- 1School of Rural Health, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2Eastern Health, Mental Health Program, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3Division Mental Health Services, Akershus University Hospital, Lørenskog, Norway

- 4Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Department of Health, Social and Welfare Studies, University of South-Eastern Norway, Drammen, Norway

- 5The Bouverie Centre, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 6Emerging Minds, Hilton, SA, Australia

Background: Translating evidence-based practice to routine care is known to take significant time and effort. While many evidenced-based family-focused practices have been developed and piloted in the last 30 years, there is little evidence of sustained practice in Adult Mental Health Services. Moreover, many barriers have been identified at both the practitioner and organizational level, however sustainability of practice change is little understood. What is clear, is that sustained use of a new practice is dependent on more than individual practitioners' practice.

Design and Method: Drawing on research on sustaining Let's Talk about Children in adult mental health services and in the field of implementation science, this article proposes a model for sustaining family focused practice in adult mental health services.

Sustainability Model for Family-Focused Practice: An operational model developed from key elements for sustaining Let's Talk about Children identifies six action points for Adult Mental Health Services and their contexts to support the sustainability of family-focused practices. The model aims to support Services to take action in the complexity of real-world sustainability, providing action points for engaging with service users and practitioners, aligning intra-organizational activities, and the wider context.

Conclusion: The model for sustaining family-focused practice draws attention to the importance of sustainability in this field. It provides a practical framework for program developers, implementers, adult mental health services and policy-makers to consider both the components that support the sustainability and their interconnection. The model could be built on to develop implementation guides and measures to support its application.

Introduction

Research in the past 30 years has explored the impact of a parent's mental ill-health on family life, raising awareness of the importance of family-focused practices for parents and their children (1–6). Such work in mental health services identifies a dual focus (i) improving the outcome for the person with the mental illness and (ii) reducing distress in family members while building their resilience and well-being (7–9). In Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS), family-focused practices encompass approaches, programs, interventions, models and frameworks that acknowledge the whole family context of the person receiving services (2, 10). These take into account the relational nature of recovery and therefore attend to the person's parenting role and family relationships and provide support to the parent in the context of their children and family, while also attend to the intergenerational mental health needs (10–12). Components of effective interventions include psychoeducation directed at both parents and children, adapting parenting behavior through increasing parent agency and skill building, and improving family communication particularly about mental illness (13).

There is now established evidence that these family-focused practices have an impact on supporting the parent in their parenting role and their mental health recovery (10, 14–17) and on protecting children and promoting their resilience (18–21). There are now many evidence-based family-focused practices or programs and documentation of ongoing delivery of programs (22–24). There is, however, little evidence of the use family-focused practices in routine care within AMHS (25–30).

To understand the lack of use of evidence-based family-focused practice in AMHS, research efforts have explored barriers at the practitioner and organization level. Inadequate family-focused training has been identified at the practitioner level, as has a lack of the necessary knowledge, skills and confidence in family-focused practice, limiting their ability to identify and support the parenting role of their clients while also holding their clients' children in mind (31–39). These barriers are reinforced by organizational contexts that do not routinely identify their client's parental status (29, 40–42) and are funded to work with individuals within a biomedical professional-centered approach that is focused on treatment in acute episodic care (10, 11, 20, 43). The formalized, centralized organizational structures common in AMHS are also known to foster the continuation of existing cultures, making innovation and change more difficult (44). These shape the work and the workforce to make it difficult to prioritize working with whole families with the preventive and early intervention approach inherent in family-focused practices in under-funded settings (2, 43, 45). Additionally, a lack of government and organizational structures such as policies and directives, create an authorizing void for the promotion of family-focused practices and impede leadership support for translating such practices into practitioner's everyday work (45–48).

In recent years, greater attention to the process of implementing family-focused practices has resulted in developments to address these barriers. These include practice guidelines and frameworks for family-focused practice in AMHS (19, 49, 50), integrated training, implementation and research programs (51–53) and international collaboration supporting the integration of policy and research (54–56). While these significantly contribute to the understanding of what is needed to sustain family-focused practice in AMHS, there is a need to draw this knowledge together to consider the multiple components in combination to assist AMHS to implement and sustain family-focused practice. This article proposes a model for sustaining family-focused practice in AMHS.

