- 1Institute of Psychiatry, Università degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale, Novara, Italy

- 2S.C. Psichiatria, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Maggiore della Carità, Novara, Italy

Alexithymia is of great interest as an outcome predictor of recovery from anorexia nervosa, since it may interfere with both treatment compliance and patients’ ability to benefit from the adopted interventions. For this reason, in the last years new treatment approaches targeting emotion identification, expression, and regulation have been applied and tested. Using the PRISMA methodology, we performed a scoping review of the literature about treatment outcome in anorexia nervosa, in terms of changes in alexithymia as assessed by its most commonly used self-report measure, the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS). The Medline and Scopus databases were searched, and articles were included if matching the following criteria: dealing with patients affected by anorexia nervosa, without limits of age; involving the application of any kind of targeted therapy or treatment; assessing alexithymia and the effect of a treatment intervention on alexithymia, using the TAS. Ten studies were eventually included; overall, according to the selected studies, alexithymia levels often remain high even after specific treatment. Further research aimed at a deeper understanding of the actual impact of alexithymia on the outcome of anorexia, as well as exploring alternative treatment strategies for alexithymia in eating disorders (EDs), are warranted.

Introduction

Alexithymia is defined as a difficulty and inability in identifying and describing feelings and emotions (1): alexithymic individuals usually show a paucity of words to describe their affective status, and find it difficult distinguishing feelings from physical sensations. Furthermore, alexithymia is characterized by a diminution of fantasy and a concrete and externally-oriented thinking style (2). It is likely a stable personality trait reflecting an impairment of emotion regulation (3, 4), rather than a state-dependent phenomenon linked to depression or to clinical status (5, 6).

Impaired emotional functioning and alexithymic traits are core features of anorexia nervosa, both in the adolescent and adult population (7–15): they seem to be independent from depressive symptoms and eating disorder severity (16–18) and express themselves as a concrete, reality-based cognitive style and a poor inner emotional and fantasy life.

A “cognitive-affective” division (19) has been suggested to describe the experience of patients with eating disorders (EDs) when trying to translate their thoughts at a cognitive level into what is felt from an emotional standpoint. The emotional difficulties of individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN) may not depend on a primary impairment in emotion recognition, but rather on inhibition or avoidance occurring after a proper acknowledgment of others’ emotions (20), possibly due to patients’ feelings of being overwhelmed by over-control and anxious worry (21). Alexithymic traits in AN may cause patients avoiding or regulating the experience of emotions, especially those perceived as negative or disruptive (22), with inappropriate behaviors (restriction, binges, purges, body checking behaviors) (23), leading to a gap between the inner experience of negative affect and its expression (13). Actually, also in a non-clinical sample of undergraduate women, alexithymic individuals, compared to non-alexithymic ones, had more body checking behaviors, greater body dissatisfaction, and higher potential risk for EDs (24).

Implications at the social level of alexithymia and emotional difficulties (such as emotional avoidance and poor regulation), include low social emotional intelligence (25), problems with intimacy, attachment and social communication or interactions (26–29), and social anhedonia (30, 31).

Moreover, alexithymia and emotion regulation difficulties have been shown to have an impact on the course and maintenance of anorexia (12, 15, 32, 33), and on treatment outcome and recovery (34, 35). Actually, the lack of insight and the externally-oriented thinking style typical of alexithymia may interfere with treatment compliance and with patients’ ability to benefit from interventions, especially psychotherapy ones (36).

According to these clinical observations, in the last years the need to explore new treatment approaches targeting emotion identification, expression and regulation has emerged, with the aim of fostering the process of recovery, enhancing quality of life (27) and improving long-term outcomes in the ED population (32). Another issue which should not be overlooked is that, notwithstanding patients’ primary psychiatric diagnosis, increasing evidence suggests that alexithymia may play a role as risk factor for suicide, often mediated by depressive symptoms (37, 38). Biological correlates of the relationship between alexithymia and suicidal behaviors have been suggested, including for instance homocysteine dysregulation (39). This evidence further supports the importance to screen for alexithymia in the everyday clinical practice with psychiatric patients, including those suffering from EDs (40). The aim of the current scoping review was to assess treatment outcome in AN in terms of changes in alexithymia as assessed by its most commonly used self-report measure, the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS).

