95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 10 November 2020

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.564172

This article is part of the Research Topic Outbreak Investigation: Mental Health in the Time of Coronavirus (COVID-19) View all 53 articles

Justin Thomas1*

Justin Thomas1* Mariapaola Barbato2

Mariapaola Barbato2 Marina Verlinden1

Marina Verlinden1 Carl Gaspar1

Carl Gaspar1 Mona Moussa2

Mona Moussa2 Jihane Ghorayeb2

Jihane Ghorayeb2 Aaina Menon1

Aaina Menon1 Maria J. Figueiras1

Maria J. Figueiras1 Teresa Arora1

Teresa Arora1 Richard P. Bentall3

Richard P. Bentall3The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health is likely to be significant. Identifying vulnerable groups during the pandemic is essential for targeting psychological support, and in preparation for any second wave or future pandemic. Vulnerable groups are likely to vary across different societies; therefore, research needs to be conducted at a national and international level. This online survey explored generalized anxiety and depression symptoms in a community sample of adults (N = 1,039) in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) between April 8th and April 22nd, 2020. Respondents completed symptom measures of depression (PHQ8) and generalized anxiety (GAD7), along with psychosocial and demographic variables that might potentially influence such symptoms. Bivariate and multivariate associations were calculated for the main study variables. Levels of anxiety and depression were notably higher than those reported in previous (pre-pandemic) national studies. Similar variables were statistically significantly associated with both depression and anxiety, most notably younger age, being female, having a history of mental health problems, self or loved ones testing positive for COVID-19, and having high levels of COVID-related anxiety and economic threat. Sections of the UAE population experienced relatively high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms during the early stages of the pandemic. Several COVID-related and psychosocial variables were associated with heightened symptomatology. Identifying such vulnerable groups can help inform the public mental health response to the current and future pandemics.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first detected in Wuhan China in the latter part of 2019. The disease caused by this novel virus was officially named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO) on Feb 22nd, 2020 (1). After the virus spread internationally, the WHO officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11th, 2020 and many nations began acting to curb the spread. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), a federation of seven states on the east coast of the Arabian Peninsula, launched various infection prevention and control measures, which have included the promotion of social distancing, quarantine, the closing of educational and recreational facilities, the cessation of passenger air travel and curfews. Table 1, based on UAE governmental and media sources, provides a timeline of some of the primary infection prevention and control measures taken by the UAE Government.

The UAE reported its first case on Jan 29th, 2020 (a family of four who had traveled to the UAE from Wuhan, China) and despite the extensive infection control efforts, the UAE confirmed its first two deaths on March 20th, 2020. New infections and deaths have ensued daily, and at the time of writing (May 18th, 2020) the UAE has tested more than 1 million people, reporting 23,358 cases (0.2% of the population) with 8,512 recoveries and 210 deaths. There is little doubt that the pandemic, and the necessary response to it, is causing considerable concern about its impact on mental health (2). From the grief associated with COVID-19 fatalities to the anxiety of testing positive, the pandemic has clear implications for mental health. Beyond the actual illness and the fear of contracting the virus, necessary restrictions placed on the freedom-of-movement, such as social/physical distancing, social isolation, quarantine and curfews, can also have negative implications for psychological well-being (2). Furthermore, anxiety surrounding the indirect effects of the economic implications associated with anti-pandemic measures, such as economic insecurity, may become an issue for some individuals and families.

Early research exploring the mental health consequences of COVID-19 in other nations support this view. A general population survey undertaken in the UK found that symptom measures of depression (PHQ9) and anxiety (GAD7) were elevated above those typically obtained in population surveys undertaken before the COVID-19 pandemic (3). A Chinese study, undertaken in Yunnan province, explored the rates of depression and anxiety among individuals affected or unaffected by quarantine measures, finding that those quarantined reported significantly higher rates of both (4). Other studies have looked at a variety of psychosocial factors correlated with mental health during the pandemic. For example, a study undertaken in Beirut, Lebanon, reported perceived social support as a potential resilience factor, that is, it was associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety symptomatology (5). Another study, this time in the USA, looked at religious coping among a Jewish community in New York, finding positive religious coping to be associated with less depressive symptomatology during the early stages of the pandemic (6). In another study, undertaken across, all 34 provinces of China, testing positive or having a relative who tested positive for COVID-19 was strongly associated with elevated depression and anxiety (7), All of these studies invariably reported levels of anxiety and depressive symptomatology elevated above pre-pandemic norms.

