94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 15 November 2021

Sec. Neuroimaging

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.777447

This article is part of the Research Topic Neural Bases of Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders and Their Neuromodulation Treatments View all 36 articles

Danlin Shen1

Danlin Shen1 Qing Li1

Qing Li1 Jianmei Liu2

Jianmei Liu2 Yi Liao3

Yi Liao3 Yuanyuan Li1

Yuanyuan Li1 Qiyong Gong4

Qiyong Gong4 Xiaoqi Huang4

Xiaoqi Huang4 Tao Li1,5

Tao Li1,5 Jing Li1

Jing Li1 Changjian Qiu1*

Changjian Qiu1* Junmei Hu6*

Junmei Hu6*Background: Schizophrenia is associated with a significant increase in the risk of violence, which constitutes a public health concern and contributes to stigma associated with mental illness. Although previous studies revealed structural and functional abnormalities in individuals with violent schizophrenia (VSZ), the neural basis of psychotic violence remains controversial.

Methods: In this study, high-resolution structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data were acquired from 18 individuals with VSZ, 23 individuals with non-VSZ (NSZ), and 22 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (HCs). Whole-brain voxel-based morphology and individual morphological covariance networks were analysed to reveal differences in gray matter volume (GMV) and individual morphological covariance network topology. Relationships among abnormal GMV, network topology, and clinical assessments were examined using correlation analyses.

Results: GMV in the hypothalamus gradually decreased from HCs and NSZ to VSZ and showed significant differences between all pairs of groups. Graph theory analyses revealed that morphological covariance networks of HCs, NSZ, and VSZ exhibited small worldness. Significant differences in network topology measures, including global efficiency, shortest path length, and nodal degree, were found. Furthermore, changes in GMV and network topology were closely related to clinical performance in the NSZ and VSZ groups.

Conclusions: These findings revealed the important role of local structural abnormalities of the hypothalamus and global network topological impairments in the neuropathology of NSZ and VSZ, providing new insight into the neural basis of and markers for VSZ and NSZ to facilitate future accurate clinical diagnosis and targeted treatment.

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a serious mental disorder affecting 1% of the world's population in terms of thinking, feeling, and behaviors that cause abnormal perceptions of reality (1). The link between SZ and violent offending has long been the subject of research with a significant impact on mental health policy. Patients with SZ have an elevated risk for aggression and violent behavior, which leads to fear and contributes to the major stigma of this disease (2). Although previous studies have reported that environmental factors, such as low socio-economic status and childhood trauma, may lead to violence in SZ (3–5), increasing evidence indicates that neurobiological factors may also play a key role in the increased risk of violence in individuals with SZ (6, 7). The origins of violent behavior in people with SZ are not yet sufficiently understood (8). Moreover, the management of aggression in SZ patients is a challenging clinical dilemma given that violence or aggressive behavior is heterogeneous in origin (8–10). Therefore, delineating the underlying neurobiological basis of violence in SZ may facilitate its management and effective therapy.

Non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides the opportunity to study brain structure and function in vivo. Widely used structural MRI (sMRI), diffusion MRI, and functional MRI enable investigations of brain morphology, white matter (WM) microstructure, and functional activities, respectively (11–17). In recent decades, mounting studies have demonstrated that brain function is not only fulfilled by a single area but also involves interactions across multiple distributed systems to form a complex brain network (18–22). Traditionally, brain networks were mapped using diffusion MRI for axonal connections or functional MRI for functional connectivities (23–28). Recently, using sMRI to map whole-brain morphological connectivity patterns by characterizing interregional morphological similarities was proposed due to its advantages of easy access, high signal-to-noise ratio, and robustness to artifacts (29–31). Unlike four-dimensional functional MRI, sMRI only contains three-dimensional location information. Early studies thus constructed the morphological covariance network at the population level by taking each individual subject as a time point to model time series of functional MRI (30, 32). A group of subjects can only obtain one connectivity matrix to reflect the group-level morphological covariance, ignoring individual variability. Recently, Wang et al. (33) developed an individual morphological covariance network method used for brain disease research (34, 35). Thus, individual morphological covariance networks with graph theory analysis may provide new insight into brain network organization patterns and improve the understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of violent SZ (VSZ) patients.

