95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 30 March 2021

Sec. Schizophrenia

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.637789

This article is part of the Research Topic Understanding Early Detection Markers in Schizophrenia View all 9 articles

Background: Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder, which has a major impact on the quality of life and imposes a huge burden on the family. However, the pathogenesis of schizophrenia remains unclear and there are no specific biomarkers. Therefore, we intend to explore whether cf-DNA levels are related to the occurrence and development of schizophrenia.

Methods: We analyzed and compared the concentration of cf-DNA in 174 SZ patients and 100 matched healthy controls by using quantitative real-time PCR by amplifying the Alu repeats.

Results: We found that cf-DNA levels in peripheral blood reliably distinguished SZ patients from healthy controls (P < 0.05). The ROC analysis also supports the above conclusion. By tracking the absolute concentration of serum cf-DNA in primary cases, we found a distinct increase before treatment with antipsychotics, which decreased progressively after treatment.

Conclusions: The present work indicates that cf-DNA may improve the efficiency of disease diagnosis, and the level of cf-DNA plays a predictive role in the development of schizophrenia. By evaluating the level of cf-DNA, we might play a certain role in a more reasonable and standardized clinical treatment of schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a major public problem that impairs brain function and affects approximately 1% of the world population (1–3). Different from many other diseases, the exact etiology and pathogenesis of SZ remains elusive. Diagnoses are still determined by the medical history together with the mental symptoms and disease progression. To date, no definite laboratory examination or laboratory test has been demonstrated to support an accurate clinical diagnosis. Such diagnoses are subject to subjective factors and higher requirements for doctor's clinical experience. As potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets have yet to be established (4), the development of biomarkers to improve diagnosis and prognosis is an urgent task.

In the past, hypotheses regarding the causes of SZ have been proposed, including abnormal neurotransmission, nerve development and generation, immune system disorders and neuronal apoptosis (5). Moreover, apoptosis is a physiological process of cell death and has been confirmed to be involved in the pathological process of SZ. Pro-apoptotic stimulation such as inflammation, autoimmunity, and oxidative stress may lead to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in mitochondria, affect the oxidative metabolic process, and then trigger the apoptosis of neurons and glial cells (6–8). Early studies have shown that 20–80% of neurons in the central nervous system die from apoptosis (9) and have reported the aberration of apoptotic regulatory proteins and DNA fragmentation status in the posterior temporal cortex (10, 11). These studies laid out the foundation for exploring the potential role of apoptosis in the pathogenesis of SZ.

Cf-DNA was first observed by French scientists Mandel and Metais in human plasma in 1,948 (12). Since then, many scholars have made in-depth studies on the content of cf-DNA in the blood of cancer patients (13). Alu is a cell-free DNA molecule that can be easily detected. The Alu sequence is a rich intermediate repeat sequence unique to the primate genome and is the largest family with short scattered repeat sequences with a high homology CG (70–98%). Now, it is generally believed that cf-DNA, a type of cell-free extracellular DNA, is mainly derived from apoptosis and necrosis (14–16). Using PCR, Wang (17) found that long DNA fragments associated with necrosis could be distinguished from short DNA fragments generated by physiological apoptosis. Research shows that cerebrospinal fluid cell-free mitochondrial DNA is associated with mild neurocognitive impairment (18, 19). Studies have shown that most of the factors released by activated microglia cells in SZ patients have toxic effects on neurons (20). Evidence suggests that antipsychotics exhibit neuroprotective potential (21), can inhibit inflammatory responses, combat neuronal damage, and reduce cell apoptosis and damage (22–24).

In our study, we investigated the serum level of Alu in SZ patients and explored its clinical value as a serum auxiliary biomarker for SZ. We found that the Alu content in the SZ group was significantly higher than that in the control group. Furthermore, Alu was not correlated with gender, age at onset, current age, duration of psychosis, current treatment or family history. By trcking the 57 newly diagnosed SZ patients, we found the level of Alu before treatment was higher than the level at post treatment. This study presents basic research on disease surveillance and may lay a foundation for the pathogenesis of SZ and the search for potential biomarkers.

