- 1Department of Psychology, University of California, Merced, Merced, CA, United States

- 2Center for Excellence in Biopsychosocial Approaches to Health, Chapman University, Orange, CA, United States

- 3Department of Health Sciences, Chapman University, Orange, CA, United States

- 4Department of Psychology, Palo Alto University, Palo Alto, CA, United States

Background: Postpartum depression (PPD) poses a major global public health challenge. PPD is the most common complication associated with childbirth and exerts harmful effects on children. Although hundreds of PPD studies have been published, we lack accurate global or national PPD prevalence estimates and have no clear account of why PPD appears to vary so dramatically between nations. Accordingly, we conducted a meta-analysis to estimate the global and national prevalence of PPD and a meta-regression to identify economic, health, social, or policy factors associated with national PPD prevalence.

Methods: We conducted a systematic review of all papers reporting PPD prevalence using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. PPD prevalence and methods were extracted from each study. Random effects meta-analysis was used to estimate global and national PPD prevalence. To test for country level predictors, we drew on data from UNICEF, WHO, and the World Bank. Random effects meta-regression was used to test national predictors of PPD prevalence.

Findings: 291 studies of 296284 women from 56 countries were identified. The global pooled prevalence of PPD was 17.7% (95% confidence interval: 16.6–18.8%), with significant heterogeneity across nations (Q = 16,823, p = 0.000, I2 = 98%), ranging from 3% (2–5%) in Singapore to 38% (35–41%) in Chile. Nations with significantly higher rates of income inequality (R2 = 41%), maternal mortality (R2 = 19%), infant mortality (R2 = 16%), or women of childbearing age working ≥40 h a week (R2 = 31%) have higher rates of PPD. Together, these factors explain 73% of the national variation in PPD prevalence.

Interpretation: The global prevalence of PPD is greater than previously thought and varies dramatically by nation. Disparities in wealth inequality and maternal-child-health factors explain much of the national variation in PPD prevalence.

Introduction

Maternal mental health problems pose major public health challenges for societies across the globe. For example, psychiatric illness (often associated with suicidality) is one of the leading causes of maternal death in the UK (1), as well as a leading killer of women of childbearing age in both India and China (2). The most common psychiatric malady following childbirth is postpartum depression (PPD), a devastating mental illness that can impair maternal behaviors (3, 4) and adversely affect the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral development of children (5).

Three decades of interdisciplinary research have produced thousands of studies investigating the characteristics, measurement, consequences, treatment, and predictors of PPD. Despite these efforts, the global prevalence of PPD remains unknown. The widely cited PPD prevalence rate of 13% ascertained two-decades ago is based on a meta-analysis of overwhelmingly Western samples (6) and most likely do not reflect the incidence of PPD in the majority of the world’s population. For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis that focused exclusively on low- and lower-middle income countries found a higher incidence of postpartum mental health disorders (7). However, this review, too, did not include wealthy nations for purposes of comparison, leaving open the possibility that the apparently inflated incidence of PPD in the developing world was an artifact of the different study methods employed in those societies (7). For example, low-income countries are more likely than high-income countries to rely on self-report PPD measures (rather than interviews) in the first weeks after birth (7), and we know that self-reported PPD measures taken earlier postpartum tend to yield higher PPD prevalence than interview tools given later. Accordingly, a meta-analysis comparing PPD prevalence, and taking into account divergent research methods used in high-, medium-, and low-income countries, is required to determine the true global and cross-national variation of PPD prevalence.

Further, to our knowledge, no prior large-scale meta-analysis has considered potential cross-national differences in PPD, despite qualitative evidence suggesting that PPD may vary dramatically from nation to nation even between nations of comparable economic standing (8, 9). Reliable national PPD estimates could help to illumine particular economic, health, and policy factors that inflate or reduce PPD prevalence, thereby informing prevention efforts. Further, generating reliable national estimates of PPD could aid policy-makers in decisions about where to allocate limited resources, and alert global health agencies to direct aid to those countries most impacted.

Motivated by the potential health benefits of filling these knowledge gaps, we conducted the largest meta-analysis and meta-regression to date of global PPD prevalence. The present meta-analysis contains four times more studies, 22 times more women, and data from an additional 36 nations compared to the largest previous meta-analysis of PPD prevalence (6). We aimed to estimate PPD prevalence both globally and by nation and to explore whether divergent methodologies or disparities in health, economic, policy, or sociodemographic factors explain cross-national differences in PPD.

