- 1Department of Clinical and Dynamic Psychology, Medicine and Psychology Faculty, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 2Harvard Medical School, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, United States

Introduction: Suicide is the outcome of a process starting with the experiences of an unbearable pain or hopelessness, passing from suicidal ideation and planning, to possible para-suicidal behaviors or actual attempts. Recent studies have evidenced the necessity to integrate approaches based on the identification of psychopathological diagnoses and other variables as possible predictors of suicidal conduct with a more clinically based approach. A clinical assessment is needed that focuses on the patients' mental state with respect to thoughts concerning death and suicide. In particular, a qualitative assessment of motivations underlying the suicidal process could represent an effective guide for clinicians engaged in the difficult field of preventing adolescents' suicidal gestures. Most instruments investigating the suicidal motivation are self-report measures, possibly resulting in a lack of sufficiently valid assessment of this area. In the present work, we present the Motivational Interview for Suicidality in Adolescence (MIS-A) aiming at identifying the motivational areas sustaining suicidal ideation and gestures in this phase of development.

Materials and Methods: The identification of the different areas derives from a thorough review of the empirical literature subsequently vetted by expert clinicians who selected specific reasons behind suicidal ideation and gesture.

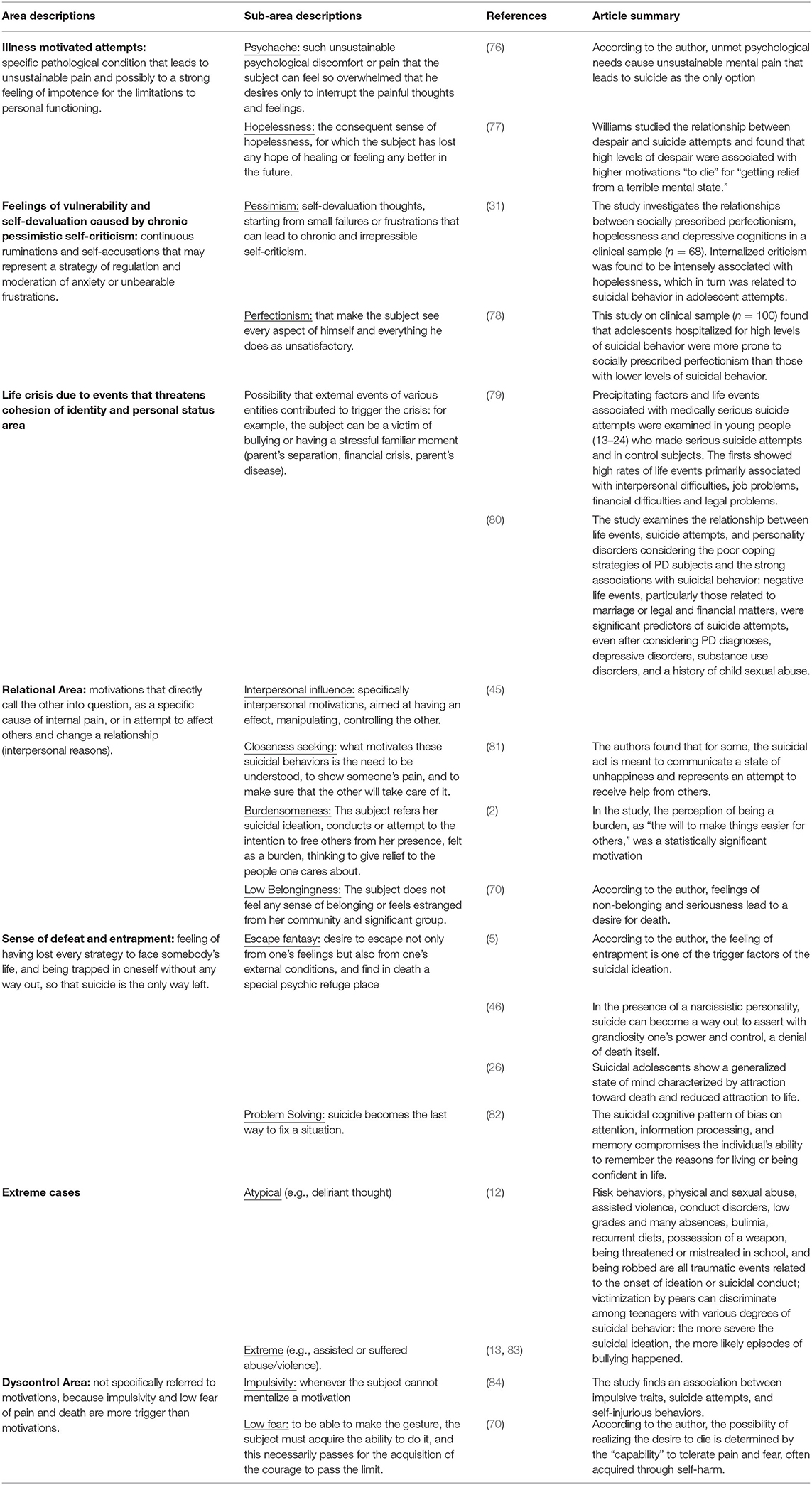

Result: The MIS is a semi-structured clinician-report interview. The interview is composed of seven areas and 14 sub-areas, evaluated on a four-point Likert scale: illness motivated attempts area, chronic presence of internal pessimistic criticism area, sense of defeat and entrapment area, relational area, external motivated crisis area, extreme and unusual cases area, and lack of control area.

