- 1Institute of Medical Sociology, Interdisciplinary Center of Health Sciences, Medical Faculty, Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle (Saale), Germany

- 2Faculty of Applied Social Sciences, University of Applied Sciences Erfurt, Erfurt, Germany

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Psychosomatics, University Hospital Halle, Halle (Saale), Germany

Background: Hypersexual and hyposexual behaviors are common concomitant of substance use disorders (SUD). On the one hand, the regular consumption of alcohol or illegal drugs can lead to hypersexual or hyposexual behavior due to its effects on the organism; on the other hand, the use of psychotropic substances is also used as a coping strategy concerning already existing sexual impairments. The aforementioned disorders show similarities in terms of their etiology, as traumatic experiences get special attention as potential risk factors for the development of addictions, hypersexual, and hyposexual behavior.

Objectives: The study aims to explore the association between SUD characteristics and hypersexual/hyposexual behavior, and a potential moderating effect of early traumatic life events by answering the following research questions: (1) Do people with SUD differ from a sample of people with other psychiatric disorders regarding hypersexual and hyposexual behavior? (2) What are the associations between the presence of sexual problems and different characteristics of the SUD (e.g., mono vs. polysubstance use, type of addictive substance, intensity of the disorder)? (3) What influence do traumatic experiences in childhood and adolescence have on the existence of sexual disorders among adults with a diagnosed SUD?

Method: The target group of this cross-sectional ex-post-facto study comprises adults diagnosed with an alcohol- and/or substance use disorder. Data will be collected with an online survey, which will be promoted via several support and networking services for people diagnosed with SUD. Two control groups will be surveyed, one consisting of people with other psychiatric disorders than SUD and traumatic experiences, and one healthy group. Relations between the dependent variables (hypersexual and hyposexual behavior) and independent variables (sociodemographic information, medical and psychiatric status, intensity of the prevalent SUD, traumatic experiences, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder) will be initially calculated via correlations and linear regression. Risk factors will be identified via multivariate regression.

Discussion: Gaining relevant knowledge promises new perspectives for prevention, diagnosis, case conception, and therapy of SUDs as well as problematic sexual behaviors. The results can provide more information about the importance of psychosexual impairments regarding the development and maintenance of SUDs.

1. Introduction

Because of its effect on the organism the regular consumption of drugs can strongly influence the level of sexual activity. The harmful use and addiction due to alcohol or illicit drugs can have both excitatory and inhibiting effects on sexual behavior (1). In relevant literature, three possible domains on the relation between alcohol or drug use, and sexual behavior are considered: (a) the use of substances to enhance sexual activity or arousal, (b) the relation between substance use and harmful or risky sexual behavior, and (c) sexual dysfunction as a consequence of substance consumption (2, 3). Thus, the consumption of, e.g., alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, or hallucinogen substances can increase sexual arousal short-termly, while the long-term use of, e.g., alcohol, opioids, or sedatives is often associated with impairments in sexual function (1). Consequently, two poles of sexual behavior can be of interest from a psychiatric perspective: hypersexual (an extraordinarily high level of sexual activity and arousal) and hyposexual behavior (an extraordinarily low level of sexual activity and arousal). At the same time, the influence of traumatic experiences in the life course plays an important role regarding the etiology of addictive disorders, as well as hypersexual and hyposexual behaviors. However, the complex linking system between prevalent SUDs, hypersexual and hyposexual behavior, as well as traumatic experiences has not been explored sufficiently, which comprises the general aim of this study. In the following, previous research on the associations between the respective factors is described.

1.1. Hypersexual behavior and substance-related addiction

Clinical relevant hypersexual behavior is classified as compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD; 6C72) in the ICD-11 (4). It is characterized by “[…] a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges resulting in repetitive sexual behavior. Symptoms may include repetitive sexual activities becoming a central focus of the person’s life” (4). Possible consequences are the neglect of important relationships, activities, and responsibilities, as well as the resulting impairments in familial, social, professional, educational, or other important areas of life (5). The prevalence of hypersexual behavior varies between 1% and around 10%, thus these estimations should be interpreted with caution (6). Since the diagnosis of CSBD was first implemented in ICD-11 in 2022, in previous research varying definitions and scales for measuring hypersexual behavior were used, so their results are not comparable in most cases (6). Several studies investigated the associations between a prevalent SUD/substance consumption and hypersexuality. In the following presentation of the current state of related research, differing aspects of hypersexuality were examined, while it is necessary to extinct between the constructs hypersexual behavior (defining subclinical behavioral deviations) and CSBD (referring to the diagnosis according to ICD-11).

Among people with SUDs, the prevalence of hypersexual behavior is estimated at around 40% and therefore significantly higher compared to those without SUD (7). Alcohol dependence was found in about 16%, and risky use of alcohol in 44% of respondents diagnosed with CSBD (4). Furthermore, positive associations were identified between the severity of substance dependence and the intensity of hypersexual behaviors in people diagnosed with cocaine or crack dependence (8). But also a risky use, especially of alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine was associated with clinically relevant hypersexual behaviors (9). Further studies indicated that both the prevalence and the expression of hypersexual behavior as a comorbidity to dependence diseases differ according to the type of addictive substance, meaning that the risk to develop hypersexual behavior seems to be significantly higher in people with poly-drug addiction than in people with isolated dependence (8). CSBD is considered both a gateway addiction and a surrogating addiction during the treatment of SUDs (10). The targeted use of drugs to evoke specific physical and/or psychological effects during sexual activity (e.g., expanding sexual performance or achieving sexual disinhibition) also plays a role in this context (11). This behavior, defined as chemsex, is associated with sexual risk behaviors (12, 13), infection with sexually transmitted diseases (12, 14, 15), impairments in social functioning (16), the secondary development of psychosis, and the resulting perception of sex without drug influence as emotionless or non-exciting (11). Further, MSM who practice chemsex report significantly higher incidences of non-consensual sex (16).

