- Olga Tennison Autism Research Centre, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Background: Receiving a child's autism diagnosis can be stressful; as such, parent resolution contributes to the wellbeing and development of healthy parent-child relationships. In other significant childhood diagnoses (e.g., cerebral palsy, diabetes), the degree to which parents adjust to (a) their child's diagnosis and (b) their changes in expectations concerning their child's development and capacity (referred to as resolution to diagnosis), has been associated with improved outcomes including facilitating parent-child relationships and improved parental wellbeing. Given potential benefits to parent and child, and the heterogenous nature of autism, examining the unique factors associated with resolution to diagnosis is important. In this systematic review we identified factors that support or inhibit parental resolution to their child receiving a diagnosis of autism.

Methods: We completed a systematic review following PRISMA guidelines of peer-reviewed studies from 2017 to 2022, that investigated parental resolution or acceptance of an autism diagnosis. Papers including “acceptance” needed to encompass both accepting the diagnosis and the implications regarding the child's abilities. We searched six databases (Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, ProQuest), with additional papers located following review of reference lists.

Results: Fourteen papers with 592 participants that investigated parental resolution or acceptance of an autism diagnosis, were included. We identified six common factors that facilitate or inhibit parental resolution and acceptance of an autism diagnosis including: symptom severity; religion, belief, and culture; knowledge and uncertainty; negative emotions (i.e., denial, shame, guilt); positive emotions; and support. Greater resolution was associated with improved “attunement and insightfulness” in the parent-child relationship.

Limitation: The review was limited by the small number of studies meeting inclusion criteria. Second, the quality of included studies was mixed, with over half of the studies being qualitative and only one randomized control trial (RCT) identified.

Conclusion: Parental resolution can have an impact on parent's perception of their child's capabilities and impact the parent-child relationship. We identified six categories that aid in inhibiting or promoting resolution to diagnosis. Despite taking a broad approach on the definition of resolution, the low number of studies identified in the review indicates a need for more research in this area.

Systematic review registration: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, PROSPERO [ID: CRD42022336283].

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD; henceforth “autism”) is a neurodevelopmental condition, typically emerging in late infancy or early childhood (1). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM−5) (2) diagnostic criteria for autism includes persistent differences in two domains: (a) social communication and interaction skills and (b) restricted repetitive patterns of behavior, interest, or activities. Given the potential for a diagnosis of autism to change one's expectations for their child, the process associated with a child's diagnosis can be particularly stressful for parents (3). Furthermore, there is potential for the nature of the parent-child relationship to change following the diagnosis, for example, by altering the parent's perception of their child's developmental and functional capacity, which may lead to additional impacts on child and parental wellbeing (4). However, this process of acceptance in which parents come to terms with and manage their new reality, referred to as “resolution of diagnosis”, has been associated with greater parental wellbeing (5, 6).

Resolution, a construct derived from attachment theory (7–10), involves understanding the child's diagnosis and the implications of the diagnosis on parents' internal representation of their child, from pre-diagnosis to post-diagnosis (10). Resolution requires parents to adjust their internal representations and expectations to the new reality of having a child who has been diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental disability (5) and adjusting their parental approach to match this reality. Internal representation refers to the expectations, feelings, and acknowledgment regarding the child's personality and behaviors (4). Important in this process is for parents to realistically understand and accept the challenges associated with a child's diagnosis to better facilitate the parent-child relationship and their support, and thus the wellbeing of both (11). Similar concepts of adjusting and acceptance of a diagnosis can be found in other theoretical approaches, such as Psychological Adjustment (12) and Expectation Management Theory of Acceptance (13), which also includes the process of accepting the implications of the child's diagnosis and has similar positive benefits on the parent child relationship (13, 14).

Benefits of resolution to parents of children with significant childhood diagnoses includes a greater capacity of parents to cope with stress, resulting in reduced psychological distress and depression, higher levels of marital satisfaction, and seeking and accessing social support (9, 14). For example, mothers of autistic children who are more emotionally resolved reported higher levels of cognitive and supportive engagement during play interactions with their child, provided greater verbal and non-verbal scaffolding skills (15), skills critical for the development of attention and play (16). However, the process of resolution is not a simple process, with unresolved parents often reporting denial or disbelief and searching for alternate explanations, for example, seeking a second opinion regarding their child's autism diagnosis (17). Factors including severity of diagnosis, parental nationality and age, knowledge, and negative emotions (e.g., guilt, grief, shame) have been found to negatively inhibit the process of resolution (3, 18, 19).