A rise in the symptoms of depression and anxiety is to be expected during times of international crisis. However, there is apprehension that this elevated symptomatology could translate into an increase in the number of clinically significant cases (2). There is evidence from earlier pandemics that this may be the case. A study undertaken in Hong Kong, for example, found that the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic of 2003 was associated with a 30% increase in completed suicides among females aged 65 years and over (8). One year after the outbreak, survivors of SARS still reported elevated levels of anxiety and psychological distress (9). Another study following SARS survivors over 30 months described SARS as “a mental health catastrophe,” finding PTSD and depression to be the most prevalent long-term psychiatric morbidities (10). The work on SARS focused primarily on patients and healthcare workers. There is very little research exploring the broader mental health implications at the population level.

The possible rise in rates of depression and anxiety associated with the COVID-19 pandemic intersects with a point in time when several nations are already reporting a rising prevalence of depression and anxiety (11). Population-wide surveys of mental health in the UAE are relatively rare. However, based on data from the 2010 Global Burden of Disease study, the UAE has a rate of depression higher than the global average (12). Community surveys in the UAE (13–15) and neighboring Gulf states all confirm relatively high rates of depression and anxiety in the immediate region (16). How the current COVID-19 pandemic will impact mental health in the UAE and other nations remains an unanswered question. However, there is likely to be significant international variation, based on differing responses to the pandemic, variations in healthcare systems, as well as diverse demography and sociocultural norms. For example, citizens of the UAE frequently live in multi-generational extended family households (17). For many directly transmitted infectious diseases, household size plays a crucial role in transmission due to the greater strength of contacts between individuals sharing living arrangements (18). Household size may also impact levels of anxiety about possible infection. Similarly, relative to the global average, the UAE has a youthful population with estimates suggesting that one-half to one-third of the population are under the age of 25 years (19). Population age has been found to have a potential impact on epidemic patterns for infectious diseases, for example, in the absence of vaccination, population aging is shown to reduce per capita incidence of infection (20).

Here we report the initial findings from the first wave of a longitudinal, multi-wave survey of the psychological impacts of COVID-19 among a large community sample of residents and citizens of UAE, adapting survey methods used in a UK mental health survey (3). Administered during the early stages of the pandemic (April 8th to April 22nd, 2020), the study's primary aim is to identify psychologically vulnerable groups, by assessing the relationship between psychological well-being and variables likely to influence the symptoms of depression and anxiety. This includes variables related to living arrangements, COVID-19 infection status, and mental health history. The main variables explored in the study are detailed in Table 2.

In light of the rising COVID-19 mortality and morbidity at the time of our study, and given the extensive, and necessary, restrictions imposed on freedom-of-movement, we anticipate higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to similar regional studies undertaken before the COVID-19 pandemic. More importantly, however, we also predict that COVID-related variables (e.g., infection status of self or loved ones) will be strongly associated with current levels of depression and anxiety. This study potentially contributes to what we know about the psychological consequences of pandemics in the UAE. The lack of knowledge about the impact of pandemics on population-level mental ill-health in the UAE, and elsewhere, is a critical gap to address. There is evidence from modeling studies that the psychological reactions (emotional and behavioral) to a pandemic can influence its course (21). Furthermore, the economic burden associated with elevated rates of mental ill-health are likely to negatively impact post-pandemic national recovery (3).

Participants (N = 1,039) were recruited via announcements in the UAE media and through the email networks of UAE's National Program for Happiness and Well-being. Participants were required to be residents of the UAE and aged 18 years or over. The sample was not representative of the whole UAE, but it did reflect many constituents. The sample comprised of people from 65 different nationalities, with citizens of the UAE (Emiratis) being the majority (73%). Reflecting the UAE's youthful population (19), the mean age was 28.33 (SD = 11.38) years. Females made up 85.6% of the sample, and the two most populous emirates/city-states represented, Abu Dhabi and Dubai, accounted for 59.2 and 31.7% of the sample, respectively.

All demographic and COVID-related measures were translated and back translated by two bilingual (Arabic/English) psychologists. Additional measures such as the GAD7 and PHQ8 were already available in Arabic and English. Participants were presented with English and Arabic links affording them a choice as to which language they completed the survey in.

Demographic survey items were adapted, with permission, from those used in a similar UK study by Shevlin et al. (3). Example items included: “What is your highest qualification?” and “How many adults (18 years or above) live in your household (including yourself)?” Personal history items included questions about pre-existing health conditions and mental health history. For the current analysis all demographic and personal responses were assigned to binary categories. For example, college educated (yes/no), religious affiliation (yes/no), lives alone (yes/no) were all dichotomized. Age was assigned to four groupings as detailed in Table 3. The dichotomization and categorization of continuous variables is commonly used in health related research to stratify patients according to risk, and guide the allocation of resources based on easily communicated models of greatest need/highest risk (22).

