- 1Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kansai Medical University, Osaka, Japan

- 2Japanese Society of Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology, Tokyo, Japan

- 3Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics, Tokyo, Japan

- 4Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kyorin University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

- 5Department of Psychiatry, Dokkyo Medical University, Tochigi, Japan

- 6Department of Neuropsychiatry, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

- 7Department of Psychiatry, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Fukuoka, Japan

Objective: In patients with bipolar disorder (BD), rapid cycling (RC) presents a risk for a more severe illness, while euthymia (EUT) has a better prognosis. This study focused on the progression of RC and EUT, which are contrasting phenomenology, and aimed to clarify the influence of patient backgrounds and prescription patterns on these different progressions, using a large sample from the first and second iterations of a multicenter treatment survey for BD in psychiatric clinics (MUSUBI).

Methods: In the cross-sectional study (MUSUBI), a questionnaire based on a retrospective medical record survey of consecutive BD cases (N = 2,650) was distributed. The first survey was conducted in 2016, and the second one in 2017. The questionnaire collected information on patient backgrounds, current episodes, and clinical and prescribing characteristics.

Results: In the first survey, 10.6% of the participants had RC and 3.6% had RC for two consecutive years, which correlated with BP I (Bipolar disorder type I), suicidal ideation, duration of illness, and the use of lithium carbonate and antipsychotic medications. Possible risk factors for switching to RC were comorbid developmental disorders and the prescription of anxiolytics and sleep medication. Moreover, 16.4% of the participants presented EUT in the first survey, and 11.0% presented EUT for two consecutive years. Possible factors for achieving EUT included older age; employment; fewer psychotic symptoms and comorbid personality disorders; fewer antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anxiolytics, and more lithium prescriptions.

Conclusion: RC and EUT generally exhibit conflicting characteristics, and the conflicting social backgrounds and factors contributing to their outcomes were distinctive. Understanding these clinical characteristics may be helpful in clinical practice for management of patients with BD.

1. Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a pervasive, severe, chronic, recurrent, and potentially lethal mental illness that typically manifests as episodes of either manic or depressive polarity, which can last from days to weeks and even months, followed by periods of either remission or the opposite polarity. According to the World Health Organization, this disorder affects approximately 60 million individuals globally, making it the sixth most widespread and rapidly increasing disease worldwide. The lifetime prevalence of the disorder is estimated to be 3% (1, 2); however, the prevalence rates among countries range from 0.2% to 4%. Depressive episodes of BD are often misdiagnosed as depression, with previous reports indicating that 20% of patients diagnosed with depression subsequently received a changed diagnosis of BD. The disorder is also one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, with patients experiencing significant disability for most of their lives, particularly due to depressive symptoms (3–5). Additionally, it has been reported that the rates of suicide and self-harm for this disorder were over 10% and 30–40%, respectively, during their lifetime. While the course of BD varies from person to person, the number of mood episodes has been correlated with various clinical and neurophysiological parameters, such as cognitive function, quality of life, response to pharmacological and socio-psychological treatment, and brain structure (6–8). This is consistent with the paradigm that BD is not only cyclical but also progressive (6, 9). The concept of “Rapid Cycling (RC),” pertaining to four or more mood episodes in a year, was introduced by Dunner and Fieve in the early 1970s as an indication of the course of BD (10). RC is reported to affect 5–30% of patients with bipolar disorder, with a prevalence of approximately 10% reported in a large-scale survey in Japan (11). It has been recognized that patients with RC tend to respond poorly to medication (12), especially lithium (13). More recent research has indicated that these patients may not respond to any treatment and are at a higher risk for poor prognosis, including prolonged treatment, decreased Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores (14, 15), and an increased risk of suicide attempts (12, 14, 16–18). In addition, previous studies have found that patients with RC demonstrate a higher total number of episodes and hospitalizations (19–21), shorter symptom-free periods between episodes (22), more severe disability (15, 23–27), and a higher risk of suicide (23). It has also been suggested that, similar to epilepsy, RC may increase over time (9, 22), and that repeated episodes may shorten the cycle and cause RC, a theory known as the “kindling hypothesis.” In contrast, approximately 20% of patients with BD who recover from mood episodes maintain recovery for approximately 60 weeks (28). Given the importance of distinguishing between RC and long-term asymptomatic BD, which is associated with a good prognosis, and the impact of repeated relapses on the threshold for the occurrence of episodes and the kindling phenomenon, there is a need for large-scale clinical trials examining the epidemiology, background, clinical and social characteristics, and psychotropic drug prescribing patterns of patients with RC and those with long-term asymptomatic BD, as well as changes in these phenotypes over time. The MUlticenter treatment SUrvey on BIpolar disorder in Japanese psychiatric clinics (MUSUBI) is the largest nationwide cross-sectional survey to date on the status of patients with BD in Japan (11, 29–38). In 2020, we identified patients with conflicting phenotypes of current RC and 1-year euthymia (EUT) from the MUSUBI first survey data, and reported differences in patient backgrounds, current episodes, clinical features, and prescribing patterns. However, because it was based on data from a single cross-sectional survey, we were unable to evaluate RC and EUT over time, the clinical features associated with the course of the disease, or its association with medications. In the present study, we focused on the progression of RC and EUT, which are conflicting phenotypes, and aimed to clarify the influence of patient backgrounds and prescription patterns on these different progressions, using the results of a 2-year follow-up study on patients who developed RC and EUT in 2016.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Participants and study design

The Japanese Association of Psychiatry and Neurology Clinics (JAPC) and the Japanese Society of Clinical Neuropharmacology have initiated a joint study called “MUSUBI” to gather evidence on the treatment of BD in Japan. The design and methodology of MUSUBI have been previously described (32, 37). It is a cross-sectional study comprising a questionnaire survey administered to 176 clinics affiliated with the JAPC (11% of all JAPC members). The subjects were patients aged 18–75 years who were diagnosed with BD by their attending physicians according to the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) (World Health Organization) (39) during the study period. The first survey was conducted from September 1 to October 31, 2016, and the second survey was conducted from September 1 to December 31, 2017, with consecutive assessments of the same patients. The attending physician was asked to complete a questionnaire based on a retrospective chart survey of the patients with BD. The questionnaire included questions on patient characteristics, including age, age at onset, sex, height, weight, education, occupation, comorbidities, current conditions, course of illness, duration of current episode, subcategories, the GAF score, suicidal ideation, psychotic symptoms, and medication details. Patients with serious physical illnesses or those deemed unfit to participate by a psychiatrist were excluded. RC was defined as at least four mood episodes that met the criteria for mania, hypomania, or major depression in the previous 12 months. EUT was defined as asymptomatic presentation (no manic symptoms, depression, or suicidal ideation) with no recurrence for at least 12 months. We extracted data on RCs and EUTs for each survey and analyzed their frequencies, transitions, associated patient backgrounds, and prescription patterns. The transitions for RC and EUT were analyzed in four ways (1–1, 1-0, 0-0, 0–1), with 1 indicating presence and 0 as absence, for example, 1–1 RC (RC at the first survey, RC at the second survey) and 1–0 EUT (EUT at the first survey, non-EUT at the second survey), to determine which patient background and prescribed medications were associated with each outcome. The medications included antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, sleep medications, and anxiolytics. Lithium carbonate, valproic acid, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine were included as mood stabilizers in the analysis.

2.2. Statistical analysis

The SPSS® software version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for analysis. Fisher’s exact test or analysis of variance was used for each factor in univariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was then performed for each factor to avoid confounding effects. In this analysis, RC or EUT at the time of the second survey was used as the dependent variable, and sex, age, age at onset, body mass index (BMI), occupational status, GAF score (>60), education (college or higher), suicidal ideation, psychotic symptoms, comorbidity of personality disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders (autism spectrum disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)), alcohol or substance abuse, and physical disability at the time of the first survey were used as candidate independent variables. Factors that showed alpha levels <0.1 in the univariate analysis were included in the model using a stepwise method (F-entry probability: 0.05; removal: 0.1). Adjusted alpha levels <0.004 (0.05/number of candidate independent variables) and < 0.05 were considered significant in univariate analysis and logistic regression analysis, respectively. To understand the characteristics of psychiatric comorbidities associated with RC and EUT, the regression analysis used personality disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, and alcohol and substance abuse comorbidity rates rather than the total psychiatric comorbidity rates. Furthermore, improvements in the GAF score were highly correlated with RC and EUT, and GAF was not included in the logistic regression analysis. The impact of medications on the outcomes was subsequently analyzed using propensity score matching as an exploratory study. Propensity scores were calculated using a logistic regression model with the following factors: sex; age; education; BMI, age at onset; psychiatric comorbidity; comorbidities; psychotic symptoms; suicidal ideation; GAF score; severity of depressive symptoms; severity of manic symptoms, and whether the patient received mood stabilizers, antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, or sleep medications.

