94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

COMMUNITY CASE STUDY article

Front. Psychiatry , 22 August 2022

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.947903

The number of wars in the world is on the rise. A number of studies have documented the devastating impact on the public and especially public mental health. Health care systems in low- and lower-middle income countries that are frequently already challenged by the existing mental health services gap cannot provide the necessary care for those displaced by war with existing services. This is especially the case in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) after the invasion of the terror organization ISIS in 2014. Most projects in post-conflict areas focus on short term basic psychological services and do not contribute to sustainable long-term capacity building of mental health services. An “Institute for Psychotherapy and Psychotraumatology” was therefore founded in order to train local specialists on a professional level with evidence-based methods adapted to culture and create sustainable long-term structures for psychotherapeutic treatment in the KRI. To achieve this, a number of measures were implemented, including the creation of a “Master of Advanced Studies of Psychotherapy and Psychotraumatology” in collaboration with local communities and the regional University. Two cohorts of students have successfully finished the master’s program and a third cohort are expected to graduate in 2023. Improving the capacity of local health care services to provide low-barrier, professional psychotherapeutic care in post-conflict regions supported by the innovative model presented in this article can be expected to improve the burden of psychological problems and contribute to peacebuilding.

At the end of 2020, 82.4 million people worldwide were fleeing persecution, conflict, violence and human rights abuses according to UNHCR. This number has doubled in comparison to 10 years ago (1). The number of wars and conflicts in the world has increased again since 2013 (2). Many of the active conflicts are long-standing or resurgent and most conflicts occur in low- or lower-middle-income countries (3, 4). About 86% of those fleeing live in poor countries (1) with very limited health care, and especially limited mental health services.

Due to modern warfare, increasing numbers of those who suffer in conflicts are civilians (3, 5, 6). It has been previously described that most people in conflicts experience at least one traumatic event in the form of extreme violence, terrorist attacks, kidnapping, or torture (7). Flight, displacement, and loss of loved ones tear apart families and communities, which usually serve as important social support networks (8). Furthermore, precarious living conditions after flight due to destroyed infrastructure, lack of access to social services and living in refugee camps (for often long term periods with no perspective) contribute to exacerbating the situation (6, 9–11).

About 50% of severely traumatized people suffer from trauma induced disorders, of which 25% become chronic (12). This can lead to long-term individual suffering and transgenerational trauma (13), as well as negative long-term consequences for society, such as loss of labor force or financial cost (14). The most frequent diagnoses in post-conflict regions are posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 3–88%), Major Depression (MD; 5–80%) and anxiety disorders [1–81%; (15, 16)].

Iraq has a population of about 40 million inhabitants, most of whom are Muslim Arabs. The second largest population group are Kurds. In addition, there is a large number of ethno-religious minorities (17). For decades, the country has been in wars or warlike conditions. In northern Iraq lies the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), which established its de facto autonomy from Iraq in 1991. In 2005, the Baghdad government recognized the autonomy of the region officially in its constitution. About 5 million people live in the KRI.

Iraq has been particularly affected by recurrent war and conflict in recent decades: the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988), the Gulf War (1990–1991) and the Iraq War after the United States invasion (2003–2011). The Iraq Mental Health Survey 2006/7 (18) is the first and only extensive survey of mental illnesses in Iraq. The survey states 12-months-prevalences of 3.99 for any affective disorder, 1.63 for PTSD and 8.58 for any anxiety disorder (including PTSD). More recent research on mental illness in Iraq focuses on specific settings. According to Freh (19) for example, one decade after the US invasion in 2003, prevalences measured in the year 2013 were 55.8% for PTSD and 63.4% for MD among young adults affected by political violence.

In 2014, the so-called “Islamic State” (ISIS), a terror organization, invaded Iraq and captured provinces in the west and north of the country. Seen as “infidels,” religious minorities, particularly the Yazidi people, were treated with extreme brutality. Men were executed, women and children abducted and raped, boys turned into child soldiers (20). This led to massive refugee movements in northern Iraq and Syria.

Due to the extreme brutality, the continuous danger and the long-term displacement of large groups of the population within the country, psychological problems and mental illness are particularly common here. Approximately 79% of Yazidi internally displaced persons (IDPs) in a refugee camp in the KRI reported PTSD symptoms (21). Among Syrian refugees in northern Iraq, a prevalence of 35–38% for PTSD related to trauma and torture was found by Ibrahim and Hassan (7). These numbers coincide with more recent findings about IDPs in Dohuk province by Taha and Sijbrandij (22), who report a rate of 29.1% for PTSD among female IDPs and 31.9% among male IDPs. The rate of common mental disorder cases was 65.1% among female IDPs compared with male IDPs (55.4%). Prevalences are especially high among vulnerable groups that experienced especially severe traumatization: In former child soldiers that had been recruited by ISIS, prevalences of 48.3% for PTSD, 45.5% for MD and 45.8% for anxiety disorders have been previously reported (23). Among Yazidi women who had been victims of the 2014 genocide and had been in captivity of ISIS for months, Kizilhan et al. (24) found prevalences of 97.9% for PTSD and 88.1% for MD.

