- 1Clinic of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Katowice, Poland

- 2Department of Research and Development, Polfa Tarchomin, Warszawa, Poland

- 3Multispecialistic Voivodship Medical Clinic in Katowice, Katowice, Poland

- 4Abramowski 18th High School, Katowice, Poland

Background: The high incidence of phobias and the limited accessibility of psychotherapy are the reasons for the search for alternative treatments that increase the availability of effective treatment. The use of virtual reality (VR) technology is an option with the potential to overcome the barriers in obtaining an effective treatment. VR exposure therapy (VRET) is based on a very similar rationale for in vivo exposure therapy. The study aimed to answer the question of how to perform exposure therapy in a virtual reality environment so that it is effective.

Methods: A systematic review of the literature, using PRISMA guidelines, was performed. After analysis of 362 records, 11 research papers on agoraphobia, 28 papers on social phobia and 10 about specific phobias were selected for this review.

Results: VRET in agoraphobia and social phobia is effective when performed from 8 to 12 sessions, on average once a week for at least 15 min. In turn, the treatment of specific phobias is effective even in the form of one longer session, lasting 45–180 min. Head mounted displays are an effective technology for VRET. Increasing the frequency of sessions and adding drug therapy may shorten the overall treatment duration. The effectiveness of VRET in phobias is greater without concomitant psychiatric comorbidity and on the condition of inducing and maintaining in the patient an experience of immersion in the VR environment. Long-term studies show a sustained effect of VRET in the treatment of phobias.

Conclusion: A large number of studies on in VR exposure therapy in phobias allows for the formulation of some recommendations on how to perform VRET, enabling the effective treatment. The review also indicates the directions of further VRET research in the treatment of phobias.

Introduction

Phobic anxiety disorders are characterized by the occurrence of fear and anxiety in certain situations with little or no real threat, and a behavioral strategy to avoid those situations. Agoraphobia is an irrational fear of being out in the open space, in crowds, far from home, and of traveling alone. It is often accompanied or preceded by panic attacks. Social phobia, in turn, is an irrational fear of social situations and of avoiding them and specific phobias are fear and avoidance of specific objects or situations. All these phobias are common in the population. In the group of adults, the prevalence of specific phobias is estimated at 5–12% (1, 2), social phobia at 2.4% (3), and agoraphobia at 2.3% (4). All phobias may lead to a significant disability and impairment in everyday functioning, with the loss of social and professional roles (5).

Evidence from prospective studies suggests that anxiety disorders should be viewed as a chronic disorder that begins in childhood, adolescence or early adulthood, with a peak in middle age and a decline in old age (5). According to the 2015 Global Burden of Disease Study, anxiety disorders ranks ninth in the list of the largest contributors to global disability (6). In the case of social phobia, 37.6% of people diagnosed after 12 months found severe role impairment in at least one life domain, and an average number of 24.7 days out of role per 1 year was recorded (3). In the case of panic disorder with agoraphobia, 84.7% of people diagnosed after 12 months described severe impairment of the social role, and in the case of agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder, but with panic attacks, 39.0% reported severe impairment (7). These data show the urgent need to increase the availability of effective treatments.

The standard psychotherapy for agoraphobia and social phobia is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with the participation of a psychotherapist. Despite the convincing theoretical and empirical foundations, there appear to be barriers to the accessibility of this type of therapy in routine medical care. Neudeck and Einsle (8) mentioned structural barriers (e.g., time, insurance, or logistics) and barriers on the side of the therapist (e.g., negative attitude toward exposure therapy or insufficient knowledge of the method). These limitations hinder the accurate application of exposure techniques in clinical practice. These barriers pose a problem for patients, preventing them from receiving highly effective treatment (8). The use of virtual reality (VR) technology is an option with the potential to overcome these described difficulties. VR exposure therapy (VRET) is based on a very similar rationale for in vivo exposure therapy, however, in VR exposure, phobic stimuli are presented to the patient in a computer created artificial reality.

VR is a computer-generated reality that provides input to the user's sensory system and interacts with the user (9). Visual VR stimuli are presented through VR glasses [smartphone with 3D frames or a head-mounted display (HMD)] or by projection-based systems such as CAVE systems (automatic virtual environment in a cave), i.e., a room with up to six projection sides or Motek Caren system (10). The audio signal is input through speakers or head-phones, and optional tactile, or olfactory stimulation is possible but seldom provided. The goal of VR is to replace sensory stimuli from the real world and create an impression that a user is immersed in the real world experiencing. To interact with a user in real time, the VR system collects information about the user's position and head movements through sensors and input devices such as a head tracking system or a joystick.

To date, many clinical trials have been conducted, including randomized and controlled trials on the effectiveness of VRET in agoraphobia and social phobia. Due to a large amount of research, meta-analyzes assessing the above issue are also available in the literature. A summary of the most recent meta-analyzes on the use of VRET in the treatment of phobias is presented below.

In the meta-analysis by Wechsler et al. conducted in 2019 and involving 9 randomized and controlled clinical trials, the effectiveness of using VR in the treatment of agoraphobia and social phobia was assessed. It was shown that the use of VR in the treatment of social phobia compared to in vivo therapy did not bring any greater benefits (negative Hedges coefficient: −0.50). In the case of agoraphobia, no statistically significant advantage of in vivo therapy over VR was found (negative Hedges coefficient: −0.01). The authors indicated the need to conduct further randomized controlled clinical trials with the use of VR in order to expand the knowledge in this field (11).

