94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Psychiatry , 09 August 2021

Sec. Behavioral and Psychiatric Genetics

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.714093

Sergey Tereshchenko1*

Sergey Tereshchenko1* Edward Kasparov1

Edward Kasparov1 Svetlana Zobova1,2

Svetlana Zobova1,2 Marina Smolnikova1

Marina Smolnikova1 Lidia Evert1

Lidia Evert1 Nadezhda Semenova1

Nadezhda Semenova1 Olga Zaitseva1

Olga Zaitseva1 Margarita Shubina1

Margarita Shubina1 Nina Gorbacheva1

Nina Gorbacheva1 Ludmila Lapteva1

Ludmila Lapteva1Background: CD38 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that regulates oxytocin (OT) production and influences social interactions. The oxytocin receptor (OXTR) has been studied intensively regarding its association with human psychosocial functions. Many studies have demonstrated a link between CD38 rs3796863 and OXTR rs53576 polymorphic regions and psychosocial characteristics as well as various psychiatric disorders in adolescents. Some studies, however, have reported null findings.

Methods: The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a brief psychopathologic screening tool recommended for detecting psychosocial problems and psychiatric disorders in adolescents. The current field school-based study, conducted among urban Siberian adolescents (n = 298 aged 12–18), explored the SDQ scales in relation to polymorphisms of the CD38 and the OXTR genes (rs3796863 and rs53576, respectively).

Results: None of the studied genotypes were associated with the SDQ results for the complete sample with presumed statistical power as 0.80 to detect a medium-size effect (Cramer's V = 0.3) at α = 0.0083. Post-hoc analysis in subgroups showed that OT pathway high activity may cause some negative consequences, such as emotional instability in older (aged 15–18) adolescent boys who are carriers of the rs53576 GG variant.

Conclusion: Variations at the CD38 rs3796863 and OXTR rs53576 loci were not associated with psychosocial characteristics of adolescents assessed with the SDQ. In studies with a similar design, we recommend replication with larger samples and greater power to detect small effects, especially in age–sex subgroups of adolescents.

Oxytocin (OT) is a nonapeptide neurohormone mainly produced in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus. Large-cell oxytocin-producing neurons of the hypothalamus have axonal connections with the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland, where OT is deposited and subsequently released into the bloodstream with the implementation of its peripheral action occurring via the activation of specific receptors. Additionally, OT has a direct central effect on various parts of the brain, mediated through its dendritic release followed by diffusion into adjacent areas.

The primary hormonal role of OT is to regulate the processes of gestation, labor, and lactation, as well as the establishment of social bonds from infancy through to adolescence and adult life. Its central action constitutes an essential part of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes (1). Moreover, OT takes part in the regulation of eating and sexual behavior (2, 3), mechanisms of visceral hypersensitivity (4), and pain perception (5).

In recent years, the genetic aspects of the regulation of the production and reception of OT in various psychopathological conditions in adolescents have attracted the close attention of researchers. Studies of the genetic basis for the oxytocinergic system have mainly focused on single nucleotide variants of the OXTR gene (rs53576, rs2254298), the OXT gene (rs2740210, rs4813627, rs4813625), and the CD38 gene (rs3796863, rs6449197) (6). Many studies have shown the association between these variants and aggressiveness, poor tolerance to psychological stress (7), as well as suicidal tendencies (8), problems with behavior, the parent–child relationship (9, 10), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (11). A large number of studies have demonstrated the existence of a link between different polymorphic regions of the OXTR as well as the CD38 genes and various psychiatric diseases, including autism spectrum disorders [analyzed in detail in the reviews by Feldman et al. (6) and Cataldo et al. (12)].

CD38 is a transmembrane glycoprotein with adenosine diphosphateribosyl-ribosyl cyclase activity, which plays a vital role in regulating hormonal production and cell differentiation, and migration (13). CD38 is expressed in hematopoietic cells (B- and T-lymphocytes) and hypothalamic neurons. The first reports on the ability of CD38 to regulate OT production through Ca2+-signaling and influence social interactions were published by Jin et al. in 2007 (14). Subsequent studies have shown that CD38 knockout mice have an outstanding reduction in OT production (15). The single nucleotide polymorphism rs3796863 (A > C) located in intron 7 of the CD38 gene, which is has been mapped in the 4p15 chromosomal region (16). It is assumed that the rs3796863 A allele variant is associated with high expression of CD38, increased plasma oxytocin concentration, and a pronounced level of social sensitivity (17).

The oxytocin receptor (OXTR) belongs to class I of the G-protein family, has seven transmembrane domains, and is encoded by the OXTR gene located in the 3p25–3p26.2 chromosomal region. The OXTR gene contains three introns and four exons; the role of the rs53576 (G > A) polymorphic variant, localized in the third exon, has been studied intensively regarding its association with human social functions (6). It is not entirely clear how the OXTR rs53576 variant is translated into phenotypic variations. It has been assumed that the rs53576 variant influences the methylation of the OXTR gene: the carriage of the G allele may be associated with a low level of methylation and subsequent high transcription of the gene, enhanced expression of the OT receptor, and an increased level of social sensitivity (18–21).

