94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry, 26 April 2023

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1156313

This article is part of the Research TopicNew evidence on the Psychological Impacts and Consequences of Covid-19 on Mental Workload Healthcare Workers in Diverse Regions in the WorldView all 21 articles

Zhengshan Qin1†

Zhengshan Qin1† Zhehao He2†

Zhehao He2† Qinglin Yang1

Qinglin Yang1 Zeyu Meng1

Zeyu Meng1 Qiuhui Lei2

Qiuhui Lei2 Jing Wen3

Jing Wen3 Xiuquan Shi4

Xiuquan Shi4 Jun Liu1*

Jun Liu1* Zhizhong Wang2,5*

Zhizhong Wang2,5*Background: Persistently increased workload and stress occurred in health professionals (HPs) during the past 3 years as the COVID-19 pandemic continued. The current study seeks to explore the prevalence of and correlators of HPs' burnout during different stages of the pandemic.

Methods: Three repeated online studies were conducted in different stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: wave 1: after the first peak of the pandemic, wave 2: the early period of the zero-COVID policy, and wave 3: the second peak of the pandemic in China. Two dimensions of burnout, emotional exhaustion (EE) and declined personal accomplishment (DPA), were assessed using Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSMP), a 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and a 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) to assess mental health conditions. An unconditional logistic regression model was employed to discern the correlators.

Results: There was an overall prevalence of depression (34.9%), anxiety (22.5%), EE (44.6%), and DPA (36.5%) in the participants; the highest prevalence of EE and DPA was discovered in the first wave (47.4% and 36.5%, respectively), then the second wave (44.9% and 34.0%), and the third wave had the lowest prevalence of 42.3% and 32.2%. Depressive symptoms and anxiety were persistently correlated with a higher prevalence risk of both EE and DPA. Workplace violence led to a higher prevalence risk of EE (wave 1: OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.16–1.63), and women (wave 1: OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.00–1.42; wave 3: OR =1.20, 95% CI:1.01–1.44) and those living in a central area (wave 2: OR = 1.66, 95% CI: 1.20–2.31) or west area (wave 2: OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.26–1.87) also had a higher prevalence risk of EE. In contrast, those over 50 years of age (wave 1: OR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.39–0.96; wave 3: OR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.38–0.95) and who provided care to patients with COVID-19 (wave 2: OR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.57–0.92) had a lower risk of EE. Working in the psychiatry section (wave 1: OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.01–1.89) and being minorities (wave 2: OR = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.04–1.58) had a higher risk of DPA, while those over 50 years of age had a lower risk of DPA (wave 3: OR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.36–0.88).

Conclusion: This three-wave cross-sectional study revealed that the prevalence of burnout among health professionals was at a high level persistently during the different stages of the pandemic. The results suggest that functional impairment prevention resources and programs may be inadequate and, as such, continuous monitoring of these variables could provide evidence for developing optimal strategies for saving human resources in the coming post-pandemic era.

Burnout is characterized by emotional and mental exhaustion due to long-term workplace stress and negative job perception and is officially classified as an occupational health syndrome in the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) (1). Conceptionally, it consists of three interrelated dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and declined personal accomplishment (DPA) (2, 3). EE manifests through the loss of enthusiasm for work, feeling helpless, trapped, and defeated; DP is the negative response to other people; DPA refers to inefficiency or the lack of personal achievement (4). Heavy psychological burdens among health professionals (HPs) during outbreaks of SARS-CoV-1, H1N1, MERS-CoV, or Ebola have been reported (5). The prolonged duration of the COVID-19 pandemic has placed unprecedented pressure on HPs who directly participated in procedures including the diagnosis, treatment, and care of patients with COVID-19 (6, 7). It was reported that more than half of HPs had high-stress levels and poor work–family balance during the COVID-19 pandemic (8). Systematic reviews reflected the increase in the prevalence of psychological distress, insomnia, anxiety, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among health professionals during the current pandemic (7). Several studies have investigated the prevalence of burnout and associated factors among HPs (9–12). A study reported that over one-third of the HPs experienced severe burnout symptoms during the early stage of the pandemic in China (13). It reported age, family income, daily working hours, workload, insufficient protection working in a high-quality hospital, having more years of work experience, having more night shifts and fewer paid vacation days, etc. were associated with burnout among HPs during the pandemic in China (14–16). Although studies observed a positive association between workplace violence and burnout (17, 18), no study reported whether workplace violence affected burnout differently during COVID-19 in China. In brief, most of those studies were conducted at the early stage of the pandemic. It is unclear whether the stressful impact persisted as the pandemic continued.