Similar results were obtained by Carl et al. in a meta-analysis of 30 studies on the use of VR in the treatment of various phobias, including social anxiety and agoraphobia (12). These researchers showed a large effect size for VR compared to those who were not subjected to the intervention (positive Hedges coefficient: 0.90). In addition, an average to large effect size for VR was found compared to the psychological placebo conditions (positive Hedges coefficient: 0.78). The comparison of VR with conventional in vivo therapy did not show significant differences in the size of the effects (negative Hedges coefficient: −0.07). These results were relatively consistent across all analyzed disorders and they indicate that VR is effective and equal to conventional in vivo therapy as a medium for treating phobias (12).

In the most recent meta-analysis of 22 clinical trials with 703 participants by Horigome et al. the effectiveness of the use of VR in the treatment of social phobia was analyzed (13). The effectiveness of VR in treating social phobia was shown to be significant and sustained over a long observation period. Compared to in vivo exposure, the effectiveness of VR was similar after the intervention, but decreased in subsequent observation. The dropout rates of the participants showed no significant difference from the in vivo exposure results. Thus, the authors stated that VR is an acceptable method of treating patients with social phobia and has a significant long-term effect, although it is possible that its effectiveness will be reduced during long-term follow-up compared to conventional therapy.

Regarding the effectiveness of VRET in the treatment of specific phobias, a meta-analysis by Parsons and Rizzo (14) included 21 clinical trials involving 300 patients. VRET has been shown to be effective in reducing the symptoms of anxiety and phobias, especially in well-selected patients. The authors concluded that the use of VRET is effective in the treatment of anxiety and several specific types of phobias like social phobia, arachnophobia, acrophobia, agoraphobia, and aviophobia (14).

The impact of VRET on the behavior of patients with specific types of phobias in the real environment was also the subject of a meta-analysis of 14 studies conducted by Morina et al. (15). Behavioral evaluation results after treatment and during follow-up showed no significant differences between VRET and in vivo exposure (g = −0.09 and 0.53, respectively). The authors concluded that VRET cause significant changes in behavior in real-world situations (15). Also, in the last systematic review by Botella et al. (16), which included 11 randomized clinical trials, the effectiveness of using VRET in the treatment or support of the treatment of various types of phobias was assessed and found that applications using VRET have become an effective alternative that in terms of effectiveness can equal the results of traditional treatments for phobias (16).

The presented meta-analyzes confirm the effectiveness of VRET and its equivalence with in vivo exposure therapy. The authors decided to conduct their own review of studies to answer the question of how to perform exposure therapy in a virtual reality environment so that it is effective. The results of this literature review may provide clues for the planning of therapy protocols using VRET and for the construction of the VR environment for therapeutic means. They may also be considered to implement in subsequent projects of phobia exposure treatment using VRET.

Materials and Methods

The review included clinical trials, as well as case series and case reports. The authors' assumption was that even in single case reports of patients treated with VRET, there may be data on VRET elements that affect the effectiveness of exposure therapy. PRISMA guidelines were used when preparing this systematic review (17). The criteria for including the study in the analysis were the presence of a diagnosis of agoraphobia, social phobia and specific phobias and VRET treatment. The analysis also included studies in which, apart from VRET, a different treatment method was used. Full-text publications available in English were included in the analysis. In each study, at least the baseline and endpoints of treatment efficacy had to be characterized.

The following medical databases were searched in the study: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar (effective date 10/06/2021). The search was performed according to the PICO framework (P—patient, problem or population, I—intervention, C—comparison, control or comparator, O—outcomes). During our search, we used the following terms: “virtual reality” (Title/Abstract), “virtual exposure” (Title/Abstract), “agoraphobia” (Title/Abstract), “social phobia” (Title/Abstract), “social anxiety” (Title/Abstract); and “specific phobia” (Title/Abstract).

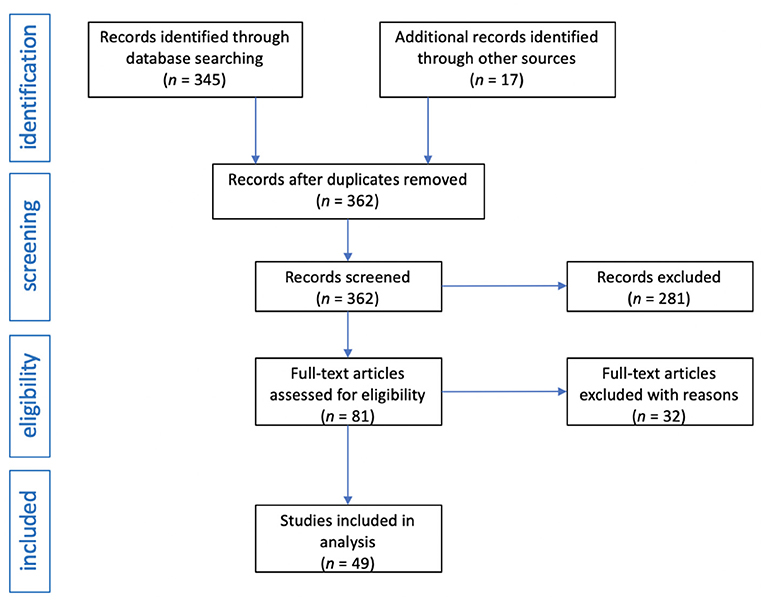

The review was conducted independently by two investigators. After obtaining 345 records from the medical databases searched, the same terms were entered in the Google search engine and an additional 17 publications were obtained. When duplicate records were removed, 173 records were obtained for further analysis. In the next stage, an initial selection was carried out, excluding meta-analyzes, reviews, mini-reviews, systematic reviews, letters to the editor, editorials, comments, and errata. This pre-selection resulted in 81 publications. An in-depth selection was then performed and publications with only abstracts, papers in a language other than English, studies not directly related to the topic, and studies with methodological errors or data gaps were excluded. Ultimately, 49 clinical trials were included in the systematic review. The flow diagram of the analysis is presented in Figure 1.

