94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry, 12 May 2023

Sec. Psychological Therapy and Psychosomatics

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1149433

This article is part of the Research TopicClinical Guidelines in Eating Disorders: Applications and EvaluationView all 5 articles

Psychiatric comorbidity is the norm in the assessment and treatment of eating disorders (EDs), and traumatic events and lifetime PTSD are often major drivers of these challenging complexities. Given that trauma, PTSD, and psychiatric comorbidity significantly influence ED outcomes, it is imperative that these problems be appropriately addressed in ED practice guidelines. The presence of associated psychiatric comorbidity is noted in some but not all sets of existing guidelines, but they mostly do little to address the problem other than referring to independent guidelines for other disorders. This disconnect perpetuates a “silo effect,” in which each set of guidelines do not address the complexity of the other comorbidities. Although there are several published practice guidelines for the treatment of EDs, and likewise, there are several published practice guidelines for the treatment of PTSD, none of them specifically address ED + PTSD. The result is a lack of integration between ED and PTSD treatment providers, which often leads to fragmented, incomplete, uncoordinated and ineffective care of severely ill patients with ED + PTSD. This situation can inadvertently promote chronicity and multimorbidity and may be particularly relevant for patients treated in higher levels of care, where prevalence rates of concurrent PTSD reach as high as 50% with many more having subthreshold PTSD. Although there has been some progress in the recognition and treatment of ED + PTSD, recommendations for treating this common comorbidity remain undeveloped, particularly when there are other co-occurring psychiatric disorders, such as mood, anxiety, dissociative, substance use, impulse control, obsessive–compulsive, attention-deficit hyperactivity, and personality disorders, all of which may also be trauma-related. In this commentary, guidelines for assessing and treating patients with ED + PTSD and related comorbidity are critically reviewed. An integrated set of principles used in treatment planning of PTSD and trauma-related disorders is recommended in the context of intensive ED therapy. These principles and strategies are borrowed from several relevant evidence-based approaches. Evidence suggests that continuing with traditional single-disorder focused, sequential treatment models that do not prioritize integrated, trauma-focused treatment approaches are short-sighted and often inadvertently perpetuate this dangerous multimorbidity. Future ED practice guidelines would do well to address concurrent illness in more depth.

Scientific evidence for the association between trauma, PTSD and other trauma-related disorders in the predisposition, precipitation and perpetuation of eating disorders (EDs), has been established in a variety of samples, including treatment and non-treatment seeking individuals of various ages, genders and sexual orientations (1–6). The pooled lifetime prevalence rates of PTSD in EDs (ED + PTSD) in the highest quality studies average 25% with higher rates of 37–45% in bulimia nervosa (BN) and 21–26% in binge eating disorder (BED) (7–9). Lower prevalence rates are reported in association with AN, particularly the restricting type (10–14%). Nevertheless, higher rates of PTSD are reported in all ED patients admitted to residential care, especially those with BN, anorexia nervosa binge-purge type (AN-BP), and other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED) (2, 10, 11). Conversely, higher rates of EDs are also seen in patients with PTSD compared to the general population (8, 12).

It is common for ED + PTSD patients to report histories of multiple traumas and/or trauma types (1, 2, 10, 13). High trauma “doses” have been associated with ED severity and comorbidities (2, 13–16), and trauma histories and PTSD symptoms have been reported to predict more complicated courses of illness, higher dropout rates, and worse outcomes following treatment (11, 17–26). Evidence also suggests that individuals with ED + PTSD may be significantly more impulsive, prone to revictimization, and the subsequent perpetuation of PTSD (27–30), which apart from EDs tends to be a chronic disorder (31–33). Taken together, the development and adoption of integrated treatment approaches for ED + PTSD is warranted.

Existing guidelines for the treatment of EDs do not adequately address the problem of psychiatric comorbidity, which is more common than not in this group of disorders. Although admittedly this is a complicated topic, previously published ED guidelines often mention the entire issue of psychiatric comorbidity in a rather cursory manner and, if mentioned at all, do not address the depth of discussion or nuance that is often necessary to address ED + PTSD. In the excellent 2017 review of 8 existing guidelines for AN by Hilbert and colleagues, only 3 of these 8 manuscripts mentioned psychiatric comorbidities, while 5 of 9 guidelines for BN noted comorbidities, usually as “special issues” (34).

The issue of trauma and specifically of PTSD in the assessment of EDs was noted in the Australian and New Zealand guideline. These experts noted that psychiatric comorbidity occurs as high as 55% in community adolescent samples and up to 96% in adult samples, and they state, “Comorbidity in people with anorexia nervosa is common and therefore assessment for such should be routine” (35). They also make the recommendation to “be prepared to treat comorbidity to improve quality of life,” although no specifics as to how to do this are offered other than using CBT-E, which does not directly address trauma or PTSD, and considering adjunctive pharmacotherapy (35).

The updated German guidelines for the treatment of AN specifically noted, “many patients are affected by comorbid psychological diseases,” and that comorbid conditions, such as PTSD, “might require changes in treatment planning and prioritization of therapy goals,” although no specifics were provided (36).

More recently the American Psychiatric Association published an updated practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders, which notes that “eating disorders frequently co-occur with other psychiatric disorders” (37, 38). The guideline states that “all patients with a possible eating disorder should be asked about a history of trauma … and assessed for symptoms related to PTSD.” Although “data are…limited on individuals with eating disorders and…co-occurring psychiatric disorders,” the guideline recommends that psychotherapy in adults with AN “address comorbid psychopathology, psychological conflicts, adaptive benefits of symptoms, and family or cultural factors that reinforce or maintain eating disorder behaviors,” suggestions which are certainly applicable to the treatment of ED + PTSD in patients with any type of ED.

Notably, none of the guidelines for adult patients with EDs that were reviewed for this commentary specifically addressed treatment of ED + PTSD per se. However, in the newly published Australian guideline for the treatment of ED patients at higher weights, much more attention to trauma, PTSD, and trauma-informed care is paid (39). This is relevant given that ED patients with PTSD treated in higher levels of care have been reported to have significantly higher BMIs (2, 10, 40). Importantly, Ralph and colleagues offer lived experience perspectives, and specifically discuss trauma-informed care within an ED context for patients in larger bodies. They also acknowledge how ED treatment itself may be traumatizing and how PTSD and other comorbidities occur “frequently” (39).

Three published guidelines were found for the treatment of children and adolescents with EDs (41–43). The focus on psychiatric comorbidity was most prominent in the guideline from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, which states “further complicating the diagnosis of AN is the potential presence of other significant psychiatric comorbid conditions” (43). Abuse is noted to be a potential risk factor for BN, and PTSD an associated comorbid disorder in BN and BED, but no specific treatment guidelines for ED + PTSD are provided other than to recommend that “guidelines for the specific condition should be followed” and “The use of medications, including complementary and alternative medications, should be reserved for comorbid conditions and refractory cases.” The Canadian guideline for children and adolescents with EDs only mentions trauma and PTSD in reference to ARFID (41). However, it notes in the very last line of the guidelines the following statement: “Research efforts should be devoted to developing treatments for severe eating disorders with complex comorbidity.”

Conversely, upon reviewing available practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of PTSD or complex PTSD, the treatment of EDs is never addressed (44–54). The only PTSD guidelines that specifically mention EDs as an associated comorbidity are those of the American Psychiatric Association (55). Several guidelines specifically note that the presence of comorbid disorders should not prevent patients from receiving trauma-focused treatments (51, 52, 54, 56). However, in my experience trauma specialists are often unprepared to deal with PTSD patients with active ED symptoms. Unfortunately, it has been a common but unfortunate occurrence for ED + PTSD patients to be refused treatment in either an ED specialty program or trauma specialty program, or if they are admitted, only the so-called “primary” disorder (for insurance purposes) is treated. The treatment of one disorder to the exclusion of the other is often inadequate in that it all too often results in poor outcomes.

