95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry , 18 August 2022

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.949077

This article is part of the Research Topic Psychosexual Health and Sexuality: Multi-disciplinary Considerations in Clinical Practice View all 10 articles

Iraklis Mourikis1

Iraklis Mourikis1 Ioulia Kokka1*

Ioulia Kokka1* Elli Koumantarou-Malisiova1

Elli Koumantarou-Malisiova1 Konstantinos Kontoangelos2

Konstantinos Kontoangelos2 George Konstantakopoulos2,3

George Konstantakopoulos2,3 Charalabos Papageorgiou1,4

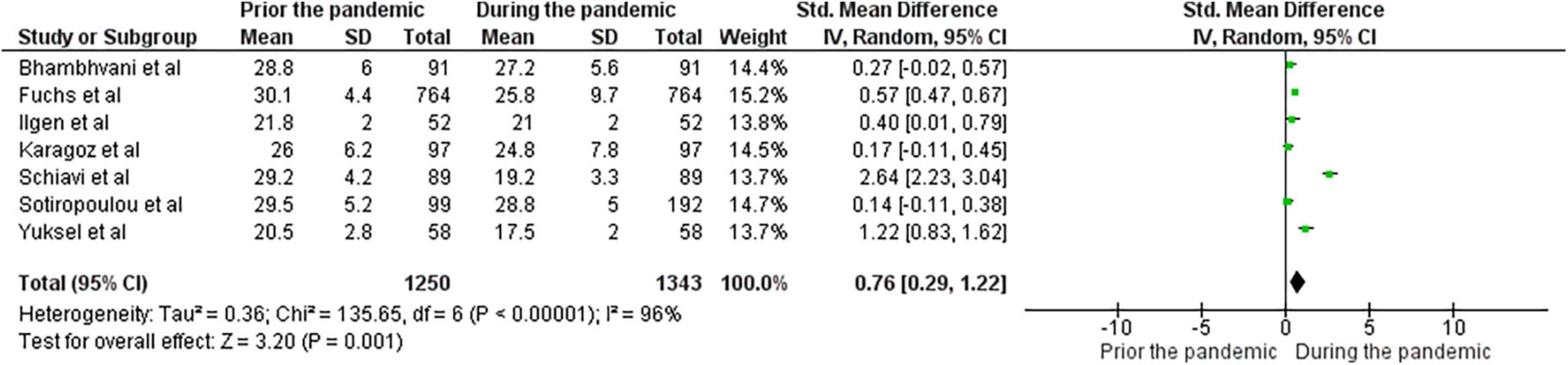

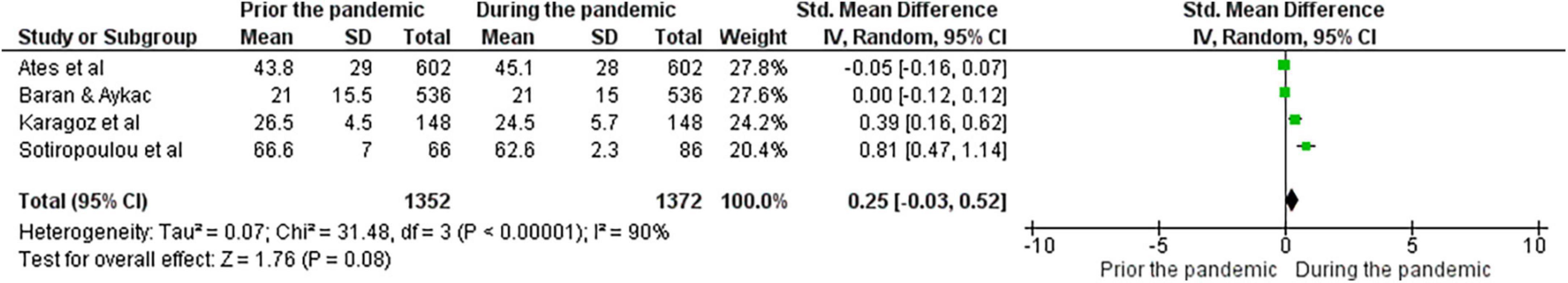

Charalabos Papageorgiou1,4Implemented social distancing measures may have forestalled the spread of COVID-19, yet they suppressed the natural human need for contact. The aim of this systematic review was to explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult sexual wellbeing and sexual behavior. An extensive search in Pubmed, Scopus, and PsycInfo databases based on PRISMA guidelines was conducted. After applying specific eligibility criteria, screening resulted in 38 studies. Results were drawn from 31,911 subjects and outlined the negative effect of the pandemic in sexual frequency, function, satisfaction, and the behavioral changes regarding masturbation and internet-based practices. Meta-analyses of the drawn data on 1,343 female, and 1,372 male subjects quantified the degree of sexual function change during the COVID-19 pandemic vs. prior the pandemic. A random effects model revealed the significant negative impact of the pandemic on female sexual function (SMD: 0.76, 95% CI:0.74 to 1.59), while no significant change was found for the males (SMD: 0.25, 95% Cl: −0.03 to 0.52). Significant heterogeneity was identified across included studies (p < 0.00001, I2 = 97%, I2 = 90% for females and males, respectively). As part of the global health, sexual wellbeing should be on the focus of clinicians and researchers.

In response to the exponential growth in the COVID-19 infections’ number, nations worldwide implemented lockdowns and extensive -strict or more lose- measures, which had short- and long-term effects on health systems, education, economy, and several other societal segments (1–4). The restrictions were implemented with a solid purpose to mitigate the spread of the virus, yet they suppressed the natural human need for contact, and seem to have taken a toll on people’s mental wellbeing. Scientific evidence so far suggest that social distancing during the pandemic has led to higher levels of stress, and agitation (5). Leveraging data from studies in the midst of the restrictions around the globe reported elevated irritability and mood swings (6), and increases in both depressive and anxiety disorders (7), findings supported by meta-analytic reports (8).

The pandemic of COVID-19 could be perceived as a new type of trauma. Even though it does not fall into any of the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) models, the global scale of this stressor and the likelihood of this virus to become life threatening may result in similar symptomatology (9). For example, a large cross-national study highlighted that individuals who were infected or were afraid of getting infected demonstrated PTSD-like symptoms, introducing a “pathogenetic event memory model of traumatic stress” (10). Research has outlined that mental and sexual health undoubtfully share a strong, bidirectional link (9, 10). A large number of psychiatric anxiety-related entities demonstrate symptomatology which affect sexual wellbeing. The adverse relationship of anxiety and sexual gratification has been well documented (11, 12), as these indicators are inextricably linked to sexual desire, arousal, and satisfaction (13). Under chronic stressful circumstances, even though both males and females demonstrate increased sexual desire probably as a means of psychological relief, stressors prevent the progression of desire to actual sexual intercourse (14), resulting in reduced sexually physical contacts (15, 16). Complementary, international health associations such as WHO and CDC have highlighted the positive impact of sexual wellbeing on mental health. A healthy sexual life may function as a protective factor against psychopathology (17), while frequent sexual activity acts as a safeguard toward psychological wellness (18).