Design and Method

The barriers to family-focused practice noted above illustrate the multi layered factors that impact sustainability and show it to be intimately linked with implementation. While sustainability is focused on the degree to which the intervention can continue to deliver its planned benefits, it relies on practitioners who are able to faithfully deliver it, who in turn need support from their organizations to enable them to deliver its core elements (57).

The field of implementation science studies strategies and structures to support implementation of research into practice and has developed a growing body of frameworks, models and theories (58, 59). It has been posited, however, that much of the work developed in implementation science is used to support other researchers but is not yet common knowledge within the practice world (60). Acknowledging healthcare settings as complex entities, has additionally led to a call for integrating complexity science with implementation science to enable a more dynamic approach to implementation research and practice that fits the reality of change in healthcare setting (61–63).

Sustaining family-focused practice is the work of the healthcare setting. While researchers, purveyors or innovators may develop, trial, pilot, or even implement a family-focused practice, the ongoing work of sustainability is dependent on those within the healthcare setting making the ongoing adjustments necessary for the practice to be ongoingly delivered (57, 64, 65). Equipping healthcare services to apply implementation science knowledge could assist them with evidence-based strategies for applying the necessary adjustments locally. This, however, requires the development and application of implementation tools, described by Westerlund et al. (60) as user- or practice-friendly tools, that are suitable for the context and flexible and able to be adapted to fit settings.

A model is an intentional simplification that can provide an accessible description to guide an implementation process or investigation and so can be applying theory to practice (58). Building on what is known about practitioner and organizational barriers to family-focused practice and frameworks from implementation science, this article proposes a model for actions to support the sustaining a family-focused practice in AMHS.

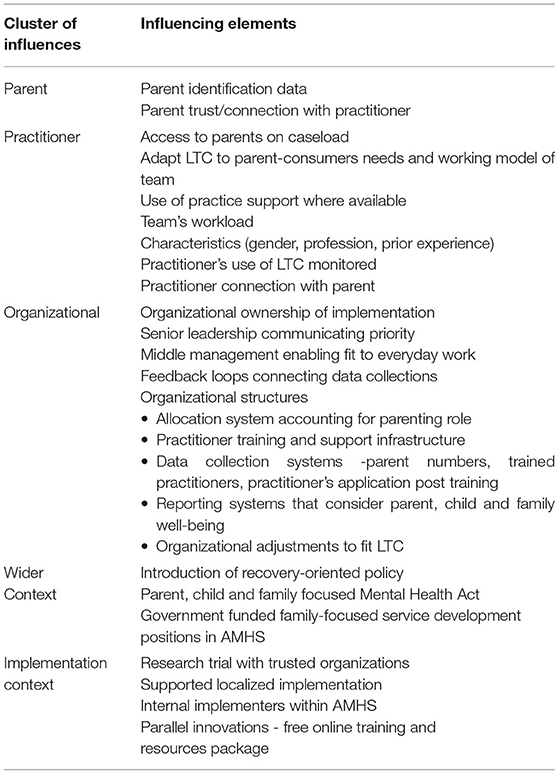

The model is drawn from a series of five mixed method studies exploring the sustainability of the family-focused practice, Let's Talk about Children (LTC) in eight AMHS in Victoria, Australia, involved in a RCT of LTC (52). The series of studies documented practitioner use and organizational capacity in the eight AMHS and developed an explanatory model of factors enabling sustainability in one AMHS (45, 66–69). The research series used a participatory research approach working in partnership with change agents within AMHS across Victoria. This helped to ground the model in practice wisdom and supporting it to be what Westerlund et al. (60) describes as “practice-friendly.” The outcomes of these studies were clustered deductively using sustainability and implementation models and frameworks (65, 70, 71). Five clusters of key elements were identified as influencing LTC's sustainability (69). These clusters related to (1) the parent, (2) the practitioner, (3) the organization, (4) the wider context and (5) the implementation context (see Table 1). While these elements can be considered individually, the studies' outcomes highlight the intersectionality between these elements as an important contributor to sustainability.

For example, a parent cannot be offered the family-focused practice if the practitioner allocated to them is not equipped with the skill and confidence to use it. Without a system to identify clients as parents, skilled practitioners may not be allocated parents. A skilled practitioner will find it difficult to maintain confidence if they are only rarely allocated a parent. Without a monitoring system, there will be no way of knowing if a practitioner is applying their skills, and if parents are being offered the family-focused practice to know if is being sustained. Additionally, without monitoring there is nothing to inform decision making and provide input for troubleshooting difficulties. If the wider systems do not fund AMHS to work with families or prioritize preventative mental health, an organization may find it difficult to integrate the family-focused practice into their model of care.