Methods

A scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA Statement; (41)]. The Medline and Scopus databases were searched on August 30th, 2019, and on September 2nd, 2019. For Medline, the following keywords were used: [(anorexia nervosa) AND (Toronto Alexithymia Scale)] AND ((therapy) OR treatment). Scopus was searched with the following research string: [ALL (“anorexia nervosa”) AND ALL (Toronto AND Alexithymia AND Scale) AND ALL (treatment OR therapy)] AND [LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)] AND [LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)].

Two independent reviewers (EG and CG) assessed the articles identified by the above described key words. To be included in the review, studies had to: (a) be clinical trials dealing with patients affected by AN, without limits of age; (b) involve the application of any kind of targeted therapy or treatment; (c) assess alexithymia and the effect of a treatment intervention on alexithymia, using the TAS. Only articles in English were considered eligible. The presence of a control group was not considered an inclusion criterion. Studies which did not match the inclusion criteria described above were excluded. Possible disagreement between reviewers was resolved by joint discussion with a third review author (PZ). Quality of studies was assessed with the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) (42) by the reviewers who assessed the articles (EG and CG).

Data extracted from the selected studies were recorded in a datasheet using a standardized coding form, including the following categorical and numerical variables: general information about the study (author/s, year of publication, title, journal title, volume, pages, country, study type), sample features (sex, age, BMI, years of illness, diagnosis, treatment; medical and psychiatric comorbidities; sample size, number in experimental group, number in control group, lost at follow-up), setting (inpatient, outpatient…), type of intervention (group, individual, setting…), questionnaires used, study outcome (primary or secondary), main study results.

