- 1Institute for Population Health, Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar, Ar-Rayyan, Qatar

- 2Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar, Ar-Rayyan, Qatar

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted telemedicine use for mental illness (telemental health).

Objective: In the scoping review, we describe the scope and domains of telemental health during the COVID-19 pandemic from the published literature and discuss associated challenges.

Methods: PubMed, EMBASE, and the World Health Organization's Global COVID-19 Database were searched up to August 23, 2020 with no restrictions on study design, language, or geographical, following an a priori protocol (https://osf.io/4dxms/). Data were synthesized using descriptive statistics from the peer-reviewed literature and the National Quality Forum's (NQF) framework for telemental health. Sentiment analysis was also used to gauge patient and healthcare provider opinion toward telemental health.

Results: After screening, we identified 196 articles, predominantly from high-income countries (36.22%). Most articles were classified as commentaries (51.53%) and discussed telemental health from a management standpoint (86.22%). Conditions commonly treated with telemental health were depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. Where data were available, most articles described telemental health in a home-based setting (use of telemental health at home by patients). Overall sentiment was neutral-to-positive for the individual domains of the NQF framework.

Conclusions: Our findings suggest that there was a marked growth in the uptake of telemental health during the pandemic and that telemental health is effective, safe, and will remain in use for the foreseeable future. However, more needs to be done to better understand these findings. Greater investment into human and financial resources, and research should be made by governments, global funding agencies, academia, and other stakeholders, especially in low- and middle- income countries. Uniform guidelines for licensing and credentialing, payment and insurance, and standards of care need to be developed to ensure safe and optimal telemental health delivery. Telemental health education should be incorporated into health professions curricula globally. With rapidly advancing technology and increasing acceptance of interactive online platforms amongst patients and healthcare providers, telemental health can provide sustainable mental healthcare across patient populations.

Systematic Review Registration: https://osf.io/4dxms/.

Introduction

Mental illness is a significant global public health issue; it is estimated to account for 13% of disability-adjusted life-years and 32.4% of years lived with disability (1). The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the mental illness of vulnerable communities and individuals. Those with mental illnesses are highly vulnerable to suffer exacerbations during times of stress, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, due to their reliance on their social support network and their propensity to loneliness and isolation (2). Multiple reports indicate a rise in the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and substance use across the demographic spectrum since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (3–7).

During the pandemic, there was an increase in the uptake of telehealth. This digital tool, which was used sparingly prior to the pandemic, has helped enhance access to healthcare services and has proven to be safe and effective for evaluation and management (8, 9). It further leverages the expertise of highly specialized professionals across the globe (9). The myriad methods of telehealth delivery emphasize its potential to connect with marginalized populations, such as refugees or those living in remote areas (9).

Several terminologies in the published literature are currently interchangeably used to characterize telehealth related to mental health. In this review, we use the term “telemental health” [a term previously used in the literature and the National Institute of Mental Health (10–13)] in order to comprehensively describe the complete scope of Internet and Communication Technologies (ICT) based range of diagnostic and preventive mental health services. Scholarly literature has ascertained the need to guide clinical and public health decision-making by conducting scoping reviews to identify evidence, clarify concepts and characteristics, and determine research gaps (14, 15). This differentiates it from a systematic review, which is used to answer specific and well-defined research questions. As our purpose was to characterize the nature and context of the evidence in the published literature on telemental health, we decided to conduct a scoping review. The objective for this scoping review and evidence synthesis is to delineate and map the scope and domains of telemental health during the COVID-19 pandemic from the published literature and discuss associated challenges.

Methods

Overview

The scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer Manual (16, 17), the framework suggested by Arksey and O'Malley (15), and the evidence and gap map was based on the Campbell Collaboration Guidance (18). The protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework (registration ID: https://osf.io/4dxms) (19).The scoping review is reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Supplementary Material 1) (20) and the PRISMA for Abstracts Checklist (Supplementary Material 2) (21).

Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria were established a priori as described in the protocol and are summarized here. All article types published within the COVID-19 pandemic context were included–viewpoints, observational articles, qualitative data, and systematic reviews. We considered all articles that described the use of any form of ICT, such as telephone calls, text messaging, video conferencing, smartphone applications, websites, blogs, store-and-forward, etc., for the purpose of prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment, counseling, rehabilitation, and any other form of mental healthcare during COVID-19 as telemental health outcomes, as determined by the WHO definition of telemedicine (22, 23). We included any type of population without restriction (e.g., adults, children & adolescents, people with and without chronic disease, people with and without pre-existing mental illness, people who were diagnosed with COVID-19 etc.), provided that some ICT modality was used to provide for their mental health needs. No language or geographical restrictions were implemented.

We excluded any article that was not relevant to mental health or that focused exclusively on telehealth use in medical education or explored the use of telemental health prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Search Strategy

Two reviewers (AA and SD) systematically searched Medline (via PubMed), Embase, and the World Health Organization's (WHO) Global COVID-19 Research Database, with an end-date of August 23, 2020. The end-date coincided with the increasing recognition of the mental health consequences of the pandemic and the emergence of literature to that effect (24, 25). For Medline and Embase, both controlled vocabulary and keyword searches (a combination of keywords related to COVID-19, mental health, and telehealth) were used. The WHO Global COVID-19 Research Database allows a keyword search only. Details are provided in Supplementary Material 3. We also systematically checked the bibliographies of relevant included articles for additional references. Further, we created a database of articles from related scoping reviews that we previously conducted (23, 26) and, from these, were able to identify several articles that were not picked up in our initial search strategy. The search strategy was verified by a senior librarian from Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar.

Study Selection

AA removed all identified duplicates using Rayyan (27), the systematic review software, following which two reviewers (AA and AJ) screened the identified articles in a two-stage screening process (title/abstract screening and full-text screening). Discrepancies at both stages were reconciled through discussion with the team. The reasons for exclusion at each step were recorded.

Data Extraction

A standardized charting sheet was developed by AA, AJ, and SD to extract relevant information, which was modified after piloting on a small sample of articles. Once the form was finalized, AA and AJ each extracted 50% of the identified articles and then checked the remaining 50% of each other's extraction. Discrepancies were resolved between AA and AJ while keeping the review team informed. If any retrieved article was in a language unknown to the authors, the article was translated into English using Google Translate.

Data Synthesis

Data was extracted into Microsoft Excel and synthesized using descriptive statistics. Following the recommendations of the Campbell Collaboration (18), we synthesized the evidence and used gap mapping to assess the strength of the evidence included in our scoping review. We classified mental illnesses using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria (28) to understand the breadth of use of telemental health. If an article described multiple DSM-5 disorders, these were tallied separately, hence the sum totals reported below may not add up to 100%.

We used the telehealth framework developed in 2017 by the National Quality Forum (NQF) (29) to measure telehealth use for delivering healthcare. The framework uses specific domains to categorize the outcomes of telehealth including: (i) Access to Care, (ii) Financial Impact, (iii) Patient Experience, (iv) Healthcare Provider Experience, and (v) Effectiveness. In addition, using the sentiment analysis framework (30, 31), we evaluated the aforementioned domains as “celebratory” (if telehealth viewed positively by the included article authors), “contingent” (if included article authors were undecided between the pros and cons of telehealth), and “concern” (if included article authors considered the negatives to outweigh the positives of telehealth), as used in previously published literature (26, 32, 33). AA performed the sentiment analysis, with SD randomly checking 50% of the analysis to ensure integrity of the data.

Results

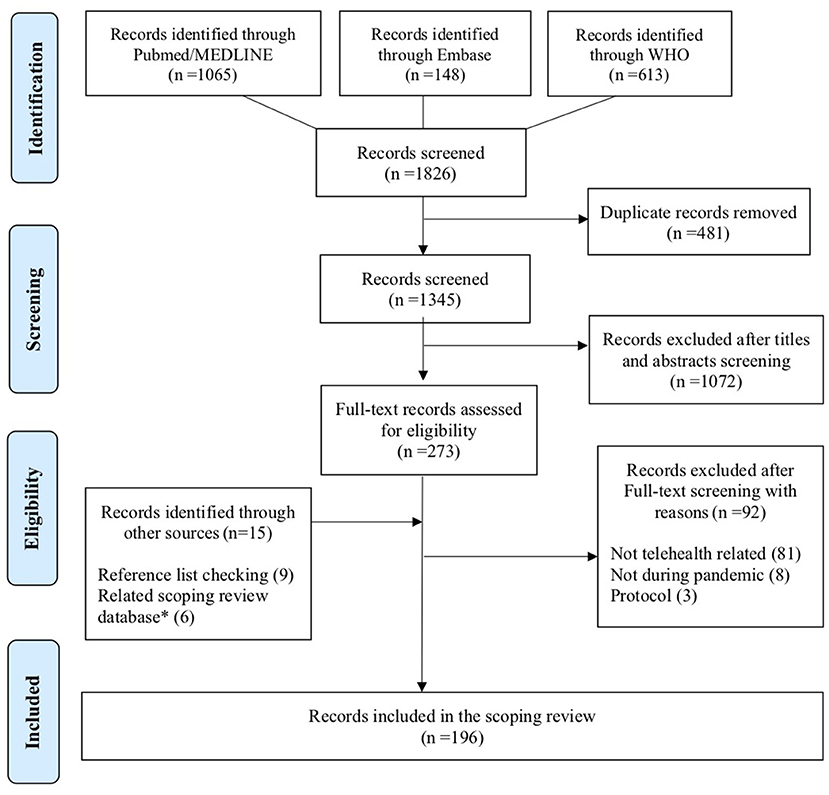

Our primary search strategy identified 1,826 articles, from which 481 duplicates were removed. Of the remaining 1,345 articles, 1,072 were excluded during title and abstract screening and 92 during full text screening. The supplementary search strategy yielded 15 articles, so a total of 196 articles were finally included in our scoping review. This is illustrated in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). The list of included articles is reported in Supplementary Material 4.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2009 flowchart of the systematic review's inclusion. *Database on telemedicine from previous scoping reviews.

