94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry, 22 June 2021

Sec. Aging Psychiatry

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.641278

This article is part of the Research TopicCognitive Impairment and Inflammation in Old Age and the Role of Modifiable Risk Factors of Neurocognitive Disorders View all 6 articles

Objectives: There are relatively few studies on mechanisms of cognitive deficits in late-life schizophrenia (LLS). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), as an important neuroplastic molecule, has been reported to be involved in neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia. This study aimed to examine whether peripheral BDNF levels were associated with cognitive deficits in LLS, which has not been explored yet.

Methods: Forty-eight LLS patients and 45 age-matched elderly controls were recruited. We measured all participants on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) for cognition and serum BDNF levels. Psychopathological symptoms in patients were assessed by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

Results: The levels of BDNF in LLS patients were significantly lower than those in healthy controls (8.80 ± 2.30 vs. 12.63 ± 5.08 ng/ml, p < 0.001). The cognitive performance of LLS patients was worse than that of the controls on RBANS total score and scores of immediate memory, attention, language, and delayed memory (all p ≤ 0.005). BDNF was positively associated with attention in LLS patients (r = 0.338, p = 0.019).

Conclusion: Our findings suggest that older patients with schizophrenia exhibit lower BDNF levels and more cognitive deficits than older controls, supporting the accelerated aging hypothesis of schizophrenia. Moreover, decreased BDNF is related to attention deficits, indicating that BDNF might be a candidate biomarker of cognitive impairments in LLS patients.

As the aging of the population has become a global trend, the number of older people with mental illness has increased significantly. Notably, late-life schizophrenia (LLS) accounts for the largest proportion of care expenditures for elderly patients with mental illness or other non-psychiatric disorders (including dementia), making it a major public health problem (1, 2). Nevertheless, the aging problem of schizophrenia has been ignored, especially on cognitive impairment (the core features of both schizophrenia and aging), and its pathophysiological mechanisms.

Cognitive deficits have been recognized as a core feature of schizophrenia for the past few decades, and research has surged in the last decade. Patients with schizophrenia suffer various degrees of cognitive impairment in a range of domains, such as processing speed, verbal memory, working memory, attention, executive functions, and visual memory (3, 4). Extensive cognitive impairments have seriously affected social ability, vocational rehabilitation, and independent life, leading to a poor prognosis for schizophrenia (5–7). Throughout the lifespan, cognition strongly predicts the functional capacity of schizophrenia independent of age (8). Concerning senile schizophrenia, significant cognitive impairments were generally reported compared with elderly healthy controls (9). Several meta-analyses showed moderate to large effect sizes across multiple cognitive domains (9–11), of which executive function, verbal fluency, and memory impairments were the most consistent. Although the cognitive decline in LLS patients has been well-documented, its underlying etiology and pathogenesis are still inconclusive.

Not yet been investigated, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may be involved in cognitive impairments of LLS. As a major member in the neurotrophin, BDNF plays a critical role not only in neurodevelopment and neuroprotection but also in synaptic plasticity, learning, and a variety of cognitive functions (12). Substantial evidence in animal studies showed that the up-regulation of BDNF signaling pathway or endogenous BDNF levels promoted neural development and memory capability (13, 14), while inhibition of BDNF signaling interfered with learning and long-term memory formation (15). It is consistent with clinical findings in human studies. Decreased peripheral BDNF levels have been widely demonstrated in both medicated and drug-naive first-episode patients with schizophrenia, potentially contributing to their cognitive impairments, revealed by recent meta-analyses (16–19). Lower BDNF levels predicted worse performance in many cognitive measurements, including attention, perceptual-motor skills, processing speed, and memory. Our study found that higher levels of BDNF corresponded to better performance on immediate memory (20). Based on findings in animal studies and adult schizophrenia, it is speculated that in LLS patients, cognitive performance is at least partially associated with peripheral BDNF levels. Yet so far, the relationship between peripheral BDNF levels and cognition in patients with LLS has not been explored (21), either which specific domains of cognitive deficits would be correlated with altered BDNF levels if any.