1.2. Hyposexual behavior and substance-related addiction

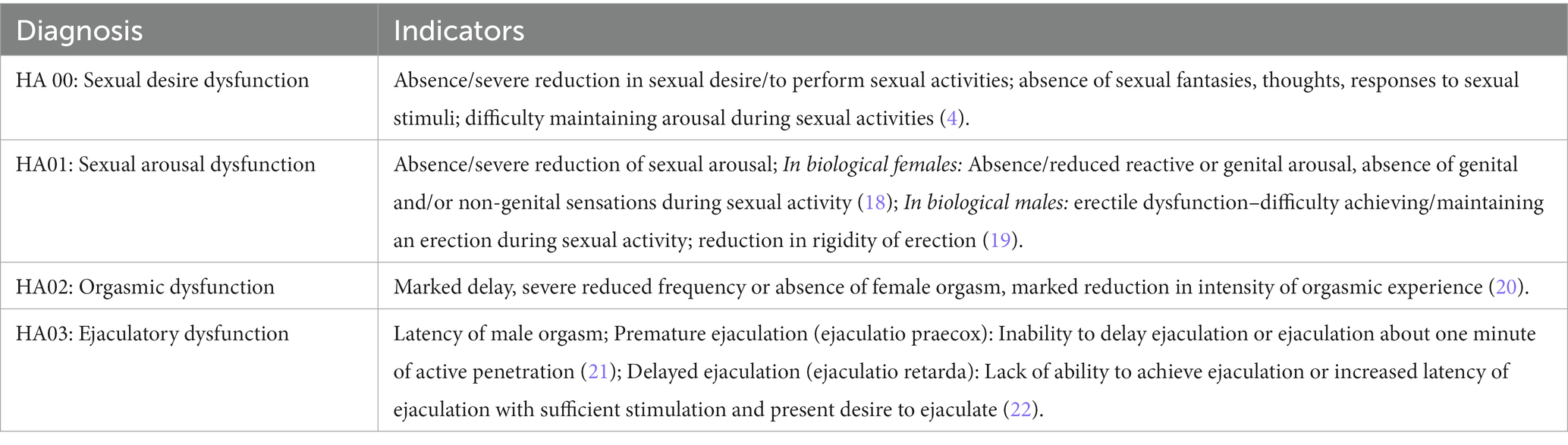

Conversely, sexual dysfunction is also known to be a possible concomitant of SUDs as well as the abuse of alcohol and illegal substances. According to ICD-11, sexual dysfunction is classified in the chapter conditions related to sexual health (HA00 to HA03) (4, 17). A distinction is made between hypoactive sexual desire dysfunction (HA00), sexual arousal dysfunction (HA01), orgasmic dysfunction (HA02), and ejaculatory dysfunction (HA03). Corresponding diagnoses are assigned if the symptoms persist or recur over a longer period of time and there is subjective suffering due to the complaints (4). The forms of sexual dysfunction are characterized in more detail in Table 1.

It is important to distinguish between sexual disorders (which require treatment) and subclinical sexual functioning problems (23). These subclinical sexual functioning problems (also called hyposexual behaviors) include individual symptoms of the disorders described above, without completely fulfilling the diagnosis (e.g., if there is no psychological strain regarding the sexual activity). However, individual complaints, e.g., with regard to one’s own body image (e.g., due to severe penile curvature or general dissatisfaction with one’s own body) or sexual performance (e.g., fear of failure, sexual inhibitions) can also lead to insecurities and limited sexual activity (24).

Sexual dysfunction can persist long after abstinence from alcohol or drugs. Possible reasons for that are changes in hormone balance and neuronal structures (25). Particularly prominent seems to be the association between alcohol dependence and the existence of sexual dysfunctions, since it has already been highlighted in numerous studies (26–28), with the prevalence of sexual dysfunctions ranging from around 29% (26) to 58% (29). In particular, dyspareuinia (vaginal pain during penetration) and vaginal dryness (absence of vaginal lubrication) in women (27) and erectile dysfunction, ejaculatio praecox, and reduced sexual desire in men (27–29) have been identified as comparatively common disorders in people with SUDs. Moreover, associations with sexual dysfunction have also been reported in addiction due to illegal substances, as in addiction to opioids (esp. heroin, methadone, and buprenophine) (27, 30), crack (37.2%), cocaine (20.6%), and marijuana (6.3%) (26). In addition, a study by Dolatshahi et al. (31) could identify associations between methamphetamine abuse and sexual dysfunction in men. Thus, single use of methamphetamines appears to lead to increased duration, quantity, and subjectively perceived quality of sexual activity. However, with increasing time or repetition of use, associations with decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, and ejaculatio praecox become conspicuous, with consumption-induced cognitive changes as possible explanations (31).

1.3. Relevance of traumatic experiences

The influence of traumatic experiences in the life course plays an important role regarding the etiology of addictive disorders, as well as hypersexual and hyposexual behaviors. In this context, traumatic experiences represent a risk factor for the development of addictive disorders (32), as well as hypersexual and hyposexual behaviors (33). In particular, associated dysfunctional family structures, breaches of trust with important attachment figures, and experiences of violence have been identified as important risk factors (34). Trauma in childhood and adolescence was reported by up to 70% of people with substance-related addiction (32). In addition, the diagnoses of substance use disorder and disorders specifically associated with stress often occur simultaneously (25), and addiction disorders may develop as a consequence of prevalent post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), especially when substance use is utilized as a strategy to cope with the symptoms associated with PTSD (35). Trauma in childhood and adolescence is also associated with an increased likelihood of relapse into alcohol addiction (36).

Moreover, hypersexual and hyposexual behavior are considered frequent psychosocial consequences of experienced violence in the relevant literature (34, 37, 38). A distinction is made between sexual-related consequences of sexual and non-sexual traumatic experiences (39). Sexual dysfunctions in combination with intrusive and/or dissociative experiences as well as accompanying psychological and/or physical stress reactions during sexual activities are particularly common (hence the term sexual PTSD is used in relevant literature) (40). Furthermore, hypersexual behavior is described as a possible post-traumatic stress reaction, which can express by reduced bonding ability and reduced self-reduction as well as (resulting) sexual risk behavior (41). However, the linking between traumatic experiences and behavioral addictions, such as CSBD, is considered under-researched. The few available studies, however, focused on other specific target groups than in this study. For example, the results of a study by Davis and Knight (42) were able to show an association between traumatic experiences in childhood and adolescence and the presence of hypersexual behavior in male sexual offenders. In another study by Castellini et al. (43), a corresponding association was found in female students but not in male students.