In the current study, we aimed to explore structural and topological differences in gray matter volume (GMV) and individual morphological covariance networks among healthy controls (HCs) and individuals with non-VSZ (NSZ) and VSZ. In addition, we evaluated the associations of changes in GMV and network topology with clinical variables.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University. A total of 18 VSZ, 23 NSZ, and 22 HCs participated in the present study. All the subjects were male and were matched based on age and education level among the three groups. All participants were right-handed, and written informed consent was provided and obtained. All subjects were recruited from the forensic psychiatry department of Preclinical Science and Forensic Medicine College of Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan. Psychiatric diagnoses were determined by two experienced psychiatrists using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (SCID-I/P), Chinese version. The inclusion criteria for VSZ were murder, attempted murder, and severe physical assault toward other people (including sexual assaults) based on the MacArthur criteria (36). These individuals committed serious violence with at least one fatal or near-fatal act of violence against their victims and were referred to forensic psychiatric examination for legal competence before court decisions. All participants were diagnosed with SZ before receiving any medical treatment. The exclusion criteria were (1) age <18 years or over 65 years; (2) other psychiatric co-morbidities; (3) any history of cardiovascular diseases, major physical illness, or neurological disorder; and (4) substance abuse or dependence. Brain MRI performed under the supervision of an experienced neuroradiologist showed no gross abnormalities.

Psychopathology was assessed using the Chinese version of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (37), which provides a total score and positive, negative, and general symptoms, and supplement scores. The Chinese version of the PANSS consists of the original PANSS plus three supplementary excitability items, including anger, difficulty in delay gratification, and affective liability, to measure the excitement dimension. The supplement scores were not added to the PANSS total score. The assessments were conducted by clinical psychiatrists who were professionally trained to conduct the PANSS interview and employ rating methods. Individual incidents of aggression were recorded using self-reporting criminology-characterized tables and modified overt aggression scale (MOAS) (38). The tables characterized by self-reported criminology include types of cases, attack targets, preparation of crime, criminal motivation, and self-protection. All of the information was collected based on criminal case files.

sMRI data were acquired using a 3-Tesla Siemens MRI system with an eight-channel phase-array head coil. Head motion was controlled using foam pads. Prior to scanning, participants were instructed to lie still with their eyes closed and not to fall asleep. High-resolution T1-weighted data were acquired using the following scan parameters: repetition time (TR) = 1,900 ms, echo time (TE) = 2.28 ms, flip angle = 9°, 176 sagittal slices with slice thickness = 1.0 mm, field of view = 240 × 240 mm2, and data matrix = 256 × 256.

The sMRI images were processed using the CAT12 toolbox in SPM12 software (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/wordpress/vbm/download/). Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis included the following steps. MRI images were first assessed to exclude artifacts or gross anatomical abnormalities and were reoriented to the anterior commissure. Then, the structural images were segmented into GM, WM, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Next, GM images were normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using the Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration using Exponentiated Lie algebra (DARTEL) normalization approach and were modulated to account for volume changes. Finally, the GM images were smoothed using a Gaussian kernel of 8-mm full-width at half maximum (FWHM) (32, 39), and whole-brain voxelwise one-way ANOVA with PANSS and disease duration as covariates was performed to identify differences in GMV among HCs, NSZ, and VSZ. The significance level was set as p < 0.05 using false discovery rate (FDR) correction and a minimum cluster size of >30. After identification of GMV differences, the mean GMV in brain areas with altered GMV in the HC, NSZ, and VSZ groups was calculated. Post-hoc two-sample t-tests were further used to identify between-group differences, and the significance was set at p < 0.05 with Bonferroni correction.

To explore brain network topology changes across different groups, individual morphological covariance networks were studied with GM images in the template space for each subject. The brain network includes network nodes and network edges. In this study, network nodes were defined with automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlases (40). Each cortical and subcortical subregion served as a node in the morphological covariance network.

After the nodes of the morphological network were defined, the edge was defined as the interregional similarity in the distribution of the regional GMV. The edge of the individual morphological covariance network was calculated as follows: kernel density estimation (KDE) was first used to estimate the probability density function of the extracted GMV values of each subregion in the AAL atlas, and the variation in the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence (KLD) was calculated to define the similarity of GM values between each pair of subregions. The similarities were taken as the edges of the morphological covariance network (33). Given that the AAL atlas segments the cortex and subcortex into 90 subregions, a 90 × 90 matrix was obtained for each subject. Finally, a binary network was generated for each subject for further analyses.

