- 1Department of Psychiatry, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

- 2Ph.D. Program in Translational Medicine, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan

- 3Department of Mathematics, Xiamen University Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia

- 4Department of Applied Mathematics, Tunghai University, Taichung, Taiwan

- 5Faculty of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan

- 6Institute of Molecular Biology, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan

Background: The intrinsic motivation behind the “need to complete” is more influential than external incentives. We introduced a novel progress-bar tool to motivate the completion of programs designed to treat stimulant and cannabis use disorders. We further examined the effectiveness of the progress bar's scoring approach in forecasting consistently negative urine tests.

Methods: This study's participants included 568 patients with stimulant, amphetamine-type, and cannabis use disorders who were undergoing 12-month mandatory treatment programs at Taichung Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan. Patients were given scores of 1, -1, or 0 depending on whether they received negative, positive, or missing urinalysis reports, respectively. The autonomic progress bar generated weekly score totals. At the group level, scorei donated scores from all patients for a given week (i denoted the week). Scorei was standardized to adjusted scorei. We then conducted Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) Model of time-series analyses for the adjusted scorei.

Results: A total of 312 patients maintained treatment progress over the 12-month program. The autonomic score calculator totaled the shared achievements of these patients. The coefficients of the lag variables for mean (p), lag variables for residual error term (q), and number of orders for ensuring stationary (d) were estimated at p = 3, d = 4, and q = 7 for the first half of the treatment program, and were estimated at p = 2, d = 2, and q = 3 for the second half. Both models were stationary and tested as fit for prediction (p < 0.05). Sharply raised adjusted scores were predicted during the high-demand treatment phase.

Discussion: This study's novel progress-bar tool effectively motivated treatment completion. It was also effective in forecasting continually negative urine tests. The tool's free open-source code makes it easy to implement among many substance-treatment services.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence advancements have enabled unprecedented reforms in the domain of medicine. These advancements have recently expanded to the addiction treatment field. In this context, both computer and mobile-based applications have helped eradicate the care gap while removing treatment barriers. Such tools also provide cognitive behavioral training, automated newsletter reminders, and treatment motivation (1–6). Many mobile apps have successfully been used to augment alcohol abuse treatment (4), while computers have become major intervention and meeting tools among therapists who need to monitor patient progress in cases of depression and marijuana use disorders (7). Further, several studies have reported that patients with stimulant use disorders require the ability to monitor their treatment progress online; such an environment offers enhanced motivation (8–11).

Progress bars are used as percentage-completion indicators (8). They are widely used in several software contexts, including program downloading, online gaming, and data transmission. In this regard, studies have found that the “need to complete” provides motivation (9, 10). From the psychoanalytic perspective, addicts cast powerlessness to therapists, who then produce a sense of powerlessness to form projective identities. As such, progress itself is seen as a reward (11, 12). We believe that progress indicators create intrinsic motivation through the “need to complete” and that that such urgency is more influential than external incentives.

If compulsory treatment is synonymous with the unwillingness to receive treatment, then it is unsurprising that psychotherapy resistance is profoundly manifested by many patients. Although difficult at times, mandatory treatment is thus becoming more common, especially because it increases treatment adherence. Mandatory treatment requires patients to follow prescribed treatment plans that sometimes require attendance schedules and scheduled urinalyses. We believe that 12-month treatment programs can achieve greater success if used in conjunction with effective computer software designed to facilitate psychological operations through the “need to complete.” This will stimulate intrinsic motivation, thus prompting patients to adhere more closely to prescribed treatment plans. This study was comprised of two parts. First, we implemented a novel progress-bar tool to motivate treatment completion among patients of a 12-month program. Second, we examined the effectiveness of the progress bar's scoring approach (see Measurements) in forecasting continually negative urine tests.