In the context of psychologically burdening feelings during the pandemic, physical intimacy -which could be considered as one of the core expressions of connection between romantic partners- could not have stayed intact, and alterations on people’s sexual relationships during the pandemic were expected. Nevertheless, given the fact that each sexual act is a multi-sensory experience that can take multiple forms, body contact is not always mandatory. Thereby, the question whether the COVID-19 pandemic has affected or altered the sexual wellbeing and behavior of individuals arises.

Researchers from various countries have tried to shed light on the impact of the pandemic on sexual health, and preliminary results have shown its influence on various aspects of sexual wellbeing (18, 19). However, drawing a clear conclusion based on the studies of the field could be misleading due to the diversity of the recruited samples. A few efforts to systematically approach findings on the matter have been attempted. To the authors’ knowledge, these were limited and relevant to safe sexual practices regarding transmission of the virus (20), sexual minorities (21), addressed only female subjects (22), or evaluated solely sexual function (23). Thus, the primary aim of this review was to systematically explore the potential impact of COVID-19 pandemic on aspects of sexual wellbeing, quantify the change with respect to sexual function, and identify probable behavioral changes.

The study was designed according the PRISMA statement guidelines (24), in order to identify papers relevant to sexual wellbeing and sexual behavior during the pandemic. Stages of research incorporated problem formulation, thorough search of the existing research in the field, data extraction and evaluation, and finally data analysis and presentation. Studies included in this review followed specific inclusion/exclusion criteria as indicated below. Sexual wellbeing is a broad construct, which lacks a sharp definition, expanding from sexual self-esteem to sexual experiences (25). For the purpose of this study, wellbeing is conceptualized as including pillars of sexual intimacy such as frequency, desire, function, and satisfaction.

For a study to be eligible, it had to evaluate relevant to sexual wellbeing aspects (e.g., sexual function/dysfunction, activity, satisfaction etc.) and/or sexual behaviors. The study had to involve adult-only subjects, regardless of gender, age, sexual orientation, and relationship/marital status. Study groups had to derive from the general population but not on subjects with sexual dysfunction established prior the pandemic. The studies had to be published in the English language by peer-reviewed journals. Studies including females during pregnancy or post-partum were excluded, as these states have been proven to affect sexual function in a negative fashion (26, 27). Studies that included subjects with mental illnesses were excluded, because of the effect specific psychotropic medication can have on sexual function (28). Studies that investigated the biological impact of the virus on sexual function of COVID-19 survivors were also excluded. Research protocols without providing sufficient data were not included as well.

xPubmed, Scopus, and PsycInfo databases were thoroughly searched for relevant studies from the 1st until the 28th of March 2022. Research was conducted by two reviewing investigators, using the following terms: “sexual function” OR “sexual dysfunction” OR “sexual activity” OR “sexual health” OR “sexual satisfaction” and “sexual behavior” OR “sexual practices” OR “sexual habits” AND “COVID-19” OR “coronavirus 2019” OR “lockdown” OR “pandemic” OR “quarantine” and were adopted accordingly when necessary. Titles, keywords, and abstracts of each study were screened for eligibility. A backward search (hand search of reference lists) of included papers was conducted to identify additional studies relevant to the topic. All yielded studies were assessed according to the eligibility criteria.

