- 1Department of Psychology, Suzhou Guangji Hospital, The Affiliated Guangji Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China

- 2Department of Neurology, The Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Suzhou Municipal Hospital, Suzhou, China

- 3Moral Education Research Center, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

- 4Department of Nursing, The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China

- 5Department of Biology, Eastern Nazarene College, Quincy, MA, United States

- 6Department of Nursing, Suzhou Guangji Hospital, The Affiliated Guangji Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China

Mindfulness training among patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) reduces symptoms, prevents relapse, improves prognosis, and is more efficient for those with a high level of trait mindfulness. Upon hospital admission, 126 MDD patients completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief, Five-Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), and the Rumination Response Scale (RRS). The 65 patients that scored less than the median of all subjects on the FFMQ were placed into the low mindfulness level (LML) group. The other 61 patients were placed in the high mindfulness level (HML) group. All facet scores were statistically different between the mental health assessment scores of the HML and LML groups except for RRS brooding and FFMQ nonjudgement. Trait mindfulness level exhibited a negative and bidirectional association with MDD severity primarily through the facets of description and aware actions. Trait mindfulness was also related positively with age primarily through the facets of nonreactivity and nonjudgement. Being married is positively associated with trait mindfulness levels primarily through the facet of observation and by an associated increase in perceived quality of life. Mindfulness training prior to MDD diagnosis also associates positively with trait mindfulness level. Hospitalized MDD patients should have their trait mindfulness levels characterized to predict treatment efficiency, help establish a prognosis, and identify mindfulness-related therapeutic targets.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD), also known as clinical depression, is a common and debilitating mood disorder. Risk for MDD increases with age. About 6% of adults worldwide have MDD (1). However, it is estimated that up to 13.3% of the world’s elderly population has MDD (2). To receive a diagnosis, individuals must have at least five recognized symptoms that persist for two weeks or more. Examples of recognized symptoms include diminished mood, reduced interest, or pleasure in almost all activities that once were pleasurable and of interest, reduction in physical movement, increased fatigue, reduced ability to concentrate and make decisions, recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation, and changes in sleep and appetite (3, 4). A biological association between advanced age, MDD, suicidal risk, and diminished clinical outcomes is a pathological upregulation of specific inflammatory cytokines (5). The family and societal burden of MDD ranks first among all neuropsychiatric diseases and is a leading cause of disease burden worldwide (6). Tragically, MDD has a low rate of clinical recognition, medical consultation, and effective treatment (6, 7).

In the cases of unsuccessful therapeutic intervention, it behooves the clinician to pursue novel alternatives. For example, buprenorphine has been effective at treating patients who are otherwise resistant to traditional pharmacological interventions (8). Nonpharmacological interventions are also critical to incorporate into the treatment plan for MDD patients, such as psychotherapy. Mindfulness-related psychotherapy has become a prevalent form of modern psychological treatment for MDD and a variety of other disorders. Mindfulness is the meditative process of shifting attention from the perceived activity of the mind to the perception of present experiences in a nonjudgmental and relaxed state (9–11). Stated more simply, mindfulness meditation is “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and nonjudgmentally” (12). The nonjudgmental aspect of mindfulness allows for the acknowledgement and acceptance of mental activities, such as patterns of attention and sensory processing.

The capacity for mindfulness is an innate and relatively stable human trait that can be improved with intervention (13). Mindfulness training has been shown to help patients improve their emotional regulation and diminish the occurrence of habitual automatic negative thought patterns, such as depression-related rumination and catastrophizing (11, 14). Importantly, mindfulness training helps patients with MDD to prevent relapses and improves their prognosis (9–11, 15). However, trait mindfulness level impacts the magnitude of the effect that mindfulness training has (16). Indeed, scored trait mindfulness dimensions can reliably predict the extent that most of the assayed dimensions can change due to mindfulness-based interventions (17).

Patients with MDD have on average significantly lower mindfulness levels compared to healthy controls on scored tests such as the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (18). The Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) is a popular and well-established tool for surveying the robustness of a person’s mindfulness (19). The FFMQ addresses a person’s capacity to observe their environment and inner experience, a person’s capacity to describe their observations, the depth of awareness a person has of their actions, a person’s capacity to accept their emotions for what they are and without judgment, and finally, a person’s ability to perceive their emotions without needing to react to them. The FFMQ is used in this study to score trait mindfulness levels among MDD patients.

MDD is a prevalent mood disorder that significantly impairs a person’s ability to engage in life with enjoyment, vigor, and cognitive acuity. Mindfulness-based psychotherapy has become widely incorporated into the treatment of many affective and behavioral disorders, including MDD. Trait mindfulness, also referred to as dispositional or baseline mindfulness, influences the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions (20). We hypothesize that the trait mindfulness levels among patients hospitalized for MDD will significantly differ according to a characteristic profile of factors. Therefore, in this current study we investigated the trait mindfulness levels of patients hospitalized for MDD and the factors that influence their trait mindfulness at baseline. The findings of this study can help clinicians identify MDD patients who would benefit the most from mindfulness-based interventions and aid in the development of a prognosis.

Subjects

The subjects were admitted to Suzhou Guangji Hospital in Suzhou China, from July 2015 to June 2016 for MDD. The study inclusion criteria required that subjects met the diagnostic criteria for DSM-V major depressive disorder, had a total BDI score ≥ 5 at the time of enrollment, were aged 18–65 years, and a signed informed consent from either the patients or their family members. The study exclusion criteria included a history of manic episodes, suicide attempts, psychoactive drug dependence, a mental disorder caused by a disease other than MDD, and any other physical disease that is active and severe. The study was approved by the Suzhou Guangji Hospital Ethics Committee. The fact that the data were collected six years ago is not considered a limitation of this study. The findings remain relevant because the lifestyle of those who live in China hardly change over the years. Now that the transient and localized COVID-19 related social distancing measures have largely been dissolved, these results are reinstated as critical to explore and understand.

Methods

Assessment tools

We employed several validated self-report questionnaires to quantify various dimensions of mindfulness. For example, we relied on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to score the severity of physical and cognitive symptoms related to depression (21). The BDI and the more modern BDI-II consists of 21 questions and is designed for patients 13 years old and older. The BDI and BDI-II tools have strong evidence of convergent and discriminatory validation across many clinical and non-clinical sample populations (22). In this study, the BDI test was used, as is common in Chinese hospitals.

We also used the World Health Organization Quality-of-Life BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) to score a patient’s quality of life across four dimensions: physical health, psychological health, health of social relationships, and how supportive the patient’s environment is in promoting health (23). The WHOQOL-BREF, which consists of 26 questions, was developed as an abbreviated version of the WHOQOL-100, which contains 100 questions. The WHOQOL-BREF has shown strong relation with the WHOQOL-100 and demonstrates good convergent and discriminatory validation (24).

We used the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) to score the level of a patient’s underlying factors of mindfulness across 39 questions. These facets include observation, description, aware actions, non-judgmental inner experience, and non-reactivity (19). The FFMQ has been used in hundreds of studies to assess mindfulness and has been extensively validated. However, there has been some recent debate about its discriminant validity across cultures (25, 26).