Although strenuous efforts have been made to control the pandemic worldwide, the situation had no signs of improving until early 2022 (19). In the past 3 years, China adopted lockdown, zero-COVID strategy, and prolonged anti-pandemic measures to fight COVID-19 (20). However, until now, no large studies have been conducted to consistently investigate different phases of the pandemic in burnout among health professionals, as well as modifiable correlators and mitigators of it in mainland China. Moreover, there have been no targeted recommendations put forward for organizations to develop human resource-saving programs and preparedness for future spikes. However, prior research has highlighted emotional exhaustion (EE) as the most sensitive dimension of burnout, with high levels of EE being associated with DP and DPA (20–22). Some studies have suggested that the original three-factor model of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) can be replaced with one- or two-factor models (23). Hence, we extracted the items of EE and DPA from the MBI in the present investigation to enhance the robustness and feasibility.

Therefore, with the two dimensions of EE and DPA, the current research monitored burnout changes in prevalence and correlators among HPs during the three different stages of the pandemic through a three-wave cross-sectional study.

This study included three repeated online surveys. The first wave of the survey was proceeded 1 month after the first peak of the pandemic in China (27 March and 26 April 2020). The second wave survey was repeated between 27 March and 26 April 2021, when the zero-COVID policy and regular epidemic prevention and control rules were applied nationally. The third wave survey was repeated between 1 April and 30 April 2022, when the second peak of the pandemic happened in China.

This online survey was developed following the guidelines of the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (12). Individuals who served as physicians, nurses, or medical technicians in any hospitals in mainland China were included. The exclusion criteria were those who were absent from their position for more than 6 months in the past year, cannot access the Internet for any reason, or were unlicensed practitioners. The potentially qualified HPs were invited to join the study through several ways, including social media platforms, such as WeChat, Tencent QQ, and Sina Weibo (tweet in China). Those who responded to the invitation were encouraged to forward the questionnaire link to their colleagues and post it on their own social media networks. Second, an invitation letter was sent to an email list generated by the medical journal association when the email addresses were published with the article.

A total of 51,685 potential participants received the invitation to participate (Figure 1). Of them, 12,411 responded and completed the online questionnaire (a response rate of 24.0% in total; 20.2%, 25.1%, and 27.4% in wave 1, wave 2, and wave 3, respectively). Finally, 2,023 participants were excluded during the data cleaning process due to missing values, being identified as non-health professionals, having less than 2 years of practice, and so on, resulting in a sample of 10,388 participants in the analysis.

The survey was conducted on “Wenjuanxin”, an online survey solution provider. The survey link was compatible with multiple devices (including smartphones, laptops, and computers). The survey was anonymous, and online informed consent was acquired by asking participants to tick a box on the device screen. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Ningxia Medical University (approval #2020-112).

Sociodemographic data were collected and included the following variables: age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, ethnicity (Han vs. minorities), ICU/emergency room, physicians/nurses, length of practice, and whether they were direct care providers for patients with COVID-19.

Two dimensions of burnout were assessed using a modified version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSMP) (24). As mentioned earlier, we focused on EE and DPA in order to bring more psychometrical robustness and increased feasibility to the present study. Items were scored on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 6 (daily), and summed to total scores—higher scores indicate a higher level of burnout. The MBI-HSMP has been shown to have a good validity in HPs previously (25). Cronbach's alpha for this sample was 0.85.

Mental health conditions were assessed by the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for depressive symptoms and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) for anxiety. The Chinese version of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales have excellent psychometrical properties in medical patients (26, 27). Each item on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 is rated on a 4-point scale indicating the frequency of each symptom in the past 2 weeks, on a scale of 0 (none at all) to 3 (almost daily) (28). We categorized the depressive symptoms as dichotomies depending on the overall score ≥10 and the same with anxiety. Cronbach's alpha in the present sample was 0.91 for PHQ-9 (26) and 0.94 for GAD-7 (27).

Workplace violence (WPV) including the experience of WPV and witnessing WPV was measured using the Chinese version of the Workplace Violence Scale, a scale with proven good reliability and validity to measure violence including physical, mental, and verbal violence that was experienced in the past 12 months (29). The survey provided specific definitions of each type of violence. The individuals who reported any type of violence at least once were defined as violence positive (yes).

The mean replacement method was used to replace missing values of sociodemographic variables. We substituted the average of items answered on the scale for the score of missing items when computing scale scores. Those records were deleted when the missing value was more than two items for specific scales and no substitutions were made.

Descriptive statistics were performed by calculating means, standard deviations (SD), and proportions. The chi-square test was employed to test the prevalence of burnout, depression, and anxiety between categorical variables. An unconditional logistic regression model was used to identify the correlators of EE and DPA in different stages of the pandemic. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated under IBM SPSS 23.0. The alpha level was 0.05, with a two-tailed test.

