatment. We review converging evidence and provide a unifying framework for understanding OCD that can inform more targeted and effective therapeutic approaches.

A dysfunctional self-model drives OCD

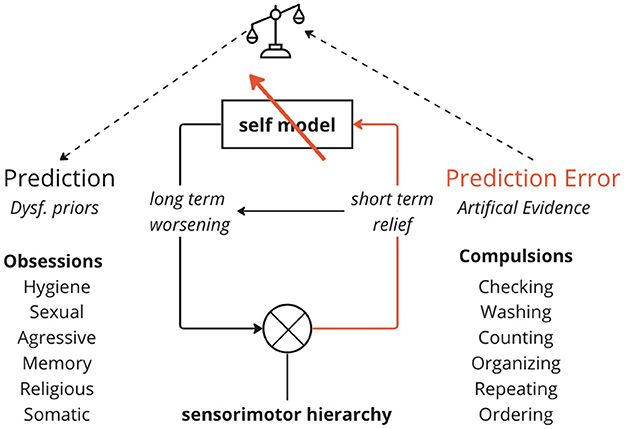

Recent evidence suggest a model of OCD as stemming from flawed high-level priors contained in a dysfunctional self-model (5–13). Here, compulsions are conceptualized as artificially generated evidence to resolve higher order self-uncertainty (Figure 1). The anxiety from negative self-models signifies lost confidence in internal representations and obsessions are a threat to a minimally precise self-concept (9, 14, 15). All things being equal, an uncertain self-model would inevitably skew toward more negative content, since negative experiences are more potent (16) and more difficult to move past than positive ones (17). Deep brain stimulation to the ventral anterior limb of the internal capsule (vALIC), a region associated with self-confidence, rapidly reduced OCD symptoms (18), suggesting this area is critically involved in uncertainty processes that underlie the disorder. Interventions specifically aimed at changing self-perceptions improve cognitive-behavioral treatments for OCD (5, 6, 19). Obsessions likely arise from high-level models encoding dysfunctional assumptions about the self as unreliable or dangerous—a.k.a., the feared self (5, 6, 9, 20). In technical term this amounts to low precision or reliability, a common risk factor for psychopathology (21, 22). The fact that OCD patients feel compelled to perform rituals to reduce anxiety, rather than simply consciously dismissing the obsessional thoughts, suggests that the dysfunctional priors generating the predictions are inaccessible to consciousness. Lacking evidence, OCD patients compulsively create artifical evidence for relief (23).

Figure 1. The self-reinforcing cycle in OCD. A dysfunctional negative self-model generates obsessive doubts and anxiety. Compulsive rituals provide temporary relief of anxiety but ultimately reinforce the negative self-model. Arrows indicate the downward flow of obsessive predictions based on the faulty self-model, and the upward flow of “evidence” from compulsions attempting to disconfirm those predictions. This short-term relief from compulsions perpetuates the cycle long-term, as core beliefs are not addressed. Effective treatment must target the dysfunctional self-representations at the root rather than just surface compulsions.

Hyperactive inference perpetuates pathology

This process is perhaps best captured by the mechanics of active inference—the idea that the brain continuously generates and updates a model of the world using probabilistic, predictive processing (24–26). Active inference involves combining prior beliefs (existing assumptions) with sensory evidence to produce posterior beliefs (updated assumptions) via Bayesian inference (see Figure 1). In OCD, this process becomes pathological when patients assign excessive precision (certainty) to distorted prior beliefs about the self as unpredictable (unreliable, dangerous). In extreme cases, this may lead to the fear of self (6, 27, 28). Self-uncertainty in this context leads to increased volatility in the self-model, opening up the range of more extreme positive or negative beliefs about the self. This produces an overabundance of anxiety-provoking prediction errors signaling mismatch between expectations and observations (29). To reduce this anxiety, patients compulsively engage in exhaustive Bayesian updating, relying on compulsive behaviors to generate new, artificial sensory evidence (observable outcomes of handwashing, counting, checking, etc). However, compulsions cannot provide absolute certainty about the abstract self, fueling renewed doubt. Thus, the relief is only temporary, and in the long term reinforces the negative self-model that something must be wrong with the patient (Figure 1). This is akin to a man trying to bail water out of a ship with a deep rupture in its hull. Each bucket generates temporary relief (“I would not be O if I did C”) but the leak is not being addressed (leading to “D”). Targeting core self-models, not just surface symptoms, is therefore crucial (30, 31).