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was developed by Goodman et al. (22) as a brief psychopathological screening tool and is recommended to detect and classify psychosocial problems in adolescents. The SDQ is now very widely used in clinical practice and scientific research because of its brevity, reliability, and ability to assess various aspects of the psychosocial state in adolescents. The validity of the SDQ in clinical setting was confirmed by numerous studies (23–25). An undoubted advantage of the SDQ is also its wide availability: currently, it has been translated into more than 80 languages. It is also freely available on the developers' website (https://sdqinfo.org/), making cross-cultural comparisons possible. The Russian version of the SDQ has been thoroughly validated by Ruchkin et al. (26) and Slobodskaya et al. (27) on a sample group of Siberian schoolchildren (Novosibirsk, Russia).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no field studies on the effect of OT gene polymorphism on the psychosocial characteristics of adolescents in an unbiased school sample using the SDQ questionnaire. In this exploratory study, we adopted a genetic approach to analyze psychosocial characteristics in a sample of adolescents, focusing on two polymorphisms of the CD38 and the OXTR genes (respectively, rs3796863 and rs53576).

In the present study, psychological and genetic testing was carried out on 298 adolescents aged 12–18 from unbiased urban school samples. The ethnicity of all adolescents included in the study is Russian Caucasoid.

The research was carried out in public education schools after the end of the lessons. Each school was randomly assigned for testing. After receiving informed consent from parents, schoolchildren were notified of the voluntariness and confidentiality of the study. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire that included demographic data (gender, age, the mother's nationality) and one-sided self-rated SDQ for adolescents aged 11–17. In our sample, twelve adolescents (4%) were 18-years-olds and in the same grade as 17-year-olds; we assume that their psychological characteristics were very similar. Adolescents were asked to provide saliva samples in special containers after filling out the form.

The SDQ consists of 25 statements regarding problematic and socially approved behavior for assessment in adolescents over the prior 6 months. Answers are assessed on a 3-point scale [0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, and 2 = certainly true; points were assigned in forward or reverse order for each question following the instructions of the authors of the questionnaire (22)] and were grouped according to five scales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer problems, and prosocial behavior.

Following the instructions of the authors of the questionnaire (22), the scores for the statements were summed and grouped to calculate the indicator for each scale: emotional symptoms are characterized by statements No 3, 8, 13, 16, and 24; conduct problems are summed from the points of No 5, 7, 12, 18, and 22; hyperactivity/inattention are reflected by statements No 2, 10, 5, 21, and 25, while peer problems are determined from questions No 6, 11, 14, 19, and 23. The total number of points reflects the severity of problems in a particular area for a teenager. Additionally, the scores of the first four scales form another scale named “total difficulties score.” The prosocial behavior score is calculated separately based on the sum of points for statements No 1, 4, 9, 17, and 20. We used the Russian version of the questionnaire for our study, which can be freely downloaded from the developers' site (https://sdqinfo.org/).

Previously, with using factor analysis, some studies have shown that internalizing problems are defined as a combination of SDQ assessed emotional symptoms and peer problems, while externalizing problems are defined as a combination of conduct problems and hyperactivity-inattention (28–30). In our study, we also used this approach.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal Research Center “Krasnoyarsk Science Center of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.”

Saliva samples for genotyping were collected using “Saliva DNA Collection and Preservation Devices” (Norgen Biotek Corp., Thorold, ON Canada). Genomic DNA was extracted from the sample using “DIAtom DNA Prep kits” (IzoGen, Russia). Variants were determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RTime-PCR) using “Rotor-Gene 6000” (Corbett Life Science, Australia). Genotyping was carried out using TaqMan allele discrimination technology and commercially available TaqMan probes (DNA-Synthesis, Russia). The PCR reaction system, with a total volume of 25 μL, contained 1 μL of DNA template (about 10 ng), 10 μL of 2.5 × reaction mix for RTime-PCR, 2 μL of 25 mM MgCl2, 8.5 μL of ddH2O (M-428, Syntol, Russia), 2.5 μL of 10 μM primer mix, and 1 μL of each fluorescent probe (DNA-Synthesis, Russia). RTime-PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 3 min; 95°C for 20 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s (50 cycles). More details related to genotyping are shown in Supplementary Material.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica v.12.0 software (StatSoft Inc., USA). SDQ score data are shown as medians (25–75% quartiles). Differences in categorical data were assessed using the two-tailed Fisher's exact test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine whether there are differences in SDQ scores between groups according to genotypes.

Based on an estimated among Central-North Europoid populations AA+AC/CC genotypes prevalence for CD38 rs3796863 (47/53%), and AA+AG/GG for OXTR rs53576 (63/37%) according to data on http://www.ensembl.org/ and estimated proportion differences ≈ 20% (31), at least 280 participants were needed to have 0.80 power to detect a medium size effect (Cramer's V = 0.3) at α = 0.0083 (with a Bonferroni correction (0.05/6) to adjust for multiple hypothesis testing). Statistical power was tested with the public domain software G*Power 3.1.9.2 (32).

