ICD-11 Personality Disorder: The Indispensable Narrative Turn

The field of personality disorders (PD) is taking an important step away from a categorical approach by inviting a dimensional understanding of conceptualizing and diagnosing manifestations of personality pathology (1). This means that, in the long awaited 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), the core of PD is considered on a spectrum of intra- and interpersonal dysfunctions (2). Let me begin this paper by declaring my sympathy for the dimensional model. I do, however, encourage this shift to incorporate an aspect of (maladaptive) personality that is gaining momentum in PD research—a person's narrative identity. In the following, I illustrate why narrative identity contributes with an indispensable aspect to ICD-11's self-function that revolves around “stability and coherence of one's sense of identity” (1). For additional and more thorough arguments on this matter see also Lind, Dunlop and Sharp (under review).

Narrative Identity: The Temporally Coherent Self

Narrative identity is the internal and dynamic story of a person's life (3). As individuals are living unique lives, each has a unique story to tell. Narrative identity (i.e., the self as author) constitutes the most unique aspect of a person's personality (4) and conveys the innermost perspective of personhood relative to a shared-by-many trait profile (i.e., the self as actor) and general social-cognitive abilities [i.e., the self as agent; (5)].

Narrative identity helps us understand and express to others who we once were, who we are today, and who we may become in the future (5) and therefore affirms us with a sense of self-continuity (i.e., coherence) and stability that, through time and place, we continue to stay the same person (4). The emergence of a coherent narrative identity occurs in adolescence, as these individuals are faced with the developmental task to form a mature identity (6). Narrative identity emerges as a final, organizing element of personality after traits and social-cognitive abilities are established (3).

The emergence of Autobiographical Reasoning is a crucial cognitive tool conveying the competence to construct global coherence in the story (7). Autobiographical reasoning is the underlying reflective process in which past events are interpreted, organized, and evaluated to construct temporally, culturally, causally, and thematically coherent accounts of a person's life (8). Temporal coherence refers to the understanding of how events are timely related in the life story and is, at least in Western countries, typically expressed as a chronological order of events (8). Cultural coherence refers to the ability to integrate normative cultural life events in the story [e.g., getting a job and having children; (9)]. Causal coherence encompasses the ability to create meaningful connections between events and periods across the life story and how events have contributed to both change and/or stability within the person. Finally, thematic coherence relates to the ability to establish thematic links across a person's life. While causal- and thematic coherence are more sophisticated processes of coherence beginning to emerge in mid to late adolescence, autobiographical reasoning related to temporal and cultural coherence has an earlier starting point (7, 8).

Narrative Identity as a Vital Self-Function Within ICD-11

Autobiographical reasoning provides nuance to conceptualizing and assessing “stability and coherence of one's sense of identity” within ICD-11 (1) by tackling coherence in terms of at least four distinct dimensions (i.e., chronological, cultural, causal, and thematic), while also providing an indicator of global coherence (8). With diminished autobiographical reasoning, a person's narrative identity appears disorganized and fragmented. A recent systematic review [see (10)] based on the last decade's studies on PD and narrative identity indicates that a disturbed autobiographical reasoning in people manifesting PD could play a key role in inducing a more incoherent temporal sense of self [i.e., chronological, cultural, causal, and thematic; (8)]. Note that the majority of these studies are based on borderline PD (BPD). That is, adults with BPD [e.g., (11–13)] construct narrative identities that are less chronologically coherent (i.e., lack orientation and structure) compared to control participants without BPD and people with OCD. Associations have also been found between elevated BPD features in adolescents and less chronological coherent narratives (14). Adults with BPD construct less normative narratives (12) compared to a community sample and people with OCD indicating impoverished cultural coherence in BPD. Adler and colleagues (11) showed negative associations between BPD and the ability to link stories to the person's larger sense of self when compared to a matched control group without BPD and Lind and colleagues found somewhat complex but overly negative causal connections between stories and between stories and the self in people with PD compared to a matched control group without PD pathology (15, 16). Furthermore, prominent narrative themes are present, however problematic, in both adults and adolescents manifesting PD. That is, for those with PD, narrative identity is dominated by themes of thwarted agency (stories of defeat, loss of control, victimization, failures) and strong needs for communion (e.g., belongingness and love) that are unfulfilled [e.g., interpersonal disappointments, betrayal, loneliness; e.g., (11, 15, 16, Lind et al., under review)]. A potential fifth and distinct aspect of coherence, engrained in the attachment literature (17, 18), involves inconsistency (e.g., contradictions) and a lack of plausibility of the narratives (19) and has been associated with, at least, borderline PD [e.g., (20)]. To recap, people manifesting PD show problematic autobiographical reasoning, reflected in diverse types of thwarted coherence. Adolescents manifesting BPD show reduced temporal coherence (14) as well as thematic disturbances related to diminished themes of communion fulfillment and particularly agency (Lind et al., under review) indicating that they struggle with both developmentally early and more sophisticated autobiographical reasoning (8).