Methods

Samples and Materials

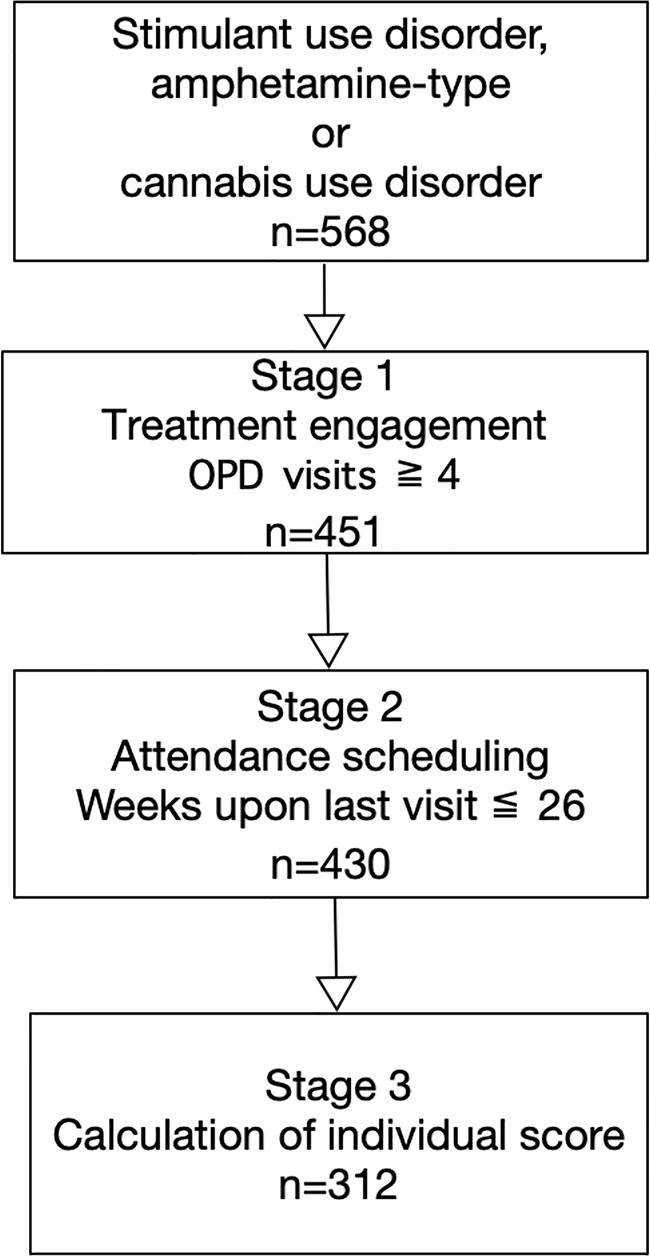

This was a retrospective follow-up study. Participants included 568 patients who were diagnosed with stimulant use, amphetamine-type, and/or cannabis use disorders between January 2013 and December 2018. All patients were required to complete 12-month treatment program at the Taichung Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan. All patients in this study were subjected to mandatory treatment. For inclusion in this study, patients were required to be at least 20 years of age and diagnosed with stimulant use, amphetamine-type, and/or cannabis use disorders based on diagnostic criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition, DSM-5. We excluded patients who had completed fewer than four outpatient department visits upon treatment engagement. This ensured an adequate observation period for the time-series data. We also excluded patients whose most recent visit was more than 26 weeks before the study period. This was because confounding factors may have increased since that time. We also considered that missed treatments periods exceeding 26 weeks may have been due to factors related to the judicial system (e.g., patients had been rearrested and were required to start treatment anew). Those patients throughout the 12-month treatment program were selected to calculate the individual score (Figure 1). This study was approved by the ethics review committee at Taichung Veterans General Hospital (IRB number: CF18105A).

Treatment Protocol

The substance treatment service at Taichung Veteran General Hospital was based on an adapted protocol-driven design. This ensured robust treatment boundaries from a psychological perspective. Patients were required to complete the treatment intervention according to an attendance schedule and were subjected to both urinalysis and group psychotherapy. Biweekly urinalyses were conducted to detect amphetamine, 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), and marijuana based on immunoassay during the first phase. For a given patient, stabilization was defined when a total of four negative urine samples had been observed. This was defined as the high-demand treatment phase.

Patients that completed the high-demand phase then transitioned to the low-demand phase. At that time, urinalysis was switched to a monthly basis. The average time at which patients began the low-demand phase was 6 months from treatment initiation. Here, each patient also attended a total of 10 biweekly group psychotherapy sessions. A positive urinalysis result required the respective patient to return to the biweekly urinalysis program.

Measurements

We developed a scoring system to summarize and visualize patient progress. Each patient received a score of 1 for each respective negative urinalysis result. However, each positive urinalysis resulted in a score of -1. Finally, patients received scores of 0 for each missed urinalysis. The program generated weekly score totals and plotted respective curves for each patient.

