- Cha University, Seongnam, Gyeonggi, South Korea

Introduction: In art therapy, digital art therapy is a new method in which clients use digital media to express themselves creatively. We wanted to explore what this means for adolescents with disabilities. The purpose of this qualitative case study was to explain what kind of experience they had when digital media was applied as an expressive and therapeutic medium in group art therapy in which adolescents with intellectual disabilities were participants and what kind of therapeutic meaning the experience had. We tried to know the therapeutic factors by extracting the implications of meaning.

Methods: Participants were second-year high school students with intellectual disabilities who belonged to special classes. They were selected in an intentional purposive sampling method. Five teenagers with intellectual disabilities participated in 11 group art therapy sessions. Data were collected through interviews, observation, and digital artwork collection. Collected data were case studies analyzed using an inductive approach. In this study, the use of digital media was defined and utilized as “Digital Art Therapy” by setting the scope related to the study according to client’s behavioral method.

Results: As a digital generation accustomed to smartphones, the participants gained confidence by repeatedly acquiring new technologies through familiarity with the media. Interaction with the media through touch and the use of apps have promoted autonomy with interest and pleasure to disabled teenagers, allowing them to express themselves actively. In particular, digital art therapy induces a holistic sensory experience by mobilizing visual images that could represent various expressions, emotions felt in music and tactile senses that made texts for people with intellectual disabilities with difficulty in verbal communication.

Discussion: Art therapy using digital media has become an important experience that provides opportunities to arouse curiosity, enjoy creative activities, and express positive emotions vividly to adolescents with intellectual disabilities who have difficulties with expression and communication and a sense of lethargy. Therefore, it is suggested that an in-depth understanding of the characteristics and differences between traditional and digital media is necessary, and that complementary use to help create therapeutic purposes and art therapy is important.

1. Introduction

We are currently living in an era of digital transformation. The emergence of the 4th Industrial Revolution has led to an acceleration of digital technology. The COVID-19 pandemic has only further accelerated the use of digital technology (1). New digital technologies including metaverse, Augmented Reality (AR), and Internet of Things (IoT) focusing on artificial intelligence (AI). Telemedicine and online education are all expected to spread, evolve, and continue to be extensively developed with increasing demands throughout the world (2, 3).

One arena in which the importance of digital technology can be highlighted is art therapy. Art therapy can promote self-exploration and understanding by using the creative process of artwork as a means of self-expression and communication (4–6). Recently, the field of art therapy is using online platforms to activate community and creativity among therapists (7), With the COVID-19 pandemic started in 2020, the field of art therapy is rapidly transitioning to remote work to cope with the pandemic (8). It also prepares for the future by improving accessibility and acceptability to treatment using new art media (9).

Digital media was first used as a communication tool in art therapy by Weinberg (10), who attempted to apply computer technology to rehabilitation for people with disabilities. The medium used in art therapy is a media of expression. Digital media has been attracting attention as a new tool to attract interest and provide opportunities for artistic expression due to the characteristics of digital media (11).

In the new media era, digital media has evolved and developed in a wide range of areas, including remote art therapy, phototherapy, animation, and virtual reality (VR) using computer and graphic programs as well as creative expressions (12, 13). Recently, numerous apps for digital art production have been released that target a wide range of users, including many young customers of the digital generation. Despite the explosive spread of art-making apps (e.g., apps for digital drawing and painting, visual journalism, storytelling, animation, and multimedia), many art therapists lack experience and skills in using digital media in treatment (14). Moreover, research on this topic has progressed relatively slowly (9). Those who were born in the digital age, i.e., “digital natives” (15), recognize the utility of technology in treatment with familiarity and convenience (16). They also prefer to express their feelings through images, text, or video in their work activities, as they consider the digital space their main space (17, 18).

Malchiodi (11) has stated that digital media accessible to people with disabilities can promote a new therapeutic relationship. Previous studies have shown that the use of digital media with hospitalized children (19, 20) or in limited medical environments in clinical art therapy can allow patients to virtually experience media that they cannot experience in real life (11). Studies have revealed the usefulness of digital media in art therapy because digital media can enable patients to experience media that they could not experience in real life through digital media (21–24).

International Classification of Health of Functioning Disability was approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) defines “disability” as an interaction between multidimensional factors at the individual, social, and physical levels (25). People with disabilities have more limited access to digital technology than the general public (26, 27). The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) has reported that people with disabilities have digital information gaps in their online activities and internet use in various environments compared to people without disabilities (28). In the rapidly changing environment of the modern world, digital technology’s hyperconnectivity, convenience, and subjectivity are more needed for people with disabilities who require some form of assistance or have physical constraints. To reduce such digital information gap, there is a need for digital inclusion that does not exclude or marginalize anybody (29). Moreover, using digital media for communication is essential for students with disabilities to successfully transition to society after graduation and live meaningfully (30).

According to the US National Center for Education Statistics (31), from 2020 to 2021, 7.2 million students from 3 to 21 years old received special education services under the Disabled Education Act (IDEA), thus accounting for 15% of all public school students. This number has also been showing an increasing trend. Intellectual disability is defined as a condition characterized by significant limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior before age 22 (32, 33).

According to the American Psychiatry Association (APA, 2013), intellectual disability is a condition that begins during development and is characterized by deficits in both intellectual intelligence and adaptive functioning in conceptual, social, and practical domains (34). In the Republic of Korea, intellectual disabilities account for the most significant proportion of the total number of students with disabilities at 51.8% (35). For teenagers with intellectual disabilities, attending special classes can cause various psychological stresses such as anxiety and perceived inferiority because of one’s disability, the formation of low self-esteem, frustration, and atrophy due to frequent failure experiences (36). They might also face difficulties in social adaptability due to emotional expression that is either socially marginalized or limited and contraction of interpersonal relationships (32). Therefore, there is a greater need for therapeutic intervention for psychological and emotional problems of students with intellectual disabilities than among general students.

Art therapy for adolescents with intellectual disabilities can provide them opportunities for expression and communication through alternative visual media (37). Art therapy in the educational scene was, initiated by Edith Kramer (38), It has been shown that art could be a powerful communication tool based on all humans’ creativity (39). In addition, for students with disabilities who are usually protected and raised, art provides them a significant opportunity to function independently. They can feel joy, pleasure, and a sense of achievement in the experience of controlling materials at will (40).

In the Republic of Korea, art therapy services are provided during creative experience classes and after-school classes in special schools and general schools for children and adolescents with disabilities. For children and adolescents with special needs, art therapy in a school environment can provide them an opportunity to overcome obstacles to educational success (41, 42). In addition, strengthening programs for students who are identified as disabled can help them realize their social and academic potential by promoting appropriate social behavior and emotional development (41, 42). In this way, the clinical work of art therapy is gradually expanding into education and special education environments (43).

Technology provides many people with pleasant experiences and new opportunities (44). The playful interaction behavior offered by digital media provides sensory enjoyment, which drives art creation (45–48). The spontaneous and action-promoting characteristics of such interaction behavior have positive functions that can be useful for adolescents with intellectual disabilities who have low expression, who are depressed, who have low self-esteem, and who lack attention and motivation (49). Studies on the use of digital media for people with intellectual disabilities in art therapy (49–51) are very lacking, especially in group art therapy for adolescents with intellectual disabilities. It was difficult to find case studies that applied it as a medium of communication. Therefore, in art therapy using digital media, there is a need for extensive research on various subjects and case studies to understand the therapeutic process.

This study proposes a new method of participation for creative expression, selection, and control by therapeutically applying digital media, a form of communication and self-expression culture, to teenagers with intellectual disabilities so that they can enjoy the universal right to human equality. Moreover, a case study has been performed to obtain specific knowledge by understanding and exploring research participants through a therapeutic process and to understand the phenomenon in the art therapy process. To this end, the following research questions are explored in this study:

1. What are experiences of adolescents with intellectual disabilities in group art therapy using digital media?

2. What are meanings that can be extracted from experiences of adolescents with intellectual disabilities with group art therapy using digital media?

3. What are therapeutic factors of group art therapy using digital media for adolescents with intellectual disabilities?

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Research design

The present work used a qualitative case study approach to explore and understand experiences of individuals who had group art therapy in 11 sessions, from surface level observations in a natural setting to in-depth analyses (52). Phenomena of specific cases were described in a deep and natural context. New meanings were discovered based on the experiences reported by participants and data obtained from the phenomena observed by the researcher (53). The goal of the case study method was to investigate how, why, what was happening and what factors were related to the phenomenon (54). The purpose of qualitative case study is to explore and understand the experiences, meanings, and therapeutic factors of research participants through various data collection and analysis steps, while considering characteristics of manners (55).

2.2. Research procedure

The participants in this study were five students (one male student and four female students) in special classes at M high school in S city. The group art therapy program was conducted once a week from September 2019 to December 2019 by connecting creative experience classes for a semester over a total of 11 sessions (120 min for each session). This study used an institutional-centered art therapy program composed for special purposes. After explaining the purpose and method of the study to the teacher in charge of the special class, this study was reviewed and approved by the school.

Participants were all second-year high school students with intellectual disabilities who belonged to special classes. They were selected with a purposive sampling method (52). Based on the selection criteria for adolescents who submitted written consent, research participants and their parents (main guardians) were explained about the purpose and procedure of this study.

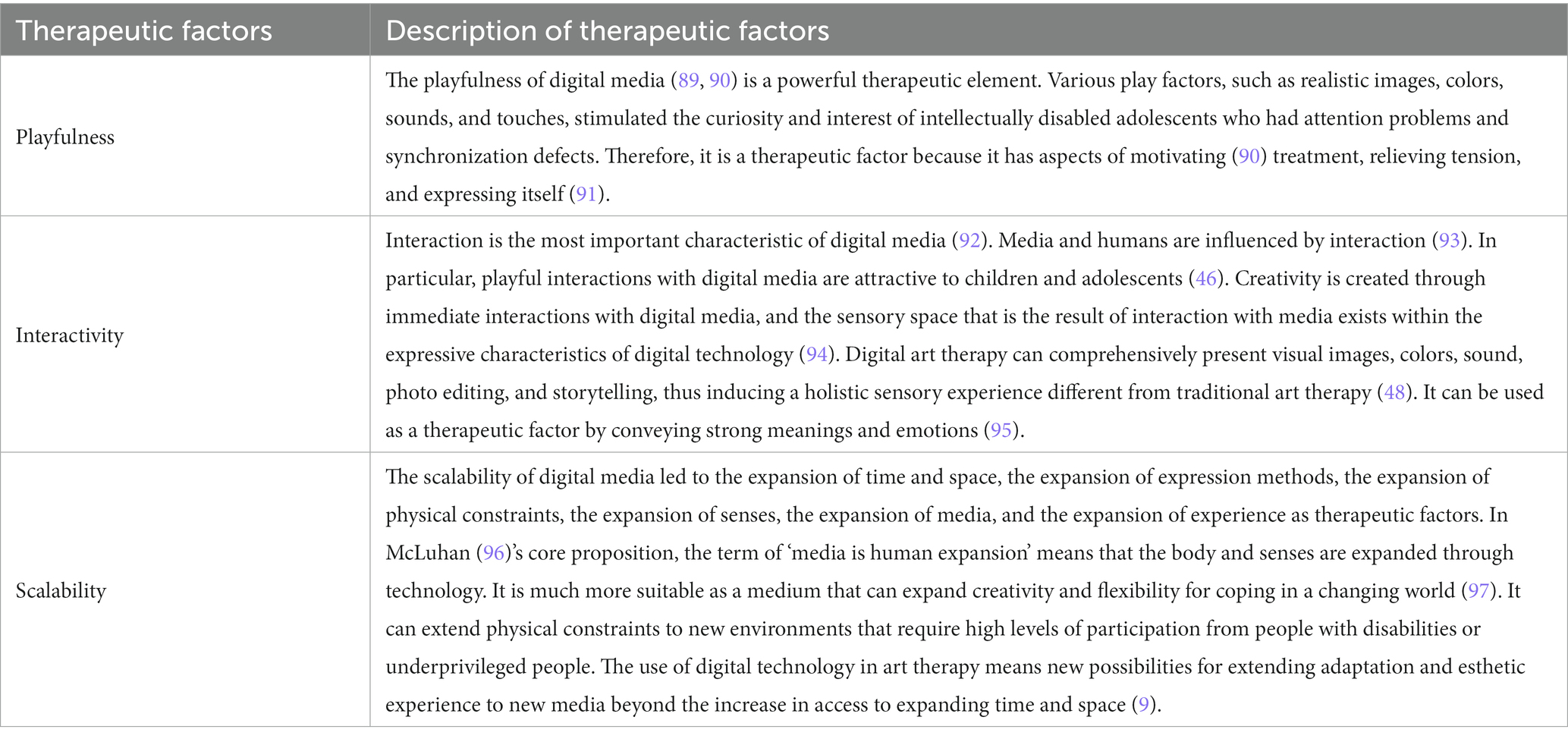

Personal information and characteristics of the participants in this study were obtained based on reports of special class teachers and observations of researchers. In this paper, aliases were used to protect research subjects (Table 1).