Results

Selection Process

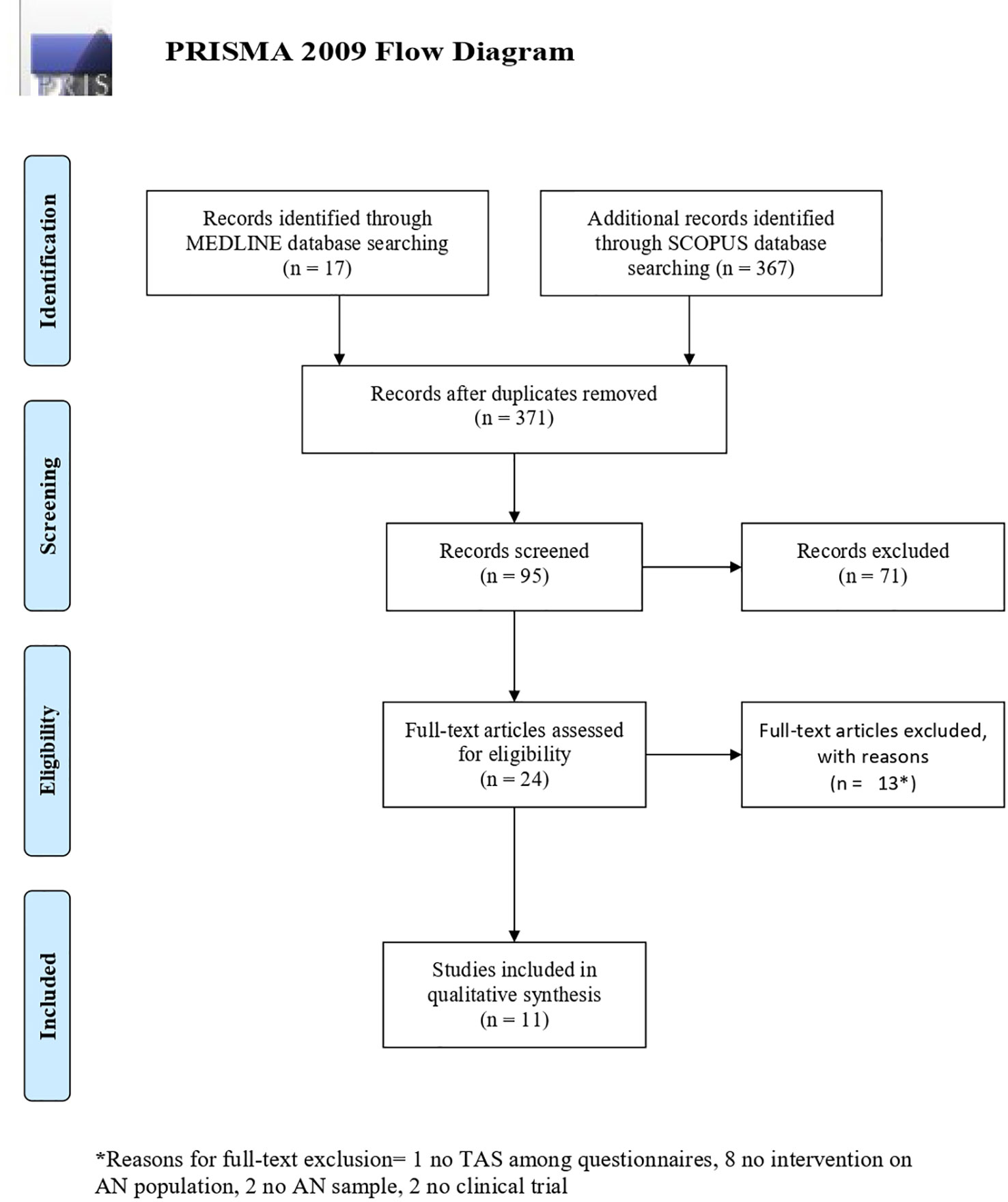

As described in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) (43), the initial search identified 384 titles (17 from Medline, 367 from Scopus); after removing 13 duplicates, titles were screened first, and those clearly not in line with the purpose of the review were excluded (N = 276). Then abstracts were assessed, leading to the exclusion of 71 records, and last full texts were read, eventually leading to the inclusion of 10 papers (2, 15, 32, 44–50) in the qualitative synthesis.

Quality Assessment

The NOS scores for the included studies ranged from 1 to 6, with a mean score of 3.9 ± 1.59 (SD).