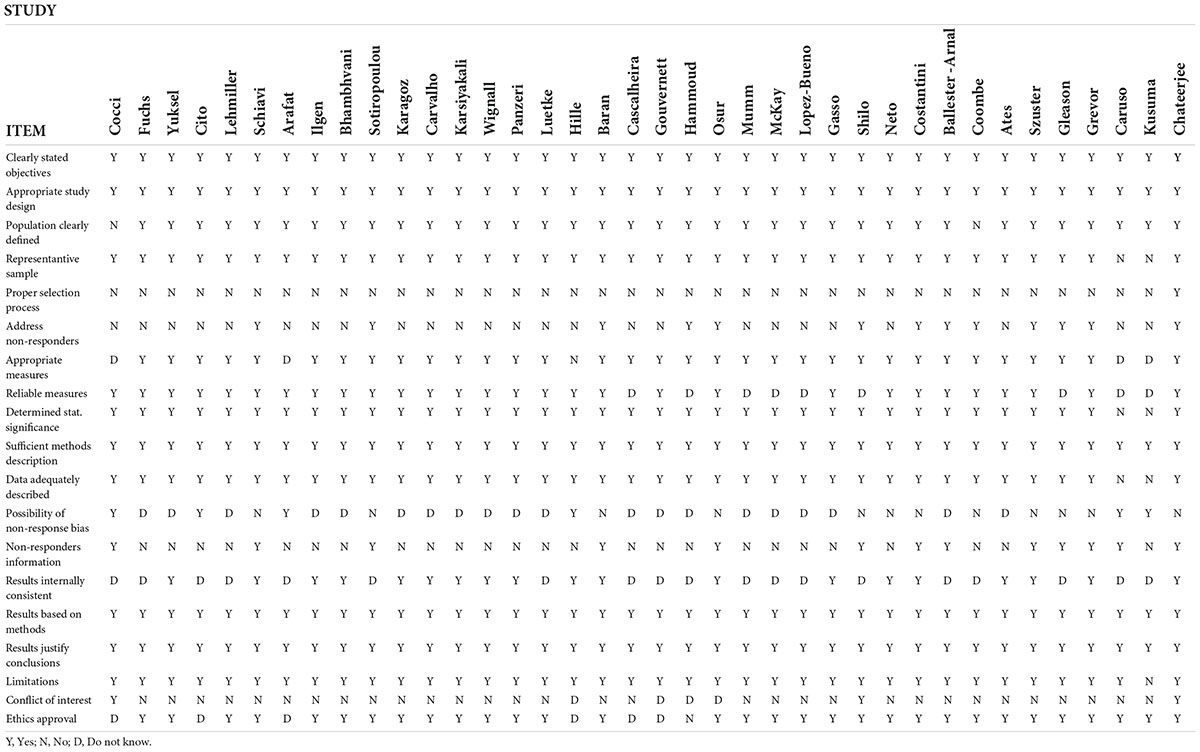

Data extraction included country of origin, time point of the pandemic during which the study was held, the sample size of each study, participants’ mean age and gender, the aspect of sexual wellbeing under investigation, the measurements used, the main outcomes of individual studies, and any other piece of information required for the quality evaluation. The AXIS Appraisal Tool was used to assess each study’s quality (29). AXIS consists of 20 items with each measuring a different aspect of a study’s quality. The aim of the tool is to assist systematic interpretation of observational studies. Each question of the tool can be answered with “yes,” “no” or “do not know,” yet it is not used to generate a total quality score, due to the well-known problems associated with such scores (30). The procedure of data extraction was held by two reviewers. The quality of evidence was assessed with the use of the Grade of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation criteria (GRADE) (31). The criteria that were assessed for each study was sampling issues, consistency of methods and findings and precision of data curation.

A quantitative synthesis of findings regarding sexual function was performed for the studies that provided adequate information. The difference between established indices of sexual function (e.g., International Index of Erectile Function, Female Sexual Function Index etc.) before and during the pandemic was calculated using the standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The Z-test was used to determine the significance of the pooled SMD. The tau2 statistic was used to examine the standard deviation of underlying effects across studies. A random-effect model was applied after calculating Cochran’s Q-statistic (p < 0.05) and I2 test. A visual examination of the funnel plots was performed to estimate the publication bias. The statistical significance level was set at 5% (p < 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed using the Review Manager software (Version 5.4, the Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark).

The initial search yielded 694 studies. After removing duplicates, and 611 titles and abstracts were screened, 95 articles were fully assessed. 57 of them were excluded for not meeting with the eligibility criteria. The final step of research resulted in 38 studies. Detailed screening procedure is illustrated in Figure 1.

All studies were observational, and more specifically of cross-sectional design. The majority was conducted in Europe (n = 23) and during the first semester of the pandemic (n = 33), with 31,911 recruited subjects in total. Mean age of the participants was 34.5 years for 32 of the studies; six of them provided only the lower age limit for participation (>18 years old). Mean percentage of female participants was 64.6% among 20 studies. Nine of them examined solely female populations, six of them solely males, while one study did not clarify participants’ gender distribution. Five of the studies included exclusively coupled (married/cohabiting/non-cohabiting) participants. Four and six studies included exclusively homosexual and heterosexual participants, respectively. Five of the studies included participants differentiating their gender identity from the dyadic system (woman/man). Apart from the instruments and questionnaires used to evaluate sexual wellbeing, almost half of the included studies used tools to assess the mental state or wellbeing of their participants (n = 18). Thirteen studies used a combination of weighted questionnaires and structured interviews, 13 used solely weighted questionnaires, and 12 solely structured inquiries. Main characteristics of included studies are outlined in Table 1. Among the included studies frequency of sexual intercourse, general sexual satisfaction, sexual function, and specific sexual behaviors were examined.

The domain of sexual frequency was examined by a large portion of the included studies (n = 21). Participants were asked to report their sexual frequency on a weekly basis compared to the period prior the pandemic. In the majority of the studies sexual frequency referred exclusively to partnered sexual practices (mutual masturbation, vaginal/anal penetration etc.), while in one study masturbatory or other solo activities were examined. Eleven of them found a statistically significant decrease in the number of sexual interactions during the pandemic (32–42). Notably, one study reported that about 60% of their participants did not engage in any form of partnered sexual intercourse since the outbreak of COVID-19 (39). Six of the included studies reported a decrease in the frequency of sexual activity (39, 43–48), and the proportions of participants reporting decrease ranged from 14 to 53%. However, the reduction in these studies was not statistically significant. For two of the studies no change was found (49, 50), while one, which examined the frequency of both partnered and solo practices (e.g., masturbation), reported increased frequency of sexual activity (51). Only one study found statistically significant increase in partnered sexual activity, with almost 30% being sexually active more than three times per week (52).

Sexual function and potential indications of sexual dysfunction were explored by 14 of the included studies. The majority of these studies (n = 12) examined this domain with the Female Sexual Function Index and the International Index of Male Function while the remaining with questionnaires structured by the researchers, and results could be considered contradicting. Eight included solely female participants, seven of which compared their results with pre-COVID data. Among them two reported statistically significant decreases in all domains of sexual function (desire, arousal, lubrication, arousal, satisfaction, and pain) (40, 45), and one came into similar decreases, yet those were statistically insignificant (53). Two of them found significant decreases for the global sexual function, but when subdomains were accessed separately, they concluded in statistical decrease only for arousal, lubrication, and satisfaction (42, 50). In two studies sexual function was evaluated for both male and female participants and no significant change was found for either of their subgroups (48, 54). In contrast, another study reported significant decreases for their female participants but only for the lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction subdomains of sexual function, whereas significant decreases in global function and erectile and orgasmic function, and satisfaction sub-domains were found for their male participants (55). Two of the studies found that lowered sexual function was present only when the psychological burden of the restrictions was assessed as high (56), and mostly for females and older participants (57). Three of the included studies evaluated solely sexual desire. One found decrease for males and females but this was significant only for females (58), while the second one reported significant decrease for both sexes (37). Though Cito et al. reported a decreased number of sexual intercourses, they found stable and in a subset of the subjects increased levels of sexual desire (34). Ates et al found a significant reduction in IIEF total scores, but a significant increase for the subscale of sexual function, and significant increase in the premature ejaculation diagnostic tool (32).

General satisfaction deriving from the sexual life of individuals was examined by 15 of the included studies. One of the studies concluded in improved levels of satisfaction for more than 50% of their participants (49), while in one stability (22%) and improvement (49%) was found (59). Two of the studies found that only a small portion of their participants reported decreased sexual satisfaction and, akin to other studies, this occurred only in those demonstrating high levels of anxiety (53, 56). Five of them found a statistically significant decrease, while for one of them this was more prominent for the female participants (34, 41, 60–62). Interestingly, in one of them 50% reported complete absence of satisfaction (60). Among four of the studies, the reported deteriorated satisfaction ranged from 41.3 to 50% (39, 43, 63, 64), while experiencing fear and anxiety for contracting the virus and increased depressive symptomatology was significantly associated with lower sexual satisfaction (33, 41). Mumm et al who included solely males, resulted in increased sexual satisfaction but only for those of hetero- and homosexual orientation, and not for bisexual men (52).

