95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Psychiatry , 19 August 2021

Sec. Molecular Psychiatry

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.724170

This article is part of the Research Topic Rising Stars in Molecular Psychiatry View all 6 articles

Introduction: Polypharmacy and genetic variants that strongly influence medication response (pharmacogenomics, PGx) are two well-described risk factors for adverse drug reactions. Complexities arise in interpreting PGx results in the presence of co-administered medications that can cause cytochrome P450 enzyme phenoconversion.

Aim: To quantify phenoconversion in a cohort of acute aged persons mental health patients and evaluate its impact on the reporting of medications with actionable PGx guideline recommendations (APRs).

Methods: Acute aged persons mental health patients (N = 137) with PGx and medication data at admission and discharge were selected to describe phenoconversion frequencies for CYP2D6, CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 enzymes. The expected impact of phenoconversion was then assessed on the reporting of medications with APRs.

Results: Post-phenoconversion, the predicted frequency at admission and discharge increased for CYP2D6 intermediate metabolisers (IMs) by 11.7 and 16.1%, respectively. Similarly, for CYP2C19 IMs, the predicted frequency at admission and discharge increased by 13.1 and 11.7%, respectively. Nineteen medications with APRs were prescribed 120 times at admission, of which 50 (42%) had APRs pre-phenoconversion, increasing to 60 prescriptions (50%) post-phenoconversion. At discharge, 18 medications with APRs were prescribed 122 times, of which 48 (39%) had APRs pre-phenoconversion, increasing to 57 prescriptions (47%) post-phenoconversion.

Discussion: Aged persons mental health patients are commonly prescribed medications with APRs, but interpretation of these recommendations must consider the effects of phenoconversion. Adopting a collaborative care model between prescribers and clinical pharmacists should be considered to address phenoconversion and ensure the potential benefits of PGx are maximised.

Prescribed medications offer many therapeutic benefits but can also cause serious adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Polypharmacy, often defined as five or more regular medicines, resulting in harmful drug-drug interactions (DDIs), and the presence of genetic variants that strongly influence medication response (pharmacogenomics, PGx), are two well-described risk factors for ADRs (1–4). Pharmacogenomic testing is a strategy to address these risk factors, optimise medication selection and doses, and reduce the burden of ADRs (5). Since many psychotropic medicines have well-established cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) and CYP2C19 variants that influence pharmacokinetics, PGx is increasingly being utilised in psychiatry to guide prescribing, particularly for antidepressants. Peer-reviewed PGx dosing guidelines for psychotropics and many other medications are available to help improve the clinical implementation1.

In the real-world setting, complexities arise when interpreting PGx results for patients taking medications that can alter the genotype-predicted phenotype of drug metabolising enzymes, a process known as phenoconversion (PC). For example, a genotype-predicted normal metaboliser (NM) for CYP2D6 is expected to have a typical analgesic response to codeine (6). However, if the patient is co-prescribed paroxetine, a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor, the patient's CYP2D6 genotype-predicted phenotype will likely be converted to a poor metaboliser (PM) (7), resulting in greatly reduced morphine formation and diminished analgesia (6). It is more logical in this scenario to follow the codeine guideline recommendation for a CYP2D6 PM rather than the genotype-predicted NM.

Whilst PGx testing offers a useful first step in individualising pharmacotherapy, an overlay of PC could be applied to improve the prediction of medication response for current and planned medication therapy. Due to the added complexity of PC in interpretating PGx results, adopting a novel PGx stewardship program, akin to antimicrobial stewardship, should be considered as a viable strategy to address the challenge (8). This would consist of specific expertise in PGx to ensure that the potential benefits of testing are maximised e.g., clinical pharmacists embedded in general practice (9).

The aim of this analysis was to determine the degree of possible medication-induced PC in a cohort of acute aged persons mental health patients who had PGx testing. These highly complex patients with multiple co-morbidities and polypharmacy were considered a suitable cohort to investigate the potential impact of PC on medications with actionable PGx guideline recommendations (APRs).

