- 1Faculty of Education, Krongold Clinic, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2Wellways Australia Incorporating Australian HealthCall Group, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3The Bouverie Centre, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 4School of Nursing, Midwifery & Paramedicine, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 5NorthWestern Mental Health, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 6Department of Rural Health, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

The transition to adulthood can be a vulnerable period for certain population groups. In particular, young adults aged 18–25 years who have a parent with mental illness and/or substance use problems face increased risks to their mental health compared to same aged peers. Yet these young adults may not have access to age-appropriate, targeted interventions, nor engage with traditional face-to-face health services. To support this vulnerable group, services need to engage with them in environments where they are likely to seek help, such as the Internet. This paper describes the risk mechanisms for this group of young adults, and the theoretical and empirical basis, aims, features and content of a tailored online group intervention; mi.spot (mental illness: supportive, preventative, online, targeted). The participatory approach employed to design the intervention is described. This involved working collaboratively with stakeholders (i.e., young adults, clinicians, researchers and website developers). Implementation considerations and future research priorities for an online approach targeting this group of young adults conclude the paper.

Background

A key risk factor to young peoples' mental health and wellbeing is having a parent with a mental illness and/or substance use problem (1). The mechanisms underlying this association are accumulative and involve interactions between genetic, individual, parent, familial, environmental, and societal factors (1). Parental mental illness or substance use problems have been associated with various adverse outcomes for young people, including the development of their own mental illness or substance use problem, academic failure, high incarceration rates, and stress-related somatic health conditions such as asthma (2–5). These adverse impacts may be maintained into adulthood. The transition period from adolescence to adulthood is a critical time to intervene and attempt to reduce the onset of mental health problems (6). Given that 21–23% of children grow up with at least one parent with a mental illness (7) and 11.9% of children live with at least one parent who was dependent on or abused alcohol or an illicit drug (8), it is imperative that efforts are made to reduce the risk of intergenerational mental illness and substance misuse.

This article presents the theoretical and empirical basis for an online intervention, mi.spot (mental illness: supportive, preventative, online, targeted) for young adults (aged 18–25 years) whose parents have a mental illness and/or substance use problem. First, the extant literature on the mechanisms by which risk is conferred on these young adults will be reviewed, followed by service gaps and young adults' preferences for support. This literature provides the foundation for a theoretical approach to the development of the online intervention, mi.spot. The approach employed to develop mi.spot is then described, followed by an outline of the intervention. The issues associated with introducing a new intervention such as mi.spot into regular service delivery, and opportunities for future research conclude the paper.

Mechanisms of Risk Related to Mental Health Among Young Adults

Mental health disorders account for the highest burden of disease in adolescence and young adulthood. The majority of lifetime prevalence for mental health conditions occurs by 24 years of age, and substance abuse disorders by 25 years (6). According to Arnett (9), emerging adulthood is a distinct transitional period between adolescence and young adulthood (18–25 years) that marks a major transition in terms of identity, work, relationships, and place of residence. The changing roles and increasing levels of responsibility during this period increases stress (10) which may precipitate depressive episodes (11). Additionally, substance use problems and risky sexual practices increase during these ages (10). However, young adults have lower rates of mental illness treatment than adults or adolescents (12) and only 35% of young people experiencing mental health problems seek professional help (13) due to access issues and stigma (14). Although peer relationships are integral in this developmental phase, decreases in social support, which may occur as young people leave school, are linked with increases in depressive symptoms (15). During this transitional period emotional stability is not yet established, specifically dysregulation of anger, which is high compared to other age groups (16).

There are various mechanisms involved in the transmission of mental illness for young adults whose parents have a mental illness and/or substance use problem. The first potential risk mechanism is young adults' relationship with their parent and their need for independence. Marsh and Dickens (17) found that some young adults find it challenging to separate themselves from their families to pursue normative developmental tasks such as attending university. When they do attend university, these young adults describe greater psychosocial adjustment difficulties than their peers (18). Mitchell and Abraham (19) found that amongst university students, those with a parent with a mental illness experienced higher levels of homesickness compared to other young adults. Likewise, Bountress et al. (20) found that young adults whose parents had substance use problems were more likely to have negative experiences during the leaving home transition. In turn, this predicted an increased risk of affective disorders in adulthood. They suggested that parents with substance use problems may attempt to limit their children's independence from the family of origin or fail to appropriately scaffold their leaving home transition. Family dynamics can be strained. Abraham and Stein (21) found that young adults with a mother with a mental illness reported lower levels of affection from their mothers compared to their same aged peers who did not have a mother with a mental illness. Relatedly, parents with substance use problems have been found to be more emotionally withdrawn from their young adult children and to show less sensitivity and more hostility toward them, compared to those whose parents do not have substance use problems (20, 22).