Table 1. Personal information as well as social and emotional characteristics of research participants.

2.3. Case conceptualization

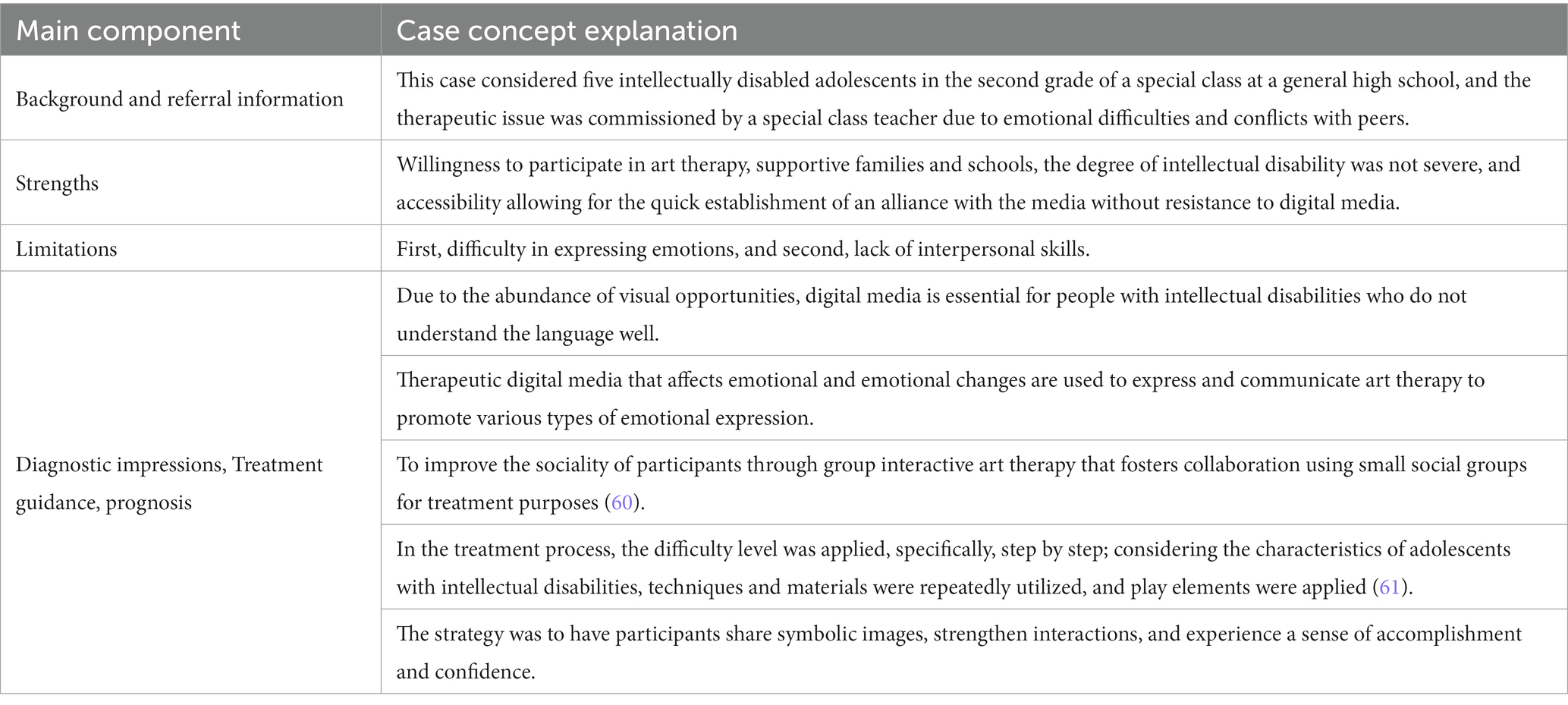

A case conceptualization is a method and clinical strategy for organizing obtained information about clients, for understanding and explaining clients, planning treatment interventions, and for establishing a consistent treatment strategy (56, 57). Case conceptualization is essential in psychotherapy (58). It was developed for art therapist responsibility and confidence in treatment (59). It has been used to increase the likelihood of treatment goals (57). Thus, the researcher identified problems, causes, and strengths based on various information related to the main complaints of participants and planned treatment using case conceptualization to obtain further improved results (Table 2) (60, 61).

2.4. Data collection and data analysis

Data were collected through interviews, observation, and document collection using the triangulation method (62). The average interview was about 30 min, there were two semi-structured interviews after initial and mid-term sessions along with one group interview after the end of sessions. Group dynamics were observed by having participants fill out semi-structured questionnaires to obtain abundant information (63).

Before starting the interview, the researcher explained to the participant that the interview content would be recorded and transcribed by the researcher, with anonymity and confidentiality of the interview content guaranteed. Consent was then obtained from each participant before the interview. We also shared individual results with participants after the study. In this process, terms related to informed consent were converted into easy-to-understand terms according to the level of understanding of the participants. The researcher proceeded with open questions within a large framework of the research problem (63). Participants were able to understand the purpose of this study and express their opinions based on their own experiences.

The document collection process included audio recordings and transcriptions of each session of art therapy by researcher, observation notes taken on-site, structured behavioral evaluations, and texts and artworks (audio-visual materials such as images and videos). Data analysis involved describing cases and contexts. Repeated comparative analyses using open coding, categorization, and category verification procedures were performed (64).

The researcher tried to find meaningful patterns, concepts, and topics by repeatedly reading the data (65). The interpretation summarized greater meanings of cases discovered by the researcher through analysis strategies using direct interpretation from the overall perspective according to the researcher’s intuition, reflective thinking, use of imagery, and application and search of new and diverse perspectives (66).

2.5. Trustworthiness

To secure the reliability of this study, opinions were exchanged with an academic adviser during research analysis and interpretation. The appropriateness of the data collection and coding contents was supervised. The researcher focused on revealing the experience and meaning of the research participants through data analyzed with a focus on fairness and consistency to minimize preconceptions. In order to exclude the researcher’s subjectivity as much as possible and to strengthen the sensitivity and reliability of the collected data, colleagues with a master’s degree who participated as observers and assistant therapists checked before and after the session and received feedback. A peer debriefing session was then held (67).

2.6. Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in class hours and within the scope of the curriculum at the special class of the school. After explaining the purpose and intended use of the study to all participants and their guardians in advance, written consent was voluntarily provided by them. The written consent form promised to protect the information and ensure anonymity of the participants. Participants and their guardians were explained that research data of this study would be discarded after being stored in a safe place for 5 years.

Ethical problems related to the use of digital media were supplemented by considering ethics codes for the confidentiality of electronic information suggested by the British Columbia Art Therapy Association (5), the American Art Therapy Qualification Board (68), and the Korean Art Therapy Association (KATA) (69).

All six iPads used in this study were set and encrypted with the researcher’s IDs so that information on these six iPads used in this study would not be leaked. After using the app, the tablet device used by participants was initialized to prevent data leakage. All data files stored in the form of electronic information were stored with passwords. All recorded contents and data were guaranteed to be discarded following completion of the study.