In addition to the influence of traumatic experiences during conflicts, the local conflict aftermath seems to play a significant role in the development of mental disorders, particularly increasing the risk for MD (9, 25, 26). Refugee and IDP camps in the KRI are slowly becoming a permanent shelter for many people since 2014. As of September 2021, about 1.2 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 248,000 Syrian refugees remain in Iraq, the majority of whom are in the KRI (27). In August 2021, there were still about 183,000 people living in 27 refugee camps in all of Iraq, most of them in the KRI [only two of the 27 camps are in central Iraq; (27)]. There is also a large number of IDPs living in informal settings outside of the camps. For many of them, returning to their homes is not an option because of destruction and ongoing safety concerns.

Life in the refugee camps is characterized by extremely poor living conditions. They do not offer sufficient infrastructure and health services to address the multiple needs, in spite of the activity of numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs) active in the region (28). Mental illness is a common reason for seeking treatment, particularly among adult women in camps (29). While care services are scarce in camps, many affected people seek help outside. However, in addition to the cost for treatment and transportation, the stigma of mental illness is a major barrier (28). Finally, yet importantly, after decades of conflict without an adequate psychosocial care system, a high number of mental illnesses can also be assumed in the host community.

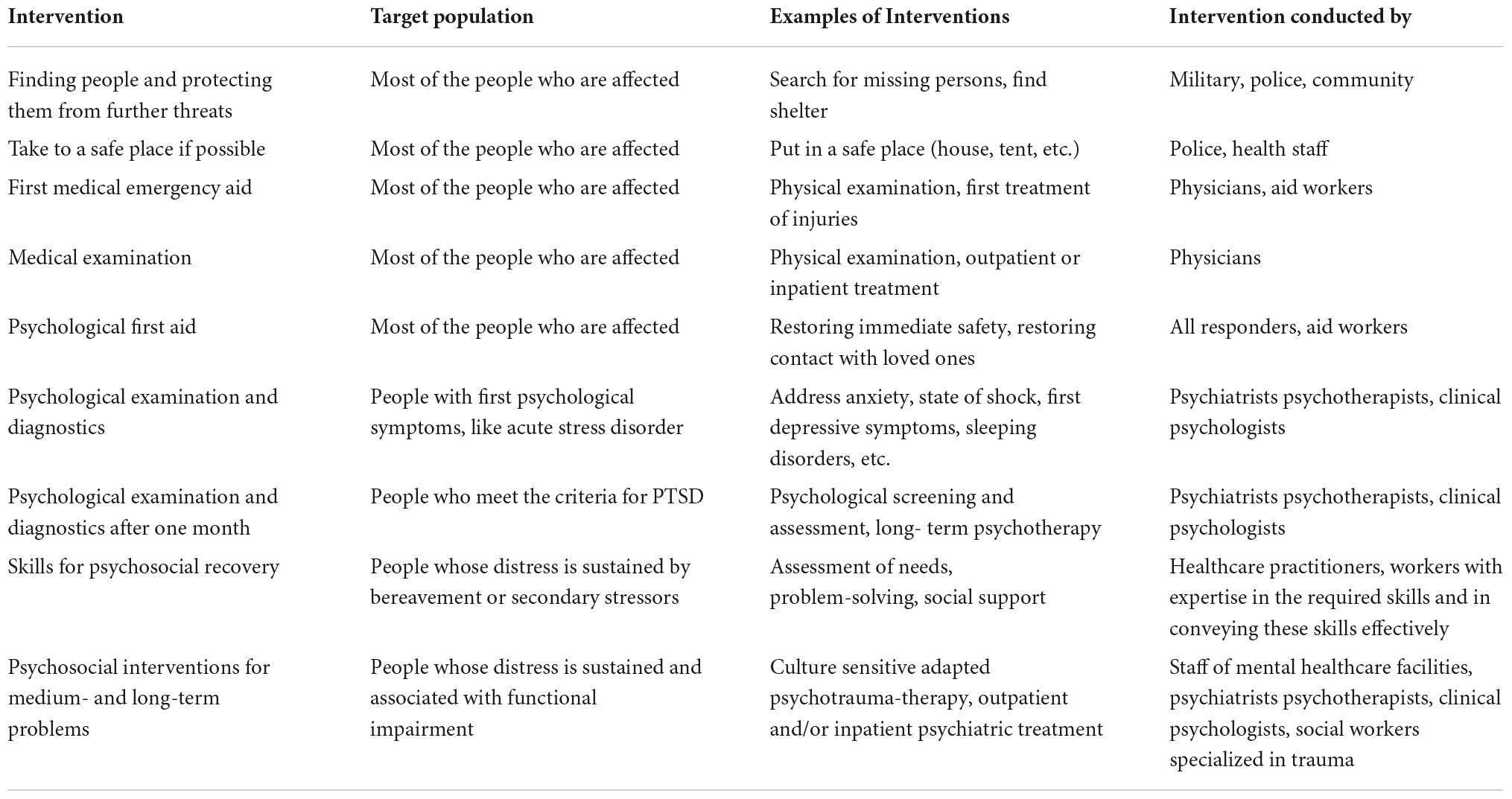

Kizilhan (30) describes the necessary steps of care after disasters like war and conflicts: Before psychosocial interventions are implemented, it is crucial to bring people to safety, care for basic physical needs and provide medical first aid (see Table 1). While this is done, the principles of psychological first aid come into play, which encompass the protection from further harm, care for basic needs, the opportunity to talk about the events and guidance toward helpful coping strategies (31). While these steps are relevant for most of the affected people in a crisis region, only part of them will develop a stress or trauma related mental health problem or aggravation of a preexisting condition. The development of further mental illness depends on several pre-, peri- and post-traumatic risk factors (e.g., the kind of trauma experienced). As described above, because of the severe brutality used by ISIS, the number of people affected by lasting mental illnesses is high in the KRI. For people who develop trauma related sequelae, psychological examination and treatment by trained mental health care experts are necessary.

Table 1. Interventions after disasters [adapted from Kizilhan (30)].

However, 76–85% of people with severe mental disorders in low- and middle- income countries do not receive treatment (14). Almost half of the population worldwide lives in countries where, on average, one psychiatrist serves 200,000 or more people. Other health care personnel trained for treating mental disorders is even rarer (14).

In order to close the gap between high demand and little specialized care, many poor countries apply the concept of task shifting: Mental health care is integrated into primary health care by training general practitioners and other non-specialized health care personnel like nurses or social workers (32). Task shifting falls under the Mental Health and Social Support (MHPSS) approach, which comprises any external or local support provided to protect or improve mental well-being (31). This includes interventions provided by specialized healthcare workers as well as techniques implemented by trained laypersons. International NGOs, which often support the few local care structures, frequently use this principle.

