95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry , 01 December 2022

Sec. Addictive Disorders

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1040217

This article is part of the Research Topic Appropriateness and Safety of using Cannabinoid and Psychedelic Medicines as Treatments for Psychiatric Disorders View all 7 articles

The interest in psilocybin as a therapeutic approach has grown exponentially in recent years. Despite increasing access, there remains a lack of practical guidance on the topic for health care professionals. This is particularly concerning given the medical complexity and vulnerable nature of patients for whom psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy may be considered. This article aims to provide health care professionals with an overview of practical considerations for psilocybin therapy, rooted in a patient safety focus. Within this piece we will review basic psilocybin pharmacology and pharmacokinetics, indications, practical therapeutic strategies (e.g., dosing, administration, monitoring) and safety considerations (e.g., contraindications, adverse events, and drug interactions). With this information, our goal is to increase the knowledge and comfort of health care professionals to discuss and counsel their patients on psilocybin therapy, ultimately improving patient care and safety.

The interest in psilocybin as a therapeutic approach has grown exponentially in recent years. Primarily originating from fungal species within the genus Psilocybe, psilocybin is an indole alkaloid that is the main psychedelic ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms (1). Psilocybe mushroom species are pan-tropical, growing around the globe, including in the regions of the southeastern United States, Central and South America, South East Asia, and parts of Africa (2, 3). Although interest in psychedelics, and more specifically psilocybin, has emerged relatively recently within western culture, the traditional and ancestral use of psychedelic mushrooms originated generations ago in Mesoamerica (1, 4, 5). Civilizations such as the Aztec, Maya, Olmec, and Zapotec have documented use of psilocybin to evoke altered states of consciousness for healing rituals and religious ceremonies (4). In recent years, psilocybin has gained traction as a potential therapeutic agent within western health care. Several high profile trials have shown promising results for end of life distress and treatment-resistant depression (6–10).

Access to psilocybin worldwide has been largely restricted since the 1960’s (11). Richard Nixon’s “war on drugs” combined with tighter regulation of pharmaceutical research is largely responsible for the halting of psychedelic research and subsequent restricted access for therapeutic purposes in North America (11, 12). Despite support for the safety and efficacy of psilocybin and other psychedelics (13), research and exploration of psilocybin as a therapeutic has not re-emerged until recently.

The US Food and Drug Administration granted breakthrough therapy status to psilocybin in 2018 for treatment-resistant depression, and in 2019 for major depressive disorder. At a state-level, Oregon has more recently passed Ballot Measure 109 allowing for the manufacture, delivery, and administration of psilocybin within a to-be-developed state-run program – an initiative is being paralleled by efforts at other local jurisdictions (e.g., Denver).

In Canada, psilocybin possession is illegal except through Health Canada-approved pathways: research (including clinical trials), Section 56 exemption, and the Special Access Program (SAP). Both Section 56 exemptions and SAP allow for limited medical use of psilocybin outside of research settings if it is believed to be necessary for medical purposes (14, 15). Prior to 2022, Section 56 exemptions were the sole option, but this route was flawed due to: no access to legal/safe supply of psilocybin (patients had to source non-good manufacturing practice (GMP) psilocybin themselves through illicit sources), limited approvals being granted, lack of transparency on denials from Health Canada, long wait times of up to 300 days for approvals, and many exemption requests left unanswered (15). A primary pathway was created following a 2022 SAP amendment, where SAP submissions receive responses within 24–48 h and, if approved, patients can procure regulated psilocybin from Health Canada licensed dealers. Section 56 exemptions have now become a secondary pathway to be used after a denial is received for a SAP request (16).

As access and public awareness to psilocybin increases, it is prudent for all health care professionals (HCP) to have a baseline pharmacotherapy knowledge of this treatment option. Understanding and applying patient specific safety considerations is essential in assessing psilocybin eligibility and appropriately managing patient care, even if a HCP is involved indirectly. Furthermore, due to the movement of global jurisdictions toward decriminalization of various psychedelic substances, discussions on personal use (with or without therapeutic intent) may also become a part of primary care, similar to what has happened with cannabis.

There remains a lack of practical clinical guidance for HCPs on Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy (PAP). This is particularly concerning given the complex and medically vulnerable nature of patients who may qualify for this treatment modality. As such, this article aims to provide HCPs with an overview of the practical considerations for PAP that can be utilized when considering, counseling, prescribing, or monitoring psilocybin use in a patient. Although this paper focuses on the medical use and access channels to psilocybin, we acknowledge and support that non-medical model access needs to be established as there exists a spectrum of use that extends beyond prescriptive medical access.

Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) and its pharmacologically active metabolite psilocin (4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) are the major psychoactive alkaloids in several species of “magic” mushrooms (17, 18). They are tryptamine/indolamine hallucinogens, structurally related to serotonin (17). Psilocybin and psilocin both display non-specific partial agonist activity on the serotonergic neurotransmitter system, with varying binding affinities at several serotonergic receptor sites (19, 20).

Psilocin, being highly lipophilic, is able to cross the blood-brain barrier and bind to several serotonergic receptors with a particularly high binding affinity to 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A (5-HT2A) receptor as compared to psilocybin which is hydrophilic and cannot readily cross the blood-brain barrier (17, 21–23). As with all classical tryptamine psychedelics, the subjective effects of psilocin are mediated by biased (functionally selective) agonism of 5-HT2A receptors (24). Psilocin binding to the 5-HT2A receptor creates functional selectivity which favors the psychedelic signaling pathway over the default serotonin pathway (22, 24–26). The downstream signaling bias, as a result of functional selectivity, leads to increased glutamate release which also likely contributes to the psychedelic effects of psilocin (24, 27). Additionally, it is proposed that psilocin’s neurobiological signaling pathways induce changes in neuroplasticity through (but not limited to) increased expression of glutamate and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (28, 29). The potential connection between BDNF and depression (30, 31) is one suggested mechanism for psilocin’s therapeutic effect (28, 29).

5-HT2A receptors are also highly expressed in the visual cortex, contributing to the visual hallucinations associated with psilocin (27, 32). Antagonism of these receptors using the 5-HT2A receptor blocker ketanserin has shown attenuation of hallucinatory effects, supporting the underlying psychedelic mechanism of action through 5-HT2A receptors (33–35). Additional binding sites, including 5-HT1A and 5-HT2C, may potentially play a role in some of the psychedelic effects of psilocin, but further studies are needed to determine the extent of this contribution (20, 22, 24).

Psilocybin is a prodrug and must be converted to its metabolite psilocin in order to cross the blood-brain barrier and elicit its neurological effects. Following oral ingestion, psilocybin is rapidly dephosphorylated via the acidic environment of the stomach into psilocin. Any remaining psilocybin is then converted in the intestines, blood, and kidneys through alkaline phosphatase to produce the active, lipophilic form, psilocin (17, 23). It is important to note that the majority of psilocybin efficacy and pharmacokinetic studies are based on patients fasting for an average of 2-4 h (except water). In order to ensure more predictable kinetics, good clinical practice should include instructions for consuming psilocybin on an empty stomach.

