95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 04 August 2021

Sec. Psychological Therapy and Psychosomatics

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.716996

This article is part of the Research Topic Resilience in Chronic Disease View all 13 articles

Biyu Shen1,2,3†

Biyu Shen1,2,3† Haoyang Chen4†

Haoyang Chen4† Dongliang Yang5†

Dongliang Yang5† Ogbolu Yolanda3

Ogbolu Yolanda3 Changrong Yuan6

Changrong Yuan6 Aihua Du7

Aihua Du7 Rong Xu8

Rong Xu8 Yaqin Geng9

Yaqin Geng9 Xin Chen4

Xin Chen4 Huiling Li2*

Huiling Li2* Guang-Yin Xu1,2*

Guang-Yin Xu1,2*Background: The aim of this study was to examine how body image, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, the feeling of being anxious, depression, fatigue, quality of sleep, and pain influence the quality of life (QoL) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods: A multicenter cross-sectional survey with convenience sampling was conducted from March 2019 and December 2019, 603 patients with RA from five hospitals were evaluated using the Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Fatigue Severity Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Short Form 36 Health Survey, and Global Pain Scale. The relationship between quality of life and other variables was evaluated by using the structural equation model (SEM).

Results: A total of 580 patients were recruited. SEM fitted the data very well with a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.072. Comparative fit index of 0.966, and Tucker-Lewis index of 0.936. The symptoms and the normalized factor load of six variables showed that the normalized factor load of pain was 0.99.

Conclusions: The QoL model was used to fit an SEM to systematically verify and analyze the population disease data, biological factors, and the direct and indirect effects of the symptom group on the QoL, and the interactions between the symptoms. Therefore, the diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of RA is a long-term, dynamic, and complex practical process. Patients' personal symptoms, needs, and experiences also vary greatly. Comprehensive assessment of patients' symptoms, needs, and experiences, as well as the role of social support cannot be ignored, which can help to meet patients' nursing needs, improve their mood and pain-based symptom management, and ultimately improve patients' QoL.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory joint disease that may cause cartilage and bone damage, as well as significant disability (1). RA usually involves the small joints in the hands and feet and is characterized by joint pain, joint swelling, and synovial joint destruction (2). Its prevalence in adults in the USA and Europe is ~0.42–1.25% and 0.28–0.45% in China (3, 4).

Individuals with RA frequently report reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL), which is an indicator of the impact of one's health on his/her physical, emotional, and social well-being (5). RA is very painful and affects the social activities of the patient. Many patients have been sick since childhood, this painful experience may be associated with psychosocial impairment and may influence the negative outcomes in RA (6). Patients with RA show systemic symptoms, such as pain, stiffness, muscle weakness, fatigue, and joint swelling; all of these might cause irreversible destruction of joints or deformities accompanied by physical disability when the disease progresses; all of the abovementioned symptoms are the most common causes of continual pain and impaired functioning (7), and significantly decrease a person's mobility, productivity, and QoL (8, 9).

Pain is the symptom that the patient feels most directly. RA patients also have a higher incidence of depression (10). More than half of the patients experience fatigue. Fatigue is described as either physical or mental fatigue, which combined may lead to disability. Patients feel tired, depressed, or frustrated, and are unable to complete their daily tasks (11, 12). Fatigue had a substantial influence on the patients' lives, while pain was the dominant factor in the fatigue experience and degree (13). Poor sleep quality is common in patients with RA and may lead to disease aggravation and decreased HRQoL. The prevalence of body image disturbance (BID) is 24.2%, and poor social functioning and anxiety are also present (14). Besides, increasing disease severity has been associated with worsening disability, pain, fatigue, QoL, and work and activity impairment (15).

Moreover, RA is related to reverse characteristics in terms of demographics, clinical features, as well as psychological status. An uncertain future concerning physical ability, work and employment status, family responsibilities, and social activities can be difficult to face, especially in individuals with RA. RA patients are at higher risk of developing comorbidities (16), which are also associated with advanced age. In China, patients with RA have a similar prevalence of comorbidities when compared to those in other Asian countries. Advanced age and long disease duration are possible risk factors for comorbidities, which may increase mortality and affect treatment strategies, resulting in worse outcomes (17, 18). Patients with RA tend to have a higher risk for many comorbidities (19, 20).

Improving patients' symptoms can improve their quality of life. Depression is a major determinant of functional capacity in RA (21). Effective social support may relieve patients' fatigue, which is related to patients' disease activity and QoL (22).

Many studies have considered a simple associative relationship between two of the following variables or have evaluated the variables as a single item instead of one with multiple dimensions (23–25): pain, fatigue, depression, sleep quality, and QoL impact. There has been no systematic and comprehensive analysis of the relationship between patients' demographic data and symptoms, and the causal relationship between RA symptoms and QoL. It is possible to evaluate and manage patients comprehensively and provide a theoretical basis to formulate appropriate objective interventions to improve QoL.

However, improving the quality of life does not always accompany QoL improvement. Physical aspects are commonly evaluated as most important and are related to a patient's physical condition only as a consequence of illness and treatment.