This is a retrospective analysis utilising a sub-set of acute care psychiatric inpatients who participated in a PGx study. In brief, 270 eligible patients and residents were enrolled over a 10-month period, 177 from two aged persons acute mental health units and 93 from long stay residential units. Of these, 170 acute care patients and 82 residential patients underwent PGx screening. The PGx profiles were determined from blood samples or buccal cheek swabs which were taken on average within 1 week of admission. All patients were asked to consent for sample/swab collection and PGx testing, however, if they were mentally incompetent, the ethics committee advised that a consent waiver should be used. A further sub-set of 137 patients with PGx data who had full medication lists at admission and discharge were selected for this analysis to describe PC. Pharmacy medication records were used to determine the medications taken by each patient. Ethical approval for the PGx study was provided by the Melbourne Health Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 2012.230).

DNA was extracted from EDTA whole blood samples and from buccal swabs using either QIAamp mini column kits or by the Qiasymphony SP automated platform. CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and VKORC1 polymorphic sites were detected by iPLEX extension reactions using the Agena MassArray. The number of CYP2D6 gene copies was detected by qPCR using a 7900HT PCR system. Any copy number variants were confirmed by long-range PCR. Alleles identified included: CYP2D6*2, *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, *8, *9, *10, *14A, *14B, *17, *20, *39, and *41; CYP2C19*2, *3, *17 and CYP2C9*2 and *3. This genotyping panel covered 95% of known variant alleles in Caucasian populations for CYP2D6, 99% for CYP2C19 and 96% for CYP2C9. Additionally, common variant alleles were also selected to cover African and Asian populations. It is important to note that the *1 allele is not directly genotyped and is assigned as the “wild type” allele for CYP2D6, CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 based on the absence of any interrogated variant in the genotyping panel for each gene. VKORC1 testing identified the common variant (−1639G > A) in the promoter region of the vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 gene (VKORC1). This variant has a strong association with warfarin dosage requirements (10).

The CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9 allele activity scores were calculated as previously described (11–14). For each participant, the genotype activity score, which is the sum of activity scores for all alleles in the genotype, was used to assign the phenotype (Supplementary Tables 2, 3). The maximum possible CYP2D6 PC-corrected activity score was calculated by multiplying the genotype activity score by 0 for a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor and by 0.5 for a moderate CYP2D6 inhibitor as previously described (15–17). For example, a CYP2D6 genotype of *1/*1 attracts an activity score of 2, which translates to a CYP2D6 NM phenotype. If the patient is taking a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor (e.g., paroxetine), then the PC-corrected activity score becomes 0 (the product of 2 × 0 = 0), which translates to a CYP2D6 PM phenotype. This CYP2D6 PC-corrected activity score system was adapted for CYP2C19 and CYP2C9. In the presence of an inducer, the CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 phenotypes were converted to the next higher activity phenotype (e.g., IM to NM) as previously described (18, 19). Medications were classified as moderate or strong CYP inhibitors or strong CYP inducers based on the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) table of CYP inhibitors and inducers, the “Flockhart Table,” and a criteria-based classification by Polasek and colleagues (20–22).

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) PGx guidelines were used to assess whether a patient's prescribed medication had an APR based on the genotype-predicted phenotype and the PC-corrected phenotype. A medication was considered to have an APR if the CPIC or DPWG guidelines recommended a change in dose or suggested an increased risk of adverse effects. For example, a patient taking citalopram was considered to have an APR if they had a CYP2C19 genotype-predicted phenotype or a PC-corrected phenotype of a PM, where CPIC recommends a 50% reduction in the starting dose (23). Medications that autoinhibit their own metabolism were assessed for APRs using the genotype-predicted phenotype only.

Chi-squared statistical testing was used to describe the differences in predicted phenotype frequencies between the study participants against expected frequencies in the Australian population based on data from our previous study of 5,408 Australians (18). A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to assess the difference in the number of prescribed medications with APRs between admission and discharge. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.2 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com; and IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

The average age of patients who had PGx testing was 78.5 years (range 60 to 97 years), with 61% female and 39% male. The ethnic breakdown of these patients was: 89% Caucasian, 4% Asian, 2% African and 1% Middle Eastern, while 3% did not have ethnicity recorded.

The predicted phenotype frequencies for CYP2D6, CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 are summarised in Table 1, whilst results for VKORC1 are given in Supplementary Table 1. The phenotype frequencies for CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9 in the study population were similar to the frequencies reported previously for these CYP enzymes in the Australian population (18) (P >> 0.05).