Many of the temporary symptoms and discomforts that occur after a disaster can be addressed through MHPSS approaches. Task-shifting has also been used in Iraq and proves effective in reducing psychological symptomatology (32). However, the development of PTSD or other severe and long-lasting mental disorders cannot be prevented by these approaches (30). The treatment of these disorders should be carried out by specialized personnel such as psychiatrists or psychotherapists, which, as reported, is hardly available in Iraq (see Table 2). According to the Iraq Mental Health Survey 2006/7 (18), in the Kurdistan region there were 17 general psychiatrists, 2 psychiatric practitioners, 4 child and adolescent psychiatrists, 91 psychiatric nurses, 4 psychologist, 15 social workers and 2 psychotherapists at that time. Economical and geographical barriers, such as the lack of public transport and high cost of medication and services, add to the dire situation. This leads to limited de facto access especially for groups most in need.

Table 2. Details on personnel working in mental health (per 100,000 inhabitants) in Iraq and its neighboring countries.

In the KRI more humanitarian assistance is available for refugees and displaced persons due to the relatively stable security situation in comparison to central Iraq (33). However, due to the better security and the familiar environment and language, significantly more displaced people from Syria and all of Iraq also come to the region. The number of severely traumatized, psychologically burdened people is therefore high, and so the demand for psychological aid is immense. This leads to an overload of any of the existing local services already taxed by low capacity before 2014 and by a consistent brain drain of trained experts (34). NGOs located on site are able to address some of the need with the aforementioned MHPSS interventions. However, the high demand often means long working hours and low quality of work for the few professionals. There is a risk that NGOs will employ under-qualified practitioners for the treatment of severe mental diseases such as PTSD (35). Additionally, the difficult working conditions pose a risk for secondary traumatization (36). International NGOs usually stay on site for a limited amount of time: While there were 24 international NGOs in Iraq in 2016 (37), there were only 11 remaining in July 2021 (38).

Due to the development described above, the need for sustainable local services and trained local experts becomes even more pressing, especially considering the risk of long-term suffering and transgenerational transmission of untreated trauma.

The Iraqi health care system does not provide the necessary care. In the aftermath of long-lasting conflicts, economic difficulties and destruction of the necessary infrastructure, the system deteriorated increasingly since the late 1980s (39). In the area of mental health, there is a significant lack of specialized professionals. This is partly because there is no specialization in clinical psychology or psychotherapy, neither in health care training nor at universities or medical schools. No distinction is made between psychotherapists and other health care professions such as social workers or counselors (40). No law exists regulating psychotherapy and “psychotherapist” as a profession is largely unknown.

The situation described prompts the formulation of two objectives for the proposed innovation presented here: First, the improvement of low-barrier psychotherapeutic care. Second, the creation of academic structures that ensure the permanence of the training of professionals in the region and contribute to a sustainable solution.

