- Quzhou TCM Hospital at the Junction of Four Provinces Affiliated to Zhejiang Chinese Medical University/Quzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Quzhou, China

Objective: To analyse the influencing factors of anxiety, disease uncertainty and acute stress response in patients with acute ischaemic stroke, and to verify the mediating role of anxiety in the post-epidemic era.

Methods: 240 patients with acute ischaemic stroke were selected from a tertiary hospital in Wuhan City and investigated by questionnaire and convenience sampling methods.

Results: The total anxiety score, disease uncertainty and acute stress reaction were at moderate levels. Anxiety was positively correlated with illness uncertainty, and anxiety and acute stress response were negatively correlated. Multiple linear regression analysis showed that Sickness uncertainty, acute stress response, age, and work status influenced anxiety. Anxiety mediated the prediction of Sickness uncertainty and acute stress response, with the mediating effect accounting for 35.6% of the total effect.

Conclusion: Disease uncertainty in patients with acute ischaemic stroke in the post-epidemic era directly affects the acute stress response and indirectly through anxiety.

1. Introduction

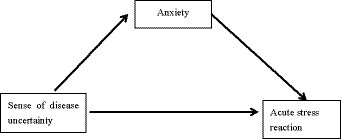

Acute ischaemic stroke is a sudden interruption of blood supply to local brain tissue due to various reasons, resulting in necrosis of local brain tissue due to ischemia and hypoxia, followed by symptoms of corresponding neurological deficits (1). There are about 3 million new cases of stroke in China every year. The prevalence of stroke is above 60 years of age, with an average annual increase of 8.3% in the number of first-ever strokes between the ages of 40 and 70 years (2). It is characterised by high morbidity, mortality, disability, and complications, and the incidence and recurrence rates are still high, causing patients to suffer from disease uncertainty, stress, anxiety, and fear, which severely limit their ability to care for themselves and affect their quality of life (3–6). Disease uncertainty is a chronic and pervasive source of psychological distress in patients and plays an important role in stroke recovery (7). Mullins (8, 9) and other related studies have shown that disease uncertainty is a predictor of the development of psychological distress and can be used as a predictor of anxiety. Acute stress is a stress response that is exhibited by an individual between 2 and 28 days after personally experiencing, witnessing, or facing a traumatic event with a threat of death or serious injury to themselves or others (10). Patients with anxiety and depressive symptoms have a more severe acute stress response (11, 12). Anxiety is a common psychological symptom in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (13–20), and Li et al. (21) showed that 16% of patients with acute ischaemic stroke had anxiety. Therefore, the present study explored the correlation between anxiety, disease uncertainty and acute stress response and tested the hypothesis that anxiety has a mediating role in disease uncertainty and acute stress response. The aim was to reduce negative psychology in patients with acute ischaemic stroke in the post-pandemic era. The mediating role in this study refers to whether the effect of illness uncertainty on the acute stress response is examined through the mediating variable anxiety before it affects the acute stress response; that is, whether there is a relationship of illness uncertainty → anxiety → acute stress response, as such.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study is a cross-sectional study in a non-experimental study.

2.2. Study population

The subjects of this study were acute ischaemic stroke patients in a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China.

2.2.1. Inclusion criteria

(1) Meeting the diagnostic criteria of the Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute ischaemic stroke.

(2) Patients with acute ischaemic stroke of first onset.

(3) clear consciousness.

2.2.2. Exclusion criteria

(1) Combination of severe organic lesions of other organs.

(2) Pre-existing psychological and psychiatric disorders.

(3) Unwillingness to cooperate in the middle of the procedure.

2.2.3. Calculation of sample size

The rough estimation method proposed by Li Zheng (22) was used to calculate the sample content, with 12 items of the general demographic data questionnaire, two dimensions of the Illness Uncertainty Scale, five dimensions of the Chinese version of the Stanford Acute Stress Questionnaire, and one dimension of the State Anxiety Scale, for a total of 20 variables, and the sample size was taken as 10 times the number of variables, i.e. the sample size = 20*10*1.2 = 240, and the final sample size was determined to be 240 cases.

2.3. Research tools

General Information Questionnaire, Illness Uncertainty Inventory (MUIS-A) (23), Acute Stress Response Questionnaire (SASRQ) (24), State Anxiety Inventory (S-AI) (25).

2.4. Theoretical basis

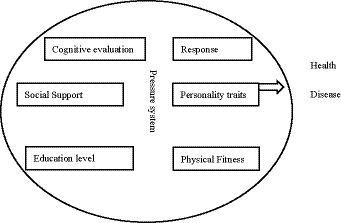

This study is based on the psychological stress model (resilience in process model), and Jiang Qianjin proposed the concept of ‘stress multifactor system’ through the study of multiple factors of psychological stress (26, 27), that is, stress is not a simple cause-effect or stimulus–response process. Rather, it is a multi-factor interaction, feedback regulation and control system composed of stressor, stress response and other related factors, which makes stress a bio-psycho-social integrated system concept (Figure 1).

2.5. Research framework

Based on psychological stress theory, this study makes the following hypotheses (1) illness uncertainty has a direct predictive effect on anxiety; (2) illness uncertainty has a direct predictive effect on acute stress response; (3) acute stress response has a direct predictive effect on anxiety; (4) acute stress response has a mediating role in illness uncertainty and anxiety, and the framework of this study is shown in Figure 2.

2.5.1. Neurophysiological mechanisms

anxiety is seen as being most often generated by concurrent and equivalent activation of fear (or frustration) and reward system. If uncertainty disappears, anxiety should give way to satisfaction or joy (if winning) or some negative emotions ranging from sadness to fear. The more active reward system is in a situation of uncertainty, the higher should be anxiety-related arousal (28).

In reinforcement sensitivity theory, Gray proposed several conceptual neural systems, which include: behavioural approach system (BAS), which is a positive behavioural feedback system; behavioural inhibition system (BIS), which is a negative behavioural feedback system; confrontation/flight system (FFS), which has the same function as the behavioural inhibition system but differs from the behavioural inhibition system in that it is more sensitive to conditioned aversions. a negative behavioural feedback system; and the fight/flight system (FFS), which has the same function as the behavioural inhibition system, but differs from the behavioural inhibition system in that it is more sensitive to unconditional aversions and is responsible for the regulation of emotions such as fear and anxiety. Gray et al. (29) revised the three systems in 2000, replacing the confrontation/flight/freeze system (FFFS) with the fight/flight/freeze system (FFFS), which is sensitive to punishments, rewards, and conflicting stimuli, respectively.

2.6. Data collection and processing

We communicated with the study subjects and their families, explained the purpose and significance of the study and the method of filling out the questionnaires, and collected the questionnaires on the spot. 320 questionnaires were distributed in this study, 300 were collected, 288 were valid and 12 were invalid, with a valid recovery rate of 96%.

This study used SPSS26.0 for data analysis

(1) The general information of the patients and the count data in the scores of each scale were expressed by frequency (n) and percentage (%), and the measurement data were expressed by mean ± standard deviation.

(2) Differences between different patients in terms of scores of each scale were analysed by two independent samples t-test and ANOVA.

