- 1Centre for Mental Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2Centre for Psychiatric Nursing, School of Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 4Centre for Adolescent Health, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Heidelberg, VIC, Australia

- 5Mater Research Institute-UQ, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 6Griffith Criminology Institute, Griffith University, Mt Gravatt, QLD, Australia

- 7School of Allied Health, Human Services and Sport, La Trobe University, Bundoora, VIC, Australia

- 8Mind Australia Limited, Heidelberg, VIC, Australia

Introduction: Mental health professionals working in acute inpatient mental health wards are involved in a complex interplay between an espoused commitment by government and organizational policy to be recovery-oriented and a persistent culture of risk management and tolerance of restrictive practices. This tension is overlain on their own professional drive to deliver person-centered care and the challenging environment of inpatient wards. Safewards is designed to reduce conflict and containment through the implementation of 10 interventions that serve to improve the relationship between staff and consumers. The aim of the current study was to understand the impact of Safewards from the perspectives of the staff.

Methods: One hundred and three staff from 14 inpatient mental health wards completed a survey 12 months after the implementation of Safewards. Staff represented four service settings: adolescent, adult, and aged acute and secure extended care units.

Results: Quantitative results from the survey indicate that staff believed there to be a reduction in physical and verbal aggression since the introduction of Safewards. Staff were more positive about being part of the ward and felt safer and more connected with consumers. Qualitative data highlight four key themes regarding the model and interventions: structured and relevant; conflict prevention and reducing restrictive practices; ward culture change; and promotes recovery principles.

Discussion: This study found that from the perspective of staff, Safewards contributes to a reduction in conflict events and is an acceptable practice change intervention. Staff perspectives concur with those of consumers regarding an equalizing of staff consumer relationships and the promotion of more recovery-oriented care in acute inpatient mental health services.

Introduction

In Australia and internationally, there has been a movement by consumers and carers, supported in national policy, toward the provision of recovery-oriented care (1, 2). The core of recovery orientation is that consumers, with or without symptoms of mental illness, are central in setting their own priorities for care and receive the necessary support to live a meaningful life of their choosing (3–5).

The current National Mental Health Policy emphasizes reducing use of restrictive practices in inpatient mental health services (6). Research has found that there is no evidence that seclusion is therapeutic (7). One qualitative study found diverse views among staff, some believing seclusion was part of treatment and others believing it was a punishment (8). Emerging evidence, particularly in the qualitative literature, highlights findings from consumers and staff that the use of restrictive practices, including seclusion, can be experienced as retraumatizing for consumers and for those who witness these practices (9–11). The use of restrictive practices can lead to consumers feeling unsafe and may interfere with ongoing personal recovery and engagement with services (11, 12).

Inpatient mental health services are complex environments for people experiencing the most acute symptoms of mental illness. People are often involuntarily admitted for short periods of time, and it has been asserted by some that the focus is on stabilization of a pharmaceutical regime. It has been suggested that staff in inpatient units tend to rely on medication as the primary treatment under a medical model of care (13–15). Organizational safety and risk management provide fundamental guidance to practice. Slemon et al. (16) have argued that the risk management culture that drives care in inpatient mental health settings results in a perpetuation of stigma that people with a mental illness are aggressive. Therefore, staff are responsible for maintaining the safety of everyone in the ward, legitimizing the use of restrictive practices to maintain control and safety (16, 17). Support for this approach is potentially located in findings that mental health professionals are at higher risk of being exposed to physical aggression than many other health care professionals (18). Mental health nurses are often fearful about being injured at work and may as a group feel that the use of restrictive practices (such as seclusion) is necessary (8). Staff also report cognitive dissonance (19) with feelings of guilt associated with forcing consumers to take medication and using restrictive practices but a sense of being trapped in these ways of working (8). Despite this tension, nurses are motivated to engage more therapeutically with patients, yet aspects of the institutional flow, such as short stays and excessive paperwork, discourage engagement. Even so, research has found that nurses who spend more time directly caring for patients experience greater job satisfaction (20).

It has been argued that the challenges inherent in caring for consumers in services that prioritize medication adherence and risk management have resulted in nurses lacking time and autonomy to engage in therapeutically meaningful interactions with consumers, causing frustration for both consumers and nurses (21, 22). The development of a therapeutic relationship is viewed by many as the single most important factor in a positive inpatient admission (12, 23, 24). Despite this, research in one Australian state using a work sampling methodology has found that only 32% of nurse time was spent in direct care (25). A slightly higher proportion of time (42.7%) in direct care was found by Whittington and McLaughlin (26) in an observational UK study; however, the specific measure regarding time spent in potentially therapeutic interactions was observed to be 6.75%. Goulter et al. (25) went on to conclude that the lack of time spent in direct care falls short of the expectations of consumers, and emerging evidence highlights that positive engagement is related to higher levels of consumer satisfaction (27). Furthermore, a review of literature related to the measurement of therapeutic relationships indicates that better quality therapeutic relationships may be achieved by nurses having increased time to spend with consumers, but that research regarding this is lacking (28). To improve this situation, Goulter et al. (25) suggest the need for “a comprehensive model of practice that draws on the best available evidence of what activities constitute best nursing practice in mental health settings” (p. 455). The Safewards model and interventions may provide one avenue of addressing the need expressed by Goulter et al. (25).

