- Psychiatric Clinic, University Hospital for Active Treatment “Prof. D-R Stoian Kirkovic”, Trakia University, Stara Zagora, Bulgaria

Background: Schizophrenia is a severe mental illness in which, despite the growing number of antipsychotics from 30 to 50% of patients remain resistant to treatment. Many resistance factors have been identified. Dissociation as a clinical phenomenon is associated with a loss of integrity between memories and perceptions of reality. Dissociative symptoms have also been found in patients with schizophrenia of varying severity. The established dispersion of the degree of dissociation in patients with schizophrenia gave us reason to look for the connection between the degree of dissociation and resistance to therapy.

Methods: The type of study is correlation analysis. 106 patients with schizophrenia were evaluated. Of these, 45 with resistant schizophrenia and 60 with clinical remission. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scales were used to assess clinical symptoms. The assessment of dissociative symptoms was made with the scale for dissociative experiences (DES). Statistical methods were used to analyze the differences in results between the two groups of patients.

Results: Patients with resistant schizophrenia have a higher level of dissociation than patients in remission. This difference is significant and demonstrative with more than twice the level of dissociation in patients with resistant schizophrenia.

The level of dissociation measured in patients with resistant schizophrenia is as high as the points on the DES in dissociative personality disorder.

Conclusion: Patients with resistant schizophrenia have a much higher level of dissociation than patients in clinical remission. The established difference between the two groups support to assume that resistance to the administered antipsychotics is associated with the presence of high dissociation in the group of resistant patients. These results give us explanation to think about therapeutic options outside the field of antipsychotic drugs as well as to consider different strategies earlier in the diagnostic process.

Background

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness which is characterized by changes in information processing as a consequence of misinterpretation of stimuli from the external environment. As a result, the clinical picture is characterized by positive symptoms (delusions and hallucinations), negative (apathy, anhedonia, dull affect, and loss of social cohesion), and cognitive ones with changes in attention and working memory. In addition to these clinically important symptoms for the diagnosis of schizophrenia, depressive, anxious, and cognitive symptoms are common if not always present (1). These psychiatric manifestations are associated with metabolic, lipid, and immune changes, often requiring additional therapeutic approaches (2, 3). Interesting observations on the level of serum lipids have been made in patients with schizophrenia and in persons using psychostimulants. Decreases in serum lipid levels were observed in both groups (3). Studies assessing self-perception and assessment of interpersonal space have been performed (4). There is evidence that as anxiety increases, interpersonal space increases (5). Such analyzes have also been performed in patients with schizophrenia who show that they have an increase in interpersonal space (6). Impaired cognitive assessment of reality and self-perception is associated with changes in behavior and the appearance of typical symptoms of schizophrenia associated with metabolic disorders as well as changes in neural connections between brain regions (7). This complex picture of changes in perception, behavior, metabolic characteristics, and functional connectivity makes schizophrenia a therapeutic challenge.

This is the reason despite the constant expansion of various therapeutic interventions, a significant percentage of patients remain resistant and pose a serious personal family and social problem. Some authors try to consider patients with resistant schizophrenia as a separate category. This raises the question of looking for different therapeutic approaches in them (2, 8, 9).

Janet presented the concept of dissociation for the first time at the end from 1,800, which is defined as a failure to integrate experiences that are usually related to each other in stream of consciousness (10). Dissociation is the partial or complete loss of normal integration between memories of the past, awareness of one's identity and immediate sensations, and control of bodily movements (11). Dissociation is a special form of consciousness in which events that would normally be related are separated from each other (12). Some authors (13) believe that dissociation is not only pathological, but may also play a role in some adaptive functions. It is also observed in healthy individuals in certain conditions (14).

Historically, dissociation as a clinical phenomenon has been associated with the presence of traumatic events leading to dissociative symptoms (15). A link has been found between dissociative symptoms and traumatic childhood events. Putnam (13) found that the most important traumas originate from childhood due to physical or sexual abuse with subsequent development of symptoms often after many years. According to the same author, dissociative symptoms also often occur in adults with severe traumatic event or a series of traumatic events. He found this in about half of the cases of dissociation. On the other hand, in direct clinical practice with adult patients, it is difficult to make a retrospective assessment of childhood experiences in order to give them the appropriate clinical weight. The authors found that 59.6% of 468 patients with a proven history of childhood sexual abuse were unable to recall episodes of past violence (16). Contradictory data are also available. The problem with the analysis of trauma in early childhood in the evaluation of adult patients is related to the fact that the manifestation of false memory experiences for the presence of trauma is often provoked (17).

