95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry , 05 February 2024

Sec. Digital Mental Health

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1265087

Kimberly S. Elliott1*

Kimberly S. Elliott1* Eman H. Nabulsi2

Eman H. Nabulsi2 Nicholas Sims-Rhodes2

Nicholas Sims-Rhodes2 Vandy Dubre3

Vandy Dubre3 Emily Barena4

Emily Barena4 Nelly Yuen4

Nelly Yuen4 Michael Morris1

Michael Morris1 Sarah M. Sass4

Sarah M. Sass4 Bridget Kennedy4

Bridget Kennedy4 Karan P. Singh2

Karan P. Singh2Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic prompted healthcare professionals to implement service delivery adaptations to remain in compliance with safety regulations. Though many adaptations in service delivery were reported throughout the literature, a wide variety of terminology and definitions were used.

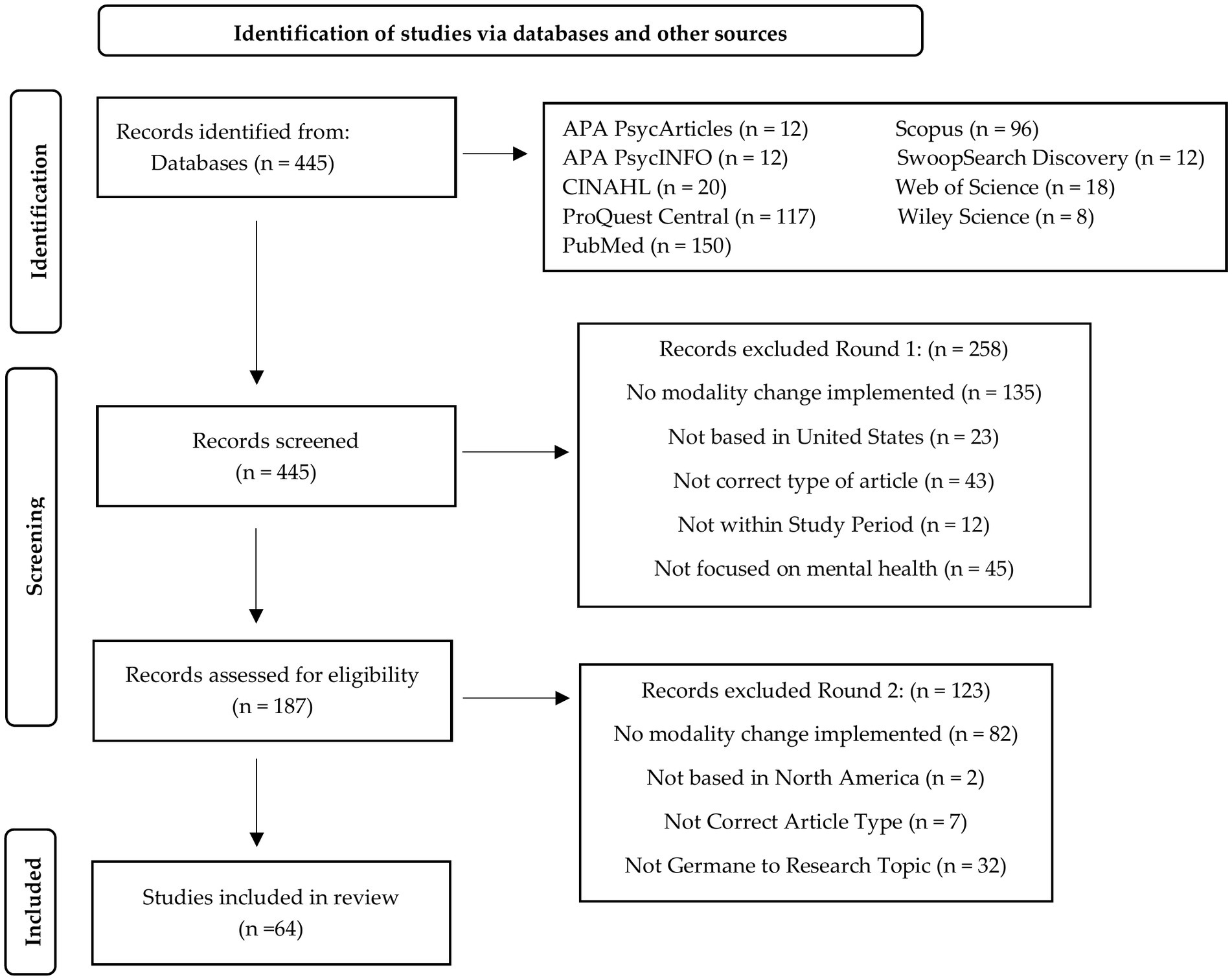

Methods: To address this, we conducted a PRISMA review to identify service delivery adaptations across behavioral healthcare services in the United States from March 2020 to May 2022 and to identify variations in terminology used to describe these adaptations. We identified 445 initial articles for our review across eight databases using predetermined keywords. Using a two-round screening process, authors used a team approach to identify the most appropriate articles for this review.