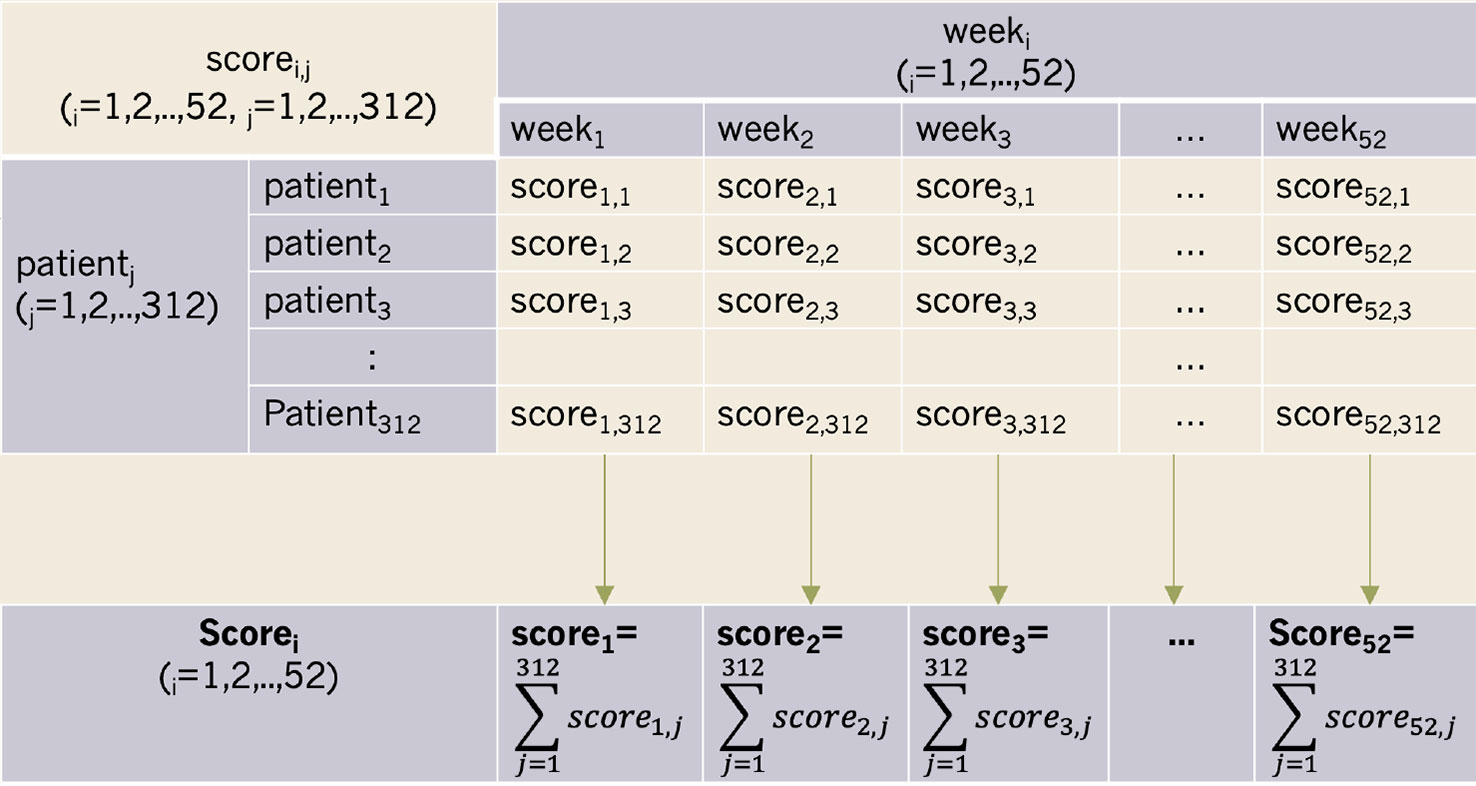

This scoring program consisted of a score and algorithm. At the group level, scorei donated the total score from all patients in a given week (i denoted the week) (Figure 2). However, the number of patients who took urinalyses varied each week. As such, scorei was standardized to the adjusted scorei. Adjusted scorei was then calculated as scorei/n, where n denoted the number of patients who took urinalyses during weeki. The open-source code for the progress bar is offered for free in the Supplementary Material section at the end of this document.

Statistical Analysis

The adjusted scorei for each week during the 12-month treatment period was used to generate time-series data. The milestone for reaching the low-demand treatment phase (see Treatment Protocol) was usually achieved approximately six months after beginning treatment. As such, two trend components were adapted at the 27th week as a cut-off point. We determined whether the time-series data deviated from the white noise assumption by implementing an Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) Model, while an augmented Dickey-Fuller single root test was conducted to test stationarity. We also estimated the coefficients of the lag variables for mean (p), lag variables for residual error term (q), and number of orders for ensuring stationary (d). Finally, we used the Box-Pierce test to determine whether the model was sufficiently robust for prediction. The R software (version 3.4.4) package was used for all statistical analyses. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