The average age of participants was 35.5 (SD = 8.1) years with a range of 20 to 60 years (In China, a technical secondary nurse can have 2 years of experience at 20 years of age). The average length of practice was 11.0 years (SD = 8.4), ranging from 2 to 40 years. The overall prevalence of depression was 34.9%, and the prevalence of anxiety was 22.5%. As shown in Table 1, the prevalence of EE was 44.6% (4,636/ 10,388), the highest prevalence of EE was found in the first wave (47.4%, 1,425/ 3,006) and then the second wave (44.9%, 1,556/ 3,465), and the third wave had the lowest prevalence of 42.3% (1,655/ 3,917). Those who were aged < 40 years, living in the central areas of China, unmarried, and with a master's degree, and those with a length of practice of < 5 years had a higher prevalence of EE. Similarly, those who work in ICUs or emergency rooms had a higher prevalence of EE (P < 0.001), except in wave 1, while those who played a role in psychiatry and nurses had a lower prevalence than other HPs. No statistical significance of the prevalence of EE was found between those directly providing healthcare to patients with COVID-19 and others. Health professionals who reported medical errors, workplace violence, and witnessing workplace violence had a higher prevalence of EE (P < 0.001). Furthermore, those with depressive symptoms and anxiety had a much higher prevalence of EE.

As shown in Table 2, the overall prevalence of DPA was 34.0% (3,528/ 10,388); the highest prevalence of DPA was found in the first wave (36.5%, 1,098/ 3,006) and then the second wave (34.0%, 1,178/ 3,465), and the third wave had the lowest prevalence of 32.2% (1,252/ 3,917). Similar correlators were found for the prevalence of declined personal accomplishment. In contrast with EE, those with a bachelor's degree and minorities had a higher prevalence of declined personal accomplishment (P < 0.05).

As shown in Figure 2, slight heterogeneity among the three separate samples was identified in the correlators of burnout. In wave 1 and wave 3 samples, the logistic regression model revealed ages over 50 years had a lower prevalence risk of EE (wave 1: OR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.39–0.96; wave 3: OR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.38–0.95). Women had a higher prevalence risk (wave 1: OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.00–1.42; wave 3: OR =1.20, 95% CI: 1.01–1.44). In the wave 2 sample, the logistic regression model revealed that living in the central areas (OR = 1.66., 95% CI: 1.20–2.31) and west areas (OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.26–1.87) had a higher prevalence risk of EE. Health professionals who directly provide care to patients with COVID-19 had a lower prevalence risk of EE (OR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.57–0.92). Furthermore, workplace violence led to a higher risk of EE (wave 1: OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.16–1.63). Holding a master's degree, depression, and anxiety persistently correlated with a higher risk of EE in all three samples.

