95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 12 January 2022

Sec. Addictive Disorders

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.779143

A correction has been applied to this article in:

Corrigendum: Exploration of the Role of Serine Proteinase Inhibitor A3 in Alcohol Dependence Using Gene Expression Omnibus Database

Background: Alcohol dependence is an overall health-related challenge; however, the specific mechanisms underlying alcohol dependence remain unclear. Serine proteinase inhibitor A3 (SERPINA3) plays crucial roles in multiple human diseases; however, its role in alcohol dependence clinical practice has not been confirmed.

Methods: We screened Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) expression profiles, and identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were generated using STRING and Cytoscape, and the key clustering module was identified using the MCODE plugin. SERPINA3-based target microRNA prediction was performed using online databases. Functional enrichment analysis was performed. Fifty-eight patients with alcohol dependence and 20 healthy controls were recruited. Clinical variables were collected and follow-up was conducted for 8 months for relapse.

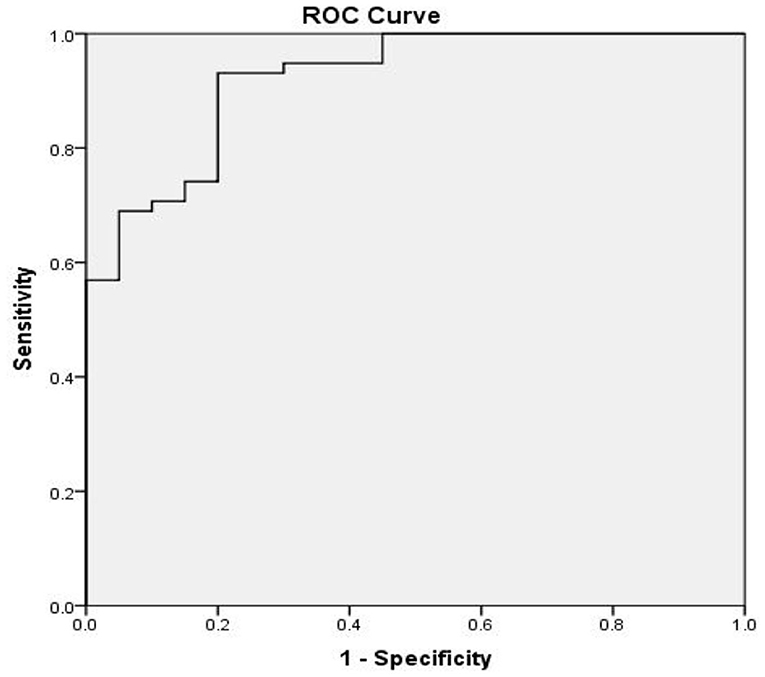

Results: SERPINA3 was identified as a DEG. ELANE and miR-137 were identified after PPI analysis. The enriched functions and pathways included acute inflammatory response, response to stress, immune response, and terpenoid backbone biosynthesis. SERPINA3 concentrations were significantly elevated in the alcohol dependence group than in healthy controls (P < 0.001). According to the median value of SERPINA3 expression level in alcohol dependence group, patients were divided into high SERPINA3 (≥2677.33 pg/ml, n = 29) and low SERPINA3 groups (<2677.33 pg/ml, n = 29). Binary logistic analysis indicated that IL-6 was statistically significant (P = 0.015) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis did not indicate any difference in event-free survival between patients with low and high SERPINA3 levels (P = 0.489) after 8 months of follow-up. Receiver characteristic curve analysis revealed that SERPINA3 had an area under the curve of 0.921 (P < 0.0001), with a sensitivity and specificity of 93.1 and 80.0%, respectively. Cox regression analysis revealed that aspartate transaminase level was a negative predictor of relapse (β = 0.003; hazard ratio = 1.003; P = 0.03).

Conclusions: SERPINA3 level was remarkably elevated in patients with alcohol dependence than healthy controls, indicating that SERPINA3 is correlated with alcohol dependence. However, SERPINA3 may not be a potential predictive marker of relapse with patients in alcohol dependence.

Alcohol dependence is associated with physiological and psychological effects, with alcohol abuse being the most common cause of many social issues, including domestic violence and other crimes. Several studies have shown that abnormal gene expression and polymorphism are strongly associated with alcohol dependence. Several intronic γ-aminobutyric acid β1 (GABA β1) subunit (GABR β1)single nucleotide polymorphisms that may directly influence alcohol dependence risk have been recently identified (1). DNA methylation of growth arrest specific five gene is implicated in alcohol use (2). In addition, carriers of the rs1789891 A allele reportedly consume more alcohol and have a higher risk of relapse than individuals that are homozygous for the C allele (3). However, there is currently no effective diagnostic and relapse test to evaluate alcohol dependence. The systemic molecular mechanisms of patients with alcohol dependence must be urgently explored to provide new, effective diagnostics and treatments.