Similarly, many young adults find it difficult to be emotionally independent from their parent who has a mental illness or substance use problem. Drawn from interviews with 12 young people aged 13–26 whose parents had substance use problems, Wangensteen et al. (23) described their struggle in balancing emotional closeness and distance with their parent. In particular, those aged 18–26 felt sorry for their parent and described a sense of obligation toward them and the subsequent struggle to separate themselves emotionally when they moved out of home. As some young adults whose parents have a mental illness find it difficult to be emotionally independent, they may find it challenging to regulate their emotions (24). Such research may explain, at least partially, why some young adults experience difficulty forming close personal or romantic relationships (3, 25). Kumar and Mattanah (26) found that early attachments provide a template for romantic and other relationship developments in early adulthood, and this appears to be particular pertinent for young adults whose parents have a mental illness or substance use problem.

Role reversal, parentification or caring responsibilities are other mechanisms of risk for this group of young adults (27). They may be given or assume the responsibility of caring for their parent and siblings and maintaining the household (25). These responsibilities may have adverse impacts on employment, schooling, and friendship groups (28, 29). Developmentally, stigma and a sense of shame associated with mental illness may increase as adolescents and young adults appreciate the manner in which others in the community perceive those with a mental illness, and so impede help-seeking for themselves and their family (30).

Whether children of parents with different mental health concerns have the same mechanisms of risk and subsequent intervention needs are questions that have been previously debated in the literature (31). In two systematic reviews of the impact of different parental mental illness on children's own diagnosis, van Santvoort et al. (32, 33) found that children of parents across the spectrum present with a broad-range of adverse outcomes, not limited to their parents' diagnosis. On this basis, the authors suggest that all children can be offered the same intervention, though simultaneously suggest that additional, tailored interventions might be required, such as might arise through the exposure to violence or abuse (33). Others have also argued that across diagnostic groups, young people may be exposed to similar familial and contextual stressors such as marital discord, housing instability, isolation, and poverty (27). Other common risks across parental diagnoses might include stigma, caring responsibilities, and a lack of accurate knowledge about their parent's illness (1, 27).

Young adults have highlighted a lack of knowledge about their genetic vulnerability to addiction and mental illness (34). While younger children are often left out of explanations about their parent's illness, Seurer (35) suggests that, for parental depression at least, some young adults may be viewed by their parents as confidantes even though these discussions do not always provide the full picture of what is happening for the parent. Knowing more about mental illness/substance use and in particular their parent's specific illness can help young adults understand and distance themselves from their parent (36, 37).

During the transition to adulthood, parental control declines while the influence of peers gain in importance (38). Similarly, young adults seek support and information from their peers, rather than parents (39). Giving opportunities to share experiences with peers is important when services want to connect with difficult to engage populations (40) and is also important for young people whose parents have a mental illness or substance use problem (41). Klodnick et al. (42) found that for young adults, associating with peers who have similar mental health experiences can provide strong affectional bonds, meaningful connections and useful exchanges about services. Emerging adulthood is perhaps the first time when individuals can formulate a “new and ideally integrative understanding of one's life story” and integrate “different personifications of the self within a single self-defining life story” (43). Thus, young adults may be actively involved in the communicative sense-making processes in coming to terms with their parent's illness or substance use and can articulate and share their life experiences with others (35), and if given the opportunity, with their peers (44).

In summary, the transition to adulthood can be a vulnerable period especially for those whose parents have mental illness and/or substance use problems. At the same time, emerging adulthood represents an ideal time to develop new strategies and foci in readiness for adulthood, in relation to key developmental tasks, such as identity formation, role transition, the formation of new social connections and intimate romantic attachments, and independence from parents. Moreover, promoting access to treatment services is necessary to improve mental health outcomes and reduce the burden of mental illness, especially those aimed at increasing young adults' willingness to seek help (45).

Available Interventions and Service Gaps

There are various evidence-based interventions developed for children and young people aged under 18 years, who have a parent with a mental illness or substance use problem. These include peer support programs, family interventions and psychoeducational resources (46). In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Siegenhaler et al. (47) found that the risk of acquiring a parent's mental illness was reduced by 40% for children participating in targeted interventions. Most interventions for children and young people in these families draw on cognitive, behavioural, and/or psychosocial theories and deliver topics on mental health literacy, adaptive coping, and problem solving (48). However, the majority of interventions for children and young people in these families are limited to those aged under 18 years (48).

When asked about their preferred supports, adolescents aged 13–17 years and living in families where a parent has a mental illness or substance use problem, reported a clear preference for online supports (41). Extending that study, Matar et al. (44) employed a Delphi study with 282 young adults aged 16–21 years and whose parents had a mental illness and/or substance use problem and asked them what they wanted from an online intervention. Online opportunities to share with other young adults living in similar families was a common request as were topics on psycho-education, managing the parent-child relationship, and strategies to build resilience, and improve mental health, wellbeing, and coping. Finally, they wanted assurances that any online bullying would be dealt with appropriately.

