94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry , 28 January 2021

Sec. Mood Disorders

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589545

This article is part of the Research Topic Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) on Mood Disorders and Suicide View all 41 articles

Objective: Health-care workers (HCW) are at risk for psychological distress during an infectious disease outbreak, such as the coronavirus pandemic, due to the demands of dealing with a public health emergency. This rapid systematic review examined the factors associated with psychological distress among HCW during an outbreak.

Method: We systematically reviewed literature on the factors associated with psychological distress (demographic characteristics, occupational, social, psychological, and infection-related factors) in HCW during an outbreak (COVID-19, SARS, MERS, H1N1, H7N9, and Ebola). Four electronic databases were searched (2000 to 15 November 2020) for relevant peer-reviewed research according to a pre-registered protocol. A narrative synthesis was conducted to identify fixed, modifiable, and infection-related factors linked to distress and psychiatric morbidity.

Results: From the 4,621 records identified, 138 with data from 143,246 HCW in 139 studies were included. All but two studies were cross-sectional. The majority of the studies were conducted during COVID-19 (k = 107, N = 34,334) and SARS (k = 21, N = 18,096). Consistent evidence indicated that being female, a nurse, experiencing stigma, maladaptive coping, having contact or risk of contact with infected patients, and experiencing quarantine, were risk factors for psychological distress among HCW. Personal and organizational social support, perceiving control, positive work attitudes, sufficient information about the outbreak and proper protection, training, and resources, were associated with less psychological distress.

Conclusions: This review highlights the key factors to the identify HCW who are most at risk for psychological distress during an outbreak and modifying factors to reduce distress and improve resilience. Recommendations are that HCW at risk for increased distress receive early interventions and ongoing monitoring because there is evidence that HCW distress can persist for up to 3 years after an outbreak. Further research needs to track the associations of risk and resilience factors with distress over time and the extent to which certain factors are inter-related and contribute to sustained or transient distress.

Several outbreaks of viral diseases have posed significant public health threats since 2000. These include SARS, H1N1, H7N9, MERS, EBOLA, and more recently, COVID-19 (see Supplementary Table 1). Such outbreaks place a serious strain on the health-care systems that try to contain and manage them, including health-care workers (HCW) who are at increased risk for nosocomial infections (1). In addition to the threat to their own physical health, HCW can experience psychological distress as a collateral cost of the risk of infection and the demands of dealing with a public health emergency (2).

Psychological distress refers to a state of emotional suffering, resulting from being exposed to a stressful event that poses a threat to one's physical or mental health (3). Inability to cope effectively with the stressor results in psychological distress that can manifest as a range of adverse mental health and psychiatric outcomes including depression, anxiety, acute stress, post-traumatic stress, burnout, and psychiatric morbidity. Although psychological distress is often viewed as a transient state that negatively impacts day-to-day and social functioning, it can persist and have longer-term negative effects on mental health (4).

Under normal circumstances, work-related psychological distress in HCW is associated with several short and long-term adverse outcomes. Psychological distress is linked to adverse occupational outcomes including include decreased quality of patient care (5), irritability with colleagues (6), cognitive impairments that negatively impact patient care (7), and intentions to leave one's job (8). HCW who experience psychological distress are also at risk of experiencing adverse personal outcomes including substance misuse (6), and suicide (9). In the context of an infectious disease outbreak, such consequences may amplify and heighten psychological distress. HCW who reported elevated levels of psychological distress during the COVID-19 outbreak also experienced sleep disturbances (10), poorer physical health (11), and a greater number of physical symptoms, including headaches (12). Similarly, HCW during the SARS outbreak disclosed a greater number of somatic symptoms and sleep problems (13), substance misuse and more days off work (14).

Apart from the immediate and short-term impacts on HCW mental health, there is limited but concerning evidence, that working during an infectious outbreak can have lasting and detrimental psychological effects for HCW. In a study of HCW who worked during the SARS outbreak in China, 10 percent experienced high levels of post-traumatic stress (PTS) symptoms when surveyed 3 years later (15). Similarly, HCW who treated patients during the SARS outbreak in Canada reported significantly higher levels of burnout, psychological distress, and post-traumatic stress compared to HCW in other hospitals that did not treat SARS patients when surveyed 13–26 months after the SARS outbreak (14). Lastly, a study of HCW in Hong Kong during the SARS outbreak found that although the levels of perceived stress did not differ between HCW who worked in high risk and low risk areas initially, 1 year later the stress of the high-risk HCW was significantly increased, and was higher than the stress reported by the low-risk HCW (16). This increased level of stress was also associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress, indicating a pervasive and sustained negative impact of working during an outbreak on mental health. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the factors that contribute to risk and resilience for psychological distress in HCW.

HCW serve a vital role in treating and managing infected individuals during an infectious disease outbreak such as coronavirus. There is an urgent need to understand the factors that create or heighten risk for distress for HCW and affect their immediate and long-term mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic and other similar outbreaks, as well as those that are protective and may reduce psychological distress. Such knowledge is important for identifying HCW most at risk, and informing strategies and treatments needed to support HCW resilience during and after an outbreak.

This rapid review synthesized the evidence on the factors associated with psychological distress among health-care workers (HCW) during an infectious disease outbreak. The review focused not only on the COVID-19 pandemic, but also on other related coronavirus and influenza outbreaks (SARS, H1N1, H7N9, MERS, and Ebola), to expand the potential evidence base and to increase the potential for the findings to be generalizable across any future infectious disease outbreaks.

This review also introduced a conceptual framework for understanding and classifying the factors that contributed to risk or provided resilience for psychological distress. Based on our early scan of the literature, we grouped factors into three conceptual categories: (1) fixed or unchangeable factors, (2) potentially modifiable factors, and (3) factors related to infection exposure. Fixed factors were viewed as identifying HCW who might be most vulnerable or resilient to distress and, if the former, require extra support and treatment. Socio-demographic factors and other factors related to work role and experience were included in this category. In contrast, modifiable factors were viewed as identifying potential targets for interventions to reduce risk and increase resilience. Social and psychological factors, such as social support, stigma, and psychological resources such as coping styles and personality were included in the modifiable category. Lastly, infection-related factors were those that can directly inform hospital procedures and operating policy regarding ways to address and mitigate risk. Factors related to infection exposure and risk of exposure, and the provision of training, resources, and personal protective equipment (PPE) were included in this category.

The key questions addressed by this review were:

1) What are the risk factors for psychological distress among HCW during an infectious outbreak?

2) What are the factors associated with reduced risk for psychological distress among HCW during an infectious outbreak?

Evidence was summarized using a rapid, systematic review approach because of the urgent need to support the mental health of HCW during and after the ongoing novel coronavirus pandemic. Rapid Reviews are a form of systematic review that provide an expedient and useful means of synthesizing the available evidence during times of health crises to inform evidence-based decision making for health policy and practice (17, 18). To accomplish this, rapid reviews take a streamlined approach to systematically reviewing evidence. Modified methods in the current review included: (1) search limited to English language studies; (2) gray literature limited to one search source; (3) no formal critical appraisal of the research.

The search strategy for this pre-registered rapid review involved searching Medline, PsycInfo, Web of Science, and the first 10 pages of Google Scholar, as well as hand searching references. Search terms included a combination of terms related to health-care workers (e.g., “physicians,” “nurses”), and distress (e.g., “stress,” “anxiety”). The full search term list is available on PROSPERO (CRD42020178185). We conducted searches in a rolling manner, starting on April 6, 2020, then with updates on June 7, July 2, July 10, July 30, 2020, and November 15, 2020 to capture and integrate the most up-to-date evidence given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the associated rapid release of research.

We used a predefined search strategy (see full details on PROSPERO, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/; registration ID: CRD42020178185). Studies were included in this Review if they were empirical research; published or accepted for publication in peer-reviewed journals; written in English; included participants who were HCW who worked in a hospital environment during a major infectious outbreak (COVID19, SARS, MERS, H1N1, H7N9, Ebola); had a sample size of >80, and included data on factors associated with psychological distress during an outbreak. One investigator screened citations for potential full-text review, and a second investigator conducted the full-text review of each study for inclusion. Exclusions were verified by the other investigator, and disagreements resolved through discussion. Data was extracted by one investigator, entered into a table, and verified by a second investigator. For studies that included tests for multiple measures of psychological distress, we included the study as reporting a significant association with a particular factor if at least one of the measures of distress were significant.

