- 1Department of Psychiatry, The Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 2National Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders, The Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Jining Medical University, Jining, Shandong, China

- 4Department of Mental Health, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi, China

- 5Department of Social Psychiatry, The Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

- 6Department of Mental Health Institute of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, The Affiliated Mental Center of Inner Mongolia Medical University, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China

- 7Department of Psychiatry, Qiqihar Medical University, Qiqihar, Heilongjiang, China

- 8Xinjiang Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders, The Psychological Medicine Center, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China

- 9Department of Psychiatry, Gannan Medical University, Ganzhou, Jiangxi, China

- 10Department of Psychiatry, The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, China

- 11Department of Psychiatry, Jiangxi Provincial People’s Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Medical College, Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

Introduction: The childhood experiences of being overprotected and overcontrolled by family members have been suggested to be potentially traumatic. However, the possible associated factors of these experiences among young people are still not well studied. This study aimed to partly fill such gaps by a relatively large, nationwide survey of Chinese university students.

Methods: A total of 5,823 university students across nine different provinces in China were included by the convenience sampling method in the data analyses. All participants completed the overprotection/overcontrol (OP/OC) subscale in a recently developed 33-item childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ- 33). Data were also collected on all participants’ socio-demographic profiles and characterization of mental health. Binary logistic regression was conducted to investigate the associated socio-demographic and psychological factors of OP/ OC.

Results: The prevalence of childhood OP/OC was estimated as 15.63% (910/5,823) based on a cutoff OP/OC subscale score of ≥ 13. Binary logistic regression suggested that being male, being a single child, having depression, having psychotic-like experiences, lower family functioning, and lower psychological resilience were independently associated with childhood OP/OC experiences (all corrected-p < 0.05). The OP/OC was also positively associated with all the other trauma subtypes (abuses and neglects) in the CTQ-33, while there are both shared and unique associated factors between the OP/OC and other trauma subtypes. Post-hoc analyses suggested that OP/OC experiences were associated with depression in only females and associated with anxiety in only males.

Discussion: Our results may provide initial evidence that childhood OP/OC experiences would have negative effects on young people’s mental health which merits further investigations, especially in clinical populations.

1. Introduction

Overprotection/overcontrol (OP/OC) behaviors were defined as behaviors in which caregivers (including parents and other family members) are overly involved in children’s daily activities and experiences, often caused by excessive anxiety about the children’s safety (1, 2). As suggested by past studies, multiple possible reasons may lead to OP/OC behaviors. For example, some parents exhibited fear in fulfilling their parenting responsibilities, which may in turn lead to their OP/OC (3). Furthermore, a lack of care by one parent can also lead to OP/OC behaviors by the other one (4). A prior research study has shown that perceived OP/OC from family members might limit children’s development of a clear understanding of environmental dangers and might have negative effects on their mental health statuses (5, 6). For instance, perceived OP/OC experiences were suggested to be possibly associated with decreased self-efficacy and increased vulnerability to perceived threats (1), the development of childhood anxiety (3), as well as the onset of anorexia (7) in children and teenagers. In addition, OP/OC might be related to increased risks of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (8), and suicidal behaviors (9).

In addition to the short-term negative psychological effects of OP/OC in children/teenagers as mentioned above, recent studies have also suggested that OP/OC might be developmentally traumatizing, and childhood OP/OC experiences may have long-term effects on one’s mental health in early adulthood and even later life (5, 10, 11). For instance, individual recall of childhood OP/OC appears to be associated with a higher prevalence and incidence of adult psychological health problems in the general population (12–14). Some evidence suggests that childhood OP/OC experiences are related to sleep disturbance (15) and associated with difficult recovery in patients with schizophrenia (16) in adulthood. Another related study reported that overprotective support reduced stress in the short term but hindered individuals from coping with stress in the long run by weakening autonomy, especially when that support is terminated (17). For these reasons, perceived OP/OC during childhood has been regarded as a kind of traumatic experience besides the other well-known childhood trauma subtypes (e.g., abuses and neglects) and attracted attention in recent psychological studies (2, 18). Recognizing and identifying factors associated with childhood OP/OC experiences, therefore, may be valuable for improving our understanding of the developments of common mental problems and disorders, as well as finding potential targets for early interventions for mental disorders.

The current literature about possible associated factors of childhood OP/OC experiences in young people, however, is still limited in several ways. First, some previous results have reported inconsistent and even conflicting conclusions. For example, while many earlier studies as mentioned above suggested that childhood OP/OC is related to more mental problems including depressive and anxiety symptoms in later life, the opposite results were also reported, e.g., that paternal overcontrols predicted lower anxious-depressed symptoms (19). One of the potential reasons for these contradictory results may be the insufficient sample size in many of these studies; for instance, the samples in most of the previous studies range from only dozens to hundreds (20–23), which may lead to relatively low statistical power and unreliable results. Second most of the prior studies have focused on the associations between OP/OC and several common mental problems such as anxiety and depression; however, the knowledge is limited on the relationships between OP/OC and some other important socio-demographic profiles and mental health characteristics. These characteristics include, for example, psychological resilience which is defined as one’s ability to recover and maintain adaptive behaviors when facing constant stress (24). There has been evidence that other subtypes of childhood trauma (e.g., abuses and neglects) could lead to a lower psychological resilience, which mediates the relationships between childhood trauma and depression in college students (25). As a kind of traumatic experiences, OP/OC experiences may be also associated with a lower psychological resilience, which remains however poorly investigated to our knowledge. Third, while most of the prior studies on OP/OC experiences were conducted in Western countries, it is relatively little known about the prevalence and associated factors of OP/OC among youths under other cultural conditions, such as in China. One possible reason for such a limitation is the lack of an easy and feasible screening tool for OP/OC experiences in the Chinese language. Nevertheless, this gap has been addressed by a recently validated Chinese version of the 33-item expanded childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ-33) (18), and further studies on OP/OC among the young Chinese populations may be warranted.

In the current study, we aim to address the limitations raised above by performing a nationwide, large-sample survey among the young Chinese population. Specifically, a total of 5,823 Chinese university students across nine different provinces in China were included in the analyses. Data were collected on all participants’ childhood OP/OC experiences, socio-demographic profiles, and characterization of mental health (e.g., psychological resilience). Logistic regression models were conducted to investigate the possible associations between childhood OP/OC experiences and other socio-demographic/psychological factors. We hope that our results will shed light on the understanding of the possible role of OP/OC in psychological health among young people.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

