- 1Professorial Unit, The Melbourne Clinic, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2The Melbourne Clinic, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition, School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Deakin University, Geelong, VIC, Australia

- 4Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia

- 5NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Westmead, NSW, Australia

Background: Metabolic syndrome and co-morbid physical health conditions are highly prevalent in people with a mental illness. Modifiable lifestyle factors have been targeted to improve health outcomes. Healthy Body Healthy Mind (HBHM) program was developed to provide an integrated evidence-based program incorporating practical diet and exercise instruction; alongside meditation and mindfulness strategies, and comprehensive psychoeducation, to improve the physical and mental health of those with a mental illness.

Methods: We report on two data points: (1) Qualitative data derived from the first HBHM program (version 1) exploring its utility and acceptance according to patient feedback; (2) Biometric and mental health data collected on the modified and enhanced 12-week HBHM program (version 2) involving a pilot of 10 participants. Mental and physical health outcomes, weight, abdominal circumference, fasting glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides were measured at program entry and completion.

Results: Qualitative data from HBHM version 1 provided valuable feedback to redevelop and enhance the program. At the end of the HBHM (version 2) 12-week program, a significant mean weight loss of 2 kg was achieved, p = 0.023. There was also a significant reduction in abdominal circumference (mean = 2.55 cm) and a decrease in BMI of almost one point (mean = 0.96 kg/m2), p = 0.046 and p = 0.019, respectively. There were no significant changes in mental health measures or on any other biometrics.

Conclusion: Pilot data from the HBHM program found significant reductions in weight and abdominal obesity. The HBHM program could benefit from further modifications, and study replication is required using a controlled design in a larger sample.

Introduction

A highly complex relationship exists between physical and mental health. The rates of physical morbidity and mortality in people with mental illness is substantially higher than the general population (1, 2). Even in countries with adequate health care systems, the mortality gap is on the rise, up to a difference of 20 years (3). Obesity and related conditions such as cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidaemia, and diabetes mellitus are highly prevalent in people with mental illness (4).

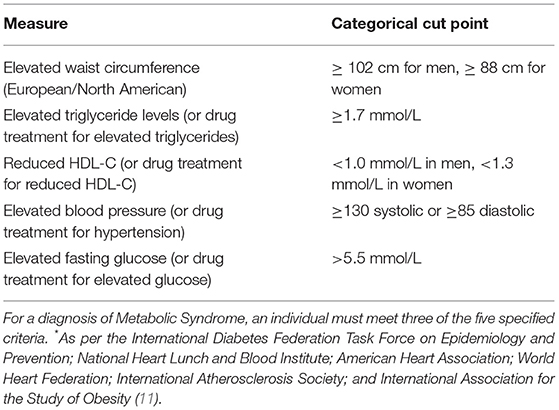

The cluster of symptoms associated with these lifestyle diseases such as, excess visceral fat, along with hypertension, glucose intolerance/insulin resistance, and/or hyperlipidaemia has been labeled Metabolic Syndrome (MetS). In mental health populations, the rate of MetS is thought to be between 41 and 67% (5). A large proportion of the physical health burden in patients with a mental illness can be linked to side effects of second generation antipsychotics, lifestyle factors (e.g., higher rates of smoking, low levels of exercise), and factors associated with socioeconomic disadvantage (e.g., poverty and lack of access to nutritious foods) (6). Weight gain can result in lowered self-esteem, impaired body-image, and reduced social interactions, which can ultimately lead to poorer mental health (7). Furthermore, it is also a common cause of medication non-adherence, which can lead to illness relapse, hospitalization, and poorer outcomes (7, 8).