Discussion

Narrative Identity as a Marker of Self-Function in ICD-11

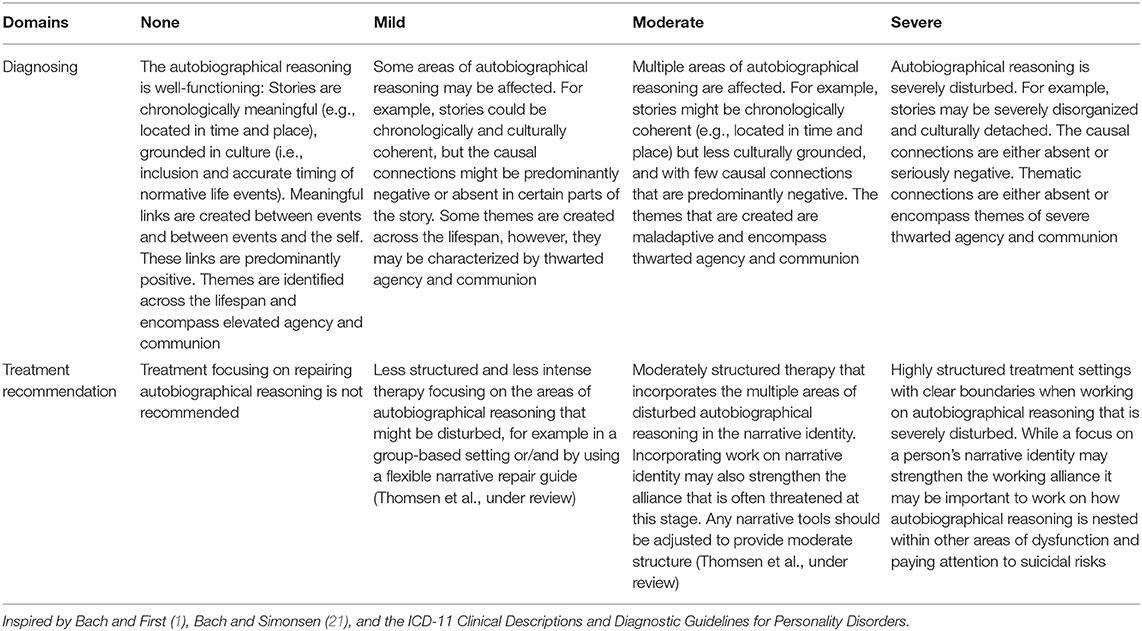

In ICD-11, aspects of self-function are evaluated on a severity scale when conceptualizing and diagnosing PD. Autobiographical reasoning in narrative identity could be integrated in a similar way, to nuance the coherence aspect of the self-function (see Table 1 for a tentative suggestion). Moving forward, it will be crucial to identify clear cut-off points (i.e., narrative markers) to determine when the autobiographical reasoning converts from being adaptive to mildly-severely disturbed. Lind, Thomsen and colleagues (16) showed that differences in narrative identity predicted group membership (PD vs. control) even after controlling for depressive symptoms—an important first step. Since associations have been shown between inpatient adolescents with PD features and problematic chronological and thematic coherence [(14), Lind et al., under review], autobiographical reasoning could be a critical precursor of full-blown PD together with other identity aspects (22, 23). Because narrative chronology emerges earlier in development than thematic coherence, the former may be used as a more robust narrative marker of early on-set of maladaptive development. Future research should also clearly map out the unique aspects of autobiographical reasoning related to PD and those that might tap into a general p factor (24).

