- Department of Orthopedics, Jinjiang Municipal Hospital, Fujian, China

Objective: To investigate whether depression and exposure to anti-depressant medication are independent risk factors for incident knee surgery and opioid use in knee osteoarthritis (KOA) patients.

Methods: We identified all patients who visited our outpatient department and were clinically diagnosed with KOA between January 2010 and January 2018. We retrieved their demographic, clinical, and radiographic data from the database of our hospital. Next, we analyzed the effect of depression and anti-depressant medication on the incident knee surgery and opioid use in KOA patients.

Results: A total of 4,341 KOA patients were found eligible to form the study population. Incident knee surgery and opioid use for the purpose of treating osteoarthritis were observed in 242 and 568 patients, respectively. Incident knee surgery was significantly associated with age (OR [95%CI], 1.024 [1.009–1.039], P = 0.002), BMI (OR [95%CI], 1.090 [1.054–1.128], P < 0.001), baseline K-L grade 3 (OR [95%CI], 1.977 [1.343–2.909], P = 0.001), baseline K-L grade 4 (OR [95%CI], 1.979 [1.241–3.157], P = 0.004), depression (OR [95%CI], 1.670 [1.088–2.563], P = 0.019), and exposure to anti-depressant medication (OR [95%CI], 2.004 [1.140–3.521], P = 0.016). Incident opioid use was significantly associated with depression (OR [95%CI], 1.554 [1.089–2.215], P = 0.015) and exposure to anti-depressant medication (OR [95%CI], 1.813 [1.110–2.960], P = 0.017).

Conclusion: Depression and anti-depressant drug exposure were independently associated with incident knee surgery, highlighting the need for more attention on comorbid depression in KOA management.

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a prevalent and disabling disease characterized by the structural degradation of cartilage, persistent pain, joint stiffness, and functional limitations, affecting more than 10% of the overall population as estimated (1–3). According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (4), because of the increase in the aging population, the disease burden of KOA has been rapidly growing worldwide over the past decades (5).

Depression is also a major challenge for medical society with rapidly increasing disease burden in recent decades (6). Studies conducted in different countries consistently showed that depression is greatly more prevalent among patients with osteoarthritis (7–9). Thus, there is a huge population affected by depression and osteoarthritis simultaneously. A previous study showed that more than 20% of patients with osteoarthritis had depressive symptoms (10). Notably, a recent study revealed a huge care gap in this large population that only half of KOA patients with comorbid depression received mental health (11). Conversely, depression largely contributed to rapid progression (8, 12). Therefore, the interplay between KOA and depression and depression-related medications should be investigated with urgency (13).

Opioids are recommended by multiple guidelines for the management of KOA pain after failure of other pain-relieving medications (14, 15). However, the misuse and abuse of opioid medications is an emerging challenge over the past two decades (16). Many factors are associated with this issue, including aggressive pain control and inappropriate prescription (17). Both depression and osteoarthritis were deeply involved in this opioid abuse/misuse epidemic (18–20). Opioid exposure in KOA patients contributed to increased medical cost, impaired productivity, potential for abuse, and increased mortality (19, 21, 22). Therefore, reducing prolonged opioid use may lead to a meaningful reduction in social and economic costs for KOA patients (19). However, depressed patients are at substantial risk of prolonged opioid use (18, 23). In addition, the severity of depression is closely associated with opioid-related problems (24). Opioid use itself also contributed to new onset and progression of depression (25, 26).

The aims of this study were, therefore, to determine whether depression and exposure to anti-depressant medications were associated with the incidence of knee surgery and opioid use.

Patients and methods

Study population

We identified all patients who visited our outpatient department and were clinically diagnosed as KOA between January 2010 and January 2018 using the hospital information system (HIS). The clinical diagnosis of KOA was made by clinical specialists in orthopedic and/or sports medicine. It was generally determined based on patient history, physical examination, and laboratory and radiographic findings (27). Patients were excluded from this study if they had structural knee injuries (fractures, ligament ruptures, meniscal tears, and dislocations) (n = 345), any knee surgery histories (n = 125), missing values for baseline variables (n = 567), and declined to participate (n = 1,152). Our study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and all local laws and regulations, and we obtained ethics approval for collecting all related data.