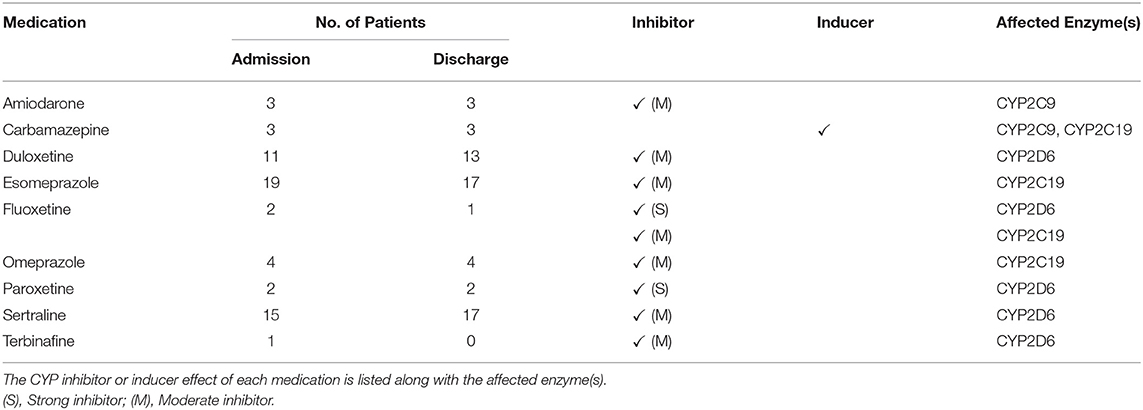

There were nine phenoconverting medications recorded at admission and eight at discharge (Table 2). Collectively, esomeprazole, sertraline and duloxetine represented 71% of the phenoconverting medications at admission and 76% of the phenoconverting medications at discharge.

Table 2. List of perpetrator medications responsible for CYP2D6, CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 phenoconversion identified at admission and discharge.