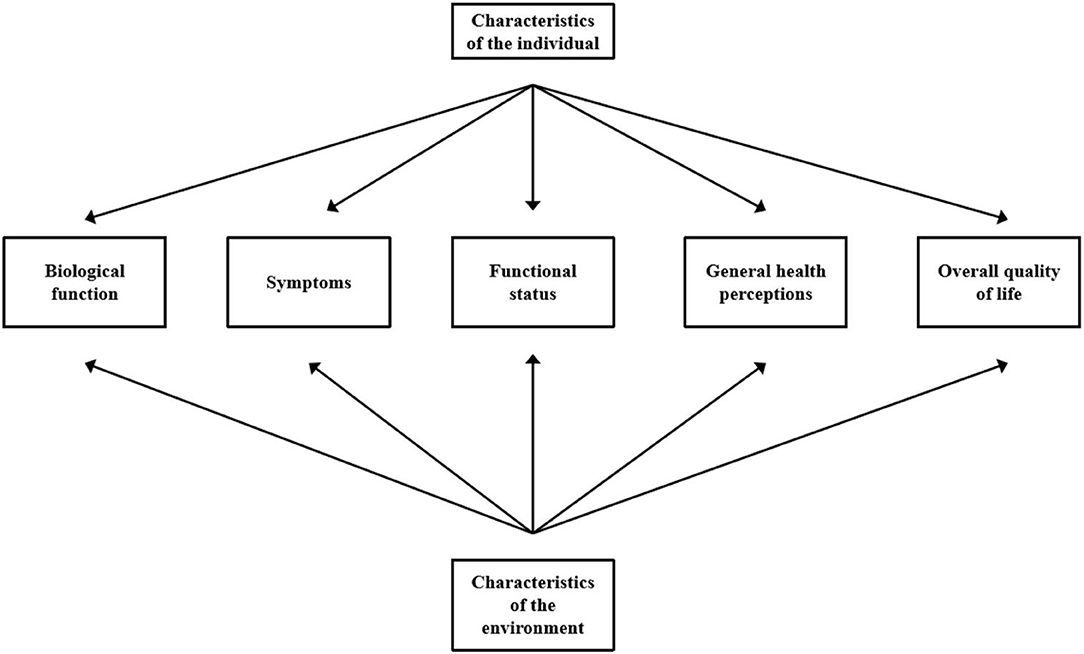

The framework of this study is derived from QoL research; the current challenge is to devise a model to clarify the elements of HRQoL and relationships among them. Wilson and Cleary have suggested specific causal relationships between health concepts encompassing biological, social, and psychological variables (Figure 1) (26).

Figure 1. Revised Wilson and Cleary model of health-related quality of life. Adapted from “Linking Clinical Variables with Health-Related Quality of Life: A Conceptual Model of Patient Outcomes,” by Wilson and Cleary (26). Copyright by JAMA. Used with permission.

A linear progression without dominant reciprocal effects or links between nonadjacent concepts has been proposed. Wilson and Cleary's model outlines potential causal relationships between the variables that play a major role in the origins of HRQoL.

Based on the above rationale, we aimed to: (1) describe the current status of HRQoL in patients with RA, including parameters such as gender socioeconomic status, and disease characteristics and explore their relevance; (2) perform an exploratory analysis of relevant parameters including the effects of pain, fatigue, and physical image disorders, depression, sleep quality, disease activity, HRQoL, and the interaction between multiple variables; (3) assess HRQoL and determine which factors, based on the Wilson and Cleary model, contribute to the prediction of HRQoL among patients with RA; and (4) estimate the potential impact of success on RA-HRQoL to provide a theoretical basis for effective interventions against identified factors.

A multicenter cross-sectional study with a convenience sampling method was conducted. Patients with RA were recruited from five hospitals between March 2019 and December 2019. The inclusion criteria included RA diagnosis according to the American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria, age ≥18 years, able to interact in Chinese efficiently, and willing to provide written informed consent. People who have cognitive impairment or current severe diseases, such as cancer and stroke, were not included.

Altogether, 603 patients with RA were consecutively invited to participate in the cross-sectional study, and 580 (96.2%) were eventually included in the analysis. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to determine the correlation between variables. The relationship between quality of life and other variables was evaluated by using the Structural Equation Model (SEM).

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Soochow University (SUDA20200225H11). All subjects meeting the criteria were asked to participate. Questionnaires were distributed by two well-trained researchers to the eligible participants. All participants were informed about (a) the aim and significance of this research, (b) confidentiality of patient data, and (c) that their engagement was totally voluntary, and they could withdraw from the research at any time. All data in the questionnaires that were completed were made confidential. A unique identification number was placed at the upper portion of the questionnaire.

The Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire comprised the following seven items (27): recognized concern, preoccupation, avoidance of role, the emotional suffering of their own appearance, as well as appearance impairment in social, educational, and work function. The Cronbach's alpha value was 0.877.

The patient's disease activity was measured using the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) (28). Four aspects were included in this questionnaire, which were calculated by using a software program that measures 28 swollen joint counts, 28 tender joint counts, the rate of erythrocyte sedimentation rate, as well as the patient's recognition of disease activity from 0 mm (not active at all) to 100 mm (very active).

Two sub-scales were included in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which was used for measuring anxiety and depression over the prior month (29). Seven items could be found in each sub-scale. This evaluation tool has been used in large-scale studies. The Cronbach's alpha value of the questionnaire was 0.850, while the intraclass connection coefficient was 0.900.

