95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 16 February 2023

Sec. Psychopathology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1098224

This article is part of the Research Topic Assessment of Psychotic Phenomena: The Focus on Clinical Utility View all 5 articles

Marina Elisabeth Huurman1

Marina Elisabeth Huurman1 Gerdina Hendrika Maria Pijnenborg2,3

Gerdina Hendrika Maria Pijnenborg2,3 Bouwina Esther Sportel3

Bouwina Esther Sportel3 Gerard David van Rijsbergen3

Gerard David van Rijsbergen3 Ilanit Hasson-Ohayon4

Ilanit Hasson-Ohayon4 Nynke Boonstra5,6,7*

Nynke Boonstra5,6,7*Background: Receiving the label of a psychotic disorder influences self-perception and may result in negative outcomes such as self-stigma and decreased self-esteem. The way the diagnosis is communicated to individuals may affect these outcomes.

Aims: This study aims to explore the experiences and needs of individuals after a first episode of psychosis with regard to the way in which information about diagnosis, treatment options and prognosis is communicated with them.

Design and methods: A descriptive interpretative phenomenological approach was used. Fifteen individuals who experienced a first episode of psychosis participated in individual semi-structured open-ended interviews on their experiences and needs regarding the process of providing information about diagnosis, treatment options and prognosis. Inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze the interviews.

Results: Four recurring themes where identified (1) timing (when); (2) content (what); and (3) the way information is provided (how). Individuals also reported that the provided information could elicit an emotional reaction, for which they would require specific attention, therefore the fourth theme is (4) reactions and feelings.

Conclusion: This study provides new insights into the experiences and specific information needed by individuals with a first episode of psychosis. Results suggest that individuals have different needs regarding the type of (what), how and when to receive information about diagnosis and treatment options. This requires a tailor-made process of communicating diagnosis. A guideline on when, how and what to inform, as well as providing personalized written information regarding the diagnosis and treatment options, is recommended.

Receiving a classification of a psychotic disorder has several implications, potentially resulting in self-stigma and decreased self-esteem (1). The way a diagnosis is communicated to individuals is central to mental health practice and has the potential to influence individuals outcomes, including treatment engagement, willingness to follow treatment recommendations, satisfaction with treatment, symptom severity, and referral to other services (2). Although there is limited literature on how and when to inform individuals after a first episode of psychosis (FEP) about their diagnosis, treatment options and prognosis; the Dutch guideline on early psychosis recommends working with a personalized diagnosis to guide treatment, while using a DSM classification for insurance purposes [e.g., (3)]. A personalized diagnosis involves a description of the formal diagnosis together with a description of personal vulnerability, triggering, maintaining and protective factors. It also includes considering how symptoms affect functioning and wellness and personal treatment options. According to the guideline, diagnosis of psychosis includes three components: an individual, a dimensional and a categorical profile (3). The individual profile maps out which factors are (or have been) influencing the onset, provocation and maintenance of the psychotic episode and what the relevant protective and vulnerable characteristics were. A dimensional profile describes the extent to which certain symptoms are present. Finally, a categorical description serves to determine whether the symptoms fall within the definition of a particular psychiatric disorder, for example a DSM 5 classification. The individual, as well as the dimensional and the categorical profile are all integrated in a personalized diagnosis that is communicated to the general practitioner through a letter. The guideline recommends that this letter should be composed in consultation with the patient.

In psychotic disorders, communication regarding diagnosis is complicated by several factors. First of all, at early stages, prognosis may be uncertain and course of illness and outcomes may vary substantially (4–6). Secondly schizophrenia and other psychosis-based diagnoses have no objective evidence (e.g., blood test, imaging) and depends on the clinical judgment of behavioral criteria, which, in addition, can be influenced by cultural biases (7, 8). Thirdly, diagnostic labels such as “schizophrenia” are heavily stigmatized (1). Considering all these factors that can affect the process of diagnosis communication, it is important to explore the subjective experience of individuals regarding the way they learned about their diagnosis and the implications of this process.

The way information on diagnosis, treatment and prognosis is communicated, can impact a person’s recall and understanding of the diagnosis, the treatment options and prognosis, and how they accept the diagnosis and treatment plan, which then ultimately can affect the process of recovery and long-term outcome (9). When information about their illness is not communicated adequately individuals may feel confused and perplexed (10). As a consequence, communicating diagnostic information relating to psychotic disorders in particular is a complex task for mental health workers (9, 10). Especially in the early phase of illness, when individuals receive information on their disorder for the first time, providing clear, comprehensive and concise information in a respectful way seems crucial.

A recent study on clinicians working in Early Intervention Services (EIS) highlights the challenges posed in discussing the diagnosis of FEP (10). Most clinicians identified a number of barriers, such as diagnostic uncertainty, stigma and the variations in outcome. Therefore, the term “psychosis” or FEP was preferred (10). Because cognitive deficits, impaired metacognition and insight can interfere with the communication and interpretation of information, the need for information on the diagnosis of FEP for those experiencing psychotic symptoms is completely different from other serious disorders (2, 10, 11). In line with the preferred term psychosis or FEP, it has been debated whether the term schizophrenia should be replaced with psychosis spectrum syndrome (12–14). It seems that health care providers are avoiding the term schizophrenia in their communication, but not in the individuals’ file, and that a diagnostic label, such as schizophrenia, may be discovered by individuals accidentally in their medical file.