To explore network topology parameter differences among HCs, NSZ, and VSZ, graph theory-based network analyses were performed with sparsity values from 0.05 to 0.39 using steps of 0.02. First, small worldness was assessed for each morphological covariance network. If each morphological covariance network met the small-world property (normalized clustering coefficient >> 1, normalized characteristic path length ≈ 1, and small worldness > 1), the global and nodal topological parameters, including clustering coefficient (Cp), global efficiency (Eg), local efficiency (Eloc), shortest path length (Lp), assortativity, modularity, nodal degree, and nodal betweenness, were calculated. One-way ANOVA with PANSS and disease duration as covariates was first used to identify differences in network parameters among HCs, NSZ, and VSZ; and the significance level was set at p < 0.05. Post-hoc two-sample t-tests were further used to determine between-group differences corrected with the Bonferroni method with p < 0.05.

To explore whether GMV and network topology abnormalities were associated with illness duration, PANSS, and aggression, correlation analyses were conducted in NSZ and VSZ patients. The significance level was set at p < 0.05 corrected using the FDR method.

No significant differences in age (p = 0.53) or education (p = 0.38) were noted among the HC, NSZ, and VSZ groups as shown in Table 1. Patients with VSZ had longer disease duration (p = 0.0063), higher PANSS (p < 0.001), and higher aggression scores (p < 0.001) than NSZ patients (Table 1).

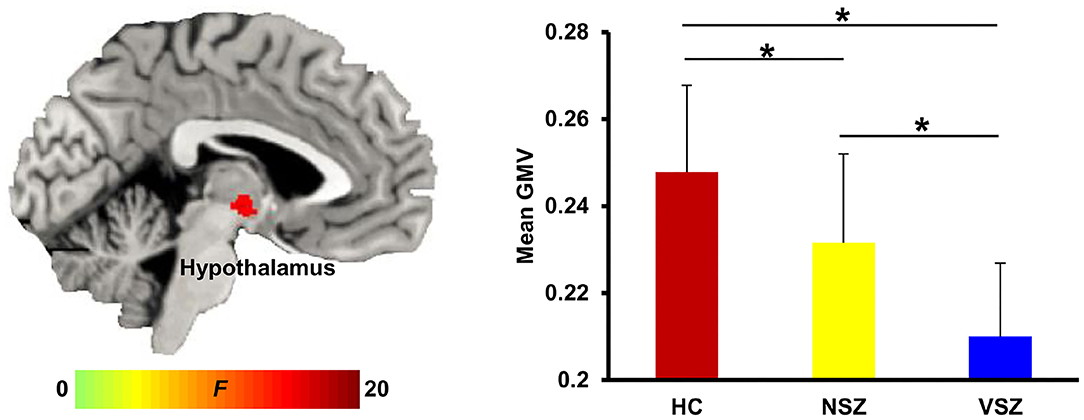

Abnormal GMV in the right hypothalamus (peak coordinate, x = 3, y = −11, z = −6) was noted among the HC, NSZ, and VSZ groups. Post-hoc two-sample t-tests found significantly lower GMVs in SZ patients compared with HCs and significantly lower GMVs in VSZ patients compared with NSZ patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Abnormal gray matter (GM) volume in the hypothalamus was found among healthy controls (HCs), nonviolent schizophrenia (NSZ) patients, and violent schizophrenia (VSZ) patients. A gradient decrease in GM volume from HCs to NSZ and VSZ was observed. *Significant difference with p < 0.05.