2.3. Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Japanese “Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research.” Before the study began, the research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Japan Neuropsychiatric Clinics Association and the Ethics Committee of Kansai Medical University. As this study was a retrospective medical record survey, relevant information was disclosed so that patients could opt out if they so wished. A study-specific subject identification number was assigned to each patient to ensure linkable anonymity in order to protect the patients’ personal information.

3. Results

Questionnaire results were collected from 3,213 patients with BD who completed both the first and second surveys at 176 clinics. We excluded incompatible cases and finally analyzed 3,084 patients overall: 2,539 with EUT and 2,650 with RC (Figures 1A,B). The demographics of RC and EUT, respectively, were as follows: 45.7 and 45.6% (female); mean age, 50.26 ± 13.86 (Standard Deviation: SD) years and 50.32 ± 13.88 (SD) years; mean age of onset, 34.72 ± 12.49 (SD) years and 34.73 ± 12.50 (SD) years; BP I percentage, 35.1%, and 35.3%.

Figure 1. (A) Flow chart of study sample selection of RC. RC; Rapid Cycling, 1RC; RC at the 1st survey, ORC; non-RC at the 1st survey, 1-1RC; RC at the 1st and 2nd survey, 1-ORC; RC at the 1st survey and non-RC at the 2nd, 0-1RC; non-RC at the 1st survey and RC at the 2nd, 0-ORC; non-RC at the 1st and 2nd survey. (B) Flow chart of study sample selection of EUT. EUT; one-year euthymic, OEUT; non-EUT at the 1st survey, 1EUT; EUT at the 1st survey, O-OEUT; non-EUT at the 1st and 2nd survey, 0-1EUT; non-EUT at the 1st survey and EUT at the 2nd, 1–0EUT; EUT at the 1st survey and non-EUT at the 2nd, 1-1EUT; EUT at the 1st and 2nd survey.

3.1. Rapid cycling

RCs were observed in 10.6% (281/2,650) of patients in the first survey, whereas 3.6% (95/2,650) presented RC for two consecutive years. Out of those with RC in the first survey, 33.8% (95/281) continued presenting in the following year. Additionally, 53.1% (95/179) of those with RC in the second survey had also presented RC in the previous year. Of the non-RC-presenting individuals in the first survey, 3.5% (84/2,369) showed RC and 86.2% (2,285/2,369) never presented RC within the following 2 years. Patients who presented RC in the first survey significantly maintained the presentation in the following year (odds ratio (OR) [95% confidence interval (CI)] = 13.9 [10.0–19.3], p < 0.0001).

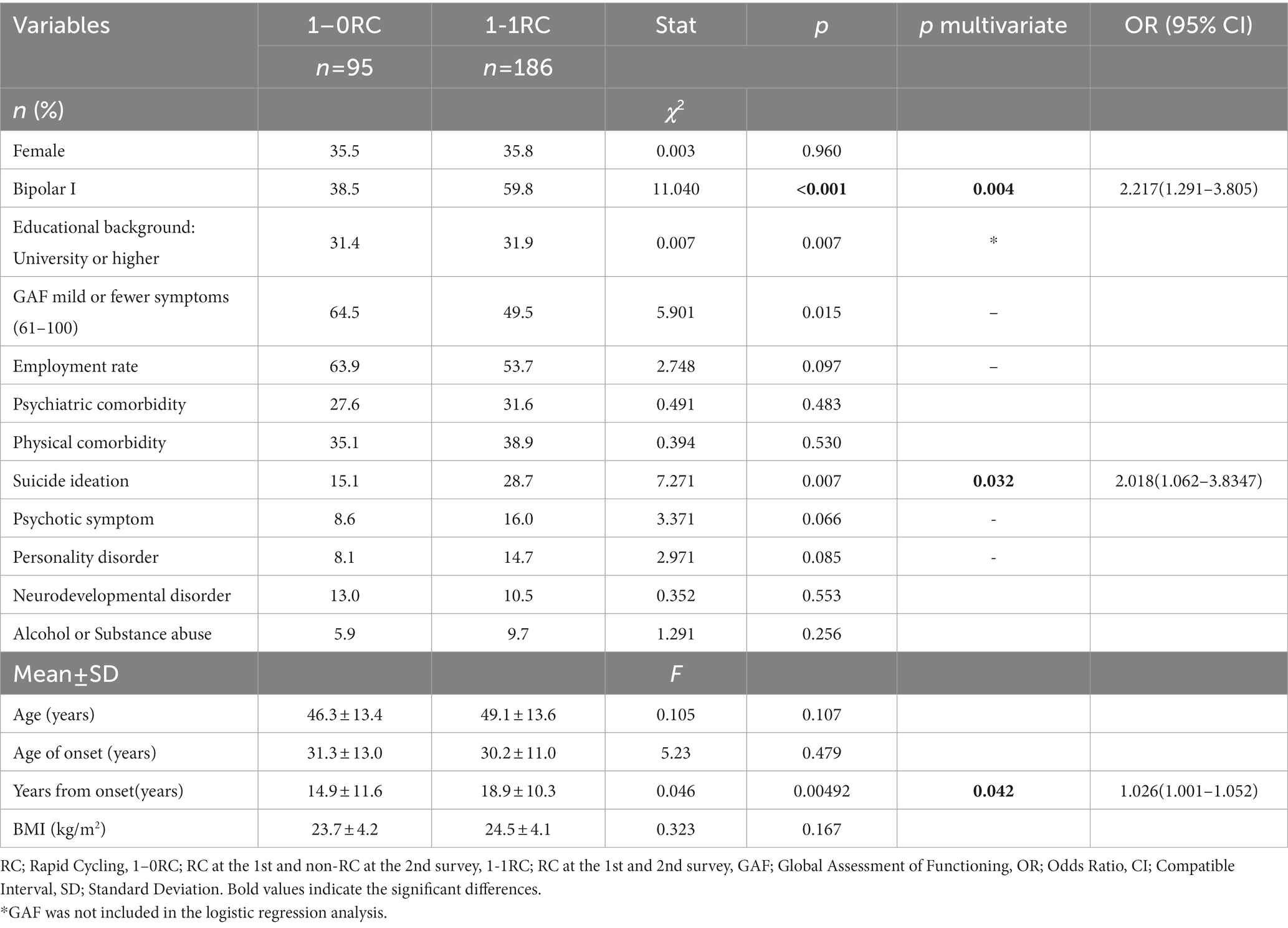

3.1.1. Outcome of patients with RC in the first survey

The outcomes of patients who presented RC in the first survey were examined in the second (Table 1). Univariate analysis showed significant differences in the BP subtype (p < 0.001). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that 1–1 RC had higher BP I (OR [95% CI] = 2.217 [1.091–3.805], p = 0.004) and suicidal ideation (OR = 2.018 [1.062–3.8347], p = 0.032) and longer disease duration (OR = 1.026 [1.001–1.052], p = 0.042) than 1–0 RC.