There is a paucity in literature of information on the process and experiences of communicating about diagnoses that takes place in psychiatry, and, consequently, on recommendations regarding how to communicate which information and when (15). Given the plethora of research in other medical disciplines, such as oncology, pediatrics, emergency settings and neurology (16–18) it is surprising that in psychiatry, research on communicating information about a serious illness is so scarce. However, there are some studies about delivering difficult news in psychiatry showing that individuals diagnosed with mental disorders and their relatives wish, in line with their rights, to be fully informed on their diagnosis and it implications (19, 20). However, limited studies on this topic showed that individuals and their relatives have expressed dissatisfaction with the way diagnostic and related information has been shared with them in psychiatry (21, 22) and showed the need for such protocols (23). Thus, it is important to further learn on how and when to inform individuals with a first episode about their diagnosis and related information on prognosis in order to design protocols for communication about diagnoses. The current study aims to gain insight into the lived experiences and needs of individuals after FEP, regarding the process of providing information about diagnosis, treatment options and prognosis, using an interpretative phenomenological approach.

In this qualitative study, a descriptive interpretative phenomenological approach was used (24), conducting in-depth interviews to gain insight into the lived experiences, experienced of individuals, after FEP, aged above 18 years of age. In this study we aimed to understand the subjective experiences and needs regarding the process of providing information about diagnosis, treatment options and prognosis after a first episode psychosis. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, a qualitative study is best suited to help us provide unique insights and uncover unexpected findings (25).

Accordingly we conducted in depth interviews 6–12 months after the psychotic episode. This range was chosen since communicating diagnosis is part of a diagnostic process and not based on one single conversation event. In addition, at the first contact (intake), most patients are having psychotic symptoms and learning to understand symptoms in relation to its context is part of the diagnostic process which takes a few months. We were looking for the subjective experiences of patients and not for the objective situation nor for the perspective of the clinician.

The study population consisted of individuals after FEP, treated by the early intervention service (EIS) of Friesland Mental Health Care Services or the EIS of Drenthe Mental Health Care Services in the Netherlands. An EIS provides outreaching care for individuals with an early psychosis (26). A convenience sample, based on availability and willingness to participate, was assembled. All individuals from 18 to 65 years, who entered treatment for a first episode psychosis were asked by their psychiatric nurse to participate in this study between 6 and 12 months after the intake. 6–12 months was chosen because at the first contact (intake), most patients are having psychotic symptoms as this is the reason for their referral. Learning to understand symptoms in relation to its context is part of the diagnostic process and takes a few weeks or months.

The nurses asked the participants if they wanted to share their experiences about the way they were talked to about their psychiatric diagnosis and what could have been improved. Individuals with florid psychotic symptoms, according to their clinicians, were excluded from participation. After individuals had indicated that they wanted to participate in the study, they were contacted by telephone by the researcher to receive further explanation. After consent to participate, an appointment was made for an interview. Participants were interviewed once because with this in depth interview we aimed to question the participants about the whole diagnostic period. Since the focus of this study is on the first phase after intake, there was no follow up assessment. Participants were, however, asked to review the interview and add additional insights.

The experience of communicating the diagnosis was assessed by applying a semi-structured open-ended interview guide, developed by Amsalem et al. (21). It focused on individuals experiences of the way the diagnosis was communicated to them by their treating clinicians. The interview included twelve core questions and nineteen sub questions, that were used flexibly. Examples of the questions are: (1) “Can you tell me a bit about who you are?” (2) “Why do you think you are being treated here?” (3) “What have you been told about the reason why you are being treated?” (4) “How did you come to know this?” (5) “Was the information on…. sufficient, too little or too much?” (6) “What did you think of the timing of the conversation about the diagnosis?” The interviewer used an active listening style to establish rapport.

The interviews were conducted by two experienced mental health care psychologists. We used the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) checklist to make sure all of the items from the checklist were included in this qualitative research (27). All participants gave written informed consent prior to participation. The interviews were conducted online or at their local clinic, depending on the respondent’s preference. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The duration of the interviews was between 30 and 90 min. The iterative process of sampling, data collection and analysis was continued until data saturation was reached. The term “data saturation” was defined as the point in data collection and analysis when new incoming data produces little or no new information to address the research question (28). After fifteen interviews, when three further interviews had been conducted which produced no new themes, we designated this as the point of data saturation.

For this study, which was part of a larger study, the research proposal was submitted to the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre (MEC) for approval. The committee granted the approval, registered under no. NL64406.042.18. The recordings of the interviews are retained according to the international safety regulations for the storage of data at the University of Groningen and NHL Stenden University of Applied Sciences and are accessible only to the researchers.

Authors MH and NB analyzed the data and coded them independently. Transcripts were analyzed thematically, using the widely used approach of Thematic Analysis (TA) by Braun and Clark (29) to organize, encode and identify patterns within qualitative data. Braun and Clarke (28) distinguish between a top-down or theoretical thematic analysis, that is driven by the specific research question and the analyst’s focus, and a bottom-up or inductive one that is more driven by the data itself. Our analysis was driven by the research question and thus was more top-down than bottom-up. The theme that was established a priori, included individuals’ experiences and needs regarding communicating diagnosis (including treatment options and prognosis) (10, 30).

Step 1 involved listening to the audio tape whilst reading the verbatim interviews (data familiarization). Data relevant for each code were collected in step 2 (extracting significant statements). Then in step 3, we compared the codes with the formulated meaning (based on the quotes) to achieve consistency (compare and discussion). During step 4, we categorized the meanings into codes that reflect a vision to form a code (27 codes were obtained from 141 meanings which were incorporated into 4 themes). In step 5, we generated clear names for each theme. Finally, in step 6, we discussed whether the selected quotes, codes and themes all relate back to the research question. The researchers compared their results and discussed differences and agreed on a common analysis. If there would have been a disagreement a third researcher (MP) would have added to the discussion but this was not the case.