In this study, we examined serum BDNF levels and cognitive function in LLS patients to determine (1) whether the cognitive performance of LLS patients would be worse than that of healthy elderly; (2) whether the levels of BDNF in LLS patients would be lower than that of healthy elderly; and (3) whether there would be a correlation between BDNF and neurocognitive function of LLS patients.

Inpatients with geriatric schizophrenia were recruited from two public psychiatric hospitals in China, including Hui-Long-Guan hospital in Beijing and Rong-Jun hospital in Hebei province. All patients met the DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia and had no other psychiatric disorders. Their diagnosis was confirmed by two independent experienced psychiatrists according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). A total of 48 chronic patients over 60 years of age (average age: 63.77 ± 2.94 years) were enrolled, of which 38 were men and 10 women. The average age of the first onset was 26.85 ± 6.07 years. Before participating in this study, all patients had been receiving stable antipsychotic medication for at least 6 months, with an average dose (in chlorpromazine equivalents) of 325.25 ± 159.59 mg/day. Antipsychotic drugs included clozapine (n = 17), risperidone (n = 17), perphenazine (n = 5), pipotiazine (n = 3), haloperidol (n = 2), sulpiride (n = 2), chlorpromazine (n = 1), and aripiprazole (n = 1). The average duration of treatment with the current medication was 42.72 ± 44.53 months.

Forty-five age-matched healthy controls were recruited from the local community in Beijing and they aged over 60 years, with an average age of 63.77 ± 2.94 years, including 27 men and 18 women. Current mental and physical conditions were assessed through structured clinical interviews according to the DSM-IV by psychiatrists. None of them suffered from mental disorders or neurodegenerative diseases.

A detailed demographic questionnaire was conducted for each participant, recording general information, smoking behavior, socio-demographic characteristics, and medical and psychiatric history. Medical records and collateral resources were also used to collect additional information. All participants were determined to be free of substance abuse or severe physical diseases. All of the participants signed a written informed consent form before participating in this study. The research protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Hui-Long-Guan hospital.

The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) (22) was used to assess the neurocognitive function of each participant. RBANS consists of five domains of cognition assessed with twelve subtests: immediate memory (List Learning and Story Memory), visuospatial/constructional ability (Figure copy and Line Orientation), language (Picture Naming and semantic fluency), attention (Forward Digit Span and Coding), and delayed memory (List Recall, List Recognition, Story Recall, and Figure Recall). Thus, five index scores and a total score were given to each participant according to the normative data.

The psychopathological symptoms of each patient were assessed by four independent psychiatrists by using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (23), including a total score and scores of three subscales: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and general psychopathology. To ensure the consistency of the rating scores, the psychiatrists attended the same training course in the use of PANSS. For repeated evaluation of the PANSS total score, the inter-rater correlation coefficient was >0.8.

Venous blood (10 ml) was collected into a non-anticoagulant tube between 7 and 9 a.m. after overnight fasting. After coagulation at room temperature, the serum was separated by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min and then stored at −70 °C until assay.

The serum BDNF levels were measured within 1 month by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a commercially available kit, according to the standard protocol (RayBio® Human BDNF ELISA kit). Standard 96-well-plates were coated with the mouse monoclonal anti-BDNF immunoglobulin and incubated overnight. After washing, the samples and standards (concentration 0.1–256 ng/well) were incubated overnight. The plates were then washed three times with washing buffer, followed by incubation with chick anti-BDNF overnight. After three washes, a 1:1,000 dilution of peroxidase-labeled anti-chick antibody was added. After further washing, the reaction was developed at room temperature with tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) and stopped with phosphoric acid. Absorbencies were measured by a microtiter plate reader (absorbency at 450 nm).

Each evaluated parameter was assayed in duplicate for all samples. All samples were assayed by a technician who was blind to the clinical status of each subject. The identity of all subjects was indicated by a code number maintained by the investigator until all biochemical analyses were completed. Inter- and intra-assay variation coefficients were 8 and 5%, respectively.