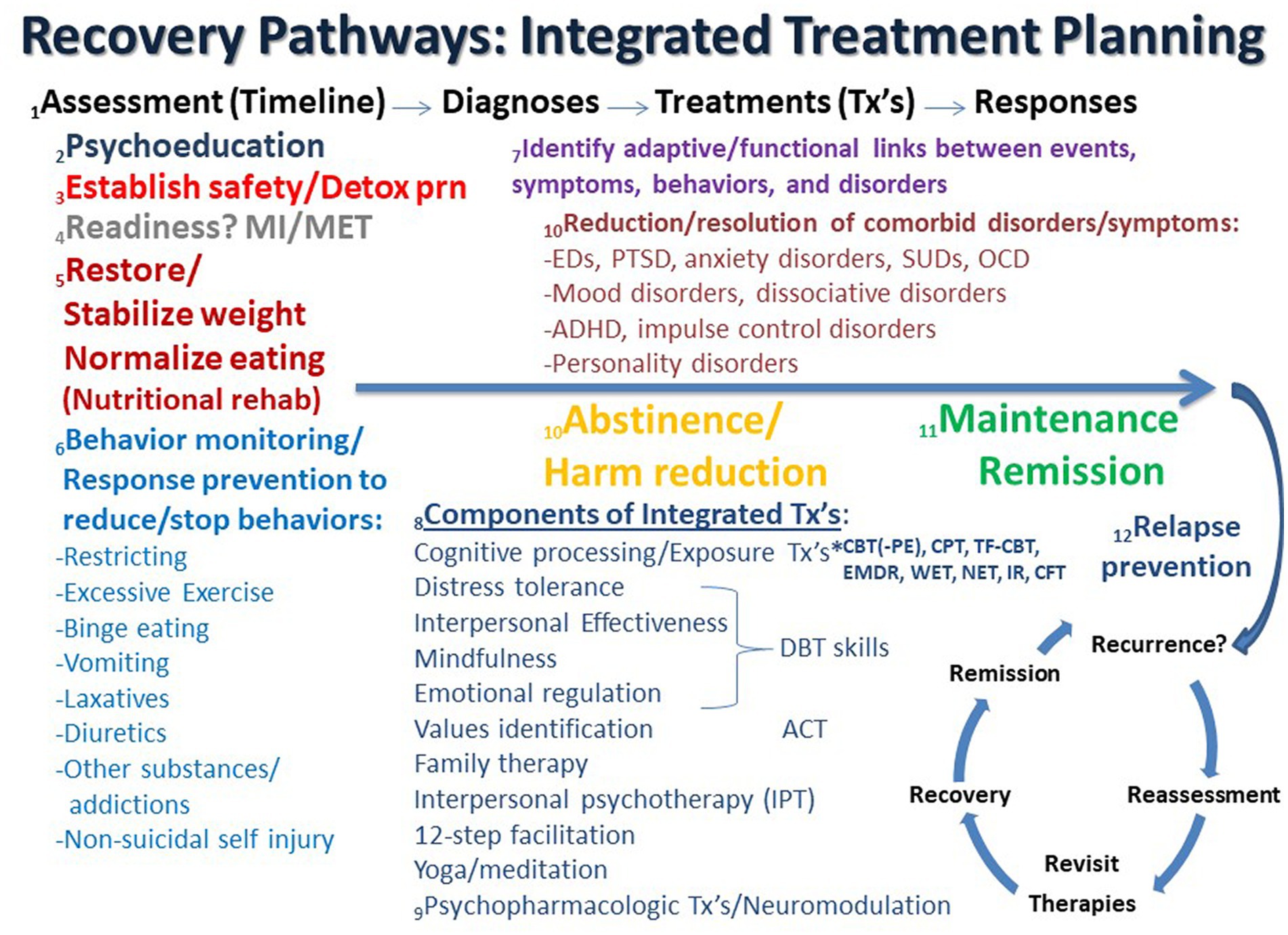

Recommendations regarding the treatment of ED + PTSD and related comorbidity have been previously outlined and discussed (1, 57, 58), and an updated, expanded conceptualization of these guidelines and principles is discussed here. Possible recovery pathways that may facilitate integrated treatment planning are shown in Figure 1. In the figure, the process starts on the left and proceeds in time to the right from Assessment (Timeline) to Diagnosis to Treatment (Tx) to Response as the patient ideally proceeds from highly symptomatic on the left to maintenance and/or remission on the far right, followed by relapse prevention and/or recurrence and reassessment.

Figure 1. Recovery pathways that facilitate integrated treatment planning are discussed consecutively in the text as numbered. ACT, acceptance commitment therapy; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CFT, compassion focused therapy; CPT, cognitive processing therapy; Detox, detoxification; DBT, dialectical behavior therapy; EMDR, eye movement desensitization reprocessing; IR, imaging rescripting; IPT, interpersonal psychotherapy; MI, motivational interviewing; MET, motivational enhancement therapy; NET, narrative exposure therapy; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; PE, prolonged exposure; SUD, substance use disorder; TF-CBT, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy; Tx’s, treatments; WET, written exposure therapy.

1. Assessment (Timeline) – Diagnosis: Most guidelines recognize the importance of “a comprehensive assessment of the individual and their circumstances” (35). It has been previously noted that “the most tried and true initial approach for any patient with or without complex symptomatology is to perform a complete psychiatric evaluation, which substantially reduces the chances of misdiagnosis” (57). This remains as important as ever, especially in an era in which time-limited evaluations are the norm in most treatment settings. Therefore, assessment is often an ongoing process that unfolds over several sessions. As part of this complete medical and psychiatric evaluation, the clinician and patient collaboratively develop a timeline that depicts the chronology of significant life events, traumas, symptom/disorder onsets, remissions, and relapses in the individual’s lifetime. Such a timeline can form the basis of the patient’s life narrative, including history of traumatic events and important contexts, and allows the patient and clinician to recognize and discuss predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating, and palliative factors in the patient’s life. Such an approach is compatible with the emerging paradigm of a life course approach as well as the concept of personalized medicine to address multimorbidity (59–63). It is important to note that the development of the patient’s historical timeline may occur over an extended period of time as therapy progresses and evolves (see #1 in Figure 1). Many ED patients do not feel comfortable revealing traumatic events during the initial assessment but need time to develop a trusting alliance with the therapist before such history is disclosed. The formation and maintenance of a therapeutic alliance remains a cornerstone of future work and progress (64, 65). Therapists need to convey a sense of safety, trust, honesty, straightforwardness, compassion, knowledge, and nonjudgmental positive regard, which are essential elements for any successful treatment course. Countertransference also needs to be closely monitored and contained (66–68). Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) emphasizes the importance of therapists avoiding avoidance of addressing traumatic material (69), as avoidance is highly characteristic of both EDs and PTSD (6, 11, 70–75). It has been previously noted that it is not uncommon for patients with ED + PTSD to not even realize that they have been victimized until the definitions of trauma and abuse types are explained to them (57). This is particularly relevant for patients with child maltreatment and complex PTSD. Only later after a substantial degree of cognitive development has occurred do some individuals realize the extent and meaning of their traumas.

2. Psychoeducation: As a comprehensive list of problems and conditions is being determined, the clinician moves forward educating the patient and supportive family about all diagnosed disorders, both current and lifetime. Psychoeducation is the cornerstone of all modern therapies, especially cognitive-behavioral and trauma-focused approaches (see #2 in Figure 1). Psychiatric disorders often vacillate in and out of remission, and previous disorders may serve as important predisposing factors for subsequent symptoms and disorders. Notably, comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception in PTSD and EDs (57, 76–78), and comorbid disorders are generally not contraindications to trauma-focused treatments (79, 80). Such treatments can be safely and effectively used in patients with a range of psychiatric disorders and are often associated with concurrent decreases in PTSD and the comorbid problem(s) (80–83).

3. Safety and stability: The most important determination and goal early on in treatment is to initially assess and address the greatest danger or risk to life, e.g., suicidality, self-harming behaviors, starvation, fluid/electrolyte disturbances, cardiac arrhythmia, etc. (see #3 in Figure 1). Attaining relative safety and stability is the foundation of stage 1 treatment of PTSD with complex presentations (complex PTSD), as well as dissociative disorders, which are highly linked to developmental traumas (46, 84–87). Given its pervasive association with problems in self-regulation, ED + PTSD with related comorbidities may be conceptualized as forms of complex PTSD (1, 88–90). Emerging behaviors that derail treatment progress, or therapy interfering behaviors (91–93), may need to be addressed as the therapist assists the patient to identify avoidance and work on stuck-points, cognitive distortions, or maladaptive beliefs (69). However, some trauma experts question the need for a phasic approach, arguing that there is a lack of research to support several contentions, including that: (1) a phase-based approach is necessary to attain positive outcomes, (2) trauma-focused treatments have unacceptable risks, and (3) response to trauma-focused treatments are improved when preceded by a stabilization phase (94). On the other hand, ISTSS guidelines indicate sufficient evidence and clinical rationale to support the phase-oriented approach with an initial period of stabilization and establishment of safety (46, 84, 95). Suicidality and other immediately life-threatening medical conditions are effectively the major primary contraindications against initiating trauma-focused treatment (79). When a substance use disorder (SUD) complicates the clinical picture, a detox strategy that is appropriate for the particular substance is an important early treatment component that is subsumed under the goal of establishing safety and stability.

4. Readiness for change: As assessment and treatment move forward, it is incumbent on therapists to identify readiness for change and willingness to engage in both PTSD and ED recovery, which are intimately interwoven (96–100). Motivational interviewing (MI) and motivation enhancement therapy (MET) approaches may help to identify the most problematic condition per the patient’s perspective and can be important prequels and/or adjuncts to other subsequent evidence-based therapies for EDs, PTSD and related comorbidities (101–108) (see #4 in Figure 1). However, it is notable that readiness for trauma-focused treatment is not always accurately assessed by therapists, which can lead to inadvertent collusion with avoidance (101).