To assess the risk of bias and study quality in quantitative studies, the Effective Public Health Practice Project's (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QATQS) was used (18, 19). This tool enables quality evaluation of a wide range of study designs, including RCTs, observational studies with and without control groups and case studies. The instrument contains eight different sections, each with multiple questions: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and drop-outs, intervention integrity, and analyses. Each section receives a score of 1 (strong), 2 (moderate), or 3 (weak), and a final score is determined by the number of “weak” ratings. Strong rating is given to a study if there is no weak component score. Moderate rating is given with one weak component score. Weak rating is given with two or more component rating scores.

Results

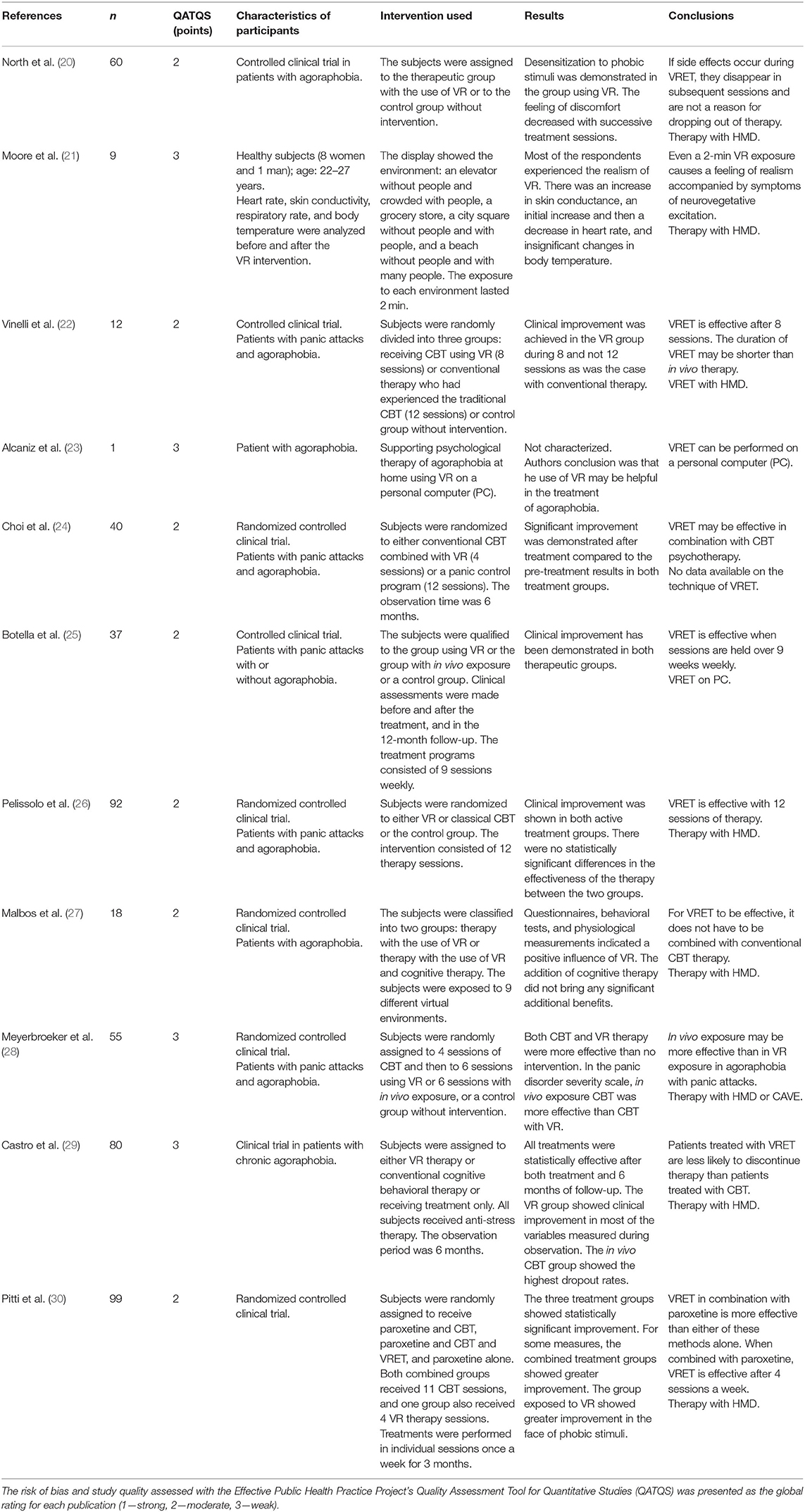

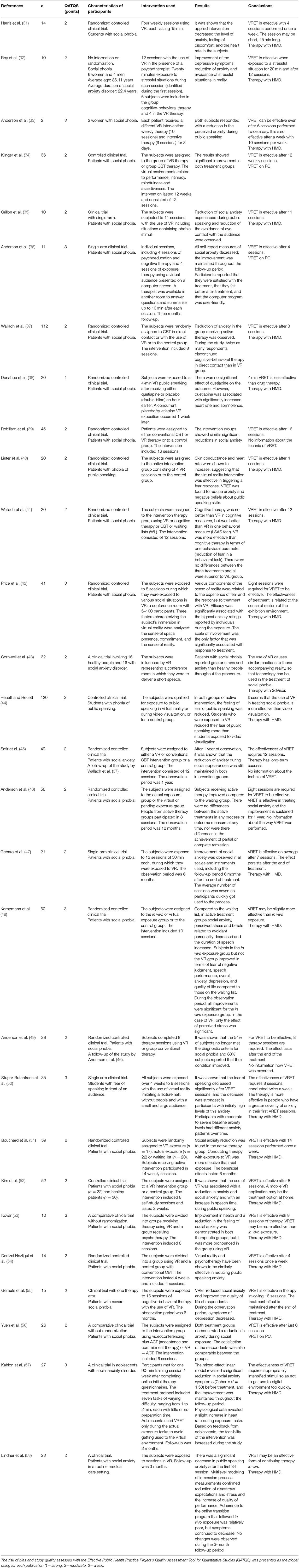

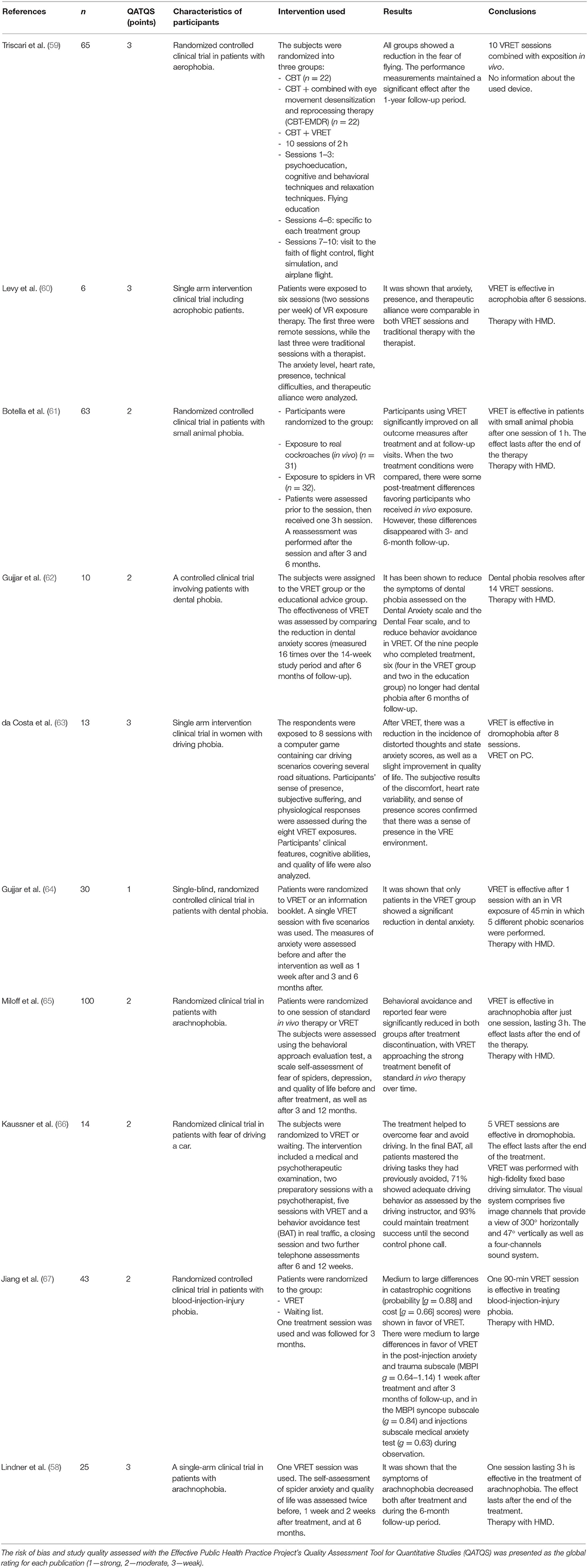

The tables below show the results of the systematic review of the literature on the use of VRET in the treatment of patients with agoraphobia (Table 1), social phobia (Table 2), and specific phobias (Table 3).

Discussion

Taking for granted the previously demonstrated effectiveness of VRET in the treatment of phobias, the current review focuses on parameters regarding the duration of therapy, session duration, session frequency, combining VRET with other types of therapy as well as technology used in exposure therapy. It was assumed that the conditions of using VRET in studies in which in VR exposure proved to be an effective form of phobia treatment determined its effectiveness. They should be considered as guidelines for the development of protocols and applications for running VRET.

With regard to the number of sessions and the duration of therapy, as shown by the analysis of the literature in agoraphobia, the number of sessions should be from 8 to 12. On the other hand, in social phobia, the number of sessions ensuring the effectiveness of VRET is more diverse. Its efficacy was demonstrated in therapies performed with one-time session (57), and the highest number of sessions performed with great success was 16 (39). Most often, however, the number of sessions giving the effectiveness of VRET in the treatment of social phobia was, similarly to the treatment of agoraphobia, from 8 to 12 sessions. In the treatment of specific phobias, short therapies, most often consisting of one VRET session, were preferred, although longer protocols, including up to 14 sessions, were also successfully used.

The duration of one VRET session varies greatly depending on the study. If a single session therapy is to be effective, the exposure must last at least 60 min (57). It seems that for VRET sessions to be effective, they must last at least 15–20 min (31, 32), especially if at least 4 are performed during the therapy (31). As mentioned, VRET in specific phobias is most often conducted in the form of a one-time session, however, these sessions must be longer. Based on the analysis, the VRET session in specific phobia should not be shorter than 45 min (64), but most often they last longer, even up to 3 h (58, 61, 65, 67).

