94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry, 05 July 2023

Sec. Psychological Therapy and Psychosomatics

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1060961

This article is part of the Research TopicLeveraging Tele-behavioral Health Modalities and Technology-Enabled Behavioral Healthcare: Emerging Trends during COVID-19View all 7 articles

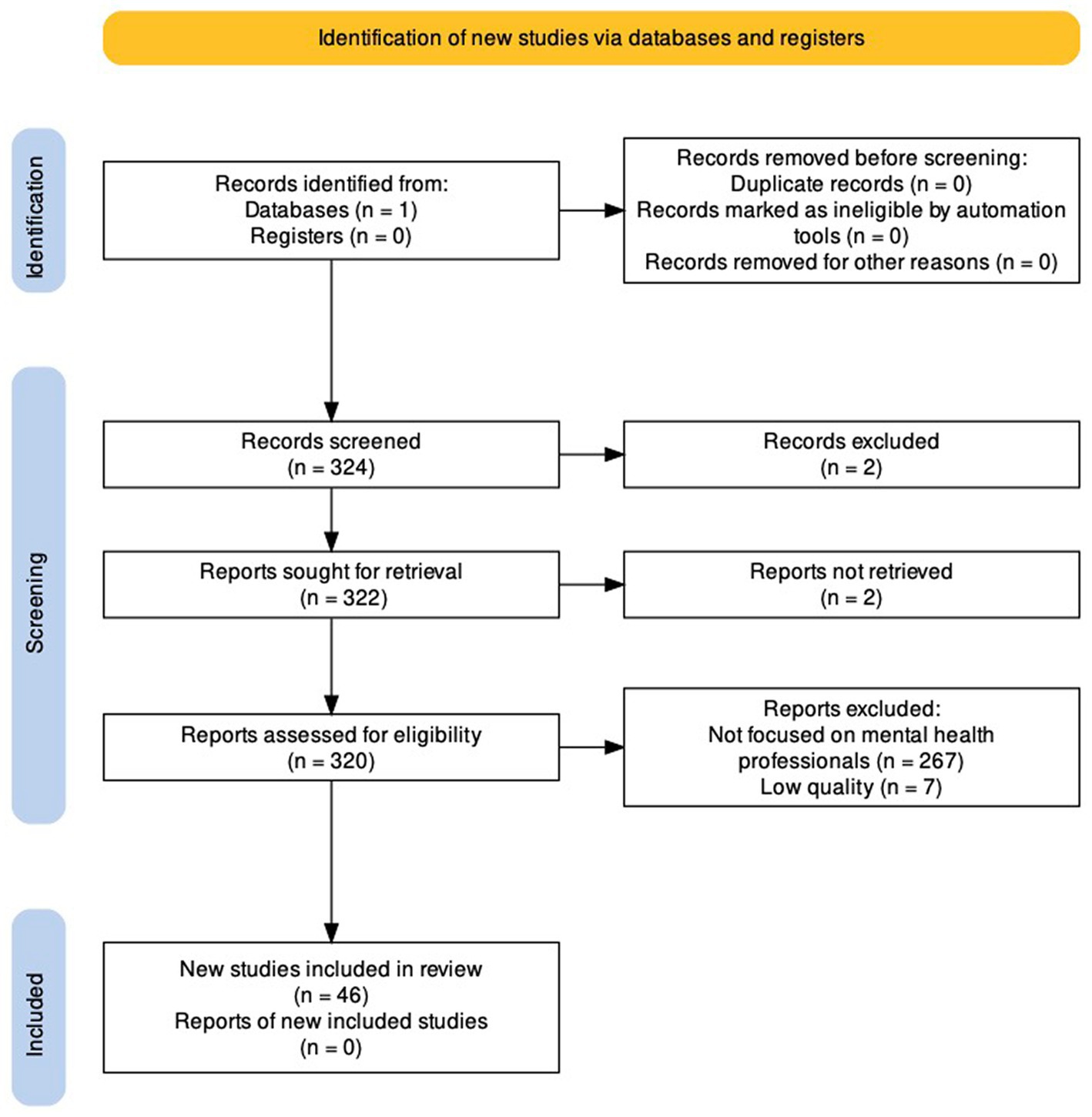

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed psychotherapy practices. Psychotherapy around the world has shifted from predominantly face-to-face settings to overwhelmingly online settings since the beginning of the pandemic. Many studies have been published on this topic, but there has been no review of the literature focused on the experience of psychotherapists. Our goal was to identify the challenging issues of teletherapy, including the efficiency of online consultations and the extent to which they are accepted by therapists and patients. A PubMed literature search using the [(“Teletherapy” OR “Telebehavioral health” OR “telepsychotherapy”) AND (“COVID-19”)] search string retrieved 46 studies focused on mental health professionals, as detailed in a PRISMA flow diagram. Two reviewers independently screened the abstracts and excluded those that were outside the scope of the review. The selection of articles kept for review was discussed by all three authors. Overall, the review contributes to the description and evaluation of tele mental health services, including teletherapy, online counseling, digital mental health tools, and remote monitoring.

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed psychotherapy practices. Psychotherapy around the world has shifted from predominantly face-to-face settings to overwhelmingly online settings since the beginning of the pandemic. Many initiatives worldwide have been implemented targeting healthcare workers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as psychological support systems and hotlines for hospital workers (1). While there is an urge to provide emotional support to the healthcare workforce (2) and protect their mental health (3) there have been no studies specifically investigating mental health care workers’ own mental health. This paper aims to explore the consequences of the shift to telehealth in mental health practice for both clinicians and their patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been viewed as an opportunity to transform psychiatric care through the implementation of telehealth (4). However, there are several challenging issues regarding the implications of telehealth, including digital health inequity (5), and we do not have sufficient knowledge on the efficiency of online consultations and the extent to which they are accepted by clinicians and patients (6). More generally, the issue of distance mental health care practice is also central to disaster research (7, 8). Supporting people affected by health, but also natural, man-made and technological disasters, often requires creativity, as traditional care infrastructures and private mental health care practitioners’ offices can be damaged; and, most people today, including many of the most disadvantaged, have access to a phone or the internet (9, 10).