The 196 articles included in the scoping review were predominantly commentaries, viewpoints, and opinions (101, 51.53%), followed by primary studies (48; 24.45%) and reviews, recommendations, and guidelines (47; 23.98%). The articles were published across 114 journals, the majority of which were specialized in mental health, psychiatry, or related fields. The remaining journals were either general medicine journals or focused on fields, such as e-health, adolescent medicine, or occupational health. While the journal that published the highest number of the included articles followed a subscription-based model, most articles were published in hybrid or open-access journals. Most of the identified articles were published in English (194/196; 98.98%), followed by two each in French and German (2/196; 1.02%) and one each in Polish, Portuguese, and Russian (1/196; 0.51%).

The identified articles described the context of 26 countries; however, most (95/196; 48.47%) articles did not specify the country of focus. Of the articles that specified a country, most mentioned the US (31/196; 15.82%), followed by Italy and the UK, each with six articles (6/196; 3.06%). Using the WHO's regions, most articles focused on the Americas (38/196; 19.39%) and Europe (32/196; 16.32%), followed by the Western Pacific (12/196; 6.12%), South East Asia (5/196; 2.55%), and the Eastern Mediterranean (3/196; 1.53%). Most articles focused on the World Bank's high-income (71/196; 36.22%) and upper-middle income (15/196; 7.65%) countries. Only four articles focused on lower-middle income countries (4/196; 2.04%) and none on low-income countries. Detailed tables are provided in Supplementary Material 5.

The articles identified in our review were mostly written with a specific purpose of telemental health (189/196; 96.43%), while the remaining articles were general articles describing ethics of telemental health, digital privacy rights, etc. (7/196; 3.57%). Of those with a specific purpose, most of the articles described management (169/189; 89.42%); eleven articles reported both management and prevention (focused on the prevention of mental illness) (11/189; 5.82%); six articles described the preventative context only (6/189; 3.18%); two articles described both management and rehabilitative services (restoration of optimal level functioning in those with a mental illness) (2/189; 1.06%); and one article focused solely on rehabilitative services (1/189; 0.53%). The setting in which telehealth was administered was described as home- and hospital-based (55/196; 28.06%), home-based only (25/196; 12.76%), hospital-based only (14/196; 7.14%), home and school-based (2/196; 1.02%), or school-based only (1/196; 0.51%). The setting was unspecified in the remaining 99 articles (99/196; 50.51%).

There were 17 categories of healthcare providers involved in the use of telemental health in the identified articles, the most common of which were psychologists and psychiatrists (Supplementary Material 6). The specific telemental health techniques administered (such as cognitive behavioral therapy, prolonged exposure therapy, etc.) are listed in Supplementary Material 7. The telehealth modality described in the articles included telephone hotlines and telephone visits, videoconferencing software, text messaging, smartphone-based applications, online chats and emails, websites, social media, and blogs.

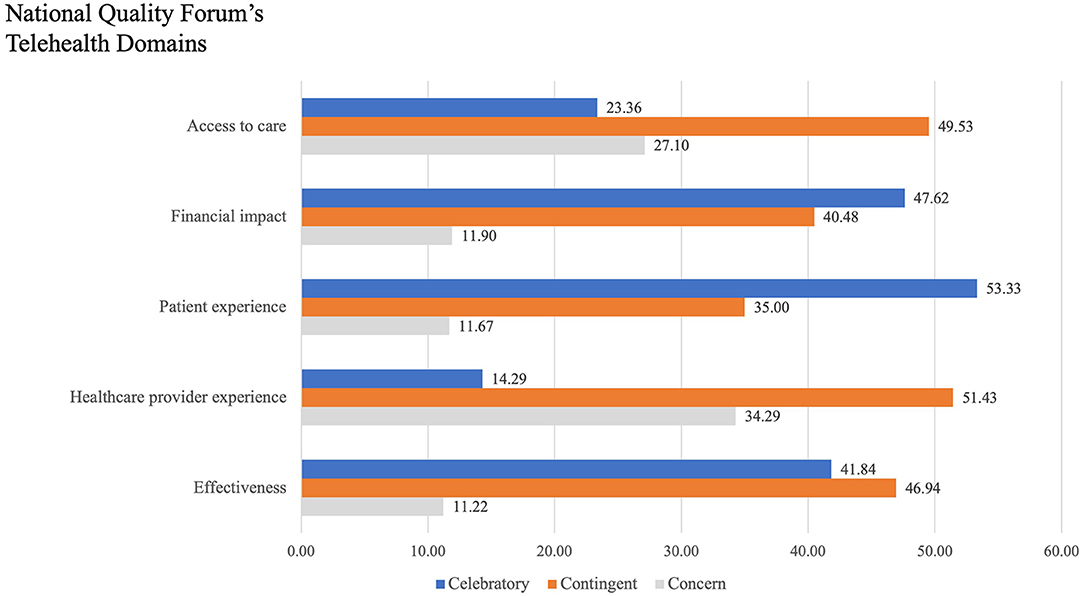

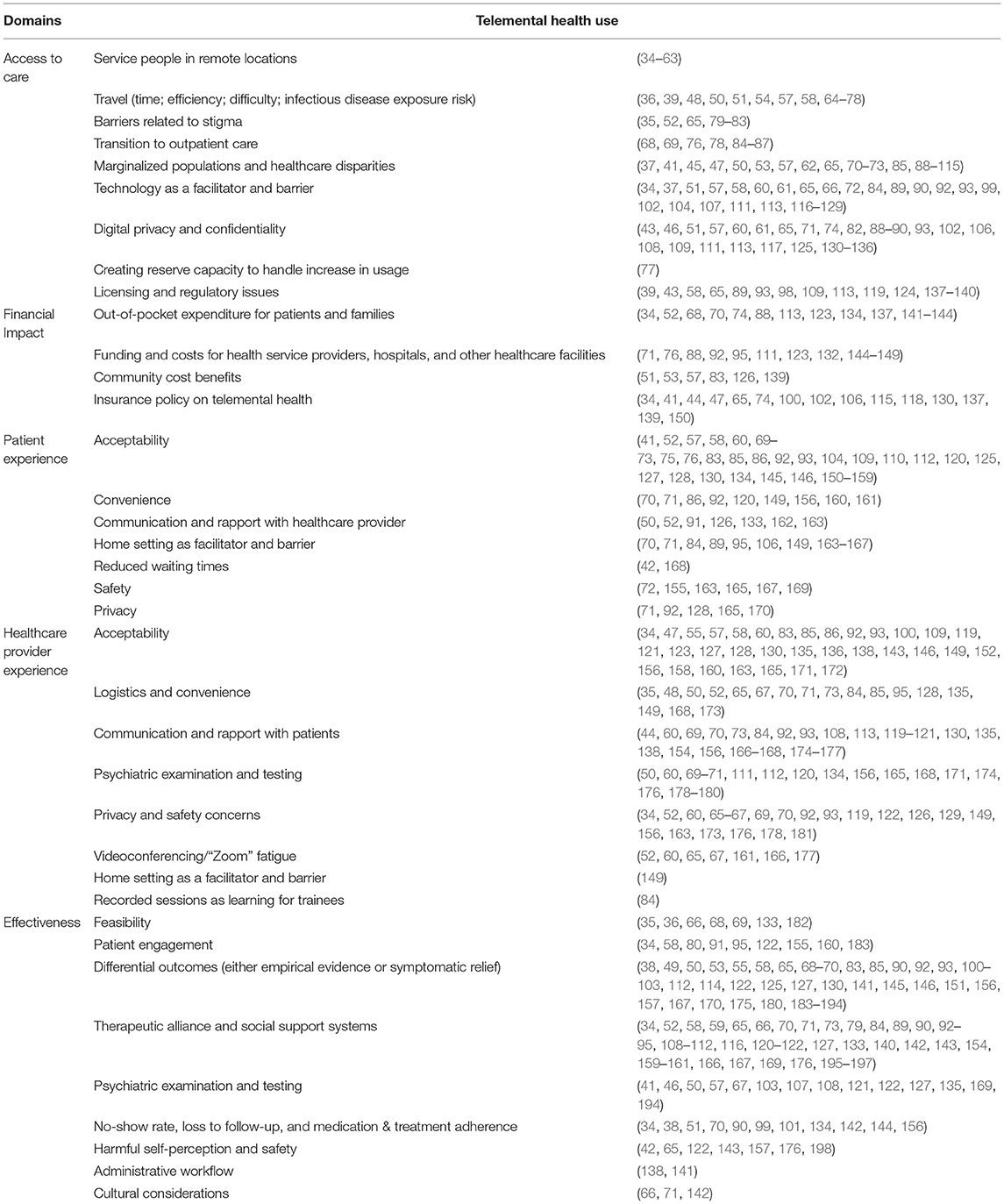

We classified the articles using the domains of the NQF's framework (29), the results of which are depicted in Table 1. The “Access to Care” domain in the articles primarily discussed the provision of quality service to marginalized populations, technological barriers, and privacy and confidentiality issues. The “Financial Impacts” domain focused on out-of-pocket savings for individuals and families and insurance policy decisions. The “Patient Experience” domain predominantly focused on acceptability/satisfaction and the patients' home setting as both a barrier and facilitator. The principal aspects discussed under the “Healthcare Provider Experience” domain were acceptability/satisfaction, building a therapeutic alliance, and privacy and safety. With regards to the “Effectiveness” domain, the therapeutic alliance and the difference in measured outcomes were most frequently discussed. We used the sentiment analysis framework (30, 31) to describe the authors' outlook within the domains of the NQF framework, as shown in Figure 2. A majority of the included articles were “celebratory” (telehealth viewed positively by the article authors), or “contingent” (article authors were undecided between the pros and cons of telehealth), in describing the utilization of telemental health in each of the five domains. Articles classified as “concern” (article authors considered the negatives to outweigh the positives of telehealth) raised issues of privacy and confidentiality, digital equity, and technological challenges.