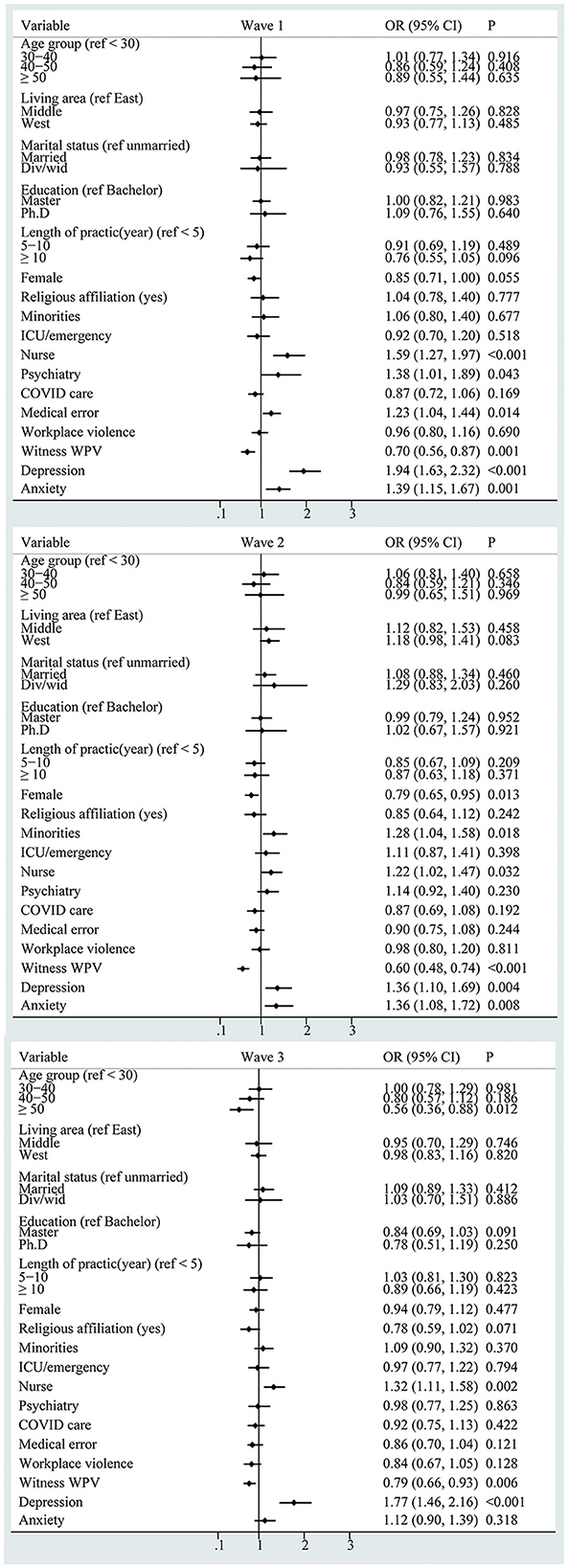

The correlators of DPA are shown in Figure 3. Working in the psychiatry section had a higher risk of DPA (OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.01–1.89) in wave 1, minorities had a higher risk of DPA (OR = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.04–1.58) in wave 2, and being aged over 50 years had a lower risk of DPA (OR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.36–0.88) in wave 3. Overall, being a nurse, depression, and anxiety persistently correlated with a higher risk of DPA in all three samples.

Figure 3. Forest plot of the correlators of declined personal accomplishment (WPV: workplace violence).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the workload and work stress of health professionals increased dramatically (30). Burnout as a key indicator of functional impairment has been reported repeatedly in the past 3 years (30, 31). To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies that monitored this functional impairment during three stages of COVID-19 among Chinese HPs. This study found high levels of EE and DPA among health professionals during three different stages of the pandemic. There are several possible explanations for the increased risk of burnout. First, the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, the lack of resources, and the rapidly increasing cases overloaded health professionals, leading to an increased risk of burnout. Second, 1 year after the pandemic, uncertainty around available resources and the evolution of the virus variants continued to challenge the health system (32). At this stage, strict restrictive measures were adopted in line with the zero-COVID policy (33). Health professionals experienced acute staffing shortages due to the huge efforts on the citywide test-trace-isolate, and following energy-exhausting protocols intended to keep everyone safe (34). In addition, people's daily lives had been disrupted by the long-term control measures against virus spreading, health professionals who had endured emotional and physical exhaustion for more than 2 years, and pandemic fatigue arose at this stage (35).

Adverse mental health outcomes surged during the pandemic (36), leading to functional impairment like burnout. We found that participants with depressive symptoms and anxiety had a higher prevalence of burnout (both EE and DPA) during the different stages of the pandemic. These results are consistent with the findings of other studies. A study conducted in France found a correlation between depression and EE (37). First, burnout and anxiety or depression were mutually influencing, representing that HPs suffering from burnout had a higher level of anxiety or depression, with a remarkable positive correlation between them, and vice versa (1, 38). COVID-19, as a source of stress, inevitably caused anxiety and depression among HPs, leading to their increased risk of EE and DPA, while no association of depression and anxiety was found with DPA in Piedmont's study (39), which in our view might be considered to be influenced by COVID-19 that huge failure in duty by failing to treat patients cause anxiety and depression.

There was an increase in reports of workplace violence attacks against HPs, especially in the early stage of the pandemic. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported 611 incidents of COVID-19-related workplace violence in more than 40 countries during the first 6 months of the pandemic (40). Other studies also found an increase in workplace violence against HPs during the COVID-19 pandemic (41, 42). In the present study, the prevalence of workplace violence was at a high level and was 64.2%, 53.2%, and 50.5% for wave 1, wave 2, and wave 3, respectively. A previous study found that workplace violence against health professionals decreased as the pandemic continued in mainland China (29). Studies have found that workplace violence triggered burnout among HPs (29, 43). Saifur also found workplace violence-exposed nurses were at a greater risk of burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic (44). We also observed a positive association between workplace violence and burnout.

Workplace violence may pose a threat to the life, safety, and dignity of HPs, deteriorating mental health (18). In addition, many studies have also indicated that workplace violence is related to a series of mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety (45, 46), which are relevant to burnout. While no statistical correlation was found in samples of wave 2 and wave 3, not surprisingly, varied correlators were identified in different waves due to the decreased possible exposure in different stages.

However, it was worth noting that the experience of witnessing workplace violence negatively correlated with DPA in all three samples. While several studies conducted among teachers have suggested that witnessing workplace violence is associated with both EE and DPA positively (47–49), differences between teachers and healthcare workers have emerged. Even though experiencing or witnessing workplace violence was prevalent among teachers and healthcare workers (47, 50), workplace violence was mostly perpetrated by students and their parents in the former group (48), whereas in the latter group, most violence was perpetrated by patients or patients' families (50). Furthermore, it should be noted that witnessing workplace violence physically or emotionally, which has not been distinguished in our study, could have a different psychological impact on healthcare workers which indicates that emotional workplace violence could be accepted or normalized by nurses (51). Moreover, a study administered at a medical center found no significant association of ever witnessed workplace violence with burnout (52), indicating that witnessing workplace violence, as an indirect experience where sufferers do not physically get hurt, may have less impact on mental health than experiencing it directly (53).