Seventeen of the included studies attempted to report on possible behavioral changes with respect to sexual life, such as masturbation frequency, online activities etc. Masturbation was examined by seven studies. All found a significant increase of masturbation (39, 43, 52, 55, 61), and the percentages of this increase ranged from almost 15 (44) to 40% (60) of the participants. On the contrary, three of the studies reported the exact opposite; a decrease in masturbation was found (58), however this was significant only for participants in stable and cohabiting relationships (36, 37). Digital and internet-based sexual practices were examined by a portion of the studies (n = 6). Three of them found an increase in pornography use, and this was reported by a similar percentage of participants (≈20%) across all studies (58, 65, 66). A 33% increase in cybersex was reported by one of the studies (67), while one found that almost 30% of their participants created and shared sexual, digital content for the first time (68), and one reported an increase in dating applications use and virtual dating (44). Changes in the sexual repertoire were additionally examined. Cascalheira et al found that more than 30% of their participants expanded their solo sexual practices such as fantasizing more (65), while Lehmiller et al reported additions in their participants’ sex lives, which included new positions during intercourse (1/5 of the participants), sharing (13%) and acting (8.5%) on fantasies, and using sex toys (7.3%) (39). Sexual positions were examined by one more study, which found statically significant decrease in face-to-face positions in order to avoid transmission of the virus (32). Behaviors of intimacy were similarly deteriorated, with two studies reporting significant reduction of romantic practices such as hugging or cuddling (35, 36). Two of the included studies examined the use of contraceptive measures, and results were contradicting; one revealed a more than 50% decline for non-cohabiting partners (69), and one reported no change (47). Three studies, which all included males who have sex with males, concluded in contradicting results; two found increased masturbation and cybersex (67), and avoidance of casual sexual intercourse with this reaching 15times fold reduction (46), while Shilo and Mor reported that almost half of their participants continued casual intercourse, but with limited repertoire (66). A summary of the findings are reported in Table 2.

Some of the included studies tried to identify factors which mediated the relationship between sexual wellbeing and the pandemic. Factors regarding sociodemographic characteristics, as well as psychological characteristics were found to affect this relationship. The most prominent characteristic was that of gender; women appeared as mostly affected in a negative manner (43, 58, 61, 62) Socio-economic status (39), and reduced salary due to work suspension (34), unemployment (37, 59), lack of privacy (43, 48), younger age (39, 60, 66), and being single (69) were identified among these factors. With respect to psychological characteristics, increased depressive symptomatology (48, 53, 60), anxiety (48, 54), stress (32, 48), and loneliness (41) were identified τo negatively affect sexual wellbeing. In addition, fear of contracting the virus was found to act as a restrictive factor of sexual wellbeing (41).

Two independent reviewers assessed the quality of individual studies with the Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS). Each study’s quality was evaluated independently by each reviewer and juxtaposed their results; no disagreements occurred. Overall quality did not vary significantly across studies, with most of them being of moderate quality. The main quality issues were the lack of information on non-responders, and questionable internal consistency of several studies due to the use of not validated instruments. An additional quality issue regarding sampling that needs to be addressed is the fact that all of the studies recruited their samples online, questioning their representativeness. Detailed outcomes of the quality evaluation are presented in Table 3. The GRADE evaluation method uses a 4-level system of evidence grading, with randomized control trial being the only type of study design that can receive 4/4 (high level of evidence). Given that all included studies were observational, the highest possible grade was 3/4 (moderate level of evidence), unless there was a reason to upgrade or downgrade. The risk of bias was assessed by evaluating the representativeness of sampling, and the measurement and reporting bias. The vast majority of the studies downgraded to 2/4, given the unjustified samples’ size (n = 35), and the use of structured inquiries to evaluate outcomes of interest (n = 15).

Table 3. Quality assessment of individual studies included in the systematic review based on the AXIS tool.

Among the included studies, only seven provided the required pre- and during-the pandemic data for their female participants, and four for their male participants. With respect to females, the random effects model revealed that the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) total scores showed a statistically significant difference between pre-COVID and during-COVID total scores for their participants (SMD: 0.76, 95% CI:0.74 to 1.59, z summary effect size p = 0.01) (Figure 2). Regarding males, the model showed that IIEF total scores demonstrated no significant difference between pre-COVID and during-COVID total scores for their participants (SMD: 0.25, 95% Cl: −0.03 to 0.52, z summary effect size p = 0.08) (Figure 3). A significant heterogeneity was identified across included studies (p < 0.00001, I2 = 97%, I2 = 90% for females and males, respectively). Visual examination of the funnel plots indicated the risk of publication bias over included studies (Figures 4, 5). Given the high heterogeneity of the studies, the authors intended to perform a meta-regression to investigate whether the results were influenced by other covariates. Due to the lack of adequate data, this was not feasible. However, among the covariates, the severity of the pandemic among different countries, the different type of restrictions implemented, or the different relationship status among the participants could be identified.

Figure 2. Forest plot presenting the meta-analysis based on SMDs for the effect of the pandemic on female sexual function.

Figure 3. Forest plot presenting the meta-analysis based on SMDs for the effect of the pandemic on male sexual function.

This systematic review aimed to examine the existing body of evidence regarding the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sexual wellbeing and sexual behaviors of adults. Findings on the matter appeared to be rather consistent across studies, and partially supported by the meta-analytic outcomes. A deterioration of sexual wellbeing with lowered frequency of sexual activity, diminished satisfaction and, for some, problematic sexual function was found, whereas in only a small number of studies the pandemic was presented as an opportunity to reinvent intimate relationships. The relation of the participants’ psychological state and sexual wellbeing was evident. Sexual wellbeing and discomforting feelings, such as anxiety, increased stress, depressive symptomatology, and perceived lower quality of life were associated in a large portion of the included studies. However, the causal relationship could not be defined with certainty. As far as changes in sexual behavior are concerned, results were rather contradicting regarding masturbation, while a rise in internet-based sexual practices, and changes in sexual repertoire were documented.

