- 1Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, Center for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 3JHU Global mHealth Initiative, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 4Department of Psychiatry and Child Study Center, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

- 5Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling, Wethersfield, CT, United States

- 6Connecticut Mental Health Center, New Haven, CT, United States

- 7Department of Neuroscience, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

- 8Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 9Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, Center for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON, Canada

Internet gambling has become a popular activity among some youth. Vulnerable youth may be particularly at risk due to limited harm reduction and enforcement measures. This article explores age restrictions and other harm reduction measures relating to youth and young adult online gambling. A systematic rapid review was conducted by searching eight databases. Additional articles on online gambling (e.g., from references) were later included. To place this perspective into context, articles on adult gambling, land-based gambling, and substance use and other problematic behaviors were also considered. Several studies show promising findings for legally restricting youth from gambling in that such restrictions may reduce the amount of youth gambling and gambling-related harms. However, simply labeling an activity as “age-restricted” may not deter youth from gambling; in some instances, it may generate increased appeal for gambling. Therefore, advertising and warning labels should be examined in conjunction with age restrictions. Recommendations for age enforcement strategies, advertising, education, and warning labels are made to help multiple stakeholders including policymakers and public health officials internationally. Age restrictions in online gambling should consider multiple populations including youth and young adults. Prevention and harm reduction in gambling should examine how age-restriction strategies may affect problem gambling and how they may be best enforced across gambling platforms. More research is needed to protect youth with respect to online gambling.

Introduction

People with gambling problems typically meet criteria for hazardous gambling, betting or gambling disorder in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th edition (1, 2). Global estimates of 10- to 24-year-olds suggest 0.2–12% of youth and young adults experience gambling problems (3, 4), with an additional 8–14% at risk for developing gambling problems (5). Online gambling prevalence in 13- to 24-year-olds range between 4 and 24% (6). It is estimated that 2.5% of youth, or 18.1% of those who gambled online, experiences problematic gambling (7).

Gambling-related harms may be experienced by those who gamble, associated individuals, and communities through social systems and/or health systems costs (8, 9). The Conceptual Framework of Harmful Gambling proposed that the definition of harmful gambling is, “any type of repetitive gambling that a person engages in that leads to (or aggravates) recurring negative consequences, such as significant financial problems, addiction, or physical and mental health issues.” p. 4 (9). Such harms may include financial and interpersonal problems (10, 11), nongambling psychiatric disorders (12, 13), and they could increase strain on welfare systems and generate economic harms in the community (8). Youth and young adults may be particularly susceptible to problem-gambling-related harms, especially to online gambling since it is often fast-paced and easily accessible (6, 14, 15). As new forms of online gambling emerge, the issue of problem gambling in youth may become more prevalent and differ significantly from land-based gambling (e.g., at in-person venues like casinos).

Enforcement of harm reduction measures related to online gambling varies. Youth may gamble online by clicking to indicate they are “over 18 years old.” Furthermore, a convergence of gambling and videogaming has implications for youth gambling. Limited or no age restrictions for online games such as free-to-play slot machines may allow youth early opportunities to engage in gambling-like activities that may lead to gambling problems (16). Social casino games (SCGs) that involve virtual currency may lead to monetary gambling (17, 18). Other videogaming-related features such as loot boxes1 (19) and skins betting2 (20) offer non-monetary rewards with in-game value that may also have monetary value. A convergence between gambling and videogaming platforms may facilitate behavioral involvement across networks and consoles, providing robust access to gambling-like activities (21). It is therefore important to understand how best to use age restrictions and other harm-reduction measures for online gambling and videogaming in preventing or minimizing online-gambling-related harms.

Methods

A rapid review was conducted for age restrictions and warning labels in youth gambling by searching Cochrane, PsychInfo, Embase, Medline, Child Development and Adolescent Studies, PAIS, Web of Science, and Social Care Online between February 2–18, 2020. In order to put this perspective narrative into context, additional articles on online gambling were included between March to November 2020 through database and internet searches. Articles on adult gambling, land-based gambling, and other potentially risky behaviors were considered. Here, “youth” refers to people under the legal gambling age; however, young adults are also considered since some youth studies included people up to age 25. Further rationale for including young adults is described below.

Youth and Young Adult Online Gambling

Youth are often exposed to gambling at early ages, and many gamble online (22). The idea that gambling is potentially harmful for youth is longstanding. In 1978, Cornish (23) stated that it is dangerous to introduce gambling to youth because their lives are not yet structured by the constraints, obligations, and rewards that adults have which act to prevent excessive involvement with gambling. An early age of gambling onset is associated with developing gambling problems, particularly for males (24–26), and more severe gambling problems later in life (27). Early gambling also is associated with serious negative psychological, social, financial, and substance use problems (28–30).

Adolescents are more inclined to participate in, and underestimate the risk of risk-taking behaviors such as substance use and online gambling (3, 31). Failure to address youth concerns may lead to negative impacts (15, 32). However, young adults (ages 18–24) may also be at elevated risk given neurodevelopmental processes underlying risk-taking and addictive behaviors. Emotional regulation, logic and other processes are not fully developed by young adulthood (33). Therefore, poor decision-making may lead young adults to take more risks and act more impulsively when gambling (33). For example, individuals aged 18–20 years are particularly likely to chase losses and bet more than they can afford (33). This may present a problem because young adults up to 25 years old may be overlooked by gambling legislation in several countries that have legal age restrictions for those under 18- to 21-year-olds.

Youth and young adult online gambling is a growing concern as studies suggest that this demographic is shifting away from land-based gambling to online gambling (34–36). Youth are also moving from social gambling with friends to solo gambling online that is available across time and locations (14). This is particularly concerning since, for youth, online gambling has been associated more with problem gambling than land-based gambling. International studies found higher proportions of problem gambling among youth who gambling online vs. non-online (34, 36–38). Jurisdictions should enact and enforce strict measures to stop early gambling in order to prevent the onset of gambling problems later in life.