There is potential to modify lifestyle factors that contribute to MetS (e.g., caloric intake, physical activity levels, sleep hygiene) to improve the health and well-being of people with a mental illness. There are calls for an integrated response involving early diagnosis, treatment and management of physical and mental health via lifestyle modification (9). Several lifestyle-based programs have been developed to modify the lifestyle factors contributing to MetS (10). These programs typically focus on exercise and nutrition for metabolic issues and result in minimal weight loss and modest effects on well-being (10). In one review of lifestyle interventions in adults with a serious mental illness at risk of MetS, few programs incorporated behavioral components such as stress management and motivation alongside exercise and/or nutrition interventions (10). Thus, programs that target both mental and physical outcomes in patients who are taking psychotropic medication have not been adequately developed. Further, previous programs often do not provide a truly “integrative” model, tending to focus on nutrition and exercise without incorporating components that may improve general health and well-being (10).

To bridge the gap and provide an evidence-based integrated health approach, we developed the “Healthy Body, Healthy Mind Program (HBHM).” The aim was to assist people with a diagnosed mental illness and metabolic syndrome to improve mental and physical well-being. We presently report on: (1) Qualitative data derived from our first version of the HBHM program in 2011, exploring its utility and acceptance according to patient and clinician feedback; (2) Biometric data and mental health data collected on the modified and enhanced 12-week, second version of HBHM program involving a pilot of 10 participants.

Materials and Methods

Setting And Overview

The Melbourne Clinic in Melbourne, Australia is a private psychiatric hospital with inpatient and outpatient services. The clinic had a longstanding weight management and lifestyle program, called Healthy Body Healthy Mind (HBHM), developed and facilitated by a general practitioner (GP), exercise physiologist and dietitian. HBHM program (version 1) provided weekly nutritional support from a dietitian, psychoeducation sessions on lifestyle modification and exercise practicals with an exercise physiologist. In late 2011, ethics approval was granted by The Melbourne Clinic Research Ethics Committee (HREC project number: 209) to collect qualitative data from participants to evaluate the perceived efficacy of the program's content, barriers in implementing the components, and feedback on how it could be improved. The qualitative data collected during 2011–2012 was used to redevelop and enhance the integrated lifestyle program which was pilot-tested at The Melbourne Clinic in 2016 (HREC project number: 249). This modified second program will henceforth be labeled as HBHM program (version 2).

Recruitment

Patients attending The Melbourne Clinic outpatient services were invited to attend the program via a doctor's referral. Patients with a diagnosed mental illness (e.g., Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder; or with multiple diagnoses) taking stable psychotropic medication (same dose for at least 4 weeks) with co-morbid diagnosed metabolic syndrome (see Table 1) or obesity (defined as a BMI of >30 OR abdominal circumference of >80 cm for women and >94 cm for men) were the target participants for the program. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants to evaluate the two versions of the program.

HBHM Version 2 (2016) Measures

At week 0, a range of medical and demographic information was collected including, age, gender, employment status, medication information, psychiatric diagnosis and medical co-morbidity. At week 0 and week 12, participants also had anthropometric measurements taken by an exercise physiologist (BP, height, weight, abdominal circumference) and completed self-report questionnaires on their mental health (Depression Anxiety Stress Scales—DASS-21). In addition at week 0, participants were asked to state their goals for the program and what they hoped to achieve. They were also asked to rate their readiness to change in order to achieve their listed goals on a scale of 1–10 with 1 being “not ready” and 10 being “ready.” Participants were provided with a blood test request form to have fasting cholesterol, glucose and triglycerides measured at week 0 and week 12. The blood tests were conducted by Australian Clinical Labs.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales—DASS-21

The DASS-21 is a self-reported screening instrument used to measure depression, anxiety and stress symptomatology (12). It consists of 21-items, across three scales, which measure symptoms of depression (7 items), anxiety (7 items), and stress (7 items). Individuals are asked to respond to each item on a four-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 3 = very much or most of the time). Higher scores on each scale are indicative of greater symptom severity. Scores above 11 (depression), 8 (anxiety), and 13 (stress) are considered severe, as indicated by the recommended cut-offs (12).

Statistics

Qualitative data assessing the 2011 HBHM Program (version 1) was analyzed from written participant feedback forms. Comments were coded and grouped in categories by theme (beneficial/useful content, barriers to implementation and program improvements) and counted to obtain a frequency of mention by the 12 participants. For the quantitative data from the 2016 HBHM program (version 2), paired t-tests and Pearson's r correlations were used to compare the repeated measurements of the sample (week 0 vs. week 12). All data was analyzed in SPSS 24. An alpha level of <0.05 was used to determine significance.