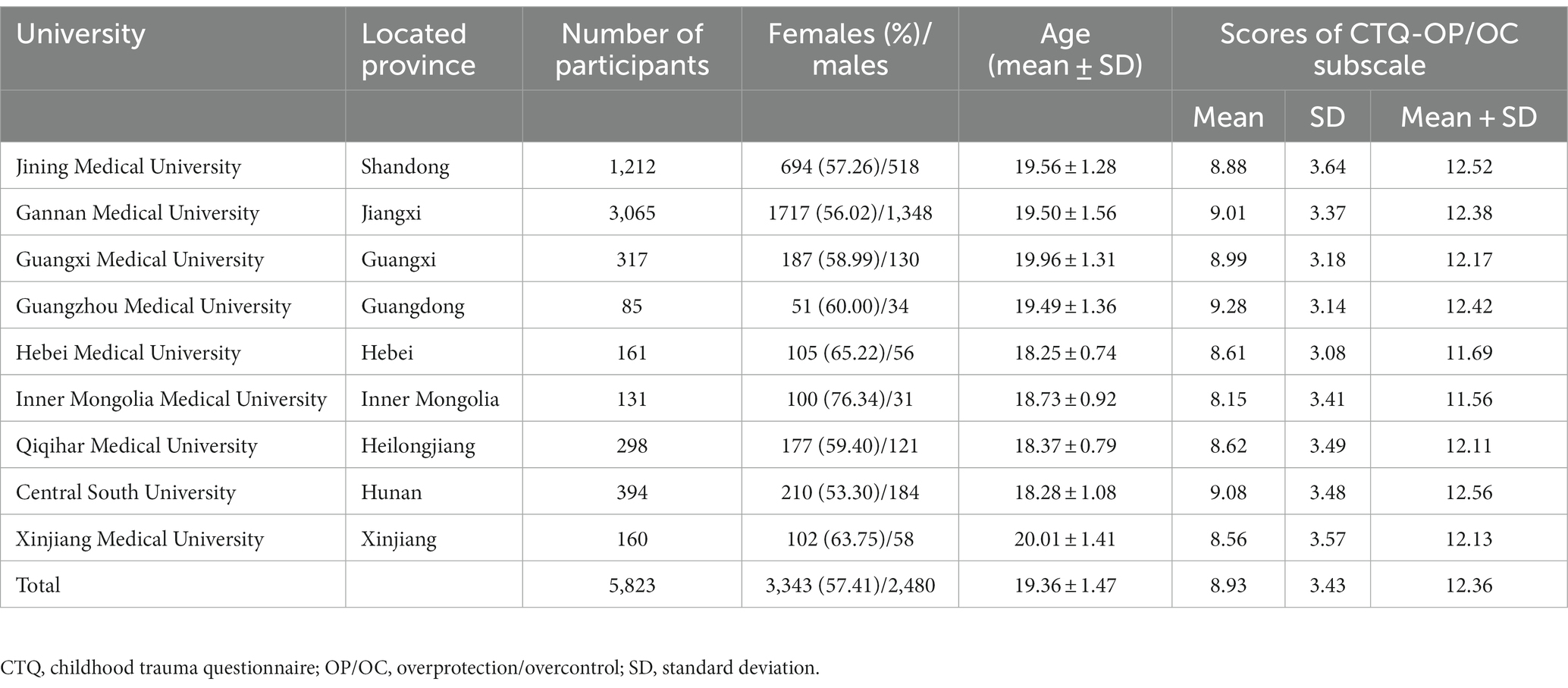

A total of 5,993 Chinese university students were initially recruited in this survey using the convenience sampling method from nine universities across nine different provinces (Shandong, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Guangdong, Hebei, Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang, Hunan, and Xinjiang) in China (see distributions in Table 1). The survey was conducted from September 2021 to October 2021, and all students completed the survey online through a famous platform in China, “Questionnaire Star”.1 To avoid the potential confounding impacts of other clinical conditions on the results, students with a previous diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder were excluded (n = 120). In addition, students with missing data (n = 47) or over the age of 25 years (n = 3) were excluded. Therefore, 5,823 participants were included in the final data analyses in the current study (see Table 1 for sample characteristics). All participants and/or their guardians gave informed consent to agree to participate in this study. The research proposal was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University.

2.2. Assessments

2.2.1. Socio-demographic factors

Information on the following socio-demographic factors was collected from all participants and taken into the analyses: age, sex, ethnicity (Han or minority), single-child household (yes or no), parental separation (yes or no), left-behind children experiences (“Are one or both parents have not been with the participants for at least 6 months before the age of 16 years?,” yes or no), as well as family histories of mental disorders. Note that all participants with a personal history of mental disorders have been excluded from the analyses.

2.2.2. Measure of OP/OC experiences

Childhood OP/OC experiences of all participants were measured by the OP/OC subscale of the CTQ-33 (2). The CTQ-33 was expanded from the original 28-item childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ-28) (26) with an additional OP/OC subscale and thus has six subscales measuring six different subtypes of childhood trauma experiences: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, and OP/OC (2). All items in the CTQ-33 are 5-point Likert-type questions, and higher scores indicate higher levels of childhood trauma experiences. The Chinese version of the original CTQ-28 has been shown to have good reliability and validity in Chinese populations (27). The additional OP/OC subscale in the CTQ-33 has also been translated into Chinese and proved to be valid (18). In the current study, the CTQ-33 displayed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.843).

Based on prior publications, participants with scores above the cutoff points for a particular subscale can be defined as having a particular subtype of childhood trauma experience as follows: physical abuse ≥10, emotional abuse ≥13, sexual abuse ≥8, physical neglect ≥10, and emotional neglect ≥15 (28, 29). In the present study, we intended to first classify all participants into those with and without childhood OP/OC experiences. However, to the best of our knowledge, an optimal cutoff point for the OP/OC subscale in the CTQ-33 has not been established to date. Therefore, referring to multiple published studies (30–32), we estimated the appropriate cutoff score for the OP/OC subscale based on one standard deviation (SD) above the mean score in the surveyed sample. The participants with an OP/OC subscale score higher than such a cutoff point were then defined as having childhood OP/OC experiences.

2.2.3. Self-reported depression

All participants completed the self-reported, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (33) to assess the severity of depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The Chinese version of PHQ-9 has been validated in a previous study (34). Each item of the PHQ-9 was rated on four values ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”). The total score of PHQ-9 can range from 0 to 27, and the participants were regarded to have depression when the total score ≥10 (35). In the present study, the PHQ-9 displayed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.903).

2.2.4. Self-reported anxiety

All participants completed the self-reported, 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) (36) to assess their anxiety levels during the last 2 weeks. The Chinese version of GAD-7 has shown good reliability and validity in the Chinese population (37, 38). Each item of the GAD-7 was rated from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”). The total score of GAD-7 can range from 0 to 21, and the participants were regarded to have anxiety when the total score ≥10 (37, 38). The GAD-7 displayed good internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.923).

2.2.5. Psychotic-like experiences

The 15-item version of the Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences (CAPE-15) (39–41) was used to evaluate the psychotic-like experiences of all participants. The Chinese version of the CAPE has been validated and is widely used to assess psychotic-like experiences in Chinese populations (42–45). The CAPE-15 includes 15 items that measured both frequency of and distress associated with a series of common psychotic-like experiences (e.g., subclinical delusions and hallucinations). Both the frequency and distress scores of each item are rated on a four-point Likert scale. Referring to prior studies (46), the participants were regarded to have meaningful psychotic-like experiences when both the mean frequency score and mean distress score were greater than 1.5. The frequency score of each subject showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.871).

2.2.6. Family functioning

The family functioning of each participant was measured by the Family APGAR scale (47, 48). The Chinese version of Family APGAR has been validated and widely used in previous studies (48–50). The Family APGAR scale consists of five items assessing family functioning from five dimensions: adaptation (“A”), partnership (“P”), growth (“G”), affection (“A”), and resolution (“R”). The score of each item ranges from 0 (“almost always”) to 2 (“hardly ever”). Total scores of the Family APGAR scale can thus range from 0 to 10, and a relatively low family functioning can be defined by a total score ≤3 (48–50). The Chinese version of the Family APGAR in our research has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.922).

2.2.7. Psychological resilience

Each participant’s psychological resilience was measured by the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) (51), a self-administered questionnaire extracted from the original 25-item version (52). The Chinese version of CD-RISC has been validated and widely used in previous studies (24, 53, 54). In the CD-RISC, the score of each item ranges from 0 to 4 (0 = “never” to 4 = “almost always”), and the total score ranges from 0 to 40. Referring to prior research (53), the cutoff of a CD-RISC a total score of ≤25 was used to define a relatively low psychological resilience. The Chinese version of the CD-RISC in this sample has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.966).

2.3. Statistical analyses

Socio-demographic and psychological characteristics were first compared between the participants with and without childhood OP/OC experiences using descriptive statistics. Independent t-tests and chi-square tests were used for continuous variables (e.g., age) and categorical variables (e.g., sex), respectively.

