- 1Brain and Mind Centre, Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2School of Psychiatry, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4Black Dog Institute, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 5St George Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Objectives: Deciding to disclose a mental illness in the workplace requires thoughtful informed decision making. Decision aids are increasingly used to help people make complex decisions, but need to incorporate relevant factors for the context. This study aimed to identify factors and processes that influence decision making about such disclosure to inform the development of a disclosure decision aid tool for employees in male dominated industries.

Methods: We invited 15 partner organisations in male dominated industries to facilitate the recruitment of employees who either had disclosed a mental health condition in their workplace; or occupied a position to whom employees disclosed to focus groups addressing the aims.

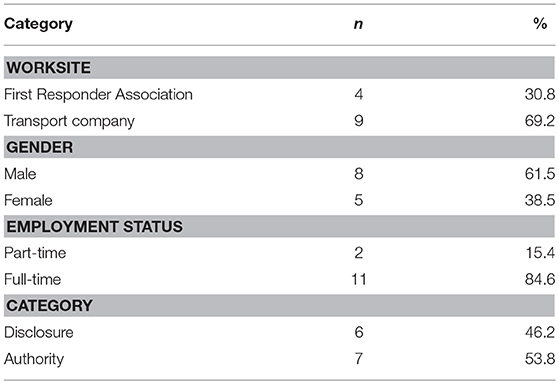

Results: The majority of the organisations had explicit policies that employees must disclose and so were unable to be seen countenancing non-disclosure as an option. Two focus groups were conducted (n = 13) with mainly male (62%), full-time employees (85%), and both disclosed (46%) and authority (54%) groups. Six themes, all barriers, were identified as influencing decision making processes: knowledge about symptoms, and self-discrimination (internal), stigma and discrimination by others, limited managerial support, dissatisfaction with services, and/or a risk of job or financial loss (external).

Conclusion: Decisions to disclose mental health conditions, even by those who had done so, appear driven entirely by consideration of negative aspects. This suggests that anti-discrimination policy, legislation, awareness campaigns, and manager training have yet to change negative perceptions, and that any decision aid tool needs to incorporate counterfactual positive aspects that appear not to be an important consideration in such male dominated workplaces. There is a disconnect between organisational policies favouring disclosure and employees favouring non-disclosure that has caused tension within the organisational culture. Decision aid tools may assist employees with an active disclosure without waiting for an event to occur, giving the control of the decision back to the employee.

Introduction

Despite the high prevalence, mental illness in the workplace is commonly misunderstood and under supported (1), even though employment plays an important role in maintaining psychological health, and for men, paid work is associated with increased levels of personal growth (2).

In Australia, male dominated industries are defined as workplaces where more than 70% of the working population are males (3) and in Australia male dominated industries tend to have higher than average rates of common mental disorders with the mental disorder rates in agriculture, construction, mining, and utilities ranging between 20 and 24% (4).

When considering workplace compensation claims made in Australia between 2008 and 2011 the highest risk male occupations for metal stress are transport officers, police officers and ambulance officers/paramedics (5).

People in employment often face complexities in managing mental illness as a result of discrimination or stigma. This is particularly true when (re)entering the workforce after being acutely ill or trying to continue working despite an illness, with almost 70% of workers reporting anticipated discrimination when finding work or trying to manage their symptoms at work (6).

Discrimination, both anticipated and experienced, is the most frequently identified barrier to disclosure of mental health conditions in the workplace (7). Recent studies have shown that employers were less likely to hire someone who discloses their mental illness during recruitment, even more so than people with permanent physical disabilities (8, 9). In a workplace context, stigma and discrimination are important factors that hinder those with a mental health condition in seeking employment, staying employed, or gaining a promotion (8, 10). Discrimination and bullying can vary between industries with male dominated industries reporting experiences of discrimination associated with reduced mental health [(11), paper under submission] and female dominated industries more often reporting bullying (12).

For individuals making decisions around their disclosure important factors to consider are the organisational policies around disclosure and if these policies align with that of the individual. Organisational policies promote disclosure and managers report preferring disclosure, even though they acknowledge that it would be a significant risk to employ those with a disclosed mental illness (13). A recent European longitudinal study on attitudes towards disclosure in employers showed that 42% of employers agreed that mental illness policy was set up primarily to protect the organisation from litigation (14). However, fear of perceived public stigma has lead employees to default to a position of non-disclosure (15).

Many countries have enacted legislation to tackle such discrimination, usually framed in a disability context. The Australia Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (16) defines “discrimination” broadly, and includes direct and indirect discrimination. The Act makes it unlawful to discriminate against, harass or victimise people with disabilities, including those with mental health conditions. It also makes it clear that an employer's reluctance to hire, or failure to make reasonable adjustments for a worker with a mental health condition are discriminationatory practices. Organisational practices and commonly accepted behaviours occur and remain unchallenged, despite falling within the legal definition of indirect discrimination.