Convergence of Gambling and Videogaming

Videogames that include gambling-like features or free-to-play gambling-related games, like SCGs, vary with respect to age restrictions and their enforcement (39–41). Gambling-related games without monetary wagering typically do not fulfill legal criteria for gambling (39, 40). Access to land-based or online video, amusement, and slot machines may have ambiguous age restrictions, and children under 16 years old sometimes have legal access (41). A Canadian sample of youth in grades 9–12 found 12.4% had played SCGs in the past 3 months. These youth were more prevalently classified as experiencing problem gambling (18). A similar study in the United States found that ~10% of adolescent gamblers reported gambling at a casino, with estimates of 40% among those with gambling problems (42). In a Hong Kong school-based survey, 71.4% of individuals who gambled online reported earlier participation in games on free-to-play websites. These individuals were likely to view gambling as safe and healthy entertainment (36). However, free-to-play gambling-related games have been linked to gambling for money and problem gambling in youth (14, 16, 22, 43). Furthermore, microtransactions in simulated gambling-related games have been associated with subsequent gambling (35, 42). However, more longitudinal research is needed.

Forms of gambling may be incorporated into videogames and vice versa, blurring boundaries (20, 43). For example, some governmental and regulatory bodies consider loot boxes as gambling elements in videogames (44). Individuals who play videogames problematically have reported using online videogames and digital platforms to gamble (45). For example, some in-game items (even non-game-enhancing, cosmetic ones) may be exchanged for significant real-world money (46). Loot boxes, skins, and other random-chance features are considered to have similarities to gambling. These are found in games deemed suitable for youth as young as 8-years-old (47). Among the top 100 grossing videogames, loot boxes were prevalent, especially on mobile platforms, with these videogames often available to children 12 years or older (48).

Videogaming features such as loot boxes (19, 48–51) and skins betting (20) may be gateways to gambling and gambling problems in youth. Youth participating in skins betting and gambling may be at elevated risk for gambling-related harms (20, 48). A qualitative analysis of 16- to 18-year-olds who purchased loot boxes suggested that reasons for purchases were similar to reasons for engaging in gambling (51). These included wanting to advance in videogames more quickly, raising money, excitement, and escaping from stress (19, 51). Such findings indicate that age restrictions and harm-reduction measures should be considered for videogames that contain gambling/gambling-like elements. Healthcare professionals should understand the natures of videogames played in relation to their clients'/patients' lives (44). Contexualizing youth videogaming and gambling may be critical in preventing online gambling problems (14).

The role of virtual communities for gambling and videogaming should be considered during prevention and treatment of gambling/videogaming problems, especially for women (52). Identification within virtual communities may considerably influence in-game spending behaviors (52). Additional input is needed from game developers and rating boards (50). Online videogaming and gambling providers could take proactive roles in identifiying and excluding gambling youth. Similar approaches may be applicable to identifying, intervening and limiting at-risk gambling/videogaming (31). Providers could also include links to online counseling, peer-support chats, educational materials, and virtual communities that may serve as protection against excessive use (31, 52). Policymakers could consider placing limits on chance-items and use other controls that are traditionally used in gambling settings to limit youth spending and prevent youth engagement (49, 50, 53, 54). Additional harm-reduction measures are discussed below.

Effectiveness of Age Restrictions as a Harm-Reduction Measure

Limited research exists on the effectiveness of age restrictions on youth gambling, despite theoretical support (55). While age restrictions may prevent problem gambling or related harms (56–58), their effectiveness have largely been untested. Effectiveness of legal age limits appears largely inferred based on worldwide implementation (58). However, a global solution may be unfeasible. Customers typically prefer easy access, gambling and videogaming corporations are often profit-driven, and many governments take some revenue either directly or indirectly through taxation from gambling (58). Therefore, harm reduction or prevention of problem gambling by limiting the number of customers and the profits from these customers may not be the first solution considered.

Effectiveness of age restrictions on gambling may be influenced by public awareness and enforcement. A Finnish study found that teacher awareness for the minimum legal age of gambling was not as accurate as for purchasing alcohol, purchasing cigarettes, or driving a car (59). Similarly, in Canada, youth gambling was viewed as requiring less attention than other risk behaviors by teachers (60) and parents (61). With social acceptance of gambling, few caregivers may be aware of potential risks of early gambling onset (61). Underaged youth often participate in illegal gambling despite age restrictions (36, 41, 62, 63). Infringements against or disregard for age restrictions appear more common among males (64).

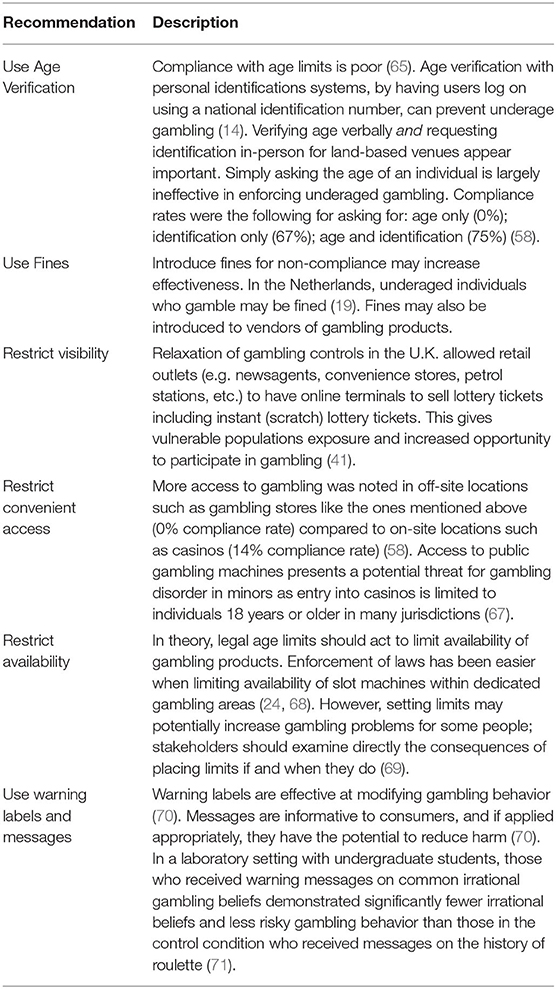

As with tobacco and alcohol, age restrictions are only effective when rigorously enforced (55, 65). There currently appears to be inadequate enforcement of age restriction regulations across multiple gambling activities (24, 41, 66). Enforcing age restrictions for online gambling may be particularly difficult. Underaged individuals who gamble may be committing credit card fraud or are being supported by older friends and relatives to gamble online (31, 36). There are currently few safeguards to protect underaged individuals from gambling, and there have been calls for strict verification systems to be implemented (15, 36). Strategies used to enforce age restriction for in-person gambling may work for online gambling, although challenges exist in applicability (Table 1).