1.4. Theoretical bundling and deduction of objectives

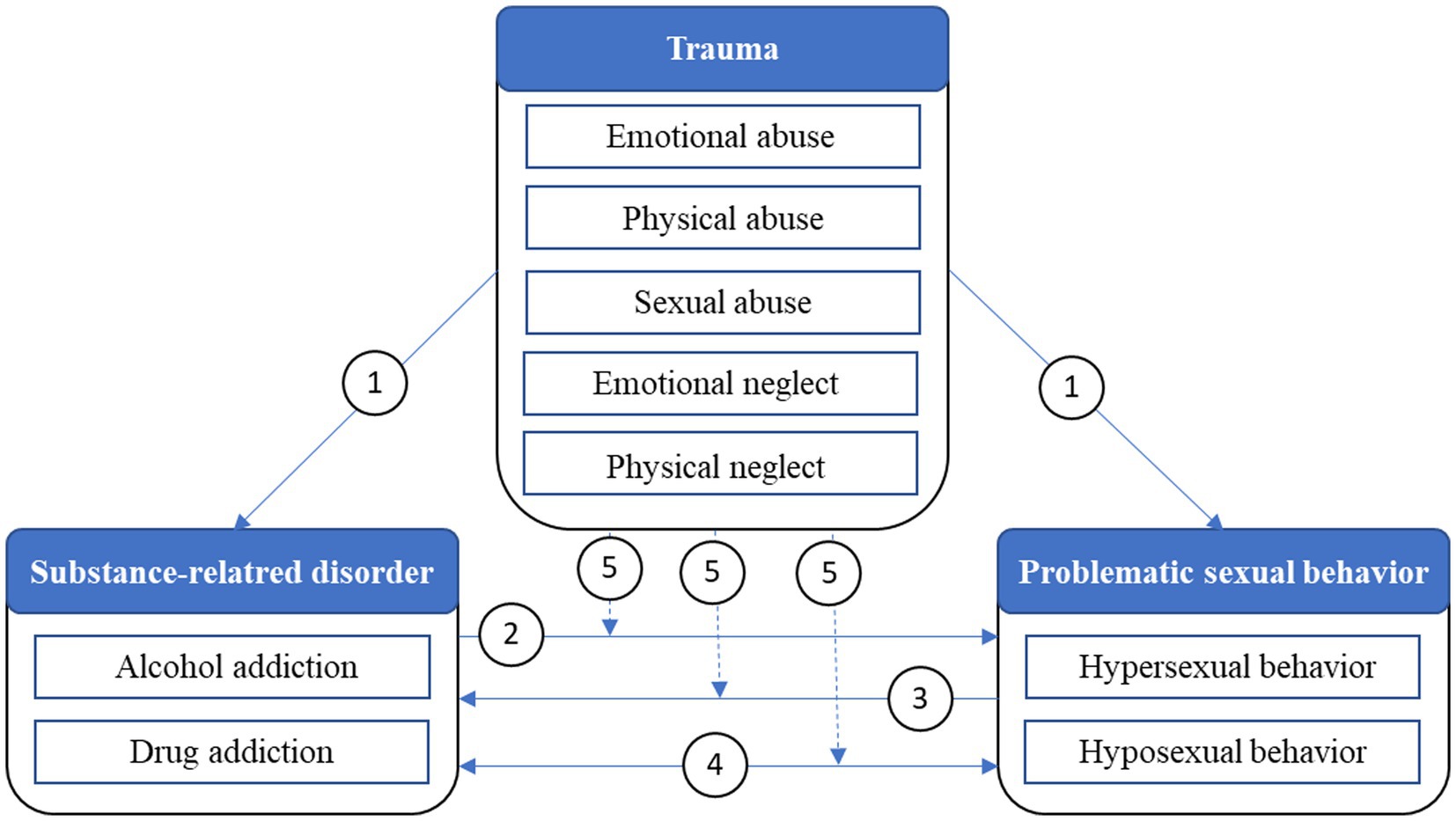

In Figure 1, possible relations between substance-related disorders, hypersexual and hyposexual behavior, and traumatic experiences according to relevant literature are shown. As described above, traumatic experiences in childhood and adolescence are a possible risk factor for the development of SUDs as well as problematic sexual behavior patterns (see arrow 1). At the same time, SUDs often seem to be accompanied by corresponding problematic sexual behaviors. Sexual changes may be the result of other symptoms of the disorder (see arrow 2), be the cause of its development and maintenance (see arrow 3), or manifest as a symptom and occur simultaneously with the disorder (e.g., due to shared risk factors) (see arrow 4) (44).

Figure 1. Possible relations between substance-related disorders, problematic sexual behaviors, and traumatic experiences.

The complex linking system between existing addictive disorders and hypersexual, as well as hyposexual behavior has not been explored sufficiently, while the results available to date appear inconclusive and difficult to compare. However, Efrati and colleagues (45) investigated, inter alia, the relation between early-life trauma and CSBD among young women with SUD. Their results indicate that young women with SUDs have higher-rated CSBD-symptoms as the healthy controls without SUD. In addition, SUD as well as CSBD were associated with childhood emotional abuse. However, negative life events were only related to CSBD, but not with SUD. To the best of our knowledge, no other study currently exists that examines the relation between the existence of SUDs and hypersexual/hyposexual behavior, and in particular the influence of traumatizing experiences on this relation (see arrow 5). Furthermore, there is little clarity whether the postulated associations between early trauma and the development of a sexual behavioral or functional disorder are specific to individuals with substance use disorders, or whether this association is also found in individuals not affected by it. As a result of the current state of knowledge described above and the existing research gaps, the following research questions have emerged for the investigation of the issue:

1. Do people with SUDs differ from a sample of people with other psychiatric disorders regarding hypersexual and hyposexual behavior?