5. Nutritional rehabilitation: Early on in treatment it is essential to establish that the patient has begun the process of nutritional rehabilitation, is more adherent to this plan than not (progress not perfection), is medically stable, and can begin to process information emotionally and cognitively (see #5 in Figure 1). New learning is dependent upon adequate food intake and subsequent protein and neurotransmitter synthesis (109–111). Ideally, effective psychotherapy requires grossly intact brain function, the ability to attend to the process at hand, and the ability and motivation to learn new information (and unlearn maladaptive strategies). Starved, intoxicated and/or severely dysregulated brains are unable to learn well and therefore are less likely to benefit from psychotherapy. Nevertheless, trauma-focused treatment should not be delayed until full weight restoration or remission of ED behaviors is achieved as long as the patient is safe and willing to engage in trauma processing. Evidence has been accumulating that the long-term resolution of ED symptoms may in fact hinge on trauma-focused treatment (4, 77, 112, 113).

6. Behavior monitoring and response prevention: Just as psychoeducation is an integral early component of cognitive behavioral therapies, so too is behavior monitoring and response prevention of problematic behaviors. Patients are asked to record instances and frequencies of targeted behaviors, including food intake and episodes of binge eating, purging, excessive exercise, substance use, and non-suicidal self-injury. This prescription is not only a part of ongoing assessment but is an effective treatment intervention in itself (see #6 in Figure 1). As treatment continues, the therapist periodically confirms that ED behaviors are being sufficiently addressed in an ongoing manner. Monitoring of ED and PTSD symptoms using validated measures, e.g., the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDEQ) (114) and the PTSD Symptom Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (115), respectively, are essential in assessing progress for the ED + PTSD patient, while an array of other assessments are available for other comorbidities. While full remission may remain elusive, it is helpful to frame various degrees of symptom improvement as evidence of progress and success. Combating perfectionistic, “all or nothing” thinking is often an ongoing process in the long-term treatment of ED + PTSD patients, and teaching and promoting the concept and goal of harm reduction is a useful endeavor that has application to multiple symptoms and disorders on the comorbidity spectrum (116–118).

7. Adaptive function: An important part of the therapeutic process is to collaboratively identify the relationships between life events, symptoms of PTSD, eating and other disorders, which may serve as adaptive functions, such as to facilitate avoidance and numbing, decrease hyperarousal, regulate trauma-related states (“self-medication hypothesis”) (119) or solve some perceived problem(s) (15). Certain ED behaviors may also be traumatic reenactments (120). “Building the bridge” between trauma-related/PTSD symptoms and ED behaviors/symptoms serves to foster new connections and meanings and paves the way toward sustained recovery (see #7 in Figure 1). Continued work on the patient’s timeline can facilitate ascertaining these connections. Establishing the interconnectedness of and bridging between symptoms is supported by recent network analyses of ED and PTSD symptoms (97, 99, 100).

8. Components of integrated treatment: psychotherapies: It is argued that an integrated trauma-focused treatment plan using a rational mixture of evidence-based techniques and tools is indicated. An overview of the psychotherapeutic components that may be considered in integrated treatment planning is shown in Figure 1 (see #8). The field has evolved beyond the “one size fits all” approach, which is woefully inadequate for the ED + PTSD patient. Generally, some form of trauma-focused treatment is indicated for PTSD, and this should be no different when there is ED comorbidity. The most researched of trauma-focuses approaches in this population is cognitive processing therapy (CPT), which arguably is very well-suited for ED + PTSD patients (29, 112, 113, 121–123). However, other trauma-focused therapies can be applied to ED + PTSD patients, including prolonged exposure (PE), eye movement desensitization reprocessing (EMDR), imaging rescripting (IR), written exposure therapy (WET), narrative exposure therapy (NET), compassion-focused therapy (CFT), and trauma-focused CBT (TFCBT) in children and adolescents (49, 71, 121, 124–142). Other adjunctive approaches, or elements of these approaches, can also be useful, including acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which identifies values and addresses experiential avoidance (143–146), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), which has been reported to be effective in EDs, PTSD, and major depression (145, 147–152), and 12-step facilitation, a manual based, therapist driven treatment based on 12-step principles found to be effective for alcohol use and stimulant use disorders (153–155). The unified treatment model has also been recommended for ED + PTSD (156). Self-administered emotional freedom techniques (EFT) have been successfully employed for PTSD, but have not been systematically explored in EDs (157). Family therapy with non-offending parents and/or guardians is an essential ingredient for children and adolescents with ED and PTSD, and it should be considered for all patients of any age (158, 159). Involving family members in assessment and treatment is often extremely helpful and can contribute to significant therapeutic advances. When patients are not amenable to involving family members it is important for therapists to understand why.

A sufficient level of distress tolerance and emotional regulation is required so that psychotherapy can proceed, although pauses and delays are likely to occur in the course of addressing patients with complex psychopathology. The use of DBT skills as grounding techniques to enhance self-regulation, mindfulness, distress tolerance and interpersonal effectiveness can be essential, powerful adjuncts to trauma-focused therapies for severely ill comorbid ED + PTSD patients (160, 161). Other grounding or anxiety reduction techniques, such as focused breathing, yoga and other meditation practices, can be utilized as evidence-based treatment adjuncts (162–172). However, a certain amount of emotionality is to be expected and should not in itself be a reason for delay. A central tenet of evidence-based trauma-focused treatment is for the therapist to “avoid avoidance” and to not collude with the patient’s tendency to deflect (69). Disengagement coping has been found to predict revictimization, while engagement coping predicts better outcomes (173).

9. Components of integrated treatment: psychopharmacology and neuromodulation: Psychopharmacological interventions are also effective evidence-based treatments for non-comorbid EDs, PTSD and related comorbid disorders, e.g., mood and anxiety disorders, but they should always be adjunctive to psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with ED + PTSD and related comorbidities (174–179) (see #9 in Figure 1). The agents that have been found to be beneficial in ED and PTSD samples separately generally include antidepressants, especially fluoxetine and other serotonin reuptake inhibitors, atypical antipsychotics, especially olanzapine, and anticonvulsants, especially topiramate (35, 180–199). In addition, naltrexone can be highly effective in reducing alcohol intake as well as combating non-suicidal self-injury and binge eating (200–210). Other novel approaches to consider, especially when treatment-refractory major depression is a focus, may include the use of newer psychopharmacologic agents, e.g., 5-HT4 receptor antagonists (211), combining other previously unused evidence-based psychotherapies and psychopharmacologic approaches (142, 212), adjunctive application of neuromodulation tools, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) (213, 214), deep TMS (215) or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (216), novel psychotropic-or psychedelic-assisted therapies, such as ketamine/esketamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), psilocybin, and ayahuasca (12, 28, 212, 217–231), as well as deep brain stimulation (DBS) (232–235), although many of these newer approaches continue to be preliminary, experimental and/or challenging to acquire.

10. Resolution, abstinence, and harm reduction: It is well known that improvement in one set of symptoms often results in the resolution of or improvement in related symptoms of other disorders, which exist in a network with each other (see #10 in Figure 1) (147, 236–238). For example, as ED symptoms abate with treatment so also can symptoms of disorders of mood, anxiety, personality, etc. (11, 112, 122, 239, 240). Similarly, abstinence from or a reduction in SUD behaviors often accompanies similar reductions in mood, anxiety and other comorbid symptoms (241, 242). Likewise, recovery from PTSD often results in improvements in a host of related psychological symptoms (243–245).

11. Maintenance, remission, and relapse prevention: As improvements continue and degrees of remission are achieved, patients may move into the maintenance phase of treatment (see #11 in Figure 1). It is during this phase that relapse prevention strategies can be successfully employed. Specific forms of CBT and pharmacotherapy focused on relapse prevention have been found to significantly reduce relapse for eating, substance use, mood and anxiety disorders (246–255).

12. Refractoriness and relapse: In the face of refractoriness to treatment, inadequate response, and/or relapse, which is common in EDs and related comorbidities (256–258), it is helpful for the patient and therapist to re-evaluate the treatment plan, identify triggers, stuck points, and potential weak points, and to revisit therapeutic options (see #12 in Figure 1). Experienced clinicians are familiar with the “whack-a-mole” phenomenon in which one or more problems resolve as others emerge. When the therapeutic skills of the therapist do not match the needs of the patient, then it is sometimes appropriate and in the best interests of the patient to discuss switching gears and referring to someone else with greater expertise, experience or skills. However, it is essential that hope continue to live eternal while the odds of attaining desired goals are evaluated. The lived experiences of patients with ED + PTSD, particularly those with severe and enduring eating disorders, should be carefully considered in light of what is and is not known about long-term outcome data (259–270). Despite the availability in some locations of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide for so-called “terminal anorexia,” it is my and others’ opinion that this course of action not be considered a possible option (263, 271–273), while palliative care may be indicated and considered (274). There are so many potential therapeutic options and combinations of options that one is hard pressed to argue that all avenues have been exhausted in the face of ED + PTSD chronicity and refractoriness.