Results: Our results suggested that a total of 14 different terms were used to describe service modality changes, with the most frequent term being telehealth (63%). Each term found in our review and the frequency of use across identified articles is described in detail.

Discussion: Implications of this review such as understanding modality changes during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond are discussed. Our findings illustrate the importance of standardizing terminology to enhance communication and understanding among professionals.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a unique challenge to healthcare delivery in the U.S. In an effort to provide continued care to patients while reducing the risk of virus transmission, healthcare institutions adapted their modes of service delivery in accordance with the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) safety regulations and social distancing guidelines (1). During this time, there was a significant increase in the integration of technology-based health services and telecommunications. Although not a new process for many healthcare providers and institutions, the rapid shift necessitated a change in institutional and state level policies and procedures to help streamline the transition to a virtual care delivery model. Some of the immediate changes included the relaxing of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to allow for the use of various virtual conferencing platforms, as well as modifications in telehealth services covered by Medicaid/Medicare (2, 3). In addition, institutions expanded their IT infrastructure to create a pathway for online only operations and acquired additional technological equipment to utilize telehealth services (4).

Particularly for mental health services, the shift to remote/virtual service delivery was important for meeting the increased need for mental health services during the pandemic (5). Mental health providers reported an increased use of technology-based health services, with approximately 86% of the work of psychologists moved to virtual platforms and around 67% of psychologists conducting their clinical work via telepsychology (3). Virtual adaptations were made for various patient populations and varying degrees of complex clinical conditions, including trauma-focused care, treatment for individuals with intellectual disabilities, and individuals with serious mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia). Overall, these implementation changes ranged across provider and service type, as well as institutional setting. Understanding these adaptations is crucial for future preparedness and healthcare planning as it provides insights into effective strategies used which can inform healthcare systems for future crises.

Although institutions provided remote/virtual services through similar methods and platforms, they varied on which terms they used to describe their services and how they defined those terms. For example, “telehealth” and “telemedicine” were commonly used to discuss services offered via a virtual delivery model. However, how those terms were defined, and the types of practices encompassed within each term differed across settings (6). Moreover, multiple terms were used to describe the same practices and services, resulting in greater lexicon diversity.

The purpose of this PRISMA review was twofold: (1) to identify variations in the terminology and definitions used to describe such changes across healthcare settings and institutions and (2) to identify care modality changes implemented across healthcare systems and institutions in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020–May 2022). The expanded adoption of telehealth use provides an important opportunity for researchers and clinicians to further investigate the implementation and use of technology-based health services for patients. In addition, gaining a better understanding of terms and definitions for technology-based health services can help provide greater clarity around practices and services delivered, create more uniformity in language, and potentially impact the application of such services across healthcare systems.

Studies were included in this review if they were written in English, studies focused in the United States on mental health modality changes due to Covid response, published after March 11, 2020. Search criteria included Covid OR pandemic AND Telehealth OR “behavioral health” OR psychotherapy OR counseling OR psychiatry OR “mental health care” OR “health care delivery” both in the abstract with limiters of scholarly Peer Reviewed Journals. The full text only searching criteria option was not used as it allowed for discovery of the best articles for the study. Full text articles not recovered were interlibrary loaned from other universities.

To meet the research needs of this study, eight databases were individually searched to identify the articles for review: APA PsycArticles, APA PsycINFO, Ebscohost Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection, PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, Proquest Central, and Web of Science. These databases were selected as the key databases for psychological research available to the searcher as well as presenting a wide range of journals. Potential search limitations include dates of searching and the limitation of location. Multinational studies that included the United States were excluded.

The review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 methodology and matrix. The initial database search was conducted by a university research librarian. Titles, article metadata including keywords, abstracts, and geographical location of the study were scanned to identify appropriate articles. The initial search resulted in 445 articles. Utilizing the Sciwheel reference management system, the university accessible databases, and interlibrary loan, the full text of all identified articles was accessed using a collective process.

Through the Microsoft Teams platform, virtual meetings were held, and data and files were collected and organized. Excel was used for data collection and to categorize and rate each article regarding inclusion criterion. A two-round screening process was used for exclusion screening to identify the most appropriate articles for this review, to eliminate bias, and eliminate reader fatigue. An affinity matrix was used by all researchers to identify and codify themes within each article. Figure 1 provides the schematic flow of the sample identification and selection process.

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for rapid reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) figure that demonstrates the study selection process.

A total of 14 terms were used to describe how behavioral health care was delivered as a result of the pandemic. Table 1 shows the frequency of behavioral health modalities used as a result of the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Delivery modalities can be categorized as either audio-only or audio-visual. The modes of delivery were synchronous, asynchronous, or hybrid combinations. There were only two instances where the modalities described were delivered online without audio or audiovisual platforms. These two exceptions involved the use of online web or app-based programs. Table 2 shows the total sample selected and gives an overview of the sample data.