The roots of self-uncertainty

Changing flawed assumptions about the self, and addressing the self-uncertainty driving pathological doubt may enable lasting improvement and eliminate the compulsive need for constant testing and reassurance (5, 6, 19, 32, 33). But what influences the valence of the self-model in the first place such that it attempts to generate artificial prediction errors to disprove it? Developmental psychology emphasizes that the quality of early bonding with primary caregivers shapes one's internal working models about the self and relationships. Dysfunctional behavioral patterns resulting from suboptimal caregiver interactions can lead to an unstable sense of self (34–36). Ultimately, insecure attachment patterns lead to doubts about one's worth and lovability (37, 38) and the formation of OCD symptoms (39). From the infant's perspective, maternal mirroring provides essential external validation for consolidating a coherent self-concept (40–42). Parents who feel opposed, rejected, and incapable tend to produce children who undervalue themselves (43). As the mother mimics the baby's facial expressions and reflects their emotions—e.g., through exaggerated infant-directed speech (a.k.a., motherese)—the infant learns to associate their inner experience with the mother's attuned external responses (44, 45). Among others, this allows the infant to gain self-awareness, in the process of seing their inner experience mirrored externally (46). This process of mirroring—a.k.a., reflective functioning (47) or attunement (42)—establishes the foundations for secure attachment (35), ultimately allowing mentalization and introspective abilities to unfold (48). Through repeated, predictable mirroring, the infant comes to understand their needs and develop trust that caregivers will be present to attend them and help regulate arousal. The exaggerated self-focus and hyperactive inference characteristic of OCD points to lack of proper mirroring from caregivers to help build realistic, balanced self-representations (40). Early conditioning may explain the development of rigid, deeply engrained negative self-schemas in OCD, often leading to difficulty in engaging in self-reinforcing social rituals (e.g., birthdays, graduations, and weddings). Recent clinical trials show psychoplastogenic drugs like psilocybin can rapidly reduce OCD symptoms, potentially by “resetting” these maladaptive self-models through heightened neuroplasticity (49).

Conclusion

A model of OCD as dysfunctional high-level priors and hyperactive inference driven by a negative, uncertain self-model provides insight into the disorder. It leads to the prediction that compulsive rituals should continue as long as self-uncertainty and flawed negative self-priors remain unadressed. We suggested the term hyperactive inference to explain compulsions as excessive Bayesian updating driven by inaccurate priors and a futile attempt to alleviate uncertainty about the self. The temporary relief of compulsive rituals ultimately reinforces the negative schemas generating pathological doubt and anxiety. Effective treatment should target core cognitive representations of the self rather than just surface symptoms. While the obsessional thoughts arise internally, the outer environment is more or less conducive to carrying out the compulsive rituals, with certain settings and situations providing more opportunity to engage in behaviors like checking, washing, counting, or arranging. Further research should explore neural implementations of this framework and implications for therapeutic approaches focused on the roots of uncertainty underlying OCD. By better understanding the wellspring of pathological inference in OCD, more targeted and effective interventions can be developed, modulating the self-confidence and deeply engrained assumptions at the origins of perfectionism and self-monitoring.

Author contributions

FS: Writing—original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. FS research at IACS was funded by Tiny Blue Dot Foundation and Joy Ventures.

Conflict of interest

FS is the co-founder of BeSound SAS and Nested Minds Ltd, holds ownership shares and has received compensation from both companies. In the past years, his work has been funded by the European Commission, Joy Ventures, Tiny Blue Dot Foundation, and the French Ministry of Armed Forces (AID).

