- Child Health and Parenting (CHAP), Department of Public Health and Caring Science, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic is primarily a crisis that affects people's physical health. However, it is well-known from previous epidemics and pandemics that there are other indirect negative impacts on mental health, among others. The purpose of this scoping review was to explore and summarise primary empirical research evidence on how the COVID-19 pandemic and societal infection control measures have impacted children and adolescents' mental health.

Methods: A literature search was conducted in five scientific databases: PubMed, APA PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINHAL, and Social Science Premium Collection. The search string was designed using the Population (0–18 years), Exposure (COVID-19), Outcomes (mental health) framework. Mental health was defined broadly, covering mental well-being to mental disorders and psychiatric conditions.

Results: Fifty-nine studies were included in the scoping review. Of these, 44 were cross-sectional and 15 were longitudinal studies. Most studies reported negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health outcomes, yet the evidence was mixed. This was also the case for studies investigating societal control measures. Strong resilience, positive emotion regulation, physical activity, parental self-efficacy, family functioning and emotional regulation, and social support were reported as protective factors. On the contrary, emotional reactivity and experiential avoidance, exposure to excessive information, COVID-19 school concerns, presence of COVID-19 cases in the community, parental mental health problems, and high internet, social media and video game use were all identified as potentially harmful factors.

Conclusions: Due to the methodological heterogeneity of the studies and geographical variation, it is challenging to draw definitive conclusions about the real impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents. However, the existing body of research gives some insight to how parents, clinicians and policy makers can take action to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 and control measures. Interventions to promote physical activity and reduce screen time among children and adolescents are recommended, as well as parenting support programs.

Introduction

The outbreak of a new respiratory syndrome, declared as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 (1) and continued to spread rapidly around the world. On March 11th 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic that had spread to 114 countries. COVID-19 showed a high transmission ability compared with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome); however, on the other hand, COVID-19 showed a lower mortality rate (4.5–6.0%) when compared to SARS (9.6%), and MERS (34.4%) (1).

It is believed the virus that causes COVID-19 spreads mainly from person to person. As an attempt to slow down the spread of the virus, in mid-March 2020, many countries took preventive measures such as social distancing and quarantine. By September–October 2020, after a relaxation of lockdowns and the population's precautionary behaviours, indicators of a second wave were emerging in many European countries. From December 2020, international vaccination roll-out programmes commenced. Now more recently, in February–March 2021, there are concerns regarding a third wave. Restrictions are coming back but, in some countries, not as strict as in the first wave. By end of March 2021, more than 2.8 million people in the world had died from the virus and nearly 130 million had reported infection.

The COVID-19 pandemic is primarily a crisis that affects people's physical health, but it is well-known from previous epidemics and pandemics that the event, including societal measures to control infection, also affects the mental health of the population directly and indirectly (2), among a number of other potential negative outcomes. The societal infection control measures have proved to be successful controlling the spread of the virus (3); however, at the same time, the interruption of the daily routine of children, adolescents and their families has impacted their lives (4).

COVID-19 is an unprecedented global crisis compared to the most recent epidemics and children and adolescents are experiencing a prolonged state of physical isolation from their peers, teachers, extended families, and community networks (5). Added to children and adolescents' fear of personal and family member infection, there are other pandemic-related factors that could affect mental health outcomes such as family job or financial loss and social isolation due to infection containment measures (5).

It is crucial to understand and investigate the real impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and related societal measures to develop, adapt, and implement mitigation strategies for these outcomes in order to help children and adolescents' mental health and well-being during these stressful times as well as for future similar pandemics.

The aim of this scoping review was to explore and summarise primary research evidence on how the COVID-19 pandemic and societal infection control measures (such as “lockdown,” quarantine, social isolation, social distancing, and school closures) aimed at minimising the spread of the disease have impacted children and adolescents' mental health, from birth up to 18 years.

Methods

The scoping review followed the methodological framework as described by Arksey and O'Malley (6). The framework sets out five steps: (i) identifying the research question(s); (ii) identifying relevant studies; (iii) study selection; (iv) charting the data; and (v) collating, summarising and reporting the results. Yet, Arksey and O'Malley state that researchers should engage with each stage in a reflexive way (6). In other words, the process should not be considered linear but iterative. This means steps can be revisited, if needed.

Identifying the Research Questions

In order to thematically construct the account of existing literature, specific research questions were developed through discussion among the authors:

1. Has the COVID-19 pandemic and societal infection control measures impacted child and adolescent mental health?

2. What is the evidence from different geographical regions?

3. Are there any protective factors associated with a lower likelihood of mental health problem outcomes?

4. Are there any factors associated with a higher likelihood of mental health problem outcomes?

Identifying Relevant Studies

The literature search was conducted in five scientific databases: PubMed, APA PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINHAL, and Social Science Premium Collection by the University librarian. The search was performed on 4th December 2020. The search string was designed using the Population, Exposure, Outcomes (PEO) framework and adapted for each database by the University librarian (Appendix 1). Study identification was conducted in an iterative way (6), with a second search performed on 5th May 2021 using the same search string and databases as in the first search. The aim was to update the scoping review. As a prioritisation strategy, the second search focused only on longitudinal studies.

Study Selection

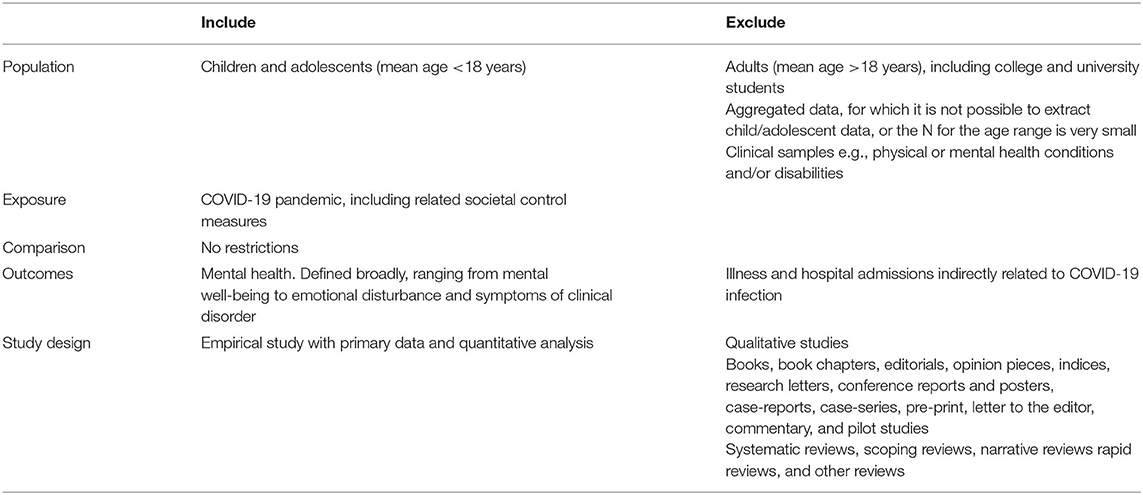

Only studies written in English were included. Further eligibility criteria were developed based on the aims of the review, which are summarised in Table 1. Reference management software was used to import and collate studies from the different databases. All non-duplicate references were screened in a staged process: if the inclusion/exclusion criteria were unclear from the title, the abstract was reviewed. Similarly, if the abstract did not provide sufficient detail then the full text was reviewed.