The majority of articles in this review (63%) used the term telehealth to discuss care modality changes implemented during the pandemic. There were slight variations in how authors defined telehealth, with some providing no explicit definition for the term while others provided detailed definitions. For the articles which did not provide a definition of telehealth, they instead offered examples of how telehealth was operationalized in their study (e.g., “telephone, video, email”). Alternatively, some articles broadly defined telehealth to include a range of communication platforms utilizing telephone or videoconferencing (17, 68). Other studies defined telehealth as “remote, real-time (i.e., synchronous) delivery of videoconferencing” or “psychotherapy provided via telephone or videoconferencing platforms,” respectively (34, 54). Some articles were more specific in their definitions, which reflected how they operationalized the term in relation to the change in modality being discussed. For example, one article defined telehealth as “providing clinician-led Family-Based Therapy to patients at a remote distance with the use of a videoconferencing platform” (39). Telehealth encompassed both psychiatry and psychology practice changes.

Across the articles included in this review, approximately 23% referred to technology-based modality changes such as telemedicine. Telemedicine was identified as a subset of telehealth and defined as the use of telephone or video-enabled technologies to deliver healthcare services when distance is a barrier (16). Telemedicine can be conducted synchronously (e.g., live, real-time audio or audiovisual meetings) and asynchronously (e.g., electronic messaging, patient monitoring), and it can include hybrid formats, such as in-person virtual rounding in an academic hospital setting (17). Telemedicine was not exclusive to a particular provider or service type and was utilized across various settings and populations such as primary care, pediatrics, psychiatry, psychology, neuropsychology, and social work. It was interchangeably used with broader terms such as telehealth.

Approximately 17% of articles in this review used the term telemental health to describe care modality changes implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. The definition for telemental health broadly included the use of smartphone and/or videoconferencing technologies to deliver mental health services. Some definitions specified whether services were delivered synchronously and/or asynchronously and explicitly defined how services were delivered remotely (e.g., on-site vs. off-site). Telemental health was interchangeably used with telebehavioral health, telepsychiatry, telepsychology, and teletherapy (18). Unlike broader terms such as telehealth and telemedicine, telemental health specifically referred to the delivery of mental health services via technology-based modalities.

Approximately 11% of the articles utilized the term telepsychiatry to primarily describe psychiatry consultation-liaison services conducted virtually either by telephone or video in a hospital setting. The modality of telepsychiatry was utilized to provide services to various departments of the hospital, including intensive care units, specialty outpatient clinics, and emergency departments. Care was delivered in hybrid formats, with some services delivered in-person through virtual means (19). Telepsychiatry was interchangeably used with telehealth, telemental health, telemedicine, and teleconsultation ((17, 20, 21)).

About 9% of the articles in this review utilized the term teletherapy to exclusively describe psychotherapy mental health services provided via virtual methods and platforms, either by telephone or video. Teletherapy was not used in conjunction with other terms. Teletherapy involved the delivery of services across various patient populations, service types (e.g., individual or group therapy), and treatment modalities (e.g., Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD) through virtual platforms. Services included synchronous and asynchronous formats.

Telebehavioral health was used in approximately 6% of articles in this review. Similar to telemental health, telebehavioral health was used specifically to describe mental health service delivery via virtual/remote platforms. Authors varied in how they defined telebehavioral health. Some articles discussed the format type (hybrid – virtual and in-person care vs. virtual only) in their definition. Most articles defined telebehavioral health to include the use of mobile technology, video conferencing, and audio-only services. Notably, the term telebehavioral health was used in conjunction with other terms in half of the instances, particularly telehealth.

The remaining modality terms were used only once (Telepsychology, Virtual Delivery, Videoconferencing Psychotherapy, Telephone-based Psychotherapy, Teleconsultation, Video Telehealth, Digital Health, Unguided Mental Health Program). These modality terms were generally used in conjunction with other more widely used terms to describe the mode of delivery of behavioral health services during the pandemic.

In terms of specific delivery formats, care was delivered either synchronously (in real time) or asynchronously. Among the synchronous modalities, patients were engaging in real time with licensed professionals using either audio-only devices (Teleconsultation and Telephone-based psychotherapy) or some form of audio-video conferencing software where they could be seen and heard (telepsychology, virtual delivery, videoconferencing and video telehealth).

The asynchronous deliveries involved the use of self-paced, web-based programs that could be accessed via online applications. The Unguided Mental Health program involved a strictly online or web-based program that could be completed anonymously. This modality was completely self-paced and asynchronous with no guidance from a licensed behavioral health professional (22). Digital Health involved the use of smartphone “app-based support” which followed in-person therapy. The online delivery involved a peer-support model and there were educational components to the app as well (23).