Although rapid reviews do not always include a formal assessment of study quality and risk for bias (18), a lack of a quality assessment can have important implications for the utility of the results (17). Accordingly, we evaluated the methodological quality of the studies in the review using a tool adapted for the current study. The assessment tool included eleven questions chosen from the Appraisal tool for Cross Sectional Studies, AXIS (19) as being most relevant for the current study, an approach advocated by Quintana (20). Two authors independently rated the quality of the studies using the 11 questions to assess the quality of the study procedures, sampling, and the measures. The assessment yielded a total score that categorized studies as having low (<5), moderate (5–7), or high (8–10) quality. Inter-rater agreement was calculated and assessed using Cohen's Kappa coefficient (21). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. In addition to the formal quality assessment, we only included studies that reported findings for a sample size of >80, which allows enough power to detect a medium effect size with an alpha of 0.05 (21, 22).

We conceptually organized the factors in this Review identified as contributing to or mitigating psychological distress into three broad categories: (1) fixed or unchangeable factors (sociodemographic and occupational factors), (2) potentially modifiable factors (social and psychological factors), and (3) factors related to infection exposure. Evidence was synthesized according to these conceptual categories, with non-significant and contrary findings noted in addition to significant findings to provide a more complete picture of the weight of the evidence for each factor. The balance of evidence for each factor was further presented graphically. We assigned factors within each conceptual category as reflecting either risk or resilience for psychological distress according to logic and theory (e.g., maladaptive coping as risk, adaptive coping as resilience). Factors that could be interpreted as either risk or resilience (e.g., sex, age) were assigned according to how they had been framed in the majority of the research that examined these factors.

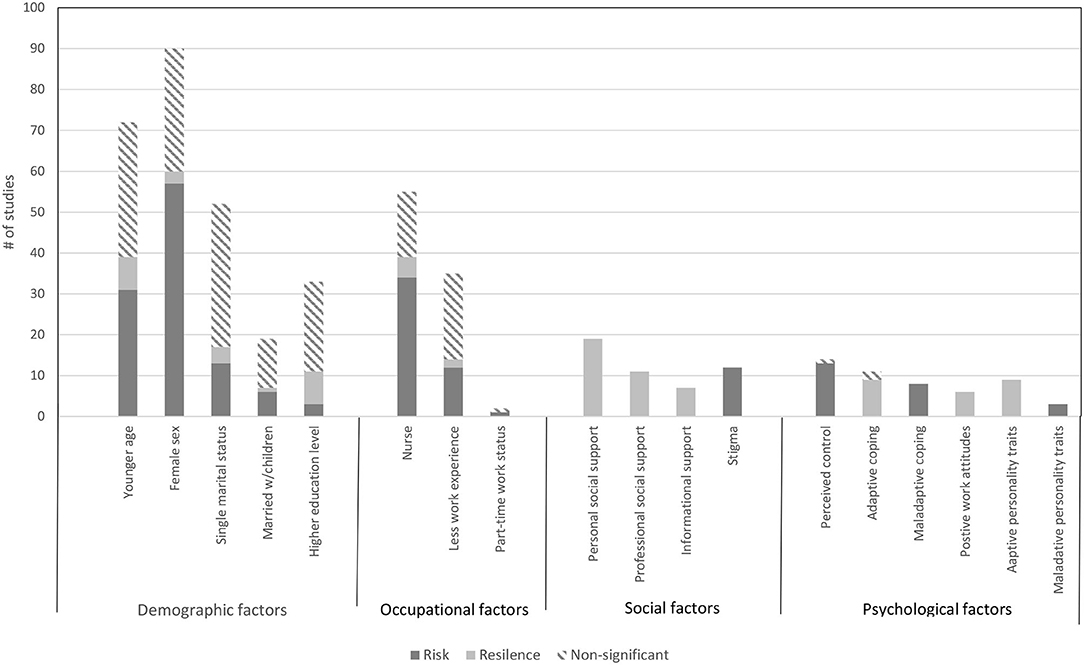

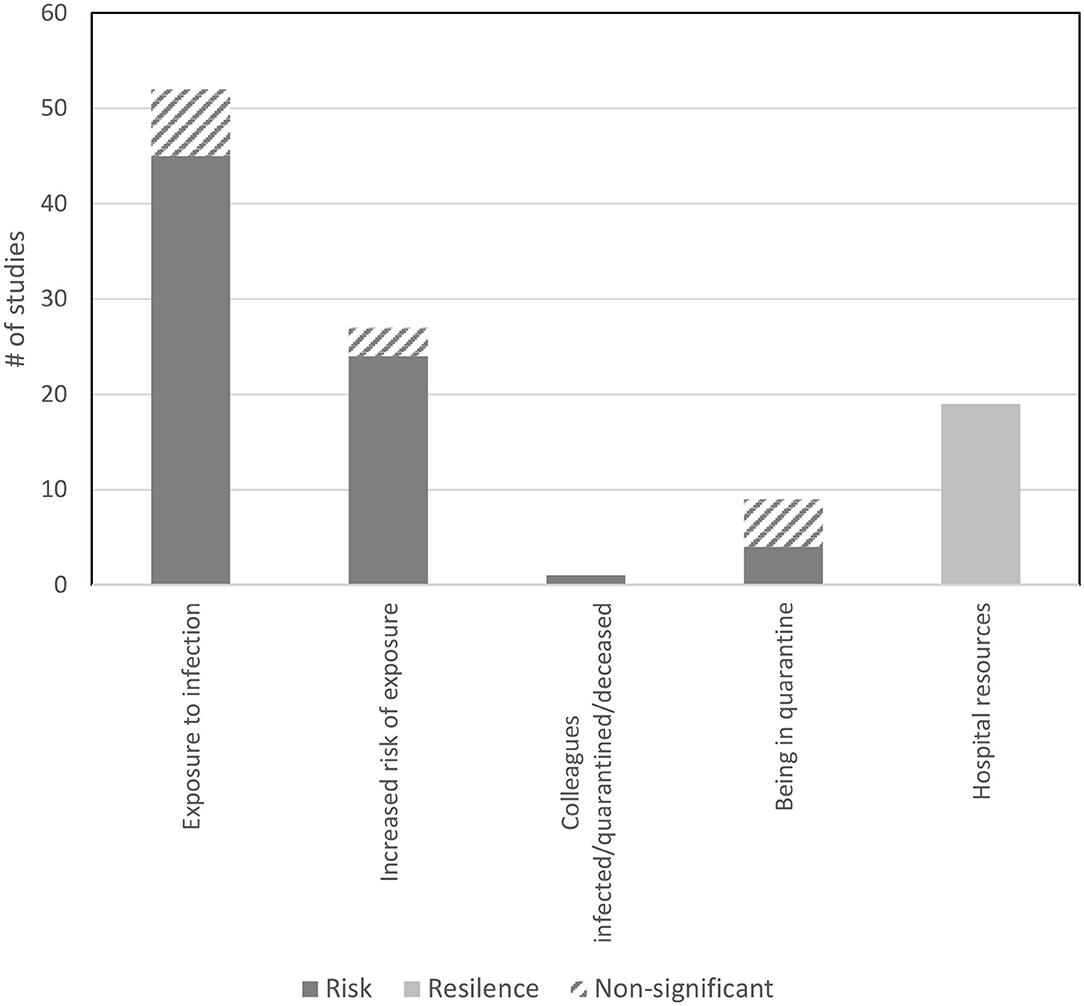

The search yielded 4621 records, with 138 papers reporting 139 studies (Total N = 143,246 HCW) that met inclusion criteria for this Review. Figure 1 presents the complete screening process. Characteristics of the studies are in Table 1. The average sample size was 1,030 (range 82–21,199). The studies included HCW working across 34 countries during COVID-19 (k = 107, N = 120,711), SARS (k = 21, N = 18,096), MERS (k = 7, N = 1,567), H1N1 (k = 2, N = 2,094), Ebola (k = 1, N = 143), and H7N9 (k = 1, N = 102), outbreaks. The rates of psychological distress in HCW varied depending on how distress was measured (Table 1). Figures 2, 3 provide a graphical overview of the weight of the evidence per factor.

Figure 2. Findings from the studies that examined fixed (demographic and occupational) and modifiable (social and psychological) factors and associations with risk and resilience for psychological distress.

Figure 3. Findings from the studies that examined factors related to infection exposure and associations with risk and resilience for psychological distress.

The quality of the studies ranged from moderate to high, with no studies rated as having low quality. The majority of the 139 studies were rated as having high quality (118; 84.9%), and 21 studies were rated as having a moderate quality (15.1%). Inter-rater agreement was high, 90.65% agreement, Cohen's Kappa = 0.642 (see Supplementary Table 2).