Those over 50 years old were less likely to suffer from burnout (both EE and DPA), and the reasonable explanation may be senior HPs with extensive experience are more competent in their duties and are likely to receive more respect and adequate rewards while experiencing fewer role conflicts. Furthermore, they are more likely to successfully pace their work, relieve stress, and minimize the risk of job burnout (54). In addition, consistent with many research results (55–59), women showed a higher prevalence risk of EE. Generally, women spent more time on their housework and children than men (60). Moreover, several studies indicated that female HPs were more likely to report having a part-time job (61), and they were more likely to suffer work–family conflict leading to mental problems (62). Additionally, the pressure of HPs increased sharply during the prevalence of COVID-19 (30). Chalhub RÁ (58) and Pappa S (63) reported that female HPs had a higher risk of psychological distress and sleep disruption under stressful situations. This is also true for Chinese female HPs during the current public health crisis (6). The combination of all these factors contributed to a higher level of stress in female HPs. Therefore, more care and support should be given to female HPs.

While, in the wave 2 sample, the logistic regression model revealed that living in central and western areas had a higher prevalence risk of EE, health professionals who directly provide care to patients with COVID-19 had a lower prevalence risk of EE. The pandemic has spread throughout the country since 2019 (62). However, due to the unequal distribution of medical resources, HPs in the central and western regions faced greater difficulties (64, 65). That may be the reason why HPs in central and western regions had a higher risk of EE. Compared with 2020 (the outbreak period of COVID-19) and 2022 (the re-explosion period), HPs involved in COVID-19 work had a higher job satisfaction because of the better control of the pandemic and the use of effective means in 2021. Compared with other professions, nurses were more likely to suffer from DPA (66, 67). For one thing, the shortage of HPs has been a global health system concern in recent years (68). Similar to other nations, China faced the challenge of a nurse resources shortage (17), which inevitably caused an overload of nurses and this problem was significantly magnified during the pandemic. For one thing, the increase in workload made nurses more prone to burnout (69). For another thing, nurses had more direct contact with patients in their daily work. The intensive patient–healthcare worker relationship in China has burdened the nurses with increased workload (68). Furthermore, nurses are overburdened by excessive demands and claim that their work is often stressful, leading to physical and mental exhaustion (70). As a result, some findings call for actions to strengthen communication and organizational support to increase the accomplishment of nurses (71, 72).

Several limitations exist in the present study. First, a consequence of the cross-sectional design is that it prevents causal inference; therefore, prospective studies are needed to identify predictors of burnout among health professionals. Second, the convenience sample here requires cautious generalization to service members in the whole nation and other areas outside of China. Third, other potential factors, including the type of hospital, social support, media publicity, and workloads, were not evaluated when exploring the correlators of burnout, which may lead to overestimation or underestimation of the differences between the three stages. Finally, the accuracy of self-reported measures cannot be guaranteed in cases where external factors may influence reporting (even though the survey was anonymous).

In conclusion, this three-wave cross-sectional study revealed the prevalence of burnout among health professionals at a high level persistently during the different stages of the pandemic. The correlators of burnout varied in dimensions and in stages of the pandemic. These results suggest that current health professionals' functional impairment prevention resources and programs may be inadequate. Considering the high level of uncertainty of the pandemic, continuous monitoring of these variables could provide evidence for developing optimal strategies for saving human resources in the coming post-pandemic era.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Committee of Ningxia Medical University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ZW and JL: conceptualization and methodology. ZW: data curation and project administration. ZQ and ZH: writing—original draft. JL, XS, and ZW: funding acquisition and writing–reviewing and editing. ZQ, QY, and ZM: formal analysis. JL, JW, and XS: data collection and visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This study was supported by funds for Ph.D. researchers of Guangdong Medical University in 2022 (Project number: GDMUB2022049, Recipient: ZW) and the China Medical Board (Project number: CMB16-254, Recipient: ZW).

The authors thank all the health workers who provided the information necessary for the completion of the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Tang L, Yu X-T, Wu Y-W, Zhao N, Liang R-L, Gao X-L, et al. Burnout, depression, anxiety and insomnia among medical staff during the COVID-19 epidemic in Shanghai. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1019635. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1019635

2. Ong AM-L. Outrunning burnout in a GI fellowship program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dig Dis Sci. (2020) 65:2161–3. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06401-4

3. Denning M, Goh ET, Tan B, Kanneganti A, Almonte M, Scott A, et al. Determinants of burnout and other aspects of psychological well-being in healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: a multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0238666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238666

4. Friganović A, Selič P, Ilić B, Sedić B. Stress and burnout syndrome and their associations with coping and job satisfaction in critical care nurses: a literature review. Psychiatr Danub. (2019) 31:21–31.