Raising Age Minimums

Research examining effectiveness of raising legal ages for gambling is limited; however, a review suggests that raising minimal ages may reduce gambling-related harms (72). Finnish studies examined effects of raising the legal minimum age to gamble from 15 to 18 years with an interest in protecting youth from gambling-related harms (55, 68, 73, 74). Unsurprisingly, 18-year-olds who were not targeted by the age increase showed no significant changes in gambling activity (74). The intervention was successful in reducing lottery and slot-machine gambling for the 15- to 17-year-old age group and, interestingly, also the 18- to 19-year-old age group 3 years post-legislation (73). Nonetheless, underaged gambling was still occurring in about 13% of youth (55). Online gambling for all age groups, except for underaged 15- to 17-year-olds, increased. Online gambling was rare in the 15–17 age group [4%] (68), perhaps related to difficulties in obtaining credit cards to gamble.

In sum, the Lotteries Act enacted in Finland on October 1, 2010 that raised the minimum age limit for gambling from 15 to 18 years of age helped decrease adolescent gambling and problem gambling between 2011 and 2015 (59). Teens who were still gambling experienced significantly less gambling-related harms 6 years after raising the age minimum (73). Therefore, negative consequences experienced by youth from gambling may be less prevalent after raising the age minimum (74). Follow-up is required to examine longer-term effects, especially on online gambling.

Warning Labels

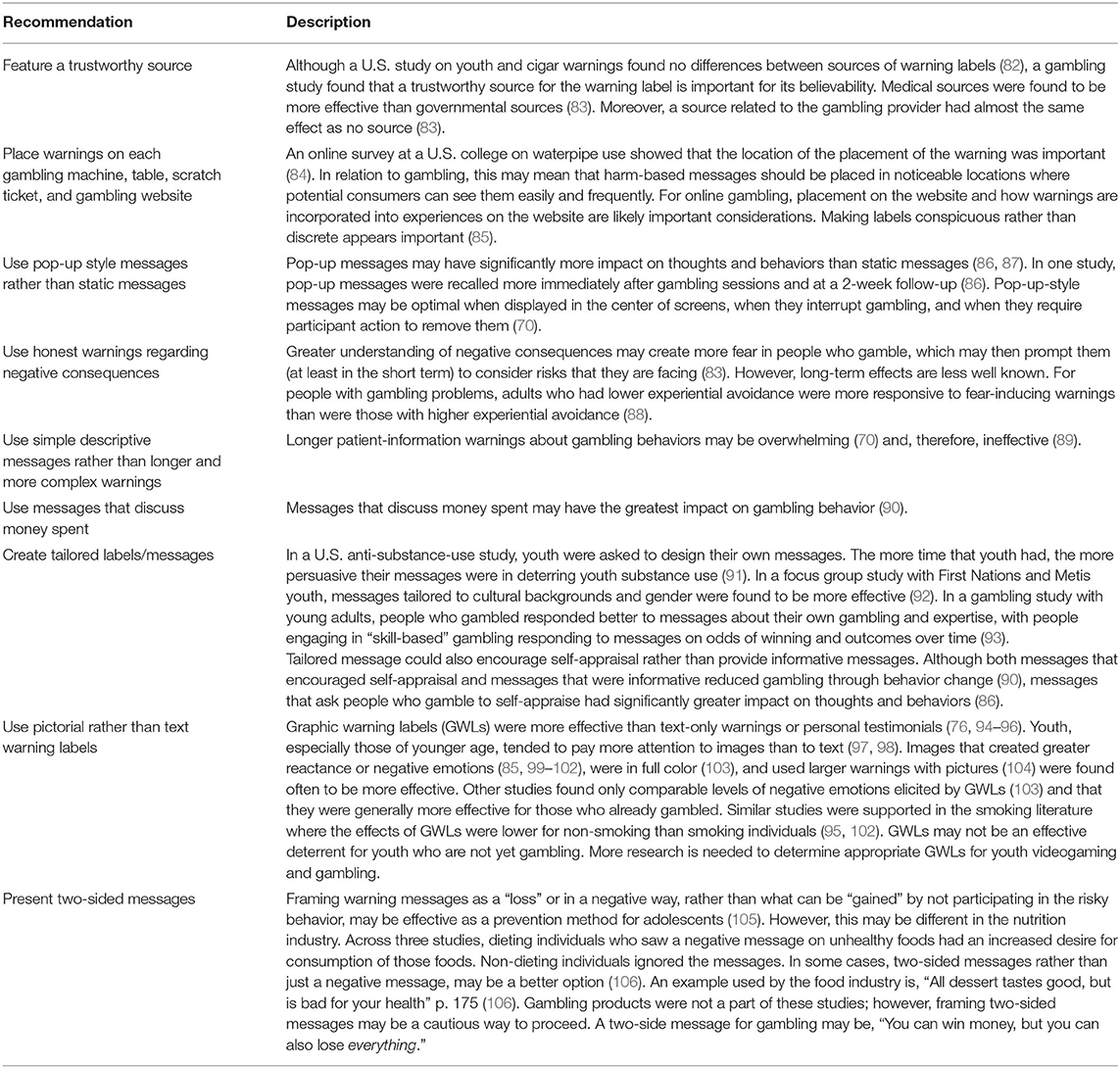

Warning labels and advertising may reduce youth online gambling (75). However, few studies have examined intervention effectiveness in real-world gambling settings (76). Consumers do not appear “desensitized” to multiple warning messages (77, 78). Increased exposure to warnings may be beneficial in preventing youth online gambling. Also, providing only knowledge about gambling on warning labels does not necessarily impact gambling behavior. When gambling odds were on warning messages to alter irrational beliefs about winning, gambling behavior did not change significantly (79). A study with students (ages 14–17 years) found age-related warning labels with highly caffeinated food and drinks were similarly ineffective (80). In some cases, warning labels increased appeal of products (56% for videogames) (81). Gambling products were not part of this study, and therefore, it is uncertain whether such warnings on gambling products would increase gambling appeal to youth. Warning-label features that may be applicable to online youth gambling are discussed in Table 2.

