94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry, 15 March 2022

Sec. Schizophrenia

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.836896

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Link between Nutrition and SchizophreniaView all 5 articles

Background: Obesity is a common health problem among patients with schizophrenia, but the precise mechanisms are not fully understood. There has been much interest in the relationship between gut microbiome and development of obesity. Gender-dependent microbial alteration has been reported in previous studies. However, the gender factor in gut microbiome composition of schizophrenia patients has been less investigated. Our study aimed to identify differences in gut microbiota between schizophrenia patients with normal weight and central obesity and investigate the gender specific features.

Method: Twenty participants (10 males, 10 females) with central obesity (CO) and 20 participants (10 males, 10 females) with normal weight (NW) were recruited from two rehabilitation wards in a psychiatric hospital in central Taiwan. Fecal samples from 40 participants were processed for microbiota analysis. The intestinal microbiota composition was analyzed using next-generation sequencing and QIIME software.

Results: Significantly higher richness of gut microbiota at the class level (measured by the number of observed OTUs) was observed in female NW subjects than in female CO subjects (P = 0.033). Furthermore, female NW subjects showed higher alpha diversity at both phylum and class levels (measured by the Shannon, Simpson, and Inverse-Simpson indexes) compared with female CO subjects. Males showed no significant difference in alpha diversity between groups. Taxonomic analysis showed that female CO subjects had significantly lower abundance of Verrucomicrobia (P = 0.004) at the phylum level, reduced abundance of Akkermansia (P = 0.003) and elevated level of Prevotella (P = 0.038) and Roseburia (P = 0.005) at the genus level.

Conclusions: The present results evidenced altered microbiome composition in schizophrenia patients with central obesity and further suggested the role of the gender factor in the process of gut dysbiosis.

Schizophrenia is a severe psychiatric disorder associated with a wide range of symptoms including hallucinations, delusions, negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunctions (1). Morbidity and mortality are higher in individuals with schizophrenia than in the general population. Obesity and obesity-related conditions are common health problems in patients with schizophrenia (2). Higher incidences of cardiovascular diseases related to obesity and metabolic dysfunction account for premature deaths of schizophrenia patients (3), resulting in an average of 14.5 years of potential life lost compared with the normal population (4). The development of obesity and metabolic problem in schizophrenia patients was associated with multiple factors including less physical activity (5), smoking and poor diet (6). Moreover, antipsychotic medications were reported to contribute to the high prevalence of obesity in those with schizophrenia (2). In addition to physical and medical factors, gender difference was reported to be associated with antipsychotic-related metabolic dysfunction. McEvoy et al. found higher prevalence of metabolic dysfunction among females than males receiving antipsychotics (7). The gender-dependent discrepancies may be partly attributable to gender differences in pharmacokinetics (8). However, the mechanism behind gender effects on metabolic dysfunction in schizophrenia patients remained unclear.

Studies have investigated the relationship between gut microbiota and obesity. The ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes was higher in obese mice than in lean mice (9). In obese human subjects, similar microbiota patterns were also observed (10). Evidence has also accumulated supporting a role for gut microbiota in metabolic diseases. Larsen et al. found significant differences in composition of microbiota between adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-diabetic adults. The proportions of phylum Firmicutes and class Clostridia were reduced in the diabetic compared with the non-diabetic group (11). Le Chatelier et al. reported that individuals with low bacterial richness were characterized by more marked overall adiposity (12).