2.7. Procedure: description of group process

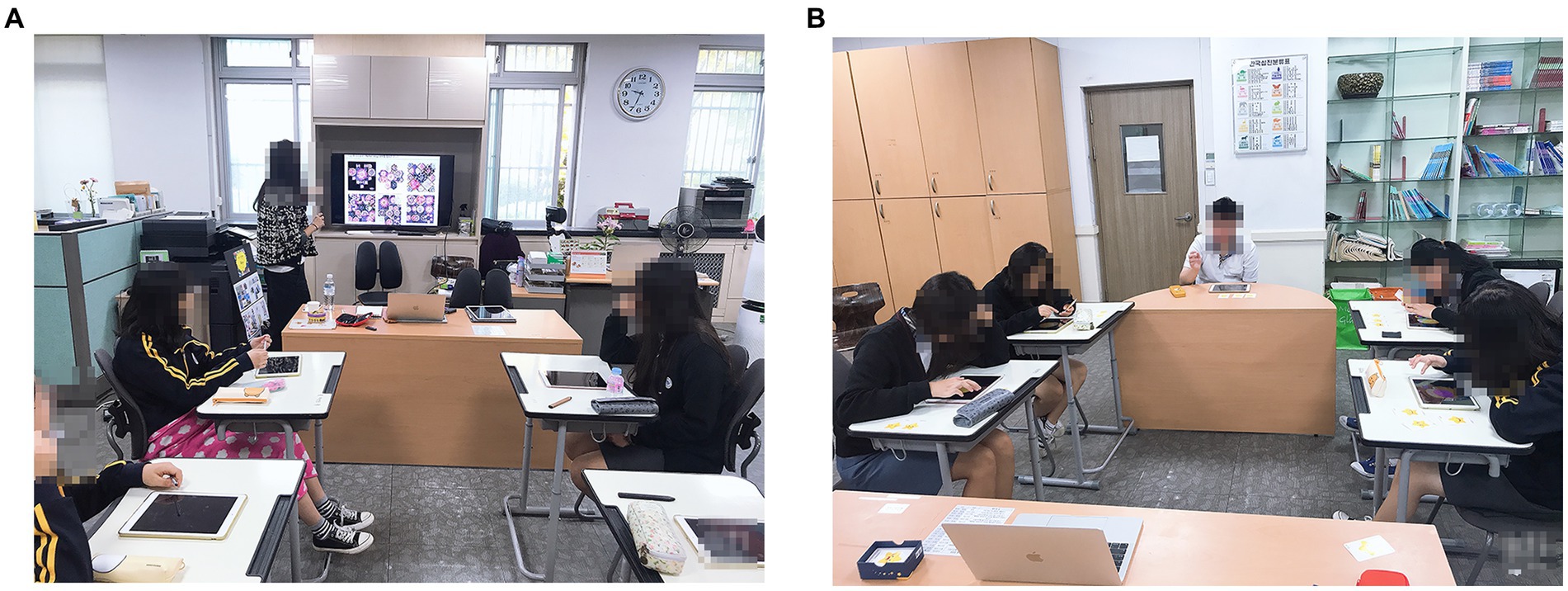

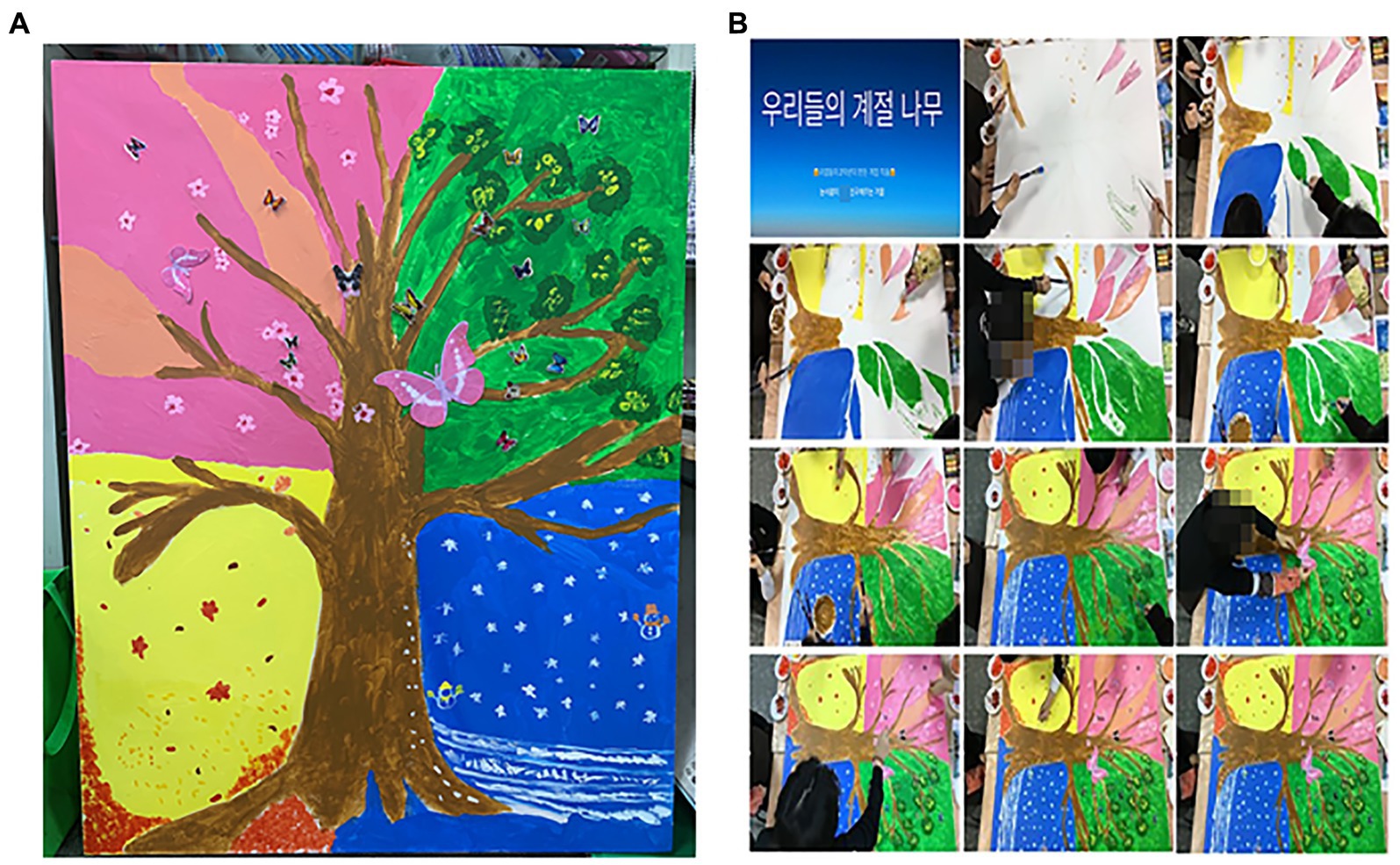

In the art therapy environment, students’ desks were relocated to the center to face each other, and their interactions were observed. Technical education and practice on the iPad and the app are known to be important (70). Thus, a TV monitor located in front of the classroom was connected to the researcher’s laptop and iPad to model the app’s usage and iPad drawing process. Audio-visual materials on art therapy topics were shared by participants (Figure 1A). Moreover, five new iPad 9.7 32G units were rented for participants to have a 1:1 iPad art therapy environment (Figure 1B).

2.8. Treatment plans

This study applied Richter’s (71) “Art therapy’s approach to art therapy education based on education” by changing the difficulty and technique of digital media in consideration of the characteristics and learning levels of adolescents with intellectual disabilities (72).

The goal of art therapy is to improve emotional expression and strengthen sociality so that participants can complete high-quality works through the complementary usage of traditional media and digital media (73). Participants planned to freely express their psychological state using various functions of media as a generation familiar with digital media (74, 75). When using digital media in art activities, the therapist’s competence and ethical understanding of the media are essential factors (22, 76). The researcher participated in Today at Apple (experiential group session) provided by the Apple Store to increase their literacy and acquire skills in digital media utilization. They also received training on how to use apps, devices, photos, videos, coding, art, and design. The researcher demonstrated and supplemented a direct program before each session. The therapy was based on the experience of using digital media in clinical practice.

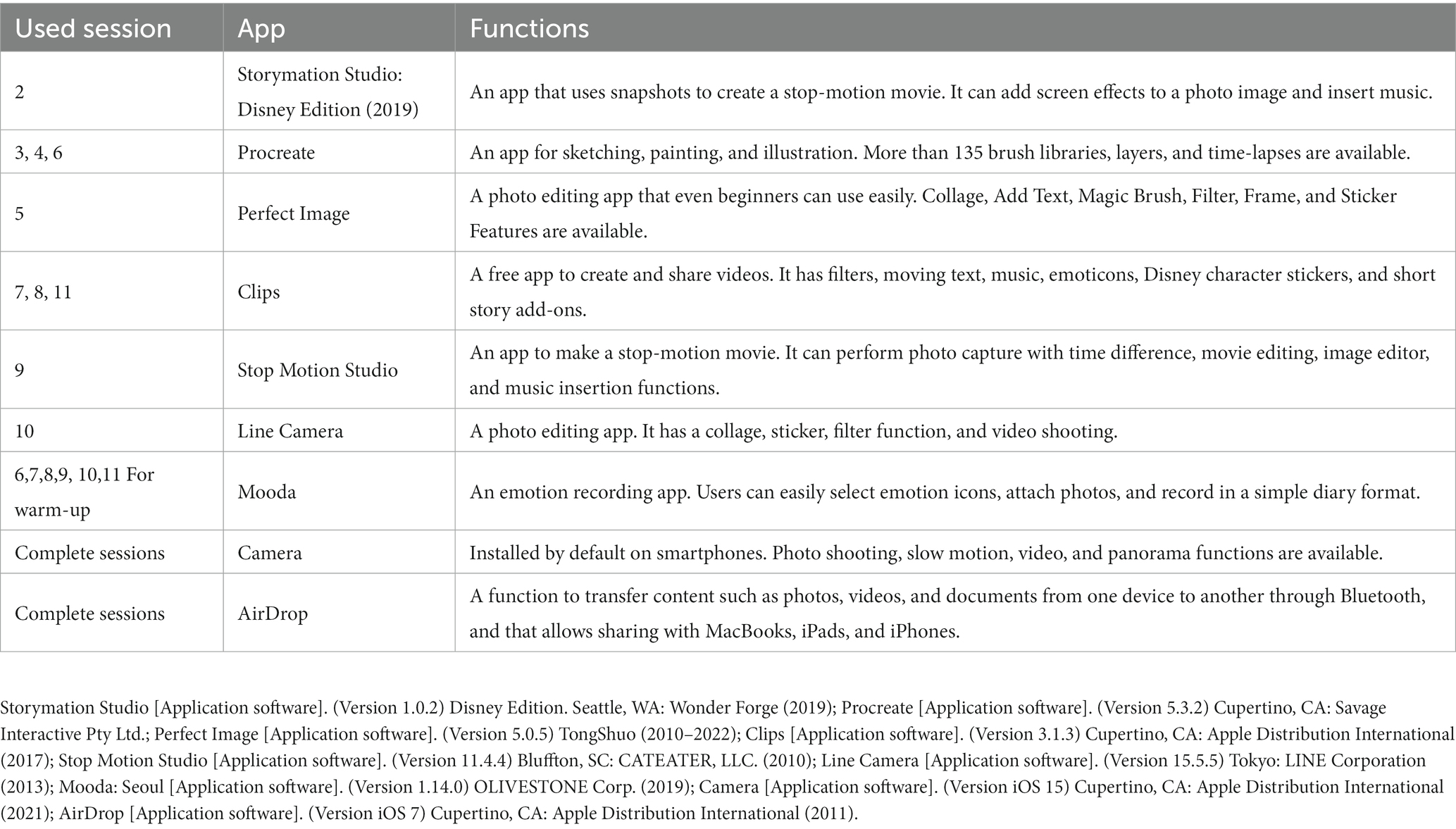

The researcher chose an iPad and iOS app considering that they are familiar to teenagers using smartphones, easy to access, and easy to carry. Specific expression techniques used in digital art therapy include digital painting, photography, video, stop motion, and digital collage. Apps used in this study for this are summarized in Table 3.

2.9. Sessions

The digital art therapy program was conducted in three stages: initial, intermediate, and advanced (Table 4). It was structured in consideration of cognitive, social, emotional and short-term aspects of adolescents with intellectual disabilities. After the intermediate stage, it was flexibly changed and finally implemented so that participants could autonomously decide on the topic they wanted. In terms of digital media utilization, the process and changes in the session were observed in an initial session followed by ten further sessions. The first session used traditional media. Another five sessions (2, 5, 7, 9, 10) had the complementary use of traditional media and digital media. Another five sessions (3, 4, 6, 8, 11) used digital media.

2.9.1. Initial stage (sessions 1–3)

In the initial stage, the focus was on relieving tension and building a relationship of trust. To build trust with participants, guidelines for art therapy and the rules to be followed within the therapy time were set together.