Advertising and Education

Advertising and promotion of educational interventions warrant further study (14, 15). Interventions targeting youth gambling may fail without public awareness. When Finland raised age restrictions on gambling, mass media campaigns increased awareness and supported changes (55). Campaigns may use gambling websites, radio, physical posters in public spaces, online news, and social media platforms (31, 55). Conscientious marketing may help prevent under-aged involvement in online poker (16), especially when visibility of gambling advertisements contributes to people experiencing increased gambling accessibility (14). A UK study found harm-reduction messages were less visible than advertising (107). Recommendations for gambling advertising include:

1. Restricting advertising of online gambling (68, 108);

2. Including warning messages on all advertising and promotional materials (36);

3. Prohibiting marketing that targets underaged or vulnerable populations (73). This last point involves not depicting youth or people who look underaged participating in gambling activities (109, 110) and not implicitly or explicitly directing advertising at them (110). Increased education regarding risks should also be included in a comprehensive policy approach and harm-reduction guidelines (111).

While it may be nearly impossible to regulate all forms of online gambling, harm reduction in the form of educational awareness may help. Mass media campaigns and educational material that can inform youth of negative health effects could be implemented (31, 75, 108). Education to promote awareness of gambling risks could be implemented in schools and colleges, and incorporated into school curricula to prevent youth gambling and future gambling problems (31, 72, 112). Informational websites with links to treatment services and warnings to family/friends against providing funds to support youth gambling should also be considered (14, 36).

Limitations

This perspective paper provides a narrative overview of literature related to online youth and young adult gambling and age restrictions. Online gambling may change as videogaming and gambling converge and new technologies are developed (113). Although this paper began as rapid review on age restrictions and warning labels for youth, additional literature was cited to contextualize youth online gambling. This paper should not be considered a comprehensive critical description of the entire literature.

Conclusions

From the reviewed studies, there appears to be widespread adoption of legal age restrictions on gambling; however, studies of effectiveness pertaining specifically to online gambling appear limited. This may reflect indirect effects of harm-reduction regulations that primarily aim to denormalize and prevent youth from learning of financial and social rewards through gambling (114, 115). Enforcement of age restrictions, however, is another challenge. Future work surrounding prevention and harm reduction in online gambling should longitudinally examine optimal age restrictions and how they may be best enforced across the internet, considering adolescent/youth development. Current age restrictions should be consistently enforced to understand better their effects. In addition, further research is needed to reduce harms related to youth online gambling and gambling-related features in videogames. Early adoption of harm reduction measures including higher age restrictions for online gambling and for videogames with gambling-related features may be beneficial.

Evidence from research in gambling and related fields suggests that warning labels that simply state “age restricted” may not deter youth or may even increase appeal. Effective warning labels should consider tailored, strong, and colorful graphics that depict negative consequences of gambling. Messages that are simple and concise from a reliable source such as a medical organization may be effective with some youth. Balanced messages that tell two sides of the story (both positive and negative aspects of online gambling), are honest about negative consequences, discuss money spent, or encourage-self appraisal may also deter youth online gambling. Finally, youth may not become desensitized to warning labels and may require reminders as refreshments. Placing pop-up warning labels in noticeable areas where youth and other vulnerable populations may gamble online could be effective. However, direct examination of the effectiveness of each of these approaches for youth online gambling is needed.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

JS wrote the first draft of the paper and worked with the other co-authors on subsequent drafts. All authors contributed to the editorial process and have approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

MP's involvement was supported by the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling.

Conflict of Interest

MC serves on the advisory board of a veteran-serving organization focusing on video games and mental health. She is the CEO and founder of Gaming and Wellness Association, Inc., a non-profit dedicated to research and education about healthy video game play. MP has consulted for and advised Game Day Data, the Addiction Policy Forum, AXA, Idorsia, and Opiant/Lakelight Therapeutics; received research support from the Veteran's Administration, Mohegan Sun Casino, and the National Center for Responsible Gaming (no the International Center for Responsible Gambling); participated in surveys, mailings, or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse-control disorders or other health topics; consulted for law offices and the federal public defender's office in issues related to impulse-control and addictive disorders; provided clinical care in the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Problem Gambling Services Program; performed grant reviews for the National Institutes of Health and other agencies; edited journals and journal sections; given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events and other clinical/scientific venues; and generated books or chapters for publishers of mental health texts. The other authors report no disclosures. The views presented in this manuscript represent those of the authors. NT has received funding from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, and Gambling Research Exchange. He has also acted as a consultant on gambling problems for various government and legal entities. He has received grant funding from the Ontario Lottery and Gaming (the crown corporation that manages gambling in Ontario) to evaluate one of their prevention initiatives, but otherwise has not received funding from the gambling industry. The contract included guarantees of independence and intellectual property rights for the researcher.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This paper was based in part on a published report that was commissioned by the Gambling Research Exchange Ontario and can be found at: https://doi.org/10.33684/2020.002. However, it has been significantly changed to reflect the current state of harm reduction for online gambling in youth.

Footnotes

1. ^Loot boxes are videogame features (often in the shape of a box) available in many game genres that one can find or purchase. They often contain a seemingly random mix of items, ranging from common to rare items. The rarer the item, the more valuable it typically is in the game. In some cases, a loot box may be found in-game but requires a key to open it—this key may be purchased or earned. A distinction from gambling is that loot boxes can create monetary losses but typically no monetary gains.

2. ^Skins in videogames change the appearance of an item or character. For example, a skin may give your gun camouflage coloring, or give it the appearance of flames. Skins can be obtained through loot boxes, earned during gameplay, purchased with virtual currency and/or purchased with real money. For some videogames, skins become a valuable commodity that can be sold or used to place bets with on third-party websites.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

2. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases. 11th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization (2019).