Sexual function was the only aspect of sexual wellbeing for which data could be drawn to perform a meta-analysis. Results from the quantitative synthesis revealed a statistically significant negative effect of the pandemic on female sexual function. Taking into consideration that for most of the studies lower sexual function was linked to lowered quality of life and increased anxiety levels, this came in line with previous findings, which showed that chronic daily stressors can affect genital arousal and impair female sexual function (70). On the contrary, meta-analytic findings for the male sexual function showed no significant alteration. It may be supported that the meta-analytic findings outline the moderating role of gender, which emerged in several of this review’s studies (43, 48, 56, 58, 62). This could be partly explained by the fact that males are less susceptible to chronic stress (71). Because of different levels of exposure to psychological and social pressure, and increased vulnerability due to biological factors, women are more likely to be affected by stressful circumstances compared to men (72). However, it could be argued that the meta-analytic results for the male participants are not representative of the actual case. Among the included studies, those with the largest male samples demonstrated statistically significant reductions in sexual function, even though the comparison with pre-pandemic scores was not feasible. An additional argument could be that the IIEF index perceives male sexual function in a somehow narrow manner, since it examines solely penile rigidity and penetration, without assessing other ways males can engage in and enjoy sexual intercourse. Complimentary, a plausible explanation for the statistically insignificant findings could be the reported increase of medication regarding male sexual dysfunction. A recent study found that between February and December of 2020 a 67% increase in sales of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5-Is) was noted in the United States, and more particularly, an 85% increase of tadalafil sales (73). This suggests that men’s function might not have been affected, but pharmaceutical assistance was required.

With respect to sexual frequency, the limited number of intercourses could be characterized as expected. Literature has shown that emotional and physical intimacy play a crucial role in sexual desire and maintenance of sexual activity (74), while the time shared between non-cohabiting partners, is the predominant predictor of negatively affected sexual interactions (75). Taking into consideration that many of the studies were conducted during complete quarantines and included participants who did not cohabit with their partner (36, 37, 58, 65), the impact of relationship status and a decrease in the frequency of partnered sexual interaction were anticipated. Surprisingly, this decrease applied for co-habiting partners in one of the studies as well (45). Though desire for sexual intercourse was reported as insignificantly changed or even higher by some of the studies, this did not progress into actual contact. This could be explained by findings which reported that the fear of contracting the virus minimized physical contact between partners (76). In addition, other findings supported that ruminating COVID-19-related conversations reduced the couples’ ability to avoid conflict, and decreased intimate expressions that could progress into sexual contact (77). The disagreement found between sexual desire and sexual intercourse, comes in accordance with what was found by Morokqff and Gillilland; males and females under the same stressful circumstances did demonstrate higher sexual desire, yet stressors prevented the progression of desire to actual sexual intercourse (78). Though sexual desire and frequency were expected to down escalate as age of participants increased (79), a portion of the studies did not verify the role of age in sexual life (37, 39, 45).

Likewise, the overall satisfaction deriving from sexual life was mostly affected in a negative fashion. Results showed that low sexual satisfaction was associated with health-related anxiety (33), something that has been documented; literature has highlighted the unfavorable relationship of anxiety and sexual contentment (80). Satisfaction deriving from sexual life is an integral part of sexual wellbeing and overall health (81). An important line of research has repeatedly shown that mentally healthy individuals are more satisfied by their intimate relationships, and vice versa; those with a more satisfying sex life exhibit a healthier mental state (80). However, the fact that some studies reported no change in satisfaction (49, 59) or other aspects of sexual wellbeing (48, 54) should not be neglected.

Based on the results, different aspects of sexual behaviors were found to have changed or to be newly added in individuals’ lives. A significant increase was noted with respect to masturbation (52, 55, 60, 61, 67) and pornography use (58, 61, 65, 66). An plausible explanation for this increase could be the fact that pornography has been found to be utilized as a stress coping method (82), or as a means to avoid emotional burden (83). However, the reliability of these findings should be considered carefully, as higher frequency of masturbatory practices appear more in males than females (84), and some of these studies have included solely male participants in their samples, while some samples constituted mostly by males. In addition, increases were reported with respect to online sexual activities such as cybersex, virtual dating, and creating and sharing sex-related digital content. Indeed, statistics on the topic has revealed the increase in dating applications’ downloads (85). Given that during the pandemic initiating new intimate relationships could be perceived as “unsafe,” virtual dating applications might offer a “safer” way to establish an alternative form of connection. It appears as intimacy quickly evolved and grew through online spaces, from emotional bonding via applications (86) to sex parties held via Zoom (87).

A wide heterogeneity was noted across studies. Each was conducted at different time points with respect to the severity of the pandemic. For example, a number of studies were conducted in countries with high number of infections and life losses, whereas in others -such as the example of Greece- studies were conducted when only a few cases of COVID-19 were being reported on a daily basis. Thereby, the impact of the pandemic could be characterized nothing but greatly variant. Thus, the implemented measures of social distancing were different when each study was conducted. For example in some European countries where the pandemic wave was milder restrictions were limited solely to the number of individuals that could gather, whereas in other countries complete ban of circulation was implemented. Another explanatory factor of the high heterogeneity could be the diverse samples between studies. Sampling varied significantly with respect to size, and demographic characteristics. Some included as small samples as of a few dozens of participants, while others recruited larger samples. In addition, both between and within studies sampling varied regarding gender, and relationship status; some included solely heterosexual or non-heterosexual participants, others included solely females or solely males, while others recruited mixed samples. The same issue occurred with respect to relationship status; some recruited exclusively married/cohabiting partners, while others solely single participants. The “when” and “how” is of great importance, as they could be the key factors in understanding the discrepancy of the findings.

Among the strengths of the present study is the systematic approach of the available data, including the search strategy, the selection process, as well as the extraction and presentation of information. The explicit eligibility criteria ensured the exclusion of misleading factors, such as established sexual or mental disorders prior the pandemic, while the data analysis assisted in the identification of trends between the included studies.

However, this review bears certain limitations. Though there was an effort to evaluate the impact of the stressful conditions formed by the pandemic on the sexual wellbeing and sexual behavior of individuals, specific factors limit the generalization of the findings. The fact that al included studies recruited convenient samples via online platforms constitute their findings vulnerable to selection and non-response biases, particularly regarding sexual behavior data. The meta-analysis was conducted on a small number of studies (especially for the male participants), which did not perform power calculation for their sample sizes, and thereby, their findings could be characterized as questionable. In addition, given the fact that a meta-regression could not be conducted, the mediating effect of other factors could not be determined.