Serum samples were collected from 174 SZ patients (the SZ group) from the Nantong Mental Health Center between December 1st 2017 and August 1st 2018. The SZ patients were divided into the following subtypes: undifferentiated (n = 132), paranoid (n = 11), acute SZ-like psychosis (n = 29), and other subtypes (n = 2). The diagnosis of SZ was based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, as well as the International classification of diseases, 10th Edition.

During the same period, 100 healthy controls (the HC group) were selected from the Physical Examination Center of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (Nantong, China) who had no history of autoimmune diseases, tissue injuries or traumas and whose hematological-biochemical profiles were normal at the time of examination. The demographic details of all the participants are shown in Table 1.

This study was approved by Nantong Forth People's Hospital ethics committee (2019 K007) and all participants signed an informed consent form.

We used the Nottingham Onset Schedule (25) to record the onset date of the psychotic symptoms and the beginning of pharmacological treatment. Pharmacological treatment duration was defined by the period (in weeks) between the beginning of pharmacological treatment and blood collection. Finally, the interval (in weeks) from the first manifestation of psychotic symptoms to blood collection defined the total duration of the metal disorder.

The age at the onset of symptoms was collected for all SZ patients. In addition, the positive and negative syndrome scale (26) was used for all participants.

Blood samples were collected in separating gel vacuum collection tubes and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min. The upper-layer supernatant was immediately stored in an RNase-free Eppendorf tube at −80°C until use. Cf-DNA was extracted from 0.2 ml of serum using the TIANLONG DNA Kit (Suzhou, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

RT-qPCR was performed with Applied Biosystems 7,500 (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). We performed experiments with absolute quantification to verify the results. The target for RT-qPCR was the consensus sequence of human Alu-interspersed repeats: a 115 bp Alu amplicon (Alu115) that represents both shorter and longer cf-DNA fragments. The diluted cf-DNA template was used with 1 × FastStart Universal SYBR GreenImaster mix (Roche, Switzerland) for RT-qPCR, which was performed by a Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, USA) at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing at 64°C for 1 min (27). The absolute level of Alu was quantified using the standard curve (from 0.222 to 22,200 ng/ml) of human genome DNA (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Mean values were calculated from triplicate reactions.

The liver function, kidney function, blood glucose, electrolytes, cardiac enzyme spectrum, and lipid profile of 174 patients were detected on an Olympus AU680 biochemical analyzer.

The concentration of Alu was depicted as the median and 25th and 75th percentiles. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software package version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Statistical significance was tested by the Mann-Whitney unpaired test analysis of variance or the Chi-square test, as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the ROC curve (AUC) were used to assess the diagnostic value. The maximum AUC area was determined by the specificity and sensitivity of the optimal cut-off point. The figures were partially drawn by GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (Graphpad Software Inc., CA, USA).

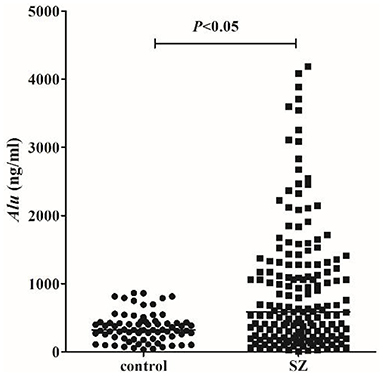

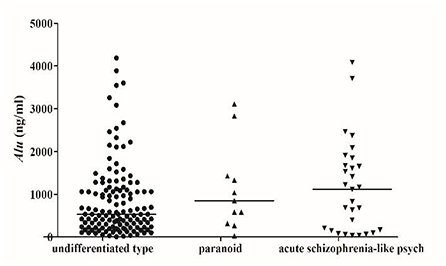

We detected Alu using RT-qPCR of 115 bp amplicons. The concentration of Alu in the SZ group [586.0 ng/ml (interquartile range: 228.4–1275.7 ng/ml)] was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than that of the HC group [318.3 ng/ml (253.5–427.4 ng/ml)] (Figure 1). The concentration of Alu exhibited no statistical differences (P > 0.05) between the different subtypes, which were as follows: undifferentiated [533.5 ng/ml (237.1–1095.9 ng/ml)], paranoid [849.9 ng/ml (450.5–1378.6 ng/ml)], and acute SZ-like psychosis [1115.3 ng/ml (167.1–1673.4 ng/ml)] (Figure 2).