In line with some prior studies (55), binary logistic regression analysis was then performed to investigate the possible associations between all socio-demographic/psychological factors (age, sex, years of education, ethnicity, province, single child, parental separation, left-behind experiences, family history of mental disorders, depression, anxiety, psychotic-like experiences, family functioning, and psychological resilience) and childhood OP/OC experiences after adjusting for the confounding effects of other variables. It should be noted that we took all factors into account in regression models and when investigating the relationship between OP/OC and one factor, the possible confounding effects of all the other factors have been excluded. In addition, the province (coded as dummy variables) was controlled in the analyzing models as a variable of no interest. The p-values were corrected across the 14 factors using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) corrections, and a corrected p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Moreover, since previous studies have suggested that OP/OC is highly positively correlated with all the other trauma subtypes (abuses and neglects) in the CTQ-33 (2), we did not include other subscales of the CTQ-33 in the regression model to avoid possible multicollinearity problems. Instead, we explored their relationships with OP/OC using separate models in the following supplementary analyses (see later in Section 2.4).

2.4. Supplementary analyses

Several supplementary analyses were performed in addition to the main analyses. First, we tested the relationships between OP/OC and other trauma subtypes (abuses and neglects) in the CTQ-33 using Spearman correlations. We also tested whether OP/OC and other trauma subtypes would have similar associated socio-demographic/psychological factors: here, all participants were classified into those with and without a particular subtype of childhood trauma (e.g., psychical abuse, based on the cutoffs mentioned in Section 2.2.2), and separate binary regression models were used to investigate the associated factors of such trauma subtype. Similar to the analyses on OP/OC, the statistical significance was set at an FDR-corrected p-value of < 0.05.

Second, considering that sex differences in mental health have been widely reported (56–58), we further explored the possible sex differences in relationships between OP/OC and other factors. Here, similar to analyses in the entire sample, the associated factors of childhood OP/OC experiences were assessed by binary logistic regression models in the male (N = 2,480) and female (N = 3,343) participants separately, and the statistical significance was still set at an FDR-corrected p-value of < 0.05.

2.5. Validation analysis

In the current study, we estimated an appropriate cutoff point for the OP/OC subscale at ≥13. To confirm whether the identified associated factors of OP/OC would change when using different cutoff scores, we repeated the regression analyses using two other different cutoff points ≥12 and ≥14, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics and estimated cutoff points

Sample characteristics of the analyzed participants are shown in Table 1. The proportion of female participants was 57.41% (3,343/5,823), and the average age was 19.36 years (SD = 1.47) for the entire sample.

Before the analyses, we first compared the OP/OC scores between different provinces to see whether they can be treated as a homogeneous sample. In the entire sample, the (mean + 1SD) value of the OP/OC subscale score was 12.36. Meanwhile, the (mean + 1SD) values of the OP/OC subscale scores were found to be very close across the subsamples from different provinces. Specifically, in most (7/9) of the subsamples, such values were in the range of 12.11–12.56 except in Hebei (11.69) and Inner Mongolia (11.56; Table 1). Nevertheless, these two provinces had relatively small sample size (N = 161/131 for Hebei and Inner Mongolia, respectively) which may bias the results. Therefore, we propose that the distributions of OP/OC scores in different provinces were very close, suggesting they can be treated as a homogeneous sample. According to these results, we also propose that an OP/OC subscale score of ≥13 may be an appropriate cutoff to classify those having and not having clinically meaningful OP/OC experiences. Such a cutoff point was also applied in the following analyses.

3.2. Group comparisons on socio-demographic and psychological characteristics

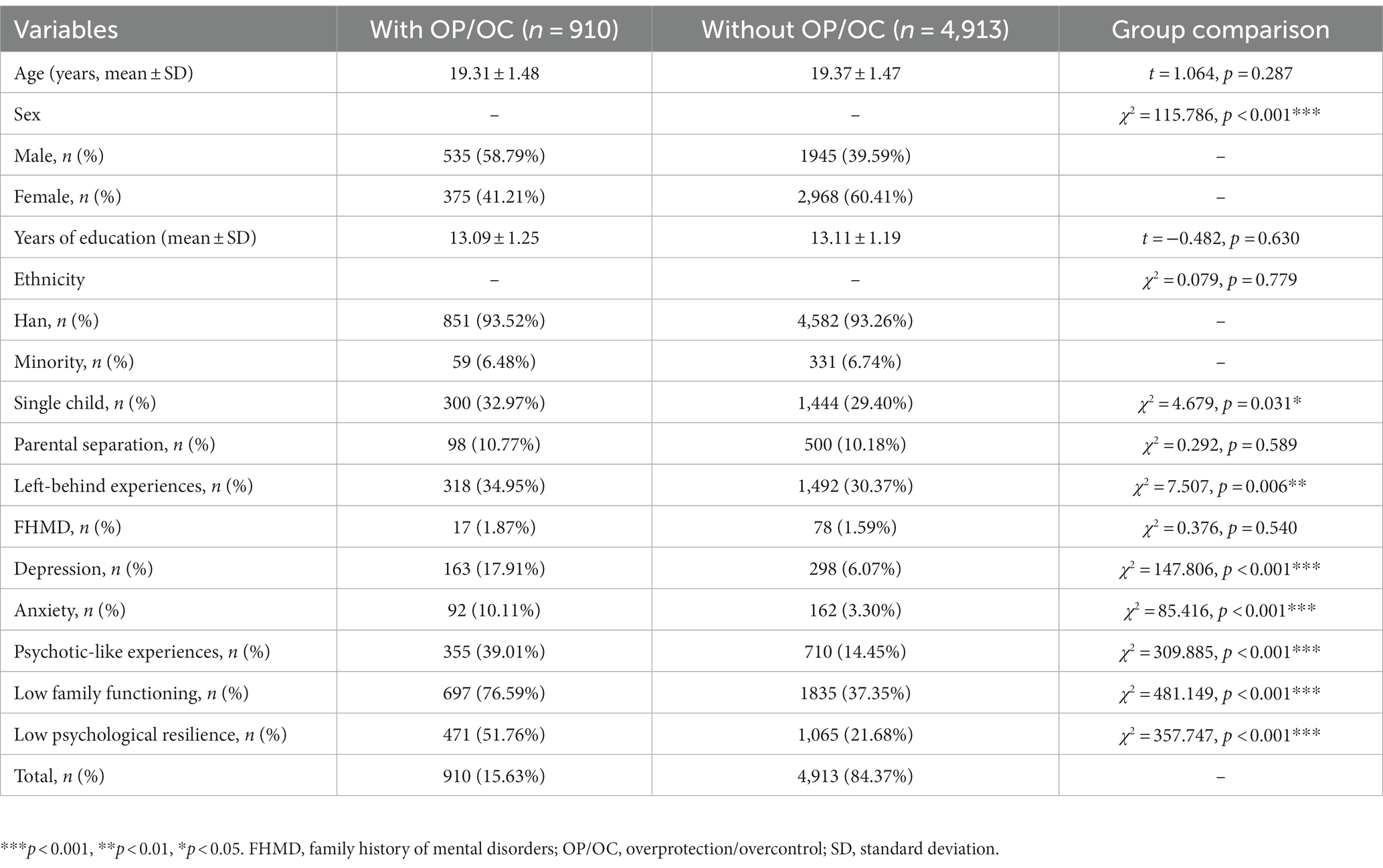

Based on the above cutoff point (OP/OC subscale score ≥ 13), the prevalence of OP/OC experiences was estimated as 15.63% (910/5,823) in the current sample. Results of the direct comparisons on all characteristics between the participants with and without OP/OC experiences were shown in Table 2. Compared with those without OP/OC, the participants with OP/OC experiences had a higher proportion of males (p < 0.001), a higher proportion of single child (p = 0.031), and a higher proportion of “left-behind” children (p = 0.006). Compared with those without OP/OC, the participants with OP/OC experiences are more likely to have depression, anxiety, psychotic-like experiences, low family functioning, and low psychological resilience (all p < 0.001).