Description of Study Features

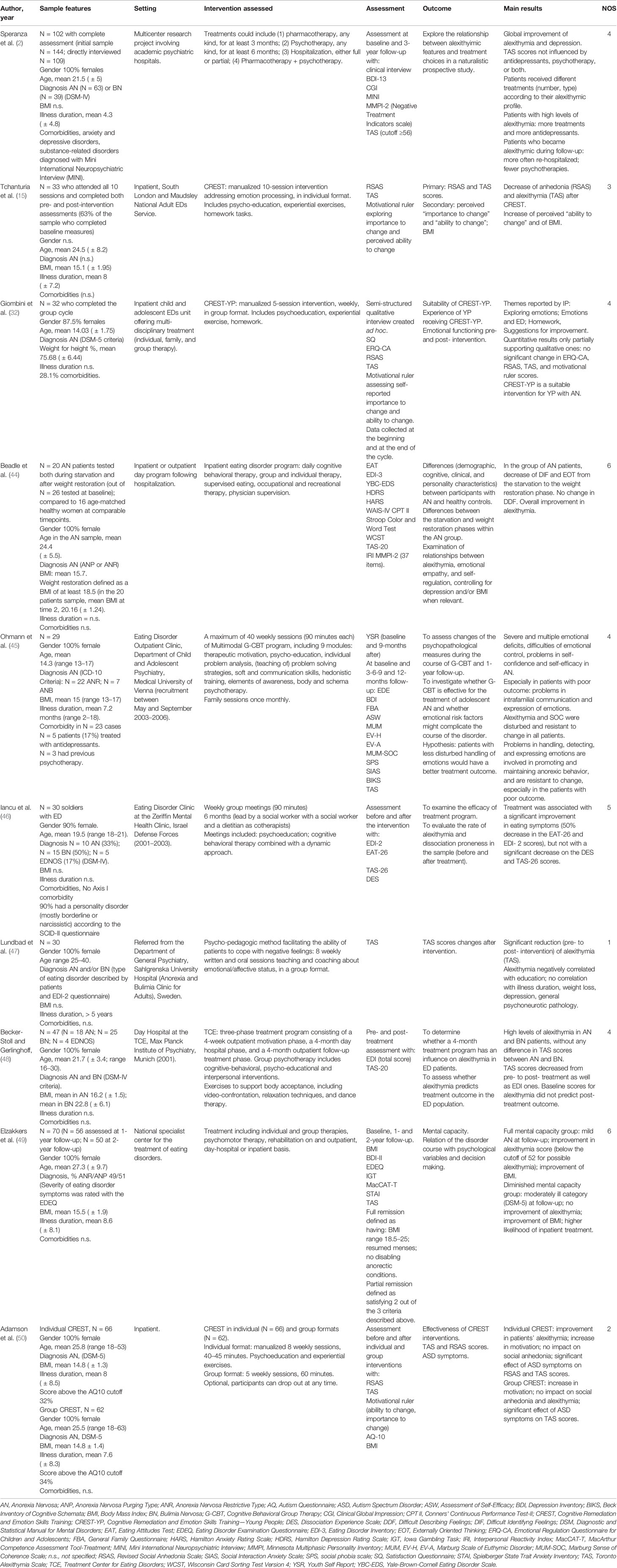

The main features of the selected studies are shown in Table 1.

Details about treatment were reported for the approaches described below; in the other cases, no specific details were described apart from those reported in Table 1.

CREST (15, 51–53) is a low-intensity individual manualized treatment for inpatients with severe AN, based on the cognitive interpersonal model. It targets rigid and detail-focused thinking styles but also has a strong emphasis on emotion recognition skills and emotion management and expression. The aim is to help patients learn about the function of emotions (including the communication of needs to self and others), and to improve skills in emotion labeling, identification, and tolerance in self and others.

Lunbad and coworkers (47) described in detail the group psycho-pedagogic method applied at the Anorexia & Bulimia Clinic for Adults at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital. According to the theoretical premise that alexithymia implies an inability to handle negative feelings, eventually requiring a “protective” or “blocking” ingredient (ED symptoms). The aim of the method is to help patients cope with negative feelings.

Group Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (G-CBT) as described by Ohmann et al. (45) includes the following modules: therapeutic motivation, psycho-education, individual problem analysis, (teaching of) problem solving strategies, soft and communication skills, hedonistic training, elements of awareness, body and schema psychotherapy (54). While the primary therapeutic goals are weight gain and improvement of eating behavior, the secondary goal is improved emotional functioning, including alexithymia measures.

Becker-Stoll and Gerlinghoff (48) described a three-phase treatment program (4-week outpatient motivation phase, 4-month day hospital phase, 4-month outpatient follow-up), including group cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, psycho-educational and interpersonal interventions.

Iancu et al. (46) adopted a group therapy combining a cognitive-behavioral and a dynamic approach; with more detail, the latter proposes a dynamic understanding of ED symptoms as an externalization of an unsolved conflict.

Discussion

Overall, according to the studies included in the review, alexithymia levels sometimes remain high even after specific treatment, while changes and improvements may occur in other outcome indicators (e.g. body mass index, eating symptomatology, motivation).

Some studies clearly failed to find a positive impact of treatment on alexithymia as assessed with the TAS (32, 45, 46). On the other hand, others supported an improvement of alexithymia after treatment (2, 15, 44, 47, 48), which was represented by CREST (15), a mixed approach including different types of treatment (2, 44), a 4-month day hospital treatment (48), and a psycho-pedagogic intervention (47), respectively (see Table 1 for more details). Last, mixed findings have been reported by a couple of studies. An improvement of TAS scores was reported in a subgroup of patients with AN (full mental capacity) but not in another (diminished mental capacity) (49). Furthermore, CREST was described as effective in reducing alexithymia when offered in an individual format, but not in a group one (50).

General Information

All studies but one (2) involved a single center. Most studies were performed in a hospital setting, on inpatients; only four studies included outpatients (44, 45, 48, 49). Samples size ranged from 29 to 168 patients. One study (44) included also a control group, composed by 16 age-matched healthy women.

Participants’ Features

The studies included in this review involved patients with an age range from 12 to 63 years old; two studies (32, 45) were specifically focused on an adolescent population. Most studies included only female patients, while two (32, 46) assessed both genders. From a clinical standpoint, four of the 10 studies selected for this review involved patients with different types of EDs: AN-R; AN-P; BN; EDNOS (2, 46–48), while six studies included only AN patients (15, 32, 44, 45, 49, 50). More specifically, diagnosis was made according to DSM-IV criteria in three studies (2, 46, 48), to ICD-10 criteria in one study (45) and to DSM-5 criteria in another one (50). In 2 studies (47, 49) the type of ED was assessed using different questionnaires (respectively EDI-2 and EDEQ). The remaining five studies did not specify the diagnostic criteria used (15, 32, 44, 47, 49). Patients’ BMI ranged from 13 to 21.4; illness duration, when specified, ranged from 1 month to more than 5 years. Comorbidities were specified in four studies (2, 32, 45, 46).