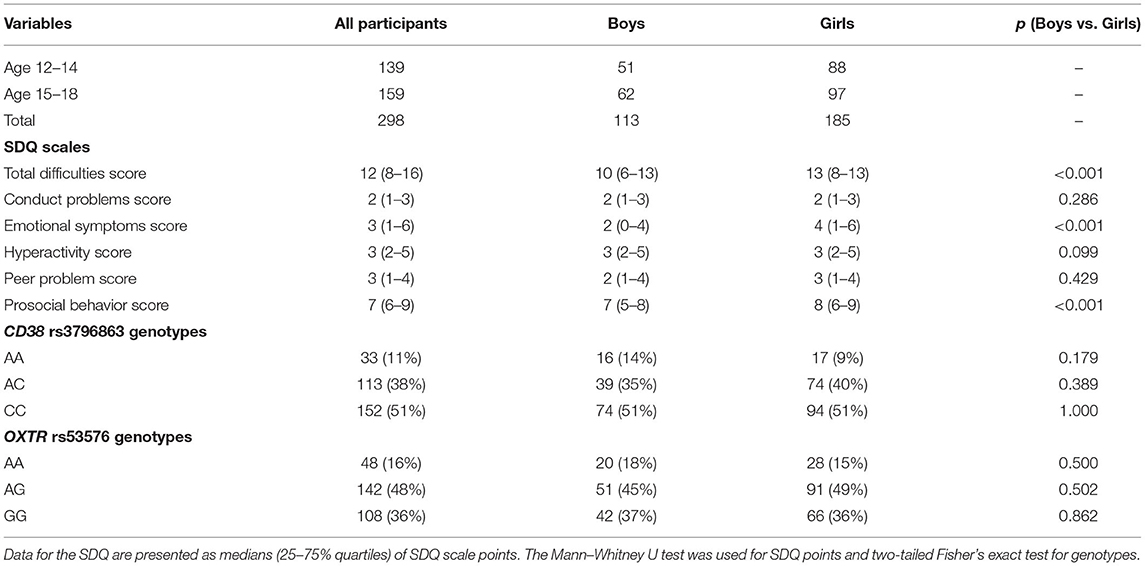

Descriptive statistics for the major study variables, SDQ scales, CD38 rs3796863, and OXTR rs53576 are presented in Table 1. Girls in our sample group showed higher scores in the SDQ scales of emotional symptoms and prosocial behavior compared to boys. Similar gender differences have been described for other populations (26, 33). The frequencies of the CD38 rs3796863 and OXTR rs53576 genotype distribution in the sample group are comparable to their frequencies in Caucasoid populations (according to data on http://www.ensembl.org/) and do not depend on the gender of participants. The allelic distributions for CD38 rs3796863 and OXTR rs53576 are in line with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (please see Supplementary Material).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for major study variables, SDQ scales, CD38 rs3796863, and OXTR rs53576.

As is the case for a large number of similar studies that evaluated genotypic differences for the rs3796863 variant (34–38), we used the dominant inheritance model to ensure a sufficient number of participants in each group to be analyzed, where the minor homozygotes and heterozygotes for CD38 rs3796863 (AA and AC) were combined and compared with the homozygotes for the major allele (CC). The same analysis strategy was used to assess the OXTR rs53576 genotypes: minor homozygotes and heterozygotes (AA and AG) were combined and compared with homozygotes for the major allele (GG), which was also used in several studies of Caucasoid populations, in which the G allele predominates (in contrast to Asian populations, in which the A allele is more common) (39–42).

Table 2 presents the CD38 rs3796863 and OXTR rs53576 genotypes distributions according to SDQ results. There was no evidence of genotype differences in the Prosocial behavior score and Internalizing problems. The carriage of high-OT-producing CD38 rs3796863 genotypes (AA + AC) exhibits only a weak tendency toward the lower level of Externalizing problems (p = 0.058) that substantially exceeded the Bonferroni adjustment of p < 0.0083.

