- 1Department of Psychiatry, Enam Medical College and Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 2School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, India

- 4Department of Psychiatry, Jawahar Lal Nehru Memorial Hospital (JLNMH), Srinagar, India

- 5Department of Administration, College of Humanities, University of Raparin, Ranya, Iraq

Background: As an erratic human behavior, panic buying is an understudied research area. Although panic buying has been reported in the past, it has not been studied systematically in Bangladesh.

Aim: This study aimed to explore the characteristics of panic buying episodes in Bangladesh in comparison to current concepts.

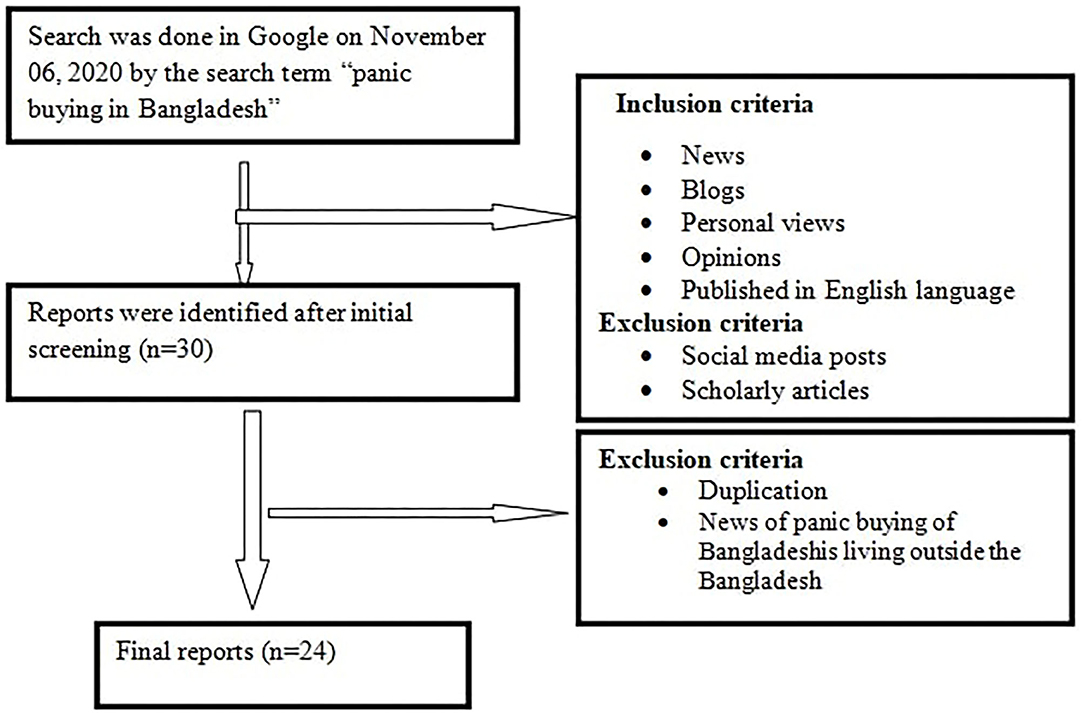

Methods: A retrospective and explorative search were done using the search engine Google on November 6, 2020, with the search term “panic buying in Bangladesh.” All the available news reports published in the English language were extracted. A thorough content analysis was done focusing on the study objectives.