Table 1. Tentative “Cross Walk” for level of personality functioning focusing on autobiographical reasoning within narrative identity.

Assessment of Autobiographical Reasoning in ICD-11

Narrative identity is typically assessed using the Life Story Interview (25). This semi-structured interview provides rich material on the person's own interpretation on the self and the lived life. Narrative characteristics such as autobiographical reasoning are then assessed using previously validated coding systems. Some crucial aspects must, however, be considered before integrating existing narrative identity assessment in the context of PD. First, the LSI prompts for a prototypical life story and narration in Western countries. It may not adequately capture the normative reasoning and story-telling in other parts of the world, in which some adjustment will be required. Second, autobiographical reasoning covers a niche of personally significant reasoning distinctive from general cognitive difficulties. For example, the disturbances related to autobiographical reasoning in PD were evident even when the control group considered was matched on education [e.g., (11, 15, 16)]. Finally, existing assessment is based on the typically developing personality and, while researchers have started to create coding systems from a clinical stance (e.g., Lind and Dunlop, unpublished coding manual), more is needed to accurately assess personality (dys)functioning within ICD-11. Echoing Hoopwood (26), clinical and basic personality psychologists interact with each other less than they should. This would be a golden opportunity to do so, especially since no official instrument yet exists assessing self- and interpersonal functioning in ICD-11 [e.g., (1, 21)]. In DSM-5's Alternative Model for Personality Disorders [e.g., (27)], identity is evaluated based on the subdomains of self-differentiation, self-esteem, and emotional range and regulation and do not adequately capture the coherent sense of self as it is articulated in ICD-11. As such, adopting existing assessment from DSM-5 may be less than ideal if the temporal aspect of the self should be adequately integrated within forthcoming measurements.

Both written (28) and video-material (29) of the LSI have been used to successfully assess levels of self-functioning in community samples whereas the other-function (e.g., mentalization) were more challenging to assess. Recently, a modified LSI version was used to assess people with BPD's vicarious life story of a parent. That is, the patients were asked to tell their mother or father's life story—to put themselves in their parent's shoes and elaborate and reflect on this story from the parent's perspective (Lind et al., in preparation). Aspects of autobiographical reasoning (i.e., a temporal other- reasoning) and meta-cognition (30), a concept related to mentalization, were successfully assessed. The vicarious perspective (31) could be a fruitful area for future assessment of other-functioning in ICD-11.

Narrative Identity and Treatment: Implications for ICD-11

Prominent researchers in the field have suggested that the severity of personality functioning can be used as a decision tool to determine the optimal treatment and treatment intensity in a “personalized medicine manner” (22). Given the importance of a coherent identity in ICD-11 [e.g., (1)], the narrative identity seems significant. Several prominent researchers and clinicians [e.g., (32–35)] have emphasized the relevance of integrating narrative identity within psychotherapy. In my own research, I stress the importance of implementing narrative identity within treatment of PD [e.g., (10, 14, 15)] and particularly in the context of the dimensional model (Lind et al., under review, see also 27). Bach and Simonsen (21) further suggested that narrative identity could be a potential mechanism of change in therapy, especially for moderate-to-severe personality disorders in the context of ICD-11. Integrating narrative identity within a treatment setting has several advantages: first, it fits within “personalized/narrative medicine” by emphasizing the importance of a person's unique life, and second, it offers an empathic setting in which the therapist is giving voice and ownership to the patient's story creating a unique and vulnerable window into the person's sense of self nurturing epistemic trust [i.e., the willingness to consider new knowledge as trustworthy and relevant to the self: (36)] and building a working alliance with the patient (21). In Table 1, I offer tentative suggestions on how autobiographical reasoning can be considered within a therapeutic context and dependent on the severity of functioning in ICD-11. Importantly, the origin and underlying mechanisms of reasoning difficulties are complex and can be interpreted and treated from multiple therapeutic approaches. Together with close colleagues, I have recently developed a narrative repair guide to assist people with mental illness in gaining enhanced insight and more adaptive story telling (Thomsen et al., under review). This guide could be helpful in the context of PD and likely in combination with more cognitive evidence-based treatments. However, approaches that perceive the reasoning abnormalities as emanating from splitting-based defense mechanisms [e.g., (17, 37)] or mentalizing difficulties (38) endorsing psychodynamic interventions may also be effective. For example, themes of narrative agency were improved in people manifesting PD after psychodynamic therapy (15). That is, the self has been highlighted as a driver of personality functioning [i.e., Criterion A; (39)]. Strengthening autobiographical reasoning (i.e., the self as author) may scaffold a healthy organization of personality regardless of whether these reasoning challenges are interpreted from a more cognitive or psychodynamic perspective.