Seventy-two studies examined age as a predictor of psychological distress among HCW during an epidemic (see Table 2). Of these, 39 found that age was a significant risk factor for distress. In two studies of HCW during the SARS outbreak, staff who were younger than 33 experienced greater stress, but not greater psychiatric morbidity, compared to older staff (134), and staff under 35 were more likely to report severe depressive symptoms 3 years after the outbreak (92). In another study, medical staff who were between 20 and 30 years old and exposed to patients with H7N9 had elevated post-traumatic stress disorder scores compared to older staff (157). Similarly, general practitioners in working during the SARS outbreak who met psychiatric caseness for PTSD were more likely to be younger (144). In a study during the H1N1 outbreak, hospital staff who were in their 20's had greater anxiety about becoming infected than did older staff (103). During COVID-19, HCW who were younger were more likely to experience higher levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms, depression, anxiety, and acute stress compared to older HCW (23, 26–28, 30, 32, 42, 49, 54, 55, 57, 61, 65, 71, 75, 78, 89, 90, 117, 118, 121, 123, 127, 131, 149, 153, 154). In contrast, eight studies conducted during COVID found that HCW who were older were at greater risk of experiencing higher levels of psychological distress (40, 66, 86, 95, 102, 114, 122, 132). Lastly, 33 studies found that age was not a significant predictor of distress in HCW during the SARS, MERS or during the COVID-19 outbreaks (Table 2).

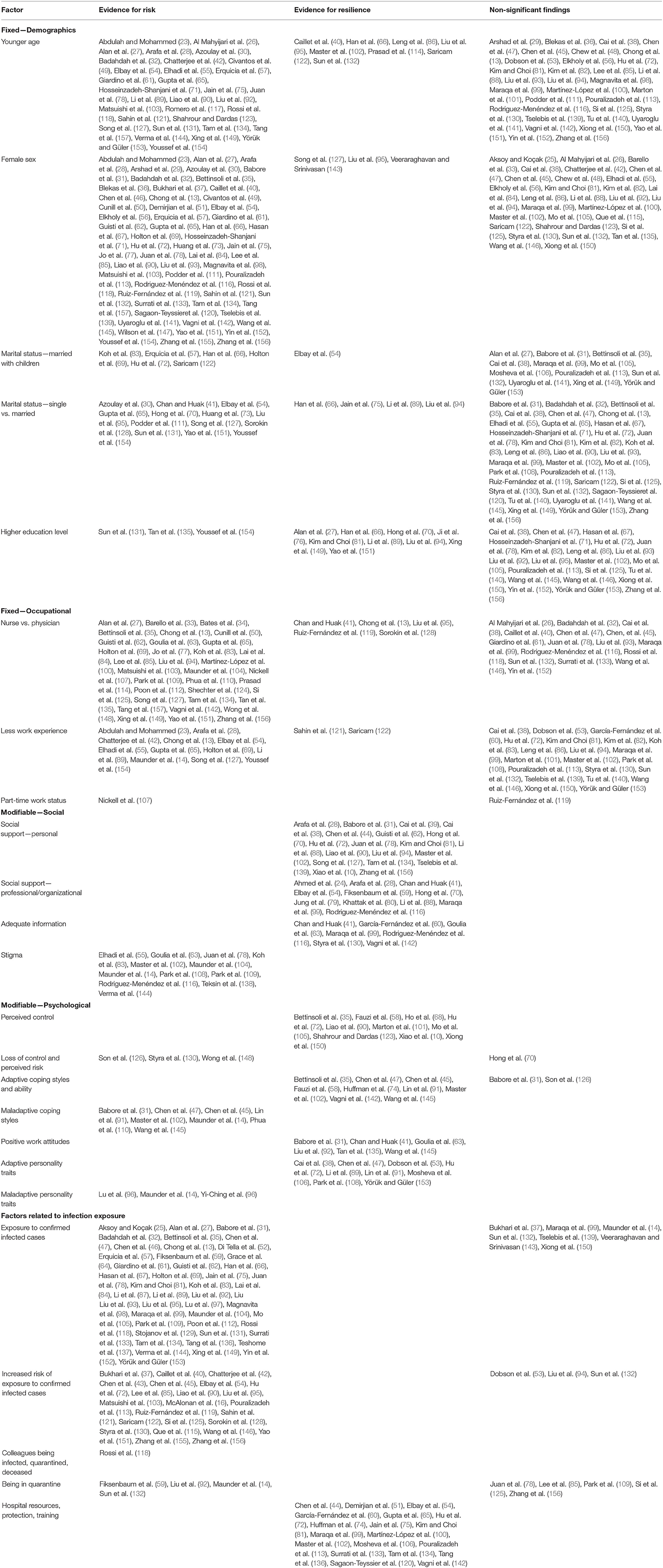

Table 2. Overview of the evidence for the factors associated with risk and resilience for psychological distress in health-care workers.

Ninety studies tested sex as a possible risk factor for distress among HCW during an outbreak (Table 2), with all but 33 finding that being female was associated with higher risk for psychological distress. Notably, the 57 studies that found that female sex was a significant risk factor spanned six different infectious diseases (MERS, SARS, COVID-19, H1N1, H7N9, and SARS), suggesting that being a female HCW increases vulnerability for distress more generally when working during an infectious outbreak. Notably, among the studies 30 studies that did not find that being female created significant risk for distress, eleven (36.6%) were conducted with nurses and included predominantly female participants (24, 43, 44, 59, 70, 79, 80, 89, 108, 140, 153).

Of the 69 studies that examined marital status as a risk or resilience factor for psychological distress, 19 found evidence to suggest this as a risk factor (Table 2). For example, two studies of HCW during the SARS outbreak found that HCW who were single were 1.4 times more likely to experience psychological distress than married HCW (41), and more likely to have sever depressive symptoms 3 years later (92). Similarly, HCW during the COVID-19 outbreak who were single experienced higher levels of distress than those who were married (54, 57, 66, 69, 111, 122, 126). Conversely, four studies conducted during COVID-19 found that being married was a risk factor for greater distress (66, 75, 89, 94), and two studies found that married HCW with children reported greater stress than single HCW or those who were married without children (72, 83). Forty-seven other studies conducted during the SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 outbreaks found no associations between HCW marital status and distress (Table 2).

Thirty-three studies examined education levels in association with distress. Only eight studies, six conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (27, 66, 70, 89, 94, 149, 151), along with studies conducted during the Ebola outbreak (76), and the MERS outbreak (81) found that HCW with higher educational levels reported significantly lower psychological distress. Twenty-two studies found that education level was not predictive of psychological distress among HCW working during the MERS or the COVID-19 outbreaks (Table 2).

Thirty-four studies examined and found evidence that the HCW occupational role created risk for psychological distress while working during the SARS, H1N1, MERS, and COVID-19 outbreaks (Table 2). In all but 16 studies, being a nurse was associated with a range of mental health issues, including higher stress, burnout, anxiety, depression, PTSD symptoms, psychiatric morbidity, and psychological distress compared to being a physician or other HCW (see Tables 1, 2). The extent to which nurses experienced greater psychological distress whilst working during an outbreak was estimated in several studies. For example, nurses were 1.2 (83), 1.4 (124), 2.2 (63), and 2.8 (107) times more likely to be at risk for poor mental health. In contrast, five studies found that physicians (13, 97, 119, 128) and technicians (41) were more likely to experience distress while working during the COVID-19 pandemic and the SARS outbreak. Sixteen studies conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak did not find that occupational role was a risk factor for distress (Table 2).

Other occupational factors examined included years of work experience, and full-time vs. part-time status. Twelve of the 35 studies found evidence to suggest that less work experience may create risk (Table 2). HCW who had worked for <2 years experienced significantly greater stress than those with more work experience in a large sample of HCW during the SARS pandemic (13). In HCW during the SARS outbreak, those with <10 years of experience reported higher levels of psychological distress, but not burnout or post-traumatic stress, 13–26 months after the outbreak (14). HCW who had less clinical experience were also more likely to experience stress during the COVID-19 outbreak (23, 28, 55, 65, 69, 154). Years of clinical experience was not associated with PTSD symptoms, acute stress or anxiety, depression, mental health status, or burnout in 21 other studies (Table 2). Two studies found that less work experience was protective against distress for HCW during COVID-19 (121, 122). Lastly, in one study, part-time worker status was a significant predictor of greater emotional distress in HCW during the SARS outbreak (107), whereas another study found no evidence of part-time work status creating risk for distress in HCW during COVID-19 (119).

A number of social and interpersonal factors mitigated or contributed to psychological distress. Receiving direct social support from friends, family, colleagues and supervisors was a key protective factor in all of the 19 studies that examined its association with psychological distress (Table 2). For example, in HCW during the COVID-19 outbreak, higher levels of social support were associated with significantly lower levels of stress, depression, anxiety, depression and PTSD (28, 31, 38, 62, 70, 78, 88, 90, 94, 102, 139, 156). These findings were consistent with that of a study of frontline medical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak who reported that a positive attitude from co-workers was important for reducing their distress (39). Analogously, emergency nurses working during MERS outbreak who reported poor support from family and friends experienced higher levels of burnout (81). Similarly, studies of HCW during the SARS outbreak found that higher levels of family support were associated with lower depression and anxiety whereas inadequate support from relatives, lack of gratitude from patients and relatives, and perceiving less of a team spirit at work was associated with higher levels of psychological distress (44, 134).