The Fatigue Severity Scale questionnaire was used to assess fatigue severity (FSS) (30). It examined nine items; the average of all items served as the overall score, with the higher scores, indicating greater or severe fatigue. This tool has high reliability, high sensitivity, and internal consistency in fatigue evaluation. The Cronbach's alpha value of the questionnaire was 0.852.

The quality of sleep was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (31). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index consisted of 19 questions, which included seven aspects. Each aspect can have a score of 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty), with the total score ranging from 0 to 21. The Cronbach's alpha value of the questionnaire was 0.796.

The Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) was used to assess QoL (32). It evaluated eight aspects. The scores ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health status. There were two forms of scores: the Z-transformed scores and the normalized domains scores. They were divided into physical components summary (PCS) and mental components summary (MCS) scores, with higher scores indicating better health status. The Chinese version of SF-36 has a Cronbach's alpha of 0.720 to 0.880.

The Global Pain Scale (GPS) includes 20 items related to participants' chronic pain experience (33). Participants indicated their responses on an 11-point scale (from 0 to 10). There were four subscales assessing pain, feelings, clinical outcomes, and activities. For the pain subscale, participants indicated the degree of pain felt currently along with their best, worst, and average pain during the last week, as well as whether they have felt less pain in the last week. The total Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.984.

Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) (34), the Chinese version of SSRS, developed by Xiao Shuiyuan in 1994, was used to identify the social support status. SSRS, which consists of 10 items and three dimensions, was selected for its proven reliability and validity. The Cronbach's alpha of the total scale and subscales ranged from 0.825 to 0.896.

SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. For measurement data, we first performed a normality test. If the data were normally distributed, measurement data were expressed by using means and standard deviations (SDs); if the data were not normally distributed, then the measurement data were expressed by the median and interquartile range; for categorical data, rates or composition ratios were used. R language (Vienna, Austria) was used to deal with missing values, using the Mice package (Multiple Imputation).

The SEM of SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for path analysis. The parameters of the model were estimated by the maximum likelihood method. First, the initial path model was adjusted based on two criteria. One was to delete insignificant paths, and the other was to use the modification index to establish the correlation between some residuals using the combination of professional knowledge to gain the best model.

A total of 603 patients with RA were consecutively invited to participate, and 580 (96.2%) were eventually included in the present study: 255 (44.0%) from Nantong, 120 (20.7%) from Henan, 101 (17.4%) from Suzhou, 55 (9.5%) from Changzhou, and 49 (8.4%) from Shanghai.

There were 603 questionnaires in total, of which 23 were considered invalid (e.g., with missing answers, highly similar options). The response rate of the questionnaire was 96.2% (580/603) and the proportion of missing values for basic information was 0.7%, with missing information in area (1/580), age (2/580), and height (1/580); the proportion of missing values for other variables were as follows: BID 0.5% (3/580); social support 0.9% (5/580); sleep 1.0% (6/580); pain 0.5% (3/580); medication compliance 0.3% (2/580); and QoL 0.7% (4/580).

Table 1 shows the participants' baseline characteristics. The mean age of participants was 51.04 years (SD = 24.65), and 88.4% were female. Overall, 49.3% lived in a suburb. Most patients (91.2%) were married. Only 13.8% of the patients received education for ≤ 9 years. Most (72.2%) were employed, and 31.7% had yearly per capita incomes of <15,000 RMB. The mean disease duration was 4 years. Approximately 14.7% of patients had hypertension, 5% had diabetes, 6% had coronary heart disease, 3.8% had nephropathy, and 12.1% had another cardiopulmonary disease.

The mean (SD) of anxiety and depression scores were 10.67 (2.38) and 10.01 (2.39), respectively. The mean (SD) for each scale was 38.92 (7.35) for Fatigue Severity Scale, 26.00 (14.83) for BIDQ, 5.00 (1.50) for DAS28, 10.47(3.01) for PSQI, 55.91 (17.70) for Global Pain Scale, 177.26 (62.19) for PCS, 217.8 (64.63) for MCS, 436.57 (127.02) for the SF-36, and 37.48 (5.34) for SSRS.