Although antipsychotic-related metabolic dysfunction has aroused clinical concern, the relationship between antipsychotic-related obesity and gut microbiota has been investigated in only a few clinical studies. Bahr et al. compared between 18 male adolescents chronically taking Risperidone and antipsychotic-naïve same-sex controls and found decreased Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio and significant BMI gain in subjects on long-term treatment with Risperidone (13). Using a cross-sectional study design, Flowers et al. investigated the microbial communities and alpha diversity in 117 adults [49 atypical antipsychotic (AAP)-treated, 68 non-AAP-treated] with bipolar disorder. Decreased Simpson diversity was found in AAP-treated females compared with non-AAP-treated females. Furthermore, Akkermansia was significantly decreased in non-obese patients treated with AAPs (14). Yuan et al. followed up 41 first-episode schizophrenia patients for 24 weeks to assess the influence of Risperidone treatment on metabolic parameters relative to microbiota composition. They observed positive correlation between changes in fecal Bifidobacterium spp. and changes in weight over 24 weeks of Risperidone therapy (15). Flowers et al. investigated gut microbiota of 37 adults diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and treated with an AAP or mood stabilizer. AAP-treated females exhibited reduced gut microbial diversity compared with non-AAP-treated females (16).

Clinical research to date illustrated changes in gut microbiota in patients treated with AAP toward that of an obesogenic profile (13–15). Moreover, gender-dependent microbial alteration has been observed in several studies (13, 14, 16). Nevertheless, most of these studies were performed in an outpatient setting and dietary differences in the study group may be a concern. As mentioned in previous studies, diet has significant effects on gut microbiota diversity (17). This study aimed to investigate the differences in gut microbiota composition between schizophrenia patients with normal body weight and central obesity in an inpatient setting with less variance in patients' diet intake. We hypothesized that gut microbiota composition would differ between schizophrenia patients with normal weight and central obesity.

Forty schizophrenia patients, including 20 patients with central obesity and 20 patients with normal weight were recruited from the inpatient units of the Tsaotun Psychiatric Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Nantou, Taiwan. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Tsaotun Psychiatric Center (IRB No. 106035). All patients provided written informed consent after complete description of the study by research assistants. Patients were enrolled into this study if they (1) were aged from 20 to 65 years, (2) fulfilled the diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (18), and (3) remained symptomatic but without clinically significant fluctuation and their antipsychotic doses had not been changed for at least 3 months prior to this study. Subjects with waist circumstance ≥ 90 cm for men and ≥ 80 cm for women are classified as central obese (CO) while those with body mass index (BMI) of 18.5–24 and waist circumstance <90 cm for men and <80 cm for women are classified as normal weight (NW). Exclusion criteria included DSM-5 diagnosis of intellectual disability, dementia, substance/alcohol abuse or dependence, uncontrolled gastrointestinal disorders, antimicrobial exposure or probiotics use within 3 months, presence of medical conditions that would significantly affect weight changes and inability to follow protocol.

Sociodemographic features (i.e., gender, age) and antipsychotic medications were ascertained through clinical interview and review of medical records. Daily dosages of antipsychotic medication were converted to chlorpromazine equivalent (19). Clinical assessments were conducted using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (20). The ratings were performed by a research psychiatrist experienced with rating scales. Waist circumference was measured with a measuring tape. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP) in resting state were recorded. BMI, waist hip ratio (WHR), percentage of body fat (PBF) were determined using the non-invasive body composition analyzer (InBody 230, Seoul, Korea). Biochemical parameters levels in serum including glucose, glycated hemoglobin, total cholesterol (TG), high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL), and triglyceride were also measured.

All participants provided a stool sample that was immediately frozen after collection at hospital and delivered in ice bags within 24 h via commercial transport to the laboratory (Feng Chi Biotechnology, Taipei, Taiwan). DNA was extracted from fecal samples using a QIAamp PowerFecal DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The isolated DNA aliquot was stored at −80 °C until sequencing.

The hypervariable V3-V4 regions of bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified for library construction. Sequencing of the amplicon DNA samples was performed at Feng Chi Biotechnology (Taipei, Taiwan) using the Illumina Miseq platform. Taxonomic classification of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at the phylum to genus levels were conducted according to Greengenes database using QIIME1 software.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared using Student's t-tests for the continuous variables and chi-square tests for the discrete variables. The alpha-diversity, observed OTUs, Shannon index, Simpson index and inverse Simpson's Diversity, estimate of two groups were compared using independent t-tests. The beta-diversity comparison was performed using the principle coordinates analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis distances. The between-groups inertia percentage was examined using the Monte-Carlo test. The Wilcoxon test was performed to identify the significance of taxonomy between the two groups.

General characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1. As can be seen, there was no significance in age, chlorpromazine equivalent and PANSS total score between the CO and NW groups. As expected, CO subjects have larger BMI (P < 0.001) and waist circumstance (P < 0.001) as well as higher WHR, PBF, SBP, HDL-C, and TG. Gender differences in clinical characteristics of subjects were also observed. Male CO subjects have significantly higher WHR (P < 0.001), SBP (P < 0.05) and DBP (P < 0.01) than male NW subjects. However, the differences in WHR, SBP and DBP between female CO and NW subjects were not significant.

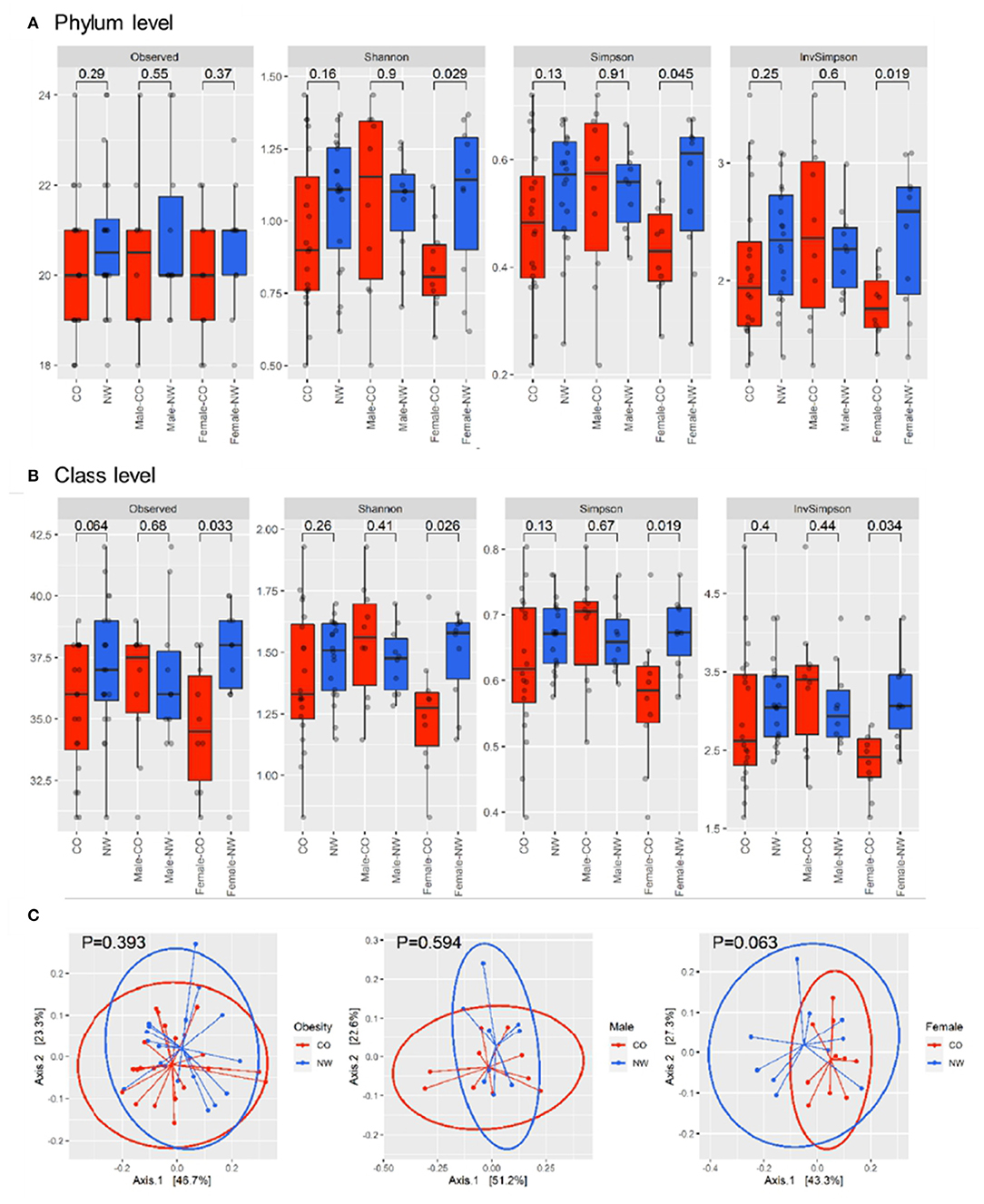

Comparison between the CO and NW groups showed no significant difference in alpha diversity, number of observed OTUs, Shannon index, Simpson index, and inverse-Simpson index at both phylum (Figure 1A) and class levels (Figure 1B). The analysis of beta diversity calculated using PCoA of Bray-Curtis distances revealed no distinction in composition of gut microbiota between CO and NW subjects (Figure 1C). As for gender-based differences of gut microbiota, female NW subjects had significantly higher richness of gut microbiota at the class level (P = 0.033) (measured by the number of observed OTUs) and higher alpha diversity at both phylum and class levels (measured by the Shannon, Simpson, and Inverse-Simpson indexes) compared with female CO subjects (Figures 1A,B). As for beta diversity, the two groups showed distinct gut microbiota composition at the phylum level (P = 0.063) (Figure 1C). In contrast, there was no difference in measures of alpha diversity and beta diversity between male CO and NW subjects.

Figure 1. Alpha and beta diversity were compared between subjects with central obesity (CO) and normal weight (NW). Bacterial community richness was defined by the observed number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and alpha diversity was calculated using the Shannon index, Simpson index, and inverse Simpson index for both phylum (A) and class levels (B). The analysis of beta diversity was calculated using PCoA of Bray-Curtis distances (C).