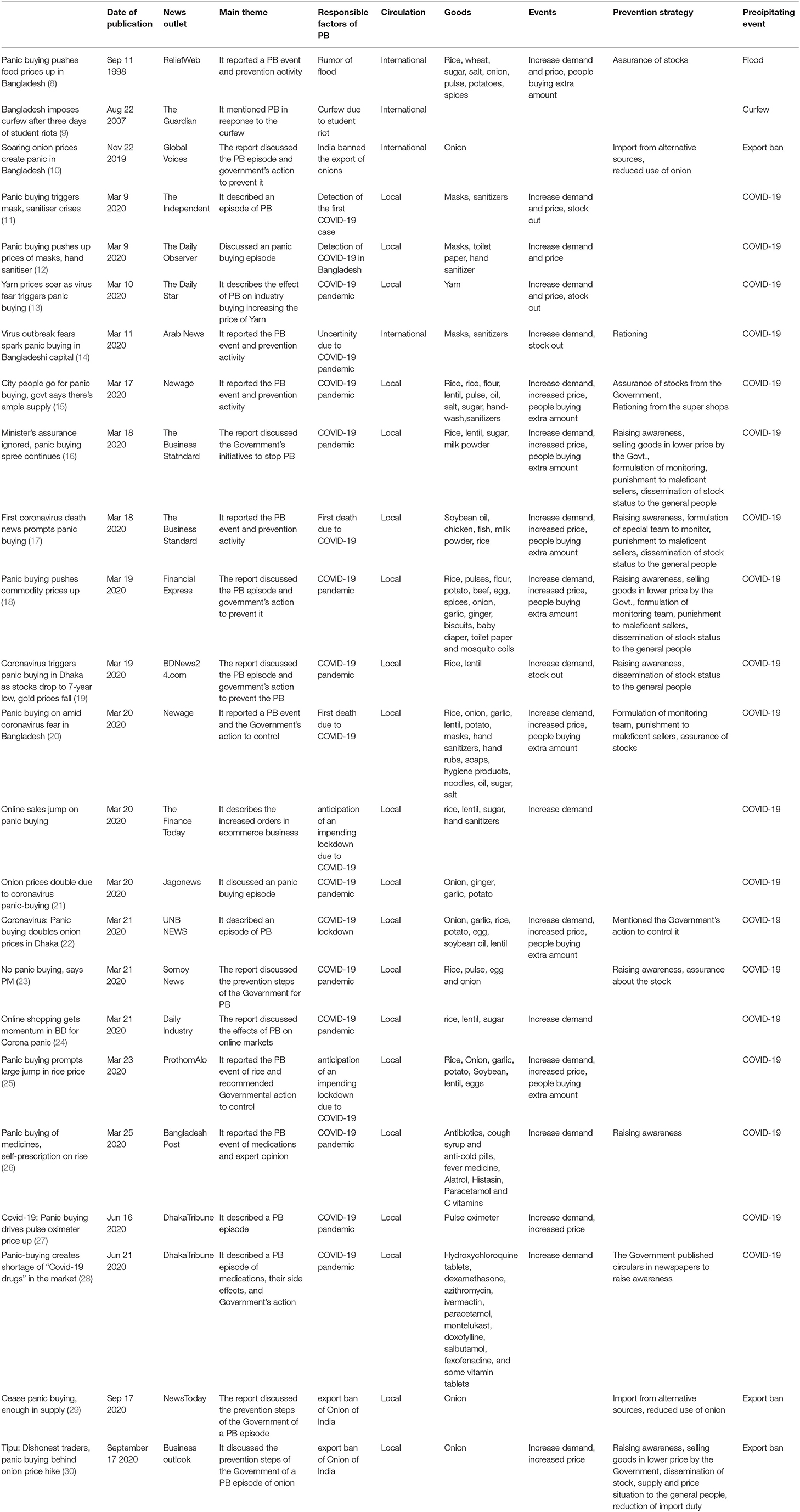

Results: From the initial search, a total of 30 reports were extracted. However, six reports were not included based upon the exclusion criteria, resulting in an analysis of 24 reports. Five panic buying episodes were identified, discussing the precipitating events, responsible factors, goods acquired through panic buying, and prevention measures. Flood, curfew, COVID-19, and export ban were found to be precipitating events. Media reports frequently mentioned prevention strategies, expert opinion, supply chain status, rationing, and government action. The reported goods that were panic bought were items necessary for daily living such as rice, oil, spices, and safety products such as hand sanitizer and masks.

Conclusion: The study revealed preliminary findings on panic buying in Bangladesh; however, they are aligned with the current concept of it. Further empirical studies are warranted to see the geographical variation, precise factors, and to test the culturally appropriate controlling measures.