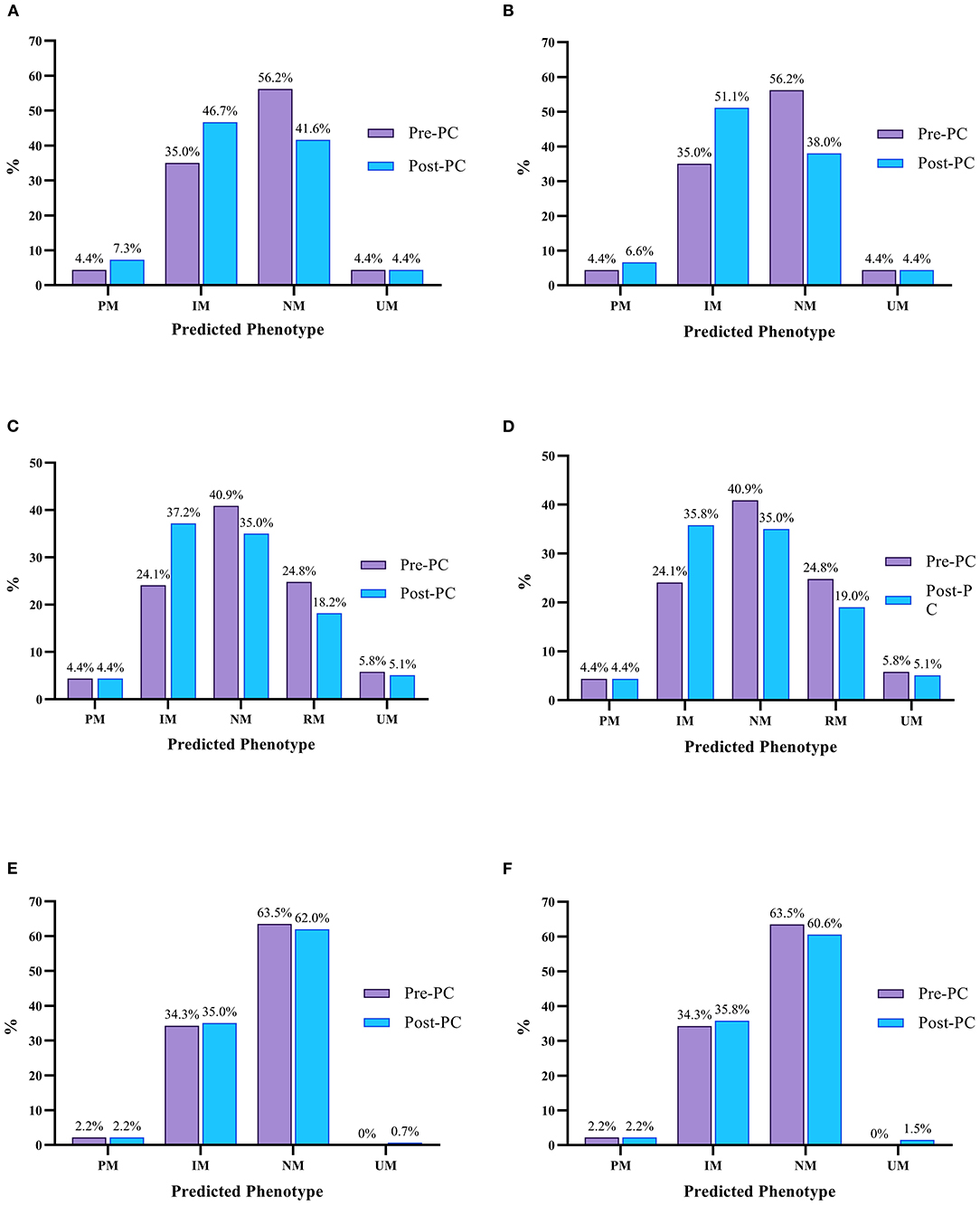

Figure 1 shows the predicted phenotype frequencies pre- and post-PC for CYP2D6, CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 at admission and at discharge. CYP2D6 IMs increased by 11.7% at admission and 16.1% at discharge, whilst CYP2C19 IMs increased by 13.1 and 11.7% at admission and discharge, respectively. Only modest changes were noted for other CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 phenotypes, with CYP2D6 PMs increasing by 2.9% at admission and 2.2% at discharge. Due to a small number of CYP2C9 inhibitors and inducers, the CYP2C9 phenoconversion corrected phenotype frequencies were very similar to the genotype predicted phenotype frequencies.

Figure 1. Predicted pre (purple) and post-PC (blue) phenotype frequencies for CYP2D6, CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 at admission and discharge. (A) Predicted CYP2D6 Phenotype Frequencies At Admission, (B) Predicted CYP2D6 Phenotype Frequencies At Discharge; (C) Predicted CYP2C19 Phenotype Frequencies At Admission, (D) Predicted CYP2C19 Phenotype Frequencies At Discharge; (E) Predicted CYP2C9 Phenotype Frequencies At Admission, (F) Predicted CYP2C9 Phenotype Frequencies At Discharge. UM, Ultrarapid Metaboliser; RM, Rapid Metaboliser; NM, Normal Metaboliser; IM, Intermediate Metaboliser; PM, Poor Metaboliser.

The median number of regular prescription medications recorded on admission was seven (range 1–15) compared to a median of 6 (range 1–13) at discharge. At admission, 103 (75%) patients were categorised as taking polypharmacy (prescribed five or more medications) vs. 89 (65%) patients at discharge. Patients were prescribed 144 different medications at admission, with 19 (13%) having APRs (Table 3). These 19 medications were prescribed a total of 120 times at admission, of which, 50 (42%) had APRs based on genotype predicted phenotype results, increasing to 61 (51%) when PC-corrected phenotypes were considered. At discharge, 143 medications were prescribed, with 18 (13%) having APRs. These 18 medications were prescribed a total of 122 times at discharge, of which, 48 (39%) had APRs based on genotype predicted phenotype results, increasing to 57 (47%) when PC-corrected phenotypes were used (Table 3). A Wilcoxon signed rank test revealed no statistically significant change in prescribed medications with APRs between admission and discharge, N = 137, Z = 0.258, P = 0.796.