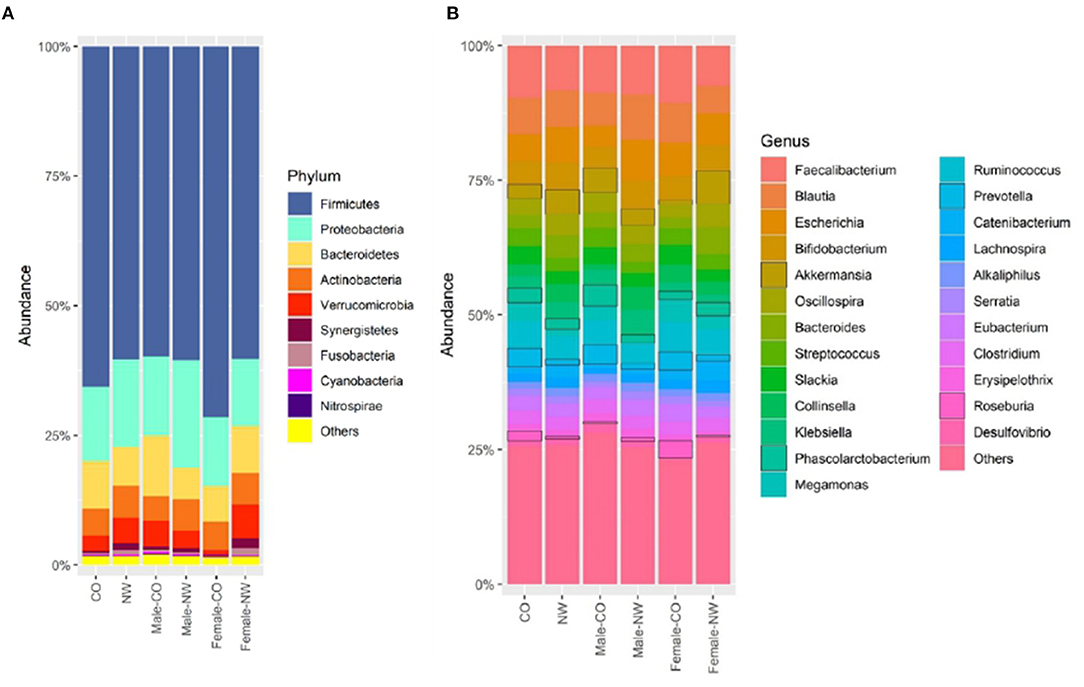

Taxonomic analysis was performed to assess the composition of gut microbiota at different levels in samples of CO and NW subjects. This study found less Bacteroidetes than Firmicutes in the schizophrenia subjects (Figure 2A). Figure 2B shows the relative abundance of gut microbiota in CO and NW subjects at the genus level. At the phylum level, CO subjects showed significantly decreased abundance of Verrucomicrobia compared with NW subjects (P = 0.034) (Figure 3A). At the genus level, CO subjects of both genders showed significantly decreased abundance of Akkermansia (P = 0.022) (Figure 3B) and increased abundance of Prevotella (P = 0.032) (Figure 3C) compared with their NW counterparts.

Figure 2. Relative abundance of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of the gut microbiota of central obese (CO) and normal weight (NW) subjects at (A) phylum and (B) genus levels.