Introduction

Panic buying (PB) is an erratic human behavior that has been noticed in at least 93 countries all over the world during the COVID-19 pandemic (1). Outbreaks of infectious diseases can trigger feelings of uncertainty and violate an individual's sense of control (2, 3). Fueled by concerns about running out of certain items and goods, people tend to indulge in panic buying which gives them a semblance of control over a situation (1). Panic buying has been defined as “the phenomenon of a sudden increase in buying of one or more essential goods in excess of regular need provoked by adversity, usually a disaster or an outbreak resulting in an imbalance between supply and demand” (4). Several important aspects have been considered for PB, such as a sharp increase in the purchase of important necessary goods in excess of needs, usually precipitated by adverse events. It may be impulsive or well-planned (5).

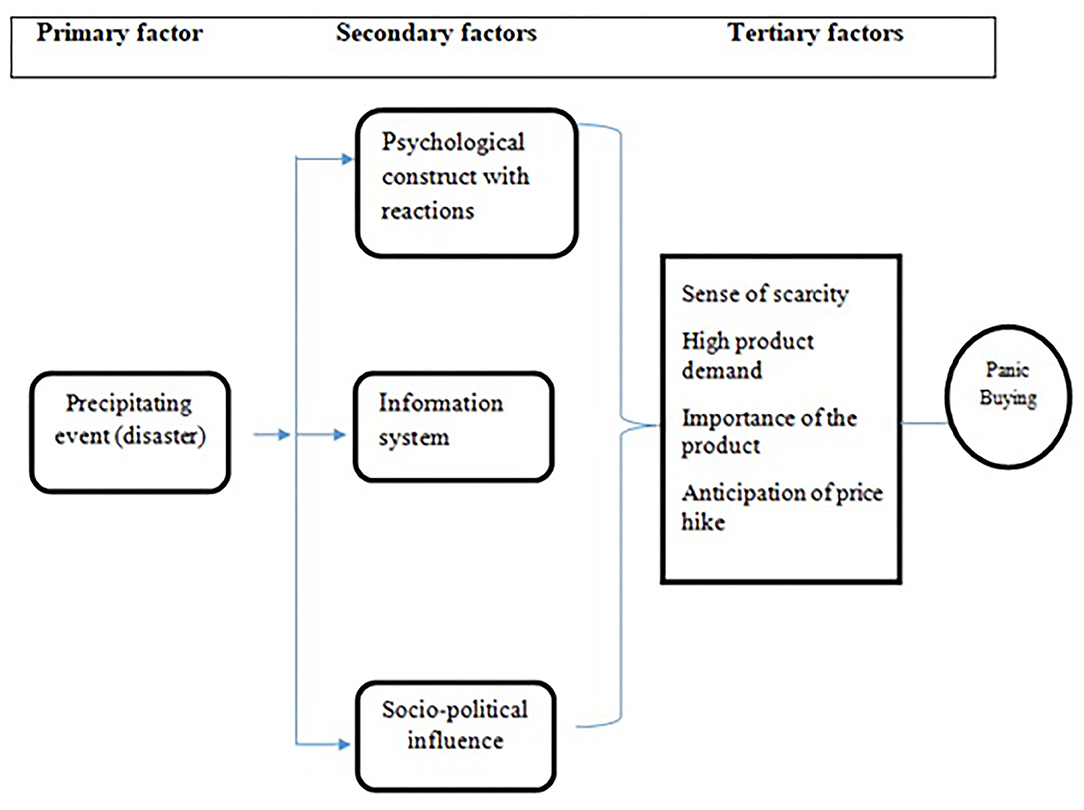

A previous study also postulated a causative model of PB mentioning that any adverse precipitating event usually stimulates this behavior (1). As per the model, the adverse stimuli act as precipitating events and initiate the behavior (1). Subsequently, secondary factors (psychosocial construct and information system), and tertiary factors (increased demand, the necessity of the product, supply chain, and anticipation of price hike) interact and shape it (1) (Figure 1). Several psychological factors have been postulated such as perceived scarcity, gaining control, fear of uncertainty, media influence, social behavior explaining the PB (1, 2). One study identified that a perceived scarcity, increased demand, necessary goods, the anticipation of price hike, any adverse situations, rumors, psychological reactions, social influences, a lack of trust in authority (government action), and experience were the attributed factors of PB (1).