Organizational support was an important factor in buffering psychological distress of HCW during an outbreak in all 11 studies that examined this factor. In nurses working during the SARS outbreak in Canada, higher perceived organizational support in the form of receiving positive performance feedback from doctors and co-workers, was associated with lower perceptions of SARS-related threat and reduced feelings of emotional exhaustion (59). Similarly, nurses, physicians, and HCW working during the MERS, COVID-19, and SARS outbreaks who perceived support from their supervisors and colleagues, experienced better mental health in the form of lower PTSD symptoms, lower distress, and being less likely to develop psychiatric symptoms, respectively (24, 28, 41, 54, 59, 70, 79, 80, 88, 99, 116).

Seven studies examined receiving useful information from others (a common form of social support). In one study, HCW who received adequate communication and information about the H1N1 outbreak from their organization were less likely to experience psychiatric symptoms because it helped them cope better, and worry less about the pandemic (63). Similarly, HCW during the SARS outbreak who had confidence in the information they received from their organization (130), and who received clear communication about directives and how to take precautionary measures (41), experienced reduced psychological distress. HCW working during the COVID-19 outbreak who felt that they did not receive sufficient information, scored significantly higher on anxiety and acute stress than those who were satisfied with the information provided (60, 99, 116, 142).

Negative social perceptions created risk for poor mental health for HCW in all 12 studies that examined this factor. In nurses during the MERS outbreak, perceived social stigma was associated with higher stress and poorer mental health (108). Similarly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, HCW who felt stigmatized, perceived stigma concerning negative public attitudes and disclosing about one's work, experienced higher levels of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress (55, 78, 102, 108, 109, 116, 138). During the SARS outbreak, HCW who felt people avoided their family because of their job were twice as likely to have elevated levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms (83). Importantly, experiencing stigma and avoidance from others was significantly associated with higher levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms during the SARS outbreak (104), and 13–26 months later (14).

The psychological factors examined in the studies included adaptive and maladaptive coping responses, beliefs and attitudes, and personality traits. Fourteen studies examined how perceptions of control were associated with distress among HCW (Table 2). In eight studies, higher self-efficacy was associated with lower anxiety, depression, distress, and lower levels of fear about SARS and post-traumatic stress symptoms during the COVID-19 and SARS outbreaks, respectively (10, 35, 68, 72, 90, 105, 123, 150). Conversely, feeling a loss of control was associated with greater distress (148) during the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. Analogously, appraisals of personal risk were linked to higher levels of PTSD symptoms in HCW during the MERS (126) and SARS (130) outbreaks. Only one study conducted with nurses during COVID-19 did not find evidence that risk appraisals were linked to greater distress (70).

Positive attitudes toward one's work were protective against distress in all six studies that examined this factor. Higher work satisfaction was associated with less psychological distress among hospital staff during the H1N1 outbreak (63), lower PTSD among nurses (145), and lower rates of burnout among HCW during the COVID-19 outbreak. Similarly, HCW during the SARS outbreak who felt their work had become more important were less likely to develop psychiatric symptoms (41), and those who viewed their work altruistically were less likely to have severe symptoms of depression 3 years later (92). HCW who held a positive attitude toward their work reported less stress during the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak (31).

Seventeen studies examined whether coping styles were associated with HCW distress during an outbreak (Table 2). Emergency physicians and nurses working during the SARS outbreak who used denial, mental disengagement, or venting of emotions to cope were more likely to score higher on psychiatric morbidity (110). Similar results were found in frontline nurses during COVID-19, with use of negative coping associated with higher PTSD and psychological distress (102), and positive coping linked to lower PTSD (145). In HCW during the SARS outbreak, those who used maladaptive coping strategies, such as escape-avoidance, and self-blame coping, reported higher levels of burnout, psychological distress, and post-traumatic stress when surveyed 13–26 months after the outbreak (14). However, the use of adaptive strategies, such as problem-solving and positive reappraisal, were not associated with any of the distress outcomes. This finding was consistent with those from studies in which coping ability was not significantly associated with PTSD symptoms during the MERS outbreak (126), and problem-solving and turning to religion to cope were not associated with reduced distress during COVID-19 (31).

Twelve studies investigated the role of personality in HCW's psychological distress (Table 2). During the SARS outbreak, neuroticism was linked to poorer mental health (96), and HCW who had an anxious attachment style reported experiencing higher burnout, psychological distress, and post-traumatic stress 13–26 months after the outbreak (14). Those with an avoidant attachment style reported greater distress, but not burnout or post-traumatic stress. Eight studies examined the role of dispositional resilience. Among nurses working during the MERS outbreak, higher levels of hardiness were associated with lower stress and better mental health (108), and resilience was associated with lower anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and burnout among frontline nurses and HCW during COVID-19 (38, 45, 72, 74, 89, 91, 153).

Fifty-three studies examined the impact of direct contact with infected patients on HCW's psychological distress. Of these, the majority (65) found that being in direct contact with and/or treating patients infected with COVID-19, SARS, MERS, or H7N9 was a risk factor for psychological distress (Table 2). Only eight studies did not find that contact with infected patients increased risk for distress in HCW during the COVID-19, SARS, and MERS outbreaks. Similarly, 24 studies found that risk of contact with infected patients due to working in high-risk areas (e.g., ICU, isolation areas and infection units) was associated with higher levels of anxiety, stress, and post-traumatic stress symptoms than not working in such areas (Table 2). Notably, one study found that HCW in a high-risk unit during SARS reported higher and sustained perceived stress 1 year after the outbreak compared to those in low-risk units, with those in low-risk units reporting a decrease in stress over time, but those in high-risk units experiencing an increase in stress post-outbreak (16). Three studies conducted during COVID-19 found that risk of contact was not associated with greater distress (53, 94, 132). Spending time in quarantine due to risk of being infected was associated with higher levels of burnout, depression, and psychological distress in HCW during SARS and COVID-19 (14, 59, 92, 132), but was unrelated to post-traumatic stress symptoms and psychological distress in HCW during the MERS outbreak or the COVID-19 outbreak (78, 85, 109, 125, 156). Lastly, one study found that HCW who had colleagues who became infected, had deceased due to infection, or had been quarantined, also experienced higher levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms and acute stress during the COVID-19 outbreak (118).

Provision of adequate training, protection, and other resources to manage and reduce risk of infection was associated with less psychological distress in all 19 studies that examined this factor (Table 2). Receiving clear infection control guidelines predicted lower psychological morbidity in frontline HCW during SARS (134), and having sufficient hospital resources for the treatment of MERS was associated with lower MERS-related burnout (81). After the implementation of a SARS protection training program, HCW experienced significant decreases in anxiety and depression 2 weeks and 1 month after the starting the program (44). Similarly, medical staff receiving inadequate training related to managing H7N9 had higher PTSD symptoms than those who received appropriate training (81). During COVID-19, HCW who felt HCW who felt that they did not have adequate information, training, personal protective equipment (PPE), felt unsafe, and perceived lower logistic support, reported higher levels of depression, anxiety, and acute stress symptoms (51, 54, 60, 65, 72, 74, 99, 100, 102, 106, 120, 142).

To our knowledge, this rapid systematic review of 139 samples of 143,246 HCW working during an infectious outbreak is the largest and most up to date review of the evidence on the factors that contribute to risk or resilience to psychological distress. In this review we introduced a conceptual framework that categorized the factors contributing to increased and reduced risk of psychological distress among HCW during an infectious disease outbreak into three main categories, including factors that were fixed, modifiable, and related to infection exposure. The majority of the studies reviewed examined the role of fixed factors (demographic and occupational), with fewer studies examining how modifiable factors (social and psychological) were associated with psychological distress in HCW working during an outbreak.

For the fixed factors, the weight of the evidence indicated that HCW who were female or a nurse were at significant risk for psychological distress (Figure 2). Nurses tend to tend to be predominantly female, have higher workloads (104), and have more patient contact than other HCW. Indeed, we found that over 36 percent of the studies that found no significant relationship between being female and increased psychological distress involved only nurses.

There was also clear and consistent evidence that HCW who had or were at risk for contact with infected patients, were more likely to experience psychological distress (Figure 3). Worry about becoming infected is a key stressor for HCW in the context of an outbreak as risk of infection has implications not only for their own health but also for that of their families (83). Evidence also indicated that being in quarantine contributes to distress, perhaps due to being isolated from the team (158), and that vicariously experiencing these risks can be detrimental for HCW mental health (118).