The conducted literature analysis shows that in agoraphobia the effectiveness of therapy is ensured by performing an average of one in VR exposure per week. It is similar in VRET in social phobia, and it is most often performed once a week. Perhaps performing VRET more than once a week may shorten the overall duration of therapy. In one study, it lasted 3 days with two VRET sessions a day (33). The possibility of reducing the duration of VRET therapy by increasing the frequency of sessions, for example twice a day, is a promising direction for further research.

Regarding the technology used in VRET, the most common are head mounted displays. They were used in 71.4% of the analyzed studies. Literature review demonstrates greater effectiveness of HMD technology over 2D image viewing (44). Contemporary technology offers portable HMDs that enable convenient home therapy (52). Such a set can also be a smartphone with an application for VRET installed on it. It will certainly allow for increased availability in the future, and thus may popularize VRET in the treatment of phobias.

Regarding the combination of different treatment methods, although VRET is an effective method used in monotherapy (11–16), however, it may be much more effective when combined with pharmacotherapy (30). When VRET is used with pharmacotherapy, the number of sessions can be shortened [e.g., 4 sessions in agoraphobia; (30)]. There are still too few studies on the augmentation of pharmacological treatment with VRET to draw conclusions about the number of sessions, their frequency and duration of a single session. This is a topic that requires further research. In addition to pharmacotherapy, VRET can be combined with in vivo exposure therapy, either as a pre-phase to in vivo therapy or as a follow-up to it. Also, in this case, it is necessary to conduct research on the possibilities and indications for combining these two types of exposure treatment.

An important issue is compliance with the eligibility rules for the exposure treatment of phobias in VR. Improper qualification for treatment without excluding comorbidity reduces the effectiveness of VRET (14). The analyzed studies and previously conducted meta-analyzes indicate that VRET is an effective exposure therapy in the treatment of phobias, but, if in addition to phobia, a patient suffers from another mental disorder, the effectiveness of exposure therapy is lower (28). This indicates the importance of proper qualification for VRET and avoidance of psychiatric comorbidity in order to ensure its effectiveness.

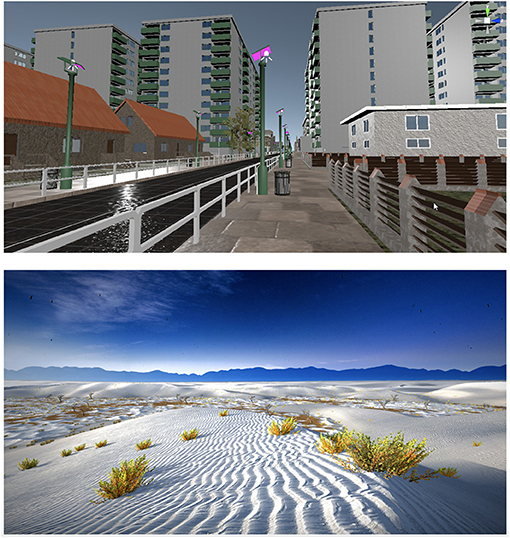

For the effectiveness of VRET, it is important for the patient to feel real and immersed in the environment provided by in VR exposure therapy (42, 43). With regard to the sense of immersion in virtual reality, it has been shown to occur very quickly. After just 2 min of using VRET, patients feel the realism of the virtual world (21). An important condition for the effectiveness of VRET is also the way of its conduct so that the patient does not get used to the digital VR environment too quickly without habituation to phobic stimuli. A way to counteract this familiarization with the digital environment may be the creation of many scenarios for the development of the exhibition environment (64). Also, the greater intensity of phobic stimuli may make it difficult to get used to the digital environment and to lose the sense of immersion in real experience (57). This is indirectly indicated by the greater effectiveness of in VR exposure in people with greater severity of phobias (50). In the technology of conducting therapy by automated voice-BOT therapeutic applications with a speech recognition system, it is possible to create an algorithm that increases the level of exposure to phobic stimuli depending on the speed of habituation to the VR exposure environment (Figure 2). The evidence that it is possible to provide a full sense of reality in digital reality at least at the level of in vivo exposure are the reports that in VR exposure is more effective than in vivo (48, 53). The more virtual reality will imitate reality in terms of graphic resolution, a variety of scenarios and their dynamic adaptation to the patient's behavior, the greater will be its effectiveness.

Figure 2. The virtual exposure environment must provide the patient with a sufficient level of realism for the VRET to be effective. The photos show examples of high-quality computer graphics of opened space exposure environment from the VR voice-BOT application, developed (photos made by MK). Before treatment, the patient determines the type of phobic environment, as well as customizes it depending on his preferences, specifying the time of day, weather and the type of exposure. Exposure in a three-dimensional graphics environment is enriched with three-dimensional sound, recorded in real conditions. Next, VR voice-BOT, thanks to the speech recognition system, conducts an exposure hierarchy with the patient, increasing the intensity of phobic stimuli in the environment previously defined by the patient and asking him to determine the subjective level of distress in the subjective units of distress scale (SUDS). During the exposure, the patient uses his own smartphone with the application installed on it, and a joystick, and moves freely in a virtual environment.

As indicated by the conducted analysis, VRET exposure may give a lasting effect. However, long-term efficacy has not been studied for more than a year it seems satisfactory. Safir et al. (45) showed that after 1 year of clinical improvement, the reduction of social phobia symptoms is still maintained, regardless of whether the therapy was performed with VRET or in vivo exposure (42). Similar in other studies that conducted long-term follow-up of patients after treatment, it was possible to demonstrate the durability of the treatment effect after the completion of VRET (46, 47, 49, 51). This may indicate no need for maintenance therapy with VR. To confirm that, in subsequent studies of the effectiveness of phobia therapy with VRET, long-term follow-up of patients after the completion of VR therapy should be considered.