The COVID-related items were also adapted from Shevlin et al. (3) These specifically probed infection status: “Have you been infected by the coronavirus COVID-19?” and “Has someone close to you (a family member or friend) been infected by the coronavirus COVID-19?” Response options were “yes,” “no,” and “unsure.” These two items were collapsed into a single binary item called COVID-19 Positive, where anyone who had tested positive or had a family member test positive was assigned a one/yes. Meanwhile, those who have tested negative or were unsure about COVID-19 status were assigned a zero/no. Additional items asked people to rate their level of worry about COVID-19 (“How anxious are you about the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic? 0 = not at all anxious and 100 = extremely anxious”) and to indicate, from 1 to 10, their level of concern about finances: “On balance, how much are you worried about the way that your household finances have been affected by the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic SO FAR?” These last two scales were represented by slider controls, where sliding the control past the 50% mark indicated an orientation toward the unpleasant side of the scale. These normally distributed items were also dichotomized for the current analysis, with respondents scoring over 50 categorized as high in COVID-related anxiety while those scoring 50 or below were categorized as low to moderate. The same dichotomization was applied to financial worry, with scores above five categorized as high in COVID-19 related economic threat, while those scoring 5 or less were classed as experiencing low to moderate economic threat/insecurity.

Participants were also asked to provide an estimation of their perceived personal risk of contracting COVID-19 in the coming month, this was a single item as used in an earlier UK-based study[4]. Response options were low, moderate and high. The low and moderate were collapsed into a single category, creating two categories of self-perceived risk, high and not high (low to moderate).

The PHQ8 (23) is a widely used, standardized assessment of the prevalence and severity of depressive symptoms in the general population. It consists of eight questions probing the frequency of depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Responses can range from 0 to 3 (0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, 3 = nearly every day). Total scores, obtained by summing the responses to each item, range from 0 to 24. Total scores below 5 are viewed as indicating an absence of significant depressive symptoms. A cut-off score of ≥10 was used in the present study to indicate the presence of clinically significant depressive symptoms (moderate depression), this cut-off has previously been associated with excellent sensitivity and specificity for the detection of depressive disorders (23). The PHQ8 also uses scores of 15 and 20 and above to indicate severer levels of depression. The psychometric properties of the PHQ-8 scores have been widely supported, and the reliability of the scale among the current sample was excellent (α = 0.915).

The GAD7 (24) is a widely used measure of anxiety in the general population. Participants are asked to indicate how often, in the past 2 weeks, they have experienced each of seven main symptoms associated with generalized anxiety disorder. Total scores can range from 0 to 21 and are calculated by assigning scores of 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days), and 3 (nearly every day), to item response. Scores of 5, 10, and 15 are considered cut-off points for mild, moderate and severe anxiety, respectively. The psychometric properties of the instrument have been widely supported (25), and the reliability of the scale among the current sample was excellent (α = 0.921).

The study received ethical clearance from the university's research ethics committee (R201213) and from the Ministry of Health and Prevention's research ethics committee (MOHAP/DXB-REC/ MMM/No. 49/2020). Data collection took place online (www.symplexsoftware.com/covid19/), where participants first selected their preferred language (63.2% selected English) and then read the participant information page, prior to consent giving. Consenting participants answered demographic and personal history questions first, followed by the PHQ8, the GAD7 and then the section specific to COVID-19 concerns. The median completion time for the survey was 18 min and 3 s.

With the exception of age, all continuous variables were normally distributed. Age was left skewed due to a large number of relatively young people in the sample. Scores above the PHQ8 cut-off were notably high (58.4%). Similarly, scores above the GAD7 cut-off were also notably high (55.7%). The mean, standard deviation and bivariate correlation coefficient for all continuous variables are detailed in Table 4.