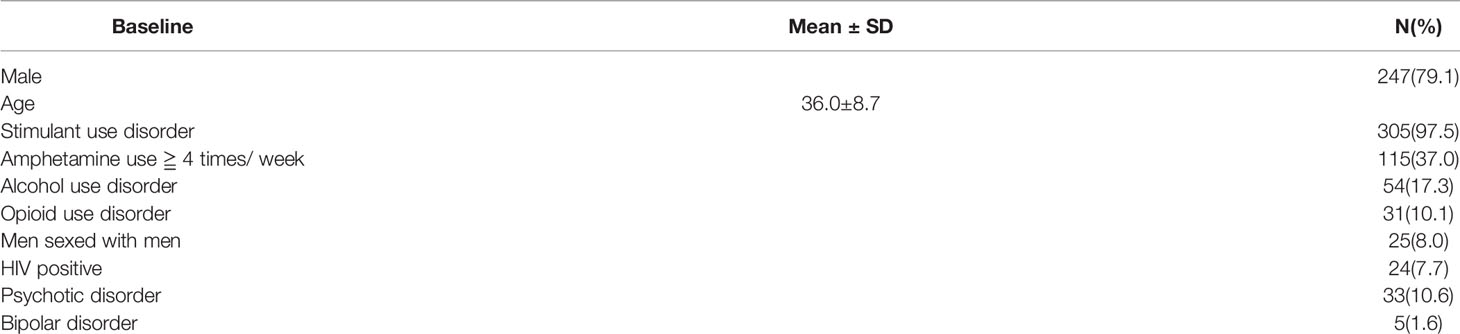

Of the 568 total patients, 117 failed treatment engagement as defined by attending less than four outpatient visits. Of the remaining 451, 430 maintained their expected attendance schedules. As such, 312 patients appeared consistently throughout the 12-month treatment program (Figure 1). Among these, 97.5% had stimulant use disorder, of which 37.0% used amphetamine-type stimulants more than 4 days per week. Of the abovementioned 312 patients, 79.1% were male (mean age of 36.0± 8.7 years), while 17.3% also had alcohol use disorder, and 10.1% had opioid use disorder. Overall, 8.0% were men sexed with men, and 7.8% were HIV-positive. Further, 10.6% had psychotic disorders, and 1.6% with bipolar disorder (Table 1).

Table 1 Descriptive data of 312 patients of stimulant use disorder or cannabis use disorder completing 12-month treatment.

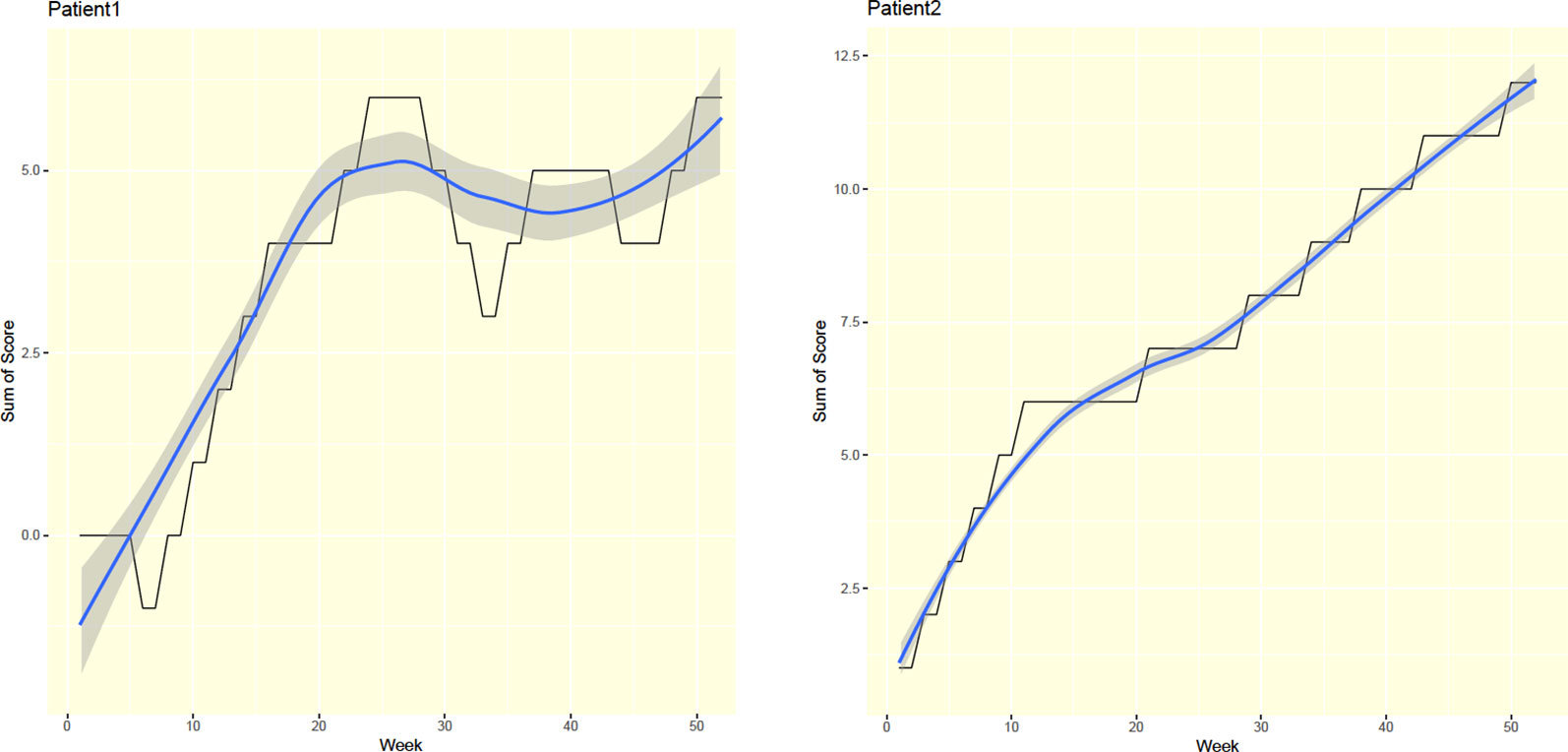

For each patient, this study's progress bar generated a total weekly score through a user-friendly graphical interface. That is, the application functioned as an autonomic progress indicator. For example, a steadily rising curve followed by a sharp fall may have reflected relapse, while a steadily increasing accumulated score likely reflected abstinence throughout the treatment course (Figure 3).