Conversely, a training program does not ensure sustainability, as trained practitioners may not be able to implement their new skills in practice. A system for identifying the parental status of clients will, in itself, not ensure that they are allocated for their care to trained practitioners, or have practitioners who are endorsed with the time and scope to use their skills. Data collected without feedback loops to adjust implementation cannot inform policy, training, support and allocation structures. These are each part of the picture of sustainability but on their own will not enable sustainability. They are required to be applied in combination.

Sustainability Model for Family-Focused Practice

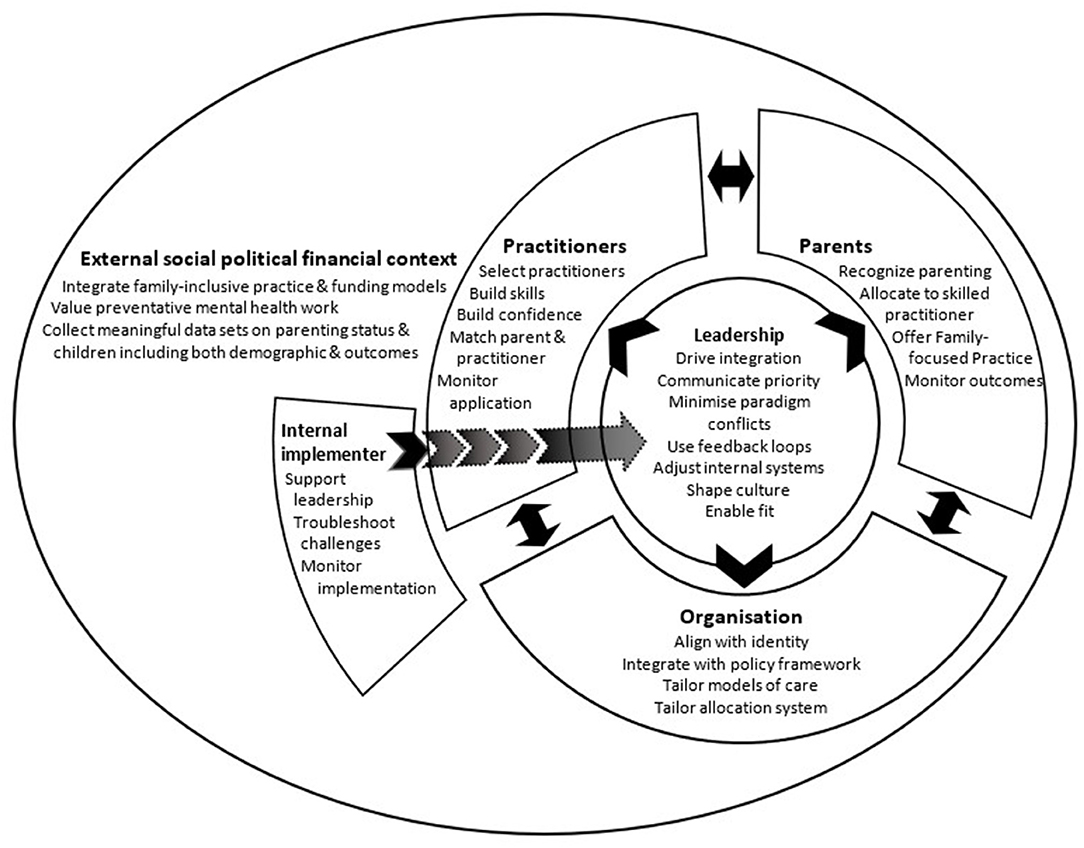

Working from these known key elements influencing sustainability of the family-focused practice of LTC, the following model was developed to operationalize the action points for AMHS and their external contexts to support family focused practice practice more broadly (See Figure 1: Sustainability model for family-focused practice). Framed in outcomes focused language to help operationalize action and reflecting the interconnecting nature of the elements, the model identifies six points of meso (intra organizational) and macro (broader contextual) level action, each incorporating multiple elements. Designed as an intentional simplification for a practical purpose, this model aims to support AMHS to hold in mind the complexity of sustainability and the requirement of simultaneous actions while providing actionable starting places. The first two actions points relate to how the AMHS engages with its service users and their practitioners. The next three action points focus on internal organizational activities important for implementation and sustainability. The last action point articulates important actions in the wider context.