(3) Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to explore the relationship between anxiety, disease uncertainty, and acute stress response.

(4) Multiple linear regression analysis was used to explore the effects between the three.

(5) ProceSS3.5 macro program was used to further test the mediating effect of anxiety between illness uncertainty and acute stress response.

3. Results

3.1. General information status in the post-epidemic era

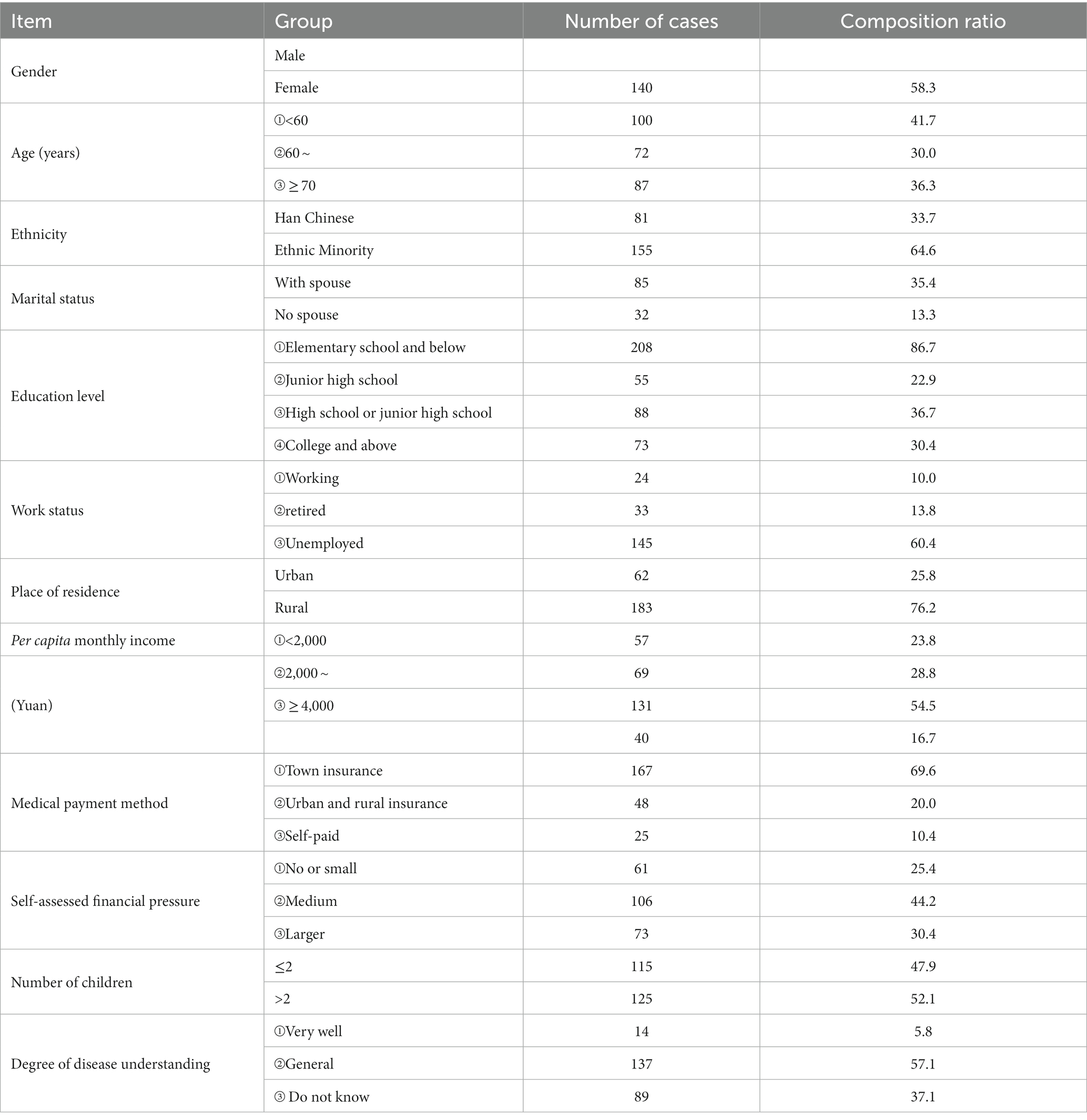

Males accounted for 58.3 percent of the total and females for 41.7 percent. The age distribution was over 50 years old, Han Chinese patients accounted for 64.6 percent, and married patients accounted for 86.7 percent. The place of residence was mostly urban, occupying 76.2%, the cultural level was mainly at junior high school, high school or secondary school level, the working status was mostly retired, occupying 60.4%, the per capita monthly income of the family was mostly in the number of people in the range of 2,000-4,000, occupying 54.4, 69.6% of the health care payment method was urban workers’ insurance, the self-assessment of the economic pressure was moderate, and the number of children >2 or ≤ 2 had a small difference. 57.1% had average knowledge of the disease. See Table 1 for details.

3.2. Status of disease uncertainty in the post-epidemic era

3.2.1. Disease uncertainty score in the post-epidemic era

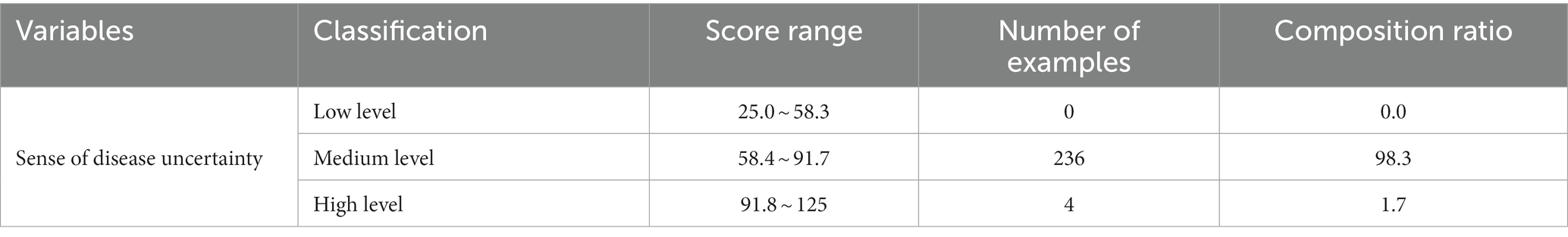

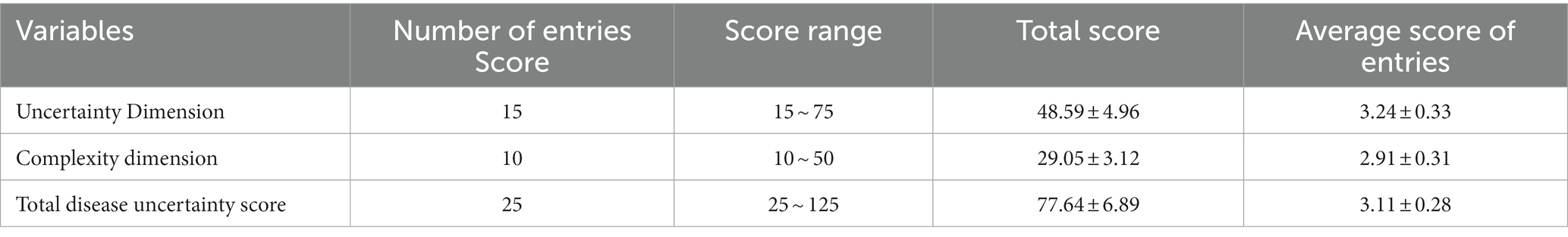

Compared to the complexity dimension scores, the uncertainty dimension scores were high with a total score (48.59 ± 4.96) and the total disease uncertainty score (77.64 ± 6.89), 98.3% of the patients had a moderate level of disease uncertainty. Only 1.7% of patients were at a high level. The details are shown in Tables 2, 3.