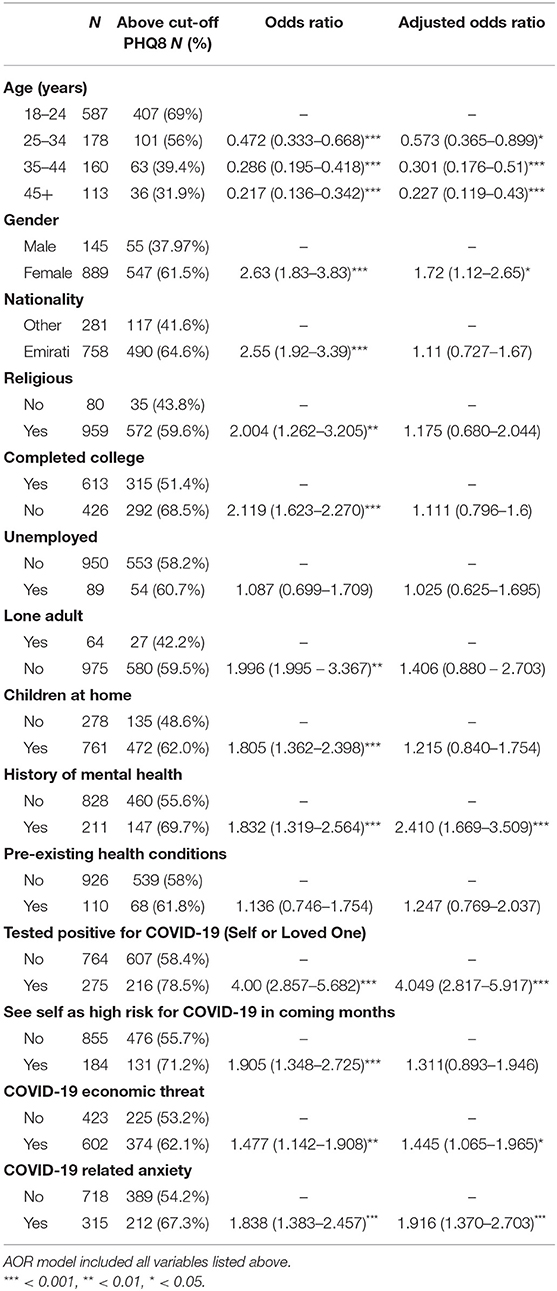

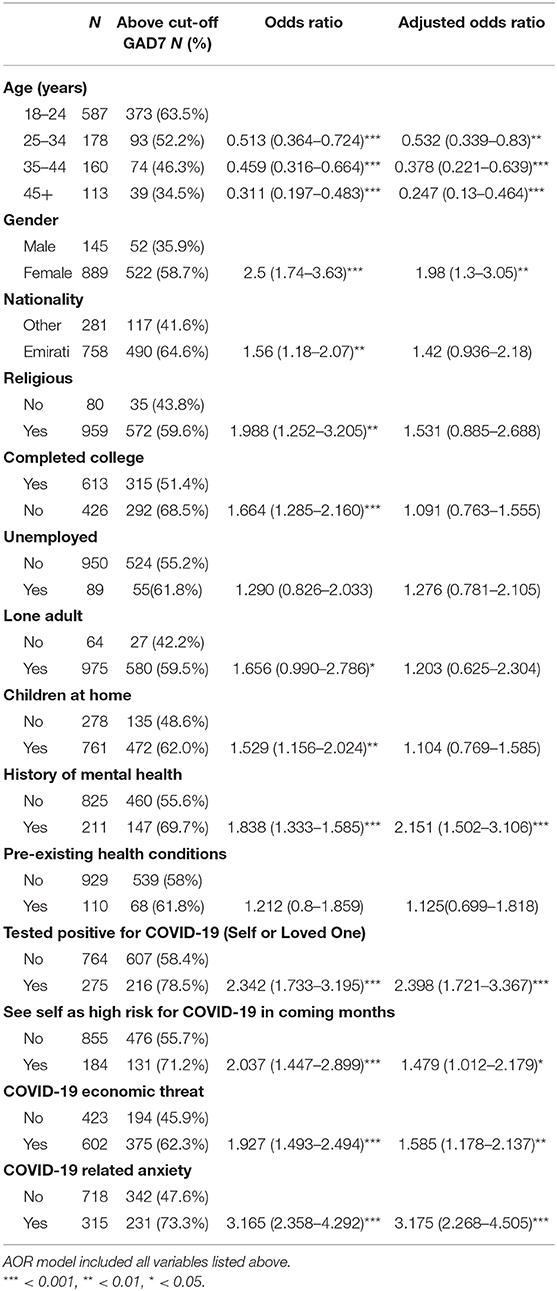

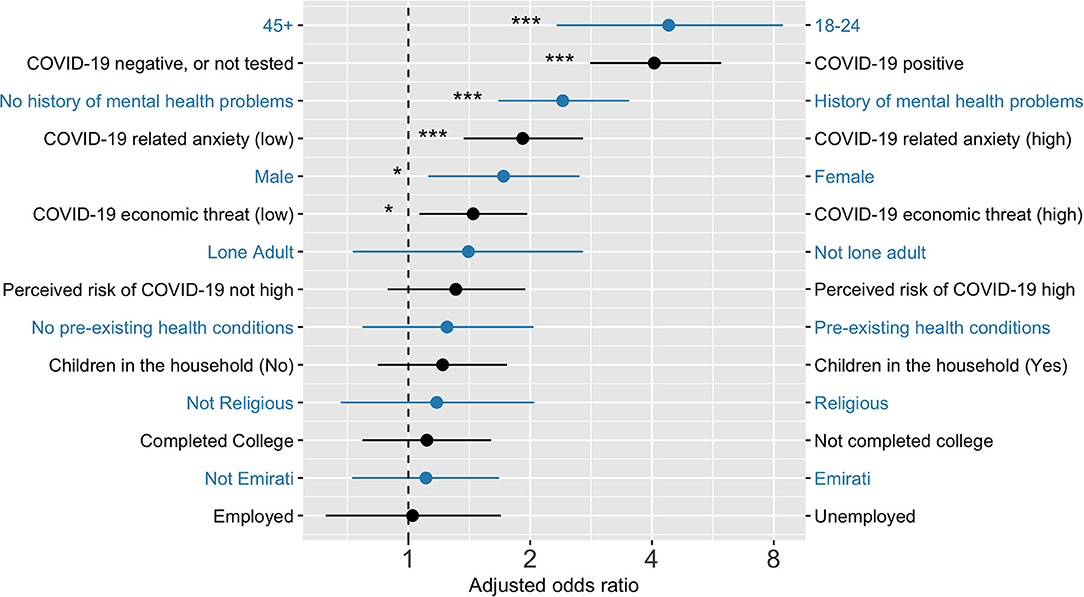

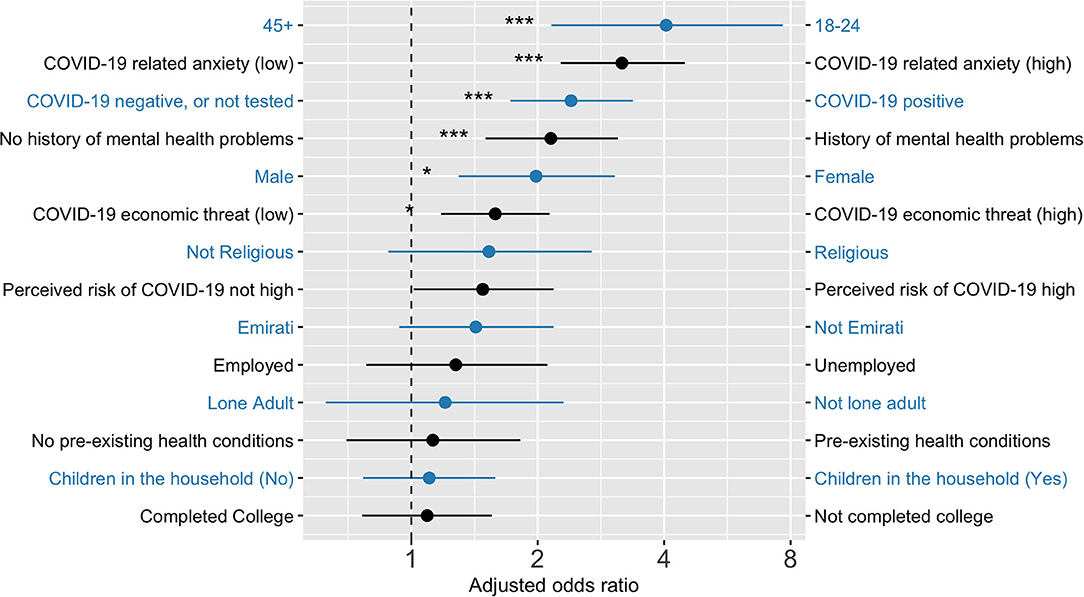

Bivariate and multiple logistic regressions were done with R (26), using generalized linear models in the base package. Two binary logistic regression models were used to predict caseness on Anxiety (GAD7) and Depression (PHQ8), computing bivariate odds ratios (OR) and multivariate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) for all predictor variables. The predictor variables were age, gender, education, employment status, citizenship, lone adult, number of children in household, pre-existing health condition, mental health history, COVID-19 infection status (self and other), and personal perceptions about risk of infection over the following month. The details of these analysis are detailed in Tables 5 and 6 with adjusted odds ratios clearly illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 5. Bivariate (OR) and multivariate (AOR) logistic regression predicting PHQ8 depressive symptom scores above cut-off.

Table 6. Bivariate (OR) and multivariate (AOR) logistic regression predicting GAD7 anxiety symptom scores above cut-off.

Figure 1. Adjusted odd ratios from a logistic regression predicting PHQ8 depressive symptom scores. Note: 18–24 years age group had significantly higher odds of depression and anxiety when compared to all other ag groups. Figure built using https://github.com/SourCherries/odds-forest. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2. Adjusted odd ratios from a logistic regression predicting GAD7 anxiety symptom scores. Note: 18–24 years age group had significantly higher odds of depression and anxiety when compared to all other ag groups. Figure built using https://github.com/SourCherries/odds-forest. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Similar variables were statistically significantly associated with both depression and anxiety, most notably younger age, being female, having a history of mental health problems, self or loved ones testing positive for COVID-19, and having high levels of COVID-related anxiety and economic threat.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous research exploring the psychosocial correlates of infectious illness pandemics on the population of the UAE, or the broader Arab world. Even globally, the literature on the potential mental health implications of previous pandemics is relatively scarce. There are a few studies, primarily from the Far East, which focused on the SARS (8–10) and the H1N1 (27) pandemics of the first decade of the present century. With the notable exception of work undertaken in Canada (28), these earlier studies generally reported elevated levels of psychopathology (anxiety, depression) during the respective outbreaks, with their primary focus being healthcare workers and those who survived the illnesses The present study, however, explored depression, anxiety and the psychosocial correlates among a general community sample during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was during the month of April, shortly after the national response (curfews, social distancing, working from home and the closure of retail and recreational venues) had been enacted. The primary aim of the study was to identify psychosocial and specific COVID-related variables that were associated with elevated levels of depression and anxiety. Identifying such variables can potentially help target support to vulnerable groups. A secondary aim was to assess levels of depression and anxiety, with the expectation that, relative to earlier regional surveys, symptomatology would be elevated.