Figure 1. cf-DNA levels measured by RT-qPCR. Statistical comparisons were performed using logistic analysis. When P-value <0.05, the difference was statistically significant. The horizontal line represents the median for each group.

Figure 2. Scatter plot of serum Alu from patients with different types of schizophrenia. SZ patients were divided into undifferentiated type (132), paranoid (11), acute schizophrenia-like psychosis (29), and other subtypes (2), no statistical differences between different classification groups (P > 0.05).

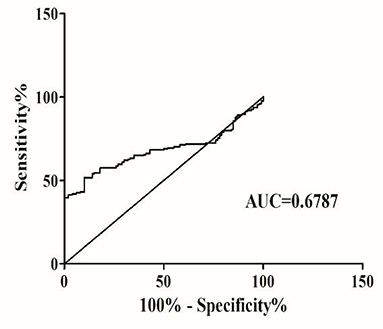

To investigate the characteristics of serum Alu as a potential marker for SZ, ROC curves were constructed on data from all participants, including 174 SZ patients and 100 healthy controls. Serum Alu effectively differentiated SZ patients from normal controls with an AUC of 0.6787, with a 95% confidence interval of 61.66–74. 08% (Figure 3). When the cut-off value was 567.1 ng/ml, the sensitivity was 51.72% and the specificity was 90%, with a 95% confidence interval of 44.04–59.35%. Based on the cut-off value of 567.1 ng/ml, the Alu level exceeds the cut-off value in 47.7% undifferentiated type (63/132), 72.7% paranoid (8/11) and 65.6% acute SZ-like psychosis (19/29).

Figure 3. The ROC analysis of Alu between SZ patients and healthy controls. RT-qPCR and ROC curve analysis for predicting cf-DNA as a SZ diagnosis biomarker. The area under the curve (AUC) value was 0.6787.

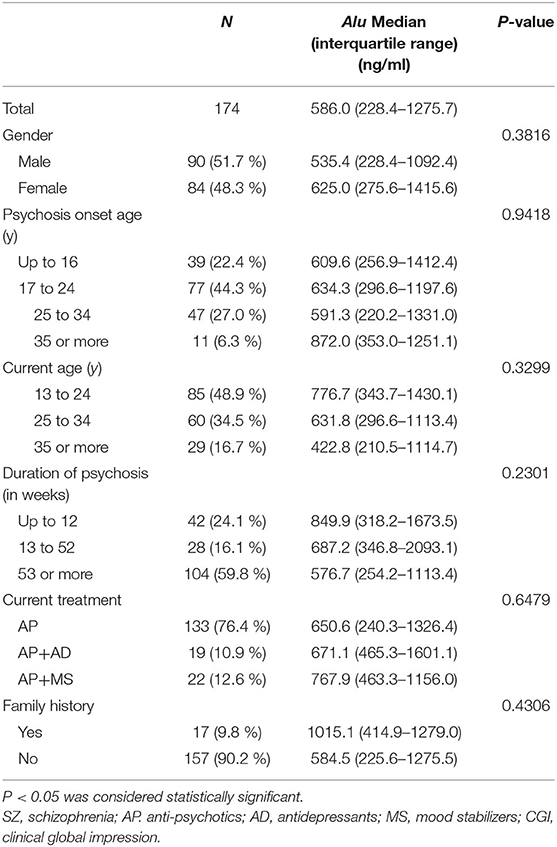

We examined potential correlations between clinical features and the level of Alu. The analysis demonstrated no statistically significant correlation between cf-DNA levels and clinical variables, such as gender (P > 0.05), age at onset (P > 0.05), current age (P > 0.05), duration of psychosis (P > 0.05), current treatment (P > 0.05) and family history (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical features of patients of SZ (n = 174) according to the specific diagnostic categories.

We also examined potential correlations between Alu and the scores of SZ patients. The analysis demonstrated a statistically significant difference between Alu and SZ patients' Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) scores (P < 0.05), but no significant differences with abandonment (P > 0.05), attack (P > 0.05), positive syndrome scale score (P > 0.05) and negative syndrome scale score(P > 0.05) (Table 3).