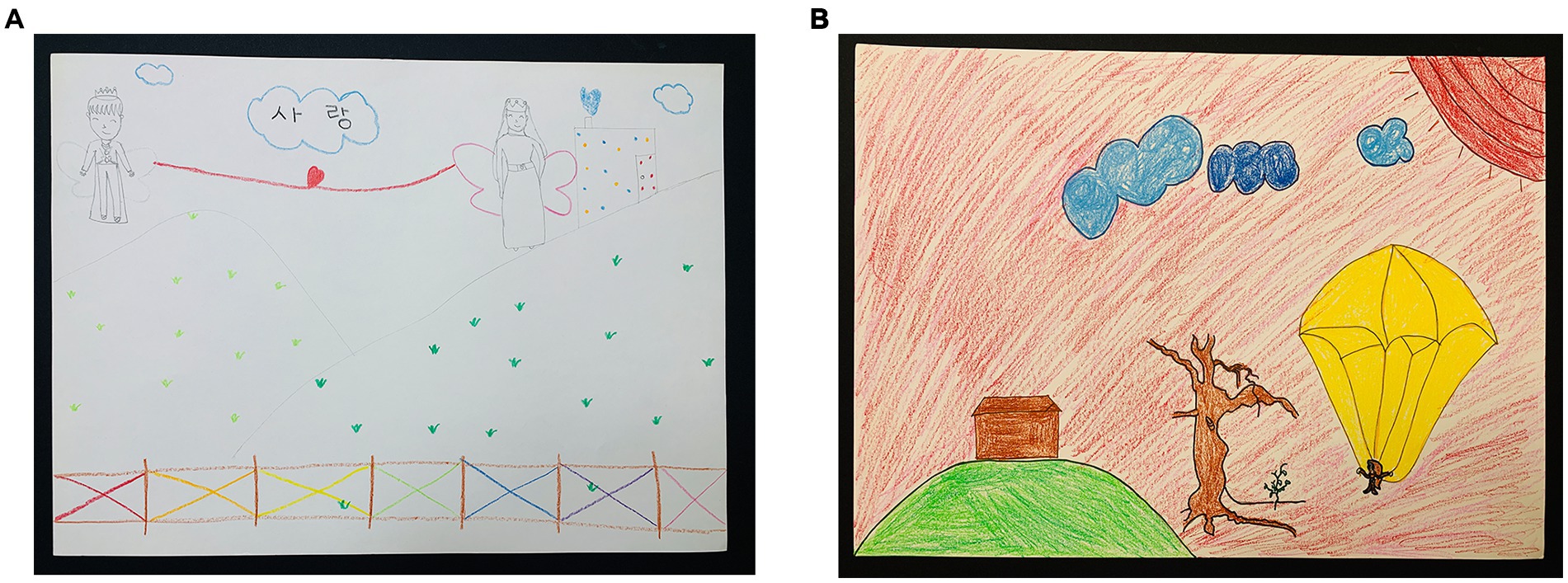

2.9.1.1. Session 1: creating my own story

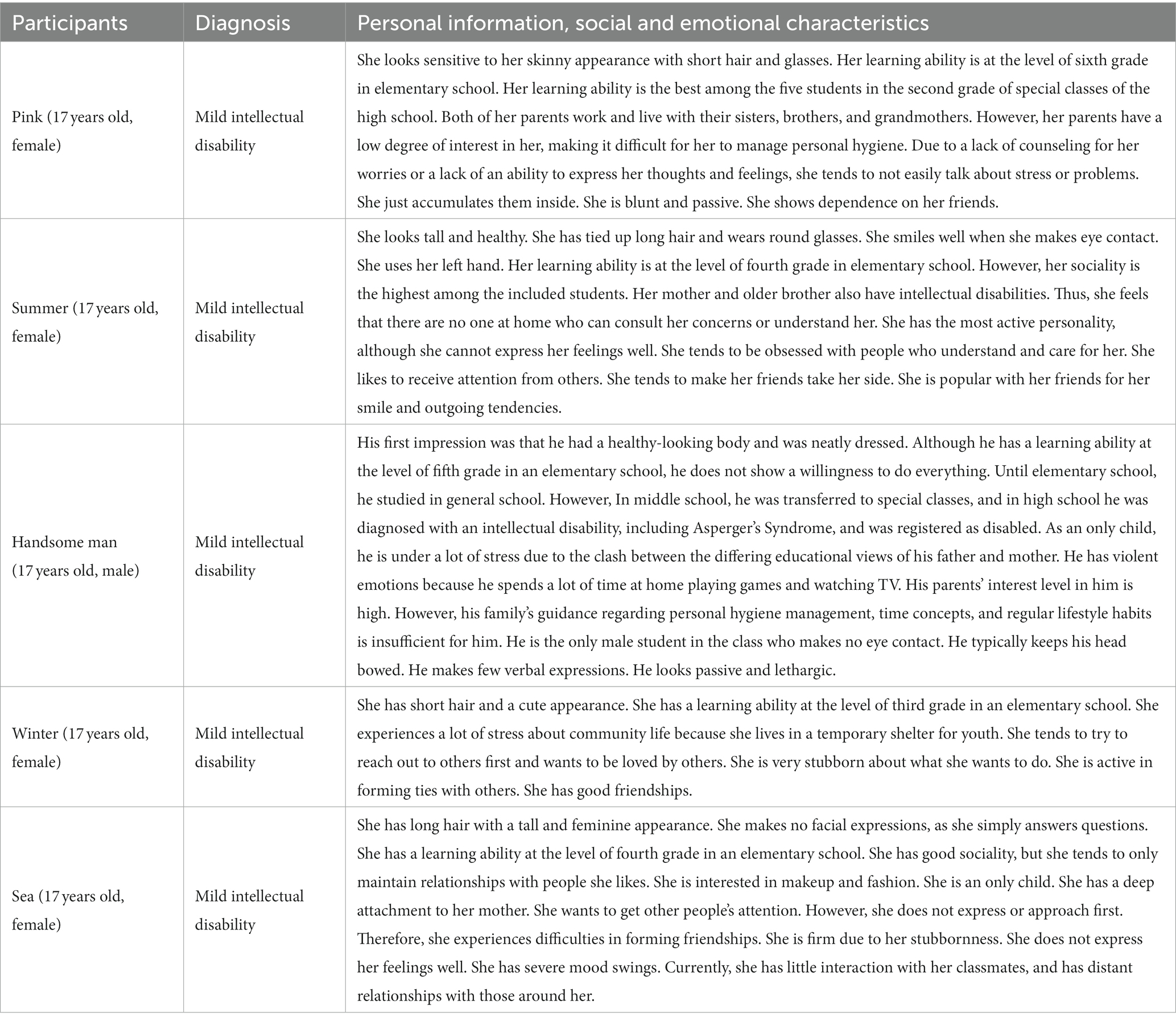

In the first session, traditional media (Colored pencil, felt-tip pen, and eight-section drawing paper) and picture cards were used to draw story pictures (Figures 2A,B). Participants actively and sincerely engaged in the work process, although their progress was slow. For that reason, it seemed necessary to distribute planned time.

Participants were observed to habitually say negative words created by the experience of failure, such as “I’m doomed, “and “It is driving me crazy, “in the creative process. Thus, continuous emotional support and encouragement for the participants seemed necessary. The first session was a meaningful session as an opportunity for social interaction within the group, taking the first step in experiencing and expressing empathy by telling stories about themselves, although participants were not familiar with using art images.

2.9.1.2. Session 2: safe space

In the second session, clay was used for emotional expression or sensory activation (Figure 3A). Opportunities for expression were expanded by using different types of digital media together. The researcher used the easy-to-access Storymation Studio: Disney Edition app to motivate participants and attract the interest of teenagers who like animation. Participants intuitively searched through the media (77). They showed interest in the function of the app and willingness to use it on their own from filming to editing. In the process of creating an animation, participants said “Wow, it is like a game,” “It is like being a film director,” “It is fun,” “I like it because it is like a movie, “I like this music the most, and This is the prettiest, ‘unlike their relaxing appearance in clay work’”. They were careful in choosing backgrounds, effects, and music. Participants increased their interactions by showing their digital artwork (Figure 3B; Supplementary Video S1). While watching the completed artworks together, they were all delighted by the moving visual images and the vitality given to the animation by the music.

Figure 3. (A) Sea (Park and a Bird). (B) Sea’s stop-motion animation (see also Supplementary Video S1).

After the session, Sea approached the researcher and asked, “What’s the name of this app?” and said, “I want to go home and try it again” while smiling brightly. Participants showed emotional changes in the process of their artwork and put metaphors into the work. Attractive aspects of digital media also helped form a trust relationship between the participants and researchers.

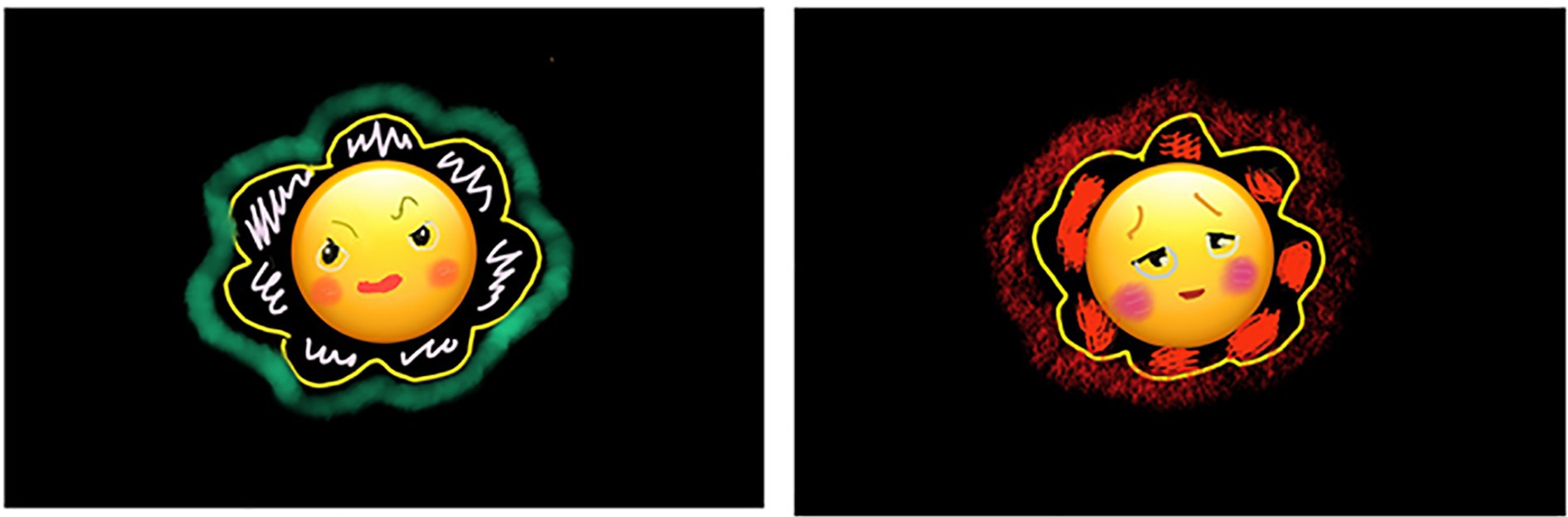

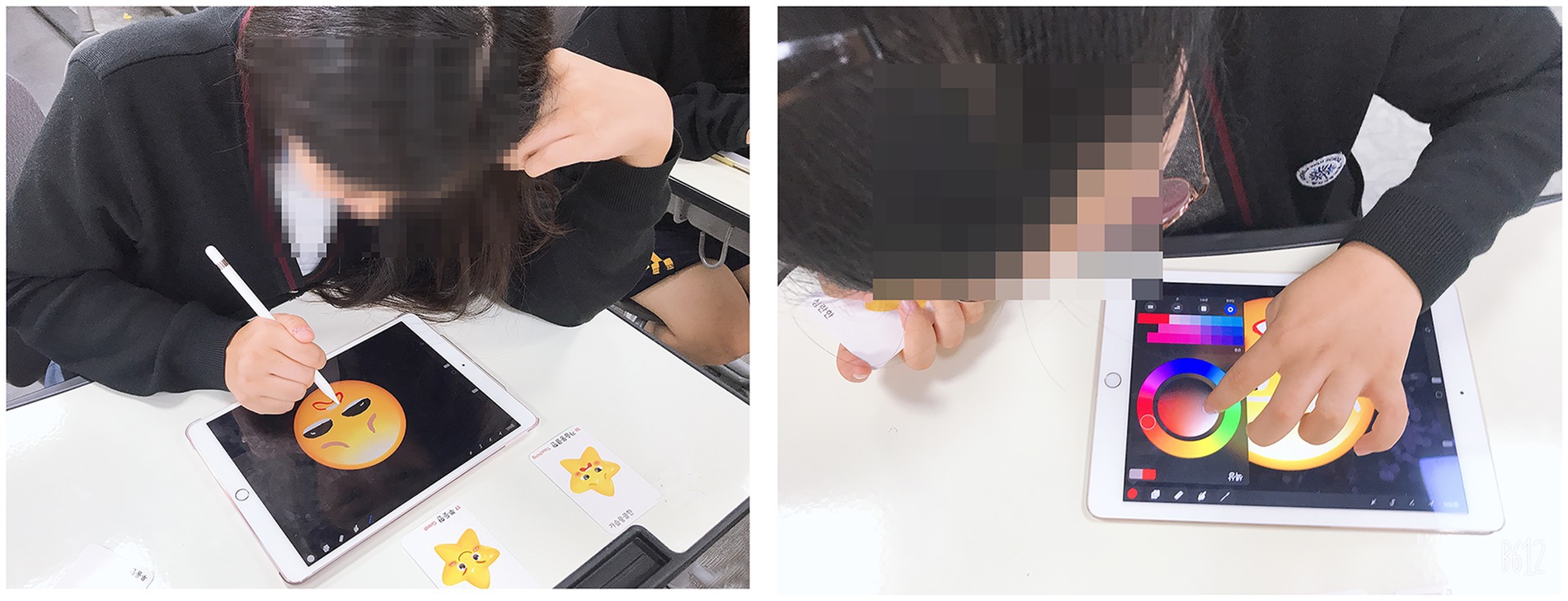

2.9.1.3. Session 3: creating emotions

Before starting this session, the researcher modeled the process of drawing by connecting the iPad to a TV monitor. This session involved the use of the Procreate app under the theme of making friendly emoticons that could be easily accessed due to the role-played by smartphones in daily life (Figure 4). Participants used iPad as a canvas and worked as shown in (Figure 5) using their fingers and Apple pencil or Stylus pen.