Table 1. Telemental health usage classified by the NQF's framework domains describing the objectives of included publications.

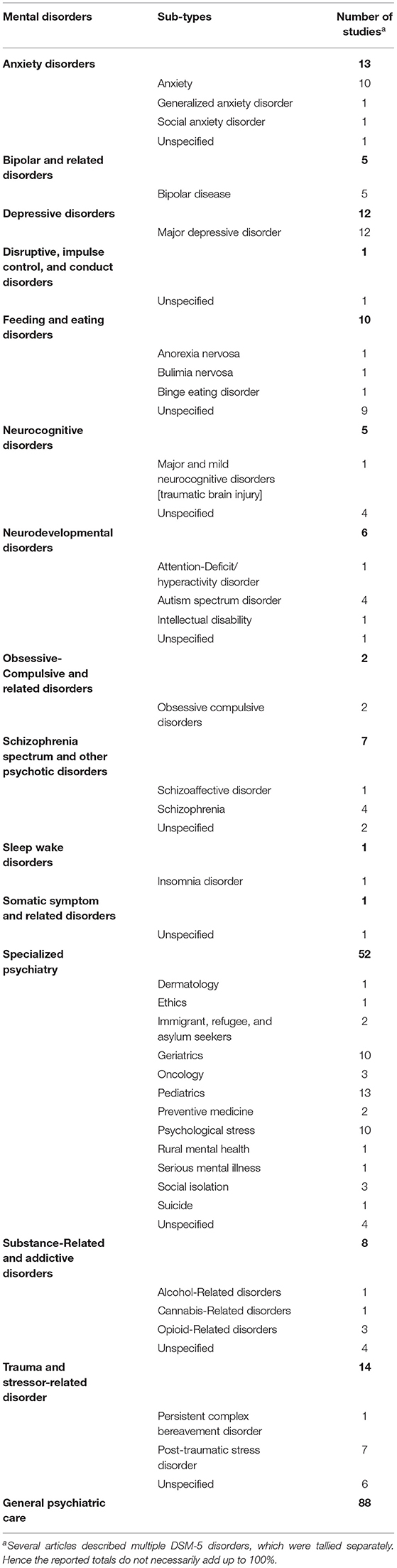

Just over half of all articles described a specific mental health diagnosis (109/196; 55.61%), as described by the DSM-5. More specifically, the most frequently cited DSM-5 disorders were trauma and stressor-related disorders (14/196; 7.14%), anxiety disorders (13/196; 6.63%), and depressive disorders (12/196; 6.12%). The most frequent disorder subtypes, when specified, were depression (12/196; 6.12%), anxiety (10/196; 5.10%), and eating disorders (9/196; 4.59%). A total of 52 articles examined mental health disorders in specific scenarios that could not be classified using the DSM-5 criteria (such as mental health in pediatric, oncology, geriatric, and refugee-care settings), and these were grouped together under “Specialized psychiatry” (52/196; 26.53%). Table 2 illustrates the DSM-5 disorders and subtypes identified in the articles.

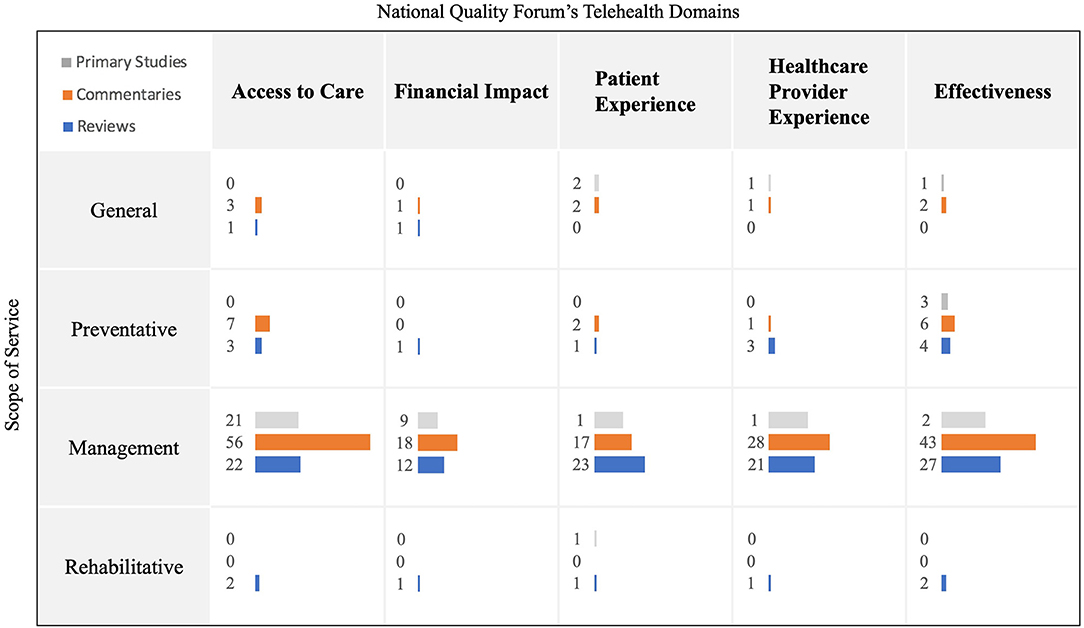

To inform the context of telemental health, we harmonized the evidence into a visual map by comparing the scope of service (management, preventative, rehabilitative, general) to each domain within the NQF's telemental health framework, and the design of the study (Figure 3). The map demonstrates that most articles examined management using telemental health and a few articles examined prevention or rehabilitation. Furthermore, commentaries were the most common study design included in our scoping review, nearly double of the other designs. Most articles described the Access to Care and Effectiveness domains, with relatively few focusing on the Financial Impact.

Figure 3. Visual map for scope of service, NQF framework and article type. Preventative: Screening/Triage/Lifestyle/Social connectedness; Management: Treatment/Follow-up Rehabilitative: restoration of optimal level functioning in those with a mental illness; General: No definitive focus; Gray bars: Primary studies; Orange bars: Commentaries, viewpoints, editorials, perspectives; Blue bars: Literature and Scoping reviews; The length of the bars and the numbers correspond to the total number of identified articles.

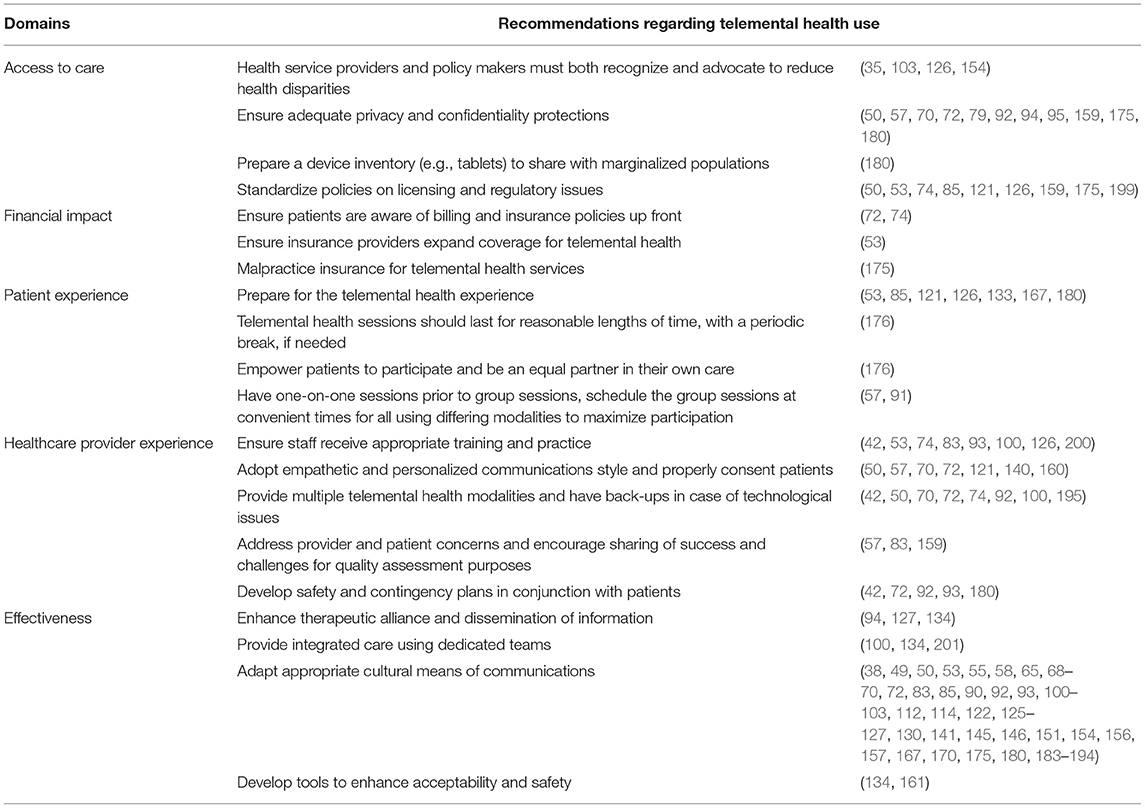

Table 3 summarizes the recommendations, where they were made, for enhancing telemental health from the included articles by NQF domain (36/196; 18.37%). Most articles called for standardizing licensing and regulatory policies, ensuring appropriate privacy and confidentiality measures, adequate preparation of patients and healthcare providers for the telemental health experience, having a back-up plan for technological glitches, and ensuring the presence of safety measures in case of a psychiatric emergency.

Discussion

In this scoping review and evidence synthesis, we collated the extent and use of telemental health during the COVID-19 pandemic and lessons learned that could be beneficial for the future. Most articles in the scoping review described the management aspects of telemental health provision, with only a few describing preventative or rehabilitative aspects. Thus, there is much scope for improvement in order to use telemental health for prevention and early diagnosis of mental illnesses. This can be facilitated by building resilience through social network and connections, augmenting social services and surveillance systems, and enhancing surge capacity and redundancy in the mental healthcare system (5). Approximately half of the articles in our review described general telemental health care rather than focusing on a specific mental health disorder. This finding illustrates the generalizability of telemental health and its application to all aspects of the telemental health continuum, from prevention to management to rehabilitation.