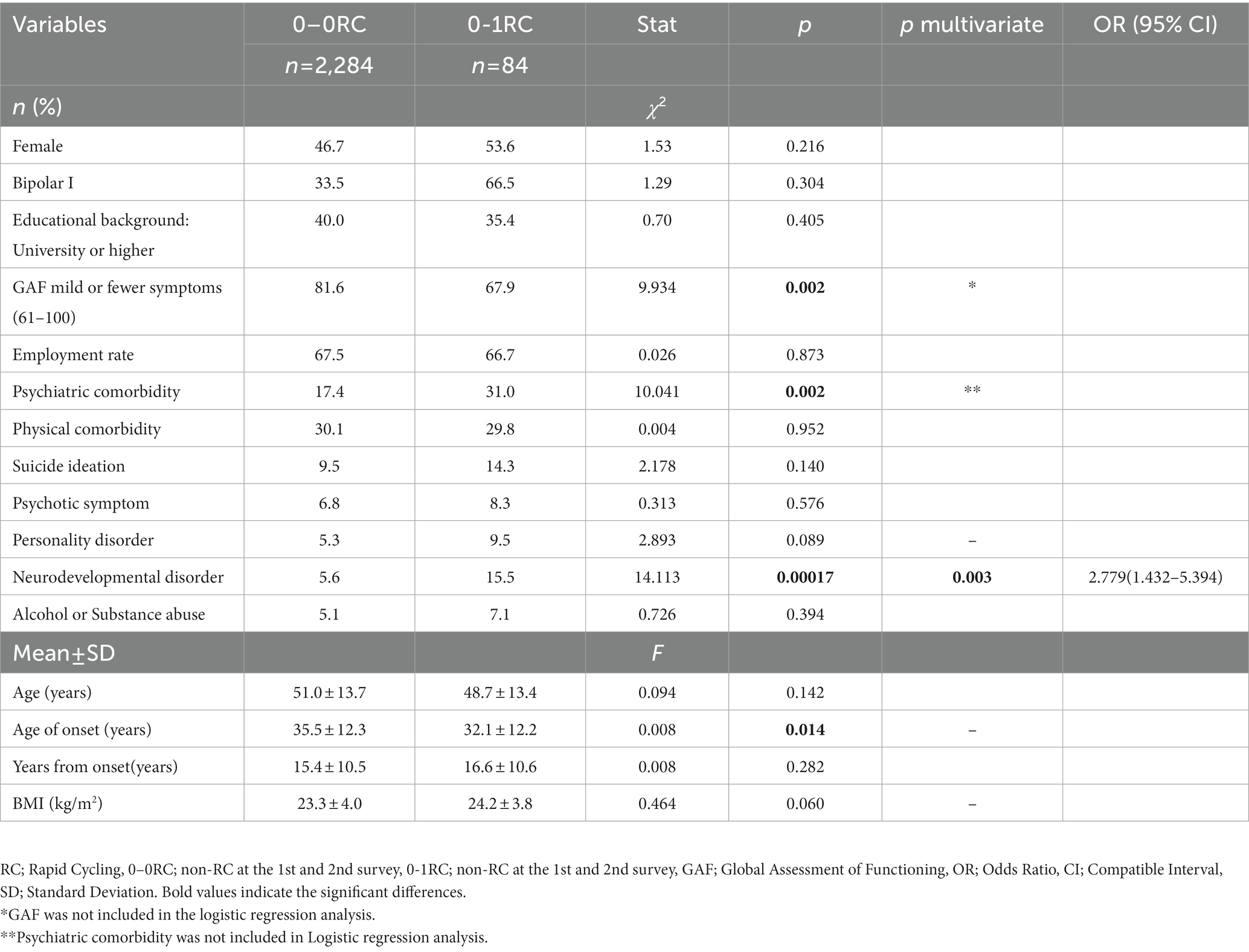

3.1.2. Outcome of patients without RC in the first survey

Univariate analysis showed that 0–1 RC had significantly higher GAF scores (p = 0.002) and higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity (p = 0.002) than 0–0 RC. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that 0–1 RC presented more neurodevelopmental disorders than 0–0 RC (OR = 2.779 [1.432–5.394], p = 0.003; Table 2).

3.2. Outcome of patients with EUT

EUT was observed in 16.4% (416/2,539) of patients in the first survey, and 11.0% (279/2,539) presented EUT for two consecutive years. Of those with EUT in the first survey, 67.1% (279/416) continued presenting in the following year. Of the patients with EUT in the second survey, 50.5% (279/552) also presented in the previous year. A total of 12.9% (273/2,123) of the participants who did not present EUT in the first survey had EUT in the following year, and 72.9% (1,850/2,539) had never experienced EUT in the 2 years. Patients who had EUT at the first survey were significantly more likely to have EUT 1 year later (OR = 13.8 [10.8–17.6], p < 0.0001).

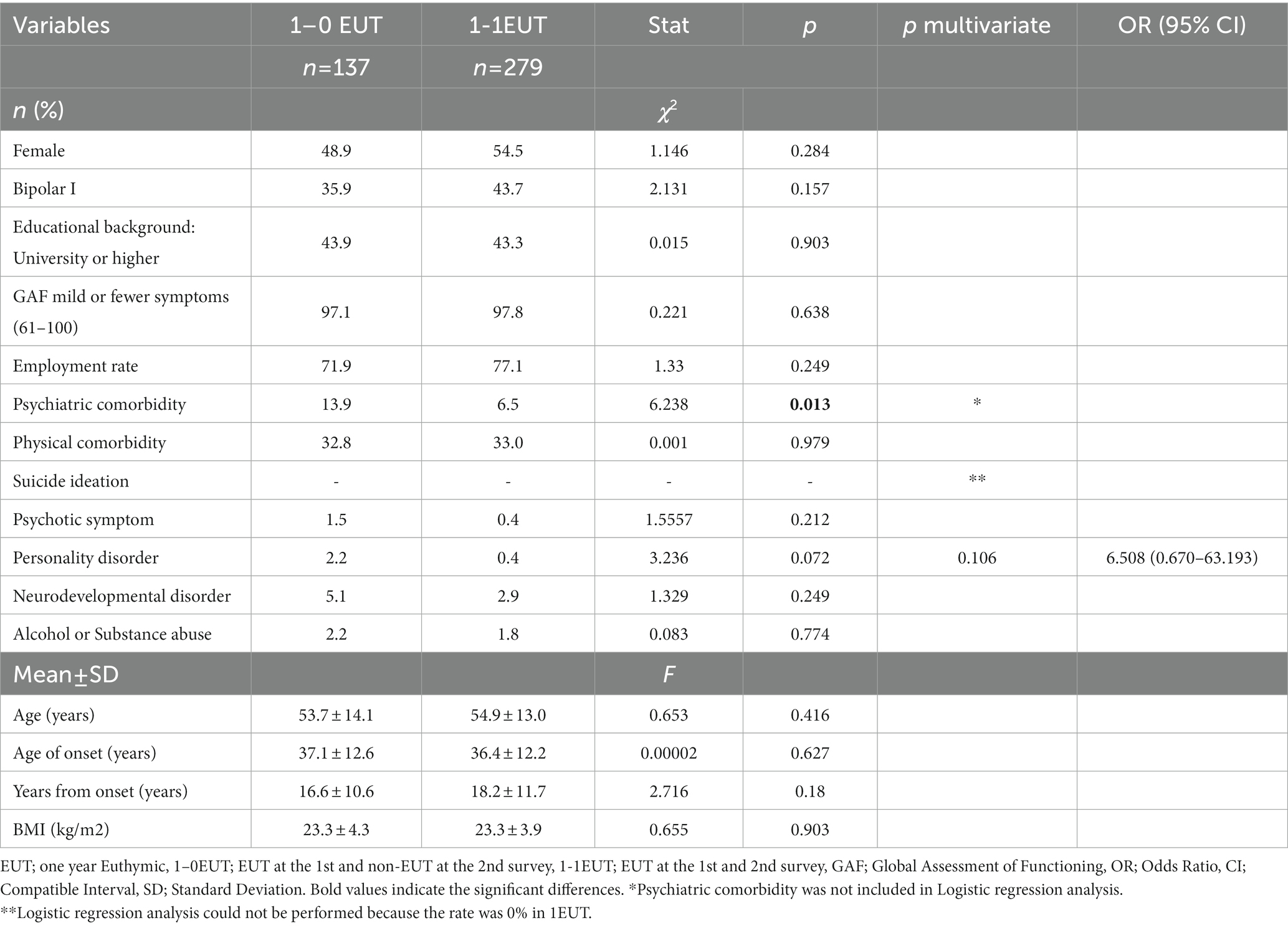

3.2.1. Outcome of patients with EUT in the first survey

No significant differences were found between 1 and 0 EUT and 1–1 EUT in either the univariate or multivariate analyses (Table 3).