Table 2. Comparisons on socio-demographic and psychological characteristics between the participants with and without childhood OP/OC experiences.

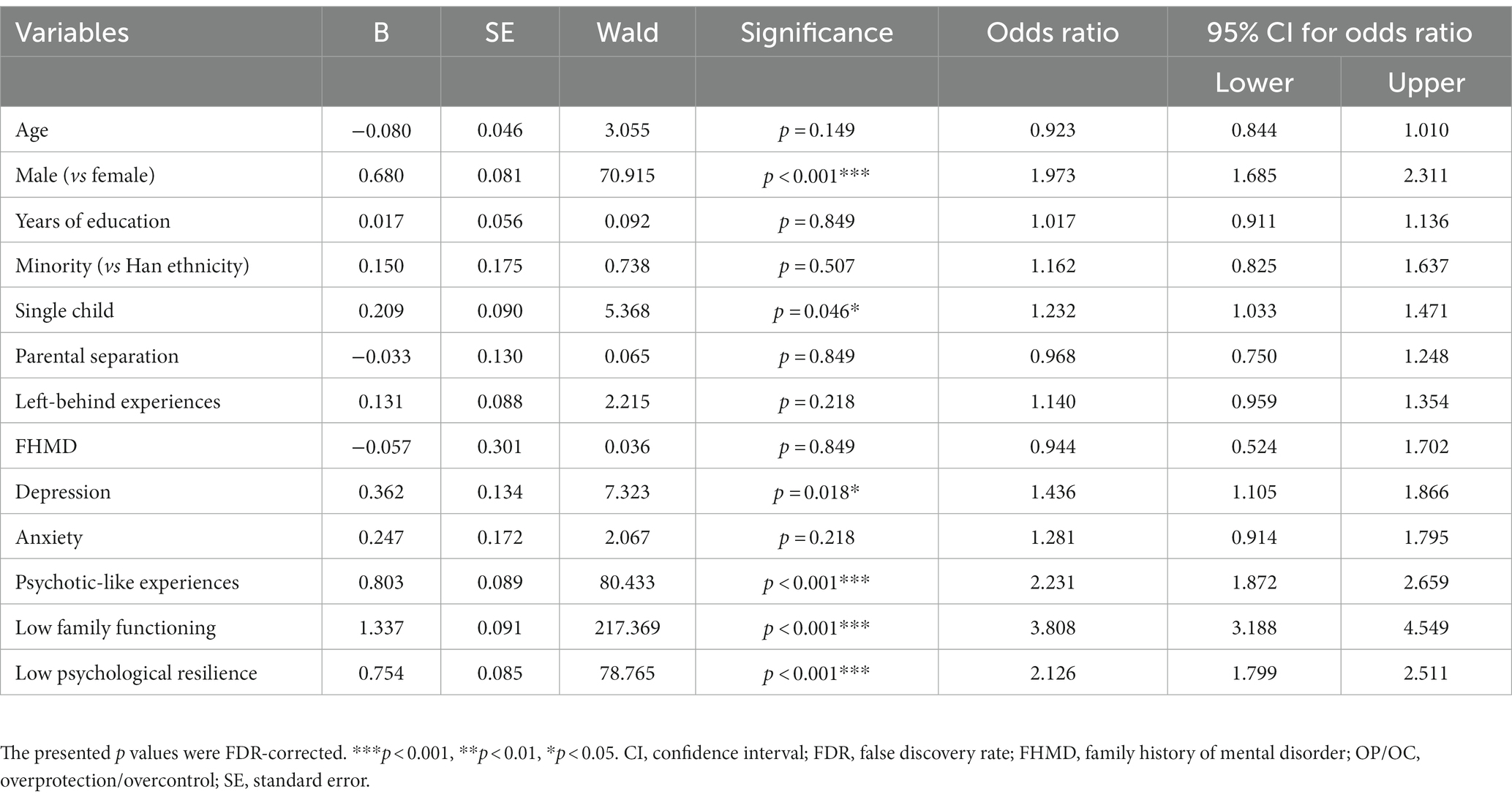

3.3. Results of binary logistic regression analysis

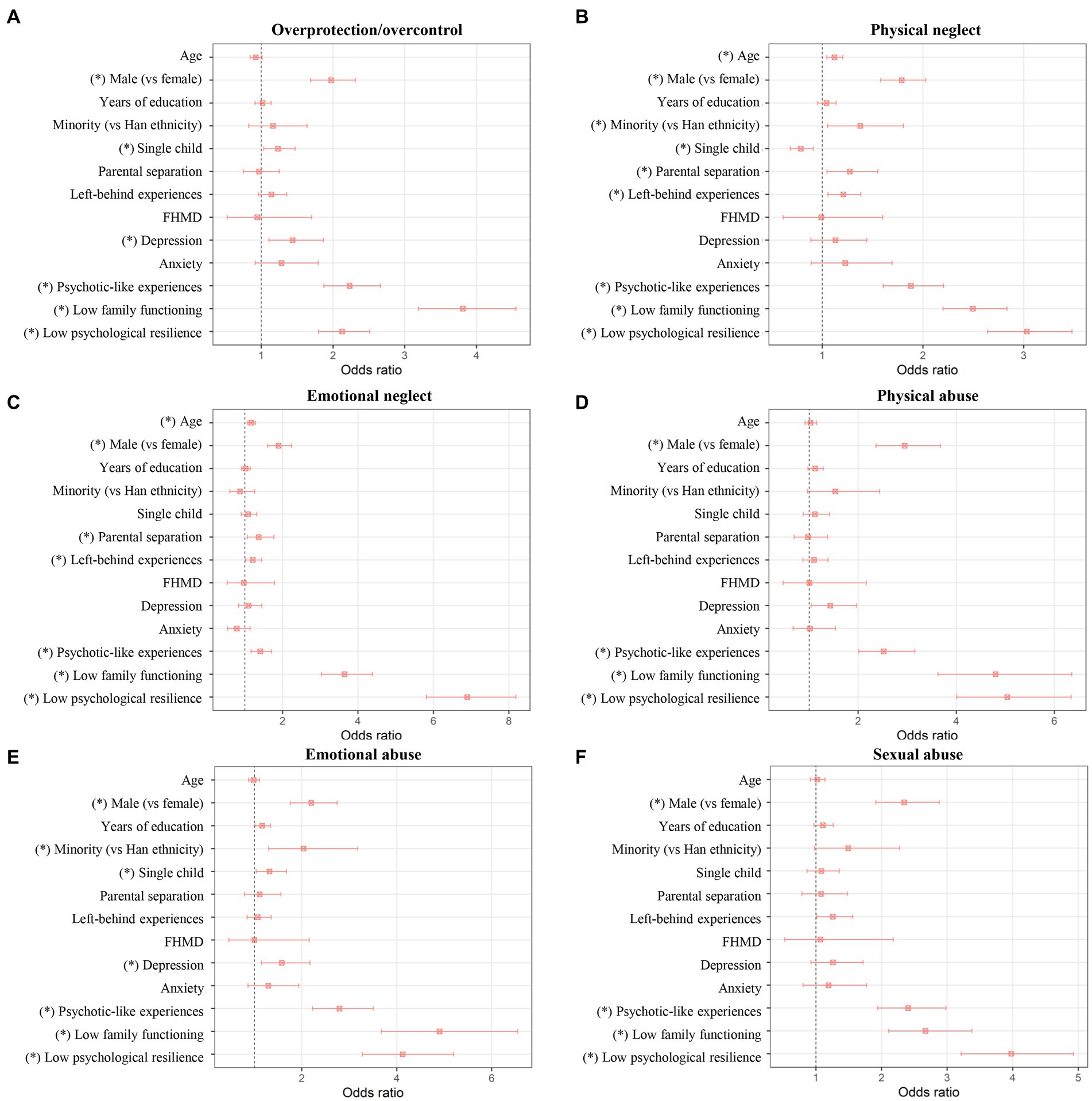

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 1A, after controlling for confounding factors in the logistic regression model, the following factors remained independently associated with OP/OC experiences: being male (odds ratio 1.973, 95% confidence interval 1.685–2.311, corrected p < 0.001), being a single child (odds ratio 1.232, 95% confidence interval 1.033–1.471, corrected p = 0.046), having depression (odds ratio 1.436, 95% confidence interval 1.105–1.866, corrected p = 0.018), having psychotic-like experiences (odds ratio 2.231, 95% confidence interval 1.872–2.659, corrected p < 0.001), having low family functioning (odds ratio 3.808, 95% confidence interval 3.188–4.549, corrected p < 0.001), and having low psychological resilience (odds ratio 2.126, 95% confidence interval 1.799–2.511, corrected p < 0.001). There were no statistically significant associations between OP/OC and the following factors: province, age, years of education, ethnicity, parental separation, left-behind experiences, family history of mental disorders, and anxiety (all corrected p > 0.05), after controlling for confounding factors.

Figure 1. Results of separate binary logistic regression analyses for factors associated with OP/OC (A) and for factors associated with other trauma subtypes (B–F). The odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are presented, and the “*” indicates a significant association with corrected p < 0.05. FHMD, family history of mental disorder; OP/OC, overprotection/overcontrol.

3.4. Supplementary analyses on other trauma subtypes

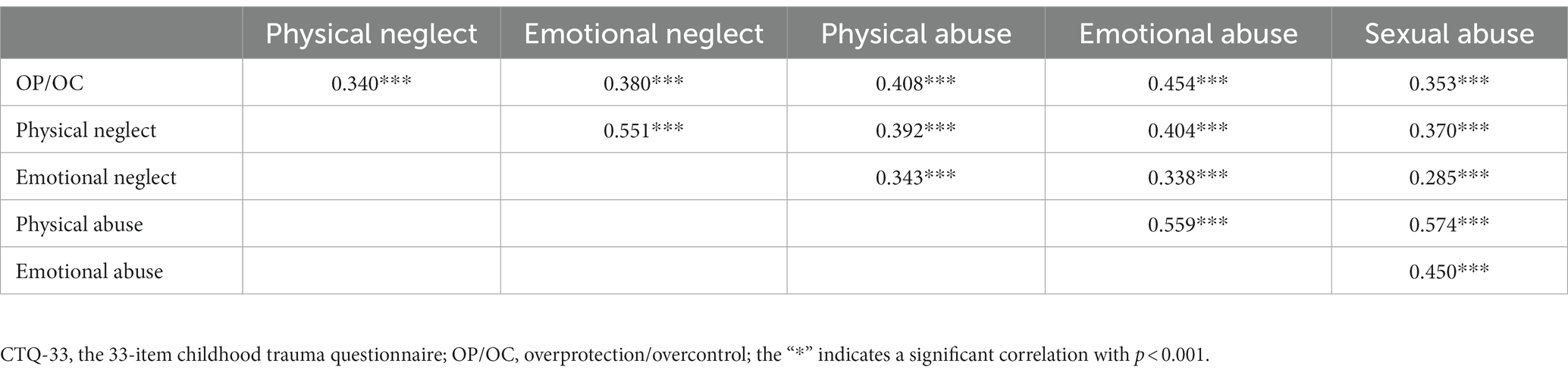