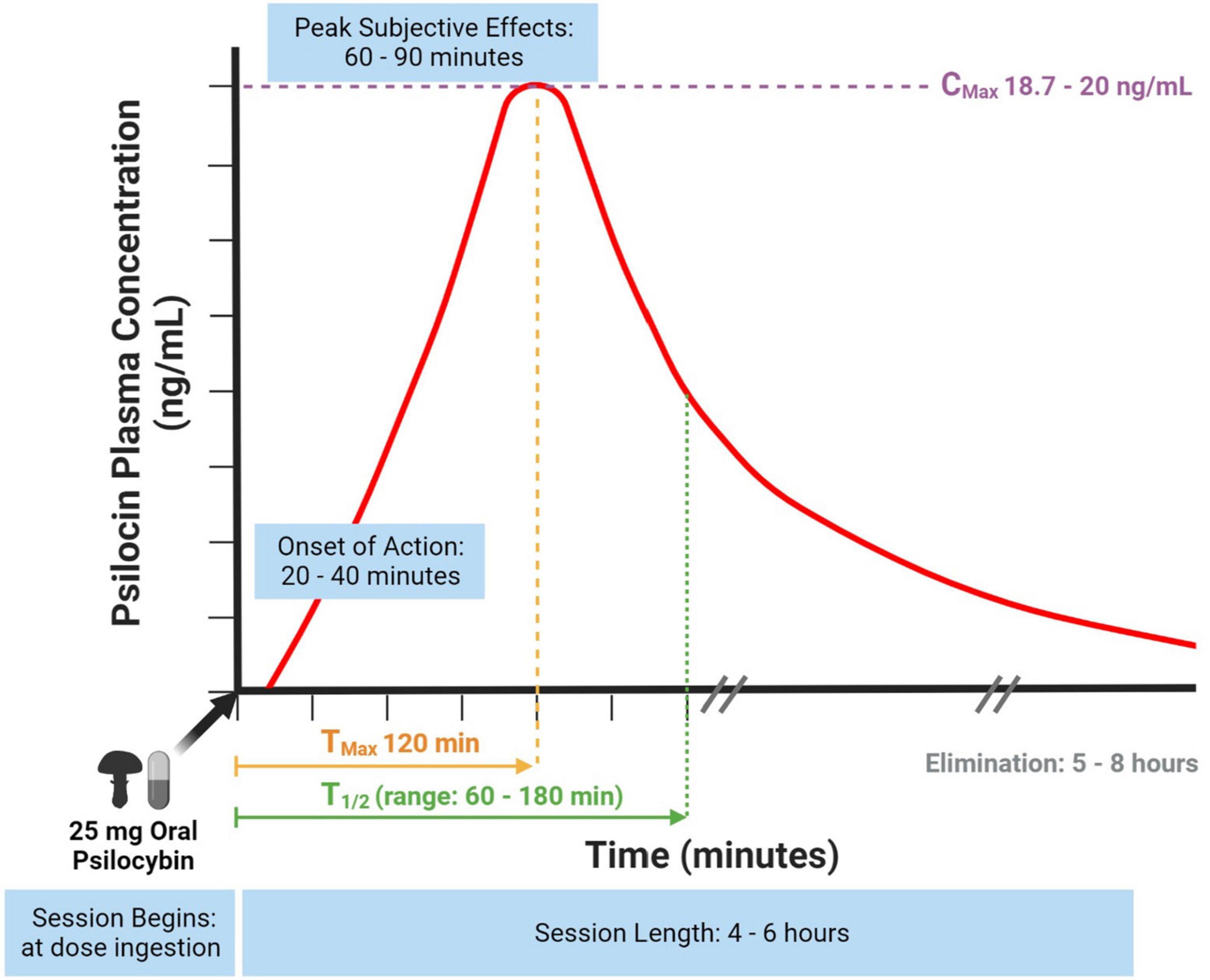

The bioavailability of psilocybin is approximately 50% following oral ingestion (17). Psilocybin is a water-soluble compound detectable in plasma within 20–40 min (Figure 1) (17). Psilocin is extensively distributed through the bloodstream to all tissues, including crossing the blood-brain barrier to elicit central nervous system effects (23). Psilocin is detectable in plasma after 30 min (17) and displays linear pharmacokinetics (36).

Figure 1. Psilocin concentration to session time curve using a standard psilocybin dose. Information gathered from (17, 18, 23, 28, 36, 37).

In earlier studies, the half-life (T1/2) of psilocin was found to be 50 min and T1/2 of psilocybin being 160 min (17) whereas newer studies using a fixed 25 mg psilocybin dose and specifically measuring unconjugated psilocin found its T1/2 to be 108 min (range: 66–132 min) (Figure 1) (28). The dose response curve correlates to a session experience with an onset of action at 20-40 min, peak subjective effects at 60–90 min and an active duration of 4–6 h (Figure 1) (18). A dose-escalating study of oral psilocybin found an average psilocin T1/2 of 3 h, but also found minor variability (standard deviation 1.1) between participants (Figure 1) (36). Variability was not predicted by body weight, and may instead be due to less or more hydrolysis of the psilocin glucuronide metabolite (36). After a 25 mg fixed oral dose of psilocybin, one study reported a maximal psilocin plasma concentration at 120 min (Tmax) of 20 ng/mL (Cmax) (28) and similarly, another study reported a Cmax of 18.7 ng/mL (37).

A recent study shows that ∼80% of all circulating psilocin is metabolized by hepatic phase II glucuronidation (conjugation) through UGT 1A10 and UGT 1A9 enzymes into psilocin-O-glucuronide (23). This inactive secondary metabolite is renally cleared, along with ∼2% of combined unconjugated psilocin and unmetabolized psilocybin (36). The remaining ∼20% of circulating psilocin is metabolized through several pathways (including MAO, ALDH, cytochrome oxidase, etc.) and excreted through the bile into the stool (23). Complete psilocin excretion occurs within 24 h, with the majority occurring in the first 8 h (17, 23).

The strongest evidence for psilocybin is from clinical trials in cancer-related depression and anxiety and treatment-resistant depression (Table 1) (7–10, 38–41). Alcohol use disorder and tobacco addiction have been found to have moderate-level evidence from several clinical trials (42–45).