We analyzed the correlation between the concentration of Alu and biochemical indexes and demonstrated no statistically significant correlation except for RBP (P < 0.05), Cyc (P < 0.05), and NEFA (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

By trcking the 57 newly diagnosed SZ patients, we found the level of Alu before treatment (1040.4 ng/ml, 388.3–1673.4 ng/ml) was higher than the level at post treatment (366.3 ng/ml, 173.3–815.7 ng/ml) (Figure 4). While, the level of Alu in the normal control group is (318.3 ng/ml, 253.5–427.4 ng/ml) (P > 0.05).

Figure 4. RT-qPCR analysis for predicting cf-DNA as a SZ prognosis biomarker. Line chart of serum cf-DNA levels monitored in the 57 primary SZ patients. The different dots represent the individual subjects and the lines connect the baseline value to the corresponding follow-up.

Recent studies have shown that molecular abnormalities play a role in the development and progression of many mental disorders (28). In this study, we found that the concentration of Alu in the SZ group was significantly higher than that of the HC group. Moreover, ROC analysis shows that the Alu was helpful in SZ diagnosis. And the concentration of cf-DNA in the post-treatment patients was decreased significantly in 57 newly diagnosed cases.

In this study, we found that SZ patients had higher levels of cf-DNA in their blood than normal controls, which is consistent with the findings of Jiang (29). Environmental or traumatic stress cascades lead to increased the level of Alu (30). The alu-centric mechanism has been studied to provide a unified framework for many hypotheses regarding the origins of neurodegenerative diseases, including inflammation, oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, and protein body accumulation (31). The reactive oxygen species (ROS) emerges from oxygen metabolism, which is the endogenous source of damage. Elevated ROS levels in the brain and peripheral tissues of the patients with SZ triggers a number of cellular responses in order to facilitate apoptosis have been reported (32, 33). Therefore, we speculate that oxidative stress promotes apoptosis, leading to an increase in Alu level, and Alu level reflects the degree of apoptosis. Our results may provide a new argument for the apoptosis mechanism of schizophrenia and further verify this hypothesis.

A review suggests that an ascent of cf-DNA levels depend on various clinical conditions: lowest cf-DNA levels were found in chronic inflammation, elevated levels in acute inflammation and highest cf-DNA levels were measured in severe infections (34). In our results, the concentration of cf-DNA was not statistically different between undifferentiated, paranoid, and acute SZ-like psychosis. However, the median concentration of cf-DNA in acute SZ-like psychosis was higher than that of the other two subtypes. The different levels of Alu of different types suggest that the pathogenesis of different SZ types and the severity of the disease are different, laying the foundation for our later treatment and analysis of the mechanism of different subtypes.

Furthermore, the ROC analysis showed that the AUC between the SZ and normal control group was 0.6787, with a 51.72% sensitivity and 90% specificity. Using ROC to evaluate the diagnostic utility of cf-DNA indicates that serum cf-DNA can effectively distinguish schizophrenia patients from normal people. In this study, the value of AUC is not ideal, and the sensitivity and specificity of cf-DN as a qualified biomarker need to be further improved. Other indicators need to be added to increase the AUC. Therefore, cf-DNA alone cannot be used to diagnose SZ, and other clinical indicators need to be combined. Based on the above-mentioned experimental results, we further analyzed the correlation between cf-DNA and clinical data and laboratory examination results.

Serum Alu levels exhibited no significant differences regarding gender, age at onset, disease duration, treatment duration, and treatment plan. This suggests that cf-DNA may be an independent indicator at the cellular level relative to these indicators. Therefore, Alu levels will not be affected by gender, age at onset, disease duration, treatment duration, and family history. In addition, there was no statistical difference between Alu and SZ patients' abandonment, attack, positive syndrome scale score and negative syndrome scale score, but there was a difference with CGI. In related studies, in order to evaluate the treatment effect of schizophrenia, a relief definition based on the CGI was developed. The CGI score reflects the severity of the disease and the risk of recurrence (35). This result paves the way for further studies regarding the correlation between cf-DNA concentration and disease severity.