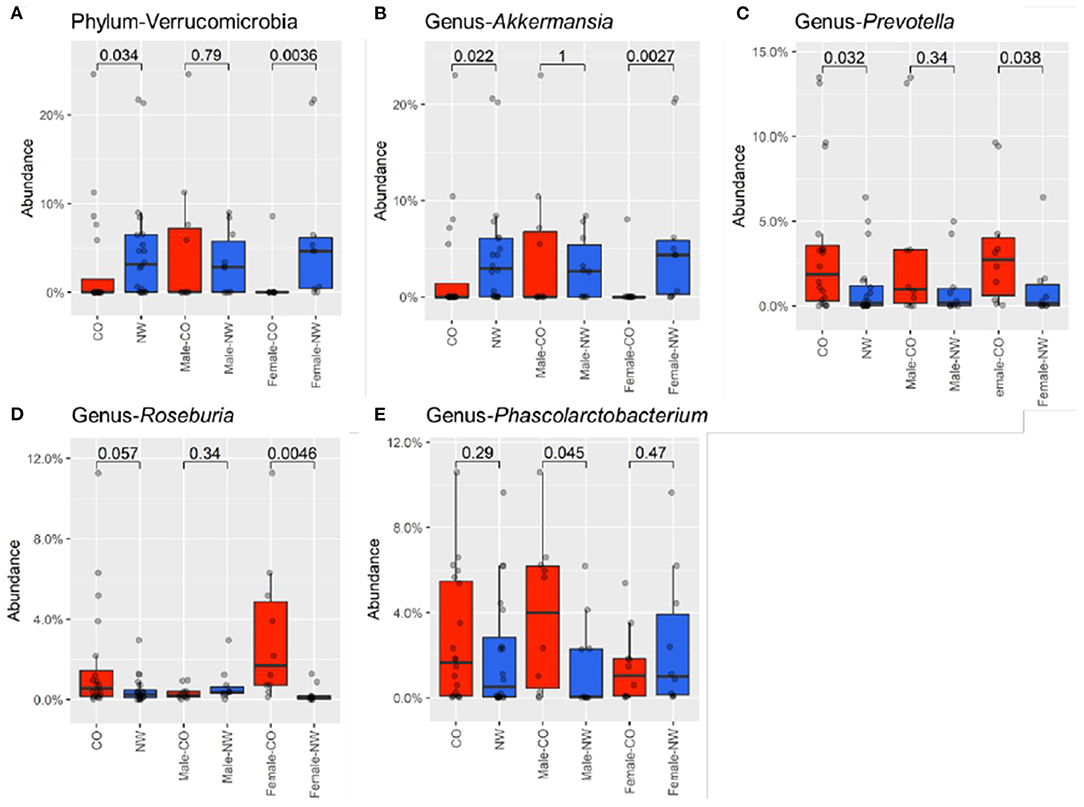

Figure 3. Relative abundances were compared between male and female subjects with central obesity (CO) and normal weight (NW). The relative abundance of Verrucomicrobia at phylum (A), genus of (B) Akkermansia, (C) Prevotella, (D) Roseburia, and (E) Phascolarctobacterium were compared. Female CO subjects had significantly lower abundance of Verrucomicrobia at the phylum level. At the genus level, relative abundance of Akkermansia was decreased in female CO subjects compared with female NW subjects, while Prevotella and Roseburia were increased in female CO subjects. Phascolarctobacterium was enriched in male CO subjects compared with male NW subjects.

Differences in taxonomic profile was observed mainly among female subjects. Female CO subjects had significantly lower abundance of Verrucomicrobia (P = 0.004) (Figure 3A) at the phylum level. At the genus level, three differentially abundant genera were observed. Relative abundance of Akkermansia was reduced in CO subjects compared with NW subjects (P = 0.003) (Figure 3B), while Prevotella (P = 0.038) (Figure 3C) and Roseburia (P = 0.005) (Figure 3D) were elevated in CO subjects.

Comparison among male subjects showed no significant difference in taxonomic profile at the phylum level. Only the Phascolarctobacterium genus was found to be enriched in male CO subjects compared with male NW subjects (P = 0.045) (Figure 3E).

This study aimed to investigate the differences in microbiota composition between schizophrenia patients with normal body weight and central obesity. We found lower bacterial richness and alpha diversity in female CO subjects than in female NW subjects. In a rat model, olanzapine was found to induce significant body weight gain and to reduce gut microbial diversity in female rats only (21). Bahr