Recognize, Allocate, and Measure Outcomes for Parents, Children, and Families

Recognition of a client's parental status can allow for service delivery to be tailored to address their, their children's and their family's needs. Knowledge of prevalence of parenting amongst the organization's clients can be used to drive the number and location of skilled practitioners needed to adequately enable parents, children and families to access family-focused practice. Organizations can support parents by allocating them to practitioners with the skills and confidence to deliver family-focused practice. Flexible allocation systems that can attend to the match between parent and practitioner readiness can support the therapeutic alliance and enable family-focused practice to be delivered. Recognition of parenting status also can support the organization's capacity to apply appropriate measures that assist them in monitoring both what services are delivered and if they give the expected benefits for parents, children and families.

Select, Support, and Monitor Practitioners

The selection of practitioners needs to take into account factors such as access to parents on their caseload, the practitioners' skills and knowledge of the impact of mental illness on parents, children and families, as well as their ability to hold a dual perspective while working with an individual. Building practitioners' skills and confidence to use family-focused practice requires flexible practice support that facilitates their capacity to reflect on and monitor their own practice against expected outcomes. Such support structures need to be co-developed so as to be tailored to fit practitioners' specific needs. Developing systems to monitor practitioners' application of family-focused practice provides a feedback loop that can help to identify support needs, communicate priority and address fidelity issues.

Integrate Within Organization Identity and Structures

Aligning family-focused practice within an organization's identity and integrating it into policy structures, can enable models of care to be tailored to fit family-focused practice, and support the incorporation of its core competencies into position descriptions and recruitment processes. Embedding family-focused practice into organizational policy also supports the development of infrastructure to enable practice, such as practitioner training, support and monitoring systems, and parent recognition and allocation systems. Organizational policy can additionally provide an anchor for family-focused practice in times of personnel or structural change that can facilitate its continued use. Furthermore, integrating outcome measures and reporting structures that incorporate whole-of-family well-being can help to reinforce a preventative mental health focus that is foundational to family-focused practice.

Leadership to Drive Sustainability

Organizational ownership is needed to support the internal adjustments required for the integration and sustainability of family-focused practice in AMHS. Adjustments to complex, internal structures need whole-of-organization commitment that requires leadership at multiple levels within the organization. At a higher level this includes communicating this work as a priority, developing training and support infrastructure, creating feedback loops and reporting systems. At the level of middle management this includes building cultures that promote recovery-focused family-inclusive mental health practice, facilitating the translation of family-focused practice into everyday practice and utilizing the feedback loops to support practice. Held together, the multiple levels of leadership and the structures they provide can help to minimize paradigm conflicts that exist for family-focused practice in AMHS.

Local Support for Implementation and Sustainability

Having an internal implementer to support leadership in the implementation process can help support sustainability. The presence of the internal implementer can be an anchor to the priority of the work and provide resources for leadership to build practitioners' skills and confidence. Working with leadership, they can assist in monitoring implementation through feedback loops that can enable ongoing adaptation of implementation processes to support sustainability.

Incorporate Family-Inclusive Preventative Mental Health Care in the Wider Context

Incorporating a family-inclusive, preventative lens within the funding and political context within which AMHS operates, creates a foundation for sustaining family focused practice. Integrating these lenses into recovery-focused mental health practice can support shifts in the funding models from an individual to whole-of-family perspective and the valuing of preventative mental health work that underpins family-focused practice. These shifts create an authorizing environment for AMHS leadership to give priority for delivering family-focus practice and the integration of family-focused practice into AMHS models of practice. These shifts also reinforce the need for reporting measures that account for parent, children and family outcomes and that emphasize resilience and well-being rather than risk.

Implications/Application

This model for sustaining family-focused practice in AMHS provides points of action for AMHS and their external contexts. The model extends existing peer reviewed work that identifies barriers and facilitators of implementation and models that explain sustainability, through drawing these together to provide actionable points of focus for those within an adult mental health system. It is intended to provide a practical framework for integrating the evidence in implementation science as applied to family-focused practice. The model is envisioned to be a tool for program developers, implementers, AMHS and policy-makers to consider both the components that support the sustainability and their interconnection.