Preliminary research (e.g., proof-of-concept, open label trials, or case series) suggests there may also be utility for psilocybin in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (46), cluster headaches (47, 48), migraines (49), and demoralization with an AIDS diagnosis (50). Currently, clinical trials are being conducted on a wide range of conditions including migraines, addiction (tobacco, alcohol, cocaine), anorexia, bipolar disorder, chronic pain, major depressive disorder, and OCD (51).

Many earlier psilocybin trials initially dosed using body weight, with doses generally ranging from 0.2–0.4 mg/kg of psilocybin per session. Protocols consisted of either a single dose or two doses separated by an average 3–4 week washout period. Current clinical trial protocols have switched to using a fixed psilocybin dose, most commonly 25 mg, which is consistent with the previous 0.3 mg/kg weight-based dosing (36). The fixed 25 mg dose approach has been validated in a recent secondary analysis of prior trial data, which found no significant differences for psychedelic effects compared to weight-based doses of 0.29 mg/kg and 0.43 mg/kg (52). As the renally cleared secondary metabolite (psilocin-O-glucuronide) is inactive, it suggests that patients with mild-moderate renal impairment do not require a dose reduction (36). Table 2 compares several dosing ranges for both psilocybin and dried Psilocybe cubensis mushroom (a common research species) based on the above studies that can inform dosing guidelines.

Outside of research or medical access settings (such as Health Canada SAP), a common source of psilocybin is from dried “magic” mushrooms. This requires a conversion to determine the estimated weight of dried mushrooms to consume in order to arrive at the intended psilocybin dose. Based on several studies, the average psilocybin content is ∼1% psilocybin per one gram of dried Psilocybe cubensis mushroom; therefore, a 25 mg psilocybin fixed dose is approximately 2.5 grams of dried Psilocybe cubensis mushroom. However, it is important to note, there is intra- and inter-species variability of psilocybin content (53, 54). In psilocybin-naive patients using dried mushrooms, it is good clinical practice to start at a lower dried mushroom weight in the event that the actual psilocybin content is higher in any given batch. The variability in psilocybin content can range on average from 0.5–2% dried mushroom weight based on species (53, 54).

Underlying causes for varying sensitivities to psilocybin effects are not fully understood. Lab research in cells points to differences in 5-HT2A receptors through single nucleotide polymorphism variants, such as Ala230Thr, as one factor (55). Clinically, these varying sensitivities are observed with a lack of fasting and certain conditions such as reduced gastric acid, altered gastric motility, or liver dysfunction.

The administration of psilocybin should be accompanied with assisted psychotherapy to maximize potential benefits. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy focuses on three stages: pretreatment, treatment, and posttreatment (56). Pre-treatment heavily focuses on building therapeutic rapport and trust (56). One fundamental therapeutic concept is that of “set and setting” which refers to appropriate patient preparation so that they are informed on what to expect during their session both from a mindset and environmental perspective. Treatment sessions are generally conducted in a non-directive, supportive setting and utilize a variety of tools such as a music playlist, meditation, and breath work (56, 57). Posttreatment focuses on supporting the integration of experiences (56). Detailed practical guidance on assisted-psychotherapy is out of scope for the present manuscript, however, it has been noted in a variety of other publications [e.g., (56–60)].

Most contraindications are due to increased risk for psychological distress, including the rare, but potential, serious adverse event of psychosis (6–8, 38, 39, 61). History of schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder are generally contraindicated for psilocybin (6–8, 38, 39, 61); however, future observational data in these conditions may provide a more detailed risk-benefit. Pregnancy and breastfeeding are also contraindicated given insufficient scientific evidence to assess risk.

The primary physical concerns are due to transient increases in heart rate and blood pressure following psilocybin ingestion (8, 62). Thus, serious or uncontrolled cardiovascular conditions are often considered to be relative contraindications (39, 61).

The concurrent use of psychotropic medications, especially antidepressants and antipsychotics, may introduce risks (safety concerns) or alter benefits (efficacy concerns). Many of these medications modulate the serotonin system including 5-HT2A receptors (61). As psilocybin and psilocin mainly interact with the serotonergic system, particularly 5-HT2A, there is a risk for pharmacodynamic drug interactions (17).

The most common pharmacodynamic interaction may result in a heightened or blunted psychedelic experience. For example, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) may increase the intensity, while monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may decrease the intensity (61, 63–67).

Drug interactions between serotonergic drugs may lead to a rare, but serious, condition called serotonin syndrome in which excessive serotonin signaling can lead to a potentially life-threatening adverse drug reaction (68, 69).