Many studies have been published since the beginning of the pandemic, but there has been no review of the literature focused on mental health providers. Our goal is to identify the challenging issues surrounding teletherapy, including the efficiency of online consultations and the extent to which they are accepted by both therapists and patients.

A PubMed literature search restricted to the English language using the [(“Teletherapy” OR “Telebehavioral health” OR “Telepsychotherapy”) AND (“COVID-19”)] search string retrieved 46 studies focused on mental health professionals, as detailed in a PRISMA flow diagram (11). The articles under review were published from January 1, 2020 to April 13, 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram. Adapted from Haddaway et al. (11).

Two reviewers (NT and RP) independently screened the abstracts and excluded those that were outside the scope of the review. To be included in the mini-review, articles had to be focused on mental health professionals and online psychotherapy practice during the Covid-19 pandemic. Articles targeting other health care workers or providers, patients or their parents or caregivers were excluded. The selection of articles selected for review was discussed by all three authors via Zoom (Table 1).

Among the 46 studies retained, four subgroups were distinguished. The first group includes articles on mental health services and therapists (17/46). The second group focus solely on psychodynamic approaches (11/46). The third subgroup consists of studies on couples and marriage and family therapy practices (10/46). The fourth group comprises the treatment of specific mental disorders, such as PTSD or developmental disorders (8/46).

A study in the Netherlands (12) focusing on experiences of psychotherapists, both positive and negative, found that insufficient technological infrastructure both on the side of the therapist (internet-connection stability) and the patient, who might lack necessary devices (smartphone or computer) are significant barriers as well as a lack of privacy in the clients’ environments. The need for an improved technological infrastructure, user-friendly technologies, appropriate devices, stable internet connections and privacy is reported by numerous other studies in different contexts and countries. For instance, Roberts and colleagues (13) investigated the specific situations for healthcare delivery from teams who come from outside the region where services are offered, such as Canadian circumpolar regions. The perceived challenges in the case of services for Indigenous communities were the lack of technology, internet access, and privacy. In Italy, CB therapists (14) also mention difficulties in accessing a private space at home and using videoconferencing instead of telephone. In Oman, a study underlines (15) a lack of public tele-mental health services and guidelines, a shortage of trained therapists – consistent with another survey in Lebanon (16) – as well as limited access to high-speed internet and electronic devices, privacy and security concerns.