In conclusion, effective treatment of ED + PTSD and related comorbidity requires the therapist to acquire many needed skills and resources, many of which are outlined in Figure 1 and discussed in this commentary. Abraham Maslow once said, “If all you have is a nail, then everything is a hammer.” Applying only one therapeutic approach to every ED patient is insufficient, a conclusion that is hopefully obvious at this juncture. Available clinical research evidence suggests that continuing with traditional single-disorder focused, sequential treatment models with multiple providers that do not prioritize integrated, trauma-focused treatment approaches are short-sighted and often inadvertently perpetuate this dangerous multimorbidity. Future ED practice guidelines would do well to address concurrent illness in more depth. Taken together, these principles offer the clinician a map for better negotiating a successful journey of recovery for the ED + PTSD comorbid patient. Recently published outcome data indicate that integrated treatment approaches can result in significant improvement in ED, PTSD and related symptoms (11, 12, 112, 122, 127, 156).

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

TB is the owner of Timothy D. Brewerton, MD, LLC.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Brewerton, TD. An overview of trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2018) 28:445–62. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1532940

2. Brewerton, TD, Perlman, MM, Gavidia, I, Suro, G, Genet, J, and Bunnell, DW. The association of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder with greater eating disorder and comorbid symptom severity in residential eating disorder treatment centers. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:2061–6. doi: 10.1002/eat.23401

3. Brewerton, TD, Suro, G, Gavidia, I, and Perlman, MM. Sexual and gender minority individuals report higher rates of lifetime traumas and current PTSD than cisgender heterosexual individuals admitted to residential eating disorder treatment. Eat Weight Disord. (2022) 27:813–20. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01222-4

4. Mitchell, KS, Scioli, ER, Galovski, T, Belfer, PL, and Cooper, Z. Posttraumatic stress disorder and eating disorders: maintaining mechanisms and treatment targets. Eat Disord. (2021) 29:292–306. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2020.1869369

5. Reyes-Rodriguez, ML, Von Holle, A, Ulman, TF, Thornton, LM, Klump, KL, Brandt, H, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in anorexia nervosa. Psychosom Med. (2011) 73:491–7. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31822232bb

6. Scharff, A, Ortiz, SN, Forrest, LN, and Smith, AR. Comparing the clinical presentation of eating disorder patients with and without trauma history and/or comorbid PTSD. Eat Disord. (2019) 29:88–102. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2019.1642035

7. Dansky, BS, Brewerton, TD, Kilpatrick, DG, and O'Neil, PM. The National Women's study: relationship of victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder to bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. (1997) 21:213–28. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199704)21:3<213::AID-EAT2>3.0.CO;2-N

8. Ferrell, EL, Russin, SE, and Flint, DD. Prevalence estimates of comorbid eating disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative synthesis. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2020) 31:264–82. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2020.1832168

9. Hudson, JI, Hiripi, E, Pope, HG Jr, and Kessler, RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. (2007) 61:348–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

10. Brewerton, TD, Gavidia, I, Suro, G, Perlman, MM, Genet, J, and Bunnell, DW. Provisional posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with greater severity of eating disorder and comorbid symptoms in adolescents treated in residential care. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2021) 29:910–23. doi: 10.1002/erv.2864

11. Scharff, A, Ortiz, SN, Forrest, LN, Smith, AR, and Boswell, JF. Post-traumatic stress disorder as a moderator of transdiagnostic, residential eating disorder treatment outcome trajectory. J Clin Psychol. (2021) 77:986–1003. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23106

12. Brewerton, TD, Wang, JB, Lafrance, A, Pamplin, C, Mithoefer, M, Yazar-Klosinki, B, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy significantly reduces eating disorder symptoms in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of adults with severe PTSD. J Psychiatr Res. (2022) 149:128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.03.008

13. Brewerton, TD, Perlman, MM, Gavidia, I, Suro, G, and Jahraus, J. Headache, eating disorders, PTSD, and comorbidity: implications for assessment and treatment. Eat Weight Disord. (2022) 27:2693–700. doi: 10.1007/s40519-022-01414-6

14. Afifi, TO, Sareen, J, Fortier, J, Taillieu, T, Turner, S, Cheung, K, et al. Child maltreatment and eating disorders among men and women in adulthood: results from a nationally representative United States sample. Int J Eat Disord. (2017) 50:1281–96. doi: 10.1002/eat.22783

15. Brewerton, T. D., and Dennis, A. B. (2015). Perpetuating factors in severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. In S. Touyz, P. Hay, D. GrangeLe, and J. H. Lacey (Eds.), Managing severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a clinician's handbook. New York, NY: Routledge.

16. Molendijk, ML, Hoek, HW, Brewerton, TD, and Elzinga, BM. Childhood maltreatment and eating disorder pathology: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Psychol Med. (2017) 47:1402–16. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716003561

17. Anderson, KP, LaPorte, DJ, Brandt, H, and Crawford, S. Sexual abuse and bulimia: response to inpatient treatment and preliminary outcome. J Psychiatr Res. (1997) 31:621–33. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3956(97)00026-5

18. Castellini, G, Lelli, L, Cassioli, E, Ciampi, E, Zamponi, F, Campone, B, et al. Different outcomes, psychopathological features, and comorbidities in patients with eating disorders reporting childhood abuse: a 3-year follow-up study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2018) 26:217–29. doi: 10.1002/erv.2586

19. Convertino, A. D., and Mendoza, R. R. (2023). Posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic events, and longitudinal eating disorder treatment outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord doi:doi: 10.1002/eat.23933 [Epub ahead of print]

20. Fallon, BA, Sadik, C, Saoud, JB, and Garfinkel, RS. Childhood abuse, family environment, and outcome in bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychiatry. (1994) 55:424–8.

21. Hazzard, VM, Crosby, RD, Crow, SJ, Engel, SG, Schaefer, LM, Brewerton, TD, et al. Treatment outcomes of psychotherapy for binge-eating disorder in a randomized controlled trial: examining the roles of childhood abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2021) 29:611–21. doi: 10.1002/erv.2823

22. Mahon, J, Bradley, SN, Harvey, PK, Winston, AP, and Palmer, RL. Childhood trauma has dose effect relationship with dropping out from psychotherapeutic treatment for bulimia nervosa: a replication. Int J Eat Disord. (2001) 30:138–48. doi: 10.1002/eat.1066

23. Rodriguez, M, Perez, V, and Garcia, Y. Impact of traumatic experiences and violent acts upon response to treatment of a sample of Colombian women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. (2005) 37:299–306. doi: 10.1002/eat.20091

24. Serra, R, Kiekens, G, Tarsitani, L, Vrieze, E, Bruffaerts, R, Loriedo, C, et al. The effect of trauma and dissociation on the outcome of cognitive behavioural therapy for binge eating disorder: a 6-month prospective study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2020) 28:309–17. doi: 10.1002/erv.2722

25. Trottier, K. Posttraumatic stress disorder predicts non-completion of day hospital treatment for bulimia nervosa and other specified feeding/eating disorder. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2020) 28:343–50. doi: 10.1002/erv.2723

26. Vrabel, KR, Hoffart, A, Ro, O, Martinsen, EW, and Rosenvinge, JH. Co-occurrence of avoidant personality disorder and child sexual abuse predicts poor outcome in long-standing eating disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. (2010) 119:623–9. doi: 10.1037/a0019857

27. Brewerton, TD, Cotton, BD, and Kilpatrick, DG. Sensation seeking, binge-type eating disorders, victimization, and PTSD in the National Women's study. Eat Behav. (2018) 30:120–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.07.001

28. Mitchell, JM, Bogenschutz, M, Lilienstein, A, Harrison, C, Kleiman, S, Parker-Guilbert, K, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med. (2021) 27:1025–33. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3

29. Mitchell, KS, Wells, SY, Mendes, A, and Resick, PA. Treatment improves symptoms shared by PTSD and disordered eating. J Trauma Stress. (2012) 25:535–42. doi: 10.1002/jts.21737

30. Vierling, V, Etori, S, Valenti, L, Lesage, M, Pigeyre, M, Dodin, V, et al. Prevalence and impact of post-traumatic stress disorder in a disordered eating population sample. Presse Med. (2015) 44:e341–52. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2015.04.039

31. Kessler, RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola, S, Alonso, J, Benjet, C, Bromet, EJ, Cardoso, G, et al. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2017) 8:1353383. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383