Baseline patient data

To better assess the radiographic severity of KOA, we defined the baseline as the time of performing the first knee plain radiograph during the study period. All baseline demographic and clinical data were retrieved from HIS, and the information was further confirmed by contacting patients by all possible means. The baseline demographic data consisted of demographic information [age, sex, body mass index (BMI)] and education. The Kellgren–Lawrence (K-L) grades (28) were rated by a radiographic evaluation committee consisting of three radiologists specialized in musculoskeletal radiology. The rating process was conducted without grouping information. The consensus on grading was achieved by the majority. When the two knees had different K-L grades, the final K-L grade was recorded according to the more severe side. Generally, in our institution, we treated KOA patients initially with topical or oral NSAIDs. When the initial treatment fails, we would recommend intra-articular therapies and opioid medication based on the preferences of patients.

Depression and anti-depressant drugs

The diagnosis of depression and exposure to anti-depressant drugs, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic anti-depressants (TCAs), and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), were first reported by patients and further confirmed by reviewing their medical records.

Definition of incident knee surgery and opioid exposure

The incident knee surgery and types of surgery were reported by patients. The incident knee surgery was defined as any surgical procedure performed to treat KOA, no matter whether this type of surgical procedure was recommended or not. Incident knee surgery in the current study included knee arthroplasty, arthroscopic procedures, and high tibial osteotomy (HTO). The efficacy and safety of arthroplasty and HTO have been well-established and generally recommended for KOA management (29, 30). However, although many high-quality randomized trials have consistently demonstrated that arthroscopic procedures, including lavage, debridement, and arthroscopic partial meniscectomy, are ineffective and even harmful for KOA patients by accelerating joint destruction and increasing future arthroplasty risks, these high-quality evidence most published in leading medical journals have failed to prevent surgeons from performing arthroscopic procedures for managing KOA (31–34). We, therefore, also considered incident arthroscopic procedures as clinically important events of poor symptom control and disease progression. Incident opioid exposure was defined as the initiation of opioid use during the study period for opioid-naïve patients at baseline. The opioid exposure history was reported by patients and confirmed by reviewing their medical records by researchers.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (26.0, IBM, Chicago, USA). The statistical significance was set at a two-sided 0.05. We first tabulated descriptive statistics to summarize the characteristics of the subjects. Continuous and categorical variables were, respectively, presented as means ± standard deviations and counts (percentage), unless otherwise indicated. When the yielded P-value was less than 0.2 in univariable analysis, the variables along with demographic variables (age, sex, and BMI) were further included in logistic regression for multivariable analysis.

Results

The association between depression/anti-depressant medication and incident knee surgery