Results

HBHM Version 1 (2011)—Qualitative Data

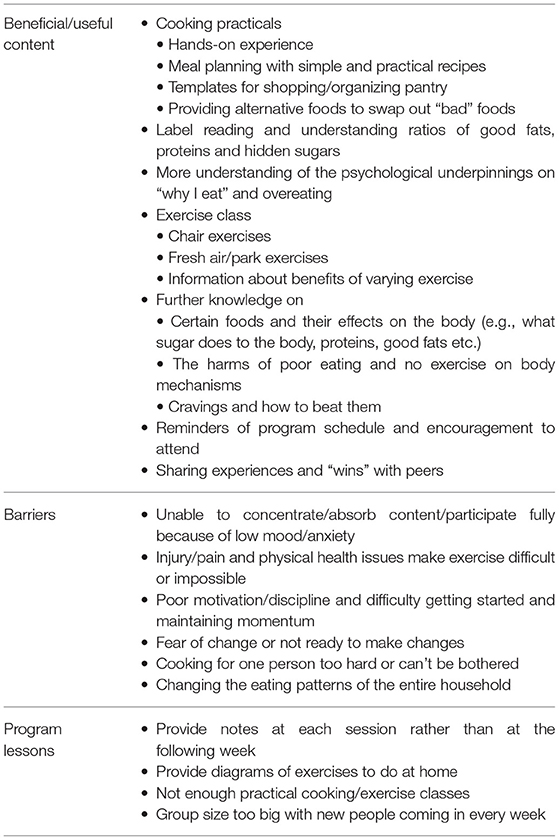

Written qualitative data from 12 participants (83% female; mean age 43.4 years old) who participated in the first version of the HBHM program during 2011–2012 was thematically analyzed to aid the development of the 2016 HBHM program. Table 2 summaries the qualitative data on the early program.

The most beneficial/useful components of the program reported by the majority of participants were the cooking and exercise practicals (n = 11; 91%). One participant commented that he/she needed “practical examples that can be implemented in day-to-day life” and less theory in order to engage with the program. However, many participants (n = 9; 75%) commented that furthering their knowledge on how food effects the body and the harms of nutritionally poor food and no exercise on the body's functioning was useful as, “understanding aids motivation to change, oversimplification does not.” Poor motivation (n = 4; 33%), fear of change (n = 3; 25%) and difficulties engaging with the program due to low mood and anxiety (n = 8; 66.7%) were common among participants. Additionally, many participants found cooking for one person and/or maintaining momentum on their own difficult (n = 4; 33%). As one person stated, “[the] desire to try a new recipe is high at time of session but then lost when at home.” Participants requested more diagram-based notes of exercises/recipes and program content to be accessible at home due to poor recall (n = 3; 25%). Injury and co-morbid physical health problems were some of the main barriers in adding exercise to their day-to-day lives (n = 8; 66.67%). At home chair-based exercises and information on how and why to vary exercise was deemed helpful (n = 4; 33.3%).