Figure 1. Responsible factors for panic buying [adapted from (1)].

PB has many negative effects such as disruption of supply chains, artificial commodity shortages, and stoke price rise. Furthermore, large crowds and queues appearing in retail spaces and stores could result in further clusters. Some prevention strategies have been proposed such as responsible media reporting, kinship promotion, rationing, assurance from the authority, some psychological measures to prevent the episodes (6, 7).

Given this scenario, there is a need for further research into the precipitating factors of PB, evaluating the responsible factors, and possible mitigating strategies. Country specific research on PB is limited though, and it is crucial to consider prevention strategies. Against this background, we conducted the present analysis to assess the characteristics of panic buying episodes in Bangladesh, a populous country in South-East Asia. In particular, we aimed to evaluate precipitating events, responsible factors, goods of panic buying, and control strategies. Driven by previous research methods in PB, we used media reports to identify articles related to PB for analysis. The goal was to provide country-specific data that may inform management and prevention strategies to control PB.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

A retrospective and explorative search were done in Google on November 6, 2020, with the search term “panic buying in Bangladesh.” All the available news reports published in the English language were extracted. A thorough content analysis was done focusing on the study objectives. A method of three previous similar studies was followed to extract the reports, analyze the contents, identify the panic buying goods, assess the media reports, trace the responsible factors, and mention the controlling strategies (1, 4, 6). The detailed data extraction is outlined in Figure 2.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this analysis include reports from any report discussing panic buying from the media covering news, blogs, personal views, opinions that were published in English. Vernacular (Bangla) reports were not considered due to a lack of specification of the exact Bangla word for “panic buying.”

Exclusion Criteria

Social media posts, scholarly articles, duplications, and news of the panic buying behaviors of Bangladeshis living outside Bangladesh were excluded from the study. Social media posts were excluded because they are supposed to be more emotionally charged and are very often biased. We excluded scholarly articles because we aimed to assess primary observations reported in the media. Various types of scholarly articles with various objectives would dislocate the research focus. Moreover, conformity bias, group-thinking, and herd behavior may be considered as potential sources of biases in social media posts (1).

Statistical Analysis

We used the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet 2019 version for data coding. As a preliminary explorative study detail, statistical analysis was not performed.

Ethical Statement

The study was conducted in compliance with the declaration of Helsinki (1964). As we analyzed publicly available media reports, no formal ethical approval was obtained.

Results

From the initial extraction, a total of 30 reports were retrieved. However, six reports were dropped after considering the exclusion criteria, resulting in the analysis of 24 reports (Figure 1). From the 24 reports, five panic buying episodes were identified and the precipitating events, responsible factors, goods of panic buying, and prevention measures were discussed.

Precipitating Events

From the reports, flood, curfew, COVID-19, and export bans (2) were found to be precipitating events that initiated the PB. All the reported episodes had a precipitating event like a flood, curfew, COVID-19, and export ban of onion (Table 1).

Responsible Factors

Several attributing factors were identified from the reports such as rumor of danger (flood), curfew, policy ban, uncertainty, the anticipation of an impending lockdown, increased demand, anticipation of price hike, and anticipation of short supply (Table 1).

Goods of Panic Buying

The reported goods are necessary for daily living such as rice, sugar, salt, onion, pulse, potatoes, spices, masks, sanitizers, toilet paper, flour, lentil, pulse, oil, milk powder, chicken, fish, beef, egg, garlic, ginger, biscuits, baby diaper, mosquito coils, soaps, hygiene products, noodles, drugs (antibiotics, cough syrup, and anti-cold pills, fever medicine, hydroxychloroquine, dexamethasone, ivermectin, montelukast, doxofylline, salbutamol, some vitamin tablets), and pulse oximeter (Table 1).