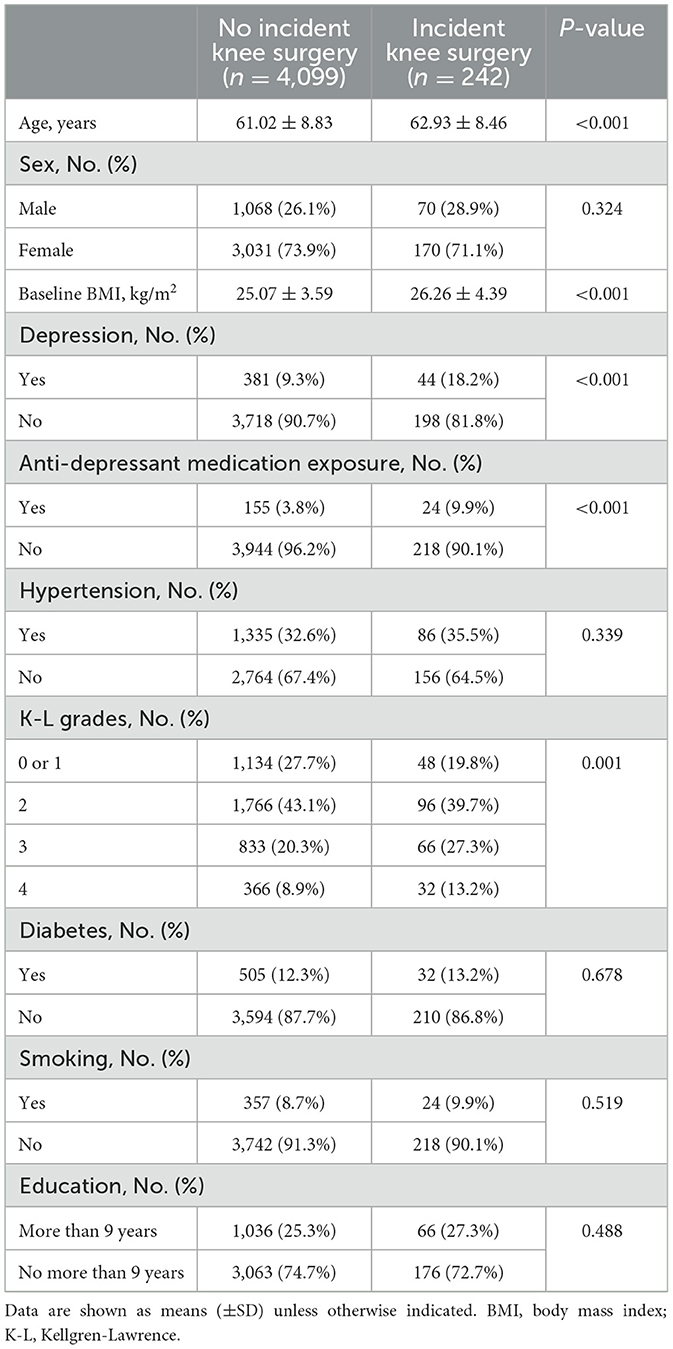

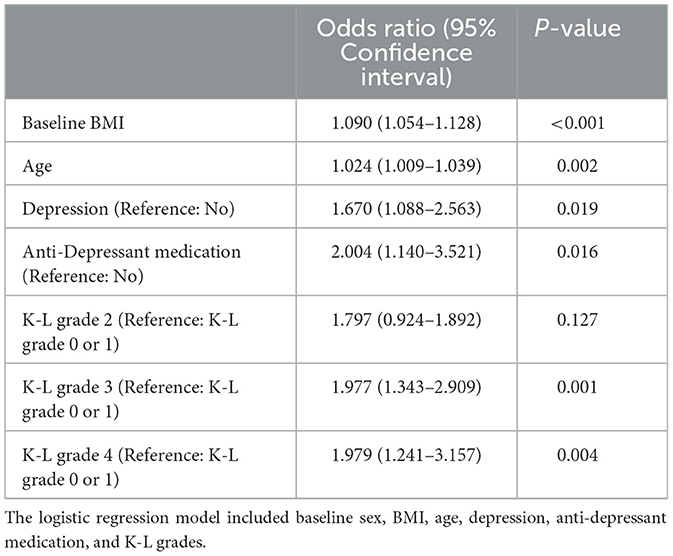

A total of 4,341 KOA patients were found eligible for the final analysis. Incident knee surgery to treat osteoarthritis was observed in 242 patients. Specifically, 70 patients had knee arthroplasty, 162 had arthroscopic procedure, and 10 had high tibial osteotomy. Of the 179 patients with exposure to anti-depressant medication, 146 patients used these drugs for their depressive disorders, 20 for Alzheimer's disease, 6 for obsessive-compulsive disorder, 4 for phobia, and 3 for other mental disorders. For univariable analyses, incident knee surgery was significantly associated with age, BMI, baseline K-L grades, depression, and exposure to anti-depressant medication (Table 1). For multivariable analysis, incident knee surgery was significantly associated with age (OR [95%CI], 1.024 [1.009–1.039], P = 0.002), BMI (OR [95%CI], 1.090 [1.054–1.128], P < 0.001), baseline K-L grade 3 (OR [95%CI], 1.977 [1.343–2.909], P = 0.001), baseline K-L grade 4 (OR [95%CI], 1.979 [1.241–3.157], P = 0.004), depression (OR [95%CI], 1.670 [1.088–2.563], P = 0.019), and exposure to anti-depressant medication (OR [95%CI], 2.004 [1.140–3.521], P = 0.016; Table 2).