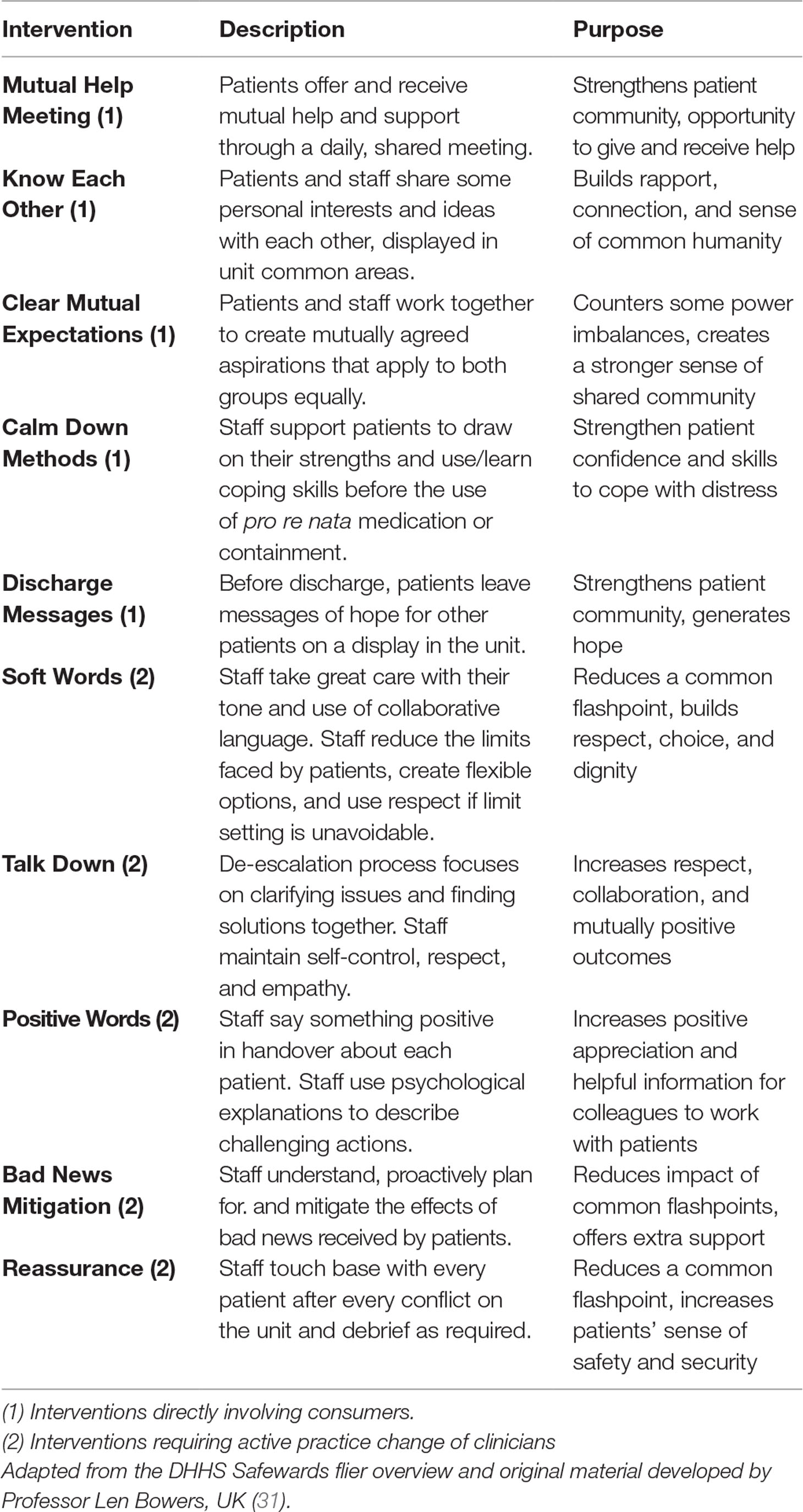

Safewards was developed after a series of comprehensive literature reviews and empirical research (29). Safewards offers a multifaceted approach to reducing conflict and the use of containing or restrictive practices by helping to shift the focus of staff back to direct care and building therapeutic relationships (30). Safewards is a theoretical model with 10 associated interventions designed to improve the safety of everyone in inpatient wards by reducing conflict (physical, verbal aggression, absconding) and containment (forced medication, seclusion, and restraint) events. For a full description of the model, see Bowers (30). Informed by extensive literature reviews and empirical research, the Safewards model proposes that six originating domains (the patient community, patient characteristics, regulatory framework, staff team, physical environment, and outside hospital) potentially contribute to flashpoints (e.g., a situation signaling and preceding a conflict event, such as physical aggression), which may then lead to conflict and containment (29). Staff have the potential to moderate each of these components of the model through their interactions with consumers. The interventions are described in Table 1.

In a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial of Safewards in the United Kingdom, Bowers et al. (32) observed a significant decrease in conflict and containment events in the Safewards condition compared with the control condition where a staff physical health improvement package was offered. However, variable success regarding implementation of Safewards has been reported in recent papers. Problems with implementation have included low adherence (fidelity) and lack of staff acceptance of the model (33, 34). This contrasts with high fidelity to the model in some settings, resulting in reduction in conflict events (35) and reduction in the use of forced sedation (36). Hence, high fidelity to the model is important to its outcomes. To date, the perceptions of staff from wards that have successfully implemented Safewards and therefore contributed to fidelity to the model have not been reported.

Based on the promising randomized controlled trial results from the United Kingdom, in 2014, the Victorian Department of Health in Australia funded seven self-selected health services to implement Safewards across 18 wards in urban and regional Victoria. Our team was commissioned to undertake an independent evaluation across the seven services. We used a pragmatic real-world evaluation design to evaluate training outcomes, impact of Safewards from consumer and staff perspectives, and short-term and long-term outcomes related to implementation fidelity and seclusion rates. The results from adult and youth acute wards suggest a significant reduction in seclusion rates, from 14.1 seclusions per 1,000 occupied bed days pre to 10.1 seclusions per 1,000 occupied bed days at 12 months’ follow-up, representing a 36% reduction (37). At 12-month follow-up, on average, 9 of the 10 Safewards interventions were being implemented (37). Consumer feedback from Victoria highlights that consumers believed that there was a reduction in physical and verbal aggression after implementation of Safewards. Overall, consumers felt safer and reported increased connection with staff and each other, leading to an experience of care that was more in line with a recovery orientation (38). In this paper, we aim to report on staff perspectives that formed part of the overall evaluation findings and compare and contrast with previously reported findings regarding consumer perspectives (38).