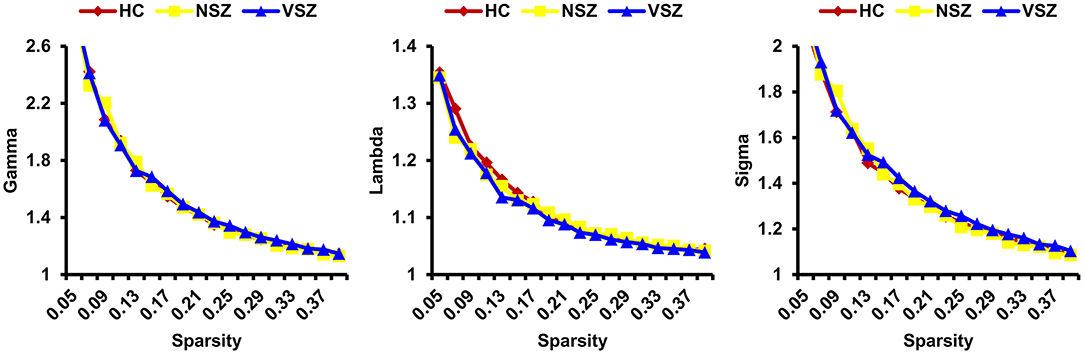

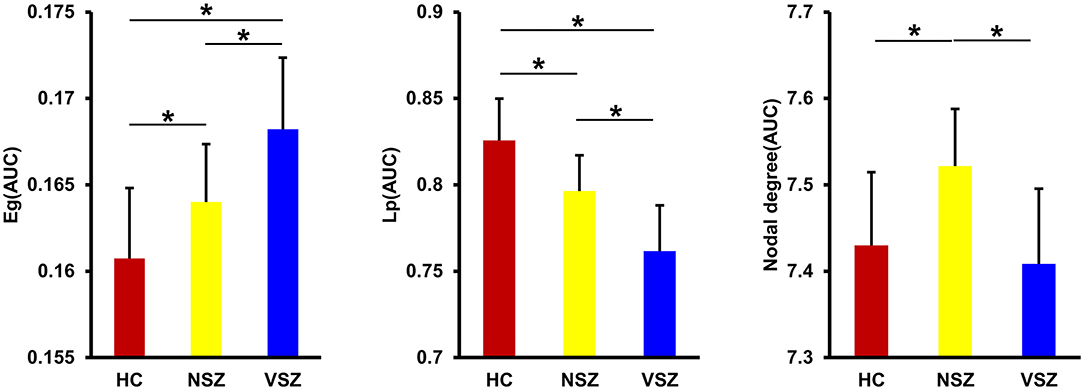

All the morphological covariance networks of HCs, NSZ, and VSZ showed small-worldness properties at sparsity values ranging from 0.05 to 0.39 (Figure 2). Abnormal network topological parameters, including Eg, Lp, and nodal degree, were found among the HC, NSZ, and VSZ groups (Figure 3). Both NSZ and VSZ patients showed significantly higher Eg than HCs; and VSZ individuals had significantly higher Eg than NSZ individuals. For Lp, both NSZ and VSZ patients exhibited significantly lower Lp than HCs, and VSZ exhibited significantly lower Lp than NSZ. The mean nodal degree in NSZ individuals was significantly greater than that observed in HCs and VSZ, but no significant difference was noted between HCs and VSZ. For other network topological parameters, including small worldness (Gamma, Lambda, and Sigma), Eloc, assortativity, modularity, Cp, and nodal betweenness, no significant differences were noted among HCs, NSZ, and VSZ (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2. All the HC, NSZ, and VSZ groups showed small-worldness properties of the individual morphological covariance network at sparsity values ranging from 0.05 to 0.39. HC, healthy control; NSZ, nonviolent schizophrenia; VSZ, violent schizophrenia.

Figure 3. Significant differences in global efficiency (Eg), shortest path length (Lp), and nodal degree were found among the HC, NSZ, and VSZ groups. A gradient increase in Eg and a gradient decrease in Lp from HCs to NSZ and VSZ were found. NSZ had a significantly higher nodal degree than both HCs and VSZ. * Significant difference with p < 0.05. HC, healthy control; NSZ, nonviolent schizophrenia; VSZ, violent schizophrenia.