Although relatively fewer studies investigated modifiable factors (Figure 2), the evidence highlighted key target areas to reduce HCW distress. It is also worth noting that the findings from the studies examining the role of social and psychological factors were extremely consistent. This lends confidence to the suggestion that these factors are important targets for intervention to reduce distress and bolster resilience. Stigmatizing attitudes from the public toward HCW were consistently associated with greater distress across the studies reviewed. Although stigma can be effectively reduced through social contact with those who experience stigmatization (159), this approach may not be practical or advisable during an outbreak. Instead, public health campaigns that deliver accurate messages and highlight facts to reduce the fears underlying stigma (160), counteracting the climate of fear cultivated through the media which can promote stigma during an infectious outbreak (161) could assist.

The evidence was unanimous in indicating that perceiving social support was associated with lower distress. Adequate social support is a resilience factor that is well-known to be effective reducing stress across a number of stressful situations (162), and is equally important for reducing stress among HCW (163). This support can come from supervisors and co-workers (164), either formally or informally, through positive performance feedback (59), and positive attitudes, and through peer support groups. Organizational social support may be especially important to fill the gap when personal social support may be sparse because regular social support sources are struggling with their own distress during an outbreak. Such support can also foster positive work attitudes and satisfaction (165), which were associated with lower distress.

The evidence reviewed was also consistent in indicating that harmful coping strategies linked to greater distress, and positive coping strategies were protective for distress. Interventions that target harmful coping strategies, such as avoidance and self-blame, that can that may maintain or increase stress, may be worthwhile. Identifying when HCW may be using such strategies and finding ways to foster more positive approaches for managing stress are important for not only for reducing distress, but also for reducing the risk of other adverse health consequences. For example, HCW who experienced post-traumatic stress during the SARS outbreak and used harmful coping were at greater risk for substance abuse (166). Mental health check-ups are one approach that could help monitor both HCW distress and whether appropriate coping strategies are being used (167).

In keeping with evidence that low perceived control is a transdiagnostic vulnerability factor for anxiety (168), perceptions of control were consistently associated with lower distress in the evidence reviewed. Indeed, having a sense of control is a well-known factor for reducing health-related distress (162). Feeling a loss of control may be inevitable during an infectious outbreak, as perceptions of risk are inversely related to perceived control (169). However, interventions focused on increasing a sense of autonomy can be effective for reducing distress in HCW during times of upheaval (170). The evidence reviewed suggests that this might be accomplished at the organizational level by providing HCW with the resources needed to manage the risk of infection. For example, providing personal protective equipment (PPE), adequate training, and clear guidelines, information, and protocols for infection control are important, because having such resources is linked to lower distress. This conclusion is consistent with research that found that access to information and provision of needed resources increased a sense of empowerment among ICU nurses (171).

Adaptive personality traits consistently linked to better mental health outcomes in HCW working during an outbreak. Dispositional resilience was examined in the majority of the studies reviewed, with hardiness examined in one study. Dispositional resilience can be conceptualized in several different ways, including as a personal quality reflecting the capacity to cope, or as type of hardiness (172). When conceptualized as the former, resilience involves being flexible to change, managing unpleasant emotions, and not getting discouraged (173). Although personality traits are often viewed as being relatively stable, personality can also be viewed as reflecting personal qualities and tendencies that are expressed to a greater or lesser degree, and are therefore amenable to change (174). From this perspective, approaches that help HCW develop a tendency to use resilient coping skills may help reduce vulnerability to psychological distress during an outbreak.

There are several limitations of this rapid systematic review. Conducting the review during the ongoing outbreak of COVID-19 imposed time constraints. This meant that we only included published peer-reviewed literature and did not search more thoroughly through gray literature or online pre-print repositories. Most study samples were quite large, increasing confidence in the generalisability of the findings.

In terms of the evidence base, the majority of the studies were cross-sectional, providing only a snapshot of the factors associated with HCW psychological distress. This limits conclusions about the direction of causality between the factors and distress, especially for those factors that are modifiable. Only three studies examined the potential long-term effects of the risk and resilience factors on HCW's mental health by using follow-up and time-lagged designs (14, 16, 92), providing some support for the assumed contribution of the factors to distress. More research needs to track the associations of risk/resilience factors over time with distress and the extent to which certain factors link to sustained or transient distress.

The majority of the studies were conducted during COVID-19, with relatively fewer studies reporting results from other infectious outbreaks such as SARS, MERS, H1N1, H7N9, and Ebola. On the one hand, this could be viewed as a limitation on the generalisability of the findings from the predominant outbreak, COVID-19, to other infectious outbreaks. On the other hand, we would argue that the consistency of the findings for a number of factors including participant sex, being a nurse, all 10 of the social and psychological factors, four of the five infection exposure factors, demonstrate that findings are likely to be generalizable across infectious outbreaks for these factors.

Although a number of studies investigated fixed factors and infection-related factors, relatively fewer studies examined how modifiable factors linked to distress (Figures 2, 3). There is a need for more research focusing on these factors to provide a more solid evidence base about potential targets for clinical intervention and treatment. A handful of studies used unvalidated measures of psychological distress, raising concerns about whether the findings would be the same had validated measures been used. For those studies that used validated measures, the ways in which cut-off scores for caseness were calculated, and/or the ways in classification of symptoms met thresholds for psychological distress, undoubtedly varied between measurement instruments. This likely introduced some variance into the results.

Few studies considered potential confounders in the associations with distress, compared found associations in matched non-HCW samples, or the extent to which the factors were predictive of distress outside of an outbreak. As well, the results extracted from the studies reflect a mix of bivariate and multivariate associations, as not all studies reported the bivariate only findings, which would be more comparable for making comparisons. Studies that examined the factors in multivariate analyses often used different covariates making it difficult to draw equitable conclusions from the studies. It is therefore difficult to assess the degree to which certain factors may independently predict psychological distress over and above other factors. Collectively, these limitations may have contributed to the equivocal findings noted for several of the factors reviewed.

Several strengths of the Review balance these limitations. Conceptually organizing the factors according to risk or resilience and whether they were fixed or modifiable, provided a theoretical framework for identifying who might be at most risk for psychological distress. This facilitates appropriate clinical intervention, and for noting which factors would be suitable targets for potential interventions. We also reported non-significant and contrary findings alongside significant findings to provide a more balanced and critical overview of the evidence. The Review included evidence from across six infectious disease outbreaks, with the majority of the research reporting findings from coronavirus outbreaks—Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (COVID-19), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS), and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS)—that share similarities in their symptom and contagion profiles. Consistent evidence for risk and resilience factors was found across these various infectious diseases, suggesting that the findings from this review may be applicable across different outbreaks. This is relevant for understanding the mental health of HCW in future outbreaks. Lastly, conducting a series of search updates ensured integration of the most recent evidence from the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak into the review at the time of submission.

Whereas, other reviews have documented the extent of distress experienced by HCW during an outbreak (2), the current Review highlights the profiles of HCW most at risk for psychological distress and psychiatric morbidity during an outbreak. This identified modifiable factors that warrant further investigation as possible points of intervention to mitigate distress. Viewing risk and resilience factors from the lens of fixed and modifiable factors provides an efficient and useful approach for understanding who is most at risk and how to address that risk during and after an outbreak. Further research focusing on possible interactions among these factors would be useful to gain a better understanding of both the risk profiles and key modifiable factors, as the evidence reviewed did not consistently examine this area.

There is evidence that the psychological distress from working during an outbreak can persist for 2–3 years after the outbreak (14–16). Therefore, monitoring and providing appropriate support should continue beyond the outbreak period to ensure mental health recovery, especially among HCW who are most at risk. Our findings suggest that particular attention should be paid to female HCW and nurses (regardless of sex), and those who come into contact with infected patients or their environments to ensure that they receive necessary resources and provision of support to manage psychological distress. Proactive approaches at the organizational level can be effective (164) and may be necessary to help reduce the psychological distress of HCW. For example, a study of HCW during the COVID-19 outbreak in China found that mental health resources and services were mainly used by those experiencing mild and subthreshold levels of psychological distress rather than those who experienced more severe distress (11). Addressing the mental health needs of HCW with more severe distress will likely require more proactive means from health-care organizations.

There are a number of delivery methods to provide support and help HCW modify risk factors and foster resilience factors. These include telehealth, mobile apps, online toolkits, and peer-support, either in person or virtual (175). Combining different approaches may also be effective. For example, social support and perceived control can have an additive effect for reducing stress related to job demands (176). There is also evidence for the effectiveness of interventions for reducing HCW distress when delivered at the person level and organizational level (164), as well as those that target lifestyle practices (177, 178).

Evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that third-wave cognitive behavioral therapeutic approaches, such as mindfulness (178), gratitude (177), and self-compassion (179), are effective for reducing stress and burnout among healthcare professionals, and could be beneficial. In low-resource settings, peer-support is one option that has been shown to be effective for reducing occupational distress in HCW (164). Raising awareness of the impact of an infectious outbreak on HCW mental health, providing appropriate treatment and therapy, and fostering proactive approaches such as an organizational culture of support (180), are recommended as possible approaches that can help prepare HCW for future outbreaks and address any persistent, long-term distress following the outbreak.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

FS and JO designed and conceived the study, searched for evidence, screened and analyzed the data, drafted the work, revised it critically for intellectual content, approved the final piece of work for publication, and agree to be accountable for the work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

An earlier version of this manuscript has been released as a pre-print at medRxiv (181).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589545/full#supplementary-material

1. Chou R, Dana T, Buckley DI, Selph S, Fu R, Totten AM. Epidemiology of and risk factors for coronavirus infection in health care workers. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 173:120–36. doi: 10.7326/L20-1323

2. Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:901–7. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3594632

3. Drapeau A, Marchand A, Beaulieu-Prévost D. Epidemiology of psychological distress. In: LAbate L, editor. Mental Illnesses: Understanding, Prediction and Control. London: IntechOpen (2012). doi: 10.5772/30872

4. Horwitz AV. Distinguishing distress from disorder as psychological outcomes of stressful social arrangements. Health. (2007) 11:273–89. doi: 10.1177/1363459307077541

5. Stansfeld S, Head J, Rasul F. Occupation and mental health: secondary analyses of the ONS psychiatric morbidity survey of Great Britain. In: Queen Mary School of Medicine & Dentistry and the Office of National Statistics for the Health and Safety Executive. London (2009). doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0173-7

6. Taylor C, Graham J, Potts H, Candy J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Impact of hospital consultants' poor mental health on patient care. Br J Psychiatry. (2007) 190:268–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023234

7. Isaac CL, Cushway D, Jones GV. Is post-traumatic stress disorder associated with specific deficits in episodic memory? Clin Psychol Rev. (2006) 26:939–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.004

8. Dall'Ora C, Griffiths P, Ball J, Simon M, Aiken LH. Association of 12 h shifts and nurses' job satisfaction, burnout and intention to leave: findings from a cross-sectional study of 12 European countries. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e008331. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008331

9. Adler NR, Adler KA, Grant-Kels JM. Doctors' mental health, burnout, and suicidality: professional and ethical issues in the workplace. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2017) 77:1191–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.07.011

10. Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monitor. (2020) 26:e923549. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923921

11. Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028

12. Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, Jing M, Goh Y, Ngiam NJH, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:559–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049

13. Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC, Lee CY, Chiu NM, Yeh WC, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry. (2004) 185:127–33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.2.127

14. Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, Bennett JP, Borgundvaag B, Evans S, et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. (2006) 12:1924–32. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060584

15. Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. (2009) 54:302–11. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400504

16. McAlonan GM, Lee AM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Tsang KW, Sham PC, et al. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can J Psychiatry. (2007) 52:241–7. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200406

17. Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci. (2010) 5:56. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-56

18. Haby MM, Chapman E, Clark R, Barreto J, Reveiz L, Lavis JN. What are the best methodologies for rapid reviews of the research evidence for evidence-informed decision making in health policy and practice: a rapid review. Health Res Policy Syst. (2016) 14:83. doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0155-7

19. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e011458. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

20. Quintana DS. From pre-registration to publication: a non-technical primer for conducting a meta-analysis to synthesize correlational data. Front Psychol. (2015) 6:1549. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01549

22. Baird HM, Webb TL, Martin J, Sirois FM. The relationship between time perspective and self-regulatory processes, abilities and outcomes: a protocol for a meta-analytical review. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e017000. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017000

23. Abdulah DM, Mohammed AA. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on perceived stress in clinical practice: experience of doctors in Iraqi Kurdistan. Rom J Intern Med. (2020). doi: 10.2478/rjim-2020-0020

24. Ahmed F, Zhao F, Faraz NA. How and when does inclusive leadership curb psychological distress during a crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1898. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01898

25. Aksoy YE, Koçak V. Psychological effects of nurses and midwives due to COVID-19 outbreak: the case of Turkey. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2020) 34:427–33. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.07.011

26. Al Mahyijari N, Badahdah A, Khamis F. The psychological impacts of COVID-19: a study of frontline physicians and nurses in the Arab world. Irish J Psychol Med. (2020) 1–6. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.119

27. Alan H, Bacaksiz FE, Tiryaki Sen H, Taskiran Eskici G, Gumus E, Harmanci Seren AK. “I'm a hero, but…”: an evaluation of depression, anxiety, and stress levels of frontline healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2020). doi: 10.1111/ppc.12666. [Epub ahead of print].

28. Arafa A, Mohammed Z, Mahmoud O, Elshazley M, Ewis A. Depressed, anxious, and stressed: what have healthcare workers on the frontlines in Egypt and Saudi Arabia experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Affect Disord. (2021) 278:365–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.080

29. Arshad AR, Islam F. COVID-19 and anxiety amongst doctors: a Pakistani perspective. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. (2020) 30:106–9. doi: 10.29271/jcpsp.2020.Supp2.106

30. Azoulay E, De Waele J, Ferrer R, Staudinger T, Borkowska M, Povoa P, et al. Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann Intensive Care. (2020) 10:110. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00722-3

31. Babore A, Lombardi L, Viceconti ML, Pignataro S, Marino V, Crudele M, et al. Psychological effects of the COVID-2019 pandemic: perceived stress and coping strategies among healthcare professionals. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 293:113366. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113366

32. Badahdah A, Khamis F, Al Mahyijari N, Al Balushi M, Al Hatmi H, Al Salmi I, et al. The mental health of health care workers in Oman during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2020) 20764020939596. doi: 10.1177/0020764020939596. [Epub ahead of print].

33. Barello S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 290:113129. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113129

34. Bates A, Ottaway J, Moyses H, Perrrow M, Rushbrook S, Cusack R. Psychological impact of caring for critically ill patients during the Covid-19 pandemic and recommendations for staff support. J Intensive Care Soc. (2020) 1751143720965109. doi: 10.1177/1751143720965109

35. Bettinsoli ML, Di Riso D, Napier JL, Moretti L, Bettinsoli P, Delmedico M, et al. Mental health conditions of italian healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 disease outbreak. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. (2020) 12:1054–73. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/w89fz

36. Blekas A, Voitsidis P, Athanasiadou M, Parlapani E, Chatzigeorgiou AF, Skoupra M, et al. COVID-19: PTSD symptoms in Greek health care professionals. Psychol Trauma. (2020) 12:812–9. doi: 10.1037/tra0000914

37. Bukhari EE, Temsah MH, Aleyadhy AA, Alrabiaa AA, Alhboob AA, Jamal AA, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak perceptions of risk and stress evaluation in nurses. J Infect Dev Ctries. (2016) 10:845–50. doi: 10.3855/jidc.6925

38. Cai W, Lian B, Song X, Hou T, Deng G, Li H. A cross-sectional study on mental health among health care workers during the outbreak of corona virus disease 2019. Asian J Psychiatry. (2020) 51:102111. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102111

39. Cai H, Tu B, Ma J, Chen L, Fu L, Jiang Y, et al. Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in hunan between January and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Med Sci Monit. (2020). 26:e924171. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924171

40. Caillet A, Coste C, Sanchez R, Allaouchiche B. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on ICU caregivers. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 39:717–22. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2020.08.006

41. Chan AO, Huak CY. Psychological impact of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on health care workers in a medium size regional general hospital in Singapore. Occup Med. (2004) 54:190–6. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqh027

42. Chatterjee S, Bhattacharyya R, Bhattacharyya S, Gupta S, Das S, Banerjee B. Attitude, practice, behavior, and mental health impact of COVID-19 on doctors. Indian J Psychiatry. (2020) 62:257–65. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_333_20

43. Chen CS, Wu HY, Yang P, Yen CF. Psychological distress of nurses in Taiwan who worked during the outbreak of SARS. Psychiatr Serv. (2005) 56:76–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.1.76

44. Chen R, Chou K-R, Huang Y-J, Wang T-S, Liu S-Y, Ho L-Y. Effects of a SARS prevention programme in Taiwan on nursing staff's anxiety, depression and sleep quality: a longitudinal survey. Int J Nurs Stud. (2006) 43:215–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.03.006

45. Chen J, Liu X, Wang D, Jin Y, He M, Ma Y, et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in healthcare workers deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2020) 10:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01954-1

46. Chen R, Sun C, Chen J-J, Jen H-J, Kang XL, Kao C-C, et al. A large-scale survey on trauma, burnout, and post-traumatic growth among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2020). doi: 10.1111/inm.12796. [Epub ahead of print].