In order to address gaps in knowledge regarding mental health in the workplace, a number of workplace manager interventions have been implemented with an emphasis on awareness training and skills development. A recent meta-analysis indicated that mental health training appears to increase managers' understanding of issues, their role and responsibilities, attitudes, and importantly, behaviours when addressing mental health concerns (17). Workplace anti-stigma interventions follow a similar process to manager training by targeting knowledge, attitudes and behaviours. A recent systematic review reports that workplace anti-stigma interventions can be particularly effective in changing employees' knowledge of mental disorders, as well as helping change behaviour of colleagues in the workplace (18).

Despite interventions aimed at managers and colleagues, employees are still reluctant to disclose. A recent Australian survey showed that 41% of those who had taken unplanned leave for their mental illness did not disclose the true reason to their employer, and only 26% disclosed their mental illness (19). Research on disclosure of mental health conditions in a workplace setting has typically focused on those with more severe mental illness (20) with interventions focusing on those that are unemployed to help facilitate return to work (21). However, little attention has been paid to helping employees make the decision to disclose mental health issues in the workplace.

For people currently in employment, deciding to disclose a mental illness is often complex, and requires thoughtful decision making to ensure personal, legal and employment risks are best managed. Decision aid tools offer a way to support people with these complexities. They can encourage thoughtful deliberation in making specific and deliberate choices amongst two or more options, and have commonly been used in decision making regarding medical treatment options (22). The recent success of the CORAL study (21), which used a paper-based decision aid tool for people with a severe mental illness in secondary care services seeking employment showed that, in this setting, the decision aid had the capacity to reduce decisional conflict. Those using the tool had an increased likelihood of obtaining employment regardless of the decision made, indicating the importance of making, and being comfortable with an informed decision.

As part of the future development of a web-based decision aid tool to support deliberations of disclosure of mental health conditions in the workplace we aim to explore factors currently influencing decision making about disclosure with two key groups, employees who have disclosed and supervisors involved in the sequelae to disclosure.

Methods

Design

This qualitative focus group study aimed to inform the design of a tool to help employees in male dominated industries decide whether to disclose or not, and describe factors that influence the decision process.

We aimed to recruit participants that: (a) have a mental health condition and have disclosed; or (b) occupy a position of authority, i.e., supervisors who's employees with a mental health condition have disclosed to. This participant selection strategy offered insights into perceptions among those who had experience in decisions regarding disclosure, as well as those who managed disclosures. This qualitative strategy allowed access to a variety of perspectives and experiences, and maximised our ability to identify challenges in decision making and develop an effective, appropriate intervention by being able to open dialogue and expand on responses when clarification is needed.

Sample/Recruitment

As a part of a large Australian based research collaboration (well@work) 15 industry partners involved were invited to participate. Participants were recruited from a First Responder Association and a transport company in New South Wales, Australia. Twenty-Three employees and supervisors were invited through an email sent out via their workplace administration team. Interested participants were directed by the administration team at each site to attend the focus groups. The research team had no contact with participants until the day the focus groups were conducted. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Sydney.

Procedures

After obtaining informed consent, each participant was asked about their role, and if they wished to disclose their mental illness. Those who receive disclosures were considered the “authority group” and those who have disclosed were considered the “disclosure group.” The focus groups were conducted at organisational sites and lasted between 77 and 93 min.

Data Collection

The focus group facilitator (ES) was trained by (RR) an experienced workplace focus group researcher. The facilitator (ES) and the principal investigator (NG) constructed the focus group discussion guide. The questions were designed to assess the process and content of the web-based decision aid tool, and identify factors influencing and consequences to decision making about disclosure. A semi-structured approach was adapted to ensure that the facilitator could follow-up on any important remarks or seek clarification of understanding. Focus groups were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and accuracy was verified. The transcriptions were de-identified and given a participant identification number as a pseudonym to protect anonymity. Only the main researcher ES had access to the participants identification. After the focus group, the facilitator and trainer met to review the techniques used in facilitation. After both of the focus groups the facilitator met with the principal investigator to debrief. Transcripts were analysed as soon as possible after each interview. After two groups, participants were repeating similar ideas about the design of the tool, prompting a decision that saturation had been reached.