It was found a traumagenic neurodevelopmental (TN) model of schizophrenia. Authors find the similarities between the effects of traumatic events on the developing brain and the biological abnormalities found in persons diagnosed with schizophrenia (12). The current diathesis-stress model of schizophrenia proposes that a genetic deficit creates a predisposing vulnerability in the form of oversenstivity to stress (15).

Corresponding changes in interpersonal space and self-esteem have been found in patients with dissociative disorders as well as in patients with schizophrenia (5, 18). Low levels of serum lipids have been reported (19) as well as impaired functional connectivity between brain regions (20).

The connection between dissociation and psychosis has been examined by Eugen Bleuler in patients with schizophrenia (21). In his Textbook of Psychiatry, he writes (21): “It is not only in hysteria that one finds an arrangement of different personalities who inherit from each other. Through such a mechanism, schizophrenia gives rise to different personalities existing side by side [(21), p. 138]. Bleuler has suggested that schizophrenia is a division of mental relationships similar to hysteria, but in a very extreme form. Psychotic decompensation of some individuals with psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations, may occur. There are also a large number of observations showing a high level of dissociation in patients with schizophrenia (15, 22–27). The above data suggest a close link between schizophrenia and dissociative disorders. Several studies have found surprisingly high coincidences in the symptoms of these diagnoses (27–30). Even the symptoms described by Kurt Schneider as pathognomonic for schizophrenia have been proposed to be more characteristic of dissociative disorders (31, 32). Other studies suggest that there are similarities only in hallucinatory production as a characteristic of voices and their expression, but not in the presence of formal thought disorders, bizarre delusions, and negative symptoms (33). Studies indicate that up to 50% of patients with psychosis have severe dissociative symptoms (34, 35). This established overlap of symptoms in schizophrenia and dissociative disorder raises questions about therapy and expectations that a similar pattern of response will be observed. The data show results contrary to expectations. On the one hand, the treatment of schizophrenia is mainly with antipsychotic drugs, and on the other hand, the treatment of dissociative phenomena with antipsychotic drugs is generally ineffective (36). Examining the relationship between schizophrenia and dissociation, some authors raise the question of the existence of a subtype of schizophrenia, allowing for a new conceptualization of the relationship between them (37).

Resistance to drug therapy is registered in about 30–50% of patients with schizophrenia (38–44). The analysis of the relationship between dissociation in patients with schizophrenia and the course of the disease in them shows that those with a high degree of dissociation have a more severe course and more pronounced symptoms (45).

In the analysis of the literature available to us, we did not find a comparative study of the differences in dissociative symptoms in patients with resistant schizophrenia and those in clinical remission.

Working hypothesis: We suppose that the level of dissociation in patients with resistance to therapy will be higher than those in clinical remission.

Materials and Methods

105 patients with schizophrenia were observed. Of these, 45 have resistant schizophrenia and the remaining 60 are in clinical remission.

Including criteria for patients with resistant schizophrenia are those who have met the resistance criteria of the published consensus on resistant schizophrenia (46). They are:

1. Assessment of symptoms with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scale (47, 48).

2. Prospective monitoring for a period of at least 12 weeks.

3. Administration of at least two antipsychotic medication trials at a dose corresponding to or greater than 600 mg chlorpromazine equivalents.

4. Reduction of symptoms when assessed with the PANSS and BPRS scale by less than 20% for the observed period of time.

5. The assessment of social dysfunction using the SOFAS scale is below 60.

The exclusion criteria are:

1. Mental retardation

2. Presence of organic brain damage

3. Concomitant progressive neurological or severe somatic diseases.

4. Expressed personality change

5. Score of MMSI below 25 points.

The Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) was used to assess dissociative symptoms (22).

The statistical software package SPSS, was used for statistical data processing.