Methods

This study was comprised of three phases: (1) conducting a systematic review in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (10), (2) performing a meta-analyses to estimate PPD prevalence both globally and for each nation, and (3) using meta-regression to investigate whether methodological, economic, health, and/or policy factors predict cross-national variation in PPD.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

To identify potentially eligible articles, we searched PubMed, PsychINFO, and CINAHL using a combination of the following MeSH terms in the abstract: (“postpartum depression” or “postnatal depression”) and (“incidence” or “prevalence”). In addition, we used the measures and instruments qualifier “edinburgh postnatal depression scale.” We further limited our search by only including studies of human females published in English between 1985 (just before the EPDS scale was published) and 2015. The exact Boolean searches used for each database are provided in Section “Boolean Search Information” in the Appendix. Additionally, we reviewed three previously published comprehensive literature reviews of PPD prevalence (7–9).

To be eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis, studies were required to report PPD prevalence using the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (a 10-item self-report, widely used tool specially designed to measure PPD; EPDS) (11) on samples of mothers ≤1 year postpartum with a sample size >20. We chose to include studies conducted anytime in the first year postpartum because this is a convention used in the empirical literature (12) [despite the fact that the American Psychological Association categorizes PPD as occurring anytime in the first 4 weeks postpartum (13), whereas PPD is defined as depression occurring anytime within the first 6 weeks by the World Health Organization (14)]. To address the important issue of timing, we examined whether the timing of assessment influenced PPD prevalence through meta-regression in this paper. We also excluded studies reporting PPD prevalence in samples unlikely to be representative of the general population (e.g., studies that exclusively recruited women with a history of depression, teen mothers, immigrant mothers, abused mothers, mothers seeking treatment, mothers of high-risk infants, etc.).