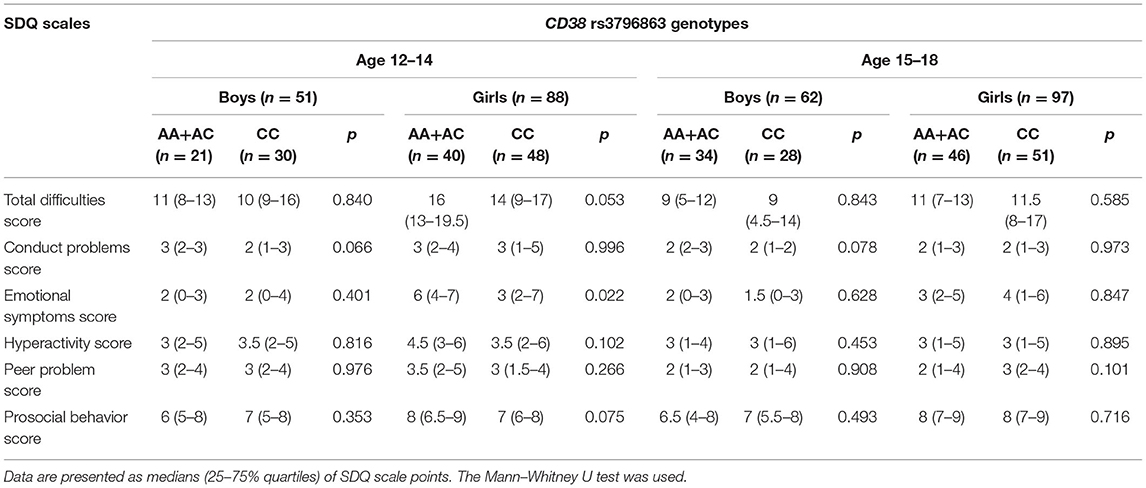

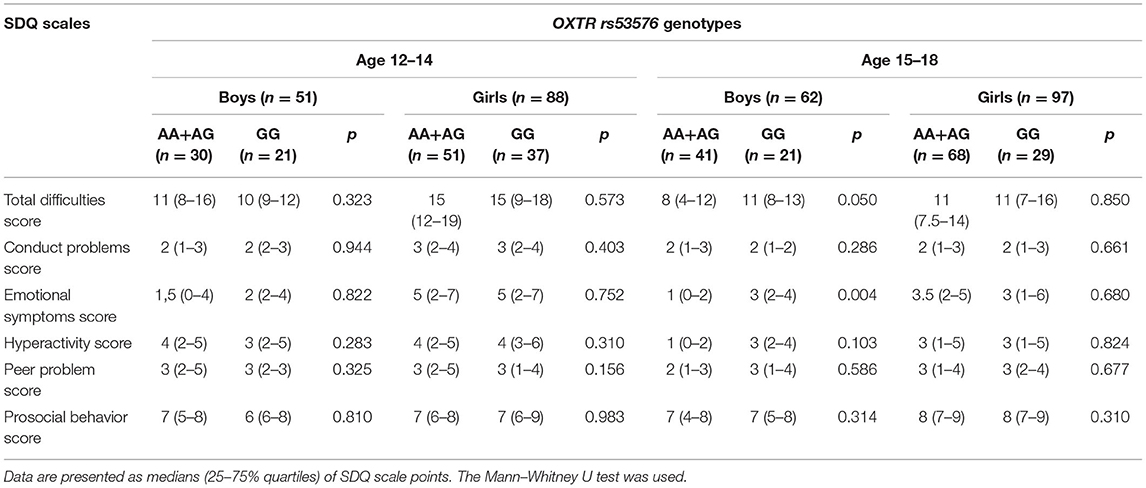

It is known that oxytocin production decreases in adolescents in comparison with pre-pubertal children, and there are sex differences in OT production: levels are higher in adolescent girls and women (43, 44). Moreover, the median values of individual SDQ scales for boys significantly differ from that of the girls in our sample group (Table 1). To take into consideration such age and gender differences, we carried out the post-hoc discrete analysis of the CD38 rs3796863 and OXTR rs53576 genotype influences on the indicators of the SDQ questionnaire scales in two age groups (12–14 and 15–18 years old) separately for boys and girls. The median values of SDQ scales according to the different CD38 rs3796863 and OXTR rs53576 genotypes are, respectively, presented in Tables 3, 4.

Table 3. Values of the SDQ scales for the CD38 rs3796863 genotypes in different sex and age groups of adolescents.

Table 4. Values of the SDQ scales for the OXTR rs53576 genotypes in different sex and age groups of adolescents.

The tendency toward an association between CD38 rs3796863 genotypes and SDQ scores was found in girls aged 12–14 years (Table 3). In this group of adolescents, carriage of the high-OT-producing genotypes (AA + AC) was associated with high values of the Emotional symptoms score (p = 0.022, Bonferroni adjusted p = 0.176). SDQ score analysis based on OXTR rs53576 genotypes showed a statistically significant association only in the subgroup of older (15–18 years old) adolescent boys (Table 4). Homozygosity for the G allele, which is presumably associated with high activity of the oxytocin receptor, was associated with the presence of emotional problems (p = 0.004, Bonferroni adjusted p = 0.032).

Variationsat the CD38 rs3796863 and OXTR rs53576 loci were not associated with psychosocial characteristics of adolescents assessed with SDQ in our complete sample. Our results are similar to the recent findings from Conner et al. study that found no correlation between OXTR rs53576 genetic polymorphism and emotional traits, including depressive symptoms, psychological well-being, optimism, and self-esteem in young adults (45). Another study of 10,760 participants from 2017 found no role of the variants within the OXTR gene in loneliness, a trait correlated with neuroticism and depressive symptoms; however, this study found that these traits do show heritability, but they are highly polygenic (46). McInnis et al. investigated the same polymorphism for the CD38 and OXTR genes (rs3796863 and rs53576) found no relation of OXTR and unsupportive social interactions and affective states in undergraduate students (n = 476), but A carriers of the CD38 polymorphism exhibited greater perceived peer unsupportive interactions compared to CC carriers (37). Conversely, Huetter et al. established a lack of association of the CD38 rs3796863 polymorphisms and a significant association of the OXTR rs53576 variants linked to empathic behavior in 421 healthy adults (47). No link the CD38 rs3796863 variants with emotion perception in 120 patients with anorexia nervosa were found (31). Lastly, in the Young Finns Study, Dobewall et al. did not find an effect of oxytocin pathway genes (including CD38 rs3796863) on the initial levels of dispositional compassion for others (48).

In contrast, as mentioned above, many studies have shown significant association of the CD38 rs3796863 and OXTR rs53576 genes polymorphisms with psychosocial and emotional status in adolescents and young adults (6–8, 18–21). Given the conflicting research results, we suppose that replication studies are highly needed with considering gene-environment interaction models, age, and gender characteristics.

The post-hoc results of our study show the possible presence of age–sex features of the influence of OT production (CD38) and OT reception (OXTR) genes on the psychosocial characteristics of adolescents. This is not surprising, as there are two parallel processes in adolescence: the age-dependent decrease in OT production and the emergence of sex differences in its production (43). In addition to these, such differentiation can be influenced by a complex and insufficiently studied interaction between OT and the entire spectrum of sex hormones, exhibiting highly dynamic changes in adolescence (49).