The demographic variables of LLS and healthy elderly groups were compared with student's t-tests (continuous variables) and chi-squared tests (categorical variables). The levels of BDNF showed a normal distribution by Kolmogorov–Smirnov one-sample test (p > 0.05). We used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to compare the differences in BDNF and cognitive performance on RBANS between LLS patients and elderly controls, with demographic variables that showing significant between-group differences (i.e., sex, education, marital status) as covariates. The relationship between variables was examined by Pearson's correlation coefficients. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple testing. Further, we used multivariate regression analyses (enter regression model) to examine the relationship between cognitive function (RBANS) and BDNF while controlling the demographic and clinical variables including antipsychotic treatment (type, dose, and duration of treatment) and clinical symptoms on PANSS.

We utilized SPSS (version 24.0) to carry out all statistical analyses and set the significance level α at 0.05 and p-value to two-tailed.

The demographic characteristics of LLS patients and healthy elderly controls are summarized in Table 1. There were significant differences in sex, education, and marital status (all p < 0.05) between the two groups, but without significant differences in age, BMI, and smoking status. In the following analyses, sex, education, and marital status were adjusted.

Serum BDNF levels were significantly lower in LLS patients than that in healthy elderly (8.80 ± 2.30 vs. 12.63 ± 5.08 ng/ml, F = 22.30, df = 1, p < 0.001). The difference in BDNF levels between the two groups remained significant after adjusting for sex, marital status, and education as covariates (F = 21.72, df = 1, p < 0.001).

BDNF serum levels were not associated with any demographic variables in either the control group or the LLS group (all p > 0.05). In the LLS patient group, BDNF levels were not related to the age of onset, duration of disease, and type and dosage of antipsychotic treatment (all p > 0.05). Correlation analysis revealed that there were no significant correlations between serum BDNF levels and PANSS positive symptom, negative symptom, and general psychopathology subscale and total scores in LLS patients (all p > 0.05).

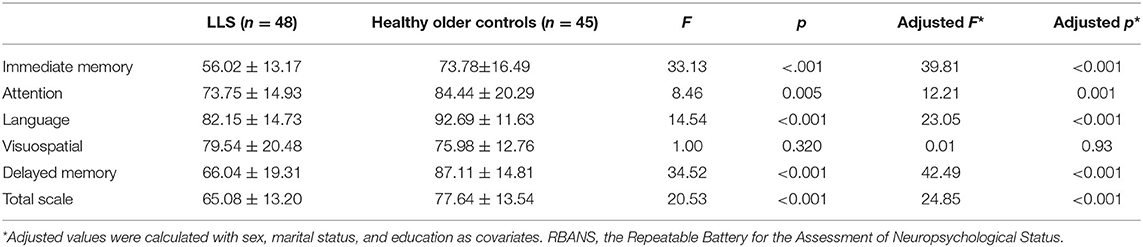

Table 2 displays the RBANS performance of LLS patients and healthy controls. Expect for visuospatial/constructive domain, LLS patients exhibited poorer cognitive performance in terms of immediate memory, attention, language, delayed memory, and total scores of RBANS compared to healthy elderly controls. After adjusting for sex, marital status, and education, these differences remained significant (all p < 0.05). In the LLS group, PANSS negative symptom was negatively associated with all RBANS total and domain scores (all p < 0.05), except for the visuospatial/constructional index.

Table 2. Total and each index scores on the RBANS in late-life schizophrenia (LLS) vs. healthy older controls.