As noted here, there is a need for ongoing attention to the complexity and importance of sustainability in the field of parents with mental ill-health, and their children and families. As AMHS are complex and changing entities, ongoing attention to the interconnection between practice, and the organisation's capacity to support practice, is required to enable continued quality of care. Sustaining family-focused practice, shifts the focus from the program, innovation or practice being implemented, to the mechanisms that enable them to be able to be utilized beyond the focused implementation or research trial. As sustainability happens within the work of the health service, equipping AMHS to not only implement but also sustain family-focused practice is pivotal for the field to promote better outcomes for parents, children and families.

This model goes some way to assist this process by identifying points of actions for AMHS and their external contexts, that are articulated as part of a whole, in order to address the complexity and work toward sustainability.

Further work is required to develop practice-friendly tools to support the application of this model. Practical implementation guides could operationalize each of the points of action. Monitoring and measuring tools could provide feedback loops on sustainability for AMHS. Coproduction of these application tools would support their usability by AMHS for their specific contexts. Additionally, this model provides a framework for developers of innovations, practices or interventions to build practice-friendly tools to support their sustained use in AMHS.

Conclusion

The model showcases the importance of actions that need operationalization at the organizational and wider context level to be able to influence the multiple systems involved in creating sustained family focus practice. This level of complexity can be overwhelming and difficult for program developers, implementers, AMHS and policy-makers to hold in mind, leading to a focus on the actions or elements in isolation. The model, however, highlights the inadequacy of an isolated view of actions or elements if the aim is to build sustainability at the local level that fit their context.

Author's Note

The content in this manuscript has been adapted from BA's thesis available online https://doi.org/10.26180/14214686.v1.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

BA conceived the article, developed the concept of the sustainability model, and drafted the article. MG, BO'H, and BW contributed to the interpretation of the analysis, the refining of the manuscript, reviewed drafts, and contributed to the write up. All authors were contributors to each of the five studies that underpin this work. All contributed to the analysis and drawing together of their combined outcomes and refining the sustainability model.

Funding

An Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship supported BA in her doctorate of philosophy, during which she developed the body of work underpinning the model.

Author Disclaimer

This article represents the authors' original work and has not been submitted for publication elsewhere.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The multiphase participatory doctorate of philosophy research was additionally supported by an advisory group giving invaluable input into the design and applicability. Membership comprised of Cheree Cosgriff (FaPMI coordinator and internal implementer), Georgia Cripps (FaPMI coordinator with Let's Talk practitioner experience), Helen Fernandes (Participatory research practitioner), Jane Shamrock (Qualitative Participatory Research Academic) and Brad Wynne (AMHS manager).

References

1. Rutter M, Quinton D. Parental psychiatric disorder: effects on children. Psychol Med. (1984) 14:853–80. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700019838

2. Maybery DJ, Foster K, Goodyear MJ, Grant A, Tungpunkom P, SkogØy BE, et al. How can we make the psychiatric workforce more family focused? In: Reupert AE, Maybery DJ, Nicholson J, Gopfert M, Seeman MV, editors. Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Distressed Parents and Their Families. 3rd ed. New York, NY: New York Cambridge University Press (2015). p. 301–11.

3. Nicholson J, Biebel K, Hinden B, Henry A, Stier L. Critical Issues for Parents with Mental Illness and their Families. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Mental Health Services (2001).

4. Gopfert M, Webster J, Seeman MV. Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Distressed Parents and Their Families. 1st ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press (1996).

5. Ballal D, Navaneetham J. Talking to children about parental mental illness: the experiences of well parents. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2018) 64:367–73. doi: 10.1177/0020764018763687

6. Brockington I, Chandra P, Dubowitz H, Jones D, Moussa S, Nakku J, et al. WPA guidance on the protection and promotion of mental health in children of persons with severe mental disorders. World Psychiatry. (2011) 10:93–102. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00023.x

7. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, Lucksted A, Cohen M, Falloon I, et al. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. (2001) 52:903–10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.903

8. Mottaghipour Y, Bickerton A. The pyramid of family care: a framework for family involvement with adult mental health services. Aust E J Adv Mental Health. (2005) 4:210–7. doi: 10.5172/jamh.4.3.210

9. Wyder M, Bland R. The recovery framework as a way of understanding families' responses to mental illness: balancing different needs and recovery journeys. Aust Soc Work. (2014) 67:179–96. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2013.875580