We presume that a relatively large production of OT, mediated by the carriage of the A allele of the rs3796863 variant region of the CD38 gene, may be associated with disturbances in the emotional sphere in young adolescent girls due to a higher level of social sensitivity, which corresponds with the results of other studies. The hypothesis of CD38-mediated social sensitivity as a general mechanism of oxytocin moderation of an increased psycho-emotional response to positive and negative social stimuli was originally put forward by Bartz and McInnes (50, 51). This hypothesis was later confirmed. For example, in the examination of 400 adolescents, Tabak et al. showed that carriers of the A allele rs3796863 of the CD38 gene were more sensitive to chronic interpersonal stress than CC homozygotes (35). Mediated by genetic variations in CD38, high levels of social sensitivity as a factor of emotional problems were demonstrated in a study by McQuaid et al. (52). The authors conducted genetic testing of 19-year-old students and found that AA homozygotes of rs3796863 experienced heightened feelings of alienation from parents and peers, symptoms of depression, and an increased level of suicidal ideation. Later, the same authors showed that carriers of the A allele of rs3796863 were more sensitive to unsupportive social interactions with their peers (relationships that bring pain, suffering, sadness, isolation, rejection, and troubles) (37). Lebowitz et al. found that the influence of negative relationships with peers more often led to suicidal ideations in adolescents with high OT levels in saliva, which also supports the hypothesis of OT-mediated excessive social sensitivity (53).

According to our post-hoc data, the mechanisms of OT reception, mediated by the carriage of the G allele of the OXTR rs53576 gene, may be more vital for older adolescent boys in the regulation of emotions and behavior, as this age–sex group experiences the conditions of relatively low OT production in comparison with girls and younger boys. The provocative role of G-allele carriage in the formation of psycho-emotional problems in adolescents has been described in several studies. For example, Smearman et al. revealed a greater level of behavioral problems under the influence of stress factors in adolescents with the G allele of rs53576 (54). McQuaid et al. described the association of G allele of rs53576 carriage with depressive symptoms in students who underwent a traumatic situation in childhood (55). The authors considered these results to be paradoxical since a large number of studies have simultaneously shown the association of the G allele of rs53576 with extremely socially useful qualities, such as empathy, optimism, and trust (19, 21, 39, 56, 57). As a possible explanation for their findings, the authors proposed the hypothesis of excessive social sensitivity in individuals with high production and reception of OT, which is described above. Similar results were later obtained by Hostinar et al.: in adolescents who experienced childhood maltreatment, a high level of anxiety and depression symptoms were more often found in those with homozygosity for GG of rs53576 (58).

Some studies confirm the existence of sex differences in the regulation of OT reception in adolescent populations. Thus, Andreou et al. conducted genetic testing of 1,591 Swedish adolescents and revealed an association between the G allele of the rs53576 region of the OXTR gene and antisocial behavior in maltreatment cases, but this was still only applicable to girls, not boys (9). The authors concluded that it is mandatory to consider the gender factor in studies on the role of the oxytocinergic system in adolescents. In a prospective study of 593 15-year-old Estonian adolescents, it was shown that in boys (but not girls), homozygosity for the allelic variant A of rs53576 was associated with more frequent alcohol consumption and the development of addiction to alcohol by the age of 25 (59). It was found that in a Chinese population of adolescents homozygous for the major allele in Asian populations, which is the A rs53576 OXTR allele, there is a greater level of hostility and aggressiveness when the individual is exposed to stress factors (7). The effect was much more typical for boys than for girls, which is consistent with our data.

It is known that oxytocin receptors are concentrated mainly in the amygdala, and the size of the amygdala in men is larger than that in women, on average. It is negatively correlated with prosocial behavior. In this regard, the data of Tost et al. found that the right amygdala was smaller in homozygous carriers of the G allele of the OXTR rs53576 gene (typical only for men, not women), are extremely interesting (60). There are well-known data on sex differences in psychological reactions to the administration of exogenous OT, which were obtained both in experiments with animals and in controlled studies in humans (49, 61). Lucas-Thompson et al. investigated the psychological response to the September 11 terrorist attack and found that the OXTR rs53576 polymorphism moderated the stress response only in men, but not in women, and homozygosity for GG of rs53576 was associated with poorer stress tolerance (41). In men, but not in women, GG homozygosity of rs53576 was associated with an increased sympathetic response of the cardiorespiratory system to stress compared to carriers of the A allele (62). Finally, Nishina et al. found a higher confidence level in carriers of the GG genotype of rs53576 variant in Japanese men but not women (42). The results of the studies mentioned above correspond well enough with our data on the greater effect of the OXTR rs53576 gene variant on the psychosocial characteristics of boys, but not girls, and this phenomenon manifested only in older adolescents in the process of growing up. It may be assumed that the differences in the structure and function of the amygdala are fully formed only after reaching older adolescence.

Some limitations characterize the present study. Over the past few years, genome-wide association studies with hundreds of thousands of participants have shown that individual candidate genes do not explain sufficient variance in complex human psychological and behavioral traits. For example, a study from 2019 with very large samples ranging from 62,138 to 443,264 participants showed no main effect or G x E interactions of single candidate genes on depressive symptoms, which are closely related to psychosocial problems, the construct in the current study (63). Thus, findings like in our post-hoc analysis are likely to be false positives due to small subgroups size. For reducing the chance of reporting false-positive/negative associations for our main group, we conducted our study in an unbiased school sample and previously calculated the required sample size. In many other similar studies with the null findings for rs3796863 and rs53576, the number of participants varies from 120 to 480 (31, 37, 45, 48, 64, 65). In the present study, we enrolled 298 adolescents, which were sufficient for statistical power 0.8 for our main group and according to our design. The SDQ allows assessing the psychosocial state of adolescents exclusively over the prior 6 months and does not reflect life-time problems; it might not be suitable for genetic studies. With regards to this issue is more reasonable to conduct a longitudinal study (48) which also significantly increases the statistical power.