Table 2. Total disease uncertainty scores and scores of each dimension in the study subjects (n = 240, ± s).

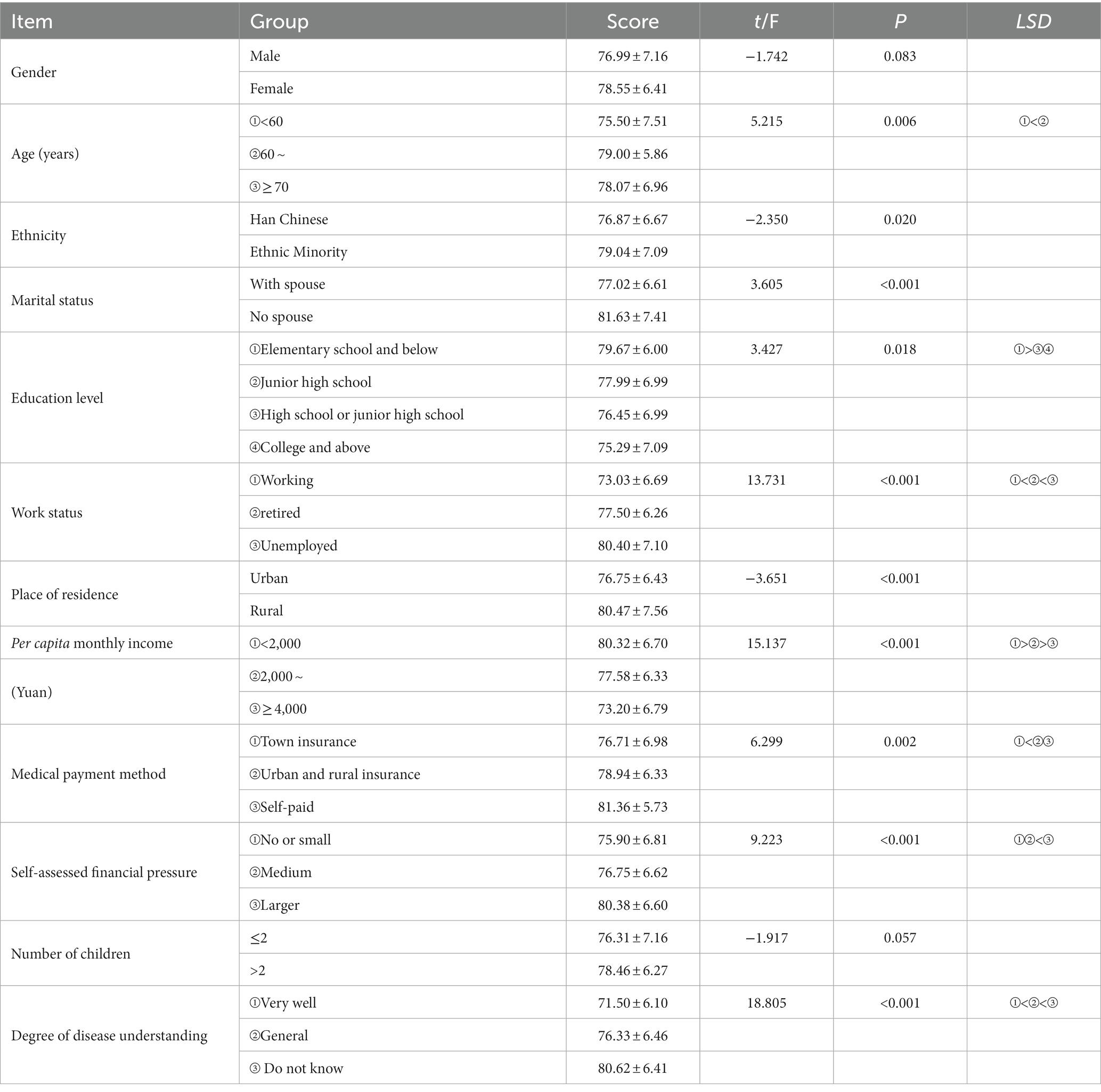

3.2.2. Single-factor analysis of disease uncertainty in the post-epidemic era

Age in the 60–70 years old disease uncertainty scored the highest score of 79.00 ± 5.86 points, ethnic minorities scored 79.04 ± 7.09 points, patients without spouses scored 79.04 ± 7.09 points, literacy in primary school culture scored 79.67 ± 6.00 points, joblessness scored 80.40 ± 7.10 points, most of the place of residence in rural areas, per capita income per month is less than 2,000 yuan, and most of them are self-paying patients with a score of 81.36 ± 5.73 points, self-assessed economic pressure, the difference in the number of children is small, and the patients do not understand their own diseases, with a score of 80.62 ± 6.41 points, see Table 4 for details.