Conclusions: The path followed in the creation of the MIS reflects both an empirically orientated and a clinically informed approach. Creating this MIS is the first step within a wider research project that will allow one to test the reliability of the instrument.

Introduction

Background

In epidemiological surveys, suicide represents the second cause of death in adolescence (1). Indeed, suicide management constitutes a dramatic challenge for any clinician and, in adolescence, there are many developmental issues that render this terrain even more uncertain to investigate in adolescence.

Configuration of Risk Factors in the Suicidal Process in Adolescence

In empirical approaches, suicidality is regarded as the product of the interaction of several risk factors (2), including distal, long-course factors and proximal precipitating factors (3). The configuration of distal and proximal risk factors in adolescence is only partially overlapping with adulthood. The distal risk factors that are common to both phases of life include familiarity for suicide, genetic predisposition (4), as well as psychosocial factors (4), and life events such as chronic physical illness, suicide within the family or peer group, experiencing physical or sexual abuse, and witnessing violence have been considered by many researchers in adolescence and adulthood (5–10). In adolescence, suicidal risk has been associated to substance abuse, truancy, poor school achievements, and sexual promiscuity (11–14). The presence of a psychiatric illness is associated with an increased suicidal risk with respect to non-clinical population (15–17). Autopsy studies evidenced that up to the 90% of suicidal subjects suffered from a psychiatric disorder in the period preceding the suicidal act (18). Although the methodological interpretation of these data remain controversial (18–20), autoptic evidence and retrospective studies show that 96% of adolescents who attempted suicide met criteria for an Axis I Psychiatric Disorder, with a specific role played by juvenile affective disorders and schizophrenia (16, 21–24), and it is evidenced that 14% of transgender adolescents report previous suicide attempts, a rate amounting to 50.8% in female transgender adolescents (25). It is also well documented that NSSI and hospitalization for previous suicide attempts are important predictors of future suicidal gestures in adolescence (26). The presence of specific personality disorders (27–29) may represent an activating factor, for stressful events (30–35), and a facilitating factor for the passage from suicidal ideation to suicidal conduct (36, 37). In adolescence, Cluster B personality disorders are the most significant predictors of suicide (29). Seventy-six percent of Borderline adolescent patients are reported to have attempted suicide (38) with a specific risk profile associated to the traits of impulsivity, affective dysregulation, interpersonal instability, and dissociated states of identity (39–44). Both clinical and research evidence indicates a role for narcissistic personality for both recurrence of suicidal ideation and lethality of suicidal attempts (45–48) and adolescence (49).

The assessment of such an array of factors is fundamental in the clinical management of suicidal risk, although it may prove incomplete and sometimes difficult to achieve in the clinical context of adolescence.

In the first place, not all psychiatric patients sharing the same diagnosis eventually commits suicide (50). Secondly, not all suicidal adolescents (not even adults) actually fall within a specific diagnostic category (18–20). In particular, in adolescence, many suicide attempts seem to occur in the absence of known risk factors (51–53). To our knowledge, there are no published randomized trials demonstrating that risk assessment can guide any suicide-reducing interventions able to reduce the overall prevalence of suicide in the assessed group (54). Thirdly, the assessment of those psychiatric conditions associated to suicidal risk may be undermined by their peculiarity requiring a long and careful window of observation (55). Furthermore, some adolescence psychopathological manifestations of affective and psychotic disorders may be difficult to differentiate from behavioral, psychic, and mood alternations characterizing adolescent development. Indeed, neurobiological and developmental research describe a number of maturational conditions that create a substrate of vulnerability for adolescence suicide. This developmental “background noise” may enhance suicidal risk through increased impulsivity, emotional liability, affective dysregulation, and sensation-seeking behaviors (56), as well as identity disturbance, lack of integration of bodily changes of puberty, ruptures of affective bonds, isolation and victimization from peers, academic failures, and threats to self-esteem (57–60). These considerations highlight the peculiarly challenging nature of suicidal prevention in adolescence, particularly in those clinical settings, such as emergency services, psychotherapy, or consultation, where a systematic and accurate assessment of risk factors cannot be easily guaranteed.

Finally, an additional difficulty arises from the inherent unpredictable nature of suicide. Current understanding interprets suicide as the possible outcome of a dynamic sequence (61). This staging model is supposed to begin with a motivational phase from which the early idea of self-death is gradually transformed into suicidal ideation to possibly end up the real suicidal intention planning and completion (3). Research efforts are now turning to the specific contribution of each risk factor for the different stages (54). Indeed, recent studies indicates that suicidal behavior and ideation are two different entities and do not share completely common risk factors (53, 54, 62).