Descriptive analyzes, correlation analysis, dispersion analysis, ANOVA, and a non-parametric statistical method were used [Mann Whitney U-test, (49)].

Results

The mean age of patients in the group of resistant schizophrenia was 36.98 years. The minimum age is 21 years and the maximum is 60 years.

The mean age of patients in the group of schizophrenia in clinical remission was 37.25 years. The minimum is 23 years and the maximum is 63 years.

We do not find a difference in the mean age of the patients in the both groups at the time of the study.

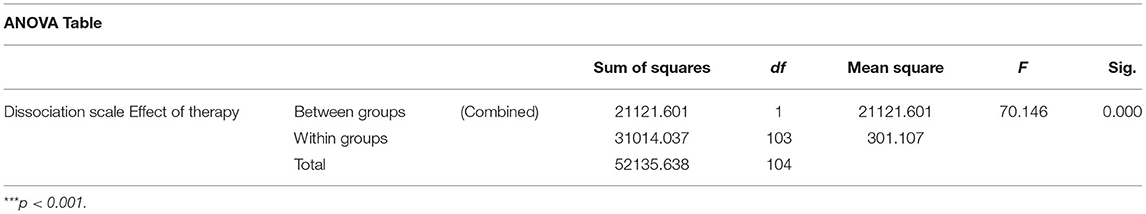

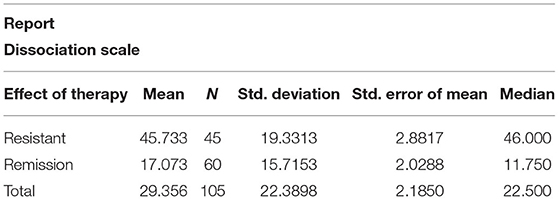

The mean value of the dissociative symptoms scale found in all patients with schizophrenia was 29.1356, standard deviation was 22.3898, and the lowest and highest values were 0 and 97, respectively.

The mean value of the measured points with the Carlson and Putnam scale in patients with resistant schizophrenia is 42.578, and the standard deviation is 20.8977. Their average level of dissociation is commensurate with the level needed to diagnose dissociative personality disorder according to the interpretation of the scale (requires values above 48 on the scale).

For patients in clinical remission, the mean was 15.907 and the standard deviation was 14.530. Their mean level of dissociation is commensurate with the level required to diagnose schizophrenia according to the interpretation of the scale (requires values of 15.4).

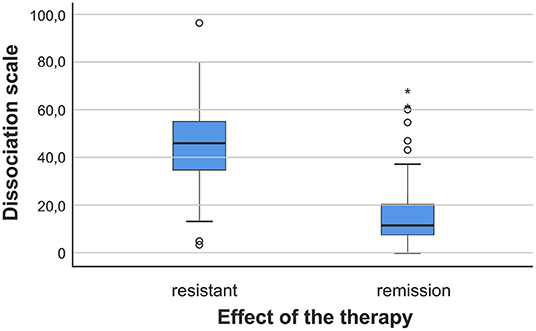

Up to three times the incidence of dissociation values is observed in patients with resistance compared to those in remission. The analysis of the median value in the two groups showed an even greater difference—up to four times higher in the group with patients resistant to therapy (Table 1; Figure 1).

Table 1. Descriptive analysis, the mean values, the median value, the standard deviation, and the standard error in the sample.

Figure 1. The variance of the results measured with DES in both groups of patients. The variance—in blue.

In the analysis of the intragroup distribution of level of dissociation in patients with resistant schizophrenia, it was found that the main grouping of results is in the range of 30–60 on the scale used. This result shows that the majority of patients have a very high level of dissociation.

From the analysis of the distribution of data in patients in clinical remission, we found that the main distribution of patients is grouped in the range from 0 to about 20. We observe a much lower level of dissociation in patients in remission.

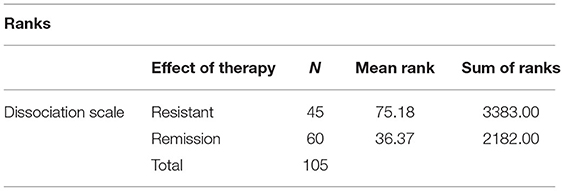

The statistical analysis of the results of Mann-Whitney U test is shown in Table 2 (Ranks) and Table 3 (Statistics) (***p < 0.001).