Method

Design

A cross-sectional postintervention survey design was used to study staff perspectives. Staff were surveyed between December 2015 and April 2016, 9–12 months after Safewards was first implemented, at which time, on average, 9 of the 10 Safewards interventions were implemented.

Setting

This study is based on inpatient mental health wards in both metropolitan and regional Victoria, Australia. It reports data from six of the seven health services that opted to implement Safewards. The inpatient services were adult, adolescent/youth, and aged acute wards and secure extended care units.

Participants

Current staff on 14 wards from six of the seven health services that implemented Safewards were invited to take part in the staff survey. One service decided not to take part in the survey of staff.

Measures

The purpose-designed survey included demographic characteristics and both quantitative and qualitative questions regarding the acceptability, applicability, and impact of the Safewards model and 10 interventions. The survey was developed by the research team in reference to the overarching research questions with further input from the commissioning agency. All members of the research team were trained mental health clinicians who had experience working in inpatient settings alongside their research expertise. The face validity of the items was agreed to by all parties.

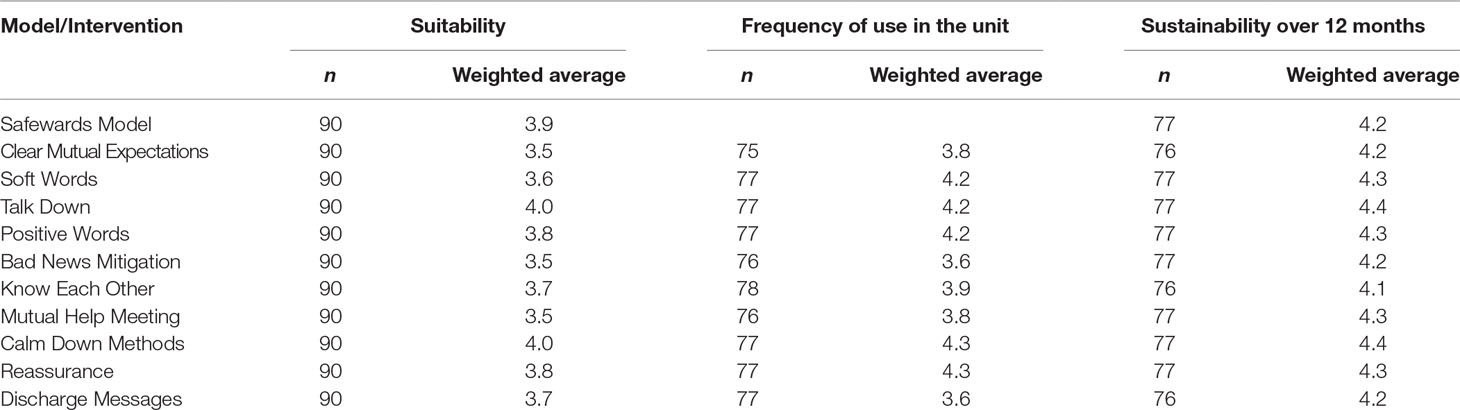

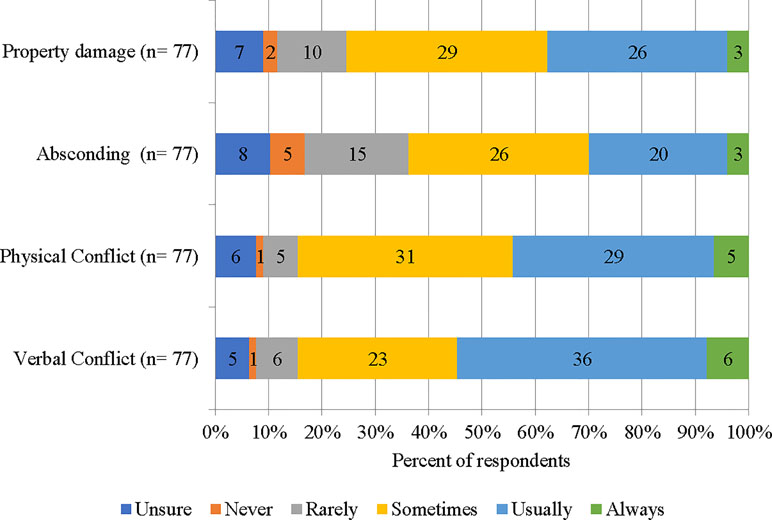

Five quantitative questions covered: 1) how suitable staff thought Safewards was using a Likert scale, where 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent; 2) how frequently interventions were used; 3) would they be sustained over the next 12 months using a Likert scale, where 1 = highly unlikely, 2 = not likely, 3 = possible, 4 = probable, 5 = highly probable; 4) the impact of Safewards on four conflict events (property damage, absconding, physical conflict, and verbal conflict) that were agreed upon by the researchers and the Government team piloting Safewards as the most relevant in the Victorian context at the time; and 5) the impact of Safewards on the atmosphere of the ward. Participants responded to these questions on a 5-point Likert scale. The Likert scale anchor points for questions two, four, and five were 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = usually, 5 = always.