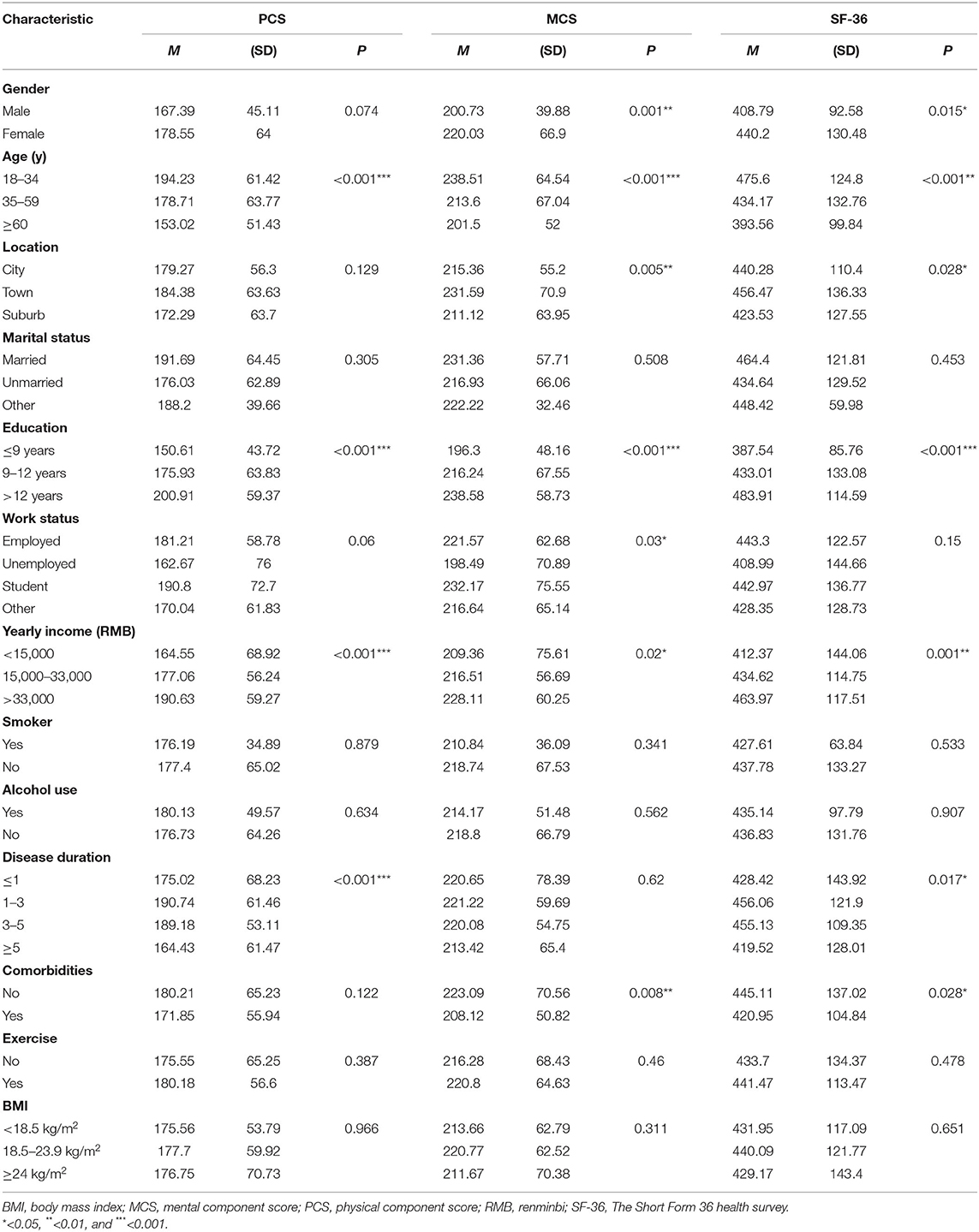

In Table 2, the PCS, MCS, and SF-36 total scores in our study were presented according to the sociodemographic and characteristics of the patients.

Table 2. Subgroup comparisons of 36-item short form survey physical component scores, mental component scores, and total scores.

The pain score had a significant correlation with DAS28, fatigue, sleep, and body image (p < 0.01). Body image score had a significant correlation with DAS28, depression, fatigue, sleep (p < 0.01). Sleep score had a significant correlation with depression, fatigue (p < 0.01).