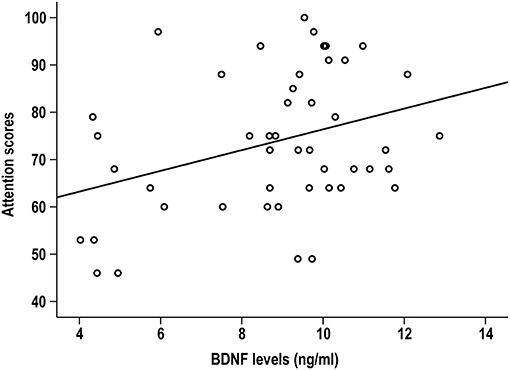

In LLS patients, BDNF levels were positively correlated with attention index (r = 0.338, p = 0.019, Figure 1). Partial correlation analysis further confirmed this significant association by controlling for sex, marital status, and education (r = 0.371, p = 0.013). However, the association did not survive Bonferroni correction (p > 0.05/5). There was no significant association between BDNF and other cognitive indexes (all p > 0.05). Serum BDNF levels were not associated with any RBANS scores in healthy elderly controls (all p > 0.05).

Figure 1. Serum BDNF was positively associated with the attention index in patients with late-life schizophrenia (r = 0.338, p = 0.019).

Further, multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to explain the contribution of BDNF, demographic and clinical variables, and antipsychotic treatment to the attention index of LLS patients. The results showed that BDNF levels (β = 0.27, t = 2.10, p = 0.042), antipsychotic type (β = 0.27, t = 2.08, p = 0.045), and years of education (β = 0.39, t = 3.10, p = 0.004) were independent contributors to attention index. Together they could explain the 42% variation in attention index. BDNF was not correlated to other RBANS domain and total scores.

To our best knowledge, this is the first study to explore the peripheral BDNF level and its relationship with cognitive function in late-stage schizophrenia. There were three main findings in this study: (1) compared with age-matched healthy elderly, serum BDNF levels were significantly lower in LLS patients; (2) LLS patients displayed extensive cognitive impairments in all RBANS total and domain scores except for visuospatial/constructional domain; (3) BDNF levels were associated with attention in LLS patients.

We found that LLS patients had severe and pervasive cognitive deficits compared with healthy elderly controls. This is consistent with most previous studies evaluating the various cognitive performance of LLS patients (9, 10). Also, study in our lab (24) found cognitive impairments in younger populations with schizophrenia in global cognition and multiple domains, i.e., language, executive function, and memory, measured by the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB), suggesting that schizophrenia have widespread cognitive impairments without categorical differences in both adulthood and late-life stages.

Our finding of lower BDNF serum levels in LLS patients compared with the aged-matched cohort, extended previous findings in younger and middle-aged schizophrenia (16, 25–29). Regarding BDNF levels of patients with LLS, a few studies with rare samples assayed BDNF in post-mortem brain tissue (30–33). These studies demonstrated that BDNF levels and protein levels of calbindin-D and TrkB receptors, which were up-regulated by BDNF, were significantly reduced in the hippocampus or pre-frontal cortex. This study examining the levels of BDNF in the blood in vivo for geriatric patients with schizophrenia indicated a reduction of blood BDNF persists with age and also provided evidence for the association between blood and brain BDNF levels. Taking together evidence in vitro and post-mortem studies, BDNF may be involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia at all ages.

Decreased BDNF and cognition in LLS patients verified the accelerated aging hypothesis of schizophrenia (34), which suggests that schizophrenia is a syndrome of accelerated aging, because patients exhibit signs of deterioration, including physical illness, cognitive decline, metabolic problems, and shortened life expectancy, similar to the aging process but at an accelerated rate. Parallel with this hypothesis, a recent study using neuroimaging technology and machine learning demonstrated that mental illness accelerated normal brain maturation, resulting in an older estimated brain age in schizophrenia patients than in healthy controls (35). Moreover, at the behavioral level, cognitive performance and daily functional skills of patients with schizophrenia were as poor as those of healthy individuals who were three decades older (36). Consistently, our results show that BDNF and cognition were lower in LLS patients than those of age-matched healthy elderly, which may be the sign of premature aging. Nevertheless, the underlying neurobiological connections and interactions between aging and schizophrenia are uncertain and need further investigation. Further longitudinal studies on patients of different ages can provide more detailed explanations.