2. What are the associations between the presence of sexual problems and the character of the SUD (e.g., mono vs. poly substance use, type of addictive substance, intensity of the disorder)?

3. How are traumatic experiences in childhood and adolescence associated with problematic sexual behavior among adults with a diagnosed SUD?

Gaining relevant knowledge promises new perspectives for diagnosis, case conception, treatment and therapy of SUDs as well as sexual problems in a psychiatric and therapeutic context.

2. Methods and analysis

2.1. Sample and inclusion criteria

The target group of this study are adults (aged 18 and above) diagnosed with a SUD. Data will be collected via an online survey, which will be promoted via several support and networking services for people with SUD (e.g., interest groups, internet forums, online self-aid groups, and online counseling services in Germany, more information stated in the section Procedure). Additionally, two control groups will be surveyed. The first control group will consist of people with other psychiatric disorders than addiction and traumatic experiences. They will be contacted via self-aid groups and counseling centers. The second control group comprises people without any diagnosed psychiatric disorder, which will be recruited via social media (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook). An a-priori power analysis was conducted via the software G-Power. The required sample size of the group of people with SUD was calculated 146 (F-test, multiple linear regression, effect size f2 = 0.15, α = 0.05), whereas the required sample size of the control groups was calculated 88, respectively (t-test, difference between two independent means, effect size d = 0.5, α = 0.05). Hence, the total required sample size is 322.

2.2. Study design and questionnaire

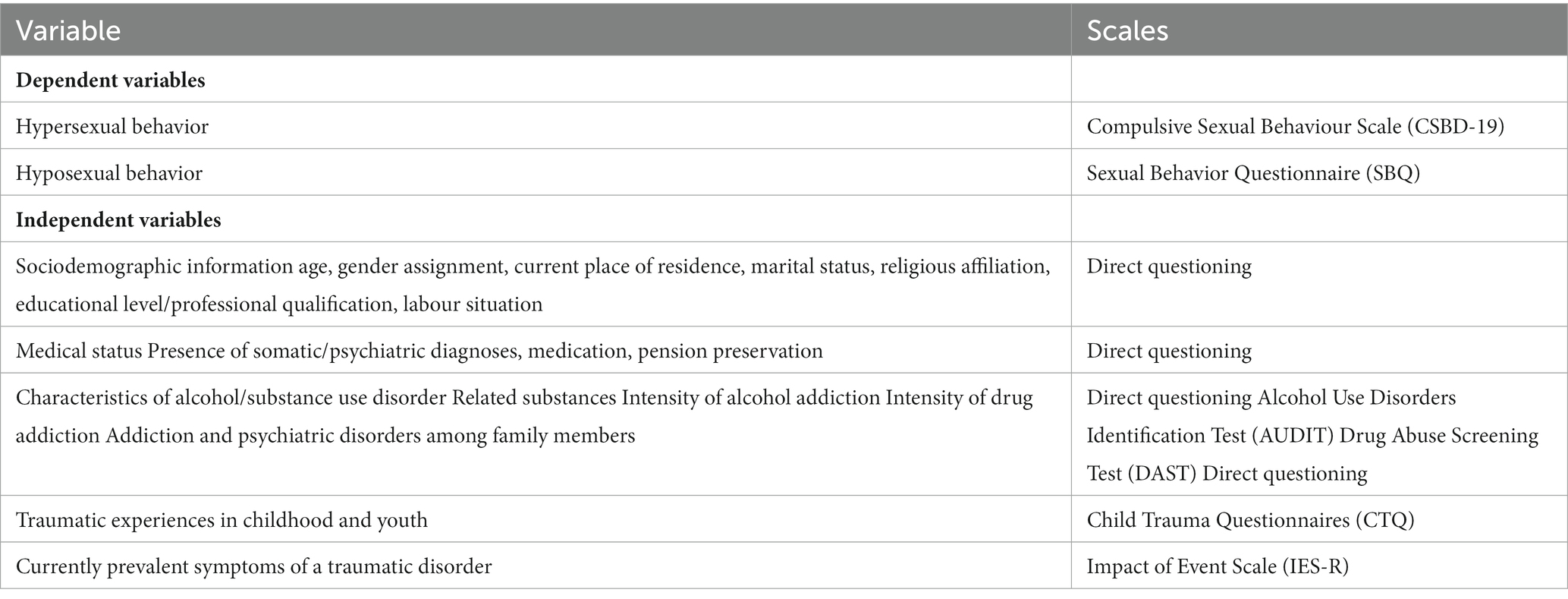

Within a cross-sectional ex-post-facto study, the required data will be collected via an online survey tool. In Table 2, the effect variables of the research proposal are listed.

2.2.1. Hypersexual behavior

The German version of the Compulsive Sexual Behavior Scale (CSBD-19) by Böthe et al. (46) will be used to measure clinically relevant hypersexual behavior. The scale is based on the ICD-11 diagnosis of CSBD and measures the construct via the subscales control, salience, relapse, dissatisfaction, and negative consequences using 19 items (four-pointed Likert-scales with answer options between 1 = totally disagree and 4 = totally agree) in total. The CSBD cut-off value is reached at a total sum score of ≥50 (46).

2.2.2. Hyposexual behavior

Hyposexual behavior will be measured by using the German version of the Sexual Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ) (47). The SBQ assesses indications for the presence of sexual dysfunction via six items addressing sexual behavior applied to all sexes and complementary to that, gender-specific hyposexual behaviors in biological women (five items) and men (six items) on a Likert-scale. The index of sexual dysfunction will be calculated via the measured variables desire for sex, capability to sexual arousal, capability to sexual enjoyment, satisfaction with sexual life and orgasm. A higher SBQ-score indicates a more intense hyposexual behavior (47).

2.2.3. Gender

Gender assignment will be measured in two steps according to the recommendations of Muschalik et al., using the items What sex was registered at your birth certificate and How do you designate your gender yourself, to shape the survey inclusive and gender-sensitive according to current scientific standards (48).