Several recent reviews have examined resolution or similar acceptance-based processes within the context of significant child diagnoses. Sher-Censor and Shahar-Lahav's (6) recent scoping review identified studies using the Reaction to Diagnosis Index (RDI) to examine parent's response to their child's diagnosis of a disability (inclusive of autism). They identified 13 studies involving parents of autistic children. Overall, authors found a lack of resolution for parents of children with a disability was common (44% of participants from 47 studies). They also found associations between lack of resolution and higher parenting stress, poor parental mental health, and insecure attachment with their child.

While not focused explicitly on resolution, Makino et al.'s (20) scoping review identified benefits associated with a similar process of acceptance in which acceptance included coming to terms with the new family circumstances and future needs of their child. Parents identified several benefits of receiving their child's autism diagnosis and raising an autistic child, included becoming more patient and less judgemental. Similarly, Brown et al.'s (21) narrative review of father's experiences revealed an ongoing period of adjustment to their child's autism diagnosis, leading to acceptance of the child and gratefulness for the knowledge and experiences gained. This period of adjustment was framed positively as leading to a stronger parental bond with their child. However, negative initial emotions or factors that might inhibit the process of acceptance (e.g., denial, confusion, shame, disbelief), were not discussed in these reviews. Given the complex and heterogenous nature of autism, and the variability in recommendations to support autistic children, it is unsurprising that their child receiving a diagnosis of autism can be stressful to parents (22). In what is often an already stressful period, parents of autistic children report higher levels of parental stress than neurotypical children, and any other disability group (23). Therefore, given benefits of resolution to their child's diagnosis, developing an understanding of factors that may inhibit or support this process may lead to the development of strategies to enable parents to achieve resolution, bringing broad benefits to this population, improving the parent-child relationship, and reducing parental stress.

1.1. Current review

The process of resolution allows both parents and children to reach an optimal level of wellbeing (18). The aim of this systematic review was to identify studies from the last 5 years (2017–2022) that identified factors associated with parental resolution of their child's diagnosis of autism. These factors may impact resolution or be impacted by resolution. Resolution was defined as a parent's process of coming to terms with and accepting their child's significant childhood diagnosis (10). To ensure greater depth and understanding of the parental experience, we expanded this definition to include empirical research that specifically investigated “resolution of diagnosis” as well as empirical research that described a process of parental diagnosis separate to this term.

2. Methods

Prior to conducting the current review, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) was checked for similar reviews, no such reviews were identified. This review was registered with PROSPERO in May 2022 (ID: CRD42022336283). The review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (24).

2.1. Selection criteria and search strategy

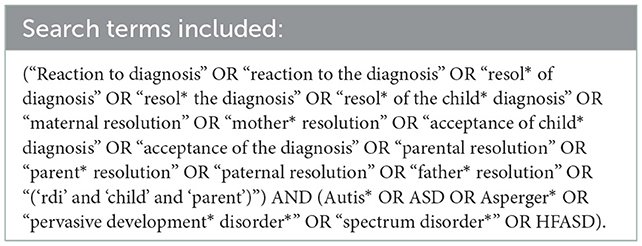

A systematic search began in May 2022 utilizing six databases: Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and ProQuest. Publication limit of January 2017 onwards to current period (May 2022) was applied. Our search terms (Table 1) reflected definitions of parental resolution or acceptance of child diagnosis, and terms for Autism (Table 1) with combinations of truncated terms searched across all fields (title, abstract, keywords).

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in the review, they were (a) published in English, (b) published in peer-reviewed journals or were reviewed dissertations, (c) were empirical studies, and (d) focused on aspects of resolution to diagnosis or acceptance. We required that the population was parents of children with an autism diagnosis, including pre-DSM-5 diagnoses; autism, Asperger's disorder or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), with or without an intellectual disability.