Concluding Remarks

In this paper I stress the importance of considering narrative identity and particularly the role of autobiographical reasoning as a marker of self-(dys)function in the context of ICD-11's dimensional model of PD. I highlight implications for therapy as we dive deeper into the new dimensional era.

Author Contributions

ML contributed solely to all aspects of this paper.

Funding

The author's salary was paid by Danmarks Frie Forskningsfond (8023-00029B).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Sune Bo, William L. Dunlop, and the two reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

References

1. Bach B, First MB. Application of the ICD-11 classification of personality disorders. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18:351. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1908-3

2. Tyrer P, Mulder R, Kim Y, Crawford MJ. The development of the ICD-11 classification of personality disorders: an amalgam of science, pragmatism, and politics. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. (2019) 15:481–502. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095736

3. McAdams DP. What do we know when we know a person. J Pers. (1995) 63:365–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00500.x

4. Dunlop WL. Contextualized personality, beyond traits. Eur J Pers. (2015) 29:310–25. doi: 10.1002/per.1995

5. McAdams DP. The psychology of life stories. Rev Gen Psychol. (2001) 5:100–22. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.100

7. Habermas T, de Silveira C. The development of global coherence in life narratives across adolescence: Temporal, causal, and thematic aspects. Dev Psychol. (2008) 44:707–21. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.707

8. Habermas T, Bluck S. Getting a life: The emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychol Bull. (2000) 126:748–69. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748

9. Berntsen D, Rubin DC. Cultural life scripts structure recall from autobiographical memory. Mem Cogn. (2004) 32:427–42. doi: 10.3758/bf03195836

10. Lind M, Adler JM, Clark LA. Narrative identity and personality disorder: an empirical and conceptual review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2020) 22:1-11. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01187-8

11. Adler JM, Chin ED, Kolisetty AP, Oltmanns TF. The distinguishing characteristics of narrative identity in adults with features of borderline personality disorder: An empirical investigation. J Personal Disord. (2012) 26:498–512. doi: 10.1521/pedi .2012.26.4.498

12. Jørgensen CR, Berntsen D, Bech M, Kjølbye M, Bennedsen BE, Ramsgaard SB. Identity-related autobiographical memories and cultural life scripts in patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Consciou Cogn. (2012) 21:788–98. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2012.01.010

13. Rasmussen AS, Jørgensen CR, O'Connor M, Bennedsen BE, Godt KD, Bøye R, et al. The structure of past and future events in borderline personality disorder, eating disorder, and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychol Conscious. (2017) 4:190–210. doi: 10.1037/cns0000109

14. Lind M, Vanwoerden S, Penner F, Sharp C. Inpatient adolescents with borderline personality disorder features: Identity diffusion and narrative incoherence. Pers Disord. (2019) 10:389–93. doi: 10.1037/per0000338

15. Lind M, Jørgensen CR, Heinskou T, Simonsen S, Bøye R, Thomsen DK. Patients with borderline personality disorder show increased agency in life stories after 12 months of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy. (2019) 56:274. doi: 10.1037/pst0000184

16. Lind M, Thomsen DK, Bøye R, Heinskou T, Simonsen S, Jørgensen CR. Personal and parents' life stories in patients with borderline personality disorder. Scand J Psychol. (2019) 60:231–42. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12529

17. Kernberg OF. Identity: recent findings and clinical implications. Psychoanal Q. (2006) 75:969–1004. doi: 10.1002/j.2167-4086.2006.tb00065.x

19. Habermas T. A model of psychopathological distortions of autobiographical memory narratives: an emotion narrative view. In: Watson LA, Berntsen D, editors., Clinical Perspectives on Autobiographical Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (2015). p. 267–290.