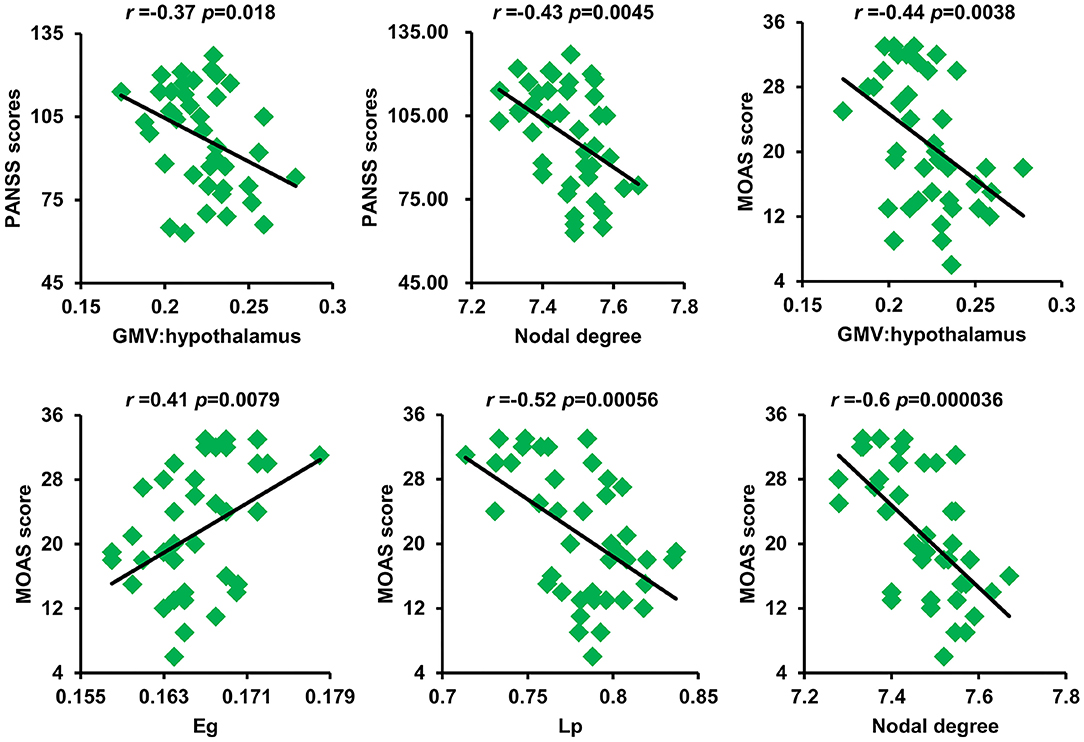

As shown in Figure 4, after correction for multiple comparisons, GMV of the hypothalamus and nodal degree showed significantly negative correlations with PANSS scores. The GMV of the hypothalamus, Lp, and nodal degree showed significantly negative correlations with aggression scores, whereas Eg exhibited a significantly positive correlation with aggression scores.

Figure 4. Significant correlations between GM volume of the hypothalamus and nodal degree and PANSS scores as well as between GM volume of the hypothalamus and Eg, Lp, nodal degree, and MOAS scores were found. GM, gray matter; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; Eg, global efficiency; Lp, shortest path length; MOAS, modified overt aggression scale.

In the current study, we revealed alterations in GMV and disrupted network topology in SZ patients with and without violence using voxel-based morphology and novel individual morphological covariance network analyses. Significantly decreased GMV in the hypothalamus and significantly disrupted global efficiency, short path length, and nodal degree were found in the NSZ and VSZ groups. Moreover, these changed GMVs and network topologies were significantly associated with clinical characteristics. These findings highlighted the important role of the hypothalamus in SZ patients with and without violence and deepened our understanding of the neuropathology of SZ and violence in SZ from a network perspective.

The hypothalamus is the control center for many autonomic functions of the peripheral nervous system and plays a vital role in maintaining homeostasis (41–43). As a part of the limbic system, the hypothalamus also influences various emotional responses (44). Many recent studies have demonstrated that the hypothalamus is important for circadian control aggression in both humans and animals (45–47). Decreased hypothalamus volume has been reported in patients with SZ (48–50). The decreased GMV in the hypothalamus supported our finding of decreased GMV in NSZ patients compared with HCs. However, few studies have reported abnormal GMV in the hypothalamus in SZ patients with aggression. Only one study by Schiffer et al. (51) found increased GMV in the hypothalamus in patients with SZ with conduct disorder, which is associated with violent behavior. In our study, we found decreased GMV in individuals with VSZ. The difference may result from different subtypes of VSZ, suggesting that different subtypes of VSZ may have distinct neural circuits. Moreover, we found that the GMV gradually decreased from HCs to NSZ and VSZ and was significantly correlated with PANSS and aggression scores in patients. These findings indicate that abnormal GMV of the hypothalamus may be an intrinsic biomarker to distinguish individuals with SZ from healthy individuals and to differentiate individuals with VSZ and NSZ.

The human brain is conceptualized as a complex network structured to optimize the interplay between segregation and integration of functionally specialized subsystems (19, 52). Many previous studies have utilized diffusion MRI or functional MRI to map anatomical or functional brain networks to explore network topological abnormalities in SZ (53–57). By measuring across-subject covariance in morphological measures, such as cortical thickness (29), gyrification (58), and GMVs (31, 59), structural network topological attributes were also studied in SZ. Although the GMV covariance network has been analyzed in SZ, all previous studies use population-level data to construct only one single connectivity network across all subjects, which cannot account for individual network topology. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to map the individual morphological covariance network to investigate abnormal network topology in VSZ and NSZ. We found gradually increased global efficiency and gradually decreased shortest path length from HCs to NSZ and VSZ. We also found an increased mean nodal degree in NSZ individuals compared with both HC and VSZ individuals. The findings in our study were supported by previous complex brain network analyses in SZ (54, 56, 60). All the evidence suggested higher information processing efficiency in NSZ and VSZ individuals compared with HCs. Our results together with previous findings may support the “hyperconnectivity” hypothesis of SZ (61–63). In addition, abnormal global efficiency, shortest path length, and nodal degree were significantly correlated with PANSS and aggression scores. Thus, global efficiency and shortest path length may serve as biomarkers to distinguish individuals with VSZ and NSZ, whereas nodal degree may be a specific neurobiomarker for NSZ.