There are some online interventions (mostly from the Netherlands) for young people whose parents have mental illness though these are still in the early stages of development and generally target both adolescent and young adults. These interventions include Survivalkid for 12–25 year olds (49, 50), Grubbel for 15–25 year olds (51) and Kopstoring for 16–25 year olds (52). To date, one randomised controlled trial evaluation has been completed on Kopstoring with positive trends found toward a reduction in internalising symptoms (52). No significant differences were found in self-reported depressive symptoms or internalising problems compared to treatment as usual in a 3-month follow-up, though the authors suggested this might be due to problems with the evaluation design (52). These interventions are based in Europe and developed specifically for those sociocultural and mental health service contexts. To date, there have been no reported interventions for this group of young adults from English-speaking countries, including Australia.

To succeed in identifying and supporting young adults who have a parent with a mental illness and/or substance use problem, services need to engage with young adults in environments where they seek help and interact. Wetterlin et al. (53) found that 61.6% of 521 young adults aged between 17 and 24 years had utilised the Internet to access information or seek help for how they were feeling, and 82.9% indicated that they were likely to use a mental health website to find information in challenging times. As young adults often prefer anonymous sources of help to traditional services (54), online interventions provide an ideal opportunity to intervene with this vulnerable group. Online approaches are important as they have the potential to link young adults with others in similar situations, especially those in rural and remote areas (55).

The present paper is the first to provide a theoretical overview and empirical basis for an online intervention for this particular group of vulnerable young adults from an English-speaking country. Indeed, theoretical frameworks for online interventions are often missing (56) but critical for ongoing intervention monitoring and evaluation (57).

mi.spot: Developing an Online Approach

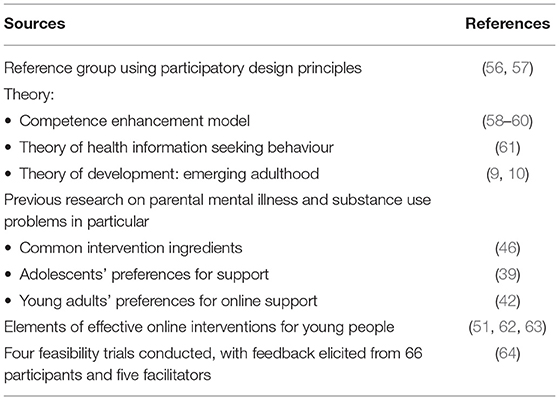

The mi.spot intervention was developed iteratively over a 36 month period using participatory design principles and drawing on relevant theory, existing research and feedback from feasibility trials (see Table 1).

From the outset, a participatory design approach was employed (58, 59) through the creation and facilitation of a reference group consisting of researchers, clinicians, website designers, and young adults who have lived experience of parents with mental illness and/or substance use problems. The group was collaborative and collegiate with all stakeholders recognised as having different but equally important skills to offer. In particular, young adults were included to ensure that the intervention was user friendly and acceptable and clinicians were involved as the intervention needed to be clinically feasible. It was acknowledged that what young people want can be different from what parents and clinicians believe they need (60), which meant privileging the views of the young people on the reference group, especially in regard to site aesthetics and content and in terms of how clinicians might respond to young people's questions and concerns. Regular face-to-face meetings were facilitated with the aim of raising a diversity of views and learning from each other. Different members of the group had worked together previously (on other research projects, or on face-to-face peer support programs) which provided opportunities for capacity building. The reference group met regularly over 36 months to discuss website developments and the implications of research (see below) to the website. Notes were taken at each meeting to document decisions and follow-up meetings with individuals were conducted as required to ensure that all perspectives were considered. Overall, the participatory design approach covered several phases; the identification of problems for young people living these families (drawing on existing research, see below) the generation of solutions, the development of and feedback on an online intervention, and the development of an implementation and evaluation strategy, including dissemination procedures.

Theoretically, mi.spot is based on the competence enhancement model, discussed in detail by Barry (65). The model takes a lifespan approach to the promotion of mental health, and focuses on enhancing strengths and promoting resilience (61, 65). According to Eccles and Appleton (62), the model is most beneficial when there are explicit efforts to promote connections to others and enhance participants' competence in developmentally appropriate domains. Cognitive and behavioural approaches are commonly incorporated within the competence enhancement model (62), given their effectiveness and efficacy in improving dysfunctional cognition, regulating emotions and the promotion of adaptive problem solving (63). The theory of development for young adults was used for the current intervention, with a focus on identify formation, managing relationships and independence (9, 10). Additionally, the theory of health information seeking behaviour (64) was applied to promote optimal use of the intervention. This approach acknowledges the role of passive and active retrieval of information, and the role of peers and clinicians in helping to process and interpret information (64).