Clinical trial protocols often require the tapering and washout of these medications due to the concern of serotonin syndrome, however, there is a lack of published serotonin toxicity cases. A recent standard dose psilocybin study of patients on a concurrent SSRI were found to have no additional safety concerns such as QT prolongation (an abnormally extended interval between heart contracting and relaxing), serotonin syndrome and no reduction in efficacy such as impact to positive mood (28). This continues to be an area of further investigation.

In addition, potential pharmacokinetic drug interactions exist for phase II UGT substrates. As psilocin is primarily metabolized by UGT 1A10 and 1A9 (23), medications that can inhibit or induce these enzymes must be held or tapered prior to administration of psilocybin. Some examples of UGT 1A10/1A9 inhibitors include diclofenac (a Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) and probenecid (a uric acid reducer).

A detailed medication screening should be completed, especially for antidepressants, antipsychotics, psychostimulants, lithium, and other dopaminergic or serotonergic agents (39, 42, 61). If there is concern for drug-drug interactions, an individualized risk-benefit assessment should be conducted with an appropriate drug taper schedule if warranted. Health care professionals should be aware of potential discontinuation syndrome and monitor for signs of distress if tapering psychotropic medications prior to psilocybin administration.

Due to psilocybin’s large therapeutic index (1:1000) and a typically unattainable lethal dose, psilocybin has a favorable safety profile (6, 9, 10, 42, 61, 62, 70, 71). Relative to other psychedelics (such as MDMA, DMT, etc.), psilocybin has lower occurrence of seizures, hospital admissions and other serious adverse effects, and lacks addictive or reinforcing properties (62, 72). Several dose-escalating studies have tested the subjective psychedelic effects in supratherapeutic doses, e.g., 50–60 mg or 5–6 grams, and found positive results with little-to-no safety concerns (36, 37, 73).

The primary risk for psilocybin is psychological safety, not physiological safety as it is for most classic drugs (e.g., opioids, sedatives, stimulants) (61, 69). Properly conducted PAP aims to minimize the potential for psychological harms through appropriate patient preparation and close patient monitoring. Despite this, the acute psychotomimetic effects associated with psilocybin may still pose a risk for psychological distress, and in rare cases, psychosis (61, 69). Physical and psychological adverse events are reported in Table 3. Many of these are transient in nature and related to the therapeutic nature of emotional processing in session (blood pressure, heart rate, anxiety). Transient headaches may also arise the day after treatment. Data from clinical trials, in which proper screening is completed and consumption is monitored, report no serious adverse events (6, 9, 10, 38, 39, 42, 46, 71).

As interest and access to psilocybin as a therapeutic option grows, HCPs require sufficient information to navigate potential psilocybin use in their patients. At a time where the use of psilocybin is becoming more common, it is imperative for HCPs to have a base-level understanding of psilocybin, its indications, and key safety considerations in order to guide and counsel their patients. These factors also play an important role in informing policymakers as they create regulations and guidance for psilocybin use. Development of health care education in order to equip HCPs with the necessary knowledge to ensure patient safety are worthwhile goals.

CM contributed to conception of manuscript. All authors wrote sections of the manuscript, contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Justin C. Strickland and Dr. Houman Farzin for their assistance in reviewing and finalizing this manuscript. Figure 1 was created with BioRender.com.

LL had received compensation for consulting with Dimensions Health Centres. JD had received compensation for consulting and advisory work with TheraPsil, Roots to Thrive, and Numinus Wellness.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Van Court RC, Wiseman MS, Meyer KW, Ballhorn DJ, Amses KR, Slot JC, et al. Diversity, biology, and history of psilocybin-containing fungi: Suggestions for research and technological development. Fungal Biol. (2022) 126:308–19. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2022.01.003

2. Guzmán G. The hallucinogenic mushrooms: diversity, traditions, use and abuse with special reference to the genus psilocybe. In Fungi from Different Environments. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press (2009).

3. Guzmán, G, Allen JW, Gartz J. A worldwide geographical distribution of the neurotropic fungi, an analysis and discussion. Ann Mus Civ Rovereto. (1998) 14:92.

4. Carod-Artal FJ. Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures. Neurología (English Edition). (2015) 30:42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2011.07.003

5. Santiago FH, Moreno JP, Cázares BX, Suárez JJA, Trejo EO, de Oca GMM, et al. Traditional knowledge and use of wild mushrooms by Mixtecs or Ñuu savi, the people of the rain, from Southeastern Mexico. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2016) 12:35. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0108-9

6. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Rucker J, Day CMJ, Erritzoe D, Kaelen M, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) 3: 619–27.

7. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, Rucker J, Watts R, Erritzoe DE, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology. (2018) 235:399–408. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4771-x

8. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, Umbricht A, Richards WA, Richards BD, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. (2016) 30:1181–97. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675513

9. Grob CS, Danforth AL, Chopra GS, Hagerty M, McKay CR, Halberstadt AL, et al. Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2011) 68:71–8.

10. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. (2016) 30:1165–80. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675512

11. Hall, W. Why was early therapeutic research on psychedelic drugs abandoned? Psychol Med. (2021):1–6. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721004207

12. Shortall S. Psychedelic drugs and the problem of experience *. Past Present. (2014) 222(suppl_9), 52:187–206.

13. Rucker JJ, Jelen LA, Flynn S, Frowde KD, Young AH. Psychedelics in the treatment of unipolar mood disorders: a systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. (2016) 30:1220–9.

14. Government of Canada. Subsection 56(1) class exemption for practitioners, agents, pharmacists, persons in charge of a hospital, hospital employees, and licensed dealers to conduct activities with psilocybin and MDMA in relation to a special access program authorization. (2022). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/controlled-substances-precursor-chemicals/policy-regulations/policy-documents/subsection-56-1-class-exemption-conducting-activities-psilocybin-mdma-special-access-program-authorization.html (accessed November 3, 2022).

15. City of Vancouver. Request for an exemption from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) pursuant to section 56(1) that would decriminalize personal possession of illicit substances within the City of Vancouver. (2021). Available online at: https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/request-for-exemption-from-controlled-drugs-and-substances-act.pdf (accessed August 19, 2022).

16. Government of Canada. Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Relating to Restricted Drugs (Special Access Program) [Internet]. Government of Canada, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Integrated Services Branch, Canada Gazette. (Vol. 156). (2022). Available online at: https://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2022/2022-01-05/html/sor-dors271-eng.html (accessed August 19, 2022).

17. Passie T, Seifert J, Schneider U, Emrich HM. The pharmacology of psilocybin. Addict Biol. (2002) 7:357–64.

18. Tylš F, Páleníček T, Horáček J. Psilocybin – Summary of knowledge and new perspectives. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2014) 24:342–56. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006

19. Halberstadt AL, Geyer MA. Multiple receptors contribute to the behavioral effects of indoleamine hallucinogens. Neuropharmacology. (2011) 61:364–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.017

20. Rickli A, Moning OD, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive tryptamines compared with classic hallucinogens. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2016) 26:1327–37.

21. Besnard J, Ruda GF, Setola V, Abecassis K, Rodriguiz RM, Huang XP, et al. Automated design of ligands to polypharmacological profiles. Nature. (2012) 492:215–20.

22. Blough BE, Landavazo A, Decker AM, Partilla JS, Baumann MH, Rothman RB. Interaction of psychoactive tryptamines with biogenic amine transporters and serotonin receptor subtypes. Psychopharmacology (Berl). (2014) 231:4135–44. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3557-7

23. Dinis-Oliveira RJ. Metabolism of psilocybin and psilocin: clinical and forensic toxicological relevance. Drug Metab Rev. (2017) 49:84–91. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2016.1278228

24. López-Giménez JF, González-Maeso J. Hallucinogens and Serotonin 5-HT2A Receptor-Mediated Signaling Pathways. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. (2018) 36:45–73.

25. McKenna DJ, Repke DB, Lo L, Peroutka SJ. Differential interactions of indolealkylamines with 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor subtypes. Neuropharmacology. (1990) 29:193–8.

26. Mertens LJ, Wall MB, Roseman L, Demetriou L, Nutt DJ, Carhart-Harris RL. Therapeutic mechanisms of psilocybin: Changes in amygdala and prefrontal functional connectivity during emotional processing after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. (2020) 34:167–80. doi: 10.1177/0269881119895520

27. Ling S, Ceban F, Lui LMW, Lee Y, Teopiz KM, Rodrigues NB, et al. Molecular mechanisms of psilocybin and implications for the treatment of depression. CNS Drugs. (2022) 36:17–30. doi: 10.1007/s40263-021-00877-y

28. Becker AM, Holze F, Grandinetti T, Klaiber A, Toedtli VE, Kolaczynska KE, et al. Acute effects of psilocybin after escitalopram or placebo pretreatment in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2022) 111:886–95.