There were several statistically significant variables associated with elevated depressive symptoms (scores 10 and above on the PHQ8). After age group, the foremost correlate was having tested positive for COVID-19 or having a similarly infected close friend or relative (COVID-19 positive). This finding is similar to data reported from a general survey in the UK (3). Also, in line with the UK survey, was the observation that rates of depression and anxiety were highest among the youngest age group (18–24 years). This finding is particularly significant for the UAE, which has a relatively youthful population (19). Much of the economic burden associated with depression arises from the relatively early age of onset and it's typically chronic course, having younger individuals experience depression is particularly problematic from the health economics perspective. The observation of poorer mental health among youth in the UAE, and elsewhere, may reflect a matrix of despair about the future. From the climate crisis to the employment-related threat of artificial intelligence, these are concerns that may be experienced more acutely by people who expect to witness them within their own lifetimes. A further correlate of depression in the present study was a pre-existing history of mental health problems, as assessed by simple self-report item on the survey. It might be that the pandemic, and the necessary response to it, exacerbate pre-existing morbidities and perhaps contribute to relapse in the vulnerable. Common mental health conditions, such as depression, have a chronic course and relapse is common with a mean of four major lifetime episodes (29). Furthermore, stressful life events, particularly those that disrupt social rhythms (which is likely if people are confined to home), are often implicated in the onset and reoccurrence of mood disorders (30, 31). As has frequently been observed, female gender was associated with a higher risk of having elevated anxiety and depressive symptoms. Such gender differences are typically explained in terms of gender-role socialization processes that lead to females being more likely to adopt passive ruminative responses to negative moods (32, 33). These ruminative response styles appear to represent a cognitive vulnerability in the context of depression (34, 35). A previous, large-scale, community survey undertaken in the UAE also reported females as being at greater risk for depression compared to their male compatriots (14). Cultural norms relating to gender-role socialization in the UAE may also play a role in the elevated rates of depression and anxiety observed in the current study. The final two variables associated with depression were specific to the current pandemic: COVID-19 related anxiety and COVID-19 economic threat (financial worries). This finding accords with the extensive literature on the links between economic/financial insecurity and depression (36).

The factors associated with elevated generalized anxiety symptoms were similar to those correlated with depression, with the addition of perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 in the next month. Elevated perceived risk of contagion would fit with ideas that trait anxiety leads to heightened risk perceptions and estimates (37).

There are perhaps also insights to be gained from noting the variables that, at least in the UAE context, were not associated with elevated depression or anxiety; notably religion, and having children in the household. Religion has previously been found to be a protective factor against depression (38–40) but in the present study it was not. However, we only assessed religion as an identity (affiliation) rather than an individual's levels of religious commitment. Having children at home during the pandemic was associated with depression in a similar COVID-19 survey undertaken in the UK (3). Having children at home while working from home may prove stressful for some families. However, in the UAE, among citizens, it is not uncommon to find three generations of the same family living in one household along with extended family members (17). In the present study, the mean number of people (children and adults) per house, for Emirati citizens, was 8.84 (SD = 4.29), for non-citizens the mean was 3.64 (SD = 2.62). Larger households might reduce the stress of having children at home, through increased support with home-learning and social support in general. Surprisingly, however, household size was not associated with levels of COVID-19-related anxiety. Given that there is a higher risk of infectious disease transmission in larger households (18), this may reflect an area of focus for future health messaging in the context of infectious illness outbreaks in the UAE.