3. Results

3.1. Literature retrieval and results

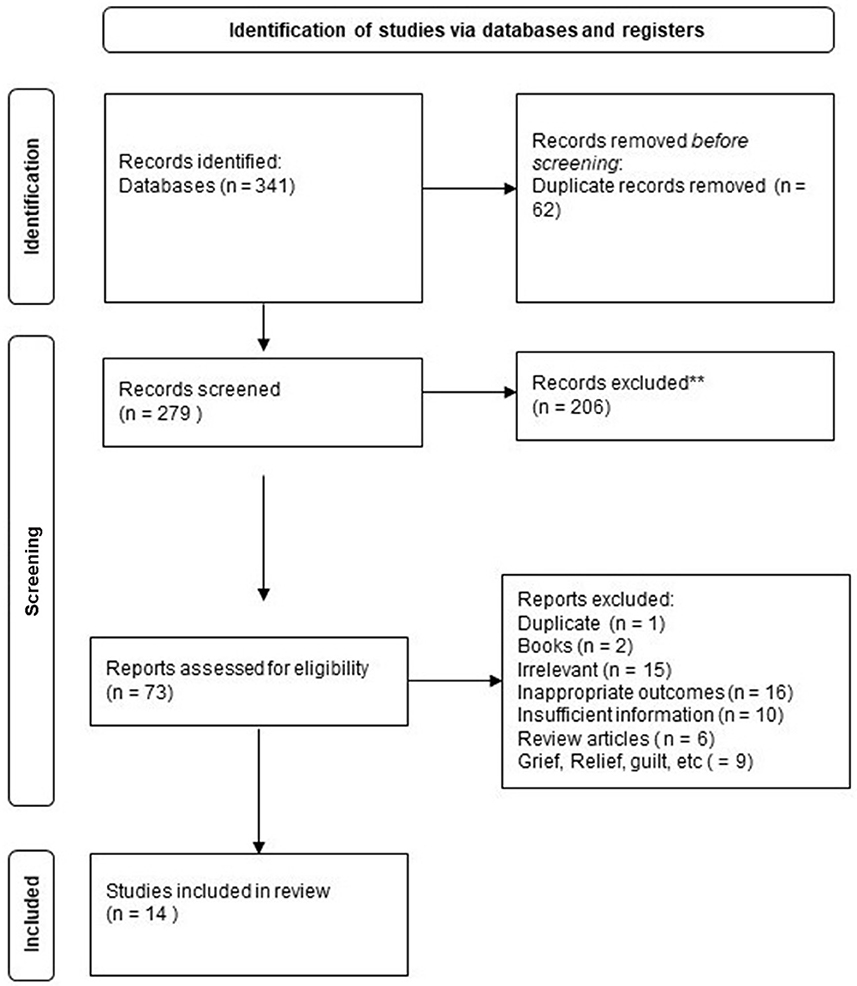

Figure 1 details a comprehensive flow chart of study selection. A total of 341 articles were identified across all six databases. Articles were exported into EndNote X9 (25) for the removal of duplicates, and then imported into Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/) for screening. After title and abstract screening of the remaining 279 papers, 73 studies were included in a full text review. Of these, 59 were excluded for being non-empirical studies, clearly irrelevant, reviews or papers that did not report or measure aspects of resolution or acceptance of a diagnosis or factors associated with acceptance. Three dissertations were identified and included in the review. In total, fourteen papers were relevant and met the research aims and were included in the review.