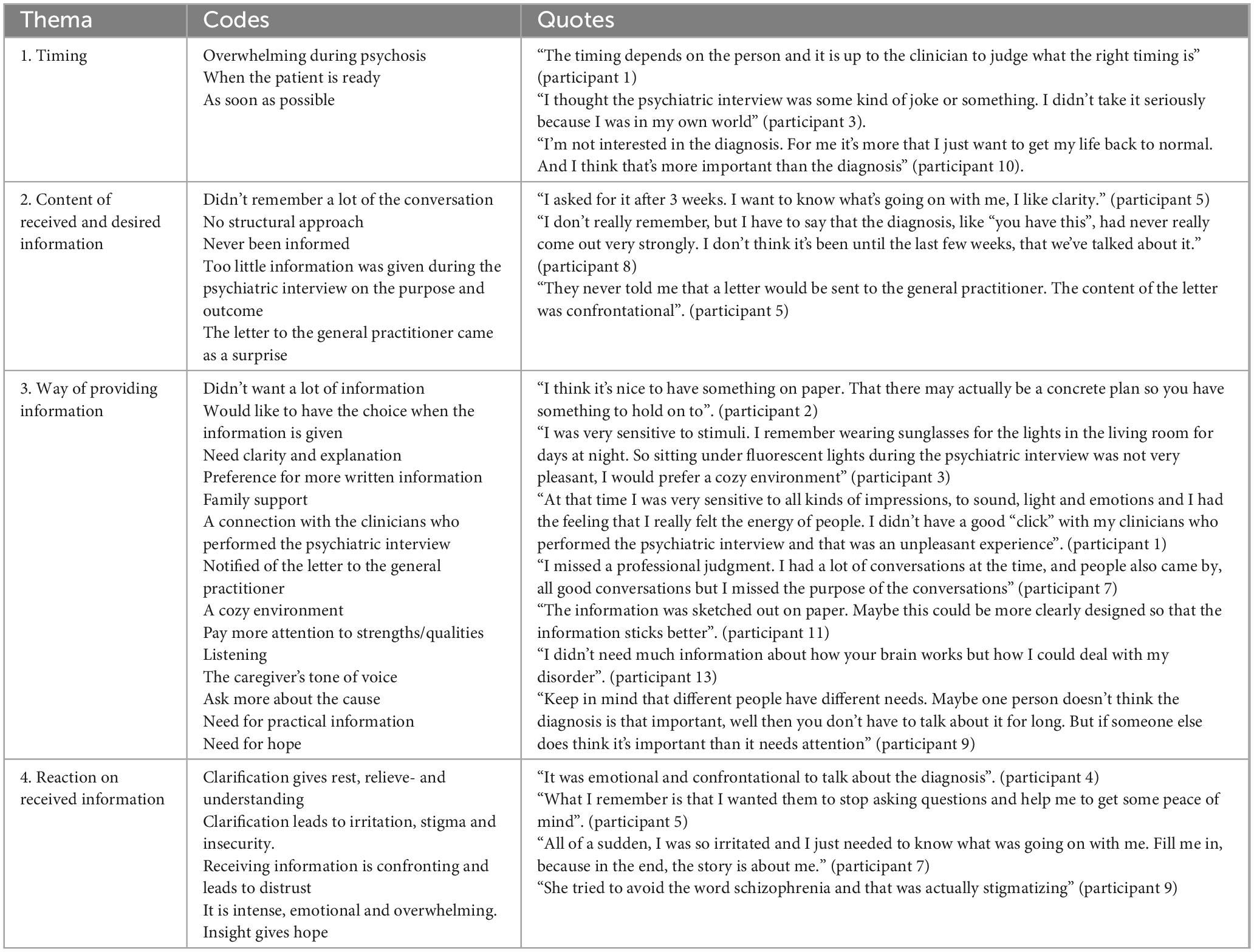

Table 2 shows the themes and codes that were identified, along with the examples of quotes illustrating them.