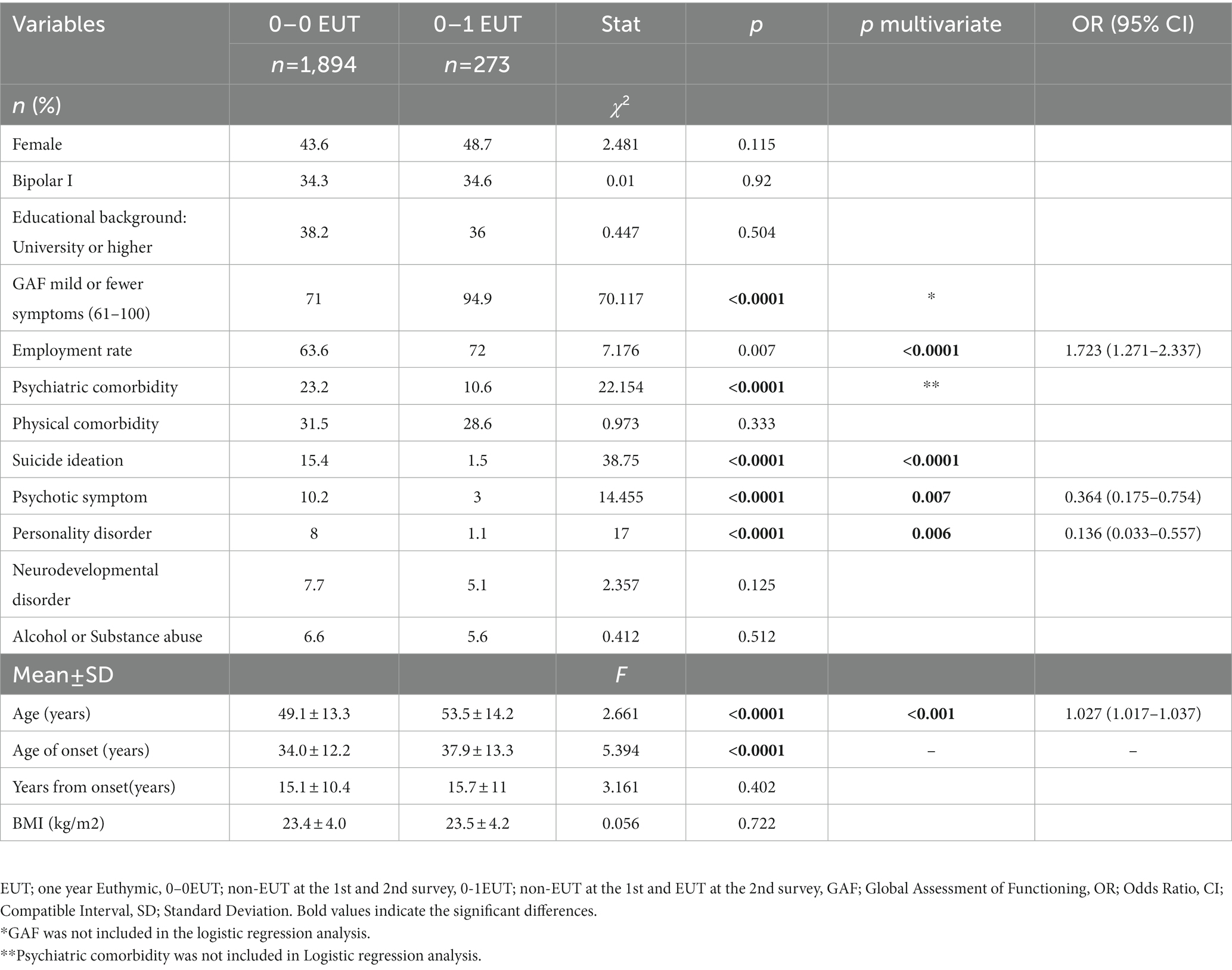

3.2.2. Outcome of patients without EUT in the first survey

Univariate analysis showed that 0–0 EUT had significantly higher GAF scores (p < 0.0001); higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity (p < 0.0001), suicidal ideation (p < 0.0001), psychotic symptoms (p < 0.0001); higher rates of a coexisting personality disorder (p < 0.0001); younger age (p < 0.0001); lower age at onset (p < 0.0001) than 0–1 EUT. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that 0–0 EUT was younger (OR = 1.027 [1.017–1.037], p < 0.001) and had lower employment rates (OR = 1.723 [1.2071–2.337], p < 0.001), more psychotic symptoms (OR = 0.364 [0.175–0.754], p = 0.007), and more personality disorders (OR = 0.136 [0.033–0.557], p = 0.006; Table 4).

3.3. Examination of the effect of drugs on each outcome

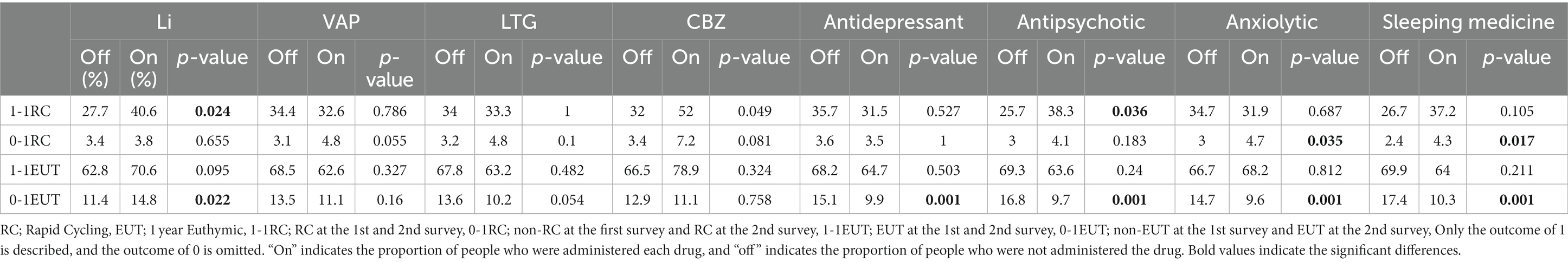

The effect of drugs on outcomes was analyzed using propensity score matching (Table 5).

3.3.1. Outcomes by prescription for patients with RC in the first survey

In the relationship between medications and the 1-year outcome for RC at the time of the first survey (n = 281), 1–1 RC received more lithium (p = 0.024) and antipsychotics (p = 0.036) than 1–0 RC. No predominant correlation was found with other medications, including antidepressants.

3.3.2. Outcomes by prescription for patients without RC in the first survey

Regarding the relationship between medications and the 1-year outcome for non-RC at the time of the first survey (n = 2,369), 0–1 RC received more anxiolytics (p = 0.035) and sleeping medications (p = 0.017) than 0–0 RC. In the current study, antidepressants did not affect RC outcomes.

3.3.3. Outcomes by prescription for patients with EUT in the first survey

There was no significant correlation between any of the drugs and the 1-year outcome for the patients with EUT at the time of the first survey (n = 416).

3.3.4. Outcomes by prescription for patients without EUT in the first survey

In the relationship between medications and the 1-year outcome for non-EUT at the time of the first survey (n = 2,123), significantly more lithium was administered to 0–1 EUT than to 0–0 EUT (p = 0.022), whereas antidepressants (p = 0.001), antipsychotics (p = 0.001), anxiolytics (p = 0.001), and sleep medications (p = 0.001) were administered less frequently. No significant differences were observed between valproic acid, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine administrations.