2.2.4. Substance-related disorder

To get information about characteristics of the prevalent addiction disorder, the related addictive substances will be recorded via two items: Please indicate which substances the substance use disorder is related to and Please indicate which of the stated substances causes you the most health problems with a list of several substance types as answer options. The intensity of the addictive disorder will be measured in different ways depending on the type of related substance. In the case of a prevalent alcohol addiction, the German version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) will be used, which measures the current intensity of an alcohol addiction via three subscales (alcohol consumption, dependence, and alcohol-related consequences) consisting of eight five-pointed and two three-pointed Likert-scaled items (49, 50). Depending on the determined score, the severity levels of the prevalent alcohol addiction can be derived, while values from 0 to 7 represents an abstinence/a low-risk use, 8 to 15 a risky use, 16 to 19 a harmful use, and 20 to 40 a remaining chronic alcoholism (50).

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) will be included to measure the intensity of a prevalent addiction due to illegal drugs, and consists of ten dichotomous items (answer options yes and no) (51). The determined sum score characterizes the degree of problems related to the drug abuse, while values from 1 to 5 represent a low or moderate level, 6 to 8 a substantial level, and from 9 to 10 a severe level (52). Since currently no German version of the DAST exists, the scale will be translated into German by conducting a forward-backward translation (53).

In addition, the number of hospitalizations due to the stated SUDas well as information on whether the participants are currently abstinent will be determined.

2.2.5. Trauma

Using the German version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire by Bernstein et al. (54–56) trauma in childhood and adolescence will be assessed using 28 ordinal five-point scaled items. The questionnaire includes five subscales – emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect (56). Furthermore, the German version of the Impact of Event Scale (IES-R) by Weiss and Marmar will be used to identify prevalent symptoms of a PTSD (intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal) via 22 ordinal four-point scaled items (57).

2.3. Procedure

A pretest will be conducted, while at first a technical check of the survey instrument should show its functionality on web-browser and smartphone. In the second part of the pretest, professionals of the care and treatment system addressing people with substance-related disorders, including social workers, addiction therapists, and physicians specialized in addiction treatment will be invited to evaluate the survey instrument regarding its suitability for people with substance-related disorders. According to the recommendations by Lenzner et al. (58), around 20 participants should be included into the pretest, because of economic reasons and the fact that the most problems with the items can usually already be identified with this number of test persons.

Data will be collected anonymously via an online questionnaire and advertised cooperating with various support and networking services for people with addiction. After careful exploration of the field, visible services, i.e., ten websites for information and mediation to self-aid groups, eight internet forums, five umbrella associations, three self-aid apps, and two online-counseling websites, will be contacted via e-mail to inform them about the purpose of the study and will be asked to advertise it on their websites. Five umbrella associations for psychiatric care in Germany will be contacted, and asked to promote an adapted version of the survey on their websites to recruit the control group of people with other psychiatric diagnoses than substance-related addictions with traumatic experiences. Further, social media handles on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter will be created to recruit the healthy control group.

At the beginning of the survey, the participants will be informed that the questionnaire deals with sensitive issues, such as mental diseases and traumatic experiences. The participants will be advised to consider this information when deciding whether to participate in the study or not. At this point, reference is also made to low-threshold offers of help, which can be utilized if the answering of the questions should lead to psychological stress. Furthermore, information on data processing and data protection will be stated. The participants must confirm the data protection consideration and the declaration of consent to participate.

2.4. Biometrics and data analyses

The statistical analysis will be conducted via the software IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 28. Data will be analyzed univariate, bivariate, and multivariate, while the presence of hypersexual or hyposexual behavior will be considered as dependent variables, and all other measured constructs as independent variables. Relations between the dependent and independent variables will be initially calculated via correlations and linear regression. Risk factors will be identified via multivariate regression. The effect of moderating or mediating variables will be controlled via particularly stratified analyses. Comparisons between the investigated groups of participants will be conducted via the appropriate inference statistical tests.

3. Discussion

3.1. Expected outcomes

The study aims firstly to provide a data basis to support the above mentioned associations between alcohol/drug addictions and problematic sexual behaviors, described in the relevant literature and only sparsely investigated in previous studies. To our best knowledge, this is the first study which investigates the association between substance-related addictions and hypersexual/hyposexual behavior focusing on the influence of traumatic experiences. Within this study, first insights addressing mediating and moderating effects of the prevalence of traumas on the relation between addiction and clinically apparent problematic sexual behaviors can be derived. Besides the statistical analysis of the topic, it will be a major objective of the study to discuss the meaning of the results for prevention and psychotherapeutic treatment.

Prevention should start before addictive patterns of alcohol and drug consumption are shaped, therefore the school context might be an important setting for prevention programs in general. Although projects addressing the prevention of developing substance use disorders are common in German schools, as well as sex education programs, the interactions between addictive and sexual behavior are not discussed sufficiently in preventive context. Thus, the practicing of chemsex and the related risks of developing drug addiction, compulsive sexual behavior, and/or sexual dysfunctions should be involved in preventive context, especially because its increasing importance in health-related sciences. Hence, appropriate sexual risk behaviors should be reflected according to the medical, psychological and social perspectives on them in an educational and preventive context.

Moreover, the crucial relevance of the patient’s individual sexuality should get more space in psychotherapeutic treatment of substance use disorders. As problems in the sexual life can lead to emotional stress, self-doubt, impairments in important areas of life and many other consequences, they can be understood as maintaining factors of psychiatric diseases in general, and addictive disorders in particular. By interpreting the results of this study, the role of sexual problems as a risk factor for the development and maintenance of substance use disorders, they should be elicited by proposing new etiological theories including aspects of sexuality.