Procedures

The plain language statement and consent form made clear that participation was voluntary, and that staff could withdraw at any time. The survey was hosted on SurveyMonkey; staff were sent a link from the local Safewards lead via e-mail. Ethics approval was obtained via the Victorian Human Research Ethics Multi-site process (ID 15225L) for each of the involved services.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed descriptively using SPSS version 22. Weighted averages for the Likert scales were calculated using the number of people who selected a given response and the weighting of that response. Staff who rated the Safewards model or one of the interventions as “poor” or “excellent” were given the opportunity to provide a detailed comment. Qualitative data were analyzed by two of the researchers (JF and BH) using a thematic approach guided by the approach outlined by Braun and Clarke (39). We elected to use an inductive process to uncover emerging themes. The steps we took were 1) to become familiar with the data, qualitative comments were read and counted to gain an understanding of the spread of feedback from participants; 2) initial codes were generated about the data, particularly assessing the spread of positive, negative, and neutral comments to provide a sense of the overall perspective of participants about Safewards; 3) comments of 3 or more words (i.e., those with some meaning to be elucidated) were categorized according to emerging themes; 4) we reviewed and where necessary reorganized the data according to the themes; 5) we discussed the names and definitions of each theme to ensure that they captured the essence of the data; and 6) the analysis was written up and examined to ensure accurate representation of the data according to the themes.

Results

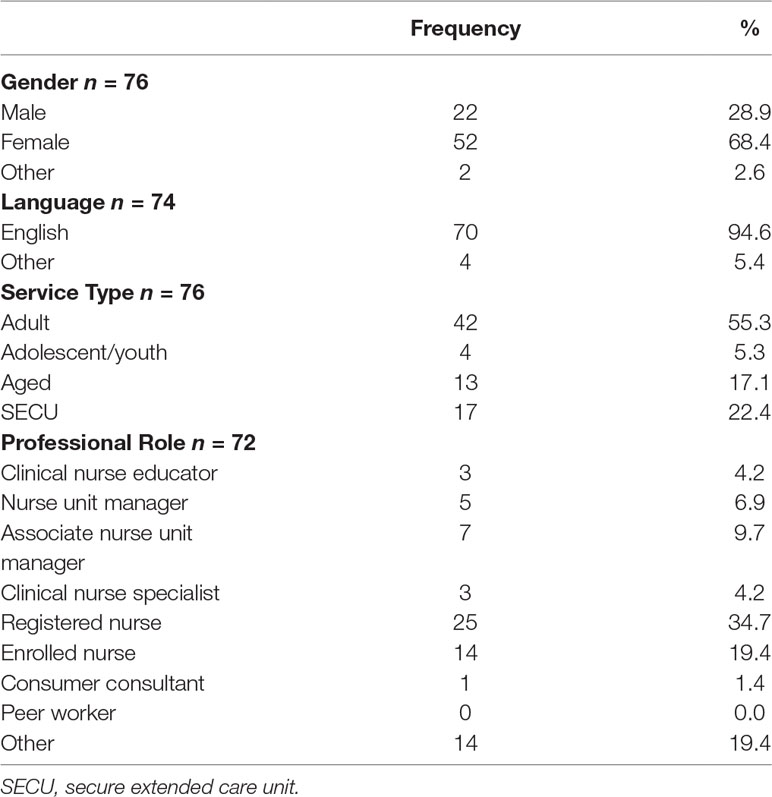

One hundred three staff responded to the survey representing each of the 14 wards. The majority were English-speaking women with a mean age of 43 years (range, 21–61, SD 10.28). Each service type was represented, with secure extended care unit (SECU) being slightly overrepresented and adolescent/youth wards being slightly underrepresented. Fifty-five percent of staff were registered or enrolled nurses, and almost 20% reported being from another professional group, including occupational therapists, social workers, and medical staff (Table 2).

Table 3 displays the weighted average response according to the suitability of Safewards, the frequency of use in the ward, and the likelihood of the intervention remaining in place over the next 12 months. On average, staff rated the suitability of the Safewards model and interventions as good to very good. Variation among staff may indicate differences in service settings; however, there was not enough data in each group to test this statistically. Staff reported that each of the Safewards interventions was used in their ward on average sometimes to usually. Staff held a positive view that it was probable to highly probable that Safewards would still be in place in their ward in 12 months’ time.

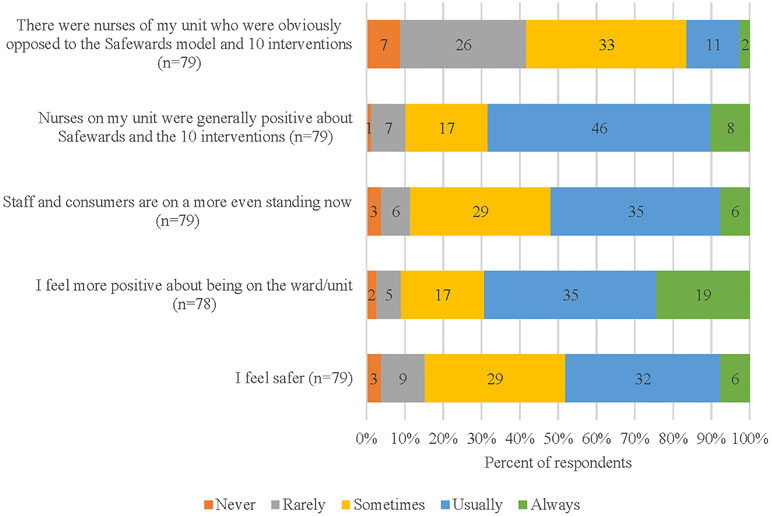

Figure 1 displays four conflict events and the corresponding rating of staff regarding the impact of Safewards on these. Staff were conservative about the impact of Safewards on absconding and property damage, reporting that Safewards usually or always positively impacted (30% and 35%, respectively). A small group of staff reported that they were unsure or it never had an impact on absconding and property damage. In contrast, staff were clearer that Safewards impacted on physical and verbal conflict, with 45% and 55%, respectively, reporting that Safewards usually or always had a favorable impact.