Increased stress levels were reported among Austrian psychotherapists compared to a control group during the COVID-19 pandemic (17). Additionally, three Austrian cross sectional online surveys assessing patient numbers show an increasing workload for psychotherapists and an insufficient support of psychotherapists (18). A Scottish study (19) also found that MH workers are less able to receive support from colleagues. In addition to an increased stress and a lack of support, a lack of common therapeutic skills in teletherapy compared to in-person therapy is reported by psychotherapists (20). These skills include the use of various therapeutic techniques, intentional silence, empathy, emotional expression, and conversational tone. Undoubtedly, there is an urgent need for training in teletherapy (21) to improve the confidence of psychotherapists.

In a more positive light, acceptability in neuropsychological practice is good despite some limitations for forensic neuropsychology practice (22), or regarding healthcare disparities (23). Moreover, a study has found potential for improving veteran’s self-care skills but insists on the need to increase access to telehealth for all (24). Importantly, there is a satisfaction with videoconference-delivered CBT for children and adolescents (21). Sessions are shorter and easier to schedule, and team meetings are efficient (12). Surprisingly, older generations were less reluctant to accept teletherapy than expected (20), and techniques that were thought to be reserved for in-person sessions can be incorporated in teletherapy (25).

It appears that psychodynamic therapists or psychoanalysts have had a more positive opinion regarding the effectiveness of online sessions since the pandemic began, psychotherapists and psychoanalysts based in China being more positive than those based in the US (26). First-person accounts of psychoanalysts were published (27–29), and clinicians started to use the term “teleanalysis,” comparing the impact of physical distance on psychoanalytic treatment to that of the couch (30, 31). In psychodynamic therapy, whether online or in person, the most important aspects of treatment effectiveness are the same: the therapist’s empathy, warmth, wisdom, and skillfulness and patient’s motivation, insightfulness, and level of functioning (32). Additionally, experts in accelerated experiential dynamic psychotherapy have developed specific techniques to be applied in an online setting, and they insisted on the need to take more time with patients starting therapy online to discuss the rules regarding the setting, stability, and privacy (33). Interestingly, studies have found greater conversational, relaxed and simultaneously more directive attitude during online sessions (31, 34). Limitations are found in an Argentinian study insisting that telepsychotherapy is more exhausting than in-person psychotherapy and that an improvement of technical conditions and privacy during sessions are needed (35).

Couples and marriage and family therapists identified benefits for patients living in rural areas and underserved populations, and teletherapy eases the logistics involved in making childcare arrangements, which facilitates access to care for working parents (36). Advantages of teletherapy reported by clinicians included the reduction of expenses, increase in personal time, improved access to meetings, improved accessibility, and flexibility (37). An analysis of existing data collected from two university marriage and family therapy training programs in the US found that most cases converted to teletherapy and that “the number of prior in-person sessions attended significantly predicted conversion to teletherapy” (38). It is consistent with a survey of therapists in an organization that provided more than 35,000 virtual sessions of Functional Family Therapy between March and September 2020 worldwide which found similar rates for treatment completion, number of sessions, and therapist fidelity between 2019 and 2020, suggesting that teletherapy is a viable alternative to in-person session (39). Another study found that in most cases, the shift to online sessions during the pandemic was not a threat to the therapeutic relationship, although patients reported to their therapists that “it felt different.” There was agreement among 80 percent of participants that teletherapy offers good quality of care (40).

While the shift to telepsychotherapy was positive overall, there are barriers to teletherapy with couples such as violence, severe MDs, and suicidal ideation (41). Importantly, couples and family teletherapy are not indicated in the case of family conflict, especially if it implies children in the home would not be supervised during the session (36). There are challenges for certain populations and specific pathologies requiring in-person treatment: “Physical medicine and rehabilitation, antisocial personality disorder, traumatic brain injury, and family conflict were associated with the lowest increases in teletherapy uptake” (36). Couples and marriage and family therapists expressed concerns regarding digital exclusion, fatigue, isolation, lack of motivation for some patients, disruptions in the flow of therapy, and many other difficulties regarding the use of therapeutic techniques or resources (37). More precisely, therapists experienced discomfort, such as eyestrain, blurred vision, and motion sickness, to the extent that several of them doubted their ability to continue providing online sessions full time, given the increase in emotional vulnerability and experiences of fatigue and low energy (42).