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: APA (2013). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

2. Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Kessler RC. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. (2010) 15:53–63. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.94

3. Abramowitz JS, McKay D, Taylor S. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet. (2005) 366:1645–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60240-3

4. O'Connor KP, Aardema F, Pélissier MC. Beyond Reasonable Doubt: Reasoning Processes in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons (2005). doi: 10.1002/0470030275

5. Aardema F, Wong SF, Audet JS, Melli G, Baraby LP. Reduced fear-of-self is associated with improvement in concerns related to repugnant obsessions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Clin Psychol. (2019) 58:327–41. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12214

6. Aardema F, Moulding R, Melli G, Radomsky AS, Doron G, Audet JS, et al. The role of feared possible selves in obsessive-compulsive and related disorders: a comparative analysis of a core cognitive self-construct in clinical samples. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2018) 25:e19–29. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2121

7. Husain N, Chaudhry I, Raza-ur-Rehman, Ahmed GR. Self-esteem and obsessive compulsive disorder. J Pak Med Assoc. (2014) 64:64–8.

8. Ehntholt KA, Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA. Obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders, and self-esteem: an exploratory study. Behav Res Ther. (1999) 37:771–81. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00177-6

9. Aardema F, O'Connor K. The menace within: obsessions and the self. J Cogn Psychother. (2007) 21:182–97. doi: 10.1891/088983907781494573

10. Doron G, Kyrios M. Obsessive compulsive disorder: a review of possible specific internal representations within a broader cognitive theory. Clin Psychol Rev. (2005) 25:415–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.02.002

11. Doron G, Kyrios M, Moulding R. Sensitive domains of self-concept in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): further evidence for a multidimensional model of OCD. J Anxiety Disord. (2007) 21:433–44. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.05.008

12. Doron G, Moulding R, Kyrios M, Nedeljkovic M. Sensitivity of self-beliefs in obsessive compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety. (2008) 25:874–84. doi: 10.1002/da.20369

13. Bhar SS, Kyrios M. An investigation of self-ambivalence in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Therapy. (2007) 45:1845–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.02.005

14. Yang YH, Moulding R, Wynton SKA, Jaeger T, Anglim J. The role of feared self and inferential confusion in obsessive compulsive symptoms. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. (2021) 28:100607. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2020.100607

15. Godwin TL, Godwin HJ, Simonds LM. What is the relationship between fear of self, self-ambivalence, and obsessive–compulsive symptomatology? A systematic literature review. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2020) 27:887–901. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2476

16. Rozin P, Royzman EB. Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. (2001) 5:296–320. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0504_2

17. Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Rev Gen Psychol. (2001) 5:323–70. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

18. Kiverstein J, Rietveld E, Slagter HA, Denys D. Obsessive compulsive disorder: a pathology of self-confidence? Trends Cogn Sci. (2019) 23:369–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2019.02.005

19. Petrocchi N, Cosentino T, Pellegrini V, Femia G, D'Innocenzo A, Mancini F. Compassion-focused group therapy for treatment-resistant OCD: initial evaluation using a multiple baseline design. Front Psychol. (2021) 11:594277. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.594277

20. Jaeger T, Moulding R, Anglim J, Aardema F, Nedeljkovic M. The role of fear of self and responsibility in obsessional doubt processes: a Bayesian hierarchical model. J Soc Clin Psychol. (2015) 34:839–58. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2015.34.10.839

21. Friston KJ, Redish AD, Gordon JA. Computational nosology and precision psychiatry. Comput Psychiatry. (2017) 1:2. doi: 10.1162/cpsy_a_00001

22. Carhart-Harris RL, Chandaria S, Erritzoe DE, Gazzaley A, Girn M, Kettner H, et al. Canalization and plasticity in psychopathology. Neuropharmacology. (2023) 226:109398. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2022.109398

23. Einstein DA, Menzies RG. The presence of magical thinking in obsessive compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. (2004) 42:539–49. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00160-8

24. Friston K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nat Rev Neurosci. (2010) 11:127–38. doi: 10.1038/nrn2787

25. Rao RP, Ballard DH. Predictive coding in the visual cortex: a functional interpretation of some extra-classical receptive-field effects. Nat Neurosci. (1999) 2:79–87. doi: 10.1038/4580

26. Bastos AM, Usrey WM, Adams RA, Mangun GR, Fries P, Friston KJ. Canonical microcircuits for predictive coding. Neuron. (2012) 76:695–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.038