Finally, we used the 22-question Rumination Response Scale (RRS) to score a patient’s depression symptoms and response to their depression by assessing their tendencies toward two opposite subtypes of rumination: brooding and reflection (27). Reflection seeks to establish a cognitive explanation and solution for depressed feelings, and thus, necessitates the enhancement of self-awareness and situational insight. Brooding is a maladaptive and passive rumination that is focused on how current or past circumstances do not align with a preferred situational outcome. The RRS was originally proposed in 1991 and was modified in 2003 (28–30). The RRS has been validated for various cultures, such as Turkish, French, Spanish, and Chinese cohorts (31–34).

Test reliability and validity

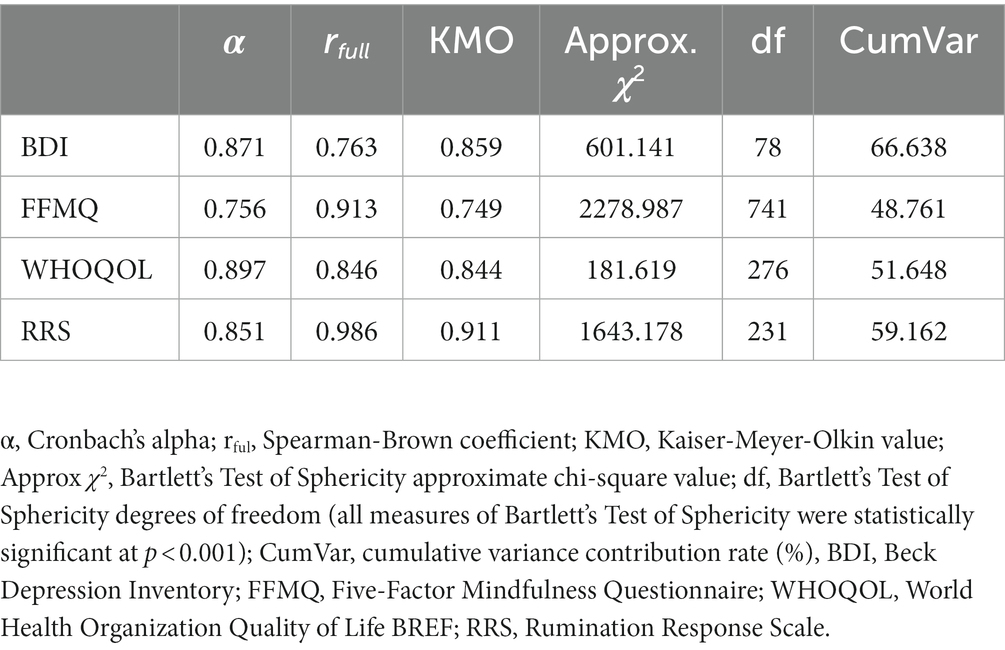

The Cronbach’s α coefficient and the half-score reliability coefficient using the Spearman-Brown formula were used to analyze internal test reliability. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Test was used to assess sampling adequacy and the appropriateness of the data for factor analysis. The BDI, FFMQ, WHOQOL-BREF, and RRS scales showed good reliability and validity in this study. The lowest Cronbach’s α coefficient values for BDI, FFMQ, WHOQOL-BREF, and RRS were 0.871, 0.756, 0.897, and 0.851, respectively. The lowest Spearman-Brown coefficient values for BDI, FFMQ, WHOQOL-BREF, and RRS were 0.763, 0.913, 0.846, and 0.986, respectively. Therefore, the Cronbach’s α and the Spearman-Brown coefficient values were above 75.6% and achieved high reliability. The lowest Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) values for the BDI, FFMQ, WHOQOL-BREF, and RRS assessments were 0.859, 0.749, 0.844, and 0.911, respectively. The statistical significance of Bartlett’s sphericity test for all assessments reached p < 0.01. Therefore, both the KMO and Bartlett’s sphericity test values were satisfactory. The cumulative variance contribution rate of each scale ranged from 48.761 to 66.638%, indicating that the content of each scale in this study meets the requirements necessary to explain the evaluated information. The cumulative variance contribution rate was the lowest with the FFMQ, which was 48.761%. The results of test reliability and validity confirmation of BDI, FFMQ, WHOQOL-BREF, and RRS are presented in Table 1.

Demographic classifications

Patient demographic and clinical data were collected including age, gender, religious belief, education level, marital status, income level, admission date and time, course of disease, and medication. Education and income level were assessed bimodally. Education level was either recorded as “high” if it exceeded beyond 12 years, otherwise it was recorded as “low.” Income level was recorded as either “high” if the per capita month household income exceeded $500 USD, otherwise it was recorded as “low.” This bimodal assignment approach preserved our ability to perform a reliable statistical assessment. Dividing the patient data into multiple tiers reduced the per-group sample size and so only two tiers were used. Assessment of patient FFMQ performance was also binary. If a patient earned a FFMQ score of greater than the median score of 96, the patient was recorded as having a “high” mindfulness level (HML), otherwise the patient would be considered to have a “low” mindfulness level (LML). Other studies have adopted a bimodal high and low classification of subject scores on the FFMQ according to the subject’s score relative to the mean of all scores (35).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 software. Quantitative results that exhibited normal distribution are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (x-bar ± SD), as calculated by the independent sample t-test. Quantitative results that did not exhibit normal distribution are presented as the independent sample median, as calculated by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. The count data were analyzed by chi-square test and expressed as the number of cases (percentage). The independent factors that contribute to mindfulness level were analyzed by binary logistic regression analysis and linear regression analysis. Statistical difference between groups was determined to be at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics of patients with MDD