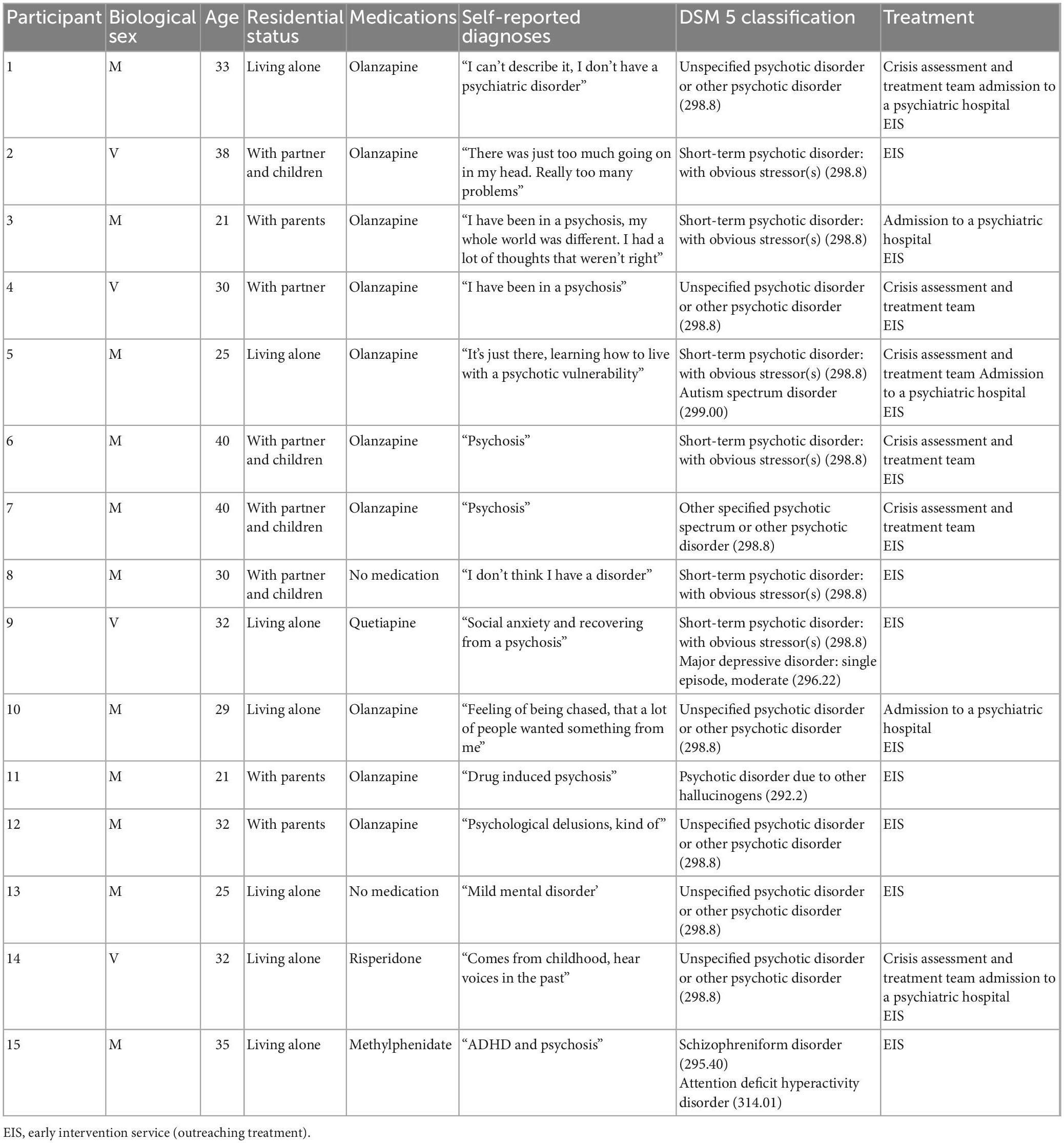

Table 1. Participant demographics, medications, self-reported diagnoses and DSM 5 classification (N = 15).

Table 2. Experiences of the communication of diagnostic information in patients after FEP: examples of the phenomenological process using thematic analysis [Braun and Clark (29)].

To ensure the criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability, a series of actions was carried out (29). We used a semi-structured interview guideline to ascertain we asked the same questions to all participants; we included a heterogeneous group with respondents as representative as possible on age, gender and residential status of the whole group of individuals with FEP; we recorded, transcribed verbatim and returned a summary of answers to obtain confirmation of the participants that the transcribed data was accurate; the analysis was carried out independently by two researchers and the total research team participated in the process of validation of the results; the characteristics of the participants were reported in detail; the findings where accompanied by quotes from the participants.

In order to achieve authenticity, every effort was made to fairly represent the experiences of the participants. A member check technique was applied to validate the findings. During the feedback sessions, individuals reported that the researchers understood their experiences correctly, indicating the information was interpreted correctly.

Fifteen individuals (11 males, 4 females) between 18 and 40 years old (M = 30.5, SD = 6.04) took part in the current study. Interviews were carried out between December 2020 and May 2021, resulting in approximately 11 h of audiotaped interviews (range: 23–72 min), transcribed in 162 pages. Table 1 presents participants’ demographics, residential status, medications, self-reported diagnoses, DSM classification according to the medical file and treatment setting(s).

During the data analysis, four themes were identified as relevant to the experiences and needs of individuals after FEP regarding the communication of diagnostic information relating to the psychotic episode: (1) timing (when); (2) content (what); and (3) the way information is provided (how).

Individuals also reported that the provided information could elicit an emotional reaction, for which they would require specific attention, therefore the fourth theme is (4) reactions and feelings. The themes are described in more detail below. Table 2 gives an example of the phenomenological process.

Individuals were asked to describe what they remembered from the conversation(s) about the diagnosis. Six individuals (40%), who had contact with crisis assessment and treatment teams or were admitted to a psychiatric hospital before they came under treatment at the early intervention service (EIS), said that they actually did not remember much of the conversations about the diagnosis, for all they knew, it might not even have taken place at all. These individuals said they were in the acute phase of psychosis at that time. They indicated that they did not need a lot of information, rather they wanted rest. When individuals came to the EIS for the initial psychiatric interview, individuals generally experienced less psychotic symptoms, they especially needed clear information about the purpose of the psychiatric interview, diagnosis, and related information on treatment options and prognosis.

“I think they have told me before, but I was psychotic at that time. I just don’t have a clear memory of it.” (participant 14)

Opinions on the timing of communication related to diagnosis, treatment options and prognosis were diverse. Ten individuals indicated that they would have preferred the information about the diagnosis at a time convenient for them, or as they said “when I was ready for it myself” (participant 5). This would have been after the most severe psychotic symptoms had disappeared. Three individuals (20%) indicated that they would have liked to have been informed about the diagnosis as soon as possible. These individuals were no longer in the acute phase at the time of admittance to the EIS. Only two individuals (13%) said that the timing of information about the psychiatric diagnosis did not matter to them. However, all individuals indicated that they would like to have had the choice whether and when they would have been informed about the diagnosis.

“That will differ from person to person, but for me, the moment that I had calmed down a bit. I wouldn’t mention the classification in the beginning, then you see the world very differently and you are still very confused. For me, it would be 3 weeks later or so, then it dawned on me, that would have been the time for me to clarify things.” (participant 5)

“I would prefer the option that if you are ready, they can provide information. Because at the moment, you may be completely lost. Then you’ve lost touch with reality.” (participant 6)

The purpose of the psychiatric interview at an Early Intervention Service, namely to come to an individual, dimensional and categorical profile, was unclear to almost everyone, except for the individuals who were referred from a crisis assessment and treatment team to the EIS. In addition, most individuals mentioned that little information on DSM 5 classification and diagnosis was provided during the psychiatric interview. Individuals reported various ways of communicating the diagnosis, no structural approach was described. Only three (20%) individuals said they received information about DSM classification during the intake phase (first three to 6 weeks) at the EIS. Other individuals received information about the DSM 5 classification at a later phase during their treatment. Three individuals (20%) reported that they had never been informed about the categorical description until their participation in the current study. Two individuals (13%) had to ask about the categorical classification explicitly, because they had not been informed.