Aiming to train local specialists in the KRI and create sustainable structures for psychotherapeutic treatment, the “Institute for Psychotherapy and Psychotraumatology” (IPP) was founded in 2016 with the help of the state government of Baden-Wuerttemberg under the coordination of Prof. Dr. J.I. Kizilhan and Prof. Dr. M. Hautzinger. Subsequently, the “Master of Advanced Studies of Psychotherapy and Psychotraumatology” (MASPP) was established.

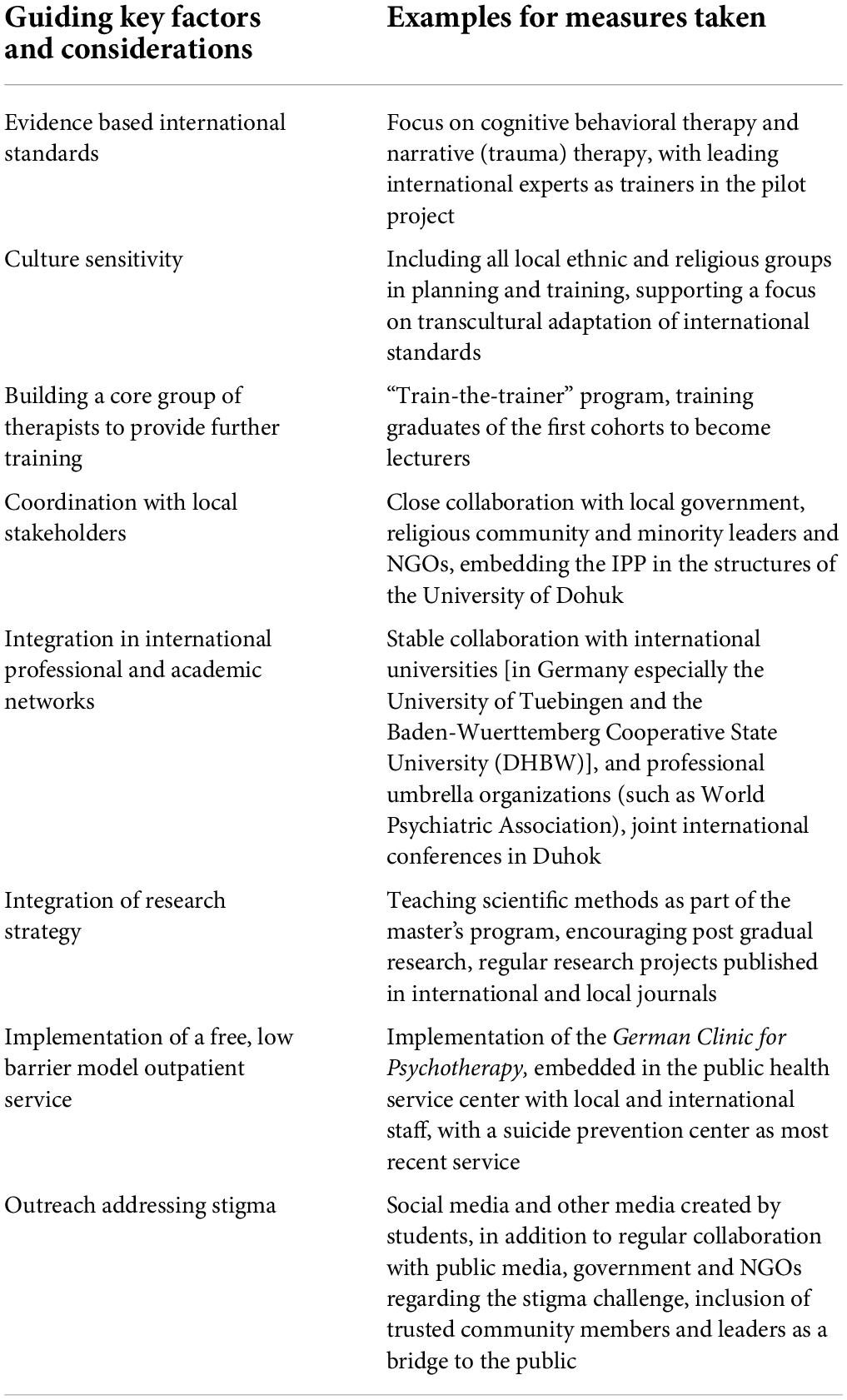

A number of key factors guided the development and implementation of the IPP and MASPP: (a) the training should be grounded in evidence based international standards, (b) training should be culture and trauma sensitive, (c) a core group of local professionals should be trained that can provide training of further local therapists, (d) the project should be coordinated with local leaders, the local government, health care services, and academic institutions, (e) a long term collaboration between the local group and academic institutions with international partners should be built, (f) research should be encouraged to provide more information on needs and project outcomes, (g) a free, low barrier model outpatient service should be implemented, (h) outreach activities should be included to address mental health stigma. Examples of the measures taken to include these considerations are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Considerations and key factors that guided the development of the institute for psychotherapy and psychotraumatology with examples for their implementation.