Data Analysis

Two authors (ES & RE) independently coded the typed transcriptions of the focus groups. NVivo 11 was used to organise the data. The investigators used the Framework Analysis Method (23) to analyse the data (24). This method allows for the structured identification of commonalities and differences in qualitative data, and helps to draw descriptive and explanatory conclusions clustered around common themes. It is especially useful when multiple researchers are coding the same dataset, by providing an open, critical and flexible approach to allow for rigorous step-by-step qualitative analysis (25). This method uses five stages, the first stage familiarisation, began when investigators started transcribing the data. A thematic framework, was then identified by two investigators and coded each transcript separately. The coding involved an iterative process as the codes were refined, while discrepancies were resolved by a third investigator (NG). Next, key themes and direct quotes were indexed to demonstrate the richness of the themes. Subthemes within these key themes provided an in-depth approach to identifying the factors influencing decision making. In the fourth stage, themes were charted (see Table 2) as to easily identify the data and trace back to its original source. Each theme was described to reflect key characteristics of the decision making process.

Results

Participants

Of the 15 industry collaboration partners invited, only two of the industries would consider facilitating a tool that promotes both disclosure and non-disclosure. All of those who gave a reason stated that they had explicit employment and human resource policies that employees must disclose mental illness. These included both private and non-government organisations.

The two focus group we were able to conduct consisted of 13 participants (57% response rate), employed within the two organisations. The majority were from a Transport Company (69%), male (62%), and had full-time employment (85%) (Table 1). Six employees had experience disclosing their own mental health condition (employee 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) and seven had a supervisory role and had been disclosed to (supervisor 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