32. Kessler, RC, Sonnega, A, Bromet, E, Hughes, M, and Nelson, CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1995) 52:1048–60. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

33. Koenen, KC, Ratanatharathorn, A, Ng, L, McLaughlin, KA, Bromet, EJ, Stein, DJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychol Med. (2017) 47:2260–74. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000708

34. Hilbert, A, Hoek, HW, and Schmidt, R. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders: international comparison. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2017) 30:423–37. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000360

35. Hay, P, Chinn, D, Forbes, D, Madden, S, Newton, R, Sugenor, L, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2014) 48:977–1008. doi: 10.1177/0004867414555814

36. Resmark, G, Herpertz, S, Herpertz-Dahlmann, B, and Zeeck, A. Treatment of anorexia nervosa-new evidence-based guidelines. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:153. doi: 10.3390/jcm8020153

37. American Psychiatric Association (2023). The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

38. Crone, C, Fochtmann, LJ, Attia, E, Boland, R, Escobar, J, Fornari, V, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. (2023) 180:167–71. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.23180001

39. Ralph, AF, Brennan, L, Byrne, S, Caldwell, B, Farmer, J, Hart, LM, et al. Management of eating disorders for people with higher weight: clinical practice guideline. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:121. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00622-w

40. Longo, P, Marzola, E, De Bacco, C, Demarchi, M, and Abbate-Daga, G. Young patients with anorexia nervosa: the contribution of post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic events. Medicina. (2020) 34:665–74. doi: 10.3390/medicina57010002

41. Couturier, J, Isserlin, L, Norris, M, Spettigue, W, Brouwers, M, Kimber, M, et al. Canadian practice guidelines for the treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Eat Disord. (2020) 8:4. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-0277-8

42. Ebeling, H, Tapanainen, P, Joutsenoja, A, Koskinen, M, Morin-Papunen, L, Jarvi, L, et al. A practice guideline for treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Ann Med. (2003) 35:488–501. doi: 10.1080/07853890310000727

43. Lock, J, and La Via, MC, American Academy of, C., & Adolescent Psychiatry Committee on Quality, I. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2015) 54:412–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.018

44. Berliner, L., Bisson, J., Cloitre, M., Forbes, D., Goldbeck, L., Jensen, T. K., et al. (2017). ISTSS guidelines position paper on complex PTSD in children and adolescents, Oakbrook Terrace, IL: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies.

45. Bisson, JI, Berliner, L, Cloitre, M, Forbes, D, Jensen, TK, Lewis, C, et al. The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies new Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: methodology and development process. J Trauma Stress. (2019) 32:475–83. doi: 10.1002/jts.22421

46. Cloitre, M., Courtois, C. A., Ford, J. D., Green, B. L., Alexander, P., Briere, J., et al. (2012). ISTSS expert consensus guidelines for complex PTSD, Oakbrook Terrace, IL: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies.

47. Foa, EB, Keane, TM, Friedman, MJ, and Cohen, JA. Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Second ed New York, NY: The Guilford Press (2009).

48. Forbes, D, Creamer, M, Bisson, JI, Cohen, JA, Crow, BE, Foa, EB, et al. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and related conditions. J Trauma Stress. (2010) 23:537–52. doi: 10.1002/jts.20565

49. Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of PTSD in Adults, A. P. A. Summary of the clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Am Psychol. (2019) 74:596–607. doi: 10.1037/amp0000473

50. Lewis, C, Roberts, NP, Andrew, M, Starling, E, and Bisson, JI. Psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2020) 11:1729633. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1729633

51. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2018). Guideline for posttraumatic stress disorder. National Institute for Health and Clinical Practice.

52. Phelps, AJ, Lethbridge, R, Brennan, S, Bryant, RA, Burns, P, Cooper, JA, et al. Australian guidelines for the prevention and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: updates in the third edition. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2022) 56:230–47. doi: 10.1177/00048674211041917

53. The Expert Concensus Panels for PTSD. The expert consensus guideline series. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder PTSD. J Clin Psychiatry. (1999) 60:3–76.

54. The Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Work Group. (2017). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of post-traumatic stress and acute stress disorder. department of veterans affairs, department of defense. Available at: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal082917.pdf [Accessed January 18]

55. Ursano, RJ, Bell, C, Eth, S, Friedman, M, Norwood, A, Pfefferbaum, B, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2004) 161:3–31.

56. Hamblen, JL, Norman, SB, Sonis, JH, Phelps, AJ, Bisson, JI, Nunes, VD, et al. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: An update. Psychotherapy. (2019) 56:359–73. doi: 10.1037/pst0000231

57. Brewerton, TD. Eating disorders, victimization, and comorbidity: principles of treatment In: TD Brewerton, editor. Clinical handbook of eating disorders: an integrated approach : New York, NY: Marcel Decker (2004). 509–45.

58. Trim, JG, Galovski, T, Wagner, A, and Brewerton, TD. Treating eating disorder-PTSD patients: a synthesis of the literature and new treatment directions In: LK Anderson, SB Murray, and WH Kaye, editors. Clinical handbook of complex and atypical eating disorders : New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2017). 40–59.

59. Ben-Shlomo, Y, and Kuh, D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. (2002) 31:285–93. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.2.285

60. Fried, EI, and Cramer, AOJ. Moving forward: challenges and directions for psychopathological network theory and methodology. Perspect Psychol Sci. (2017) 12:999–1020. doi: 10.1177/1745691617705892

61. Fried, EI, van Borkulo, CD, Cramer, AO, Boschloo, L, Schoevers, RA, and Borsboom, D. Mental disorders as networks of problems: a review of recent insights. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2017) 52:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z

62. Kan, C, and Treasure, J. Recent research and personalized treatment of anorexia nervosa. Psychiatr Clin North Am. (2019) 42:11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2018.10.010

63. Kuh, D, Ben-Shlomo, Y, Lynch, J, Hallqvist, J, and Power, C. Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2003) 57:778–83. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.778

64. Olofsson, ME, Oddli, HW, Hoffart, A, Eielsen, HP, and Vrabel, KR. Change processes related to long-term outcomes in eating disorders with childhood trauma: An explorative qualitative study. J Couns Psychol. (2020) 67:51–65. doi: 10.1037/cou0000375

65. Olofsson, ME, Vrabel, KR, Hoffart, A, and Oddli, HW. Covert therapeutic micro-processes in non-recovered eating disorders with childhood trauma: an interpersonal process recall study. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:42. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00566-1

66. Cramer, MA. Under the influence of unconscious process: countertransference in the treatment of PTSD and substance abuse in women. Am J Psychother. (2002) 56:194–210. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2002.56.2.194

67. Satir, DA, Thompson-Brenner, H, Boisseau, CL, and Crisafulli, MA. Countertransference reactions to adolescents with eating disorders: relationships to clinician and patient factors. Int J Eat Disord. (2009) 42:511–21. doi: 10.1002/eat.20650

68. Thompson-Brenner, H, Satir, DA, Franko, DL, and Herzog, DB. Clinician reactions to patients with eating disorders: a review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. (2012) 63:73–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100050

69. Resick, PA, Monson, CM, and Chard, KM. Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual, New York, NY: The Guilford Press (2017).

70. Cavicchioli, M, Scalabrini, A, Northoff, G, Mucci, C, Ogliari, A, and Maffei, C. Dissociation and emotion regulation strategies: a meta-analytic review. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 143:370–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.011

71. Daneshvar, S, Shafiei, M, and Basharpoor, S. Group-based compassion-focused therapy on experiential avoidance, meaning-in-life, and sense of coherence in female survivors of intimate partner violence with PTSD: a randomized controlled trial. J Interpers Viol. (2022) 37:NP4187–211. doi: 10.1177/0886260520958660

72. Della Longa, NM, and De Young, KP. Experiential avoidance, eating expectancies, and binge eating: a preliminary test of an adaption of the acquired preparedness model of eating disorder risk. Appetite. (2018) 120:423–30. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.09.022

73. Fulton, JJ, Lavender, JM, Tull, MT, Klein, AS, Muehlenkamp, JJ, and Gratz, KL. The relationship between anxiety sensitivity and disordered eating: the mediating role of experiential avoidance. Eat Behav. (2012) 13:166–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.12.003

74. Oldershaw, A, Lavender, T, Sallis, H, Stahl, D, and Schmidt, U. Emotion generation and regulation in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of self-report data. Clin Psychol Rev. (2015) 39:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.04.005

75. Wooldridge, JS, Herbert, MS, Dochat, C, and Afari, N. Understanding relationships between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, binge-eating symptoms, and obesity-related quality of life: the role of experiential avoidance. Eat Disord. (2021) 29:260–75. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2020.1868062

76. Brady, KT, Killeen, TK, Brewerton, T, and Lucerini, S. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2000) 61:22–32.