Since IPPs opening, two cohorts have completed the master’s program successfully, with a third cohort completing the program in 2023. In the meantime, a part of the previous graduates has been further trained through a “train-the-trainer” approach, in order to assume responsibility for teaching and other institute activities in the future and thus ensure sustainability. The IPP and the master’s program are supported and funded by the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of Baden-Wuerttemberg, the German Foreign Ministry and the German Academic Exchange Service. Details on each aspect of the project are presented below:

The IPP aims to research the basic principles and application of psychotherapy and psychotraumatology and to further develop culturally sensitive approaches for use in therapy. Additionally, the institute supports the students of the master’s program to obtain the dual degree of master’s and license to practice as psychotherapists, and to make use of the opportunity to pursue doctoral studies. There is close cooperation of IPP with the University of Dohuk, the Ministry of Higher Education and the Dohuk Health Directorate.

The master’s program teaches the theoretical principles and the practical implementation of psychotherapy and psychotraumatology. Upon graduation, students can work as highly qualified professionals in health care institutions. A prerequisite for participation is the completion of a bachelor’s degree in psychology, social work or education. Applicants have to participate in admission interviews regarding their professional and personal competence. As the main teaching language is English throughout the whole program, participants have to show proof of sufficient language skills.

The curriculum developed for the master’s program is based on the German examination regulations for “psychological psychotherapists” (i.e., licensed psychologists that after successfully completing a diploma or master’s degree in psychology have completed at least 3 years of full-time training) and thus offers all teaching contents of psychotherapist training according to German standards. However, due to the local situation and the high number of traumatized men and women in the KRI, emphasis was placed on teaching techniques for the treatment of trauma sequelae and on teaching transcultural aspects of therapy. The parallel integration of theoretical, practical and self-reflective modules under supervision enables a deep understanding of psychotherapy and therapeutic impact factors.

Contents of the curriculum are: (a) basic knowledge (theories, models) of psychology, psychotherapy and psychotraumatology, (b) assessment, functional analysis of problems, classification and diagnosis of mental illnesses, (c) methods of scientific work and evaluation, (d) clinical skills, treatments and intervention methods, (e) cross-cultural issues of therapy. The fundamentals of all mental disorders and their treatment are taught and applied practically in small groups and role-plays.

The program consists of a preparatory year and a 2-year master’s program, which concludes with a master’s thesis and defense. The detailed sequence of the components over the course of the program is shown in Figure 1. The individual elements are:

1. Theoretical training (600 units of 45 min).

2. Practical experience in psychiatric institutions, refugee camps, clinics (1,800 units of 60 min).

3. Treatment of outpatients with various mental disorders (600 units of 50 min).

4. Clinical supervision (150 units of 50 min).

5. Personal experience, which encompasses reflecting one’s own person and experiencing therapy methods in the client role (120 units of 50 min).

6. Independent knowledge acquisition by means of eLearning modules (120 units of 45 min), homework (370 units of 45 min) and treatment documentation (440 units of 45 min).

Because English is the main teaching language, the preparatory year includes English classes. At the end of the preparation year, students must pass an exam regarding their language skills in order to continue the program.

The teaching is supported by eLearning content on the ‘‘moodle’’ platform.1 Both, the Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State University and the University of Dohuk were already using “moodle” as an eLearning platform beforehand. The content was developed specifically for the project in collaboration between the local and international staff. This ensures continuity of cooperation in the context of international collaboration in phases of limited security, as well as in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic. Access has been provided to international professional online journals and books through the library of the University of Tuebingen.

The first cohort starting in 2017 was taught mainly by international lecturers and experts. To ensure sustainability, a “train-the-trainer” approach was planned from the outset, with some of the graduates of the first cohorts being trained as lecturers and increasingly assuming responsibility for teaching and administrative activities at the institute. The students selected for this purpose take part in additional training courses on study organization and management as well as on didactics. They support the external experts as co-lecturers in order to gain first practical experience in teaching and supervision, before taking over teaching under supervision by an international lecturer. It is planned that the University of Dohuk assumes full responsibility for institute activities and funding in the long term.

The long-term implementation of nationwide psychotherapy can only succeed if the profession of licensed psychotherapist receives recognition and is distinguished from other professions. Therefore, efforts are made to integrate the profession of psychotherapist legally into the Iraqi health care system. There are also efforts to stimulate and strengthen the cooperation between psychiatrists and psychotherapists.

Finally, yet importantly, awareness about traumatizing events and mental illnesses must be raised among the population in order to improve psychotherapeutic care sustainably. In Iraq, as in the entire Middle East, there is great stigma regarding mental illness (28, 35). IPP’s activities therefore include networking with local institutions and NGOs working in the health sector to stimulate public discussion among the population, create acceptance, and lower the threshold for seeking psychotherapy. IPP‘s students and graduates as well as their patients also become multipliers who spread knowledge about psychotherapy in society and contribute to reducing stigma.

In April 2020, 28 of the original 30 students successfully completed the master’s program. Out of the second cohort, which started in October 2018 with 24 students, 21 participants graduated in November 2021. The third cohort of 25 students began the preparatory year in October 2020 and will complete the master’s program in fall 2023. After graduation, most psychotherapists work in high positions in local or international NGOs.