Prevention Strategies

Media reports frequently mentioned prevention strategies, expert opinion, supply chain status, rationing, and government action. Raising awareness, selling goods at a lower price by the government, formulation of the special monitoring team, punishment to maleficent sellers, dissemination of stock status to the general people, assurance of stocks, import from alternative sources, reduced use of goods (onion), rationing while selling from the super shops, publishing circulars in newspapers to raise awareness, and a reduction of import duty were the controlling measures identified by the analysis.

Discussion

Panic buying is an under-researched area even though it is common behavior during emergencies. This study aimed to identify the characteristics of panic buying episodes in Bangladesh in comparison to current concepts. We checked 24 published news reports (Table 1) to identify the precipitating events, products, events, responsible factors, goods of panic buying, and prevention measures. Five panic buying episodes were identified.

Current Concepts of PB

From the available evidence, we established that PB usually starts with an adverse stimulus, and people usually buy necessary goods in response to several psychological reactions (1–4). Media has a bidirectional role on PB which can either control or exacerbate (6, 7). Controlling media reporting, kinship promotion, the rationing of the products, assurance regarding safe supply, policy change, raising awareness, selling goods at a subsidized price have been noted as prevention strategies (6, 7).

Main Findings of the Study

The first episode happened in 1998 where a flood acted as a precipitating event. During this event rice, wheat, sugar, salt, onion, pulse, potatoes, and spices were brought, and assurance of adequate stocks was disseminated (8). The second episode happened in 2007 where curfew due to student riot acted as a precipitating event and necessary goods were brought (9). The third episode happened in 2019 where the export ban of the onion of a neighboring country acted as a precipitating event (10). The fourth episode was precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic (11–29). The fifth episode was precipitated by another export ban of the onion by India (30, 31). Media reports frequently mentioned prevention strategies, expert opinion, supply chain status, rationing, and Government action (Table 1). The reported goods are necessary for daily living, for example, medications and safety products (Table 1). Several controlling measures were practiced in Bangladesh during the episodes and the government used initiatives. The episodes describing the characteristics of PB fit with the existing concept of panic buying in regards to precipitating events, responsible factors, goods, and measures. Although the episodes covered two different times (COVID-19 and others) the characteristics are similar.

The study revealed primitive characteristics of panic buying episodes, where it starts with adverse stimuli, have an extra buying of necessary goods, resulting in disruption of supply chains supporting the existing causative model of PB proposed by Arafat et al. (1). The practiced prevention strategies have also been supported by previous recommendations (31). Other studies also reported on items sought panic buying which are usually daily necessities (4, 32). The media reports have positive reporting characteristics, as revealed by recent studies (6).

Strengths of the Study

This is the first systematic assessment of panic buying in Bangladesh and reveals preliminary explorative findings that could help to formulate prevention strategies in future.

Limitations

Data were extracted from media reports which are not of scientific quality. The sample size was small. Data extraction and the search were done by a single person (first author). No structured instrument was used to extract the data. Only English language reports were studied.

Conclusion

The study revealed preliminary findings of panic buying in Bangladesh. However, they are aligned with the current concept of panic buying. Further empirical studies are warranted to explore geographical variation, demographics (e.g., education, income), consumption behavior, precise factors, and to test culturally appropriate control measures.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted complying with the declaration of Helsinki (1964). As we analyzed the publicly available media reports, no formal ethical approval was obtained.