The Family Institute at Northwestern University launched its teletherapy services in 2018 and made an important contribution to the field. Notably, they insisted on the preparation of the therapist’s office, which is visible on clients’ screens: “While there may be value to ‘humanizing’ a therapist through what the environment discloses about them personally, some content may be problematic. Such details force a client to interact with the therapist’s personal life in a way that may be activating and, depending on the client and the personal information communicated, may violate boundaries and basic standards for professionalism” (40). A ritual for entering into a therapeutic mindset is recommended on both sides, as well as creating an environment that ensures privacy (e.g., a family member should not enter the room) and reduces distractions (e.g., pets), including using a full-screen browser window during sessions. Eye contact might also be a problem. Even when the therapist looks at the camera, the patient might feel that the therapist’s gaze is directed above or below their face. The biggest challenge encountered was teletherapy with children, where considerable adaptation was required, and difficulty maintaining their attention was a recurrent issue. An efficient strategy with children with ADHD was to provide frequent 5-min breaks. With young children, it is advised that session not exceed 30 min and that the camera show the entire room to allow the child to move around and be seen playing. Teens have shown some creativity in ensuring their privacy, including asking their parents to take a walk during their sessions, having sessions in their parents’ parked car, using a noise generator placed outside of their room, or using headphones, which also contributes to creating rituals for the session. Interestingly, many teens appreciated multiple short sessions rather than only one long session. Couples teletherapy was challenging during the pandemic, especially in cases of domestic violence; many patients wanted to talk, but they were also afraid of the consequences after the end of the virtual session. In couples and family therapy, the online setting necessitates clients speak one at a time, which is a major difference compared to in-person sessions (40).

Teletherapy seemed to benefit anxious autism spectrum disorder patients, who found it less invasive, and those who worked considered it easier to integrate into their schedule, though others recognized challenges in conducting therapy this way. There are technical difficulties and internet-connection issues, which do not amount to a limitation to its use, per se, but they are a barrier for special-needs children with significant mental health issues and intellectual disabilities (43).

According to a Canadian research, digital health can become a standard delivery mode for trauma therapy (44). Benefits include equity of access to care and stigma reduction; however, technological and reimbursement issues will need to be addressed if a generalized digital health system becomes the new normal. Although US clinicians taking care of veterans also found a limitation regarding considerations for cognitive functioning, especially for older patients (45), teletherapy for veterans is considered feasible, acceptable, effective, and adaptable beyond the pandemic period.

Two studies show difficulties in accessing mental health services for ethnic minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals with Adverse Childhood Experiences (46), and challenges for vulnerable groups (lower socioeconomic conditions, Medicaid beneficiaries, and those who seek couple and family therapy) as well as access to technology, housing, childcare, and need for training for professionals (47).

Significant challenges have been reported with children with attentional difficulties in Germany (48) a result consistent with what is observed in the US (21). Additionally, several systemic therapists offering couples teletherapy in the US mentioned having difficulty working with children online due to their short attention spans (42).

Finally, a survey on early intervention services for first-episode psychosis during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Quebec found limitations regarding clinicians’ levels of ease with teletherapy, as well as lack of technical support and availability of telehealth equipment (49).

Most of the studies were the first of their kind, given the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and the need for teletherapy to be implemented very rapidly after the start of the pandemic and the related lockdowns. More than ever, studies have insisted that teletherapy is more demanding than face-to-face therapy (35, 44, 50), hence the need for self-care practices for the well-being of therapists (17, 33). Teletherapy has a cost for therapists: mental fatigue, physical symptoms, such as eyestrain, blurred vison, and motion sickness, emotional vulnerability, and isolation (18, 21, 34, 37, 42, 51). The issue of being forced into teletherapy, both on the side of patients and therapists, was discussed (20, 38, 52) and should not be disregarded. Among the barriers, concerns over a lack of confidentiality and privacy were mentioned often by patients who were reluctant to use teletherapy. Additionally, the possibility that a patient could identify the home address of their therapist is an important matter, as this could threaten the safety of teletherapists.