In studies with a similar design, we extremely recommend replication in larger samples with greater power to detect small effects, especially in subgroups. We also suppose that the psychophysiological role of OT should be assessed in the context of a social environment, ethnocultural factors, age, and gender characteristics (e.g., stratification by age and sex should be mandatory in this type of study among adolescents).

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal Research Center Krasnoyarsk Science Center of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

ST, EK, and NS: conceptualization. SZ, MSm, LE, OZ, MSh, NG, and LL: investigation. MSh: data curation. ST and SZ: writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing. ST: project administration and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This study was carried out under the state assignment (theme # 003) for Scientific Research Institute of Medical Problems of the North, Krasnoyarsk, Russia.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.714093/full#supplementary-material

OT, Oxytocin; CD38, Cluster of differentiation 38; OXTR, Oxytocin receptor; SDQ, The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; DNA, Deoxyribonucleic acid; RT-PCR, Real-time polymerase chain reaction; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

1. Torres N, Martins D, Santos AJ, Prata D, Verissimo M. How do hypothalamic nonapeptides shape youth's sociality? A systematic review on oxytocin, vasopressin and human socio-emotional development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2018) 90:309–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.05.004

2. Kavaliers M, Matta R, Choleris E. Mate-choice copying, social information processing, and the roles of oxytocin. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2017) 72:232–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.003

3. Plessow F, Eddy KT, Lawson EA. The neuropeptide hormone oxytocin in eating disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2018) 20:91. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0957-0

4. Xu S, Qin B, Shi A, Zhao J, Guo X, Dong L. Oxytocin inhibited stress induced visceral hypersensitivity, enteric glial cells activation, and release of proinflammatory cytokines in maternal separated rats. Eur J Pharmacol. (2018) 818:578–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.11.018

5. Rash JA, Aguirre-Camacho A, Campbell TS. Oxytocin and pain: a systematic review and synthesis of findings. Clin J Pain. (2014) 30:453–62. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31829f57df

6. Feldman R, Monakhov M, Pratt M, Ebstein RP. Oxytocin pathway genes: evolutionary ancient system impacting on human affiliation, sociality, and psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry. (2016) 79:174–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.008

7. Shao D, Zhang HH, Long ZT, Li J, Bai HY, Li JJ, et al. Effect of the interaction between oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism (rs53576) and stressful life events on aggression in Chinese Han adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2018) 96:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.06.002

8. Parris MS, Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Andronikashvili A, Burke AK, Yin H, et al. Attempted suicide and oxytocin-related gene polymorphisms. J Affect Disord. (2018) 238:62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.022

9. Andreou D, Comasco E, Aslund C, Nilsson KW, Hodgins S. Maltreatment, the oxytocin receptor gene, and conduct problems among male and female teenagers. Front Hum Neurosci. (2018) 12:112. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00112

10. Tereshchenko SY, Smolnikova M. Oxitocin is a hormone of trust and emotional attachment: the influence on behavior of children and adolescents. Zhurnal nevrologii i psikhiatrii imeni SS Korsakova. (2019) 119:148–53. doi: 10.17116/jnevro2019119121148

11. Ayaz AB, Karkucak M, Ayaz M, Gokce S, Kayan E, Guler EE, et al. Oxytocin system social function impacts in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. (2015) 168:609–16. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32343

12. Cataldo I, Azhari A, Lepri B, Esposito G. Oxytocin receptors (OXTR) and early parental care: an interaction that modulates psychiatric disorders. Res Dev Disabil. (2018) 82:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.10.007

13. Higashida H, Hashii M, Tanaka Y, Matsukawa S, Higuchi Y, Gabata R, et al. CD38, CD157, and RAGE as molecular determinants for social behavior. Cells. (2019) 9:62. doi: 10.3390/cells9010062

14. Jin D, Liu H.-X., Hirai H, Torashima T, Nagai T, et al. CD38 is critical for social behaviour by regulating oxytocin secretion. Nature. (2007) 446:41–45. doi: 10.1038/nature05526

15. Liu H.-X., Lopatina O, Higashida C, Tsuji T, Kato I, et al. Locomotor activity, ultrasonic vocalization and oxytocin levels in infant CD38 knockout mice. Neurosci Lett. (2008) 448:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.084

16. Malavasi F, Deaglio S, Funaro A, Ferrero E, Horenstein AL, Ortolan E, et al. Evolution and function of the ADP ribosyl cyclase/CD38 gene family in physiology and pathology. Physiol Rev. (2008) 88:841–86. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2007

17. Feldman R, Zagoory-Sharon O, Weisman O, Schneiderman I, Gordon I, Maoz R, et al. Sensitive parenting is associated with plasma oxytocin and polymorphisms in the OXTR and CD38 genes. Biol Psychiatry. (2012) 72:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.025