The association between depression/anti-depressant medication and incident opioid use

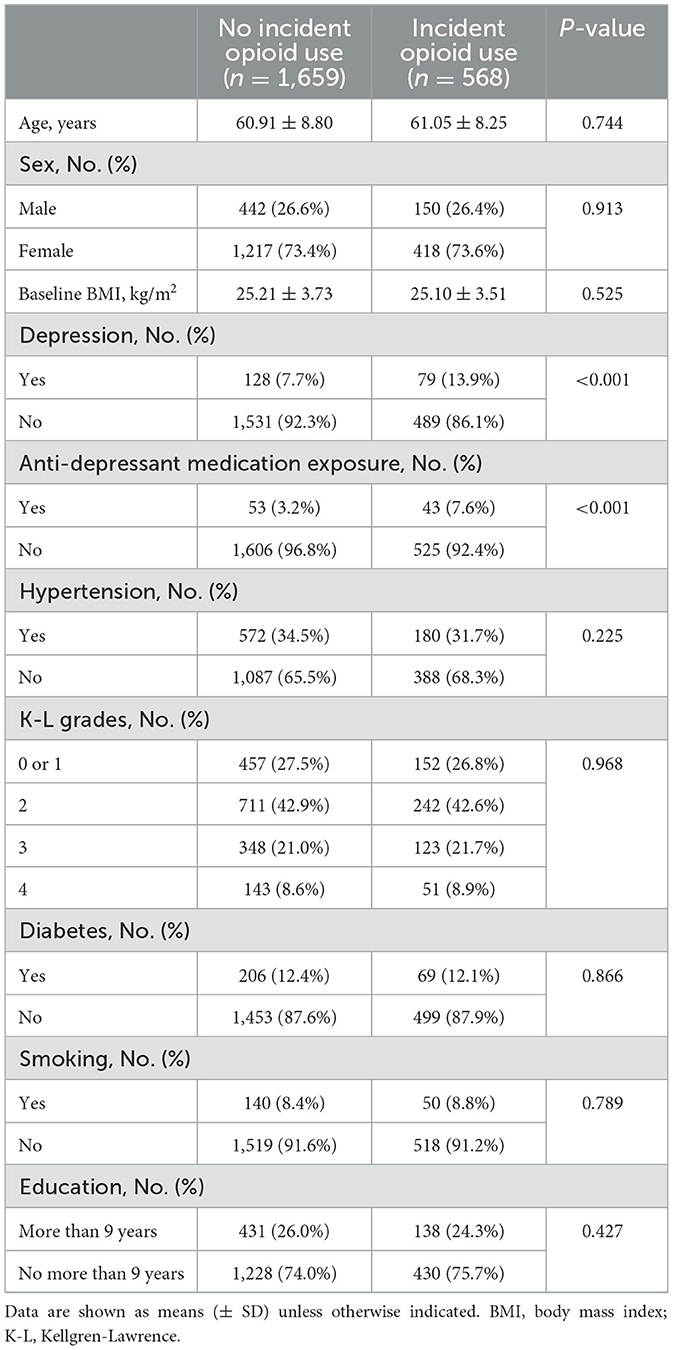

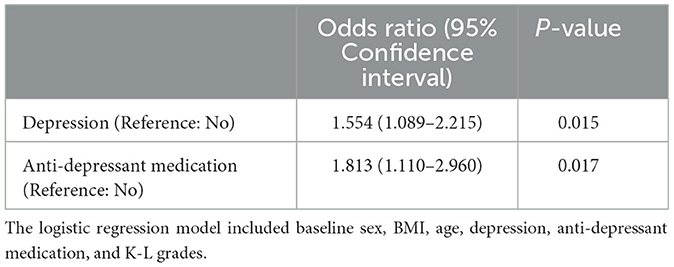

A total of 2,227 KOA patients were opioid-naïve and thus included in the subsequent analysis. During the study period, 568 patients initiated opioid therapies. For univariable analyses, incident opioid use was also significantly associated with depression and exposure to anti-depressant medication (Table 3). For multivariable analysis, incident opioid use was significantly associated with depression (OR [95%CI], 1.554 [1.089–2.215], P = 0.015) and exposure to anti-depressant medication (OR [95%CI], 1.813 [1.110–2.960], P = 0.017; Table 4).

Table 3. Univariable analysis on characteristics grouped by incident opioid use in opioid-naïve KOA patients.