COVID-19 has forced circumstances such as limitation of the usual social connection and, in some cases, the sense of constant life threat (88), which mental health professionals should take into consideration when treating patients. They must be prepared to desensitize mental health patients regarding irrational fears deriving from the pandemic. In addition, the higher risk of mental health complication for individuals with pre-existing mental conditions should be under consideration (89). In relation to COVID-19 preventive measures and restrictions, sexual well-being seems to have been negatively influenced across several domains. As it appeared, the state of anxiety and stress could be considered as the key explanatory factor; those with experiencing stronger distress due to the restrictive measures seemed to have a less satisfying sexual life. Simultaneously, a rise in specific internet-based sexual behaviors such as pornography use, and cybersex were also prominent as alternative ways of sexual relief. Given that sexual health is an integral part of general health, this paper’s findings highlight that when the pandemic is surpassed and individuals begin to heal from this traumatic experience, surveillance and measurement of the final imprint on sexual wellbeing should be on the focus of clinicians and researchers.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

IM designed the study. IM and IK conducted the search and study selection and drawn the first draft of the manuscript. EK-M and KK extracted the data. IK performed the meta-analyses. GK and CP conducted the review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by the Regional Governor of Attica and co-funded by the “Athanasios Martinos and Marina Foundation AMMF” and the “AEGEAS Non-Profit Civil Company”.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Bergman YS, Shrira A, Palgi Y, Shmotkin D. The moderating role of the hostile-world scenario in the connections between COVID-19 worries, loneliness, and anxiety. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:645655. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645655

2. Brewer M, Gardiner L. The initial impact of COVID-19 and policy responses on household incomes. Oxford Rev Econ Policy. (2020) 36(Suppl. 1):S187–99. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/graa024

3. Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, Lovell K, Halvorson A, Loch S, et al. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics. (2020) 146:e2020016824. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016824

4. Prime H, Wade M, Browne DT. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. (2020) 75:631–43. doi: 10.1037/amp0000660

5. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. (2020) 395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

6. Rubin GJ, Wessely S. The psychological effects of quarantining a city. BMJ. (2020) 368:m313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m313

7. Taquet M, Holmes EA, Harrison PJ. Depression and anxiety disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic: Knowns and unknowns. Lancet. (2021) 398:1665–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02221-2

8. Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health. (2020) 16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

9. Unützer J, Kimmel RJ, Snowden M. Psychiatry in the age of COVID -19. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:130–1. doi: 10.1002/wps.20766

10. Bridgland VME, Moeck EK, Green DM, Swain TL, Nayda DM, Matson LA, et al. Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0240146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240146

11. Braithwaite S, Holt-Lunstad J. Romantic relationships and mental health. Curr Opin Psychol. (2017) 13:120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.001

12. Mourikis I, Antoniou M, Matsouka E, Vousoura E, Tzavara C, Ekizoglou C, et al. Anxiety and depression among Greek men with primary erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2015) 14:34. doi: 10.1186/s12991-015-0074-y

13. Nimbi FM, Tripodi F, Rossi R, Simonelli C. Expanding the analysis of psychosocial factors of sexual desire in men. J Sex Med. (2018) 15:230–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.11.227

14. Eplov L, Giraldi A, Davidsen M, Garde K, Kamper-Jørgensen F. Original research–Epidemiology: Sexual desire in a nationally representative danish population. J Sex Med. (2007) 4:47–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00396.x

15. Bodenmann G, Atkins DC, Schär M, Poffet V. The association between daily stress and sexual activity. J Fam Psychol. (2010) 24:271–9. doi: 10.1037/a0019365

16. Hamilton LD, Meston CM. Chronic stress and sexual function in women. J Sex Med. (2013) 10:2443–54. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12249

17. Veening JG, de Jong TR, Waldinger MD, Korte SM, Olivier B. The role of oxytocin in male and female reproductive behavior. Eur J Pharmacol. (2015) 753:209–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.045

18. Mollaioli D, Sansone A, Ciocca G, Limoncin E, Colonnello E, Di Lorenzo G, et al. Benefits of sexual activity on psychological, relational, and sexual health during the COVID-19 breakout. J Sex Med. (2021) 18:35–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.10.008

19. Sansone A, Mollaioli D, Cignarelli A, Ciocca G, Limoncin E, Colonnello E, et al. Male sexual health and sexual behaviors during the first national COVID-19 lockdown in a western country: A real-life, web-based study. Sexes. (2021) 2:293–304. doi: 10.3390/sexes2030023

20. Pennanen-Iire C, Prereira-Lourenço M, Padoa A, Ribeirinho A, Samico A, Gressler M, et al. Sexual health implications of COVID-19 pandemic. Sex Med Rev. (2021) 9:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2020.10.004

21. McGowan VJ, Lowther HJ, Meads C. Life under COVID-19 for LGBT+ people in the UK: Systematic review of UK research on the impact of COVID-19 on sexual and gender minority populations. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e050092. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050092

22. Dashti S, Bolghanabadi N, Ghavami V, Elyassirad D, Bahri N, Kermani F, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on female sexual function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Marital Ther. (2021) 48:520–31. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2021.2006842

23. Masoudi M, Maasoumi R, Bragazzi NL. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexual functioning and activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:189. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12390-4

24. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG The Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

25. Mitchell KR, Lewis R, O’Sullivan LF, Fortenberry JD. What is sexual wellbeing and why does it matter for public health? Lancet Public Health. (2021) 6:e608–13. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00099-2

26. Gutzeit O, Levy G, Lowenstein L. Postpartum female sexual function: Risk factors for postpartum sexual dysfunction. Sex Med. (2020) 8:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2019.10.005

27. Leite APL, Campos AAS, Dias ARC, Amed AM, De Souza E, Camano L. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction during pregnancy. Rev Assoc Med Bras. (2009) 55:563–8. doi: 10.1590/S0104-42302009000500020

28. Higgins A. Impact of psychotropic medication on sexuality: Literature review. Br J Nurs. (2007) 16:545–50. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2007.16.9.23433

29. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e011458. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

30. Jüni P. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA. (1999) 282:1054. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1054

31. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: A new series of articles in the journal of clinical epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64:380–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011

32. Ates E, Kazici HG, Yildiz AE, Sulaimanov S, Kol A, Erol H. Male sexual functions and behaviors in the age of COVID-19: Evaluation of mid-term effects with online cross-sectional survey study. Arch Ital Urol Androl. (2021) 93:341–7. doi: 10.4081/aiua.2021.3.341

33. Baran O, Aykac A. The effect of fear of covid-19 transmission on male sexual behaviour: A cross-sectional survey study. Int J Clin Pract. (2021) 75:e13889. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13889

34. Cito G, Micelli E, Cocci A, Polloni G, Russo GI, Coccia ME, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 quarantine on sexual life in Italy. Urology. (2021) 147:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.06.101

35. Grover S, Vaishnav M, Tripathi A, Rao TS, Avasthi A, Dalal P, et al. Sexual functioning during the lockdown period in India: An online survey. Indian J Psychiatry. (2021) 63:134. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_860_20