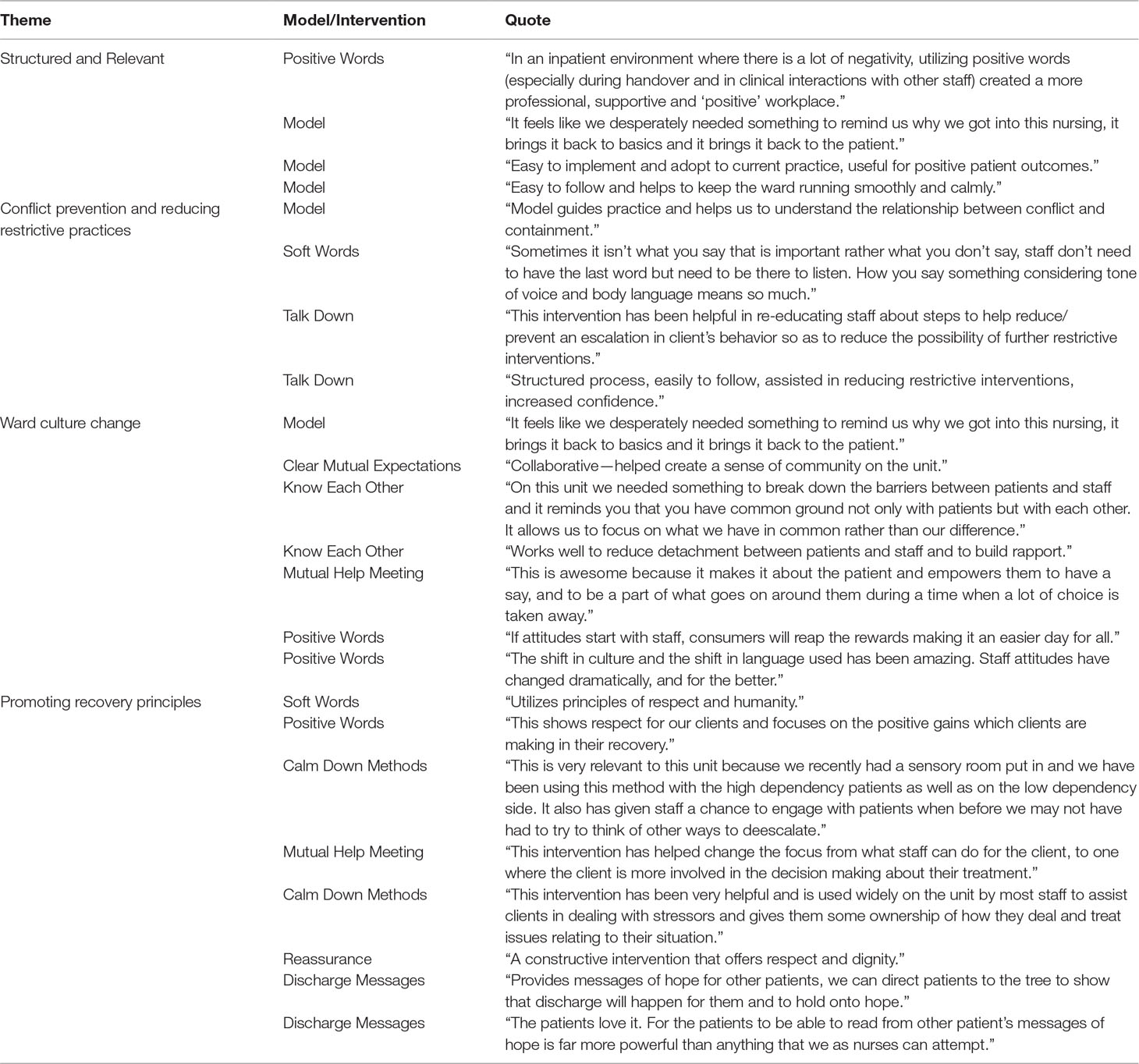

Figure 2 displays five statements about staff’s experiences of being “on the ward” while Safewards was being implemented. Most staff reported that the nurses were positive about the introduction of Safewards, with a minority reporting that some nurses in their ward were actively opposed to Safewards. Staff felt safer in the ward (50% usually or always) and more positive about being in the ward. Most staff believed that staff and consumers were “on a more even standing” (90% sometimes–always).

Qualitative Responses

The following provides a thematic analysis of the responses provided by staff. Staff rated interventions as “poor” between 1% and 5% of the time, and six staff provided 13 written comments about their responses. Two themes describe the “poor” rating, incompatible and procedural concerns. The first theme highlights a staff view that the intervention is incompatible with nursing roles and responsibilities. For example, a staff member has a sense that their responsibility is greater than the patient’s, and therefore, the interventions are inappropriate.

The second theme relates to procedural concerns, with some respondents reporting that the intervention was poor because there was no ownership taken for the intervention among the team. The critical comments from staff came from a small subset (n = 6) of participants, who were also likely to rate multiple interventions as “poor” or “fair.”

Four key themes summarize the detailed responses of staff regarding their rating of the model or any of the interventions as “excellent.” The themes are structured and relevant, conflict prevention and reducing restrictive interventions, ward culture change, and promoting recovery principles. Illustrative quotes are presented in Table 4. These four themes incorporate the views of 39 staff with 176 comments related to both the model and all 10 interventions.

In relation to the theme structured and relevant, staff put forward the idea that the model and interventions reminded them of their professional training and refreshed their thinking about providing more holistic care. Specifically, staff reported prioritizing the staff–consumer relationship with Safewards in ways that other ward system models may not. Staff affirmed that the model was clear and simple to follow.

The theme conflict prevention and reducing restrictive practices highlights staff’s feedback regarding a renewed understanding of the relationship between conflict and containment, resulting in increased confidence to listen well and talk respectfully to consumers in a way that minimizes frustration and, by extension, interrupts the cycle of conflict and containment.