77. Brewerton, TD. Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: focus on PTSD. Eat Disord. (2007) 15:285–304. doi: 10.1080/10640260701454311

78. Hambleton, A, Pepin, G, Le, A, Maloney, D, National Eating Disorder Research, C, Touyz, S, et al. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of eating disorders: findings from a rapid review of the literature. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:132. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00654-2

79. Goodnight, JRM, Ragsdale, KA, Rauch, SAM, and Rothbaum, BO. Psychotherapy for PTSD: An evidence-based guide to a theranostic approach to treatment. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 88:418–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.05.006

80. van Minnen, A, Harned, MS, Zoellner, L, and Mills, K. Examining potential contraindications for prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2012) 2012:3. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.18805

81. Mills, KL, Teesson, M, Back, SE, Brady, KT, Baker, AL, Hopwood, S, et al. Integrated exposure-based therapy for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. (2012) 308:690–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9071

82. Ronconi, JM, Shiner, B, and Watts, BV. Inclusion and exclusion criteria in randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy for PTSD. J Psychiatr Pract. (2014) 20:25–37. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000442936.23457.5b

83. Ruglass, LM, Lopez-Castro, T, Papini, S, Killeen, T, Back, SE, and Hien, DA. Concurrent treatment with prolonged exposure for co-occurring full or subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Psychother Psychosom. (2017) 86:150–61. doi: 10.1159/000462977

84. Cloitre, M, Courtois, CA, Charuvastra, A, Carapezza, R, Stolbach, BC, and Green, BL. Treatment of complex PTSD: results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. J Trauma Stress. (2011) 24:615–27. doi: 10.1002/jts.20697

85. Cloitre, M, Petkova, E, Wang, J, and Lu Lassell, F. An examination of the influence of a sequential treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Depress Anxiety. (2012) 29:709–17. doi: 10.1002/da.21920

86. Cloitre, M, Stovall-McClough, KC, Nooner, K, Zorbas, P, Cherry, S, Jackson, CL, et al. Treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2010) 167:915–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081247

87. ISSTD. Guidelines for treating dissociative identity disorder in adults, third revision. J Trauma Dissociation. (2011) 12:115–87. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2011.537247

88. Dagan, Y, and Yager, J. Severe bupropion XR abuse in a patient with long-standing bulimia nervosa and complex PTSD. Int J Eat Disord. (2018) 51:1207–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.22948

89. Rorty, M, and Yager, J. Histories of childhood trauma and complex post-traumatic sequelae in women with eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. (1996) 19:773–91. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70381-6

90. Van der Kolk, BA. Assessment and treatment of complex PTSD In: R Yehuda, editor. Treating trauma survivors with PTSD (pp. 127–156) : Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing (2002)

91. Davis, ML, Fletcher, T, McIngvale, E, Cepeda, SL, Schneider, SC, La Buissonniere Ariza, V, et al. Clinicians' perspectives of interfering behaviors in the treatment of anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders in adults and children. Cogn Behav Ther. (2020) 49:81–96. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2019.1579857

92. Federici, A, and Wisniewski, L. An intensive DBT program for patients with multidiagnostic eating disorder presentations: a case series analysis. Int J Eat Disord. (2013) 46:322–31. doi: 10.1002/eat.22112

93. Federici, A, Wisniewski, L, and Ben-Porath, D. Description of an intensive dialectical behavior therapy program for multidiagnostic clients with eating disorders. J Couns Dev. (2012) 90:330–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.00041.x

94. De Jongh, A, Resick, PA, Zoellner, LA, van Minnen, A, Lee, CW, Monson, CM, et al. Critical analysis of the current treatment guidelines for complex PTSD in adults. Depress Anxiety. (2016) 33:359–69. doi: 10.1002/da.22469

95. Cloitre, M. Commentary on De Jongh Et Al. (2016) Critique of Istss complex Ptsd guidelines: finding the way forward. Depress Anxiety. (2016) 33:355–6. doi: 10.1002/da.22493

96. Brewerton, TD. Mechanisms by which adverse childhood experiences, other traumas and PTSD influence the health and well-being of individuals with eating disorders throughout the life span. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:162. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00696-6

97. Liebman, RE, Becker, KR, Smith, KE, Cao, L, Keshishian, AC, Crosby, RD, et al. Network analysis of posttraumatic stress and eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adults exposed to childhood abuse. J Trauma Stress. (2020) 34:665–74. doi: 10.1002/jts.22644

98. Monteleone, AM, Tzischinsky, O, Cascino, G, Alon, S, Pellegrino, F, Ruzzi, V, et al. The connection between childhood maltreatment and eating disorder psychopathology: a network analysis study in people with bulimia nervosa and with binge eating disorder. Eat Weight Disord. (2022) 27:253–61. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01169-6

99. Nelson, JD, Cuellar, AE, Cheskin, LJ, and Fischer, S. Eating disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder: a network analysis of the comorbidity. Behav Ther. (2021) 53:310–22. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2021.09.006

100. Vanzhula, IA, Calebs, B, Fewell, L, and Levinson, CA. Illness pathways between eating disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms: understanding comorbidity with network analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2019) 27:147–60. doi: 10.1002/erv.2634

101. Cook, JM, Simiola, V, Hamblen, JL, Bernardy, N, and Schnurr, PP. The influence of patient readiness on implementation of evidence-based PTSD treatments in veterans affairs residential programs. Psychol Trauma. (2017) 9:51–8. doi: 10.1037/tra0000162

102. Fetahi, E, Sogaard, AS, and Sjogren, M. Estimating the effect of motivational interventions in patients with eating disorders: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Pers Med. (2022) 12:577. doi: 10.3390/jpm12040577

103. Geller, J, Brown, KE, and Srikameswaran, S. The efficacy of a brief motivational intervention for individuals with eating disorders: a randomized control trial. Int J Eat Disord. (2011) 44:497–505. doi: 10.1002/eat.20847

104. Jakupcak, M, Hoerster, KD, Blais, RK, Malte, CA, Hunt, S, and Seal, K. Readiness for change predicts VA mental healthcare utilization among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. J Trauma Stress. (2013) 26:165–8. doi: 10.1002/jts.21768

105. Kaysen, D, Jaffe, AE, Shoenberger, B, Walton, TO, Pierce, AR, and Walker, DD. Does effectiveness of a brief substance use treatment depend on PTSD? An evaluation of motivational enhancement therapy for active-duty Army personnel. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. (2022) 83:924–33. doi: 10.15288/jsad.22-00011

106. Killeen, TK, Cassin, SE, and Geller, J. Motivational interviewing in the treatment of substance use disorders, addictions, and eating disorders In: TD Brewerton and AB Dennis, editors. Eating Disorders, addictions and substance use Disorders: Research, Clinical and Treratment Perspectives : Berlin, Germany: Springer (2014)

107. Vitousek, K, Watson, S, and Wilson, GT. Enhancing motivation for change in treatment-resistant eating disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. (1998) 18:391–420. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00012-9

108. Weiss, CV, Mills, JS, Westra, HA, and Carter, JC. A preliminary study of motivational interviewing as a prelude to intensive treatment for an eating disorder. J Eat Disord. (2013) 1:34. doi: 10.1186/2050-2974-1-34

109. Chuemere, AN, Oluwatayo, BO, Kolawole, TA, and Ilochi, ON. Starvation-induced changes in memory sensitization, habituation and psychosomatic responses. Int J Trop Dis Health. (2019) 35:1–7. doi: 10.9734/ijtdh/2019/v35i330126

110. Park, SB, Coull, JT, McShane, RH, Young, AH, Sahakian, BJ, Robbins, TW, et al. Tryptophan depletion in normal volunteers produces selective impairments in learning and memory. Neuropharmacology. (1994) 33:575–88. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90089-2

111. Riedel, WJ, Klaassen, T, Deutz, NE, van Someren, A, and van Praag, HM. Tryptophan depletion in normal volunteers produces selective impairment in memory consolidation. Psychopharmacology. (1999) 141:362–9. doi: 10.1007/s002130050845

112. Brewerton, TD, Gavidia, I, Suro, G, and Perlman, MM. Eating disorder patients with and without PTSD treated in residential care: discharge and 6-month follow-up results. J Eat Disord. (2023) 11:48. doi: 10.1186/s40337-023-00773-4

113. Trottier, K, and Monson, CM. Integrating cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder with cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders in PROJECT RECOVER. Eat Disord. (2021) 29:307–25. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2021.1891372

114. Brewin, N, Baggott, J, Dugard, P, and Arcelus, J. Clinical normative data for eating disorder examination questionnaire and eating disorder inventory for DSM-5 feeding and eating disorder classifications: a retrospective study of patients formerly diagnosed via DSM-IV. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2014) 22:299–305. doi: 10.1002/erv.2301

115. Blevins, CA, Weathers, FW, Davis, MT, Witte, TK, and Domino, JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. (2015) 28:489–98. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059