Author Contributions

SA contributed to the concept, design, data analysis, and writing. All authors contributed to manuscript writing, revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by Nanyang Technological University, Internal Funding, Start-Up Grant, College of Engineering.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Menon V, Alradie-Mohamed A, Mukherjee S, Kaliamoorthy C, et al. Responsible factors of panic buying: an observation from online media reports. Front Publ Health. (2020) 8:603894. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.603894

2. Yuen KF, Wang X, Ma F, Li KX. The psychological causesofpanic buying following a health crisis. Int J Environ Res. (2020) 17:3513. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103513

3. Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Marthoenis M, Sharma P, HoqueApu E, Kabir R. Psychological underpinning of panic buying during pandemic (COVID-19). Psychiatry Res. (2020) 289:113061. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113061

4. Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Menon V, Kaliamoorthy C, Mukherjee S, Alradie-Mohamed A, et al. Panic buying: an insight from the content analysis of media reports during COVID-19 pandemic. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. (2020) 37:100–3. doi: 10.1016/j.npbr.2020.07.002

5. Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Menon V, Sharma P, Marthoenis M, Kabir R. Panic buying during COVID-19 pandemic: a letter to the editor. Ann Indian Psychiatry. (2020) 4:242–3. doi: 10.4103/aip.aip_48_20

6. Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Menon V, Marthoenis M, Sharma P, Alradie-Mohamed A, et al. Media portrayal of panic buying: a content analysis of online news portals. Glob Psychiatry. (2020) 3:249–54. doi: 10.2478/gp-2020-0022

7. Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Kabir R. Possible controlling measures of panic buying during COVID-19. Int J Ment Heal Addict. (2020). doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00320-1. [Epub ahead of print].

8. Quadir SI. Panic Buying Pushes Food Prices Up in Bangladesh. Reliefweb (1998). Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/panic-buying-pushes-food-prices-bangladesh (accessed November 9, 2020).

9. Ramesh R. Bangladesh Imposes Curfew After Three Days of Student Riots. Guardian (2007). Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/aug/22/bangladesh (accessed November 9, 2020).

10. Rezwan. Soaring Onion Prices Create Panic in Bangladesh. Global Voices (2019). Available online at: https://globalvoices.org/2019/11/22/soaring-onion-prices-create-panic-in-bangladesh/ (accessed November 9, 2020)

11. The Independent. Panic Buying Triggers Mask, Sanitiser Crises. (2020). Available online at: http://www.theindependentbd.com/post/240183 (accessed November 9, 2020).

12. The Daily Observer. Panic Buying Pushes Up Prices of Masks, Hand Sanitiser. (2020). Available online at: https://www.observerbd.com/details.php?id=248410 (accessed November 9, 2020).

13. Mirdha RU. Yarn Prices Soar as Virus Fear Triggers Panic Buying. Daily Star (2020). Available online at: https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/yarn-prices-soar-virus-fear-triggers-panic-buying-1878652 (accessed November 9, 2020).

14. Sumon S. Virus Outbreak Fears Spark Panic Buying in Bangladeshi Capital. Arab News (2020). Available online at: https://www.arabnews.com/node/1639791/world (accessed November 9, 2020).

15. New Age. Panic Buying on Amid Coronavirus Fear in Bangladesh. (2020). Available online at: https://www.newagebd.net/article/102714/panic-buying-on-amid-coronavirus-fear-in-bangladesh (accessed November 8, 2020).

16. New Age. City People Go for Panic Buying, Govt Says There's Ample Supply. (2020). Available online at: https://www.newagebd.net/article/102487/city-people-go-for-panic-buying-govt-says-theres-ample-supply (accessed November 8, 2020).

17. TBS Report. Minister's Assurance Ignored, Panic Buying Spree Continues. Business Standard (2020). Available online at: https://tbsnews.net/bangladesh/govt-urges-people-not-hoard-enough-food-country-58204 (accessed November 7, 2020).

18. TBS Report. First Coronavirus Death News Prompts Panic Buying. Business Standard (2020). Available online at: https://tbsnews.net/economy/trade/first-coronavirus-death-news-prompts-panic-buying-58210 (accessed November 7, 2020).

19. The Financial Express. Panic Buying Pushes Commodity Prices Up. (2020). Available online at: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/trade/panic-buying-pushes-commodity-prices-up-1584590224 (accessed November 8, 2020).