Twelve individuals (80%) were not informed about the content of the letter that was sent to the general practitioner after the psychiatric interview. Three individuals (20%) were informed about the content of the letter. This letter contained a description of the individual, as well as the dimensional and the categorical profile, based on the psychiatric interview. The content of this letter came as a surprise for these individuals. The content was often confrontational because the information had not been shared with them before. They felt they should have been prepared for the letter. In addition, schizophrenia was often described in the letter as a differential diagnosis while they were only informed about a first episode psychosis.

“I don’t think they mentioned it during the intake.” (participant 2)

“I did not get any information during the first appointment. I was mainly asked to give a lot of information at the time and did not receive information. My partner was also asked how she looked at me. At that time, not much was shared with me. I was being questioned. I thought, why should I, there’s nothing wrong with me. I wasn’t in the mood for it at all.” (participant 7)

“It would have been nice to have been told, for example, that certain things are part of it (the disorder) and that these experiences are normal. You need the confirmation that you are not going crazy, I kind of missed that. I thought I was going insane.” (participant 5)

About half of the individuals (n = 7, 46%) indicated that they would have liked more written information so they could reread it and did not have to retrieve it from memory, since they did not fully trust their memories. Individuals indicated that they were satisfied with the treatment, however, that the reason for treatment was not always clearly communicated to them. They all needed clear information but the needs in amount of information and when it should be given were all different.

“What I needed at the time, was a piece of paper about what was wrong with me. That I just got a letter saying what’s wrong with me. I haven’t seen any of these.” (participant 3)

“I would have liked more treatment options and things on paper, I like to have an overview.” (participant 7)

All individuals described that they would have liked additional information and support from their mental health care worker, like family support, practical support, more attention to causes and more attention to personal strengths and qualities. The connection with the clinicians who conducted the psychiatric interview was deemed an important factor, as well as the tone of voice used to provide the information. Two individuals (13%) would have preferred a more homely atmosphere with dimmed lighting, because they were so sensitive to stimuli. Three individuals (20%) described that they found the presence of family during the psychiatric interview very important.

The majority of individuals (n = 8, 53%) indicated that it was a very intense experience to be informed that they had a first episode psychosis and they often experienced negative associations with this term. However, most individuals (n = 13, 86%) also indicated that, despite the fact that the conversation about the diagnosis was confrontational, they liked to receive clarity because it provided rest, relief and understanding. Others said that this clarity resulted in irritation, stigma and insecurity. One of the individuals reported a lack of clarity as stigmatizing. Of the twelve individuals (80%) who had received a DSM 5 classification, nine of them agreed with the label. They reported that when they calmed down, over time, it was easier for them to accept the diagnosis. They became calmer after the medication started working and their sleep improved. The reaction of individuals loved ones played an important role in the acceptance of the diagnosis.

“That was shocking, a schizophrenic disorder sounds more intense than a psychosis.” (participant 4)

“It was confronting but I like clarity the most.” (participant 5)

“Well, I think psychosis is a strong word. Then you think, I’m not mentally well, so uhm. yes. I thought that was quite intense. That I would be mentally ill, and that obviously doesn’t fit in the life I lead, with a busy job and a busy family.” (participant 7)

Ten individuals (67%) reported that they were satisfied with the overall diagnostic and treatment process. During treatment, clinicians were said to only have paid attention to reactions on diagnostic information when individuals brought it up for discussion. Individuals reported that they experienced no initiative from clinicians to talk about emotions regarding the diagnostic information they had just received.

“I found a bit of peace when a diagnosis was made. I could then let go of a kind of struggle and I no longer went looking for what could actually be going on.” (participant 5)

“It was confronting, but I needed the clarity. I just wanted to know where I stood. Even if that is confronting, I just needed to know the facts, because that means the most to me.” (participant 9)

“The diagnosis gave me peace of mind, I am not crazy, I am not the only one.” (participant 10)

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the experiences and preferences of individuals in early intervention services, related to receiving the diagnosis of a FEP. Participants reported that timing (when), content (what) and the way information is given (how) was important for them. The specific needs in that respect varied from person to person. Individuals did, however, report that they experienced no initiative from clinicians to talk about their reaction to the diagnosis. Individuals were informed in different ways and at different times about their diagnosis, although some of them were informed not at all about their diagnosis and treatment options, or they could not remember what kind of information was provided. Participants also reported a lack of written information and none of the participants received a document regarding their diagnosis that was subsequently discussed with them by the professional.

Participants who received a psychotic spectrum diagnosis indicated that, after the start of the treatment, they first wanted some rest to clear their mind before receiving further information on their condition. Participants reported a different need during the acute phase and the phase in which acute symptoms reduced in intensity. Individuals in the acute phase, often treated by a crisis assessment and treatment team, could not remember much of the information they received about the diagnosis. At such times, they especially needed rest and were not able to process a lot of information. As established in Leonhardt et al. (31) metacognition and insight during the acute phase might have interfered communication.

Once the acute phase was in early remission and individuals were referred to the EIS, almost every participants (n = 13) had wanted to have received more information about the diagnosis, some of them preferably in writing. This corresponds with previous research, suggesting individuals with psychosis prefer an individual descriptive diagnosis, in writing, no matter how negative, to the alternative of struggling with uncertainty and unclarity (19, 32, 33).

Participants indicated that, at the time of receiving the information, they became demoralized by the information and therefore sometimes wanted to hold it off. Caregivers may consider motivational interventions, like motivational interviewing, in order to motivate their patients to talk about diagnosis and treatment options (33). Almost all participants who were treated by one of the EIS reported that receiving information about the diagnosis was important to them. Participants reported various ways in which the diagnosis was communicated, however, the tone, feeling a connection and non-verbal communication were deemed important. Our findings are in line with the findings of Milton and Mullan, who highlighted that transparent information sharing, conveying hopeful information, utilizing collaborative approaches and actively addressing stigma are vital to the diagnostic communication process (10, 34, 35).