10. Foster KN, Maybery DJ, Reupert AE, Gladstone B, Grant A, Ruud T, et al. Family-focused practice in mental health care: an integrative review. Child Youth Serv. (2016) 37:129–55. doi: 10.1080/0145935X.2016.1104048

11. Price-Robertson R, Obradovic A, Morgan B. Relational recovery: beyond individualism in the recovery approach. Adv Ment Health. (2016) 15:108–20. doi: 10.1080/18387357.2016.1243014

12. Price-Robertson R, Olsen G, Francis H, Obradovic A, Morgan B. Supporting Recovery in Families Affected by Parental Mental Illness (CFCA Practitioner Resource). Melbourne, VIC: Child Family Community Australia information exchange, Australian Institute of Family Studies (2016). Available online at: https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/supporting-recovery-families-affected-parental-mental-illness

13. Marston N, Stavnes K, Van Loon LMA, Drost LM, Maybery DJ, Mosek A, et al. A content analysis of intervention key elements and assessments (IKEA): what's in the black box in the interventions directed to families where a parent has a mental illness? Child Youth Serv. (2016) 37:112–28. doi: 10.1080/0145935X.2016.1104041

14. Awram R, Hancock N, Honey A. Balancing mothering and mental health recovery: the voices of mothers living with mental illness. Adv Ment Health. (2017) 15:147–60. doi: 10.1080/18387357.2016.1255149

15. Beardslee WR, Wright E, Gladstone T, Forbes P. Long-term effects from a randomized trial of two public health preventive interventions for parental depression. J Fam Psychol. (2007) 21:703. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.703

16. McKay EA. Mothers with mental illness: an occupation interrupted. In: Esdaile SA, Olson JA, editors. Mothering Occupations: Challenge, Agency, and Participation. Philadelphia: FA Davis Company (2004). p. 238–58.

17. Reupert AE, Maybery DJ, Kowalenko NM. Children whose parents have a mental illness: prevalence, need and treatment. Med J Aust Open. (2012) 1:7–9. doi: 10.5694/mjao11.11200

18. Goodyear MJ, Obradovic A, Allchin B, Cuff R, McCormick F, Cosgriff C. Building capacity for cross-sectorial approaches to the care of families where a parent has a mental illness. Adv Ment Health. (2015) 13:153–64. doi: 10.1080/18387357.2015.1063972

19. Goodyear MJ, Hill T-L, Allchin B, McCormick F, Hine RH, Cuff R, et al. Standards of practice for the adult mental health workforce: Meeting the needs of families where a parent has a mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2015) 24:169–80. doi: 10.1111/inm.12120

20. Maybery DJ, Reupert AE. Parental mental illness: a review of barriers and issues for working with families and children. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2009) 16:784–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01456.x

21. Siegenthaler E, Munder T, Egger M. Effect of preventive interventions in mentally ill parents on the mental health of the offspring: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2012) 51:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.10.018

22. Rimehaug T. The ecology of sustainable implementation. Z Psychol. (2014) 222:58–66. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000166

23. Cooklin A, Bishop P, Francis D, Fagin L, Asen E. The Kidstime Workshops. A Multi-Family Social Intervention for the Effects of Parental Mental Illness. Manual. London: CAMHS Press (2012).

24. Wolpert M, Hoffman J, Martin A, Fagin L, Cooklin A. An exploration of the experience of attending the Kidstime programme for children with parents with enduring mental health issues: parents' and young people's views. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2015) 20:406–18. doi: 10.1177/1359104514520759

25. Leenman G, Arblaster K. Navigating rocky terrain: a thematic analysis of mental health clinician experiences of family-focused practice. J Mental Health Train Educ Pract. (2020) 15:71–83. doi: 10.1108/JMHTEP-04-2019-0022

26. Doesum K, Maia T, Pereira C, Loureiro M, Marau J, Toscano L, et al. The impact of the “semente” program on the family-focused practice of mental health professionals in Portugal. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:305. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00305

27. Lauritzen C, Reedtz C, Rognmo K, Nilsen MA, Walstad A. Identification of and support for children of mentally ill parents: a 5 year follow-up study of adult mental health services. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:507. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00507

28. Reedtz C, Lauritzen C, Stover YV, Freili JL, Rognmo K. Identification of children of parents with mental illness: a necessity to provide relevant support. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 9:728. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00728

29. Ruud T, Maybery D, Reupert A, Weimand B, Foster K, Grant A, et al. Adult mental health outpatients who have minor children: prevalence of parents, referrals of their children, and patient characteristics. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:163. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00163