Five students out of the first cohort and two students out of the second cohort were trained as co-lecturers in the “train-the-trainer” program to assist with teaching, supervision, and personal experience. Some of the co-lecturers are pursuing doctoral degrees at the same time.

The 30 students in the first cohort treated 842 patients in 11,563 therapy sessions as part of the practical parts of their master‘s studies between 2017 and 2019. The students of the second cohort treated 891 patients in 12,452 sessions between 2018 and 2021. Hence, in average 13.9 therapy sessions per patient were conducted.

In February 2021, the “German Clinic for Psychotherapy,” an outpatient clinic belonging to the IPP was established. There are currently eight graduates of the IPP working there as psychotherapists, treating people from the refugee camps as well as from the city. The treatment is free of cost for the patients, as high fees constitute a barrier to seeking help beside stigma. A local community member with similar linguistic and ethnic (Yazidi) background from the community has been installed as a first contact to explain services and answer questions about psychotherapy, further reducing fears and stigma.

In addition to teaching and training psychotherapists, IPP successfully organized two international conferences. A conference in 2018 focused on genocide and trauma, and in 2019, a conference focused on the adaptation of Western and Middle Eastern therapeutic methods. Both conferences were well attended, bringing together local and international experts and stakeholders.

In this work, we describe the first establishment of a postgraduate psychotherapy training program in the KRI. The goal of the intervention described was to implement a sustainable solution to the inadequate mental health care in the KRI by having psychotherapeutic care provided by local professionals and integrated into the health care system. We are hoping for this pilot project to serve as best practice example for other post-conflict regions to help set up sustainable psychosocial care in other parts of the world.

The establishment of the IPP and implementation of the master’s program demonstrate that the training of psychotherapists and the integration of psychotherapeutic care into the health care system have started successfully. Many of the lessons learned in the process echo those from WHO’s Building Back Better report (41) which uses 10 countries as examples to demonstrate how crises can act as a catalyst for a positive, sustainable development of health systems. In particular, it shows the importance of successful long-term planning from the outset and of incorporating the central role of government. Close cooperation with the Ministry of Higher Education and the Health Directorate played a central role in facilitating the integration of psychotherapy training into the education system and the inclusion of psychotherapy in the health care system. A next step is to embed the profession of psychotherapist legally, in order to give local professionals the recognition they deserve (including financial recognition) and to make psychotherapy more easily distinguishable from other health professions.

In terms of teaching content, a successful transfer of German psychotherapy training to another culture is shown, with some necessary adjustments to the curriculum. Due to the high number of traumatized people in the KRI, the curriculum focuses on trauma-specific treatment approaches. Those are addressed already very early in the program. However, as required by the German psychotherapy training, students are trained to treat all mental illnesses. This is in contrast to existing MHPSS approaches like the “mental health Gap Action Program” (mhGAP) or the “Problem Management plus” (PM+) by the WHO, which focus on teaching “low intensity psychological interventions” to non-specialized care providers (42, 43). The broad teaching contents, especially the inclusion of clinical supervision and personal experience, in our master’s program make the graduates of IPP capable of diagnosing and treating all kinds of mental illnesses and reflect on their interaction with the patient and the therapy process as a whole. They are able to adapt therapeutic methods to new contexts and understand the possibilities and limits of psychotherapy. This enables them to work in many different contexts and with different target groups and, in the long term, also to treat mental illnesses that are independent of conflict, hence ensuring sustainable mental health care in the region for all kinds of problems.

The curriculum also focuses on addressing cross-cultural differences and teaching culturally sensitive treatment approaches. Religious and cultural beliefs influence the perception and interpretation of psychological symptomatology and therefore must be considered in treatment (44). In particular, potential interreligious conflicts, such as those found in the KRI, should be considered: As a result of the brutality used by ISIS against those of other faiths, patients who are Yazidi, for example, may express mistrust of Muslim therapists (45). Moreover, in traditional, collectivist societies, relationships within the family and the well-being of the entire social fabric play a greater role than individual needs. Therapeutic approaches oriented to Western values, which mainly focus on the individual well-being of the client therefore need to be adapted. Furthermore, cultural differences need to be taken into account regarding the use of didactic methods in the training of students. For example, because of a much more hierarchical instruction style in Iraqi teaching, students are not accustomed to class discussions where they must stand out and apply critical thinking (46). Cultural differences must also be reflected upon with students in the context of culturally sensitive clinical supervision and personal experience sessions (45).

Next to teaching, another goal of IPP is to research culturally sensitive treatment methods and to develop corresponding materials. In addition to the Trauma Workbook (47) which supports students learning about trauma therapy, a culturally sensitive personal experience manual is currently being developed. The cooperation between international lecturers and their corresponding local lecturers that were part of the “train-the-trainer” program has inspired scientific cooperation and common work on transcultural research questions. For all parties involved, the described intervention also contributes to personal growth and cross-cultural understanding and openness.