Another important finding is that cognitive performance (i.e., attention), rather than psychotic symptoms, was positively associated with serum BDNF levels in LLS patients. As a molecular marker of neuroplasticity, BDNF plays a key role in regulating synaptic structure and function. In animal models, as the essential mechanisms of learning and memory, long-term potentiation (LTP) was impaired in BDNF-knockout mice (37, 38) and could be rescued by acute infusion of BDNF (14). In adult mice, hippocampus-specific deletions of the BDNF gene resulted in impaired object recognition and spatial learning in the Morris water maze (39). It is worthy of mentioning that although in our study, we assessed BDNF levels in the blood rather than in the central nervous system, the BDNF concentrations in the blood reflected brain-tissue BDNF levels across species (40–42). Indeed, it is generally recognized that blood BDNF levels were associated with cognitive function as well. For instance, BDNF serum levels were significantly reduced in almost all cognitively-impaired groups, such as mild cognitive impairment (43), Alzheimer's disease (44), and Parkinson's disease (45). Similarly, our results together with previous studies, verified that in patients with schizophrenia, cognitive impairments were always accompanied by lower blood BDNF levels (19, 20). Besides, some studies proposed the neurotrophin hypothesis of schizophrenia, which suggested that changes in neurotrophic factors resulted in disturbed processes of neuroplasticity and neural maldevelopment, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of schizophrenia (46). However, we did not find a significant correlation between BDNF levels and the severity of positive or negative symptoms, which were in agreement with some previous studies (17), suggesting that low BDNF levels may have a small and insignificant relationship with the psychopathology of schizophrenia, or it may be just a pathological epiphenomenon of schizophrenia.

Interestingly, we found that decreased BDNF levels were only associated with greater severity of attention deficits. One possible explanation is that attention is more susceptible to lower BDNF interference than other cognitive domains. Several lines of evidence from patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) indicated that decreased midbrain BDNF activity might be implicated in the pathogenesis of attention deficits, while pharmacotherapy for ADHD upregulated BDNF expression in the brain (47, 48). Other domains of cognitive function, such as memory, were affected by more factors in addition to BDNF, such as up-regulated inflammatory factors, Aβ amyloid deposition, and microtubule-associated tau protein pathology. In addition, it is important to consider that in RBANS, attention ability was measured by the digit span test, which was also a traditional psychology test for working memory (24, 49). In this task, information was required to be stored in immediate memory and reproduced later. Thus, we speculated that serum BDNF levels were related to working memory deficits in schizophrenia.

This study has several limitations. First, a long period of illness may lead to hospitalization, sedentary lifestyle, chronic antipsychotic treatment, comorbid depression, and anxiety. These confounding factors may partly account for the differences in BDNF and cognitive function between the patient group and the control group. Unfortunately, we did not collect all the confounders to control for their possible effects on BDNF levels and cognition. Therefore, caution should be taken in interpreting these results. Second, we did not conduct cognitive screening by neuropsychological tests. Dementia was ruled out only by the structured clinical review and psychiatric evaluation based on DSM-IV. As a result, LLS may have mild cognitive impairment. Third, due to the cross-sectional design, this study could not reveal the causal relationship between decreased BDNF and cognitive impairment in geriatric schizophrenia patients. Fourth, our results were preliminary with relatively small sample size, and further validation will be conducted in an expanded sample of LLS patients to draw a firm conclusion. Fifth, there are some limitations regarding the assays of BDNF. Although platelets are the major source of peripheral BDNF, we did not analyze the BDNF level in the framework of platelet counts. In the future, it would be interesting to investigate the relationship between BDNF levels in platelets and cognitive functions. In addition, there may be some differences in performance of commercial BDNF assays, as recently demonstrated by Polacchini et al. (50). As a result, although we have conducted the BDNF assays strictly following the manual, it should be cautious to compare our results with the published blood-derived BDNF data.