3. Calado F, Alexandre J, Griffiths MD. Prevalence of adolescent problem gambling: a systematic review of recent research. J Gambl Stud. (2017) 33:397–424. doi: 10.1007/s10899-016-9627-5

4. Turner NE, Cook S, Shi J, Elton-Marshall T, Hamilton H, Ilie G, et al. Traumatic brain injuries and problem gambling in youth: evidence from a population-based study of secondary students in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0239661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239661

5. Volberg RA, Gupta R, Griffiths MD, Olason DT, Delfabbro P. An international perspective on youth gambling prevalence studies. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2010) 22:3–38. doi: 10.1515/9783110255690.21

6. Griffiths MD, Parke J. Adolescent gambling on the internet: a review. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2010) 22:59–75.

7. Floros G, Paradisioti A, Hadjimarcou M, Mappouras DG, Karkanioti O, Siomos K. Adolescent online gambling in cyprus: associated school performance and psychopathology. J Gambl Stud. (2015) 31:367–84. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9424-3

8. Langham E, Thorne H, Browne M, Donaldson P, Rose J, Rockloff M. Understanding gambling related harm: a proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health. (2016) 16:80. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2747-0

9. Abbott M, Binde P, Clark L, Hodgins D, Johnson M, Manitowabi D, et al. Conceptual Framework of Harmful Gambling: An International Collaboration. 3rd ed. Guelph, ON: Gambling Research Exchange Ontario (GREO) (2018).

10. Roberts A, Sharman S, Landon J, Cowlishaw S, Murphy R, Meleck S, et al. Intimate partner violence in treatment seeking problem gamblers. J Fam Violence. (2020) 35:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s10896-019-00045-3

11. Dighton G, Roberts E, Hoon AE, Dymond S. Gambling problems and the impact of family in UK armed forces veterans. J Behav Addict. (2018) 7:355–65. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.25

12. Kessler RC, Hwang I, Labrie R, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Winters KC, et al. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the national comorbidity survey replication. Psychol Med. (2008) 38:1351–60. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900

13. Jacob L, Haro JM, Koyanagi A. Relationship between attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and problem gambling: a mediation analysis of influential factors among 7,403 individuals from the UK. J Behav Addict. (2018) 7:781–91. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.72

14. Kristiansen S, Trabjerg CM. Legal gambling availability and youth gambling behaviour: a qualitative longitudinal study. Int J Soc Welf. (2017) 26:218–29. doi: 10.1111/ijsw.12231

15. Potenza MN, Balodis IM, Derevensky J, Grant JE, Petry NM, Verdejo-Garcia A, et al. Gambling disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2019) 5:51. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0099-7

16. Parke A, Griffiths MD. Identifying risk and mitigating gambling-related harm in online poker. J Risk Res. (2018) 21:269–89. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2016.1200657

17. Derevensky JL, Gainsbury SM. Social casino gaming and adolescents: should we be concerned and is regulation in sight? Int J Law and Psychiatry. (2016) 44:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2015.08.025

18. Veselka L, Wijesingha R, Leatherdale ST, Turner NE, Elton-Marshall T. Factors associated with social casino gaming among adolescents across game types. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:1167. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6069-2

19. Rockloff M, Russell AMT, Greer N, Lolé L, Hing N, Browne M. Loot Boxes: Are They Grooming Youth for Gambling? NSW Responsible Gambling Fund. Central Queensland University (2020). doi: 10.25946/5ef151ac1ce6f

20. Wardle H. The same or different? Convergence of skin gambling and other gambling among children. J Gambl Stud. (2019) 35:1109–25. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09840-5

21. Hilbrecht M, Baxter D, Abbott M, Binde P, Clark L, Hodgins DC, et al. The conceptual framework of harmful gambling: a revised framework for understanding gambling harm. J Behav Addict. (2020) 9:190–205. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00024

22. Wijesingha R, Leatherdale ST, Turner NE, Elton-Marshall T. Factors associated with adolescent online and land-based gambling in Canada. Addict Res Theory. (2017) 25:525–32. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2017.1311874

24. Castren S, Basnet S, Pankakoski M, Ronkainen J-E, Helakorpi S, Uutela A, et al. An analysis of problem gambling among the Finnish working-age population: a population survey. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:519. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-519

25. Magoon ME, Gupta R, Derevensky J. Juvenile delinquency and adolescent gambling. Implications for the Juvenile Justice System. Am Assoc Correctional Forensic Psychol. (2019) 32:690–713. doi: 10.1177/0093854805279948

26. Turner NE, Littman-Sharp N, Zangeneh M. The experience of gambling and its role in problem gambling. Int Gambl Stud. (2006) 6:237–66. doi: 10.1080/14459790600928793

27. Rahman AS, Pilver CE, Desai RA, Steinberg MA, Rugle L, Suchitra K-S, et al. The relationship between age of gambling onset and adolescent problematic gambling severity. J Psychiatr Res. (2012) 46:675–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.007

28. Livazovic G, Bojcic K. Problem gambling in adolescents: what are the psychological, social and financial consequences? BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19:308. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2293-2

29. Derevensky JL, Gilbeau L. Adolescent gambling: twenty-five years of research. Can J Addict. (2015) 6:4–12. doi: 10.1097/02024458-201509000-00002

30. Hardoon KK, Gupta R, Derevensky JL. Psychosocial variables associated with adolescent gambling. Psychol Addict Behav. (2004) 18:170–9. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.170

31. Hume M, Mort GS. Fun, friend, or foe: youth perceptions and definitions of online gambling. Soc Mar Q. (2011) 17:109–33. doi: 10.1080/15245004.2010.546939

32. Kaminer V, Petry NM. Gambling behavior in youths: why we should be concerned. Psychiatr Serv. (1999) 50:167–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.2.167

33. Council RG. Gambling & Young Adults: OLG. (2020). Available online at: https://www.responsiblegambling.org/for-the-public/safer-play/gambling-and-young-adults/ (accessed February 18, 2020).