47. Chen H, Wang B, Cheng Y, Muhammad B, Li S, Miao Z, et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms in health care workers after exposure to patients with COVID-19. Neurobiol Stress. (2020) 13:100261. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100261

48. Chew NWS, Ngiam JN, Tan BY-Q, Tham S-M, Tan CY-S, Jing M, et al. Asian-Pacific perspective on the psychological well-being of healthcare workers during the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych open. (2020) 6:e116. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.98

49. Civantos AM, Bertelli A, Gonçalves A, Getzen E, Chang C, Long Q, et al. Mental health among head and neck surgeons in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national study. Am J Otolaryngol. (2020) 41:102694. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102694

50. Cunill M, Aymerich M, Serdà B-C, Patiño-Masó J. The impact of COVID-19 on Spanish health professionals: a description of physical and psychological effects. Int J Mental Health Promot. (2020) 22:185−98. doi: 10.32604/IJMHP.2020.011615

51. Demirjian NL, Fields BKK, Song C, Reddy S, Desai B, Cen SY, et al. Impacts of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on healthcare workers: a nationwide survey of United States radiologists. Clin Imaging. (2020) 68:218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.08.027

52. Di Tella M, Romeo A, Benfante A, Castelli L. Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. J Eval Clin Pract. (2020) 26, 1583–7. doi: 10.1111/jep.13444

53. Dobson H, Malpas CB, Burrell AJ, Gurvich C, Chen L, Kulkarni J, et al. Burnout and psychological distress amongst Australian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Australas Psychiatry. (2020) 1039856220965045. doi: 10.1177/1039856220965045. [Epub ahead of print].

54. Elbay RY, Kurtulmuş A, Arpacioglu S, Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 290:113130. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113130

55. Elhadi M, Msherghi A, Elgzairi M, Alhashimi A, Bouhuwaish A, Biala M, et al. Psychological status of healthcare workers during the civil war and COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosomatic Res. (2020) 137:110221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110221

56. Elkholy H, Tawfik F, Ibrahim I, Salah El-din W, Sabry M, Mohammed S, et al. Mental health of frontline healthcare workers exposed to COVID-19 in Egypt: a call for action. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 20764020960192. doi: 10.1177/0020764020960192

57. Erquicia J, Valls L, Barja A, Gil S, Miquel J, Leal-Blanquet J, et al. Emotional impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in one of the most important infection outbreaks in Europe. Med Clín. (2020) 155:434–40. doi: 10.1016/j.medcle.2020.07.010

58. Fauzi M, Yusoff MH, Robat RM, Saruan NAM, Ismail KI, Haris AFM. Doctors' mental health in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic: the roles of work demands and recovery experiences. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:7340. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197340

59. Fiksenbaum L, Marjanovic Z, Greenglass ER, Coffey S. Emotional exhaustion and state anger in nurses who worked during the SARS outbreak: The role of perceived threat and organizational support. Can J Commun Mental Health. (2006) 25:89–103. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2006-0015

60. García-Fernández L, Romero-Ferreiro V, López-Roldán PD, Padilla S, Calero-Sierra I, Monzó-García M, et al. Mental health impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish healthcare workers. Psychol Med. (2020). 1–3. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720002019

61. Giardino DL, Huck-Iriart C, Riddick M, Garay A. The endless quarantine: the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on healthcare workers after three months of mandatory social isolation in Argentina. Sleep Med. (2020) 76:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.09.022

62. Giusti EM, Pedroli E, D'Aniello GE, Stramba Badiale C, Pietrabissa G, Manna C, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684

63. Goulia P, Mantas C, Dimitroula D, Mantis D, Hyphantis T. General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. (2010) 10:322. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-322

64. Grace SL, Hershenfield K, Robertson E, Stewart DE. The occupational and psychosocial impact of SARS on academic physicians in three affected hospitals. Psychosomatics. (2005) 46:385–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.385

65. Gupta S, Prasad AS, Dixit PK, Padmakumari P, Gupta S, Abhisheka K. Survey of prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among 1124 healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic across India. Med J Armed Forces India. (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.07.006. [Epub ahead of print].

66. Han L, Wong FKY, She DLM, Li SY, Yang YF, Jiang MY, et al. Anxiety and depression of nurses in a North West province in china during the period of novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak. J Nurs Scholarship. (2020) 52:564–73. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12590

67. Hasan SR, Hamid Z, Jawaid MT, Ali RK. Anxiety among doctors during COVID-19 pandemic in secondary and tertiary care hospitals. Pak J Med Sci. (2020) 36:1360–5. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.6.3113

68. Ho SM, Kwong-Lo RS, Mak CW, Wong JS. Fear of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) among health care workers. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2005) 73:344–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.344

69. Holton S, Wynter K, Trueman M, Bruce S, Sweeney S, Crowe S, et al. Psychological well-being of Australian hospital clinical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Austr Health Rev. (2020). doi: 10.1071/AH20203. [Epub ahead of print].

70. Hong S, Ai M, Xu X, Wang W, Chen J, Zhang Q, et al. Immediate psychological impact on nurses working at 42 government-designated hospitals during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Outlook. (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2020.07.007

71. Hosseinzadeh-Shanjani Z, Hajimiri K, Rostami B, Ramazani S, Dadashi M. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels among healthcare staff during the COVID-19 epidemic. Basic Clin Neurosci. (2020) 11:163–70. doi: 10.32598/bcn.11.covid19.651.4

72. Hu D, Kong Y, Li W, Han Q, Zhang X, Zhu LX, et al. Frontline nurses' burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: a large-scale cross-sectional study. EClinicalMed. (2020) 24:100424. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100424

73. Huang L, Wang Y, Liu J, Ye P, Chen X, Xu H, et al. Short report: factors determining perceived stress among medical staff in radiology departments during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol Health Med. (2020) 26:56–61. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1837390

74. Huffman EM, Athanasiadis DI, Anton NE, Haskett LA, Doster DL, Stefanidis D, et al. How resilient is your team? Exploring healthcare providers' well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Surg. (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.09.005. [Epub ahead of print].

75. Jain A, Singariya G, Kamal M, Kumar M, Jain A, Solanki RK. COVID-19 pandemic: psychological impact on anaesthesiologists. Indian J Anaesthes. (2020) 64:774–83. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_697_20

76. Ji D, Ji YJ, Duan XZ, Li WG, Sun ZQ, Song XA, et al. Prevalence of psychological symptoms among Ebola survivors and healthcare workers during the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. Oncotarget. (2017) 8:12784–91. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14498

77. Jo S-H, Koo B-H, Seo W-S, Yun S-H, Kim H-G. The psychological impact of the coronavirus disease pandemic on hospital workers in Daegu, South Korea. Compr Psychiatry. (2020) 103:152213. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152213

78. Juan Y, Yuanyuan C, Qiuxiang Y, Cong L, Xiaofeng L, Yundong Z, et al. Psychological distress surveillance and related impact analysis of hospital staff during the COVID-19 epidemic in Chongqing, China. Compr Psychiatry. (2020) 103:152198. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152198

79. Jung H, Jung SY, Lee MH, Kim MS. Assessing the presence of post-traumatic stress and turnover intention among nurses post-middle east respiratory syndrome outbreak: the importance of supervisor support. Workplace Health Saf . (2020) 68:337–45. doi: 10.1177/2165079919897693

80. Khattak SR, Saeed I, Rehman SU, Fayaz M. Impact of fear of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of nurses in Pakistan. J Loss Trauma. (2020). doi: 10.1080/15325024.2020.1814580. [Epub ahead of print].

81. Kim JS, Choi JS. Factors influencing emergency nurses' burnout during an outbreak of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Korea. Asian Nurs Res. (2016) 10:295–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2016.10.002

82. Kim Y, Seo E, Seo Y, Dee V, Hong E. Effects of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus on post-traumatic stress disorder and burnout among registered nurses in South Korea. Int J Healthcare. (2018) 4. doi: 10.5430/ijh.v4n2p27. [Epub ahead of print].

83. Koh D, Lim MK, Chia SE, Ko SM, Qian F, Ng V, et al. Risk perception and impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on work and personal lives of healthcare workers in Singapore: what can we learn? Med Care. (2005) 43:676–82. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167181.36730.cc

84. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

85. Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho A-R, Kim T, Park JK. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. (2018) 87:123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003

86. Leng M, Wei L, Shi X, Cao G, Wei Y, Xu H, et al. Mental distress and influencing factors in nurses caring for patients with COVID-19. Nurs Crit Care. (2020). doi: 10.1111/nicc.12528. [Epub ahead of print].