36. Hille Z, Oezdemir UC, Beier KM, Hatzler L. L’impact de la pandémie de COVID-19 sur l’activité sexuelle et les pratiques sexuelles des célibataires et des personnes en couple dans une population germanophone. Sexologies. (2021) 30:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.sexol.2020.12.010

37. Karsiyakali N, Sahin Y, Ates HA, Okucu E, Karabay E. Evaluation of the sexual functioning of individuals living in turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic: An internet-based nationwide survey study. Sex Med. (2021) 9:100279. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2020.10.007

38. Luetke M, Hensel D, Herbenick D, Rosenberg M. Romantic relationship conflict due to the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in intimate and sexual behaviors in a nationally representative sample of American adults. J Sex Marital Ther. (2020) 46:747–62. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2020.1810185

39. Lehmiller JJ, Garcia JR, Gesselman AN, Mark KP. Less sex, but more sexual diversity: Changes in sexual behavior during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Leisure Sci. (2021) 43:295–304. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2020.1774016

40. Schiavi MC, Spina V, Zullo MA, Colagiovanni V, Luffarelli P, Rago R, et al. Love in the time of COVID-19: Sexual function and quality of life analysis during the social distancing measures in a group of Italian reproductive-age women. J Sex Med. (2020) 17:1407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.06.006

41. Szuster E, Kostrzewska P, Pawlikowska A, Mandera A, Biernikiewicz M, Kałka D. Mental and sexual health of polish women of reproductive age during the COVID-19 pandemic – An online survey. Sex Med. (2021) 9:100367. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100367

42. Yuksel B, Ozgor F. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on female sexual behavior. Int J Gynecol Obstet. (2020) 150:98–102. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13193

43. Ballester-Arnal R, Nebot-Garcia JE, Ruiz-Palomino E, Giménez-García C, Gil-Llario MD. “INSIDE” project on sexual health in Spain: Sexual life during the lockdown caused by COVID-19. Sex Res Soc Policy. (2021) 18:1023–41. doi: 10.1007/s13178-020-00506-1

44. Coombe J, Kong FYS, Bittleston H, Williams H, Tomnay J, Vaisey A, et al. Love during lockdown: Findings from an online survey examining the impact of COVID-19 on the sexual health of people living in Australia. Sex Transm Infect. (2021) 97:357–62. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054688

45. Fuchs A, Matonóg A, Pilarska J, Sieradzka P, Szul M, Czuba B, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on female sexual health. IJERPH. (2020) 17:7152. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197152

46. Hammoud MA, Maher L, Holt M, Degenhardt L, Jin F, Murphy D, et al. Physical distancing due to COVID-19 disrupts sexual behaviors among gay and bisexual men in Australia: Implications for trends in HIV and other sexually transmissible infections. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2020) 85:309–15. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002462

47. Kusuma AHW, Brodjonegoro SR, Soerohardjo I, Hendri AZ, Yuri P. Sexual activities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Afr J Urol. (2021) 27:116. doi: 10.1186/s12301-021-00227-w

48. Panzeri M, Ferrucci R, Cozza A, Fontanesi L. Changes in sexuality and quality of couple relationship during the COVID-19 lockdown. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:565823. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565823

49. Arafat SMY, Alradie-Mohamed A, Kar SK, Sharma P, Kabir R. Does COVID-19 pandemic affect sexual behaviour? A cross-sectional, cross-national online survey. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 289:113050. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113050

50. Bhambhvani HP, Chen T, Kasman AM, Wilson-King G, Enemchukwu E, Eisenberg ML. Female sexual function during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Sex Med. (2021) 9:100355. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100355

51. López-Bueno R, López-Sánchez GF, Gil-Salmerón A, Grabovac I, Tully MA, Casaña J, et al. COVID-19 confinement and sexual activity in Spain: A cross-sectional study. IJERPH. (2021) 18:2559. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052559

52. Mumm JN, Vilsmaier T, Schuetz JM, Rodler S, Zati Zehni A, Bauer RM, et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic affects sexual behavior of hetero-, homo-, and bisexual males in Germany. Sex Med. (2021) 9:100380. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100380

53. Ilgen O, Kurt S, Aydin C, Bilen E, Kula H. COVID-19 pandemic effect on female sexual function. Ginekol Pol. (2021) 92:856–9. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2021.0084

54. Sotiropoulou P, Ferenidou F, Owens D, Kokka I, Minopoulou E, Koumantanou E, et al. The impact of social distancing measures due to COVID-19 pandemic on sexual function and relationship quality of couples in Greece. Sex Med. (2021) 9:100364. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100364

55. Karagöz MA, Gül A, Borg C, Erihan IB, Uslu M, Ezer M, et al. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on sexuality: A cross-sectional study among couples in Turkey. Int J Impot Res. (2020) 33:815–23. doi: 10.1038/s41443-020-00378-4

56. Carvalho J, Campos P, Carrito M, Moura C, Quinta-Gomes A, Tavares I, et al. The relationship between COVID-19 confinement, psychological adjustment, and sexual functioning, in a sample of portuguese men and women. J Sex Med. (2021) 18:1191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.04.007

57. Chatterjee SS, Bhattacharyya R, Chakraborty A, Lahiri A, Dasgupta A. Quality of life, sexual health, and associated factors among the sexually active adults in a metro city of India: An inquiry during the COVID-19 pandemic-related lockdown. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:791001. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.791001

58. Wignall L, Portch E, McCormack M, Owens R, Cascalheira CJ, Attard-Johnson J, et al. Changes in sexual desire and behaviors among UK young adults during social lockdown Due to COVID-19. J Sex Res. (2021) 58:976–85. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2021.1897067

59. Costantini E, Trama F, Villari D, Maruccia S, Li Marzi V, Natale F, et al. The impact of lockdown on couples’ sex lives. JCM. (2021) 10:1414. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071414

60. Cocci A, Giunti D, Tonioni C, Cacciamani G, Tellini R, Polloni G, et al. Love at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic: Preliminary results of an online survey conducted during the quarantine in Italy. Int J Impot Res. (2020) 32:556–7. doi: 10.1038/s41443-020-0305-x

61. Gleason N, Banik S, Braverman J, Coleman E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexual behaviors: Findings from a national survey in the United States. J Sex Med. (2021) 18:1851–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.08.008

62. Gouvernet B, Bonierbale M. COVID-19 lockdown impact on cognitions and emotions experienced during sexual intercourse. Sexologies. (2021) 30:e9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.sexol.2020.11.002