Our findings demonstrate that most of the identified articles described telemental health in the context of high-income countries, which is reflected in the scholarly literature (23, 26). Current data suggest that telemental health can be effectively used in these countries (23, 26). However, there is a scarcity of evidence supporting its use in low-resource settings (202–204). This highlights the importance of data collection from lower middle-income as well as low-income countries.

While telemental health is increasingly becoming more mainstream in high-income countries, the identified articles note that challenges regarding regulations, credentialing and licensing, and standards of care must be overcome. A careful cost-benefit analysis must be conducted for each practice, due to vagaries that are region-specific. Further work must be undertaken to enhance access to and affordability of technology (123). Identified data, while limited in low and middle-income countries, suggests that telemental health is beneficial in these settings. The effectiveness of telemental health may vary in more culturally diverse settings, and the cost of implementation in low- and middle-income countries is unclear. Issues surrounding privacy and confidentiality must be addressed in settings with less-than-robust healthcare systems and high levels of stigma toward mental health problems (202). A total of four identified articles discussed the ethical implications of telemental health (88, 89, 173, 178). The same ethical obligations of patient beneficence; fidelity and responsibility; distributive justice; integrity; privacy; and autonomy apply to telemental health (178, 205). However, telemental health also has unique challenges that must be considered, such as handling patient encounters occurring via third-party videoconferencing software (178, 206). Frameworks have been described in the published literature to ensure that the standards of care are adhered to, and patient autonomy and privacy are maintained (207, 208).

An important consideration in the application of telemental health is the setting in which it is used, as different NQF domains may be of varying importance in different circumstances, as highlighted in the identified articles. For instance, the privacy and security of individuals using telemental health is especially important in a school-based setting or for those being treated for substance use. The identified articles illustrated the use of telemental health across settings such as homes, hospitals, and schools. However, the majority described the use of telemental health for the provision of home-based care. This can provide the healthcare provider with insight into social and environmental conditions at home (204, 209). The healthcare provider is thus better able to assess some of the social determinants of health, information on which has been otherwise been lacking in the current modern medical system (210). Several articles also emphasized the importance of schools as an additional avenue to ensure that children have access to healthcare. Over a quarter of the identified articles discussed telemental health use in specialized situations, such as pediatrics and adolescent care, geriatrics, oncology, and refugee-care, strengthening the argument that telemental health needs to be tailored to specific scenarios in order to deliver optimal care (160).

The articles included in our review substantiate the claim that telemental health is useful in reducing barriers to mental healthcare access for traditionally marginalized communities, such as those living in remote locations, migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. Because of the near-ubiquity of smartphones and other internet-enabled devices, telemental health can cater to the needs of such populations (211). However, challenges associated with telemental health exist in these communities that must be addressed. For instance, there is a higher likelihood of digital inequity among the vulnerable populations, with lack of affordability or access to broadband services, patients' unfamiliarity, or the inability to use ICT. In addition, a lack of privacy and higher levels of stigma may also exist as compared to other populations (212–214).

When we categorized the concerns raised in the included articles by DSM-5 criteria (28), we found depression, anxiety, and eating disorders to be the most common concerns. This is not unexpected, given concern over the severity and transmissibility of COVID-19, limited hospital capacity during the initial wave of the pandemic, misinformation and rumors about the pandemic, and the public health measures that were implemented (movement restrictions, limiting in-person interactions, quarantine, isolation, etc.) to reduce the risk of transmission (214, 215).

The NQF framework (29) for tele-mental health allows us to structure our findings. In doing so, we identified that the NQF domains that were addressed in most detail were Access to Care and Effectiveness. Most articles identified telemental health as a boon toward these domains by alleviating the stigma, and time and privacy barriers facing patients and healthcare providers. However, several articles noted challenges in using telemental health services, including the inability of certain at-risk communities to comprehend and use the technology, perceived inefficacy, and technological challenges. Overall sentiment analysis demonstrates a celebratory sentiment toward the Patient Experience and Financial Impact domains, and contingent sentiment toward the other domains. Despite a robust evidence base and the global pivot to telemental health use during the COVID-19 pandemic, there remains work to be done to ensure that it is affordable, effective, and accessible to all communities worldwide.

Another finding is that telemental health facilitates and enhances the delivery of integrated and quality care when multiple specialist healthcare providers may be needed or when the providers are remotely located (210). Specific competencies have been developed to ensure that healthcare providers are proficient in the delivery of interdisciplinary telemental health care (216, 217). Telemental health also permits family members to be involved in providing support to patients if they are in different geographic locations (210).

Several findings of this scoping review resonate with the findings in literature that has been published recently–telemental health reduced no-show rates (209), had equivalent outcomes to in-person sessions (218) and yielded satisfaction among both patients and healthcare providers (209). Challenges cited included concerns about confidentiality and privacy issues, and disparities in digital equity (218, 219). Other issues that have more recently been highlighted include screen fatigue (150, 220, 221), and a loss in sense of community for patients, due to fewer in-person interactions with fellow patients and healthcare providers (34).

Telemental health use is likely to continue to expand in the future. It confers myriad advantages, such as enhanced access to marginalized communities with limited mental health resources, mitigating individual stigma and creating reserve health system capacity. Telemental health can serve to reduce health disparities and lower the impact of future crises. The findings can help inform policymakers and healthcare institutions on making decisions about the future applications of telemental health.

Our scoping review has some limitations. We did not formally assess the quality of the included articles, the majority of which were commentaries. However, all articles were peer-reviewed, which reassures concerns about quality. Since a majority of the articles described the high-income context, the generalizability of the findings of this scoping review will likely be limited to high-income countries only. Further research in the low- and middle-income countries is warranted, and investment, perhaps with funding from high-income countries/global funding agencies, can help with the implementation of telemental health in countries where it is currently lacking.

Issues that remain unexplored in the published literature include the need for higher quality evidence, such as randomized controlled trials to ensure best clinical outcomes; best measures to address the digital divide; distinction in usage between the various telemental health modalities (videoconferencing vs. audio-only healthcare vs. text messaging systems), and best practices for training healthcare providers to transition to telemental health. We did not investigate the use of artificial intelligence, an important research topic as it is becoming a part of telemental services, as this was beyond the scope of the study. Policy makers and researchers must prioritize optimizing telemental health services to cater to at-risk populations and address the aforementioned concerns and challenges.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that telemental health could prove to be useful and effective during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we must continue to explore opportunities to improve and enhance the delivery of telemental health for optimum health benefit to communities worldwide. The development of high-speed internet infrastructure globally will facilitate the uptake of telemental health. Given the dearth of comprehensive data on the outcomes of telemental health in low resource settings, as well as rural and remote communities, a greater investment into resources and additional research are needed. Guidelines and policies for licensing, geographical coverage, payment, insurance, and standard of care need to be put in place. Further, telemental health education should be incorporated into medical and health professions curricula worldwide to allow for better acceptance and familiarity among healthcare providers. Telemental health has the potential to be beneficial, especially for marginalized communities. Healthcare providers should embrace and offer evidence-based telemental health services to populations most in need in order to promote optimum health.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

AA, SD, SC, and RM collectively contributed to the conception and design of the study. NA-K reviewed the literature. AA and SD designed the search strategy, while screening and data extraction were conducted by AA and AJ in consultation with SD, SC, and RM. Analysis and manuscript drafting was carried out by AA with support from SD, AJ, NA-K, SC, and RM. All authors participated in the interpretation of the results, reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

All authors would like to thank Sinéad M. O'Rourke, Content Development Specialist, Distributed eLibrary, Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar for English language editing services; Sa'ad Laws, Education & Research Librarian, Distributed eLibrary, Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar, for validating the search strategy; and Hidenori Miyagawa, Visual Design Specialist Distributed eLibrary, Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar for advising and helping format the images and tables.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.748069/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ICT, Internet and communication technologies; JBI, Joanna briggs institute reviewer manual; NQF, national quality forum; PRISMA-ScR, Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews; WHO, World health organization.

References

1. Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) 3:171–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2

2. Chatterjee SS, Barikar CM, Mukherjee A. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pre-existing mental health problems. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102071. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102071

3. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

4. Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2019686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686

5. Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. (2020) 180:817–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562

6. Taylor S, Paluszek MM, Rachor GS, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. Substance use and abuse, COVID-19-related distress, and disregard for social distancing: a network analysis. Addict Behav. (2021) 114:106754. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106754

7. Dozois DJA. Anxiety and depression in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Can Psychol. (2021) 62:136–42. doi: 10.1037/cap0000251

8. Cowan KE, McKean AJ, Gentry MT, Hilty DM. Barriers to use of telepsychiatry: clinicians as gatekeepers. Mayo Clin Proc. (2019) 94:2510–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.04.018

9. McGinty KL, Saeed SA, Simmons SC, Yildirim Y. Telepsychiatry and e-Mental health services: potential for improving access to mental health care. Psychiatr Q. (2006) 77:335–42. doi: 10.1007/s11126-006-9019-6

10. Acharibasam JW, Wynn R. Telemental health in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Telemed Appl. (2018) 2018:9602821. doi: 10.1155/2018/9602821

11. Shore JH, Yellowlees P, Caudill R, Johnston B, Turvey C, Mishkind M, et al. Best practices in videoconferencing-based telemental health april 2018. Telemed J E Health. (2018) 24:827–32. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2018.0237

12. Langarizadeh M, Tabatabaei MS, Tavakol K, Naghipour M, Rostami A, Moghbeli F. Telemental health care, an effective alternative to conventional mental care: a systematic review. Acta Inform Med. (2017) 25:240–6. doi: 10.5455/aim.2017.25.240-246

13. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). What is Telemental Health. (2021). Available online at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/what-is-telemental-health/ (accessed July 4, 2021).

14. Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2018) 18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

15. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

16. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews, Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer Manual. Adelaide, SA: The Joanna Briggs Institute (2017).

17. Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2015) 13:141–6. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

18. White H, Albers B, Gaarder M, Kornør H, Littell J, Marshall Z, et al. Guidance for producing a Campbell evidence and gap map. Campbell Syst Rev. (2020) 16:e1125. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1125

19. Open Science Framework. OSF Home. (2020). Available online at: https://osf.io/dashboard (accessed June 2, 2020).

20. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

21. Beller EM, Glasziou PP, Altman DG, Hopewell S, Bastian H, Chalmers I, et al. PRISMA for abstracts: reporting systematic reviews in journal and conference abstracts. PLoS Med. (2013) 10:e1001419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001419

22. Peña-López I. Guide to Measuring Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in Education. Montreal, QC; UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2009).

23. Doraiswamy S, Jithesh A, Mamtani R, Abraham A, Cheema S. Telehealth use in geriatrics care during the COVID-19 pandemic—a scoping review and evidence synthesis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1755. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041755

24. Campion J, Javed A, Sartorius N, Marmot M. Addressing the public mental health challenge of COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:657–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30240-6

25. Shi L, Lu ZA, Que JY, Huang XL, Liu L, Ran MS, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2014053. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053

26. Doraiswamy S, Abraham A, Mamtani R, Cheema S. Use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e24087. doi: 10.2196/24087

27. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

28. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: APA (2013).

29. National Quality Forum. Creating a Framework to Support Measure Development for Telehealth. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum (2017). Available online at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2017/08/Creating_a_Framework_to_Support_Measure_Development_for_Telehealth.aspx

30. Nettleton S, Burrows R, O'Malley L. The mundane realities of the everyday lay use of the internet for health, and their consequences for media convergence. Sociol Health Illn. (2005) 27:972–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00466.x

31. Dol J, Tutelman PR, Chambers CT, Barwick M, Drake EK, Parker JA, et al. Health researchers' use of social media: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. (2019) 21:e13687. doi: 10.2196/13687

32. Deng Y, Stoehr M, Denecke K editors. Retrieving Attitudes: Sentiment Analysis From Clinical Narratives. Leipzig: MedIR@ SIGIR (2014).

33. Denecke K, Deng Y. Sentiment analysis in medical settings: new opportunities and challenges. Artif Intell Med. (2015) 64:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2015.03.006

34. Sequeira A, Alozie A, Fasteau M, Lopez AK, Sy J, Turner KA, et al. Transitioning to virtual programming amidst COVID-19 outbreak. Couns Psychol Q. (2020) 1–16. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2020.1777940

35. Ameis SH, Lai MC, Mulsant BH, Szatmari P. Coping, fostering resilience, and driving care innovation for autistic people and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Mol Autism. (2020) 11:61. doi: 10.1186/s13229-020-00365-y

36. Childs AW, Unger A, Li L. Rapid design and deployment of intensive outpatient group-based psychiatric care using telehealth during COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2020) 27:1420–4. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa138

37. Harris M, Johnson S, Mackin S, Saitz R, Walley AY, Taylor JL. Low barrier tele-buprenorphine in the time of COVID-19: a case report. J Addict Med. (2020) 14:e136–8. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000682

38. Hau YS, Kim JK, Hur J, Chang MC. How about actively using telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Med Syst. (2020) 44:108. doi: 10.1007/s10916-020-01580-z

39. Humer E, Pieh C, Kuska M, Barke A, Doering BK, Gossmann K, et al. Provision of psychotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic among Czech, German and Slovak psychotherapists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4811. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134811

40. Kola L. Global mental health and COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:655–7. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30235-2

41. Marra DE, Hamlet KM, Bauer RM, Bowers D. Validity of teleneuropsychology for older adults in response to COVID-19: a systematic and critical review. Clin Neuropsychol. (2020):34:1411–52. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2020.1769192

42. Naal H, Whaibeh E, Mahmoud H. Guidelines for primary health care-based telemental health in a low-to middle-income country: the case of Lebanon. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2020) 33:170–8. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1766867

43. Nagata JM. Rapid scale-up of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic and implications for subspecialty care in rural areas. J Rural Health. (2020) 37:145. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12433

44. Perrin PB, Rybarczyk BD, Pierce BS, Jones HA, Shaffer C, Islam L. Rapid telepsychology deployment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a special issue commentary and lessons from primary care psychology training. J Clin Psychol. (2020) 76:1173–85. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22969

45. Peterson RK, Ludwig NN, Jashar DT. A case series illustrating the implementation of a novel tele-neuropsychology service model during COVID-19 for children with complex medical and neurodevelopmental conditions: a companion to Pritchard et al., 2020. Clin Neuropsychol. (2020) 35:99–114. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2020.1799075

46. Ping NPT, Shoesmith WD, James S, Nor Hadi NM, Yau EKB, Lin LJ. Ultra brief psychological interventions for COVID-19 pandemic: introduction of a locally-adapted brief intervention for mental health and psychosocial support service. Malays J Med Sci. (2020) 27:51–6. doi: 10.21315/mjms2020.27.2.6

47. Probst T, Stippl P, Pieh C. Changes in provision of psychotherapy in the early weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown in Austria. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3815. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113815

48. Abbass A, Elliott J. Emotion-focused and video-technology considerations in the COVID-19 crisis. Couns Psychol Q. (2020) 1–13. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2020.1784096

49. Roncero C, Garcia-Ullan L, de la Iglesia-Larrad JI, Martin C, Andres P, Ojeda A, et al. The response of the mental health network of the Salamanca area to the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of the telemedicine. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 291:113252. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113252

50. Sorinmade OA, Kossoff L, Peisah C. COVID-19 and telehealth in older adult psychiatry-opportunities for now and the future. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 35:1427–30. doi: 10.1002/gps.5383

51. Stewart RW, Orengo-Aguayo R, Young J, Wallace MM, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of a telehealth service delivery model for treating childhood posttraumatic stress: a community-based, open pilot trial of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 30:274–89. doi: 10.1037/int0000225

52. Wade SL, Gies LM, Fisher AP, Moscato EL, Adlam AR, Bardoni A, et al. Telepsychotherapy with children and families: lessons gleaned from two decades of translational research. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 30:332–47. doi: 10.1037/int0000215

53. Whaibeh E, Mahmoud H, Naal H. Telemental health in the context of a pandemic: the COVID-19 experience. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. (2020) 7:198–202. doi: 10.1007/s40501-020-00210-2

54. Whelan P, Stockton-Powdrell C, Jardine J, Sainsbury J. Comment on “digital mental health and COVID-19: using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow”: a UK perspective. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7:e19547. doi: 10.2196/19547

55. Wind TR, Rijkeboer M, Andersson G, Riper H. The COVID-19 pandemic: the 'black swan' for mental health care and a turning point for e-health. Internet Interv. (2020) 20:100317. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100317

56. Zhang C, Zhu K, Li D, Voon V, Sun B. Deep brain stimulation telemedicine for psychiatric patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Stimul. (2020) 13:1263–4. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2020.06.011

57. Galea-Singer S, Newcombe D, Farnsworth-Grodd V, Sheridan J, Adams P, Walker N. Challenges of virtual talking therapies for substance misuse in New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic: an opinion piece. N Z Med J. (2020) 133:104–11.

58. Bennett CB, Ruggero CJ, Sever AC, Yanouri L. eHealth to redress psychotherapy access barriers both new and old: a review of reviews and meta-analyses. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 2:188–207. doi: 10.1037/int0000217

59. Hser YI, Mooney LJ. Integrating telemedicine for medication treatment for opioid use disorder in rural primary care: beyond the COVID pandemic. J Rural Health. (2020) 37:246–8. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12489

60. McBeath AG, du Plock S, Bager-Charleson S. The challenges and experiences of psychotherapists working remotely during the coronavirus pandemic. Couns Psychother Res. (2020) 20:394–405. doi: 10.1002/capr.12326

61. Banducci AN, Weiss NH. Caring for patients with posttraumatic stress and substance use disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. (2020) 12:S113–4. doi: 10.1037/tra0000824

62. Rodriguez KA. Maintaining treatment integrity in the face of crisis: a treatment selection model for transitioning direct ABA services to telehealth. Behav Anal Pract. (2020) 13:1–8. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/phtgv

63. Zhang M, Smith HE. Digital tools to ameliorate psychological symptoms associated with COVID-19: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e19706. doi: 10.2196/19706

64. Canady VA. Virtual clinic to assist patients with urgent psychiatric care. Mental Health Weekly. (2020) 30:7. doi: 10.1002/mhw.32338

65. Chen JA, Chung WJ, Young SK, Tuttle MC, Collins MB, Darghouth SL, et al. COVID-19 and telepsychiatry: early outpatient experiences and implications for the future. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2020) 66:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.07.002

66. DeLuca JS, Andorko ND, Chibani D, Jay SY, Rakhshan Rouhakhtar PJ, Petti E, et al. Telepsychotherapy with youth at clinical high risk for psychosis: clinical issues and best practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychothe Integr. (2020) 30:304–31. doi: 10.1037/int0000211

67. Isaacs Russell G. Remote working during the pandemic: a Q&A with gillian issacs russell: questions from the editor and editorial board of the british journal of psychotherapy. Br J Psychother. (2020) 36:364–74. doi: 10.1111/bjp.12581

68. Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Math SB. Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: time to optimize the potential of telepsychiatric aftercare clinic to ensure the continuity of care. Indian J Psychiatry. (2020) 62:320–1. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_236_20

69. O'Brien M, McNicholas F. The use of telepsychiatry during COVID-19 and beyond. Ir J Psychol Med. (2020) 37:250–5. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.54

70. Payne L, Flannery H, Kambakara Gedara C, Daniilidi X, Hitchcock M, Lambert D, et al. Business as usual? Psychological support at a distance. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2020) 25:672–86. doi: 10.1177/1359104520937378