Overall, the common factors seen across terms and definitions included mode of delivery (e.g., telephone and/or videoconferencing technologies) and format type of that service delivery (synchronous vs. asynchronous). Some terms were used as umbrella terms to encompass a wide range of services (e.g., telehealth and telemedicine), while others were specific to a service type (e.g., teletherapy, telepsychology). Variations in definitions were seen in how each term was operationalized. For example, Beran and Sowa (9) defined telepsychiatry to include a “telepresenter” who is responsible for delivering a tablet to the patient to conduct their virtual visit with the doctor. Other definitions of telepsychiatry only specified whether services were offered in-real time or through asynchronous formats (e.g., patient portal videos). Altogether, the results indicate relative agreement between terms and definitions, with slight differences in the application of technology-based services.

The present review identified behavioral healthcare modality changes implemented in the U.S. during March 2020–May 2022 of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic created an opportunity to deliver mental health services virtually on a broader scale than was available pre-pandemic, and the utilization rate of these services has remained higher than pre-pandemic levels (71).

As can be seen in the present review, behavioral or mental health modality changes have been referred to by 14 terms in the literature during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our results show that the most common terms used were telehealth and telemedicine. Given that telehealth and telemedicine are both general terms that refer to different forms of service delivery beyond behavioral and mental health services, moving forward, practitioners and researchers working in the behavioral and mental health care space may wish to retain broad language (e.g., telehealth) while connecting it to more specific language that includes mental or behavioral health (e.g., telemental health). The addition of more specific language can allow practitioners, researchers, and mental health care consumers to identify appropriate literature more readily in evaluating whether a particular form of virtual mental health care is appropriate or effective for a given issue or problem.

On a related point, given the explosion of virtual behavioral and mental health care modalities during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, practitioners and researchers would benefit from standardizing behavioral and mental health care language rather than using a diversity of terminology to refer to the same services. For example, we found that terms such as telemental health, telepsychiatry, and telepsychology were used interchangeably in the literature. This raises the question of why they are all in use. One potential reason for variability in terminology includes the variety of fields involved in mental health care (e.g., counseling, psychology, psychiatry, social work) and the lack of connection between the literatures in these fields. Another potential reason for variability in terminology may be the fact that these services proliferated during COVID-19 among practitioners and in settings that did not commonly use these services. A lack of researcher and practitioner familiarity with the literature and relevant terminology may have resulted in a wide variety and lack of specificity in the terminology being used. Being clearer and more precise in the similarities and differences in terminology could focus the literature regarding these services. A more focused literature can advance efficacy and effectiveness research, practitioner and client access to the literature, and policy advocacy for the services that work.

Our review includes a broad range of organizations and settings that adopted telehealth modality changes during COVID, including state and regional hospitals, pediatric clinics, fetal and neonatal care settings, criminal justice settings, university training clinics, and the Veteran’s Health Administration. Populations served include all ages from young children to older adults, individual, group, family, and couple modalities, and a full range of psychological issues and diagnoses.

The increased use of telehealth during COVID-19 for mental and behavioral healthcare issues has shown that telehealth is feasible and can reduce barriers to care. Telehealth can increase accessibility to mental health services moving beyond the pandemic, which will require ongoing training and development of clear guidelines (72). The appropriate use of telehealth requires specific knowledge related to issues such as privacy protection. For example, awareness of requirements that virtual platforms must have to ensure that protected health information is secure is critical to the sustainability of telehealth (69).

Barriers to using telehealth for behavioral and mental health have included issues around insurance reimbursement policies (73), privacy concerns associated with virtual delivery (e.g., a secure platform), virtual platform accessibility, particularly in rural areas with less internet access (74), concerns about the efficacy of telehealth services (3) or a provider preference for face-to-face services (75) despite evidence indicating that some clients prefer virtual delivery and that behavioral and mental health services provided virtually are generally effective [(e.g., 76)].

To address the opportunities and barriers to telehealth for behavioral and mental health care, sustainable virtual mental healthcare options will require policy changes and support. For example, the previous and present U.S. administrations have supported access to virtual mental health services during COVID. The current White House advocates for continued insurance coverage for telemental health and to support delivery across state lines. In addition, recent legislation has extended Medicare telehealth coverage until December 31, 2024, underscoring the importance of these services.

Evidence to date suggests that virtual mental healthcare options are effective and reduce barriers to care, making sustainability of this modality of treatment a high priority (77). The present review provides evidence of how a wide variety of people with a wide range of issues have been supported by virtual mental healthcare options during the COVID-19 pandemic. We urge researchers and practitioners to continue to use, investigate, refine, and promote forms of telehealth treatment that work in ensuring accessibility of mental health care options for all.