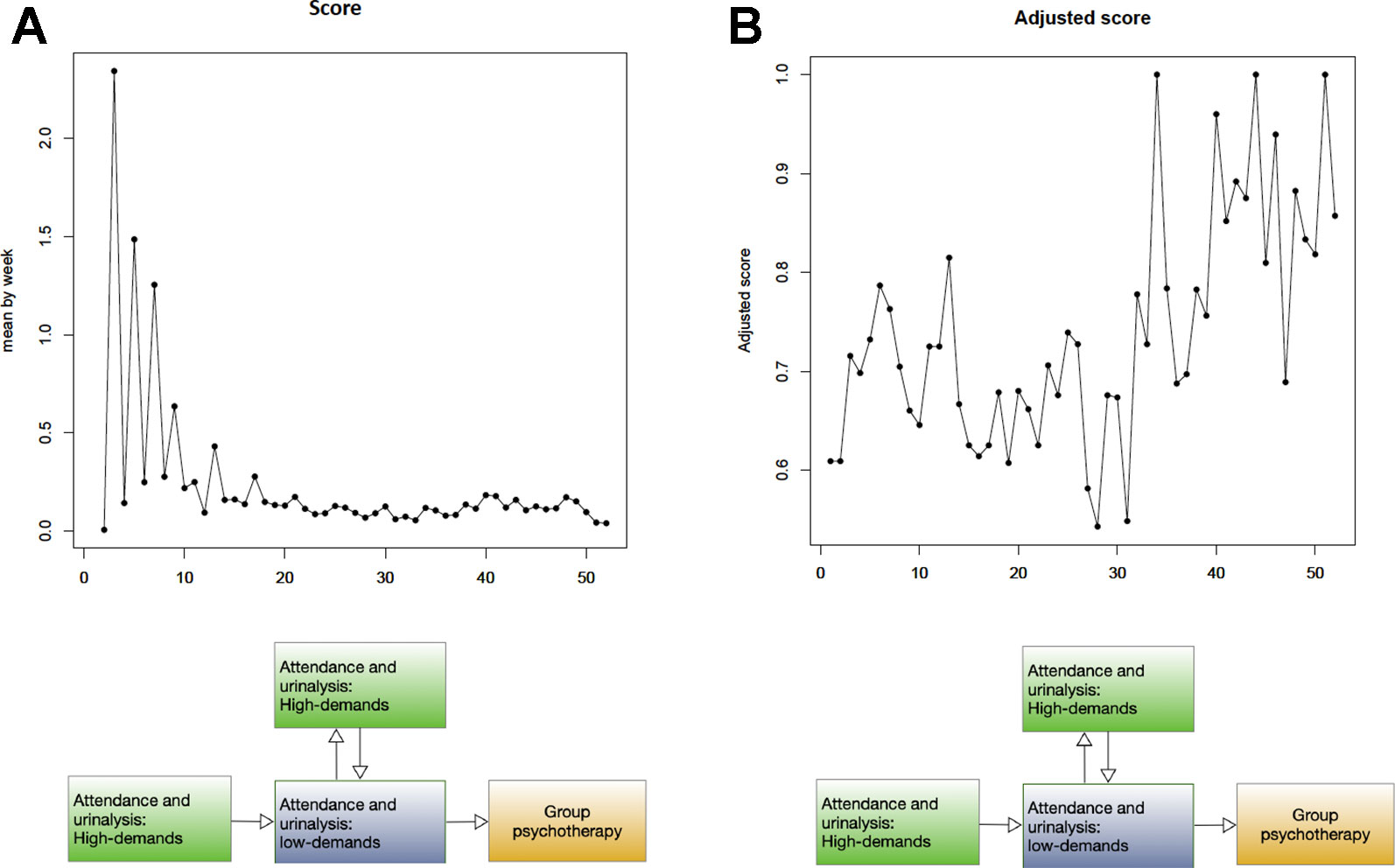

The progress bar facilitated patients in maintaining the vigilance needed to achieve their aims. In this context, we considered the addiction treatment service as an entity comprised of two halves. The first half was high-demand, while the second was low-demand. Patient progress during each half was measured according to scorei, which denoted the total scores from all patients in a given week (i denoted the week). Figure 4 shows overall weekly patient performance throughout the 12-month program. Here, the crude scores reveal larger fluctuations during the initial stages.

Figure 4 Time-series plot of overall 312 patients (A) X-axis: week, Y-axis: score (B) X-axis: week, Y-axis: adjusted score.