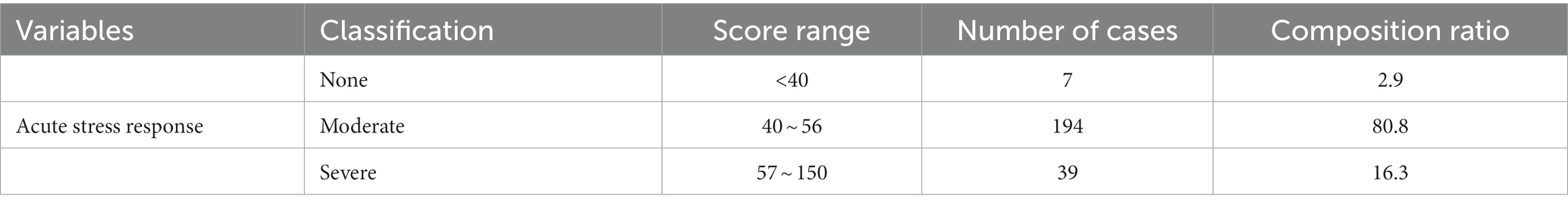

3.3. Acute stress response status in the post-epidemic era

3.3.1. Acute stress response score in the post-epidemic era

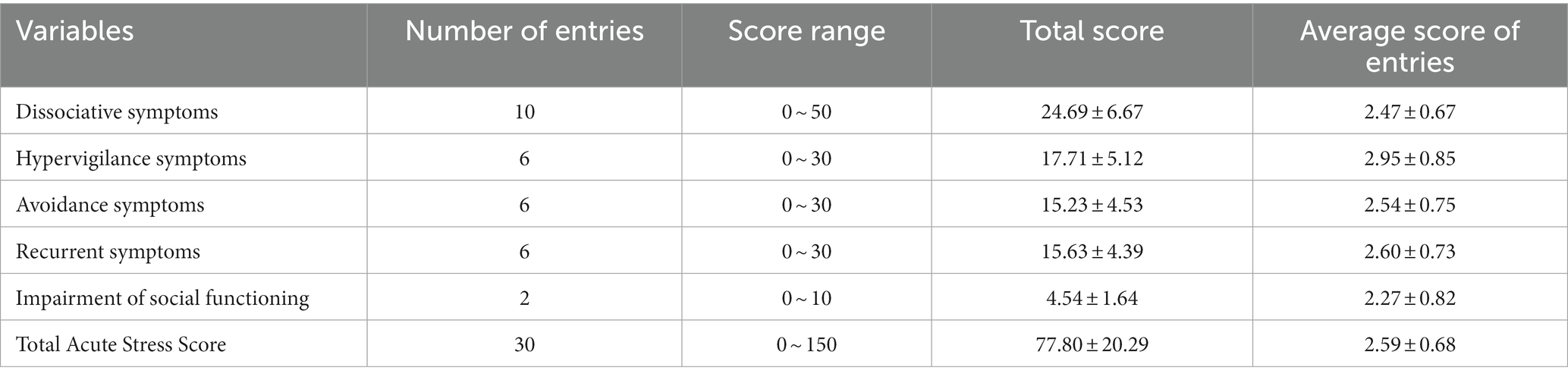

The scores for each dimension were as follows, dissociative symptoms (24.69 ± 6.67) with the highest score, hypervigilant symptoms (17.71 ± 5.12), avoidance symptoms (15.23 ± 4.53), re-experiencing symptoms (15.63 ± 4.39), impairment of social functioning (4.54 ± 1.64) with the lowest score, and the total score of acute stress reaction (77.80 ± 20.29) points, detailed results are shown in Tables 5, 6.

Table 5. Total score of acute stress response and scores of each dimension in the study subjects (n = 240, ± s).

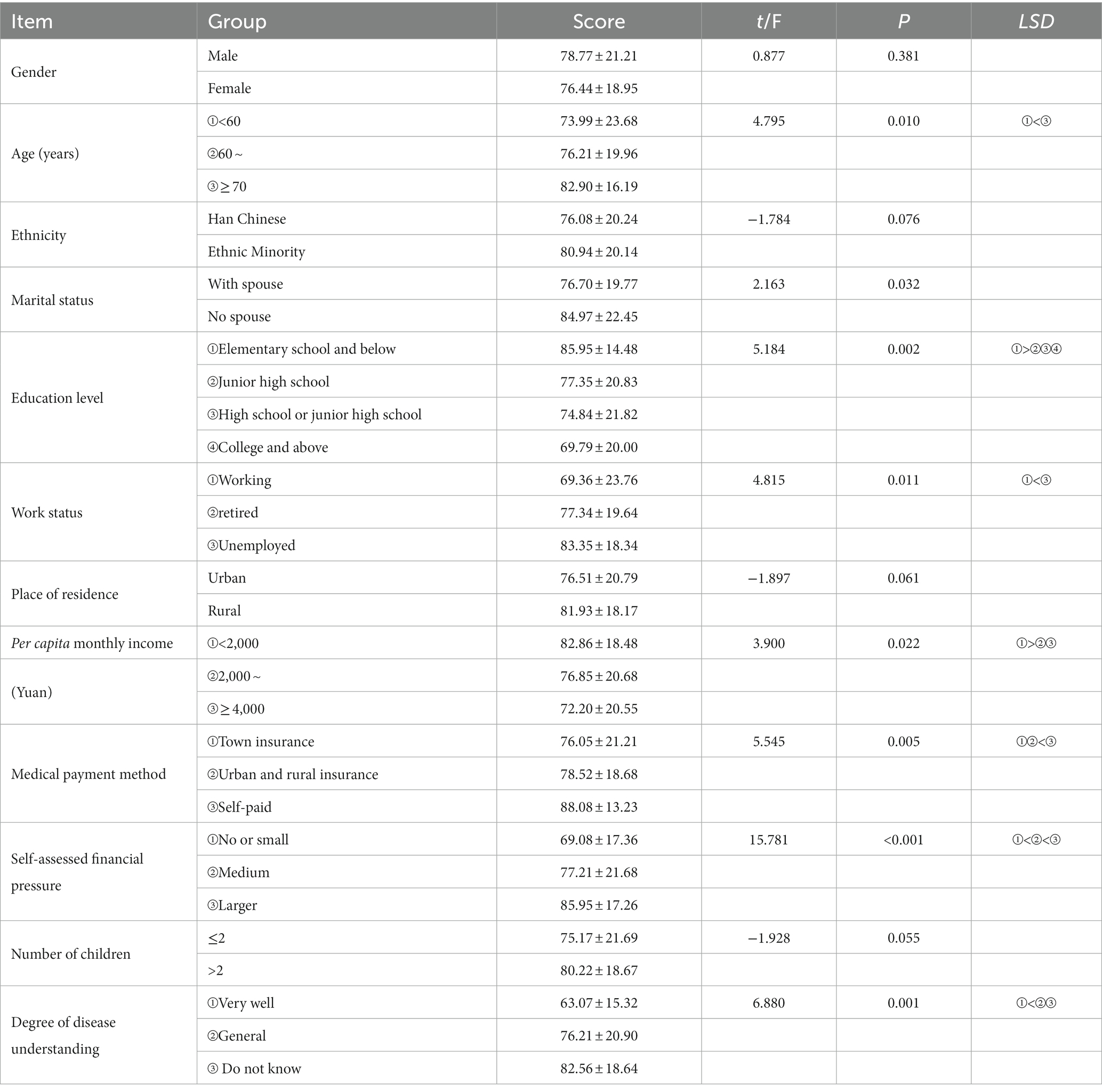

3.3.2. Univariate analysis of acute stress response in the post-epidemic era

Age ≥ 70 years of age had the highest acute stress score of 82.90 ± 16.19 points, patients without spouses scored 84.97 ± 22.45 points, literacy in primary school culture scored 85.95 ± 14.48 points, joblessness scored 83.35 ± 18.34 points, the per capita monthly income was less than 2,000 yuan, scored 82.86 ± 18.48 points, and most of them were self-funded patients, self-assessed economic pressure, the difference in the number of children is small, patients do not understand their own disease, score 82.56 ± 18.64 points, see Table 7.