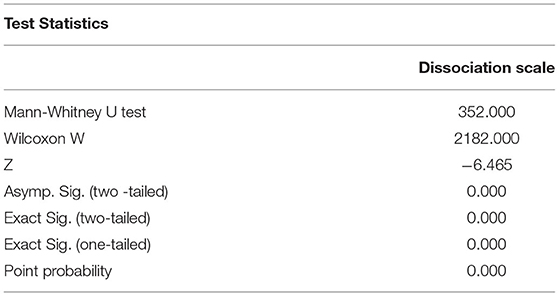

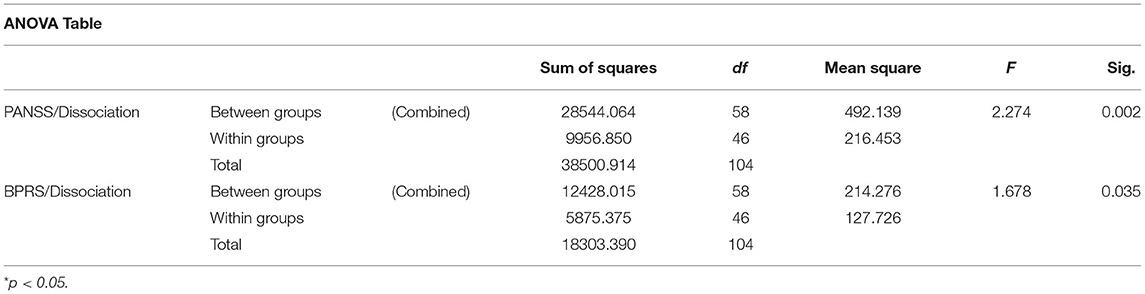

A variance analysis of the relationship between the level of dissociation and resistance to treatment is presented in Table 4.

The difference in the degree of dissociation registered by us in the two groups of patients raised the question: Is there a correlation between the value of dissociation and the values of the PANSS and BPRS scales.

The performed correlation analysis showed the presence of correlation p < 0.05, Table 5.

Conducting a correlation analysis showed that there was a statistically significant correlation between the registered psychotic and dissociative symptoms (Table 6).

Table 6. Dispersion analysis between the dissociation scale (DES) and the clinical scales PANSS and BPRS.

Discussion

Our results show a high degree of dissociation in patients with resistant schizophrenia, which is up to three times higher than in patients in clinical remission. We also find a correlation between the high values of the symptoms measured with the PANSS and BPRS scales and the dissociative symptoms registered with the DES.

Our study of dissociative symptoms coincides with the analysis of other teams, which show the presence of dissociative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia in the range from 11.9 to 44.24 (50–52). Some authors, in addition to assessing the dissociation, also make an analysis in dynamics: in admission and in stabilizing the condition. They do not get much change in the points on the DES from 19.2 to 14.1 (53). We find a mean score on dissociation level in all patients of 29.1356. Our data occupy an intermediate position compared to those described in the literature. Our results confirm the views of pioneers in schizophrenology such as Eugen Bleuler that schizophrenia is a state of extreme degree of dissociation (21).

In the previous studies, patients with resistance and those in clinical remission were not considered separately. The results of the points on the scale for dissociative experiences (DES) in patients in remission observed by us coincide with the criteria of the scale for patients with schizophrenia-−15.4. The results of other studies are mixed. We believe that this is because they have not considered patients separately—resistant and those in remission. Given that schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disease, it is also quite understandable the difference in the values of dissociative symptoms described in the individual studies. Over the years, there have been many analyzes of the overlap of symptoms of dissociative personality disorder and schizophrenia. Numerous studies have shown that up to 50% of patients with schizophrenia meet the diagnostic criteria for dissociative personality disorder (34, 35). These observations, as well as our data, do not show that in fact a probable reason for the lack of efficiency is the high degree of dissociation, which correlates positively with the high scores made with the PANSS and BPRS scales. This high level of resistance that we observe and register challenge of discussing the term resistance to treatment with “antidopaminergic drugs.” Dissociative disorders and symptoms have no effect from antipsychotic treatment (36).