Charting the Data

Data from the selected studies were extracted into a data charting form using the database programme Excel. This included: author(s); year of publication; study location; aims; methodology; outcome measures; and important results.

Collating, Summarising, and Reporting the Results

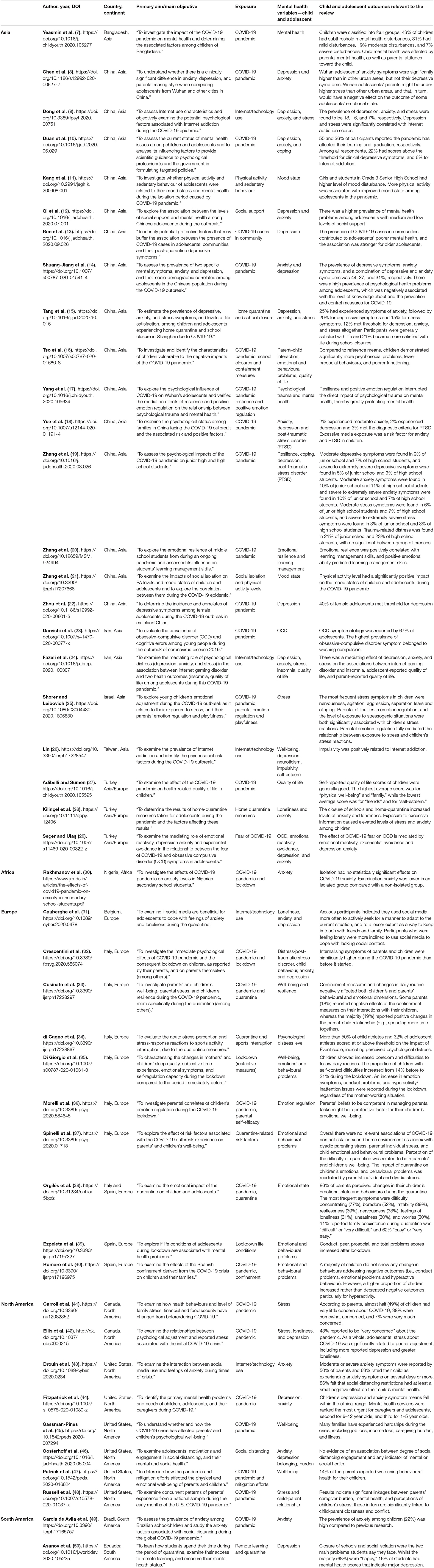

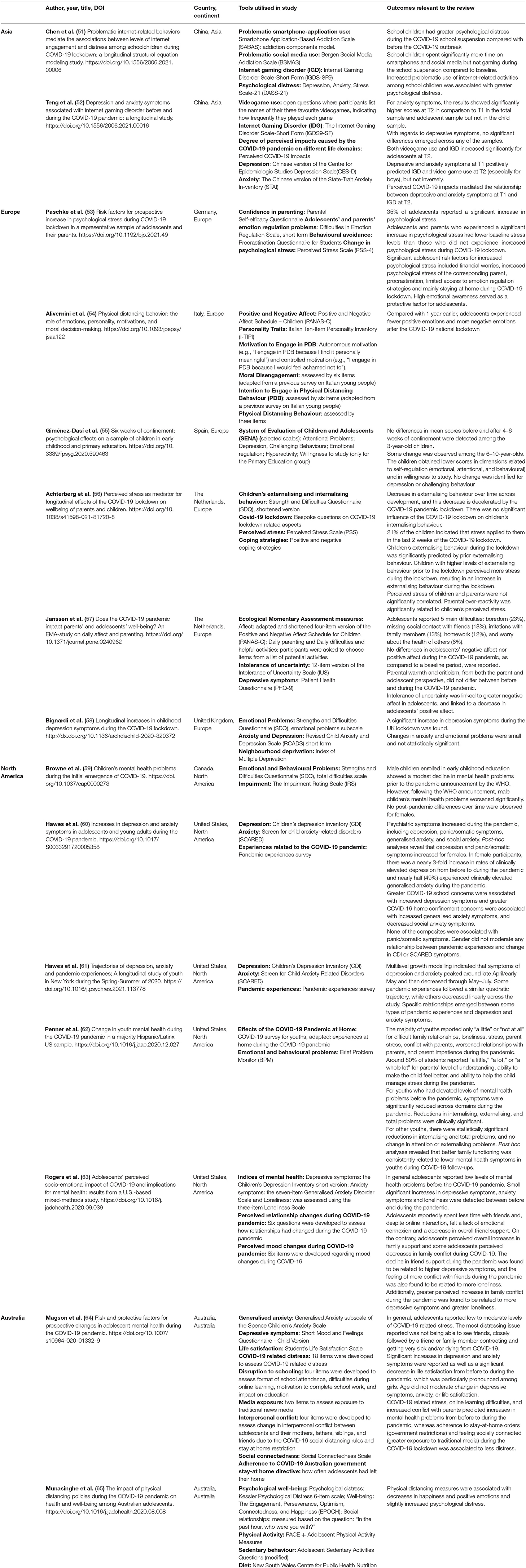

As scoping reviews seek to present an overview of all material reviewed (6), tables were constructed of all cross-sectional studies (Table 2) and all longitudinal studies (Table 3) included in the review. The reason for highlighting the methodological difference between studies was 2-fold. First, it is a logical and informative way to organise the studies when reporting the overall field of research. Second, it was used as a prioritisation strategy for the review update, as longitudinal studies are more likely to indicate causality, which is important when issuing recommendations based on the data. Within each table, the studies were organised by continent and country.