Intervention Features

All studies but two (2, 47) applied cognitive interventions (15, 32, 44–46, 48, 50). More specifically, patients enrolled in three studies (15, 32, 50) were treated with CREST, in a group format; furthermore, Adamson et al. (50) used CREST in an individual therapy setting as well. Seven studies (15, 32, 45–48, 50) included psycho-pedagogic methods to facilitate the ability of patients to cope with negative feelings, particularly associated to body appearance and food assumption. Speranza et al. (2) provided different treatment approaches, such as pharmacotherapy (for at least 3 months), psychotherapy (for at least 6 months), hospitalization (either full or partial), and a combination of pharmacotherapy with psychotherapy. Ohman and coworkers (45) also offered once-monthly family sessions, in the context of 40 weekly sessions of multimodal cognitive behavioral group therapy (G-CBT) program.

Assessment

All studies but one (2, 15, 32, 45–50) assessed patients with several questionnaires (either self-report measurers or clinician-rated interviews) both at baseline and after the intervention. Beadle et al. (44) tested patients with the TAS only.

Outcomes

In line with the inclusion criteria adopted, alexithymia as outcome after the intervention was assessed by all studies (2, 15, 32, 44–50). Moreover, four studies (2, 45, 46, 48) evaluated its possible role as predictor of treatment outcome in the AN population.

Strengths and Limitations

The current paper provides an up-to-date review of the literature on alexithymia and treatment outcome in AN. Despite the clinical relevance of alexithymia, the number of published studies about its changes after treatment are somewhat limited; the possibility to compare the results of these studies is hindered by their heterogeneity and by methodological issues. Besides the previous review study by Pinna et al. (55), that focused on the implications of alexithymia as a predictor of treatment outcome in subjects affected by ED, there are no similar studies on interventions for alexithymia in anorexic patients, making the current review useful to the community of researchers in the field of EDs. Some limitations of this scoping review should be underscored: first, only two databases (i.e., Medline and Scopus) were searched to identify relevant articles written in English language, with potential loss of valuable additional information. The restriction to published studies could per se represent a bias in systematic reviews of effectiveness. Despite we focused on TAS as outcome measure in patients with AN undergoing any kind of treatment, samples sometimes included also patients with other EDs, and it was not always possible to rule out results pertaining only those with a diagnosis of AN. Last, while we focused on the TAS as the most used tool for the assessment of alexithymia, and this ensures the homogeneity of results, this choice obviously lead to the exclusion of all those studies using other rating scales for alexithymia.

On the other hand, we adopted restrictive inclusion criteria and applied the PRISMA methodology for the selection process; furthermore, we assessed the quality of the studies included in this review.

Nonetheless, since our aim was to conduct a scoping review of the literature we did not perform a quantitative data synthesis nor meta-analysis. This represents a further limitation of the current study; a meta-analytic approach would certainly represent an interesting research direction for the future to allow drawing clear, evidence-based conclusions about the clinical implications of the findings that have emerged from our research.

Conclusions

A high rate of individuals with AN achieve incomplete recovery following treatment. The identification of outcome predictors such as alexithymia is crucial, as well as that of treatments specifically targeting these predictors (56–62).

Further studies aimed at a deeper understanding of the actual impact of alexithymia on the outcome of anorexia are warranted, as well as researches exploring alternative treatment strategies for alexithymia in EDs.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

CG and PZ contributed to the conception and design of the work. EG and CG independently triaged the titles and abstracts to remove those that were clearly inappropriate. The remaining papers, to be included, had to satisfy all the predetermined eligibility criteria. Possible disagreements regarding study inclusion were resolved by discussion with PZ. After selection of the relevant studies, EG and CG independently extracted and tabulated data on study design and outcome data using a standard form. CG and EG drafted the manuscript. PZ revised it critically for important intellectual content.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Guillen V, Santos B, Munoz P, Fernandez de Corres B, Fernandez E, Perez I, et al. Toronto alexithymia scale for patients with eating disorder: of performance using the nonparametric item response theory. Compr Psychiatry (2014) 55(5):1285–91. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.03.020

2. Speranza M, Loas G, Guilbaud O, Corcos M. Are treatment options related to alexithymia in eating disorders? Results from a three-year naturalistic longitudinal study. Biomed Pharmacother (2011) 65(8):585–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2010.01.009

3. Aleman A. Feelings you can’t imagine: towards a cognitive neuroscience of alexithymia. Trends Cogn Sci (2005) 9:227–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.002

4. Wingbermuhle K, Theunissen H, Verhoeven WMA, Kessels RPC, Egger JIM. The neurocognition of alexithymia: evidence from neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies. Acta Neuropsychiatrica (2012) 24:67–80.