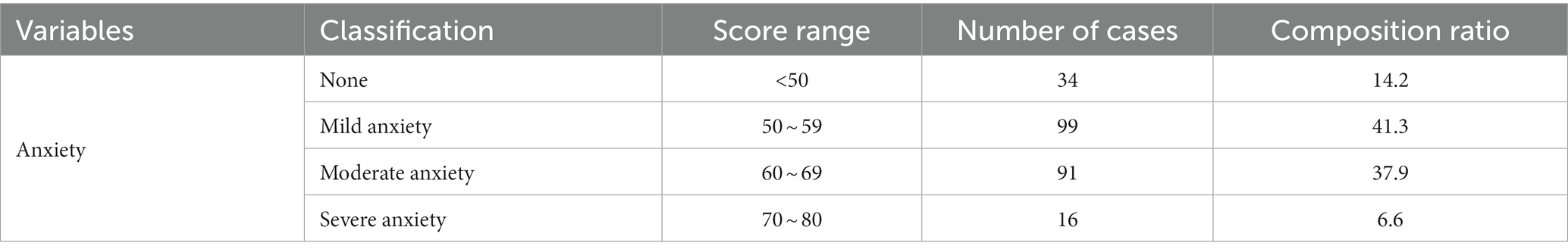

3.4. Anxiety status in the post-epidemic era

3.4.1. Anxiety score situation in the post-epidemic era

Thirty four were patients with no anxiety (14.2%), 99 with mild anxiety (41.3%). Ninety one with moderate anxiety (37.9%). Sixteen patients with severe anxiety (6.6%) accounted for a smaller percentage. See Table 8 for details.

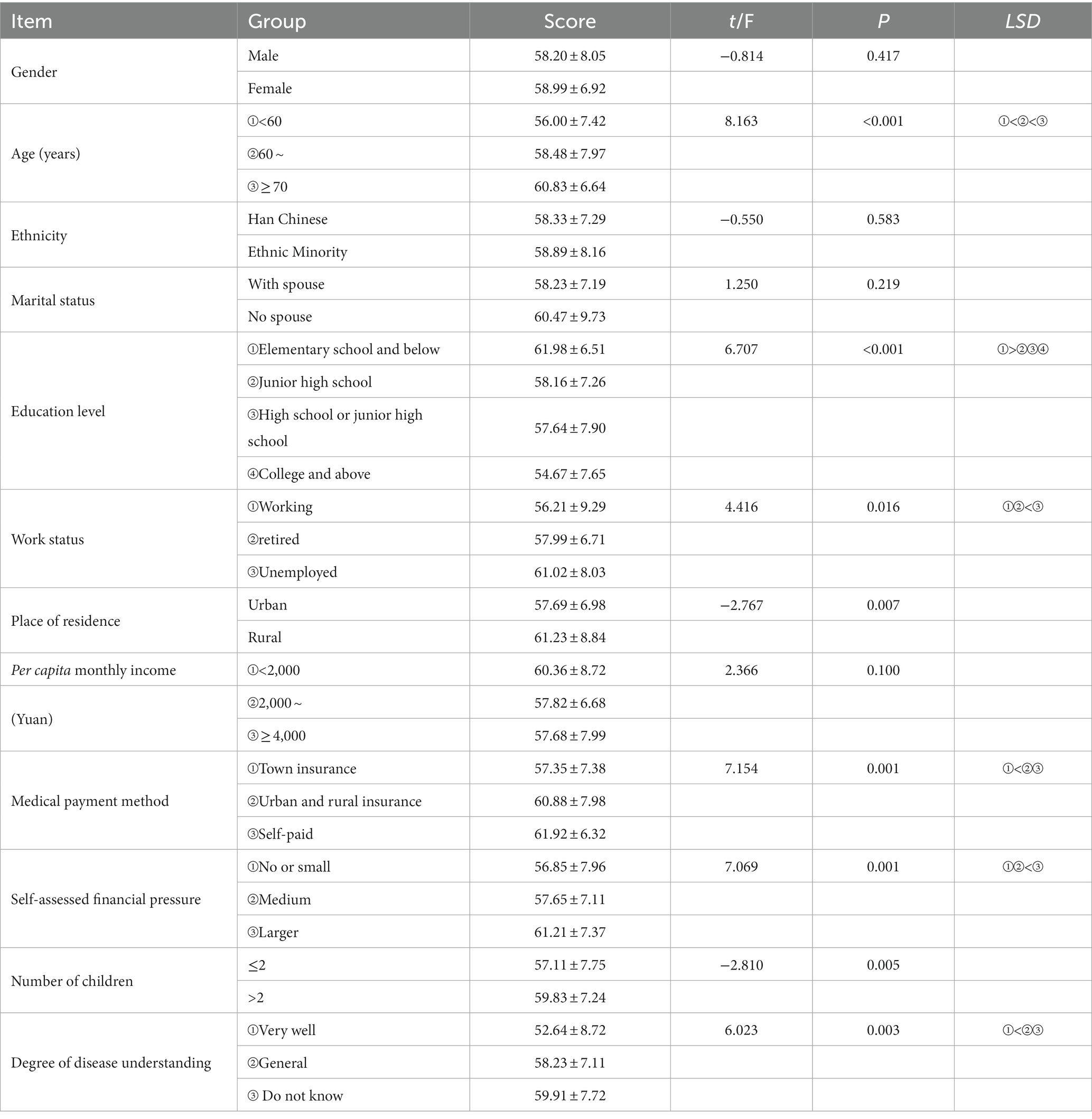

3.4.2. Univariate analysis of anxiety in the post-epidemic era

Age ≥ 70 years old had the highest anxiety score, 60.83 ± 6.64 points, literacy in primary school education score 61.98 ± 6.51 points, jobless status score 61.02 ± 8.03 points, and most of them were self-paying patients with a score of 61.92 ± 6.32 points, and self-assessment of economic stress was high, 61.21 ± 7.37 points. The difference in the number of children was small, and the patients were unaware of their disease, scoring 59.91 ± 7.72 points, as shown in Table 9.