In conclusion, our study is the first step in characterizing reduced peripheral BDNF levels and large-scale cognitive deficits in older schizophrenia, supporting the accelerated aging hypothesis of schizophrenia. Also, we revealed that decreased BDNF levels are linked to attention deficits but not psychotic symptoms of LLS patients, indicating that BDNF might be a reliable biomarker of cognitive function. Further biological and longitudinal studies with larger samples are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanism underlying the association between low BDNF serum levels and cognitive deficits in LLS patients, and how aging and schizophrenia interact in cognitive changes.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Hui-Long-Guan hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

LH, YN, and XZ were responsible for study design and data analysis. FW and XL were responsible for data acquirement. LH, ZZ, YN, and XZ drafted the manuscript. All the authors critically reviewed the manuscript and gave final approval for its publication.

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Plan Project of Guangdong Province (Grant no. 2019B030316001), Guangzhou Municipal Psychiatric Disease Clinical Transformation Laboratory, Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (Grant nos. 201805010009 and 20807010064), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant no. 2020089).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Bartels SJ, Clark RE, Peacock WJ, Dums AR, Pratt SI. Medicare and medicaid costs for schizophrenia patients by age cohort compared with costs for depression, dementia, and medically ill patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2003) 11:648–57. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200311000-00009

2. Cohen CI, Meesters PD, Zhao J. New perspectives on schizophrenia in later life: implications for treatment, policy, and research. Lancet Psychiatry. (2015) 2:340–50. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00003-6

3. Barch DM, Sheffield JM. Cognitive impairments in psychotic disorders: common mechanisms and measurement. World Psychiatry. (2014) 13:224–32. doi: 10.1002/wps.20145

4. Fatouros-Bergman H, Cervenka S, Flyckt L, Edman G, Farde L. Meta-analysis of cognitive performance in drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2014) 158:156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.06.034

5. González-Blanch C, Perez-Iglesias R, Pardo-García G, Rodríguez-Sánchez JM, Martínez-García O, Vázquez-Barquero JL, et al. Prognostic value of cognitive functioning for global functional recovery in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychol Med. (2010) 40:935–44. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991267

6. Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, Green MF, Ventura J, Asarnow RF, Gitlin MJ, et al. Neurocognitive predictors of work outcome in recent-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2011) 37 (Suppl. 2):S33–40. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr084

7. Rajji TK, Miranda D, Mulsant BH. Cognition, function, and disability in patients with schizophrenia: a review of longitudinal studies. Can J Psychiatry. (2014) 59:13–7. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900104

8. Kalache SM, Mulsant BH, Davies SJ, Liu AY, Voineskos AN, Butters MA, et al. The impact of aging, cognition, and symptoms on functional competence in individuals with schizophrenia across the lifespan. Schizophr Bull. (2015) 41:374–81. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu114

9. Rajji TK, Mulsant BH. Nature and course of cognitive function in late-life schizophrenia: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. (2008) 102:122–40. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.03.015

10. Irani F, Kalkstein S, Moberg EA, Moberg PJ. Neuropsychological performance in older patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Schizophr Bull. (2011) 37:1318–26. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq057

11. Meesters PD, Schouws S, Stek M, de Haan L, Smit J, Eikelenboom P, et al. Cognitive impairment in late life schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2013) 28:82–90. doi: 10.1002/gps.3793

12. Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Medina JH. Reviews: BDNF and memory formation and storage. Neuroscientist. (2008) 14:147–56. doi: 10.1177/1073858407305850

13. Chen Y, Zheng Z, Zhu X, Shi Y, Tian D, Zhao F, et al. Lactoferrin promotes early neurodevelopment and cognition in postnatal piglets by upregulating the BDNF signaling pathway and polysialylation. Mol Neurobiol. (2015) 52:256–69. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8856-9

14. Simmons DA, Rex CS, Palmer L, Pandyarajan V, Fedulov V, Gall CM, et al. Up-regulating BDNF with an ampakine rescues synaptic plasticity and memory in Huntington's disease knockin mice. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. (2009) 106:4906–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811228106

15. Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Medina JH. BDNF and memory processing. Neuropharmacology. (2014) 76:677–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.024