20. Levy KN, Meehan KB, Kelly KM, Reynoso JS, Weber M, Clarkin JF, et al. Change in attachment patterns and reflective function in a randomized control trial of transference-focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2006) 74:1027. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1027

21. Bach B, Simonsen S. How does level of personality functioning inform clinical management and treatment? Implications for ICD-11 classifications of personality disorder severity. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2021) 34:54–63. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000658

22. Becker DF, Grilo CM, Edell WS, McGlashan TH. Diagnostic efficiency of borderline personality disorder criteria in hospitalized adolescents: Comparison with hospitalized adults. Am J Psychiatry. (2002) 159:2042–2047. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2042

23. Westen D, Betan E, Defife JA. Identity disturbance in adolescence: Associations with borderline personality disorder. Dev Psychopathol. (2011) 23:305–13. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000817

24. Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, et al. The p factor. Clin Psychol Sci. (2014) 2:119–37. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497473

25. McAdams DP. The LSI. Evanston, IL: The Foley Center for the Study of Lives, Northwestern University. (2008). Available online at: http://www.sesp.northwestern.edu/foley/instruments/interview/

26. Hopwood CJ. Interpersonal dynamics in personality and personality disorders. Eur J Pers. (2018) 32:499–524. doi: 10.1002/per.2155

27. Bender DS, Skodol A, First MB, Oldham J. Module I: structured clinical interview for the level of personality functioning scale. In: First M, Skodol A, Bender D, and Oldham J, editors. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-5 Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (SCID-AMPD). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association (2018).

28. Cruitt PJ, Boudreaux MJ, King HR, Oltmanns JR, Oltmanns TF. Examining criterion a: DSM−5 level of personality functioning as assessed through life story interviews. Pers Disord. (2019) 10:224. doi: 10.1037/per0000321

29. Roche MJ, Jacobson NC, Phillips JJ. Expanding the validity of the Level of Personality Functioning Scale observer report and self-report versions across psychodynamic and interpersonal paradigms. J Pers Assess. (2018) 100:571–80. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2018.1475394

30. Lysaker P, Buck K, Hamm JA. Metacognition Assessment Scale: A brief overview and coding manual for the abbreviated version. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University School of Medicine. (2011).

31. Thomsen DK, Pillemer DB. I know my story and I know your story: Developing a conceptual framework for vicarious life stories. J Pers. (2017) 85:464–80. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12253

32. Adler JM. Living into the story: Agency and coherence in a longitudinal study of narrative identity development and mental health over the course of psychotherapy. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2012) 102:367–89. doi: 10.1037/a0025289

33. Singer JA. Repetition is the scent of the hunt: A clinician's application of narrative identity to a longitudinal life study. Qual Psychol. (2019) 6:194–205. doi: 10.1037/qup0000149

34. Singer JA, Bonalume L. Autobiographical memory narratives in psychotherapy: A coding system applied to the case of Cynthia. Pragm Case Stud Psychother. (2010) 6:134–88. doi: 10.14713/pcsp.v6i3.1041

35. Angus LE, McLeod J editors. The Handbook of Narrative and Psychotherapy: Practice, Theory and Research. Sage. (2004).

36. Fonagy P, Allison E. The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy. (2014) 51:372. doi: 10.1037/a0036505

37. Kernberg OF. Object relations Theory and Clinical Psychoanalysis. New York, NY: Jason Aronson (1976).

38. Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. J Pers Disord. (2004) 18:36–51. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.1.36.32772

Keywords: ICD-11, narrative identity, autobiographical reasoning, personality disorder, treatment

Citation: Lind M (2021) ICD-11 Personality Disorder: The Indispensable Turn to Narrative Identity. Front. Psychiatry 12:642696. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.642696

Received: 16 December 2020; Accepted: 25 January 2021;

Published: 18 February 2021.

Edited by:

Bo Bach, Psychiatry Region Zealand, DenmarkReviewed by:

Tilmann Habermas, Goethe University Frankfurt, GermanyJefferson Singer, Connecticut College, United States

Copyright © 2021 Lind. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Majse Lind, bWxpbmRAdWZsLmVkdQ==

Majse Lind

Majse Lind