20. Atik F. Coronavirus Triggers Panic Buying in Dhaka as Stocks Drop to 7-Year Low, gold prices Fall. bdnews24.com (2020). Available online at: https://bdnews24.com/business/2020/03/19/coronavirus-triggers-panic-buying-in-dhaka-as-stocks-drop-to-7-year-low-gold-prices-fall (accessed November 9, 2020).

21. Sami. Online Sales Jump on Panic Buying. Finance Today (2020). Available online at: https://www.thefinancetoday.net/article/business/9407/Online-sales-jump-on-panic-buying (accessed November 9, 2020).

22. Jagonews. Onion Prices Double Due to Coronavirus Panic-Buying. (2020). Available online at: https://www.jagonews24.com/en/business/news/48751 (accessed November 9, 2020).

23. UNB. Panic Buying Prompts Large Jump in Rice Price. Prothomalo (2020). Available online at: https://en.prothomalo.com/business/local/panic-buying-prompts-large-jump-in-rice-price (accessed November 9, 2020).

24. Somoy News. No Panic Buying, Says PM. (2020). Available online at: https://en.somoynews.tv/6354/news/No-panic-buying-says-PM (accessed November 9, 2020).

25. Daily Industry. Online Shopping Gets Momentum in BD for Corona Panic. (2020). Available online at: http://www.dailyindustry.news/online-shopping-gets-momentum-bd-corona-panic/ (accessed November 9, 2020).

26. Alam MJ, Islam R. Coronavirus: Panic Buying Doubles Onion Prices in Dhaka. (2020). Available online at: https://unb.com.bd/category/special/coronavirus-panic-buying-doubles-onion-prices-in-dhaka/47638 (accessed November 7, 2020).

27. Sourav DS. Panic Buying of Medicines, Self-Prescription on Rise. Bangladesh Post (2020). Available online at: https://bangladeshpost.net/posts/panic-buying-of-medicines-self-prescription-on-rise-29691 (accessed November 9, 2020).

28. Amin MA. Covid-19: Panic Buying Drives Pulse Oximeter Price Up. (2020). Available online at: https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2020/06/16/covid-19-panic-buying-hikes-price-of-pulse-oximeters (accessed November 8, 2020).

29. Rahman M. Panic-Buying Creates Shortage of ‘Covid-19 Drugs’ in the Market. (2020). Available online at: https://www.dhakatribune.com/health/coronavirus/2020/06/21/panic-buying-creates-shortage-of-covid-19-drugs-in-the-market (accessed November 7, 2020).

30. News Today. Cease Panic Buying, Enough in Supply. (2020). Available online at: http://www.newstoday.com.bd/index.php?option=details&news_id=2568375&date=2020-09-17 (accessed November 9, 2020).

31. Business outlook. Tipu: Dishonest Traders, Panic Buying Behind Onion Price Hike. (2020). Available online at: https://businessoutlookbd.com/2020/09/17/tipu-dishonest-traders-panic-buying-behind-onion-price-hike/ (accessed November 9, 2020).

Keywords: panic buying, Bangladesh, news reports, content analysis, COVID-19

Citation: Arafat SMY, Yuen KF, Menon V, Shoib S and Ahmad AR (2021) Panic Buying in Bangladesh: An Exploration of Media Reports. Front. Psychiatry 11:628393. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.628393

Received: 11 November 2020; Accepted: 18 December 2020;

Published: 18 January 2021.

Edited by:

Elisa Harumi Kozasa, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, BrazilReviewed by:

Maria Kordowicz, University of Lincoln, United KingdomJianan Li, Jilin University, China

Copyright © 2021 Arafat, Yuen, Menon, Shoib and Ahmad. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kum Fai Yuen, a3VtZmFpLnl1ZW5AbnR1LmVkdS5zZw==

S. M. Yasir Arafat

S. M. Yasir Arafat Kum Fai Yuen

Kum Fai Yuen Vikas Menon

Vikas Menon Sheikh Shoib

Sheikh Shoib Araz Ramazan Ahmad

Araz Ramazan Ahmad