29. de Vos CMH, Mason NL, Kuypers KPC. Psychedelics and neuroplasticity: A systematic review unraveling the biological underpinnings of psychedelics. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:724606. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.724606

30. Arosio B, Guerini FR, Voshaar RCO, Aprahamian I. Blood Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and Major Depression: Do We Have a Translational Perspective? Front Behav Neurosci. (2021) 15:626906. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.626906

31. Yang T, Nie Z, Shu H, Kuang Y, Chen X, Cheng J, et al. The Role of BDNF on Neural Plasticity in Depression. Front Cell Neurosci. (2020) 14:82. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00082

32. Mahapatra A, Gupta R. Role of psilocybin in the treatment of depression. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. (2017) 7:54–6.

33. Batman AM, Munzar P, Beardsley PM. Attenuation of nicotine’s discriminative stimulus effects in rats and its locomotor activity effects in mice by serotonergic 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonists. Psychopharmacology. (2005) 179:393–401. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2035-z

34. Lee HM, Roth BL. Hallucinogen actions on human brain revealed. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:1820–1.

35. Vollenweider FX, Kometer M. The neurobiology of psychedelic drugs: implications for the treatment of mood disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2010) 11: 642–51.

36. Brown RT, Nicholas CR, Cozzi NV, Gassman MC, Cooper KM, Muller D, et al. Pharmacokinetics of escalating doses of oral psilocybin in healthy adults. Clin Pharmacokinet. (2017) 56:1543–54.

37. Dahmane E, Hutson PR, Gobburu JVS. Exposure-Response analysis to assess the concentration-qtc relationship of psilocybin/psilocin. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. (2021) 10:78–85. doi: 10.1002/cpdd.796

38. Carhart-Harris RL, Giribaldi B, Watts R, Baker-Jones M, Murphy-Beiner A, Murphy R, et al. Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. New Engl J Med. (2021) 384:1402–11.

39. Davis AK, Barrett FS, May DG, Cosimano MP, Sepeda ND, Johnson MW, et al. Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. (2021) 78:481–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3285

40. Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Potential therapeutic effects of psilocybin. Neurotherapeutics. (2017) 14:734–40.

41. Shore RJ, Ioudovski P, McKeown S, Dumont E, Goldie C. Mapping psilocybin-assisted therapies: a scoping review. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2019) doi: 10.1101/2019.12.04.19013896

42. Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, Wilcox CE, Barbosa PCR, Strassman RJ. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol. (2015) 29:289–99.

43. Bogenschutz MP, Podrebarac SK, Duane JH, Amegadzie SS, Malone TC, Owens LT, et al. Clinical interpretations of patient experience in a trial of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for alcohol use disorder. Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:100. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00100

44. Bogenschutz MP, Ross S, Bhatt S, Baron T, Forcehimes AA, Laska E, et al. Percentage of heavy drinking days following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy vs placebo in the treatment of adult patients with alcohol use disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. (2022) 79:953–62. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2096

45. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Cosimano MP, Griffiths RR. Pilot Study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. J Psychopharmacol. (2014) 28:983–92. doi: 10.1177/0269881114548296

46. Moreno FA, Wiegand CB, Taitano EK, Delgado PL. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of psilocybin in 9 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2006) 67:1735–40.

47. Schindler EAD, Gottschalk CH, Weil MJ, Shapiro RE, Wright DA, Sewell RA. Indoleamine hallucinogens in cluster headache: Results of the clusterbusters medication use survey. J Psychoact Drugs. (2015) 47:372–81. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2015.1107664

48. Sewell RA, Halpern JH, Pope HG. Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD. Neurology. (2006) 66:1920–2.

49. Schindler EAD, Sewell RA, Gottschalk CH, Luddy C, Flynn LT, Lindsey H, et al. Exploratory controlled study of the migraine-suppressing effects of psilocybin. Neurotherapeutics. (2021) 18:534–43. doi: 10.1007/s13311-020-00962-y

50. Anderson BT, Danforth A, Daroff PR, Stauffer C, Ekman E, Agin-Liebes G, et al. Psilocybin-assisted group therapy for demoralized older long-term AIDS survivor men: An open-label safety and feasibility pilot study. EClinicalMedicine. (2020) 27:100538. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100538

51. National Institute of Health. ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health (2022).

52. Garcia-Romeu A, Barrett FS, Carbonaro TM, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Optimal dosing for psilocybin pharmacotherapy: Considering weight-adjusted and fixed dosing approaches. J Psychopharmacol. (2021) 35:353–61. doi: 10.1177/0269881121991822

53. Beug MW, Bigwood J. Psilocybin and psilocin levels in twenty species from seven genera of wild mushrooms in the Pacific Northwest, U.S.A. J Ethnopharmacol. (1982) 5:271–85. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(82)90013-7

54. Bigwood J, Beug MW. Variation of psilocybin and psilocin levels with repeated flushes (harvests) of mature sporocarps of Psilocybe cubensis (earle) singer. J Ethnopharmacol. (1982) 5:287–91. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(82)90014-9

55. Schmitz GP, Jain MK, Slocum ST, Roth BL. 5-HT2A SNPs Alter the pharmacological signaling of potentially therapeutic psychedelics. ACS Chem Neurosci. (2022) 13:2386–98. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00815

56. Horton DM, Morrison B, Schmidt J. Systematized review of psychotherapeutic components of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. APT. (2021) 74:140–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.20200055

57. Phelps J. Developing guidelines and competencies for the training of psychedelic therapists. J Hum Psychol. (2017) 57:450–87.

