94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

METHODS article

Front. Psychiatry, 24 November 2021

Sec. Psychopharmacology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.787043

This article is part of the Research TopicAdvances in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Psychiatric Subjects: Analytical Strategies and Clinical ApproachesView all 8 articles

Xenia M. Hart1*

Xenia M. Hart1* Luzie Eichentopf1

Luzie Eichentopf1 Xenija Lense1

Xenija Lense1 Thomas Riemer2

Thomas Riemer2 Katja Wesner1

Katja Wesner1 Christoph Hiemke3

Christoph Hiemke3 Gerhard Gründer1

Gerhard Gründer1Background: For many psychotropic drugs, monitoring of drug concentrations in the blood (Therapeutic Drug Monitoring; TDM) has been proven useful to individualize treatments and optimize drug effects. Clinicians hereby compare individual drug concentrations to population-based reference ranges for a titration of prescribed doses. Thus, established reference ranges are pre-requisite for TDM. For psychotropic drugs, guideline-based ranges are mostly expert recommendations derived from a conglomerate of cohort and cross-sectional studies. A systematic approach for identifying therapeutic reference ranges has not been published yet. This paper describes how to search, evaluate and grade the available literature and validate published therapeutic reference ranges for psychotropic drugs.

Methods/Results: Following PRISMA guidelines, relevant databases have to be systematically searched using search terms for the specific psychotropic drug, blood concentrations, drug monitoring, positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). The search should be restricted to humans, and diagnoses should be pre-specified. Therapeutic references ranges will not only base upon studies that report blood concentrations in relation to clinical effects, but will also include implications from neuroimaging studies on target engagement. Furthermore, studies reporting concentrations in representative patient populations are used to support identified ranges. Each range will be assigned a level of underlying evidence according to a systematic grading system.

Discussion: Following this protocol allows a comprehensive overview of TDM literature that supports a certain reference range for a psychotropic drug. The assigned level of evidence reflects the validity of a reported range rather than experts' opinions.

Many psychotropic drugs have been in use for over 60 years. Great efforts have been made to individualize treatment with the available compounds (1). The only tool for such a personalization, which is now widely used in psychiatric clinical practice, is therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). TDM-guided therapies aim at titrating drug levels in the blood within a range that is clinically helpful without causing harm. A key principle of TDM is the comparison of individual drug concentrations in the blood to a population-based reference range, the drug-specific therapeutic reference range. At concentrations below the lower limit of this range, a drug-induced response is unlikely to occur. Tolerability is expected to decrease at concentrations above the upper limit. Lower and upper limit of a reference range, respectively, should derive from well-designed clinical studies that relate measured drug concentrations to treatment response or specific adverse drug reactions. For many psychotropic drugs relationships between target engagement (TE) and drug blood concentrations on the one hand and clinical effects and side effects on the other hand are well-documented (2–4). TE by the respective drug (usually occupancy of neuroreceptors or transporters) can be quantified using molecular neuroimaging techniques like positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). These studies supplement data from clinical studies in a meaningful manner. An overview of systematic reviews which aimed at finding therapeutic reference ranges, stated: “[W]e were not aware of a consensus on the optimum methodology for a systematic review that aims to determine upper and lower limits of the therapeutic range for a particular drug” (5). Inconsistent methodologies concerning the way that reference ranges were found have led to a high variation of ranges reported in the literature. In addition, current rating instruments are not designed to rate the quality of TDM studies. Understandably, this has led to criticism among clinicians, and reported ranges are more or less considered experts' opinions. As pointed out in a critical commentary, this holds also true for previously published TDM Consensus Guidelines that report therapeutic reference ranges for 154 neuropsychiatric drugs along with levels of recommendation for their clinical use (6–9).

This research protocol provides a tool for searching, evaluating and grading available literature in order to validate published therapeutic reference ranges for psychotropic drugs. Particular emphasis will be given to studies which investigate blood levels and clinical outcomes, such as response to drug treatment or adverse drug reactions. Studies on target engagement (usually receptor/transporter occupancy) from molecular neuroimaging can supplement the clinical evidence. The following research questions are addressed: Is there evidence for a concentration/response relationship and for a concentration/side effect relationship for a certain drug? Is there evidence that supports a lower or upper limit of a therapeutic reference range? How does the drug concentration relate to target engagement (usually receptor/transporter occupancy); and are these findings in line with the concentration/effect relationships and drug concentrations found in patients with psychiatric disorders receiving therapeutically effective doses? The authors may furthermore compute preliminary reference ranges from relevant studies, such as mean or median concentration ranges in patients with psychiatric disorders. This systematic review protocol follows the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) (10) statement. Corresponding systematic reviews for four individual psychotropic drugs have been registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42020215873, CRD42021216182, CRD42020218248, CRD42020215872).