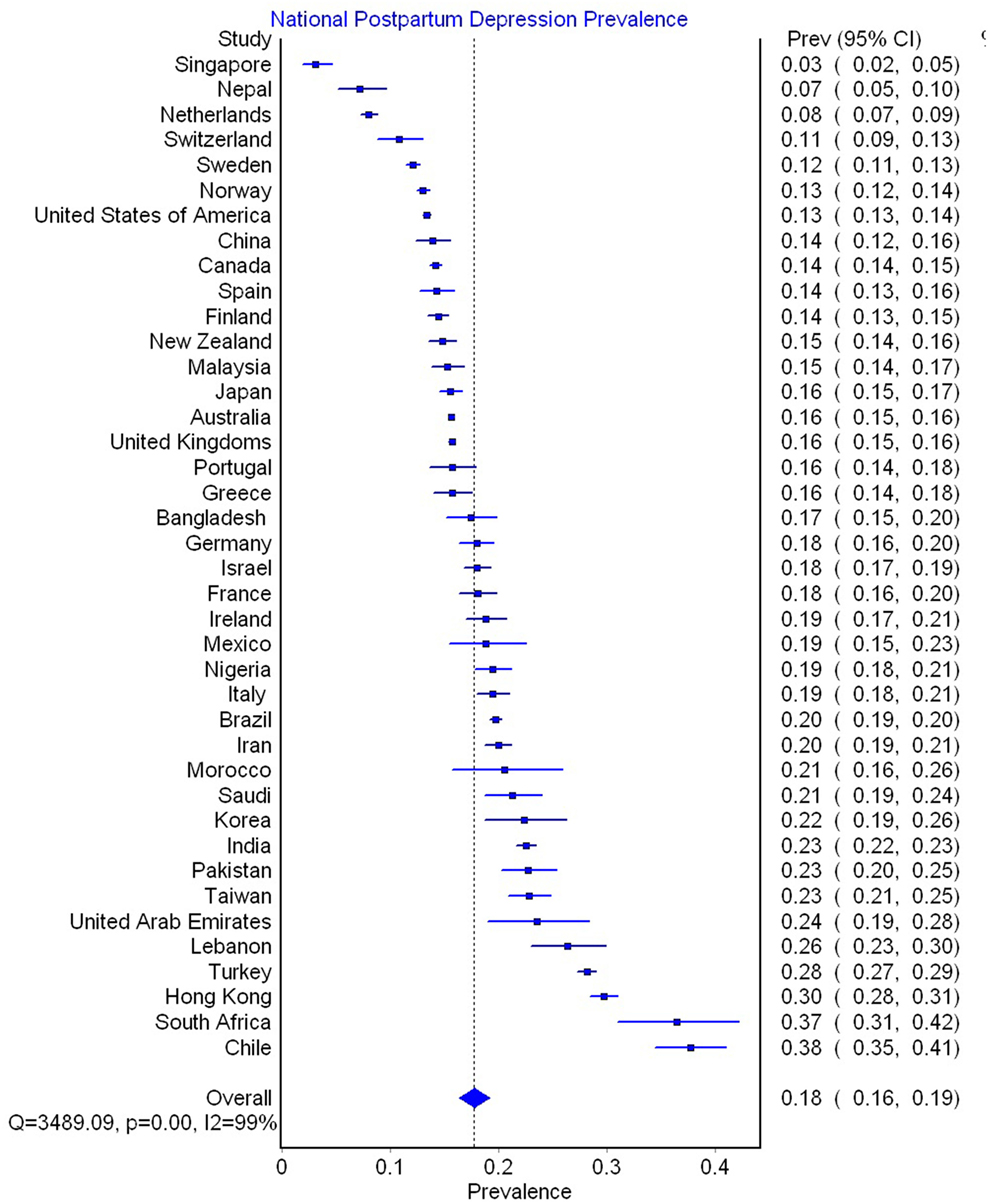

291 studies (of 487 full-text articles assessed for eligibility) met these criteria and were included in this meta-analysis (see Figure 1 for a PRISMA flow diagram reporting identification and selection of studies for the meta-analysis).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram reporting identification and selection of studies for the meta-analysis.

Studies using the EPDS to estimate PPD prevalence were the focus of this meta-analysis and meta-regression for several reasons. First, a recent systematic review of the validated screening tools for common mental disorder strongly recommended the use of the EPDS because it consistently performs well on metrics of internal and external validity, is easy enough to administer in resource-limited settings, and does not include the word “depression” which is stigmatized in some cultures (15). Second, there are advantages to keeping the type of screening tool used consistent across countries when trying to quantify and illuminate the causes of cross-national variability. For example, the wealth of a country strongly determines the type of PPD screening tool used (16) (e.g., it is harder to use time-intensive clinical interviews in resource-poor settings yet easier in resource-rich settings), and the type of screening tool used can influence PPD prevalence (6, 17). Had we included multiple screening tools that differed on ease of administration (e.g., self-report vs. clinical interviews), it would have been difficult to determine whether any observed cross-national variance in PPD prevalence was due to disparities in national wealth or merely an artifact of the assessment tool used. Third, the EPDS had been widely translated and validated for use in at least 18 languages and exhibits good cross-cultural reliability (18). In addition, an examination of previously published systematic reviews showed that roughly 70% of studies used the EPDS to assess PPD prevalence (6, 8, 9). Therefore, the use of the EPDS allowed us to include the majority of studies while limiting confounding variables associated with different types of measurement (8). Finally, because the EPDS is specifically designed for administration in the postpartum period, the scale does not include items assessing changes in appetite, sleep, or weight. Changes in these factors are normal in the postpartum period, yet these somatic items are included as indicators of depression by other self-report screening tools designed to assess depression outside of the postpartum window (e.g., Patient Health Questionnaire-PHQ-9, The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression-HAM-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-CESD, Beck Depression Inventory-BDI, and Zung’s Self-Rating Depression Scale-SDS).

Data Extraction

The following methodological variables were coded from each study: PPD prevalence, total sample size, EPDS cutoff score employed, and the timeframe postpartum in which PPD was assessed. Because meta-analysis requires one estimate of PPD prevalence per study, data from longitudinal studies reporting PPD in the same women at multiple time points were consolidated by averaging the PPD prevalence over the time points weighted by the sample size at each time point. Also, if multiple prevalence rates were reported in the same study using different EPDS cutoffs, the prevalence rate from the lowest EPDS cutoff was chosen by default. This decision could cause a bias toward higher estimates of PPD incidence; therefore, we also used meta-regression to estimate PPD prevalence at the standard recommended EPDS cutoffs for possible (9/10) and probable (12/13) PPD (11).

To investigate whether studies including women earlier or later in the postpartum period report higher PPD prevalence, we created scores for each study reflecting the range of the timeframes postpartum during which PPD was assessed.

National Data

Various methodological, health, economic, policy, and sociodemographic variables were explored as potential predictors of cross-national variation in PPD. Potential cross-national predictors of PPD were chosen because they had been previously hypothesized to predict PPD and reliable national data were available for the majority of counties represented in this meta-analysis. See Data Sheet S1 in Supplementary Material for an Excel file containing all of the national data used.