In this sense, the question can be asked whether resistant schizophrenia is a form of dissociative disorder or mixture of the both entities. On the other hand, our results provide a basis for rethinking the diagnostic categories and research criteria used in the context of the relationship between the mind and the brain (54). The question remains whether high dissociation scales are the cause or consequence of the development of the neurodegenerative process in these patients (40, 55). Studies show that in some patients there is a progression of the disease, while in others there is a stationary condition that lasts for years. Magnetic resonance imaging data show that we can distinguish two groups of patients in comparative follow-up. Some have a neurodegenerative process and others do not (56).

The limitation of our study is related to the fact that we make a cross-section of the patient's condition in terms of dissociative symptoms. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine how the symptoms change over time. On the other hand, it is not clear whether the dissociative symptoms did not develop in parallel over time in patients with schizophrenia from the perspective of hospitalizations and in the process of treatment with various antipsychotic drugs. Some authors in a study found in the general population up to 1.7% of people at high risk of developing psychosis (57). No data have been established on the level of dissociative symptoms in them. Our study provides direction to consider assessment of dissociation early in the diagnostic process, especially in patients with the first psychotic episode, in order to discuss prognosis and associated therapy.

Conclusion

We find a high degree of dissociation in patients with resistant schizophrenia. There is a high correlation between psychotic symptoms measured with the PANSS and BPRS scales and dissociative symptoms assessed with the DES. We found that the points on the scale for the level of dissociation in patients with resistant schizophrenia are as high as the requirement of the points on the scale for the assessment of dissociative personality disorder. The data we found for a high scale of dissociation in patients with resistance entitles us to seek therapeutic interventions outside the field of antipsychotic drugs. Therapeutic approaches in dissociative disorders may be considered (symptomatic and psychotherapeutic) as well as consideration of earlier use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethical committee of the University Hospital of Trakia University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Tanaka M, Vécsei L. Editorial of Special Issue “Crosstalk between depression, anxiety, and dementia: comorbidity in behavioral neurology and neuropsychiatry.” Biomedicines. (2021) 9:517. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9050517

2. Tanaka M, Tóth F, Polyák H, Szabó Á, Mándi Y, Vécsei L. Immune influencers in action: metabolites and enzymes of the tryptophan-kynurenine metabolic pathway. Biomedicines. (2021) 9:734. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9070734

3. Correia BSB, Nani JV, Waladares Ricardo R, Stanisic D, Costa TBBC, et al. Effects of psychostimulants and antipsychotics on serum lipids in an animal model for schizophrenia. Biomedicines. (2021) 9:235. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9030235

4. Candini M, Battaglia S, Benassi M, di Pellegrino G, Frassinetti F. The physiological correlates of interpersonal space. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:2611. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82223-2

5. Sambo CF, Iannetti GD. Better safe than sorry? The safety margin surrounding the body is increased by anxiety. J Neurosci. (2013) 33:14225–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0706-13.2013

6. Park SH, Ku J, Kim JJ, Jang HJ, Kim SY, Kim SH, et al. Increased personal space of patients with schizophrenia in a virtual social environment. Psychiatry Res. (2009) 169:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.039

7. Nyatega CO, Qiang L, Adamu MJ, Younis A, Kawuwa HB. Altered dynamic functional connectivity of cuneus in schizophrenia patients: a resting-state fMRI study. Appl Sci. (2021) 11:11392. doi: 10.3390/app112311392

8. Gillespie AL, Samanaite R, Mill J, Egerton A, MacCabe JH, et al. Is treatment-resistant schizophrenia categorically distinct from treatment-responsive schizophrenia? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. (2017) 17:12. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1177-y

9. Weber S, Johnsen E, Kroken RA, Løberg E-M, Kandilarova S, Stoyanov D, et al. Dynamic functional connectivity patterns in schizophrenia and the relationship with hallucinations. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:227. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00227

11. ICD-10. Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Diagnostically Criteria for Research (1993).

12. Li D, Spiegel D. A neural network model of dissociative disorders. Psychiatr Ann. (1992) 22:144–7. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-19920301-11

13. Putnam F. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Personality Disorder. Foundations of Modern Psychiatry (1989).