116. Des Jarlais, DC. Harm reduction in the USA: the research perspective and an archive to David purchase. Harm Reduct J. (2017) 14:51. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0178-6

117. Logan, DE, and Marlatt, GA. Harm reduction therapy: a practice-friendly review of research. J Clin Psychol. (2010) 66:201–14. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20669

118. Yager, J. Why defend harm reduction for severe and enduring eating Disorders? Who Wouldn't want to reduce harms? Am J Bioeth. (2021) 21:57–9. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2021.1926160

119. Brewerton, TD. Posttraumatic stress disorder and disordered eating: food addiction as self-medication. J Women's Health (Larchmt). (2011) 20:1133–4. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3050

120. Kearney-Cooke, A, and Striegel-Moore, RH. Treatment of childhood sexual abuse in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a feminist psychodynamic approach. Int J Eat Disord. (1994) 15:305–19. doi: 10.1002/eat.2260150402

121. Brewerton, T. D., Trottier, K., Trim, J. G., Myers, T., and Wonderlich, S. (2020). Integrating evidence-based treatments for eating disorder patients with comorbid PTSD and trauma-related Disorders. In C. C. Tortolani, A. B. Goldschmidt, and D. GrangeLe (Eds.), Adapting evidence-based treatments for eating Disorders for novel populations and settings: A practical guide (pp. 216–237). New York, NY: Routledge.

122. Trottier, K, Monson, CM, Wonderlich, SA, and Crosby, RD. Results of the first randomized controlled trial of integrated cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. (2022) 52:587–96. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721004967

123. Trottier, K, Monson, CM, Wonderlich, SA, and Olmsted, MP. Initial findings from project recover: overcoming co-occurring eating disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder through integrated treatment. J Trauma Stress. (2017) 30:173–7. doi: 10.1002/jts.22176

124. Bloomgarden, A, and Calogero, RM. A randomized experimental test of the efficacy of EMDR treatment on negative body image in eating disorder inpatients. Eat Disord. (2008) 16:418–27. doi: 10.1080/10640260802370598

125. Bongaerts, H, Van Minnen, A, and de Jongh, A. Intensive EMDR to treat patients with complex posttraumatic stress disorder: a case series. J EMDR Pract Res. (2017) 11:84–95. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.11.2.84

126. Boterhoven de Haan, KL, Lee, CW, Fassbinder, E, van Es, SM, Menninga, S, Meewisse, ML, et al. Imagery rescripting and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing as treatment for adults with post-traumatic stress disorder from childhood trauma: randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry. (2020) 217:609–15. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.158

127. Claudat, K, Reilly, EE, Convertino, AD, Trim, J, Cusack, A, and Kaye, WH. Integrating evidence-based PTSD treatment into intensive eating disorders treatment: a preliminary investigation. Eat Weight Disord. (2022) 27:3599–607. doi: 10.1007/s40519-022-01500-9

128. Cuijpers, P, Veen, SCV, Sijbrandij, M, Yoder, W, and Cristea, IA. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for mental health problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. (2020) 49:165–80. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2019.1703801

129. Daneshvar, S, Shafiei, M, and Basharpoor, S. Compassion-focused therapy: proof of concept trial on suicidal ideation and cognitive distortions in female survivors of intimate partner violence with PTSD. J Interpers Viol. (2022) 37:NP9613–34. doi: 10.1177/0886260520984265

130. Goss, K, and Allan, S. The development and application of compassion-focused therapy for eating disorders (CFT-E). Br J Clin Psychol. (2014) 53:62–77. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12039

131. Irons, C, and Lad, S. Using compassion focused therapy to work with shame and self-criticism in complex PTSD. Aust Clin Psychol. (2017) 3:47–54.

132. Kelly, AC, Wisniewski, L, Martin-Wagar, C, and Hoffman, E. Group-based compassion-focused therapy as an adjunct to outpatient treatment for eating disorders: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2017) 24:475–87. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2018

133. Lawrence, VA, and Lee, D. An exploration of people's experiences of compassion-focused therapy for trauma, using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2014) 21:495–507. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1854

134. Lely, JCG, Smid, GE, Jongedijk, RA, Knipscheer, JW, and Kleber, RJ. The effectiveness of narrative exposure therapy: a review, meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2019) 10:1550344. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018.1550344

135. Luo, X, Che, X, Lei, Y, and Li, H. Investigating the influence of self-compassion-focused interventions on posttraumatic stress: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Mindfulness. (2021) 12:2865–76. doi: 10.1007/s12671-021-01732-3

136. Monson, CM, Chard, KM, and Morland, LA. Written exposure therapy vs cognitive processing therapy. JAMA Psychiatry. (2018) 75:757–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0810

137. Moreno-Alcazar, A, Treen, D, Valiente-Gomez, A, Sio-Eroles, A, Perez, V, Amann, BL, et al. Efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in children and adolescent with post-traumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:1750. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01750

138. Morkved, N, Hartmann, K, Aarsheim, LM, Holen, D, Milde, AM, Bomyea, J, et al. A comparison of narrative exposure therapy and prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Clin Psychol Rev. (2014) 34:453–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.005

139. Rothbaum, BO, Astin, MC, and Marsteller, F. Prolonged exposure versus eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for PTSD rape victims. J Trauma Stress. (2005) 18:607–16. doi: 10.1002/jts.20069

140. Sloan, DM, Marx, BP, Lee, DJ, and Resick, PA. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. (2018) 75:233–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4249

141. Ten Napel-Schutz, MC, Vroling, M, Mares, SHW, and Arntz, A. Treating PTSD with imagery rescripting in underweight eating disorder patients: a multiple baseline case series study. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:35. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00558-1

142. ten Napel-Schutz, MC, Karbouniaris, S, Mares, SHW, Arntz, A, and Abma, TA. Perspectives of underweight people with eating disorders on receiving imagery Rescripting trauma treatment: a qualitative study of their experiences. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:188. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00712-9

143. Fogelkvist, M, Gustafsson, SA, Kjellin, L, and Parling, T. Acceptance and commitment therapy to reduce eating disorder symptoms and body image problems in patients with residual eating disorder symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Body Image. (2020) 32:155–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.01.002

144. Juarascio, AS, Forman, EM, and Herbert, JD. Acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive therapy for the treatment of comorbid eating pathology. Behav Modif. (2010) 34:175–90. doi: 10.1177/0145445510363472

145. Linardon, J, Fairburn, CG, Fitzsimmons-Craft, EE, Wilfley, DE, and Brennan, L. The empirical status of the third-wave behaviour therapies for the treatment of eating disorders: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 58:125–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.005

146. Orsillo, SM, and Batten, SV. Acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Modif. (2005) 29:95–129. doi: 10.1177/0145445504270876

147. Back, M, Falkenstrom, F, Gustafsson, SA, Andersson, G, and Holmqvist, R. Reduction in depressive symptoms predicts improvement in eating disorder symptoms in interpersonal psychotherapy: results from a naturalistic study. J Eat Disord. (2020) 8:33. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-00308-1

148. Duberstein, PR, Ward, EA, Chaudron, LH, He, H, Toth, SL, Wang, W, et al. Effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy-trauma for depressed women with childhood abuse histories. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2018) 86:868–78. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000335

150. Markowitz, JC, Petkova, E, Neria, Y, Van Meter, PE, Zhao, Y, Hembree, E, et al. Is exposure necessary? A randomized clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. (2015) 172:430–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070908

151. Schramm, E, Schneider, D, Zobel, I, van Calker, D, Dykierek, P, Kech, S, et al. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy in chronically depressed inpatients. J Affect Disord. (2008) 109:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.013

152. Whiston, A, Bockting, CLH, and Semkovska, M. Towards personalising treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of face-to-face efficacy moderators of cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. (2019) 49:2657–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719002812

153. Donovan, DM, Daley, DC, Brigham, GS, Hodgkins, CC, Perl, HI, Garrett, SB, et al. Stimulant abuser groups to engage in 12-step: a multisite trial in the National Institute on Drug Abuse clinical trials network. J Subst Abus Treat. (2013) 44:103–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.04.004

154. Kelly, JF, Abry, A, Ferri, M, and Humphreys, K. Alcoholics anonymous and 12-step facilitation treatments for alcohol use disorder: a distillation of a 2020 Cochrane review for clinicians and policy makers. Alcohol Alcohol. (2020) 55:641–51. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agaa050

155. Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. (1997) 58:7–29. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.7

156. Mitchell, KS, Singh, S, Hardin, S, and Thompson-Brenner, H. The impact of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder on eating disorder treatment outcomes: investigating the unified treatment model. Int J Eat Disord. (2021) 54:1260–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.23515

157. Church, D, Stapleton, P, Mollon, P, Feinstein, D, Boath, E, Mackay, D, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of PTSD using clinical EFT (emotional freedom techniques). Healthcare. (2018) 6:146. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6040146