71. Rosic T, Lubert S, Samaan Z. Virtual psychiatric care fast-tracked: reflections inspired by the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Bull. (2020) 1–8. doi: 10.1192/bjb.2020.97

72. Smith K, Ostinelli E, Macdonald O, Cipriani A. COVID-19 and telepsychiatry: development of evidence-based guidance for clinicians. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7:e21108. doi: 10.2196/21108

73. Weissman RS, Bauer S, Thomas JJ. Access to evidence-based care for eating disorders during the COVID-19 crisis. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:369–76. doi: 10.1002/eat.23279

74. Martin JN, Millán F, Campbell LF. Telepsychology practice: primer and first steps. Pract Innovat. (2020) 5:114–27. doi: 10.1037/pri0000111

75. Haxhihamza K, Arsova S, Bajraktarov S, Kalpak G, Stefanovski B, Novotni A, et al. Patient satisfaction with use of telemedicine in university clinic of psychiatry: skopje, north macedonia during COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J E Health. (2020) 27:464–7. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0256

76. Kozloff N, Mulsant BH, Stergiopoulos V, Voineskos AN. The COVID-19 global pandemic: implications for people with schizophrenia and related disorders. Schizophr Bull. (2020) 46:752–7. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa051

77. Mosolov SN. [Problems of mental health in the situation of COVID-19 pandemic]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. (2020) 120:7–15. doi: 10.17116/jnevro20201200517

78. Medalia A, Lynch DA, Herlands T. Telehealth conversion of serious mental illness recovery services during the COVID-19 crisis. Psychiatr Serv. (2020) 71:872. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.71705

79. Cowan A, Johnson R, Close H. Telepsychiatry in psychotherapy practice. Innov Clin Neurosci. (2020) 17:23–6.

80. Crowe M, Inder M, Farmar R, Carlyle D. Delivering psychotherapy by video conference in the time of COVID-19: some considerations. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 28:751–2. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12659

81. de Girolamo G, Cerveri G, Clerici M, Monzani E, Spinogatti F, Starace F, et al. mental health in the coronavirus disease 2019 emergency-the Italian response. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:974–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1276

82. Alexopoulos AR, Hudson JG, Otenigbagbe O. The use of digital applications and COVID-19. Community Ment Health J. (2020) 56:1202–3. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00689-2

83. Khanna R, Forbes M. Telepsychiatry as a public health imperative: slowing COVID-19. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2020) 54:758. doi: 10.1177/0004867420924480

84. Datta N, Derenne J, Sanders M, Lock JD. Telehealth transition in a comprehensive care unit for eating disorders: challenges and long-term benefits. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:1774–9. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/hrbs4

85. Rosen CS, Glassman LH, Morl LA. Telepsychotherapy during a pandemic: a traumatic stress perspective. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 30:174–87. doi: 10.1037/int0000221

86. Corruble E. A viewpoint from Paris on the COVID-19 pandemic: a necessary turn to telepsychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. (2020) 81:20com13361. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20com13361

87. Bocher R, Jansen C, Gayet P, Gorwood P, Laprévote V. Réactivité et pérennité des soins psychiatriques en France à lépreuve du COVID-19. Encephale. (2020) 46:S81–S4. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2020.05.004

88. Chin HP, Palchik G. Telepsychiatry in the age of COVID: some ethical considerations. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. (2020) 30:37–41. doi: 10.1017/s0963180120000523

89. Stoll J, Sadler JZ, Trachsel M. The ethical use of telepsychiatry in the Covid-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:665. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00665

90. Thomas RK, Suleman R, Mackay M, Hayer L, Singh M, Correll CU, et al. Adapting to the impact of COVID-19 on mental health: an international perspective. J Psychiatry Neurosci. (2020) 45:229–33. doi: 10.1503/jpn.200076

91. Viswanathan R, Myers MF, Fanous AH. Support groups and individual mental health care via video conferencing for frontline clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychosomatics. (2020) 61:538–43. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.06.014

92. Wells SY, Morland LA, Wilhite ER, Grubbs KM, Rauch SAM, Acierno R, et al. Delivering prolonged exposure therapy via videoconferencing during the COVID-19 pandemic: an overview of the research and special considerations for providers. J Trauma Stress. (2020) 33:380–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.22573

93. Caver KA, Shearer EM, Burks DJ, Perry K, De Paul NF, McGinn MM, et al. Telemental health training in the veterans administration puget sound health care system. J Clin Psychol. (2020) 76:1108–24. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22797

94. Balcombe L, De Leo D. An integrated blueprint for digital mental health services amidst COVID-19. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7:e21718. doi: 10.2196/21718

95. Anton MT, Ridings LE, Gavrilova Y, Bravoco O, Ruggiero KJ, Davidson TM. Transitioning a technology-assisted stepped-care model for traumatic injury patients to a fully remote model in the age of COVID-19. Couns Psychol Q. (2020) 1–12. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2020.1785393

96. Figueroa CA, Aguilera A. The need for a mental health technology revolution in the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:523. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00523

97. Gould CE, Hantke NC. Promoting technology and virtual visits to improve older adult mental health in the face of COVID-19. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 28:889–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.011

98. Kanzler KE, Ogbeide S. Addressing trauma and stress in the COVID-19 pandemic: challenges and the promise of integrated primary care. Psychol Trauma. (2020) 12:S177–9. doi: 10.1037/tra0000761

99. Merchant R, Torous J, Rodriguez-Villa E, Naslund JA. Digital technology for management of severe mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2020) 33:501–7. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000626

100. Ojha R, Syed S. Challenges faced by mental health providers and patients during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic due to technological barriers. Internet Interv. (2020) 21:100330. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100330

101. Aboujaoude E, Gega L, Parish MB, Hilty DM. Editorial: digital interventions in mental health: current status and future directions. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:111. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00111

102. Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics. (2020) 174:819–20. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456

103. Hewitt KC, Rodgin S, Loring DW, Pritchard AE, Jacobson LA. Transitioning to telehealth neuropsychology service: considerations across adult and pediatric care settings. Clin Neuropsychol. (2020) 34:1335–51. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2020.1811891

104. Rorai V, Perry TE. An innovative telephone outreach program to seniors in Detroit, a City facing dire consequences of COVID-19. J Gerontol Soc Work. (2020) 63:713–6. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2020.1793254

105. Naarding P, Oude Voshaar RC, Marijnissen RM. COVID-19: clinical challenges in dutch geriatric psychiatry. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 28:839–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.019

106. Bilder RM, Postal KS, Barisa M, Aase DM, Cullum CM, Gillaspy SR, et al. Inter organizational practice committee recommendations/guidance for teleneuropsychology in response to the COVID-19 pandemicdagger. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. (2020) 35:647–59. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acaa046

107. Danilewitz M, Ainsworth NJ, Bahji A, Chan P, Rabheru K. Virtual psychiatric care for older adults in the age of COVID-19: challenges and opportunities. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 35:1468–9. doi: 10.1002/gps.5372

108. Fonagy P, Campbell C, Truscott A, Fuggle P. Debate: mentalising remotely - the AFNCCF's adaptations to the coronavirus crisis. Child Adolesc Ment Health. (2020) 25:178–9. doi: 10.1111/camh.12404

109. Gautam M, Thakrar A, Akinyemi E, Mahr G. Current and future challenges in the delivery of mental healthcare during COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med. (2020) 2:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00348-3

110. Pinto da Costa M. Can social isolation caused by physical distance in people with psychosis be overcome through a phone pal? Eur Psychiatry. (2020) 63:e61. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.53

111. Pritchard AE, Sweeney K, Salorio CF, Jacobson LA. Pediatric neuropsychological evaluation via telehealth: novel models of care. Clin Neuropsychol. (2020) 34:1367–79. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2020.1806359

112. Razai MS, Oakeshott P, Kankam H, Galea S, Stokes-Lampard H. Mitigating the psychological effects of social isolation during the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. (2020) 369:m1904. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1904

113. Zhai Y. A call for addressing barriers to telemedicine: health disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychother Psychosom. (2020) 90:1–3. doi: 10.1159/000509000

114. Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Rethinking online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 50:102015. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102015

115. Lepkowsky CM. Telehealth reimbursement allows access to mental health care during COVID-19. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 28:898–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.008

116. Ramtekkar U, Bridge J, Thomas G, Butter E, Reese J, Logan E, et al. Pediatric telebehavioral health: a transformational shift in care delivery in the era of COVID-19. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7:e20157. doi: 10.2196/20157

117. Endale T, St Jean N, Birman D. COVID-19 and refugee and immigrant youth: a community-based mental health perspective. Psychol Trauma. (2020) 12:S225–7. doi: 10.1037/tra0000875

118. Gurwitch RH, Salem H, Nelson MM, Comer JS. Leveraging parent-child interaction therapy and telehealth capacities to address the unique needs of young children during the COVID-19 public health crisis. Psychol Trauma. (2020) 12:S82–4. doi: 10.1037/tra0000863

119. MacMullin K, Jerry P, Cook K. Psychotherapist experiences with telepsychotherapy: pre COVID-19 lessons for a post COVID-19 world. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 30:248–64. doi: 10.1037/int0000213

120. Usman M, Fahy S. Coping with the COVID-19 crisis: an overview of service adaptation and challenges encountered by a rural psychiatry of later life (POLL) team. Ir J Psychol Med. (2020) 90:1–5. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.86

121. Chherawala N, Gill S. Up-to-date review of psychotherapy via videoconference: implications and recommendations for the RANZCP psychotherapy written case during the COVID-19 pandemic. Australas Psychiatry. (2020) 28:517–20. doi: 10.1177/1039856220939495

122. Feijt M, de Kort Y, Bongers I, Bierbooms J, Westerink J, W IJ. Mental health care goes online: practitioners' experiences of providing mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020) 23:860–4. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0370