5. Danet A. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Western frontline healthcare professionals. A systematic review. Med Clin (Barc). (2021) 156:449–58. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2020.11.009

6. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Network Open. (2020) 3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

7. Chutiyami M, Cheong AMY, Salihu D, Bello UM, Ndwiga D, Maharaj R, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and overall mental health of healthcare professionals globally: a meta-review of systematic reviews. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:804525. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.804525

8. Mahgoub IM, Abdelrahman A, Abdallah TA, Mohamed Ahmed KAH, Omer MEA, Abdelrahman E, et al. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: perceived stress, anxiety, work-family imbalance, and coping strategies among healthcare professionals in Khartoum state hospitals, Sudan, 2021. Brain Behav. (2021) 11:e2318. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2318

9. Pinho R da NL, Costa TF, Silva NM, Barros-Areal AF, Salles A de M, Oliveira APRA, et al. High prevalence of burnout syndrome among medical and nonmedical residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. (2022) 17:e0267530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267530

10. Daryanto B, Putri FR, Kurniawan J, Ilmawan M, Fajar JK. The Prevalence and the associated sociodemographic-occupational factors of professional burnout among health professionals during COVID-19 pandemic in malang, indonesia: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:894946. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.894946

11. Li D, Wang Y, Yu H, Duan Z, Peng K, Wang N, et al. Occupational burnout among frontline health professionals in a high-risk area during the COVID-19 outbreak: a structural equation model. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:575005. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.575005

12. Elhadi YAM, Ahmed A, Salih EB, Abdelhamed OS, Ahmed MHH, El Dabbah NA, et al. cross-sectional survey of burnout in a sample of resident physicians in Sudan. PLoS ONE. (2022) 17:e0265098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265098

13. Huo L, Zhou Y, Li S, Ning Y, Zeng L, Liu Z, et al. Burnout and its relationship with depressive symptoms in medical staff during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:616369. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.616369

14. Hu Z, Wang H, Xie J, Zhang J, Li H, Liu S, et al. Burnout in ICU doctors and nurses in mainland China-a national cross-sectional study. J Crit Care. (2021) 62:265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.12.029

15. Zhang X, Wang J, Hao Y, Wu K, Jiao M, Liang L, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with burnout of frontline healthcare workers in fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from China. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:680614. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680614

16. Zhu H, Xie S, Liu X, Yang X, Zhou J. Influencing factors of burnout and its dimensions among mental health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Open. (2022) 9:2013–23. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1211

17. Liu W, Zhao S, Shi L, Zhang Z, Liu X, Li L, et al. Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e019525. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019525

18. Sui G, Liu G, Jia L, Wang L, Yang G. Associations of workplace violence and psychological capital with depressive symptoms and burn-out among doctors in Liaoning, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e024186. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024186

19. Wong S-C, Au AK-W, Lo JY-C, Ho P-L, Hung IF-N, To KK-W, et al. Evolution and control of COVID-19 epidemic in Hong Kong. Viruses. (2022) 14:2519. doi: 10.3390/v14112519

20. Su Z, Cheshmehzangi A, McDonnell D, Ahmad J, Šegalo S, Xiang Y-T, et al. The advantages of the zero-COVID-19 strategy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:8767. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19148767

21. Loera B, Converso D, Viotti S. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) among Italian nurses: how many factors must a researcher consider? PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e114987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114987

22. Aaa Edú-Valsania S, Laguía A, Moriano JA. Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. Int J Environm Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1780. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031780

23. Tavella G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Parker G. Burnout: Re-examining its key constructs. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 287:112917. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres

24. Kakemam E, Chegini Z, Rouhi A, Ahmadi F, Majidi S. Burnout and its relationship to self-reported quality of patient care and adverse events during COVID-19: A cross-sectional online survey among nurses. J Nurs Manag. (2021) 29:1974–82. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13359

25. Wang Z, Koenig HG, Tong Y, Wen J, Sui M, Liu H, et al. Moral injury in Chinese health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. (2022) 14:250–7. doi: 10.1037/tra0001026

26. Sun Y, Kong Z, Song Y, Liu J, Wang X. The validity and reliability of the PHQ-9 on screening of depression in neurology: a cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:98. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03661-w

27. Shih Y-C, Chou C-C, Lu Y-J, Yu H-Y. Reliability and validity of the traditional Chinese version of the GAD-7 in Taiwanese patients with epilepsy. J Formos Med Assoc. (2022) 121:2324–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2022.04.018

28. Zhizhong W, Koenig HG, Yan T, Jing W, Mu S, Hongyu L, et al. Psychometric properties of the moral injury symptom scale among Chinese health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:556. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02954-w