5. Luminet O, Bagby RM, Taylor GJ. An evaluation of the absolute and relative stability of alexithymia in patients with major depression. Psychother Psychosom (2001) 70(5):254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.01.003

6. Porcelli P, Bagby RM, Taylor GJ, De Carne M, Leandro G, Todarello O. Alexithymia as predictor of treatment outcome in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosom Med (2003) 65(5):911–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000089064.13681.3b

7. Courty A, Godart N, Lalanne C, Berthoz S. Alexithymia, a compounding factor for eating and social avoidance symptoms in anorexia nervosa. Compr Psychiatry (2015) 56:217– 228. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.09.011

8. Torres S, Guerra MP, Lencastre L, Miller K, Vieira FM, Roma-Torres A, et al. Alexithymia in anorexia nervosa: the mediating role of depression. Psychiatry Res (2015) 225(1-2):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.10.023

9. NICE. Eating Disorders: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders. National Institute for Clinical Excellence: London (2004).

10. Treasure J, Claudino AM, Zucker N. Eating disorders. Lancet (London England) (2010) 375(9714):583–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61748-7

11. Harrison A, Sullivan S, Tchanturia K, Treasure J. Emotional functioning in eating disorders: attentional bias, emotion recognition and emotion regulation. Psychol Med (2010) 40(11):1887–97. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000036

12. Rhind C, Mandy W, Treasure J, Tchanturia K. An exploratory study of evoked facial affect in adolescent females with anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res (2014) 220(1–2):711–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.057

13. Davies H, Swan N, Schmidt U, Tchanturia K. An experimental investigation of verbal expression of emotion in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2012) 20(6):476–83. doi: 10.1002/erv.1157

14. Davies H, Schmidt U, Stahl D, Tchanturia K. Evoked facial emotional expression and emotional experience in people with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord (2011) 44(6):531–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.20852

15. Tchanturia K, Dapelo MAM, Harrison A, Hambrook D. Why study positive emotions in the context of eating disorders? Curr Psychiatry Rep (2015) 17(1):537. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0537-x

16. Speranza M, Loas G, Wallier J, Corcos M. Predictive value of alexithymia in patients with eating disorders: a 3-year prospective study. J Psychosom Res (2007) 63(4):365–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.03.008

17. Taylor GJ, Parker JD, Bagby RM, Bourke MP. Relationships between alexithymia and psychological characteristics associated with eating disorders. J Psychosom Res (1996) 41(6):561–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00224-3

18. Bourke MP, Taylor GJ, Parker JD, Bagby RM. Alexithymia in women with anorexia nervosa. A preliminary investigation. Br J Psychiatry (1992) 161:240–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.2.240

19. Jenkins PE, O’Connor H. Discerning thoughts from feelings: the cognitive-affective division in eating disorders. Eat Disord (2012) 20(2):144–58. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.654058

20. Gramaglia C, Ressico F, Gambaro E, Palazzolo A, Mazzarino M, Bert F, et al. Alexithymia, empathy, emotion identification and social inference in anorexia nervosa: a case-control study. Eat Behav (2016) 22:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.03.028

21. Torres S, Guerra MP, Lencastre L, Roma-Torres A, Brandão I, Queirós C, et al. Cognitive processing of emotions in anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2011) 19(2):100–11. doi: 10.1002/erv.1046

22. Goodsitt A. Self-regulatory disturbances in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord (1983) 2(3):51–60. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198321

23. Espeset EM, Gulliksen KS, Nordbø RH, Skårderud F, Holte A. The link between negative emotions and eating disorder behaviour in patients with anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2012) 20(6):451–60. doi: 10.1002/erv.2183

24. De Berardis D, Carano A, Gambi F, Campanella D, Giannetti P, Ceci A, et al. Alexithymia and its relationships with body checking and body image in a non-clinical female sample. Eat Behav (2007) 8(3):296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.11.005