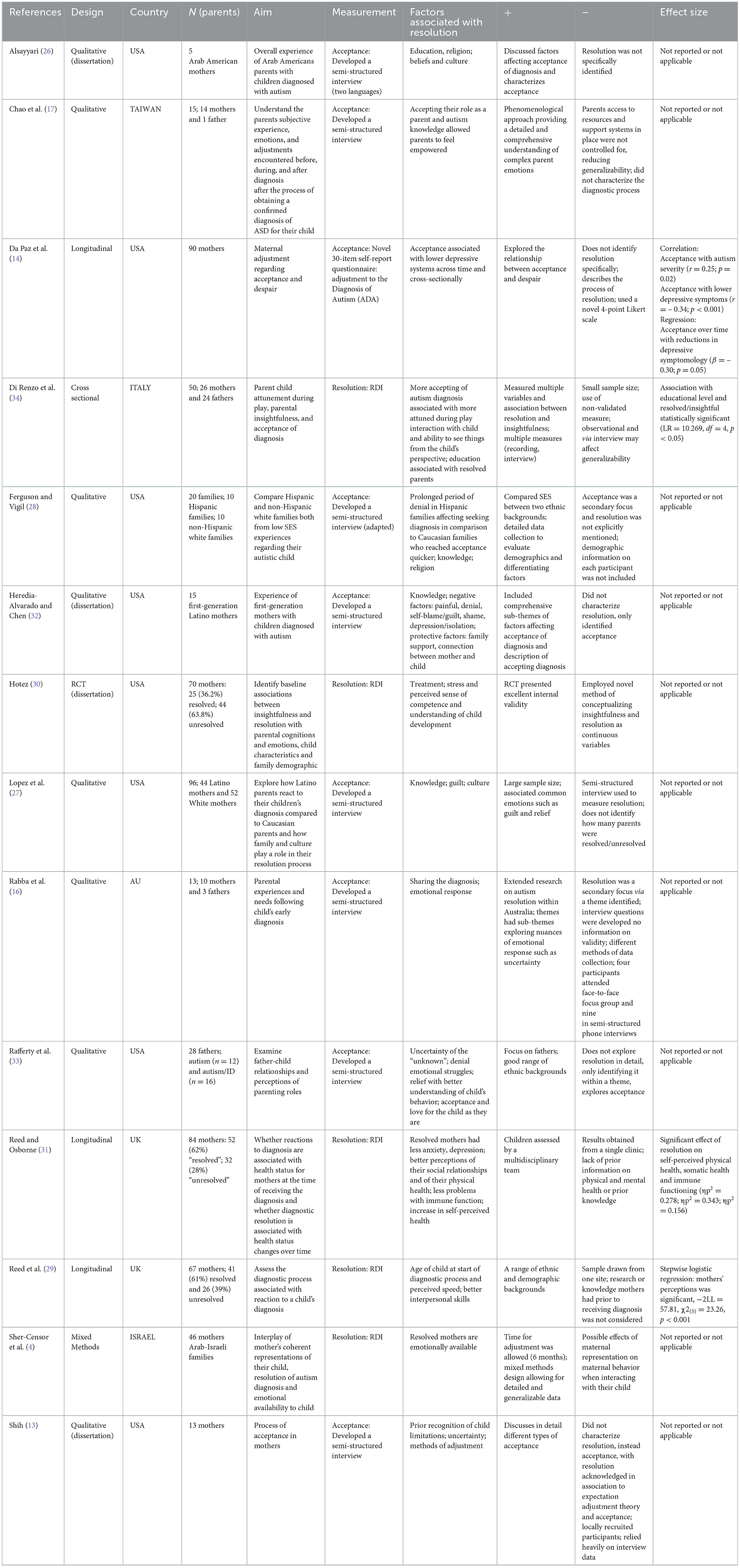

3.2. Sample characteristics

Fourteen studies met the study aims and were included in the final review. The characteristics of these studies are presented in Table 3. Studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 8), United Kingdom (n = 2), Australia (n = 1), Taiwan (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), and Israel (n = 1). A total of 592 participants (mothers = 536, fathers = 56) with 20 families, in which the study did not mention how many individuals from each family participated in the study. Two Studies focused on Latino participants from America (total n = 59), both of these studies compare Latino families with Caucasian families. Of nine studies identifying child gender, 82% of the children diagnosed were males and most studies focused on mothers as participants (n = 9), fathers (n = 1), both parents (n = 3), and families (n = 1).

3.3. Resolution or acceptance measurement

Measurement varied across studies either measuring resolution, acceptance, or psychological adjustment. A range of different study types were included (RCT, n = 1; Longitudinal, n = 2; Cross-sectional, n = 1; Mixed methods, n = 1; Qualitative Studies, n = 8; Refer to Table 3); 57% of included studies were of a qualitative nature.

For theoretical perspectives, five papers adhered closely to a theoretical definition of resolution, using Marvin and Pianta's (10) model and using the RDI to measure resolution.

Nine studies measured acceptance or a form of acceptance closely resembling resolution. Eight of these studies used semi-structured interviews, with acceptance emerging as a theme amongst experiences of parents, sub-categorizing the process of accepting a diagnosis. One study used the Adjustment Scale (14) to measure acceptance of diagnosis.

Only two qualitative studies clearly indicated resolution (resolved; 61.5%). Other studies placed resolution and acceptance on a continuum.

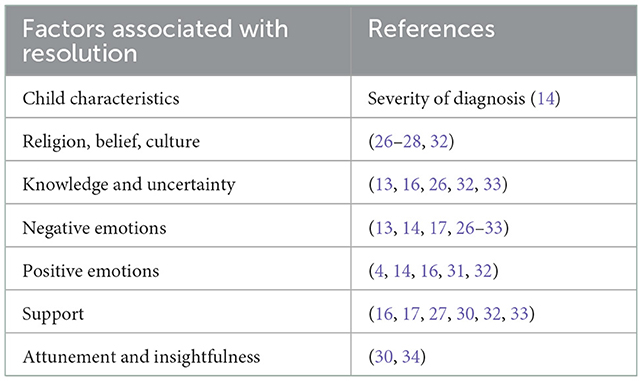

3.4. Factors associated with resolution

3.4.1. Child characteristics

De Paz et al. (14) found characteristics of the child, specifically autism severity, had a substantial effect on acceptance or resolution, in which severity was positively associated with acceptance, suggesting that greater condition severity was associated with greater parental acceptance in relation to maternal adjustment to the diagnosis.