Bioinformatics has become an essential tool in life science research, and plays an important role in studying the identification and functional annotation of human genes and proteins. In particular, in recent years, bioinformatics has played a pivotal role in the study of human diseases and related mechanisms, including gene expression regulation analysis, drug screening and targeting, and the formulation and validation of biological hypotheses, using the vast data resources available in public databases. However, the reliability of the results is challenging because the false-positive rate in independent microarray analysis remains high. To this end, we aimed to explore the underlying molecular mechanisms among patients with alcohol dependence using combined bioinformatics. In the present study, three alcohol-related gene expression omnibus (GEO) datasets were used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that may be associated with alcohol dependence. Functional enrichment analysis of these DEGs was then used to discover the underlying biological mechanisms of alcohol dependence. These results were verified using an independent cohort of patients with alcohol dependence and healthy controls. Our study findings could contribute toward developing a clinical diagnostic test for alcohol dependence, and uncovering new therapeutic targets to combat this disease.

We obtained data from three gene expression datasets: GSE29555 (4), GSE44456 (5), and GSE62699 (6) from the GEO database. The GSE29555 dataset contained 68 samples from alcohol-dependent patients and 60 from non-alcohol-dependent patients. GSE44456 included 19 samples from alcohol-dependent patients and 19 from non-alcohol-dependent patients. GSE62699 contained 18 samples from alcohol-dependent patients and 18 from non-alcohol-dependent patients.

GEO2R tool was utilized to identify the DEGs between the samples of patients with alcohol dependence and non-alcohol dependence. Probe sets lacking matched gene symbols, and the datasets that GEO2R could not analyze were removed from the analysis among 20 datasets. DEGs with |log FC (fold change)| ≥ 1 and Statistical significance was considered p < 0.05.

A protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of the DEGs was constructed using the STRING database (http://string-db.org; version 10.0), with a minimum interaction score cutoff of 0.4 (7). Cytoscape (version 3.7.2) was used for visualization of the interaction networks (8). The MCODE plug-in was used to construct key clustering modules (MCODE score > 5, degree cutoff = 2, node score cutoff = 0.2, max depth = 100, and k-score = 2).

Functional and pathway enrichment analyses of the DEGs were performed using DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) (9). Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed to associate functional keywords with the DEGs in the following categories: biological process (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC) (10).

To verify the hypothesis generated using the bioinformatics data, a cohort of 58 patients and 20 healthy controls was recruited from the Third People's Hospital of Huai'an. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was authorized and approved by the Harbin Medical University Ethics Committee and the Third People's Hospital Ethics Committee of Huai'an. All patients were diagnosed by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-V). Sociodemographic and clinical variables were collected for all participants, and Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) was used to test the cognitive function in patients with alcohol dependence.

All blood samples were obtained before 07:00 AM, when the patients were first admitted to the hospital and before any medication was given. The samples were immediately centrifuged at 3,000 g for 15 min at ambient temperature. The plasma supernatant was removed and stored at −80°C. The concentration of SERPINA3 in each plasma sample was assayed using an ELISA kit (SERPINA3 Human ELISA Kit, YanZun, Shanghai, China) as per the manufacturer's protocol. We also measured the levels of IL-6, which interacts with SERPINA3, using an ELISA kit (IL-6 Human ELISA Kit, YanZun, Shanghai, China).

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test normal distribution. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Student's t-test was used to analyze the continuous variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. Binary logistic analysis was performed to identify variables that were independently influenced by SERPINA3 levels. Multivariate linear regression analysis were used to determine the variables most closely related to SERPINA3 levels. Clinical events were systematically tracked for the entire cohort using post-discharge telephone interviews to document relapse. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and the area under the curve (AUC) were analyzed to test the diagnostic value of SERPINA3 for alcohol dependence. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to compare the time of relapse to SERPINA3 levels between the high and low SERPINA3 groups. Cox regression analysis was used to determine the risk factors affecting first-time relapse. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS-23 (IBM) and graphs were generated in Origin (Origin 2018 64Bit). Differences between the groups were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