In terms of research, the intervention drew on previous work that identified the ingredients commonly associated with effective interventions for this target group (48). Previous research that sought the views of young adults whose parents have mental illness and/or substance use problems regarding support in general (41), and online interventions in particular (44), were incorporated. Evidence on online behaviour change interventions was used to inform online functionality, especially those designed for adolescents and young adults (53). A systematic review found that effective online interventions provides opportunities for interaction, personalized and normative feedback, and self-monitoring (66). Likewise, Short et al., (67) drew on user engagement research across multiple disciplines to identify those factors that influence how users engage with online interventions. In their model, engagement is influenced by (i) the environment including the length of time available to the user and the user's access to the Internet (ii) individual factors related to perceived personal relevance and usefulness of the intervention and their expectations and (iii) intervention design including the interactivity, aesthetics, credibility and opportunities to interact with a counsellor. These features were considered in the development of mi.spot.

Seven feasibility trials of mi.spot have been conducted since its inception, with 66 participants. According to Eldridge et al. (68) feasibility trials ascertain whether an intervention can be done, whether it should be done and if so, how. Related issues that feasibility studies may address include participants' willingness to be recruited, the time required to collect and analyze data, and the acceptability and suitability of any given intervention for both clinicians and participants. Various methods were used to recruit participants for mi.spot with Facebook advertisements found to be the most effective and efficient. Feedback from previous participants and online facilitators in semi-structured interviews were used to modify the initial iteration of the intervention. For example, many previous participants wanted to see a greater emphasis on managing friendship, work, and significant relationships and not only managing relationships with their parent and these additions were subsequently incorporated; facilitators requested additional functions such as notification of someone typing (i.e., “…”) in the online group chats to allow for more effective facilitation.

mi.spot: the Intervention

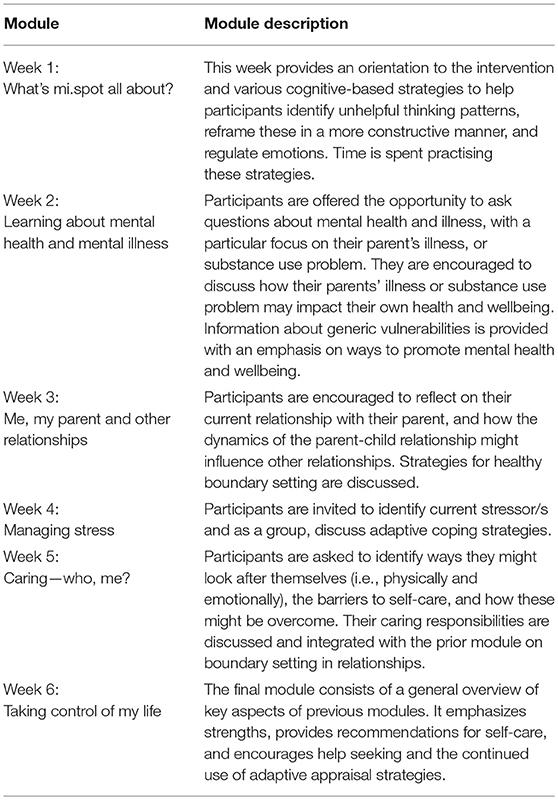

mi.spot is an online, 6 week voluntary intervention for groups of up to 20 young adults (aged 18–25), who have a parent with a mental illness and/or substance use problem. mi.spot aims to (i) improve knowledge about mental health and wellbeing, (ii) promote adaptive coping, (iii) build, expand, and sustain healthy relationships, (iv) increase resilience, (v) encourage help seeking behaviour, (vi) facilitate a sense of peer connection and finally (vii) foster mental health and wellbeing. mi.spot is a manualised approach that offers real time (synchronous) and anonymous peer online networking opportunities and an individually tailored, interactive and professionally led intervention, as evident by the following functions:

• Six, one hour, professionally facilitated psychoeducational modules delivered online in synchronous mode (see Table 2).

• A private, online diary (called mi.thoughts.spot) to prompt and encourage participants to apply a cognitive behavioural approach to current stressful situations, with the support of a facilitator (provided asynchronously).

• Opportunities for participants to chat informally with each other on threads (i.e., topics) initiated by a participant or facilitator.

• Opportunities for one-to-one private online counselling sessions between a participant and a facilitator (synchronous).

• Video, audio, print resources, and self-monitoring questionnaires offered as weekly activities for participants in order to consolidate and extend learning from weekly sessions.

Participants may elect to join all, some or none of the offerings. The password protected site is moderated twice daily including weekends. Procedures exist for rule violations (e.g., online bullying) and risk procedures (e.g., if a participant expresses suicidal thoughts).