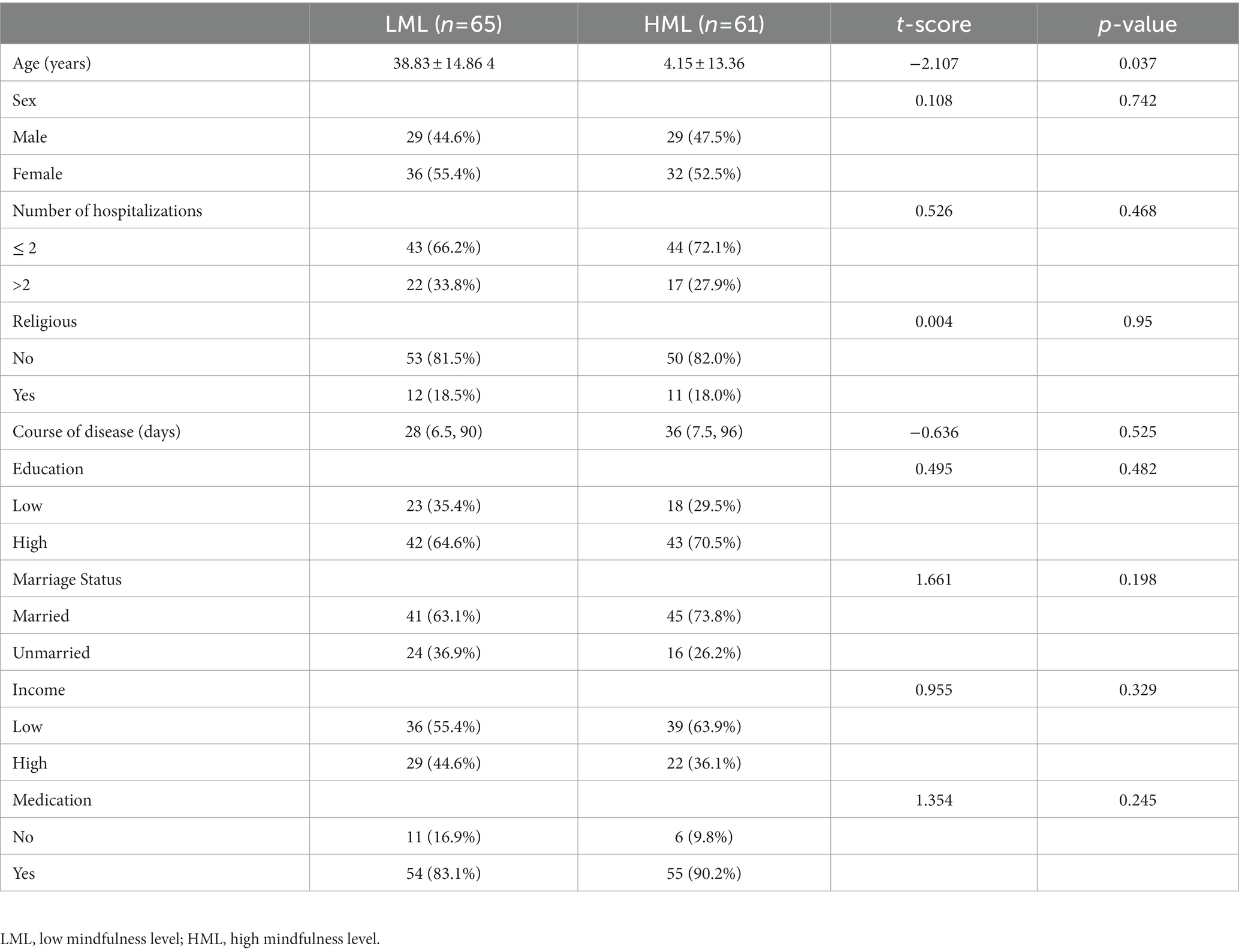

A total of 126 patients that met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study, consisting of 58 males and 68 females, aged 41.40 ± 14.29 years. Although the enrollment criteria required that patients have a clinical diagnosed case of DSM-V MDD, no patient had a mild case. All enrolled MDD patients had either a moderate or severe classification. In addition, the enrollment criteria required a BDI score of ≥5, but all patients scored >8. The range and interpretation of BDI scores include a “mild” result between scores 5 and 7, a “moderate” ranking between 8 and 15, and any score above 15 indicates “severe.” There were 12 patients with a BDI score of 8 < 15 and 114 patients with BDI score of >15. The LML group consisted of 65 patients who scored below the median FFMQ score of 96. The HML group consisted of 61 patients with an FFMQ score above 96. Compared to the LML group, the patients in the HML group were older (t = −2.107, p = 0.037). However, there were no differences (p > 0.05) between the LML and HML groups in gender, number of hospital admissions, religious belief, course of disease, education level, marital status, income level and medication use. The MDD patient demographics are presented in Table 2 according to their mindfulness level assigned at hospital admission.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of patients hospitalized with major depressive disorder according to their trait mindfulness.

Comparison of BDI, FFMQ, WHOQOL-BREF, and RRS component scores between mindfulness groups