30. Potijk MR, Drost LM, Havinga PJ, Hartman CA, Schoevers RA. “…and how are the kids?” Psychoeducation for adult patients with depressive and/or anxiety disorders: a pilot study. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00004

31. Jessop ME, De Bondt N. A consultation service for adult mental health service clients who are parents and their families. Adv Ment Health. (2012) 10:149–56. doi: 10.5172/jamh.2011.10.2.149

32. Goodyear MJ, Maybery DJ, Reupert AE, Allchin R, Fraser C, Fernbacher S, et al. Thinking families: a study of the characteristics of the workforce that delivers family-focussed practice. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2017) 26:238–48. doi: 10.1111/inm.12293

33. Grant A, Reupert A, Maybery D, Goodyear M. Predictors and enablers of mental health nurses' family-focused practice. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2019) 28:140–51. doi: 10.1111/inm.12503

34. Tchernegovski P, Hine R, Reupert AE, Maybery DJ. Adult mental health clinicians' perspectives of parents with a mental illness and their children: single and dual focus approaches. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:611. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3428-8

35. Maybery DJ, Goodyear MJ, Reupert AE, Grant A. Worker, workplace or families: what influences family focused practices in adult mental health? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2016) 23:163–71. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12294

36. Skogøy BE, Ogden T, Weimand B, Ruud T, Sørgaard K, Maybery D. Predictors of family focused practice: organisation, profession, or the role as child responsible personnel? BMC Health Serv Res. (2019) 19:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4553-8

37. Maybery DJ, Goodyear MJ, O'Hanlon B, Cuff R, Reupert AE. Profession differences in family focused practice in the adult mental health system. Fam Process. (2014) 53:608–17. doi: 10.1111/famp.12082

38. Grant A, Goodyear MJ, Maybery DJ, Reupert AE. Differences between Irish and Australian psychiatric nurses' family-focused practice in adult mental health services. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2016) 30:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.07.005

39. Gregg L, Adderley H, Calam R, Wittkowski A. The implementation of family-focused practice in adult mental health services: a systematic review exploring the influence of practitioner and workplace factors. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2021) 30:885–906. doi: 10.1111/inm.12837

40. Maybery DJ, Reupert AE. The number of parents who are patients attending adult psychiatric services. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2018) 31:358–62. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000427

41. Ballal D, Navaneetham J, Chandra PS. Children of parents with mental illness: the need for family focussed interventions in India. Indian J Psychol Med. (2019) 41:228–34. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_430_18

42. Dunn A, Startup H, Cartwright-Hatton S. Adult mental health service engagement with patients who are parents: Evidence from 15 English mental health trusts. Br J Clin Psychol. (2022). doi: 10.1111/bjc.12330

43. Isobel S, Allchin B, Goodyear M, Gladstone BM. A narrative inquiry into global systems change to support families when a parent has a mental illness. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:310. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00310

44. Damanpour F. Organizational innovation: a meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Acad Manage J. (1991) 34:555–90. doi: 10.5465/256406

45. Allchin B, Goodyear MJ, O'Hanlon B, Weimand BM. Leadership perspectives on key elements influencing implementing a family-focused intervention in mental health services. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 27:616–27. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12615

46. Grant A, Reupert AE. The impact of organizational factors and government policy on psychiatric nurses' family-focused practice with parents who have mental illness, their dependent children, and families in Ireland. J Fam Nurs. (2016) 22:199–223. doi: 10.1177/1074840716643770

47. Biebel K, Nicholson J, Williams V, Hinden BR. The responsiveness of state mental health authorities to parents with mental illness. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2004) 32:31–48. doi: 10.1023/B:APIH.0000039661.54974.ce

48. Hinden B, Wolf T, Biebel K, Nicholson J. Supporting clubhouse members in their role as parents: necessary conditions for policy and practice initiatives. Psychiatr Rehabil J Fall. (2009) 33:98–105. doi: 10.2975/33.2.2009.98.105

49. Foster KN, Goodyear MJ, Grant A, Weimand B, Nicholson J. Family-focused practice with EASE: a practice framework for strengthening recovery when mental health consumers are parents. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2019) 28:351–60. doi: 10.1111/inm.12535