As shown in Table 4, significant positive correlations were found between the OP/OC score and scores of all other trauma subtypes in the CTQ-33 (all p < 0.001), confirming that OP/OC is highly positively associated with the other trauma subtypes. Results of the separate binary logistic regression analyses for factors associated with other trauma subtypes are shown in Figures 1B–F and Supplementary Tables S1–S5. Generally, it was found that the OP/OC and other trauma subtypes have both shared and unique associated factors (p < 0.05 after corrections). For example, all trauma subtypes including OP/OC were found to be positively associated with having psychotic-like experiences, having low family functioning, and having low psychological resilience; meanwhile, parental separation was found to be associated with only the physical neglect and emotional neglect experiences (Figure 1).

Table 4. Spearman correlation coefficients between the OP/OC score and scores of other trauma subtypes in the CTQ-33.

3.5. Supplementary analyses on possible sex differences

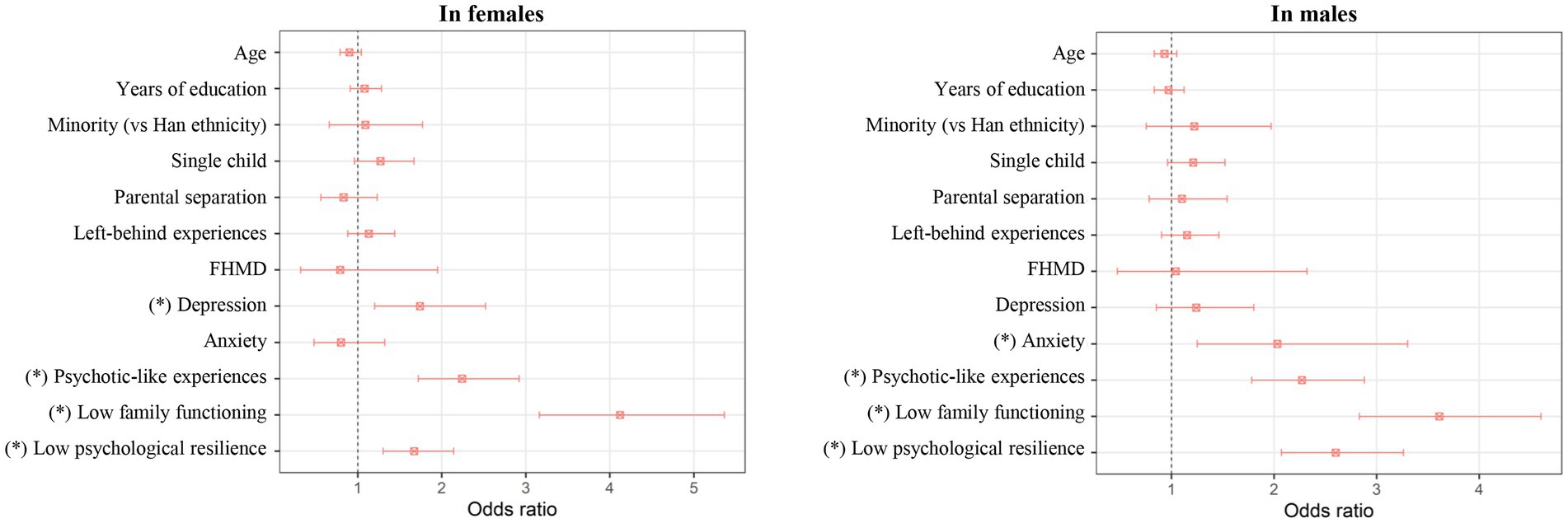

Results of separate logistic regression analyses in the female or male participants are shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Tables S6, S7. Generally, most of the associated factors of OP/OC were found to be consistent across the female and male participants (corrected p < 0.05 in both the two subsamples). The exceptions were that OP/OC was found to be associated with depression in only the female participants, and associated with anxiety in only the male participants (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Results of separate binary logistic regression analyses for factors associated with OP/OC in the female or male participants. The odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are presented, and the “*” indicates a significant association with corrected p < 0.05. FHMD, family history of mental disorder; OP/OC, overprotection/overcontrol.