HBHM Version 2 (2016)—Program Development

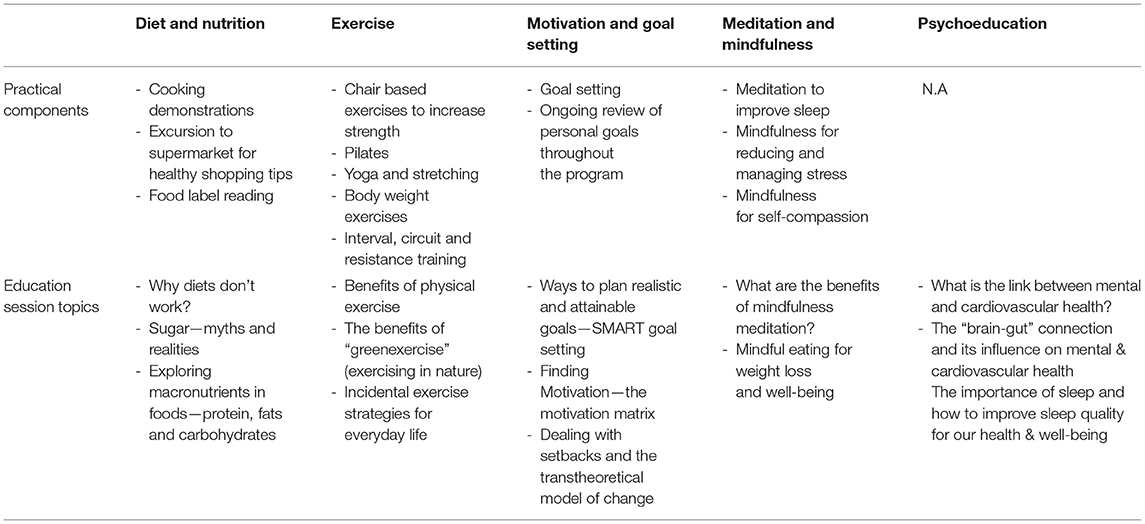

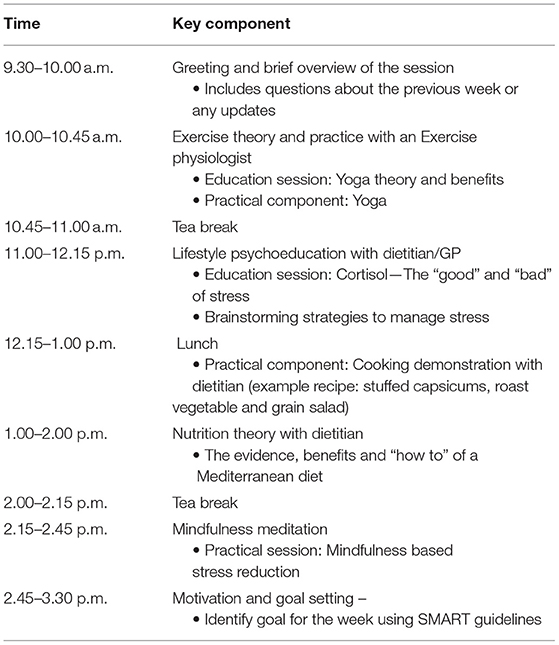

Based on the qualitative data detailed above, the HBHM program in 2016 was remodeled and refined in consultation with a team of experts in the fields of psychiatry, endocrinology/cardiology, nutrition and dietetics, and exercise physiology. The program was designed to integrate five evidence-based components: lifestyle psychoeducation (13), exercise (theory and practicals) (14), diet and nutrition (theory and practical skills e.g., cooking demonstrations and label reading exercises) (15), motivation and goal setting skills (16), and mindfulness techniques (17) (see Table 3). Each week, for 12 weeks, participants attended a 6-h session at TMC, where content and practical exercises from each of the five modules was delivered by an exercise physiologist, dietitian and/or a GP (see Table 3 for examples). Participants were provided with a printed booklet each week outlining content for that session (e.g., psychoeducation theory, exercise diagrams, step by step recipes, label reading guidelines) with areas to take notes and complete tasks such as goal setting activities and shopping lists. Table 4 provides an example program day.

HBHM Version 2 (2016)—Pilot Data

Characteristics

Fifteen patients were referred to the pilot program, five patients declined to participate and ten patients were willing to take part. All participants attended the week 0 and week 12 sessions. Some of the weekly follow-up sessions were missed due to illness or other personal commitments with an average attendance rate of 80%.