3.2. Limitations

While interpreting the results it should be considered that the transferability of the results to the total population of people with addictions has limitations. For example, only those will participate in this survey who are integrated in the support system of addiction care in Germany, use online services of addiction care, and are in a stable phase of their addiction disease. Furthermore, to diagnose addictions, CSBD, or sexual dysfunctions, a personal medical or psychotherapeutic consultation is required. Within this study, the above listed scales are only able to provide indications for prevalent particular disorders and problematic behaviors among the participants and cannot be equated to diagnosis from qualified personnel. Conclusively, the ex-post-facto study design does not allow any conclusions about causal relations between substance-related disorders, problematic sexual behavior, and traumatic experiences but will deliver first insights.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethical committee of the medical faculty of the Martin-Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Germany. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

DJ is the main contributor to the study design, biometrics, and wrote the manuscript. SW and TL contributed to the study design. TL, MB, IM, and SW reviewed the study protocol. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support of the Open Access Publication Fund of the Martin-Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (Germany).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Krüger, THC. Der Einfluss Von Psychiatrischen Und Neurologischen Erkrankungen Auf Die Sexualität [The influence of psychiatric and neurological disorders on sexuality] In: U Hartmann, T Krüger, V Kürbitz, and C Neuhof, editors. Sexualmedizin Für die praxis–Sexualberatung und Krisenintervention Bei Sexuellen Störungen [Sexual Medicine for Practice–Sexual Counselling and Crisis Intervention]. Berlin: Springer (2020). 44–59.

2. Palha, AP, and Esteves, M. Drugs of abuse and sexual functioning. Adv Psychosom Med. (2008) 29:131–49. doi: 10.1159/000126628

3. Hallinan, R. Sexual function and alcohol and other drug use In: N El-Guebaly, G Carra, M Galanter, and AM Baldacchino, editors. Textbook of Addiction Treatment. Berlin: Cham Springer International Publishing (2021). 1225–39.

4. World Health Organization (2022). Icd-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics (Icd-11 mms). Available at: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (Accessed February 26, 2023).

5. Bründl, S, and Fuss, J. Impulskontrollstörungen in der ICD-11 [Impulse control disorders in ICD-11]. Forensische Psychiatrie Psychologie Kriminologie. (2021) 15:20–9. doi: 10.1007/S11757-020-00649-2

6. Grubbs, JB, Hoagland, KC, Lee, BN, Grant, JT, Davison, P, Reid, RC, et al. Sexual addiction 25 years on: a systematic and methodological review of empirical literature and an agenda for future research. Clin Psychol Rev. (2020) 82:101925. doi: 10.1016/J.Cpr.2020.101925

7. Sussman, S, Lisha, N, and Griffiths, M. Prevalence of the addictions: a problem of the majority or the minority? Eval Health Prof. (2011) 34:3–56. doi: 10.1177/0163278710380124

8. Antonio, N, Diehl, A, Niel, M, Pillon, S, Ratto, L, Pinheiro, C, et al. Sexual addiction in drug addicts: the impact of drug of choice and poly-addiction. Rev Assoc Med Bras. (2017) 63:414–21. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.63.05.414

9. Ballester-Arnal, R, Castro-Calvo, J, Gimenez-Garcia, C, Gil-Julia, B, and Gil-Llario, M. Psychiatric comorbidity in compulsive sexual behavior disorder (Csbd). Addict Behav. (2020) 107:106384. doi: 10.1016/J.Addbeh.2020.106384

10. Roth, K. Sexsucht–Störung Im Spannungsfeld Von sex, Sucht und trauma [sex addiction–disorder in a tension field of sex, addiction, and trauma] In: D Batthyány and A Pritz, editors. Rausch Ohne Drogen–Substanzungebundene Süchte [Intoxication Without Drugs–Behavioral Addictions]. Wien, New York: Springer (2009). 239–56.

11. Gertzen, M, Strasburger, M, Geiger, J, Rosenberger, C, Gernun, S, Schwarz, J, et al. Chemsex–Eine Neue Herausforderung Der Suchtmedizin und Infektiologie [Chemsex–a new challenge for addiction medicine and Infectology]. Nervenarzt. (2021) 93:263–78. doi: 10.1007/S00115-021-01116-X

12. Hibbert, MP, Hillis, A, Ce, B, Porcellato, LA, and Hope, VD. A narrative systematic review of sexualised drug use and sexual health outcomes among Lgbt people. Int J Drug Policy. (2021) 93:103187. doi: 10.1016/J.Drugpo.2021.103187

13. Rosenberger, C, Gertzen, M, Strasburger, M, Schwarz, J, Gernun, S, Rabenstein, A, et al. We have a lot to do: lack of sexual protection and information-results of the German-language online survey "Let's talk about Chemsex". Front Psych. (2021) 12:690242. doi: 10.3389/Fpsyt.2021.690242

14. Maxwell, S, Shahmanesh, M, and Gafos, M. Chemsex Behaviours among men who have sex with men: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy. (2019) 63:74–89. doi: 10.1016/J.Drugpo.2018.11.014

15. Spauwen, LW, Niekamp, AM, Hoebe, CJ, and Dukers-Muijrers, NH. Drug use, sexual risk behaviour and sexually transmitted infections among swingers: a cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. Sexual Transmitted Infections. (2014) 91:31–6. doi: 10.1136/Sextrans-2014-051626

16. Bohn, A, Sander, D, Köhler, T, Hees, N, Oswald, F, Scherbaum, N, et al. Chemsex and mental health of men who have sex with men in Germany. Front Psych. (2020) 11:542301. doi: 10.3389/Fpsyt.2020.542301

17. Briken, P, Matthiesen, S, Pietras, S, Wiessner, C, Klein, V, Reed, GM, et al. Estimating the prevalence of sexual dysfunction using the new Icd-11 guidlines: results of the first representative, population-based German health and sexuality survey (Gesid). Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. (2020) 117:653–8. doi: 10.3238/Arztebl.2020.065

18. Marhenke, T. Sexuelle Störungen–Eine Einführung [Sexual Disorders–An Introduction]. Wiesbaden: Springer (2020).

19. Hartmann, U, and Neuhof, C. Erektionsstörungen [erectile dysfunctions] In: U Hartmann, editor. Sexualtherapie [Sexual Therapy]. Berlin: Springer (2018). 289–314.