We studied the correlation between Alu and several biochemical indicators. We found that Alu was negatively correlated with RBP and Cyc and positively correlated with NEFA, yet the r values were all small, indicating that the correlation was not significant. Although we unexpectedly found a correlation between cf-DNA and RBP, Cyc, and NEFA, the mechanism remains to be elucidated. It may also need to increase the sample size.

We also found that cf-DNA levels underwent dynamic changes after treatment in the primary patients. And the concentration of cf-DNA in the post-treatment patients was decreased. It indicted that the level of Alu may be related to the course of the disease. Cf-DNA has been described in various diseases, including inflammation, tumors, trauma, stroke, and myocardial infarction (36–38). And the cf-DNA concentrations are significantly increased in patients with poor outcome (39). It was reported that a decrease in cf-DNA levels in response to therapy and elevations associated with recurrence, suggesting that cf-DNA quantification may facilitate monitoring the disease status (40, 41). Patients with high plasma cf-DNA levels either did not respond to treatment or had a higher risk of recurrence (42). Our result is consistent with the phenomenon reported in the literature.

Our results show that Alu can effectively distinguish SZ from normal people, and has a certain indicator effect on the prognosis of SZ patients. Further studies should focus on large-scale sample collection and long-term follow-up, adjust for potential confounding factors, and perform an in-depth functional investigation in order to improve the sensitivity and specificity of this potential biomarker. Overall, it may indicate that cf-DNA could improve the diagnosis of schizophrenia and might be a potential target in the antipsychotic treatment of SZ patients.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Nantong Forth People's Hospital ethics committee (2019 K007). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

L-yC carried out the experiment and wrote the paper. JQ analyzed the date. H-lX performed experiments. X-yL collected samples. S-qJ and Y-jS designed the research. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by The Six Talent Peaks Projects of Jiangsu Province (2012-ws-119) and The Health and Planning Project of Nantong (QB2019010).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study for making this study possible. This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-16334/v1, L-yC, JQ, H-lX, X-yL, Y-jS, and S-qJ.

SZ, schizophrenia; AP, Anti-psychotics; AD, Antidepressants; MS, Mood stabilizers; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; Glu, glucose; CG, glycocholic acid; TBil, total bilirubin; DBil, direct bilirubin; TP, total protein; ALB, albumin; GLO, globulin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; LDH, lactic dehydrogenase; HBDH, hydoxybutyrate dehydrogenase; CK, creatine kinase; CK-MB, creatine kinase MB; CHE, pseudocholinesterase; PA, prealbumin; ADA, adenosine deaminase; BUN, urea nitrogen; CRE, creatinine; UA, uric acid; β2MG, β2-microglobulin; RBP, retinol-binding protein; Cys C, cystatin C; K, kalium; Na, sodium; Cl, chlorinum; Ca, calcium; P, phosphor; Mg, magnesium; CO2, carbon dioxide; CHOL, total cholesterol; TG, triacylglycerol; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; APOAI, apolipoprotein AI; APOB, apolipoprotein B; APOE, apolipoprotein E; LP(a), lipoprotein; NEFA, free fatty acid.

1. Halldorsdottir T, Binder EB. Gene × environment interactions: from molecular mechanisms to behavior. Annu Rev Psychol. (2017) 68:215–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044053

2. Kahn RS, Sommer IE, Murray RM. Insel TR. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2015) 1:15067. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.67

3. Chan MK, Krebs MO, Cox D, Guest PC, Yolken RH, Rahmoune H, et al. Development of a blood-based molecular biomarker test for identification of schizophrenia before disease onset. Transl Psychiatry. (2015) 5:e601. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.91

4. Perkovic MN, Erjavec GN, Strac DS, Uzun S, Kozumplik O, Pivac N. Theranostic biomarkers for schizophrenia. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:733. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040733

5. Horváth S, Mirnics K. Immune system disturbances in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. (2014) 75:316–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.06.010

6. Valerio A, Cardile A, Cozzi V, Bracale R, Tedesco L, Pisconti A, et al. TNF-alpha downregulates eNOS expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in fat and muscle of obese rodents. J Clin Invest. (2006) 116:2791–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI28570

7. Qiu MJ, Li SC, Jin LZ, Feng PN, Kong YL, Zhao XD, et al. Combination of chymostatin and aliskiren attenuates ER stress induced by lipid overload in kidney tubular cells. Lipids Health Dis. (2018) 17:183. doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0818-1