25. Gullone E, Taffe J. The emotion regulation questionnaire for children and adolescents (ERQ-CA): a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Assess (2012) 24(2):409–17. doi: 10.1037/a0025777

26. Kyriacou O, Easter A, Tchanturia K. Comparing views of patients, parents, and clinicians on emotions in anorexia: a qualitative study. J Health Psychol (2009) 14(7):843–54. doi: 10.1177/1359105309340977

27. Tchanturia K, Doris E, Fleming C. Effectiveness of cognitive remediation and emotion skills training (CREST) for anorexia nervosa in group format: a naturalistic pilot study. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2014) 22(3):200–5. doi: 10.1002/erv.2287

28. Doris E, Westwood H, Mandy W, Tchanturia K. A qualitative study of friendship in patients with Anorexia Nervosa and possible Autism Spectrum Disorder. Psychology (2014) 5:1338–49. doi: 10.4236/psych.2014.511144

29. Harrison A, Genders R, Davies H, Treasure J, Tchanturia K. Experimental measurement of the regulation of anger and aggression in women with anorexia nervosa. Clin Psychol Psychother (2011) 18:445–52. doi: 10.1002/cpp.726

30. Harrison A, Mountford VA, Tchanturia K. Social anhedonia and work and social functioning in the acute and recovered phases of eating disorders. Psychiatry Res (2014) 218(1–2):187–94. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.007

31. Tchanturia K, Davies H, Harrison A, Fox JRE, Treasure J, Schmidt U. Altered social hedonic processing in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord (2012) 45(8):962–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.22032

32. Giombini L, Nesbitt S, Leppanen J, Cox H, Foxall A, Easter A, et al. Emotions in play: young people’s and clinicians’ experience of ‘Thinking about Emotions’ group. Eat Weight Disord (2019) 24(4):605–14. doi: 10.1007/s40519-019-00646-3

33. Wildes JE, Marcus MD, Cheng Y, McCabe EB, Gaskill JA. Emotion acceptance behavior therapy for anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord (2014) 47(8):870–3. doi: 10.1002/eat.22241

34. Hempel R, Vanderbleek E, Lynch TR. Radically open DBT: targeting emotional loneliness in Anorexia Nervosa. Eat Disord (2018) 26(1):92–104. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2018.1418268

35. Chen EY, Segal K, Weissman J, Zeffiro TA, Gallop R, Linehan MM, et al. Adapting dialectical behavior therapy for outpatient adult anorexia nervosa–a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord (2015) 48(1):123–32. doi: 10.1002/eat.22360

36. Krystal H. Alexithymia and the effectiveness of psychoanalytic treatment. Int J Psychoanal Psychother (1982-1983) 9:353–78.

37. De Berardis D, Fornaro M, Orsolini L, Valchera A, Carano A, Vellante F, et al. Alexithymia and suicide risk in psychiatric disorders: a mini-review. Front Psychiatry (2017) 14(8):148. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00148

38. De Berardis D, Fornaro M, Valchera A, Rapini G, Di Natale S, De Lauretis I, et al. Alexithymia, resilience, somatic sensations and their relationships with suicide ideation in drug naïve patients with first-episode major depression: an exploratory study in the “real world” everyday clinical practice. Early Interv Psychiatry (2019a). doi: 10.1111/eip.12863 [Epub ahead of print]

39. De Berardis D, Olivieri L, Rapini G, Di Natale S, Serroni N, Fornaro M, et al. Alexithymia, suicide ideation and homocysteine levels in drug naïve patients with major depression: a study in the “Real World” clinical practice. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci (2019b) 17(2):318–22. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2019.17.2.318

40. Carano A, De Berardis D, Campanella D, Serroni N, Ferri F, Di Iorio G, et al. Alexithymia and suicide ideation in a sample of patients with binge eating disorder. J Psychiatr Pract (2012) 18(1):5–11. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000410982.08229.99

41. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ (2009) 339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700

42. Wells G, Shea B, O’Connel D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. (2015). Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

43. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med (2009) 6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

44. Beadle JN, Paradiso S, Salerno A, McCormick LM. Alexithymia, emotional empathy, and self-regulation in anorexia nervosa. Ann Clin Psychiatry (2013) 25(2):107–20.