The current study also has several limitations. First, in our study, the sample size was limited, and all the subjects were male. These results need to be interpreted with caution; thus, the findings in our study also require further validation. Second, longitudinal studies are warranted to better reveal the neuropathology of NSZ and VSZ using multimodal MRI data and to extend the findings in further studies.

In conclusion, our study found a gradual decrease in GMV in the hypothalamus and disrupted global topological properties, including global efficiency, shortest path length, and nodal degree, in individuals with VSZ and NSZ. In addition, we found that abnormal GMV and network topological properties were significant clinical measures. These findings highlight the important roles of the hypothalamus in individuals with VSZ and NSZ and provide neural biomarkers to distinguish SZ from healthy subjects and to differentiate subtypes of SZ.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.777447/full#supplementary-material

1. Tang J, Liao Y, Zhou B, Tan C, Liu W, Wang D, et al. Decrease in temporal gyrus gray matter volume in first-episode, early onset schizophrenia: an MRI study. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e40247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040247

2. Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, Geddes JR, Grann M. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120

3. Weiss EM. Neuroimaging and neurocognitive correlates of aggression and violence in schizophrenia. Scientifica. (2012) 2012:158646. doi: 10.6064/2012/158646

4. Fazel S, Långström N, Hjern A, Grann M, Lichtenstein P. Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. JAMA. (2009) 301:2016–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.675

5. van Dongen J, Buck N, Van Marle H. Unravelling offending in schizophrenia: factors characterising subgroups of offenders. Crim Behav Ment Health. (2015) 25:88–98. doi: 10.1002/cbm.1910

6. Rosell DR, Siever LJ. The neurobiology of aggression and violence. CNS Spectr. (2015) 20:254–79. doi: 10.1017/S109285291500019X

7. Fleischman A, Werbeloff N, Yoffe R, Davidson M, Weiser M. Schizophrenia and violent crime: a population-based study. Psychol Med. (2014) 44:3051–7. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000695

8. Sonnweber M, Lau S, Kirchebner J. Violent and non-violent offending in patients with schizophrenia: Exploring influences and differences via machine learning. Compr Psychiatry. (2021) 107:152238. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152238

9. Volavka J, Citrome L. Pathways to aggression in schizophrenia affect results of treatment. Schizophr Bull. (2011) 37:921–9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr041

10. Rubinov M, Bullmore E. Schizophrenia and abnormal brain network hubs. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2013) 15:339–49. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.3/mrubinov

11. Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2007) 8:700–11. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201

12. Symms M, Jäger HR, Schmierer K, Yousry TA A. review of structural magnetic resonance neuroimaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2004) 75:1235–44. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.032714

13. Mori S, Zhang J. Principles of diffusion tensor imaging and its applications to basic neuroscience research. Neuron. (2006) 51:527–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.012

14. Wang J, Feng X, Wu J, Xie S, Li L, Xu L, et al. Alterations of gray matter volume and white matter integrity in maternal deprivation monkeys. Neuroscience. (2018) 384:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.05.020

15. Wang J, Becker B, Wang L, Li H, Zhao X, Jiang T. Corresponding anatomical and coactivation architecture of the human precuneus showing similar connectivity patterns with macaques. Neuroimage. (2019) 200:562–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.07.001

16. Wang J, Yang Y, Zhao X, Zuo Z, Tan L-H. Evolutional and developmental anatomical architecture of the left inferior frontal gyrus. NeuroImage. (2020) 20:117268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117268

17. Wang J, Fan L, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Jiang D, Zhang Y, et al. Tractography-based parcellation of the human left inferior parietal lobule. Neuroimage. (2012) 63:641–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.045

18. Sporns O, Tononi G, Kotter R. The human connectome: a structural description of the human brain. PLoS Comput Biol. (2005) 1:e42. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010042

19. Bassett DS, Bullmore E. Small-world brain networks. Neuroscientist. (2006) 12:512–23. doi: 10.1177/1073858406293182

20. Bullmore E, Sporns O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2009) 10:186–98. doi: 10.1038/nrn2575

21. Wang J, Xie S, Guo X, Becker B, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB, et al. correspondent functional topography of the human left inferior parietal lobule at rest and under task revealed using resting-state fmri and coactivation based parcellation. Hum Brain Mapp. (2017) 38:1659–75. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23488

22. Wang J, Yang Y, Fan L, Xu J, Li C, Liu Y, et al. Convergent functional architecture of the superior parietal lobule unraveled with multimodal neuroimaging approaches. Hum Brain Mapp. (2015) 36:238–57. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22626