16. Green MJ, Matheson SL, Shepherd A, Weickert CS, Carr VJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in schizophrenia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. (2011) 16:960–72. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.88

17. Fernandes BS, Steiner J, Berk M, Molendijk ML, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Turck CW, et al. Peripheral brain-derived neurotrophic factor in schizophrenia and the role of antipsychotics: meta-analysis and implications. Mol Psychiatry. (2014) 20:1108–19. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.117

18. Qin XY, Wu HT, Cao C, Loh YP, Cheng Y. A meta-analysis of peripheral blood nerve growth factor levels in patients with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. (2017) 22:1306–12. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.235

19. Ahmed AO, Mantini AM, Fridberg DJ, Buckley PF. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and neurocognitive deficits in people with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2015) 226:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.12.069

20. Zhang XY, Liang J, Xiu MH, De Yang F, Kosten TA, Kosten TR. Low BDNF is associated with cognitive impairment in chronic patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology. (2012) 222:277–84. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2643-y

21. Islam F, Mulsant BH, Voineskos AN, Rajji TK. Brain-Derived neurotrophic factor expression in individuals with schizophrenia and healthy aging: testing the accelerated aging hypothesis of schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2017) 19:36. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0794-6

22. Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. (1998) 20:310–9. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823

23. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (1987) 13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261

24. Wu JQ, Chen DC, Tan YL, Xiu MH, De Yang F, Soares JC, et al. Cognitive impairments in first-episode drug-naive and chronic medicated schizophrenia: MATRICS consensus cognitive battery in a Chinese Han population. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 238:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.042

25. Chiou YJ, Huang TL. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factors in Taiwanese patients with drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia: effects of antipsychotics. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2017) 18:382–91. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2016.1224925

26. Cui H, Jin Y, Wang J, Weng X, Li C. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. (2012) 24:250–61. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2012.05.002

27. Grillo RW, Ottoni GL, Leke R, Souza DO, Portela LV, Lara DR. Reduced serum BDNF levels in schizophrenic patients on clozapine or typical antipsychotics. J Psychiatr Res. (2007) 41:31–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.01.005

28. Rizos EN, Papadopoulou A, Laskos E, Michalopoulou PG, Kastania A, Vasilopoulos D, et al. Reduced serum BDNF levels in patients with chronic schizophrenic disorder in relapse, who were treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2010) 11:251–5. doi: 10.3109/15622970802182733

29. Sotiropoulou M, Mantas C, Bozidis P, Marselos M, Mavreas V, Hyphantis T, et al. BDNF serum concentrations in first psychotic episode drug-naïve schizophrenic patients: associations with personality and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism. Life Sci. (2013) 92:305–10. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.01.008

30. Durany N, Michel T, Zöchling R, Boissl KW, Cruz-Sánchez FF, Riederer P, et al. 2001 Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin 3 in schizophrenic psychoses. Schizophr Res. (2001) 52:79–86. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(00)00084-0

31. Iritani S, Niizato K, Nawa H, Ikeda K, Emson PC. Immunohistochemical study of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor, TrkB, in the hippocampal formation of schizophrenic brains. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2003) 27:801–7. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00112-X

32. Issa G, Wilson C, Terry AV, Pillai A. An inverse relationship between cortisol and BDNF levels in schizophrenia: data from human postmortem and animal studies. Neurobiol Dis. (2010) 39:327–33. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.04.017

33. Takahashi M, Shirakawa O, Toyooka K, Kitamura N, Hashimoto T, Maeda K, et al. Abnormal expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor in the corticolimbic system of schizophrenic patients. Mol Psychiatry. (2000) 5:293–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000718

34. Kirkpatrick B, Messias E, Harvey PD, Fernandez-Egea E, Bowie CR. Is schizophrenia a syndrome of accelerated aging? Schizophr Bull. (2008) 34:1024–32. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm140

35. Koutsouleris N, Davatzikos C, Borgwardt S, Gaser C, Bottlender R, Frodl T, et al. Accelerated brain aging in schizophrenia and beyond: a neuroanatomical marker of psychiatric disorders. Schizophr Bull. (2014) 40:1140–53. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt142