Results

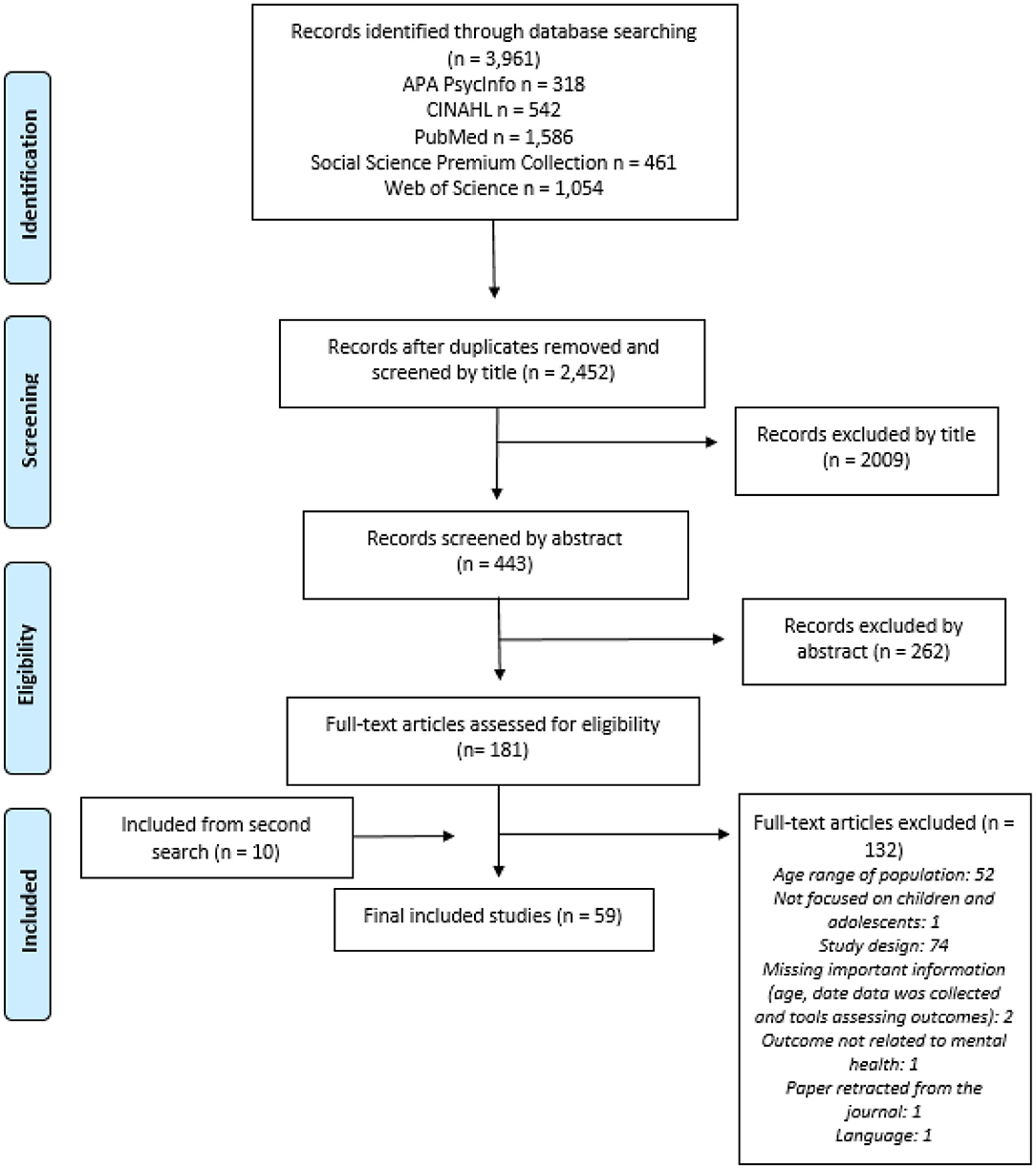

The first search yielded 2,452 non-duplicate references and resulted in 49 eligible studies (longitudinal and cross sectional) while the second search, used to update the review, yielded 3,309 non-duplicate references and resulted in 10 eligible studies (longitudinal only) (Figure 1). Some included studies had multiple aims, not all of which were related to a mental health outcome; only findings related to mental health outcomes were reported in this review.

Has the COVID-19 Pandemic and Societal Infection Control Measures Impacted Child and Adolescent Mental Health?

The review identified many cross-sectional studies investigating mental health symptomatology among children and adolescents during the pandemic period (Table 2). When compared with average scores prior to the pandemic, significantly increased levels of psychosocial problems were reported across international studies (16, 32, 35, 39, 49). There were also accounts of adolescents (42) and parents (38) directly reflecting on the impact of COVID-19 on mental health, which indicate concern. One study in China made a geographical comparison, demonstrating significantly higher levels of anxiety symptomatology among adolescents in the COVID-19 outbreak region of Wuhan compared with other urban areas (8). Reports were most common on symptoms of anxiety (8–10, 12, 14, 15, 18, 24, 28–32, 43, 44, 46, 49) and depression (8–10, 12–15, 18, 19, 22, 24, 26, 29, 31, 32, 42, 44, 46, 50), but other mental health disorders such as obsessive compulsive disorder (23, 29) and post-traumatic stress disorder (17–19, 25, 32) have been investigated as well as stress (9, 15, 24, 25, 34, 41, 42, 48), loneliness (28, 31, 42), and well-being (26, 33, 35, 45, 47) among other outcomes (Table 2). Although most of these studies indicate raised levels of mental health concerns among children and adolescents during the pandemic period, the evidence is mixed with some reporting no behavioural changes (40), good levels of well-being (27, 50) or even suggestion of improvement (15).

Yet, cross-sectional studies are descriptive in nature and it is not possible to infer causality from this research design. The scoping review discovered 15 longitudinal studies (Table 3), which involved repeated measures over time and provide stronger evidence to address the question of impact on mental health. Five longitudinal studies involved children (51, 55, 56, 58, 59), nine involved adolescents (53, 54, 57, 60–65) and one involved children and adolescents (52). Most of the studies indicated negative impact of the pandemic on mental health, including increased symptoms of depression (60, 63, 64, 66), anxiety (60, 63, 64, 67), loneliness (63), psychological distress (51, 53, 65), hyperactivity and impulsivity (55), and emotional and behavioural problems (59), as well as reductions in emotional regulation (55), happiness and positive emotions (54, 65), and life satisfaction (64). However, a study from Spain reported no significant change among preschool-aged children and, despite some statistically significant differences in a primary school-aged group, no change was identified for depression or challenging behaviour (55). Similarly, a study from China reported significant changes in anxiety among adolescents but not children, and no change was identified for depression (67). In a Canadian study, significant impact on emotional and behavioural problems was detected for male children enrolled in early childhood education, but not females (59). A study from Australia reported no differences in adolescents' reports on negative affect, nor positive affect, during the pandemic as compared to a baseline period (57). Longitudinal research from the Netherlands reported findings with a developmental perspective; although a slight reduction was seen in externalising problems from pre-pandemic to during pandemic, this was considered in line with developmental trajectory and it was interpreted that the pandemic had decelerated the expected reduction (56). A further study, which used a majority Hispanic/Latinx sample in the United States (US), reported a reduction in emotional and behavioural problems from before to during the pandemic; the reduction was greater for those who had elevated mental health problems pre-pandemic (62).