There are difficulties in cases of family conflict, where there is a duty to report child abuse and suicidality in minor patients and geriatric populations. It is also difficult to identify neglect or abuse if someone is only treated through teletherapy, especially in cases of, for example, physically impaired and vulnerable populations (36, 47, 53). Family therapy and therapy for psychotic symptoms, severe anxiety, trauma, or individuals in crisis is less suited to online sessions (12).

This review was conceived as a first overview of an unexplored subject and was not intended to be exhaustive. A systematic review of the literature is necessary with a more varied choice of keywords, allowing for the inclusion of relevant articles that were not discussed in our mini-review. In addition, some articles were surveys that took place during the first wave and are therefore likely not generalizable beyond that.

There are general limitations of many studies that focus on a small and sometimes heterogeneous sample of respondents. Many articles that supposedly focused on MDs did not discuss the specific impact on each MD as experienced by patients; rather, they focus on the delivery of services, acceptability, training, and guidelines. In fact, little is known about the impact of the online setting on the treatment of first-episode psychosis (49), eating disorders (54) or developmental disorders (50). An exception was found in a work on trauma therapy, which reported a barrier to teletherapy for PTSD patients with cognitive impairment (44). Notably, the presence of parents is necessary for children with developmental disorders (50), which might be considered a regression in the psychoanalytical therapy process, which, for instance, sometimes helps a parent and child to separate from each other.

Patients receiving therapy online while staying at home might express their satisfaction, saying that their anxiety about going out is reduced and they feel more in control. These aspects were reported as beneficial, but they could be considered drawbacks as well; avoiding going outside does not do much for the treatment of social anxiety disorders, and being more in control could result in a reinforcement of defense mechanisms or an increase in OCD symptoms.

This mini-review was limited to a Pubmed search and should be considered as a preliminary step towards a systematic review of the literature including other keywords and databases. From this point of view, it would be interesting if the diversity of psychotherapists and the laws that govern their practice around the world were considered. Indeed, online practice has challenged state boundaries more than ever before, which is a positive development, but raises many clinical, legal (55, 56) and ethical questions that are crucial to the profession.

This review of the literature reveals important qualitative feedback from therapists of diverse horizons regarding how online sessions have become embedded in therapy practice. The use of teletherapy does not seem to be transient, nor does it depend on the COVID-19 pandemic. It appears that acceptability is relatively good from the point of view of both patients and therapists, and it seems that we are witnessing a generalization of hybrid practices in mental health. A possible problem with telepsychotherapy and teleconsultations is how they will be used by ministries of health at the global level. It is feared that online consultations will be imposed for supposedly cost-saving reasons. Not all conditions are suitable for teleconsultation, and in some cases, therapists and patients want to see each other in person. In other words, we fear a loss of therapeutic effects if telepsychotherapy becomes “the new normal”; however, hybrid practice is desired by most therapists and patients. Future studies should examine the effectiveness of the different therapy modalities by comparing three groups of patients: one receiving in-person therapy only, one receiving telepsychotherapy only, and one receiving hybrid services. Finally, the rise of telepsychotherapy might be summed up by a paradoxical sentence that is of great significance in the history of clinical practice: keeping in touch (37) while losing touch (57).

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This study was supported by JSPS Kakenhi (grant number 19 K12975).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Geoffroy, PA, le Goanvic, V, Sabbagh, O, Richoux, C, Weinstein, A, Dufayet, G, et al. Psychological support system for hospital workers during the Covid-19 outbreak: rapid design and implementation of the Covid-Psy hotline. Front Psych. (2020) 11:11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00511

3. Greenberg, N, Brooks, SK, Wessely, S, and Tracy, DK. How might the NHS protect the mental health of health-care workers after the COVID-19 crisis? Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:733–4.

4. Torous, J, and Wykes, T. Opportunities from the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic for transforming psychiatric care with Telehealth. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:1205–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1640

5. Rodriguez, JA, Clark, CR, and Bates, DW. Digital health equity as a necessity in the 21st century cures act era. JAMA. (2020) 323:2381–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7858

6. Colle, R, Ait Tayeb, AEK, de Larminat, D, Commery, L, Boniface, B, Lasica, P-A, et al. Short‐term acceptability by patients and psychiatrists of the turn to psychiatric teleconsultation in the context of theCOVID‐19 pandemic. PCN Rep. (2020) 74:443–4. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13081