The Study of the Suicidal Patients' State of Mind

The aforementioned reasons have led some researchers to highlight the need to monitor the patient's state of mind to more accurately follow up the unfolding of the suicidal process (3). Within this perspective, an important role seems to be played by the study of motivations for suicide. In this paper, we propose that correctly identifying the adolescent patient's subjectively perceived motivation for suicide can provide a phase-specific, clinically sensitive complementary approach for the study of suicidal risk. The aim of this study is to organize the knowledge for both researchers and clinicians in the field of adolescence suicidal risk to create an instrument of assessment of adolescents' suicidal motivation amenable for both research and clinical practice.

Measures that Investigate Motivations for Suicide

In order to achieve an empirically oriented approach for the study of suicidal motivation, an analysis of the research literature in the field has been carried out. Among the classic studies, Brancroft et al. (63) examined the responses of an adult sample of attempters who had been asked to choose among a list of possible motivations for suicide. The most frequent answers were to die, to escape, or to find relief from a difficult situation, while interpersonal reasons were underrepresented. Similar results were obtained in adolescent samples, although clinicians and parents tended to provide more interpersonal motivations (64–66). A recent cross-cultural research from the University of Palo Alto (67) also evidenced the role of both intrapersonal and interpersonal motivations. Qualitative methods for investigating the reason behind suicide also include the study of notes left by suicidal subjects. In a large study on notes left by youth who died by suicide, the main reasons that emerged were personal suffering or a feeling of emptiness, which could stem from not finding their place in the world or from feeling defeated; heartbreak; feeling suicide as an imperative or as the only way out; and self-denigration (68).

Motivations for suicide have more rarely been investigated at a quantitative level (53, 69, 70). Until recently, the Reasons for Attempting Suicide Questionnaire (71) was used in most of the studies on suicidal motivations. The scale is organized into two factors: the Punitive/Manipulative factor and the Internal Perturbation factor. Even though some studies suggested a three-factor structure as a better fit (72), the two-factor structure was confirmed (73). A large study found a four-factor structure where the “last way out” was the principal factor. This scale presents some serious limitations: the results have not always been replicated, and the items do not cover all the areas that the literature considers relevant (74). More recently, a self-report measure was validated for adolescents: the Inventory of Motivations for Suicide Attempts (IMSA) (75). This instrument is based on the subject's retrospective evaluations as indicated by specific items. Although IMSA shows a strong link with the literature and solid psychometric bases, its self-report nature is possibly biased by the subjects' defenses. The latest instrument of assessment, the Motivations for Suicidal Behavior Scale (MSBS) (4), is a self-report measure including items derived by an early exploratory investigation into the motivations spontaneously provided by a convenience sample of suicidal attempters. This tool seems to have only a relative predictive clinical value.

Overall, the field of the study of suicidal motivation seems to stress the need (1) to overcome the possible subjective biases of self-report measures and (2) to include an empirically informed, phase-specific, and clinically grounded map of suicidal motivations (75).

Materials and Methods

The Motivational Interview for Suicidality

The Motivational Interview for Suicidality in Adolescence (MIS-A) is a semi-structured clinician-report interview overviewing the subjects' reported reasons for their suicidal gesture. The MIS-A focuses on the analysis of seven distinct motivational areas and related sub-areas. Detailed information regarding the reasons for ideation and suicide attempts in adolescence could help clinicians in managing this population, especially considering the greater amount of information provided by a semi-structured interview compiled by an expert, and therefore not subject to the self-report biases. Additionally, clinicians may benefit from a better understanding of the way patients process their distress and how they transform it into specific suicidal thoughts. Consequently, both taking into account the adolescent and the subsequent interventions would be more accurate in taking into account these aspects. Being able to identify reasons associated with more intense ideation or with more lethal attempts can also be central in terms of prevention and risk assessment.