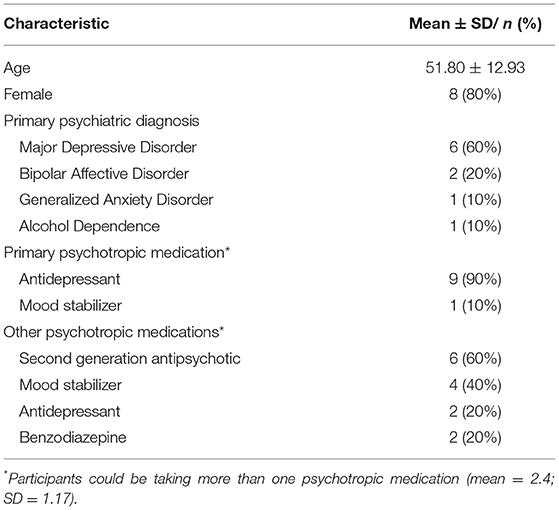

Most of the sample was female (n = 8; 80%) with a mean age of 51.8 years (SD = 12.9 years) (see Table 5). Over half the sample were unemployed/not working or on a disability pension (n = 6; 60%). The most common primary DSM-IV psychiatric diagnosis as reported in the treating psychiatrist referral to the program was Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (n = 6; 60%) followed by Bipolar Affective Disorder (n = 2; 20%), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) (n = 1; 10%) and Alcohol Abuse (n = 1; 10%). Psychiatric co-morbidity was common with diagnoses of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) (n = 3; 30%), Binge Eating Disorder (n = 1; 10%), Borderline Personality Disorder (n = 1; 10%) and Major Depressive Disorder (n = 1; 10%).

All participants were taking psychotropic medications defined as an antidepressant, mood stabilizer, second generation antipsychotic or benzodiazepine. The participant's primary medications were agomelatine (n = 2; 25–50 mg/day), desvenlafaxine (n = 2; 50–100 mg/day), fluvoxamine (n = 2; 200–300 mg/day), paroxetine (n = 1; 20 mg), venlafaxine (n = 1; 75 mg/day); escitalopram (n = 1; 40 mg/day); lamotrigine (n = 1; 50 mg). On average participants were taking 2.4 (SD = 1.17) psychotropic medications ranging from 1 to 4 psychotropic medications. The most common psychotropic medication taken alongside a primary psychotropic medication were second generation antipsychotics (e.g., quetiapine, lurasidone; n = 6; 60%) followed by mood stabilizers (n = 4; 40) (see Table 5).

The most common chronic medical conditions self-reported by participants or as listed in the referral to the program were hyperlipidaemia (n = 4; 40%), hypertension (n = 3; 30%), arthritis (n = 3; 30%), Type II Diabetes (n = 3; 20%), sleep apnoea (n = 2; 20%), and chronic pain/fibromyalgia (n = 2; 20%). Other conditions such as, fatty liver disease (n = 1; 10%), pancreatitis (n = 1; 10%), ulcerative colitis (n = 1; 10%), costochondritis (n = 1; 10%), fructose malabsorption syndrome (n = 1; 10%), endometriosis (n = 1; 10%), restless leg syndrome (n = 1; 10%) and hypothyroidism (n = 1; 10%) wereself-reported.