One of the identified longitudinal studies did not seek to compare pre-and post-pandemic mental health outcomes but instead to track the trajectory of mental health symptomatology during the pandemic period among youth in New York, US (68). This study reported that symptoms of depression and anxiety peaked around late April/early May and then decreased through May to July 2020 (68).

When specifically considering the impact of societal control measures, which have varied internationally, many studies suggested negative impact yet the evidence was mixed. The closure of schools and home quarantine, sometimes referred to as “lockdown,” was reportedly negatively associated with children's mental health outcomes across various international settings (28, 33, 39, 53, 54, 56, 66), as were physical distancing measures (65). Boredom and difficulty concentrating emerged as specific concerns (35, 38), which is understandable given the loss of routine that comes with such control measures. In a couple of studies, the children themselves reported the closure of schools, social isolation and not being able to see friends as the most pressing problems they were facing during the pandemic (50, 64), and a further study reported that decline in support from friends was associated with higher depressive symptoms (63). Yet, other studies reported a lack of association between degree of social distancing engagement (46) and isolation (30) with mental health outcomes, and one study even detected an association between adherence to stay-at-home orders and lower levels of distress (64). Interestingly, one study indicated that greater COVID-19 home confinement concerns were associated with increased generalised anxiety symptoms, yet decreased social anxiety symptoms (60). There was also indication of the societal control measures enhancing family togetherness (33, 38, 63), and in one study around a fifth of the children reported being more satisfied with life during school closures (15).

What Is the Evidence From Different Geographical Regions?

Nearly half of the included studies were conducted in Asia (n = 25), predominantly in China (n = 17/25). As COVID-19 originated in China, it is not surprising that the country is at the forefront of publishing research about the pandemic; yet, it must be recognised that many factors affect investigation time frames. The Chinese government imposed strict containment measures in January 2020, which were eased from February 2020 with localised restrictions re-imposed in new “hotspots.” The number of reported COVID-19 cases has remained low ever since. Although relatively brief, the societal infection control measures in China were among the strictest worldwide. Theoretically, it could be argued that such strict measures had a particularly adverse effect on children and adolescents' mental health. Most of the Chinese research was cross-sectional (n = 15/17), and largely explored depression and/or anxiety symptomatology among children and adolescents (n = 10/15), with prevalence rates ranging from 2 to 44%. Despite the mixed cross-sectional evidence, the two longitudinal studies conducted in China (51, 67) reported increased psychological distress, particularly anxiety symptoms among adolescents.

Further research from Asia was conducted in Bangladesh (n = 1), Iran (n = 2), Israel (n = 1), Taiwan (n = 1), and Turkey (n = 3). All of these studies were cross-sectional. Although some studies only reported prevalence of mental health symptomatology (23) and perceived quality of life (27), others explored mediating factors and indicated evidence of interaction between internet-related behaviours and child and adolescent mental health (24, 26), as well as parental mental health and child and adolescent mental health (7, 25).

Only one included study was from Africa, which was conducted in Nigeria where a nationwide lockdown was introduced in late March 2020 and lifted in May 2020 due to public unrest about the socio-economic consequences. This single study explored the impact of isolation on school students (30); it reported no impact on COVID-19 anxiety and lower examination anxiety among an isolated group compared with a non-isolated group. Since the publication of the study, Nigeria has experienced an increase in COVID-19 cases and imposed further societal lockdown measures.

Of the European studies (n = 16), half were conducted in Italy (n = 8). In February 2020, there was a severe outbreak of COVID-19 in northern Italy, which was placed into lockdown. A national lockdown followed in March 2020, which was gradually eased from May 2020. During the first wave of the pandemic, the number of active cases in Italy was one of the highest in the world. Most of the Italian studies were cross-sectional (n = 7) and reported high levels of mental health and well-being issues among children and adolescents during the pandemic, as well as evidence of interaction between parental mental health and child and adolescent mental health (36, 37). The only longitudinal study conducted in Italy reported that, compared with 1 year earlier, adolescents experienced fewer positive emotions and more negative emotions after the COVID-19 national lockdown (54).

Further research from Europe was conducted in Belgium (n = 1), Spain (n = 4), Germany (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 2), and the United Kingdom (n = 1). Increased depressive symptoms were reported in the UK (66), there was some evidence of increased psychological stress in Germany (53), the evidence from Spain was mixed (38–40, 55), and only slight impact was interpreted in the Netherlands (56, 57). The Belgian study explored the relationship between anxiety and social media (31). All these European countries have implemented a “lockdown” of some form. Yet, the lockdown approach in the Netherlands has been relatively relaxed compared to other European countries, with the government implementing its so-called “intelligent lockdown” whereby people were asked to stay home but were still allowed to move around freely as long as they kept a distance of 1.5 m to others. The varying “lockdown” approaches could, in part, account for the varying impacts on child and adolescent mental health; yet, it is difficult to conclude this from the available evidence.

There were 13 studies from North America and most of the studies (n = 10/13) were conducted in the US and the remaining (n = 3/13) in Canada. The majority of the US studies were cross-sectional (n = 6/10) and reported: negative association between the pandemic and societal control measures and the mental health of children and adolescents (43, 47); how parental mental health was associated to their children/adolescents' mental health (43, 48) or how parents' and children's well-being in the post-crisis period was strongly associated with the number of crisis-related hardships (such as job loss, income loss, caregiving burden, and illness) that the family experienced (45). One study reported that children's mental health fell within the clinical range, however, mental health symptoms were positively associated with the number of children in the home (44). Oosterhoff et al. (46) did not find any evidence of a potential association between degree of social distancing nor any indicator of mental health. Three of the longitudinal studies reported a significant increase, albeit small, in symptoms of mental ill-health during the pandemic (compared to before the pandemic) (60, 63, 68).