4. Discussion

In this study, we analyzed a 2-year dataset from a large sample of patients with BD (n = 3,084) in an outpatient psychiatric clinic to examine the outcomes of RC with frequent mood episodes and EUT without mood episodes in relation to demographics, clinical characteristics, and prescribed medications. Our findings indicated that 9.7% of all patients had RC in the first year, and 4% experienced RC in both the first and second years. In the subgroup that had RC in the first year, 33.8% continued to experience RC in the second year, a rate significantly higher than the 3.5% observed in the group that did not experience RC in the first year. However, more than 60% of patients who experienced RC in the first year did not experience RC in the following year. In the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), 32% of the 1,742 participants enrolled in the study experienced RC at the outset. However, a post-study survey conducted on 68% of the participants who were able to continue the study showed a significant reduction in RC incidence by 5% (23). It must be recognized that those experiencing RC might have quit the study. In our study, 2,650 (86%) of the 3,069 participants analyzed in the first survey were followed up with adequate data in the second survey. Of these, our study was able to follow-up with 80% (n = 263) of the 329 subjects who experienced RC in the first year through a second survey, potentially providing a more accurate depiction of their condition. Coryell et al. also reported that the percentage of RCs was approximately 19% in the first year, and then decreased to 5% between 2 and 5 years (12). Another study followed patients for 15 years and observed that four out of five cases of RC ended within 2 years of onset. These results support the idea that RC is a temporary state in the course of BD, and our study confirms this. Their study also noted that patients with RC were more likely to have onset before the age of 17 years and make serious suicide attempts. Our study similarly showed that RC had a lower age of onset and significantly more suicidal ideation (11). In terms of outcome, low age at onset is a factor that predisposes to 0–1 RC, and a long disease duration is a factor that correlates to a patient with RC continuing the presentation in the following year. The results support the idea of the earlier age of onset as a risk factor for RC and, at the same time, support the kindling hypothesis. This suggests that RC is a transient condition, but the risk of occurrence is based on the kindling hypothesis.

Numerous studies have investigated the potential of antidepressants to promote mood episodes ranging from depression to mania. In STEP-BD, antidepressants were associated with more frequent episodes; however, Coryell et al. reported that antidepressants, including tricyclics, did not contribute to switching (12). A systematic review of RC (40) did not provide clear evidence supporting that antidepressants promote manic episodes (41). In the current study, as in the systematic review, antidepressants were found to not contribute to RC outcomes. To date, the well-known risks associated with RC have been female sex and bipolar II disorder (23), but these predictors are of limited clinical utility because of their modest relationship with the frequency of mood episodes (9). Indeed, in the present study, there was no significant correlation with sex, and bipolar I disorder was found to be a risk factor. It is interesting to note that bipolar I disorder has not yet been reported as a risk factor for RC and maybe a unique feature of this disorder in Japan. Alternatively, only patients with confirmed BD were enrolled in the study; this might have reduced the enrollment of patients with bipolar II disorder, which is difficult to diagnose (14, 42–45). The GAF score was significantly lower in the 0–1 RC group than in the 0–0 RC group, which may reflect lower cognitive function and quality of life due to RC, as well as higher levels of suicidal ideation (15, 18, 23–27, 42).

A significant positive correlation between psychiatric comorbidities, especially developmental disorder comorbidities, and RC was found in the present study. Developmental disorders comprise a unique group of neurodevelopmental disorders that may affect up to 2.6% of the general population. Most patients with developmental disorders have at least one comorbid psychiatric disorder. Previous reports have also estimated the prevalence of BD in patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to be 5–8%, and a study of the largest group yet in this context found that 9,062 of 700,000 children met the diagnostic criteria for ASD at the age of 16 years, with BD being six times more common in patients with ASD patients than in those without (46). In addition, a recent meta-analysis found that approximately one in 13 adults with ADHD was diagnosed with BD, and almost one in six adults with BD had ADHD (47), indicating a high comorbidity of both disorders. They also reported that patients with developmental disorders, including ADHD, developed BD at a younger age and experienced more frequent manic episodes. This may facilitate kindling and lead to more acute cycling. Although no correlation between ADHD and RC has been reported, it may be necessary to be aware of the risk of developing RC in patients with developmental disorders, especially BD with concomitant ADHD. In addition, the possibility that the diagnoses of developmental disorders and BD overlap and that the diagnoses may be artificially duplicated was investigated and ruled out (48).

In our study, RC occurrence in the previous year was a strong risk factor for RC in the following year. This has been reported in previous studies as well, with Schneck (23) reporting a history of RC as the strongest predictor of RC, and Bauer (49) reporting that patients with RC had significantly more episodes than those without in a prospective follow-up study over 12 months. These data suggest that patients who recently experienced RC are more likely to experience similar cycling in the future and require careful observation.

Significant correlates of outcomes from 0 EUT to 1 EUT were higher GAF, higher employment rate, older age, fewer psychotic symptoms, and fewer comorbid personality disorders. In the STEP-BD group, no correlations were found for age, age at onset, duration of illness, education, marital status, income, or substance use disorder. Among the factors found in this study, it was difficult to determine a causal relationship between employment rates, psychotic symptoms, and relapse rates. Meanwhile, older age and fewer comorbid personality disorders could be predictors of relapse, as these are inherent patient characteristics. Analysis of medications suggested that for patients with RC in the first-year, lithium carbonate, and antipsychotics may be risk factors for the continued presentation of RC in the following year. For subjects without RC in the first year, the prescription of anxiolytics and hypnotics may be a risk factor for RC in the following year. However, there was no correlation with antidepressants.

The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with BD state that antidepressants are not recommended for patients with RC because they have been shown to destabilize patients even when mood stabilizers are administered (50). Previous reports on antidepressant use have shown an association between RC and antidepressants in short-term retrospective studies (51–53), but long-term studies have been inconclusive (54–57). It is also noted that lithium carbonate, divalproex, and antipsychotics (olanzapine and quetiapine) are equally effective in helping patients with RC (58), while lamotrigine was not different from placebo in the maintenance treatment of patients with BD type I (59). Major studies and guidelines do not mention the effects of anxiolytics and sleeping pills in patients with BD. In this study, anxiolytics and hypnotics were negatively correlated with RC, raising the possibility that they may potentially worsen the symptoms of BD, although it is difficult to establish causality. RC has been proposed as a probable result of the ineffectiveness of lithium carbonate, and this study shows that the usage of lithium carbonate may be a risk factor for RC in the following year in patients who presently have RC. Although this is a cross-sectional observational study that cannot prove causality, this finding may be interpreted as a result of lithium carbonate and antipsychotic administration to difficult-to-treat patients who presented with RC.

In terms of EUT outcomes, lithium was associated with the following year’s EUT for patients without EUT who had some symptoms in the first year, suggesting that lithium administration may lead to symptom stabilization. In contrast, antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, and sleeping pills were negatively correlated, indicating that the usage of these drugs may be a risk factor for relapse in the following year. Interestingly, the use of antidepressants, which have been discussed as a risk factor for relapse, showed no correlation with the risk of relapse. According to CANMAT guidelines, lithium carbonate is the first-line drug for all conditions of bipolar I disorder and maintenance therapy for bipolar II disorder, which is consistent with the present results. Several second-generation antipsychotics are first-line agents for maintenance therapy. This study suggests that antipsychotics used with the aim of euthymia may have been ineffective. As for antidepressants, the results were partially consistent with the STEP-BD results, showing that antidepressants were correlated with the number of episodes. Antidepressant treatment correlated with the outcome of relapse but not with the outcome of RC. This suggests that as the sample size of patients with RC increases, the association between antidepressant medications and the risk of RC may become more evident.

The strengths of this study include its use of data from a large sample of patients with BD over 2 years, diagnoses made by psychiatrists practicing in clinics using appropriate ICD-10 criteria, evaluation of EUT without a 1-year mood episode, which has rarely been reported as a good prognostic indicator, and use of propensity scores to minimize bias and evaluate the effect of medications on RC and EUT outcomes. It is important to mention that this was a cross-sectional study based on a questionnaire and had several limitations. First, it is difficult to identify causal relationships between factors and their respective consequences. However, certain factors present before the onset of BD, such as sex, age at onset, developmental disability, and personality disorder, may be predictive of illness trajectories. Second, it is also possible that the missing information on clinical variables influenced the results, although we tried to identify factors that were thoroughly discussed in our study group and considered clinically important and to include them in the questionnaire as much as possible. Third, this study was based on chart review rather than the use of a mood rating scale, which might have potentially affected the accuracy of symptom severity assessment. Nevertheless, attending physicians carefully reviewed the medical records including GAF scores to mitigate this possibility. Fourth, many participants received psychosocial interventions. While there are reports that the effectiveness of psychosocial therapy for patients with BD has not been established (60, 61), it has been shown to speed recovery from episodes, delay relapse, reduce residual mood symptoms, and improve psychosocial functioning when used in conjunction with pharmacotherapy (62). Information on these interventions is missing from the current study, and there may be a therapeutic bias for each patient. Fifth, in propensity score matching, SMD < 0.25 was used for balance adjustment, but some items did not meet this requirement. It is possible that the number of patients in this study was insufficient for subgroups to analyze the effect of each drug on each outcome. Future studies with larger numbers of patients are needed to confirm this finding. Finally, this study was evaluated by physicians working in 176 clinics, and an inter-rater bias might have been present. However, the majority of participating psychiatrists were certified by the Japanese Society of Neuropsychiatry and by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare as designated psychiatrists, indicating a level of expertise in psychiatric care. Therefore, it is expected that the bias in ratings between the attending physicians was relatively small.