Online Facilitator Role and Training

Online facilitators for mi.spot assume an active role in encouraging ongoing, supportive conversations between participants, facilitating the weekly sessions, and providing one to one online counselling sessions as required. They also fulfil a monitoring role and ensure that the site is a safe, respectful space for everyone by identifying and addressing any instances of bullying, harassment, and racism and/or descriptions of harm to self or others.

Currently, facilitators are master's level psychology students working in a university clinic but any qualified mental health clinician would be able to deliver the intervention after appropriate training had been attended. Two days of facilitator training using manualised content are provided. The first day focuses on generic online counselling skills (in both group and individual counselling mode) and the second specifically examines the mi.spot intervention and how it should be delivered. The second day starts with a presentation from two young adults with lived experience who discuss their experiences and preferences for online interactions. The remaining part of the day is spent on simulated training scenarios to practice responses on the site. Fidelity checks for the weekly sessions are built into the intervention at the facilitator level, to ensure all topics are covered. Future considerations are to deliver the training online [as per (69)].

Future Priorities

Building on the current evidence base in this area (52), further randomised controlled trials are needed to establish the effectiveness and efficacy of mi.spot, including cost effectiveness. Comparing the online intervention, mi.spot, with face-to-face peer support programs will be important to evaluate comparative effectiveness. Uptake, engagement and drop out numbers as well as website analytics need to be documented to establish which participants engage with the different components of the intervention and the impact that this may have on participant outcomes. Monitoring of the intervention is required to ascertain to what extent the intervention been implemented as designed (as per the manual) and what modifications might be required. Safety is another evaluation component which may be measured through clinical deterioration related to intervention use and inappropriate use (e.g., online bullying). Developing online interventions for young people aged 13 to 18 years living in these families is another priority.

Further information is needed on how mi.spot may be embedded into services. Batterham et al. (70) identified various barriers for delivering online interventions including policy, safety, and political restrictions, incompatible reimbursement systems, limited availability of trained clinicians, and clinicians' negative attitudes toward Internet interventions. Nonetheless, a recent study found that Australian clinicians were highly supportive of online interventions for this particular group of young people as they acknowledged that many miss out on face-to-face peer support programs (71). Most research on online interventions has focused on efficacy and effectiveness trials, with little investigation on implementation processes (72), making this a priority for future research. Within these deliberations, the applicability and effectiveness of a stepped care model needs to be investigated, where mi.spot may be provided as a first step in intervention, or alternatively delivered in conjunction with individual face-to-face support. Relatedly, a strategy for targeting young people is needed. Building on the successful method of recruiting participants in the feasibility trials using Facebook advertising, other potential approaches include Twitter and YouTube advertisements and by promoting the intervention via various university and community mental health agencies. Young people's input into these approaches will be critical.

At present mi.spot is delivered from a university clinic but our vision is to expand the service into mainstream settings. Which service or services might assume this responsibility is being considered. Child and adolescent mental health services might appear to be an appropriate service but traditionally focus on those aged under 18 years. Others have highlighted the problems transitioning adolescents into the adult mental health system as well as the inappropriateness of adult mental health services for young adults (73). This is concerning, as service inadequacies and gaps during the transitional period from adolescence to adulthood have the potential for long lasting functional difficulties (74). Conversely, compared to standard adult services, age-specific interventions may increase young adults' use of mental health services (75). Given the vulnerability, prevalence, and the unique needs of young adults whose parents have a mental illness or substance use problem, it is crucial that developmentally informed and relevant services and interventions are developed and, arguably more importantly, delivered on a broad scale.

Author Contributions

AR, CB, RC, KF, JM, DM, and LP contributed to the conception of the paper. AR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RC, KF, JM, DM, and LP wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Reupert A, Maybery D, Nicholson J, Gopfert M, Seeman M. Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Distressed Parents and Their Families. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2015).

2. Ensminger ME, Hanson SG, Riley AW, Juon HS. Maternal psychological distress: adult sons' and daughters' mental health and educational attainment. J Am Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry (2003) 42:1108–15. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000070261.24125.F8

3. Duncan G, Browning J. Adult attachment in children raised by parents with schizophrenia. J Adult Dev. (2009) 16:76–86. doi: 10.1007/s10804-009-9054-2

4. Mowbray CT, Bybee D, Oyserman D, MacFarlane P, Bowersox N. Psychosocial outcomes for adult children of parents with severe mental illness: demographic and clinical history predictors. Health Soc Work. (2006) 31:99–108. doi: 10.1093/hsw/31.2.99

5. Mowbray CT, Mowbray OP. Psychosocial outcomes of adult children of parents with depression and bipolar disorder. J Emot Behav Disord. (2006) 14:130–42. doi: 10.1177/10634266060140030101

6. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler JR, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2005) 62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

7. Maybery D, Reupert A, Patrick K, Goodyear M, Crase L. Prevalence of children whose parents have a mental illness. Psychiatry Bull. (2009) 33:22–6. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.107.018861

8. Office of Applied Studies. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. The NSDUH Report: Children Living with Substance-Dependent or Substance-Abusing Parents: 2002 to 2007. Rockville, MD. (2009). Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED525064 (Accessed June 8, 2010).

9. Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. (2000) 55:469–80. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469

10. Arnett JJ, Tanner JI. Emerging Adults in America: Coming of Age in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: APA book (2006).

11. Hagestad GO, Neugarten BL. Age and the life course. In: Bienstock R, Shamus E, editors. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold (1985). p. 35–61.

12. Adams SH, Knopf DK, Park MJ. Prevalence and treatment of mental health and substance use problems in the early emerging adult years in the United States: findings from the 2010 national survey on drug use and health. Emerg Adulthood. (2014) 2:163–72. doi: 10.1177/2167696813513563

13. Andrews G, Issakidis C, Carter G. Shortfall in mental health service utilisation. Br J Psychiatry (2001) 179:417–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.5.417

14. van Doesum K, Riebshleger J, Carroll J, Grove C, Lauritzen C, Skerfving A. Successful recruitment strategies for prevention programs targeting children of parents with mental health challenges: an international study. Child Youth Serv. (2016) 37:156–74. doi: 10.1080/0145935X.2016.1104075

15. Galambos N, Leadbeater B, Barker E. Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: a 4-year longitudinal study. Int J Behav Dev. (2004) 28:16–25. doi: 10.1080/01650250344000235

16. Zimmermann P, Iwanski A. Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. Int J Behav Dev. (2014) 38:182–94. doi: 10.1177/0165025413515405

17. Marsh DT, Dickens RM. Troubled Journey: Coming to Terms With the Mental Illness of a Sibling or Parent. New York, NY: Tarcher/Penguin Group (1997).

18. Abraham KM, Stein CH. Staying connected: young adults' felt obligation towards parents with and without mental illness. J Fam Psychol. (2010) 24:125–34. doi: 10.1037/a0018973

19. Mitchell JM, Abraham KM. Parental mental illness and the transition to college: coping, psychological adjustment and parent-child relationships. J Child Fam Stud. (2018) 27:2966–77. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1133-1

20. Bountress K, Haller MM, Chassin L. The indirect effects of parent psychopathology on offspring affective disorder through difficulty during the leaving home transition. Emerg Adulthood. (2013) 1:196–206. doi: 10.1177/2167696813477089

21. Abraham KM, Stein CH. Emerging adults' perspectives on their relationships with mothers with mental illness: implications for caregiving. Am J Orthopsychiatry (2012) 82:542–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01175.x

22. Hussong AM, Chassin L. Parent alcoholism and the leaving home transition. Dev Psychopathol. (2002) 14:139–57. doi: 10.1017/S0954579402001086

23. Wangensteen T, Bramness JG, Halsa A. Growing up with parental substance use disorder: the struggle with complex emotions, regulation of contact, and lack of professional support. Child Fam Soc Work. (2018) 1–8. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12603

24. Lauritzen C, Reedtz C. Knowledge transfer in the field of parental mental illness: objectives, effective strategies, indicators of success and sustainability. Int J Ment Health Syst. (2015) 9:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-9-6

25. Foster K. ‘You'd think this roller coaster was never going to stop': experiences of adult children of parents with serious mental illness. J Clin Nurs. (2010) 19:3143–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03293.x

26. Kumar SA, Mattanah JF. Parental attachment, romantic competence, relationship satisfaction and psychosocial adjustment in emerging adulthood. Pers Relationsh. (2016) 23:801–17. doi: 10.1111/pere.12161

27. Reupert A, Maybery D. What do we know about families where a parent has a mental illness: a systematic review. Child Youth Serv. (2016) 37:98–111. doi: 10.1080/0145935X.2016.1104037

28. Abraham KM, Stein CH. When mom has a mental illness: role reversal and psychosocial adjustment among emerging adults. J Clin Psychol. (2013) 69:600–15. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21950

29. Foster K, O'Brien L, Korhonen T. Developing resilient children and families where parents have mental illness: a family-focused approach. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2012) 21:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00754.x

30. Reupert AE, Maybery DJ. Stigma and families where a parent has a mental illness. In: Reupert A, Maybery D, Nicholson J, Gopfert M, Seeman M, editors. Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Distressed Parents and Their Families. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2015). p. 51–60.

31. Steer S, Reupert A, Maybery D. Programs for children of parents who have a mental illness: referral and assessment practices. “One size fits all?” Aust Soc Work. (2011) 64:502–14. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2011.594901

32. van Santvoort F, van Doesum KTM, Reupert AE. Parental diagnosis and children's outcomes. In: Reupert A, Maybery D, Nicholson J, Gopfert M, Seeman M, editors. Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Distressed Parents and Their Families. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2015). p. 98–106.