We found that the main barrier for withholding the diagnosis schizophrenia is the stigma attached to the term “schizophrenia.” Participants in our study mentioned stigma as an important factor as well, although they also reported experiencing stigma from the professional who would withhold information. The second most important barrier reported by Farooq et al. (10, 35) was the fear that informing individuals about this diagnosis could be harmful to the individuals. This fear was felt by individuals and gave them the feeling it was serious. The third reported barrier for lack of guidance in mental health on how to communicate diagnosis in individuals with schizophrenia also applied in our sample: participants mentioned that there was no (structured) approach whatsoever, as a consequence whereof they often received information about their diagnosis coincidentally or even had to actively request it.

The current research shows that individuals actually need clarity, even if it is confrontational. They would like to have a choice when to be informed, because that preferred moment is different for everyone. The lack of metacognition (not knowing when you are ready) might interfere in this respect, as individuals might be able to indicate afterward that they would have liked to have known more, however, during the psychotic episode they might have been reluctant. In other words: it sometimes seems easier to assess when information would have been due in retrospect than when someone is in the process. This requires clinicians to repeat their information offers and keep tuning in on information needs, which we realize is a challenge for clinical practice. This research shows the importance of offering clarity through shared decision-making. Shared decision-making requires that sharing information with the individuals and their relatives about the diagnosis and outcome is part of treatment planning, based on open and honest communication about the diagnosis and outcome and about the uncertainties in the present state of knowledge (35). Engaging in shared decision-making (SDM) has been recently recognized as an integral strategy for helping individuals with serious mental illnesses choose the best treatment for them, increase adherence to their treatment decision and improve mental health outcomes (36, 37). The study of Hamman et al. (35) showed that individuals with schizophrenia have a slightly stronger preference for SDM than primary care individuals. Among those with schizophrenia, younger individuals and those with more negative views on medication want more participation. This might also apply to individuals with FEP. Despite the proliferating development of SDM interventions, SDM implementation for individuals with serious mental illness has not been successfully implemented everywhere. This has to do with sufficient workforce, leadership and financial circumstance in a department (38). Zisman-Illani et al. (39) offer a new conceptualization, shared risk-taking, as a unique way to view SDM with individuals with serious mental illness. They argue that risks are an inevitable part of the SDM process and are not only related to the decision at hand. Furthermore, they argue that joint reflection by the clinician and patient should be used to address SDM-related risks (40). Also (online/mobile) health interventions are developed to improve SDM (41).

Most participants were eventually, later on in the treatment, informed about treatment options and prognosis regarding the psychosis. The fact that psychosis is not a diagnostic category in classification systems such as DSM 5 poses the problem that individuals accidentally discovered another diagnostic label, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder with psychotic features, via the letter that is sent to the general practitioner. Our study shows that only one of the individuals were informed about what was communicated to their general practitioner. This may create confusion, as the professional diagnostical terminology may be confrontational if read without further detailed explanation. SDM regarding the sharing of the information also seems important and may actually contribute to reducing stigma. It is unclear why care providers do not discuss the contents of the letter with their patient before sending it to the general practitioner. To investigate this, interviews with caregivers should be conducted.

Only few protocols have been developed to facilitate the challenging process of information disclosure, one of the best known and most elaborate is the SPIKES protocol (42). The principles in this protocol align with the principles that are important in breaking bad news according to a recently conducted systematic literature review: emotional support; what and how much information to provide; manner of communicating news; and setting (43). The SPIKES protocol includes six steps for breaking bad news: (1) setting up the interview, (2) assessing the patient’s perception, (3) obtaining the patient’s Invitation, (4) giving knowledge and information to the patient, (5) addressing the patient’s emotions with empathic responses and (6) providing a strategy and summary of treatment options and future plans (42). SPIKES was originally used in oncology but gradually adapted to other fields of medicine (42). Previous studies have identified the absence of specific guidelines for sharing difficult news in psychiatry (22) and showed the need for such protocols (23), yet the SPIKES model had not been empirically studied in FEP.

A in 2014 published qualitative study showed that psychiatrists in Israel experienced disclosure as problematic, unproductive and harmful (17). Factors as the uncertainty on the course and disclosure as a threat to a positive therapeutic alliance retain clinicians to give disclosure. This endorses the importance of working out a personalized diagnosis (in close consultation) with the individual and not focusing on the psychiatric label.

Participants views of what constitutes good communication during the diagnostic discussions were found to correspond to the stepwise framework of the SPIKES protocol (42): giving Knowledge (step 4) and information to the individuals, addressing the individuals Emotions (step 5) with empathic responses and Strategy and Summary (step 6). This last principle, Strategy and Summary, requires that the information is summarized and repeated and that the individuals is given an opportunity to voice any concerns or questions, especially given potential memory relapses. The clinicians and their patient should leave the conversation with a clear plan and time schedule for the next steps that need to be taken and the roles both will play in taking those steps. The SPIKES protocol could be a useful guide to initial diagnostic discussions; however, it probably needs some expansion/specifications to be appropriate for a mental health context, especially since communication of diagnostic information may be delivered over a number of support sessions, depending on the individual’s needs and memory capacities, and because stigma-related issues may need specific interventions, potentially also with loved ones, as a number of individuals indicated that their acceptance was important to their own acceptance. The reactions to diagnostic information vary between individuals. Therefore, an individualized personalized approach to provide diagnostic information is required.