Total scores were dependent on the number of patients who completed urinalysis. Because the treatment protocol followed a biweekly schedule, the number of patients doing so was higher during weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8 than during weeks 1, 3, 5, and 7 (Figure 4). Given that the number of patients who completed urinalysis varied each week, scorei was standardized into adjusted scorei. After standardization, adjusted scores showed reduced interference due to varied attendance. On the other hand, we found increased fluctuations in the adjusted score during the second half of the treatment program.

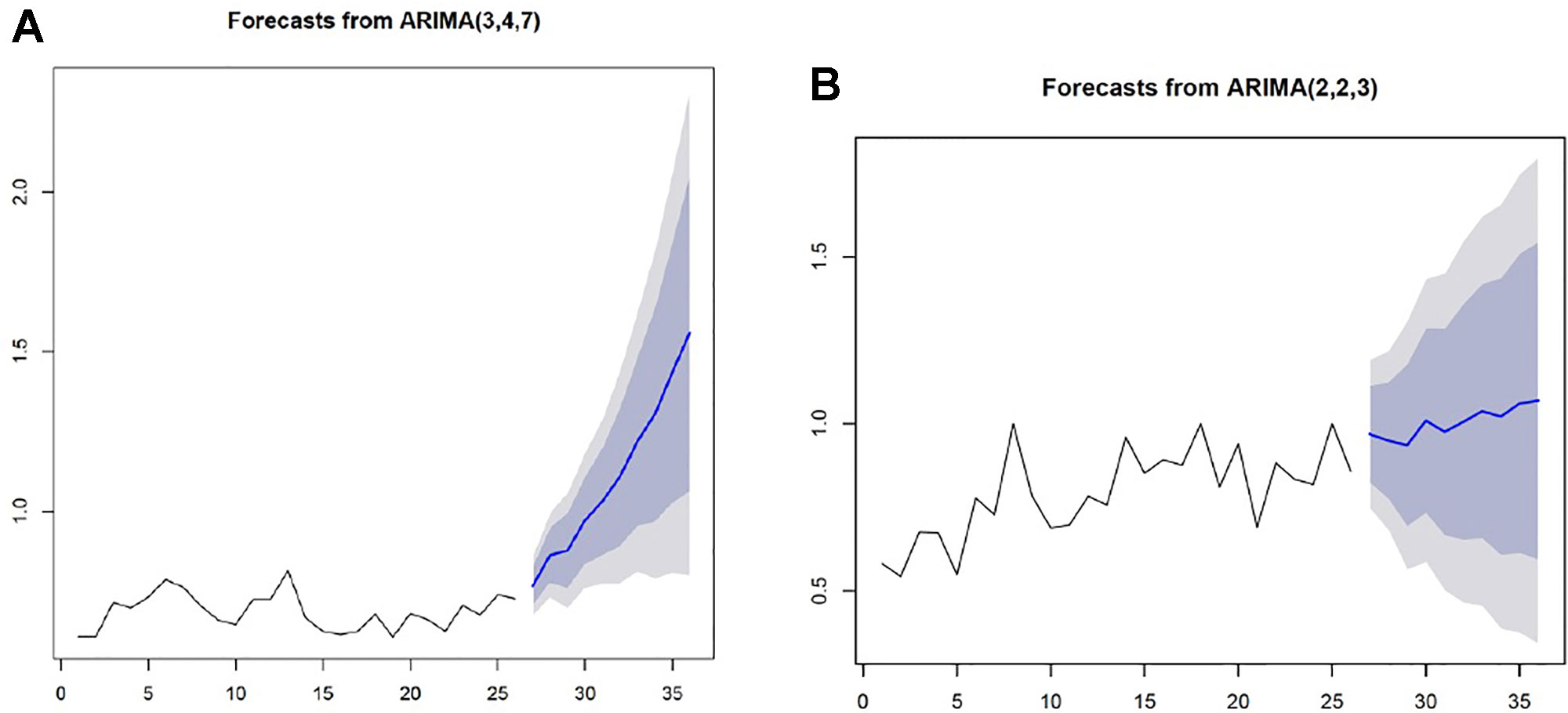

The first half of treatment revealed a trend spanning from week one to week 26, while the a second trend component was observed between week 27 and week 52. The coefficients of the lag variables for mean (p), lag variables for residual error term (q), and number of orders for ensuring stationary (d) were estimated at p = 3, d = 4, and q = 7 for the first half of the program, but were estimated at p = 2, d = 2, and q = 3 for the second half. Both models were stationary and tested as sufficiently fit for prediction (p < 0.05). Using the above two ARIMA models, we predicted an adjusted score that would reflect treatment outcomes during each program phase. Here, a sharply raised adjusted score was predicted during the high-demand phase, thus indicating an increasing number of negative urine tests. However, a slow and steady raised adjusted score was predicted for the low-demand phase (Figure 5).