45. Ohmann S, Popow C, Wurzer M, Karwautz A, Sackl-Pammer P, Schuch B. Emotional aspects of anorexia nervosa: results of prospective naturalistic cognitive behavioral group therapy. Neuropsychiatrie (2013) 27(3):119–28. doi: 10.1007/s40211-013-0065-7

46. Iancu I, Cohen E, Yehuda YB, Kotler M. Treatment of eating disorders improves eating symptoms but not alexithymia and dissociation proneness. Compr Psychiatry (2006) 47(3):189–93. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.01.001

47. Lundbad S, Hansson B, Archer T. Affect-group intervention for alexithymia in eating disorders. Int J Emergency Ment Health (2015) 17(1):219–23.

48. Becker-Stoll F, Gerlinghoff M. The impact of a four-month day treatment programme on alexithymia in eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2004) 12(3):159–63. doi: 10.1002/erv.566

49. Elzakkers IFFM, Danner UN, Sternheim LC, McNeish D, Hoek HW, van Elburg AA. Mental capacity to consent to treatment and the association with outcome: a longitudinal study in patients with anorexia nervosa. BJPsych Open (2017) 3(3):147–53. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.116.003905

50. Adamson J, Leppanen J, Murin M, Tchanturia K. Effectiveness of emotional skills training for patients with anorexia nervosa with autistic symptoms in group and individual format. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2018) 26(4):367–75. doi: 10.1002/erv.2594

51. Tchanturia K, Doris E, Mountford V, Fleming C. Cognitive remediation and emotion skills training (CREST) for anorexia nervosa in individual format: self-reported outcomes. BMC Psychiatry (2015) 15(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0434-9

52. Davies H, Fox J, Naumann U, Treasure J, Schmidt U, Tchanturia K. Cognitive remediation and emotion skills training (CREST) for anorexia nervosa: an observational study using neuropsychological outcomes. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2012) 20:211–7. doi: 10.1002/erv.2170

53. Money C, Genders R, Treasure J, Schmidt U, Tchanturia K. A brief emotion focused intervention for inpatients with anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study. J Health Psychol (2011) 16:947–58. doi: 10.1177/1359105310396395

54. Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME. Schema therapy A practitioner"s guide. New York: Guilford Press (2003).

55. Pinna F, Sanna L, Carpiniello B. Alexithymia in eating disorders: therapeutic implications. Psychol Res Behav Manage (2014) 8:1–15. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S52656

56. Bruch H. Anorexia Nervosa: therapy and theory. Am J Psychiatry (1982) 139(12):1531–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.12.1531

57. Hambrook D, Oldershaw A, Rimes K, Schmidt U, Tchanturia K, Treasure J, et al. Emotional expression, self-silencing, and distress tolerance in anorexia nervosa and chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Clin Psychol (2011) 50(3):310–25. doi: 10.1348/014466510X519215

58. Oldershaw A, DeJong H, Hambrook D, Broadbent H, Tchanturia K, Treasure J, et al. Emotional processing following recovery from anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2012) 20(6):502–9. doi: 10.1002/erv.2153

59. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther (2003) 41(5):509–28. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8

60. Polivy J, Herman CP. Causes of eating disorders. Annu Rev Psychol (2002) 53:187–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135103

61. Peñas-Lledó E, Vaz Leal FJ, Waller G. Excessive exercise in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: relation to eating characteristics and general psychopathology. Int J Eat Disord (2002) 31(4):370–5. doi: 10.1002/eat.10042

Keywords: alexithymia, anorexia nervosa, systematic review, PRISMA, treatment, outcome

Citation: Gramaglia C, Gambaro E and Zeppegno P (2020) Alexithymia and Treatment Outcome in Anorexia Nervosa: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Front. Psychiatry 10:991. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00991

Received: 12 October 2019; Accepted: 13 December 2019;

Published: 14 February 2020.

Edited by:

Domenico De Berardis, Azienda Usl Teramo, ItalyCopyright © 2020 Gramaglia, Gambaro and Zeppegno. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Patrizia Zeppegno, cGF0cml6aWEuemVwcGVnbm9AbWVkLnVuaXVwby5pdA==

Carla Gramaglia

Carla Gramaglia Eleonora Gambaro

Eleonora Gambaro Patrizia Zeppegno

Patrizia Zeppegno