Creating the Interview

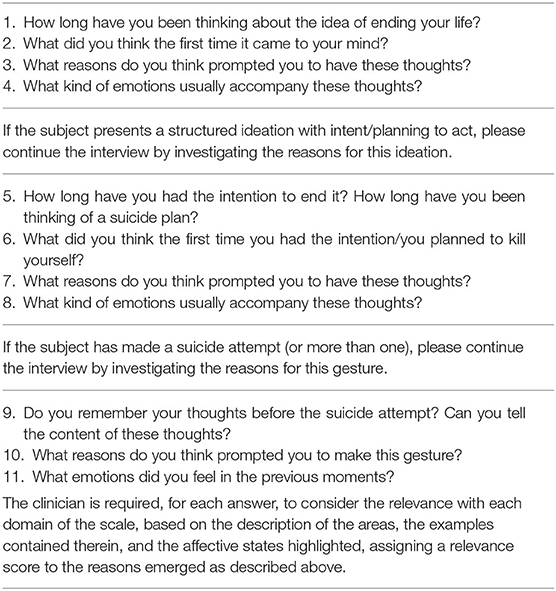

As a start, a review of the extant literature on suicidal motivation was performed on PUBMED selecting all articles including the words: “motivation + suicide + assessment” from 1980 to 2019. The research yielded 796 results. From this set of articles, a further selection was operated, excluding the following types of contributions: (a) anecdotal articles; (b) articles that consider motivation through general anthropological, sociological, and philosophical categories; (c) articles that did not distinguish between NSSI and suicide. At the end of this selection, 95 papers were chosen that focus on assessment tools, meaningful clinical reports, and clinical constructs that can describe the subjective motivations behind suicidal ideation and conducts. Articles concerning both adulthood (but not the third age) and adolescence were initially analyzed. In fact, the literature regarding the study of motivation in adolescence is limited, and only one tool entirely dedicated to motivation was validated in adolescence (75). Given the limited number of contributions, a further search was administered in the gray literature on motivations for suicide, using the same keywords and selecting the articles according to a criterion of relevance and consistency, adding 24 articles. Among these papers, the research group identified a number of keywords that could synthetically represent the main motivational areas considered by the empirical instruments (IMSA, RASQ) (73–75) as well as other relevant clinical constructs. The identification of these areas took place according to the principles of completeness (maximum inclusiveness) with respect to the literature examined and the mutual exclusivity of the areas selected (the relevant papers discussing each motivational area are presented in Table 1). For each of the areas a formal description of the motivation for suicide was produced, based on the definitions present in the literature (as in Table 1). In order to reach the main goal of building an instrument that is both clinically relevant and phase-sensitive, the definitions obtained were further articulated and refined in keeping with the research group background clinical knowledge and fundamental understanding of the adolescence developmental issues. In particular, empirical and clinical literature has indicated that in adolescence, suicidal fantasies can become a sort of refuge to which the subject constantly refers, and it is necessary to pay attention to all signs (85–89). A final step was then undertaken, by submitting the descriptions of any single motivational area to the judgement of five expert clinicians in the field of adolescence suicidal management. Any expert clinician was asked, in keeping with their own experience and knowledge, to evaluate the inclusivity, exclusivity, clarity, clinical relevance and phase sensitivity, and level of inference required for each description. Final modifications were then introduced adopting the expert clinicians' suggestions. The assessment is obtained through the clinical judgement of the patient's verbal answers to a semi-structured interview (Table 2).

Each area and sub-area of the MIS-A has been described by the four authors (MM, FC, WR, and ER) including aspects relating to the characteristic internal states, emotional experience, and relative examples. The clinician is asked to rate how relevant each motivational domain and sub-domain is on a Likert scale from 0 to 4, where 0 = not important, 1 = partially relevant, 2 = important but not predominant, 3 = very important, and 4 = predominant. A description of the areas and relative sub-areas is provided in Table 1.

It should be noted that, unlike other instruments of assessment in adolescence (for instance, the CDRS), the clinical judgment of the MIS-A does not rely on the objective assessments of symptoms, behavioral manifestations, and other relevant clinical signs. The assessment can do without other possibly relevant pieces of information that could be provided by parents, teachers, and other clinical observations. As discussed in the introduction, the study of the suicidal motivational state, by definition, can only be accomplished if one adheres to the patient's subjective perception and explicit narrative of emotional and ideational experience. In order to corroborate the structure and contents of the MIS-A, a reliability and validity study is being carried out that will include (a) an explorative and confirmatory factor analysis to corroborate the structure of the interview; (b) an inter-rater reliability assessment (Cohen's K); (c) a test of the stability of the construct through a test–retest procedure (r-Pearson); (d) a test of concurrent validity through matching with specific psychopathological conditions relevant for adolescent suicidality, namely, DSM-5 diagnosis by the Kiddie-SADS (90) and the SCID-II (91), and a test of predictive validity through the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (CSSRS) (92).

Result

Description of the Structure

The final version of the interview includes seven macro-areas divided into several sub-areas leading to a total of 15 categories of motivations. The “illness motivated attempts” macro-area refers to unsustainable pain and feelings of helplessness. The relative sub-areas are “psychache” (76), where the subject feels so overwhelmed that she only desires to interrupt the painful thoughts and feelings of anguish, pain emptiness, and sadness; and “hopelessness” (77), describing the loss of any hope of healing or recovering, or of being helped by anyone.

The second macro-area concerns motivations related to self-devaluating thoughts arising from minor failures, and resulting chronic feelings of shame, guilt, and frustration [the pessimism sub-area (31)] and feelings of inadequacy in every personal performance shame and irritability [perfectionism sub-area (78)].

The third macro-area concerns life crisis (79, 80) due to events that threaten the cohesion of identity and personal status, engendering feelings of worthlessness, loss of personal value, and failure.

The relational macro-area includes both interpersonal and intrapersonal reasons for suicide that refers to others. This macro-area is divided into four sub-areas: “interpersonal influence” (45), describing motivations aimed at having an effect on others, such as the fantasy of taking revenge or being triumphant in the anticipation of other's grief for the subject's own death; second, “closeness seeking” (81), which is a cry for help; third, “burdensomeness” (2) concerning subjects who refer their intention to free the meaningful others from their own suffering and unbearable presence; and fourth, “low belongingness” (70), characterized by feelings of estrangement from one's own community and/or significant group.

The “sense of defeat and entrapment” macro-area describes the condition of having lost every strategy to face existential challenges and feeling entrapped, with suicide being the only way out. The first sub-area describes a state of mind characterized by attraction toward death, felt as a special psychic refuge where anxieties and pain may come to an end [escape fantasy (5, 26, 46)]; the problem-solving sub-area (82) concerns the idea of suicide as an effective coping strategy to achieve control when other strategies have collapsed.