3.6. Validation analysis

When using the cutoff points of OP/OC subscale score ≥12 or ≥14, 20.81% (1,212/5823) and 12.31% (717/5823) of the surveyed participants were categorized as having OP/OC experiences, respectively. The following factors were still found to be significantly associated with OP/OC when using the above different cutoff points: being male, being a single child, having depression, having psychotic-like experiences, having lower family functioning, and having lower psychological resilience (all corrected p < 0.05, see Supplementary Tables S8, S9).

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the possible associations between childhood OP/OC experiences and a series of socio-demographic and psychological factors in a nationwide sample of Chinese university students. Generally, our results suggested multiple non-modifiable (e.g., sex) and modifiable (e.g., family functioning) factors that could be independently associated with childhood OP/OC experiences. The OP/OC was also positively associated with all the other assessed trauma subtypes (abuses and neglects) in the CTQ-33. These results may provide initial evidence that childhood OP/OC experiences might have negative effects on the mental health in young populations.

In the current study, we first explored an appropriate cutoff point for the OP/OC subscale in CTQ-33 based on the statistical distributions in the surveyed sample. The cutoff was estimated at ≥13, and 15.63% (910/5823) of the surveyed participants were categorized as having OP/OC experiences according to such cutoff point. This prevalence is higher than those of physical abuse (8.59%, 500/5823), emotional abuse (8.07%, 470/5823) and sexual abuse (8.98%, 522/5823) but lower than those of physical neglect (33.52%, 1952/5823) and emotional neglect (16.26%, 947/5823) in the current sample. Note that all the identified associated factors of OP/OC were found to be unchanged when using different cutoff points at ≥12 and ≥14 (see Supplementary Tables S8, S9); therefore, the main conclusions in this study are unlikely to be largely driven by different choices in cutoff points.

Using the binary logistic regression model, we found that being male and being a single child are positively associated with childhood OP/OC experiences (Table 3). The observed sex effects on OP/OC are partly consistent with previous research showing sex differences in perceived parenting styles (59). We propose that several biological and social factors might account for such sex differences. For example, boys are favored over girls under the traditional ideology of son preference (60), which may lead to more focus on the boys than girls in some families. For the same reason, the children which are the single child of their family might attract more attention, and even overprotective parental strategies. Notably, we did not find significant associations between parental separation and OP/OC. One possible reason might be that children can be affected differently by whether their parents’ separation was amicable or conflict-ridden (61).

The regression analyses suggested that having depression is independently associated with OP/OC, even after adjusting for possible confounding effects of all other variables (Table 3). To the best of our knowledge, the findings in previously published studies are not totally consistent regarding the possible associations between OP/OC experiences and levels of depressive symptoms in later life. For example, one earlier research reported a strong association between negative parenting behaviors such as overprotection and later depressive symptom (8, 13). However, there is also research suggesting that paternal overcontrols can predict lower depressive symptoms (19). It is noteworthy that compared to most of these studies, our study has a much larger sample size and thus a higher statistical power. Therefore, this study may provide more solid evidence in support of the positive association between OP/OC and depression. In fact, multiple previous studies have also underlined OP/OC and other childhood traumas as predictors of dissociative depression alongside some linkage to the “traumatic narcissism” concept (13, 62), which are in line with our results and give a possible explanation for such relationship.

Our results also suggested that having psychotic-like experiences is independently associated with OP/OC (Table 3). To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first reports to suggest a positive relationship between OP/OC and psychotic-like experiences. Psychotic-like experiences are subclinical delusion-like or hallucination-like symptoms, which are related to increased risks of developing subsequent mental disorders (55). Previous studies have shown that some other subtypes of childhood trauma such as abuses and neglects would strongly increase the risks of developing schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (63, 64), which may be presented as having psychotic-like experiences in the early stage (65). Here, our results suggest that OP/OC, as another subtype of childhood trauma, is also associated with psychotic-like experiences.

Additionally, we found that childhood OP/OC experiences are associated with lower family functioning and lower psychological resilience (Table 3). Both family dysfunction (66) and decreased psychological resilience (67) have been linked to higher risks of developing mental problems. Lower family functioning was also associated with lower wellbeing and higher risks of substance use (68, 69). These findings, together with the observed significant effects of OP/OC on depression and psychotic-like experiences, may thus highlight the unignorable negative effects of OP/OC experiences on young people’s mental health.

As supplementary analyses, we have explored the possible differences in associated factors between OP/OC and other childhood trauma subtypes. It was found that some associated factors, such as having psychotic-like experiences, lower family functioning, and lower psychological resilience, were shared for all different trauma subtypes including OP/OC (Figure 1). Some differences were also found; for example, being a single child was positively associated with OP/OC but negatively associated with physical neglect; furthermore, having depression was positively associated with OP/OC and emotional abuse but not significantly associated with other trauma subtypes (Figure 1). Therefore, while being a subtype of traumatic experiences, there might be both common and unique features between the OP/OC and other trauma subtypes.

We have also explored the possible sex differences in relationships between OP/OC and other factors by performing analyses in the female and male participants separately. Generally, we found that most of the associated factors of OP/OC were consistent across the female and male participants; however, interestingly, the OP/OC experiences were associated with depression in only the female participants and associated with anxiety in only the male participants (Figure 2). There has been ample evidence for significant sex differences in multiple psychological characteristics, e.g., that females are more likely to be affected by depression (58, 70). Here, our results may partly help to further understand the sex differences in these psychological characteristics in the aspect of different influences of childhood OP/OC experiences.

This study has certain limitations. First, because of the nature of the cross-sectional survey, we are unable to establish the causality in relationships between OP/OC experiences and other factors. Therefore, further longitudinal studies are needed to address such a limitation. Second, several self-reported retrospective scales were used in this study, which may lead to memory-related biases. Third, the OP/OC experiences from one’s father, mother, or other family members were not distinguished in the CTQ-33, which might have different associated socio-demographic factors and psychological effects. This limitation may be overcome by using other scales in future studies. Last, while only healthy participants were included in the current study, further studies conducted in clinical populations with mental disorders may provide more important implications for understanding the negative effects of childhood OP/OC experiences.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study investigated the possible associated factors of childhood OP/OC experiences in young populations using the CTQ-33 and a relatively large, nationwide sample of Chinese university students. The main findings include that being male, being a single child, having depression, having psychotic-like experiences, having lower family functioning, and having lower psychological resilience were independently associated with childhood OP/OC experiences. The OP/OC was also positively associated with all the other trauma subtypes (abuses and neglects) in the CTQ-33; nevertheless, the OP/OC and other subtypes of trauma were found to have both shared and unique associated factors. Collectively, these results may provide initial evidence that childhood OP/OC experiences would have negative effects on young people’s mental health and highlight the great value of further investigations on OP/OC especially in participants with mental disorders. The results of this survey in healthy Chinese individuals might also provide baseline reference data for potential future studies on OP/OC in clinical populations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JZ, ZW, ZL, and YL contributed to the conception and design of the study. JZ, ZW, MC, MY, LZ, MS, DL, GC, QY, HT, CA, ZL, and YL contributed to the data acquisition. JZ, ZW, and YL contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. JZ and YL drafted the manuscript. HT, MS, and XH revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82201692 to YL, 82071506 to ZL, and 82101575 to MS), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (202102020702 to MS), Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (20224BAB206043 to XH), and Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2021JJ40851 to YL and 2021JJ40835 to XH).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all students who served as research participants. This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at medRxiv (71).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1238254/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^www.wjx.xn

References

1. Wood, JJ, McLeod, BD, Sigman, M, Hwang, W-C, and Chu, BC. Parenting and childhood anxiety: theory, empirical findings, and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2003) 44:134–51. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00106