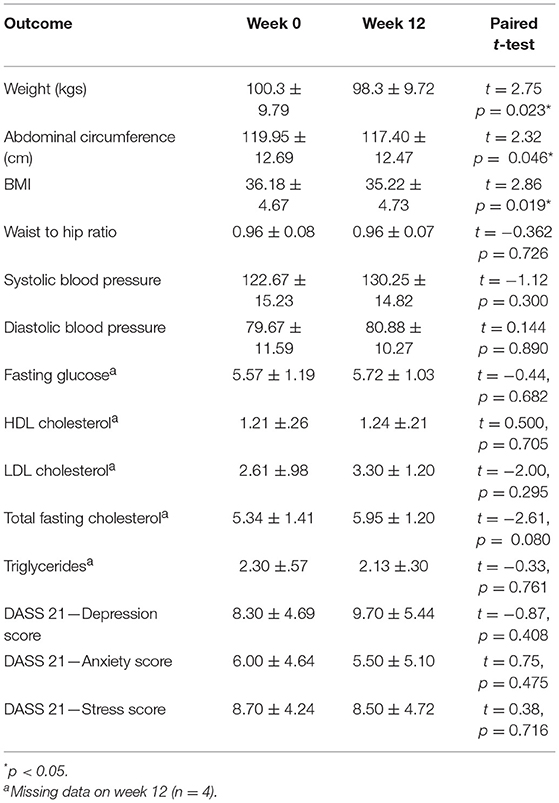

Table 6 presents the anthropometrics of the participants at week 0 and week 12. The average BMI of the cohort at week 0 was 36.18 (SD = 4.67) which, according to the World Health Organization, classes the participants as Obese Class I. As a cohort, the participants also had impaired glucose tolerance as evidenced by a fasting glucose test average >5.5 (mean = 5.57 ± 1.19). The participants' cholesterol and BP were normal, most likely due to their use of prescribed statins and hypertensive medications. According to DASS measurement at week 0, participants had low to moderate levels of depression (mean = 8.30; SD = 4.69), anxiety (mean = 6.0; SD = 4.64), and stress (mean = 8.70; SD = 4.24) symptomatology (see Table 6).

Participant Goals

The most common goal was to increase exercise levels and fitness (n = 5; 50%) followed by eat healthier (n = 4; 40%), reduce sugar intake (n = 3; 30%) and lose weight (n = 3; 30%). On average the participants rated their readiness to change as 7.75 (SD = 2.12) with ratings ranging from 3 to 10. Thus, as a whole the participants were very ready to make change.

Outcome Data

The cohort had a significant weight loss over the 12 weeks with an average loss of 2 kg, t(9) = 2.75, p = 0.023. Weight change ranged from a +1.4 kg weight gain to a −6 kg weight loss. Along with weight loss, there was also a significant reduction in abdominal circumference (mean = 2.55 cm) and a drop in BMI of almost one point (mean = 0.96 kg/m2), t(9) = 2.32, p = 0.046 and t(9) = 0.96, p = 0.019. No significant changes in participant's blood levels or anthropometrics were found. Additionally, no significant changes in participant's mental health was found on the DASS when comparing week 0 to week 12 (see Table 6). Participant's readiness to change (mean = 7.75; SD = 2.12) was not correlated with change in BMI, abdominal circumference, or weight change at end of the program, r = −0.615, p = 0.105, r = −0.205, p = 0.626, and r = −0.692, p = 0.057, respectively.

Discussion

This pilot study found that an integrated 12-week lifestyle program was associated with significant weight loss in patients with a mental illness. We found a mean 2 kg weight loss and a drop in BMI of almost one point across the course of 12 weeks. Our findings are in line with a recent meta-analysis which found lifestyle interventions were superior to treatment-as-usual in producing weight loss in patients with a serious mental illness (18). This improvement in anthropometric measures is clinically significant when considering the challenges experienced by patients with a mental illness in maintaining physical and mental wellness.

No beneficial effect on participant's mental health was found despite incorporating meditation, goal setting, mindfulness, and motivation modules, which was a distinguishing feature of the program. This finding was surprising given mindfulness-based therapies have been consistently related to improvements in mood and anxiety in clinical populations (17). However, a recent lifestyle intervention for residential patients with a serious mental illness also found no positive changes on psychosocial outcomes (19). This suggests that it is challenging to get a beneficial effect on psychosocial outcomes while attempting to improve physical and mental health outcomes simultaneously. The addition of individual psychotherapy alongside participation in the program might be warranted and the incorporation of other evidence-based psychotherapies such as, cognitive behavioral therapy should be considered in future versions of the program. Future iterations of the program should also incorporate quality of life assessments and measures of psychosocial functioning to more accurately assess the program's potential benefit.

Alternatively, the modest effect on participant's mental health during the program could be due to the low baseline levels of depression, anxiety, and stress (as captured on the DASS), and hence had less scope for improvement. Furthermore, when identifying goals of the program, not one participant mentioned they would like to improve their mental health. Rather the goals reported by participants were orientated toward improving their eating habits and losing weight. The incorporation of behavioral and psychological components (such as mindful eating and goal setting) is deemed to benefit the delivery and engagement of the program contents and helped to adhere to recommendations in order to achieve the weight loss results.