14. Van der Kloet D, Giesbrecht T, Lynn SJ, Merckelbach H, de Zutter A. Sleep normalization and decrease in dissociative experiences: evaluation in an inpatient sample. J Abnorm Psychol. (2012) 121:140–50. doi: 10.1037/a0024781

15. Read J, Perry BD, Moskowitz A, Connolly J. The contribution of early traumatic events to schizophrenia in some patients: a traumagenic neurodevelopmental model. Psychiatry. (2001) 64:319–45. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.4.319.18602

16. Briere J, Conte JR. Self-reported amnesia for abuse in adults molested as children. J Trauma Stress. (1993) 6:21–31. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490060104

17. Patihis L, Pendergrast MH. Reports of recovered memories of abuse in therapy in a large age-representative U.S. National sample: therapy type and decade comparisons. Clin Psychol Sci. (2019) 7:3–21. doi: 10.1177/2167702618773315

18. Price CJ, Thompson EA. Measuring dimensions of body connection: body awareness and bodily dissociation. J Altern Complement Med. (2007) 13:945–53. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0537

19. Agargun MY, Ozer OA, Kara H, Sekeroglu R, Selvi Y, Eryonucu B. Serum lipid levels in patients with dissociative disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2004) 161:2121–3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2121

20. Krause-Utz A, Frost R, Winter D, Elzinga BM. Dissociation and alterations in brain function and structure: implications for borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2017) 19:6. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0757-y

21. Bleuler E. Textbook of Psychiatry, Transl by Brill AA. London: Allen and Unwin; originally published as Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie. 4th ed. (1924).

22. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. (1986) 174:727–35. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198612000-00004

23. Rosenbaum M. The role of the term schizophrenia in the decline of diagnoses of multiple personality. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1980) 37:1383–5. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780250069008

24. Spitzer C, Haug J, Freyberger J. Dissociative symptoms in schizophrenic patients with positive and negative symptoms. Psychopathology. (1997) 30:67–75. doi: 10.1159/000285031

25. Vogel M, Spitzer C, Barnow S, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ. The role of trauma and PTSD-related symptoms for dissociation and psychopathological distress in inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychopathology. (2006) 39:236–42. doi: 10.1159/000093924

26. Vogel M, Schatz D, Spitzer C, Kuwert P, Moller B, Freyberger HJ, et al. A more proximal impact of dissociation than of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder on schneiderian symptoms in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. (2009) 50:128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.06.007

27. Varese F, Barkus E, Bentall RP. Dissociation mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and hallucination-proneness. Psychol Med. (2012) 42:1025–36. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001826

28. First MB. Mutually exclusive versus co-occurring diagnostic categories: the challenge of diagnostic comorbidity. Psychopathology. (2005) 38:206–10. doi: 10.1159/000086093

29. Kaplan B, Crawford S, Cantell M, Kooistra L, Dewey D. Comorbidity, co-occurrence, continuum: what's in a name? Child Care Health Dev. (2006) 32:723–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00689.x

30. Perona-Garcelán S, Carrascoso-López F, García-Montes JM, et al. Dissociative experiences as mediators between childhood trauma and auditory hallucinations. J Trauma Stress. (2012) 25:323–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.21693

31. Kluft RP. An update on multiple personality disorder. Hosp Commun Psychiatry. (1987) 38:363–73. doi: 10.1176/ps.38.4.363

32. Moskowitz A, Corstens D. Auditory hallucinations: Psychotic symptom or dissociative experience? J Psychol Trauma. (2007) 6:35–63. doi: 10.1300/J513v06n02_04

33. Tschoeke S, Steinert T, Flammer E, Uhlmann C. Similarities and differences in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia with voice hearing. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2014) 202:544–9. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000159

34. Haugen MC, Castillo RJ. Unrecognized dissociation in psychotic outpatients and implications of ethnicity. J Nerv Ment Dis. (1999) 187:751–4. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199912000-00007

35. Ross C, Keyes B. Dissociation and schizophrenia. J Trauma Dissoc. (2004) 5:69–83. doi: 10.1300/J229v05n03_05

36. Ellason JW, Ross CA. Childhood trauma and psychiatric symptoms. Psychol Rep. (1997) 80:447–50. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.2.447