34. Olason DT, Kristjansdottir E, Einarsdottir H, Haraldsson H, Bjarnason G, Derevensky JL. Internet gambling and problem gambling among 13 to 18 year old adolescents in Iceland. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2011) 9:257–63. doi: 10.1007/s11469-010-9280-7

35. Mcbride J, Derevensky J. Internet gambling and risk-taking among students: an exploratory study. J Behav Addict. (2012) 1:50–8. doi: 10.1556/JBA.1.2012.2.2

36. Wong ILK, So EMT. Internet gambling among high school students in Hong Kong. J Gambl Stud. (2014) 30:565–76. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9413-6

37. Canale N, Griffiths MD, Vieno A, Siciliano V, Molinaro S. Impact of internet gambling on problem gambling among adolescents in Italy: findings from a large-scale nationally representative survey. Comput Human Behav. (2016) 57:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.020

38. Potenza MN, Wareham JD, Steinberg MA, Rugle L, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S, et al. Correlates of at-risk/problem internet gambling in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. (2011) 50:150–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.11.006

39. Meyer G, Brosowski T, von Meduna M, Hayer T. Simulated gambling: analysis and synthesis of empirical findings on games in internet-based social networks, in the form of demo versions, and computer and video games. Zeitschrift fur Gesundheitspsychologie. (2015) 23:153–68. doi: 10.1026/0943-8149/a000144

40. Rose I. Gambling and the Law®: an introduction to the law of internet gambling. UNLV Gaming Res Rev J. (2006) 10:443–4. doi: 10.1089/glr.2006.10.443

41. Pugh P, Webley P. Adolescent participation in the U.K. National Lottery games. J Adolesc. (2000) 23:1–11. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0291

42. Yip SW, Desai RA, Steinberg MA, Rugle L, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S, et al. Health/functioning characteristics, gambling behaviors, and gambling-related motivations in adolescents stratified by gambling problem severity: findings from a high school survey. Am J Addict. (2011) 20:495–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00180.x

43. King DL, Delfabbro PH, Kaptsis D, Zwaans T. Adolescent simulated gambling via digital and social media: an emerging problem. Comput Human Behav. (2014) 31:305–13. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.048

44. Zendle D, Bowden-Jones H. Loot boxes and the convergence of video games and gambling. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:724–5. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30285-8

45. Shi J, Renwick R, Turner NE, Kirsh B. Understanding the lives of problem gamers: the meaning, purpose, and influences of video gaming. Comput Human Behav. (2019) 97:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.023

46. Xiao LY. Which Implementations of Loot Boxes Constitute Gambling? A UK legal perspective on the potential harms of random reward mechanisms. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2020). doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00372-3

47. King DL, Delfabbro PH, Derevensky JL, Griffiths MD. A review of Australian classification practices for commercial video games featuring simulated gambling. Int Gambl Stud. (2012) 12:231–42. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2012.661444

48. Zendle D, Meyer R, Cairns P, Waters S, Ballou N. The prevalence of loot boxes in mobile and desktop games. Addiction. (2020) 115:1768–72. doi: 10.1111/add.14973

49. Kristiansen S, Severin MC. Loot box engagement and problem gambling among adolescent gamers: findings from a national survey. Addict Behav. (2020) 103:106254. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106254

50. Zendle D, Cairns P. Loot boxes are again linked to problem gambling: results of a replication study. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0213194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213194

51. Zendle D, Meyer R, Over H. Adolescents and loot boxes: links with problem gambling and motivations for purchase. R Soc Open Sc. (2019) 6:190049. doi: 10.1098/rsos.190049

52. Sirola A, Savela N, Savolainen I, Kaakinen M, Oksanen A. The role of virtual communities in gambling and gaming behaviors: a systematic review. J Gambl Stud. (2020). doi: 10.1007/s10899-020-09946-1. [Epub ahead of print]

53. Drummond A, Sauer JD, Hall LC. Loot box limit-setting: a potential policy to protect video game users with gambling problems? Addiction. (2019) 114:935–6. doi: 10.1111/add.14583

54. King DL, Delfabbro PH. Loot box limit-setting is not sufficient on its own to prevent players from overspending: a reply to Drummond, Sauer & Hall. Addiction. (2019) 114:1324–5. doi: 10.1111/add.14628

55. Raisamo S, Warpenius K, Rimpela A. Changes in minors' gambling on slot machines in Finland after the raising of the minimum legal gambling age from 15 to 18 years: a repeated cross-sectional study. Nord Stud Alcohol Drugs. (2015) 32:579–90. doi: 10.1515/nsad-2015-0055

56. Götestam KG, Johansson A. Norway. In: Meyer G, Hayer T, Griffiths M, editors. Problem Gambling in Europe: Challenges, Prevention, and Interventions. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media US (2009).

57. Mann K, Lemenager T, Zois E, Hoffmann S, Nakovics H, Beutel M, et al. Comorbidity, family history and personality traits in pathological gamblers compared with healthy controls. Eur Psychiatry. (2017) 42:120–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.12.002

58. Gosselt JF, Neefs AK, van Hoof JJ, Wagteveld K. Young poker faces: compliance with the legal age limit on multiple gambling products in the Netherlands. J Gambl Stud. (2013) 29:675–87. doi: 10.1007/s10899-012-9335-8

59. Castren S, Temcheff CE, Derevensky J, Josefsson K, Alho H, Salonen AH. Teacher awareness and attitudes regarding adolescent risk behaviours: a sample of Finnish middle and high school teachers. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2017) 15:295–311. doi: 10.1007/s11469-016-9721-z

60. Derevensky JL, St-Pierre RA, Temcheff CE, Gupta R. Teacher awareness and attitudes regarding adolescent risky behaviours: is adolescent gambling perceived to be a problem? J Gambl Stud. (2014) 30:435–51. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9363-z

61. Campbell C, Derevensky J, Meerkamper E, Cutajar J. Parents' perceptions of adolescent gambling: a Canadian national study. J Gambl Issues. (2011) 36:36–53. doi: 10.4309/jgi.2011.25.4

62. Wood RT, Griffiths MD. The acquisition, development and maintenance of lottery and scratchcard gambling in adolescence. J Adolesc. (1998) 21:265–73. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0152

63. Wong ILK. Internet gambling: a school-based survey among Macau students. J Soc Behav Pers. (2010) 38:365–71. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2010.38.3.365

64. Jonsson J, Rönnberg S. Sweden. In: Meyer G, Hayer T, Griffiths M, editors. Problem Gambling in Europe: Challenges, Prevention, and Interventions. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media US (2009).