Our findings from the analysis of a cohort of acute aged persons mental health patients demonstrated that, (i) the total number of prescribed medications with APRs increased by about 9% at admission and discharge post-PC, (ii) the CYP2D6 PMs and CYP2C19 IMs had the largest increases in PC-corrected phenotypes at admission and on discharge, and (iii) the CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9 phenotype frequencies were similar to the general Australian population. Our approach has recently been highlighted as a practical method to account for the effects of PC on PGx test results (24, 25).

Seventy five percent of patients were taking polypharmacy at admission (defined as five or more regular medications). This is consistent with recent Australian data showing that polypharmacy in Australians >65 years old is as high as 91% and rises with advancing age (26). The prevalence of polypharmacy is also high in older psychiatric patients due to the combination of medication regimens to treat age related co-morbidities plus their psychiatric conditions, thus placing them at greater risk of ADRs and DDIs (27, 28). Therefore, this patient group are likely to benefit significantly from PGx testing and interpretation to optimise their medications.

Using PGx results alone is known to underestimate the incidence of clinically relevant CYP phenotypes (PMs, IMs, UMs). Indeed, one study reported a 5-fold increase in CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 PM frequencies once PC was taken into account (18), while another found a 7-fold increase in CYP2D6 PMs, which was validated by pharmacokinetic sampling (15). While we did not find this degree of increase in PM frequencies, we did observe a notable increase in CYP2D6 PMs−1.7-fold increase at admission and 1.5-fold at discharge. The frequency of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 IMs was also notably increased—CYP2D6 IMs increased by 1.3-fold at admission and 1.5-fold at discharge, whilst CYP2C19 IMs increased by 1.5-fold at admission and discharge. These results were comparable to a recent study of clozapine treated schizophrenia patients in Australia, which reported a 1.8-fold increase in CYP2D6 PMs and IMs and 1.7-fold increase in CYP2C19 IMs post-PC (25). The lower rates of PC in our analysis compared to other studies may be due to subtle differences in study populations. Here, there were geriatric patients with a mixture of psychiatric disorders on admission with similar ethnic backgrounds, whilst previous studies with higher rates of PC included patients predominantly being treated for depressive disorders receiving fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and paroxetine, well-known strong PC medications (29). This highlights the likely extent and variability of PC and the need to review PC every time there is prescribing or deprescribing of clinically relevant CYP inhibitors and/or inducers.

Regardless, these findings are clinically important as there are many medications which have APRs based on an IM or PM phenotype for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19. In fact, the following medications listed at admission for our study cohort are examples of medicines with APRs for CYP2D6 and/or CYP2C19 PMs and IMs: codeine, clopidogrel, metoprolol, omeprazole, pantoprazole, clomipramine, paroxetine, venlafaxine and zuclopenthixol. Although there was only a modest (8%) increase in prescribed medications with APRs, it still provides useful information that can help optimise dosing and improve the care of this highly complex and vulnerable group of patients. In addition to medication-induced PC, other extrinsic factors have been reported to result in PC including age, frailty, obesity, cancer, inflammation, and vitamin D exposure, all of which are applicable to our cohort of older patients (24). However, presently there are no expert consensus guidelines nor a reliable strategy to quantify and test for the effect of these factors clinically. Thus, further investigation on their impact on PC is warranted.

Our analysis utilised real PGx data and pharmacist reconciled medication profiles, thus providing an accurate reflection of clinical practice. At present, the majority of PGx reports are provided to the treating doctor in a static report format without accounting for the potential effect of PC. This makes it challenging for the prescriber to address PC, especially when the patient's prescribed medications frequently change. For example, if PC is taken into account by the prescriber and the PC-corrected phenotype is used to select the appropriate APRs, then once the patient's “phenoconverting” medication(s) are ceased or changed, the inhibited or induced CYP enzyme will likely revert to baseline function as predicted by the patient's genotype, thus making the APRs corresponding to the PC-corrected phenotype, inaccurate. Additional considerations such as dose and the washout period, determined by the half-life of the phenoconverting drug and the substrate drug, need to be taken into account. This will ensure that dosing of new substrate medications metabolised by the “phenoconverted” CYP enzyme are safely introduced.