123. Haque SN. Telehealth beyond COVID-19. Psychiatr Serv. (2020) 72:100–3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000368

124. Ramalho R, Adiukwu F, Gashi Bytyci D, El Hayek S, Gonzalez-Diaz JM, Larnaout A, et al. Telepsychiatry and healthcare access inequities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 53:102234. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102234

125. Schuh Teixeira AL, Spadini AV, Pereira-Sanchez V, Ojeahere MI, Morimoto K, Chang A, et al. The urge to implement and expand telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 crisis: early career psychiatrists' perspective. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. (2020) 13:174–5. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.06.001

126. Soron TR, Shariful Islam SM, Ahmed HU, Ahmed SI. The hope and hype of telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e50. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30260-1

127. Watts S, March A, Bouchard S, Gosselin P, Langlois F, Belleville G, et al. Telepsychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder: impact on the working alliance. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 30:208–25. doi: 10.1037/int0000223

128. Yellowlees P, Nakagawa K, Pakyurek M, Hanson A, Elder J, Kales HC. Rapid conversion of an outpatient psychiatric clinic to a 100% virtual telepsychiatry clinic in response to COVID-19. Psychiatr Serv. (2020) 71:749–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000230

129. Zulfic Z, Liu D, Lloyd C, Rowan J, Schubert KO. Is telepsychiatry care a realistic option for community mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2020) 54:1228. doi: 10.1177/0004867420937788

130. Haun MW, Hoffmann M, Tönnies J, Dinger U, Hartmann M, Friederich HC. Realtime video consultations by psychotherapists in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: effectiveness, mode of delivery and first experiences from a German feasibility study and with a routine service option in hospitals. Psychotherapeut. (2020) 65:291–6. doi: 10.1007/s00278-020-00438-6

131. Cosic K, Popovic S, Sarlija M, Kesedzic I. Impact of human disasters and COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: potential of digital psychiatry. Psychiatr Danub. (2020) 32:25–31. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2020.25

132. Hames JL, Bell DJ, Perez-Lima LM, Holm-Denoma JM, Rooney T, Charles NE, et al. Navigating uncharted waters: considerations for training clinics in the rapid transition to telepsychology and telesupervision during COVID-19. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 30:348–65. doi: 10.1037/int0000224

133. Thompson-de Benoit A, Kramer U. Work with emotions in remote psychotherapy in the time of Covid-19: a clinical experience. Couns Psychol Q. (2020) 1–9. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2020.1770696

134. Barney A, Buckelew S, Mesheriakova V, Raymond-Flesch M. The COVID-19 pandemic and rapid implementation of adolescent and young adult telemedicine: challenges and opportunities for innovation. J Adolesc Health. (2020) 67:164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.006

135. Sklar M, Reeder K, Carandang K, Ehrhart MG, Aarons GA. An observational study of the impact of COVID-19 and the transition to telehealth on community mental health center providers. Res Sq. (2020) rs.3.rs:48767. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-48767/v1

136. Torous J, Keshavan M. COVID-19, mobile health and serious mental illness. Schizophr Res. (2020) 218:36–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.04.013

137. Taylor CB, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Graham AK. Digital technology can revolutionize mental health services delivery: the COVID-19 crisis as a catalyst for change. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:1155–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.23300

138. Jain N, Jayaram M. Comment on “digital mental health and COVID-19: using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow”. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7:e23023. doi: 10.2196/23023

139. Shore JH, Schneck CD, Mishkind MC. Telepsychiatry and the coronavirus disease 2019 Pandemic-current and future outcomes of the rapid virtualization of psychiatric care. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:1211–2. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1643

140. Tullio V, Perrone G, Bilotta C, Lanzarone A, Argo A. Psychological support and psychotherapy via digital devices in Covid-19 emergency time: some critical issues. Med Leg J. (2020) 88:73–6. doi: 10.1177/0025817220926942

141. Lopez-Pelayo H, Aubin HJ, Drummond C, Dom G, Pascual F, Rehm J, et al. “The post-COVID era”: challenges in the treatment of substance use disorder (SUD) after the pandemic. BMC Med. (2020) 18:241. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01693-9

142. Riegler LJ, Raj SP, Moscato EL, Narad ME, Kincaid A, Wade SL. Pilot trial of a telepsychotherapy parenting skills intervention for veteran families: implications for managing parenting stress during COVID-19. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 30:290–303. doi: 10.1037/int0000220

143. Thirthalli J, Manjunatha N, Math SB. Unmask the mind! importance of video consultations in psychiatry during COVID-19 pandemic. Schizophr Res. (2020) 222:482–3. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.06.005

144. Wood SM, White K, Peebles R, Pickel J, Alausa M, Mehringer J, et al. Outcomes of a rapid adolescent telehealth scale-up during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. (2020) 67:172–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.025

145. Krzystanek M, Matuszczyk M, Krupka-Matuszczyk I, Kozmin-Burzynska A, Segiet S, Przybylo J. Tele-visit (e-visit) during the epidemic crisis: recommendations for conducting online visits in psychiatric care. Psychiatria. (2020) 17:61–5. doi: 10.5603/PSYCH.2020.0011

146. Sharma A, Sasser T, Schoenfelder Gonzalez E, Vander Stoep A, Myers K. Implementation of home-based telemental health in a large child psychiatry department during the COVID-19 crisis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. (2020) 30: 404–13. doi: 10.1089/cap.2020.0062

147. Looi JC, Pring W. Private metropolitan telepsychiatry in Australia during Covid-19: current practice and future developments. Australas Psychiatry. (2020) 28 508–10. doi: 10.1177/1039856220930675

148. Alavi Z Haque R Felzer-Kim IT Lewicki T Haque A Mormann M. Implementing COVID-19 mitigation in the community mental health setting: march 2020 and lessons learned. Community Ment Health J. (2020) 57:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00677-6

149. Canady VA. Psychiatrists, patients favor telemedicine; challenges exist. Ment Health Wkly. (2020) 30:4–5. doi: 10.1002/mhw.32365

150. Hom MA, Weiss RB, Millman ZB, Christensen K, Lewis EJ, Cho S, et al. Development of a virtual partial hospital program for an acute psychiatric population: lessons learned and future directions for telepsychotherapy. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 30:366–82. doi: 10.1037/int0000212

151. Ben-Zeev D, Buck B, Meller S, Hudenko WJ, Hallgren KA. Augmenting evidence-based care with a texting mobile interventionist: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv. (2020) 71:1218–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000239

152. Colle R, Ait Tayeb AEK, de Larminat D, Commery L, Boniface B, Lasica PA, et al. Short-term acceptability by patients and psychiatrists of the turn to psychiatric teleconsultation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2020) 74:443–4. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13081

153. Franchini L, Ragone N, Seghi F, Barbini B, Colombo C. Mental health services for mood disorder outpatients in Milan during COVID-19 outbreak: the experience of the health care providers at San Raffaele hospital. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 292:113317. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113317

154. Matheson BE, Bohon C, Lock J. Family-based treatment via videoconference: clinical recommendations for treatment providers during COVID-19 and beyond. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:1142–54. doi: 10.1002/eat.23326

155. Millar C, Campbell S, Fisher P, Hutton J, Morgan A, Cherry MG. Cancer and COVID-19: Patients' and psychologists' reflections regarding psycho-oncology service changes. Psychooncology. (2020) 29:1402–3. doi: 10.1002/pon.5461

156. Reay RE, Looi JC, Keightley P. Telehealth mental health services during COVID-19: summary of evidence and clinical practice. Australas Psychiatry. (2020) 28:514–6. doi: 10.1177/1039856220943032

157. Schieltz KM, Wacker DP. Functional assessment and function-based treatment delivered via telehealth: a brief summary. J Appl Behav Anal. (2020) 53:1242–58. doi: 10.1002/jaba.742

158. Van Orden KA, Bower E, Lutz J, Silva C, Gallegos AM, Podgorski CA, et al. Strategies to promote social connections among older adults during 'social distancing' restrictions. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 29:816–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.004

159. Waller G, Pugh M, Mulkens S, Moore E, Mountford VA, Carter J, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy in the time of coronavirus: clinician tips for working with eating disorders via telehealth when face-to-face meetings are not possible. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:1132–41. doi: 10.1002/eat.23289

160. Van Daele T, Karekla M, Kassianos AP, Compare A, Haddouk L, Salgado J, et al. Recommendations for policy and practice of telepsychotherapy and e-mental health in Europe and beyond. J Psychothe. Integr. (2020) 30:160–73. doi: 10.1037/int0000218

161. Miermont-Schilton D, Richard F. The current sociosanitary coronavirus crisis: remote psychoanalysis by skype or telephone. Int J Psychoanal. (2020) 3:572–9. doi: 10.1080/00207578.2020.1773633

162. Seifert J, Heck J, Eckermann G, Singer M, Bleich S, Grohmann R, et al. [Psychopharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic]. Nervenarzt. (2020) 91:604–10. doi: 10.1007/s00115-020-00939-4

163. Svenson K. Teleanalytic therapy in the era of Covid-19: dissociation in the countertransference. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. (2020) 68:447–54. doi: 10.1177/0003065120938772

164. Warnock-Parkes E, Wild J, Thew GR, Kerr A, Grey N, Stott R, et al. Treating social anxiety disorder remotely with cognitive therapy. Cogn Behav Ther. (2020) 13:e30. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X2000032X

165. Sansom-Daly UM, Bradford N. Grappling with the 'human' problem hiding behind the technology: telehealth during and beyond COVID-19. Psychooncology. (2020) 29:1404–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.5462

166. Békés V, Aafjes-van Doorn K, Prout TA, Hoffman L. Stretching the analytic frame: analytic therapists' experiences with remote therapy during COVID-19. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. (2020) 68:437–46. doi: 10.1177/0003065120939298

167. Ronen-Setter IH, Cohen E. Becoming “teletherapeutic”: harnessing accelerated experiential dynamic psychotherapy (AEDP) for challenges of the Covid-19 era. J Contemp Psychother. (2020) 50:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10879-020-09462-8