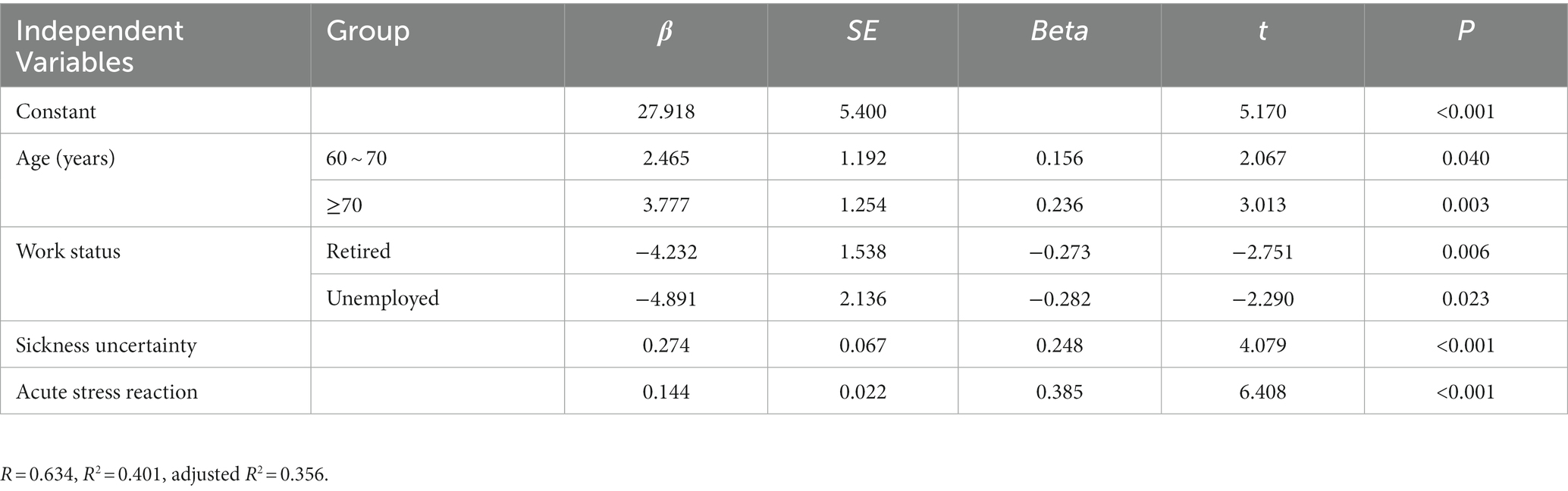

3.5. Factors influencing anxiety in patients with acute ischaemic stroke in the post-epidemic era

The regression equation was: anxiety’ Y = 27.918 + 6.242 × age − 9.123 × work status +0.274 × disease uncertainty +0.144 × acute stress response. The coefficient of determination R2 = 0.401, the coefficient of adjustment R2 = 0.356, and the ANOVA results with F = 8.760 and p = 0.000 indicate that the four included independent variables were able to explain 40.1% of the variance in anxiety symptoms of the study subjects, as detailed in Table 10.

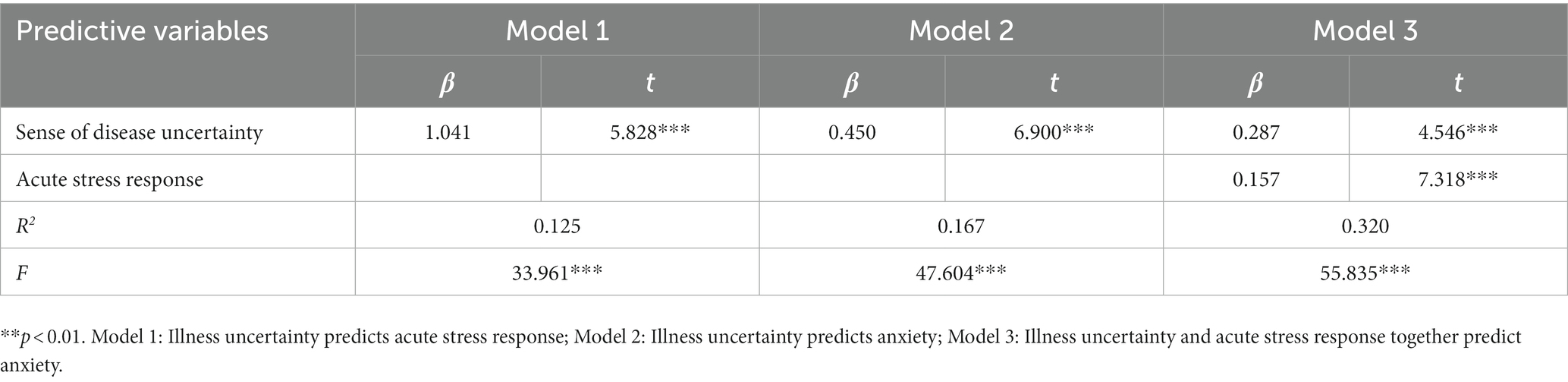

3.6. Mediating effect test for acute stress response in the post-epidemic era

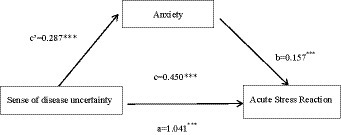

The results of the analysis showed that acute stress response partially mediated the prediction of anxiety by illness uncertainty. The variance of anxiety explained by acute stress response was sqrt (0.320–0.167) = 0.391 (39.1%), and the contribution of the mediating effect to the total effect was: Effect M = ab/c = 1.041 × 0.157/0.450 = 0.363 (36.3%), and the details are shown in Table 11 and Figure 3.

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of factors affecting the sense of uncertainty about disease in the post-epidemic era

The more severe the sense of disease uncertainty was in patients over 60 years old, rural health insurance, no spouse, ethnic minority, and no knowledge of the disease. This is basically consistent with the findings of Wang Xiaoxiao (30–33) and others. Patients with high education had greater confidence in curing the disease, which is basically consistent with the findings of Wang Qiuling (34). Those who were employed scored significantly lower in disease uncertainty than those who were unemployed, which was inconsistent with the findings of foreign studies (35, 36). We hypothesise that this may be due to the fact that our social system, medical system, and cultural background are different from the situation of foreign patients. Patients with high per capita monthly household income are also better able to cope with acute ischaemic stroke and disability, which is largely similar to the results reported by Ni (37) and Kim et al. (38).

4.2. Analysis of factors influencing acute stress in the post-epidemic era

Older, spouseless patients, with no one to support them emotionally and spiritually and with only one person to support them financially, can develop a strong sense of isolation, triggering acute stress reactions, which is consistent with the findings of Wu Wei et al. (39). Highly educated and working patients can adapt to stressful events in a timely manner, which is generally consistent with the results reported by Suliman (40) and Song Qiong et al. (41). However, it is not consistent with the findings of Pingping Liu (42). Patients who are self-paying and self-assessed as financially stressed need to pay high medical costs in full and experience strong acute stress reactions in the face of unknown disease progression, which is generally consistent with the findings of Song Qiong et al. (43, 44). Therefore, on the issue of family support, during the hospitalisation of patients without spouses, healthcare workers should carry out more communication and exchanges to alleviate patients’ anxiety and loneliness, while relevant outdoor activities can be carried out in the community after discharge to enrich life. In terms of economic problems, it is recommended to increase the reimbursement ratio of medical insurance for sick families, and hospitals can carry out social donations for patients in critical condition and family difficulties to help them solve their economic pressure.

4.3. Analysis of the factors influencing anxiety in the post-epidemic era

The incidence of anxiety was significantly higher in patients who were older, had two or more children, were self-paying, had rural health insurance, had low education, and did not understand the disease (45–51). We hypothesise that this may be due to the fact that the number of children is an important measure of the patient’s emotional and spiritual support situation, that children may be in contentious conflict over the cost and responsibility of treatment, and that patients feel a heavy burden on their children.

4.4. Correlation analysis of sickness uncertainty, acute stress reaction and anxiety in the post-epidemic era

Sickness uncertainty is positively correlated with post-traumatic stress disorder, which is consistent with related scholars’ studies (52–57), and sickness uncertainty is a risk factor for the occurrence of post-traumatic stress disorder (55–58). There was a positive correlation between illness uncertainty and anxiety, which is consistent with the findings of Wong et al. (59). There was a positive correlation between acute stress response and anxiety, which is consistent with the findings of Meixiang Yin (60) and others.