8. Li J. Neuroprotective effect of (–)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate on autoimmune thyroiditis in a rat model by an anti-inflammation effect, anti-apoptosis and inhibition of TRAIL signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. (2018) 15:1087–92. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5511

9. Oppenheim RW. Cell death during development of the nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. (1991) 14:453–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002321

10. Jarskog LF, Selinger ES, Lieberman JA, Gilmore JH. Apoptotic proteins in the temporal cortex in schizophrenia: high Bax/Bcl-2 ratio without caspase-3 activation. Am J Psychiatry. (2004) 161:109–15. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.109

11. Jarskog LF, Gilmore JH, Selinger ES, Lieberman JA. Cortical bcl-2 protein expression and apoptotic regulation in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. (2000) 48:641–50. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00988-4

12. Mandel P, Metais P. Les acides nucleiques du plasma sanguin chezl'Homme. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. (1948) 142:241–43.

13. Leon SA, Shapiro B, Sklaroff DM, Yaros MJ. Free DNA in the serum of cancer patients and the effect of therapy. Cancer Res. (1977) 37:646–50.

14. Jiang P, Lo YMD. The long and short of circulating cell-free DNA and the ins and outs of molecular diagnostics. Trends Genet. (2016) 32:360–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.03.009

15. Jahr S, Hentze H, Englisch S, Hardt D, Fackelmayer FO, Hesch RD, et al. DNA fragments in the blood plasma of cancer patients: quantitations and evidence for their origin from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Cancer Res. (2001) 61:1659–65.

16. Choi JJ, Reich CF, Pisetsky DS. The role of macrophages in the in vitro generation of extrcellular DNA from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Immunology. (2005) 115:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02130.x

17. Wang BG, Huang HY, Chen YC, Bristow RE, Kassauei K, Cheng CC, et al. Increased plasma DNA integrity in cancer patients. Cancer Res. (2003) 63:3966–8.

18. Mehta SR, Pérez-Santiago J, Hulgan T, Day TR, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Gittleman H, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid cell-free mitochondrial DNA is associated with HIV replication, iron transport, and mild HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment. J Neuroinflammation. (2017) 14:72. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0848-z

19. Pérez-Santiago J, De Oliveira MF, Var SR, Day TRC, Woods SP, Gianella S, et al. Increased cell-free mitochondrial DNA is a marker of ongoing inflammation and better neurocognitive function in virologically suppressed HIV-infected individuals. J Neurovirol. (2017) 23:283–9. doi: 10.1007/s13365-016-0497-5

20. Fernandes A, Miller-Fleming L, Pais TF. Microglia and inflammation: conspiracy, controversy or control? Cell Mol Life Sci. (2014) 71:3969–85. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1670-8

21. Jeffrey A, Lieberman JA, Frank P, Bymaster FP, Herbert Y, Meltzer HY, et al. Antipsychotic drugs: comparison in animal models of efficacy, neurotransmitter regulation, and neuroprotection. Pharmacol Rev. (2008) 60:358–03. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.00107

22. Lipska BK, Jaskiw GE, Weinberger DR. Postpubertal emergence of hyperresponsiveness to stress and to amphetamine after neonatal excitotoxic hippocampal damage: a potential animal model of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. (1993) 9:67–75. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.44

23. Lipska BK, Weinberger DR. To model a psychiatric disorder in animals: schizophrenia as a reality test. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2000) 23:223–39. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00137-8

24. Hill RA. Sex differences in animal models of schizophrenia shed light on the underlying pathophysiology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2016) 67:41–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.10.014

25. Singh SP, Cooper JE, Fisher HL, Tarrant CJ, Lloyd T, Banjo J, et al. Determining the chronology and components of psychosis onset: the nottingham onset schedule (NOS). Schizophr Res. (2005) 80:117–30. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.018

26. Hopkins SC, Ogirala A, Loebel A, Koblan KS. Transformed PANSS factors intended to reduce pseudospecificity among symptom domains and enhance understanding of symptom change in antipsychotic-treated patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2018) 44:593–02. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx101