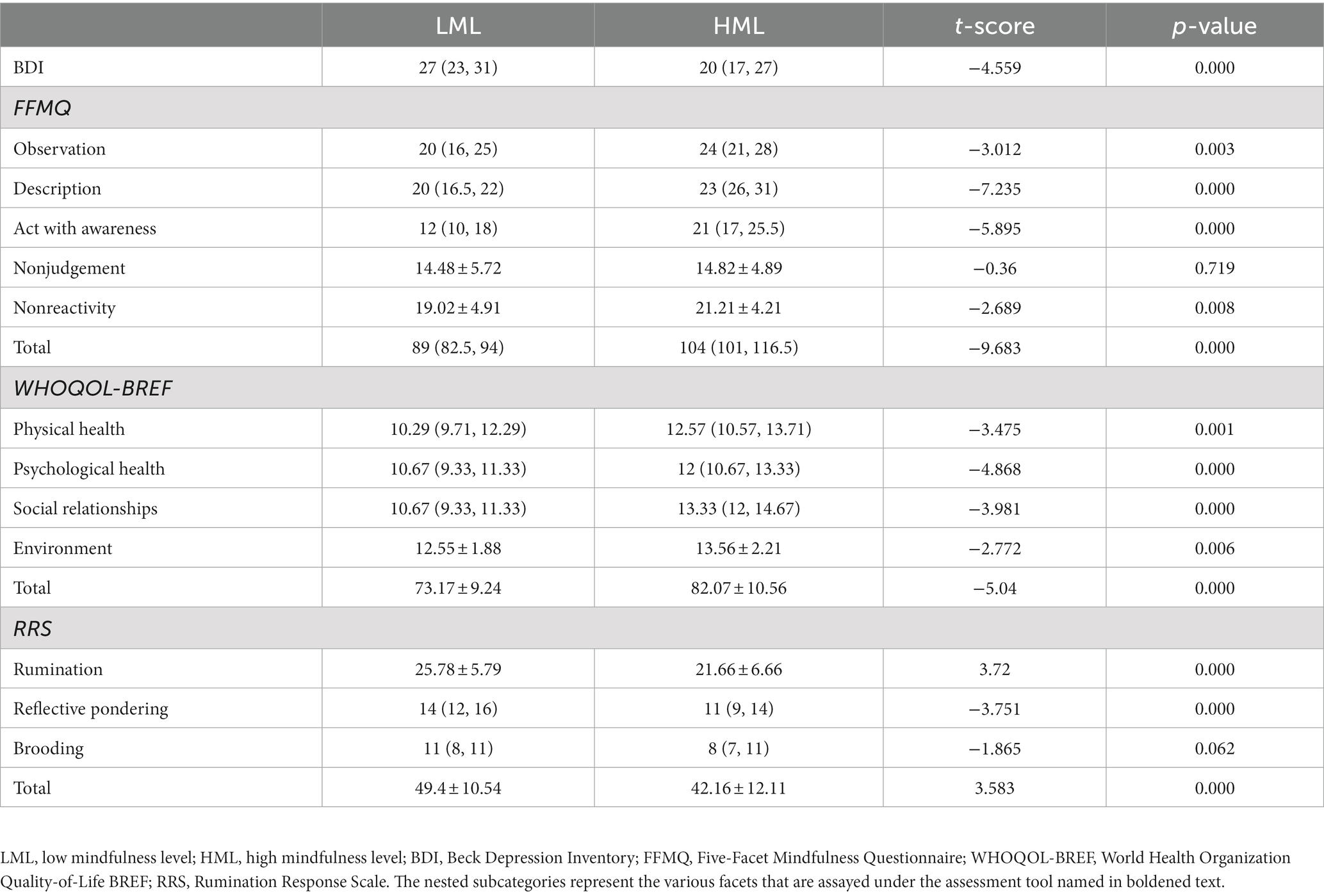

Unsurprisingly, patients with MDD in the HML group scored better on measurements of mindfulness, depression, response to a depressed mood, and quality of life than the patients with MDD in the LML group. The BDI score of MDD patients in the HML group was significantly lower than the BDI score of patients with MDD in the LML group (z = −4.559, p < 0.001). For four out of the five facets of mindfulness measured by the FFMQ (observation, description, mindful actions, and nonreactivity), the MDD patients in the HML group scored significantly higher than those in the LML group (p < 0.01). However, there was no statistical difference in the nonjudgmental inner experience metric between the two groups (t = 0.360, p = 0.719). MMD patients in the HML group scored significantly better on the WHOQOL-BREF than the LML group (p < 0.01). Consistent with these findings, patients with MDD in the HML group had RRS scores that were statistically lower than the MDD patients in the LML group for symptom rumination and reflective pondering (p < 0.01). However, there was no significant difference between the HML and LML group scores for the RRS brooding metric (z = −1.865, p = 0.062). The performance and statistical analysis of the HML and LML groups of patients with MDD on the BDI, FFMQ, WHOQOL-BREF, and RRS test components are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Depression, mindfulness, quality of life, and rumination quantification among patients with major depressive disorder according to their mindfulness groups.

Logistic regression analysis of factors that contribute to trait mindfulness level for patients with MDD

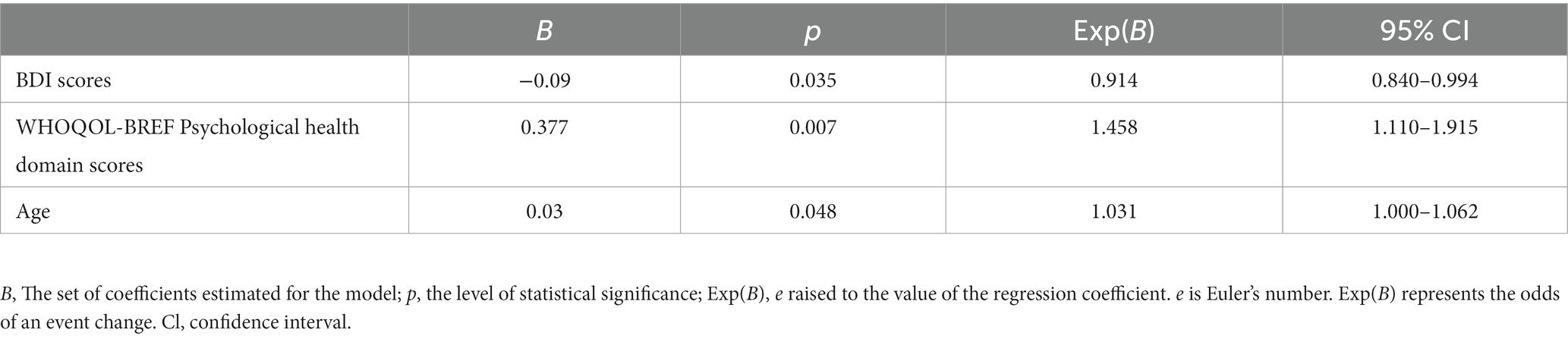

The dependent variable was the dichotomous grouping of mindfulness level. The independent variables were the factors that contributed to trait mindfulness, analyzed by univariate analysis with p < 0.2. Binary logistic regression analysis using the stepwise method showed that BDI score (Exp(B) 0.914, 95% CI 0.840–0.994, p = 0.035) was significantly negatively associated with mindfulness level, while the psychological health domain of the WHOQOL-BREF instrument was significantly and positively associated with mindfulness level (Exp(B) 1.458, 95% CI 1.110–1.915, p = 0.007). Additionally, the age of the subjects revealed significant logistic regression with trait mindfulness (Exp(B) 1.031, 95% CI 1.000–1.062, p = 0.048). The results of the binary logistic regression analysis of factors that contribute to trait mindfulness level are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Logistic regression analysis of factors that affect trait mindfulness among patients with major depressive disorder.

Multiple linear regression analysis of factors that contribute to trait mindfulness level and related metrics for patients with MDD