18. Bell AF, Carter CS, Steer CD, Golding J, Davis JM, Steffen AD, et al. Interaction between oxytocin receptor DNA methylation and genotype is associated with risk of postpartum depression in women without depression in pregnancy. Front Genet. (2015) 6:243. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00243

19. Li J, Zhao Y, Li R, Broster LS, Zhou C, Yang S. Association of oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) rs53576 polymorphism with sociality: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0131820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131820

20. Reiner I, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Bleich S, Beutel M, Frieling H. Methylation of the oxytocin receptor gene in clinically depressed patients compared to controls: the role of OXTR rs53576 genotype. J Psychiatr Res. (2015) 65:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.03.012

21. Gong P, Fan H, Liu J, Yang X, Zhang K, Zhou X. Revisiting the impact of OXTR rs53576 on empathy: a population-based study and a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2017) 80:131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.03.005

22. Goodman R, Meltzer H, Bailey V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1998) 7:125–30. doi: 10.1007/s007870050057

23. Silva TB, Osório FL, Loureiro SR. SDQ: discriminative validity and diagnostic potential. Front Psychol. (2015) 6:811. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00811

24. Hall CL, Guo B, Valentine AZ, Groom MJ, Daley D, Sayal K, et al. The validity of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) for children with ADHD symptoms. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0218518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218518

25. Vugteveen J, de Bildt A, Theunissen M, Reijneveld M, Timmerman M. Validity aspects of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) adolescent self-report and parent-report versions among Dutch adolescents. Assessment. (2021) 28:601–16. doi: 10.1177/1073191119858416

26. Ruchkin V, Koposov R, Schwab-Stone M. The strength and difficulties questionnaire: scale validation with Russian adolescents. J Clin Psychol. (2007) 63:861–9. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20401

27. Slobodskaya HR, Akhmetova OA, Ryabichenko TI. Siberian child and adolescent mental health: prevalence estimates and psychosocial factors. Alaska Med. (2007) 49:261–6.

28. Koskelainen M, Sourander A, Vauras M. Self-reported strengths and difficulties in a community sample of Finnish adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2001) 10:180–5. doi: 10.1007/s007870170024

29. Dickey WC, Blumberg SJ. Revisiting the factor structure of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire: United States, 2001. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2004) 43:1159–67. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000132808.36708.a9

30. Choi D, Tsuchiya KJ, Takei N. Interaction effect of oxytocin receptor (OXTR) rs53576 genotype and maternal postpartum depression on child behavioural problems. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:7685. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44175-6

31. Kucharska K, Kot E, Biernacka K, Zimowski J, Rogoza R, Rybakowski F, et al. Interaction between polymorphisms of the oxytocinergic system genes and emotion perception in inpatients with anorexia nervosa. Eur Eating Disord Rev. (2019) 27:481–94. doi: 10.1002/erv.2698

32. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. (2009) 41:1149–60. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

33. Kaiser S, Kyrrestad H, Fossum S. Cyberbullying status and mental health in Norwegian adolescents. Scand J Psychol. (2020) 61:707–13. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12656

34. Sauer C, Montag C, Reuter M, Kirsch P. Imaging oxytocin × dopamine interactions: an epistasis effect of CD38 and COMT gene variants influences the impact of oxytocin on amygdala activation to social stimuli. Front Neurosci. (2013) 7:45. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00045

35. Tabak BA, Vrshek-Schallhorn S, Zinbarg RE, Prenoveau JM, Mineka S, Redei EE, et al. Interaction of CD38 variant and chronic interpersonal stress prospectively predicts social anxiety and depression symptoms over 6 years. Clin Psychol Sci. (2016) 4:17–27. doi: 10.1177/2167702615577470

36. Liu J, Gong P, Li H, Zhou X. A field study of the association between CD38 gene and altruistic behavior: empathic response as a mediator. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2017) 85:165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.08.010

37. McInnis OA, McQuaid RJ, Matheson K, Anisman H. Unsupportive social interactions and affective states: examining associations of two oxytocin-related polymorphisms. Stress. (2017) 20:122–9. doi: 10.1080/10253890.2017.1286326

38. Tabak BA, Young KS, Torre JB, Way BM, Burklund LJ, Eisenberger NI, et al. Preliminary evidence that CD38 moderates the association of neuroticism on amygdala-subgenual cingulate connectivity. Front Neurosci. (2020) 14:11. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00011

39. Rodrigues SM, Saslow LR, Garcia N, John OP, Keltner D. Oxytocin receptor genetic variation relates to empathy and stress reactivity in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2009) 106:21437–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909579106

40. Tops M, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Riem MME, Boksem MAS, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Oxytocin receptor gene associated with the efficiency of social auditory processing. Front Psychiatry. (2011) 2:60. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00060

41. Lucas-Thompson RG, Holman EA. Environmental stress, oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) polymorphism, and mental health following collective stress. Horm Behav. (2013) 63:615–24. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.02.015

42. Nishina K, Takagishi H, Inoue-Murayama M, Takahashi H, Yamagishi T. Polymorphism of the oxytocin receptor gene modulates behavioral and attitudinal trust among men but not women. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0137089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137089

43. Doom JR, Doyle CM, Gunnar MR. Social stress buffering by friends in childhood and adolescence: effects on HPA and oxytocin activity. Soc Neurosci. (2017) 12:8–21. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2016.1149095