27. Fernandez S, Sevil C, Moulding R. Feared self and dimensions of obsessive compulsive symptoms: sexual orientation-obsessions, relationship obsessions, and general OCD symptoms. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. (2021) 28:100608. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2020.100608

28. Melli G, Aardema F, Moulding R. Fear of self and unacceptable thoughts in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2016) 23:226–35. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1950

29. Fitzgerald KD, Welsh RC, Gehring WJ, Abelson JL, Himle JA, Liberzon I, et al. Error-related hyperactivity of the anterior cingulate cortex in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. (2005) 57:287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.038

30. Wilhelm S, Berman NC, Keshaviah A, Schwartz RA, Steketee G. Mechanisms of change in cognitive therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder: role of maladaptive beliefs and schemas. Behav Res Ther. (2015) 65:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.12.006

31. Henriksen IO, Ranøyen I, Indredavik MS, Stenseng F. The role of self-esteem in the development of psychiatric problems: a three-year prospective study in a clinical sample of adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2017) 11:68. doi: 10.1186/s13034-017-0207-y

32. Chase TE, Chasson GS, Hamilton CE, Wetterneck CT, Smith AH, Hart JM. The mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties in the relationship between self-compassion and OCD severity in a non-referred sample. J Cognit Psychother. (2019) 33:157–68. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.33.2.157

33. Eichholz A, Schwartz C, Meule A, Heese J, Neumüller J, Voderholzer U. Self-compassion and emotion regulation difficulties in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2020) 27:630–9. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2451

34. Fonagy P, Gergely G, Target M. The parent–infant dyad and the construction of the subjective self. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2007) 48:288–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01727.x

36. Young JE, Klosko J, Weishaar ME. Schema Therapy: A Practitioner's Guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press (2003).

37. Winston R, Chicot R. The importance of early bonding on the long-term mental health and resilience of children. London J Prim Care. (2016) 8:12–4. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2015.1133012

38. Ainsworth MDS. Infant–mother attachment. Am Psychol. (1979) 34:932. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.932

39. Doron G. Self-vulnerabilities, attachment and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms: examining the moderating role of attachment security on fear of self. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. (2020) 27:100575. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2020.100575

40. Padykula NL, Conklin P. The self regulation model of attachment trauma and addiction. Clin Soc Work J. (2010) 38:351–60. doi: 10.1007/s10615-009-0204-6

41. Schore AN. The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Ment Health J. (2001) 22:201–69. doi: 10.1002/1097-0355(200101/04)22:1<;201::AID-IMHJ8>;3.0.CO;2-9

42. Stern DN. The Interpersonal World of the Infant: A View from Psychoanalysis and Developmental Psychology. New York, NY: Basic books (1985).

43. Strom R, Greathouse B. Play and maternal self concept. Theory Pract. (1974) 13: 297–302. doi: 10.1080/00405847409542524

44. Cassidy J. Child-mother attachment and the self in six-year-olds. Child Dev. (1988) 59:121. doi: 10.2307/1130394

46. Gergely G, Watson JS. The social biofeedback model of parental affect-mirroring. Int J Psychoanal. (1996) 77:1181–212.

47. Camoirano A. Mentalizing Makes Parenting work: a review about parental reflective functioning and clinical interventions to improve it. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00014

48. Fonagy P, Gergely G, Jurist EL, Target M. Affect Regulation, Mentalization and the Development of the Self. London: Karnac Books (2004).

Keywords: obsessive-compulsive disorder, Bayesian inference, self-model, hyperactive inference, self-confidence, precision, shame, mirroring

Citation: Schoeller F (2023) Negative self-schemas drive pathological doubt in OCD. Front. Psychiatry 14:1304061. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1304061

Received: 28 September 2023; Accepted: 27 November 2023;

Published: 22 December 2023.

Edited by:

Marco Grados, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesReviewed by:

Julian Kiverstein, Academic Medical Center, NetherlandsCopyright © 2023 Schoeller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Felix Schoeller, ZmVsaXhAYWR2YW5jZWRjb25zY2lvdXNuZXNzLm9yZw==

Felix Schoeller

Felix Schoeller