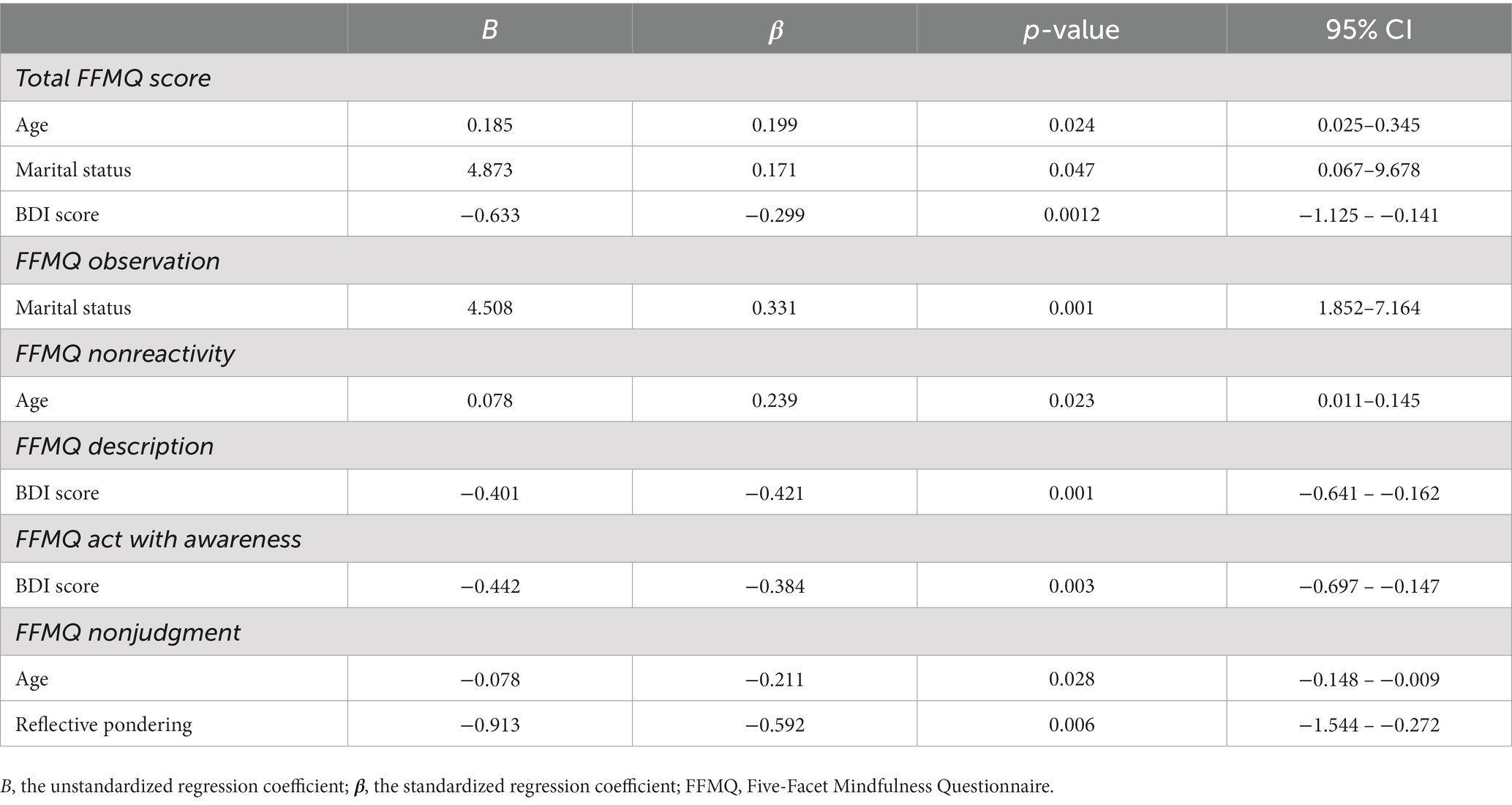

The dependent variables were the FFMQ metric scores. The independent variable were all other metrics analyzed by univariate analysis with p < 0.2. Multiple stepwise linear regression analysis showed that FFMQ scores were positively related with age and marital status, and negatively related with BDI score. The analysis of each metric showed that observation was positively associated with marital status, nonreactivity was positively associated with age, description and acting with awareness were negatively associated with BDI score, and nonjudgment was positively associated with age and reflective pondering. The results of multiple linear regression analysis of factors that contribute to of trait mindfulness level and each metric are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Multiple linear regression analysis of the five factors that affect trait mindfulness among patients with major depressive disorder.

Discussion

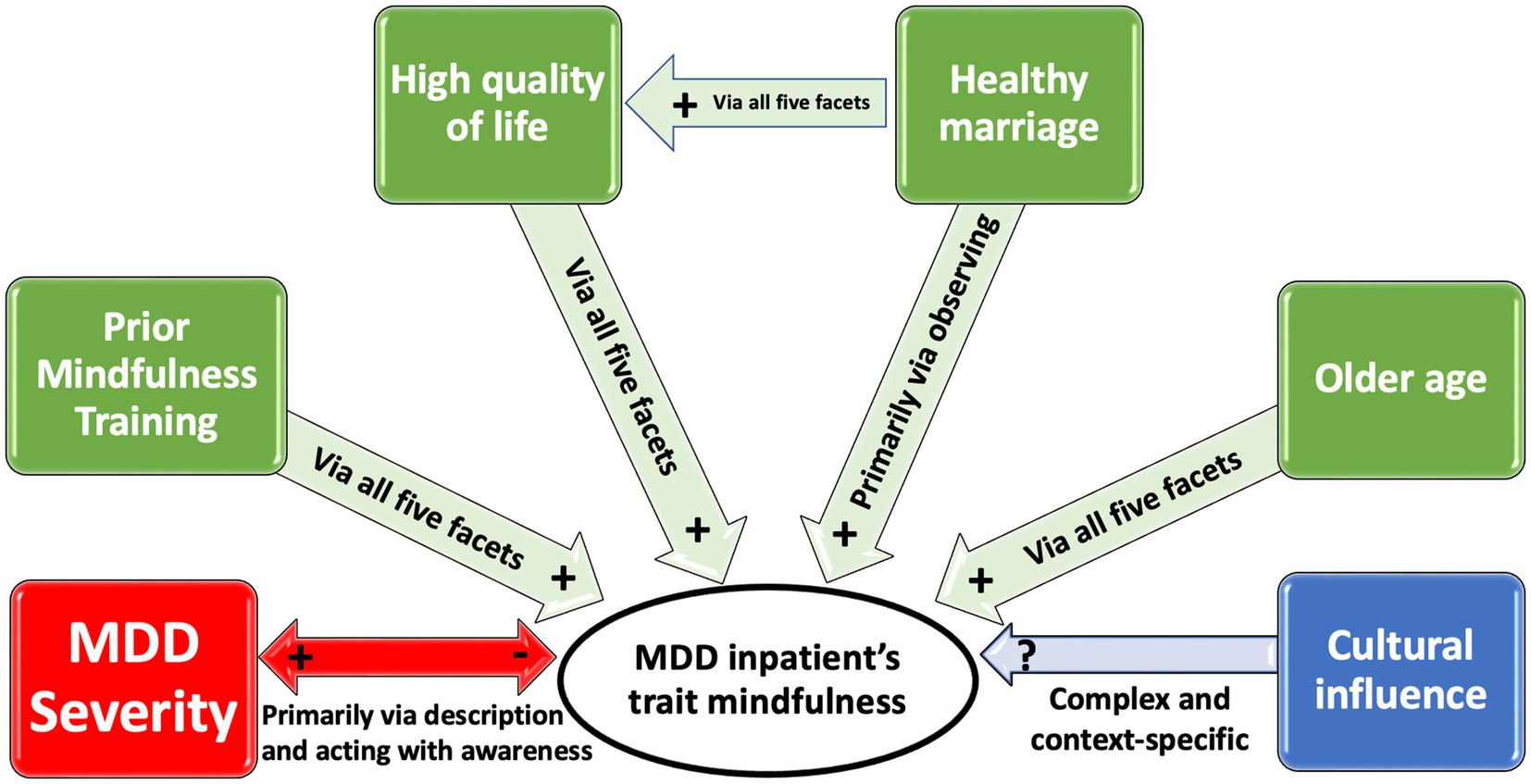

Our study has demonstrated that MDD severity, mindfulness training prior to MDD diagnosis, general psychological health related to quality of life, being married, and advanced age are all independent factors, capable of influencing trait mindfulness level, as shown in Figure 1. This study has revealed an inverse relation between MDD severity, as reported by BDI score, and the baseline level of mindfulness. Other studies have corroborated the independent negative association between trait mindfulness and severity of MDD symptoms. For example, adult patients with severe MDD and a history of attempted suicide have a low level of mindfulness (36). Furthermore, patients with primary Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and co-morbid MDD have been shown to have statistically lower levels of mindfulness compared to patients with only GAD (37). This study has also identified a negative relation between scores on the FFMQ facets of mindful description and acting with awareness with the severity of MDD as reported by BDI score. A similar finding of another study has shown that the FFMQ facet scores of nonjudgement and nonreactivity negatively relate to the depression-linked symptoms of distress and anhedonia (38). Therefore, MDD severity measured by the BDI is an independently contributing factor to trait mindfulness level. Conversely, the level of mindfulness measured by the FFMQ negatively predicts MDD. It seems likely that the five aspects of the FFMQ could represent targeted areas of intervention to either treat or prevent MDD.