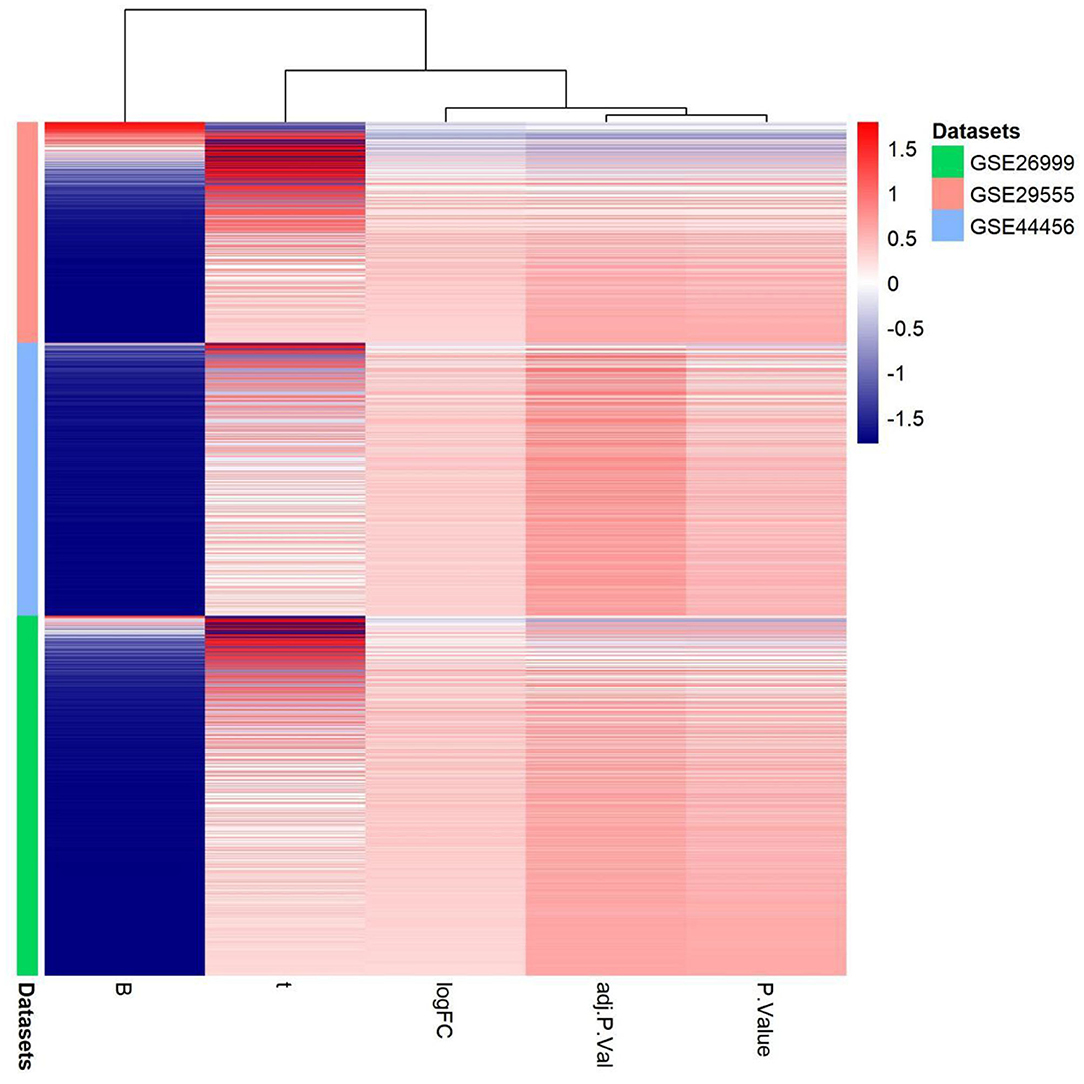

DEGs between patients with alcohol dependence and those without alcohol dependence were identified (4 in GSE29555, 3 in GSE44456, and 190 in GSE62699). One overlapping DEG was identified in all three datasets, and this DEG was upregulated in all three datasets (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Venn diagram showing DEGs between three microarray databases for genes associated with alcohol dependence. The three datasets have one overlapping gene, SERPINA3.

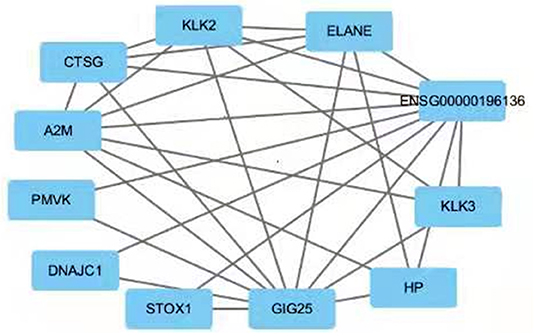

Since only a single common gene was identified, we generated a network of interacting proteins to augment the dataset (Figure 2). MCODE plug-in was used to analyze this network, and one clustering module was filtered out according to the chosen screening conditions. Clustering module 1 scored 6.857 and had 8 nodes and 24 edges (Figure 3). One gene, ELANE, was identified as the hub gene with degree ≥ 10.

Figure 2. PPI network for SERPINA3. The interacting genes were identified using the STRING database and visualized using Cytoscape.

MicroRNAs of the target gene were predicted from TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/), miRTarBase (https://maayanlab.cloud/Harmonizome/resource/MiRTarBase), miRWalk (mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/), miRcode (http://www.mircode.org), and miRDB (http://mirdb.org/miRDB/) databases. To narrow the range of the predicted miRNAs and reduce the false positive rate, miRNA-137, the intersection of miRNAs obtained from the five databases, was taken as the prediction result of the target genes (Figure 4).

The DEG were significantly enriched in the following biological processes: acute inflammatory response, defense response, neutrophil-mediated immunity, acute-phase response, negative regulation of protein metabolic process, negative regulation of chemokine biosynthetic response to external stimulus, positive regulation of immune response, immune response, and humoral immune response. The enriched MFs were: serine-type endopeptidase activity, and enzyme regulator activity. The enriched CCs were: extracellular space, secretory granules, and extracellular exosomes. Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis revealed that genes were enriched mainly in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (P = 0.022).