This was an opportunity for participants to understand each other by sharing emotional images. After completion, they made statements such as “It was fun and fun after expressing my feelings,” “I felt relieved and comfortable,” and “I was just happy without thinking about anything.” All participants responded that it was much more fun than drawing on drawing paper. They were also satisfied with the convenience involved in resizing images using digital media and easily correcting mistakes.

Although it was difficult for participants to express emotions using spoken language, they could better express themselves through digital artworks. Participants were able to share information and understand each other by talking about emoticons that expressed each other’s feelings.

2.9.2. Intermediate stage (sessions 4–8)

Starting from sessions in the intermediate stage, participants were given autonomy and flexibility so that they could decide on the desired topic on their own. The app was used repeatedly, so that participants would master the technical aspects.

2.9.2.1. Session 4: a self-portrait of pop art

In the 4th session, with the theme of self-portrait drawing in pop art, the Procreate app used last time was used repeatedly. Pink started by saying she was not confident, but after completing the self-portrait, Pink praised herself, saying that “I did a great job, Pink.” She was delighted to write her name on her work (Figure 6A). After completing the self-portrait, Handsome man wrote “disabled fool” on his work and showed a negative self-concept (Figure 6B). Handsome man recognized his disability and revealed his thoughts about himself through self-portraits.

Participants enjoyed the process of painting the self-portrait, expressed a sense of accomplishment after completion, and showed therapeutic importance of the artwork by valuing it. Participants familiarized themselves with technical aspects by repeatedly using the same app. During the talk time, they used the AirDrop app to instantly share their artwork which helped the group communicate.

2.9.2.2. Session 5: me and our garden

In the fifth session, participants smelled the scent of flowers. The classroom was full of flowers, which awakened their senses, thus allowing them to have a moment of relaxation and healing. In this session, the Perfect Image app with a photo collage function was used. Participants all experienced unity through cooperative artwork while creating a garden together (Figure 7B). After completion, they captured their desired parts by taking pictures to recreate a photo collage (Figure 7A).

While participants were creating the mandala works (diameter 25 cm), their emotions were stabilized with positive emotions were aroused. There was a change in interaction that provided altruism, praise, and encouragement to friends. Handsome man took more than 140 pictures while producing a nice photo collage and said, “It’s a nice garden.” Actively created photos re-visualize images through photo collages and create new stories. Creative possibilities were also expanded to photo collage artworks that fused traditional media and digital media.

2.9.2.3. Session 6: if I were ~

In the sixth session, the Procreate app was used. The participants drew pictures on their iPads, handed them over to other participants, and created a “Digital painting rotation” in which they drew pictures in addition to the pictures they received from other participants. Participants had to add layers to the received picture and draw it to prevent other people’s paintings from being erased, and the record of the picture was stored separately (Figure 8A). Therefore, it was possible to confirm the contribution of each participant to the single work.

Pink expressed her complex feelings with colors and lines, saying that she was not in good condition. When her painting (Figure 8B) was returned, she smiled, saying that she was pretty when she left, but that she was struck by lightning. Pink talked about the pleasant parts and the unpleasant parts in the additional painting. Digital painting, which can be drawn by dividing the picture into separate layers, was easy to modify later, and participants were able to engage in the activity with less burden.

This session gave participants opportunities to sympathize with others through perspective-taking, interest, and imagination. It was also an opportunity to express their future dreams and communicate with images.

2.9.2.4. Session 7: making wishes

For the seventh session, Participants were motivated by the program of ‘Making a wish bracelet’ that they selected themselves. They worked with an immersive focus. This session involved creating a video (Figure 9) that documented the process of artistic expression as a Clips app for video production. The process of making bracelets gave them an opportunity to solve problems while being original. Participants chose colors, shapes, and materials. They edited videos together and expressed positive emotions through the experience of collaborative work.

Figure 9. Wish bracelet video collaborative work. Soundtrack: Itsudemo by Asuka Ito (Genre: Bright fully) (The soundtrack is music that accompanies and synchronizes with the images of the participant’s video work and is edited by the participants directly selecting the music they want).

Participants showed the importance of their digital artwork by inserting various moving stickers and text to express emotions. Sea expressed her joy and satisfaction by inserting the words. “Satisfaction with what I made today, Today is the best day, Hooray” in the video. Participants started to praise themselves by feeling a sense of accomplishment. They encouraged each other and showed positive relationship experiences and interactions in the group art therapy.

2.9.2.5. Session 8: a fantasy trip

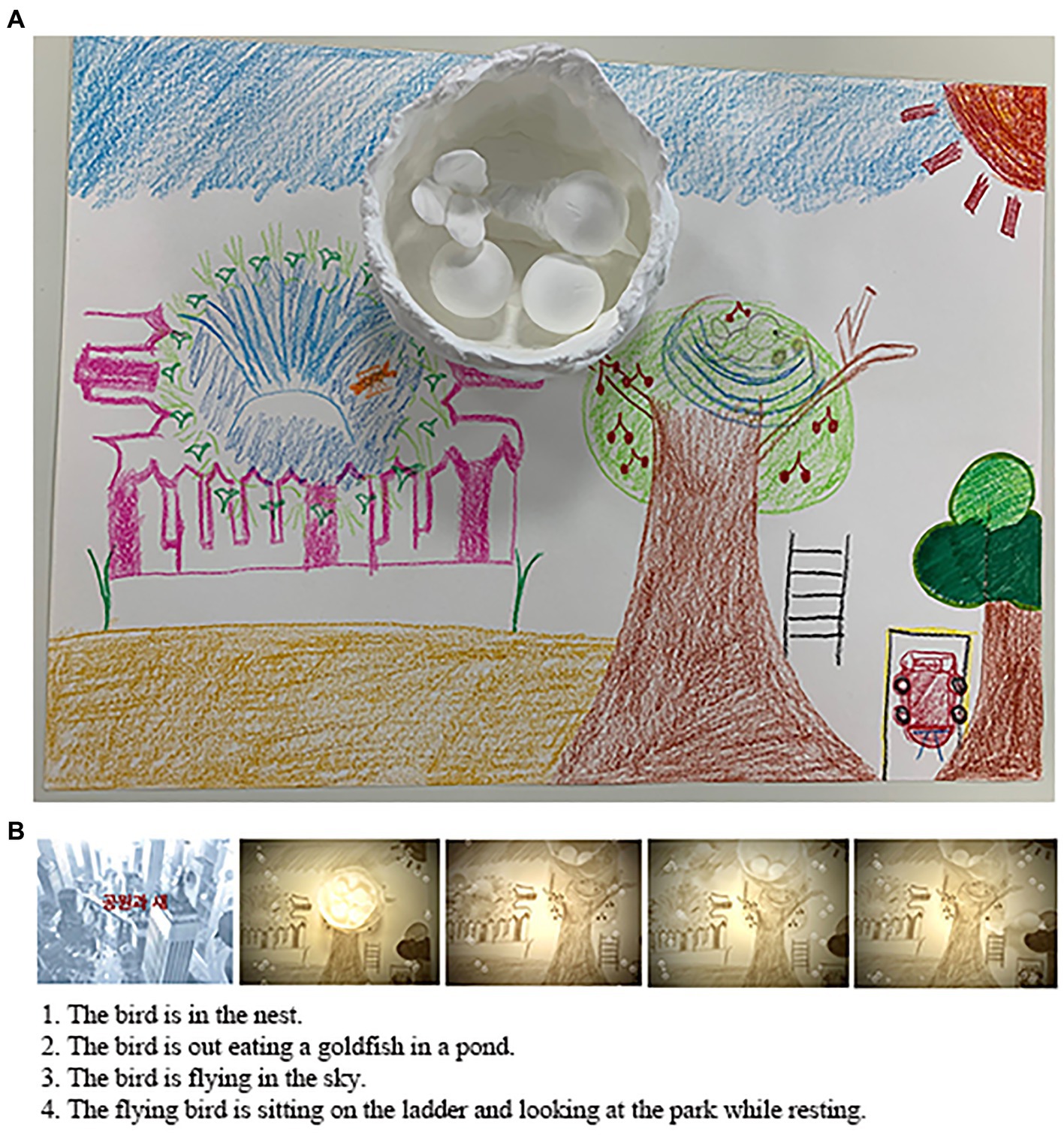

The theme of the trip, which was the most frequently expressed theme in participants’ wishes in the seventh session, was made into a video using the Clips app. Participants said they were happy just thinking about the trip plan. Photos of their travel destinations contained emotions and information through symbolic meanings. Participants were immersed in making videos of their dream trip. They expressed excitement and expectation.

Summer often expressed her expectations and excitement after deciding on New York and Hawaii as travel destinations, for which she carefully planned, saying, “There are so many places I want to go here.” She made a highly complete work called “Exciting Travel” (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Summer’s “Exciting Travel” video. Soundtrack: So Young at Heart by Judson Crane (Genre: relaxed).

Participants were able to actively express themselves with audio-visual stimulation of multimedia. Emotions they felt in the music were harmonized with their visual stimuli. The liveliness of the completed video satisfied their emotions by mobilizing the touch of making text.

2.9.3. Advanced stage (sessions 9–11)

In the advanced stage, with goals of enhancing self-confidence and improving social skills through positive emotional experiences and a sense of achievement, the process of change in the past was examined, focusing on completion of collaborative works, exhibitions of works, and art journaling.

2.9.3.1. Session 9: our seasonal trees

In the ninth session, the participants drew trees together on a 50P (Paysage) canvas as a collaboration project in the advanced stage. With the Stop Motion Studio app, the work activity process was captured with a total of 417 photos, ultimately leading to the completion of a 1-min and 25-s-long stop-motion movie (Figure 11B). Participants completed their respective areas, looked at the overall harmony, cared for and helped their friends, and showed a mature appearance that gave meaning to the importance of the process of completing the work together. Participants coordinated their opinions and showed teamwork in determining the title, music, background, and effect of the artwork together. They were also able to appreciate the stop-motion movie artwork and view their roles objectively. When setting the title of the work, Handsome man surprised everyone by loudly suggesting “Our Seasonal Tree” (Figure 11A).

Figure 11. (A) Our seasonal tree (116.8 × 80.3) canvas, acrylic paint. (B) Stop-motion movie of our seasonal tree (Theme music: Cherry Monday) (The theme music is music that harmonizes with the image of the stop-motion movie work, and the members of the participants select and edit the music they want).