The “extreme and unusual cases” (12, 13, 25, 83) macro-area includes “atypical cases,” concerning less common reasons for suicide (e.g., thought disorders, dissociative states, emotional contagion, etc.), and the “extreme cases,” in which violence and sexual abuse (both endured, perpetrated, and witnessed), recent grief, abandonment, or severe deprivations are experienced.

The last macro-area does not specifically refer to explicit motivations for suicide. The clinician, in fact, needs to evaluate whether the subject reports having acted on impulse, without any precise reason or ideation [impulsivity sub-area (84)], or whether having acted without any concern for common feelings that accompany self-threatening behavior such as fear of death, pain, or sense of guilt [fearless conduct sub-area (70)].

Discussion

Suicidality constitutes a wide and uncertain field of study. Literature shows the difficulties encountered by clinicians in identifying the configuration of the various risk factors contributing to suicidal ideation and conducts. In this paper, the reasons were presented for an integrative and complementary approach of suicidal management based on the evaluation of the suicidal patient's subjective experience. This complementary approach relies on the monitoring of the patient's motivational state through diachronic development of the suicidal process. From an empirical and clinical point of view, the study of motivation for suicide may prove useful in describing the pathway leading from specific risk conditions to mental experience engendering the wish to die and, eventually, anti-conservative behaviors. In fact, literature describes the extreme emotional distress caused by some psychopathological or life events, but little is known about how these overwhelming states are organized into volitional states sustaining suicidality. The suicidal process is influenced by the individual response to the psychache induced by the diverse risk factors. The individual response is, on its turn, shaped on specific defense and coping styles, strategies of affective self-regulation and help-seeking behaviors, and personality organization. We contend that the study of suicidal motivation affords an overall view on the transformation of the psychache according to the individual mental capacities. MIS-A is meant to be a probe for the assessment of a set of mental conditions and capacities, as represented by specific motivations, affecting the various stages of the suicidal process. In order to support this statement, a research plan is being carried out, to ascertain the possible recurrent links between psychopathological conditions and personality disorders, on the one hand, and suicidal motivations. The mediating role of motivational states on the causal link between the psychopathological and personality risk factors and the diverse stage of the suicidal process is also under scrutiny. As said, the clinical context of assessment of adolescence suicidal risk does not always allow for a thorough analysis of relevant objective risk factors. This may be true for psychotherapists and clinical consultants as well as for clinicians working in inpatient units or day hospital services exposing these. Indeed, the condition of uncertainty rooted in the clinical management of suicidal risk is wont to determine a massive distress in the mental health professionals, potentially affecting the quality of the clinical response (93). In general, the suicidal process has to be regarded as a dynamic sequence in which the possibility to monitor the volitional component as subjectively perceived by the suicidal subject can be really sensitive in differentiating the patients who remain in the ideational stage from those more at risk of evolving into actual suicidal behaviors. The formal application of the MIS-A in a research context can provide an important grid of reference that may further be employed by clinicians also at a more informal and flexible level in the diverse clinical settings.

Conclusions

The creation of the MIS-A is meant to respond to the need to (a) assess the mental processes and personality functioning influencing suicidality in this phase of life; (b) integrate an approach based on the survey of risk factors, with a point of view that allows for a constant clinical monitoring of the patient's mental state in the dynamic development of the suicidal risk; (c) create a framework of reference for the study of the suicidal process that can be applied to clinical contexts that often prevent the professional from performing a thorough and systematic assessment of the adolescent suicidal patients; (d) provide mental health professionals with the possibility to have more interpretative categories in the burdensome work of management of adolescent suicide.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

MM, CF, RW, and ER contributed to conception and design of the study. MM, CF, and RW wrote sections of the manuscript. ER supervised all sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research received a specific grant from Sapienza University of Rome: protocol number AR11916B88EE22AD.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. Geneva: World Health Organization (2014).

2. Hayashi N, Igarashi M, Imai A, Yoshizawa Y, Asamura K, Ishikawa Y, et al. Motivation factors for suicidal behavior and their clinical relevance in admitted psychiatric patients. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0176565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176565

3. Barzilay S, Apter, A. Psychological models of suicide. Arch Suicide Res. (2014) 18:295–312. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.824825

4. Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. (2003) 301:386–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968

5. O'Connor RC. The integrated motivational volitional model of suicidal behavior. Crisis. (2011) 32:295–8. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000120

6. Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Allman C, Friend A, Roth C, et al. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1993) 32:521–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00006

7. Martunnen M, Pelkonen M. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a review. Psychiatr Fenn. (2000) 31:110–25.

8. Riskind JH, Long GD, Williams NL, White JC. Desperate acts for desperate times: looming vulnerability and suicide. In: Joiner TE, Rudd DM, editors. Suicide Science: Expanding the Boundaries. Boston MA: Springer Norwell (2002). p. 105–15.

9. Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, Newsom JT. Physical illness, functional limitations, and suicide risk: a population-based study. Am J Orthopsychiatry. (2007) 77:56. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.56

10. Giletta M, Scholte RH, Engels RC, Ciairano S, Prinstein MJ. Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: a cross-national study of community samples from Italy, the Netherlands and the United States. Psychiatry Res. (2012) 197:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.009

11. Hallfors D, Brodish PH, Khatapoush S, Sanchez V, Cho H, Steckler A. Feasibility of screening adolescents for suicide risk in “real-world” high school settings. Am J Public Health. (2006) 96:282–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057281

12. Luncheon C, Bae S, Gonzalez A, Lurie S, Singh KP. Hispanic female adolescents' use of illicit drugs and the risk of suicidal thoughts. Am J Health Behav. (2008) 32:52–9. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.32.1.5

13. Nickerson AB, Slater ED. School and community violence and victimization as predictors of adolescent suicidal behavior. School Psych Rev. (2009) 38:218–32. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2009.12087833

14. Waldrop AE, Hanson RF, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Naugle AE, Saunders BE. Risk factors for suicidal behavior among a national sample of adolescents: implications for prevention. J Trauma Stress. (2007) 20:869–79. doi: 10.1002/jts.20291

15. Barbagli M. Congedarsi dal Mondo: Il Suicidio in Occidente e in Oriente. Bologna: Il Mulino (2009).

17. Goldston DB, Daniel SS, Erkanli A, Reboussin BA, Mayfield A, Frazier PH, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses as contemporaneous risk factors for suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults: Developmental changes. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2009) 77:281–90. doi: 10.1037/a0014732

18. Hjelmeland H, Dieserud G, Dyregrov K, Knizek BL, Leenaars AA. Psychological autopsy studies as diagnostic tools: are they methodologically flawed? Death Stud. (2012) 36:605–26. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2011.584015

19. Sanati A. Does suicide always indicate a mental illness? London J Prim Care. (2009) 2:93–4. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2009.11493259

20. Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, Kegler SR, Yuan K, Holland KM, et al. Vital signs: trends in state suicide rates - United States, 1999-2016 and circumstances contributing to suicide - 27 states, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2018) 67:617–24. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a1

21. Holma KM, Haukka J, Suominen K, Valtonen HM, Mantere O, Melartin TK, et al. Differences in incidence of suicide attempts between bipolar I and II disorders and major depressive disorder. Bipolar Disord. (2014) 16:652–61. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12195

22. De Crescenzo F, Serra G, Maisto F, Uchida M, Woodworth H, Casini MP, et al. Suicide attempts in juvenile bipolar vs. major depressive disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2017) 56:825–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.783

23. Hor K, Taylor M. Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol. 24(Suppl. 4):81–90. doi: 10.1177/1359786810385490

24. Krausz M, Müller-Thomsen T, Haasen C. Suicide among schizophrenic adolescents in the long-term course of illness. Psychopathology. (1995) 28:95–103. doi: 10.1159/000284906

25. Russell B, Toomey AK, Shramko M. Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics. (2018) 142:e20174218. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4218

26. Ferrara M, Terrinoni A, Williams R. Non-suicidal self-injury (Nssi) in adolescent inpatients: assessing personality features and attitude toward death. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2012) 6:12. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-6-12

27. Krysinska K, Heller TS, De Leo D. Suicide and deliberate self-harm in personality disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2006) 19:95–101. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000191498.69281.5e

28. Giner L, Blasco-Fontecilla H, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Garcia-Nieto R, Giner J, Guija JA, et al. Personality disorders and health problems distinguish suicide attempters from completers in a direct comparison. J Affect Disord. (2013) 151:474–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.029

29. Ayodeji E, Green J, Roberts C, Trainor G, Rothwell J, Woodham A, et al. The influence of personality disorder on outcome in adolescent self-harm. Br J Psychiatry. (2015) 207:313–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.138941

30. Dixon WA, Heppner PP, Rudd MD. Problem-solving appraisal, hopelessness, and suicide ideation: evidence for a mediational model. J Couns Psychol. (1994) 41:91–8. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.41.1.91

31. Donaldson D, Spirito A, Farnett E. The role of perfectionism and depressive cognitions in understanding the hopelessness experienced by adolescent suicide attempters. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2000) 31:99–111. doi: 10.1023/A:1001978625339

32. Conner KR, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Seiditz L, Caine, ED. Psychological vulnerability to completed suicide: a review of empirical studies. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2001) 31:367–85. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.4.367.22048

33. Roy A. Family history of suicide and neuroticism: a preliminary study. Psychiatry Res. (2002) 110:87–90. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00011-2

34. Beevers CG, Miller IW. Perfectionism, cognitive bias, and hopelessness as prospective predictors of suicidal ideation. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2004) 34:126–37. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.2.126.32791

35. Hirvikoski T, Jokinen J. Personality traits in attempted and completed suicide. Eur Psychiatry. (2012) 27:536–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.04.004

36. Keller MC, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. (2007) 164:1521–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091564

37. Blasco-Fontecilla H, Baca-Garcia E, Duberstein P, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Dervic K, Saiz-Ruiz J, et al. An exploratory study of the relationship between diverse life events and specific personality disorders in a sample of suicide attempters. J Pers Disord. (2010) 24:773–84. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.6.773

38. Goodman M, Tomas IA, Temes CM, Fitzmaurice GM, Aguirre BA, Zanarini MC. Suicide attempts and self-injurious behaviours in adolescent and adult patients with borderline personality disorder. Pers Ment Health. (2017) 11:157–63. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1375