The first step is a systematic search for relevant literature using established databases, such as MEDLINE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library. Search terms for the relevant drug, blood concentrations, drug monitoring, PET and SPECT are helpful. No preset database search filters and no restrictions in regard to the publication date are to be applied. The search is complemented by a hand search in the reference lists of the included publications and in former published guidelines. An example of a search strategy for the antidepressant drug escitalopram is provided in the Supplementary Material.

There are no restrictions in regard to the study design, e.g., both observational and interventional studies are included. Case reports and case series, however, are excluded. The search is restricted to humans, and relevant diagnoses have to be pre-specified, assuming that a specific reference range will only be valid for a particular indication. In order to be included in the evaluation of a certain concentration/effect relationship, studies must refer to patients with psychiatric disorders under monotherapy of the respective drug, meaning no other drug that mediates the relevant treatment effect should be administered concurrently. If at least one measurement was performed before the start of the new medication, the study will be considered for the computation of preliminary ranges only. Drug concentrations in blood should be measured after intake of the respective drug under steady-state conditions. Exceptions are made for molecular neuroimaging studies, which will be considered independent of the dosing period and diagnosis (studies with healthy volunteers included). Since studies investigating long-acting depot formulations are scarce, these studies will also be evaluated without regard to steady state conditions.

After the removal of duplicates, screening of the literature has to be performed by two independent reviewers according to PRISMA guidelines. In cases where a final decision on the inclusion cannot be made based on the abstract alone, the full article must be reviewed. Any disagreements between the two reviewers must be resolved in a subsequent discussion. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1. All studies that examine the drug blood concentrations in relation to clinical effect (without concomitant psychiatric medication), dose or target engagement have to be identified. Studies that did not ensure steady-state must be excluded (not necessarily applicable for imaging studies and studies with depot formulations). Studies performing population pharmacokinetic modeling analyses should be identified in the systematic review in order to discuss moderating factors on drug concentrations.

Both reviewers have to independently extract the following information from each study: lead author, year, title, country, study design, number and details of subjects, diagnosis, mean dose ± standard deviation (SD), mean blood concentration ± SD, concentration range, clinical efficacy or side effect measures, and main outcomes. Any disagreements between the reviewers have to be resolved in a subsequent discussion. Finally, if necessary, the authors of the original papers will also be contacted if further data is necessary for their interpretation.

Reviewers have to independently (i) rate internal quality of included studies dependent of the study design (ii) assess the quality and reporting of TDM components of the studies. To date, there are no standardized quality tools for studies specifically investigating TDM or concentration/effect relationships. Therefore, we adjusted the quality criteria in a recent review by Kloosterboer et al. on the concentration/effect relationship of psychotropic drugs in minors (11), which were modified from a previously published meta-analysis by Ulrich et al. for haloperidol (12). A detailed description of the individual items can be found in the Supplementary Material. If a study does not completely report or implement an item, that item is rated insufficient. The TDM quality score ranges from 0 to 10 [selection (scale 0–3), comparability (scale 0–2), and drug monitoring (scale 0–5)]. For the quality assessment of cohort studies and cross-sectional studies, an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (13) is used. The quality score ranges from 0 to 10 [selection (scale 0–4), comparability (scale 0–2), and outcome (scale 0–4)] for cohort studies and from 0 to 8 [selection (scale 0–4), comparability (scale 0–2), and outcome (scale 0–2)] for cross-sectional studies. Likewise, reviewers rate the quality of the relevant efficacy cohort of randomized controlled clinical trials separately using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (14). Any disagreements are resolved through discussion. Authors of the original papers will be contacted if further information is required.

For the study results to be applied in a generalized manner, it is important to have a representative sample, which reflects the target population of the resulting reference range. A study population only comprising of treatment-resistant patients or patients with side effects to another treatment does not reflect the general patient population and a resulting range is not transferable to “normal” patients. Likewise, a study population drawn from patients for whom genotyping has been demanded by the clinician will not reflect the target population. Patients 18 years and younger or 65 years and older should be compared with the average adult population. For some psychotropic drugs, ethnic variation in distribution in CYP expression patterns is relevant for the metabolism of the administered drug. This is especially important, if the main metabolite of the drug contributes to the pharmacologic action. A variation in the metabolite-to-parent compound ratio and thus, the sum of active and parent compound, may possibly influence clinical effects in these drugs. Since the evidence on this phenomenon is still very small, its clinical relevance should be revised for every substance individually. If an influence has been shown, studies must be evaluated in regard to the factor ethnicity. This holds also true for studies using variations in drug formulations or chemical forms (prodrugs). References ranges may not easily be transferred from originator products.