168. Olwill C, Mc Nally D, Douglas L. Psychiatrist experience of remote consultations by telephone in an outpatient psychiatric department during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ir J Psychol Med. (2020) 38:1–8. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.51

169. Pierce BS, Perrin PB, Tyler CM, McKee GB, Watson JD. The COVID-19 telepsychology revolution: a national study of pandemic-based changes in U.S. mental health care delivery. Am Psychol. (2020) 76:14–25. doi: 10.1037/amp0000722

170. Wang L, Fagan C, Yu CL. Popular mental health apps (MH apps) as a complement to telepsychotherapy: guidelines for consideration. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 30:265–73. doi: 10.1037/int0000204

171. Patel S, Gannon A, Dolan C, McCarthy G. Telehealth in psychiatry of old age: ordinary care in extraordinary times in rural North-West Ireland. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 28:1009–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.024

172. Samuels EA, Clark SA, Wunsch C, Jordison Keeler LA, Reddy N, Vanjani R, et al. Innovation during COVID-19: improving addiction treatment access. J Addict Med. (2020) 14:e8–9. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000685

173. Sousa A, Karia S. Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: some clinical, public health, and ethical dilemmas. Indian J Public Health. (2020) 64:S245–6. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_511_20

174. Sullivan AB, Kane A, Roth AJ, Davis BE, Drerup ML, Heinberg LJ. The COVID-19 crisis: a mental health perspective and response using telemedicine. J Patient Exp. (2020) 7:295–301. doi: 10.1177/2374373520922747

175. Wright JH, Caudill R. Remote treatment delivery in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychother Psychosom. (2020) 89:130–2. doi: 10.1159/000507376

176. Murphy R, Calugi S, Cooper Z, Dalle Grave R. Challenges and opportunities for enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) in light of COVID-19. Cogn Behav Ther. (2020) 13:e14. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X20000161

177. de Brouwer H, Faure K, Goze T. [Institutional Psychotherapy during confinement situation: adaptation of the therapeutic setting in a day hospital. Towards a virtual mental institution]. Ann Med Psychol. (2020) 178:722–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amp.2020.05.005

178. Chenneville T, Schwartz-Mette R. Ethical considerations for psychologists in the time of COVID-19. Am Psychol. (2020) 75:644–54. doi: 10.1037/amp0000661

179. Burgess C, Miller CJ, Franz A, Abel EA, Gyulai L, Osser D, et al. Practical lessons learned for assessing and treating bipolar disorder via telehealth modalities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bipolar Disord. (2020) 22:556–7. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12969

180. Moring JC, Dondanville KA, Fina BA, Hassija C, Chard K, Monson C, et al. Cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder via telehealth: practical considerations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Trauma Stress. (2020) 33:371–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.22544

181. Ragavan MI, Culyba AJ, Muhammad FL, Miller E. Supporting adolescents and young adults exposed to or experiencing violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. (2020) 67:18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.04.011

182. Zarghami A, Farjam M, Fakhraei B, Hashemzadeh K, Yazdanpanah MH. A report of the telepsychiatric evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 patients. Telemed J E Health. (2020) 26:1461–5. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0125

183. Imperatori C, Dakanalis A, Farina B, Pallavicini F, Colmegna F, Mantovani F, et al. Global storm of stress-related psychopathological symptoms: a brief overview on the usefulness of virtual reality in facing the mental health impact of COVID-19. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020) 23:782-8. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0339

184. El Morr C, Ritvo P, Ahmad F, Moineddin R, Team MVC. Effectiveness of an 8-week web-based mindfulness virtual community intervention for university students on symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7:e18595. doi: 10.2196/18595

185. Giordano F, Scarlata E, Baroni M, Gentile E, Puntillo F, Brienza N, et al. Receptive music therapy to reduce stress and improve wellbeing in Italian clinical staff involved in COVID-19 pandemic: a preliminary study. Arts Psychother. (2020) 70:101688. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2020.101688

186. Jobes DA, Crumlish JA, Evans AD. The COVID-19 pandemic and treating suicidal risk: the telepsychotherapy use of CAMS. J Psychother Integr. (2020) 2:226–37. doi: 10.1037/int0000208

187. Marshall JM, Dunstan DA, Bartik W. The role of digital mental health resources to treat trauma symptoms in Australia during COVID-19. Psychol Trauma. (2020) 12:S269–71. doi: 10.1037/tra0000627

188. Sammons MT, VandenBos GR, Martin JN. Psychological practice and the COVID-19 crisis: a rapid response survey. J Health Serv Psychol. (2020) 46:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s42843-020-00013-2

189. Chang BP, Kessler RC, Pincus HA, Nock MK. Digital approaches for mental health in the age of covid-19. BMJ. (2020) 369:m2541. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2541

190. Goodman-Casanova JM, Dura-Perez E, Guzman-Parra J, Cuesta-Vargas A, Mayoral-Cleries F. Telehealth home support during COVID-19 confinement for community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia: survey study. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e19434. doi: 10.2196/19434

191. Kwon CY, Kwak HY, Kim JW. Using mind-body modalities via telemedicine during the COVID-19 crisis: cases in the Republic of Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4477. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124477

192. Gaebel W, Stricker J. E-mental health options in the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2020) 74:441–2. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13079

193. Marra DE, Hoelzle JB, Davis JJ, Schwartz ES. Initial changes in neuropsychologists clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study. Clin Neuropsychol. (2020) 34:1251–66. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2020.1800098

194. Dolev-Amit T, Leibovich L, Zilcha-Mano S. Repairing alliance ruptures using supportive techniques in telepsychotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Couns Psychol Q. (2020). doi: 10.1080/09515070.2020.1777089

195. McGrath J. ADHD and Covid-19: current roadblocks and future opportunities. Ir J Psychol Med. (2020) 37:204–11. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.53

196. Fagiolini A, Cuomo A, Frank E. COVID-19 diary from a psychiatry department in Italy. J Clin Psychiatry. (2020) 81 20com13357. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20com13357

197. Mattar S, Piwowarczyk LA. COVID-19 and U.S.-based refugee populations: commentary. Psychol Trauma. (2020) 12:S228–9. doi: 10.1037/tra0000602

198. Graell M, Moron-Nozaleda MG, Camarneiro R, Villasenor A, Yanez S, Munoz R, et al. Children and adolescents with eating disorders during COVID-19 confinement: difficulties and future challenges. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2020) 28:864–70. doi: 10.1002/erv.2763

199. Thome J, Coogan AN, Fischer M, Tucha O, Faltraco F. Challenges for mental health services during the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak in Germany. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2020) 74:407. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13019

200. Kannarkat JT, Smith NN, McLeod-Bryant SA. Mobilization of telepsychiatry in response to COVID-19-moving toward 21st century access to care. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2020) 47:489–91. doi: 10.1007/s10488-020-01044-z

201. Xiang YT, Zhao N, Zhao YJ, Liu Z, Zhang Q, Feng Y, et al. An overview of the expert consensus on the mental health treatment and services for major psychiatric disorders during COVID-19 outbreak: China's experiences. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:2265–70. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.47419

202. Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Araya R, Marsch LA, Unützer J, Patel V, et al. Digital technology for treating and preventing mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries: a narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry. (2017) 4:486–500. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30096-2

203. Carter H, Araya R, Anjur K, Deng D, Naslund JA. The emergence of digital mental health in low-income and middle-income countries: a review of recent advances and implications for the treatment and prevention of mental disorders. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 133:223–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.016

204. Augusterfer EF, O'Neal CR, Martin SW, Sheikh TL, Mollica RF. The role of telemental health, tele-consultation, and tele-supervision in post-disaster and low-resource settings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2020) 22:85. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01209-5

205. Chin HP, Palchik G. Telepsychiatry in the age of COVID: some ethical considerations. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. (2021) 30:37–41. doi: 10.1017/S0963180120000523

206. Scott JA. I'm virtually a psychiatrist: problems with telepsychiatry in training. Acad Psychiatry. (2021) 9:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s40596-021-01532-w

207. Sabin JE, Skimming K. A framework of ethics for telepsychiatry practice. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2015) 27:490–5. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1094034

208. Sansom-Daly UM, Wakefield CE, McGill BC, Wilson HL, Patterson P. Consensus among international ethical guidelines for the provision of videoconferencing-based mental health treatments. JMIR Ment Health. (2016) 3:e17. doi: 10.2196/mental.5481

209. Mishkind MC, Shore JH, Schneck CD. Telemental health response to the COVID-19 pandemic: virtualization of outpatient care now as a pathway to the future. Telemed e-Health. (2020) 27:709–11. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0303

210. Dorsey ER, Okun MS, Bloem BR. Care, convenience, comfort, confidentiality, and contagion: the 5 C's that will shape the future of telemedicine. J Parkinsons Dis. (2020) 10:893–7. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202109

211. Myers CR. Using telehealth to remediate rural mental health and healthcare disparities. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2019) 40:233–9. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2018.1499157

212. Bhaskar S, Rastogi A, Menon KV, Kunheri B, Balakrishnan S, Howick J. Call for action to address equity and justice divide during COVID-19. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:559905. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.559905

213. Bhaskar S, Bradley S, Chattu VK, Adisesh A, Nurtazina A, Kyrykbayeva S, et al. Telemedicine as the new outpatient clinic gone digital: position paper from the pandemic health system REsilience PROGRAM (REPROGRAM) international consortium (part 2). Front Public Health. (2020) 8:410. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00410

214. Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:510–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017

215. Usher K, Durkin J, Bhullar N. The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 29:315–8. doi: 10.1111/inm.12726

216. Hilty DM, Maheu MM, Drude KP, Hertlein KM. The need to implement and evaluate telehealth competency frameworks to ensure quality care across behavioral health professions. Acad Psychiatry. (2018) 42:818–24. doi: 10.1007/s40596-018-0992-5