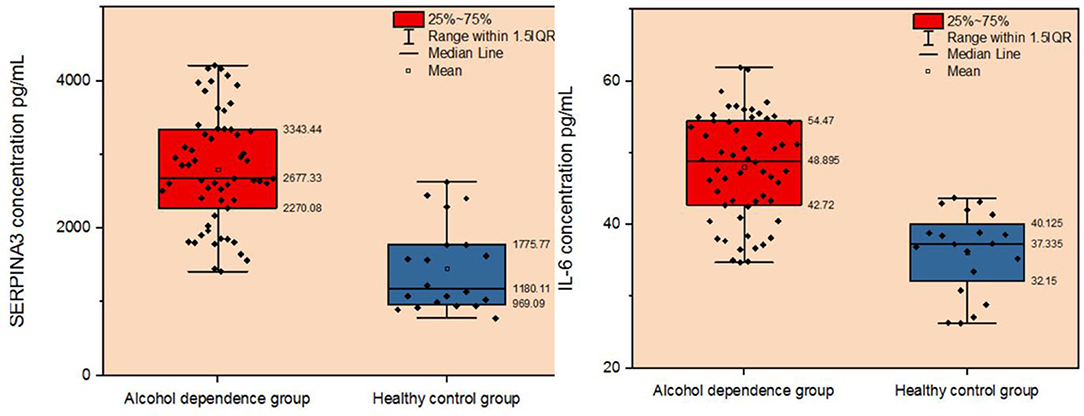

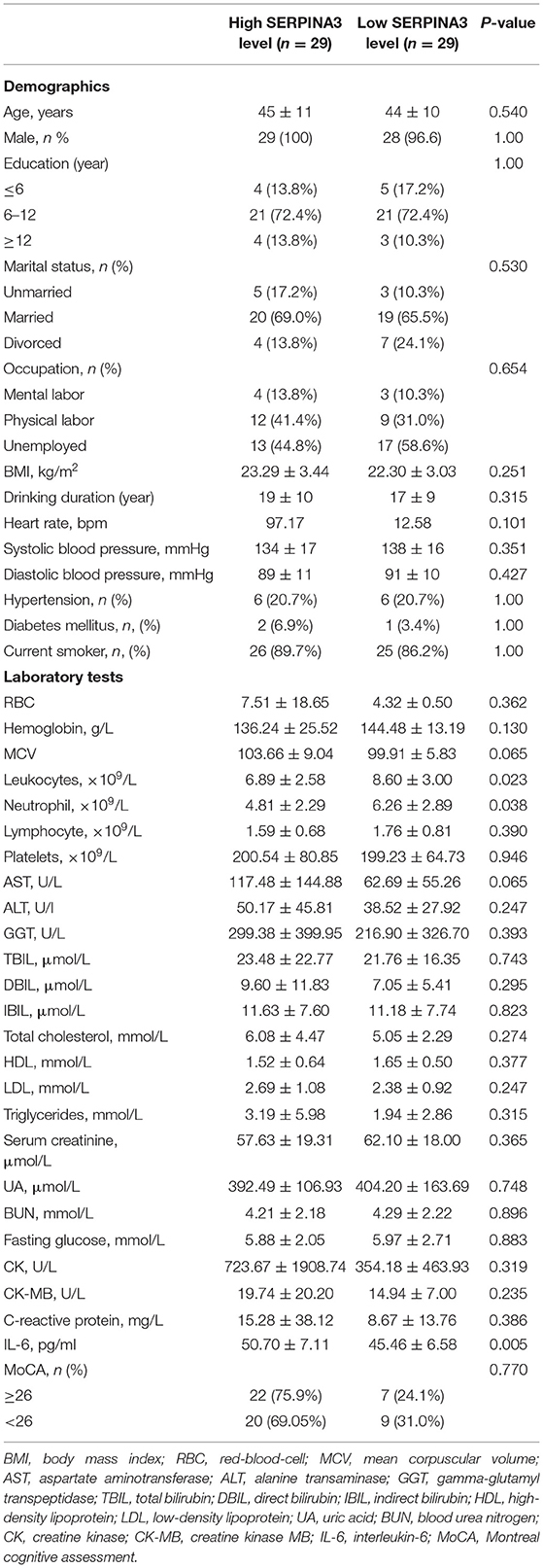

We recruited 58 individuals with alcohol dependence and 20 healthy controls to validate the hypothesis that SERPINA3 and IL-6 were dysregulated in individuals with alcohol dependence. ELISA analysis indicated that SERPINA3 and IL-6 concentrations were significantly elevated in patients with alcohol dependence than in healthy controls (P < 0.001) (Figure 5). The median SERPINA3 concentration in patients with alcohol dependence (n = 58) was 2677.33 pg/ml. According to the median level of SERPINA3 in this cohort, patients were divided into high SERPINA3 (≥2677.33 pg/ml, n = 29) and low SERPINA3 groups (<2677.33 pg/ml, n = 29). Table 1 shows the comparison of the baseline data between the two groups. Higher concentrations of SERPINA3 were associated with higher concentrations of IL-6 (P = 0.005). In contrast, higher SERPINA3 concentration was associated with lower leukocyte and neutrophil counts (P = 0.023 and P = 0.038, respectively). Binary logistic analysis indicated that IL-6 was statistically significant (P = 0.015) (Table 2).

Figure 5. Comparison of plasma SERPINA3 and IL-6 levels between patients with alcohol dependence and the healthy control group.

Table 1. Correlation between basic clinical information, laboratory tests, and SERPINA3 levels in the plasma of patients recruited for the study.

Plasma SERPINA3 levels correlated positively with IL-6 levels (r = 0.357, P = 0.006), whereas it correlated negatively with white blood cell (r = −0.442, P = 0.001) and neutrophil counts (r = −0.441, P = 0.001). Multivariate linear regression analysis revealed that IL-6 (standardized β = 0.299, p = 0.013) was an independent determinant of SERPINA3 levels (Table 3).