To ensure comparability between studies, patients should be selected patients should be selected according to psychiatric and associated classification systems [of which the latest versions are the 5th edition of the American Psychiatric Association's (15) and the 11th edition of the World Health Organization's (16), which comes into effect in 2022]. Ideally, a homogeneous sample of patients according to one main diagnosis should be investigated. With a heterogeneous sample, a sub-analysis per relevant category should be provided. Differences in reference ranges across, usually related but also across unrelated, diagnosis should be emphasized in the final review.

To avoid clinical effect bias, no drugs that potentially affect the treatment outcome should have been taken concomitantly during the study period. If detailed information on comedication was not provided, the study is rated as insufficient. The use of on-demand medication such as benzodiazepines or sleep medication must be considered adequate. Pre-medication should be registered as study characteristic and not be scored. For reviews about reference ranges of substances in which the active metabolite contributes to clinical efficacy and an altered metabolite to parent compound ratio might lead to a change in clinical efficacy, studies allowing concomitant drugs that interfere with the metabolism of the target drug should be identified.

The clinical status of a subject determines the amount of dose administered and thus the drug concentration. To avoid a possible reversal of a causal relationship resulting from such an effect, a study design with a fixed dose should be preferred over a design with a flexible dose (17). Flexible dosing is usually insufficient, since it may give rise to artificially negative correlations between concentrations and clinical effects (10).

An analytical method is considered valid if it accurately, precisely, selectively, sensitively, reproducibly, and stably measures the concentration of the substance (9). In general, chromatographic methods, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), are selective and sensitive measurement methods. Immunoassays are considered low specific. The lower detection limit of the chosen analytical method should allow drug concentration measurements below the lower limit of currently recommended therapeutic reference ranges. Double measurements of samples are preferred, but they are not performed in clinical routine practice.

The time of sample collection affects the blood concentration of the drug. Sampling should be performed at steady-state, preferably at trough level since TDM-guided pharmacotherapy usually relies on minimal drug concentration, if not indicated otherwise. In clinical routine, blood withdrawal in the morning, before the first dose has been recommended (12–16 or 24 h after last dose) (9). Inconsistent sampling time points introduce bias; however considerably less likely for substances with long half-lives than for those with short elimination half-lives. Drug concentration of substances with long elimination half-lives (e.g., fluoxetine and aripiprazole), extended-release and depot formulations remain relatively stable over the day (18) and allow sampling within 12–24 h after the last drug intake. Sampling times should be described in publications when reporting drug concentrations. It is generally assumed that the steady-state condition is reached after 5 times the half-life of a drug. Drug sampling before the steady-state is reached, however, may result in an underestimation of clinical efficacy. This also holds true for long-acting depot medication.

Correlations of measured serum concentrations with early response (e.g., after 1 week) is problematic, because of the well-described time lag between treatment initiation and onset of antidepressant/antipsychotic effects. The sampling schedule should include repeated sampling (at least two samples) in a patient over several weeks, ideally at different doses. In order to reflect a representative distribution of drug concentrations, a study's dose regimen should result in a sufficiently wide drug concentration range, with data of sub- and/or supratherapeutic drug concentrations.

Results must be reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline. The characteristics of all included studies (author/s, year, country, study design, intervention details, and study population details) must be displayed in a tabular summary.