3.4.2. Religion, belief, culture

Four studies found that religion, beliefs, and culture impacted acceptance or resolution. All four studies found religion to be a positive coping mechanism positively affecting resolution. Three studies included Arab and Latino participants (see Table 3), where culture and associated stigma within cultures was viewed as an inhibitory factor to resolution; across studies, lack of awareness within the community was a common theme associated with belief and culture.

3.4.3. Knowledge and uncertainty

Lack of knowledge and uncertainty was found to be a factor affecting parent resolution in six studies. This factor included specific knowledge about autism symptomology, treatment processes and the overall process of supporting a child with an autism diagnosis. Uncertainty or “the unknown,” was found to stall the process, including uncertainty regarding the future and doubts regarding the final diagnosis (13). Alsayyari (26) found that diagnosis allowed some parents to feel empowered, as they finally understood their child's developmental delays. In Lopez et al. (27) the degree of autism knowledge differed by culture. Although both Latino and Caucasian groups were underinformed, Latino families expressed greater lack of knowledge about autism (27). Finally, parental self-education about autism was found to be a protective factor (13, 16).

3.4.4. Negative emotions

Negative emotions including feelings of grief, denial, shame, and blame emerged as a common theme for 71% of included studies. Negative emotions occurred during initial stages of receiving the diagnosis for most parents but were maintained for parents who had not yet adjusted their internal representations of their child. The more resolved a parent was, the less feelings of guilt, shame, denial, and blame occurred. Ferguson and Vigil (28) found a prolonged period of denial elongated the diagnostic-process in Hispanic families compared to Caucasian families. Further, Reed et al. (29) found mothers who reported a poorer experience of the diagnostic process, tended to be “resolved” in their reaction to the diagnosis. Resolution and acceptance demonstrated lower levels of perceived stress and were associated with lower depressive symptoms (14, 30). Resolved mothers were seen to be emotionally available, reporting less anxiety, depression, better perceptions of their social relationships, and overall increased self-perceived mental and physical health over time, compared to unresolved mothers (4, 31). Contrastingly, Reed and Osborne (31) did not find depression or anxiety to be significantly associated with mothers classified as “unresolved”.

3.4.5. Positive emotions

Positive emotions (e.g., relief) were identified as factors to reaching adjustment faster (14). The adjustment period described was that of redefining goals and expectations of the child and adjusting parent's perceptions of their relationship with their child. Positive experiences and emotional responses were associated with greater acceptance (16). Social support and perceived sense of competence was positively correlated with resolution (30). Furthermore, searching for alternate diagnosis stopped once parents reached a level of acceptance, referring to readjusted expectations of their child's capacity and state of being (17, 32).

3.4.6. Support factor

Heredia-Alvarado and Chen (32) identified positive factors including family support and connection between mother and child, aided the acceptance process. Parents reported a sense of relief upon realizing they were not alone in the community and could access support, decreasing self-blame (17). Hotez (30) found higher levels of resolution and perceived social support were associated with each other. Lopez et al. (27) found support influenced parent involvement in treatment, with Caucasian families tending to feel more supported through services and extended family, while support from children's grandparents was relatively equal. Rabba et al. (16) found increased knowledge surrounding autism was associated with higher support levels. Rafferty et al. (33) found that with the help of family and therapy, a parent was able to gradually progress in their process of accepting their child's diagnosis and the potential effects of this diagnosis on their child's life.

3.4.7. Attunement and insightfulness

Attunement and insightfulness refer to parent's ability to understand the motives behind their child's behavior and emotional experiences in a child-focused and positive manner, resulting in an appropriate response to the child's needs (30, 34). Di Renzo et al. (34) found that more accepting parents were more attuned to their child during play interaction and were better able to see things from the child's perspectives, in comparison to non-resolved parents, with 30% of resolved/insightful parents being attuned to their child's needs. Furthermore, a Randomized Control Trial (RCT) by Hotez (30) testing a playtime intervention with parents and children which examined attachment, parental perception, and parent insightfulness, found that the highest proportion of mothers (38.2%) were unresolved and non-insightful. However, this RCT was the only one identified in our search that met the inclusion criteria.

For further categorization of studies and descriptive data, please see Table 2.

4. Discussion

Previous research suggests that resolution and acceptance of a child's diagnosis has positive effects on parent-child relationships and wellbeing (6). Given the increased stress and mental health challenges often reported by parents of autistic children (i.e., compared to parents of children with other significant childhood diagnoses), the present systematic review examined parental resolution of their child's diagnosis of autism, specifically factors that may support or present barriers to resolution, and potential benefits brought by resolution to diagnosis.