The staff who highlighted a positive ward culture change described less social distance and enhanced mutual regard, arising from sharing responsibility and increased collaboration between staff and patients. A number of mechanisms related to specific interventions facilitated this culture change, for example, Know Each Other helped staff and consumers to find commonality with each other, Clear Mutual Expectations increased the sense of community in the ward, Positive Words led to attitude changes in staff, which in turn improved their interactions with consumers.

The theme promotes recovery principles captures the feedback from staff that a variety of interventions enhances consumer involvement in their care and treatment, hope and peer support, choice, dignity, and respect from staff toward consumers.

Discussion

This paper reports on staff experiences and views of the suitability and impact of the Safewards theoretical model and its 10 interventions. Overall, staff reported that Safewards impacted on physical and verbal conflict and supported a positive change in the ward environment and relationships, helping staff to feel safer. The following sections discuss the current findings in relation to whether Safewards reduced conflict events or flashpoints. These findings can be contrasted with those obtained from consumers (38).

Reducing Restrictive Practices

Generally, staff indicated that Safewards had impacted on flashpoints in a positive way. Like consumers, the staff were most modest in their views about absconding and property damage. Staff were most confident in the impact of Safewards on verbal and physical conflict, although the staff group had a much stronger view of the impact of Safewards on physical and verbal conflict (45% and 55%, respectively, compared with 25% of consumers usually or always had an impact) (38).

The theme conflict prevention and reducing restrictive practices highlights the relational aspects of Safewards. The findings of this study indicate that, in challenging situations, staff feel more empowered and permitted to act with a renewed understanding of the impact of their responses on consumers. This may suggest a positive shift away from the use of restrictive practices to maintain compliance, thus giving consumers the potential to trust the staff more, consequently building relationships (12).

Shifting Culture and Improving Recovery-Oriented Practice

Staff reported that Safewards had a positive impact on their experience of being in the ward. Both staff and consumers described a more equal relationship as a result. These findings indicate some differences in perceived changes. Consumers were most positive about feeling safer in the wards (95% sometimes or usually); staff were slightly less so (85% sometimes to usually). In contrast, staff were more optimistic than consumers about the shift to a more equal staff–consumer relationship (90% compared to 70% sometimes to always) (38).

The qualitative findings highlighted themes unique to the staff perspective, such as structured and relevant. Staff were positive about Safewards legitimizing and operationalizing the centrality of person-centered care. This finding supports previous research that nurses experience increased satisfaction when they are able to spend more time in direct interactions with their patients (20). These opportunities need to be built into ward routines. Safewards was viewed by most as feasible in the current practice environment of competing demands (25). Positive words specifically helped create a professional, supportive, and positive workplace. This finding may highlight one of the key drivers in our previous findings regarding a reduction in seclusion rates associated with Safewards. Previous research has found that negative staff morale increases the likelihood of conflict and containment; these were decreased when staff engaged in positive practice, such as being compassionate and valuing consumers (40).

Staff in this study highlighted that Safewards is clear and straightforward to understand and implement. This finding is at odds with other studies that have found staff did not readily accept or adhere to the interventions and, consequently, fidelity was poor (33, 34). In contrast, in Victoria, before implementation, staff in all wards participated in Safewards training, with evaluation surveys revealing significant increases in staff knowledge, confidence, and motivation to implement Safewards (Fletcher et al., submitted). This provides a possible explanation about staff understanding of the Safewards model and interventions and may explain the high fidelity scores achieved. Furthermore, staff in the present study reported that it was highly probable Safewards would be sustained in their health services over the next 12-months (2 years after Safewards was first implemented). Together, these findings provide support for the notion that Safewards has the potential to be sustained long-term and highlights some factors that may be key to achieving this sustainability (37).

Ward culture change relates to changes in staff attitudes toward consumers and building rapport, which stems from staff realizing and accepting that they are in a position to influence most aspects of the ward procedures and interactions. This corresponds to conclusions drawn in previous research that views about restrictive practices are divergent among staff. When staff connect with the uniqueness of a consumer, they are less likely to believe in the use of restrictive practices. In contrast, when distance remains between staff and consumers, staff view consumers as having “common needs and common restrictions” (8).

Feedback from staff in the current study aligns with consumer feedback regarding Safewards promoting aspects of recovery. In particular, consumers consulted in our work have expressed a view that Safewards promotes respect for consumers, enhancing consumer participation in their care, and the importance of dignity and hope (38).

Perceived Shortcomings

A small minority of staff rated the model or interventions as poor. Reasons provided included describing a lack of staff ownership resulting in the intervention not being implemented well. This theme aligns with the small group of consumers who rated some of the interventions poorly, with one reason being that staff did not use the interventions in some wards (38). Furthermore, staff rated some of the interventions as poor either because they believed that staff had more responsibility than consumers and therefore an intervention that attempted to level this out was viewed as problematic or because consumers were too unwell to use the intervention appropriately thus it was incompatible. These were not concerns experienced by the consumers (38).

Limitations

The current study may have included a biased sample as staff self-selected, so those with more positive views may have been more inclined to participate. Although all services were represented, the distribution was not representative of the number of wards involved in each service.

Conclusion

The present study suggests that the feasible and simple implementation of Safewards has had a positive and pervasive impact on the experience of staff in acute wards across Victoria. Quantitative data showed that staff identified the Safewards model and interventions as having a role in reducing physical and verbal conflict in wards and resulted in staff feeling safer. Qualitative data highlighted that staff experienced a shift in culture, resulting in better relationships with consumers and between staff, as well as a renewed focus on patient-centered, recovery-oriented care. Staff in particular described a less uneven relationship with consumers, suggesting that Safewards has an impact on power dynamics that has previously been linked to the use of restrictive interventions (8). Previous research has highlighted that, when staff are custodial rather than caring, the rate of incidents is higher and so is the potential for use of containing or restrictive interventions (41). A significant investment has been made in Australia in attempting to reduce restrictive interventions over the past two decades through law, policy, and practice change. Safewards appears to support these efforts and needs to be consistently implemented with fidelity to the model to continue the downward trajectory now observed in publicly available reports (42, 43). By easily fitting into the ward flow, Safewards can provide the increased motivation, momentum, and support for staff to engage with consumers more therapeutically and from a recovery-oriented perspective. Future research should focus on the intersection of Safewards and recovery-oriented practice on staff well-being and experiences at work. Further work is required to understand how Safewards interacts with other ward activities, such as sensory modulation (44, 45) and legislative coercion (46).