87. Li Q, Chen J, Xu G, Zhao J, Yu X, Wang S, et al. The psychological health status of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional survey study in Guangdong, China. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:572. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.562885

88. Li X, Li S, Xiang M, Fang Y, Qian K, Xu J, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of PTSD symptoms among medical assistance workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychosomatic Res. (2020) 139:110270. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110270

89. Li X, Zhou Y, Xu X. Factors associated with the psychological well-being among front-line nurses exposed to COVID-2019 in China: a predictive study. J Nurs Manag. (2020). doi: 10.1111/jonm.13146. [Epub ahead of print].

90. Liao C, Guo L, Zhang C, Zhang M, Jiang W, Zhong Y, et al. Emergency stress management among nurses: a lesson from the COVID-19 outbreak in China–a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15553. [Epub ahead of print].

91. Lin J, Ren Y-H, Gan H-J, Chen Y, Huang Y-F, You X-M. Factors associated with resilience among non-local medical workers sent to Wuhan, China during the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:417. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02821-8

92. Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, Fan B, Fang Y, Kong J, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry. (2012) 53:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003

93. Liu C-Y, Yang Y-Z, Zhang X-M, Xu X, Dou Q-L, Zhang W-W, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. (2020) 148:e98. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001107

94. Liu Y, Chen H, Zhang N, Wang X, Fan Q, Zhang Y, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms of medical staff under COVID-19 epidemic in China. J Affect Disord. (2021) 278:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.004

95. Liu Y, Wang L, Chen L, Zhang X, Bao L, Shi Y. Mental health status of paediatric medical workers in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:702. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00702

96. Lu YC, Shu BC, Chang YY, Lung FW. The mental health of hospital workers dealing with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Psychother Psychosom. (2006) 75:370–5. doi: 10.1159/000095443

97. Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936

98. Magnavita N, Tripepi G, Di Prinzio RR. Symptoms in health care workers during the COVID-19 epidemic. A cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:5218. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145218

99. Maraqa B, Nazzal Z, Zink T. Palestinian health care workers' stress and stressors during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Primary Care Commun Health. (2020) 11:2150132720955026. doi: 10.1177/2150132720955026

100. Martínez-López J, Lázaro-Pérez C, Gómez-Galán J, Fernández-Martínez MDM. Psychological impact of COVID-19 emergency on health professionals: burnout incidence at the most critical period in Spain. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:3029. doi: 10.3390/jcm9093029

101. Marton G, Vergani L, Mazzocco K, Garassino MC, Pravettoni G. Heroes are not fearless: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on wellbeing and emotions of Italian health care workers during Italy phase 1. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:2781. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.588762

102. Master AN, Su X, Zhang S, Guan W, Li J. Psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak on frontline nurses: a cross-sectional survey study. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:4217–26. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15454

103. Matsuishi K, Kawazoe A, Imai H, Ito A, Mouri K, Kitamura N, et al. Psychological impact of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 on general hospital workers in Kobe. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2012) 66:353–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02336.x

104. Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Rourke S, Hunter JJ, Goldbloom D, Balderson K, et al. Factors associated with the psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on nurses and other hospital workers in Toronto. Psychosomatic Med. (2004) 66:938–42. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145673.84698.18

105. Mo Y, Deng L, Zhang L, Lang Q, Pang H, Liao C, et al. Anxiety of nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic and its correlation with work stress and self-efficacy. J Clin Nurs. (2020). doi: 10.1111/jocn.15549. [Epub ahead of print].

106. Mosheva M, Hertz-Palmor N, Dorman Ilan S, Matalon N, Pessach IM, Afek A, et al. Anxiety, pandemic-related stress and resilience among physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Depress Anxiety. (2020) 37:965–71. doi: 10.1002/da.23085

107. Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, Al-Enazy H, Bolaji Y, Hanjrah S, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ. (2004) 170:793–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031077

108. Park J-S, Lee E-H, Park N-R, Choi YH. Mental health of nurses working at a government-designated hospital during a MERS-CoV outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2018) 32:2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.09.006

109. Park C, Hwang JM, Jo S, Bae SJ, Sakong J. COVID-19 outbreak and its association with healthcare workers' emotional stress: a cross-sectional study. J Korean Med Sci. (2020) 35:e372. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e372

110. Phua DH, Tang HK, Tham KY. Coping responses of emergency physicians and nurses to the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Acad Emerg Med. (2005) 12:322–8. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.015

111. Podder I, Agarwal K, Datta S. Comparative analysis of perceived stress in dermatologists and other physicians during national lock-down and COVID-19 pandemic with exploration of possible risk factors: a web-based cross-sectional study from Eastern India. Dermatol Ther. (2020) 33:e13788. doi: 10.1111/dth.13788

112. Poon E, Liu KS, Cheong DL, Lee CK, Yam LY, Tang WN. Impact of severe respiratory syndrome on anxiety levels of front-line health care workers. Hong Kong Med J. (2004) 10:325–30.

113. Pouralizadeh M, Bostani Z, Maroufizadeh S, Ghanbari A, Khoshbakht M, Alavi SA, et al. Anxiety and depression and the related factors in nurses of Guilan University of medical sciences hospitals during COVID-19: a web-based cross-sectional study. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. (2020) 13:100233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100233

114. Prasad A, Civantos AM, Byrnes Y, Chorath K, Poonia S, Chang C, et al. Snapshot Impact of COVID-19 on mental wellness in nonphysician otolaryngology health care workers: a national study. OTO Open. (2020) 4:2473974X20948835. doi: 10.1177/2473974X20948835

115. Que J, Shi L, Deng J, Liu J, Zhang L, Wu S, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen Psychiatr. (2020) 33:e100259. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100259

116. Rodriguez-Menéndez G, Rubio-García A, Conde-Alvarez P, Armesto-Luque L, Garrido-Torres N, Capitan L, et al. Short-term emotional impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Spaniard health workers. J Affect Disord. (2021) 278:390–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.079

117. Romero C-S, Catalá J, Delgado C, Ferrer C, Errando C, Iftimi A, et al. COVID-19 Psychological Impact in 3109 Healthcare workers in Spain: The PSIMCOV Group. Psychological Medicine. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001671

118. Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, Di Lorenzo G, Di Marco A, Siracusano A, et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease (2019). (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2010185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185

119. Ruiz-Fernández MD, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Ibáñez-Masero O, Cabrera-Troya J, Carmona-Rega MI, Ortega-Galán ÁM. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 health crisis in Spain. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:4321–30. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15469

120. Sagaon-Teyssier L, Kamissoko A, Yattassaye A, Diallo F, Rojas Castro D, Delabre R, et al. Assessment of mental health outcomes and associated factors among workers in community-based HIV care centers in the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in Mali. Health Policy OPEN. (2020) 1:100017. doi: 10.1016/j.hpopen.2020.100017

121. Sahin MK, Aker S, Sahin G, Karabekiroglu A. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, distress and insomnia and related factors in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. J Commun Health. (2020) 45:1168–77. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00921-w

122. Saricam M. COVID-19-Related anxiety in nurses working on front lines in Turkey. Nurs Midwifery Stud. (2020) 9:178–81. doi: 10.4103/nms.nms_40_20

123. Shahrour G, Dardas LA. Acute stress disorder, coping self-efficacy and subsequent psychological distress among nurses amid COVID-19. J Nurs Manage. (2020) 28:1686–95. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13124

124. Shechter A, Diaz F, Moise N, Anstey DE, Ye S, Agarwal S, et al. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2020) 66:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.007

125. Si M-Y, Su X-Y, Jiang Y, Wang W-J, Gu X-F, Ma L, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect Dis Poverty. (2020) 9:113. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00724-0

126. Son H, Lee WJ, Kim HS, Lee KS, You M. Hospital workers' psychological resilience after the 2015 middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak. Soc Behav Personal. (2019) 47:7228. doi: 10.2224/sbp.7228

127. Song X, Fu W, Liu X, Luo Z, Wang R, Zhou N, et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002

128. Sorokin M, Kasyanov E, Rukavishnikov G, Makarevich O, Neznanov N, Morozov P, et al. Stress and stigmatization in health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Psychiatry. (2020) 62:445–53. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_870_20

129. Stojanov J, Malobabic M, Stanojevic G, Stevic M, Milosevic V, Stojanov A. Quality of sleep and health-related quality of life among health care professionals treating patients with coronavirus disease-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2020) 16:20764020942800. doi: 10.1177/0020764020942800