7. Weems, CF. The importance of the post-disaster context in fostering human resilience. Lancet Planet Health. (2019) 3:e53–4. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30014-2

8. Tracy, M, Norris, FH, and Galea, S. Differences in the determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression after a mass traumatic event. Depress Anxiety. (2011) 28:666–5. doi: 10.1002/da.20838

9. Stasiak, K, Merry, SN, Frampton, C, and Moor, S. Delivering solid treatments on shaky ground: feasibility study of an online therapy for child anxiety in the aftermath of a natural disaster. Psychother Res. (2018) 28:643–53. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1244617

10. Ruzek, JI, Eric Kuhn, E, Jaworski, BK, Owen, JE, and Ramsey, KM. Mobile mental health interventions following war and disaster. Mhealth. (2016):2. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2016.08.06

11. Haddaway, NR, Page, MJ, Pritchard, CC, and McGuinness, LA. PRISMA2020: an R package and shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev. (2022) 18:e1230.

12. Feijt, M, de Kort, Y, Bongers, I, Bierbooms, J, Westerink, J, and Ijsselsteijn, W. Mental health care Goes online: practitioners’ experiences of providing mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020) 23:860–4. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0370

13. Roberts, C, Darroch, F, Giles, A, and van Bruggen, R. Plan a, plan B, and plan C-OVID-19: adaptations for fly-in and fly-out mental health providers during COVID-19. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2021) 80:1. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2021.1935133

14. Boldrini, T, Schiano Lomoriello, A, Del Corno, F, Lingiardi, V, and Salcuni, S. Psychotherapy during COVID-19: how the clinical practice of Italian psychotherapists changed during the pandemic. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1170. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.591170

15. Al-Mahrouqi, T, Al-Alawi, K, Al-Alawi, M, Al Balushi, N, Al Ghailani, A, Al Sabti, H, et al. A promising future for tele-mental health in Oman: a qualitative exploration of clients and therapists’ experiences. SAGE Open Med. (2022) 10:10863. doi: 10.1177/20503121221086372

16. Tohme, P, De Witte, NAJ, Van Daele, T, and Abi-Habib, R. Telepsychotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: the experience of Lebanese mental health professionals. J Contemp Psychother. (2021) 51:349–5. doi: 10.1007/s10879-021-09503-w

17. Probst, T, Humer, E, Stippl, P, and Pieh, C. Being a psychotherapist in times of the novel coronavirus disease: stress-level, job anxiety, and fear of coronavirus disease infection in more than 1,500 psychotherapists in Austria. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:100. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.559100

18. Winter, S, Jesser, A, Probst, T, Schaffler, Y, Kisler, IM, Haid, B, et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic affects the provision of psychotherapy: results from three online surveys on Austrian psychotherapists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:1961. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20031961

19. Griffith, B, Archbold, H, Sáez Berruga, I, Smith, S, Deakin, K, Cogan, N, et al. Frontline experiences of delivering remote mental health supports during the COVID-19 pandemic in Scotland: innovations, insights and lessons learned from mental health workers. Psychol Health Med. (2023) 28:964–9. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2022.2148698

20. Lin, T, Stone, SJ, Heckman, TG, and Anderson, T. Zoom-in to zone-out: therapists report less therapeutic skill in Telepsychology versus face-to-face therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychotherapy. (2021) 58:449–9. doi: 10.1037/pst0000398

21. Baker, AJL, Konigsberg, M, Brown, E, and Adkins, KL. Successes, challenges, and opportunities in providing evidence-based teletherapy to children who have experienced trauma as a response to Covid-19: a national survey of clinicians. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2023) 146:106819. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.106819

22. Messler, AC, Hargrave, DD, Trittschuh, EH, and Sordahl, J. National survey of telehealth neuropsychology practices: current attitudes, practices, and relevance of tele-neuropsychology three years after the onset of Covid-19. Clin Neuropsychol. (2023):1–20. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2023.2192422

23. Hewitt, KC, Block, C, Bellone, JA, Dawson, EL, Garcia, P, Gerstenecker, A, et al. Diverse experiences and approaches to tele neuropsychology: commentary and reflections over the past year of COVID-19. Clin Neuropsychol. (2022) 36:790–5. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2022.2027022