In summary, 10.6% of patients with BDs were found to have RC in the first survey, with 3.6% experiencing RC for two consecutive years, which correlated with BP I, suicidal ideation, prolonged disease duration, increased use of lithium carbonate, and antipsychotics compared to those who experienced RC for the first year but not the second. Possible risk factors for switching to RC include comorbid developmental disabilities and the prescription of anxiolytics and sleep medications. Additionally, 16.4% of patients with BD experienced EUT in the first survey, and 11.0% experienced this state for two consecutive years. Notably, no significant correlation was observed in the patient background or medication usage between those who were asymptomatic for 1 year and those who were asymptomatic for two consecutive years. However, possible factors that might have contributed to achieving EUT included older age; a higher employment rate; fewer psychotic symptoms; fewer personality disorders; increased use of lithium carbonate, and fewer antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, and sleeping pills compared to those who were symptomatic for two consecutive years. When comparing the first survey with 1 year of data (11) to the current two-year outcome data, it is noteworthy that the former identified conflicting factors for EUT and RC including the age of onset and developmental and personality disorders, whereas the current results revealed no shared factors affecting either phenotype concerning the outcome. Therefore, further long-term prospective studies are necessary to identify risk factors and predictors of outcomes for these conflicting conditions. The MUSUBI study is ongoing and will provide further insights into the background and course of BD.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Japanese “Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research.” Before the study began, the research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Japan Neuropsychiatric Clinics Association and the Ethics Committee of Kansai Medical University. As this study was a retrospective medical record survey, relevant information was disclosed so that patients could opt out if they so wished. A study-specific subject identification number was assigned to each patient to ensure linkable anonymity in order to protect the patients’ personal information.

Author contributions

CT: investigation, statistical analysis, writing & editing, and visualization. MK: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, statistical analysis, writing—review & editing, visualization, and supervision. NA: resources, data curation, and sample recruitment. YK: resources, data curation, and sample recruitment. TA: resources, data curation, and sample recruitment. HU: resources, data curation, and sample recruitment. KE: resources, data curation, and sample recruitment. EK: resources, data curation, and sample recruitment. EG: resources, data curation, and sample recruitment. SH: resources, data curation, and sample recruitment. TT: investigation, methodology, and writing—review & editing. NY-F: investigation, methodology, and review & editing. AN: investigation, methodology, and review & editing. TKik: investigation, methodology, and review & editing. TKin: investigation and review & editing. KM: resources, data curation, and sample recruitment. KW: investigation, methodology, review & editing, and project administration. RY: investigation, methodology, and review & editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by a Ken Tanaka memorial research grant (grant numbers: 2016-2, 2017-4, and 2019-3). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following psychiatrists from the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics: KM, Toshihiko Lee, Norio Okamoto, Makoto Nakamura, Junkou Sato, Kazunori Otaka, Satoshi Terada, Tadashi Ito, Munehide Tani, Atsushi Satomura, Hiroshi Sato, Hideki Nakano, Yoichi Nakaniwa, Eiichi Hirayama, Keiichi Kobatake, Koji Tanaka, Mariko Watanabe, Shiguyuki Uehata, Asana Yuki, Nobuko Akagaki, Michie Sakano, Akira Matsukubo, Yukihisa Kibota, Yasuyuki Inada, Hiroshi Oyu, Tsuneo Tsubaki, Tatsuji Tamura, Shigeki Akiu, Atsuhiro Kikuchi, Keiji Sato, Kazuyuki Fujita, Fumio Handa, Hiroyuki Karasawa, Kazuhiro Nakano, Kazuhiro Omori, Seiji Tagawa, Daisuke Maruno, Hiroaki Furui, You Suzuki, Takeshi Fujita, Yukimitsu Hoshino, Kikuko Ota, Takaharu Azekawa, Akira Itami, Kenichi Goto, Yoshiaki Yamano, Kiichiro Koshimune, Junko Matsushita, Takatsugu Nakayama, Kazuyoshi Takamuki, Nobumichi Sakamoto, Eiichi Katsumoto, Miho Shimizu, Muneo Shimura, Norio Kawase, Ryouhei Takeda, Takuya Hirota, Hideko Fujii, Yoichiro Watanabe, Riichiro Narabayashi, Yutaka Fujiwara, Kazu Kobayashi, Yuko Urabe, Miyako Oguru, Osamu Miura, Yoshio Ikeda, Hitoshi Ueda, Hidemi Sakamoto, Yosuke Yonezawa, Yoichi Takei, Toshimasa Sakane, Kiyoshi Oka, Kyoko Tsuda, Shigemitsu Hayashi, Kunihiko Kawamura, Yasushi Furuta, Kazuko Miyauchi, Yoshio Miyauchi, Mikako Oyama, Keizo Hara, Misako Sakamoto, Shigeki Masumoto, Yasuhiro Kaneda, Yoshiko Kanbe, Masayuki Iwai, Naohisa Waseda, Nobuhiko Ota, Takahiro Hiroe, Ippei Ishii, Hideki Koyama, Terunobu Otani, Osamu Takatsu, Takashi Ito, Norihiro Marui, Toru Takahashi, Tetsuro Oomori, Toshihiko Fukuchi, Kazumichi Egashira, Kiyoshi Kaminishi, Ryuichi Iwata, Satoshi Kawaguchi, Yoshinori Morimoto, Hirohisa Endo, Yasuo Imai, Eri Kohno, Aki Yamamoto, Naomi Hasegawa, Sadamu Toki, Hideyo Yamada, Hiroyuki Taguchi, Hiroshi Yamaguchi, Hiroki Ishikawa, Sakura Abe, Kazuhiro Uenoyama, Kazunori Koike, Yoshiko Kamekawa, Michihito Matsushima, Ken Ueki, Sintaro Watanabe, Tomohide Igata, Yoshiaki Higashitani, Eiichi Kitamura, Junko Sanada, Takanobu Sasaki, Kazuko Eto, Ichiro Nasu, Kenichiro Sinkawa, Yukio Oga, Michio Tabuchi, Daisuke Tsujimura, Tokunai Kataoka, Kyohei Noda, Nobuhiko Imato, Ikuko Nitta, Yoshihiro Maruta, Satoshi Seura, Toru Okumura, Osamu Kino, Tomoko Ito, Ryuichi Iwata, Wataru Konno, Toshio Nakahara, Masao Nakahara, Hiroshi Yamamura, Masatoshi Teraoka, Eiichiro Goto, Masato Nishio, Koji Edagawa, Miwa Mochizuki, Tsuneo Saitoh, Tetsuharu Kikuchi, Chika Higa, Hiroshi Sasa, Yuichi Inoue, Muneyoshi Yamada, Yoko Fujioka, Kuniaki Maekubo, Hiroaki Jitsuiki, Toshihito Tsutsumi, Yasumasa Asanobu, Seiji Inomata, Kazuhiro Kodama, Aikihiro Takai, Asako Sanae, Shinichiro Sakurai, Kazuhide Tanaka, Masahiko Shido, Haruhisa Ono, Wataru Miura, Yukari Horie, Tetso Tashiro, Tomohide Mizuno, Naohiro Fujikawa, Hiroshi Terada, Kenji Taki, Kyoko Kyotani, Masataka Hatakoshi, Katsumi Ikeshita, Keiji Kaneta, Ritsu Shikiba, Tsuyoshi Iijima, Masaru Yoshimura, Naoto Adachi, Masumi Ito, Shunsuke Murata, Seiji Hongo, Mio Mori, and Toshio Yokouchi. The authors also thank Takayuki Abe for their helpful comments on statistical analysis.