37. Sar V, Taycan O, Bolat N, Ozmen M, Duran A, Oztürk E, et al. Childhood trauma and dissociation in schizophrenia. Psychopathology. (2010) 43:33–40. doi: 10.1159/000255961

38. Davis JM, Schaffer CB, Killian GA, Kinard C, Chan C. Important issues in the drug treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (1980) 6:70–87. doi: 10.1093/schbul/6.1.70

39. Lieberman J, Jody D, Geisler S, Alvir J, Loebel A, Szymanski S, et al. Time course and biologic correlates of treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1993) 50:369–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820170047006

40. Lieberman JA. Pathophysiologic mechanisms in the pathogenesis and clinical course of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. (1999) 60(Suppl 12):9–12.

41. Meltzer HY. Defining treatment refractoriness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (1990) 16:563–5. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.4.563

42. Vita A, Barlati S. Recovery from schizophrenia: is it possible? Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2018) 31:246–55. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000407

43. Potkin SG, Kane JM, Correll CU, Lindenmayer J-P, Agid O, Marder SR, et al. The neurobiology of treatment-resistant schizophrenia: paths to antipsychotic resistance and a roadmap for future research. npj Schizophr. (2020) 6:1. doi: 10.1038/s41537-019-0090-z

44. Correll CU, Howes OD. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: definition, predictors, and therapy options. J Clin Psychiatry. (2021):82:MY20096AH1C. doi: 10.4088/JCP.MY20096AH1C

45. Justo A, Risso A, Moskowitz A, Gonzalez A. Schizophrenia and dissociation: its relation with severity, self-esteem and awareness of illness. Schizophr Res. (2018) 197:170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.029

46. Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Agid O, de Bartolomeis A, van Beveren NJ, Birnbaum ML. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group consensus guidelines on diagnosis and terminology. Am J Psychiatry. (2017) 174:216–29. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050503

47. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. (1962) 10:799–812. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1962.10.3.799

48. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (1987) 13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261

49. Mann HB, Whitney DR. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann Math Stati. (1947) 18:50–60. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177730491

50. Schäfer I, Harfst T, Aderhold V, Briken P, Lehmann M, Moritz S, et al. Childhood trauma and dissociation in female patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: an exploratory study. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2006) 194:135–8. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000198199.57512.84

51. Goff DC, Brotman AW, Kindlon D, Waites M, Amico E. The delusion of possession in chronically psychotic patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. (1991) 179:567–71. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199109000-00009

52. Renard SB, Pijnenborg M, Lysaker PH. Dissociation and social cognition in schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Schizophr Res. (2012) 137:219–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.001

53. Schäfer I, Fisher HL, Aderhold V, Huber B, Hoffmann-Langer L, Golks D, et al. Dissociative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: relationships with childhood trauma and psychotic symptoms. Compr Psychiatry. (2012) 53:364–71. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.05.010

54. Stoyanov D, Telles-Correia D, Cuthbert B. The research domain criteria (RDoC) and the historical roots of psychopathology: a viewpoint. Eur Psychiatry. (2019) 57:58–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.11.007

55. Woods BT. Is schizophrenia a progressive neurodevelopmental disorder? Toward a unitary pathogenetic mechanism. Am J Psychiatry. (1998) 155:1661–70. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1661

56. Gur RE, Cowell P, Turetsky BI, Gallacher F, Cannon T, Bilker W, et al. A follow-up magnetic resonance imaging study of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1998) 55:145–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.145

Keywords: resistance, schizophrenia, dissociation, resistant schizophrenia, treatment, diagnosis, antipsychotic drugs

Citation: Panov G (2022) Dissociative Model in Patients With Resistant Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 13:845493. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.845493

Received: 29 December 2021; Accepted: 21 January 2022;

Published: 15 February 2022.

Edited by:

Drozdstoy Stoyanov Stoyanov, Plovdiv Medical University, BulgariaReviewed by:

Masaru Tanaka, University of Szeged, HungaryPetar Petrov, Medical University of Varna, Bulgaria

Copyright © 2022 Panov. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Georgi Panov, Z3Bhbm92QGRpci5iZw==

Georgi Panov

Georgi Panov