20. Hartmann, C. Weibliche Orgasmusstörungen [Orgasm disorders in females] In: U Hartmann, T Krüger, V Kürbitz, and C Neuhof, editors. Sexualmedizin Für Die Praxis–Sexualberatung Und Krisenintervention Bei Sexuellen Störungen [Sexual Medicine for Practice–Sexual Counselling and Crisis Intervention]. Berlin: Springer (2020). 195–202.

21. Neuhof & Hartmann. Vorzeitige (Frühe) ejakulation [premature ejaculation] In: U Hartmann, editor. Sexualtherapie [Sexual Therapy]. Berlin: Springer (2018). 315–48.

22. Neuhof, C, and Hartmann, U. Orgasmusstörungen–Ejaculatio praecox und Verzögerte Ejakulation orgasmic dysfunction–Ejaculatio praecox and delayed ejaculation In: U Hartmann, T Krüger, V Kürbitz, and C Neuhof, editors. Sexualmedizin Für die praxis–Sexualberatung und Krisenintervention Bei Sexuellen Störungen [Sexual Medicine for Practice–Sexual Counselling and Crisis Intervention]. Berlin: Springer (2020). 273–300.

23. Hoyer, J, and Velten, J. Sexuelle Funktionsstörung–Wandel der Sichtweisen und Klassifikationskriterien [Sexual dysfunction–changes of perspectives and diagnosis criteria]. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz. (2017) 60:979–86. doi: 10.1007/S00103-017-2597-7

24. Schneider, HJ, Jacobi, N, and Thyen, J. Hormone–Ihr Einfluss Auf Mein Leben [Hormones–Their Influence to My Life]. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer (2020).

25. Signerski-Krieger, J, Anderson-Schmidt, H, and Büttner, M. Sexuelle Störungen Bei Psychischen Erkrankungen [Sexual disorders in psychiatric deseases] In: M Büttner, editor. Sexualität und Trauma–Grundlagen und Therapie Traumassoziierter Sexueller Störungen [Sexuality and Trauma–Fundamentals and Therapy of Trauma-Associated Sexual Disorders]. Stuttgart: Schattauer (2018). 135–59.

26. Diehl, A, Pillon, SC, Ma, DS, Rassool, G, and Laranjeira, R. Sexual dysfunction and sexual behaviors in a sample of Brazilian male substance misusers. Am J Mens Health. (2016) 10:418–27. doi: 10.1177/1557988315569298

27. Grover, S, Mattoo, SK, Pendharkar, S, and Kandappan, V. Sexual dysfunction in patients with alcohol and opiod dependence. Indian J Psychol Med. (2014) 36:355–65. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.140699

28. Prabhakaran, DK, Nisha, A, and Varghese, PJ. Prevalence and correlates of sexual dysfunction in male patients with alcohol dependence syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Psychiatry. (2018) 60:71–7. doi: 10.4103/Psychiatry.Indianjpsychiatry_42_17

29. Rohilla, J, Dhanda, G, Ps, M, Jilowa, CS, Tak, P, and Jain, M. Sexual dysfunction in alcohol-dependent men and its correlation with marital satisfaction in spouses: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Industrial Psychiatry J. (2020) 29:82–7. doi: 10.4103/Ipj.Ipj_5_20

30. Yee, A, Danaee, M, Loh, HS, Sulaiman, AH, and Ng, CG. Sexual dysfunction in heroin dependents: a comparison between methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment. PLoS. (2016) 11:e0147852. doi: 10.1371/Journal.Pone.0147852

31. Dolatshahi, B, Farhoudian, A, Falhatdoost, M, Tavakoli, M, and Dogahe, ER. A qualitative study of the relationship between methamphetamine abuse and sexual dysfunction in male substance abusers. Int J High Risk Behav Addict. (2016) 5:e29640. doi: 10.5812/Ijhrba.29640

32. Moustafa, AA, Parkes, D, Fitzgerald, L, Underhill, D, Garami, J, Levy-Gigi, E, et al. The relationship between childhood trauma, early-life stress, and alcohol and drug use, abuse, and addiction: an integrative review. Curr Psychol. (2021) 40:579–84. doi: 10.1007/S12144-018-9973-9

33. Sack, M, and Büttner, M. Sexuelle Störungen Als Folge Sexueller Traumatisierungen [sexual dysfunctions as a result of traumatic experiences]. Psychotherapie Im Dialog. (2014) 15:28–31. doi: 10.1055/S-0034-1370807

34. Lalchandani, P, Lisha, N, Gibson, C, and Huang, AJ. Early life sexual trauma and later life genitourinary dysfunction and functional disability in women. J Gen Intern Med. (2020) 35:3210–7. doi: 10.1007/S11606-020-06118-0

35. Hase, M. Traumatisierter Sucht Bindung [Traumatized seeks attachment] In: KH Brisch, editor. Bindung und Sucht [Attachment and Addiction]. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta (2013). 92–109.

36. Greenfield, SF, Kolodziej, ME, Sugarman, DE, Muenz, LR, Vagge, LM, He, DY, et al. History of abuse and drinking outcomes following inpatient alcohol treatment: a prospective study. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2002) 67:227–34. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00072-8

37. Biedermann, SV. Sexuelle Funktionsstörungen Nach Traumatisierungen [sexual dysfunctions after traumatization] In: M Büttner, editor. Sexualität Und Trauma–Grundlagen Und Therapie Traumassoziierter Sexueller Störungen [Sexuality and Trauma–Fundamentals and Therapy of Trauma-Associated Sexual Disorders]. Stuttgart: Schattauer (2018). 95–115.

38. Zvara, BJ, Mills-Koonce, R, and Cox, M. Maternal childhood sexual trauma, child directed aggression, parenting behavior, and the moderating role of child sex. J Fam Viol. (2017) 32:219–29. doi: 10.1007/S10896-016-9839-6

39. Büttner, M. Einführung in die Thematik [introduction to the subject] In: M Büttner, editor. Sexualität Und Trauma–Grundlagen Und Therapie Traumassoziierter Sexueller Störungen [Sexuality and Trauma–Fundamentals and Therapy of Trauma-Associated Sexual Disorders]. Stuttgart: Schattauer (2018). 3–59.