Conflict of interest

MK has received grant funding from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation, the Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology, and the Japanese Society of Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology and speaker’s honoraria from Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Otsuka, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Eli Lilly, MSD K.K., Pfizer, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck, and Ono Pharmaceutical, and participated in an advisory/review board for Otsuka, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Shionogi, and Boehringer Ingelheim. YK has received consultant fees from Pfizer and Meiji-Seika Pharma and speaker’s honoraria from Meiji-Seika Pharma, MSD, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck Japan, and Eisai. TA has received speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma and Eisai. HU has received manuscript fees or speaker’s honoraria from Eisai Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin. KE has received speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Kyowa, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. EK has received speaker’s honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, UCB, and Viatris. SH has received manuscript fees or speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin. EG has received manuscript fees or speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Eisai, Ono Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical Industry, and Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma. RY has received speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Dainippon Sumitomo, Otsuka, and Esai. AN has received speaker’s honoraria from Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Otsuka, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mochida, Dainippon Sumitomo, and NTT Docomo, and participated in an advisory board for Takeda, Meiji Seika, Tsumura, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin. TKik has received consultant fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical and the Center for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Training. TT has received consultant fees from Pfizer and speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Meiji-Seika Pharma, MSD, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. KW has received manuscript fees or speaker’s honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, has received research/grant support from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, MSD, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and is a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck Japan, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Viatris. NY-F has received grant/research support or honoraria from, and received speaker’s honoraria of Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, MSD, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Schmitt, A, Malchow, B, Hasan, A, and Falkai, P. The impact of environmental factors in severe psychiatric disorders. Front Neurosci. (2014) 8:19. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00019

2. Boland, EM, and Alloy, LB. Sleep disturbance and cognitive deficits in bipolar disorder: toward an integrated examination of disorder maintenance and functional impairment. Clin Psychol Rev. (2013) 33:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.001

3. Judd, LL, Akiskal, HS, Schettler, PJ, Coryell, W, Endicott, J, Maser, JD, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2003) 60:261–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.261

4. Judd, LL, Akiskal, HS, Schettler, PJ, Endicott, J, Maser, J, Solomon, DA, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2002) 59:530–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530

5. Van Rheenen, TE, and Rossell, SL. Phenomenological predictors of psychosocial function in bipolar disorder: is there evidence that social cognitive and emotion regulation abnormalities contribute? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2014) 48:26–35. doi: 10.1177/0004867413508452

6. Kessing, LV, Andersen, PK, and Vinberg, M. Risk of recurrence after a single manic or mixed episode - a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Bipolar Disord. (2018) 20:9–17. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12593

7. Burdick, KE, Russo, M, Frangou, S, Mahon, K, Braga, RJ, Shanahan, M, et al. Empirical evidence for discrete neurocognitive subgroups in bipolar disorder: clinical implications. Psychol Med. (2014) 44:3083–96. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000439

8. Strakowski, SM, DelBello, MP, Zimmerman, ME, Getz, GE, Mills, NP, Ret, J, et al. Ventricular and periventricular structural volumes in first- versus multiple-episode bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2002) 159:1841–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1841

9. Kupka, RW, Luckenbaugh, DA, Post, RM, Leverich, GS, and Nolen, WA. Rapid and non-rapid cycling bipolar disorder: a Meta-analysis of clinical studies. J Clin Psychiatry. (2003) 64:1483–94. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1213

10. Dunner, DL, and Fieve, RR. Clinical factors in Lithium carbonate prophylaxis failure. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1974) 30:229–33. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760080077013

11. Kato, M, Adachi, N, Kubota, Y, Azekawa, T, Ueda, H, Edagawa, K, et al. Clinical features related to rapid cycling and one-year Euthymia in bipolar disorder patients: a multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric clinics (MUSUBI). J Psychiatr Res. (2020) 131:228–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.030

12. Coryell, W, Solomon, D, Turvey, C, Keller, M, Leon, AC, Endicott, J, et al. The long-term course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2003) 60:914–20. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.914

13. Dunner, DL, Patrick, V, and Fieve, RR. Rapid cycling manic depressive patients. Compr Psychiatry. (1977) 18:561–6. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90006-7

14. Cruz, N, Vieta, E, Comes, M, Haro, JM, Reed, C, Bertsch, J, et al. Rapid-cycling bipolar I disorder: course and treatment outcome of a large sample across Europe. J Psychiatr Res. (2008) 42:1068–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.12.004

15. Schneck, CD, Miklowitz, DJ, Calabrese, JR, Allen, MH, Thomas, MR, Wisniewski, SR, et al. Phenomenology of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: data from the first 500 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program. Am J Psychiatry. (2004) 161:1902–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1902

16. Vieta, E, Calabrese, JR, Hennen, J, Colom, F, Martínez-Arán, A, Sánchez-Moreno, J, et al. Comparison of rapid-cycling and non–rapid-cycling bipolar I manic patients during treatment with olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry. (2004) 65:1420–8. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1019

17. Garcia-Amador, M, Colom, F, Valenti, M, Horga, G, and Vieta, E. Suicide risk in rapid cycling bipolar patients. J Affect Disord. (2009) 117:74–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.12.005

18. Undurraga, J, Baldessarini, RJ, Valenti, M, Pacchiarotti, I, and Vieta, E. Suicidal risk factors in bipolar I and ii disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry. (2012) 73:778–82. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07041

19. Coryell, W. Rapid cycling bipolar disorder: clinical characteristics and treatment options. CNS Drugs. (2005) 19:557–69. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519070-00001

20. Dunner, DL. Bipolar disorders in Dsm-iv: impact of inclusion of rapid cycling as a course modifier. Neuropsychopharmacology. (1998) 19:189–93. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00024-4

21. Kupka, RW, Luckenbaugh, DA, Post, RM, Suppes, T, Altshuler, LL, Keck, PE Jr, et al. Comparison of rapid-cycling and non-rapid-cycling bipolar disorder based on prospective mood ratings in 539 outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. (2005) 162:1273–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1273

22. Azorin, JM, Kaladjian, A, Adida, M, Hantouche, EG, Hameg, A, Lancrenon, S, et al. Factors associated with rapid cycling in bipolar I manic patients: findings from a French National Study. CNS Spectr. (2008) 13:780–7. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900013900

23. Schneck, CD, Miklowitz, DJ, Miyahara, S, Araga, M, Wisniewski, S, Gyulai, L, et al. The prospective course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: findings from the Step-Bd. Am J Psychiatry. (2008) 165:370–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05081484

24. Lee, S, Tsang, A, Kessler, RC, Jin, R, Sampson, N, Andrade, L, et al. Rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: cross-National Community Study. Br J Psychiatry. (2010) 196:217–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067843

25. Wells, JE, McGee, MA, Scott, KM, and Oakley Browne, MA. Bipolar disorder with frequent mood episodes in the New Zealand mental health survey. J Affect Disord. (2010) 126:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.136

26. Hajek, T, Slaney, C, Garnham, J, Ruzickova, M, Passmore, M, and Alda, M. Clinical correlates of current level of functioning in primary care-treated bipolar patients. Bipolar Disord. (2005) 7:286–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00182.x

27. Fountoulakis, KN, Vieta, E, and Schmidt, F. Aripiprazole monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar disorder: a Meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2011) 133:361–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.018

28. Perlis, RH, Ostacher, MJ, Patel, JK, Marangell, LB, Zhang, H, Wisniewski, SR, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (Step-Bd). Am J Psychiatry. (2006) 163:217–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.217

29. Adachi, N, Azekawa, T, Edagawa, K, Goto, E, Hongo, S, Kato, M, et al. Estimated model of psychotropic polypharmacy for bipolar disorder: analysis using Patients' and Practitioners' parameters in the MUSUBI study. Hum Psychopharmacol. (2021) 36:e2764. doi: 10.1002/hup.2764

30. Ikenouchi, A, Konno, Y, Fujino, Y, Adachi, N, Kubota, Y, Azekawa, T, et al. Relationship between employment status and unstable periods in outpatients with bipolar disorder: a multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric outpatient clinics (MUSUBI) study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2022) 18:801–9. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S353460

31. Kawamata, Y, Yasui-Furukori, N, Adachi, N, Ueda, H, Hongo, S, Azekawa, T, et al. Effect of age and sex on prescriptions for outpatients with bipolar disorder in the MUSUBI study: a cross-sectional study. Ann General Psychiatry. (2022) 21:37. doi: 10.1186/s12991-022-00415-0