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with and after recommendations from Victorian Human Research Ethics Multi-site process (ID 15225L). Participants were provided a Plain Language Statement. Consent was indicated on the first page of the online survey where participants were asked to “Please tick on the following statement to indicate that you have read and understood the participant information.” Completion of online surveys was anonymous. The protocol was approved by the Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee.

Author Contributions

JF and BH were involved in the development of the study, data collection, and analysis. JF, BH, and LB were involved in the interpretation of data. JF, BH, SK, and LB were involved in the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper forms part of the work toward a PhD, which is supported through an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. JF is supported by NHMRC PhD Research Scholarship 1133627. SK is supported by NHMRC Research Fellowship APP1078168. The Department of Health and Human Services, Government of Victoria funds clinical services across the state. This independent evaluation was financially supported by the Office of the Chief Mental Health Nurse, in the Department of Health and Human Services, Government of Victoria.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The researchers are indebted to staff and consumers in the trial sites for cooperation with fidelity measurement.

References

1. Commonwealth of Australia. A national framework for recovery-oriented mental health services:Policy and theory. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia (2013).

2. Davidson L. The recovery movement: implications for mental health care and enabling people to participate fully in life. Health Aff (2016) 6:1091. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0153

3. Byrne L, Happell B, Reid-Searl K. Recovery as a lived experience discipline: a grounded theory study. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2015) 36(12):935–43. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1076548

4. Slade M, Amering M, Farkas M, Hamilton B, O’Hagan M, Panther G, et al. Uses and abuses of recovery: implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry (2014) 13(1):12–20. doi: 10.1002/wps.20084

5. Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehab J (1993) 16(4):11. doi: 10.1037/h0095655

6. Commonwealth of Australia. National mental health policy 2008. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia (2009).

7. Sailas EES. Seclusion and restraint for people with serious mental illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2012) 6:1–18. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001163

8. Larsen IB, Terkelsen TB. Coercion in a locked psychiatric ward: perspectives of patients and staff. Nurs Ethics (2013) 21:426–36. doi: 10.1177/0969733013503601

9. Baker JA, Bowers L, Owiti JA. Wards features associated with high rates of medication refusal by patients: a large multi-centred survey. Gen Hosp Psychiatry (2009) 31(1):80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.005

10. Bower FL, McCullough CS, Timmons ME. A synthesis of what we know about the use of physical restraints and seclusion with patients in psychiatric and acute care settings: 2003 update. Online J Knowl Synth Nurs (2003) 10:29p–p. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2003.00001.x

11. Brophy LM, Roper CE, Hamilton BE, Tellez JJ, McSherry BM. Consumers and carer perspectives on poor practice and the use of seclusion and restraint in mental health settings: results from Australian focus groups. Int J Ment Health Syst (2016) 10:6. doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0039-9

12. Gilburt H, Rose D, Slade M. The importance of relationships in mental health care: a qualitative study of service users’ experiences of psychiatric hospital admission in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res (2008). doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-92

13. Happell B. Appreciating the importance of history: a brief historical overview of mental health, mental health nursing and education in Australia. Int J Psychiatr Nurs Res (2007) 12(2):1439–45.

14. Waldemar AK, Korsbek L, Petersen L, Esbensen BA, Arnfred S. Recovery orientation in mental health inpatient settings: inpatient experiences? Int J Ment Health Nurs (2018) 27(3):1177–87. doi: 10.1111/inm.12434

15. Cusack E, Killoury F, Nugent LE. The professional psychiatric/mental health nurse: skills, competencies and supports required to adopt recovery-orientated policy in practice. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2017) 2–3:93. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12347

16. Slemon A, Jenkins E, Bungay V. Safety in psychiatric inpatient care: the impact of risk management culture on mental health nursing practice. Nurs Inq (2017) 24(4):e12199. doi: 10.1111/nin.12199

17. Happell B, Harrow A. Nurses’ attitudes to the use of seclusion: a review of the literature. Int J Ment Health Nurs (2010) 19(3):162–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00669.x

18. Bilici R, Sercan M, Izci F. Levels of the staff’s exposure to violence at locked psychiatric clinics: a comparison by occupational groups. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2016) 37(7):501–6. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2016.1162883

19. Chambers M, Kantaris X, Guise V, Valimaki M. Managing and caring for distressed and disturbed service users: the thoughts and feelings experienced by a sample of English mental health nurses. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2015) 22(5):289–97. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12199

20. Seed MS, Torkelson DJ, Alnatour R. The role of the inpatient psychiatric nurse and its effect on job satisfaction. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2010) 31(3):160–70. doi: 10.3109/01612840903168729

21. Stenhouse RC. ‘They all said you could come and speak to us’-: patients’ expectations and experiences of help on an acute psychiatric inpatient ward. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2011) 18(1):74–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01645.x

22. Donald F, Duff C, Lee S, Kroschel J, Kulkarni J. Consumer perspectives on the therapeutic value of a psychiatric environment*. J Ment Health (2015) 24(2):63–7. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2014.954692

23. Thibeault CA, Trudeau K, Entremont M, Brown T. Understanding the milieu experiences of patients on an acute inpatient psychiatric unit. Arch Psychiatr Nurs (2010) 24:216–26. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2009.07.002