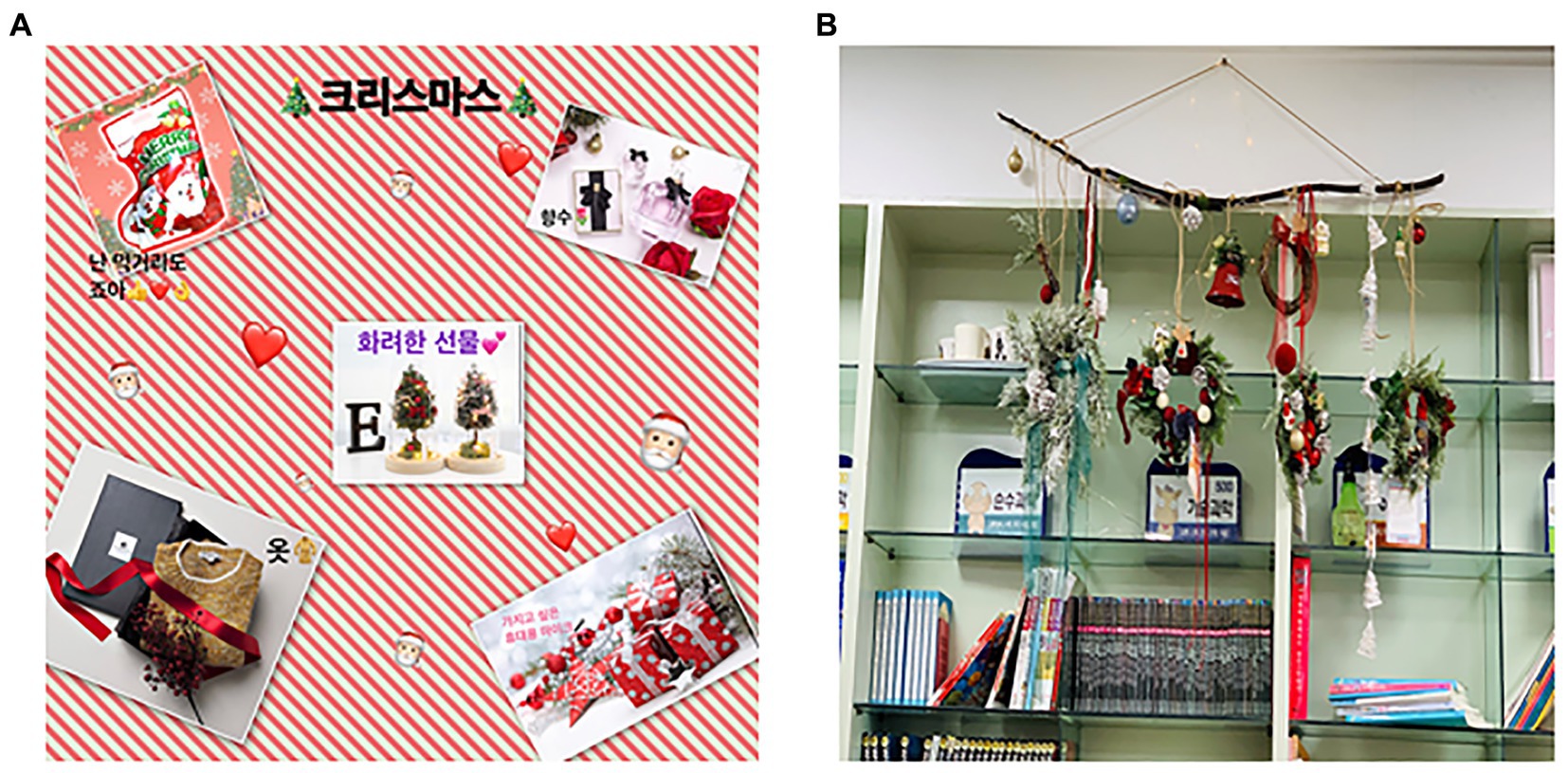

2.9.3.2. Session 10: Christmas gift

This session began with a laugh among participants who prepared Santa hats and Rudolph headbands. The 10th session involves the creation of a digital collage (Figure 12A) and a Christmas wreath using the Line camera app. Participants had experience in magazine collage. Thus, they understood the digital collage quickly and completed the work in a short time because it was easy to edit. Parts that could be transformed without damaging the original, such as adjusting the size of the picture, aroused participants’ interest. Collage is a technique with the greatest metaphorical potential (78). Participants felt grateful and happy. They expressed positive emotions as they thought about the grand prize under the theme of Christmas gifts. Afterward, they gathered their completed wreaths and made a Christmas Garland together, turned on the lights, and cheered and applauded. Participants were very proud of their work. They took pictures together in front of their works (Figure 12B) and hung them in the classroom to display them.

2.9.3.3. Session 11: say “goodbye”

As the “Media Art Exhibition” was held as a closing session that involved a group celebration, participants aimed to reflect on the process of growth throughout the therapy process and became aware of their changes. The 11th session involved using the Clips app to complete a modern media art journal in which images, narratives, music, and editing were done within a single digital media. During digital artwork activities, participants approached their friends and worked together. They showed an improved relationship wherein they were interested in. They cheered for their friends’ artwork. Titles of art journals created by participants reflected main themes of their experiences.

Pink was embarrassed while looking at her works in each session and danced while choosing music during the media art journal. She showed elevated expressions in terms of behavior as well as verbal expressions. Summer said that she could get to know more about her friends by watching the exhibition. She laughed and said about her work, “It’s a very well-made video, but there are so many things I want to say right now, so it’s a pity that I could not put them all into the work.” Images and writings had been added to each work to the end. Expressing high satisfaction after completion, the title of the artwork was called ‘Precious Memories’ (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Summer’s “Precious memories” (Media art journal video). Soundtrack: Itsudemo by Asuka Ito (Genre: delightfully).

3. Results

The main results of this study were an analysis of participants’ experiences and meanings of participants using digital media and descriptions of therapeutic factors.

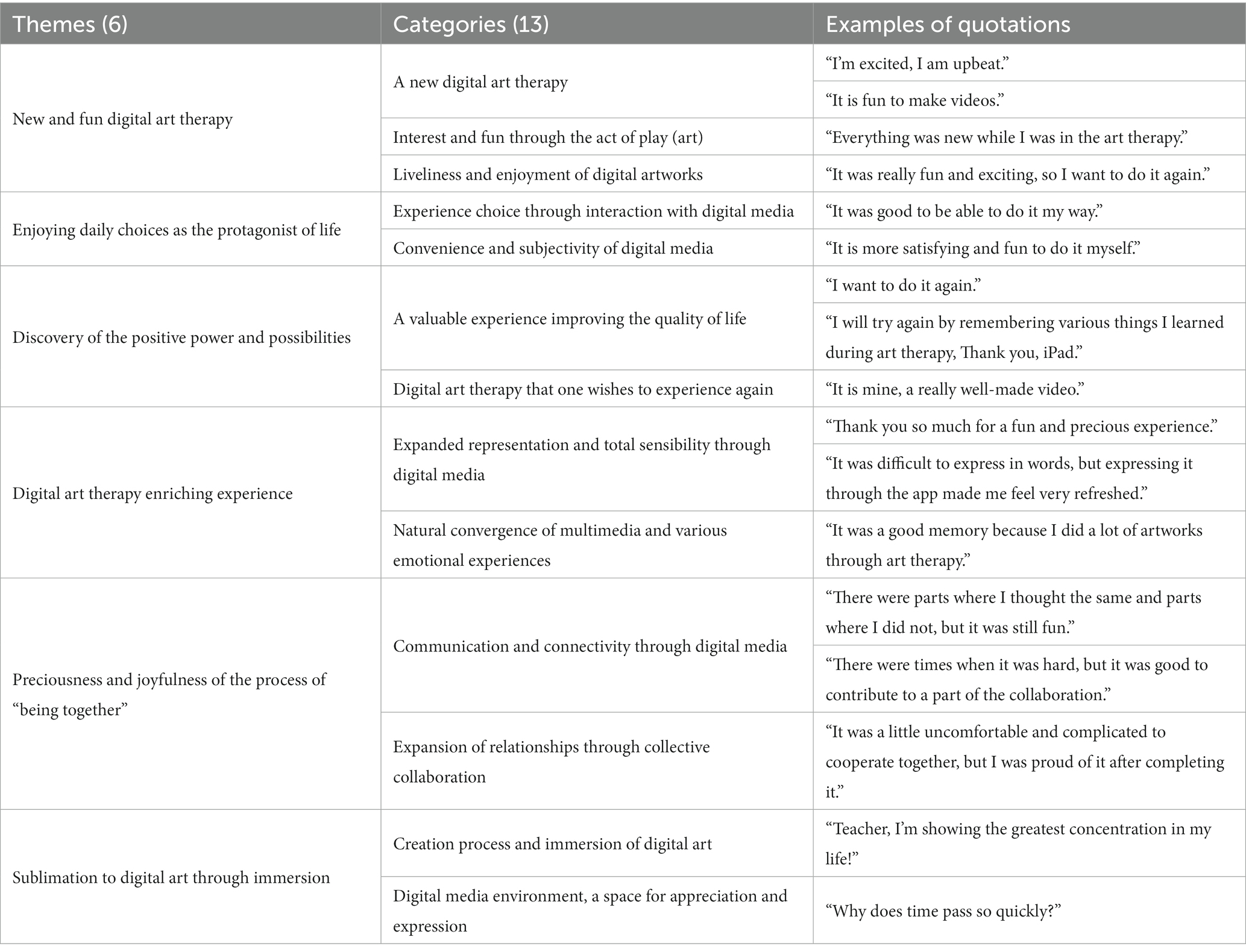

3.1. Analysis of experience and meaning of group art therapy using digital media

Experiences and associated meaning of the group art therapy were identified through coding, categorization, and subjectification by comparing and reviewing artworks, interview transcription contents, and observation journals for 11 sessions of group art therapy. Meaning was derived from a total of six themes and 13 subcategories representing experiences derived through repetitive comparison and line-by-line analysis were found (Table 5).

3.1.1. Theme 1. New and fun digital art therapy

In the interview, participants said that their first experience of creating work using an iPad was “incredible.” This new experience might represent the first step toward life improvement and change.

Participants had more stories and laughter as they created artworks with digital media. Interactions with digital media can enhance the aspect of play. Their effects give pleasure (79). Fun is the core of humanity (80). Fun has important implications for human development (81).

3.1.2. Theme 2. Enjoying daily choices as the protagonist of life

Participants felt more freedom and satisfaction in the session about subject they voluntarily selected. Adolescents with intellectual disabilities have limited choices and opportunities due to family control and social exclusion, and they experience exclusion due to a lack of awareness regarding technology and digital information (82). Digital media works cannot be created without active participation (45, 83). Since its use itself represented a choice, it was confirmed that it was meaningful for participants to enjoy daily options as a protagonist of life.

3.1.3. Theme 3. Discovery of the positive power and possibilities

Participants said that their experiences in art therapy would be helpful in their daily lives. These responses mean that they discovered their hidden potential through digital art therapy and felt positive power such as competence and confidence. Participants were more motivated by the acquisition of skills in the use of iPads and apps.

3.1.4. Theme 4. Digital art therapy enriching experience

Rubin (38) has stated that adolescents with intellectual disabilities have a greater desire for emotional experiences and creative activities due to various deficiencies. Participants experienced various new self-expressions and rich emotional experiences through convergence between media. The difference between digital art therapy and traditional art therapy is that digital media has a non-material aspect, which not only amplifies bodily sensations but also triggers heightened behaviors, bringing participants another bodily experience.