The two Canadian cross-sectional studies reported: 43% of adolescents expressed they were “very concerned” about the pandemic (42) while Carroll et al. (41) reported that, according to parents, almost half (49%) of children had very little concern about COVID-19, 38% were somewhat concerned, and 7% were very much concerned. Browne et al. (59), the only longitudinal study from Canada, reported that male children's mental health problems worsened significantly during the pandemic. No significant differences over time were observed for females.

There were two cross-sectional studies conducted in South America as another geographical region: one from Brazil and the other from Ecuador. Garcia de Avila (49) assessed the prevalence of anxiety among Brazilian school-children and reported a high prevalence of anxiety (19%), especially among children with parents with essential jobs and those who were social distancing without parents. Asanov et al. (50) assessed the mental health of Ecuadorian high-school students during the COVID-19 quarantine and reported that 16% of students had mental health scores that indicated major depression.

The two studies conducted in Australia were both longitudinal studies and reported the negative impact of COVID-19 and associated societal control measures on the mental health of children and adolescents. Magson et al. (64) found significant increases in depression and anxiety symptoms as well as a significant decrease in life satisfaction among adolescents, from before to during the pandemic, which was particularly pronounced among girls. Similarly, Munasinghe et al. (65) investigated changes in well-being during the early period of physical distancing among adolescents and results highlighted that the implementation of physical distancing interventions was associated with decreases in well-being.

Are There Any Protective Factors Associated With a Lower Likelihood of Mental Health Problem Outcomes?

Some potential protective factors, i.e., characteristics associated with a lower likelihood of negative outcomes or that reduce the negative impact, were identified in the scoping review. With regard to internal protective factors, strong resilience and positive emotion regulation were associated with better mental health outcomes among adolescents (17, 20, 53). On a behavioural level, physical activity was reportedly associated with improved mood among children and adolescents (11, 21). The social environment also appears to play a role, with parental self-efficacy (36), family functioning (62), and emotion regulation (25) as well as level of social support (12) associated with better outcomes.

Are There Any Factors Associated With a Higher Likelihood of Mental Health Problem Outcomes?

A number of factors associated with poorer mental health outcomes were identified in the scoping review. The level of concern about COVID-19 among adolescents was found to be associated with poorer mental health outcomes (29, 42), and could be related to internal factors such as emotional reactivity and experiential avoidance (29, 53) as well as exposure to excessive information (28). Similarly, greater COVID-19 school concerns were associated with increased depression symptoms (60). The presence of COVID-19 cases in adolescents' communities contributed to poorer mental health, which was more pronounced for older adolescents (13). Several studies indicated that parental mental health problems were related to poorer child and adolescent outcomes (7, 16, 25, 37, 48, 53, 56), which strengthens the evidence that social environment is an important factor. Internet, social media and video game use was another common research topic, evidence from which suggests negative association with child and adolescent mental health (9, 18, 24, 26, 31, 51, 67).

Discussion

This scoping review brings together all the published studies exploring child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic around the world, published until December 2020, and all longitudinal studies until early May 2021. In just over a year there were 59 studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review. The figure would have been higher if the focus of the second review process had not been narrowed to longitudinal studies only. This highlights the extensive research activity during the pandemic period. Yet, only 15 of the studies adopted a longitudinal research design, which means evidence on how the COVID-19 pandemic and societal control measures have affected the mental health of children and adolescents is still somewhat limited.

The definition of “child” and “adolescent” varied across the included studies; yet, most reportedly involved adolescents (n = 30; 63%). Around a third of the studies relied only on parent reports to measure child and adolescent mental health (n = 19: 32%). Across all the included studies, a range of outcome measures were used to assess mental health including bespoke questions formulated for the purpose of the research (Tables 2, 3). It is important to highlight here the timing of when data was collected and how it changed from one study to the other: in some of the studies, data were collected at the very beginning of the pandemic (already from February 2020); some other studies collected their data during the first COVID-19 peak (March, April, or May 2020) according to each country; and in some other studies data were collected when the pandemic seemed to be under control and societal control measures were no longer very strict. There is some evidence to suggest that the timing of data collection could affect findings (68).

Most studies reported negative impact of COVID-19 on child and adolescent mental health outcomes, yet the evidence was mixed (Tables 2, 3). This was also the case for studies investigating societal control measures. Strong resilience, positive emotion regulation, physical activity, parental self-efficacy, family functioning and emotional regulation, and social support were reported as protective factors. On the contrary, emotional reactivity and experiential avoidance, exposure to excessive information, COVID-19 school concerns, presence of COVID-19 cases in the community, parental mental health problems, and high internet, social media, and video game use were all identified as potentially harmful factors.

Collating the evidence in a scoping review such as this provides an initial step toward addressing negative impact of the pandemic and child and adolescent mental health. By taking the various findings across the body of research into consideration, interventional strategies can be developed. Taking action now could mitigate longer term impact on the overall health and mental health of children and adolescents. Not only could this be helpful in the present day, but it could also be informative for future pandemics. In terms of the nature of intervention, the aforementioned protective and harmful factors identified in the literature provide grounding for potential intervention targets.

Under this unprecedented and current situation due to the COVID-19 pandemic and societal infection control measures, the levels of physical activity and sedentary behaviour of children and adolescents are important aspects to be considered. Physical activity was shown to be associated with better mood state during the pandemic by two studies (11, 21). Both studies were conducted in China, which somewhat limits the generalisability of the findings. However, the extant literature on physical activity and mental health outcomes is supportive of this relationship: physical activity and mental health (69–73). COVID-19 is an ongoing pandemic that may affect physical activity patterns and sedentary time in the longer-term (74). These results highlight the need for interventions to keep children and adolescents active and fit during the pandemic (74, 75). A number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses assessing the potential of school-based interventions have reported physical activity as a positive and promising strategy to improve child and adolescent mental health (73, 76, 77); however, an alternative approach in the context of a pandemic should be investigated since so many stay-at-home orders are intermittently in place.

Another protective factor identified in the review that could be considered as an intervention target is parental self-efficacy (36). Conversely, parental mental health problems were associated with poorer outcomes among children and adolescents (7, 16, 25, 37, 48). Morelli et al. (36) make the case that, although parents are likely to be exposed to high levels of stress during the pandemic period, support can be offered in how to introduce daily structure and promote positive emotional functioning in their children. There are evidence-based parenting programs that cover these topics (78). Guidance on how to talk to children about the COVID-19 pandemic, including the loss of loved ones, has been published (79) as well as a picture book to read together with children (80).