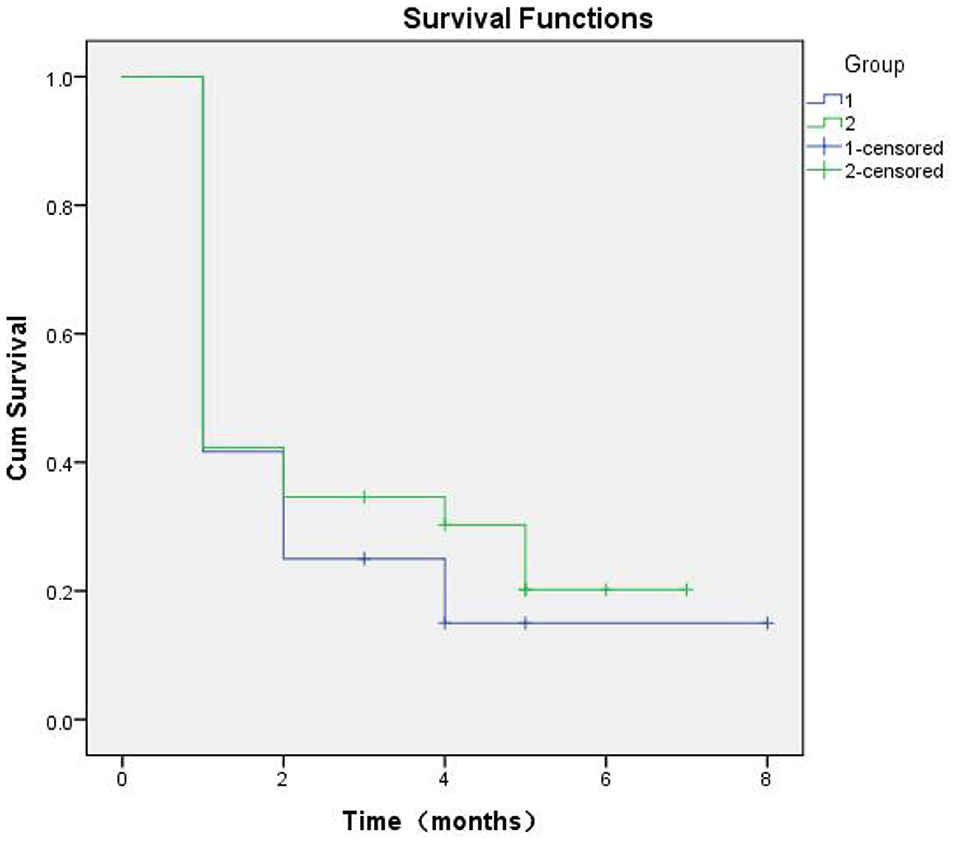

At 8 months of follow-up, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis did not reveal any difference in the event-free survival between patients with low vs. high SERPINA3 levels (P = 0.489) (Figure 6). ROC analysis was used to test the diagnostic value of SERPINA3, wherein it revealed that SERPINA3 had an AUC of 0.921(P < 0.0001), sensitivity of 93.1%, and specificity of 80.0% (Figure 7). Cox regression analysis showed that aspartate transaminase (AST) level was a negative predictor of relapse (β = 0.003, hazard ratio = 1.003, P = 0.03), whereas SERPINA3 level was not a predictor of relapse (Table 4).

Figure 6. Kaplan-Meier curves based on SERPINA3 levels in patients with alcohol dependence during follow-up of up to 8 months (P = 0.489).

Figure 7. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve based on SERPINA3 levels in patients with alcohol dependence. The area under the curve (AUC) for SERPINA3 was 0.921 (P < 0.0001), sensitivity was 93.1%, and specificity was 80.0%.

Alcohol dependence is a major public health issue associated with increasing incidence and mortality. The main etiology of alcohol dependence includes genetic and environmental factors, with genetic factors accounting for 40–60% (11). Most studies have been conducted on immune inflammation (12, 13), oxidative stress (14), metabolism (15), and apoptosis of brain cells (16) in patients with alcohol dependence. Despite ongoing studies on the pathology, causes, and risk factors of this disease, an appropriate treatment regimen has not yet been determined. Thus, the discovery and validation of the molecular mechanisms underpinning alcohol dependence are urgently needed. Microarray technology has increased our ability to explore genetic alterations in patients with alcohol dependence with several previous studies utilizing microarray data (17). In the present study, we identified a single upregulated DEG, SERPINA3, and one hub gene among the three microarray datasets associated with alcohol dependence. We also analyzed the gene expression patterns of three gene expression datasets: GSE29555, GSE44456, and GSE62699 in the Supplementary Material; (Figure 8) PPI analysis determined that genes associated with terpenoid backbone biosynthesis were associated with SERPINA3. Dysregulation of the terpenoid backbone biosynthesis plays a crucial role in mediating the effect of Panax notoginseng saponins (PNS) progression (18). Ginsenoside-Rg1, the main component of PNS, significantly suppresses inflammation by alleviating microglia and astrocyte activation (19). Microglia are critical modulators of alcohol neurotoxicity, and microglia may also be closely related to alcohol use disorders (20, 21). SERPINA3 is produced by brain astrocytes, which may be involved in synaptic remodeling and neuronal survival (22, 23). Therefore, it is possible that ginsenoside-Rg1 could be used to treat alcohol dependence by inhibiting glial cell activation. This promising area of research requires further investigation to evaluate the links between alcohol dependence and ginsenoside-Rg1.