3.1.5. Theme 5. Preciousness and joyfulness of the process of “being together”

Participants said that the experience of group art therapy would represent a pleasant memory. They put the importance on cherishing times during which they complete the work with friends and collaborated happily together. Through group art therapy, participants attached meaning to the importance of collaboration. The connectivity of digital media helped communicate by allowing their work to be shared immediately and quickly. It also improved sociality by having a positive effect as a tool for communication between participants, thus improving their social skills.

3.1.6. Theme 6. Sublimation to digital art through immersion

Participants said that when making digital art works with iPads, they concentrated better, and time went by faster. This meant that digital media increased participants’ immersion and motivation to participate (84–88) and sublimated them into emotional sublimation through the expression of catharsis and integrated digital art creation in the art therapy process.

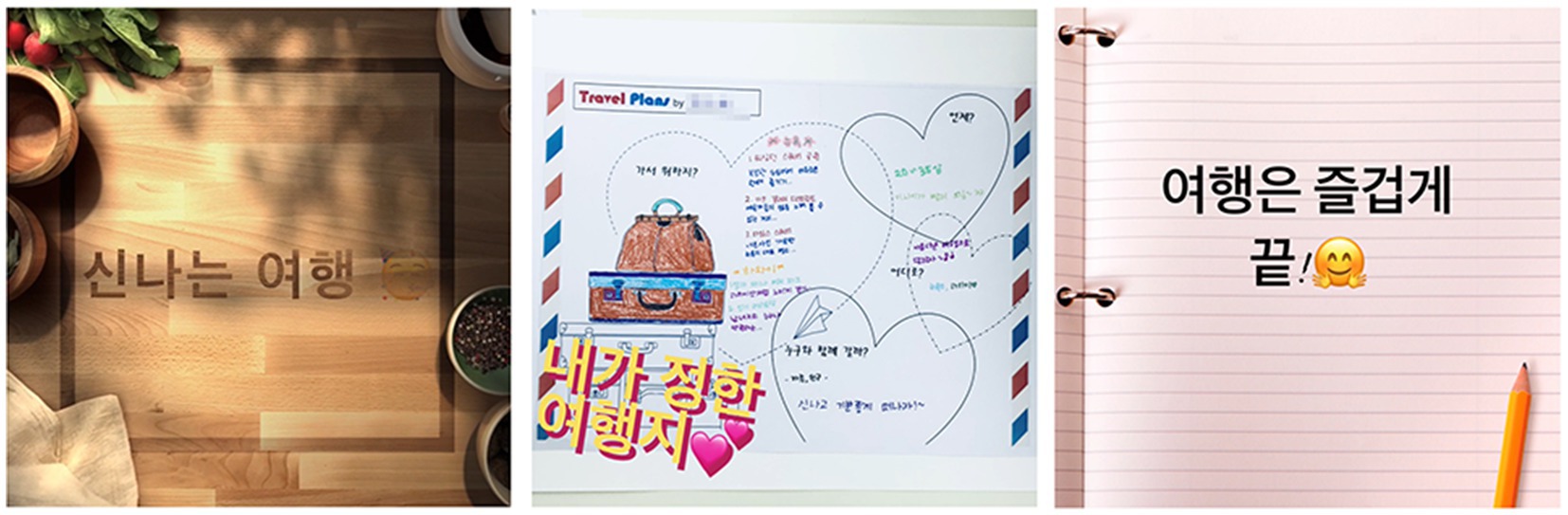

3.2. Therapeutic factors of group art therapy using digital media in adolescents with intellectual disabilities

Therapeutic factors that were extracted and used to investigate the meaning of the group art therapy experience of adolescents with intellectual disabilities using digital media were playfulness, interactivity, and scalability of digital media (Table 6) (9, 48, 89–97).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore participants’ experiences and meanings when applying using digital hardware tablets and software apps as delivery devices for expressive and therapeutic media in group art therapy for adolescents with intellectual disabilities.

Results of the present study are consistent with those of Weinberg (10), who argues that computer-based art therapy has unique advantages to grant curiosity and motivation for patients with disabilities as a new approach to a successful art experience. Malchiodi (11) has also shown that digital media can improve concentration and self-esteem, consistent with the results of the present study. This study is also in line with the study of Garner (12), who argues that the use of digital art media can improve choice and autonomy among students with disabilities. Wehmeyer and Metzler (98) have emphasized the importance of autonomy for students with disabilities to have a successful transition to social life.

Participants in the present work experienced sensory expansion, various emotional experiences, and natural convergence between media in the process of engaging in the artwork activities. This supports Mcniff’s belief (13) that all-in-one digital devices are promising as a fusion art production tool. The results of this study are also consistent with Hallas and Cleave’s (51) claim that, for many people, technology can increase opportunities for realizable experiences such as playing, creativity, and improving quality of life, therefore contributing to primary prevention and health promotion.

Therapeutic use of digital media can enhance the emotions of adolescents with less expression and lethargy. It can also maximize the experience of participants in various expression methods to provide satisfaction and achievement. Therefore, it has the potential to become a strong therapeutic factor. Characteristics of digital media also support studies of Ehinger (99) and L’Esperance (100), who have explained that digital media can increase adaptation and increase both communication and relationship formation in art therapy. Results of this study are also consistent with a recent study by Albrecht et al. (45), which has shown that interactive digital art can be a useful therapeutic intervention, particularly for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

This study was meaningful in that it applied therapeutic digital media to adolescents with intellectual disabilities in special education classes who had emotional difficulties to help them understand the process, and draw conclusions through an actual case analysis depicting the phenomenon of digital art therapy with rich and detailed technology.

5. Limitations and recommendations for future studies

First, this study considered adolescents with intellectual disabilities attending special classes in a high school in the Republic of Korea. Therefore, there is a need for future studies using various media to determine the possibility of using digital art therapy for adolescents with other types of disabilities.

Second, the initial purchase price of digital media is high. There might be an economic burden when it is used in group art therapy. However, in the long term, compared to high-quality traditional art materials, apps—which are software—can be transformed into cost-effective tools.

Third, to use digital media, there is a need for further research on software that can be combined with art therapy, and education in various application programs. Moreover, since few apps have been developed for use in art therapy, convergence research and development between interdisciplinary studies are necessary.

Fourth, digital art therapy and traditional art therapy are complementary to each other. Traditional and digital media have different characteristics in nature or expressive characteristics (11). Therefore, it is necessary for practitioners to have an in-depth understanding of both characteristics and differences between traditional and digital media. The author would like to suggest the importance of a complementary use of them for therapeutic purposes and for assisting in art therapy activities.

6. Conclusion

This study analyzed experiences and therapeutic meanings of adolescents with intellectual disabilities in group art therapy using digital media to derive six themes: (1) New and fun digital art therapy; (2) enjoying daily choices as the protagonist of life; (3) Discovery of the positive power and possibilities; (4) Digital art therapy enriching experience; (5) Preciousness, and joyfulness of the process of “being together”; and (6) Sublimation to digital art through immersion. Therapeutic factors that these themes imply in digital media have been identified as playfulness, interactionality, and scalability. The results of this study show that the use of digital media provides unlimited possibilities for participants to freely express their emotions in new ways and can improve various sensory experiences and creativity. This was an opportunity to develop positive relationships, improve self-esteem, and develop digital literacy skills by amplifying emotions of teenagers with intellectual disabilities and by changing their thinking, feelings, and acting in the process of communicating with the media. This qualitative case study provides implications that digital media can be a beneficial therapeutic intervention as it can provide everyone with more opportunities, including those with disabilities.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

JK and YC performed the conception and design this study. JK wrote the manuscript. YC critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants and their families. The authors would like to thank YC for guiding the thesis and Tae-Eun Kim and Joo-Yeun Han for improving the quality of the thesis. The authors want to thank our colleagues who helped us with the group art therapy session.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1172079/full#supplementary-material

References

1. World economic forum (WEF). World Economic Forum Annual Meeting (2023). Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/01/davos23-digital-transformation-investment-priority-downturn/ (accessed March 22, 2023).

2. Shon, CB, and Lee, JY. Phenomenological case study of the experience of telehealth digital art therapy in a self-quarantined person before confirmed with COVID-19. J Korea Contents Assoc. (2020) 20:646–8. doi: 10.5392/JKCA.2020.20.12.646

3. Fouad, AA, Osman, MA, Abdelmonaem, YMM, and Karim, NAHA. Awareness, knowledge, attitude, and skills of telemedicine among mental healthcare providers. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. (2023) 30:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s43045-022-00272-3

4. American Art Therapy Association (AATA). Definition of art therapy. (2023). Available at: https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy/ (accessed January 22, 2023).

5. British Columbia Art Therapy Association (BCATA). (2018). Introduction to the BCATA Code of Ethics Available at: https://bcarttherapy.com/bcata/about-bcata/ethics-and-grievances/ (accessed November 2, 2022).

6. Canadian Art Therapy Association (CATA). What is art therapy? (2023). Available at: https://www.canadianarttherapy.org/what-is-art-therapy/ (accessed January 22, 2023).

7. American Art Therapy Association (AATA). About our members: AATA at a glance 2021. (2021). Available at: https://arttherapy.org/news-member-infographic (accessed January 22, 2023).

8. Miller, G, and McDonald, A. Online art therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Art Ther. (2020) 25:159–18. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2020.1846383

9. Zubala, A, Kennell, N, and Hackett, S. Art therapy in the digital world: an integrative review of current practice and future directions. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:595536. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.600070

10. Weinberg, D. The potential of rehabilitative computer art therapy for the quadriplegic, cerebral vascular accident and brain trauma patient. Art Ther. (1985) 2:66–72. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1985.10758788

11. Malchiodi, CA. Art therapy and computer technology: A virtual studio of possibilities. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers (2000).

12. Garner, RL. Exploring digital Technologies for artbased special education models and methods for the inclusive K-12 classroom. New York, NY: Routledge (2019).

13. McNiff, S. The virtual art therapy studio. Art Ther. (1999) 16:197–18. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1999.10129484

14. Garner, R. Digital art therapy: Material, methods, and applications. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers (2016).

15. Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 2: do they really think differently? On Horizon. (2001) 9:1–6. doi: 10.1108/10748120110424843

16. Darewych, OH, Carlton, NR, and Farrugie, KW. Digital technology use in art therapy with adults with developmental disabilities. J Dev Disabil. (2015) 21:95–102.

17. Shamri, ZL. Making art therapy virtual: integrating virtual reality into art therapy with adolescents. Front Psychol. (2021) 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.584943

18. Jones-Kavalier, BR, and Flannigan, SL. Connecting the digital dots: literacy of the 21st century. Educ Q. (2006) 29:8–10.

19. Malchiodi, CA, and Johnson, ER. Digital art therapy with hospitalized children In: CA Malchiodi, editor. Art therapy and health care. New York, NY: The Guilford Press (2013). 106–21.

20. Thong, SA. Redefining the tools of art therapy. Art Ther. (2007) 24:52–8. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2007.10129583

21. Campbell, S, and Linn, N. The video movie project. Afterimage. (2001) 29:8. doi: 10.1525/aft.2001.29.3.8a

22. Carlton, NR. Digital culture and art therapy. Arts in Psychother. (2014) 41:41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2013.11.006

23. Choe, SN. An exploration of the qualities and features of art apps for art therapy. Arts Psychother. (2014) 41:145–4. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2014.01.002

24. Horoviz, EG. Apps, telehealth, and art therapy: online treatment and ethical issues for the digital age In: M Audrey, editor. Exploring ethical dilemmas in art therapy: 50 clinicians from 20 countries share their stories. London: Routledge (2019)

25. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Disability (2023). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/disability#tab=tab_1 (accessed March 14, 2023).