The success of the IPP is evident in the high acceptance of therapy by patients, the distinctly high demand for graduates of the MASPP as employees from NGOs and other institutions, and the continuing support by the University of Dohuk. In order to stabilize the operation, in addition to a comprehensive ongoing evaluation of the steps taken, the handover of all institute activities to the University of Dohuk, the expansion of the institute’s outpatient clinic and the establishment of an additional outpatient clinic are planned.

Last but not least, the project will hopefully contribute to increasing awareness of mental illness and its consequences and thus increase the acceptance of psychotherapy in the region. At the same time, the project serves as a model that can be emulated and adapted to other world regions affected by violence. The consequences of violent conflicts (PTSD, depression, feelings of anger and revenge, and many more) can make social coexistence difficult and hinder a peace-building process (48). Psychotherapy can help to cope with these feelings in a productive way, thus representing an important contribution to the reduction of war related suffering, which, if it remains untreated, can lead to transgenerational transmission of trauma. Psychotherapy therefore poses an important contribution to peacebuilding.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

JB wrote the main article. TW, MH, and JK read and approved the final manuscript. JK as head of Institute gave detailed information and background about the current situation in Iraq and the Master Program. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global trends – forced displacement in 2020. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2021).

2. Fiedler C, Mroß K, Grävingholt J. “Building peace after war: The knowns and unknowns of external support to post-conflict societies. Bonn: German Development Institute (2016). p. 2021

3. Collier P, Elliott VL, Hegre H, Hoeffler A, Reynal-Querol M, Sambanis N. Breaking the conflict trap : Civil war and development policy. A world bank policy research report. Washington, DC: World Bank and Oxford University Press (2003). doi: 10.1037/e504012013-001

4. Fiedler C, Mroß K. Post-conflict societies: Chances for peace and types of international support. Bonn: German Development Institute (2017).

5. Albertyn R, Bickler SW, van As AB, Millar AJW, Rode H. The effects of war on children in Africa. Pediatr Surg Int. (2003) 19:227–32. doi: 10.1007/s00383-002-0926-9

6. Morina N, Malek M, Nickerson A, Bryant RA. Meta-analysis of interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in adult survivors of mass violence in low- and middle-income countries. Depress Anxiety. (2017) 34:679–91. doi: 10.1002/da.22618

7. Ibrahim H, Hassan CQ. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms resulting from torture and other traumatic events among Syrian Kurdish refugees in Kurdistan region, Iraq. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:241. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00241

8. Murthy RS, Lakshminarayana R. Mental health consequences of war: A brief review of research findings. World Psychiatry. (2006) 5:25.

9. Bogic M, Njoku A, Priebe S. Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. (2015) 15:29. doi: 10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9

10. Kleber RJ. Trauma and public mental health: A focused review. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:451. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00451

11. Magruder KM, McLaughlin KA, Elmore Borbon DL. Trauma is a public health issue. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2017) 8:1375338. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1375338

12. Walter-Denec J, Fellinger-Vols W. Flucht und trauma aus dem blickwinkel der psychiatrie. Psychopraxis Neuropraxis. (2017) 20:165–70. doi: 10.1007/s00739-017-0402-x

13. Flanagan N, Travers A, Vallières F, Hansen M, Halpin R, Sheaf G, et al. Crossing borders: A systematic review identifying potential mechanisms of intergenerational trauma transmission in asylum-seeking and refugee families. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2020) 11:1790283. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1790283

14. World Health Organization. Mental health action plan 2013-2020. Geneva: World Health Organization (2013).

15. Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whiteford H, Saxena S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2019) 394:240–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1

16. Morina N, Akhtar A, Barth J, Schnyder U. Psychiatric disorders in refugees and internally displaced persons after forced displacement: A systematic review. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:433. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00433

17. International Office of Migration IRAQ. Understanding ethno-religious groups in Iraq: Displacement and return. Le Grand-Saconnex: International Office of Migration (2019).

18. World Health Organization. Iraq mental health survey 2006/7. Geneva: World Health Organization (2009).

19. Freh FM. PTSD, depression, and anxiety among young people in Iraq one decade after the American invasion. Traumatology. (2016) 22:56–62. doi: 10.1037/trm0000062

20. Adorjan K, Mulugeta S, Odenwald M, Ndetei DM, Osman AH, Hautzinger M, et al. Psychiatrische versorgung von flüchtlingen in Afrika und dem nahen osten: Herausforderungen und lösungsansätze [Psychiatric care of refugees in Africa and the middle east : Challenges and solutions]. Der Nervenarzt. (2017) 88:974–82. doi: 10.1007/s00115-017-0365-4

21. AlShawi AF, Hassen SM. Traumatic events, post-traumatic stress disorders, and gender among Yazidi population after ISIS invasion: A post conflict study in Kurdistan – Iraq. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2021) 68:656–61. doi: 10.1177/0020764021994145

22. Taha PH, Sijbrandij M. Gender differences in traumatic experiences, PTSD, and relevant symptoms among the Iraqi internally displaced persons. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9779. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189779