Table 4. Multivariable analysis on characteristics grouped by incident opioid use in opioid-naïve KOA patients.

Discussion

Although more than 20% of patients with osteoarthritis had depressive symptoms (10), depression is frequently underdiagnosed and undertreated (35). Thus, in this study, the prevalence of clinically diagnosed depression in this study was lower than 10%. This fact also once again argued that comorbid depression in KOA patients needed more attention from physicians and patients. A previous study revealed that pain symptoms caused by KOA would largely contribute to the progression of depression (36). Conversely, patients with depressive disorder have substantial pain over-sensitization in the central nervous system, which leads to more severe symptoms in KOA patients (37). A pilot study using a combined approach to address both depression and KOA simultaneously yielded more benefits for improving depression, pain, and functional outcomes (13). In addition, we also demonstrated that depression increased the chance of opioid use in KOA patients. We all know inappropriate prescription of opioids played an important role in the opioid epidemic. The misuse rate of overprescribed opioids was strikingly high, highlighting the urgency of restraining opioid use in KOA patients. Careful management of depression could help to curb the opioid epidemic. Notably, depressed patients initiate opioid therapy slightly more often than non-depressed patients and are twice as likely to transition to long-term use (18). In studies that carefully control for confounding by indication, it has been shown that long-term opioid therapy increases the risk of incident, recurrent, and treatment-resistant depression (18). Thus, it is also important to understand the interplay between opioid use and depression in KOA patients.

Overweight/obesity is a well-established risk factor for both KOA and depression (36). For KOA management, weight management has previously been recommended as a core approach for achieving long-term benefits, especially for those with overweight/obesity (38–40). For depression, high BMI is a risk factor for the development, progression, and recurrence of depression (41, 42). Thus, weight loss might be beneficial for patients with both diseases. However, weight loss greater than 5% was considered clinically relevant, but this goal is generally difficult to reach even after exercise and dieting (43). Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), including semaglutide, liraglutide, and dulaglutide, are a newly emergent class of weight-reducing drugs (44). A multicenter prospective study revealed that GLP-1RAs acted as disease-modifying drugs for KOA patients mediated by weight loss (2). Future research may need to pay more attention to this class of game-changing drugs.

The current study had several limitations. First, future prospective studies are still needed to validate our findings. Notably, because of the retrospective nature, the patient-reported outcomes were unknown in this study. Second, because of the observational nature of this study, the decision process on surgical treatment and opioid use is a black box for us. Similarly, the current study could not evaluate the disease status of depression. Third, the arthroscopic procedures were ineffective and even harmful to KOA patients. The rationale behind this practice (performing arthroscopic procedures in KOA patients) remained unclear for the current study. We assumed that these receiving arthroscopic procedures reflect the poor control of symptoms caused by KOA. Finally, there is no consensus regarding the diagnosis of depression. We used clinically diagnosed depression, and extrapolation of our conclusion to a different setting should be cautious.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee at Jinjiang Municipal Hospital (jjsyyyxll-2012001). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

JZ developed the idea of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted the manuscript. YZ participated in the design of the study and revised the manuscript. YX and YF assessed the radiographs and collected the data. ZL, ZW, and YZ followed up the patients, collected the data, and analyzed the data. LL and XL contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Funding

The study was funded by the Shanghai Shen Kang Hospital Development Centre, the Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (Grant Number: SHDC2020CR6019), and the Science and Technology Project of Quanzhou City (2020N079s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the investigators and staff at participating centers.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. (2014) 73:1323–30. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763

2. Zhu H, Zhou L, Wang Q, Cai Q, Yang F, Jin H, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists as a disease-modifying therapy for knee osteoarthritis mediated by weight loss: findings from the Shanghai Osteoarthritis Cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. (2023) 82:1218–26. doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-223845

3. Hunter DJ, Schofield D, Callander E. The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2014) 10:437–41. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.44

4. GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. (2020) 396:1223–49. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30752-2

5. Long H, Liu Q, Yin H, Wang K, Diao N, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence trends of site-specific osteoarthritis from 1990 to 2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2022) 74:1172–83. doi: 10.1002/art.42089