A major limitation to the current study was the small sample size and that it was uncontrolled. A larger sample with an appropriate control is required to assess the program effectiveness and allow for further feedback from participants to fine-tune the program. We also recognize that more work is needed to refine the delivery and format structure in respect to determining the best application of the program given costs and time constraints. In particular, the exercise component should aim to provide at least 90 min of moderate-to-vigorous exercise per week, as this intensity has been shown to improve psychiatric symptoms in patients with a serious mental illness (20). Furthermore, closer monitoring of physical activity outside of the program should be employed in order to assess the translational impact of the program to the home environment.

While the 12-week program was comprehensive, it also has its drawback in terms of time requirements, and a 6-h once per week delivery is quite intensive for people with a mental illness. A follow-up should also be employed to determine whether weight loss results are maintained, continued, or regained following the cessation of the program.

There is the potential to restructure the program to have a blend of face-to-face delivery with online components, and even the use of a mobile phone app. This would provide flexibility, less demands on time, and less financial burden for the participants. Weight loss in this population is extremely challenging as many patients have co-morbid medical conditions, and limited social and economic resources. Thus, facilitating weight loss using strategies that can be implemented into everyday life is paramount to success. In addition, implementing and assessing strategies which prevent the all too frequent “weight regain” phenomena is crucial (21).

As 60% of the sample were taking second generation antipsychotics, the results are encouraging for metabolically vulnerable patients. However, it is important to note, that the results cannot be generalized to participants with a serious mental illness as the current pilot did not include participants with schizophrenia who are at the most risk of developing MetS. It is unclear how this particular patient population would engage with this intervention. In conclusion, the pilot data of the HBHM program found significant benefits in reducing weight and abdominal obesity, with the potential to achieve substantial health benefits for patients with a mental illness and co-morbid metabolic syndrome. Study replication is required using a controlled design in a larger sample over a longer time period.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of The National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 and The Melbourne Clinic Ethics Committee. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The projects were approved by the Melbourne Clinic Ethics Committee (Project 209 and 249).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the drafting and editing of the manuscript. JAM and JS is responsible for the data analysis and manuscript preparation. JM, GO, CW, RO, and AB were involved in designing the program, running the program and collecting data. CN and JS contributed to the design of the program and provided oversight of the program.

Conflict of Interest Statement

JS has no direct conflict of interest, however has received either presentation honoraria, travel support, clinical trial grants, book royalties, or independent consultancy payments from: Integria Healthcare & MediHerb, Pfizer, Scius Health, Key Pharmaceuticals, Taki Mai, FIT-BioCeuticals, Blackmores, Soho-Flordis, Healthworld, HealthEd, HealthMasters, SPRIM, Kantar Consulting, Research Reviews, Elsevier, Chaminade University, International Society for Affective Disorders, Complementary Medicines Australia, Grunbiotics SPRIM, Terry White Chemists, ANS, Society for Medicinal Plant and Natural Product Research, Sanofi-Aventis, Omega-3 Centre, the National Health and Medical Research Council, CR Roper Fellowship.

The funders played no role in the study design, the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, the writing of this paper or the decision to submit it for publication.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are extended to The Melbourne Clinic staff for support of this program and for the patients participating in it.

References

1. Everett A, Mahler J, Biblin J, Ganguli R, Mauer B. Improving the health of mental health consumers: Effective policies and practices. Int J Mental Health. (2008) 37:8–48. doi: 10.2753/IMH0020-7411370201

2. Osborn DP, Levy G, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Islam A, King MB. Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom's General Practice Research Database. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2007) 64:242–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.242

3. Lawrence D, Hancock KJ, Kisely S. The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: retrospective analysis of population based registers. BMJ. (2013) 346:f2539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2539

4. De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, Cetkovich-Bakmas MA, Cohen DA, Asai I, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. (2011) 10:52–77. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x

5. John AP, Koloth R, Dragovic M, Lim SC. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Australians with severe mental illness. Med J Australia. (2009) 190:176–9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02342.x