Methodological Variables

A previous meta-analysis of PPD suggested that it is important to rule out the possibility that cross-national variation in PPD prevalence is explained by methodological conventions used in different countries (7). For example, it is important to know whether systematic methodological differences like assessing PPD earlier postpartum or using higher/lower EPDS cutoff scores are employed in some countries more often than others. Further, if methodological conventions do differ across countries, we need to know the extent to which these explain the apparent cross-national variation in PPD prevalence. To explore this possibility, country sample-size-weighted national averages for each methodological variable were calculated for use in meta-regression models. In addition, we used meta-regression to assess whether the number of studies conducted in a country predicted cross-national PPD prevalence.

Health Variables

Health variables were obtained from UNICEF (19) unless otherwise noted and included infant mortality rate (the probability of dying between birth and age one, expressed per 1,000 live births), lifetime risk of maternal death (the annual number of deaths of women from pregnancy-related causes per 100,000 live births), total fertility rate (the number of children that would be born per woman if she were to live to the end of her childbearing years and bear children in accordance with prevailing age-specific fertility rates), and percentage of low-birthweight infants (born weighing <2,500 g). Percentage of cesarean births was obtained from the World Health Report (20).

Economic and Policy Variables

GINI index (an index of the income distribution of a nation’s residents wherein higher values indicate greater wealth inequality) data were obtained from Ortiz and Cummins (21). Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita (in adjusted US dollars) and percentage of women working ≥40 h a week (aged 25–30) data were obtained from the Annual labor force statistics (22). Additionally, we investigated national provisions for paid and unpaid maternity leave available from the international labor office (23).

Sociodemographic Predictors

The percentage of children living in single parent homes and the percentage of infants born outside of marriage data were obtained from the World Family Map (24). The percentage of urbanized population data were also obtained from UNICEF.

Data Analysis

Following the recommendations for meta-analysis of prevalence (25), we used a double-arcsine transformation of the PPD prevalence data before calculating the study weights and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to avoid the undue large weights obtained for studies with low or high prevalence (prevalence close to 0 or 1). To test for heterogeneity in the data, both the Cochran Q test statistic and the I2 statistic were consulted (26). The same procedure was followed to create meta-analytically derived national estimates of PPD prevalence based solely on the studies available from each country. Meta-analytic estimates of PPD prevalence could not be calculated in countries with fewer than two studies (N = 16) (27). All meta-analyses were conducted using the program MetaXL and the “prev” command (25).

Two sets of meta-regressions were performed, the first addressing which methodological factors predicted variation in PPD across all studies, regardless of the nation in which the study was conducted, and the second addressing predictors of PPD variation across nations. All meta-regression analyses were performed with STATA 14 (28) using the “metareg” command with random-effects models (because all tests indicated significant heterogeneity). To obtain the SEs needed to weight studies (or nations) for meta-regression in STATA, we transformed the 95%-CIs provided by MetaXL using the following formula (upper 95% CI − lower 95% CI)/3.92. Because national data were not available for all variables, the number of countries included is reported for each meta-regression result using national variables.