44. Marazziti D, Baroni S, Mucci F, Piccinni A, Moroni I, Giannaccini G, et al. Sex-related differences in plasma oxytocin levels in humans. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. (2019) 15:58–63. doi: 10.2174/1745017901915010058

45. Conner TS, McFarlane KG, Choukri M, Riordan BC, Flett JAM, Phipps-Green AJ, et al. The oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) variant rs53576 Is not related to emotional traits or states in young adults. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:2548. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02548

46. Gao J, Davis LK, Hart AB, Sanchez-Roige S, Han L, Cacioppo JT, et al. Genome-wide association study of loneliness demonstrates a role for common variation. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2017) 42:811–21. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.197

47. Huetter FK, Bachmann HS, Reinders A, Siffert D, Stelmach P, Knop D, et al. Association of a common oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism with self-reported ‘empathic concern' in a large population of healthy volunteers. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0160059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160059

48. Dobewall H, Saarinen A, Lyytikäinen L.-P., Keltikangas-Järvinen L, Lehtimäki T, et al. Functional polymorphisms in oxytocin and dopamine pathway genes and the development of dispositional compassion over time: the young finns study. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:576346. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.576346

49. Macdonald KS. Sex, receptors, and attachment: a review of individual factors influencing response to oxytocin. Front Neurosci. (2013) 6:194. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00194

50. Bartz JA, McInnes LA. CD38 regulates oxytocin secretion and complex social behavior. BioEssays. (2007) 29:837–41. doi: 10.1002/bies.20623

51. Bartz JA, Zaki J, Bolger N, Ochsner KN. Social effects of oxytocin in humans: context and person matter. Trends Cogn Sci. (2011) 15:301–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.002

52. McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Matheson K, Anisman H. Oxytocin and social sensitivity: gene polymorphisms in relation to depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. Front Hum Neurosci. (2016) 10:358. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00358

53. Lebowitz ER, Blumberg HP, Silverman WK. Negative peer social interactions and oxytocin levels linked to suicidal ideation in anxious youth. J Affect Disord. (2019) 245:806–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.070

54. Smearman EL, Winiarski DA, Brennan PA, Najman J, Johnson KC. Social stress and the oxytocin receptor gene interact to predict antisocial behavior in an at-risk cohort. Dev Psychopathol. (2015) 27:309–18. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000649

55. McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Stead JD, Matheson K, Anisman H. A paradoxical association of an oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism: early-life adversity and vulnerability to depression. Front Neurosci. (2013) 7:128. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00128

56. Saphire-Bernstein S, Way BM, Kim HS, Sherman DK, Taylor SE. Oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is related to psychological resources. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2011) 108:15118–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113137108

57. Krueger F, Parasuraman R, Iyengar V, Thornburg M, Weel J, Lin M, et al. Oxytocin receptor genetic variation promotes human trust behavior. Front Hum Neurosci. (2012) 6:4. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00004

58. Hostinar CE, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism, perceived social support, and psychological symptoms in maltreated adolescents. Dev Psychopathol. (2014) 26:465–77. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000066

59. Vaht M, Kurrikoff T, Laas K, Veidebaum T, Harro J. Oxytocin receptor gene variation rs53576 and alcohol abuse in a longitudinal population representative study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2016) 74:333–41. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.09.018

60. Tost H, Kolachana B, Hakimi S, Lemaitre H, Verchinski BA, Mattay VS, et al. A common allele in the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) impacts prosocial temperament and human hypothalamic-limbic structure and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2010) 107:13936–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003296107

61. Van Anders SM, Goldey KL, Kuo PX. The steroid/peptide theory of social bonds: integrating testosterone and peptide responses for classifying social behavioral contexts. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2011) 36:1265–75. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.06.001

62. Norman GJ, Hawkley L, Luhmann M, Ball AB, Cole SW, Berntson GG, et al. Variation in the oxytocin receptor gene influences neurocardiac reactivity to social stress and HPA function: a population based study. Horm Behav. (2012) 61:134–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.11.006

63. Border R, Johnson EC, Evans LM, Smolen A, Berley N, Sullivan PF, et al. No support for historical candidate gene or candidate gene-by-interaction hypotheses for major depression across multiple large samples. Am J Psychiatry. (2019) 176:376–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18070881

64. Davis C, Patte K, Zai C, Kennedy JL. Polymorphisms of the oxytocin receptor gene and overeating: the intermediary role of endophenotypic risk factors. Nutr Diabetes. (2017) 7:e279. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2017.24

Keywords: oxytocin, CD38, OXTR, rs3796863, rs53576, gene polymorphism, adolescents, psychosocial characteristics

Citation: Tereshchenko S, Kasparov E, Zobova S, Smolnikova M, Evert L, Semenova N, Zaitseva O, Shubina M, Gorbacheva N and Lapteva L (2021) Oxytocin Pathway Gene (CD38, OXTR) Variants Are Not Related to Psychosocial Characteristics Defined by Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in Adolescents: A Field School-Based Study. Front. Psychiatry 12:714093. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.714093

Received: 25 May 2021; Accepted: 15 July 2021;

Published: 09 August 2021.

Edited by:

Yong-Kyu Kim, Northwestern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Dorota Frydecka, Wroclaw Medical University, PolandCopyright © 2021 Tereshchenko, Kasparov, Zobova, Smolnikova, Evert, Semenova, Zaitseva, Shubina, Gorbacheva and Lapteva. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sergey Tereshchenko, bGVnaXNlQG1haWwucnU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.