A secondary aim of the study was exploring changes in symptom levels (depression and anxiety) relative to previous, pre-pandemic, regional survey work. The majority of recently published studies, exploring depression and anxiety in the UAE, tend to focus on clinical populations. Alsaadi et al. (41), for example, explored depressive symptoms among multiple sclerosis patients from the UAE, reporting a prevalence of 17.6% for depression and 20% for anxiety. Similarly, Alsaadi et al. (42) report a prevalence of 26.9% for depression and 25% for anxiety among UAE patients diagnosed with epilepsy. Despite chronic health conditions being associated with elevated levels of depression (43), both of these reasonably contemporaneous studies reported lower rates of depression and anxiety than the current study; 58.4 and 55.7% for depression and anxiety, respectively. Similarly, in a non-clinical sample of 302 medical residents in the UAE, depression rates ranged from 6 to 33% depending on residents' medical specialty (44). However, it should be noted that web-based surveys can be prone to self-selection bias (the most anxious and depressed are keenest to take the survey). Furthermore, it should be noted that differences in methods of data collection and mental health assessment make formal, between-studies, comparisons difficult. However, the high rates in the present study are likely, at least in part, to be related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent infection prevention and control measures.

This study has several important limitations. Firstly, the sample was not representative of the entire UAE population. Notably absent were male workers in fields such as construction and other manual endeavors. Reaching this group was beyond the scope of the present study based on time constraints and the necessary restrictions placed on movement during April 2020. Another important limitation is the correlational nature of the study, rendering all causal and temporal inferences tentative at best. However, obtaining a preliminary understanding of the psychosocial factors associated with elevated levels of depression and anxiety among segments of the UAE population during the pandemic may help inform public mental health plans for current and future outbreaks of infectious illness. Furthermore, post-pandemic economic recovery is likely to be significantly impacted by societal levels of mental ill-health. Exploring potential risk and resilience factors associated with psychological well-being may also help inform broader strategies aimed at national economic recovery.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the ethical approval for the study requires that only anonymized data may be shared on request with verified researchers. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Prof. Justin Thomas, SnVzdGluLlRob21hc0B6dS5hYy5hZQ==.

The study received ethical clearance from the research ethics committees of Zayed University (R201213) and the UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention (MOHAP/DXB-REC/MMM/No. 49/2020). All participants provided informed consent prior to undertaking the survey.

JT: study design, write up, and project management. MB and RB: study design and write up. MV and JG: write up. CG: analysis and data visualization. MM: translation and write up. AM: translation, survey development, and data acquisition. MF and TA: review and data acquisition. All authors provided approval for publication of the manuscript content and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. The Lancet. COVID-19: fighting panic with information. Lancet. (2020) 395:537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30379-2

2. Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:547–60. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

3. Shevlin M, McBride O, Murphy J, Miller JG, Hartman TK, Levita L, et al. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress, and COVID-19 related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open. (2020) 6:e125. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.109

4. Lei L, Huang X, Zhang S, Yang J, Yang L, Xu M. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in Southwestern China. Med Sci Monit. (2020) 26:e924609. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924609

5. Grey I, Arora T, Thomas J, Saneh A, Tomhe P, Abi-Habib R. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 293:113452. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113452

6. Pirutinsky S, Cherniak AD, Rosmarin DH. COVID-19, mental health, and religious coping among american orthodox jews. J Religion Health. (2020) 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01070-z

7. Shi L, Lu Z-A, Que J-Y, Huang X-L, Liu L, Ran M-S, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. (2020) 3:e2014053. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053

8. Chan SM, Chiu FK, Lam CW, Leung PY, Conwell Y. Elderly suicide and the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2006) 21:113–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.1432

9. Lee AM, Wong JG, McAlonan GM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Sham PC, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry. (2007) 52:233–40. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200405

10. Mak IW, Chu CM, Pan PC, Yiu MG, Chan VL. Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2009) 31:318–26. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.03.001

11. Hidaka BH. Depression as a disease of modernity: explanations for increasing prevalence. J Affect Disord. (2012) 140:205–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.036

12. Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJL, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. (2013) 10:e1001547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547

13. Abou-Saleh MT, Ghubash R, Daradkeh TK. Al Ain Community Psychiatric Survey. I. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. (2001) 36:20–8. doi: 10.1007/s001270050286

14. Ghubash R, Daradkeh TK, Al-Muzafari SMA, El-Manssori ME, Abou-Saleh MT. Al Ain Community Psychiatric Survey IV: socio-cultural changes (traditionality-liberalism) and prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. (2001) 36:565–70. doi: 10.1007/s001270170008

15. Ghubash R, El-Rufaie OE, Zoubeidi T, Al-Shboul QM, Sabri SM. Profile of mental disorders among the elderly United Arab Emirates population: sociodemographic correlates. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004:344–51. doi: 10.1002/gps.1101

16. Bener A, Ghuloum S, Abou-Saleh MT. Prevalence, symptom patterns and comorbidity of anxiety and depressive disorders in primary care in Qatar. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. (2012) 47:439–46. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0349-9

18. House T, Keeling MJ. Household structure and infectious disease transmission. Epidemiol Infect. (2009) 137:654–61. doi: 10.1017/S0950268808001416