65. Warpenius K, Holmila M, Raitasalo K. Compliance with the legal age limits for alcohol, tobacco and gambling – a comparative study on test purchasing in retail outlets. Drugs-Educ Prev Polic. (2016) 23:435–41. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2016.1141875

66. Frank ML. Underage gambling in Atlantic City casinos. Psychol Rep. (1990) 67:907–12. doi: 10.2466/PR0.67.7.907-912

67. Macur M, Makarovic˘ M, Ronc˘evic' B. Slovenia. In: Meyer G, Hayer T, Griffiths M, editors. Problem Gambling in Europe: Challenges, Prevention, and Interventions. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media US (2009).

68. Salonen A, Raisamo S. Suomalaisten rahapelaaminen 2015. Rahapelaaminen, rahapeliongelmat ja rahapelaamiseen liittyvät asenteet ja mielipiteet 15–74-vuotiailla. (Finnish gambling 2015. Gambling, gambling problems, and attitudes and opinions on gambling among Finns aged 15–74, with English abstract) (2015).

69. Ladouceur R, Shaffer P, Blaszczynski A, Shaffer HJ. Responsible gambling: a synthesis of the empirical evidence. Addict Res Theory. (2017) 25:225–35. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2016.1245294

70. Ginley MK, Whelan JP, Pfund RA, Peter SC, Meyers AW. Warning messages for electronic gambling machines: evidence for regulatory policies. Addict Res Theory. (2017) 25:495–504. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2017.1321740

71. Floyd K, Whelan JP, Meyers AW. Use of warning messages to modify gambling beliefs and behavior in a laboratory investigation. Psychol Addict Behav. (2006) 20:69–74. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.1.69

72. Williams RJ, West BL, Simpson RI. Prevention of Problem Gambling: A Comprehensive Review of the Evidence, and Identified Best Practices. Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (2012).

73. Nordmyr J, Osterman K. Raising the legal gambling age in Finland: problem gambling prevalence rates in different age groups among past-year gamblers pre- and post-implementation. Int Gambl Stud. (2016) 16:347–56. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2016.1207698

74. Raisamo S, Kinnunen JM, Pere L, Lindfors P, Rimpela A. Adolescent gambling, gambling expenditure and gambling-related harms in Finland, 2011–2017. J Gambl Stud. (2019) 36:597–610. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09892-7

75. Elton-Marshall T, Wijesingha R, Kennedy RD, Hammond D. Disparities in knowledge about the health effects of smoking among adolescents following the release of new pictorial health warning labels. Prev Med. (2018) 111:358–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.11.025

76. Reilly C. Responsible Gambling: A Review of the Research. Beverly, MA: National Centre for Responsible Gaming (2017). Available online at: https://www.ncrg.org/sites/default/files/uploads/responsible_gambling_research_white_paper_1.pdf

77. Main KJ, Darke PR. Crying wolf or ever vigilant: do wide-ranging product warnings increase or decrease sensitivity to other product warnings? J Public Policy Mark. (2019) 39:62–75. doi: 10.1177/0743915619829730

78. White V, Bariola E, Faulkner A, Coomber K, Wakefield M. Graphic health warnings on cigarette packs: How long before the effects on adolescents wear out? Nicotine Tob Res. (2015) 17:776–83. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu184

79. Steenbergh TA, Whelan JP, Meyers AW, May RK, Floyd K. Impact of warning and brief intervention messages on knowledge of gambling risk, irrational beliefs and behaviour. Int Gambl Stud. (2004) 4:3–16. doi: 10.1080/1445979042000224377

80. Goldman J, Zhu Mo, Pham TB, Milanaik R. Age restriction warning label efficacy and high school student consumption of highly-caffeinated products. Prev Med Rep. (2018) 11:262–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.05.018

81. Goldman JM. Is the label “not recommended for children” a deterrent or dangerous attraction for teenagers? Pediatrics. (2018) 141:70. doi: 10.1542/peds.141.1_MeetingAbstract.70

82. Kowitt SD, Jarman K, Ranney LM, Goldstein AO. Believability of cigar warning labels among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. (2017) 60:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.10.007

83. Munoz Y, Chebat JC, Suissa JA. Using fear appeals in warning labels to promote responsible gambling among VLT players: the key role of depth of information processing. J Gambl Stud. (2010) 26:593–609. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9182-4

84. Islam F, Salloum RG, Nakkash R, Maziak W, Thrasher JF. Effectiveness of health warnings for waterpipe tobacco smoking among college students. Int J Public Health. (2016) 61:709–15. doi: 10.1007/s00038-016-0805-0

85. Lou C. Effects of conspicuity and integration of warning messages in social media alcohol ads: balancing between persuasion and reactance among underage youth (Dissertation). Nanyang Technological University (2017).

86. Monaghan S, Blaszczynski A. Impact of mode of display and message content of responsible gambling signs for electronic gaming machines on regular gamblers. J Gambl Stud. (2010) 26:67–88. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9150-z

87. Harris A, Griffiths MD. A critical review of the harm-minimisation tools available for electronic gambling. J Gambl Stud. (2017) 33:187–221. doi: 10.1007/s10899-016-9624-8

88. De Vos S, Crouch R, Quester P, Ilicic J. Examining the effectiveness of fear appeals in prompting help-seeking: the case of at-risk gamblers. Psychol Mark. (2017) 34:648–60. doi: 10.1002/mar.21012

89. Weiss-Cohen L, Konstantinidis E, Speekenbrink M, Harvey N. Task complexity moderates the influence of descriptions in decisions from experience. Cognition. (2018) 170:209–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2017.10.005

90. Gainsbury SM, Aro D, Ball D, Tobar C, Russell A. Optimal content for warning messages to enhance consumer decision making and reduce problem gambling. J Bus Res. (2015) 68:2093–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.03.007

91. Pena-Alves S, Greene K, Ray AE, Glenn SD, Hecht ML, Banerjee SC. “Choose today, live tomorrow”: a content analysis of anti-substance use messages produced by adolescents. J Health Commun. (2019) 24:592–602. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2019.1639858