27. Umetani N, Kim J, Hiramatsu S, Reber HA, Hines OJ, Bilchik AJ, et al. Increased integrity of free circulating DNA in sera of patients with colorectal or periampullary cancer: direct quantitative PCR for ALU repeats. Clin Chem. (2006) 52:1062–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.068577

28. Hartwig FP, Borges MC, Horta BL, Bowden J, Smith GD. Inflammatory biomarkers and risk of schizophrenia: a 2-sample mendelian randomization study. JAMA Psychiatry. (2017) 74:1226–33. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3191

29. Jiang J, Chen XL, Sun LY, Qing Y, Yang XH, Hu XW, et al. Analysis of the concentrations and size distributions of cell-free DNA in schizophrenia using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Transl Psychiatry. (2018) 8:104–12. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0153-3

30. Li TH, Schmid CW. Differential stress induction of individual Alu loci: implications for transcription and retrotransposition. Gene. (2001) 276:135–41. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00637-0

31. Larsen PA, Hunnicutt KE, Larsen RJ, Yoder AD, Saunders AM. Warning SINEs: Alu elements, evolution of the human brain, and the spectrum of neurological disease. Chromosome Res. (2018) 26:93–111. doi: 10.1007/s10577-018-9573-4

32. Emiliani FE, Sedlak TW, Sawa A. Oxidative stress and schizophrenia: recent breakthroughs from an old story. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2014) 27:185–190. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000054

33. Smaga I, Niedzielska E, Gawlik M, et al. Oxidative stress as an etiological factor and a potential treatment target of psychiatric disorders. Part 2. Depression, anxiety, schizophrenia and autism. Pharmacol Rep. (2015) 67:569–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.12.015

34. Frank MO. Circulating cell-free DNA differentiates severity of inflammation. Biol Res Nurs. (2016) 18:477–88. doi: 10.1177/1099800416642571

35. Schennach R, Obermeier M, Spellmann I, Seemüller F, Musil R, Jäger M, et al. Remission in schizophrenia - what are we measuring? Comparing the consensus remission criteria to a CGI-based definition of remission and to remission in major depression. Schizophr Res. (2019) 209:185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.04.022

36. Giacona MB, Ruben GC, Iczkowski KA, Roos TB, Porter DM, Sorenson GD. Cell-free DNA in human blood plasma: length measurements in patients with pancreatic cancer and healthy controls. Pancreas. (1998) 17:89–97. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199807000-00012

37. Schwarzenbach H, Hoon DS, Pantel K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nat Rev Cancer. (2011) 11:426–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc3066

38. Wan JCM, Massie C, Garcia-Corbacho J, Mouliere F, Brenton JD, Caldas C, et al. Liquid biopsies come of age: towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat Rev Cancer. (2017) 17:223–38. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.7

39. Huttunen R, Kuparinen T, Jylhävä J, Aittoniemi J, Vuento R, Huhtala H, et al. Fatal outcome in bacteremia is characterized by high plasma cell free DNA concentration and apoptotic DNA fragmentation: aprospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e21700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021700

40. Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, Murtaza M, Biggs H, Rueda OM, Chin SF, et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. (2013) 368:1199–209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213261

41. Frattini M, Gallino G, Signoroni S, Balestra D, Battaglia L, Sozzi G, et al. Quantitative analysis of plasma DNA in colorectal cancer patients: a novel prognostic tool. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2006) 1075:185–90. doi: 10.1196/annals.1368.025

Keywords: biomarker, schizophrenia, apoptosis, circulating cell-free DNA, Alu

Citation: Chen L-y, Qi J, Xu H-l, Lin X-y, Sun Y-j and Ju S-q (2021) The Value of Serum Cell-Free DNA Levels in Patients With Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 12:637789. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.637789

Received: 04 December 2020; Accepted: 08 March 2021;

Published: 30 March 2021.

Edited by:

Kyriaki Sidiropoulou, University of Crete, GreeceReviewed by:

Weihua Yue, Peking University Sixth Hospital, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Chen, Qi, Xu, Lin, Sun and Ju. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shao-qing Ju, anNxODE0QGhvdG1haWwuY29t; Ya-jun Sun, MzY0NDE4NDA4QHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.