19. AlMunajjed M, Sabbagh K. Youth in GCC Countries: Meeting the Challenge. Abu Dhabi: Booz & Company (2011).

20. Williams JR, Manfredi P. Ageing populations and childhood infections: the potential impact on epidemic patterns and morbidity. Int J Epidemiol. (2004) 33:566–72. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh098

21. Funk S, Salathé M, Jansen VAA. Modelling the influence of human behaviour on the spread of infectious diseases: a review. J Royal Soc Interface. (2010) 7:1247–56. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0142

22. Prince Nelson SL, Ramakrishnan V, Nietert PJ, Kamen DL, Ramos PS, Wolf BJ. An evaluation of common methods for dichotomization of continuous variables to discriminate disease status. Commun Stat Theory Methods. (2017) 46:10823–34. doi: 10.1080/03610926.2016.1248783

23. Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affective Disord. (2009) 114:163–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026

24. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

25. Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. (2008) 46:266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

26. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2020). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/

27. Cowling BJ, Ng DMW, Ip DKM, Liao Q, Lam WWT, Wu JT, et al. Community psychological and behavioral responses through the first wave of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic in Hong Kong. J Infect Dis. (2010) 202:867–76. doi: 10.1086/655811

28. Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. (2004) 10:1206–12. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703

29. Teasdale JD, Williams JMG, Soulsby JM, Segal ZV. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J Consulting Clin Psychol. (2000) 68:615–23. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.615

30. Kessler RC. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu Rev Psychol. (1997) 48:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191

31. Malkoff-Schwartz S, Frank E, Anderson BP, Hlastala SA, Luther JF, Sherrill JT, et al. Social rhythm disruption and stressful life events in the onset of bipolar and unipolar episodes. Psychol Med. (2000) 30:1005–16. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799002706

32. Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Abnormal Psychol. (2000) 109:504–11. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504

33. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Blair EW, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectiv Psychol Sci. (2008) 3:400–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

34. Alloy LB, Abrahamson LY, Wayne G, Whitehouse ME. Depressogenic cognitive styles: predictive validity, information processing and personality characteristics, and developmental origins. Behav Res Therapy. 1999:503–31. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00157-0

35. Mongrain M, Blackburn S. Cognitive vulnerability, lifetime risk, and the recurrence of major depression in graduate students. Cogn Therapy Res. (2005) 29:747–68. doi: 10.1007/s10608-005-4290-7

36. Bridges S, Disney R. Debt and depression. J Health Econ. (2010) 29:388–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.02.003

37. Notebaert L, Masschelein S, Wright B, MacLeod C. To risk or not to risk: anxiety and the calibration between risk perception and danger mitigation. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. (2016) 42:985–95. doi: 10.1037/xlm0000210

38. Abdel-Khalek AM. Religiosity, subjective well-being, and depression in Saudi children and adolescents. Mental Health Religion Culture. (2009) 12:803–15. doi: 10.1080/13674670903006755

39. Abdel-Khalek AM, Eid GK. Religiosity and its association with subjective well-being and depression among Kuwaiti and Palestinian Muslim children and adolescents. Mental Health Religion Culture. (2011) 14:117–27. doi: 10.1080/13674670903540951

40. Miller L, Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Sage M, Tenke CE, Weissman MM. Religiosity and major depression in adults at high risk: a 10-years prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. (2012) 169:89–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10121823

41. Alsaadi T, El Hammasi K, Shahrour TM, Shakra M, Turkawi L, Mudhafar A, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among patients with multiple sclerosis attending the MS clinic at Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, UAE: Cross-Sectional Study. Mult Scler Int. (2015) 2015:487159. doi: 10.1155/2015/487159

42. Alsaadi T, Kassie S, El Hammasi K, Shahrour TM, Shakra M, Turkawi L, et al. Potential factors impacting health-related quality of life among patients with epilepsy: results from the United Arab Emirates. Seizure. (2017) 53:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.10.017

43. Simon GE. Treating depression in patients with chronic disease: recognition and treatment are crucial; depression worsens the course of a chronic illness. West J Med. (2001) 175:292–3. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.5.292

Keywords: COVID-19, depression, anxiety, Arab, UAE, pandemic

Citation: Thomas J, Barbato M, Verlinden M, Gaspar C, Moussa M, Ghorayeb J, Menon A, Figueiras MJ, Arora T and Bentall RP (2020) Psychosocial Correlates of Depression and Anxiety in the United Arab Emirates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 11:564172. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.564172

Received: 20 May 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020;

Published: 10 November 2020.

Edited by:

Antonio Ventriglio, University of Foggia, ItalyCopyright © 2020 Thomas, Barbato, Verlinden, Gaspar, Moussa, Ghorayeb, Menon, Figueiras, Arora and Bentall. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Justin Thomas, SnVzdGluLlRob21hc0B6dS5hYy5hZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.