Figure 5 The ARIMA models predicting treatment outcomes for each phase X-axis: week, Y-axis: adjusted score (A) A sharply raised adjusted score indicating an increased number of negative urine tests was predicted for the high-demand treatment phase. (B) A slow and steady raised adjusted score was predicted for the low- demand treatment phase.

Discussion

We introduced a novel autonomic progress-bar tool to summarize urinalysis results for patients who were attempting to complete a program to treat stimulant and/or cannabis use disorder. We also developed an autonomic score calculator that totaled shared patient achievements. Resulting scores were analyzed as time-series data, thus revealing a trend that reflected compatible treatment demands.

This visual progress bar is currently a preliminary tool. However, elements of the intuitive design should be retained. For example, steadily increasing accumulated scores reflected persistent abstinence throughout the treatment course. Additional animated indicators may generate a curiosity-driven and pleasant experience. This is important because such factors are associated with the novelty-seeking trait (13, 14). We therefore believe that our progress bar will promote treatment engagement among patients with stimulant and/or cannabis use disorder.

Drug users may experience distress over the perception of lagging in progress. It is thus crucial to provide a virtual method for these individuals to generate forward-looking attitudes while preventing relapse (9, 15). Our visual progress bar offers a rewarding effect rarely obtained in contexts outside treatment programs. It may also offer experiences of increased mental engagement related to information-valuing functions, particularly those in the dopaminergic valuation systems (16, 18). From the perspective of neural encoding, information prediction during non-instrumental information seeking is not prone to error (16). This produces greater feelings of self-competence and promotes treatment adherence (19–20).

This study examined the effectiveness of a scoring approach through a visual progress bar in forecasting continually negative urine tests. We also examined performance at different treatment stages associated with changing demands and considered how the scoring system could be improved. As such, we plotted two ARIMA models to conduct time-series analyses for both the high and low treatment demand phases. We found obvious changes in scores based on treatment demands. For example, rapidly increasing scores reflected an increasing number of negative urine tests, which was forecast for the high-demand phase. On the other hand, a series of small, incremental score increases were predicted for the low-demand phase. Previous research has also shown that high-demand treatment is significantly correlated with continually negative urine testing (21). Here, the changes in scoring trends between the different treatment levels observed in this study supported existing evidence.

We found increased fluctuations in the adjusted score during the low-demand treatment phase. This is likely because the number of patients completing urine tests under the stringent biweekly schedule dwindled over time. For example, a given patient would complete urine testing during even-numbered weeks if following the attendance schedule exactly. However, missed appointments would disrupt the schedule, thus increasing the number of tests taken during odd weeks. As such, the numbers of patients attending during even and odd weeks were distributed more evenly over time. This was reflected by the fluctuating scores seen during the second half of the treatment program.

This study should be interpreted within the context of its limitations. First, we did not examine the validity of the progress bar through a clinical trial. This study did not compare a non- progress-bar-using group and a progress-bar-using group. Instead, we incorporated a quasi-experiment. As a result, the validity and reliability of this novel tool could not be determined. Second, patients were required to attend biweekly group psychotherapy sessions that began during their six months of treatment. As such, an instrumental effect due to this therapeutic influence may have been a confounding factor. Third, all patients in this study were subjected to mandatory treatment. This was because treatment approach for substance use offenders transited from detention-base to deferred prosecution, for recent two decades globally. Previous study proved the judicial-plus-therapeutic effect rather than judicial-alone effect (21).

In conclusion, we developed a novel progress-bar tool for use in motivating the completion of a stimulant and/or cannabis use treatment program. We also developed an autonomic score calculator that totaled shared patient achievements. Finally, a time-series analysis was conducted to examine the effectiveness of both the scoring approach and progress bar in forecasting continually negative urine tests. The open-source code for this free application is offered in the Supplementary Material section below and can easily be implemented for use in other substance-treatment services.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researchers.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Review Committee of Taichung Veterans General Hospital. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

I-CC contributed to statistical analysis and drafting of the manuscript. GT contributed to the conception and interpretation of data. C-JC, T-HL and H-JL contributed to revising critically of the intellectual content.

Funding

This work was supported by the Taichung General Veterans Hospital, Taiwan (Grant number: TCVGH-NHRI10602).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was based in part on data from Taichung Veterans General Hospital Research Database and Managed by Clinical Informatics Research & Development Center of Taichung Veterans General Hospital (Registered number F18080). The interpretation and conclusion contained herein do not represent those of Taichung Veterans General Hospital. We thank Prof. Huang-Nan Huang and Miss Ting-Cih for data interpretation. We thank two case management nurses, Mrs. Su-Hua Lee and Mrs. Yu-Lin Yang for executing the treatment protocol. We thank Dr. Chia-Chun Hong for setting-up treatment protocol. Also, we thank to Miss Fang-Yi Lin for retrieving the raw data. We thank Miss Wan-Jan Tsai for taking charge of group psychotherapy and retrieving approval by the ethics review committee. We thank Mrs. Hsiu-Ying Chang in assisting of statistical analysis.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00944/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Harada T, Tsutomi H, Mori R, Wilson DB. Cognitive-behavioural treatment for amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS)-use disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev (2018) 12:Cd011315. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011315.pub2