7. Van Dyne A, Moy J, Wash K, Thompson L, Skow T, Roesch SC, et al. Health, psychological and demographic predictors of depression in people with fibromyalgia and osteoarthritis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:3413. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063413

8. Jacobs CA, Vranceanu AM, Thompson KL, Lattermann C. Rapid progression of knee pain and osteoarthritis biomarkers greatest for patients with combined obesity and depression: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Cartilage. (2020) 11:38–46. doi: 10.1177/1947603518777577

9. Marks R. Comorbid depression and anxiety impact hip osteoarthritis disability. Disabil Health J. (2009) 2:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2008.10.001

10. Stubbs B, Aluko Y, Myint PK, Smith TO. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. (2016) 45:228–35. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw001

11. Gleicher Y, Croxford R, Hochman J, Hawker G. A prospective study of mental health care for comorbid depressed mood in older adults with painful osteoarthritis. BMC Psychiatry. (2011) 11:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-11-147

12. Rathbun AM, Schuler MS, Stuart EA, Shardell MD, Yau MS, Gallo JJ, et al. Depression subtypes in individuals with or at risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. (2020) 72:669–78. doi: 10.1002/acr.23898

13. Lin EH. Depression and osteoarthritis. Am J Med. (2008) 121(11 Suppl 2):S16–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.009

14. Geenen R, Overman CL, Christensen R, Åsenlöf P, Capela S, Huisinga KL, et al. EULAR recommendations for the health professional's approach to pain management in inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. (2018) 77:797–807. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212662

15. Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 american college of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. (2020) 72:149–62. doi: 10.1002/acr.24131

16. Compton WM, Boyle M, Wargo E. Prescription opioid abuse: problems and responses. Prev Med. (2015) 80:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.04.003

17. Bates C, Laciak R, Southwick A, Bishoff J. Overprescription of postoperative narcotics: a look at postoperative pain medication delivery, consumption and disposal in urological practice. J Urol. (2011) 185:551–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.088

18. Sullivan MD. Depression effects on long-term prescription opioid use, abuse, and addiction. Clin J Pain. (2018) 34:878–84. doi: 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000603

19. Huizinga JL, Stanley EE, Sullivan JK, Song S, Hunter DJ, Paltiel AD, et al. Societal cost of opioid use in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis patients in the United States. Arthritis Care Res. (2022) 74:1349–58. doi: 10.1002/acr.24581

20. Trouvin AP, Berenbaum F, Perrot S. The opioid epidemic: helping rheumatologists prevent a crisis. RMD Open. (2019) 5:e001029. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001029

21. Felson D. Tramadol and mortality in patients with osteoarthritis. JAMA. (2019) 322:465–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.7216

22. DeMik DE, Bedard NA, Dowdle SB, Burnett RA, McHugh MA, Callaghan JJ. Are we still prescribing opioids for osteoarthritis? J Arthroplasty. (2017) 32:3578–82.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.07.030

23. Browne CA, Lucki I. Targeting opioid dysregulation in depression for the development of novel therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. (2019) 201:51–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.04.009

24. Rogers AH, Orr MF, Shepherd JM, Bakhshaie J, Ditre JW, Buckner JD, et al. Anxiety, depression, and opioid misuse among adults with chronic pain: the role of emotion dysregulation. J Behav Med. (2021) 44:66–73. doi: 10.1007/s10865-020-00169-8

25. Mayor S. Long term opioid analgesic use is linked to increased risk of depression, study shows. BMJ. (2016) 352:i134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i134

26. Thielke SM, Shortreed SM, Saunders K, Turner JA, LeResche L, Von Korff M. A prospective study of predictors of long-term opioid use among patients with chronic noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. (2017) 33:198–204. doi: 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000409

27. Skou ST, Koes BW, Grønne DT, Young J, Roos EM. Comparison of three sets of clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study of 13,459 patients treated in primary care. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2020) 28:167–72. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.09.003

28. Reijman M, Hazes JM, Koes BW, Verhagen AP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Validity, reliability, and applicability of seven definitions of hip osteoarthritis used in epidemiological studies: a systematic appraisal. Ann Rheum Dis. (2004) 63:226–32. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.010348

29. Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJ, Agricola R, Price AJ, Vincent TL, Weinans H, et al. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. (2015) 386:376–87. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60802-3