4.5. Key influences on anxiety in the post-epidemic era

Age is an influencing factor for patients’ anxiety, and we hypothesise that it may be due to the decreased psychological flexibility of the elderly and the accumulated physical and mental burdens that aggravate their feelings of loneliness and helplessness. The inability to adapt to a new social role after retirement and a severe sense of loss may trigger other physical illnesses. Failure to understand the development and regression of the disease, resulting in negative psychological anxiety. Stimulating the organism to produce stress mechanisms, patients have strong stress reactions and anxiety due to unacceptability and difficulty in adapting.

4.6. The mediating role of anxiety in the post-epidemic era

The acute stress response partially mediates the prediction of anxiety by disease uncertainty, with the acute stress response explaining 39.1% of the variance in anxiety and the mediating effect contributing 36.3% of the total effect. When patients have illness uncertainty, different levels of acute stress responses affect patients’ anxiety levels, acute stress responses positively predict patients’ anxiety symptoms, and it was found that the stronger the patients’ illness uncertainty, the more pronounced the acute stress responses, thus aggravating patients’ anxiety to some extent, which is basically consistent with the findings of Hammen (61) on the predictive role of acute stress on anxiety. This study is based on the principles of the 2018 CANMAT/ISBD Guidelines for the Management of Bipolar Disorder published in March 2018 in Bipolar Disorders, the official journal of the ISBD, which is a major and comprehensive guideline update and revision after the 2013 edition of the Guidelines, which comprehensively evaluates the evidence-based evidence that has been added in recent years, and proposes new clinical recommendations, based on the full co-operation between CANMAT and the ISBD. Reduce anxiety in patients already burdened with stroke based on this guideline. Therefore, medical and nursing staff should focus on the psychological state of patients, actively guide patients to express their disease uncertainty, provide timely relief and excretion of acute stress reactions generated by patients, and enhance patients’ confidence to achieve the goal of reducing patients’ psychological burden and relieving anxiety.

The main hypothesis of the present study was confirmed, There was a positive correlation between anxiety and illness uncertainty, a positive correlation between anxiety and acute stress response, a positive correlation between illness uncertainty and acute stress response, and a partial mediating role of anxiety in illness uncertainty and acute stress response. There is such a relationship as illness uncertainty → anxiety → acute stress response.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

HT is responsible for literature review, data collection, data statistics, and writing.

Funding

This work was supported by the Mechanism study of Yanghe Tang regulating synovial cell fibrosis through IL-33/ST2/MMPs signalling pathway in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis (2023K156).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Summary of the China stroke prevention and control report 2019. Chinese J Cerebrovascular Dis. (2020) 17:272–81.

2. Wang, P, Wang, Y, Zhao, X, du, W, Wang, A, Liu, G, et al. In-hospital medical complications associated with stroke recurrence after initial ischemic stroke: a prospective cohort study from the China National Stroke Registry. Medicine. (2016) 95:e4929. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004929

3. Pan, Y, Jing, J, Chen, W, Meng, X, Li, H, Zhao, X, et al. Risks and benefits of clopidogrel–aspirin in minor stroke or TIA: time course analysis of CHANCE. Neurology. (2017) 88:1906–11. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003941

4. Wang, Y, Chen, W, Lin, Y, Meng, X, Chen, G, Wang, Z, et al. Ticagrelor plus aspirin versus clopidogrel plus aspirin for platelet reactivity in patients with minor stroke or transient ischaemic attack: open label, blinded endpoint, randomised controlled phase II trial. BMJ. (2019) 365:2211:l2211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2211

5. Meng, Y. Study on the degree of health function loss, caregiver negative emotions and their correlation in patients with ischemic stroke. China: Henan University (2013).

6. Ahmadi, M, Gheibizadeh, M, Rassouli, M, Ebadi, A, Asadizaker, M, and Jahanifar, M. Experience of uncertainty in patients with thalassemia major: a qualitative study. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. (2020) 14:237–47. doi: 10.18502/ijhoscr.v14i4.4479

7. Mullins, AJ, Gamwell, KL, Sharkey, CM, Bakula, DM, Tackett, AP, Suorsa, KI, et al. Illness uncertainty and illness intrusiveness as predictors of depressive and anxious symptomology in college students with chronic illnesses. J Am Coll Health. (2017) 65:352–60. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2017.1312415

8. Hagen, KB, Aas, T, Lode, K, Gjerde, J, Lien, E, Kvaløy, JT, et al. Illness uncertainty in breast cancer patients: validation of the 5-item short form of the Mishel uncertainty in illness scale. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2015) 19:113–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.10.009

9. Liu, QS, Wang, J, and Cheng, X. Analysis of factors influencing the occurrence of acute stress disorder in patients with craniocerebral injury and nursing countermeasures. Qilu J Nursing. (2021) 27:140–2.

10. Xue, Q. Investigation and research on the level of post-traumatic stress disorder and its influencing factors in patients with motor dysfunction after stroke. J PLA Prevent Med. (2020) 38:36–8.

11. Liu, PP, Zhang, SL, Liu, YF, et al. Effects of anxiety, depression and brain lesion characteristics on acute stress disorder in patients with brain injury. Chin J Gerontol. (2019) 39:2794–7.

12. Visser, E, Gosens, T, den Oudsten, BL, and de Vries, J. The course, prediction, and treatment of acute and posttraumatic stress in trauma patients: a systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. (2017) 82:1158–83. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001447

13. Donnellan, C, Hickey, A, Hevey, D, and O’Neill, D. Effect of mood symptoms on recovery one year after stroke. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2010) 25:1288–95. doi: 10.1002/gps.2482

15. Spielberger, CD. Manual for the state trait anxiety inventory form V. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press (1983).

16. Spielberger, CD. Anxiety, cognition an d affect: A state-trait perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (1985).

17. Endler, NS, Parker, JD, Bagby, RM, and Cox, BJ. Multidimensionality of state and trait anxiety: factor structure of the Endler multidimensional anxiety scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1991) 60:919–26. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.6.919

18. Lincoln, NB, Brinkmann, N, Cunningham, S, Dejaeger, E, de Weerdt, W, Jenni, W, et al. Anxiety and depression after stroke: a 5 year follow-up. Disabil Rehabil. (2013) 35:140–5. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.691939

19. Bergersen, H, Frslie, KF, and Schanke, AK. Anxiety, depression, and psychological well-being 2 to 5 years Poststroke-science direct. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2010) 19:364–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.06.005

20. Leppävuori, A, Pohjasvaara, T, Vataja, R, Kaste, M, and Erkinjuntti, T. Generalized anxiety disorders three to four months after ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2003) 16:257–64. doi: 10.1159/000071125

21. Li, W, Xiao, WM, Chen, YK, Qu, JF, Liu, YL, Fang, XW, et al. Anxiety in patients with acute ischemic stroke: risk factors and effects on functional status. Front Psych. (2019) 10:257. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00257

22. Zheng, L, and Liu, Y. Research methods in nursing. Beijing: People’s Health Publishing House (2012). 87 p.

23. Pruss, A, Caspari, G, Krüger, DH, Blümel, J, Nübling, CM, Gürtler, L, et al. Tissue donation and virus safety: more nucleic acid amplification testing is needed. Transpl Infect Dis. (2010) 12:375–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2010.00505.x

24. Jia, FJ, and Cailan, H. Handbook of psychological stress and trauma assessment. United States: People’s Health Publishing House (2009).