Decision Making Influences

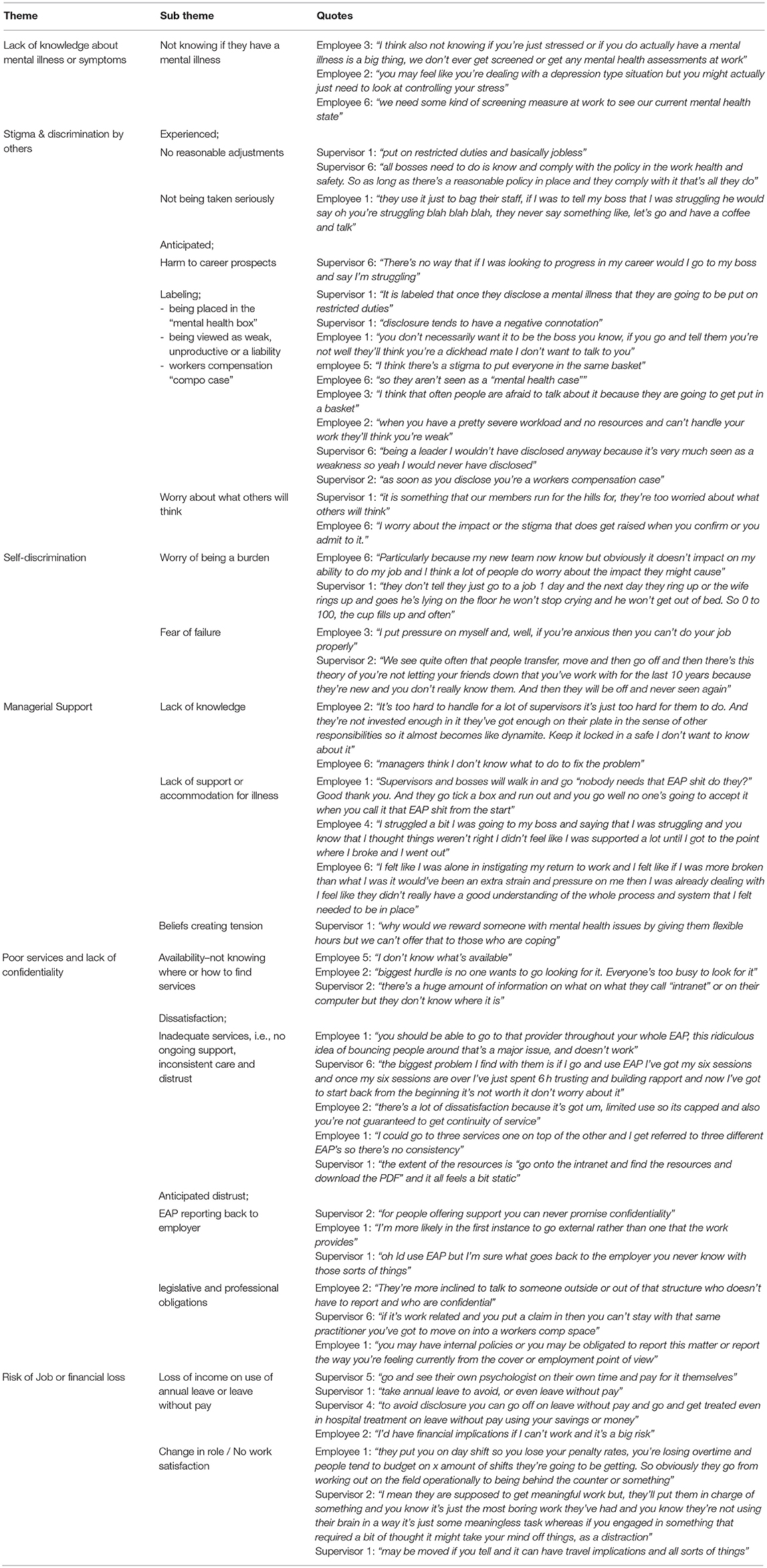

Participants reported factors that influenced decision making about disclosing a mental health condition at work. Six key themes emerged, each with several subthemes, including: internal factors (lack of knowledge about symptoms of mental illnesses, self-discrimination) and external factors (stigma and discrimination by others, a lack of managerial support, dissatisfaction and distrust of the current services and a risk of job or financial loss) (Table 2).

Table 2. Identified themes of factors that influence decision making in employees with a mental health condition.

Internal Influencing Factors

Lack of Knowledge

Some participants, particularly those that had not been previously diagnosed, reported a lack of understanding the severity of their symptoms and not being sure if they even had a mental health condition. Thus, they were unsure if they should seek help. Employee 6 suggested: “we need some kind of screening measure at work to see our current mental health state.” A screening tool could assist with assessing their current mental health and confirm if they needed to seek assistance.

Self-discrimination

The idea that disclosing a mental health condition would create a burden on others was often cited as consideration in decision making. For instance, Employee 3 stated: “I put pressure on myself and, well, if you're anxious then you can't do your job properly.” When participants became overwhelmed with their workload, they reported feelings of failure for not performing to the standard that they expect of themselves. In situations where individuals are feeling pressured and overwhelmed, symptoms of ill-health can reduce decision making capacity and interventions may be useful in assisting the decision-making process in helping to reduce the burden of making a decision.

Another participant reported employees working while they were suffering from a mental health condition and waiting until “the cup fills up” (Supervisor 1). Pushing through the symptoms was important so as not to “let their friends down at work” (Supervisor 2). However, for some this strategy resulted in becoming so ill that they needed to take unplanned leave.

External Influencing Factors

Stigma and Discrimination by Others

Stigma and discrimination by others was the greatest influencing factor to making decisions of disclosure. Subthemes related to stigma were also identified. The first was “experienced discrimination,” where no reasonable adjustments had been offered and employees disclosures were not taken seriously. Mental health conditions were stigmatised in the workplace, particularly in this setting for first responders. Participants worried about being labelled as a “mental health case” (Employee 6), and generalisations being made about their abilities. Across a variety of mental health presentations there was an ongoing worry about being placed “all in the same basket” (Employee 5) or being constituted as disabled even when they have their symptoms “currently under control” (Employee 2). Participants also reported feelings of those with a mental illness as being constituted as unproductive, a liability or seen as weak, and the implication of such constitutions would result in non-disclosure “There's no way that if I was looking to progress in my career would I go to my boss and say I'm struggling” (Supervisor 6). Anticipated discrimination had the largest number of subthemes suggesting it is the most common consideration in decisions to disclose.

Lack of Managerial Support

Several participants said they were not supported by their managers during their disclosures because they did not have adequate knowledge of mental illnesses, and already had “too much on their plates” (Employee 2) to provide the proper support or empathy needed. These beliefs from both the employees and supervisors led to tension with where their responsibilities lie, often only providing support that they are legally obliged to. Participants conferred that managers did not provide adequate accommodations or support for mental illnesses at work. At times, participants felt belittled or left to fend for themselves when returning to work. One participant, who has been a manager, reported concerns about providing flexibility and support to those who have a mental illness rewards those who were not coping when they cannot provide the same rewards to employees who were coping.

Employee Assistance Program (EAP) Services

There was a clear dissatisfaction with, and distrust of, current EAP services. First, participants reported not knowing what was available or where to find services, and feeling overwhelmed about the amount of information to consider when they're already unwell. They questioned the confidentiality of in-person workplace EAP's, and believed EAP support officers were representing both them and the organisation. This mistrust related to legal obligations, particularly in first responders, where staff are required to report their colleagues, if they disclosed mental health conditions. In many ways, confidentiality is limited in their workplace by legislation and professional obligations.

Second, of the participants that had used an EAP previously, most reported the inadequacy of the available programs. Participants identified due to limited sessions, for ongoing treatment, they would need to restart with new EAP officer or be moved off into workers compensation. Employee 1 described: “I could go to three services one on top of the other and I get referred to three different EAP's so there's no consistency.” Participants felt they were “bouncing” around from one service provider to the next, without gaining any relevant tools for recovery.