2. Şar, V, Necef, I, Mutluer, T, Fatih, P, and Türk-Kurtça, T. A revised and expanded version of the Turkish childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ-33): overprotection-Overcontrol as additional factor. J Trauma Dissociation. (2021) 22:35–51. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2020.1760171

3. Holmbeck, GN, Johnson, SZ, Wills, KE, McKernon, W, Rose, B, Erklin, S, et al. Observed and perceived parental overprotection in relation to psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with a physical disability: the mediational role of behavioral autonomy. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2002) 70:96–110. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.96

4. Cella, S, Iannaccone, M, and Cotrufo, P. How perceived parental bonding affects self-concept and drive for thinness: a community-based study. Eat Behav. (2014) 15:110–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.10.024

5. Affrunti, NW, and Woodruff-Borden, J. Parental perfectionism and overcontrol: examining mechanisms in the development of child anxiety. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2015) 43:517–29. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9914-5

6. Miller, KF, Borelli, JL, and Margolin, G. Parent-child attunement moderates the prospective link between parental Overcontrol and adolescent adjustment. Fam Process. (2018) 57:679–93. doi: 10.1111/famp.12330

7. Albinhac, AMH, Jean, FAM, and Bouvard, MP. Study of parental bonding in childhood in children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Encéphale. (2019) 45:121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2018.02.004

8. Williamson, V, Creswell, C, Fearon, P, Hiller, RM, Walker, J, and Halligan, SL. The role of parenting behaviors in childhood post-traumatic stress disorder: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 53:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.005

9. Goschin, S, Briggs, J, Blanco-Lutzen, S, Cohen, LJ, and Galynker, I. Parental affectionless control and suicidality. J Affect Disord. (2013) 151:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.096

10. Lima, AR, Mello, MF, and Mari, JJ. The role of early parental bonding in the development of psychiatric symptoms in adulthood. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2010) 23:383–7. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833a51ce

11. Vigdal, JS, and Brønnick, KK. A systematic review of "helicopter parenting" and its relationship with anxiety and depression. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:872981. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.872981

12. Overbeek, G, ten Have, M, Vollebergh, W, and de Graaf, R. Parental lack of care and overprotection. Longitudinal associations with DSM-III-R disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2007) 42:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0115-6

13. Şar, V, and Türk-Kurtça, T. The vicious cycle of traumatic narcissism and dissociative depression among young adults: a trans-diagnostic approach. J Trauma Dissociation. (2021) 22:502–21. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2020.1869644

14. McLafferty, M, Armour, C, Bunting, B, Ennis, E, Lapsley, C, Murray, E, et al. Coping, stress, and negative childhood experiences: the link to psychopathology, self-harm, and suicidal behavior. Psych J. (2019) 8:293–306. doi: 10.1002/pchj.301

15. Shibata, M, Ninomiya, T, Anno, K, Kawata, H, Iwaki, R, Sawamoto, R, et al. Perceived inadequate care and excessive overprotection during childhood are associated with greater risk of sleep disturbance in adulthood: the Hisayama study. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:215. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0926-2

16. Ishii, J, Kodaka, F, Miyata, H, Yamadera, W, Seto, H, Inamura, K, et al. Associations between parental bonding during childhood and functional recovery in patients with schizophrenia. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0240504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240504

17. Zniva, R, Pauli, P, and Schulz, SM. Overprotective social support leads to increased cardiovascular and subjective stress reactivity. Biol Psychol. (2017) 123:226–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.12.009

18. Wu, Z, Liu, Z, Jiang, Z, Fu, X, Deng, Q, Palaniyappan, L, et al. Overprotection and overcontrol in childhood: An evaluation on reliability and validity of 33-item expanded childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ-33), Chinese version. Asian J Psychiatry. (2022) 68:102962. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102962

19. Basili, E, Zuffianò, A, Pastorelli, C, Thartori, E, Lunetti, C, Favini, A, et al. Maternal and paternal psychological control and adolescents' negative adjustment: a dyadic longitudinal study in three countries. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0251437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251437

20. Hemm, C, Dagnan, D, and Meyer, TD. Social anxiety and parental overprotection in young adults with and without intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2018) 31:360–8. doi: 10.1111/jar.12413

21. Spada, MM, Caselli, G, Manfredi, C, Rebecchi, D, Rovetto, F, Ruggiero, GM, et al. Parental overprotection and metacognitions as predictors of worry and anxiety. Behav Cogn Psychother. (2012) 40:287–96. doi: 10.1017/S135246581100021X

22. Bark, K, Ha, JH, and Jue, J. Examining the relationships among parental overprotection, military life adjustment, social anxiety, and collective efficacy. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:613543. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.613543

23. Van Petegem, S, Albert Sznitman, G, Darwiche, J, and Zimmermann, G. Putting parental overprotection into a family systems context: relations of overprotective parenting with perceived coparenting and adolescent anxiety. Fam Process. (2022) 61:792–807. doi: 10.1111/famp.12709

24. Long, Y, Chen, C, Deng, M, Huang, X, Tan, W, Zhang, L, et al. Psychological resilience negatively correlates with resting-state brain network flexibility in young healthy adults: a dynamic functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Ann Transl Med. (2019) 7:809. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.12.45

25. Chang, J-J, Ji, Y, Li, Y-H, Yuan, M-Y, and Su, P-Y. Childhood trauma and depression in college students: mediating and moderating effects of psychological resilience. Asian J Psychiatr. (2021) 65:102824. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102824

26. Bernstein, DP, Fink, L, Handelsman, L, Foote, J, Lovejoy, M, Wenzel, K, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. (1994) 151:1132–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132

27. Xiang, Z, Liu, Z, Cao, H, Wu, Z, and Long, Y. Evaluation on Long-term test-retest reliability of the short-form childhood trauma questionnaire in patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2021) 14:1033–40. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S316398

28. Tietjen, GE, Brandes, JL, Peterlin, BL, Eloff, A, Dafer, RM, Stein, MR, et al. Childhood maltreatment and migraine (part I). Prevalence and adult revictimization: a multicenter headache clinic survey. Headache. (2010) 50:20–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01556.x

29. Huang, D, Liu, Z, Cao, H, Yang, J, Wu, Z, and Long, Y. Childhood trauma is linked to decreased temporal stability of functional brain networks in young adults. J Affect Disord. (2021) 290:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.061

30. Asarnow, LD, Bei, B, Krystal, A, Buysse, DJ, Thase, ME, Edinger, JD, et al. Circadian preference as a moderator of depression outcome following cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia plus antidepressant medications: a report from the TRIAD study. J Clin Sleep Med. (2019) 15:573–80. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7716

31. Quintero Garzón, L, Hinz, A, Koranyi, S, and Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A. Norm values and psychometric properties of the 24-item demoralization scale (DS-I) in a representative sample of the German general population. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:681977. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.681977

32. Liu, D, Liu, X, Long, Y, Xiang, Z, Wu, Z, Liu, Z, et al. Problematic smartphone use is associated with differences in static and dynamic brain functional connectivity in young adults. Front Neurosci. (2022) 16:1010488. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.1010488

33. Kroenke, K, Spitzer, RL, and Williams, JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

34. Wang, W, Bian, Q, Zhao, Y, Li, X, Wang, W, Du, J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2014) 36:539–44. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.021

35. Levis, B, Benedetti, A, and Thombs, BD. Accuracy of patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. (2019) 365:l1476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1476

36. Spitzer, RL, Kroenke, K, Williams, JBW, and Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

37. Tong, X, An, D, McGonigal, A, Park, S-P, and Zhou, D. Validation of the generalized anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. (2016) 120:31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.11.019

38. Zhang, C, Wang, T, Zeng, P, Zhao, M, Zhang, G, Zhai, S, et al. Reliability, validity, and measurement invariance of the general anxiety disorder scale among Chinese medical university students. Front Psych. (2021) 12:648755. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.648755