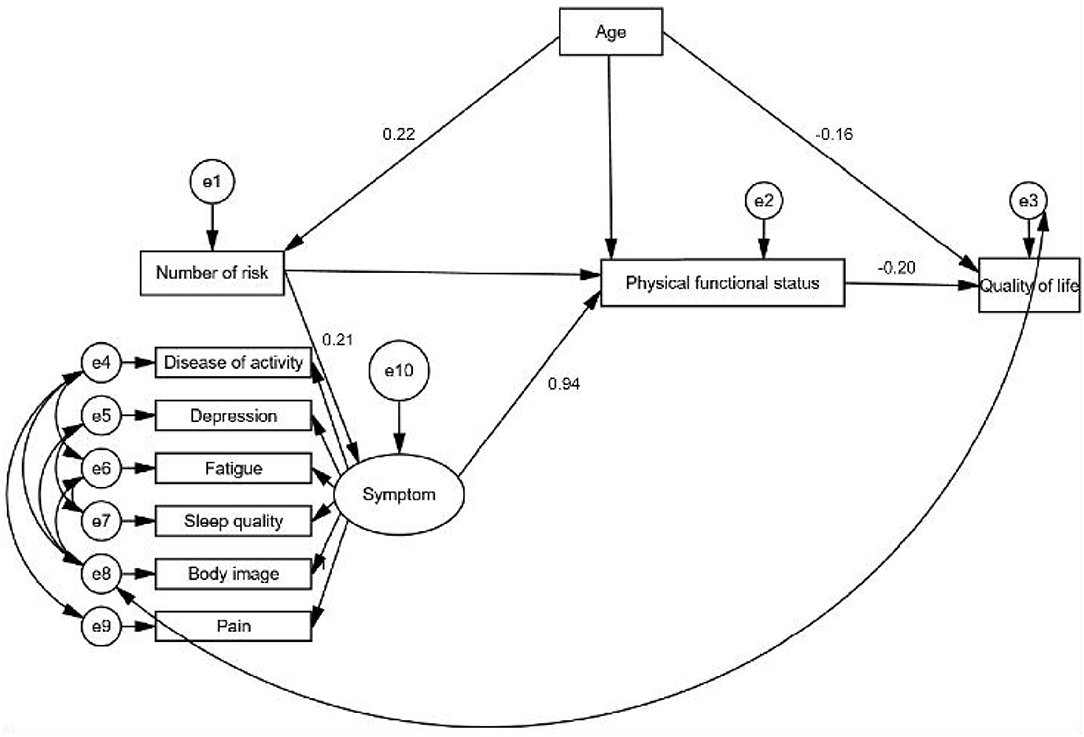

Figure 2 shows significant pathways in the final HRQoL model. We have successively removed the unimportant paths. Modification indices indicated no modifications. Figure 2 shows the final model. The indices of the goodness-of-fit showed that the final model was an excellent fit to the data with root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.072, goodness-of-fit index of 0.968, adjusted goodness of fit index of 0.928, normed fit index of 0.955, relative fit index of 0.916, incremental fit index of 0.936, and comparative fit index of 0.966. The direct, indirect, as well as the overall effects of predictors on HRQoL are demonstrated in Figure 2. Age and PF had an indirect effect on HRQoL. Among symptoms that had indirect effects on HRQoL through the physical function status, age exerted a direct influence on HRQoL and an indirect influence on HRQoL via PF. The direct effect value between QoL paths and the path correlation coefficient between symptoms are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Goodness of fit of structural equation models of variables in a cross-sectional study of health-related quality of life. (1) Latent variable: biological and physiological status; measured variables: number of risk factors (e.g., hyperlipidemia, diabetes). (2) Latent variable: symptom status; measured variable: BIDQ, DAS28, HADS, FSS, PSQI, and GPS. BIDQ, Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire; DAS28, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; FSS, Fatigue Severity Scale questionnaire; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; GPS, Global Pain Scale. (3) Latent variable: physical functional status; measured variable: physical function status was based on the total score of “go to the store,” “do chores in my home,” “enjoy my friends and family,” “exercise,” and “participate in my favorite hobbies” in GPS. GPS, Global Pain Scale. (4) Latent variable: QoL; measured variable: SF-36 total score. QoL, quality of life; SF-36, Short Form 36 Health Survey. (5) Latent variable: characteristics of the environment; measured variable: social support. (6) Latent variable: characteristics of the individual measured variable: demographic characteristics (age, education, income, etc).

Fitting indicators of the model: ratio of chi square/df = 3.960; RMSEA = 0.072; goodness-of-fit index = 0.968; adjusted goodness of fit index = 0.928; normed fit index = 0.955; relative fit index = 0.916; incremental fit index = 0.966; Tacker-Lewis index = 0.936; and comparative fit index = 0.966. The coefficients of related factors were standardized, and the standardized regression coefficients were sorted. Symptoms and the standardized factor load of variables showed that the standardized load of pain was as high as 0.99, which is the most important factor affecting QoL. The standardized load of body image was 0.63, the standardized load of fatigue was 0.25, the standardized load of sleep quality was 0.24, the standardized load of depression was 0.07.

Wilson and Cleary's model-associated factors with global HRQoL environment variables were assessed in this study. This is the first large-sample multi-center cross-sectional survey using multiple variables to investigate the associations between the individual characteristics of patients with RA and overall HRQoL in China using SEM. The final model provided here shows an association between clinical variables, such as other underlying diseases, that mediate an individual's experience with actual symptoms, physical functioning, and general health on HRQoL. SEM allows the simultaneous assessment of the effects of personal and environmental characteristics on potential variables in the model. Our study and previous studies show that patients with RA often experience chronic pain and functional disabilities, including a high incidence of depression, body image disorders, fatigue, and sleep disorders with a decline in patients' QoL (35).

In the analysis of the subgroup, HRQoL scores were higher (indicating better QoL) in men than in women, the employed than in the unemployed, the college-educated individuals than in those with less educational levels, and in those in third-highest rank of income (¥15,000). The marital statuses were not associated with the HRQoL overall score, PCS, or MCS. These results are consistent with Gong's study findings and are worthy of attention (36). There were also significant differences in the QoL of patients with RA in different subgroups of age, disease duration, and comorbidities, which is consistent with Zeng's et al.'s study (35).

The presence of comorbidities may increase mortality in patients with RA. Further, treatment strategies may be affected, leading to worsening conditions. Fitting the SEM of the QoL of patients with RA in our study showed similar results for latent variables of biological factors, and both the number of comorbidities and risks, including coronary heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, and fractures. Accordingly, the prediction and management of comorbidities are increasingly important in the long-term management of RA (37). What should not be ignored is that age as an individual characteristic not only had a constant effect on physical functioning but also on HRQoL. These data provide information about the prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and other characteristics of selected comorbidities, which may help identify comorbidities and management strategies.