33. van Santvoort F, Hosman CMH, Janssens JMA, van Doesum KTM, Reupert AE, van Loon LMA. The impact of various parental mental disorders on children's diagnoses: a systematic review. Clin Child Family Psych Rev. (2015) 18:281–99. doi: 10.1007/s10567-015-0191-9

34. Reupert A, Cuff R, Maybery D. Helping children understand their parent's mental illness. In: Reupert A, Maybery D, Nicholson J, Gopfert M, Seeman M, editors. Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Distressed Parents and Their Families. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2015). p. 201–9.

35. Seurer L. She Can be a Super Hero, but She Needs Her Day Off. Exploring Discursive Constructions of Motherhood and Depression in Emerging Adults Talk Surround Maternal Depression. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 589, Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU, University of Denver (2015).

36. Beardslee WR, Podorefsky MA. Resilient adolescents whose parents have serious affective and other psychiatric disorders: importance of self-understanding and relationships. Am J Psychiatry (1988) 145:63–9.

37. Reupert A, Maybery D. “Knowledge is power”: educating children about their parent's mental illness. Soc Work Health Care. (2010) 49:630–46. doi: 10.1080/00981380903364791

38. Brown BB. Adolescents' relationships with peers. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Wiley (2004). p. 363–94.

39. Rickwood DJ, Deane FP, Wilson CJ. When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Med J Aust. (2007) 187 (7 Suppl.):35–9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01334.x

40. Davison L, Chinman M, Sells D, Rowe M. Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: a report from the field. Schizophr Bull. (2006) 32:443–50. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj043

41. Grove C, Reupert A, Maybery D. The perspectives of young people of parents with a mental illness regarding preferred interventions and supports. J Child Fam Stud. (2016) 25:3056–65. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0468-8

42. Klodnick VV, Sabella K, Brenner CJ, Krzos IM, Ellison ML, Fagan MC. Perspectives of young emerging adults with serious mental health conditions on vocational peer mentors. J Emot Behav Disord. (2015) 23:226–37. doi: 10.1177/1063426614565052

43. McAdams DP, Olson BD. Personality development: continuity and change over the life course. Annu Rev Psychol. (2010) 61:517–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100507

44. Matar J, Maybery DM, McLean L, Reupert A. Features of an online health prevention and peer support intervention for young people who have a parent with a mental illness: a Delphi study among potential future users. J Med Internet Res. (2018) 20:e10158. doi: 10.2196/10158

45. Haller DM, Sanci LA, Sawyer SM, Patton GC. The identification of young people's emotional distress: a study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. (2009) 59:e61–70. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X419510

46. Reupert A, Cuff R, Drost L, Foster K, van Doesum K, van Santvoort F. Intervention programs for children whose parents have a mental illness: a review. Med J Aust. (2012) 199(3 Suppl.):S18–22. doi: 10.5694/mjao11.11145

47. Siegenhaler E, Munder T, Egger M. Effect of preventive interventions in mentally ill parents on the mental health of the offspring: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry (2012) 51:8–17.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.10.018

48. Marston N, Stavnes K, van Loon L, Drost L, Maybery D, Mosek A, et al. A content analysis of Intervention key elements and assessments (IKEA): what's in the black box in the interventions directed to families where a parent has a mental illness? Child Youth Serv. Rev. (2016) 37:112–28. doi: 10.1080/0145935X.2016.1104041

49. Drost L, Cuijpers P, Schippers GM. Developing an interactive website for adolescents with a mentally ill family members. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry (2010) 16:351–64. doi: 10.1177/1359104510366281

50. Drost L, Schippers L. Online support for children of parents suffering from mental illness: a case study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry (2015) 16:351–64. doi: 10.1177/1359104513496260

51. Elgán TH, Kartengren N, Strandberg AK, Ingemarson M, Hansson H, Zetterlind U, et al. A web-based group course intervention for 15-25 year olds whose parents have substance use problems or mental illness: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health (2016) 16:e1011. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3691-8

52. Woolderink M, Bindels JA, Evers SM, Paulus AT, van Asselt AD, van Schayck OC. An online health prevention for young people with addicted or mentally ill parents: experiences and perspectives of participants and providers from a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2015) 17:e274. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4817

53. Wetterlin F, Mar MY, Neilson E, Werker GR, Krausz M. eMental health experiences and expectations: a survey of youths' web-based resource preferences in Canada. J Med Internet Res. (2014) 16:e293. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3526

54. Burns JM, Davenport TA, Durkin LA, Luscombe GM, Hickie IB. The internet as a setting for mental health service utilisation by young people. Med J Aust. (2010) 92:S22–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39525.442674368

55. O'Dea B, Campbell A. Healthy connections: online social networks and their potential for peer support. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2011) 168:133–40. doi: 10.3233/978-1-60750-791-8-133

56. Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, Zelenko O, Tjondronegoro D, Mani M. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2015) 3:e27. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3422

57. Reupert A, Goodyear M, Eddy K, Alliston C, Mason P, Fudge E. Australian programs and workforce initiatives for children and their families where a parent has a mental illness. Aust E J Adv Mental Health (2009) 8:277–85. doi: 10.5172/jamh.8.3.277

58. Orlowski SK, Lawn S, Venning A, Winsall M, Jones GM, Bigargaddi N. Participatory research as one piece of the puzzle: a systematic review of consumer involvement in design of technology based youth mental health and wellbeing interventions. JMIR Hum Factors (2015) 2:e12. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.4361

59. Schuler D, Namioka A. Participatory Design: Principles and Practices. Hillsdale, NJ: Routledge; Taylor and Francis Group (1993).

60. Maybery D, Ling L, Szakacs E, Reupert A. Children of a parent with a mental illness: perspectives on need. Aust E J Adv Mental Health (2005) 4:78–88. doi: 10.5172/jamh.4.2.78

61. Rapp CA, Goscha RJ. The Strengths Model. A Recover-Oriented Approach to Mental Health Services. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford Press (2012).

62. Eccles J, Appleton JA. Community Programs to Promote Youth Development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press (2002).

63. Young JE, Weinberger AD, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for depression. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders: A Step-by-step Treatment Manual. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press (2001). p. 264–308.

64. Longo DR, Shubert SL, Wright BA, LeMaster J, Williams CD, Clore JN. Health information seeking, receipt, and use in diabetes self-management. Ann Fam Med. (2010) 8:334–40. doi: 10.1370/afm.1115

65. Barry M. Promoting positive mental health: theoretical frameworks for practice. Int J Ment Health Promot. (2001) 3:25–34. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5195-8_16

66. Rogers MA, Lemmen K, Kramer R, Mann J, Chopra V. Internet-delivered health interventions that work: systematic review of meta-analyses and evaluation of website suitability. J Med Internet Res. (2017) 19:e90. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7111

67. Short CE, Rebar AL, Plotnikoff RC, Vandelanotte C. Designing engaging online behaviour change interventions: a proposed model of user engagement. Eur Health Psychol. (2015) 17:32–8. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3786-5

68. Eldridge SM, Lancaster GA, Campbell MJ, Thabane L, Hopewell S, Bond CM. Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: development of a conceptual framework. PLoS ONE (2016) 11:e0150205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150205

69. Tchernegovski P, Reupert A, Maybery D. “Let's Talk about Children”: an evaluation of an e-learning resource for mental health clinicians. Clin Psychol. (2015) 19:49–58. doi: 10.1111/cp.12050

70. Batterham PJ, Sunderland M, Calear AL, Davey CG, Christensen H, Krouskos D. Developing a roadmap for the translation of e-mental health services for depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2015) 49:776–84. doi: 10.1177/0004867415582054

71. Price-Robertson R, Maybery D, Reupert A. Online peer support programs for youth whose parent has a mental illness: service providers' perspectives. Aust Social Work. (in press). doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2018.1515964

72. Folker AP, Mathiasen K, Lauridsen SM, Stenderup E, Dozeman E, Folker MP. Implementing internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for common mental health disorders: a comparative case study of implementation challenges perceived by therapists and managers in five European internet services. Internet Interv. (2018) 11:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.02.001

73. Broad KL, Sandu VK, Sunderji N, Charach A. Youth experiences of transition from child mental health services to adult mental health services: a qualitative thematic synthesis. BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380–91. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1538-1

74. Gibb SJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Burden of psychiatric disorders in young adulthood and life outcomes at age 30. Br J Psychiatry (2010) 197:122–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076570

Keywords: young adults, parents, substance use, mental illness, online intervention

Citation: Reupert A, Bartholomew C, Cuff R, Foster K, Matar J, Maybery DJ and Pettenuzzo L (2019) An Online Intervention to Promote Mental Health and Wellbeing for Young Adults Whose Parents Have Mental Illness and/or Substance Use Problems: Theoretical Basis and Intervention Description. Front. Psychiatry 10:59. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00059

Received: 26 August 2018; Accepted: 25 January 2019;

Published: 15 February 2019.

Edited by:

Giovanni De Girolamo, Centro San Giovanni di Dio Fatebenefratelli (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Arezoo Shajiei, University of Manchester, United KingdomFrancesco Bartoli, Università degli studi di Milano Bicocca, Italy

Copyright © 2019 Reupert, Bartholomew, Cuff, Foster, Matar, Maybery and Pettenuzzo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea Reupert, YW5kcmVhLnJldXBlcnRAbW9uYXNoLmVkdS5hdQ==

Andrea Reupert

Andrea Reupert Catherine Bartholomew2

Catherine Bartholomew2 Jodie Matar

Jodie Matar