6. Stanley SH, Laugharne JD. Clinical guidelines for the physical care of mental health consumers: a comprehensive assessment and monitoring package for mental health and primary care clinicians. Aust NZ J Psychol. (2011) 45:824–9. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.614591

7. McCloughen A, Foster K. Weight gain associated with taking psychotropic medication: an integrative review. Int J Mental Health Nurs. (2011) 20:202–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00721.x

8. Nihalani N, Schwartz TL, Siddiqui UA, Megna JL. Weight gain, obesity, and psychotropic prescribing. J Obesity. (2011) 2011:893629. doi: 10.1155/2011/893629

9. Lake J, Turner MS. Urgent need for improved mental health care and a more collaborative model of care. Perm J. (2017) 21. doi: 10.7812/TPP/17-024

10. Richards L, Batscha CL, McCarthy VL. Lifestyle and behavioral interventions to reduce the risk of metabolic syndrome in community-dwelling adults with serious mental illness: implications for nursing practice. J Psychosoc Nurs Mental Health Serv. (2015) 54:46–55. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20151109-02

11. Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonishing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart Lunch and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. (2009) 120:1640–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644

12. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. (1995) 33:335–43. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

13. Naslund JA, Whiteman KL, McHugo GJ, Aschbrenner KA, Marsch LA, Bartels SJ. Lifestyle interventions for weight loss among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2017) 47:83–102. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.003

14. Rosenbaum S, Tiedemann A, Ward PB. Meta-analysis physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. (2014) 75:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.11.161

15. Teasdale SB, Ward PB, Rosenbaum S, Samaras K, Stubbs B. Solving a weighty problem: systematic review and meta-analysis of nutrition interventions in severe mental illness. Brit J Psychiatry. (2017) 210:110–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177139

16. Rodriguez-Cristobal JJ, Alonso-Villaverde C, Panisello JM, Travé-Mercade P, Rodriguez-Cortés F, Marsal JR, et al. Effectiveness of a motivational intervention on overweight/obese patients in the primary healthcare: a cluster randomized trial. BMC Fam Pract. (2017) 18:74. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0644-y

17. Rodrigues MF, Nardi AE, Levitan M. Mindfulness in mood and anxiety disorders: a review of the literature. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. (2017) 39:207–15. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2016-0051

18. Singh VK, Karmani S, Malo PK, Virupaksha HG, Muralidhar D, Venkatasubramanian G, Muralidharan K. Impact of lifestyle modification on some components of metabolic syndrome in persons with severe mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. (2018) 202: 17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.06.066

19. Stiekema AP, Looijmans A, van der Meer L, Bruggeman R, Schoevers RA, Corpeleijn E, et al. Effects of a lifestyle intervention on psychosocial well-being of severe mentally ill residential patients: ELIPS, a cluster randomized controlled pragmatic trial. Schizophr Res. (2018) 199: 407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.053

20. Firth J, Cotter J, Elliott R, French P, Yung AR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychol Med. (2015) 45:1343–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714003110

Keywords: healthy lifestyles, lifestyle medicine, metabolic syndrome, depression, program development

Citation: Murphy JA, Oliver G, Ng CH, Wain C, Magennis J, Opie RS, Bannatyne A and Sarris J (2019) Pilot-Testing of “Healthy Body Healthy Mind”: An Integrative Lifestyle Program for Patients With a Mental Illness and Co-morbid Metabolic Syndrome. Front. Psychiatry 10:91. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00091

Received: 14 November 2018; Accepted: 08 February 2019;

Published: 06 March 2019.

Edited by:

Brendon Stubbs, King's College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Nicole Helen Korman, Metro South Addiction and Mental Health Services, AustraliaDan Siskind, Metro South Addiction and Mental Health Services, Australia

Copyright © 2019 Murphy, Oliver, Ng, Wain, Magennis, Opie, Bannatyne and Sarris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jenifer A. Murphy, j.sarris@westernsydney.edu.au

Jenifer A. Murphy

Jenifer A. Murphy Georgina Oliver1

Georgina Oliver1 Jerome Sarris

Jerome Sarris