Figure 8. Gene expression patterns in the three gene expression datasets: GSE29555, GSE44456, and GSE62699. Upregulation of genes is marked in red; downregulation of genes is marked in blue.

This is the first study to combine bioinformatics with clinical and genetic research on alcohol dependence. We are the first to demonstrate that plasma SERPINA3 is correlated with alcohol dependence. We additionally identified one hub gene, ELANE, and also conducted microRNA target prediction of SERPINA3.

SERPINA3 is a serine protease inhibitor superfamily member, which is involved in apoptotic cell death, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response (24). SERPINA3 is an acute phase protein that functions primarily through the regulation of neutrophil cathepsin G, leukocyte elastase, and mast cell chymotrypsin during inflammation, and it might be involved in synaptic remodeling and neuronal survival. The gene expression of SERPINA3 is stimulated by cytokines (25, 26). Leukocyte elastase G has a strong association with SERPINA3 (27). However, excessive stimulation of SERPINA3 can lead to tissue damage (28). During alcohol dependence, activated neutrophils could be partially responsible for the elevated levels of SERPINA3 observed in our study. A previous study demonstrated that SERPINA3 transcripts were remarkably expressed in a high inflammation cluster than in a low inflammation cluster (29). Similarly, in the present study, higher SERPINA3 levels were positively correlated with increased IL-6 level (P = 0.005), lower leukocyte count (P = 0.023), and lower neutrophil count (P = 0.038). This suggests that SERPINA3 is involved in inflammation during alcohol dependence. The levels of SERPINA3 were higher in patients with alcohol dependence, which is related to the NF-κB pathway (5, 30). Further research is needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms by which SERPINA3 levels are associated with alcohol dependence.

Previous studies indicated that peripheral SERPINA3 levels are not elevated in patients with dementia, other than those with Alzheimer's disease, and increase as dementia progresses (31). Our evidence was consistent with previous studies; we found no correlation between SERPINA3 levels and MoCA.

ELANE is involved in the inflammation response of leukocytes (32). Neutrophil elastase (NE), encoded by the ELANE gene, plays a bactericidal and proinflammatory role (33). When NE is released at high concentrations, it can mediate tissue destruction (34). After acute alcoholism, the total number of white blood cells and absolute value of neutrophils continue to increase, possibly leading to systemic or local inflammatory damage in the body (35). Therefore, we speculate that inhibitors of NE can be used to improve survival by attenuating the systemic inflammatory response; however, further validation is needed in this regard.

SERPINA3-based target microRNA prediction revealed miR-137. Reportedly, miR-137 plays a key regulator role in adult neurogenesis, presynaptic plasticity, and neuronal maturation (36). A previous study suggests that alcohol intake leads to synapse loss and anxiety-like behavior (20).

Furthermore, miR-137 is also essential for dendritic and synaptic growth. Loss of function of miR-137 leads to altered synaptic plasticity as well as anxiety-like behavior in mice (37). miR-137 overexpression or downregulation can impair brain function (38). Overexpression of miR-137 reduces the extent of brain tissue damage, and improves cell proliferation, and decreases the rate of apoptosis by inhibiting the expression of JAK1 and STAT1 proteins (39). Loss of miR-137 expression leads to abnormal neuronal morphology (40). These findings are in line with our hypothesis regarding the mechanism underlying alcohol dependence. However, the possible role of miR-137 in alcohol dependence has not been elucidated. We consider that miR-137 dysregulation may be associated with alcohol dependence; however, further studies are needed to validate our speculation.

Currently, the theraputic intervention is limited, including cognitive behavioral therapy and rehabilitation treatment approaches, Because of poor treatment compliance, with ~40–60% of patients relapse within 1 year of treatment (41). Therefore, after acute detoxification treatment, determining the causes of relapse and preventing relapse are crucial to treatment success. Previous studies have found that high GGT, AST, ALT, and MCV levels are strongly correlated with alcohol dependence relapse (42, 43). In the present study, AST was the main risk factor for relapse after inpatient withdrawal treatment. Therefore, patients with high-level AST should be paid more attention to prevent them from relapsing. However, we could not identify factors that influenced relapse, possibly because of the small sample size. Here, the baseline SERPINA3 levels did not differ significantly in patients with alcohol dependence between those who relapsed and those who did not; this suggests that SERPINA3 is not suitable for predicting relapse in alcohol dependence.

In conclusion, we identified that SERPINA3 is correlated with alcohol dependence. It is imperative to conduct further research to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and develop effective therapeutic strategies based on these findings. We speculate that there could be a relationship between ginsenoside-Rg1 and alcohol dependence. Future research should focus on determining the mechanism of action of ginsenoside-Rg1 on alcohol dependence. ELANE and miR-137 also need to be validated further as potential therapeutic targets in a larger cohort. However, the present study has several limitations. The cohort under study was small in size and blood samples were collected only at the time of admission; thus, there were no continuous data to track the change in the level of SERPINA3 during the follow-up.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Harbin Medical University Ethics Committee and the Third People's Hospital Ethics Committee of Huai'an. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

BZ and GW designed the study. CH, JZ, and YX collected the data. BZ performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. JH revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Our study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2018YFC1314400, 2018YFC1314402).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank Xin Wang and Xiao Yao Du for their expertise with the experiment. We would like to thank Editage for English language editing.