40. Büttner, M. Hyposexuelle Störung oder "Sexuelle Ptbs"? [Hyposexual disorder or sexual PTSD?] In: M Büttner, editor. Sexualität und trauma–Grundlagen und Therapie Traumassoziierter Sexueller Störungen [Sexuality and Trauma–Fundamentals and Therapy of Trauma-Associated Sexual Disorders]. Stuttgart: Schattauer (2018). 60–7.

41. Von Franqué, F, and Briken, P. Hypersexuelle störung bei sexuellen missbrauchserfahrungen [hypersexual disorder and experiences of sexual abuse] In: M Büttner, editor. Sexualität Und Trauma–Grundlagen Und Therapie Traumassoziierter Sexueller Störungen [Sexuality and Trauma–Fundamentals and Therapy of Trauma-Associated Sexual Disorders]. Stuttgart: Schattauer (2018). 116–22.

42. Davis, K, and Knight, R. The relation of childhood abuse experiences to problematic sexual behaviors in male youths who have sexually offended. Arch Sex Behav. (2019) 48:2149–69. doi: 10.1007/S10508-018-1279-3

43. Castellini, G, Rellini, A, Appignanesi, C, Pinucci, I, Fattorini, M, Grano, E, et al. Deviance Or Normalcy? The relationship among paraphilic thoughts and behaviors, Hypersexuality, and psychopathology in a sample of university students. J Sex Med. (2018) 15:1322–35. doi: 10.1016/J.Jsxm.2018.07.015

44. Schmidt, H, and Berner, M. Sexuelle störungen bei psychiatrischen erkrankungen [sexual disorders in psychiatric diseases] In: P Briken and M Berner, editors. Praxisbuch Sexuelle Störungen–Sexuelle gesundheit, Sexualmedizin, Psychotherapie Sexueller Störungen [Practice Book Sexual Disorders–Sexual Health, Sexual Medicine, Psychotherapy of Sexual Disorders]. Stuttgart: Thieme (2013). 158–74.

45. Efrati, Y, Goldman, K, Levin, K, and Rosca, P. Early-life trauma, negative and positive life events, compulsive sexual behavior disorder and risky sexual action tendencies among young women with substance use disorder. Addict Behav. (2022) 133:107379. doi: 10.1016/J.Addbeh.2022.107379

46. Böthe, B, Mn, P, Md, G, Kraus, SW, Klein, V, Fuss, J, et al. The development of the compulsive sexual behavior disorder scale (Csbds): An Icd-11 based screening measure across three languages. J. Behav. Addict. (2020) 9:247–58. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00034

48. Muschalik, C, Otten, M, Breuer, J, and Von Rüden, U. Erfassung und Operationalisierung des Merkmals Geschlecht in repräsentativen bevölkerungsstichproben [Measurement and operationalization of gender in representive samples]. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz. (2021) 64:1364–71. doi: 10.1007/S00103-021-03440-8

49. Suchtforschungsverbund Baden-Württemberg, UKL Freiburg. AUDIT-Fragebogen - Auswertungsschema [AUDIT Questionnaire - Evaluation Shema] (2021). https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/_old-files/downloads/AlkAuditAuswertung.pdf (Accessed March 06, 2023).

50. Babor, T, and Robaina, K. The alcohol use disorders identification test (Audit): a review of graded severity algorithms and National Adaptations. Izard. (2016) 5:17–24. doi: 10.7895/Ijadr.V5i2.222

51. Yudko, E, Lozhkina, O, and Fouts, A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the drug abuse screening test. J Subst Abus Treat. (2007) 32:189–98. doi: 10.1016/J.Jsat.2006.08.002

52. National Institute On Drug Abuse (2019). Dast-10. Available at: https://gwep.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/dast-10-drug-abuse-screening-test.pdf (Accessed November 02, 2022).

53. Acquadro, C, Conway, K, Hareendran, A, and Aaronson, N. Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value Health. (2008) 11:509–21. doi: 10.1111/J.1524-4733.2007.00292.X

54. Karos, K, Niederstrasser, N, Abidi, L, Bernstein, DP, and Bader, K. Factor structure, reliability, and known groups validity of the German version of the childhood trauma questionnaire (short-form) in Swiss patients and nonpatients. J Child Sex Abus. (2014) 23:418–30. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2014.896840

55. Bernstein, DP, Fink, L, Handelsman, L, and Foote, J. Childhood trauma questionnaire (Ctq) [database record]. APA PsycTests. (1994). doi: 10.1037/T02080-000

56. Klinitzke, G, Romppel, M, Hauser, W, Brahler, E, and Glaesmer, H. The German version of the childhood trauma questionnaire (Ctq): psychometric characteristics in a representative sample of the general population. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. (2012) 62:47–51. doi: 10.1055/S-0031-1295495

57. Weiss, DS, and Marmar, CR. The impact of event scale – revised In: JP Wilson and TM Keane, editors. Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford (1996). 399–411.

Keywords: alcohol addiction, chemsex, childhood trauma, compulsive sexual behavior, drug addiction, libido, sexual dysfunction, substance use disorder

Citation: Jepsen D, Luck T, Bernard M, Moor I and Watzke S (2023) Study protocol: Hypersexual and hyposexual behavior among adults diagnosed with alcohol- and substance use disorders—Associations between traumatic experiences and problematic sexual behavior. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1088747. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1088747

Edited by:

Francesco Paolo Busardò, Marche Polytechnic University, ItalyReviewed by:

Ulrich W. Preuss, Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, GermanyOruç Yunusoğlu, Abant Izzet Baysal University, Türkiye

Yaniv Efrati, Bar Ilan University, Israel

Copyright © 2023 Jepsen, Luck, Bernard, Moor and Watzke. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dennis Jepsen, ZGVubmlzLmplcHNlbkBtZWRpemluLnVuaS1oYWxsZS5kZQ==

Dennis Jepsen

Dennis Jepsen Tobias Luck

Tobias Luck Marie Bernard

Marie Bernard Irene Moor

Irene Moor Stefan Watzke3

Stefan Watzke3