KE: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EN: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NS-R: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VD: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation, review & editing. EB: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, review & editing. NY: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. MM: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. SS: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. BK: Writing – review & editing. KS: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Payments were made through grant funding ($900,000.00) from the Health Care Service Corporation (HCSC)- this is an unrestricted research grant awarded. The funder had no input or influence on the development of or conduct of the research presented in this manuscript. The project was partially funded through HCSC/BCBSTX, Affordable Cures Grant #1122327.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Blandford, A, Wesson, J, Amalberti, R, AlHazme, R, and Allwihan, R. Opportunities and challenges for telehealth within, and beyond, a pandemic. Lancet Glob Health. (2020) 8:e1364–5. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30362-4

2. Nielsen, M, and Levkovich, N. COVID-19 and mental health in America: crisis and opportunity? Fam Syst Health. (2020) 38:482–5. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000577

3. Pierce, BS, Perrin, PB, Tyler, CM, McKee, GB, and Watson, JD. The COVID-19 telepsychology revolution: a national study of pandemic-based changes in U.S. mental health care delivery. Am Psychol. (2021) 76:14–25. doi: 10.1037/amp0000722

4. Hsiao, V, Chandereng, T, Lankton, RL, Huebner, JA, Baltus, JJ, Flood, GE, et al. Disparities in telemedicine access: a cross-sectional study of a newly established infrastructure during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl Clin Inform. (2021) 12:445–58. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1730026

5. Bornheimer, LA, Li Verdugo, J, Holzworth, J, Smith, FN, and Himle, JA. Mental health provider perspectives of the COVID-19 pandemic impact on service delivery: a focus on challenges in remote engagement, suicide risk assessment, and treatment of psychosis. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22:718. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08106-y

6. Roy, J, Levy, D, and Senathirajah, Y. Defining telehealth for research, implementation, and equity. J Med Internet Res. (2022) 24:E35037. doi: 10.2196/35037

7. Ahlquist, LR, and Yarns, BC. Eliciting emotional expressions in psychodynamic psychotherapies using telehealth: a clinical review and single case study using emotional awareness and expression therapy. Psychoanal Psychother. (2022) 36:124–40. doi: 10.1080/02668734.2022.2037691

8. Alavi, Z, Haque, R, Felzer-Kim, IT, Lewicki, T, and Mormann, M. Implementing COVID-19 mitigation in the community mental health setting: march 2020 and lessons learned. Community Mental Health J. (2021) 57:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00677-6

9. Beran, C, and Sowa, NA. Adaptation of an academic inpatient consultation-liaison psychiatry service during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: effects on clinical practice and trainee supervision. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. (2021) 62:186–92. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.11.002

10. Brahmbhatt, K, Mournet, AM, Malas, N, DeSouza, C, Greenblatt, J, Afzal, KI, et al. Adaptations made to pediatric consultation-liaison psychiatry service delivery during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: a north American multisite survey. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. (2021) 62:511–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaclp.2021.05.003

11. Busch, AB, Huskamp, HA, Raja, P, Rose, S, and Mehrotra, A. Disruptions in care for medicare beneficiaries with severe mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e2145677. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.45677

12. Cantor, JH, McBain, RK, Kofner, A, Stein, BD, and Yu, H. Availability of outpatient telemental health services in the United States at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Care. (2021) 59:319–23. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001512

13. Caravella, RA, Deutch, AB, Noulas, P, Ying, P, Liaw, KR-L, Greenblatt, J, et al. Development of a virtual consultation-liaison psychiatry service: a multifaceted transformation. Psychiatr Ann. (2020) 50:279–87. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20200610-02

14. Chakawa, A, Belzer, LT, Perez-Crawford, T, and Yeh, HW. COVID-19, telehealth, and pediatric integrated primary care: disparities in service use. J Pediatr Psychol. (2021) 46:1063–75. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab077

15. Chang, JE, Lindenfeld, Z, Albert, SL, Massar, R, Shelley, D, Kwok, L, et al. Telephone vs. video visits during COVID-19: safety-net provider perspectives. J Am Board Family Med. (2021) 34:1103–14. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.06.210186

16. Cunningham, NR, Ely, SL, Barber Garcia, BN, and Bowden, J. Addressing pediatric mental health using telehealth during coronavirus disease-2019 and beyond: a narrative review. Acad Pediatr. (2021) 21:1108–17. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.06.002

17. Knott, D, and Block, S. Virtual music therapy: developing new approaches to service delivery. Music Ther Perspect. (2020) 38:151–6. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miaa017

18. Ehmer, AC, Scott, SM, Smith, H, and Ashby, BD. Connecting during COVID: the application of teleservices in two integrated perinatal settings. Infant Ment Health J. (2022) 43:127–39. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21958

19. Eyllon, M, Barnes, JB, Daukas, K, Fair, M, and Nordberg, SS. The impact of the covid-19-related transition to telehealth on visit adherence in mental health care: an interrupted time series study. Admin Pol Ment Health. (2022) 49:453–62. doi: 10.1007/s10488-021-01175-x

20. Ferguson, JM, Jacobs, J, Yefimova, M, Greene, L, Heyworth, L, and Zulman, DM. Virtual care expansion in the veterans health administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2020) 28:453–62. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa284