29. Qi M, Hu X, Liu J, Wen J, Hu X, Wang Z, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence and risk factors of workplace violence among healthcare workers in China. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:938423. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.938423

30. Zhang Y, Wang C, Pan W, Zheng J, Gao J, Huang X, et al. Stress, burnout, and coping strategies of frontline nurses during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan and Shanghai, China. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:565520. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565520

31. Jose S, Dhandapani M, Cyriac MC. Burnout and resilience among frontline nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in the emergency department of a tertiary care center, North India. Indian J Crit Care Med. (2020) 24:1081–8. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23667

32. Islam S, Islam T, Islam MR. New coronavirus variants are creating more challenges to global healthcare system: a brief report on the current knowledge. Clin Pathol. (2022) 15:2632010X221075584. doi: 10.1177/2632010X221075584

33. Lau SSS, Ho CCY, Pang RCK, Su S, Kwok H, Fung S-F, et al. Measurement of burnout during the prolonged pandemic in the Chinese zero-COVID context: COVID-19 burnout views scale. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1039450. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1039450

34. Huang Y-HC, Li J, Liu R, Liu Y. Go for zero tolerance: cultural values, trust, and acceptance of zero-COVID policy in two Chinese societies. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:1047486. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1047486

35. Pandemic Fatigue–PubMed,. (2022). Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34376086/ (accessed December 19, 2022).

36. Scott HR, Stevelink SAM, Gafoor R, Lamb D, Carr E, Bakolis I, et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and common mental disorders in health-care workers in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: a two-phase cross-sectional study. Lancet Psychiat. (2022) 10:40–49. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00375-3

37. Alwhaibi M, Alhawassi TM, Balkhi B, Al Aloola N, Almomen AA, Alhossan A, et al. Burnout and depressive symptoms in healthcare professionals: a cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare (Basel). (2022) 10:2447. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10122447

38. Chen J, Liu X, Wang D, Jin Y, He M, Ma Y, et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in healthcare workers deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2021) 56:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01954-1

39. Tan BYQ, Kanneganti A, Lim LJH, Tan M, Chua YX, Tan L, et al. Burnout and associated factors among health care workers in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2020) 21:1751–1758.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.035

40. ICRC: 600 violent incidents recorded against health care providers patients due to COVID-19. International Committee of the Red Cross. (2020). Available online at: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/icrc-600-violent-incidents-recorded-against-healthcare-providers-patients-due-covid-19 (accessed March 16, 2023).

41. Lafta R, Qusay N, Mary M, Burnham G. Violence against doctors in Iraq during the time of COVID-19. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0254401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254401

42. Elhadi YAM, Mohamed HMH, Ahmed A, Haroun IH, Hag MH, Farouk E, et al. Workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sudan: a cross-sectional study. Public Health Challenges. (2022) 1:e31. doi: 10.1002/puh2.31

43. Sun T, Gao L, Li F, Shi Y, Xie F, Wang J, et al. Workplace violence, psychological stress, sleep quality and subjective health in Chinese doctors: a large cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e017182. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017182

44. Chowdhury SR, Kabir H, Chowdhury MR, Hossain A. Workplace bullying and violence on burnout among bangladeshi registered nurses: a survey following a year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Public Health. (2022) 67:1604769. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1604769

45. Zhao S, Xie F, Wang J, Shi Y, Zhang S, Han X, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against chinese nurses and its association with mental health: a cross-sectional survey. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2018) 32:242–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.11.009

46. Chowdhury SR, Kabir H, Mazumder S, Akter N, Chowdhury MR, Hossain A. Workplace violence, bullying, burnout, job satisfaction and their correlation with depression among Bangladeshi nurses: A cross-sectional survey during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. (2022) 17:e0274965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274965

47. Ribeiro BM, dos SS, Martins JT, Moreira AAO, Galdino MJQ, Lourenço, et al. Association between burnout syndrome and workplace violence in teachers. Acta Paul Enferm. (2022) 35:eAPE01902. doi: 10.37689/acta-ape/2022AO01902

48. Chirico F, Capitanelli I, Bollo M, Ferrari G, Maran DA. Association between workplace violence and burnout syndrome among schoolteachers: a systematic review. J Health Social Sci. (2021) no. 2:187–208. doi: 10.19204/2021/ssct6

49. Moon B, McCluskey J. School-based victimization of teachers in korea: focusing on individual and school characteristics. J Interpers Violence. (2016) 31:1340–61. doi: 10.1177/0886260514564156

50. Aljohani B, Burkholder J, Tran QK, Chen C, Beisenova K, Pourmand A. Workplace violence in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. (2021) 196:186–97. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.009

51. Havaei F, MacPhee M. Effect of workplace violence and psychological stress responses on medical-surgical nurses' medication intake. Can J Nurs Res. (2021) 53:134–44. doi: 10.1177/0844562120903914