50. Nicholson J, English K, Heyman M. The parenting well learning collaborative feasibility study: training adult mental health service practitioners in a family-focused practice approach. Community Ment Health J. (2021). doi: 10.1007/s10597-021-00818-5

51. Solantaus T, Toikka S. The effective family programme: preventative services for the children of mentally ill parents in Finland. Int J Mental Health Promot. (2006) 8:37–44. doi: 10.1080/14623730.2006.9721744

52. Maybery DJ, Goodyear MJ, Reupert AE, Sheen J, Cann W, Dalziel K, et al. Developing an Australian-first recovery model for parents in Victorian mental health and family services: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. (2017) 17:198. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1357-4

53. Yates S, Gatsou L. Undertaking family-focused interventions when a parent has a mental illness - possibilities and challenges. Practice. (2020) 33:1–16. doi: 10.1080/09503153.2020.1760814

54. Nicholson J, Reupert AE, Maybery DJ, Grant A, Lees R, Mordoch E, et al. The policy context and change for families living with parental mental illness. In: Reupert A, Maybery D, Nicholson J, Gopfert M, Seeman MV, editors. Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Distressed Parents and Their Families. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press (2015). p. 354–64.

55. Ruud T. Routine outcome measures in Norway: only partly implemented. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2015) 27:338–44. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1054268

56. Skogøy BE, Sørgaard K, Maybery D, Ruud T, Stavnes K, Kufås E, et al. Hospitals implementing changes in law to protect children of ill parents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3393-2

57. Stirman SW, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci. (2012) 7:1–19. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17

58. Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

59. Moullin JC, Sabater-Hernández D, Fernandez-Llimos F, Benrimoj SI. A systematic review of implementation frameworks of innovations in healthcare and resulting generic implementation framework. Health Res Policy Syst. (2015) 13:11. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0005-z

60. Westerlund A, Nilsen P, Sundberg L. Implementation of implementation science knowledge: the research-practice gap paradox. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. (2019) 16:332–4. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12403

61. Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. (2018) 16:95. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1089-4

62. Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long JC, Ellis LA, Herkes J. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med. (2018) 16:63. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1057-z

63. Long KM, McDermott F, Meadows GN. Being pragmatic about healthcare complexity: our experiences applying complexity theory and pragmatism to health services research. BMC Med. (2018) 16:94. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1087-6

64. Dearing JW. Evolution of diffusion and dissemination theory. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2008) 14:99–108. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000311886.98627.b7

65. Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:2059–67. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300193

66. Allchin B, O'Hanlon B, Weimand BM, Boyer F, Cripps G, Gill L, et al. An explanatory model of factors enabling sustainability of let's talk in an adult mental health service: a participatory case study. Int J Ment Health Syst. (2020) 14:48. doi: 10.1186/s13033-020-00380-9

67. Allchin B, O'Hanlon B, Weimand BM, Goodyear MJ. Practitioners' application of Let's Talk about Children intervention in adult mental health services. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 29:899–907. doi: 10.1111/inm.12724

68. Allchin B, Weimand BM, O'Hanlon B, Goodyear MJ. Continued capacity: factors of importance for organizations to support continued Let's Talk practice – a mixed-methods study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 29:1131–43. doi: 10.1111/inm.12754

69. Allchin R. Exploring the Implementation and Sustainability of Let's Talk About Children – A Model for Family-Focused Practice in Adult Mental Health Services. Clayton, VIC: Monash University (2020).

Keywords: sustainability, family-focused practice, mental health promotion, parents, mental ill-health, Let's Talk about Children intervention

Citation: Allchin B, Weimand BM, O'Hanlon B and Goodyear M (2022) A Sustainability Model for Family-Focused Practice in Adult Mental Health Services. Front. Psychiatry 12:761889. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.761889

Received: 20 August 2021; Accepted: 21 December 2021;

Published: 18 January 2022.

Edited by:

Jean Lillian Paul, Medizinische Universität Innsbruck, AustriaReviewed by:

Lynsey Gregg, The University of Manchester, United KingdomStephanie Best, Macquarie University, Australia

Alexandra Harrison, Harvard University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Allchin, Weimand, O'Hanlon and Goodyear. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Becca Allchin, cmViZWNjYS5hbGxjaGluQG1vbmFzaC5lZHU=

Becca Allchin

Becca Allchin Bente M. Weimand

Bente M. Weimand Brendan O'Hanlon

Brendan O'Hanlon Melinda Goodyear

Melinda Goodyear