21. Frye, WS, Gardner, L, Campbell, JM, and Katzenstein, JM. Implementation of telehealth during COVID-19: implications for providing behavioral health services to pediatric patients. J Child Health Care. (2022) 26:172–84. doi: 10.1177/13674935211007329

22. Geller, PA, Spiecker, N, Cole, JCM, Zajac, L, and Patterson, CA. The rise of tele-mental health in perinatal settings. Semin Perinatol. (2021) 45:151431. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151431

23. Gentry, MT, Puspitasari, AJ, McKean, AJ, Williams, MD, Breitinger, S, Geske, JR, et al. Clinician satisfaction with rapid adoption and implementation of telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J E-health. (2021) 27:1385–92. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0575

24. Goldsamt, LA, Rosenblum, A, Appel, P, Paris, P, and Nazia, N. The impact of COVID-19 on opioid treatment programs in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2021) 228:109049. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109049

25. Grasso, C, Campbell, J, Yunkun, E, Todisco, D, Thompson, J, Gonzalez, A, et al. Gender-affirming care without walls: utilization of telehealth services by transgender and gender diverse people at a federally qualified health center. Transgender Health. (2022) 7:135–43. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0155

26. Hames, JL, Bell, DJ, Perez-Lima, LM, Holm-Denoma, JM, Rooney, T, Charles, NE, et al. Navigating uncharted waters: considerations for training clinics in the rapid transition to telepsychology and telesupervision during COVID-19. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 30:348–65. doi: 10.1037/int0000224

27. Held, P, Klassen, BJ, Coleman, JA, Thompson, K, Rydberg, TS, and Van Horn, R. Delivering intensive PTSD treatment virtually: the development of a 2-week intensive cognitive processing therapy-based program in response to COVID-19. Cogn Behav Pract. (2021) 28:543–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.09.002

28. Heyen, JM, Weigl, N, Müller, M, Müller, S, Eberle, U, Manoliu, A, et al. Multimodule web-based COVID-19 anxiety and stress resilience training (COAST): single-cohort feasibility study with first responders. JMIR Format Res. (2021) 5:e28055. doi: 10.2196/28055

29. Hinds, MT, Covell, NH, and Wray-Scriven, D. Covid-19 impact on learning among New York state providers and learners. Psychiatr Serv. (2020) 71:1324–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000605

30. Hughto, JMW, Peterson, L, Perry, NS, Donoyan, A, Mimiaga, MJ, Nelson, KM, et al. The provision of counseling to patients receiving medications for opioid use disorder: telehealth innovations and challenges in the age of COVID-19. J Subst Abus Treat. (2021) 120:108163. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108163

31. Hunsinger, N, Hammarlund, R, and Crapanzano, K. Mental health appointments in the era of covid-19: experiences of patients and providers. Ochsner J. (2021) 21:335–40. doi: 10.31486/toj.21.0039

33. Jeste, S, Hyde, C, Distefano, C, Halladay, A, Ray, S, Porath, M, et al. Changes in access to educational and healthcare services for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities during COVID-19 restrictions. J Intellect Disabil Res. (2020) 64:825–33. doi: 10.1111/jir.12776

34. Kalvin, CB, Jordan, RP, Rowley, SN, Weis, A, Wood, KS, Wood, JJ, et al. Conducting CBT for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder during COVID-19 pandemic. J Autism Dev Disord. (2021) 51:4239–47. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04845-1

35. Krider, AE, and Parker, TW. COVID-19 tele-mental health: innovative use in rural behavioral health and criminal justice settings. J Rural Ment Health. (2021) 45:86–94. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000153

36. Lau, J, Knudsen, J, Jackson, H, Wallach, AB, Bouton, M, Natsui, S, et al. Staying connected in the COVID-19 pandemic: telehealth at the largest safety-net system in the United States. Health Aff. (2020) 39:1437–42. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00903

37. Little, J., Schmeltz, A., Cooper, M., Waldrop, T., Yarvis, J. S., and Pruitt, L., & Dondanville, K. (2021). Preserving continuity of behavioral health clinical care to patients using mobile devices. Mil Med, 186, 137–141. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usaa281

38. Maier, CA, Riger, D, and Morgan-Sowada, H. “It’s splendid once you grow into it:” client experiences of relational teletherapy in the era of COVID-19. J Marital Fam Ther. (2021) 47:304–19. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12508

39. Matheson, BE, Bohon, C, and Lock, J. Family-based treatment via videoconference: clinical recommendations for treatment providers during COVID-19 and beyond. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:1142–54. doi: 10.1002/eat.23326

40. McIntyre, LL, Neece, CL, Sanner, CM, Rodriguez, G, and Safer-Lichtenstein, J. Telehealth delivery of a behavioral parent training program to Spanish-speaking Latinx parents of young children with developmental delay: applying an implementation framework approach. Sch Psychol Rev. (2021) 51:206–20. doi: 10.1080/2372966x.2021.1902749