Risk of Job or Financial Loss

Lastly, participants reported financial and job risks that must be considered when deciding whether or not to disclose. If they disclosed their mental illness, a change in role was so drastically different from their usual one that they were reported as “boring” or had “no meaning”—Supervisor 2. For first responders, reasonable adjustments were often not available at their workplace and their only option was to relocate. Finally, participants reported using their annual or sick leave and paying for services out of their own pocket to avoid disclosure at work, returning to work only when they felt better. Importantly, they did this even when the onset or exacerbation of the mental illness occurred in or because of the workplace environment.

Positive Experiences of Disclosure

A specific question was asked in both focus groups to identify any positive experiences with, and facilitators of disclosure. Only one responder reported a positive experience, but could not identify how this was enabled. Employee 6: “I did speak to my manager about it and the triggers. My work has been really good since. We have an EAP service and it was great to experience that service. I think if I didn't have that support those triggers at work would happen a lot more and be more frequent.”

Consequences of the Factors Influencing Decision Making, and Non-disclosure

The identified factors influencing decision making about disclosure had a number of behavioural consequences. First, attitudes towards disclosure are seemingly that of, “it's ok for others to disclose but not for me” (Supervisor 6). In the authority group, the dissonance between believing that they were supportive but their actions suggesting an unsupportive environment created a culture favouring non-disclosure, resulting in mental health issues rarely being disclosed unless they can no longer be hidden or until seeking help is too late. Even managers themselves reported that they would never disclose if they were considering career progression.

Managers' negative attitudes towards those that report a mental illness at work often lead to a lack of preparation to support the mental health of their employees despite employees often becoming ill or symptoms worsening on duty. Managers responses to mental illnesses at work become paternalistic and protective and the organisations' responsibilities, doing only what is required by law or internal policies and procedures. These behaviours point to a context of little flexibility and support for workers in general creating tensions with a belief that providing flexibility and support “rewards” those that are not coping because of their mental illness. Managers felt torn that they cannot provide the same accommodations for those that are coping well with work demands “why would we reward someone with mental health issues by giving them flexible hours but we can't offer that to those who are coping” (Supervisor 1).

This managerial discrimination has led to the practice of “reasonable adjustments” becoming simply restricted duties that have a lack of autonomy, are mundane and are not challenging, resulting in poor job satisfaction, poor job security, negative financial implications, isolation and or dislocation, a decreased self-worth in a work context, lack of opportunity for advancement. Employees who have disclosed are left feeling that they need to work harder than others to prove one's worth “they are supposed to get meaningful work but, they'll be put in charge of something and you know it's just the most boring work” (Supervisor 2).

Participants reported some consequences of non-disclosure, if an employee does not disclose their mental illness, and there is an incident in their workplace that places themselves, a colleague or a member of the public in harm's way they or their organisation may face legal action. Particularly if they are taking medications for their mental illness that have not been disclosed and may be present in a toxicology report that may have impaired their judgement during the incident. It was also reported that workers may not take their medications that were prescribed in order to avoid disclosure.

Employee 1: “If someone was involved in a critical incident or something the first thing they're asked is if they take any medications, and if they start listing down different psychological medications and haven't said anything before people may say they were impaired, or affected by it and they shouldn't have been working.”

Employee 2: “people just don't take their medications that are prescribed to them because if it's on the banned list or will show up in a tox report you're forced to disclose it. But if you don't take it then you don't have to disclose it.”

Discussion

Despite only 25% of those with a mental health condition disclosing their illness at work (19), few studies have investigated the factors which influence decision-making around disclosure. This present study explores these factors among first responders and a transport organisation who either have previously disclosed or were responders to such decision processes. This study identified six key themes, all negative, of internal and external factors influencing and consequences of decision making regarding disclosure. When considering all factors together these male dominated workplaces are characterised by a culture of fear around disclosure. Managers appear underprepared to deal with the impacts of disclosure, and there is a lack of organisational systems in place to deal with mental health issues amongst employees.

The prevalence of explicit disclosure policies led to the majority of our partners declining to be involved in research that consider an option of non-disclosure. A recent qualitative study in Canada suggested that organisational policies should not focus on a stance of disclosure as the only option, the focus should be placed on creating an environment where employees feel comfortable and safe to disclose (15).

This study, similarly to Toth and Dewa (15), identified that employees start from a default position of non-disclosure, and identified that employees only move to a position of disclosure once they feel as though an event occurs such as “their cup fills up.” This dissonance between organisational policies taking a hard stance on disclosure and employees defaulting to the other option of non-disclosure has created tension and created a culture of fear around disclosure.