2. Tofighi B, Abrantes A, Stein MD. The role of technology-based interventions for substance use disorders in primary care: a review of the literature. Med Clinics North America (2018) 102(4):715–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.02.011

3. Brendryen H, Lund IO, Johansen AB, Riksheim M, Nesvåg S, Duckert F. Balance—a pragmatic randomized controlled trial of an online intensive self-help alcohol intervention. Addiction (2014) 109(2):218–26. doi: 10.1111/add.12383

4. Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih M-Y, Atwood AK, Johnson RA, Boyle MG, et al. A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry (2014) 71(5):566–72. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4642

5. Wallace P, Bendtsen P. Internet applications for screening and brief interventions for alcohol in primary care settings – implementation and sustainability. Front In Psychiatry (2014) 5:151.

6. Schaub MP, Wenger A, Berg O, Beck T, Stark L, Buehler E, et al. A web-based self-help intervention with and without chat counseling to reduce cannabis use in problematic cannabis users: three-arm randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res (2015) 17(10):e232.

7. Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Carr VJ. Computer-based psychological treatment for comorbid depression and problematic alcohol and/or cannabis use: a randomized controlled trial of clinical efficacy. Addiction (2009) 104(3):378–88.

9. Wulf G, Lewthwaite R. Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: the optimal theory of motor learning. Psych. Bull Rev (2016) 23(5):1382–414.

10. Jahfari S, Theeuwes J. Sensitivity to value-driven attention is predicted by how we learn from value. Psych. Bull Rev (2017) 24(2):408–15. doi: 10.3758/s13423-016-1106-6

11. Choi J, Medalia A. Intrinsic motivation and learning in a schizophrenia spectrum sample. Schizophr Res (2010) 118(1-3):12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.08.001

12. Takano A, Miyamoto Y, Kawakami N, Matsumoto T. Web-based cognitive behavioral relapse prevention program with tailored feedback for people with methamphetamine and other drug use problems: development and usability study. JMIR Ment Health (2016) 3(1):e1.

13. Li Y, Huo T, Zhuang K, Song L, Wang X, Ren Z, et al. Functional connectivity mediates the relationship between self-efficacy and curiosity. Neurosci Lett (2019) 711:134442.

14. Lloyd DR, Kausch MA, Gancarz AM, Beyley LJ, Richards JB. Effects of novelty and methamphetamine on conditioned and sensory reinforcement. Behav Brain Res (2012) 234(2):312–22.

15. Just AL, Meng C, Smith DG, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW, Ersche KD. Effects of familial risk and stimulant drug use on the anticipation of monetary reward: an fMRI study. Trans Psychiatry (2019) 9(1):65.

16. Brydevall M, Bennett D, Murawski C, Bode S. The neural encoding of information prediction errors during non-instrumental information seeking. Sci Rep (2018) 8(1):6134.

17. Luijten M, Schellekens AF, Kuhn S, Machielse MW, Sescousse G. Disruption of reward processing in addiction: an image-based meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. JAMA Psychiatry (2017) 74(4):387–98.

18. Spreckelmeyer KN, Krach S, Kohls G, Rademacher L, Irmak A, Konrad K, et al. Anticipation of monetary and social reward differently activates mesolimbic brain structures in men and women. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci (2009) 4(2):158–65. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn051

19. Marsden J, Stillwell G, James K, Shearer J, Byford S, Hellier J, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of an adjunctive personalised psychosocial intervention in treatment-resistant maintenance opioid agonist therapy: a pragmatic, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry (2019) 6(5):391–2.

20. Carroll KM, Kiluk BD, Nich C, DeVito EE, Decker S, LaPaglia D, et al. Toward empirical identification of a clinically meaningful indicator of treatment outcome: features of candidate indicators and evaluation of sensitivity to treatment effects and relationship to one year follow up cocaine use outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend (2014) 137:3–19.

Keywords: mandatory treatment, progress bar, motivation, stimulant use disorder, time series analysis

Citation: Chen I-C, Teng G, Chen C-J, Lan T-H and Liu H-J (2020) The Autonomic Progress Bar Motivates Treatment Completion for Patients of Stimulant Use Disorder and Cannabis Use Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 10:944. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00944

Received: 24 September 2019; Accepted: 29 November 2019;

Published: 13 January 2020.

Edited by:

Kai Zhang, Chiba University, JapanReviewed by:

Mauro Ceccanti, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyHang Su, Shanghai Mental Health Center (SMHC), China

Copyright © 2020 Chen, Teng, Chen, Lan and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: I-Chun Chen, aS1jaHVuLmNoZW5AdmdodGMuZ292LnR3; Hung-Jen Liu, aGpsaXU1MjU3QG5jaHUuZWR1LnR3

I-Chun Chen

I-Chun Chen Gloria Teng3

Gloria Teng3