Considering the current study results, a few limitations should be mentioned. This study was carried out with a small sample size of eleven men (73%) and four (27%) women. Although the sex distribution is not equal, it is comparable to the sex ratio in psychotic disorders (44). Cocchi et al. (44) have found that incident rates (cases per 100,000 per year) are consistently higher for males (median: 15.0) than for females (10.0), with a median rate ratio of 1.4. The fact that some participants (n = 6) had recently come out of the acute phase is informative. The qualitative design ensures that we collected rich experiences that, due to the limited respondent group, are not necessarily generalizable to the large group of people with first psychosis. Also, a qualitative design has a higher probability of researcher bias. We took this into account by having two researchers conducting the analysis, discussing the analysis in the whole research group, doing a member check and always backing up the results with quotes.

Thus, it is recommended to carry out additional studies involving more participants and encompassing different phases of a psychosis to gain detailed knowledge as to who needs what in which phase. Our study is retrospective and the primary disadvantage of this study design that it is possible that some respondents had difficulty remembering the first stage of treatment in which the diagnosis may have been discussed. It is indeed informative that they apparently remember little, which is an argument for repetition of the information after some time. This study is a two-center study in the north of the Netherlands and replication of this study in a multiple-center design with a comparable population is suggested. Nevertheless, this research has given new insights into the experiences and needs of individuals and research can be continued.

With these limitations in mind, this study has important implications for future research and for the development of guidelines in this area. Moran et al. (45) showed that psychiatrists found the disclosure of schizophrenia problematic, unproductive, and harmful (45). In our study we found that participants experienced the information as intense. Yet most participants still wanted the classification and withholding it was experienced as stigmatizing. It would be interesting to conduct a qualitative study with clinicians on experiences and barriers related to shared decision making to learn more about the reasons why we don’t ask our patients what they prefer regarding communicating diagnosis.

We also recommend EIS to develop guidelines to take the wishes and needs of individuals seriously and to really connect with the individual process of the individual with a first episode psychosis where information is provided at the right time, in the most appropriate way. These guidelines should cover the following aspects: when to provide information (addressing the moment of providing the patient’s diagnosis), what to provide (a providing a clarifying, tailor-made, descriptive diagnosis to formulate a personal narrative) and how to provide information to the patient and their loved ones (attitude and the way information is provided, e.g., providing the information in multiple ways: in a discussion and in writing). Furthermore, these guidelines should address how to pay attention to any emotional responses of the patient and/or their loved ones to the information.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University Medical Center Groningen. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

NB, GP, and IH-O conducted the design of the study. MH conducted the research under supervision of NB, GP, and IH-O with assistance of BS and GR. NB and MH drafted the manuscript. NB, GP, IH-O, MH, BS, and GR constructed the design and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We would like to thank the participants and students who participated in this study and Boudien van der Pol at KieN VIP Mental Health Care Services for her help in supporting participants before and after the data collection. We would also like to thank Jeanique la Faille for her support in data collection at Drenthe Mental Health Care institute.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Ben-Zeev D, Young M, Corrigan PW. DSM-V and the stigma of mental illness. J Ment Health. (2010) 19:318–27. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2010.492484

2. McCabe R, Priebe S. Communication and psychosis: it’s good to talk, but how? Br J Psychiatry. (2008). 192:404–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048678

3. Veling W, Boonstra N, van Doorn H, van der Gaag M, Gijsman M, de Haan L., et al. EBRO Module Vroege Psychose. Utrecht: GGZ Standaarden (2017).

4. Singh SP, Croudace T, Amin S, Kwiecinski R, Medley I, Jones PB, et al. Three-year outcome of first-episode psychoses in an established community psychiatric service. Br J Psychiatry. (2000) 176:210–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.3.210

5. Amin S, Singh SP, Brewin J, Jones OB, Medley I, Harrison G Diagnostic stability of first-episode psychosis. comparison of ICD-10 and DSM-III-R systems. Br J Psychiatry. (1999) 175:535–43. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.6.537

6. Fusar-Poli P, McGorry PD, Kane JM. Improving outcomes of first-episode psychosis. World Psychiatry. (2017) 16:251–65. doi: 10.1002/wps.20446

7. Lawrie SM, Olabi B, Hall J, McIntosh AM. Do we have any solid evidence of clinical utility about the pathophysiology of schizophrenia? World Psychiatry. (2011) 10:19–31. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00004.x

8. Alarcón RD. Culture, cultural factors and psychiatric diagnosis: review and projections. World Psychiatry. (2009) 8:131–9. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00233.x

9. Cleary M, Hunt GE, Escott P, Walter G. Receiving difficult news: views of patients in an inpatient setting. J Psychosoc Nurs Mental Health Serv. (2010) 48:40–8. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20100504-01

10. Farooq S, Green DJ, Singh SP. Sharing information about diagnosis and outcome of first-episode psychosis in patients presenting to early intervention services. Early Intervent Psychiatry. (2018) 13:657–6. doi: 10.1111/eip.12670

11. McCabe R, John P, Dooley J, Healey P, Cushing A, Kingdon D, Priebe S. Training to enhance psychiatrist communication with patients with psychosis: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. (2016) 209:517–24. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.179499

13. Lasalvia A, Penta E, Sartorius N, Henderson S. Should the name ‘schizophrenia’ be abandoned? Schizophrenia Res. (2015) 162:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.01.031

14. Farooq S, Johal RK, Ziff C, Naeem F. Different communication strategies for disclosing a diagnosis of schizophrenia and related disorders. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. (2017) 24:10. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011707.pub2

15. Cleary M, Hunt GE, Horsfall J. Delivering difficult news in psychiatric settings. Harv Rev Psychiatry. (2009) 17:315–21. doi: 10.3109/10673220903271780

16. Fallowfield F, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. (2004) 363:312–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15392-5

17. Karnieli-Miller O, Werner P, Aharon-Peretz J, Eidelman S. Dilemmas in the (un) veiling of the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: walking an ethical and professional tight rope. Patient Educ Couns. (2007) 67:307–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.014

18. Jiang Y, Li J, Liu C, Huang M, Zhou L, Li M. Different attitudes of oncology clinicians toward truth telling of different stages of cancer. Supp Care Cancer. (2006) 14:1119–25. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0071-4

19. Fisher M. Telling patients with schizophrenia their diagnosis. patients expect a diagnosis. Br Med J. (2000) 321:385.