Six factors emerged across the fourteen studies, five of which impacted resolution and one which was determined to be an outcome of resolution. Factors included child characteristics (severity of autism), religion, belief and culture, knowledge and uncertainty, negative emotions (including denial, shame, guilt), positive emotions and factors (such as family support and emotional availability), and attunement and insightfulness.

An interesting finding was that severity of diagnosis was associated with greater resolution. As severity of diagnosis likely comes with greater challenges, this finding seems somewhat counterintuitive. In the broader literature, the impact of severity of diagnoses on resolution is mixed, with findings supporting a negative association or no association at all (6). For parents of autistic children in one study (14), severity seemed to aid in the resolution process suggesting that severity may be associated with greater acceptance because there is less opportunity for hope that the diagnosis is false, or denial of the condition, thereby facilitating the acceptance process. Although it is important to note that only one study (14) found severity as an associated child characteristic of acceptance in the current review, this finding is consistent with Sher-Censor et al. (6) who found less severe symptoms were associated with resolution.

The role of negative and positive emotions has consistently been shown to be associated with resolution in other childhood diagnoses (6). An interesting finding from our study was the relationship between culture and beliefs and emotions. Negative emotions were found to be associated with culture and ethnic background such that Latina and Hispanic mothers were more likely to experience an increased sense of guilt once receiving the diagnosis, whereas Caucasian families reported a sense of relief and were more likely to have a briefer adjustment period (27, 32). This complex interplay between emotion and culture may not only impact the initial reaction to the diagnosis, but also length of diagnostic resolution process and ultimately parental resolution. Thus, understanding culture and its potential impact on resolution is important for professionals supporting parents during the diagnostic process.

Uncertainty and lack of knowledge of autism was associated with negative emotions and was a common theme inhibiting resolution and acceptance. This association may be explained by Chao et al. (17) who coined the phrase “anxious searching”, whereby parents sought a second opinion when they did not accept the initial diagnosis. Alternatively, Ferguson and Vigil (28) suggested factors including parents' negative attitudes toward autistic people, and lack of awareness about autism by family and friends, might lead to apprehensiveness, worry, embarrassment, and being generally upset by their child's diagnosis.

These adverse feelings are not surprising, given that broader disability literature indicates that the diagnostic process represents a challenging and confusing period for parents. With regards to autism, parents have reported that medical professionals often vary in their knowledge and experience with autism (35, 36), or predominately focus on negative factors or limitations associated with the diagnosis (22). Framing the diagnosis as overly negative or not discussing strengths or solutions, has been shown to negatively impact the parents' experience of the diagnostic process as well as their understanding of autism (37, 38). As resolution requires developing a realistic appraisal of the child's prognisis and potential challenges, ensuring that parents have information surrounding the diagnosis is an important step toward resolution.

Another interesting finding was the interplay between time and the experience of negative emotions. Across most studies, negative emotions were more prominent amongst parents when they initially received their child's diagnosis. This finding is consistent with research involving diagnoses of other disabilities (33) and highlights that resolution is a process. Moreover, while negative emotions may be present at the beginning of the process, with greater support and knowledge about autism, including adopting a strength-based approach, these negative emotions can decrease (28), thereby facilitating acceptance of the child's diagnosis.

Despite the studies in this review similarly describing the process of acceptance, across the studies, they were often labeled differently. Thus, there were inconsistencies across the studies in terms of the interpretation of the process of resolution. For example, Da Paz et al. (14) understood acceptance to be dichotomous, creating different stages of acceptance, while Lazarus et al. (12) understood it to be a more sensitive and complex continuous scale. Similarly, Chao et al. (17) defined “acceptance” as referring to the timepoint of receiving the diagnosis, while the “process of resolution” was described as an adjustment period whereby parents adjust their goals and expectations for their child. Comparatively Shih (13) included Expectation Management Theory of Acceptance whereby expectational adjustment, the process prior to acceptance, paralleled the construct of resolution. Thus, the present review highlights the role different theoretical positions or perspectives have on understanding the construct of resolution.

4.1. Quality of studies

The present review identified only one randomized control trial (RCT), while 57% of studies were of a qualitative nature. Although, qualitative studies can lead to greater insight of the topic matter (26), qualitative studies are required to explore relationships between factors and determine causal mechanisms. Furthermore, relationships between factors reported as significant were often of small effect size (9, 14), with few reporting larger effect sizes between factors (30) (please see Table 3 for a summary of the strengths and weaknesses of each study included in the review).