Conclusions

A large number of studies on in VR exposure therapy in phobias allows for the formulation of some recommendations on how to perform VRET, enabling the effective treatment. The conducted analysis of clinical trials allows to conclude that VRET in agoraphobia and social phobia is effective when performed from 8 to 12 sessions, on average once a week for at least 15 min. In turn, the treatment of specific phobias is effective even in the form of one longer session, lasting 45–180 min. Head mounted displays are an effective technology for VRET. Increasing the frequency of sessions and adding drug therapy may shorten the overall treatment duration. Moreover, the effectiveness of VRET in phobias is greater without psychiatric comorbidity and on the condition of generating and maintaining in the patient a sense of immersion in the VR environment.

Further studies should focus on the possibility of augmentation of pharmacological treatment with VRET, indications for combining in VR exposure with in vivo exposure, as well as the durability of VRET effects with possible maintenance therapy. In the future, it is also necessary to check the effectiveness of treatment protocols in which VRET is used more than once a week in terms of the possibility of reducing the total duration of treatment of phobias.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

MK: conceptualization, data curation, and visualization. MK, SS, and MR: methodology. SS and MR: software. MK, MS, and MB: validation. SS, MR, MB, JP, MK, and NK: literature selection and analysis. MK, SS, MR, and JP: writing and original draft preparation. MK, MB, SS, MR, and NK: writing, review, and editing. MB and MS: supervision and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received funding from Polfa Tarchomin S.A. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Voice VR BOT for VRET in agoraphobia described in the text was a project implemented from a Ministry of Science and Higher Education Grant (Dialog, No. 0075/DLG/2019/10).

References

1. Ausin B, Muñoz M, Castellanos M, García S. Prevalence and characterization of specific phobia disorder in people over 65 years old in a madrid community sample (Spain) and its relationship to quality of life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1915. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17061915

2. Wardenaar KJ, Lim CCW, Al-Hamzawi AO, Alonso J, Andrade LH, Benjet C, et al. The cross-national epidemiology of specific phobia in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med. (2017) 47:1744–60. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000174

3. Stein DJ, Lim CCW, Roest AM, de Jonge P, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. The cross-national epidemiology of social anxiety disorder: data from the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. BMC Med. (2017) 15:143. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0889-2

4. Goodwin R, Faravelli C, Rosi S, Cosci F, Truglia E, de Graaf R, et al. The epidemiology of panic disorder and agoraphobia in Europe. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2005) 15:435–43. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.006

5. Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2015) 17:327–35. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/bbandelow

6. GDB 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence an Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Lancet. (2016) 388:1545–602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6

7. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Jin R, Ruscio AM, Shear K, Walters EE. The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2006) 63:415–24. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.415

8. Neudeck P, Einsle F. Dissemination of exposure therapy in clinical practice: How to handle the barriers? In: Neudeck P, Wittchen H, editors. Exposure Therapy: Rethinking the Model - Refining the Method. New York, NY: Springer (2012). p. 23–34. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3342-2_3

9. Diemer J, Pauli P, Mühlberger A. Virtual reality in psychotherapy. In: Wright JD, editor. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier (2015). p. 138–46. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.21070-2

10. Krysta K, Wilczyński K, Paliga J, Szczesna A, Wojciechowska M, Martyniak E, et al. Implementation of the MOTEK CAREN system in behavioural therapy for patients with anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Danub. (2016) 28:116–20.

11. Wechsler T, Kümpers F, Mühlberger A. Inferiority or even superiority of virtual reality exposure therapy in phobias? A systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis on randomized controlled trials specifically comparing the efficacy of virtual reality exposure to gold standard in vivo exposure in agoraphobia, specific phobia, and social phobia. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:1758. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01758

12. Carl E, Stein A, Levihn-Coon A, Pogue JR, Rothbaum B, Emmelkamp P, et al. Virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Anxiety Disord. (2019) 61:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.08.003

13. Horigome T, Kurokawa S, Sawada K, Kudo S, Shiga K, Mimura M, et al. Virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. (2020) 50:2487–97. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720003785

14. Parsons TD, Rizzo AA. Affective outcomes of virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety and specific phobias: a meta-analysis. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. (2008) 39:250–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.07.007

15. Morina N, Ijntema H, Meyerbröker K, Emmelkamp PM. Can virtual reality exposure therapy gains be generalized to real-life? A meta-analysis of studies applying behavioral assessments. Behav Res Ther. (2015) 74:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.010

16. Botella C, Fernández-Álvarez J, Guillén V, García-Palacios A, Baños R. Recent progress in virtual reality exposure therapy for phobias: a systematic review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2017) 19:42. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0788-4

17. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 151:264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

18. Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. (2004) 1:176–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x

19. Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. (2012) 18:12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x

20. North MM, North SM, Coble JR. Effectiveness of virtual environment desensitization in the treatment of agoraphobia. Int J Virtual Reality. (1995) 1:25–34.