Spending more time using social media and reading the news had a strong negative association with mental health outcomes (9). Some of the studies discussed that feeling lonely and anxious motivated children and adolescents to use social media more often mainly to cope with the situation and with the lack of social contact; however, it resulted in even more negative feelings of anxiety, depression and loneliness (43). An aspect related to this that should be considered more generally is screen use (81). Excessive screen use is known to impact on sleep and physical activity (82) and has been linked with poorer language skills, lower school performance and classroom engagement, social/emotional difficulties, and reduced psychological well-being (81). Although screen media use among children and adolescents can be used with positive intentions, such as for education or to interact with friends and family and can award parents time to complete necessary tasks, it is an area of concern, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (81, 83). Research on online social network site (SNS) addiction, such as excessive and compulsive online social networking, is growing (84). Not being a formally recognised diagnosis, well-documented therapeutic interventions are difficult to find. However, interventions and preventive efforts proven effective for other addictive behaviours, such as self-help strategies and therapies, can be applied to SNS addiction (84). In 2019, WHO released guidelines (85) stating that screen time is not recommended for children 1 year or under and for children 2–4 years old, the daily sedentary screen time should not be more than 1 h. Reading and storytelling are promoted as alternative sedentary activities (85).

This review comes with some limitations. Certain requirements that are placed on a more comprehensive systematic review, e.g., that the relevance of all studies must be checked by two independent reviewers, were omitted to be able to compile the findings from the literature in an efficient manner. This entails limitations in both accuracy and the scope of the material. Most of the included studies had a cross-sectional design, and therefore the direction of the association cannot be inferred, as the results do not provide knowledge about causation, but only about mathematical relationships. Yet, the second search performed to update the review with a particular focus on longitudinal studies can be considered a strength. Other methodological limitations of the studies include common use of convenience sampling, parent report in place of direct report in several studies, as well as a lack of validated outcome measures in some studies. Finally, the heterogeneity of the included studies and geographical variation limits comparability, and negates the possibility of meta-analysis. Therefore, only narrative description of the study findings was provided in the review. For all the above limitations, the results should be interpreted with caution. As more studies are added to the body of literature, the formation of the evidence could shift. This overview should therefore be seen as a “snapshot” of the current literature.

Conclusions

Due to the methodological heterogeneity of the studies included in this scoping review, as well as the low number of longitudinal studies and geographical variation, it is challenging to draw definitive conclusions about the real impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and societal infection control measures on the mental health of children and adolescents. However, the existing body of research gives some insight to potential protective and harmful factors that can be used to inform how parents, clinicians and policy makers can take action to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. From the protective and harmful factors identified in the scoping review, some potential intervention targets have been identified. Namely, interventions to promote physical activity and reduce screen time among children and adolescents, as well as parenting support programs to increase parental self-efficacy and promote positive and warm parent-child relationships.

Author Contributions

AS conceived the idea for the literature search. JM led on designing the search, with support from GW. JM led on conducting the literature search and analysing the data. GW, NJ, and AS contributed to the interpretation of the data. JM and GW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NJ and AS critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swedish National Agency of Public Health (Folkhälsomyndigheten) [Grant # 03303-2020-2.3.2].

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors highly appreciate University librarian Kazuko Gustafson's collaboration for this review, who not only developed a multi-database systematic search strategy but also ran the search in the various databases for us.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.711791/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Nadeem MS, Zamzami MA, Choudhry H, Murtaza BN, Kazmi I, Ahmad H, et al. Origin, potential therapeutic targets and treatment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Pathogens. (2020) 9:307. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9040307

2. Hossain MM, Sultana A, Purohit N. Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: a systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. Epidemiol Health. (2020) 42:e2020038. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2020038

3. Manuell ME, Cukor J. Mother Nature versus human nature: public compliance with evacuation and quarantine. Disasters. (2011) 35:417–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01219.x

4. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. (2020) 395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

5. Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020) 59:1218–39.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

6. Arskey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

7. Yeasmin S, Banik R, Hossain S, Hossain MN, Mahumud R, Salma N, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 117:105277. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105277

8. Chen S, Cheng Z, Wu J. Risk factors for adolescents' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison between Wuhan and other urban areas in China. Global Health. (2020) 16:96. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00627-7

9. Dong H, Yang F, Lu X, Hao W. Internet addiction and related psychological factors among children and adolescents in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:751. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00751

10. Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, Huang Y, Miao J, Yang X, et al. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord. (2020) 275:112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

11. Kang S, Sun Y, Zhang X, Sun F, Wang B, Zhu W. Is physical activity associated with mental health among Chinese adolescents during isolation in COVID-19 pandemic? J Epidemiol Glob Health. (2020) 11:26–33.

12. Qi MMS, Zhou S-JMS, Guo Z-C, Zhang L-G, Min H-J, Li X-MMS, et al. The effect of social support on mental health in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Adolescent Health. (2020) 67:514. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.001

13. Ren H, He X, Bian X, Shang X, Liu J. The protective roles of exercise and maintenance of daily living routines for Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 quarantine period. J Adolesc Health. (2020) 68:35–42.

14. Shuang-Jiang Z, Li-Gang Z, Lei-Lei W, Zhao-Chang G, Jing-Qi W, Jin-Cheng C, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Euro Child Adolescent Psychiatry. (2020) 29:749–58. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4

15. Tang S, Xiang M, Cheung T, Xiang YT. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: the importance of parent-child discussion. J Affect Disord. (2020) 279:353–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.016

16. Tso WWY, Wong RS, Tung KTS, Rao N, Fu KW, Yam JCS, et al. Vulnerability and resilience in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020). doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01680-8. [Epub ahead of print].

17. Yang D, Swekwi U, Tu CC, Dai X. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Wuhan's high school students. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 119:105634. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105634

18. Yue J, Zang X, Le Y, An Y. Anxiety, depression and PTSD among children and their parent during 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in China. Curr Psychol. (2020). doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01191-4. [Epub ahead of print].