52. Okoli CTC, Seng S, Otachi JK, Higgins JT, Lawrence J, Lykins A, et al. A cross-sectional examination of factors associated with compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue across healthcare workers in an academic medical centre. Int J Mental Health Nurs. (2020) 29:476–87. doi: 10.1111/inm.12682

53. Havaei F. Does the type of exposure to workplace violence matter to nurses' mental health? Healthcare (Basel). (2021) 9:41. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9010041

54. Zhang S, Wang J, Xie F, Yin D, Shi Y, Zhang M, et al. A cross-sectional study of job burnout, psychological attachment, and the career calling of Chinese doctors. BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20:193. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4996-y

55. McPeek-Hinz E, Boazak M, Sexton JB, Adair KC, West V, Goldstein BA, et al. Clinician burnout associated with sex, clinician type, work culture, and use of electronic health records. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e215686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5686

56. Zhou T, Xu C, Wang C, Sha S, Wang Z, Zhou Y, et al. Burnout and wellbeing of healthcare workers in the post-pandemic period of COVID-19: a perspective from the job demands-resources model. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22:284. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07608-z

57. Chalhub RÁ, Menezes MS, Aguiar CVN, Santos-Lins LS, Netto EM, Brites C, et al. Anxiety, health-related quality of life, and symptoms of burnout in frontline physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Braz J Infect Dis. (2021) 25:101618. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2021.101618

58. Harry EM, Carlasare LE, Sinsky CA, Brown RL, Goelz E, Nankivil N, et al. Childcare stress, burnout, and intent to reduce hours or leave the job during the COVID-19 pandemic among us health care workers. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e2221776. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.21776

59. Prasad K, McLoughlin C, Stillman M, Poplau S, Goelz E, Taylor S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among US healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey study. EClinicalMedicine. (2021) 35:100879. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100879

60. Yang S, Liu D, Liu H, Zhang J, Duan Z. Relationship of work-family conflict, self-reported social support and job satisfaction to burnout syndrome among medical workers in southwest China: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0171679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171679

61. Marshall AL, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, Satele D, Trockel M, et al. Disparities in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in us physicians by gender and practice setting. Acad Med. (2020) 95:1435–43. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003521

62. Mo P, Xing Y, Xiao Y, Deng L, Zhao Q, Wang H, et al. Clinical characteristics of refractory coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 73:e4208–13. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa270

63. Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:901–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026

64. Van der Heijden B, Brown Mahoney C, Xu Y. Impact of job demands and resources on nurses' burnout and occupational turnover intention towards an age-moderated mediation model for the nursing profession. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2011. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16112011

65. Chai KC, Zhang YB, Chang KC. Regional disparity of medical resources and its effect on mortality rates in China. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:8. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00008

66. Hu D, Kong Y, Li W, Han Q, Zhang X, Zhu LX, et al. Frontline nurses' burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: A large-scale cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine. (2020) 24:100424. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100424

67. Matsuo T, Kobayashi D, Taki F, Sakamoto F, Uehara Y, Mori N, et al. Prevalence of health care worker burnout during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Japan. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2017271. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17271

68. Schlak AE, Poghosyan L, Liu J, Kueakomoldej S, Bilazarian A, Rosa WE, et al. The association between health professional shortage area (HPSA) status, work environment, and nurse practitioner burnout and job dissatisfaction. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2022) 33:998–1016. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2022.0077

69. Chen Y-C, Guo Y-LL, Chin W-S, Cheng N-Y, Ho J-J, Shiao JS-C. Patient-nurse ratio is related to nurses' intention to leave their job through mediating factors of burnout and job dissatisfaction. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4801. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16234801

70. Grochowska A, Gawron A, Bodys-Cupak I. Stress-inducing factors vs. the risk of occupational burnout in the work of nurses and paramedics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:5539. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095539

71. Soto-Rubio A, Giménez-Espert MDC, Prado-Gascó V. Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses' health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:7998. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217998

Keywords: mental health, COVID-19, cross-sectional study, health professionals, burnout

Citation: Qin Z, He Z, Yang Q, Meng Z, Lei Q, Wen J, Shi X, Liu J and Wang Z (2023) Prevalence and correlators of burnout among health professionals during different stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Front. Psychiatry 14:1156313. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1156313

Received: 01 February 2023; Accepted: 24 March 2023;

Published: 26 April 2023.

Edited by:

Krystyna Kowalczuk, Medical University of Bialystok, PolandReviewed by:

Yasir Ahmed Mohmmed Elhadi, Sudanese Medical Research Association, SudanCopyright © 2023 Qin, He, Yang, Meng, Lei, Wen, Shi, Liu and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jun Liu, bGl1anVuX3ptY0BzaW5hLmNvbQ==; Zhizhong Wang, d3poemhfbGlvbkAxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.