21. Moore K, Wiederhold BK, Wiederhold MD, Riva G. Panic and agoraphobia in a virtual world. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2002) 5:197–202. doi: 10.1089/109493102760147178

22. Vinelli F, Anolli L, Bouchard S, Wiederhold B, Zurloni V, Riva G. Experiential cognitive therapy in the treatment of panic disorders with agoraphobia: a controlled study. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2003) 6:321–8. doi: 10.1089/109493103322011632

23. Alcaniz M, Botella C, Banos R, Perpina C, Rey B, Lozano JA, et al. Internet-based telehealth system for the treatment of agoraphobia. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2003) 6:355–8. doi: 10.1089/109493103322278727

24. Choi Y, Vincelli F, Riva G, Wiederhold B, Lee J, Park K. Effects of group experiential cognitive therapy for the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2005) 8:387–93. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.387

25. Botella C, García-Palacios A, Villa H, Banos RM, Quero S, Alcañiz M, et al. Virtual reality exposure in the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia: a controlled study. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2007) 14:164–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2006.01.008

26. Pelissolo A, Zaoui M, Aguayo G, Yao SN, Roche S, Ecochard R, et al. Virtual reality exposure therapy versus cognitive behavior therapy for panic disorder with agoraphobia: a randomized comparison study. J Cyb Ther Rehab. (2012) 5:35–43.

27. Malbos E, Rapee RM, Kavakli MA. controlled study of agoraphobia and the independent effect of virtual reality exposure therapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. (2013) 47:160–8. doi: 10.1177/0004867412453626

28. Meyerbroeker K, Morina N, Kerkhof GA, Emmelkamp PMG. Virtual reality exposure therapy does not provide any additional value in agoraphobic patients: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. (2013) 82:170–6. doi: 10.1159/000342715

29. Castro WP, Roca Sánchez MJ, Pitti González CT, Bethencourt JM, de la Fuente Portero JA, Marco RG. Cognitive-behavioral treatment and antidepressants combined with virtual reality exposure for patients with chronic agoraphobia. Int J Clin Health Psychol. (2014) 14:9–17. doi: 10.1016/S1697-2600(14)70032-8

30. Pitti CT, Peñate W, De La Fuente J, Bethencourt JM, Roca-Sánchez MJ, Acosta L, et al. The combined use of virtual reality exposure in the treatment of agoraphobia. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. (2015) 4343:133–41.

31. Harris SR, Kemmerling RL, North MM. Brief virtual reality therapy for public speaking anxiety. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2002) 5:543–50. doi: 10.1089/109493102321018187

32. Roy S, Klinger E, Legeron P, Lauer F, Chemin I, Nugues P. Definition of a VR-based protocol to treat social phobia. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2003) 6:411–20. doi: 10.1089/109493103322278808

33. Anderson P, Rothbaum B, Hodges LF. Virtual reality exposure in the treatment of social anxiety. Cogn Behav Pract. (2003) 10:240–7. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80036-6

34. Klinger E, Bouchard S, Légeron P, Roy S, Lauer F, Chemin I, et al. Virtual reality therapy versus cognitive behavior therapy for social phobia: a preliminary controlled study. Cyber Psychol Behav. (2005) 8:76–88. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.76

35. Grillon H, Riquier F, Herbelin B, Thalmann D. Virtual reality as therapeutic tool in the confines of social anxiety disorder treatment. Int J Disabil Human Dev. (2006) 5:243–50. doi: 10.1515/IJDHD.2006.5.3.243

36. Anderson P, Zimand E, Schmertz S, Ferrer M. Usability and utility of a computerized cognitive-behavioral self-help program for public speaking anxiety. Cogn Behav Pract. (2007) 14:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2006.02.006

37. Wallach HS, Safir MP, Bar-Zvi M. Virtual reality cognitive behavior therapy for public speaking anxiety: a randomized clinical trial. Behav Modif. (2009) 33:314–38. doi: 10.1177/0145445509331926

38. Donahue CB, Kushner MG, Thuras PD, Murphy TG, Van Demark JB, Adson DE. Effect of quetiapine vs. placebo on response to two virtual public speaking exposures in individuals with social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. (2009) 23:362–8. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.12.004

39. Robillard G, Bouchard S, Dumoulin S, Guitard T, Klinger E. Using virtual humans to alleviate social anxiety: preliminary report from a comparative outcome study. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2010) 154:57–60.

40. Lister HA, Piercey CD, Joordens C. The effectiveness of 3-D video virtual reality for the treatment of fear of public speaking. J Cyber Ther Rehabil. (2010) 3:375–81.

41. Wallach H, Safir P, Bar-Zvi M. Virtual reality exposure versus cognitive restructuring for treatment of public speaking anxiety: a pilot study. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. (2011) 48:91–7.

42. Price M, Mehta N, Tone EB, Anderson PL. Does engagement with exposure yield better outcomes? Components of presence as a predictor of treatment response for virtual reality exposure therapy for social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. (2011) 25:763–70. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.004

43. Cornwell BR, Heller R, Biggs A, Pine DS, Grillon C. Becoming the center of attention in social anxiety disorder: startle reactivity to a virtual audience during speech anticipation. J Clin Psychiatry. (2011) 72:942–8. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05731blu

44. Heuett B, Heuett K. Virtual reality therapy: a means of reducing public speaking anxiety. Int J Humanit Soc Sci. (2011) 1:1–6.

45. Safir M, Wallach H, Bar-Zvi M. Virtual reality cognitive-behavior therapy for public speaking anxiety: one-year follow-up. Behav Modif. (2012) 36:235–46. doi: 10.1177/0145445511429999

46. Anderson PL, Price M, Edwards SM, Obasaju MA, Schmertz SK, Zimand E, et al. Virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Consul Clin Psychol. (2013) 81:751. doi: 10.1037/a0033559

47. Gebara CM, Barros-Neto TPD, Gertsenchtein L, Lotufo-Neto F. Virtual reality exposure using three-dimensional images for the treatment of social phobia. Braz J Psychiatry. (2016) 38:24–9. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1560

48. Kampmann IL, Emmelkamp PMG, Hartanto D, Brinkman WP, Zijlstra BJH, Morina N. Exposure to virtual social interactions in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. (2016) 77:147–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.016