23. Kizilhan JI, Noll-Hussong M. Post-traumatic stress disorder among former Islamic State child soldiers in northern Iraq. Br J Psychiatry. (2018) 213:425–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.88

24. Kizilhan JI, Friedl N, Neumann J, Traub L. Potential trauma events and the psychological consequences for Yazidi women after ISIS captivity. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:256. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02671-4

25. Johnson H, Thompson A. The development and maintenance of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in civilian adult survivors of war trauma and torture: A review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2008) 28:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.017

26. Priebe S, Bogic M, Ajdukovic D, Franciskovic T, Galeazzi GM, Kucukalic A, et al. Mental disorders following war in the Balkans: A study in 5 countries. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2010) 67:518–28. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.37

27. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Fact sheet Iraq. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2021).

28. Böge K, Hahn E, Strasser J, Schweininger S, Bajbouj M, Karnouk C. Psychotherapy in the Kurdistan region of Iraq (KRI): Preferences and expectations of the Kurdish host community, internally displaced– and syrian refugee community. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2021) 68:346–53. doi: 10.1177/0020764021995219

29. Cetorelli V, Burnham G, Shabila N. Health needs and care seeking behaviours of Yazidis and other minority groups displaced by ISIS into the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0181028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181028

30. Kizilhan JI. Mental health in crisis regions. In: Chambers JA editor. Field guide to global health & disaster medicine. (Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences) (2021). p. 321–7. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-79412-1.00013-8

31. Inter-Agency Standing Committee. IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings (English). Geneva: Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2007).

32. Al-Khalisi N. The iraqi medical brain drain: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Health Serv. (2013) 43:363–78. doi: 10.2190/HS.43.2.j

33. Grishaber D. Displaced in Iraq: Little aid and few options. (2015). Available online at: https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports/2015/11/02/displaced-in-iraq (accessed January 13, 2022).

34. Al-Khalisi N. The Iraqi medical brain drain: A cross-sectional study. Int J Health Serv. (2013) 43:363–78. doi: 10.2190/HS.43.2.j

35. Enabling Peace in Iraq Center. Iraqs quiet mental health crisis. Washington D. C: Enabling Peace in Iraq Center (2017).

36. Kizilhan JI. Stress on local and international psychotherapists in the crisis region of Iraq. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:110. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02508-0

37. World Health Organization. Iraq: Health cluster emergency response. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

38. World Health Organization. Iraq: Health cluster emergency response. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

39. Al-Bayan Center for Planning and Studies. Restoring the Iraqi healthcare sector: The British national health service as a model. (2018). Available online at: https://www.bayancenter.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/786564532.pdf (accessed October 28, 2021).

40. Halaj A, Huppert JD. Middle east. In: Hofmann SG editor. International perspectives on psychotherapy. (Cham: Springer International Publishing) (2017). p. 219–39. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-56194-3_11

41. World Health Organization. “Building back better. Sustainable mental health care after emergencies. Geneva: World Health Organization (2013).

42. World Health Organization. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: Mental health gap action programme (mhGAP). Version 2.0. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

43. World Health Organization. Problem management plus (PM+). Individual psychological help for adults impaired by distress in communities exposed to adversity. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

44. Kizilhan JI. Religious and cultural aspects of psychotherapy in Muslim patients from tradition-oriented societies. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2014) 26:335–43. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.899203

45. Wolf S, Seiffer B, Hautzinger M, Farhan Othman M, Kizilhan J. Aufbau psychotherapeutischer versorgung in der Region Dohuk, Nordirak. Psychotherapeut. (2019) 64:322–8. doi: 10.1007/s00278-019-0344-2

46. Mohammed-Marzouk MR. Teaching and learning in Iraq: A brief history. Educ Forum. (2012) 76:259–64. doi: 10.1080/00131725.2011.653869

47. Kizilhan JI, Friedl N, Steger F, Rüegg N, Zaugg P, Moser CT, et al. Trauma Workbook for psychotherapy students and practitioners. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers (2019).

48. Bockers E, Stammel N, Knaevelsrud C. Reconciliation in Cambodia: Thirty years after the terror of the Khmer Rouge regime. Torture. (2011) 21:71–83.

Keywords: war, psychological trauma, psychotherapy, treatment, training, teaching, cognitive behavioral therapy

Citation: Beckmann J, Wenzel T, Hautzinger M and Kizilhan JI (2022) Training of psychotherapists in post-conflict regions: A Community case study in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Front. Psychiatry 13:947903. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.947903

Received: 19 May 2022; Accepted: 01 August 2022;

Published: 22 August 2022.

Edited by:

Riyadh K. Lafta, Al-Mustansiriya University, IraqReviewed by:

Maha Younis, University of Baghdad, IraqCopyright © 2022 Beckmann, Wenzel, Hautzinger and Kizilhan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jan Ilhan Kizilhan, amFuLmtpemlsaGFuQGRoYnctdnMuZGU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.