Therefore, we propose that a multidisciplinary team with expertise in PGx and clinical pharmacology is required to review PGx test results and the potential impact of PC when making prescribing decisions. In hospitals, a PGx Stewardship (PGS) program could be a feasible and pragmatic approach. The PGS team would advise hospital prescribers on appropriate pharmacotherapy based on PGx test results and PC status. Furthermore, this service could be replicated in the community by a collaborative effort between the General Practice Pharmacist and the GP (9). The community PGS team could address the complex needs of at-risk polypharmacy patients following their discharge from hospital back into primary care (30). Indeed, the biggest impact of the PGS could be in residential aged care facilities, which have recently been highlighted as a major location for polypharmacy, inappropriate prescribing, and lack of dose optimisation resulting in significant patient harm (31, 32).

Current approaches being trialled to address PC include the use of decision support systems to alert the prescriber at the point of prescribing. A recent publication by Bousman et al. describes a new free web-based tool that allows a prescriber or pharmacist to input genotype data and current medications to receive guidance on PC and appropriate PGx-based guideline recommendations (19). In the future, this type of approach may be utilised to address PC by the PGS team at the point of prescribing and dispensing to maximise the benefit of PGx in clinical practice.

This analysis aimed to assess the effect of PC on reporting of medicines with APRs, however, there were several limitations. The PGx testing panel utilised in the study did not include other key pharmacogenes with published CPIC or DPWG PGx-based guidelines (e.g., SLCO1B1, UGT1A1 and TPMT) and therefore the number of medicines with APRs is likely to be under reported. The PGx testing panel covered common alleles in the CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9 genes found in Caucasians, Asians, and Africans, however, some patients may harbour novel variants that will not be detected resulting in incorrect reporting of genotypes. The sample used for this analysis was limited by patients with listed medications at admission and discharge and perhaps a larger cohort is required to better assess the extent of PC on medications with APRs. The PGx study did not adequately assess and collect clinical outcome measures post PGx testing and as such these could not be included in this analysis. The study did not conduct pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis to measure PC due to ethical and clinical challenges with mental health patients. Pragmatically we used currently available best practice references to estimate the maximum possible PC effect based on the concomitant use of CYP inhibitors or inducers. Importantly, this approach does not take into account between patient pharmacodynamic differences that may affect or alter clinical outcome. Therefore, when interpreting the impact of PC clinically, utilising a PGS approach in combination with an understanding of patient response (efficacy and/or toxicity) will be optimal. Future research should be undertaken to understand how the dose and frequency of phenoconverting drugs affect the time course of CYP activity change either by detailed clinical PK studies or physiologically-based PK (PBPK) modelling and simulation (33–36). The latter approach with PBPK is particularly useful to answer questions about genotype-drug-drug interactions in vulnerable groups where PK studies are clinically and ethically challenging.

In conclusion, PGx is increasingly used to inform prescribing in clinical practice. However, PC is a dynamic problem that changes with concomitant medications and should be addressed, especially in older patients taking polypharmacy. We have shown in this analysis that PC can increase the number of APRs that can be applied in clinical practice. Further work is warranted to assess the clinical implications of PC and to establish a suitable approach to resolve this issue in the real-world setting.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Melbourne Health Human Research Ethics Committee, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, 3050. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SM wrote the first draft of this manuscript and was responsible for the analysis of the PGx study results. TP and CK contributed to the analysis of results and editing of the article. LS and DH contributed to the design of the original PGx study. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

The original study was funded by a grant from the Victorian Government Department of Business and Innovation.

SM and LS are employees and shareholders of myDNA Inc, a pharmacogenomic testing and interpretation company. TP provides a consultancy service to Sonic Genetics for the interpretation of pharmacogenomic test results.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We are grateful for the assistance and collaboration of all clinical and administrative staff at the Melbourne Health aged persons acute mental health units where the study was carried out; Australian Clinical Labs (formerly known as Healthscope pathology) for performing the genotype testing. LS and DH were previously affiliated with Melbourne Health during the PGx study (LS - Department of Genetic Medicine; DH - Northwestern Mental Health).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.724170/full#supplementary-material

1. Stegemann S, Ecker F, Maio M, Kraahs P, Wohlfart R, Breitkreutz J, et al. Geriatric drug therapy: neglecting the inevitable majority. Ageing Res Rev. (2010) 9:384–98. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.04.005