Figure 1. Six factors have a positive, negative or context-specific effect on trait mindfulness of inpatients with MDD in China and their mechanisms of impact. Red and (+, −) represents a negative inverse and bidirectional correlation. Green and (+) represents a positive correlation. Blue and (?) represents a complex and context-specific correlation. “Via all five facets” refers to the mindfulness facets as scored on the FFMQ.

Mindfulness-based interventions are effective at mitigating the symptoms of severe MDD, reducing the risk of MDD relapse, and improving low levels of mindfulness among those with subclinical symptoms of mental health conditions (39). The greater the baseline severity of MDD, or the lower the level of mindfulness among MDD patients prior to engaging in mindfulness-based intervention, the greater the treatment efficiency, even in a nonclinical setting (16, 40, 41). However, regardless of the efficiency of treatment effect, trait mindfulness levels among MDD patients can be positively influenced by mindfulness-based training prior to a diagnosis and throughout treatment.

We have demonstrated that there is a positive relation between the psychological health domain score of the WHOQOL-BREF scale and trait mindfulness among MDD patients. The findings of many other studies corroborate this conclusion, as the contributing factors to psychological health and quality of life are varied and numerous. For example, among the elderly, middle-aged, and young adults with or without MDD, high mindfulness levels positively corresponds to indicators of a good quality of life, such as emotional resilience, vitality, positive emotion, and physical health (42–46). It is important to note, however, that those with MDD have a lower quality of life compared to those without mental health issues. Even among euthymic patients with MDD, it has been shown that they have a reduced quality of life (47). Regardless, the determinants of general psychological health and quality of life independently and positively correspond to trait mindfulness among MDD patients.

This study revealed a significantly higher trait mindfulness level among married couples with MDD compared to their nonmarried counterparts. Being married can be the impetus for developing a higher level of mindfulness. Alternatively, a higher level of mindfulness corresponds to an increased chance of becoming married. Either way, emotional skills such as emotion recognition, communication, and anger regulation play important roles in the association between marital quality and mindfulness level (48). Happily married individuals with higher levels of mindfulness enjoy a higher quality of life. For example, during marital conflict, the level of cardiovascular reactivity of married couples inversely associates with their mindfulness levels (49). The level of satisfaction individuals have with their romantic relationships is positively related to their level of mindfulness (50). Furthermore, meditation promotes an individual’s acceptance of themselves and their partners, which corresponds to an improved marital wellbeing (51).

Although several studies have supported the positive association between marital status and mindfulness level, the underpinning mechanisms through which marital status regulates mindfulness level remains unclear. Our results reveal that being married positively corresponds with a higher performance on the observation facet of the FFMQ compared to those who are not married. The positive association between marital status and total mindfulness score is likely due to the factors that relate to a higher observation score on the FFMQ. For example, the FFMQ facet of nonjudgmental focus of attention on the present experience depends on the participation and regulation of observation. Therefore, we suggest that the regular and benign interactions of couples in marriage is conducive to the improvement of mindfulness level through the improvement of mindful observation.

Our results found that age independently and positively correspond with trait mindfulness level among MDD patients. Other studies have shown that nonclinical young adults have statistically greater anxiety, statistically greater experiential avoidance, and statistically lower mindfulness levels compared to nonclinical elders (52). There even appears to be a significant impact of age on benefit of mindfulness-based intervention to treat depression among adolescents (53). Age positively relates to the mindfulness aspects of present-moment attention, nonjudgment, acceptance, nonattachment, and decentralization. Nonjudgmental acceptance of present experience is an effective psychological adaptation strategy for aging individuals to reduce adverse emotional reactions caused by daily life stress (54, 55).

The association between trait mindfulness and MDD severity observed in our study might be at least in part explained by cultural influence. For example, most Chinese patients that have been newly diagnosed with cancer have low mindfulness levels and higher levels of depression (56, 57). However, it has been shown that German cancer patients have a low quality of life ranking and severe MDD, but they also have high levels of mindfulness. These results suggest that the relationship between depression and mindfulness level in the same disease state is complicated and affected by cultural factors (56, 57). Another study has shown that Western cultures compared to Eastern cultures have a stronger relationship between the trait mindfulness facet of nonjudgement and affective disorders (20). The same study revealed a stronger relationship between the trait mindfulness facet of description and affective disorders among Eastern cultures compared to Western cultures (20). Another recent study has revealed that the FMMQ suffers from conceptual and measurement shortcomings in a cross-cultural context (26). The influence of culture on mindfulness in patients with MDD warrants further investigation, especially as it relates to using the FFMQ as an assessment tool (58).

In conclusion, patients hospitalized for MDD present with various levels of trait mindfulness. Mindfulness-based therapeutic interventions have been shown to be beneficial in treating MDD. However, the efficiency of mindfulness-based therapeutic interventions is influenced by trait mindfulness level. Therefore, by monitoring trait mindfulness and identifying the independent factors that contribute to trait mindfulness, clinicians can identify MDD patients that would likely have a greater capacity to benefit from mindfulness-based therapy, more accurately establish a prognosis, and establish patient-specific mindfulness-related therapeutic targets. Furthermore, knowledge of a MDD patient’s baseline mindfulness level and their underlying factors can help ensure truly balanced clinical trial groups (59). Toward that end, we have identified that being married, being of older age, and having the perception of a good quality of life improves trait mindfulness levels via the five identified facets of mindfulness assessed by the FFMQ.

Limitations

This study was based on analysis of inpatients with MDD from a single hospital during one calendar year. Although this ensures the consistency of inpatient screening, it also limits the generalizability of the results. Additionally, attempting to establish generalizable cross-cultural conclusions should be done with caution, since there is some evidence that the FFMQ is not sensitive to cultural differences. Additionally, since data was only collected at the point of hospital admission, the data used in this study is cross-sectional. In other words, the recorded patient’s mindfulness level and MDD characteristics might only reflect an ephemeral state. Therefore, it is impossible to deduce lasting causal relationships between the factors that are related to trait mindfulness. Furthermore, our current study cannot address the effect of different trait mindfulness levels on the outcome of mindfulness therapy. This will need to be addressed in a future, well-designed randomized clinical trial. Finally, the subjects involved in this study had MDD rather than mild-to-moderate depressive disorder. Further investigation on patients with mild-to-moderate depressive disorder is required to elucidate any generalizability of this study to these populations. Therefore, our results should be validated by well-designed prospective studies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Suzhou Guangji Hospital Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

G-HW, XD, RL, M-EN, and F-ZK conceptualized and designed the study. C-FJ, G-HW, L-LL, and F-ZK collected and analyzed the data. C-FJ, G-HW, M-EN, F-ZK, XD, and RL interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. G-HW, XD, RL, and F-ZK revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