Joint pain is often the first symptom. The definition of pain has been revised to “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with the diagnosis, treatment as well as rehabilitation of RA shows a long-term, dynamic together with complicated pragmatic procedure with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” (38). In addition, there is an involvement of sensory perception, which is implicated in emotional processes and negative outcomes. Importantly, the unique sensory processing patterns of individuals have been reported as crucial factors in determining negative outcomes in the clinical practice and play a role in the prediction of their QoL (39). In our study, in order to fully evaluate the multidimensional and complex pain of RA patients, pain assessment was performed using Global Pain Scale; this is the first time that a comprehensive pain assessment was applied to RA patients. It is also an innovative approach used in this study. In the SEM results, a better fit may also better reflect the patient's complications, in terms of pain, feelings, outcomes, and activities. Chronic disease, such as RA, is characterized by its uncertain course, and its frequent confrontation with pain and fatigue, and the possibility of becoming disabled influence the patients' psychological well-being. Notably, the results of our Pearson's correlation analysis showed that pain correlates with disease activity, fatigue, sleep quality, and physical image disorders, and in the results of the SEM, the standardized load of pain is up to 0.99, which is sufficient to prove that pain plays a decisive role in QoL. This suggests that we should pay attention to the pain symptoms and related symptom groups, strengthen the symptom management of RA patients, and improve the QoL of RA patients.

Disease activity was assessed by using the DAS28. Our results showed that the DAS28 score was 5.00 (1.50), which was more severe than the results of previous research (40), SEM shows that disease activity interacts with fatigue, BID, and pain, and affects body function. These results are completely consistent with the results of the Pearson's correlation analysis.

In patients with RA, fatigue is considered the most common extra-articular symptom other than pain. Among patients with RA. Our study found that 64.8% of patients considered fatigue the most important issue. In the correlation analysis, fatigue was associated with pain, BID, and sleep quality. In SEM, it was also shown to interact with increased disease activity, with a standardized load factor of 0.25, ranking fourth among the symptom groups. This is similar to the findings of Gong's study (36). Pain is the dominant factor in the experience and degree of fatigue. Disease activity is positively correlated to fatigue. Thus, fatigue has been shown to cause notable adverse consequences and to affect every aspect of daily life, bringing a considerable human and economic burden to QoL, thereby reducing the overall health of patients (41).

Psychological well-being refers to an individual's mood in a global sense. When someone is confronted with uncertainty, threat, and ambiguity, this may provoke feelings of depression. Our results show that 76.4% of patients with RA experienced depression. Patients with RA and depression had significantly lower medication compliance, impaired physical function, sleep quality, and QoL than those without depression (42). Sleep disturbances can be often observed in patients who have long-term diseases; meanwhile, the prevalence of poor sleep is higher in patients with RA than in those without RA.

Body image (BI) is defined as “the attitudes and perceptions of individuals toward their appearance and their beliefs and others with respect to their body.” It is strongly influenced by one's health and may be associated with abnormal coping behavior, psychopathology, poor outcomes, and HRQoL (43). As RA progresses, some patients may have irreversible damage, such as joint deformities, reduced restrictions on movement, and function, which may lead to psychological problems, such as human BID (44). Our results showed that almost all patients observe their BI and have different degrees of BID. In the correlation analysis, BID was associated with disease activity, fatigue, depression, sleep quality, pain, and, interestingly, SEM. In addition to indirect effects on QoL, BI directly affects the QoL. The standard factor load is 0.63, which plays a decisive role in pain. It is likely to be a mediating effect in the RA QoL model. The important conclusion of the study is also the innovation of this study, which deserves more attention from rheumatologists.

The QoL of patients with RA is a complex systemic response, which is determined by the patient's biological characteristics. There are different multivariable symptom group interactions, and it is not possible to simply explore the correlations of several variables. A systematic study is needed, and important factors should be assessed by using multi-factor analysis and SEM to verify its causality. In our research hypothesis, social support played a role in the QoL model as an environmental feature but it was included in the final model verification, differing from the results of another study on the QoL of patients with RA (45). It may be that their research is more related to the factorial analysis of its relevance to the social quality, but it is similar to Gong's results (36). Social support is a long-term process, associated with factors, such as the route and frequency of social support, and patient demand. This suggests that we should conduct a comprehensive and dynamic evaluation of the entire process in the patient support system, as needed while paying attention to the selected methods and durations to improve the QoL of patients with RA.

There are some limitations to this study. First, self-reporting was used to assess the patient's condition. It is difficult to avoid recall and reporting biases, which may have affected the association between variables. Second, this was a multi-center cross-sectional survey. Future research should focus longitudinally on the QoL of patients with RA and explore intermediary factors affecting their QoL, Qualitative research will be combined with patient interviews to focus on the vertical regularity of the deterioration of QoL, the needs, cognition, and experience in the course of the disease. We should also pay attention to the influence of environmental factors, coping style, and symptom management on patients' quality of life to provide better evidence to establish effective interventions.