23. Gong G, He Y, Concha L, Lebel C, Gross DW, Evans AC, et al. Mapping anatomical connectivity patterns of human cerebral cortex using in vivo diffusion tensor imaging tractography. Cerebral cortex. (2009) 19:524–36. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn102

24. Gong G, Rosa-Neto P, Carbonell F, Chen ZJ, He Y, Evans AC. Age- and gender-related differences in the cortical anatomical network. J Neurosci. (2009) 29:15684–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2308-09.2009

25. Hagmann P, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Meuli R, Honey CJ, Wedeen VJ, et al. Mapping the structural core of human cerebral cortex. PLoS Biol. (2008) 6:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060159

26. Achard S, Bullmore E. Efficiency and cost of economical brain functional networks. PLoS Comput Biol. (2007) 3:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030017

27. Wang J, Wang Z, Zhang H, Feng S, Lu Y, Wang S, et al. White matter structural and network topological changes underlying the behavioral phenotype of MECP2 mutant monkeys. Cerebral cortex. (2021) 11:66. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhab166

28. Wang J, Zuo Z, Xie S, Miao Y, Ma Y, Zhao X, et al. Parcellation of macaque cortex with anatomical connectivity profiles. Brain Topogr. (2018) 31:161–73. doi: 10.1007/s10548-017-0576-9

29. Zhang Y, Lin L, Lin CP, Zhou Y, Chou KH, Lo CY, et al. Abnormal topological organization of structural brain networks in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2012) 141:109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.021

30. He Y, Chen ZJ, Evans AC. Small-world anatomical networks in the human brain revealed by cortical thickness from MRI. Cerebral cortex. (2007) 17:2407–19. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl149

31. Bassett DS, Bullmore E, Verchinski BA, Mattay VS, Weinberger DR, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Hierarchical organization of human cortical networks in health and schizophrenia. J Neurosci. (2008) 28:9239–48. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1929-08.2008

32. Wu H, Sun H, Wang C, Yu L, Li Y, Peng H, et al. Abnormalities in the structural covariance of emotion regulation networks in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. (2017) 84:237–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.001

33. Wang H, Jin X, Zhang Y, Wang J. Single-subject morphological brain networks: connectivity mapping, topological characterization and test–retest reliability. Brain Behav. (2016) 6:e00448. doi: 10.1002/brb3.448

34. Gao J, Chen M, Li Y, Gao Y, Li Y, Cai S, et al. Multisite autism spectrum disorder classification using convolutional neural network classifier and individual morphological brain networks. Front Neurosci. (2021) 14:629630. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.629630

35. Li X, Lei D, Niu R, Li L, Suo X, Li W, et al. Disruption of gray matter morphological networks in patients with paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia. Hum Brain Mapp. (2021) 42:398–411. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25230

36. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Mulvey EP, Silver E, et al. Developing a clinically useful actuarial tool for assessing violence risk. Br J Psychiatry. (2000) 176:312–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.312

37. Nelson HE A. modified card sorting test sensitive to frontal lobe defects. Cortex. (1976) 12:313–24. doi: 10.1016/S0010-9452(76)80035-4

38. Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, Endicott J, Williams D. The overt aggression scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. Am J Psychiatry. (1986) 143:35–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.1.35

39. Wang J, Wei Q, Bai T, Zhou X, Sun H, Becker B, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy selectively enhanced feedforward connectivity from fusiform face area to amygdala in major depressive disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. (2017) 12:1983–92. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsx100

40. Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. (2002) 15:273–89. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978

41. Pop MG, Crivii C, Opincariu I. Anatomy and Function of the Hypothalamus: Hypothalamus in Health and Diseases (2018).

42. Toni R, Malaguti A, Benfenati F, Martini L. The human hypothalamus: a morpho-functional perspective. J Endocrinol Investigat. (2004) 27(6 Suppl):73–94.

43. Lechan RM, Toni R. “functional anatomy of the hypothalamus and pituitary,” In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, et al. editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth MA: © 2000-2021, MDText.com, Inc. (2000).

44. Kullmann S, Heni M, Linder K, Zipfel S, Häring HU, Veit R, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity of the human hypothalamus. Hum Brain Mapp. (2014) 35:6088–96. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22607

45. Todd WD, Fenselau H, Wang JL, Zhang R, Machado NL, Venner A, et al. A hypothalamic circuit for the circadian control of aggression. Nat Neurosci. (2018) 21:717–24.