GEO, Gene expression omnibus; DEGs, Differentially expressed genes; AST, Aspartate transaminase; SERPINA3, Serine proteinase inhibitor A3.

1. McCabe WA, Way MJ, Ruparelia K, Knapp S, Ali MA, Anstee QM, et al. Genetic variation in GABRβ1 and the risk for developing alcohol dependence. Psychiatr Genet. (2017) 27:110–5. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0000000000000169

2. Lohoff FW, Roy A, Jung J, Longley M, Rosoff DB, Luo A. Epigenome-wide association study and multi-tissue replication of individuals with alcohol use disorder: evidence for abnormal glucocorticoid signaling pathway gene regulation. Mol Psychiatry. (2021) 26:2224–37. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0734-4

3. Bach P, Zois E, Vollstädt-Klein S, Kirsch M, Hoffmann S, Jorde A. Association of the alcohol dehydrogenase gene polymorphism rs1789891 with gray matter brain volume, alcohol consumption, alcohol craving and relapse risk. Addict Biol. (2019) 24:110–20. doi: 10.1111/adb.12571

4. Ponomarev I, Wang S, Zhang L, Harris RA, Mayfield RD. Gene coexpression networks in human brain identify epigenetic modifications in alcohol dependence. J Neurosci. (2012) 32:1884–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3136-11.2012

5. McClintick JN, Xuei X, Tischfield JA, Goate A, Foroud T, Wetherill L. Stress–response pathways are altered in the hippocampus of chronic alcoholics. Alcohol. (2013) 47:505–15. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.07.002

6. Mamdani M, Williamson V, McMichael G, Blevins T, Aliev F, Adkins A, et al. Integrating mRNA and miRNA weighted gene co-expression networks with eQTLs in the nucleus accumbens of subjects with alcohol dependence. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0137671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137671

7. Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A. STRING: protein–protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. (2013) 41:D808–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094

8. Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Ideker T. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. (2011) 27:431–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675

9. Huang DW, Sherman BT, Tan Q, Collins JR, Alvord WG, Roayaei J, et al. The DAVID gene functional classification tool: a novel biological module-centric algorithm to functionally analyze large gene lists. Genome Biol. (2007) 8:R183. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r183

10. Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. (2000) 25:25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556

11. Tawa EA, Hall SD, Lohoff FW. Overview of the genetics of alcohol use disorder. Alcohol. (2016) 51:507–14. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agw046

12. Cui C, Shurtleff D, Harris RA. Neuroimmune mechanisms of alcohol and drug addiction. Int Rev Neurobiol. (2014) 118:1–12. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801284-0.00001-4

13. Girard M, Malauzat D, Nubukpo P. Serum inflammatory molecules and markers of neuronal damage in alcohol-dependent subjects after withdrawal. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 20:76–90. doi: 10.1080/1562017.1349338

14. Dries SS, Seibert BS, Bastiani MF, Linden R, Perassolo MS. Evaluation of oxidative stress biomarkers and liver and renal functional parameters in patients during treatment a mental health unit to treat alcohol dependence. Drug Chem Toxicol. (2020) 0:1–7. doi: 10.1080./01480545.2020.1780251

15. Weinland C, Tanovska P, Kornhuber J, Mühle C, Lenz B. Serum lipids, leptin, and soluble leptin receptor in alcohol dependence: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2020) 209:107898. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107898

16. Rodriguez A, Chawla K, Umoh NA, Cousins VM, Ketegou A, Reddy MG. Alcohol and apoptosis: friends or foes? Biomolecules. (2015) 5:3193–203. doi: 10.3390/biom5043193

17. Li L, Lei Q, Zhang S, Kong L, Qin B. Screening and identification of key biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence from bioinformatic analysis. Oncol Rep. (2017) 38:2607–18. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5946

18. Liao P, Shi Y, Li Z, Chen Q, Xu TR, Cui X., et al. Impaired terpenoid backbone biosynthesis reduces saponin accumulation in panax notoginseng under Cd stress. Funct Plant Biol. (2019) 46:56–68. doi: 10.1071/FP18003

19. Fan C, Song Q, Wang P, Li Y, Yang M, Yu SY. Neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside-Rg1 against depression-like behaviors via suppressing glial activation, synaptic deficits, and neuronal apoptosis in rats. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:2889. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02889

20. Socodato R, Henriques JF, Portugal CC, Almeida TO, Tedim-Moreira J, Alves RL. Daily alcohol intake triggers aberrant synaptic pruning leading to synapse loss and anxiety-like behavior. Sci Signal. (2020) 13:eaba5754. doi: 10.1126./scisignal.aba5754

21. Warden AS, Wolfe SA, Khom S, Varodayan FP, Patel RR, Steinman MQ. Microglia control escalation of drinking in alcohol-dependent mice: genomic and synaptic drivers. Biol Psychiatry. (2020) 88:910–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.05.011

22. Lee TW, Tsang VWK, Loef EJ, Birch NP. Physiological and pathological functions of neuroserpin: Regulation of cellular responses through multiple mechanisms. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2017) 62:152–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.09.007