58. Timmermann, C, Watts R, Dupuis D. Towards psychedelic apprenticeship: Developing a gentle touch for the mediation and validation of psychedelic-induced insights and revelations. Transcult Psychiatry. (2022) 59:13634615221082796. doi: 10.1177/13634615221082796

59. Penn AD, Phelps J, Rosa WE, Watson J. Psychedelic-Assisted psychotherapy practices and human caring science: Toward a care-informed model of treatment. J Hum Psychol. (2021): doi: 10.1177/00221678211011013

60. Sloshower J, Guss J, Krause R, Wallace RM, Williams MT, Reed S, et al. Psilocybin-assisted therapy of major depressive disorder using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a therapeutic frame. J Contextual Behav Sci. (2020) 15:12–9.

61. O’Donnell KC, Mennenga SE, Bogenschutz MP. Psilocybin for depression: Considerations for clinical trial design. J Psychedelic Stud. (2019) 3:269–79.

62. Leonard JB, Anderson B, Klein-Schwartz W. Does getting high hurt? Characterization of cases of LSD and psilocybin-containing mushroom exposures to national poison centers between 2000 and 2016. J Psychopharmacol. (2018) 32:1286–94. doi: 10.1177/0269881118793086

63. Bonson KR, Buckholtz JW, Murphy DL. Chronic administration of serotonergic antidepressants attenuates the subjective effects of LSD in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. (1996) 14:425–36. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00145-4

64. Bonson KR, Murphy DL. Alterations in responses to LSD in humans associated with chronic administration of tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors or lithium. Behav Brain Res. (1996) 73:229–33.

65. Gómez-Gil E, Gastó C, Carretero M, Díaz-Ricart M, Salamero M, Navinés R, et al. Decrease of the platelet 5-HT2A receptor function by long-term imipramine treatment in endogenous depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. (2004) 19:251–8. doi: 10.1002/hup.583

66. Meyer JH, Kapur S, Eisfeld B, Brown GM, Houle S, DaSilva J, et al. The effect of paroxetine on 5-HT(2A) receptors in depression: an [(18)F]setoperone PET imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. (2001) 158:78–85.

67. Yamauchi M, Miyara T, Matsushima T, Imanishi T. Desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor function by chronic administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Brain Res. (2006) 1067:164–9.

68. Callaway JC, Grob CS. Ayahuasca preparations and serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a potential combination for severe adverse interactions. J Psychoactive Drugs. (1998) 30:367–9. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399712

69. Johnson MW, Richards W, Griffiths RR. Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J Psychopharmacol. (2008) 22: 603–20.

71. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Richards WA, Richards BD, McCann U, Jesse R. Psilocybin occasioned mystical-type experiences: immediate and persisting dose-related effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl). (2011) 218:649–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2358-5

72. Leary T, Metzner R, Alpert R. The Psychedelic Experience: a Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Galle: Citadel (1964).

73. Nicholas CR, Henriquez KM, Gassman MC, Cooper KM, Muller D, Hetzel S, et al. High dose psilocybin is associated with positive subjective effects in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. (2018) 32:770–8. doi: 10.1177/0269881118780713

Keywords: psilocybin, psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy, psychedelics, psilocin, magic mushrooms, patient safety

Citation: MacCallum CA, Lo LA, Pistawka CA and Deol JK (2022) Therapeutic use of psilocybin: Practical considerations for dosing and administration. Front. Psychiatry 13:1040217. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1040217

Received: 09 September 2022; Accepted: 08 November 2022;

Published: 01 December 2022.

Edited by:

Grace Blest-Hopley, King’s College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Hugo Bottemanne, INSERM U1127 Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle Épinière (ICM), FranceCopyright © 2022 MacCallum, Lo, Pistawka and Deol. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Caroline A. MacCallum, aW5mb0BkcmNhcm9saW5lbWFjY2FsbHVtLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.