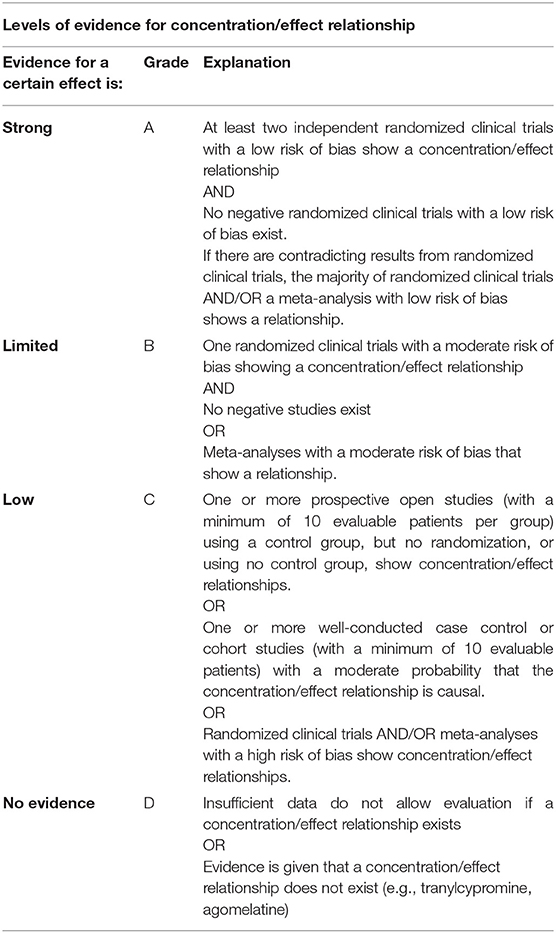

The strength of available evidence for that supports a concentration/response relationship or concentration/ side effect relationship for a drug will be reflected by the assignment of a certain level. Grading into levels of evidence will be performed following the recommendations of the WFSBP guidelines for clinical guideline development (19). (i) Prioritize and evaluate (risk-of-bias assessment) single RCTs: when sufficient RCTs exist that support a certain concentration/effect relationship and these are of high quality and do not contradict each other, this approach is preferred. (ii) Evaluate meta-analyses (risk-of-bias assessment): when there are at least three RCTs for one treatment and these are inconsistent—meaning that some studies show a difference to placebo and others do not—meta-analyses of high quality should be used. (iii) Evaluate systematic reviews without meta-analysis (risk-of-bias assessment). This source of evidence should only be used if no recommendations can be generated from (1) and (2). It is not recommended to base the evidence grading on non-systematic reviews. Levels of evidence relating to the published literature are documented in Table 2. If evidence is found to support the relationship between drug concentration and therapeutic response (level A, strong or level B, limited), a valid therapeutic reference range, at least the lower limit, is likely to be found by an evaluation of the available data. The overall quality of evidence is reported as “strong,” “limited,” “low,” or “no evidence.”

Table 2. Grading into levels of evidence for a concentration/effect relationship following the recommendations of the WFSBP guidelines for clinical guideline development.

Concentration data must be pooled in order to find mean concentration ranges across studies. The theoretically expected concentration range in a patient population is estimated using data from a reference sample of patients, preferentially without co-medication or pharmacogenetic abnormalities. The pooled concentration, daily dose and C/D have to be combined and calculated using random-effect and fixed-effect models based on the I2 statistic. The I2 statistic has to be used to examine to presence of substantial heterogeneity between studies, with I2-values > 50% indicating heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses might be appropriate to examine the impact of moderating factors on concentration, such as patient populations with differing CYP expression patterns, age, sex or concomitant medications. In the next step, ranges of blood concentrations from only responders to a drug are computed to obtain a preliminary responder reference range for the psychotropic drug. There is no consistent method for calculating these ranges. We propose the use of mean ± one standard deviation (SD) or interquartile ranges (25th−75th percentiles) of drug concentrations in the blood.

Our strategy, on how to search and grade TDM-related literature, aims at finding therapeutic reference ranges for psychotropic drugs that are objectively evaluated. Each drug has to be assigned to a level according to the strength of evidence which refers to the underlying concentration/effect relationship. Methodology that has been used to uncover clinical response of psychotropic drugs in relation to blood concentration, however, is highly prone to failure (20). Concentration/response relationships are not well-established for most psychotropic drugs. As a consequence, many published ranges must be regarded as preliminary. In addition, published studies strongly differ in design and quality; their critical evaluation, as described here, is mandatory. This protocol introduces a standard on how to identify and grade evidence underlying therapeutic reference ranges. The methodology may be extended to other drug classes, since the lack of evaluated therapeutic reference ranges is not restricted to TDM in psychiatry.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

XH developed the first draft of the protocol. CH and GG supervised the entire manuscript writing and contributed to the revision of the protocol. XL, KW, LE, and TR have contributed to the development of the search strategy and quality assessment criteria. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

CH has received speaker's fees from Otsuka. He is editor of PSIAC, a web-based platform analyzing pharmacokinetic and –dynamic drug interactions. The software is distributed by Springer Nature, Heidelberg, Germany. GG has served as a consultant for Allergan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Recordati, ROVI, Sage, and Takeda. He has served on the speakers' bureau of Gedeon Richter, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Recordati. He has received grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck and Saladax. He is co-founder and/or shareholder of Mind and Brain Institute GmbH, Brainfoods GmbH, OVID Health Systems GmbH and MIND Foundation gGmbH.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.787043/full#supplementary-material