F-ZK is funded by Top-Notch Talent Foundation (GSWS2021051), Suzhou Municipal Key Supporting Disciplines in Medicine (SZFCXK202103), Suzhou Clinical Medical Center for Mood Disorders (No. Szlcyxzx202109) from Suzhou Municipal Health Commission and Scientific Research Project (SZHL-A-202203) from Suzhou Municipal Nursing Association. G-HW is funded by Top-Notch Talent Foundation of Six Types of Outstanding Personnel from Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission (LGY2019015) and Top-Notch Talent Foundation of Suzhou Municipal Health Commission (GSWS2019057). The funders have no rule in conception, design, analysis, interpretation and writing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all subjects for their participation in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Otte, C, Gold, SM, Penninx, BW, Pariante, CM, Etkin, A, Fava, M, et al. Major depressive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Prim. (2016) 2:16065. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.65

2. Abdoli, N, Salari, N, Darvishi, N, Jafarpour, S, Solaymani, M, Mohammadi, M, et al. The global prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) among the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2022) 132:1067–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.10.041

3. Feng, Y, Xiao, L, Wang, WW, Ungvari, GS, Ng, CH, Wang, G, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of depressive disorders in China: the second edition. J Affect Disord. (2019) 253:352–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.104

4. Kennedy, SH. Core symptoms of major depressive disorder: relevance to diagnosis and treatment. Dialog Clin Neurosci. (2008) 10:271–7. doi: 10.31887/dcns.2008.10.3/shkennedy

5. Serafini, G, Parisi, VM, Aguglia, A, Amerio, A, Sampogna, G, Fiorillo, A, et al. A specific inflammatory profile underlying suicide risk? Systematic review of the main literature findings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–22. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072393

6. Lu, J, Xu, X, Huang, Y, Li, T, Ma, C, Xu, G, et al. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. (2021) 8:981–09. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00251-0

7. Thornicroft, G, Chatterji, S, Evans-Lacko, S, Gruber, M, Sampson, N, Aguilar-Gaxiola, S, et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry. (2017) 210:119–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.188078

8. Serafini, G, Adavastro, G, Canepa, G, De Berardis, D, Valchera, A, Pompili, M, et al. The efficacy of buprenorphine in major depression, treatment-resistant depression and suicidal behavior: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. (2018) 19:2410. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082410

9. Kuyken, W, Hayes, R, Barrett, B, Byng, R, Dalgleish, T, Kessler, D, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2015) 386:63–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4

10. Martín-Asuero, A, and García-Banda, G. The mindfulness-based stress reduction program (MBSR) reduces stress-related psychological distress in healthcare professionals. Span J Psychol. (2010) 13:897–5. doi: 10.1017/S1138741600002547

11. Segal, ZV, Dimidjian, S, Beck, A, Boggs, JM, Vanderkruik, R, Metcalf, CA, et al. Outcomes of online mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for patients with residual depressive symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat. (2020) 77:563–3. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4693

12. Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in everyday life. 10th ed. New York, NY: Hachette Books (2005).

13. Brown, KW, and Ryan, RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2003) 84:822–8. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

14. Shen, H, Zhang, L, Li, Y, Zheng, D, Du, L, Xu, F, et al. Mindfulness-based intervention improves residual negative symptoms and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: a randomized controlled follow-up study. Psychol Med. (2021) 53:1390–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721002944

15. Teasdale, JD, Segal, ZV, Williams, JMG, Ridgewaya, VA, Soulsby, JM, and Lau, MA. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2000) 68:615–3. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.615

16. Antoine, P, Congard, A, Andreotti, E, Dauvier, B, Illy, J, and Poinsot, R. A mindfulness-based intervention: differential effects on affective and Processual evolution. Appl Psychol Heal Well-Being. (2018) 10:368–09. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12137

17. Vergara, RC, Baquedano, C, Lorca-Ponce, E, Steinebach, C, and Langer, ÁI. The impact of baseline mindfulness scores on mindfulness-based intervention outcomes: toward personalized mental health interventions. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.934614

18. Nejati, V, Zabihzadeh, A, Maleki, G, and Tehranchi, A. Mind reading and mindfulness deficits in patients with major depression disorder. Proc Soc Behav Sci. (2012) 32:431–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.065

19. Baer, RA, Smith, GT, Lykins, E, Button, D, Krietemeyer, J, Sauer, S, et al. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment. (2008) 15:329–2. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313003

20. Carpenter, JK, Conroy, K, Gomez, AF, Curren, LC, and Hofmann, SG. The relationship between trait mindfulness and affective symptoms: a meta-analysis of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ). Clin Psychol Rev. (2019) 74:101785. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101785

21. Beck, AT, Steer, RA, and Garbine, MA. Psychometric properties of the Beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. (1988) 8:77–09. doi: 10.1016/0272735888900505

22. Hubley, AM. Beck depression inventory, encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Cham: Springer (2022).

23. Cruz, LN, Camey, SA, Fleck, MP, and Polanczyk, CA. World Health Organization quality of life instrument-brief and short Form-36 in patients with coronary artery disease: do they measure similar quality of life concepts? Psychol Heal Med. (2009) 14:619–8. doi: 10.1080/13548500903111814

24. Harper, A, Power, M, Orley, J, Herrman, H, Schofield, H, Murphy, B, et al. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. (1998) 28:551–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798006667

25. Goldberg, SB, Wielgosz, J, Dahl, C, Schuyler, B, MacCoon, DS, Rosenkranz, M, et al. Does the five facet mindfulness questionnaire measure what we think it does? Construct validity evidence from an active controlled randomized clinical trial. Psychol Assess. (2016) 28:1009–14. doi: 10.1037/pas0000233

26. Karl, JA, Prado, SMM, Gračanin, A, Verhaeghen, P, Ramos, A, Mandal, SP, et al. The cross-cultural validity of the five-facet mindfulness questionnaire across 16 countries. Mindfulness. (2020) 11:1226–37. doi: 10.1007/s12671-020-01333-6

27. Schoofs, H, Hermans, D, and Raes, F. Brooding and reflection as subtypes of rumination: evidence from confirmatory factor analysis in nonclinical samples using the dutch ruminative response scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. (2010) 32:609–7. doi: 10.1007/s10862-010-9182-9

28. Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J Abnorm Psychol. (1991) 100:569–2. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569

29. Nolen-Hoeksema, S, and Morrow, J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1991) 61:115–1. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115

30. Treynor, W, Gonzalez, R, and Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Ruminative reconsiderd: a psychometric analysis. Cognit Ther Res. (2003) 27:247–9. doi: 10.1023/A:1023910315561

31. Erdur-Bakera, Ö, and Bugaya, A. The short version of ruminative response scale: reliability, validity and its relation to psychological symptoms. Proc Soc Behav Sci. (2010) 5:2178–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.433

32. Extremera, N, and Fernández-Berrocal, P. Validity and reliability of Spanish versions of the ruminative response scale-short form and the distraction responses scale in a sample of Spanish high school and college students. Psychol Rep. (2006) 98:141–09. doi: 10.2466/pr0.98.1.141-150