26. Good Things Foundation. Health inequalities and mitigating risks of digital exclusion. (2021). Available at: https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/insights/health-inequalities-and-mitigating-risks-of-digital-exclusion/ (accessed November 2, 2022).

27. Johansson, S, Gulliksen, J, and Gustavsson, C. Disability digital divide: the use of the internet, smartphones, computers and tablets among people with disabilities in Sweden. Univers Access Inf Soc. (2021) 20:105–18. doi: 10.1007/s10209-020-00714-x

28. National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). New NTIA data show enduring barriers to closing the digital divide, achieving digital equity. (2022). Available at: https://www.ntia.doc.gov/blog/2022/new-ntia-data-show-enduring-barriers-closing-digital-divide-achieving-digital-equity (accessed November 2, 2022).

29. Chadwick, D, Ågren, KA, Caton, S, Chiner, E, Danker, J, Gómez-Puerta, M, et al. Digital inclusion and participation of people with intellectual disabilities during covid-19: a rapid review and international bricolage. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. (2022) 19:242–6. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12410

30. Stone, E Digital-exclusion-and-health-inequalities-briefing-paper. Good-things-Foundation-2021 (2021). Available at: https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Good-Things-Foundation-2021-%E2%80%93-Digital-Exclusion-and-Health-Inequalities-Briefing-Paper.pdf (accessed November 2 2022).

31. National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Report on the condition of education. Washington: U.S. Department of Education (2022).

32. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) Definition of intellectual disability. (2022). Available at: https://www.aaidd.org/intellectual-disability/definition (accessed November 2, 2022).

33. National Institute of Health (NIH). Intellectual and developmental disabilities. (2018). Available at: https://archives.nih.gov/asites/report/09-09-2019/report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheet34ef.html?csid=100&key=I#I (Accessed 15 January 2023).

34. American Psychiatry Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatry Association (2013).

35. Ministry of Education. Special education statistics. (2021). Available at: https://www.gne.go.kr/upload_data/board_data/workroom/162728022614418.pdf (accessed November 2, 2022).

36. Park, BL. A qualitative study for the experiences of special education teachers and assistants after sitting and joining in the after-school art therapy. Korean J Art Ther. (2012) 19:1543–67. doi: 10.35594/kata.2012.19.6.012

37. Hackett, SS, Ashby, L, Parker, K, Goody, S, and Power, N. UK art therapy practice-based guidelines for children and adults with learning disabilities. Int J Art Ther. (2017) 22:84–94. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2017.1319870

39. Lowenfeld, V, and Brittain, L. Creative and mental growth Seoul National University of Education art education research society. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company (1957).

41. Shostak, B, DiMaria, A, Salant, E, Schoebel, N, Bush, J, Minar, V, et al. Art therapy in the schools. A position paper of the American art therapy association. Art Ther; J Am Art ther Assoc. (1985) 2:19–21. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1985.10758776

42. Siegel, CA. School art therapy In: DE Gussak and ML Rosal, editors. The Wiley handbook of art therapy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (2015)

43. Regev, D. Arts therapies with children and adolescents. Children. (2023) 10:110. doi: 10.3390/children10010110

44. Jackson, K. Where qualitative researchers and technologies meet: lessons from interactive digital art. Qual Inq. (2017) 23:818–6. doi: 10.1177/1077800417731086

45. Albrecht, L, Starnes, H, Benton, K, Bol, A, Gettings, E, and Dagenhard-Trainer, P. Interactive digital art for individuals with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil. (2021) 26:442–4. doi: 10.1177/1744629520975554

46. Ferri, G, Sluis-Thiescheffer, W, Booten, D, and Schouten, B. Playful cognitive behavioral therapy apps. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children (2016).

47. Lee, SJ, and Yoo, HB. A study on game-playing plasticity of modern art focused on media arts. J Korean Digit Content Soc. (2010) 11:503–11.

48. Han, JY. Possibilities in application of art therapy employing digital contents with play-instinct of the art. J Korean Soc Media Arts. (2015) 13:145–60.

49. Lewchuk, DR, D'Amico, M, and Timm-Bottos, J. Developmental Disabilities (Empreintes numériques: exploration de l’inclusion numérique chez les adultes ayant une déficience développementale). Can J Art Ther. (2021) 34:52–62. doi: 10.1080/26907240.2021.1982171

50. Donnari, S, Canonico, V, Fatuzzo, G, Bedetti, C, Marchiafava, M, Menna, M, et al. New technologies for art therapy interventions tailored to severe disabilities. Psychiatr Danub. (2019) 31:462–6.

51. Hallas, P, and Cleaves, L. ‘It’s not all fun’: introducing digital technology to meet the emotional and mental health needs of adults with learning disabilities. Int J Art Ther. (2017) 22:73–83. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2016.1260038

52. Creswell, JW, and Poth, CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications (2016).

53. Merriam, SB. qualitative research and case study applications in education revised and expanded from case study research in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers (1998).

54. Yin, RK. Designing case studies In: L Maruster and MJ Gijsenberg, editors. Qualitative Research Method. Thousand oaks, CA: Sage Publications (2003)

56. Karaca, S, and Eren, N. The use of creative art as a strategy for case formulation in psychotherapy: a case study. J Clinical Art Ther. (2014) 2 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jcat/vol2/iss1/3/

57. Sperry, L, and Sperry, JJ. Case conceptualization: mastering this competency with ease and confidence. New York, NY: Routledge (2020).

58. American Psychological Association. Presidential task force on evidence-based practice in psychology. Am Psychol. (2006) 61:271–5. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271

59. Hill, CE. Therapist techniques, client involvement, and the therapeutic relationship: inextricably intertwined in the therapy process. Psychother: Theor Res Pract Train. (2005) 42:431–2. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.42.4.431

60. Yalom, ID, and Leszcz, M. The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic books (2008).

62. Patton, MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications (2014).

63. Kvale, S. Interview: an introduction to qualitive research interviewing In: K Shin, editor. Thousaand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications (1994)

64. Merriam, SB, and Tisdell, EJ. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Vancouver, BC: Langara College (2017).

65. Yin, RK. Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE (2018).

68. Art Therapy Credentials Board (ATCB). Code OF ethics, conduct, and disciplinary procedures. (2021). Available at: https://www.atcb.org/ethics/ (accessed November 2, 2022).

69. Korean Art Therapy Association (KATA) code of ethics. (2020). Available at: http://www.korean-arttherapy.or.kr/index/s4/s4_6.php (accessed February 12, 2020).

70. Schmidt, LAJ, and DeSchryver, M. The role of digital application literacy in online assessment. J Educ Technol Sys. (2021) 50:356–8. doi: 10.1177/00472395211052644

72. Chung, YJ. The study of therapeutic art education for children with disabilities. J Emot Behav Disord. (2006) 22:239–62.

73. Parker-Bell, B. Embracing a future with computers and art therapy. Art Ther. (1999) 16:180–5. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1999.10129482

74. Canter, DS. Art therapy and computers In: H Wadeson, J Durkin, and D Pearch, editors. Advances in art therapy. Hoboken, NJ: A Wiley-Interscience Publication (1989). 296–316.

75. Jamerson, JL. Expressive remix therapy: using digital media art in therapeutic group sessions with children and adolescents. Creat Nurs. (2013) 19:182–8. doi: 10.1891/1078-4535.19.4.182

76. Orr, P. Art therapy and digital media In: DE Gussak and ML Rosal, editors. The Wiley Handbook of Art Therapy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. (2015).

77. Mattson, DC. Usability assessment of a mobile app for art therapy. Arts Psychother. (2015) 43:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2015.02.005

78. Landgarten, HB. Magazine photo collage: A multicultural assessment and treatment technique. New York: Routledge (2017).

79. De Mèredieu, F. Arts et nouvelles technologies: art vidéo, art numérique. Paris: Larousse (2005).

80. Huizinga, J. Homo Ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. New York, NY: Routledge (2014).

82. Tilly, L. Afraid to leave the house: issues leading to social exclusion and loneliness for people with a learning disability. Tizard Learn Disabil Rev. (2019) 24:168–5. doi: 10.1108/tldr-02-2019-0005

83. Austin, BD. Renewing the debate: digital technology in art therapy and the creative process. Art Ther. (2009) 26:83–5. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2009.10129745

84. González-Zamar, M-D, Abad-Segura, E, Luque de la Rosa, A, and López-Meneses, E. Digital education and artistic-visual learning in flexible university environments: research analysis. Educ Sci. (2020) 10:294. doi: 10.3390/educsci10110294

85. Makransky, G, and Mayer, RE. Benefits of taking a virtual field trip in immersive virtual reality: evidence for the immersion principle in multimedia learning. Educ Psychol Rev. (2022) 34:1771–98. doi: 10.1007/s10648-022-09675-4

86. Lee, MY. A study on media characteristics of digital images and their therapeutic implications. Artistic Psychother Res. (2016) 12:61–85.

87. Ha, EK. A study on the structure of spatial experience by digital media. Proc Korean Soc Spatial Des. (2012) 20:9–18.

88. Han, JY. A research of the therapeutic applications of digital interactivity. Korean Soc Media Arts. (2016) 14:57–72.

89. Cermak-Sassenrath, D “Playful computer interaction.” In: V. Frissen, S. Lammes, M. Langede, J. Langede, and J. Raessens, eds Playful identities. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press (2015).

90. Katzeff, C Capturing playfulness in the design of digital learning environments for adults. (2003). Available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=53c40197b3c3a5e743355bedb8055428f4fca75e (accessed November 2, 2022).

91. Hall, K. Stop motion art therapy In: R Garner, editor. Digital art therapy: Material, methods, and applications. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers (2016)

92. Han, JY. Theoretical study and art therapeutic application of digital interactivity. Korean J Anim. (2017) 13:84–6.

93. Hawkins, RP, Han, J-Y, Pingree, S, Shaw, BR, Baker, TB, and Roberts, LJ. Interactivity and presence of three eHealth interventions. Comput Hum Behav. (2010) 26:1081–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.011

94. Carlton, N, Sit, T, and Yu, DR. Transcending media: tangible to digital and their mixed reality In: R Carolan and A Backos, editors. Emerging perspectives in art therapy. New York, NY: Routledge (2017)

95. Na, EY. Human communication and media: Expansion of the communication space. Seoul: Han Na-rae (2015).

96. McLuhan, M, and Gorden, WT. Understanding media: the extensions of man. Berkeley, CA: Ginko Press (2011).

97. Carolan, R, and Backos, A. Emerging perspectives in art therapy: trends, movements, and developments. New York, NY: Routledge (2017).

98. Wehmeyer, ML, and Metzler, CA. How self-determined are people with mental retardation? Natl Consum Surv Ment Retard. (1995) 33:111–9.

99. Ehinger, J. Therapeutic technology re-envisioned In: R Garner, editor. Digital art therapy: Material, methods, and applications. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers (2016)

Keywords: group art therapy, digital media, intellectual disabilities, adolescents, case study

Citation: Kim J and Chung YJ (2023) A case study of group art therapy using digital media for adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1172079. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1172079

Edited by:

Luis Manuel Mota de Sousa, Universidade Atlântica, PortugalReviewed by:

Fernanda Loureiro, Egas Moniz Interdisciplinary Research Center, PortugalIsabel De Jesus Oliveira, Superior School of Health North of the Portuguese Red Cross, Portugal

Maria Valle Ramirez-Duran, University of Extremadura, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Kim and Chung. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yeo Ju Chung, Y2h1bmc0NTU4QGNoYS5hYy5rcg==

Jinkyung Kim

Jinkyung Kim Yeo Ju Chung

Yeo Ju Chung