In conclusion, this study analyzed the QoL of patients with RA in China through a multi-center survey. The QoL model was used to fit an SEM to systematically verify and analyze the population disease data, biological factors, and the direct and indirect effects of the symptom group on the QoL, and the interactions between the symptoms. Our results showed that age and comorbidities would directly influence QoL, pain, BI, disease activity, fatigue, sleep quality as and depression, which are ranked according to whether the effects are important to the patient's physical function and on the patient's QoL. BI has a direct impact on QoL. Therefore, the RA diagnosis and treatment and rehabilitation of RA patients is a long-term, dynamic and complex practical process. Patients' personal symptoms, needs, and experiences also vary greatly. Comprehensive assessment of patients' symptoms, needs, and experiences, at the same time, the role of social support cannot be ignored, as they can help to meet patients' nursing needs, improve their mood and pain-based symptom management, and ultimately improve patients' QoL.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary files, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Ethics Committee of Soochow University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

BS and HC performed the experiment, analyzed the data, and prepared the figures and the manuscript. BS, HC, AD, RX, YG, and XC collected the data. DY analyzed the data. G-YX, HL, OY, and CY designed, supervised the experiments, and finalized the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript.

The study was supported by grants from the Jiangsu Provincial Commission of Health and Family Planning Foundation (Grant Number Z201622), Jiangsu Province 333 high level talent training project Foundation (Grant Number BRA2016198), Jiangsu Province Youth Medical Talent Foundation (Grant Number QNRC2016409), Jiangsu Province six talent peak high-level personnel training project foundation (Grant Number WSN-234), Nantong Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant Number MS12019007), Post-graduate Research and Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant Number KYCX20_2685), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 81920108016 and 31730040).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We wish to thank all the participants involved in the study.

QoL, quality of life; SEM, structural equation modeling; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; BID, body image disturbance; DAS28, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; SF-36, Short Form 36 Health Survey; PCS, physical components summary; MCS, mental components summary; SSRS, Social Support Rating Scale; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; RMB, renminbi; BMI, body mass index.

1. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. (2016) 338:2023–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8

2. Scott DL, Symmons DP, Coulton BL, Popert AJ. Long-term outcome of treating rheumatoid arthritis: results after 20 years. Lancet. (1987) 1:1108–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)91672-2

3. Alamanos Y, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA. Incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis, based on the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. (2006) 36:182–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.08.006

4. Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TWJ. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. (2010) 376:1094–108. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60826-4

5. Matcham F, Scott IC, Rayner L, Hotopf M, Kingsley GH, Norton S, et al. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. (2014) 44:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.001

6. Serafini G, Canepa G, Adavastro G, Nebbia J, Belvederi Murri M, Erbuto D, et al. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. (2017) 8:149. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00149

7. Schelin M, Westerlind H, Lindqvist J, Englid E, Israelsson L, Skillgate E, et al. Widespread non-joint pain in early rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. (2021) 50:271–9. doi: 10.1080/03009742.2020.1846778

8. Alcaide L, Torralba AI, Eusamio Serre J, García Cotarelo C, Loza E, Sivera F. Current state, control, impact and management of rheumatoid arthritis according to patient: AR 2020 national survey. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2020.10.006. [Epub ahead of print].

9. Szewczyk D Sadura-Sieklucka T Sokołowska B Ksiezopolska-Orłowska K. Improving the quality of life of patients with rheumatoid arthritis after rehabilitation irrespective of the level of disease activity. Rheumatol Int. (2021) 41:781–6. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04711-4

10. Fakra E, Marotte H. Rheumatoid arthritis and depression. Joint Bone Spine. (2021) 88:105200. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2021.105200

11. Campbell RC, Batley M, Hammond A, Ibrahim F, Kingsley G, Scott DL. The impact of disease activity, pain, disability and treatments on fatigue in established rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. (2012) 31:717–22. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1887-y

12. Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E, van de Laar MA. New insights into the experience of fatigue among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Ann Rheum Dis. (2010) 69:895–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.118067

13. Madsen SG, Danneskiold-Samsoe B, Stockmarr A, Bartels EM. Correlations between fatigue and disease duration, disease activity, and pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol. (2016) 45:255–61. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2015.1095943

14. Zhou C, Shen B, Gao Q, Shen Y, Cai D, Gu Z, et al. Impact of rheumatoid arthritis on body image disturbance. Arch Rheumatol. (2019) 34:79–87. doi: 10.5606/ArchRheumatol.2019.6738

15. da Rocha Castelar Pinheiro G, Khandker RK, Sato R, Rose A, Piercy J. Impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality of life, work productivity and resource utilisation: an observational, cross-sectional study in Brazil. Clin Exp Rheumatol. (2013) 31:334–40.

16. Jin S, Li M, Fang Y, Li Q, Liu J, Duan X, et al. Chinese Registry of rheumatoid arthritis (CREDIT): II. prevalence and risk factors of major comorbidities in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. (2017) 19:251. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1457-z

17. Norton S, Koduri G, Nikiphorou E, Dixey J, Williams P, Young A. A study of baseline prevalence and cumulative incidence of comorbidity and extra-articular manifestations in RA and their impact on outcome. Rheumatology (Oxford). (2013) 52:99–110. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes262

18. Young A, Koduri G, Batley M, Kulinskaya E, Gough A, Norton S, et al. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Increased in the early course of disease, in ischaemic heart disease and in pulmonary fibrosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). (2007) 46:350–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel253

19. Meune C, Touzé E, Trinquart L, Allanore Y. High risk of clinical cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis: levels of associations of myocardial infarction and stroke through a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. (2010) 103:253–61. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2010.03.007