30. Martel-Pelletier J, Barr AJ, Cicuttini FM, Conaghan PG, Cooper C, Goldring MB, et al. Osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2016) 2:16072. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.72

31. Moseley JB, O'Malley K, Petersen NJ, Menke TJ, Brody BA, Kuykendall DH, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. (2002) 347:81–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013259

32. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Kalske J, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for a degenerative meniscus tear: a 5 year follow-up of the placebo-surgery controlled FIDELITY (Finnish Degenerative Meniscus Lesion Study) trial. Br J Sports Med. (2020) 54:1332–9. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102813

33. Stahel PF, Wang P, Hutfless S, McCarty E, Mehler PS, Osgood GM, et al. Surgeon practice patterns of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative disease in the United States: a measure of low-value care. JAMA Surg. (2018) 153:494–6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.6235

34. Rickert J. On patient safety: orthopaedic surgeons must stop performing arthroscopic partial meniscectomy on patients with arthritic knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2020) 478:28–30. doi: 10.1097/corr.0000000000001072

35. VanItallie TB. Subsyndromal depression in the elderly: underdiagnosed and undertreated. Metabolism. (2005) 54(5 Suppl 1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.01.012

36. Zheng S, Tu L, Cicuttini F, Zhu Z, Han W, Antony B, et al. Depression in patients with knee osteoarthritis: risk factors and associations with joint symptoms. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2021) 22:40. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03875-1

37. López-Ruiz M, Losilla JM, Monfort J, Portell M, Gutiérrez T, Poca V, et al. Central sensitization in knee osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia: beyond depression and anxiety. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0225836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225836

38. Arden NK, Perry TA, Bannuru RR, Bruyère O, Cooper C, Haugen IK, et al. Non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis: comparison of ESCEO and OARSI 2019 guidelines. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2021) 17:59–66. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00523-9

39. Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JW, Andreassen O, Christensen P, Conaghan PG, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. (2013) 72:1125–35. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202745

40. Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2020) 72:220–33. doi: 10.1002/art.41142

41. Silva DA, Coutinho E, Ferriani LO, Viana MC. Depression subtypes and obesity in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. (2020) 21:e12966. doi: 10.1111/obr.12966

42. Sahle BW, Breslin M, Sanderson K, Patton G, Dwyer T, Venn A, et al. Association between depression, anxiety and weight change in young adults. BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19:398. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2385-z

43. Wang Q, Runhaar J, Kloppenburg M, Boers M, Bijlsma JWJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Diagnosis of early stage knee osteoarthritis based on early clinical course: data from the CHECK cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. (2021) 23:217. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02598-5

44. Rubino DM, Greenway FL, Khalid U, O'Neil PM, Rosenstock J, Sørrig R, et al. Effect of weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs daily liraglutide on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity without diabetes: the STEP 8 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2022) 327:138–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.23619

Keywords: KOA, anti-depressant, risk factor, knee surgery, opioid, depression

Citation: Zheng Y, Zhang J, Wang Z, Liu X, Xu Y, Fang Y, Lin Z and Lin L (2023) Anti-depressant medication use is a risk factor for incident knee surgery and opioid use in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Front. Psychiatry 14:1243124. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1243124

Received: 21 June 2023; Accepted: 30 October 2023;

Published: 27 November 2023.

Edited by:

Roberto Ciccocioppo, University of Camerino, ItalyReviewed by:

Hongyi Zhu, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaChangqing Zhang, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China

Copyright © 2023 Zheng, Zhang, Wang, Liu, Xu, Fang, Lin and Lin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinshan Zhang, emhhbmdqaW5zaGFuMTkzQHNpbmEuY29t

†ORCID: Yongqiang Zheng orcid.org/0000-0002-9780-3808

Jinshan Zhang orcid.org/0009-0000-8412-2424

Zefeng Wang orcid.org/0009-0001-6433-9244

Liang Lin orcid.org/0009-0007-9195-6671

Yongqiang Zheng

Yongqiang Zheng Jinshan Zhang

Jinshan Zhang Zefeng Wang†

Zefeng Wang† Xiaofeng Liu

Xiaofeng Liu Yangzhen Fang

Yangzhen Fang