2. Scott I, Jayathissa S. Quality of drug prescribing in older patients: is there a problem and can we improve it? Intern Med J. (2010) 40:7–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02040.x

3. Collins SL, Carr DF, Pirmohamed M. Advances in the pharmacogenomics of adverse drug reactions. Drug Saf. (2016) 39:15–27. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0367-8

4. Cacabelos R, Cacabelos N, Carril JC. The role of pharmacogenomics in adverse drug reactions. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. (2019) 12:407–42. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2019.1597706

5. Polasek TM, Kirkpatrick CMJ, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Precision dosing to avoid adverse drug reactions. Ther Adv Drug Saf. (2019) 10:2042098619894147. doi: 10.1177/2042098619894147

6. Crews KR, Monte AA, Huddart R, Caudle KE, Kharasch ED, Gaedigk A, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline for CYP2D6, OPRM1, and COMT genotypes and select opioid therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2021). doi: 10.1002/cpt.2149. [Epub ahead of print].

7. Storelli F, Matthey A, Lenglet S, Thomas A, Desmeules J, Daali Y. Impact of CYP2D6 functional allelic variations on phenoconversion and drug-drug interactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2018) 104:148–57. doi: 10.1002/cpt.889

8. Ashiru-Oredope D, Sharland M, Charani E, McNulty C, Cooke J, Group AAS. Improving the quality of antibiotic prescribing in the NHS by developing a new Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme: start smart–then focus. J Antimicrob Chemother. (2012) 67(Suppl. 1):i51–63. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks202

9. Polasek TM, Rowland A, Wiese MD, Sorich MJ. Pharmacists in Australian general practice: an opportunity for expertise in precision medicine. Ther Adv Drug Saf. (2015) 6:186–8. doi: 10.1177/2042098615599947

10. Johnson JA, Caudle KE, Gong L, Whirl-Carrillo M, Stein CM, Scott SA, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for pharmacogenetics-guided warfarin dosing: 2017 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2017) 102:397–404. doi: 10.1002/cpt.668

11. Gaedigk A, Simon SD, Pearce RE, Bradford LD, Kennedy MJ, Leeder JS. The CYP2D6 activity score: translating genotype information into a qualitative measure of phenotype. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2008) 83:234–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100406

12. Hicks JK, Swen JJ, Gaedigk A. Challenges in CYP2D6 phenotype assignment from genotype data: a critical assessment and call for standardization. Curr Drug Metab. (2014) 15:218–32. doi: 10.2174/1389200215666140202215316

13. Mrazek DA, Biernacka JM, O'Kane DJ, Black JL, Cunningham JM, Drews MS, et al. CYP2C19 variation and citalopram response. Pharmacogenet Genom. (2011) 21:1–9. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328340bc5a

14. Theken KN, Lee CR, Gong L, Caudle KE, Formea CM, Gaedigk A, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline (CPIC) for CYP2C9 and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2020) 108:191–200. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1830

15. Preskorn SH, Kane CP, Lobello K, Nichols AI, Fayyad R, Buckley G, et al. Cytochrome P450 2D6 phenoconversion is common in patients being treated for depression: implications for personalized medicine. J Clin Psychiatry. (2013) 74:614–21. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07807

16. Borges S, Desta Z, Jin Y, Faouzi A, Robarge JD, Philips S, et al. Composite functional genetic and comedication CYP2D6 activity score in predicting tamoxifen drug exposure among breast cancer patients. J Clin Pharmacol. (2010) 50:450–8. doi: 10.1177/0091270009359182

17. Crews KR, Gaedigk A, Dunnenberger HM, Klein TE, Shen DD, Callaghan JT, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines for codeine therapy in the context of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) genotype. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2012) 91:321–6. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.287

18. Mostafa S, Kirkpatrick CMJ, Byron K, Sheffield L. An analysis of allele, genotype and phenotype frequencies, actionable pharmacogenomic (PGx) variants and phenoconversion in 5408 Australian patients genotyped for CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes. J Neural Transm (Vienna). (2019) 126:5–18. doi: 10.1007/s00702-018-1922-0

19. Bousman CA, Wu P, Aitchison KJ, Cheng T. Sequence2Script: a web-based tool for translation of pharmacogenetic data into evidence-based prescribing recommendations. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:636650. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.636650

20. Flockhart DA. Drug Interactions: Cytochrome P450 Drug Interaction Table. Indiana University School of Medicine (2007). Available online at: https://drug-interactions.medicine.iu.edu (accessed April 4, 2021).