92. Bottorff JL, Haines-Saah R, Oliffe JL, Struik LL, Bissell LJL, Richardson CP, et al. Designing tailored messages about smoking and breast cancer: a focus group study with youth. Can J Nurs Res. (2014) 46:66–86. doi: 10.1177/084456211404600106

93. Gainsbury SM, Abarbanel BLL, Philander KS, Butler JV. Strategies to customize responsible gambling messages: a review and focus group study. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:1381. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6281-0

94. Mutti S, Reid JL, Gupta PC, Pednekar MS, Dhumal G, Nargis N, et al. Perceived effectiveness of text and pictorial health warnings for smokeless tobacco packages in Navi Mumbai, India, and Dhaka, Bangladesh: findings from an experimental study. Tob Control. (2016) 25:437–43. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052315

95. Margalhos P, Esteves F, Vila J, Arriaga P. Emotional impact and perceived effectiveness of text-only versus graphic health warning tobacco labels on adolescents. Span J Psychol. (2019) 22:e17. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2019.20

96. Steier J. Investigation of the effects of graphic cigarette warning labels on youth and adult smoking behavior in Southeast Asia (Dissertation). City University of New York, NY, Unites States (2016).

97. Borzekowski DLG, Cohen JE. Young children's perceptions of health warning labels on cigarette packages: a study in six countries. J Public Health. (2014) 22:175–85. doi: 10.1007/s10389-014-0612-0

98. Kemp D, Niederdeppe J, Byrne S. Adolescent attention to disgust visuals in cigarette graphic warning labels. J Adolesc Health. (2019) 65:769–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.07.007

99. Mutti-Packer S, Reid JL, Thrasher JF, Romer D, Fong GT, Gupta PC, et al. The role of negative affect and message credibility in perceived effectiveness of smokeless tobacco health warning labels in Navi Mumbai, India and Dhaka, Bangladesh: a moderated-mediation analysis. Addict Behav. (2017) 73:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.04.002

100. Skurka C, Byrne S, Davydova J, Kemp D, Safi AG, Avery RJ, et al. Testing competing explanations for graphic warning label effects among adult smokers and non-smoking youth. Soc Sci Med. (2018) 211:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.06.035

101. Cho YJ, Thrasher JF, Swayampakala K, Yong HH, McKeever R, Hammond D, et al. Does reactance against cigarette warning labels matter? warning label responses and downstream smoking cessation amongst adult smokers in Australia, Canada, Mexico and the United States. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0159245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159245

102. Netemeyer RG, Burton S, Andrews JC, Kees J. Graphic health warnings on cigarette packages: the role of emotions in affecting adolescent smoking consideration and secondhand smoke beliefs. J Public Policy Mark. (2016) 35:124–43. doi: 10.1509/jppm.15.008

103. Byrne S, Greiner Safi A, Kemp D, Skurka C, Davydova J, Scolere L, et al. Effects of varying color, imagery, and text of cigarette package warning labels among socioeconomically disadvantaged middle school youth and adult smokers. Health Commun. (2019) 34:306–16. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1407228

104. Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control. (2011) 20:327–37. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630

105. Mays D, Hawkins KB, Bredfeldt C, Wolf H, Tercyak KP. The effects of framed messages for engaging adolescents with online smoking prevention interventions. Transl Behav Med. (2017) 7:196–203. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0481-5

106. Pham N, Mandel N, Morales AC. Messages from the food police: how food-related warnings backfire among dieters. J Assoc Consum Res. (2016) 1:175–90. doi: 10.1086/684394

107. Critchlow N, Moodie C, Stead M, Morgan A, Newall PWS, Dobbie F. Visibility of age restriction warnings, harm reduction messages and terms and conditions: a content analysis of paid-for gambling advertising in the United Kingdom. Public Health. (2020) 184:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.004

108. Escario J-J, Wilkinson AV. Exploring predictors of online gambling in a nationally representative sample of Spanish adolescents. Comput Human Behav. (2020) 102:287–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.002

109. Collins RL, Martino SC, Kovalchik SA, D'Amico EJ, Shadel WG, Becker KM, et al. Exposure to alcohol advertising and adolescents' drinking beliefs: role of message interpretation. Health Psychol. (2017) 36:890–7. doi: 10.1037/hea0000521

110. Johns RJ, Dale N, Lubna Alam S, Keating B. Impact of Gambling Warning Messages on Advertising Perceptions. Melbourne, VIC: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. (2017). Available online at: https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/impact-of-gambling-warning-messages-on-advertising-perceptions-62/

111. Wiggers D, Asbridge M, Baskerville NB, Reid JL, Hammond D. Exposure to caffeinated energy drink marketing and educational messages among youth and young adults in Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:642. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16040642

112. Todirita IR, Lupu V. Gambling prevention program among children. J Gambl Stud. (2013) 29:161–9. doi: 10.1007/s10899-012-9293-1

113. Shi J, van der Maas M, Turner NE, Potenza MN. Expanding on the multidisciplinary stakeholder framework to minimize harms for problematic risk-taking involving emerging technologies. J Behav Addict. (2020).

114. Messerlian C, Derevensky J, Gupta R. Youth gambling problems: a public health perspective. Health Promot Int. (2005) 20:69–79. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah509

Keywords: gambling, harm reduction, gaming, video games, addictive behavior, child, adolescent, Internet

Citation: Shi J, Colder Carras M, Potenza MN and Turner NE (2021) A Perspective on Age Restrictions and Other Harm Reduction Approaches Targeting Youth Online Gambling, Considering Convergences of Gambling and Videogaming. Front. Psychiatry 11:601712. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.601712

Received: 01 September 2020; Accepted: 28 December 2020;

Published: 25 January 2021.

Edited by:

Marie Grall Bronnec, Université de Nantes, FranceReviewed by:

Sari Castrén, National Institute for Health and Welfare, FinlandMorgane Guillou, CHRU Brest, France

Copyright © 2021 Shi, Colder Carras, Potenza and Turner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jing Shi, ai5zaGlAYWx1bS51dG9yb250by5jYQ==

Jing Shi

Jing Shi Michelle Colder Carras

Michelle Colder Carras Marc N. Potenza

Marc N. Potenza Nigel E. Turner

Nigel E. Turner