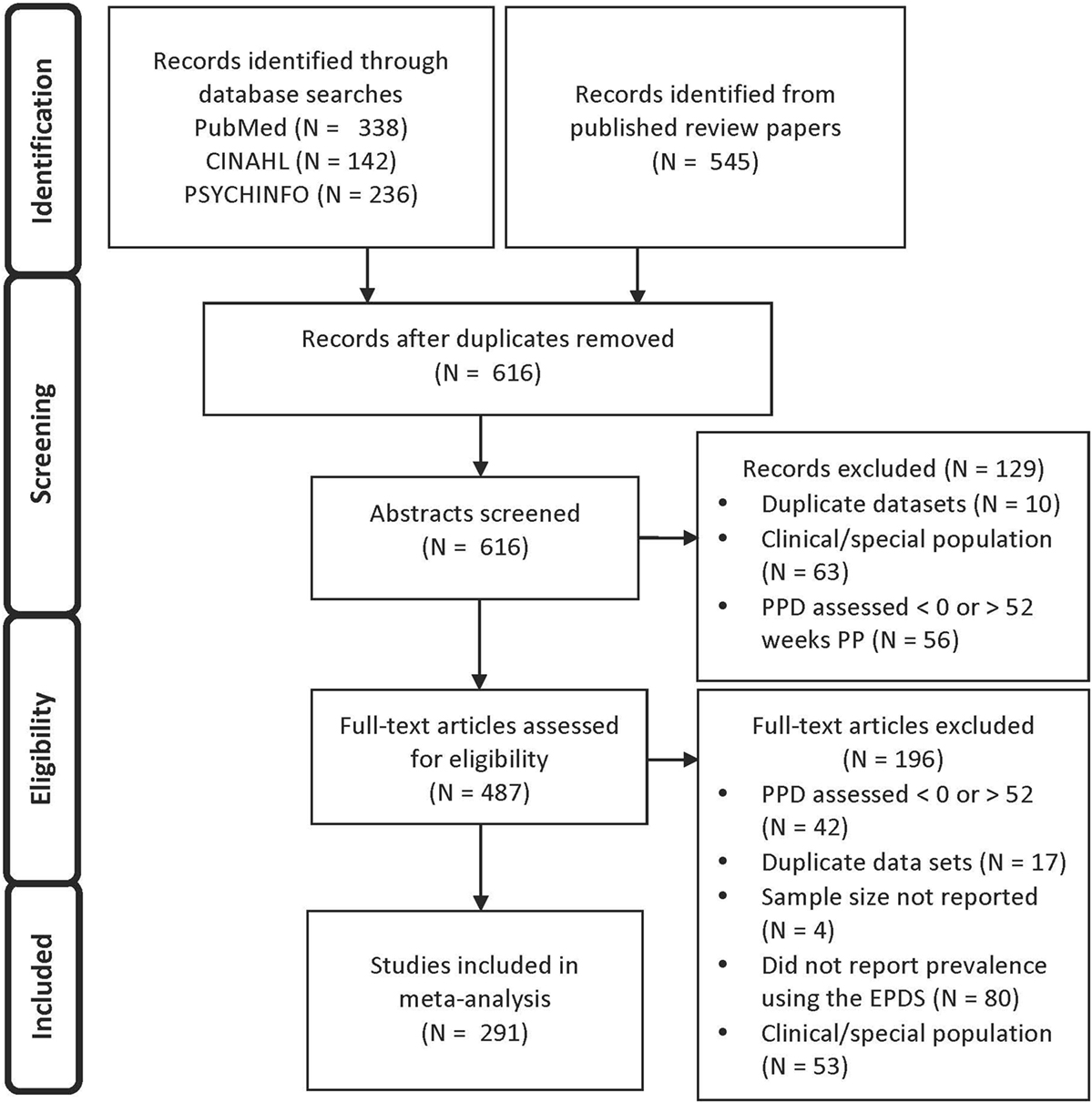

Funnel plots, Doi plot analysis, and the LFK index were used to assess potential publication bias. Specifically, to test whether papers are more or less likely to be published due to higher/lower PPD prevalence.

Statistical significance was evaluated using 2-tailed 0.05-level tests.

Results

Meta-Analysis of Global PPD Prevalence

296,284 women from 291 studies were included in this meta-analysis. Table 1 presents the data extracted from each study. The global pooled prevalence of PPD was 17.7% (95% CI: 16.6 to 18.8%; see Figure S1 in Supplementary Material). There was a significant degree of heterogeneity between studies (Q = 16,823, p = 0.000, I2 = 98%). Adjusting for the recommended EPDS cutoffs yielded a global PPD prevalence of 21.0% (CI: 19.1 to 23.0%) for possible PPD and 16.7% (CI: 14.9 to 18.6%) for probable PPD. See Figure S1 in Supplementary Material for meta-analytically derived PPD estimates for each individual study. There was evidence of publication bias based on sample size (LFK = 1.98; see Funnel Plot in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Funnel plot (A) and Doi plot (B) of postpartum depression (PPD) prevalence as a function of prevalence estimate SE.

Meta-Regression of Between-Study Variation

Studies that used lower cutoffs of the EPDS reported significantly higher prevalence (Coef. = −1.44, SE = 0.455, p = 0.002; CI: −2.333 to −0.542, R2 = 3.08%). Studies that measured PPD later postpartum tended to report slightly lower levels of PPD (Coef. = −0.373, SE = 0.109, p = 0.001, 95% CI: −0.587 to −0.159, R2 = 3.65%). No other methodological variables predicted between-study variation in PPD. Together timing of PPD assessment and cutoff used accounted for 5.21% of the variance in PPD prevalence between studies [F(2, 293) = 6.44, p < 0.002].