49. Anderson PL, Edwards SM, Goodnight JR. Virtual reality and exposure group therapy for social anxiety disorder: results from a 4–6 year follow-up. Cog Ther Res. (2017) 41:230–6. doi: 10.1007/s10608-016-9820-y

50. Stupar-Rutenfrans S, Ketelaars L, van Gisbergen M. Beat the fear of public speaking: mobile 360° video virtual reality exposure training in home environment reduces public speaking anxiety. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2017) 20:624–33. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0174

51. Bouchard S, Dumoulin S, Robillard G, Guitard T, Klinger É, Forget H, et al. Virtual reality compared with in vivo exposure in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: a three-arm randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. (2017) 210:276–83. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.184234

52. Kim HE, Hong YJ, Kim MK, Jung YH, Kyeong S, Kim JJ. Effectiveness of self-training using the mobile-based virtual reality program in patients with social anxiety disorder. Comput Human Behav. (2017) 73:614–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.017

53. Kovar I. Virtual reality as support of cognitive behavioral therapy in social anxiety disorder. IJASEIT. (2018) 8:1343–9. doi: 10.18517/ijaseit.8.4.5904

54. Denizci Nazligul M, Yilmaz M, Gulec U, Yilmaz AE, Isler V, O'Connor RV, et al. An interactive 3d virtual environment to reduce the public speaking anxiety levels of novice software engineers. IET Softw. (2019) 13:152–8. doi: 10.1049/iet-sen.2018.5140

55. Geraets CN, Veling W, Witlox M, Staring AB, Matthijssen SJ, Cath D. Virtual reality-based cognitive behavioural therapy for patients with generalized social anxiety disorder: a pilot study. Behav Cogn Psychother. (2019) 47:745–50. doi: 10.1017/S1352465819000225

56. Yuen E, Goetter E, Stasio M, Ash P, Mansour B, McNally E, et al. A pilot of acceptance and commitment therapy for public speaking anxiety delivered with group videoconferencing and virtual reality exposure. J Contextual Behav Sci. (2019) 12:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.01.006

57. Kahlon S, Lindner P, Nordgreen T. Virtual reality exposure therapy for adolescents with fear of public speaking: a non-randomized feasibility and pilot study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2019) 13:47. doi: 10.1186/s13034-019-0307-y

58. Lindner P, Miloff A, Bergman C, Andersson G, Hamilton W, Carlbring P. Gamified, automated virtual reality exposure therapy for fear of spiders: a single-subject trial under simulated real-world conditions. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:116. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00116

59. Triscari MT, Faraci P, Catalisano D, D'Angelo V, Urso V. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy integrated with systematic desensitization, cognitive behavioral therapy combined with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy combined with virtual reality exposure therapy methods in the treatment of flight anxiety: a randomized trial. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2015) 11:2591–8. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S93401

60. Levy F, Leboucher P, Rautureau G, Jouvent R. E-virtual reality exposure therapy in acrophobia: a pilot study. J Telemed Telecare. (2016) 22:215–20. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15598243

61. Botella C, Pérez-Ara MÁ, Bretón-López J, Quero S, García-Palacios A, Baños RM. In vivo versus augmented reality exposure in the treatment of small animal phobia: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0148237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148237

62. Gujjar KR, van Wijk A, Sharma R, de Jongh A. Virtual reality exposure therapy for the treatment of dental phobia: a controlled feasibility study. Behav Cogn Psychother. (2018) 46:367–73. doi: 10.1017/S1352465817000534

63. Costa RTD, Carvalho MR, Ribeiro P, Nardi AE. Virtual reality exposure therapy for fear of driving: analysis of clinical characteristics, physiological response, and sense of presence. Braz J Psychiatry. (2018) 40:192–9. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2270

64. Gujjar KR, van Wijk A, Kumar R, de Jongh A. Efficacy of virtual reality exposure therapy for the treatment of dental phobia in adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord. (2019) 62:100–8. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.12.001

65. Miloff A, Lindner P, Dafgård P, Deak S, Garke M, Hamilton W, et al. Automated virtual reality exposure therapy for spider phobia vs. in-vivo one-session treatment: a randomized non-inferiority trial. Behav Res Ther. (2019) 118:130–40. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2019.04.004

66. Kaussner Y, Kuraszkiewicz AM, Schoch S, Markel P, Hoffmann S, Baur-Streubel R, et al. Treating patients with driving phobia by virtual reality exposure therapy - a pilot study. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0226937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226937

Keywords: agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobias, exposure therapy, virtual exposure therapy, VRET, virtual reality, VR

Citation: Krzystanek M, Surma S, Stokrocka M, Romańczyk M, Przybyło J, Krzystanek N and Borkowski M (2021) Tips for Effective Implementation of Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy in Phobias—A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 12:737351. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.737351

Received: 06 July 2021; Accepted: 16 August 2021;

Published: 21 September 2021.

Edited by:

Hanna Karakula-Juchnowicz, Medical University of Lublin, PolandReviewed by:

Marcin Siwek, Jagiellonian University, Medical College, PolandRenana Eitan, Hebrew University Hadassah Medical School, Israel

Copyright © 2021 Krzystanek, Surma, Stokrocka, Romańczyk, Przybyło, Krzystanek and Borkowski. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marek Krzystanek, bS5rcnp5c3RhbmVrQHN1bS5lZHUucGw=; a3J6eXN0YW5la21hcmVrQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

Marek Krzystanek

Marek Krzystanek Stanisław Surma1

Stanisław Surma1 Małgorzata Stokrocka

Małgorzata Stokrocka