What was striking was that despite the researchers adopting a neutral approach and asking a specific question to prompt negative or positive experiences to whether disclosure was desirable or not, only one person considered the potential positive aspects of doing so. The single incident of a positive experience in disclosing mental illness suggests a failure of the extensive government initiatives aimed at demonstrating the possibilities of workplace accommodations, and shows dissonance between employers preferring prospective employees to disclose at the outset (26) even though they may not be willing or have the capacity to provide support or adjustments, or even be willing to hire those with a mental illness in the first place (27). Decision aids need to specifically incorporate these factors into the considerations to balance the entrenched barriers. The provision of training for managers and colleagues is not enough to address the barriers, as low rates suggest that many of those living with a mental illness are still not disclosing (19).

Self-stigma and internalisation of discrimination reduces the capacity to make decisions (28). Anticipating discrimination, worry about being a burden, being judged as weak, or being denied a promotion also influences decision making about disclosure supporting previous research that suggests those that have a mental illness often decline to seek help to avoid being stigmatised (29). Poor knowledge of potential mental illness, particularly discriminating early symptoms from daily stress (30) would be present in those not yet at a stage of decision making who may be unaware of options available to prevent deterioration, which might require disclosure. A recent study found that better knowledge, and a positive self-attitude can predict stronger intentions to disclose (31).

A number of external factors to decisions about disclosure were also identified. Some participants had experienced discrimination by others when disclosing in the past; particularly common were lack of support or preparedness of managers to provide reasonable work adjustments after disclosures. Consequences of this included a negative culture around mental illness in the workplace, which, as shown in other studies, seemingly reduces the motivation for employees to disclose (32, 33). Which we know may be detrimental in male dominated industries as men are more likely to disclose than women when there is a supportive environment (34).

Secondly, some employees anticipated discrimination or worried about being seen as weak or incompetent. This anticipated reaction is based on experience and substantiated by research, with previous studies showing that employers view people with mental illness as lacking competence to meet work demands (27, 35).

Both of these first two themes identified could have serious impacts on male dominated industries in particular, as two recent systematic reviews examining the characteristics and risk factors that are associated with common mental disorders in male dominated industries identified that an unsupportive environment, job demands and job overload are associated with psychological distress and are risk factors for depression and anxiety (36, 37).

In contrast to previous research (38), this study identified a clear dissatisfaction and distrust with current EAP services. Participants reported not knowing what was available, found it difficult to find what they needed when they were feeling unwell and overburdened. The inadequacy of the available EAP programs were also reported with complaints about session lengths, inconsistency of care and not gaining any relevant tools for recovery. Confidentiality was another factor identified that influenced decision making, participants had a general belief that EAP officers report details from the sessions to their employers. Confidentiality concerns with EAP services have been previously documented (39), however, this study shows how a lack of anticipated confidentiality can lead to decisional conflict around disclosure. Confidentiality may be limited within colleagues as some legislation and professional obligations require colleagues to report to management if someone has disclosed to them, this may be an issue specific to the Australian first responders group as they have particular safety concerns related to their professional responsibilities.

The final factors that influence decision making identified were financial implications and risk of job loss or role change. A number of participants both from the authority and disclosure groups reported either personal or second hand accounts of seeking help outside of the workplace to avoid disclosure and its consequences, often using up their holiday and sick leave and accruing personal expenses whether the illness originated or was exasperated in the workplace. Other participants also reported worry over the work that will be available to them; work via reasonable adjustments are either mundane and require relocation to have reasonable work available that has been previously shown to increase the prevalence of isolation and reduce communication and team relationships (40).

Strengths and Limitations

The findings of this study were unique to this particular population and the analysis has been undertaken with the aim to develop a decision making support aid. The theoretical perspectives are oriented towards supporting individuals deciding whether or not to disclose a mental health issue or managing a disclosure, and achieving equity for persons with mental health issues in the workplace. Second, the participants in the focus groups were people who volunteered to participate in a qualitative research, from a group that already have experience with disclosing a mental illness at work. Therefore, this group was likely to be highly motivated to participate in research and may have been different from those who did not wish to share their views, they may have less self-stigma and be able to hold back less with their responses as they had already disclosed. Lastly, this sample may not be representative or generalised to other occupations or industries as participants were recruited from two industries with specific needs, in particular the first responders had unique challenges given legislative requirements and obligations which are specific to only emergency/medical services (41).