20. Clafferty RA, McCabe E, Brown KW. Conspiracy of silence? telling patients with schizophrenia their diagnosis. Psychiatr Bull. (2001) 25:336–9. doi: 10.1192/pb.25.9.336

21. Amsalem D, Hasson-Ohayon I, Gothelf D, Roe D. How do patients with schizophrenia and their families learn about the diagnosis. Psychiatry. (2018). 81:283–7. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2018.1443676

22. Seeman MV. Breaking bad news: schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Pract. (2010) 16:269–76. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000386915.62311.4d

23. Milton AC, Mullan B. Views and experience of communication when receiving a serious mental health diagnosis: satisfaction levels, communication preferences, and acceptability of the SPIKES protocol. J Ment Health. (2017) 26:395–404. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2016.1207225

24. Matua G, Van Der Wal D. Differentiating between descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches. Nurse Res. (2015) 22:22–7. doi: 10.7748/nr.22.6.22.e1344

25. Rich M, Ginsburg K. The reason and rhyme of qualitative research: why, when, and how to use qualitative methods in the study of adolescent health. J Adolesc Health. (1999) 25:371–8. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00068-3

26. Csillag C, Nordentoft M, Mizuno M, Jones PB, Killackey E, Taylor M. Early intervention services in psychosis: from evidence to wide implementation. Early Intervent Psychiatry. (2016) 10:540–6. doi: 10.1111/eip.12279

27. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

28. Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, Glidewell L, Entwistle V, Eccles MP, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. (2010) 25:1229–45. doi: 10.1080/08870440903194015

29. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

30. Welsh P, Brown S. ‘I’m not insane, my mother had me tested’: the risk and benefits of being labelled ‘at-risk’ for psychosis. Health Risk Soc. (2013) 15:648–62. doi: 10.1080/13698575.2013.848846

31. Leonhardt BJL, Bartolomeo LA, Visco A, Hetrick WP, Bolbecker AR, Breier A., et al. Relationship of metacognition and insight to neural synchronization and cognitive function in early phase psychosis. Clin EEG Neurosci. (2020). 51:259–66. doi: 10.1177/1550059419857971

32. Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Malagone C, Del Vecchio H, Maj M. User’s opinions questionnaire working group. views of persons with schizophrenia on their own disorder: an Italian participatory study. Psychiatric Serv. (2008) 59:795–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.7.795

33. Scheinder B, Scissons H, Arney L, Benson G, Derry J, Lucas K., et al. Communication between people with schizophrenia and their medical professionals: a participatory research project. Qual Health Res. (2004) 14:562–77. doi: 10.1177/1049732303262423

34. Milton AC, Mullan BA. Diagnosis telling in people with psychosis. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2014) 27:302–7. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000072

35. Hamann J, Langer B, Winkler V, Busch R, Cohen R, Leucht S, Kissling W. Shared decision making for in-patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scand. (2006) 114:265–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00798.x

36. Duncan E, Best C, Hagen S. Shared decision making interventions for people with mental health conditions. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. (2010) 2010:CD007297. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007297.pub2

37. Storm M, Husebø AML, Thomas EC, Elwyn G, Zisman-Ilani Y. Coordinating mental health services for people with serious mental illness: a scoping review of transitions from psychiatric hospital to community. Administration Policy Mental Health. (2019) 46:352–67. doi: 10.1007/s10488-018-00918-7

38. Bello I, Lee R, Malinovsky I, Watkins L, Nossel I, Smith T, Ngo H. OnTrackNY: the development of a coordinated specialty care program for individuals experiencing early psychosis. Psychiatr Serv. 2017 68:318–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600512

39. Zisman-Ilani Y, Lysaker PH, Hasson-Ohayon I. Shared risk taking: shared decision making in serious mental illness. Psychiatric Serv. (2021) 72:461–3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000156

40. Lincoln Y, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage (1985). doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

41. Stefancic A, Rogers R, Styke S, Xu X, Buchsbaum R, Nossel I, et al. Development of the first episode digital monitoring mhealth intervention for people with early psychosis: qualitative interview study with clinicians. JMIR Ment Health. (2022) 9:e41482. doi: 10.2196/41482

42. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. (2000). 5:302–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302

43. Fujimori M, Uchitomi Y. Preferences of cancer patients regarding communication of bad news: a systematic literature review. Jpn J Clin Oncol. (2009) 39:201–16. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn159

44. Cocchi A, Lora A, Meneghelli A, La Greca E, Pisano A, Cascio MT, et al. Sex differences in first-episode psychosis and in people at ultra-high risk Psychiatry Res. (2014). 215:314–22. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.11.023

Keywords: psychosis, communicating, stigma, needs, individual’s perception

Citation: Huurman ME, Pijnenborg GHM, Sportel BE, van Rijsbergen GD, Hasson-Ohayon I and Boonstra N (2023) Communicating diagnoses to individuals with a first episode psychosis: A qualitative study of individuals perspectives. Front. Psychiatry 14:1098224. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1098224

Received: 14 November 2022; Accepted: 30 January 2023;

Published: 16 February 2023.

Edited by:

Arjen Noordhof, University of Amsterdam, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Katrine Schepelern Johansen, Competence Centre for Dual Diagnosis, DenmarkCopyright © 2023 Huurman, Pijnenborg, Sportel, van Rijsbergen, Hasson-Ohayon and Boonstra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nynke Boonstra,  bnlua2UuYm9vbnN0cmFAbmhsc3RlbmRlbi5jb20=

bnlua2UuYm9vbnN0cmFAbmhsc3RlbmRlbi5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.