24. Khanna, A, Dryden, EM, Bolton, RE, Wu, J, Taylor, SL, Clayman, ML, et al. Promoting whole health and well-being at home: veteran and provider perspectives on the impact of Tele-whole health services. Glob Adv Health Med. (2022) 11:11426. doi: 10.1177/2164957X221142608

25. Pugh, M, Bell, T, and Dixon, A. Delivering tele-chairwork: a qualitative survey of expert therapists. Psychother Res. (2021) 31:843–8. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2020.1854486

26. Wang, X, Gordon, RM, and Snyder, EW. Comparing Chinese and US practitioners' attitudes towards teletherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2021) 13:e12440. doi: 10.1111/appy.12440

27. Svenson, K. Teleanalytic therapy in the era of Covid-19: dissociation in the countertransference. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. (2020) 68:447–54. doi: 10.1177/0003065120938772

28. Tyminski, R. Back to the future: when children and adolescents return to office sessions following episodes of teletherapy. J Anal Psychol. (2022) 67:1070–90. doi: 10.1111/1468-5922.12836

29. Schen, CR, Pressman, AR, and Olds, J. Lost and found in psychotherapy during COVID-19. Psychodyn Psychiatry. (2022) 50:476–1. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2022.50.3.476

30. Levey, EJ. Analyzing from home: the virtual space as a flexible container. Psychodyn Psychiatry. (2021) 49:425–11. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2021.49.3.425

31. Békés, V, van Doorn, KA, Roberts, KE, Stukenberg, K, Prout, T, and Hoffman, L. Adjusting to a new reality: consensual qualitative research on therapists’ experiences with teletherapy. J Clin Psychol. (2023) 79:1293–13. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23477

32. Gordon, RM, Shi, Z, Scharff, DE, Fishkin, RE, and Shelby, RD. An international survey of the concept of effective psychodynamic treatment during the pandemic. Psychodyn Psychiatry. (2021) 49:453–2. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2021.49.3.453

33. Ronen-Setter, IH, and Cohen, E. Becoming “Teletherapeutic”: harnessing accelerated experiential dynamic psychotherapy (AEDP) for challenges of the Covid-19 era. J Contemp Psychother. (2020) 50:265–3. doi: 10.1007/s10879-020-09462-8

34. Mancinelli, E, Gritti, ES, Schiano Lomoriello, A, Salcuni, S, Lingiardi, V, and Boldrini, T. How does it feel to be online? Psychotherapists’ self-perceptions in Telepsychotherapy sessions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:726964. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.726864

35. König, VL, Fontao, MI, Casari, LM, and Taborda, AR. Psychotherapists’ experiences of telepsychotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic in Argentina: impact on therapy setting, therapeutic relationship and burden. Ricerca in psicoterapia. (2023) 26:632. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2023.632

36. McKee, GB, Pierce, BS, Tyler, CM, Perrin, PB, and Elliott, TR. The COVID-19 Pandemic’s influence on family systems therapists’ provision of Teletherapy. Fam Process. (2021) 61:155–6. doi: 10.1111/famp.12665

37. Mc Kenny, R, Galloghly, E, Porter, CM, and Burbach, FR. ‘Living in a zoom world’: survey mapping how COVID-19 is changing family therapy practice in the UK. J Fam Ther. (2021) 43:272–4. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.12332

38. Morgan, AA, Landers, AL, Simpson, JE, Russon, JM, Case Pease, J, Dolbin-MacNab, ML, et al. The transition to teletherapy in marriage and family therapy training settings during COVID-19: what do the data tell us? J Marital Fam Ther. (2021) 47:320–1. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12502

39. Robbins, MS, and Midouhas, H. Adapting the delivery of functional family therapy around the world during a global pandemic. Glob Implement Res Appl. (2021) 1:109–1. doi: 10.1007/s43477-021-00009-0

40. Burgoyne, N, and Cohn, AS. Lessons from the transition to relational Teletherapy during COVID-19. Fam Process. (2020) 59:974–8. doi: 10.1111/famp.12589

41. Hardy, NR, Maier, CA, and Gregson, TJ. Couple teletherapy in the era of COVID-19: experiences and recommendations. J Marital Fam Ther. (2021) 47:225–3. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12501

42. Eppler, C. Systemic teletherapists’ meaningful experiences during the first months of the coronavirus pandemic. J Marital Fam Ther. (2021) 47:244–8. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12515