Conclusion

In male dominated workplaces decisions to disclose mental ill-health, even by those who had done so or who were influential for consequences, appeared driven entirely by consideration of barriers to disclosure. This suggests that anti-discrimination policy, legislation, awareness campaigns, celebrity stories, and manager training have yet to change perceptions that disclosure is negative, and have not been able to shift the culture of stigma that looms over mental health issues. There seems to be a clear disconnect between organisational policies favouring disclosure and employees favouring non-disclosure that has caused tension within the organisational culture and a fear around disclosure. Further attention is needed to encourage a more positive and productive approach in supporting employees in the workplace. Any decision aid tool needs to incorporate counterfactual and potentially positive aspects that are not yet widely considered in decisions about disclosing mental health issues in the workplace. Such content could begin to shift cultures of stigma, as well as support people to be properly informed and feel empowered and that they are making the correct decision for their situation.

Author Contributions

ES, IC, SH, and NG contributed to the design and conduct of the study. RR and ES facilitated the focus groups. RE and ES coded the data. ES, RE, and NG had full access to all of the data and completed the analysis. All authors reviewed manuscript drafts and approved the final version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge expert opinion from Dr. Claire Henderson. This study was developed in partnership with beyondblue with donations from the Movember Foundation.

References

1. SANE Australia. Sane Research Bulletin 14: Working Life And Mental Illness. Melbourne: SANE Australia (2011).

2. Ryff CD. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. (2014) 83:10–28. doi: 10.1159/000353263

3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification. Canberra, ACT: Australian Bureau of Statistics (2008).

4. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results, 2007. Sydney, NSW: Australian Bureau of Statistics (2008).

5. Safework Australia. The Incidence of Accepted Worker' Compensation Claims for Mental Stress In Australia. Canberra, ACT: Safe Work Australia (2013).

6. Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N, Leese M, Group IS. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet (2009) 373:408–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61817-6

7. Brohan E, Evans-Lacko S, Henderson C, Murray J, Slade M, Thornicroft G. Disclosure of a mental health problem in the employment context: qualitative study of beliefs and experiences. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2014) 23:289–300. doi: 10.1017/S2045796013000310

8. Brohan E, Henderson C, Wheat K, Malcolm E, Clement S, Barley EA, et al. Systematic review of beliefs, behaviours and influencing factors associated with disclosure of a mental health problem in the workplace. BMC Psychiatry (2012) 12:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-11

9. Wheat K, Brohan E, Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Mental illness and the workplace: conceal or reveal? J R Soc Med. (2010) 103:83–6. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.090317

10. Mendel R, Kissling W, Reichhart T, Buhner M, Hamann J. Managers' reactions towards employees' disclosure of psychiatric or somatic diagnoses. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2015) 24:146–9. doi: 10.1017/S2045796013000711

11. Stratton E, Player MJ, Choi I, Dahlheimer A, Harvey SB, Glozier N. Discrimination and Bullying in a Male-dominated Australian Workforce. (2018).

12. Verkuil B, Atasayi S, Molendijk ML. Workplace bullying and mental health: a meta-analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal data. PLoS ONE (2015) 10:E0135225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135225

13. Brohan E, Henderson C, Little K, Thornicroft G. Employees with mental health problems: survey Of U.K. employers' knowledge, attitudes and workplace practices. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. (2010) 19:326–32. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X0000066X

14. Henderson C, Williams P, Little K, Thornicroft G. Mental health problems in the workplace: changes in employers' knowledge, attitudes and practices in England 2006-2010. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. (2013) 55:S70–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112938

15. Toth KE, Dewa CS. Employee decision-making about disclosure of a mental disorder at work. J Occup Rehabil. (2014) 24:732–46. doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9504-y

16. Australian Government. Disability Discrimination Act: 1992 [Online]. (1992). Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C2004A04426 (Accessed March 19, 2018).

17. Gayed A, Milligan-Saville JS, Nicholas J, Bryan BT, Lamontagne AD, Milner A, et al. Effectiveness of training workplace managers to understand and support the mental health needs of employees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. (2018) 75:462–70. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2017-104789

18. Hanisch SE, Twomey CD, Szeto AC, Birner UW, Nowak D, Sabariego C. The effectiveness of interventions targeting the stigma of mental illness at the workplace: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry (2016) 16:1. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0706-4

19. SANE Australia. Research Bulletin 18 The Impact Of Depression At Work. Melbourne: SANE Australia (2014).

20. Boyce M, Secker J, Johnson R, Floyd M, Grove B, Schneider J, et al. Mental health service users' experiences of returning to paid employment. Disabil Soc. (2008) 23:77–88. doi: 10.1080/09687590701725757

21. Henderson C, Brohan E, Clement S, Williams P, Lassman F, Schauman O, et al. Decision aid on disclosure of mental health status to an employer: feasibility and outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry (2013) 203:350–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128470

22. Williams RM, Davis KM, Luta G, Edmond SN, Dorfman CS, Schwartz MD, et al. Fostering informed decisions: a randomized controlled trial assessing the impact of a decision aid among men registered to undergo mass screening for prostate cancer. Patient Educ Couns. (2013) 91:329–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.12.013