33. Parola, N, Zendjidjian, XY, Alessandrini, M, Baumstarck, K, Loundou, A, Fond, G, et al. Psychometric properties of the ruminative response scale-short form in a clinical sample of patients with major depressive disorder. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2017) 11:929–7. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S125730

34. Wang, C, Song, X, Lee, TMC, and Zhang, R. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the brief state rumination inventory. Front Public Heal. (2022) 10:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.824744

35. Marques, DR, Gomes, AA, and Pereira, AS. Mindfulness profiles in a sample of self-reported sleep disturbance individuals. J Context Behav Sci. (2020) 15:219–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.01.008

36. Chesin, M, and Cascardi, M. Cognitive-affective correlates of suicide ideation and attempt: mindfulness is negatively associated with suicide attempt history but not state Suicidality. Arch Suicide Res. (2019) 23:428–9. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2018.1480984

37. Baker, AW, Frumkin, MR, Hoeppner, SS, LeBlanc, NJ, Bui, E, Hofmann, SG, et al. Facets of mindfulness in adults with generalized anxiety disorder and impact of co-occurring depression. Mindfulness. (2019) 10:903–2. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-1059-0

38. Desrosiers, A, Klemanski, DH, and Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Mapping mindfulness facets onto dimensions of anxiety and depression. Behav Ther. (2013) 44:373–4. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.02.001.Mapping

39. Kuyken, W, Warren, FC, Taylor, RS, Whalley, B, Crane, C, Bondolfi, G, et al. Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse an individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials. JAMA Psychiat. (2016) 73:565–4. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0076

40. Galante, J, Friedrich, C, Dawson, AF, Modrego-Alarcón, M, Gebbing, P, Delgado-Suárez, I, et al. Mindfulness-based programmes for mental health promotion in adults in nonclinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Med. (2021) 18:1–40. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003481

41. Kingston, J, Becker, L, Woeginger, J, and Ellett, L. A randomised trial comparing a brief online delivery of mindfulness-plus-values versus values only for symptoms of depression: does baseline severity matter? J Affect Disord. (2020) 276:936–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.087

42. De Frias, CM, and Whyne, E. Stress on health-related quality of life in older adults: the protective nature of mindfulness. Aging Ment Heal. (2015) 19:201–6. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.924090

43. Elliot, AJ, Gallegos, AM, Moynihan, JA, and Chapman, BP. Associations of mindfulness with depressive symptoms and well-being in older adults: the moderating role of neuroticism. Aging Ment Heal. (2019) 23:455–09. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1423027

44. Innis, AD, Tolea, MI, and Galvin, JE. The effect of baseline patient and caregiver mindfulness on dementia outcomes. J Alzheimers Dis. (2021) 79:1345–67. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201292

45. Pleman, B, Park, M, Han, X, Price, LL, Bannuru, RR, Harvey, WF, et al. Mindfulness is associated with psychological health and moderates the impact of fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. (2019) 38:1737–45. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04436-1.Mindfulness

46. Rechenberg, K, Cousin, L, and Redwine, L. Mindfulness, anxiety symptoms, and quality of life in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2020) 35:358–3. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000630

47. Bo, Q, Tian, L, Li, F, Mao, Z, Wang, Z, Ma, X, et al. Quality of life in euthymic patients with unipolar major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2019) 15:1649–57. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S201567

48. Wachs, K, and Cordova, JV. Mindful relating: exploring mindfulness and emotion repertoires in intimate relationships. J Marital Fam Ther. (2007) 33:464–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00032.x

49. Kimmes, JG, May, RW, Seibert, GS, Jaurequi, ME, and Fincham, FD. The association between trait mindfulness and cardiovascular reactivity during marital conflict. Mindfulness. (2018) 9:1160–9. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0853-4

50. Quinn-Nilas, C. Self-reported trait mindfulness and couples’ relationship satisfaction: a Meta-analysis. Mindfulness. (2020) 11:835–8. doi: 10.1007/s12671-020-01303-y

51. Bubber, S, and Gala, J. Linking Indian yogic practices and modern marriages: role of meditation in marital wellbeing. Curr Psychol. (2022). doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02826-4

52. Mahoney, CT, Segal, DL, and Coolidge, FL. Anxiety sensitivity, experiential avoidance, and mindfulness among younger and older adults: age differences in risk factors for anxiety symptoms. Int J Aging Hum Dev. (2015) 81:217–09. doi: 10.1177/0091415015621309

53. Gómez-Odriozola, J, and Calvete, E. Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on adolescents’ depression and self-concept: the moderating role of age. J Child Fam Stud. (2021) 30:1501–15. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-01953-z

54. Mahlo, L, and Windsor, TD. Older and more mindful? Age differences in mindfulness components and well-being. Aging Ment Heal. (2021a) 25:1320–31. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1734915

55. Mahlo, L, and Windsor, TD. State mindfulness and affective well-being in the daily lives of middle-aged and older adults. Psychol Aging. (2021b) 36:642–9. doi: 10.1037/pag0000596

56. Blawath, S, Metten, R, and Tschuschke, V. Mindfulness, depression, quality of life, and cancer: the nonlinear, indirect effect of mindfulness on the quality of life of cancer patients. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. (2014) 60:337–9. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2014.60.4.337

57. Lam, KFY, Lim, HA, Kua, EH, Griva, K, and Mahendran, R. Mindfulness and Cancer patients’ emotional states: a latent profile analysis among newly diagnosed Cancer patients. Mindfulness. (2018) 9:521–3. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0794-y

58. Lecuona, O, García-Rubio, C, de Rivas, S, Moreno-Jiménez, JE, Meda-Lara, RM, and Rodríguez-Carvajal, R. A network analysis of the five facets mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ). Mindfulness. (2021) 12:2281–94. doi: 10.1007/s12671-021-01704-7

Keywords: mindfulness, depression, major depression disorder, trait mindfulness, FFMQ

Citation: Ji C-F, Wu G-H, Du XD, Wang G-X, Liu L-L, Niu M-E, Logan R and Kong F-Z (2023) Factors that contribute to trait mindfulness level among hospitalized patients with major depressive disorder. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1144989. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1144989

Edited by:

JohnBosco Chika Chukwuorji, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, NigeriaReviewed by:

Zezhi Li, Guangzhou Medical University, ChinaGianluca Serafini, San Martino Hospital (IRCCS), Italy

Holly Hazlett-Stevens, University of Nevada, Reno, United States

Copyright © 2023 Ji, Wu, Du, Wang, Liu, Niu, Logan and Kong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robert Logan, cm9iZXJ0LmxvZ2FuQGVuYy5lZHU=; Fan-Zhen Kong, a29uZ2ZhbnpoZW4wMDQzQHN1ZGEuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Cai-Fang Ji

Cai-Fang Ji Guan-Hui Wu

Guan-Hui Wu Xiang Dong Du

Xiang Dong Du Gui-Xian Wang

Gui-Xian Wang Li-Li Liu

Li-Li Liu Mei-E. Niu

Mei-E. Niu Robert Logan

Robert Logan Fan-Zhen Kong

Fan-Zhen Kong