19. Zhang C, Ye M, Fu Y, Yang M, Luo F, Yuan J, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teenagers in China. J Adolesc Health. (2020) 67:747–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.026

20. Zhang Q, Zhou L, Xia J. Impact of COVID-19 on emotional resilience and learning management of middle school students. Med Sci Monit. (2020) 26:e924994. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924994

21. Zhang X, Zhu W, Kang S, Qiu L, Lu Z, Sun Y. Association between physical activity and mood states of children and adolescents in social isolation during the COVID-19 epidemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207666

22. Zhou J, Yuan X, Qi H, Liu R, Li Y, Huang H, et al. Prevalence of depression and its correlative factors among female adolescents in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. Global Health. (2020) 16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00601-3

23. Darvishi E, Golestan S, Demehri F, Jamalnia S. A cross-sectional study on cognitive errors and obsessive-compulsive disorders among young people during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019. Act Nerv Super. (2007) 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s41470-020-00077-x

24. Fazeli S, Mohammadi Zeidi I, Lin CY, Namdar P, Griffiths MD, Ahorsu DK, et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress mediate the associations between internet gaming disorder, insomnia, and quality of life during the COVID-19 outbreak. Addict Behav Rep. (2020) 12:100307. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100307

25. Shorer M, Leibovich L. Young children's emotional stress reactions during the COVID-19 outbreak and their associations with parental emotion regulation and parental playfulness. Early Child Dev Care. (2020) 11:1–11. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2020.1806830

26. Lin MP. Prevalence of internet addiction during the COVID-19 outbreak and its risk factors among junior high school students in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228547

27. Adibelli D, Sümen A. The effect of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on health-related quality of life in children. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 119:105595. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105595

28. Kilinçel S, Kilinçel O, Muratdagi G, Aydin A, Usta MB. Factors affecting the anxiety levels of adolescents in home-quarantine during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2020). doi: 10.1111/appy.12406. [Epub ahead of print].

29. Seçer I, Ulaş S. An investigation of the effect of COVID-19 on OCD in youth in the context of emotional reactivity, experiential avoidance, depression and anxiety. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2020) 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00322-z

30. Rakhmanov O, Shaimerdenov Y, Dane S. The effects of COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety in secondary school students. J Res Med Dent Sci. (2020) 8:186–90. Available online at: https://www.jrmds.in/articles/the-effects-of-covid19-pandemic-on-anxiety-in-secondary-school-students-58209.html

31. Cauberghe V, Van Wesenbeeck I, De Jans S, Hudders L, Ponnet K. How adolescents use social media to cope with feelings of loneliness and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdown. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020) 24:250–7.

32. Crescentini C, Feruglio S, Matiz A, Paschetto A, Vidal E, Cogo P, et al. Stuck outside and inside: an exploratory study on the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on Italian parents and children's internalizing symptoms. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:586074. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586074

33. Cusinato M, Iannattone S, Spoto A, Poli M, Moretti C, Gatta M, et al. Stress, resilience, and well-being in italian children and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228297

34. di Cagno A, Buonsenso A, Baralla F, Grazioli E, Di Martino G, Lecce E, et al. Psychological impact of the quarantine-induced stress during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak among Italian athletes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17238867

35. Di Giorgio E, Di Riso D, Mioni G, Cellini N. The interplay between mothers' and children behavioral and psychological factors during COVID-19: an Italian study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020). doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01631-3. [Epub ahead of print].

36. Morelli M, Cattelino E, Baiocco R, Trumello C, Babore A, Candelori C, et al. Parents and children during the COVID-19 lockdown: the influence of parenting distress and parenting self-efficacy on children's emotional well-being. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:584645. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.584645

37. Spinelli M, Lionetti F, Pastore M, Fasolo M. Parents' stress and children's psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1713. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01713

38. Orgilés M, Morales A, Delvecchio E, Mazzeschi C, Espada JP. Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:579038. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579038

39. Ezpeleta L, Navarro JB, de la Osa N, Trepat E, Penelo E. Life Conditions during COVID-19 lockdown and mental health in Spanish adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–11. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197327

40. Romero E, López-Romero L, Domínguez-Álvarez B, Villar P, Gómez-Fraguela JA. Testing the effects of COVID-19 confinement in spanish children: the role of parents' distress, emotional problems and specific parenting. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–23. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17196975

41. Carroll N, Sadowski A, Laila A, Hruska V, Nixon M, Ma DWL, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on health behavior, stress, financial and food security among middle to high income Canadian families with young children. Nutrients. (2020) 12:1–14. doi: 10.3390/nu12082352

42. Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM. Physically isolated but socially connected: psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can J Behav Sci Rev Can Sci Comport. (2020) 52:177–87. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000215

43. Drouin M, McDaniel BT, Pater J, Toscos T. How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020) 23:727–36. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0284

44. Fitzpatrick O, Carson A, Weisz JR. Using mixed methods to identify the primary mental health problems and needs of children, adolescents, and their caregivers during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2020). doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01089-z. [Epub ahead of print].

45. Gassman-Pines A, Ananat EO, Fitz-Henley J 2nd. COVID-19 and parent-child psychological well-being. Pediatrics. (2020) 146:1–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-007294

46. Oosterhoff BP, Palmer CAP, Wilson JMS, Shook NP. Adolescents' motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with mental and social health. J Adolescent Health. (2020) 67:179. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.004

47. Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, Lovell K, Halvorson A, Loch S, et al. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Pediatrics. (2020) 146:1–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016824

48. Russell BS, Hutchison M, Tambling R, Tomkunas AJ, Horton AL. Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent-child relationship. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2020) 51:671–82. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01037-x

49. Garcia de Avila MA, Hamamoto Filho PT, Jacob F, Alcantara LRS, Berghammer M, Jenholt Nolbris M, et al. Children's anxiety and factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic: an exploratory study using the children's anxiety questionnaire and the numerical rating scale. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165757

50. Asanov I, Flores F, McKenzie D, Mensmann M, Schulte M. Remote-learning, time-use, and mental health of Ecuadorian high-school students during the COVID-19 quarantine. World Dev. (2021) 138:105225. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105225

51. Chen I-H, Chen C-Y, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Lin C-Y, Li X-D, et al. Problematic internet-related behaviors mediate the associations between levels of internet engagement and distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 lockdown: a longitudinal structural equation modeling study. J Behav Addictions JBA. (2021) 10:135–48. doi: 10.1556/2006.2021.00006

52. Teng Z, Pontes HM, Nie Q, Griffiths MD, Guo C. Depression and anxiety symptoms associated with internet gaming disorder before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study. J Behav Addict. (2021) 10:169–80.

53. Paschke K, Arnaud N, Austermann MI, Thomasius R. Risk factors for prospective increase in psychological stress during COVID-19 lockdown in a representative sample of adolescents and their parents. BJPsych Open. (2021) 7:e94. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.49

54. Alivernini F, Manganelli S, Girelli L, Cozzolino M, Lucidi F, Cavicchiolo E. Physical distancing behavior: the role of emotions, personality, motivations, and moral decision-making. J Pediatric Psychol. (2020) 46:15–26. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa122

55. Giménez-Dasí M, Quintanilla L, Lucas-Molina B, Sarmento-Henrique R. Six weeks of confinement: psychological effects on a sample of children in early childhood and primary education. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:590463. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590463

56. Achterberg M, Dobbelaar S, Boer OD, Crone EA. Perceived stress as mediator for longitudinal effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on wellbeing of parents and children. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:2971. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81720-8

57. Janssen LHC, Kullberg MJ, Verkuil B, van Zwieten N, Wever MCM, van Houtum L, et al. Does the COVID-19 pandemic impact parents' and adolescents' well-being? An EMA-study on daily affect and parenting. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0240962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240962

58. Bignardi G, Dalmaijer ES, Anwyl-Irvine AL, Smith TA, Siugzdaite R, Uh S, et al. Longitudinal increases in childhood depression symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown. Arch Dis Childhood. (2020) 106:791–7.