4.2. Limitations and future directions

Some papers referred to resolution as an adjustment period (14). Nonetheless, discrepancies were apparent in framing of key factors and theoretical positions. More research and theoretical development are needed to ensure research is guided by a coherent and cohesive definition of resolution and acceptance. Our review did not explicitly include papers regarding grief, shame, loss and even relief, which often occur at later stages of the acceptance process. Future research that explores potential relationships between these factors and resolution are needed. Additionally, few studies examined multifaceted, interactive aspects of resolution. For example, the acceptance of one's role as a parent of an autistic child is a necessary part of accepting a child's care needs. Furthermore, factors such as knowledge and educational levels are also likely to interact to influence resolution. One important step for future research will be the development of valid and reliable measures of resolution, that are grounded in theory. Finally, future research examining diagnostic resolution and other constructs (e.g., hope), or how resolution may affect the disclosure of autism to others or to the child themself, or long-term effects on the parent-child relationship, are needed.

5. Conclusion

Receiving a child's autism diagnosis can be a stressful time (3) and resolution contributes to the wellbeing and the development of healthy parent-child relationships (6). This review identified articles examining factors contributing to diagnostic resolution associated with a child's diagnosis of autism. Although the identified studies supported associations between resolution and family wellbeing, the overall quality of studies was poor, relying on qualitative or correlational designs. Future research that better synthesize different approaches and tests theoretical processes with large, well-designed longitudinal studies, is therefore required.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

VN, SB, and DH conceived of the study. VN conducted the literature review, completed the systematic search, and analyzed the data under the supervision of SB and DH. VN wrote the first draft. All authors discussed the result and contributed to the writing of the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Pennington ML, Cullinan D, Southern LB. Defining autism: variability in state education agency definitions of and evaluations for autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res Treat. (2014) 2014:327271. doi: 10.1155/2014/327271

2. APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

3. Poslawsky IE, Naber FBA, Van Daalen E, Van Engeland H. Parental reaction to early diagnosis of their children's autism spectrum disorder: an exploratory study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2014) 45:294–305. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0400-z

4. Sher-Censor E, Dolev S, Said M, Baransi N, Amara K. Coherence of representations regarding the child, resolution of the child's diagnosis and emotional availability: a study of Arab-Israeli mothers of children with Asd. J Autism Dev Disord. (2017) 47:3139–49. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3228-8

5. Milshtein S, Yirmiya N, Oppenheim D, Koren-Karie N, Levi S. Resolution of the diagnosis among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: associations with child and parent characteristics. J Autism Dev Disord. (2010) 40:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0837-x

6. Sher-Censor E, Shahar-Lahav R. Parents' resolution of their child's diagnosis: a scoping review. Attach Hum Dev. (2022) 24:580–604. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2022.2034899

8. Dolev S, Sher-Censor E, Baransi N, Amara K, Said M. Resolution of the child's Asd diagnosis among Arab–Israeli mothers: associations with maternal sensitivity and wellbeing. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2016) 21:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.09.004

9. Kazak AE, Sheeran T, Marvin RS, Pianta R. Mothers' resolution of their childs's diagnosis and self-reported measures of parenting stress, marital relations, and social support. J Pediatr Psychol. (1997) 22:197–212. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.2.197

10. Marvin RS, Pianta RC. Mothers' reactions to their child's diagnosis: relations with security of attachment. J Clin Child Psychol. (1996) 25:436–45. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2504_8

11. Oppenheim D, Koren-Karie N, Dolev S, Yirmiya N. Maternal insightfulness and resolution of the diagnosis are associated with secure attachment in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Child Dev. (2009) 80:519–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01276.x

12. Lazarus RS, Cohen JB, Folkman S, Kanner A, Schaefer C. Psychological stress and adaptation: some unresolved issues. Selyes Guide Stress Res. (1980) 1:90–117.

13. Shih CK-Y. The acceptance process in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. PhD [dissertation]. Ann Arbor: Sofia University. (2019). Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2198683742

14. Da Paz NS, Siegel B, Coccia MA, Epel ES. Acceptance or despair? Maternal adjustment to having a child diagnosed with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. (2018) 48:1971–81. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3450-4

15. Wachtel K, Carter AS. Reaction to diagnosis and parenting styles among mothers of young children with Asds. Autism. (2008) 12:575–94. doi: 10.1177/1362361308094505

16. Rabba AS, Dissanayake C, Barbaro J. Parents' experiences of an early autism diagnosis: insights into their needs. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2019) 66. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101415

17. Chao KY, Chang HL, Chin WC Li HM, Chen SH. How Taiwanese parents of children with autism spectrum disorder experience the process of obtaining a diagnosis: a descriptive phenomenological analysis. Autism. (2018) 22:388–400. doi: 10.1177/1362361316680915

18. Lecciso F, Petrocchi S, Savazzi F, Marchetti A, Nobile M, Molteni M. The association between maternal resolution of the diagnosis of autism, maternal mental representations of the relationship with the child, and children's attachment. Life Span Disabil. (2013) 16:21–38.