20. Amin S, Gabriel SE, Achenbach SJ, Atkinson EJ, Melton LJ III. Are young women and men with rheumatoid arthritis at risk for fragility fractures? A population-based study. J Rheumatol. (2013) 40:1669–76. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121493

21. Isnardi CA, Capelusnik D, Schneeberger EE, Bazzarelli M, Berloco L, Blanco E, et al. Depression is a major determinant of functional capacity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. (2020) 24:1506. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001506

22. Xu N, Zhao S, Xue H, Fu W, Liu L, Zhang T, et al. Associations of perceived social support and positive psychological resources with fatigue symptom in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0173293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173293

23. Albayrak Gezer I, Balkarli A, Can B, Bagçaci S, Küçükşen S, Küçük A. Pain, depression levels, fatigue, sleep quality, and quality of life in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Turk J Med Sci. (2017) 47:847–53. doi: 10.3906/sag-1603-147

24. Nerurkar L, Siebert S, McInnes IB, Cavanagh J. Rheumatoid arthritis and depression: an inflammatory perspective. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:164–73. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30255-4

25. Hughes M, Chalk A, Sharma P, Dahiya S, Galloway J. A cross-sectional study of sleep and depression in a rheumatoid arthritis population. Clin Rheumatol. (2021) 40:1299–305. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05414-8

26. Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. (1995) 273:59–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.1.59

27. Cash TF, Grasso K. The norms and stability of new measures of the multidimensional body image construct. Body Image. (2005) 2:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.007

28. Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. (1995) 38:44–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380107

29. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. (2002) 52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3

30. Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. (1989) 46:1121–3. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022

31. Liu X, Tang M, Hu L. Reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. Chin J Psychiatry. (1996) 29:103–7.

32. Li L, Wang H, Shen Y. Chinese SF-36 Health Survey: translation, cultural adaptation, validation, and normalisation. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2003) 57:259–63. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.259

33. Gentile DA, Woodhouse J, Lynch P, Maier J, McJunkin T. Reliability and validity of the Global Pain Scale with chronic pain sufferers. Pain Phys. (2011) 14:61–70. doi: 10.36076/ppj.2011/14/61

34. Xiao S. The theoretical basis and research applications of the social support scale. J Clin Psychiatry. (1994) 4:98–100.

35. Zeng X, Zhu S, Tan A, Xie XP. Disease burden and quality of life of rheumatoid arthritis in China: a systematic review. Chin J Evid Based Med. (2013)13:300–7.

36. Gong G, Mao J. Health-related quality of life among Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the predictive roles of fatigue, functional disability, self-efficacy, and social support. Nurs Res. (2016) 65:55–67. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000137

37. Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, Heslinga M, McInnes IB, Peters MJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. (2017) 76:17–28. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209775

38. George J. What is pAIN?-For the First Time in 40 Years, IASP Revises Pain's Definition. Available online at: https://www.medpagetoday.com/neurology/painmanagement/87628 (accessed July 17, 2020).

39. Serafini G, Gonda X, Pompili M, Rihmer Z, Amore M, Engel-Yeger B. The relationship between sensory processing patterns, alexithymia, traumatic childhood experiences, and quality of life among patients with unipolar and bipolar disorders. Child Abuse Negl. (2016) 62:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.013

40. Gullick NJ, Ibrahim F, Scott IC, Vincent A, Cope AP, Garrood T, et al. Real world long-term impact of intensive treatment on disease activity, disability and health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. (2019) 3:6. doi: 10.1186/s41927-019-0054-y

41. Taylor PC, Moore A, Vasilescu R, Alvir J, Tarallo M. A structured literature review of the burden of illness and unmet needs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a current perspective. Rheumatol Int. (2016) 36:685–95. doi: 10.1007/s00296-015-3415-x

42. Xia Y, Yin R, Fu T, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Guo G, et al. Treatment adherence to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2016) 10:735–42. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S98034

43. Wright F, Boyle S, Baxter K, Gilchrist L, Nellaney J, Greenlaw N, et al. Understanding the relationship between weight loss, emotional well-being and health-related quality of life in patients attending a specialist obesity weight management service. J Health Psychol. (2013) 18:574–86. doi: 10.1177/1359105312451865

44. Monaghan SM, Sharpe L, Denton F, Levy J, Schrieber L, Sensky T. Relationship between appearance and psychological distress in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. (2007) 57:303–9. doi: 10.1002/art.22553

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, quality of life, body image, pain, depression

Citation: Shen B, Chen H, Yang D, Yolanda O, Yuan C, Du A, Xu R, Geng Y, Chen X, Li H and Xu G-Y (2021) A Structural Equation Model of Health-Related Quality of Life in Chinese Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Psychiatry 12:716996. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.716996

Received: 30 May 2021; Accepted: 13 July 2021;

Published: 04 August 2021.

Edited by:

Zeng-Jie Ye, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, ChinaReviewed by:

Mohsen Khosravi, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, IranCopyright © 2021 Shen, Chen, Yang, Yolanda, Yuan, Du, Xu, Geng, Chen, Li and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guang-Yin Xu, Z3Vhbmd5aW54dUBzdWRhLmVkdS5jbg==; Huiling Li, bGhsODU0M0AxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.