21. Polasek TM, Lin FP, Miners JO, Doogue MP. Perpetrators of pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions arising from altered cytochrome P450 activity: a criteria-based assessment. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2011) 71:727–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03903.x

22. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-interactions-labeling/drug-development-and-drug-interactions-table-substrates-inhibitors-and-inducers (accessed April 4, 2021).

23. Hicks JK, Bishop JR, Sangkuhl K, Muller DJ, Ji Y, Leckband SG, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2015) 98:127–34. doi: 10.1002/cpt.147

24. Klomp SD, Manson ML, Guchelaar HJ, Swen JJ. Phenoconversion of cytochrome P450 metabolism: a systematic review. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:1–26. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092890

25. Lesche D, Mostafa S, Everall I, Pantelis C, Bousman CA. Impact of CYP1A2, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6 genotype- and phenoconversion-predicted enzyme activity on clozapine exposure and symptom severity. Pharmacogenomics J. (2019) 20:192–201. doi: 10.1038/s41397-019-0108-y

26. Page AT, Falster MO, Litchfield M, Pearson SA, Etherton-Beer C. Polypharmacy among older Australians, 2006-2017: a population-based study. Med J Aust. (2019) 211:71–5. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50244

27. Halli-Tierney AD, Scarbrough C, Carroll D. Polypharmacy: evaluating risks and deprescribing. Am Fam Physician. (2019) 100:32–8.

28. Rieckert A, Trampisch US, Klaassen-Mielke R, Drewelow E, Esmail A, Johansson T, et al. Polypharmacy in older patients with chronic diseases: a cross-sectional analysis of factors associated with excessive polypharmacy. BMC Fam Pract. (2018) 19:113. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0795-5

29. Jeppesen U, Gram LF, Vistisen K, Loft S, Poulsen HE, Brosen K. Dose-dependent inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 by citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and paroxetine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (1996) 51:73–8. doi: 10.1007/s002280050163

30. Freeman CR, Scott IA, Hemming K, Connelly LB, Kirkpatrick CM, Coombes I, et al. Reducing Medical Admissions and Presentations Into Hospital through Optimising Medicines (REMAIN HOME): a stepped wedge, cluster randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. (2021) 214:212–7. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50942

31. Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. Final Report: Care, Dignity and Respect. Summary and Recommendations. Canberra, ACT: Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (2021).

32. Elliott RA, Booth J. Problems with medicine use in older Australians: a review of recent literature. J Pharm Pract Res. (2014) 44:258–71. doi: 10.1002/jppr.1041

33. Polasek TM, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Virtual twins: understanding the data required for model-informed precision dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2020) 107:742–5. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1778

34. Sun L, von Moltke L, Rowland Yeo K. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modeling for predicting drug interactions of a combination of olanzapine and samidorphan. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. (2020) 9:106–14. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12488

35. Polasek TM, Tucker GT, Sorich MJ, Wiese MD, Mohan T, Rostami-Hodjegan A, et al. Prediction of olanzapine exposure in individual patients using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling and simulation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2018) 84:462–76. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13480

Keywords: pharmacogenomics, phenoconversion, CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9

Citation: Mostafa S, Polasek TM, Sheffield LJ, Huppert D and Kirkpatrick CMJ (2021) Quantifying the Impact of Phenoconversion on Medications With Actionable Pharmacogenomic Guideline Recommendations in an Acute Aged Persons Mental Health Setting. Front. Psychiatry 12:724170. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.724170

Received: 12 June 2021; Accepted: 27 July 2021;

Published: 19 August 2021.

Edited by:

Helge Frieling, Hannover Medical School, GermanyReviewed by:

Pedro Dorado, University of Extremadura, SpainCopyright © 2021 Mostafa, Polasek, Sheffield, Huppert and Kirkpatrick. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sam Mostafa, c2FtLm1vc3RhZmFAbW9uYXNoLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.