19. Lord B, Ungerer J, Wastell C. Implications of resolving the diagnosis of Pku for parents and children. J Pediatr Psychol. (2008) 33:855–66. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn020

20. Makino A, Hartman L, King G, Wong PY, Penner M. Parent experiences of autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: a scoping review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. (2021) 8:267–84. doi: 10.1007/s40489-021-00237-y

21. Brown M, Marsh L, McCann E. Experiences of fathers regarding the diagnosis of their child with autism spectrum disorder: a narrative review of the international research. J Clin Nurs. (2021) 30:2758–68. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15781

22. Crane L, Batty R, Adeyinka H, Goddard L, Henry LA, Hill EL. Autism diagnosis in the United Kingdom: perspectives of autistic adults, parents and professionals. J Autism Dev Disord. (2018) 48:3761–72. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3639-1

23. Mount N, Dillon G. Parents' experiences of living with an adolescent diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Educ Child Psychol. (2014) 31:72–81.

24. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The Prisma 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

26. Alsayyari HI. Perceptions of Arab American mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder an exploratory study. PhD [dissertation]. Ann Arbor, MI: University of South Florida (2018). Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2027299308

27. Lopez K, Magaña S, Xu Y, Guzman J. Mother's reaction to autism diagnosis: a qualitative analysis comparing latino and white parents. J Rehabil. (2018) 84:41–50.

28. Ferguson A, Vigil DC. A comparison of the Asd experience of low-ses hispanic and non-hispanic white parents. Autism Res. (2019) 12:1880–90. doi: 10.1002/aur.2223

29. Reed P, Giles A, White S, Osborne LA. Actual and perceived speedy diagnoses are associated with mothers' unresolved reactions to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder for a child. Autism. (2019) 23:1843–52. doi: 10.1177/1362361319833676

30. Hotez E. A developmental perspective on parental cognitions and emotions in the context of a parent-mediated intervention for children with ASD. PhD [dissertation]. Ann Arbor, MI: City University of New York (2017). Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1798833013

31. Reed P, Osborne LA. Reaction to diagnosis and subsequent health in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. (2019) 23:1442–8. doi: 10.1177/1362361318815641

32. Heredia-Alvarado K, Chen H-M. A Mother's Narrative: Experience as a Latino Mother with a Child Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. California, CA: Alliant International University (2017). 194 p.

33. Rafferty D, Tidman L, Ekas NV. Parenting experiences of fathers of children with autism spectrum disorder with or without intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. (2020) 64:463–74. doi: 10.1111/jir.12728

34. Di Renzo M, Guerriero V, Zavattini GC, Petrillo M, Racinaro L, di Castelbianco FB. Parental attunement, insightfulness, and acceptance of child diagnosis in parents of children with autism: clinical implications. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1849. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01849

35. Crane L, Davidson I, Prosser R, Pellicano E. Understanding psychiatrists' knowledge, attitudes and experiences in identifying and supporting their patients on the autism spectrum: online survey. BJPsych Open. (2019) 5:e33. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.12

36. McCormack G, Dillon AC, Healy O, Walsh C, Lydon S. Primary care physicians' knowledge of autism and evidence-based interventions for autism: a systematic review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. (2020) 7:226–41. doi: 10.1007/s40489-019-00189-4

37. Anderberg E, South M. Predicting parent reactions at diagnostic disclosure sessions for autism. J Autism Dev Disord. (2021) 51:3533–46. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04817-5

Keywords: acceptance, autism spectrum disorder, diagnosis, hope, parent-child relationship, parental wellbeing, resolution, systematic review

Citation: Naicker VV, Bury SM and Hedley D (2023) Factors associated with parental resolution of a child's autism diagnosis: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 13:1079371. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1079371

Received: 25 October 2022; Accepted: 12 December 2022;

Published: 05 January 2023.

Edited by:

Miao Cao, Fudan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Gonca Özyurt, Izmir Katip Celebi University, TurkeyJonna Bobzien, Old Dominion University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Naicker, Bury and Hedley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Darren Hedley,  ZC5oZWRsZXlAbGF0cm9iZS5lZHUuYXU=

ZC5oZWRsZXlAbGF0cm9iZS5lZHUuYXU=

Vrinda V. Naicker

Vrinda V. Naicker Simon M. Bury

Simon M. Bury Darren Hedley

Darren Hedley