39. Greenfield B, Henry M, Lis E, Slatkoff J, Guilé JM, Dougherty G, et al. Correlates, stability and predictors of borderline personality disorder among previously suicidal youth. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2014) 24:397–406. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0589-9

40. Kuba T, Yakushi T, Fukuhara H, Nakamoto Y, Singeo Jr ST, Tanaka O, et al. Suicide-related events among child and adolescent patients during short-term antidepressant therapy. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2011) 65:239–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02204.x

41. Bjureberg J, Sahlin H, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Gratz KL, Tull MT, Jokinen J, et al. Extending research on emotion regulation individual therapy for adolescents (ERITA) with nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: open pilot trial and mediation analysis of a novel online version. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18:326. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1885-6

42. Muehlenkamp JJ, Ertelt TW, Miller AL, Claes L. Borderline personality symptoms differentiate non-suicidal and suicidal self-injury in ethnically diverse adolescent outpatients. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2011) 52:148–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02305.x

43. Glenn CR, Bagge CL, Osman A. Unique associations between borderline personality disorder features and suicide ideation and attempts in adolescents. J Pers Disord. (2013) 27:604–16. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2013_27_102

44. Yalch MM, Hopwood CJ, Fehon DC, Grilo CM. The influence of borderline personality features on inpatient adolescent suicide risk. Pers Disord. (2014) 5:26–31. doi: 10.1037/per0000027

45. Ronningstam EF. I Disturbi del Narcisismo. Diagnosi, Clinica, Ricerca. Milano: Cortina (2001). p. 93–4.

46. Ronningstam E, Weinberg I, Maltsberger JT. Eleven deaths of Mr. K.: Contributing factors to suicide in narcissistic personalities. Psychiatry. (2008) 71:169−82. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.2.169

47. Blasco-Fontecilla H, Baca-Garcia E, Dervic K, Perez-Rodriguez MM, LopezCastroman J, Saiz-Ruiz J, et al. Specific features of suicidal behavior in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2009) 70:1583. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04899

48. Ronningstam E, Weinberg I, Goldblatt M, Schechter M, Herbstman B. Suicide and self-regulation in narcissistic personality disorder. Psychodyn Psychiatry. (2018) 46:491–510. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2018.46.4.491

49. Cross D, Westen D, Bradley B. Personality subtypes of adolescents who attempt suicide. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2011) 199:750–6. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31822fcd38

50. O'Connor RC, Matthew KN. The psychology of suicidal behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry. (2014) 1.1:73–85. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70222-6

51. O'connor RC, O'carroll RE, Ryan C, Smyth R. Self-regulation of unattainable goals in suicide attempters: a twoyear prospective study. J Affect Disord. (2012) 142:248–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.035

52. O'Connor RC, Rasmussen S, Hawton K. Predicting depression, anxiety and self-harm in adolescents: the role of perfectionism and acute life stress. Behav Res Ther. (2010) 48:52–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.008

53. O'Connor RC, Rasmussen S, Hawton K. Distinguishing adolescents who think about self-harm from those who engage in self-harm. Br J Psychiatry. (2012) 200:330–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.097808

54. Large MM. The role of prediction in suicide prevention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2018) 20:197–205.

55. Thapar A, Pine D, Leckman JF, Scott S, Snowling MJ, Taylor EA. Rutter's Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons (2017).

56. Kelley AE, Schochet T, Landry CF. Risk taking and novelty seeking in adolescence: introduction to part I. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2004) 1021:27–32. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.003

57. Laufer ME, Laufer M. Adolescence and Developmental Breakdown: A Psychoanalytic View. Routledge: Yale University Press (1984).

59. Chein J, Albert D, O'Brien L, Uckert K, Steinberg L. Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain's reward circuitry. Dev. Sci. (2011) 14:F1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x

60. Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The adolescent brain. Ann NY Acad Sci. (2008) 1124:111–26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.010

61. Rudd MD. Fluid Vulnerability Theory: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding the Process of Acute and Chronic Suicide Risk. Cognition and Suicide: Theory, Research, and Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. (2006). p. 355–68.

62. Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. (2010) 15:868–76. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29

63. Bancroft J, Hawton K, Simkin S, Kingston B, Cumming C, Whitwell D. The reasons people give for taking overdoses: a further inquiry. Br J Med Psychol. (1979) 52:353–65. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979.tb02536.x

64. Hawton K, Cole D, O'Grady J, Osborn M. Motivational aspects of deliberate self-poisoning in adolescents. Br J Psychiatry. (1982) 141:286–91. doi: 10.1192/bjp.141.3.286

65. Kienhorst IWM, De Wilde EJ, Diekstra RF. Suicidal behaviour in adolescents. Arch Suicide Res. (1995) 1:185–209. doi: 10.1080/13811119508251957

66. Boergers J, Spirito A, Donaldson D. Reasons for adolescent suicide attempts: associations with psychological functioning. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1998) 37:1287–93. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00012

67. Chu J, Khoury O, Ma J, Bahn F, Bongar B, Goldblum P. An empirical model and ethnic differences in cultural meanings via motives for suicide. J Clin Psychol. (2017) 73:1343–59. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22425