63. Neto RP, Nascimento BCG, Carvalho dos Anjos Silva G, Barbosa JABA, Júnior J, de B, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the sexual function of health professionals from an epicenter in Brazil. Sex Med. (2021) 9:100408. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100408

64. Osur J, Ireri EM, Esho T. The effect of COVID-19 and Its control measures on sexual satisfaction among married couples in Kenya. Sex Med. (2021) 9:100354. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100354

65. Cascalheira CJ, McCormack M, Portch E, Wignall L. Changes in sexual fantasy and solitary sexual practice during social lockdown among young adults in the UK. Sex Med. (2021) 9:100342. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100342

66. Shilo G, Mor Z. COVID-19 and the changes in the sexual behavior of men who have sex with men: Results of an online survey. J SexMed. (2020) 17:1827–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.07.085

67. McKay T, Henne J, Gonzales G, Gavulic KA, Quarles R, Gallegos SG. Sexual behavior change among gay and bisexual men during the first COVID-19 pandemic wave in the United States. Sex Res Soc Policy. (2021):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00625-3

68. Gassó AM, Mueller-Johnson K, Agustina JR, Gómez-Durán EL. Exploring sexting and online sexual victimization during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. IJERPH. (2021) 18:6662. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126662

69. Caruso S, Rapisarda AMC, Minona P. Sexual activity and contraceptive use during social distancing and self-isolation in the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. (2020) 25:445–8. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2020.1830965

70. ter Kuile MM, Vigeveno D, Laan E. Preliminary evidence that acute and chronic daily psychological stress affect sexual arousal in sexually functional women. Behav Res Ther. (2007) 45:2078–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.03.006

71. Olff M. Sex and gender differences in post-traumatic stress disorder: An update. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2017) 8(Suppl. 4):1351204. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1351204

72. Hallers-Haalboom ET, Maas J, Kunst LE, Bekker MHJ. The role of sex and gender in anxiety disorders: Being scared “like a girl”? Handbook Clin Neurol. (2020) 175:359–68. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-64123-6.00024-2

73. Hernandez I, Gul Z, Gellad WF, Davies BJ. Marked increase in sales of erectile dysfunction medication during COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. (2021) 36:2912–4. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06968-2

74. van Lankveld J, Jacobs N, Thewissen V, Dewitte M, Verboon P. The associations of intimacy and sexuality in daily life: Temporal dynamics and gender effects within romantic relationships. J Soc Pers Relat. (2018) 35:557–76. doi: 10.1177/0265407517743076

75. Karp C, Moreau C, Sheehy G, Anjur-Dietrich S, Mbushi F, Muluve E, et al. Youth relationships in the era of COVID-19: A mixed-methods study among adolescent girls and young women in Kenya. J Adolesc Health. (2021) 69:754–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.017

76. Ibarra FP, Mehrad M, Mauro MD, Godoy MFP, Cruz EG, Nilforoushzadeh MA, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sexual behavior of the population. The vision of the east and the west. Int Braz J Urol. (2020) 46(Suppl 1):104–12. doi: 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.s116

77. Merolla AJ, Otmar C, Hernandez CR. Day-to-day relational life during the COVID-19 pandemic: Linking mental health, daily relational experiences, and end-of-day outlook. J Soc Pers Relat. (2021) 38:2350–75. doi: 10.1177/02654075211020137

78. Morokqff PJ, Gillilland R. Stress, sexual functioning, and marital satisfaction. J Sex Res. (1993) 30:43–53. doi: 10.1080/00224499309551677

79. Karraker A, DeLamater J, Schwartz CR. Sexual frequency decline from midlife to later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2011) 66B:502–12. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr058

80. Carcedo RJ, Fernández-Rouco N, Fernández-Fuertes AA, Martínez-Álvarez JL. Association between sexual satisfaction and depression and anxiety in adolescents and young adults. IJERPH. (2020) 17:841. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030841

81. World Health Organization.Measuring sexual health: Conceptual and practical considerations and related indicators. Geneva: World Health Organization (2010).

82. Goldenberg JL, McCoy SK, Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J, Solomon S. The body as a source of self-esteem: The effect of mortality salience on identification with one’s body, interest in sex, and appearance monitoring. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2000) 79:118–30. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.1.118

83. Laier C, Brand M. Mood changes after watching pornography on the Internet are linked to tendencies towards internet-pornography-viewing disorder. Addict Behav Rep. (2017) 5:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2016.11.003

84. Jones JC, Barlow DH. Self-reported frequency of sexual urges, fantasies, and masturbatory fantasies in heterosexual males and females. Arch Sex Behav. (1990) 19:269–79. doi: 10.1007/BF01541552

85. Stunson M. Should you be hooking up during coronavirus pandemic? Tinder, bumble downloads surge. (2020). Available online at: https://www.kansascity.com/news/coronavirus/article242083236.html (accessed March 27, 2022).

86. Shaw D. Coronavirus: Tinder boss says “dramatic” changes to dating. (2020). Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-52743454#%3A%7E%3Atext%3DCoronavirushashada%22dramatic%2Cinstorefortheplatform.%26text%3DThisisnotsuchgood,premiumsubscriptionsforitsrevenue (accessed March 21, 2022).

87. Power J, Waling A. Online sex parties and virtual reality porn: Can sex in isolation be as fulfilling as real life? (2020). Available online at: https://theconversation.com/online-sex-parties-and-virtual-reality-porn-can-sex-in-isolation-be-as-fulfilling-as-real-life-134658. (accessed March 27, 2022).

88. Stewart DE, Appelbaum PS. COVID –19 and psychiatrists’ responsibilities: A WPA position paper. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:406–7. doi: 10.1002/wps.20803

Keywords: COVID-19 restrictions, sexual satisfaction, sexual function, sexual frequency, sexual behavior, pandemic outcomes

Citation: Mourikis I, Kokka I, Koumantarou-Malisiova E, Kontoangelos K, Konstantakopoulos G and Papageorgiou C (2022) Exploring the adult sexual wellbeing and behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 13:949077. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.949077

Received: 20 May 2022; Accepted: 20 July 2022;

Published: 18 August 2022.

Edited by:

Lawrence T. Lam, University of Technology Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Chao Xu, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Mourikis, Kokka, Koumantarou-Malisiova, Kontoangelos, Konstantakopoulos and Papageorgiou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ioulia Kokka, a29ra2EuaW91bGlhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; aW91bGlha29rQG1lZC51b2EuZ3I=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.