et al. observed an increase in body weight and microbiota diversity in male adolescents treated with Risperidone (13). Flowers et al. found that treatment using second-generation antipsychotics (SGA) was associated with weight gain and reduction in microbial species richness in females (14, 16). The present findings also suggest the role of the gender factor in antipsychotic-related gut dysbiosis.

The findings of bacterial taxonomic composition were diverse across studies. In this study, only female subjects had different bacterial taxonomic composition. Flowers et al. found significantly reduced Akkermansia in non-obese female bipolar patients treated with AAPs (14). However, the current results showed decreased Akkermansia in CO subjects compared with NW subjects. Akkermansia is a genus in the phylum Verrucomicrobia containing a single known species, namely Akkermansia muciniphilia which was found in the human gut (22). A. muciniphilia is an intestinal mucin degrader and was found to regulate metabolic functions and considered a promising next-generation probiotic (23, 24). Decreased abundance of Akkermansia in CO subjects was notable in this study. Moreover, Prevotella and Roseburia in female CO subjects and Phascolartobacterium in male CO subjects were more abundant compared with NW subjects. Bahr et al. found less abundant Prevotella in chronic Risperidone-treated adolescents with significant BMI gain than those without BMI gain (13). Li et al. noted lower relative abundance of Roseburia in schizophrenia patients than in normal control subjects (25). Shen et al. observed increased relative abundance of Phascolarctobacterium in schizophrenia subjects (26). Further investigations are necessary to elucidate the role of the above-mentioned taxa in schizophrenia patients with central obesity.