25. Li, W-L, and Qian, M-Y. Revision of the state trait anxiety inventory for Chinese college students. J Peking University (Natural Science Edition). (1995) 1:108–12.

26. Burton, CAC, Murray, J, Holmes, J, Astin, F, Greenwood, D, and Knapp, P. Frequency of anxiety after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. (2013) 8:545–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00906.x

28. Gray, JA, and Mcnaughton, N. The neuropsychology of anxiety: an enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press (2000).

29. Knyazev, GG, Savostyanov, AN, and Levin, EA. Uncertainty, anxiety, and brain oscillations. Neurosci Lett. (2005) 387:121–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.016

30. Xiaoxiao, W. Study on the correlation between health promotion behaviors and disease uncertainty in patients with mild stroke. China: Guangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020).

31. Ting, P. Study on the correlation between post-stroke depression and disease uncertainty and psychological resilience in stroke patients. China: Hunan Normal University (2019).

32. Gubay, F, Staunton, R, Metzig, C, Abubakar, I, and White, PJ. Assessing uncertainty in the burden of hepatitis C virus: comparison of estimated disease burden and treatment costs in the UK. J Viral Hepat. (2018) 25:514–23. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12847

33. Gosman-Hedstrom, G, and Dahlin-Ivanoff, S. “Mastering an unpredictable everyday life after stroke”-older women’s experiences of caring and living with their partners. Scand J Caring Sci. (2012) 26:587–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.00975.x

34. Qiu-Ling, W. Study on the correlation between disease uncertainty and self-care ability in patients with ischemic stroke. China: Jilin University (2016).

35. Clayton, MF, Mishel, MH, and Belyea, M. Testing a model of symptoms, communication, uncertainty, and well-being, in older breast cancer survivors. Res Nurs Health. (2010) 29:18–39. doi: 10.1002/nur.20108

36. Sammarco, A. Perceived social support, uncertainty, and quality of life of younger breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. (2001) 24:212–9. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200106000-00007

37. Chunping, P, et al. Uncertainty of acute stroke patients: a cross-sectional descriptive and correlational study. J neurosci nursing: J American Asso Neurosci Nurses. (2018)

38. Kim, SH, Lee, R, and Lee, KS. Symptoms and uncertainty in breast cancer survivors in Korea: differences by treatment trajectory. J Clin Nurs. (2012) 21:1014–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03896.x

39. Wei, WU, Jing, GUO, Xiaoxue, ZHANG, Xinran, WANG, Yang, YANG, and Xinwei, FENG. Analysis of the current occurrence and influencing factors of acute stress disorder in surgical ICU patients after transfer out. China Modern Doctor. (2018) 56:11–13+17.

40. Suliman, S, Troeman, Z, Stein, DJ, and Seedat, S. Predictors of acute stress disorder severity. J Affect Disord. (2013) 149:277–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.041

41. Song, Q, Li, Y, and Chen, C-X. Effects of anxiety and depression on acute stress disorder in patients with traumatic fractures. Modern Prevent Med. (2015) 42:3922–5.

42. Liu, PP. A case-control study of factors influencing acute stress disorder in stroke patients. North China University Sci Technol.

43. Song, Q. A case-control study of acute stress disorder in patients with acute myocardial infarction. North China University Sci Technol.

44. Ozer, EJ, Best, SR, Lipsey, TL, and Weiss, DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. (2003) 129:52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52

45. Yanshu, J. Analysis of factors influencing anxiety in patients with recurrent ischemic stroke. Qilu Nursing J. (2015) 21:2.

46. Xiuqin, C. Study on the relationship between social support and anxiety levels of elderly people in urban communities. J Hebei Energy Vocational Technol College. (2015) 15:25–8.

47. Liu, W. A longitudinal study of psychological resilience and influencing factors in patients with first ischemic stroke. China: Chinese People’s Liberation Army Naval Military Medical University (2018).

48. Xu, P. Correlation analysis of anxiety and depression with personality traits and psychological resilience in stroke patients. China: Jilin University (2020).

49. Lina, Y. Study on factors related to anxiety and depression disorders after acute first cerebral infarction. China: Hebei Medical University (2015).

50. Chen, YW. Study on anxiety and depression symptoms and their influencing factors in neurology stroke inpatients. China: Zhongnan University (2014).

51. Zhang, F. Study on the correlation between life stress, social support and anxiety and depression in patients with cerebrovascular disease. J Qiqihar Medical College. (2019) 40:1390–1.

52. Lee, YL, Gau, BS, Hsu, WM, and Chang, HH. A model linking uncertainty, post-traumatic stress, and health behaviors in childhood Cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. (2009) 36:E20–30. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E20-E30

53. Li-Hui, L, Jun-E, L, and Li-Li, M. Analysis of cancer-related post-traumatic stress disorder and its associated factors. J Nursing Continuing Educ. (2017) 32:1063–6.

54. Chan, CMH, Ng, CG, Taib, NA, Wee, LH, Krupat, E, and Meyer, F. Course and predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder in a cohort of psychologically distressed patients with cancer: a 4-year follow-up study. Cancer. (2018) 124:406–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30980

55. Arnaboldi, P, Riva, S, Crico, C, and Pravettoni, G. A systematic literature review exploring the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and the role played by stress and traumatic stress in breast cancer diagnosis and trajectory. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). (2017) 9:473–85. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S111101

56. Lee, YL. The relationships between uncertainty and posttraumatic stress in survivors of childhood cancer. J Nurs Res. (2006) 14:133–42. doi: 10.1097/01.JNR.0000387571.20856.45

57. Kazak, AE, Alderfer, M, Rourke, MT, Simms, S, Streisand, R, and Grossman, JR. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in families of adolescent childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Psychol. (2004) 29:211–9. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh022

58. Moreland, P, and Santacroce, SJ. Illness uncertainty and posttraumatic stress in young adults with congenital heart disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2018) 33:356–62. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000471

59. Wong, CA, and Bramwell, L. Uncertainty and anxiety after mastectomy for breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. (1992) 15:363–71.

60. Yin Meixiang, L, Yinnan, LY, and Huilian, L. Clinical study of anxiety and related factors in first acute stroke. Chinese Behav Med Sci. (2001) 4:34–5.

Keywords: anxiety, disease uncertainty, acute stress, acute ischaemic stroke, post-epidemic era

Citation: Tan H (2023) The mediating role of anxiety in disease uncertainty and acute stress in acute ischaemic stroke patients in the post-epidemic era. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1218390. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1218390

Edited by:

Yuka Kotozaki, Iwate Medical University, JapanReviewed by:

Alexander Nikolaevich Savostyanov, State Scientific Research Institute of Physiology and Basic Medicine, RussiaDeblina Roy, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Copyright © 2023 Tan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hui Tan, MTAzOTcyMzA2M0BxcS5jb20=

Hui Tan

Hui Tan