68. Ligier F, Michaud L, Kabuth B, Lesage A, Corriveau P, Séguin M. A quantitative and qualitative study of notes left by youth who died by suicide in Quebec from 1895 to 1985. Arch Suicide Res. (2019) 0:1–14. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2019.1645068

69. Rost F, Luyten P, Fonagy P. The anaclitic–introjective depression assessment: development and preliminary validity of an observer-rated measure. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2017) 25:195–209. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2153

71. Johns D, Holden RR. Differentiating suicidal motivations and manifestations in a nonclinical population. Can J Behav Sci. (1997) 29:266. doi: 10.1037/0008-400X.29.4.266

72. Holden RR, McLeod LD. The structure of the Reasons for Attempting Suicide Questionnaire (RASQ) in a nonclinical adult population. Personal Ind Diff. (2000) 29:621–8. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00214-7

73. Holden R, DeLisle MM. Factor structure of the Reasons for Attempting Suicide Questionnaire (RASQ) with suicide attempters. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. (2006) 28:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10862-006-4532-3

74. May AM, Klonsky ED. Assessing motivations for suicide attempts: development and psychometric properties of the inventory of motivations for suicide attempts. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2013) 43:532–46. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12037

75. May AM, O'Brien KMH, Liu RT, Klonsky ED. Descriptive and psychometric properties of the inventory of motivations for suicide attempts (IMSA) in an inpatient adolescent sample. Arch Suicide Res. (2016) 20:476–82. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1095688

76. Shneidman ES. Commentary: suicide as psychache. J Nerv Ment Dis. (1993) 181:145–7. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199303000-00001

77. Williams JMG, Pollock LR. Psychological aspects of the suicidal process. In: van Heeringen k, editor. Understanding Suicidal Behaviour: The Suicidal Process Approach to Research, Treatment and Prevention. Chichester: Wiley (2001). p. 76–94.

78. Freudenstein O, Valevski A, Apter A, Zohar A, Shoval G, Nahshoni E, et al. Perfectionism, narcissism, and depression in suicidal and nonsuicidal adolescent inpatients. Compr Psychiatry. (2012) 53:746–52. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.08.011

79. Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT. Precipitating factors and life events in serious suicide attempts among youths aged 13 through 24 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1997) 36:1543–51. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66563-1

80. Yen S, Pagano ME, Shea MT, Grilo CM, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, et al. Recent life events preceding suicide attempts in a personality disorder sample: findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2005) 73:99–105. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.99

81. Fazaa N, Page S. Dependency and self-criticism as predictors of suicidal behavior. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2003) 33:172–85. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.2.172.22777

82. Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: a 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2000) 68:371. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.371

83. Moon SS, Karlson A, Kim YJ. Peer victimization and adolescent suicide: the mediating effect of risk behaviors. Child Adolesc Social Work J. (2015) 32:257–268. doi: 10.1007/s10560-014-0365-1

84. Javdani S, Sadeh N, Verona E. Suicidality as a function of impulsivity, callous–unemotional traits, and depressive symptoms in youth. J Abnorm Psychol. (2011) 120:400–13. doi: 10.1037/a0021805

85. Pietropolli Charmet G, Piotti A. Uccidersi. Il Tentativo di Suicidio in Adolescenza. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore (2009).

86. Cha CB, Franz PJ, M Guzmán E, Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Nock MK. Suicide among youth—epidemiology, (potential) etiology, and treatment. J. Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2018) 59:460–82. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12831

87. Adams DM, Overholser JC, Spirito A. Stressful life events associated with adolescent suicide attempts. Can J Psychiatry. (1994) 39:43–8. doi: 10.1177/070674379403900109

88. Bilsen J. Suicide and youth: risk factors. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:540. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540

89. Miller AB, Prinstein MJ. Adolescent suicide as a failure of acute stress-response systems. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. (2019) 15:425–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095625

90. Kaufman J, Rao U, Ryan N, Birmaher B. K-SADS-PL. Intervista Diagnostica per la Valutazione dei Disturbi Psicopatologici in Bambini e Adolescenti. Manuale e protocolli. Gardolo-Trento: Edizioni Erickson (2004).

91. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Benjamin LS, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-R Axis II Personality Disorders SCID-II. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub (1997).

92. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, et al. The Columbia–suicide severity rating scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. (2011) 168:1266–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704

Keywords: suicide, adolescence, motivation, assessment, risk factors

Citation: Moselli M, Frattini C, Williams R and Ronningstam E (2021) The Study of Motivation in the Suicidal Process: The Motivational Interview for Suicidality. Front. Psychiatry 11:598866. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.598866

Received: 25 August 2020; Accepted: 30 November 2020;

Published: 13 January 2021.

Edited by:

Kerstin Jessica von Plessen, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV), SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Laurent Michaud, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV), SwitzerlandGregor E. Berger, Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland

Copyright © 2021 Moselli, Frattini, Williams and Ronningstam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Riccardo Williams, cmljY2FyZG8ud2lsbGlhbXNAdW5pcm9tYTEuaXQ=

Marta Moselli

Marta Moselli Camilla Frattini1

Camilla Frattini1 Riccardo Williams

Riccardo Williams Elsa Ronningstam

Elsa Ronningstam