Meta-Analyses of National PPD Prevalence

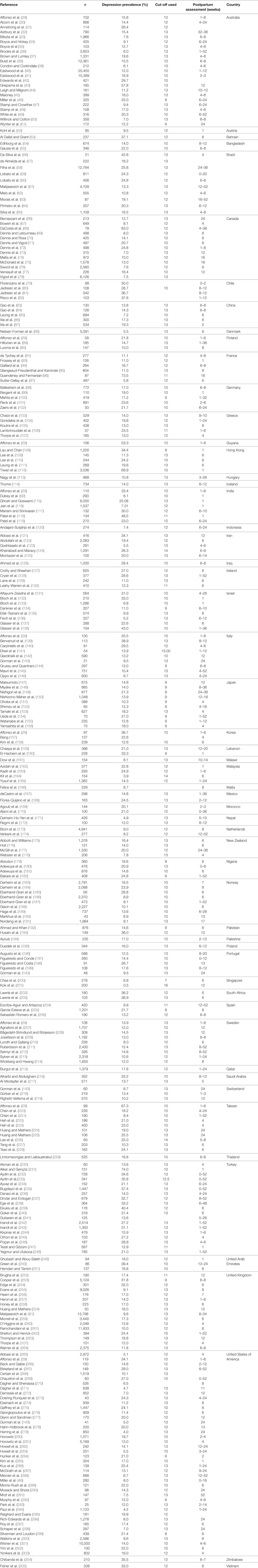

See Figure 3 for meta-analytically derived estimates of PPD prevalence in 40 countries. National sample sizes ranged from 244 to 65,634 women (M = 7,229.76; SD = 13,502.69). National estimates of PPD ranged from 3.1% in Singapore to 37.7% in Chile. Meta-analysis suggested that there was significant heterogeneity in PPD prevalence between nations (Q = 3,489.09, p < 0.001, I2 = 99%).

Meta-Regression of Predictors of Cross-National Variation

Methodological Predictors

None of the methodological variables predicted cross-national variation in PPD prevalence (all ps > 0.15). Therefore, no methodological variables were included as covariates in subsequent models.