41. Molfenter, T, Roget, N, Chaple, M, Behlman, S, Cody, O, Hartzler, B, et al. Use of telehealth in substance use disorder services during and after COVID-19: online survey study. JMIR Mental Health. (2021) 8:e25835. doi: 10.2196/25835

42. Moreland, A, Guille, C, and McCauley, JL. Increased availability of telehealth mental health and substance abuse treatment for peripartum and postpartum women: a unique opportunity to increase telehealth treatment. J Subst Abus Treat. (2021) 123:108268. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108268

43. Muppavarapu, K, Saeed, SA, Jones, K, Hurd, O, and Haley, V. Study of impact of telehealth use on clinic “no show” rates at an academic practice. Psychiatry Q. (2022) 93:689–99. doi: 10.1007/s11126-022-09983-6

44. Norman, S, Atabaki, S, Atmore, K, Biddle, C, DiFazio, M, Felten, D, et al. Home direct-to-consumer telehealth solutions for children with mental health disorders and the impact of COVID-19. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2022) 27:244–58. doi: 10.1177/13591045211064134

45. O'Dell, SM, Hosterman, SJ, Parikh, MR, Winnick, JB, and Meadows, TJ. Chasing the curve: program description of the Geisinger primary care behavioral health virtual first response to COVID-19. J Rural Ment Health. (2021) 45:95–106. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000180

46. Palinkas, LA, De Leon, J, Salinas, E, Chu, S, Hunter, K, Marshall, TM, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health policy and practice implementation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9622. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189622

47. Pinciotti, CM, Bulkes, NZ, Horvath, G, and Riemann, BC. Efficacy of intensive CBT telehealth for obsessive-compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Obsessive Compulsive Related Disord. (2022) 32:100705. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2021.100705

48. Puspitasari, A, Heredia, D, Coombes, B, Geske, J, Gentry, M, Moore, W, et al. Feasibility and initial outcomes of a group-based teletherapy psychiatric day program for adults with serious mental illness: open, nonrandomized trial in the context of COVID-19. JMIR Mental Health. (2021) 8:e25542. doi: 10.2196/25542

49. Puspitasari, AJ, Heredia, D, Gentry, M, Sawchuk, C, Theobald, B, Moore, W, et al. Rapid adoption and implementation of telehealth group psychotherapy during COVID 19: practical strategies and recommendations. Cogn Behav Pract. (2021) 28:492–506. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.05.002

50. Rauseo-Ricupero, N, Henson, P, Agate-Mays, M, and Torous, J. Case studies from the digital clinic: integrating digital phenotyping and clinical practice into today's world. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2021) 33:394–403. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1859465

51. Rosen, CS, Morland, LA, Glassman, LH, Marx, BP, Weaver, K, Smith, CA, et al. Virtual mental health care in the veterans health Administration's immediate response to coronavirus disease-19. Am Psychol. (2021) 76:26–38. doi: 10.1037/amp0000751

52. Rosenthal, SR, Sonido, PL, Tobin, AP, Sammartino, CJ, and Noel, JK. Breaking down barriers: young adult interest and use of telehealth for behavioral health services. Rhode Island Med J. (2022) 105:26–31.

53. Rowen, J, Giedgowd, G, and Baran, D. Effective and accessible telephone-based psychotherapy and supervision. J Psychother Integr. (2022) 32:3–18. doi: 10.1037/int0000257

54. Gaddy, S, Gallardo, R, McCluskey, S, Moore, L, Peuser, A, Rotert, R, et al. COVID-19 and music therapists’ employment, service delivery, perceived stress, and hope: a descriptive study. Music Ther Perspect. (2020) 38:157–66. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miaa018

55. Schoebel, V, Wayment, C, Gaiser, M, Page, C, Buche, J, and Beck, AJ. Telebehavioral health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative analysis of provider experiences and perspectives. Telemed J E-health. (2021) 27:947–54. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2021.0121

56. Sharma, A, Sasser, T, Schoenfelder Gonzalez, E, Vander Stoep, A, and Myers, K. Implementation of home-based telemental health in a large child psychiatry department during the COVID-19 crisis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. (2020) 30:404–13. doi: 10.1089/cap.2020.0062

57. Fisher, S, Guralnik, T, Fonagy, P, and Zilcha-Mano, S. Let’s face it: video conferencing psychotherapy requires the extensive use of ostensive cues. Couns Psychol Q. (2021) 34:508–24. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2020.1777535

58. Shklarski, L, Abrams, A, and Bakst, E. Navigating changes in the physical and psychological spaces of psychotherapists during COVID-19: when home becomes the office. Pract Innov. (2021) 6:55–66. doi: 10.1037/pri0000138

59. Slone, H, Gutierrez, A, Lutzky, C, Zhu, D, Hedriana, H, Barrera, JF, et al. Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on mental health providers in the southeastern United States. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 302:114055. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114055

60. Stancin, T. Reflections on changing times for pediatric integrated primary care during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Pract Pediatric Psychol. (2020) 8:217–9. doi: 10.1037/cpp0000370