23. Ritchie JSL, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research by Jane Ritchie And Liz Spencer. In: Bryman A. and Burgess RG, editors. Analyzing Qualitative Data. London; New York, NY: Routledge. (1994). 173–94. doi: 10.4324/9780203413081_chapter_9

24. Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide For Applied Research, 4th Edn (2008). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

25. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2013) 13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

26. Little K, Henderson C, Brohan E, Thornicroft G. Employers' attitudes to people with mental health problems in the workplace in Britain: changes between 2006 and 2009. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2011) 20:73–81. doi: 10.1017/S204579601100014X

27. Brohan E, Henderson C, Slade M, Thornicroft G. Development and preliminary evaluation of a decision aid for disclosure of mental illness to employers. Patient Educ Couns. (2014) 94:238–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.008

28. Lassman F, Henderson RC, Dockery L, Clement S, Murray J, Bonnington O, et al. How does a decision aid help people decide whether to disclose a mental health problem to employers? Qual Inter Study J Occup Rehabil. (2015) 25:403–11. doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9550-5

29. Schomerus G, Angermeyer MC. Stigma and its impact on help-seeking for mental disorders: what do we know? Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. (2008) 17:31–7. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X00002669

30. Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. The public's ability to recognize mental disorders and their beliefs about treatment: changes in Australia over 8 years. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2006) 40:36–41. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01738.x

31. Rusch N, Evans-Lacko SE, Henderson C, Flach C, Thornicroft G. Knowledge and attitudes as predictors of intentions to seek help for and disclose a mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. (2011) 62:675–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.6.pss6206_0675

32. Garcia JA, Crocker J. Reasons for disclosing depression matter: the consequences of having egosystem and ecosystem goals. Soc Sci Med. (2008) 67:453–62. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.016

33. Kelly AE, Yip JJ. Is keeping a secret or being a secretive person linked to psychological symptoms? J Pers. (2006) 74:1349–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00413.x

34. Macdonald-Wilson KL, Russinova Z, Rogers ES, Lin CH, Ferguson T, Dong S, et al. Disclosure of mental health disabilities in the workplace. In: Schultz IZ and Rogers ES, editors. Work Accommodation And Retention In Mental Health. New York, NY: Springer New York (2011).

35. Krupa T, Kirsh B, Cockburn L, Gewurtz R. Understanding the stigma of mental illness in employment. Work (2009) 33:413–25. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2009-0890

36. Considine R, Tynan R, James C, Wiggers J, Lewin T, Inder K, et al. The contribution of individual, social and work characteristics to employee mental health in a coal mining industry population. PLoS ONE (2017) 12:E0168445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168445

37. Battams S, Roche AM, Fischer JA, Lee NK, Cameron J, Kostadinov V. Workplace risk factors for anxiety and depression in male-dominated industries: a systematic review. Health Psychol Behav Med. (2014) 2:983–1008. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2014.954579

38. Csiernik R. The glass is filling: an examination of employee assistance program evaluations in the first decade of the new millennium. J Workplace Behav Health (2011) 26:334–55. doi: 10.1080/15555240.2011.618438

39. Merrick EL, Hodgkin D, Hiatt D, Horgan CM, Mccann B. Eap service use in a managed behavioral health care organization: from the employee perspective. J Workplace Behav Health (2011) 26:85–96. doi: 10.1080/15555240.2011.573751

40. Bellagamba G, Michel L, Alcaraz-Mor R, Giovannetti L, Merigot L, Lagouanelle MC, et al. The relocation of a health care department's impact on staff: a cross-sectional survey. J Occup Environ Med. (2016) 58:364–9. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000664

Keywords: male-dominated, disclosure, mental illness, employee, decision aid tool

Citation: Stratton E, Einboden R, Ryan R, Choi I, Harvey SB and Glozier N (2018) Deciding to Disclose a Mental Health Condition in Male Dominated Workplaces; A Focus-Group Study. Front. Psychiatry 9:684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00684

Received: 03 September 2018; Accepted: 26 November 2018;

Published: 19 December 2018.

Edited by:

Sebastian von Peter, Medizinische Hochschule Brandenburg Theodor Fontane, GermanyReviewed by:

Julian Schwarz, Medizinische Hochschule Brandenburg Theodor Fontane, GermanyOttar Ness, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway

Copyright © 2018 Stratton, Einboden, Ryan, Choi, Harvey and Glozier. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth Stratton, ZW9kZzUxOTJAdW5pLnN5ZG5leS5lZHUuYXU=

Elizabeth Stratton

Elizabeth Stratton Rochelle Einboden

Rochelle Einboden Rose Ryan1

Rose Ryan1