32. Konno, Y, Fujino, Y, Ikenouchi, A, Adachi, N, Kubota, Y, Azekawa, T, et al. Relationship between mood episode and employment status of outpatients with bipolar disorder: retrospective cohort study from the multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric clinics (MUSUBI) project. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2021) 17:2867–76. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S322507

33. Shinozaki, M, Yasui-Furukori, N, Adachi, N, Ueda, H, Hongo, S, Azekawa, T, et al. Differences in prescription patterns between real-world outpatients with bipolar I and ii disorders in the MUSUBI survey. Asian J Psychiatr. (2022) 67:102935. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102935

34. Sugawara, N, Adachi, N, Kubota, Y, Watanabe, Y, Miki, K, Azekawa, T, et al. Determinants of three-year clinical outcomes in real-world outpatients with bipolar disorder: the multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric outpatient clinics (MUSUBI). J Psychiatr Res. (2022) 151:683–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.05.028

35. Tokumitsu, K, Norio, YF, Adachi, N, Kubota, Y, Watanabe, Y, Miki, K, et al. Real-world clinical predictors of manic/hypomanic episodes among outpatients with bipolar disorder. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0262129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262129

36. Tokumitsu, K, Yasui-Furukori, N, Adachi, N, Kubota, Y, Watanabe, Y, Miki, K, et al. Real-world clinical features of and antidepressant prescribing patterns for outpatients with bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:555. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02967-5

37. Tsuboi, T, Suzuki, T, Azekawa, T, Adachi, N, Ueda, H, Edagawa, K, et al. Factors associated with non-remission in bipolar disorder: the multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric outpatient clinics (MUSUBI). Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2020) 16:881–90. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S246136

38. Yasui-Furukori, N, Adachi, N, Kubota, Y, Azekawa, T, Goto, E, Edagawa, K, et al. Factors associated with doses of mood stabilizers in real-world outpatients with bipolar disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. (2020) 18:599–606. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2020.18.4.599

39. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and Behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization (1992).

40. Carvalho, AF, Dimellis, D, Gonda, X, Vieta, E, McLntyre, RS, and Fountoulakis, KN. Rapid cycling in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. (2014) 75:e578–86. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08905

41. Pacchiarotti, I, Bond, DJ, Baldessarini, RJ, Nolen, WA, Grunze, H, Licht, RW, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. (2013) 170:1249–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020185

42. Kramlinger, KG, and Post, RM. Ultra-rapid and Ultradian cycling in bipolar affective illness. Br J Psychiatry. (1996) 168:314–23. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.3.314

43. Hajek, T, Hahn, M, Slaney, C, Garnham, J, Green, J, Růžičková, M, et al. Rapid cycling bipolar disorders in primary and tertiary care treated patients. Bipolar Disord. (2008) 10:495–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00587.x

44. Goldberg, JF, Wankmuller, MM, and Sutherland, KH. Depression with versus without manic features in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2004) 192:602–6. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000138227.25832.e7

45. Azorin, JM, Kaladjian, A, Besnier, N, Adida, M, Hantouche, E, Lancrenon, S, et al. Suicidal behaviour in a French cohort of major depressive patients: characteristics of attempters and nonattempters. J Affect Disord. (2010) 123:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.09.004

46. Selten, JP, Lundberg, M, Rai, D, and Magnusson, C. Risks for nonaffective psychotic disorder and bipolar disorder in Young people with autism Spectrum disorder: a population-based study. JAMA Psychiat. (2015) 72:483–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3059

47. Schiweck, C, Arteaga-Henriquez, G, Aichholzer, M, Edwin Thanarajah, S, Vargas-Cáceres, S, Matura, S, et al. Comorbidity of ADHD and adult bipolar disorder: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2021) 124:100–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.017

48. Milberger, S, Biederman, J, Faraone, SV, Murphy, J, and Tsuang, MT. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbid disorders: issues of overlapping symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. (1995) 152:1793–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.12.1793

49. Bauer, MS, Calabrese, J, Dunner, DL, Post, R, Whybrow, PC, Gyulai, L, et al. Multisite data reanalysis of the validity of rapid cycling as a course modifier for bipolar disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry. (1994) 151:506–15. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.506

50. el-Mallakh, RS, Vöhringer, PA, Ostacher, MM, Baldassano, CF, Holtzman, NS, Whitham, EA, et al. Antidepressants worsen rapid-cycling course in bipolar depression: a Step-Bd randomized clinical trial. J Affect Disord. (2015) 184:318–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.054

51. Wehr, TA, Sack, DA, Rosenthal, NE, and Cowdry, RW. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry. (1988) 145:179–84. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.2.179

52. Altshuler, LL, Post, RM, Leverich, GS, Mikalauskas, K, Rosoff, A, and Ackerman, L. Antidepressant-induced mania and cycle acceleration: a controversy revisited. Am J Psychiatry. (1995) 152:1130–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1130

53. Kukopulos, A, Reginaldi, D, Laddomada, P, Floris, G, Serra, G, and Tondo, L. Course of the manic-depressive cycle and changes caused by treatment. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychopharmakol. (1980) 13:156–67. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1019628

54. Wolpert, EA, Goldberg, JF, and Harrow, M. Rapid cycling in unipolar and bipolar affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry. (1990) 147:725–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.725

55. Angst, J. Switch from depression to mania--a record study over decades between 1920 and 1982. Psychopathology. (1985) 18:140–54. doi: 10.1159/000284227

56. Lewis, JL, and Winokur, G. The induction of mania. A natural history study with controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1982) 39:303–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290030041007

57. Lewis, JL, and Winokur, G. The induction of mania: a natural history study with controls. Psychopharmacol Bull. (1987) 23:74–8.

58. Fountoulakis, KN, Kontis, D, Gonda, X, and Yatham, LN. A systematic review of the evidence on the treatment of rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. (2013) 15:115–37. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12045

59. Calabrese, JR, Suppes, T, Bowden, CL, Sachs, GS, Swann, AC, McElroy, SL, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of lamotrigine in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2000) 61:841–50. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n1106

60. Frank, E, Swartz, HA, Mallinger, AG, Thase, ME, Weaver, EV, and Kupfer, DJ. Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: effects of changing treatment modality. J Abnorm Psychol. (1999) 108:579–87. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.579

61. Scott, J, Paykel, E, Morriss, R, Bentall, R, Kinderman, P, Johnson, T, et al. Cognitive-Behavioural therapy for severe and recurrent bipolar disorders: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. (2006) 188:313–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.4.313

Keywords: bipolar disorder, rapid cycling, euthymia, real world, mood stabilizer, outpatient, cross-sectional study, antidepressants

Citation: Takano C, Kato M, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Azekawa T, Ueda H, Edagawa K, Katsumoto E, Goto E, Hongo S, Miki K, Tsuboi T, Yasui-Furukori N, Nakagawa A, Kikuchi T, Watanabe K, Kinoshita T and Yoshimura R (2023) Clinical characteristics and prescriptions associated with a 2-year course of rapid cycling and euthymia in bipolar disorder: a multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric clinics. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1183782. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1183782

Edited by:

Jian Li Wang, Dalhousie University, CanadaReviewed by:

Taro Kishi, Fujita Health University, JapanYuji Ozeki, Shiga University of Medical Science, Japan

Copyright © 2023 Takano, Kato, Adachi, Kubota, Azekawa, Ueda, Edagawa, Katsumoto, Goto, Hongo, Miki, Tsuboi, Yasui-Furukori, Nakagawa, Kikuchi, Watanabe, Kinoshita and Yoshimura. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Masaki Kato, a2F0b21AdGFraWkua211LmFjLmpw

Chikashi Takano1

Chikashi Takano1 Masaki Kato

Masaki Kato Naoto Adachi

Naoto Adachi Eiichi Katsumoto

Eiichi Katsumoto Takashi Tsuboi

Takashi Tsuboi Norio Yasui-Furukori

Norio Yasui-Furukori Koichiro Watanabe

Koichiro Watanabe Reiji Yoshimura

Reiji Yoshimura