61. Sugarman, DE, Busch, AB, McHugh, RK, Bogunovic, OJ, Trinh, CD, Weiss, RD, et al. Patients’ perceptions of telehealth services for outpatient treatment of substance use disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Addict. (2021) 30:445–52. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13207

62. Tolou-Shams, M, Folk, J, Stuart, B, Mangurian, C, and Fortuna, L. Rapid creation of child telemental health services during COVID-19 to promote continued care for underserved children and families. Psychol Serv Advance. (2021) 19:39–45. doi: 10.1037/ser0000550

63. Treitler, PC, Bowden, CF, Lloyd, J, Enich, M, Nyaku, AN, and Crystal, S. Perspectives of opioid use disorder treatment providers during COVID-19: adapting to flexibilities and sustaining reforms. J Subst Abus Treat. (2022) 132:108514. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108514

64. Uscher-Pines, L, Sousa, J, Jones, M, Whaley, C, Perrone, C, McCullough, C, et al. Telehealth use among safety-net organizations in California during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. (2021a) 325:1106–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0282

65. Uscher-Pines, L, Sousa, J, Raja, P, Mehrotra, A, Barnett, ML, and Huskamp, HA. Suddenly becoming a “virtual doctor”: experiences of psychiatrists transitioning to telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Serv. (2020) 71:1143–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000250

66. Waller, G, Pugh, M, Mulkens, S, Moore, E, Mountford, VA, Carter, J, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy in the time of coronavirus: clinician tips for working with eating disorders via telehealth when face-to-face meetings are not possible. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:1132–41. doi: 10.1002/eat.23289

67. Wood, HJ, Gannon, JM, Chengappa, KNR, and Sarpal, DK. Group teletherapy for first-episode psychosis: piloting its integration with coordinated specialty care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Psychother. (2021) 94:382–9. doi: 10.1111/papt.12310

68. Yeo, EJ, Kralles, H, Sternberg, D, McCullough, D, Nadanasabesan, R, Mayo, R, et al. Implementing a low-threshold audio-only telehealth model for medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder at a community-based non-profit organization in Washington, D.C. Harm Reduct J. (2021) 18:127. doi: 10.1186/s12954-021-00578-1

69. Yue, H, Mail, V, DiSalvo, M, Borba, C, Piechniczek-Buczek, J, and Yule, AM. Patient preferences for patient portal–based telepsychiatry in a safety net hospital setting during COVID-19: cross-sectional study. JMIR Format Res. (2022) 6:e33697. doi: 10.2196/33697

70. Zimmerman, M, Benjamin, I, Tirpak, JW, and D’Avanzato, C. Patient satisfaction with partial hospital telehealth treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: comparison to in-person treatment. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 301:113966. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113966

71. Lee, EC, Grigorescu, V, Enogieru, I, Smith, SR, Samson, LW, Conmy, A, et al. Updated national survey trends in telehealth utilization and modality: 2021- 2022 (issue brief no. HP-2023-09) In: Office of the Assistant Secretary for planning and evaluation, U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, vol. 2023 (2023).

72. Thomas, EE, Haydon, HM, Mehrotra, A, Snoswell, CL, Banbury, A, and Smith, AC. Building on the momentum: sustaining telehealth beyond COVID-19. J Telemed Telecare. (2022) 28:301–8. doi: 10.1177/1357633X20960638

73. Gajarawala, SN, and Pelkowski, JN. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J Nurse Pract. (2021) 17:218–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.09.013

74. Struminger, BB, and Arora, S. Leveraging telehealth to improve health care access in rural America: it takes more than bandwidth. Ann Intern Med. (2019) 171:376–7. doi: 10.7326/M19-1200

75. Saiyed, S, Nguyen, A, and Singh, R. Physician perspective and key satisfaction indicators with rapid telehealth adoption during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Telemed E-health. (2021) 27:1225–34. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0492

76. Backhaus, A, Agha, Z, Maglione, ML, Repp, A, Ross, B, Zuest, D, et al. Videoconferencing psychotherapy: a systematic review. Psychol Serv. (2012) 9:111–31. doi: 10.1037/a0027924

Keywords: behavioral health, behavioral health modality, COVID-19, pandemic, telehealth, telemedicine

Citation: Elliott KS, Nabulsi EH, Sims-Rhodes N, Dubre V, Barena E, Yuen N, Morris M, Sass SM, Kennedy B and Singh KP (2024) Modality and terminology changes for behavioral health service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1265087. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1265087

Received: 24 July 2023; Accepted: 27 November 2023;

Published: 05 February 2024.

Edited by:

Oswald David Kothgassner, Medical University of Vienna, AustriaReviewed by:

Sasidhar Gunturu, Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Elliott, Nabulsi, Sims-Rhodes, Dubre, Barena, Yuen, Morris, Sass, Kennedy and Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kimberly S. Elliott, S2ltYmVybHkuZWxsaW90dEB1dGhjdC5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.