46. Hashikawa Y, Hashikawa K, Falkner AL, Lin D. Ventromedial hypothalamus and the generation of aggression. Front Syst Neurosci. (2017) 11:94. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2017.00094

47. Gouveia FV, Hamani C, Fonoff ET, Brentani H, Alho EJL, de Morais RMCB, et al. Amygdala and hypothalamus: historical overview with focus on aggression. Neurosurgery. (2019) 85:11–30. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy635

48. Tognin S, Rambaldelli G, Perlini C, Bellani M, Marinelli V, Zoccatelli G, et al. Enlarged hypothalamic volumes in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. (2012) 204:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.10.006

49. Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Makris N, Ahern T, O'Brien LM, Caviness VS, et al. Hypothalamic abnormalities in schizophrenia: sex effects and genetic vulnerability. Biological Psychiatry. (2007) 61:935–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.027

50. Koolschijn PCMP, van Haren NEM, Hulshoff Pol HE, Kahn RS. Hypothalamus volume in twin pairs discordant for schizophrenia. Euro Neuropsychopharmacol. (2008) 18:312–5. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.12.004

51. Schiffer B, Leygraf N, Müller BW, Scherbaum N, Forsting M, Wiltfang J, et al. Structural brain alterations associated with schizophrenia preceded by conduct disorder: a common and distinct subtype of schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. (2013) 39:1115–28. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs115

52. Tononi G, Sporns O, Edelman GM A. measure for brain complexity: relating functional segregation and integration in the nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (1994) 91:5033–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5033

53. Shon S-H, Yoon W, Kim H, Joo SW, Kim Y, Lee J. Deterioration in global organization of structural brain networks in schizophrenia: a diffusion MRI tractography study. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9(272). doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00272

54. Lynall ME, Bassett DS, Kerwin R, McKenna PJ, Kitzbichler M, Muller U, et al. Functional connectivity and brain networks in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. (2010) 30:9477–87. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0333-10.2010

55. van den Heuvel MP, Fornito A. Brain networks in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol Rev. (2014) 24:32–48. doi: 10.1007/s11065-014-9248-7

56. Liu Y, Liang M, Zhou Y, He Y, Hao Y, Song M, et al. Disrupted small-world networks in schizophrenia. Brain : J Neurol. (2008) 131:945–61. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn018

57. Wang Q, Su TP, Zhou Y, Chou KH, Chen IY, Jiang T, et al. Anatomical insights into disrupted small-world networks in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. (2012) 59:1085–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.035

58. Palaniyappan L, Park B, Balain V, Dangi R, Liddle P. Abnormalities in structural covariance of cortical gyrification in schizophrenia. Brain Struct Funct. (2015) 220:2059–71. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0772-2

59. Zhou HY, Shi LJ, Shen YM, Fang YM, He YQ, Li HB, et al. Altered topographical organization of grey matter structural network in early-onset schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. (2021) 316:111344. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2021.111344

60. Lo CY, Su TW, Huang CC, Hung CC, Chen WL, Lan TH, et al. Randomization and resilience of brain functional networks as systems-level endophenotypes of schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2015) 112:9123–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502052112

61. Anticevic A, Hu X, Xiao Y, Hu J, Li F, Bi F, et al. Early-course unmedicated schizophrenia patients exhibit elevated prefrontal connectivity associated with longitudinal change. J. Neurosci. (2015) 35:267–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2310-14.2015

62. Marsman A, van den Heuvel MP, Klomp DW, Kahn RS, Luijten PR, Hulshoff Pol HE. Glutamate in schizophrenia: a focused review and meta-analysis of H-MRS studies. Schizophr Bull. (2013) 39:120–9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr069

Keywords: individual morphological covariance network, graph theory, schizophrenia, violent, gray matter volume

Citation: Shen D, Li Q, Liu J, Liao Y, Li Y, Gong Q, Huang X, Li T, Li J, Qiu C and Hu J (2021) The Deficits of Individual Morphological Covariance Network Architecture in Schizophrenia Patients With and Without Violence. Front. Psychiatry 12:777447. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.777447

Received: 15 September 2021; Accepted: 18 October 2021;

Published: 15 November 2021.

Edited by:

Jiaojian Wang, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, ChinaReviewed by:

Fengmei Lu, Chengdu No.4 People's Hospital, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Shen, Li, Liu, Liao, Li, Gong, Huang, Li, Li, Qiu and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Changjian Qiu, cWl1Y2hhbmdqaWFuMThAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Junmei Hu, aHVqdW5tZWlAc2N1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.