59. Browne DT, Wade M, May SS, Maguire N, Wise D, Estey K, et al. Children's mental health problems during the initial emergence of COVID-19. Can Psychol. (2021) 62:65–72. doi: 10.1037/cap0000273

60. Hawes MT, Szenczy AK, Klein DN, Hajcak G, Nelson BD. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. (2021). doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005358. [Epub ahead of print].

61. Hawes MT, Szenczy AK, Olino TM, Nelson BD, Klein DN. Trajectories of depression, anxiety and pandemic experiences; a longitudinal study of youth in New York during the Spring-Summer of 2020. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 298:113778. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113778

62. Penner F, Hernandez Ortiz J, Sharp C. Change in youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in a majority hispanic/latinx US sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2021) 60:513–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.12.027

63. Rogers AA, Ha T, Ockey S. Adolescents' perceived socio-emotional impact of COVID-19 and implications for mental health: results from a U.S.-based mixed-methods study. J Adolesc Health. (2020) 68:43–52.

64. Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. (2020) 50:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9

65. Munasinghe S, Sperandei SP, Freebairn LP, Conroy EP, Jani HM, Marjanovic SM, et al. The impact of physical distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic on health and well-being among australian adolescents. J Adolescent Health. (2020) 67:653. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.008

66. Bignardi G, Dalmaijer ES, Anwyl-Irvine AL, Smith TA, Siugzdaite R, Uh S, et al. Longitudinal increases in childhood depression symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown. Arch Dis Childhood. (2020).

67. Teng Z, Pontes HM, Nie Q, Griffiths MD, Guo C. Depression and anxiety symptoms associated with internet gaming disorder before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study. J Behav Addict. (2021).

68. Hawes MT, Szenczy AK, Olino TM, Nelson BD, Klein DN. Trajectories of depression, anxiety and pandemic experiences; a longitudinal study of youth in New York during the Spring-Summer of 2020. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 298:113778.

69. Rodriguez-Ayllon M, Cadenas-Sánchez C, Estévez-López F, Muñoz NE, Mora-Gonzalez J, Migueles JH, et al. Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. (2019) 49:1383–410. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01099-5

70. Radovic S, Gordon MS, Melvin GA. Should we recommend exercise to adolescents with depressive symptoms? A meta-analysis. J Paediatrics Child Health. (2017) 53:214–20. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13426

71. Dale LP, Vanderloo L, Moore S, Faulkner G. Physical activity and depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in children and youth: an umbrella systematic review. Mental Health Phys Activity. (2019) 16:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2018.12.001

72. Korczak DJ, Madigan S, Colasanto M. Children's physical activity and depression: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. (2017) 139:1–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2266

73. Wegner M, Amatriain-Fernández S, Kaulitzky A, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Machado S, Budde H. Systematic review of meta-analyses: exercise effects on depression in children and adolescents. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:81. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00081

74. Xiang M, Zhang Z, Kuwahara K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents' lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. (2020) 63:531–2. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.013

75. Pavlovic A, DeFina LF, Natale BL, Thiele SE, Walker TJ, Craig DW, et al. Keeping children healthy during and after COVID-19 pandemic: meeting youth physical activity needs. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:485. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10545-x

76. Andermo S, Hallgren M, Nguyen T-T-D, Jonsson S, Petersen S, Friberg M, et al. School-related physical activity interventions and mental health among children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med Open. (2020) 6:25. doi: 10.1186/s40798-020-00254-x

77. Brown HE, Pearson N, Braithwaite RE, Brown WJ, Biddle SJ. Physical activity interventions and depression in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. (2013) 43:195–206. doi: 10.1007/s40279-012-0015-8

78. Barlow J, Coren E. The effectiveness of parenting programs: a review of campbell reviews. Res Social Work Prac. (2018) 28:99–102. doi: 10.1177/1049731517725184

79. Rapa E, Dalton L, Stein A. Talking to children about illness and death of a loved one during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Child Adolescent Health. (2020) 560–2. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30174-7

80. Wilson K, Jenner E, Roberts N. Coronavirus: A Book for Children: Nosy Crow. London: Nosy Crow Ltd (2020).

81. Stienwandt S, Cameron EE, Soderstrom M, Casar MJ, Le C, Roos LE. Keeping kids busy: family factors associated with hands-on play and screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv. (2020) 1–45. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/prtyf

82. Arufe-Giráldez V, Sanmiguel-Rodríguez A, Zagalaz-Sánchez ML, Cachón-Zagalaz J, González-Valero G. Sleep, physical activity and screens in 0-4 years Spanish children during the COVID-19 pandemic: were the WHO recommendations met? J Hum Sport Exerc. (2020). doi: 10.14198/jhse.2022.173.02

83. Lau EYH, Lee K. Parents' views on young children's distance learning and screen time during COVID-19 class suspension in Hong Kong. Early Educ Dev. (2020) 32:6. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2020.1843925

84. Andreassen CS. Online social network site addiction: a comprehensive review. Curr Addict Rep. (2015) 2:175–84. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0056-9

Keywords: COVID-19, pandemic, children, adolescents, mental health, scoping review

Citation: Marchi J, Johansson N, Sarkadi A and Warner G (2021) The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Societal Infection Control Measures on Children and Adolescents' Mental Health: A Scoping Review. Front. Psychiatry 12:711791. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.711791

Received: 19 May 2021; Accepted: 13 August 2021;

Published: 06 September 2021.

Edited by:

Ylva Svensson, University West, SwedenReviewed by:

Wanderlei Abadio de Oliveira, Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas, BrazilAdekunle Adedeji, North-West University, South Africa

Copyright © 2021 Marchi, Johansson, Sarkadi and Warner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Georgina Warner, Z2VvcmdpbmEud2FybmVyQHB1YmNhcmUudXUuc2U=

Jamile Marchi

Jamile Marchi Nina Johansson

Nina Johansson Anna Sarkadi

Anna Sarkadi Georgina Warner

Georgina Warner