43. Johnsson, G, and Bulkeley, K. Practitioner and service user perspectives on the rapid shift to teletherapy for individuals on the autism spectrum as a result of covid-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:11812. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182211812

44. Smith-MacDonald, L, Jones, C, Sevigny, P, White, A, Laidlaw, A, Voth, M, et al. The experience of key stakeholders during the implementation and use of trauma therapy via digital health for military, veteran, and public safety personnel: qualitative thematic analysis. JMIR Form Res. (2021) 5:e26369. doi: 10.2196/26369

45. Weiskittle, R, Tsang, W, Schwabenbauer, A, Andrew, N, and Mlinac, M. Feasibility of a COVID-19 rapid response Telehealth group addressing older adult worry and social isolation. Clin Gerontol. (2022) 45:129–3. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2021.1906812

46. Choudhury, S, Yeh, PG, and Markham, CM. Coping with adverse childhood experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: perceptions of mental health service providers. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:975300. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.975300

47. Gangamma, R, Walia, B, Luke, M, and Lucena, C. Continuation of Teletherapy after the COVID-19 pandemic: survey study of licensed mental health professionals. JMIR Form Res. (2022) 6:e32419. doi: 10.2196/32419

48. von Wirth, E, Meininger, L, Adam, J, Woitecki, K, Treier, AK, and Döpfner, M. Satisfaction with videoconference-delivered CBT provided as part of a blended treatment approach for children and adolescents with mental disorders and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic: a follow-up survey among caregivers and therapists. J Telemed Telecare. (2023):311571. doi: 10.1177/1357633X231157103

49. Pires de Oliveira Padilha, P, Bertulies-Esposito, B, L'Heureux, S, Olivier, D, Lal, S, and Abdel-Baki, A. COVID-19 pandemic’s effects and telehealth in early psychosis Services of Quebec, Canada: will changes last? Early Interv Psychiatry. (2021) 16:862–7. doi: 10.1111/eip.13227

50. Eguia, KF, and Capio, CM. Teletherapy for children with developmental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines: a mixed-methods evaluation from the perspectives of parents and therapists. Child Care Health Dev. (2022) 48:963–9. doi: 10.1111/cch.12965

51. van Aafjes-Doorn, K, Békés, V, Prout, TA, and Hoffman, L. Practicing online during COVID-19: psychodynamic and psychoanalytic therapists’ experiences. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. (2022) 70:665–4. doi: 10.1177/00030651221114053

52. Bate, J, and Malberg, N. Containing the anxieties of children, parents and families from a distance during the coronavirus pandemic. J Contemp Psychother. (2020) 50:285–4. doi: 10.1007/s10879-020-09466-4

53. Mishkin, AD, Cheung, S, Capote, J, Fan, W, and Muskin, PR. Survey of clinician experiences of Telepsychiatry and Tele-consultation-liaison psychiatry. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. (2022) 63:334–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaclp.2021.10.005

54. Taylor, CB, Fitzsimmons-Craft, EE, and Graham, AK. Digital technology can revolutionize mental health services delivery: the COVID-19 crisis as a catalyst for change. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:1155–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.23300

55. Vitiello, E, and Sowa, NA. Socially distanced emergencies: clinicians’ experience with Tele-behavioral health safety planning. Psychiatr Q. (2022) 93:905–4. doi: 10.1007/s11126-022-10000-z

56. Hertlein, KM, Drude, KP, Hilty, DM, and Maheu, MM. Toward proficiency in telebehavioral health: applying interprofessional competencies in couple and family therapy. J Marital Fam Ther. (2021) 47:359–4. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12496

Keywords: telemedicine, psychotherapy, mental health services, PRISMA, digital mental health

Citation: Tajan N, Devès M and Potier R (2023) Tele-psychotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mini-review. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1060961. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1060961

Received: 04 October 2022; Accepted: 14 June 2023;

Published: 05 July 2023.

Edited by:

Jeanette Audrey Waxmonsky, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, United StatesReviewed by:

Naoto Kuroda, Wayne State University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Tajan, Devès and Potier. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicolas Tajan, dGFqYW4ubmljb2xhc3BpZXJyZS4ybUBreW90by11LmFjLmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.