23. Pasternack JM, Abraham CR, Van Dyke BJ, Potter H, Younkin SG. Astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease gray MatterExpress α 1-antichymotrypsin mRNA. Am J Pathol. (1989) 135:827–34. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198905000-00087

24. Sánchez-Navarro A, González-Soria I, Caldiño-Bohn R, Bobadilla NA. An integrative view of serpins in health and disease: the contribution of SerpinA3. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2021) 320:C106–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00366.2020

25. Di Salvo TG, Yang K-C, Brittain E, Absi T, Maltais S, Hemnes A. Right ventricular myocardial biomarkers in human heart failure. J Card Fail. (2015) 21:398–411. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.02.005

26. Turnier JL, Brunner HI, Bennett M, Aleed A, Gulati G, Haffey WD. Discovery of SERPINA3 as a candidate urinary biomarker of lupus nephritis activity. Rheumatol. (2019) 58:321–30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key301

27. Beatty K, Bieth J, Travis J. Kinetics of association of serine proteinases with native and oxidized alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor and alpha-1-antichymotrypsin. J Biol Chem. (1980) 255:3931–4. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)85615-6

28. Baker C, Belbin O, Kalsheker N, Morgan K. SERPINA3 (aka alpha-1-antichymotrypsin). Front Biosci. (2007) 12:2821. doi: 10.2741/2275

29. Murphy CE, Kondo Y, Walker AK, Rothmond DA, Matsumoto M, Weickert CS. Regional, cellular and species difference of two key neuroinflammatory genes implicated in schizophrenia. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:826–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.05.055

30. Son YH, Jeong YT, Lee KA, Choi KH, Kim SM, Rhim BY. Roles of MAPK and NF-kappaB in interleukin-6 induction by lipopolysaccharide in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2008) 51:71–7. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31815bd23d

31. DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD, Wang X, Farlow M, Wisniewski S, Lopez OL, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluidalpha1-antichymotrypsin levels in Alzheimer's disease: correlation with cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. (2003) 53:81–90. doi: 10.1002/ana.10414

32. Gu W, Wen D, Lu H, Zhang A, Wang H, Du J., et al. MiR-608 exerts anti-inflammatory effects by targeting ELANE in monocytes. J Clin Immunol. (2019) 40:147–57. doi: 10.1007/s10875-019-00702-8

33. Ye Y, Carlsson G, Wondimu B, Fahlén A, Sjöberg J, Andersson M. Mutations in the ELANE gene are associated with development of periodontitis in patients with severe congenital neutropenia. J Clin Immunol. (2011) 31:936–45. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9572-0

34. Tamura D, Moore E, Partrick D, Johnson J, Offner P, Silliman C. Acute hypoxemia in humans enhances the neutrophil inflammatory response. Shock. (2002) 17:269–273. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200204000-00005

35. Tufkova SG, Yankov IV, Paskaleva DA. Clinical laboratory tests in some acute exogenous poisonings. Folia medica. (2017) 59:303–309. doi: 10.1515/folmed-2017-0058

36. Smrt RD, Szulwach KE, Pfeiffer RL, Li X, GuoW, Pathania M, et al. MicroRNA miR-137 regulates neuronal maturation by targeting ubiquitin ligase mind bomb-1. Stem Cells. (2010) 28:1060–70. doi: 10.1002/stem.431

37. Yan H, Sun X, Wang Z, Liu P, Mi T, Liu C, et al. MiR-137 deficiency causes anxiety-like behaviors in mice. Front Mol Neurosci. (2019) 12:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00260

38. Cheng Y, Wang ZM, Tan W, Wang X, Li Y, Bai B, et al. Partial loss of psychiatric risk gene Mir137 in mice causes repetitive behavior and impairs sociability and learning via increased Pde10a. Nat Neurosci. (2018) 21:1689–703. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0261-7

39. Zhang M, Ge DJ, Su Z, Qi B. miR-137alleviates focal cerebral ischemic injury in rats by regulating JAK1/STAT1 signaling pathway. Hum Exp Toxicol. (2020) 39:816–27. doi: 10.1177/0960327119897103

40. Jiang K, Ren C, Nair VD. MicroRNA-137 represses Klf4 and Tbx3 during differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. (2013) 11:1299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.09.001

41. Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Huang B, Ruan WJ. Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001-2002. Addiction. (2005) 100:281–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x

42. Flórez G, Saiz PA, García-Portilla P, De Cos FJ, Dapía S, Alvarez S, et al. Predictors of posttreatment drinking outcomes in patients with alcohol dependence. Eur Addict Res. (2015) 21:19–30. doi: 10.1159/000358194

Keywords: alcohol dependence, bioinformatics analysis, differently expressed genes, SERPINA3, relapse biomarkers

Citation: Zhang B, Wang G, Huang CB, Zhu JN, Xue Y and Hu J (2022) Exploration of the Role of Serine Proteinase Inhibitor A3 in Alcohol Dependence Using Gene Expression Omnibus Database. Front. Psychiatry 12:779143. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.779143

Received: 18 September 2021; Accepted: 02 December 2021;

Published: 12 January 2022.

Edited by:

Francesco Paolo Busardò, Marche Polytechnic University, ItalyReviewed by:

Mauro Ceccanti, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Zhang, Wang, Huang, Zhu, Xue and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jian Hu, aGoxMzkzNjE3MDgxOEAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.