158. Monteleone, AM, Pellegrino, F, Croatto, G, Carfagno, M, Hilbert, A, Treasure, J, et al. Treatment of eating disorders: a systematic meta-review of meta-analyses and network meta-analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2022) 142:104857. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104857

159. Sijercic, I, Liebman, RE, Ip, J, Whitfield, KM, Ennis, N, Sumantry, D, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual and couple therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder: clinical and intimate relationship outcomes. J Anxiety Disord. (2022) 91:102613. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102613

160. Bohus, M, Dyer, AS, Priebe, K, Kruger, A, Kleindienst, N, Schmahl, C, et al. Dialectical behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse in patients with and without borderline personality disorder: a randomised controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. (2013) 82:221–33. doi: 10.1159/000348451

161. Harned, MS, Gallop, RJ, and Valenstein-Mah, HR. What changes when? The course of improvement during a stage-based treatment for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Psychother Res. (2018) 28:761–75. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1252865

162. Bellehsen, M, Stoycheva, V, Cohen, BH, and Nidich, S. A pilot randomized controlled trial of transcendental meditation as treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans. J Trauma Stress. (2021) 35:22–31. doi: 10.1002/jts.22665

163. Bormann, JE, Thorp, SR, Smith, E, Glickman, M, Beck, D, Plumb, D, et al. Individual treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder using Mantram repetition: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2018) 175:979–88. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17060611

164. Carei, TR, Fyfe-Johnson, AL, Breuner, CC, and Brown, MA. Randomized controlled clinical trial of yoga in the treatment of eating disorders. J Adolesc Health. (2010) 46:346–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.007

165. Foa, E, Hembree, E, and Rothbaum, BO. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: emotional processing of traumatic experiences, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press (2007).

166. Gallegos, AM, Crean, HF, Pigeon, WR, and Heffner, KL. Meditation and yoga for posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 58:115–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.004

167. Haider, T, Chia-Liang, D, and Sharma, M. Efficacy of meditation-based interventions on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among veterans: a narrative review. Adv Mind Body Med. (2021) 35:16–24.

168. Hilton, L, Maher, AR, Colaiaco, B, Apaydin, E, Sorbero, ME, Booth, M, et al. Meditation for posttraumatic stress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Trauma. (2017) 9:453–60. doi: 10.1037/tra0000180

169. Kelly, U, Haywood, T, Segell, E, and Higgins, M. Trauma-sensitive yoga for post-traumatic stress disorder in women veterans who experienced military sexual trauma: interim results from a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. (2021) 27:S45–59. doi: 10.1089/acm.2020.0417

170. Mavranezouli, I, Megnin-Viggars, O, Daly, C, Dias, S, Stockton, S, Meiser-Stedman, R, et al. Research review: psychological and psychosocial treatments for children and young people with post-traumatic stress disorder: a network meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2020) 61:18–29. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13094

171. Mitchell, KS, Mazzeo, SE, Rausch, SM, and Cooke, KL. Innovative interventions for disordered eating: evaluating dissonance-based and yoga interventions. Int J Eat Disord. (2007) 40:120–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.20282

172. Seppala, EM, Nitschke, JB, Tudorascu, DL, Hayes, A, Goldstein, MR, Nguyen, DT, et al. Breathing-based meditation decreases posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in U.S. military veterans: a randomized controlled longitudinal study. J Trauma Stress. (2014) 27:397–405. doi: 10.1002/jts.21936

173. Iverson, KM, Litwack, SD, Pineles, SL, Suvak, MK, Vaughn, RA, and Resick, PA. Predictors of intimate partner violence revictimization: the relative impact of distinct PTSD symptoms, dissociation, and coping strategies. J Trauma Stress. (2013) 26:102–10. doi: 10.1002/jts.21781

174. Bajor, LA, Balsara, C, and Osser, DN. An evidence-based approach to psychopharmacology for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) -2022 update. Psychiatry Res. (2022) 317:114840. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114840

175. Bisson, JI, Baker, A, Dekker, W, and Hoskins, MD. Evidence-based prescribing for post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry. (2020) 216:125–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.40

176. Himmerich, H, Kan, C, Au, K, and Treasure, J. Pharmacological treatment of eating disorders, comorbid mental health problems, malnutrition and physical health consequences. Pharmacol Ther. (2021) 217:107667. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107667

177. Himmerich, H, and Treasure, J. Psychopharmacological advances in eating disorders. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. (2018) 11:95–108. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2018.1383895

178. Hoskins, MD, Bridges, J, Sinnerton, R, Nakamura, A, Underwood, JFG, Slater, A, et al. Pharmacological therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of monotherapy, augmentation and head-to-head approaches. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2021) 12:1802920. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1802920

179. Hoskins, MD, Sinnerton, R, Nakamura, A, Underwood, JFG, Slater, A, Lewis, C, et al. Pharmacological-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2021) 12:1853379. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1853379

180. Aigner, M, Treasure, J, Kaye, W, Kasper, S, and Disorders, WTFOE. World Federation of Societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of eating disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2011) 12:400–43. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.602720

181. Amodeo, G, Cuomo, A, Bolognesi, S, Goracci, A, Trusso, MA, Piccinni, A, et al. Pharmacotherapeutic strategies for treating binge eating disorder. Evidence from clinical trials and implications for clinical practice. Expert Opin Pharmacother. (2019) 20:679–90. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2019.1571041

182. Arnold, LM, McElroy, SL, Hudson, JI, Welge, JA, Bennett, AJ, and Keck, PE. A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of fluoxetine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2002) 63:1028–33. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v63n1113

183. Attia, E, Steinglass, JE, Walsh, BT, Wang, Y, Wu, P, Schreyer, C, et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2019) 176:449–56. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18101125

184. Bajor, LA, Ticlea, AN, and Osser, DN. The psychopharmacology algorithm Project at the Harvard south shore program: an update on posttraumatic stress disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. (2011) 19:240–58. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.614483

185. Brewerton, TD. Antipsychotic agents in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: neuropsychopharmacologic rationale and evidence from controlled trials. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2012) 14:398–405. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0287-6

186. Brownley, KA, Peat, CM, La Via, M, and Bulik, CM. Pharmacological approaches to the management of binge eating disorder. Drugs. (2015) 75:9–32. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0327-0

187. Carey, P, Suliman, S, Ganesan, K, Seedat, S, and Stein, DJ. Olanzapine monotherapy in posttraumatic stress disorder: efficacy in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hum Psychopharmacol. (2012) 27:386–91. doi: 10.1002/hup.2238

188. Fluoxetine Bulimia Nervosa Collaborative Study Group. Fluoxetine in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. A multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1992) 49:139–47. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820020059008

189. Goldstein, DJ, Wilson, MG, Thompson, VL, Potvin, JH, and Rampey, AH. Long-term fluoxetine treatment of bulimia nervosa. Fluoxetine bulimia nervosa research group. Br J Psychiatry. (1995) 166:660–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.5.660

190. Hay, PJ, and Claudino, AM. Clinical psychopharmacology of eating disorders: a research update. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. (2012) 15:209–22. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000460

191. Hedges, DW, Reimherr, FW, Hoopes, SP, Rosenthal, NR, Kamin, M, Karim, R, et al. Treatment of bulimia nervosa with topiramate in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, part 2: improvement in psychiatric measures. J Clin Psychiatry. (2003) 64:1449–54. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v64n1208

192. Hoopes, SP, Reimherr, FW, Hedges, DW, Rosenthal, NR, Kamin, M, Karim, R, et al. Treatment of bulimia nervosa with topiramate in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, part 1: improvement in binge and purge measures. J Clin Psychiatry. (2003) 64:1335–41. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v64n1109

193. McElroy, SL, Arnold, LM, Shapira, NA, Keck, PE Jr, Rosenthal, NR, Karim, MR, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2003) 160:255–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.255

194. Milano, W, De Rosa, M, Milano, L, Riccio, A, Sanseverino, B, and Capasso, A. The pharmacological options in the treatment of eating disorders. ISRN Pharmacol. (2013) 2013:352865. doi: 10.1155/2013/352865

195. Pae, CU, Lim, HK, Peindl, K, Ajwani, N, Serretti, A, Patkar, AA, et al. The atypical antipsychotics olanzapine and risperidone in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2008) 23:1–8. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32825ea324

196. Romano, SJ, Halmi, KA, Sarkar, NP, Koke, SC, and Lee, JS. A placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in continued treatment of bulimia nervosa after successful acute fluoxetine treatment. Am J Psychiatry. (2002) 159:96–102. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.96

197. Stein, MB, Kline, NA, and Matloff, JL. Adjunctive olanzapine for SSRI-resistant combat-related PTSD: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. (2002) 159:1777–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1777