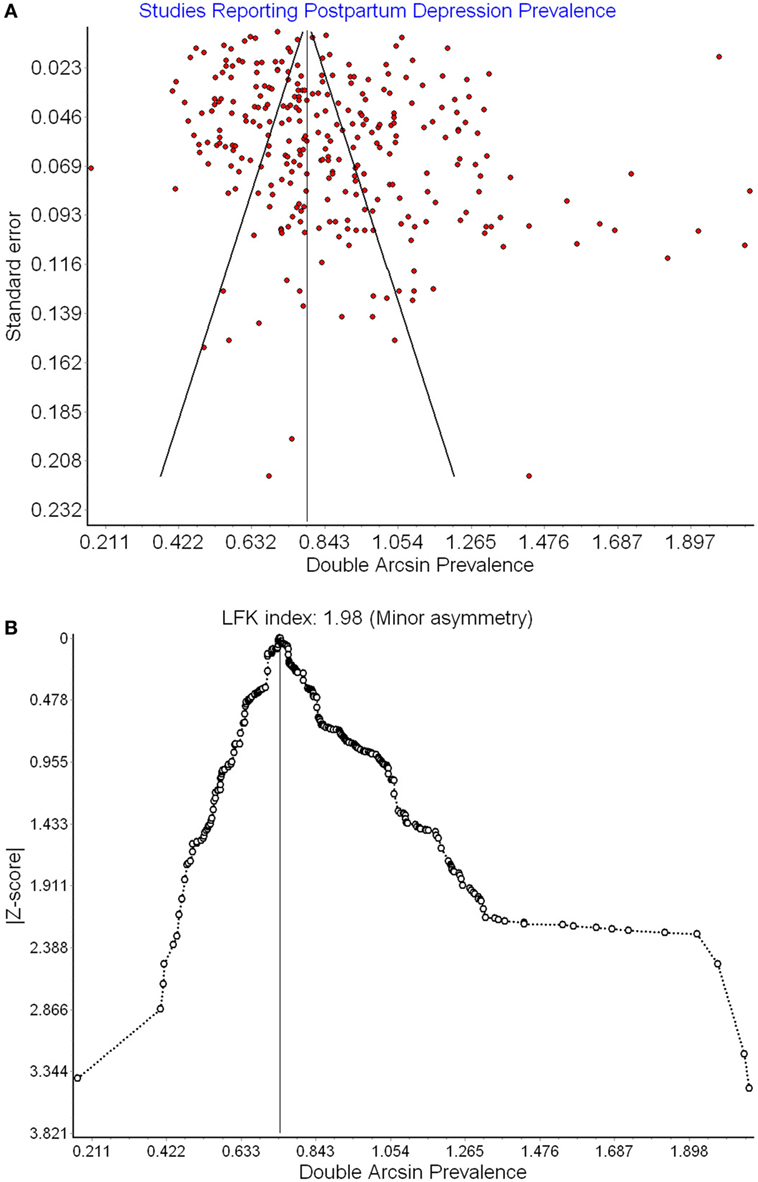

Economic and Policy Predictors

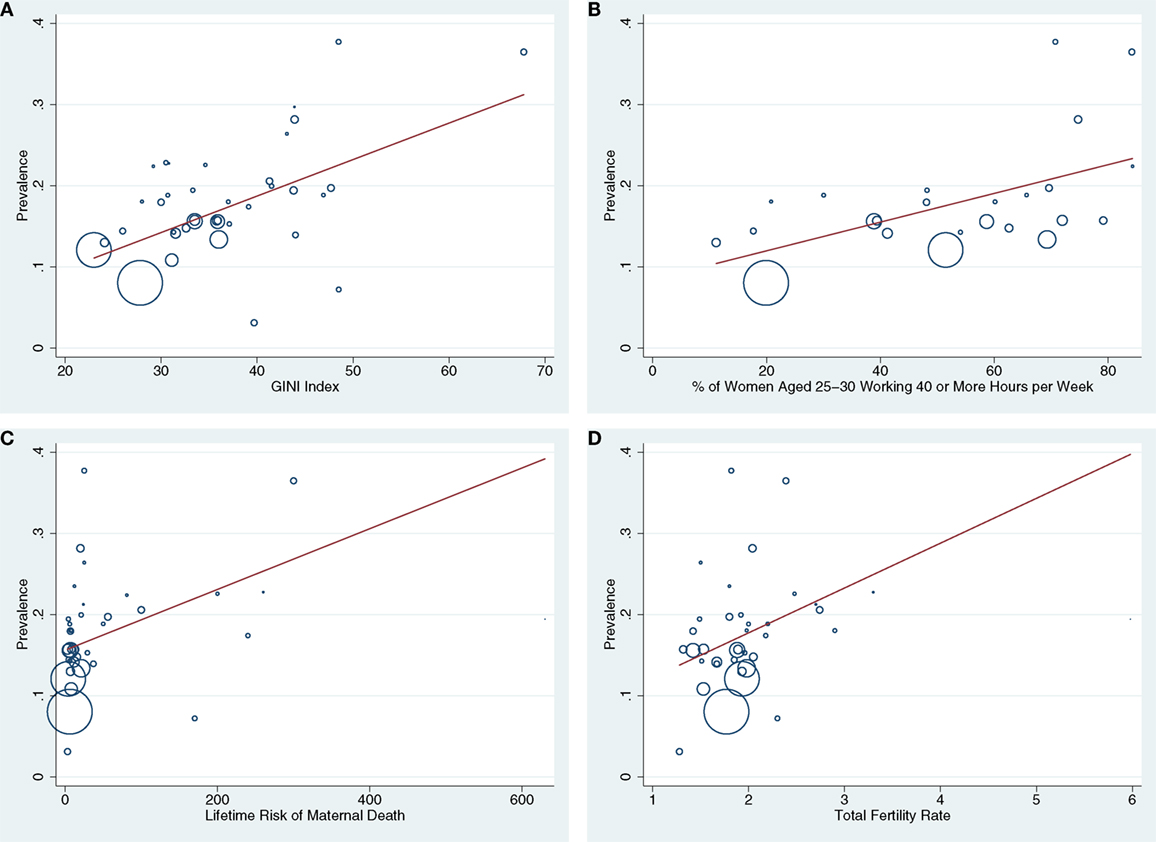

GINI index explained 41% of the cross-national variation in PPD prevalence. Nations with higher wealth inequality had higher levels of PPD (N = 38; Coef. = 0.039, SE = 0.009, p < 0.000, CI: 0.020 to 0.058) (see Figure 4A). GDP per capita was also inversely related to PPD prevalence (N = 39; Coef. = −0.033, SE = 0.009, p = 0.002, CI: −0.053 to −0.014, R2 = 30.4%). However, when GDP per capital and GINI index were modeled together, GINI index remained statistically significant while GDP per capita did not. In addition, countries with higher percentages of young women who were working ≥40 h a week had higher PPD prevalence (N = 24; Coef. = 0.038, SE = 0.013, p < .01, CI: 0.012 to 0.065, R2 = 30.9%; see Figure 4B). National paid and unpaid maternity leave policies did not predict PPD prevalence (ps > 0.60). Together, economic predictors (GINI index, GDP per capita, and women working >40 h per week) accounted for 73.1% of the cross-national variation in PPD prevalence, although GINI index was the only unique economic predictor in a multivariate model.