The lack of significant difference in bacteria diversity between the CO and NW groups may partly be attributed to their relatively minor BMI difference. Some studies reported sex hormone as a factor determining gut microbiota composition. Reduced abundance of Akkermansia was reported to be correlated with higher levels of follicule-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH level was reported to be positively correlated with abundance of Roseburia and Prevotella (27). Another study reported that post-menopausal women had lower relative abundance of Prevotella than pre-menopausal women (28). Different abundance of the abovementioned three genera were observed in this study. Although the levels of sex hormones were not analyzed, considering the subjects' age (mean, 51.4 years), the alteration of gut microbiota, especially in female subjects, might be associated with hormonal change. Future investigations should further assess the relationship of sex hormone with gut microbiome in schizophrenia patients.

This study has several limitations. The sample size was small; hence, the findings can only be considered preliminary and cannot be further extrapolated. The cross-sectional design hinders drawing valid conclusions on the role of gut microbiota in CO schizophrenic subjects. Although CO subjects in this study had significantly higher BMI than NW subjects (26.4 vs. 20.0, P < 0.001), the average BMI of CO subjects was 26.4, which was overweight in terms of BMI classification. We did not recruit normal control subjects in current study. In future work, it may be prudent to include microbiota composition of normal control subjects to better outline the microbiota changes in schizophrenia patients.

Despite the limitations mentioned above, this study investigated differences in gut microbiota composition of schizophrenia patients that are relatively homogeneous in their dietary variance. Some gender-related differences in gut microbiota were observed. Future longitudinal and large-scale studies are required to further elucidate the interplay between metabolic problems and microbiota in schizophrenia patients. The current results highlight the importance of considering gender as a variable factor when examining interactions among microbiota, central obesity and metabolic dysfunction in this population.

The study results evidenced altered microbiome composition in schizophrenia patients with central obesity and further suggested the role of the gender factor in the process of gut dysbiosis.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accession ID: PRJNA790710.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Tsaotun Psychiatric Center (IRB No. 106035). All patients provided written informed consent after complete description of the study.

Y-LT and Y-WL conceived and designed the study, and wrote the manuscript. C-YL and T-HL coordinated the progress of the study, and revised the manuscript. P-NW assisted for participants' referral and recruitment. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The study was funded by Tsaotun Psychiatric Center, MOHW (Grant number: 110004) and Hospital and Social Welfare Organizations Administration Commission, MOHW (Grant number: 10744). The funders were not involved in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors are grateful to the participants for their participation in this study. We thank Hsin-Hsien Lin for the contribution during sample collection.

1. Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB. Schizophrenia. Lancet. (2016) 388:86–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6

2. Allison DB, Newcomer JW, Dunn AL, Blumenthal JA, Fabricatore AN, Daumit GL, et al. Obesity among those with mental disorders: a National Institute of Mental Health meeting report. Am J Prev Med. (2009) 36:341–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.020

3. Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Vestergaard M. Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2012) 25:83–8. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835035ca

4. Hjorthøj C, Stürup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft M. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2017) 4:295–301. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0

5. Beebe LH, Tian L, Morris N, Goodwin A, Allen SS, Kuldau J. Effects of exercise on mental and physical health parameters of persons with schizophrenia. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2005) 26:661–76. doi: 10.1080/01612840590959551

6. Brown S, Birtwistle J, Roe L, Thompson C. The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. (1999) 29:697–701. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798008186

7. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, Nasrallah HA, Davis SM, Sullivan L, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. (2005) 80:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.014

8. Aichhorn W, Gasser M, Weiss EM, Adlassnig C, Marksteiner J. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics and side effects of second generation antipsychotic drugs. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2005) 3:73–85. doi: 10.2174/1570159052773440

9. Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. (2006) 444:1027–31. doi: 10.1038/nature05414

10. Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. (2006) 444:1022–3. doi: 10.1038/4441022a

11. Larsen N, Vogensen FK, van den Berg FW, Nielsen DS, Andreasen AS, Pedersen BK, et al. Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS ONE. (2010) 5:e9085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009085

12. Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, Prifti E, Hildebrand F, Falony G, et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature. (2013) 500:541–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12506

13. Bahr SM, Tyler BC, Wooldridge N, Butcher BD, Burns TL, Teesch LM, et al. Use of the second-generation antipsychotic, risperidone, and secondary weight gain are associated with an altered gut microbiota in children. Transl Psychiatry. (2015) 5:e652. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.135

14. Flowers SA, Evans SJ, Ward KM, McInnis MG, Ellingrod VL. Interaction between atypical antipsychotics and the gut microbiome in a bipolar disease cohort. Pharmacotherapy. (2017) 37:261–7. doi: 10.1002/phar.1890

15. Yuan X, Zhang P, Wang Y, Liu Y, Li X, Kumar BU, et al. Changes in metabolism and microbiota after 24-week risperidone treatment in drug naïve, normal weight patients with first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2018) 201:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.017

16. Flowers SA, Baxter NT, Ward KM, Kraal AZ, McInnis MG, Schmidt TM, et al. Effects of atypical antipsychotic treatment and resistant starch supplementation on gut microbiome composition in a cohort of patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Pharmacotherapy. (2019) 39:161–70. doi: 10.1002/phar.2214

17. Senghor B, Sokhna C, Ruimy R, Lagier J-C. Gut microbiota diversity according to dietary habits and geographical provenance. Hum Microbiome J. (2018) 7–8:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humic.2018.01.001

18. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing (2013).

19. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O'Donnell H, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Focus. (2014) 12:235–43. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.12.2.235

20. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (1987) 13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261

21. Davey KJ, O'Mahony SM, Schellekens H, O'Sullivan O, Bienenstock J, Cotter PD, et al. Gender-dependent consequences of chronic olanzapine in the rat: effects on body weight, inflammatory, metabolic and microbiota parameters. Psychopharmacology. (2012) 221:155–69. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2555-2

22. Derrien M, van Passel MW, van de Bovenkamp JH, Schipper RG, de Vos WM, Dekker J. Mucin-bacterial interactions in the human oral cavity and digestive tract. Gut Microbes. (2010) 1:254–68. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.4.12778

23. Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2013) 110:9066–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219451110

24. Zhang T, Li Q, Cheng L, Buch H, Zhang F. Akkermansia muciniphila is a promising probiotic. Microb Biotechnol. (2019) 12:1109–25. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13410

25. Li S, Song J, Ke P, Kong L, Lei B, Zhou J, et al. The gut microbiome is associated with brain structure and function in schizophrenia. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:9743. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89166-8

26. Shen Y, Xu J, Li Z, Huang Y, Yuan Y, Wang J, et al. Analysis of gut microbiota diversity and auxiliary diagnosis as a biomarker in patients with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. Schizophr Res. (2018) 197:470–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.01.002

27. He Y, Wang Q, Li X, Wang G, Zhao J, Zhang H, et al. Lactic acid bacteria alleviate polycystic ovarian syndrome by regulating sex hormone related gut microbiota. Food Funct. (2020) 11:5192–204. doi: 10.1039/C9FO02554E

Keywords: schizophrenia, microbiome, central obesity, gender difference, gut dysbiosis

Citation: Tsai Y-L, Liu Y-W, Wang P-N, Lin C-Y and Lan T-H (2022) Gender Differences in Gut Microbiome Composition Between Schizophrenia Patients With Normal Body Weight and Central Obesity. Front. Psychiatry 13:836896. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.836896

Received: 16 December 2021; Accepted: 15 February 2022;

Published: 15 March 2022.

Edited by:

Shaohua Hu, Zhejiang University, ChinaReviewed by:

Almagul Kushugulova, Nazarbayev University, KazakhstanCopyright © 2022 Tsai, Liu, Wang, Lin and Lan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chun-Yuan Lin, bGluanl1YW5AZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.