24. Rise MB, Westerlund H, Bjorgen D, Steinsbekk A. Safely cared for or empowered in mental health care? yes, please. Int J Soc Psychiatry (2014) 60(2):134–8. doi: 10.1177/0020764012471278

25. Goulter N, Kavanagh DJ, Gardner G. What keeps nurses busy in the mental health setting? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2015) 22(6):449–56. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12173

26. Whittington D, McLaughlin C. Finding time for patients: an exploration of nurses’ time allocation in an acute psychiatric setting. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2000) 7(3):259–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2000.00291.x

27. Killaspy H, Johnson S, Pierce B, Bebbington P, Pilling S, Nolan F, et al. Successful engagement: a mixed methods study of the approaches of assertive community treatment and community mental health teams in the REACT trial. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2009) 44(7):532–40. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0472-4

28. McAndrew S, Chambers M, Nolan F, Thomas B, Watts P. Measuring the evidence: reviewing the literature of the measurement of therapeutic engagement in acute mental health inpatient wards. Int J Ment Health Nurs (2014) 23(3):212–20. doi: 10.1111/inm.12044

29. Bowers L, Alexander J, Bilgin H, Botha M, Dack C, James K, et al. Safewards: the empirical basis of the model and a critical appraisal. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2014) 4:354. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12085

30. Bowers L. Safewards: a new model of conflict and containment on psychiatric wards. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2014) 21(6):499–508. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12129

31. Safewards (2015). Safewards Interventions London: Institute of Psychiatry, Available from: http://www.safewards.net/interventions.

32. Bowers L, James K, Quirk A, Simpson A, SUGAR, Stewart D, et al. Reducing conflict and containment rates on acute psychiatric wards: the Safewards cluster randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud (2015) 52:1412–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.05.001

33. Price O, Burbery P, Leonard S-J, Doyle M. Evaluation of safewards in forensic mental health. Ment Health Prac (2016) 19(8):14–21. doi: 10.7748/mhp.19.8.14.s17

34. Higgins N, Meehan T, Dart N, Kilshaw M, Fawcett L. Implementation of the safewards model in public mental health facilities: A qualitative evaluation of staff perceptions. Int J Nurs Stud (2018) 88:114–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.08.008

35. Maguire T, Ryan J, Fullam R, McKenna B. Evaluating the introduction of the safewards model to a medium- to long-term forensic mental health ward. J Forensic Nurs (2018) 4:214. doi: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000215

36. Stensgaard L, Andersen MK, Nordentoft M, Hjorthoj C. Implementation of the safewards model to reduce the use of coercive measures in adult psychiatric inpatient units: an interrupted time series analysis. J Psychiatr Res (2018) 105:147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.08.026

37. Fletcher J, Spittal M, Brophy L, Tibble H, Kinner SA, Elsom S, et al. Outcomes of the victorian safewards trial in 18 wards: impact on seclusion rates and fidelity measurement. Int J Ment Health Nurs (2017) 26:461–71. doi: 10.1111/inm.12380

38. Fletcher J, Buchanan-Hagen S, Brophy L, Kinner S, Hamilton B. Consumer perspectives of safewards impact in acute inpatient mental health wards in Victoria, Australia. Front Psychiatry (2019) 10:461. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00461

39. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol (2006) 3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

40. Papadopoulos C, Bowers L, Quirk A, Khanom H. Events preceding changes in conflict and containment rates on acute psychiatric wards. Psychiatr Serv (2012) 63(1):40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201000480

41. Gudde CB, Olso TM, Whittington R, Vatne S. Service users’ experiences and views of aggressive situations in mental health care: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. J Multidiscip Healthcare (2015) 8:449–62. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S89486

42. Victorian Government. Victoria’s Mental Health Services Annual Report 2015-2016. 1 Treasury Place, Victoria: Victorian Governement (2016).

43. Oster C, Gerace A, Thomson D, Muir-Cochrane E. Seclusion and restraint use in adult inpatient mental health care: an Australian perspective. Collegian (2016) 23(2):183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2015.03.006

44. Andersen C, Kolmos A, Stenager E, Andersen K, Sippel V. Applying sensory modulation to mental health inpatient care to reduce seclusion and restraint: a case control study. Nord J Psychiatry (2017) 71(7):525–8. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2017.1346142

45. McEvedy S, Maguire T, Furness T, McKenna B. Clinical education: sensory modulation and trauma-informed-care knowledge transfer and translation in mental health services in Victoria: evaluation of a statewide train-the-trainer intervention. Nurse Educ Pract (2017) 25:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.04.012

Keywords: mental health service, safewards, inpatient psychiatry, restrictive practices, recovery oriented care

Citation: Fletcher J, Hamilton B, Kinner SA and Brophy L (2019) Safewards Impact in Inpatient Mental Health Units in Victoria, Australia: Staff Perspectives. Front. Psychiatry 10:462. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00462

Received: 04 January 2019; Accepted: 12 June 2019;

Published: 10 July 2019.

Edited by:

Christian Huber, University Psychiatric Clinic Basel, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Owen Price, University of Manchester, United KingdomGeoffrey Linden Dickens, Western Sydney University, Australia

Copyright © 2019 Fletcher, Hamilton, Kinner and Brophy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Justine Fletcher, anVzdGluZS5mbGV0Y2hlckB1bmltZWxiLmVkdS5hdQ==

†ORCID: Justine Fletcher, orcid.org/0000-0002-5045-6431; Bridget Hamilton, orcid.org/0000-0001-8711-7559; Stuart A. Kinner, orcid.org/0000-0003-3956-5343; Lisa Brophy, orcid.org/0000-0001-6460-3490

Justine Fletcher

Justine Fletcher Bridget Hamilton

Bridget Hamilton Stuart A. Kinner3,4,5,6†

Stuart A. Kinner3,4,5,6† Lisa Brophy

Lisa Brophy