39. Konings, M, Bak, M, Hanssen, M, van Os, J, and Krabbendam, L. Validity and reliability of the CAPE: a self-report instrument for the measurement of psychotic experiences in the general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2006) 114:55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00741.x

40. Sun, M, Wang, D, Jing, L, Xi, C, Dai, L, and Zhou, L. Psychometric properties of the 15-item positive subscale of the community assessment of psychic experiences. Schizophr Res. (2020) 222:160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.06.003

41. Zhang, J, Liu, Z, Long, Y, Tao, H, Ouyang, X, Wu, G, et al. Mediating role of impaired wisdom in the relation between childhood trauma and psychotic-like experiences in Chinese college students: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:655. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04270-x

42. Sun, M, Xue, Z, Zhang, W, Guo, R, Hu, A, Li, Y, et al. Psychotic-like experiences, trauma and related risk factors among "left-behind" children in China. Schizophr Res. (2017) 181:43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.09.030

43. Wang, D, Chen, H, Chen, Z, Liu, W, Wu, L, Chen, Y, et al. Current psychotic-like experiences among adolescents in China: identifying risk and protective factors. Schizophr Res. (2022) 244:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2022.05.024

44. Wu, Z, Liu, Z, Zou, Z, Wang, F, Zhu, M, Zhang, W, et al. Changes of psychotic-like experiences and their association with anxiety/depression among young adolescents before COVID-19 and after the lockdown in China. Schizophr Res. (2021) 237:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.08.020

45. Wu, Z, Jiang, Z, Wang, Z, Ji, Y, Wang, F, Ross, B, et al. Association between wisdom and psychotic-like experiences in the general population: a cross-sectional study. Front Psych. (2022) 13:814242. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.814242

46. Bukenaite, A, Stochl, J, Mossaheb, N, Schäfer, MR, Klier, CM, Becker, J, et al. Usefulness of the CAPE-P 15 for detecting people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: psychometric properties and cut-off values. Schizophr Res. (2017) 189:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.02.017

47. Smilkstein, G. The family APGAR: a proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Pract. (1978) 6:1231–9.

48. Wu, Z, Zou, Z, Wang, F, Xiang, Z, Zhu, M, Long, Y, et al. Family functioning as a moderator in the relation between perceived stress and psychotic-like experiences among adolescents during COVID-19. Compr Psychiatry. (2021) 111:152274. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152274

49. Huang, Y, Liu, Y, Wang, Y, and Liu, D. Family function fully mediates the relationship between social support and perinatal depression in rural Southwest China. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:151. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03155-9

50. Hai, S, Wang, H, Cao, L, Liu, P, Zhou, J, Yang, Y, et al. Association between sarcopenia with lifestyle and family function among community-dwelling Chinese aged 60 years and older. BMC Geriatr. (2017) 17:187. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0587-0

51. Campbell-Sills, L, and Stein, MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. (2007) 20:1019–28. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271

52. Connor, KM, and Davidson, JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. (2003) 18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113

53. Ye, ZJ, Qiu, HZ, Li, PF, Chen, P, Liang, MZ, Liu, ML, et al. Validation and application of the Chinese version of the 10-item Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC-10) among parents of children with cancer diagnosis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2017) 27:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.01.004

54. Guo, R, Sun, M, Zhang, C, Fan, Z, Liu, Z, and Tao, H. The role of military training in improving psychological resilience and reducing depression among college freshmen. Front Psych. (2021) 12:641396. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.641396

55. Wu, Z, Liu, D, Zhang, J, Zhang, W, Tao, H, Ouyang, X, et al. Sex difference in the prevalence of psychotic-like experiences in adolescents: results from a pooled study of 21, 248 Chinese participants. Psychiatry Res. (2022) 317:114894. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114894

56. Maeng, LY, and Milad, MR. Sex differences in anxiety disorders: interactions between fear, stress, and gonadal hormones. Horm Behav. (2015) 76:106–17. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.04.002

57. Wu, Z, Wang, B, Xiang, Z, Zou, Z, Liu, Z, Long, Y, et al. Increasing trends in mental health problems among urban Chinese adolescents: results from repeated cross-sectional data in Changsha 2016-2020. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:829674. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.829674

58. Rubinow, DR, and Schmidt, PJ. Sex differences and the neurobiology of affective disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2019) 44:111–28. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0148-z

59. Eun, JD, Paksarian, D, He, J-P, and Merikangas, KR. Parenting style and mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2018) 53:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1435-4

60. Shang, Z, Chi, B, and Liu, Z. Re-examination of son-preference based on attitude structure theory under the background of gender imbalance in China. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:1051638. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1051638

61. Beal, SJ, Wingrove, T, Mara, CA, Lutz, N, Noll, JG, and Greiner, MV. Childhood adversity and associated psychosocial function in adolescents with complex trauma. Child Youth Care Forum. (2019) 48:305–22. doi: 10.1007/s10566-018-9479-5

62. Sar, V, Akyüz, G, Oztürk, E, and Alioğlu, F. Dissociative depression among women in the community. J Trauma Dissociation. (2013) 14:423–38. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2012.753654

63. Chaiyachati, BH, and Gur, RE. Effect of child abuse and neglect on schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. (2021) 206:173195. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2021.173195

64. Vieira, IS, Pedrotti Moreira, F, Mondin, TC, Cardoso, TA, Jansen, K, Souza, LDM, et al. Childhood trauma and bipolar spectrum: a population-based sample of young adults. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. (2020) 42:115–21. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2019-0046

65. Read, J, van Os, J, Morrison, AP, and Ross, CA. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2005) 112:330–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00634.x

66. Wiegand-Grefe, S, Sell, M, Filter, B, and Plass-Christl, A. Family functioning and psychological health of children with mentally ill parents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:1278. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071278

67. Ungar, M, and Theron, L. Resilience and mental health: how multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:441–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30434-1

68. Mersky, JP, Topitzes, J, and Reynolds, AJ. Impacts of adverse childhood experiences on health, mental health, and substance use in early adulthood: a cohort study of an urban, minority sample in the U.S. Child Abuse Negl. (2013) 37:917–25. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.011

69. Sitnick, SL, Shaw, DS, and Hyde, LW. Precursors of adolescent substance use from early childhood and early adolescence: testing a developmental cascade model. Dev Psychopathol. (2014) 26:125–40. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000539

70. Bangasser, DA, and Cuarenta, A. Sex differences in anxiety and depression: circuits and mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2021) 22:674–84. doi: 10.1038/s41583-021-00513-0

Keywords: childhood trauma, overprotection, overcontrol, mental health, depression, psychotic-like experience

Citation: Zhang J, Wu Z, Tao H, Chen M, Yu M, Zhou L, Sun M, Lv D, Cui G, Yi Q, Tang H, An C, Liu Z, Huang X and Long Y (2023) Profile and mental health characterization of childhood overprotection/overcontrol experiences among Chinese university students: a nationwide survey. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1238254. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1238254

Edited by:

Melissa Kimber, McMaster University, CanadaReviewed by:

Yi Nam Suen, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaDongfang Wang, South China Normal University, China

Vedat Şar, Koç University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2023 Zhang, Wu, Tao, Chen, Yu, Zhou, Sun, Lv, Cui, Yi, Tang, An, Liu, Huang and Long. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaojun Huang, eGlhb2p1bmg5QDE2My5jb20=; Yicheng Long, eWljaGVuZ2xvbmdAY3N1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jiamei Zhang

Jiamei Zhang Zhipeng Wu

Zhipeng Wu Haojuan Tao

Haojuan Tao Min Chen3

Min Chen3 Miaoyu Yu

Miaoyu Yu Liang Zhou

Liang Zhou Cuixia An

Cuixia An Zhening Liu

Zhening Liu Yicheng Long

Yicheng Long