1. Lloret-Linares C, Bellivier F, Haffen E, Aubry JM, Daali Y, Heron K. Markers of individual drug metabolism: towards the development of a personalized antidepressant prescription. Curr Drug Metab. (2015) 16:17–45. doi: 10.2174/138920021601150702160728

2. Gründer G, Hiemke C, Paulzen M, Veselinovic T, Vernaleken I. Therapeutic plasma concentrations of antidepressants and antipsychotics: lessons from PET imaging. Pharmacopsychiatry. (2011) 44:236–48. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286282

3. Cumming P, Abi-Dargham A, Gründer G. Molecular imaging of schizophrenia: neurochemical findings in a heterogeneous and evolving disorder. Behav Brain Res. (2021) 398:113004. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.113004

4. Eap CB, Gründer G, Baumann P, Ansermot N, Conca A, Corruble E. Tools for optimising pharmacotherapy in psychiatry (therapeutic drug monitoring, molecular brain imaging and pharmacogenetic tests): focus on antidepressants. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2021) 22:561–628. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2021.1878427

5. Cooney L, Loke YK, Golder S, Kirkham J, Jorgensen A, Sinha I. Overview of systematic reviews of therapeutic ranges: methodologies and recommendations for practice. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2017) 17:84. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0363-z

6. Baumann P, Hiemke C, Ulrich S, Eckermann G, Gaertner I, Gerlach M. The AGNP-TDM expert group consensus guidelines: therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry. Pharmacopsychiatry. (2004) 37:243–65. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832687

7. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, Conca A, Dietmaier O, Egberts K. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. (2011) 44:195–235. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286287

8. de Leon J. A critical commentary on the 2017 AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in neuropsychopharmacology. Pharmacopsychiatry. (2018) 51:63–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-117891

9. Hiemke C, Bergemann N, Clement HW, Conca A, Deckert J, Domschke K. Consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in neuropsychopharmacology: update 2017. Pharmacopsychiatry. (2018) 51:9–62. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-116492

10. Hiemke C. Concentration-effect relationships of psychoactive drugs and the problem to calculate therapeutic reference ranges. Ther Drug Monit. (2019) 41:174–9. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000582

11. Kloosterboer SM, Vierhout D, Stojanova J, Egberts KM, Gerlach M, Dieleman GC. Psychotropic drug concentrations and clinical outcomes in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2020) 19:873–90. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1770224

12. Ulrich S, Wurthmann C, Brosz M, Meyer FP. The relationship between serum concentration and therapeutic effect of haloperidol in patients with acute schizophrenia. Clin Pharmacokinet. (1998) 34:227–63. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199834030-00005

13. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Welch PJV, Losos M. The newcastle-ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Health Research Institute Web site 7. (2014).

14. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2019) 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

15. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

16. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 11th ed. Available online at: https://icd.who.int/ (accessed October 21 2021).

17. Ulrich S, Lauter J. Comprehensive survey of the relationship between serum concentration and therapeutic effect of amitriptyline in depression. Clin Pharmacokinet. (2002) 41:853–76. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241110-00004

18. Sheehan JJ, Reilly KR, Fu DJ, Alphs L. Comparison of the peak-to-trough fluctuation in plasma concentration of long-acting injectable antipsychotics and their oral equivalents. Innov Clin Neurosci. (2012) 9:17–23.

19. Hasan A, Bandelow B, Yatham LN, Berk M, Falkai P, Möller HJ, et al. WFSBP guideline task force chairs. WFSBP guidelines on how to grade treatment evidence for clinical guideline development. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 20:2–16. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2018.1557346

Keywords: psychotropic drugs, drug monitoring, therapeutic reference range, concentration/effect relationship, systematic review

Citation: Hart XM, Eichentopf L, Lense X, Riemer T, Wesner K, Hiemke C and Gründer G (2021) Therapeutic Reference Ranges for Psychotropic Drugs: A Protocol for Systematic Reviews. Front. Psychiatry 12:787043. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.787043

Received: 30 September 2021; Accepted: 26 October 2021;

Published: 24 November 2021.

Edited by:

Laura Mercolini, University of Bologna, ItalyReviewed by:

Lucie Bartova, Medical University of Vienna, AustriaCopyright © 2021 Hart, Eichentopf, Lense, Riemer, Wesner, Hiemke and Gründer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xenia M. Hart, eGVuaWEuaGFydEB6aS1tYW5uaGVpbS5kZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.