36. Harvey PD, Rosenthal JB. Cognitive and functional deficits in people with schizophrenia: evidence for accelerated or exaggerated aging? Schizophr Res. (2018) 196:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.05.009

37. Abidin I, Köhler T, Weiler E, Zoidl G, Eysel UT, Lessmann V, et al. 2006 Reduced presynaptic efficiency of excitatory synaptic transmission impairs LTP in the visual cortex of BDNF-heterozygous mice. Eur J Neurosci. (2006) 24:3519–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05242.x

38. Schildt S, Endres T, Lessmann V, Edelmann E. Acute and chronic interference with BDNF/TrkB-signaling impair LTP selectively at mossy fiber synapses in the CA3 region of mouse hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. (2013) 71:247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.041

39. Heldt S, Stanek L, Chhatwal J, Ressler K. Hippocampus-specific deletion of BDNF in adult mice impairs spatial memory and extinction of aversive memories. Mol Psychiatry. (2007) 12:656–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001957

40. Klein AB, Williamson R, Santini MA, Clemmensen C, Ettrup A, Rios M, et al. Blood BDNF concentrations reflect brain-tissue BDNF levels across species. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. (2011) 14:347–53. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710000738

41. Lang UE, Hellweg R, Seifert F, Schubert F, Gallinat J. Correlation between serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor level and an in vivo marker of cortical integrity. Biol Psychiatry. (2007) 62:530–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.002

42. Sartorius A, Hellweg R, Litzke J, Vogt M, Dormann C, Vollmayr B, et al. Correlations and discrepancies between serum and brain tissue levels of neurotrophins after electroconvulsive treatment in rats. Pharmacopsychiatry. (2009) 42:270–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1224162

43. Shimada H, Makizako H, Doi T, Yoshida D, Tsutsumimoto K, Anan Y, et al. A large, cross-sectional observational study of serum BDNF, cognitive function, and mild cognitive impairment in the elderly. Front Aging Neurosci. (2014) 6:69. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00069

44. Budni J, Bellettini-Santos T, Mina F, Garcez ML, Zugno AI. The involvement of BDNF, NGF and GDNF in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Aging Dis. (2015) 6:331–41. doi: 10.14336/AD.2015.0825

45. Wang Y, Liu H, Zhang B-S, Soares JC, Zhang XY. Low BDNF is associated with cognitive impairments in patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2016) 29:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.05.023

46. Durany N, Thome J. Neurotrophic factors and the pathophysiology of schizophrenic psychoses. Eur Psychiatry. (2004) 19:326–37. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.06.020

47. Tsai SJ. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a speculative hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. (2003) 60:849–51. doi: 10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00052-5

48. Tsai SJ. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder may be associated with decreased central brain-derived neurotrophic factor activity: clinical and therapeutic implications. Med Hypotheses. (2007) 68:896–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.06.025

49. Conklin HM, Curtis CE, Katsanis J, Iacono WG. Verbal working memory impairment in schizophrenia patients and their first-degree relatives: evidence from the digit span task. Am J Psychiatry. (2000) 157:275–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.275

Keywords: brain-derived neurotrophic factor, late-life schizophrenia, serum, cognitive deficits, attention

Citation: Huo L, Zheng Z, Lu X, Wu F, Ning Y and Zhang XY (2021) Decreased Peripheral BDNF Levels and Cognitive Impairment in Late-Life Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 12:641278. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.641278

Received: 14 December 2020; Accepted: 14 May 2021;

Published: 22 June 2021.

Edited by:

Erico Castro-Costa, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), BrazilReviewed by:

Swapnajeet Sahoo, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), IndiaCopyright © 2021 Huo, Zheng, Lu, Wu, Ning and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiang Yang Zhang, emhhbmd4eUBwc3ljaC5hYy5jbg==; Yuping Ning, bmluZ2plbnlAMTI2LmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.