Figure 4. (A–D) Bubble plots are presented showing the associations between GINI index (A), % of women aged 25–30 working ≥40 h a week (B), lifetime risk of maternal death (C), and total fertility rate (D) with national postpartum depression (PPD) prevalence. Countries with larger bubbles had larger sample sizes and were weighted accordingly in meta-regression models.

Health Predictors

Rates of maternal mortality and total fertility in Nigeria were more than 4 SDs above the mean, therefore Nigeria was excluded from analyses involving these factors. Higher prevalence of PPD was reported in countries with higher risk of maternal or infant mortality (maternal mortality: N = 36; Coeff. = 0.045, SE = 0.019, p = 0.024, CI = 0.006 to 0.085), R2 change = 18.73%, see Figure 4C; infant mortality: N = 36; Coeff. = 0.039, SE = 0.018, p = 0.034, CI: 0.003 to 0.074; R2 change = 15.56%). There were also statistical trends suggesting that higher national PPD prevalence was associated with higher total fertility rates (N = 36; Coeff. = 0.040, SE = 0.024, p = 0.102, CI: −0.008 to 0.088; R2 change = 6.33%, see Figure 4D) and higher percentages of infants born low birth weight (N = 36; Coeff. = 0.023, SE = 0.014, p = 0.094, CI: −0.004 to 0.051; R2 change = 9.99%). National cesarean rates did not predict PPD prevalence. Together, these health factors predicted 26.03% of the variance in PPD prevalence, although maternal mortality rate was the only unique predictor in multivariate models when all health variables were included.

Sociodemographic Predictors

The percentages of infants born outside of marriage, living in single parent homes or in urbanized areas did not predict cross-national PPD prevalence.

In sum, economic and health variables explained 73.87% percent of the cross-national variation in PPD [N = 24; F(3, 20) = 13.27, p < 0.001]. Notably, GINI index was the only significant independent predictor of cross-national PPD incidence when all health and economic predictors were included together in the model.

Discussion

In the largest meta-analysis and meta-regression of PPD to date, the global prevalence of PPD was found to be approximately 17.7% (95% CI: 16.6–18.8%). Adjusting for the recommended cutoffs provided by the EPDS for possible (≥10) and probable depression (≥13) yielded prevalence estimates of 21.3 and 16.7%, respectively. These estimates are significantly higher than the widely cited prevalence of 13% (95% CI: 12.3–13.4%), derived from a meta-analysis of studies from developed countries (6). Our estimate is more similar to the 19% prevalence for PPD derived from studies of relatively low- and middle-income countries (7). We found some evidence of publication bias wherein larger studies reported lower PPD prevalence (R2 = 0.8%). However, this effect was small and most likely a byproduct of the fact that countries with more wealth inequality tend to produce studies with smaller sample sizes and wealth inequality (GINI index) between nations predicted 41% of the cross-national variation in PPD in this meta-analysis and meta-regression.

The current meta-analysis also revealed large disparities in PPD prevalence across nations. The countries with the highest rates of PPD were Chile (38%, 95% CI: 35–41%), South Africa (37%; 95% CI: 31–42%), Hong Kong (30%, CI: 28–31%), and Turkey (28%, CI: 27–29%). In contrast, countries with the lowest rates included Singapore (3%; 95% CI: 2–5%), Nepal (7%; 95% CI: 5–10%), the Netherlands (8%; 95% CI: 7–9%), and Switzerland (11%; 95% CI: 7–13%). Surprisingly, these national differences in PPD prevalence could not be explained by methodological conventions used in different counties, for example, the typical EPDS cutoff used, sample size, or the timing of PPD assessment. Instead, the vast majority (73%) of the cross-national variation in PPD prevalence could be explained by economic and health disparities between nations.

Notably, national disparities in PPD appear to exist even among countries that fall within similar economic strata. For example, Chile evinced the highest rates of PPD whereas another high-income nation, the Netherlands, had among the lowest. As many scholars have pointed out (306–308), aggregate wealth metrics like GDP give only a very limited picture of the circumstances of large portions of the population. Instead, we found that wealth disparities (i.e., GINI coefficients) was the most robust predictor of cross-national variation in PPD. Countries with higher GINI coefficients have a greater proportion of citizens living in abject poverty, which is a potent predictor of many mental and physical health problems (309). As previous investigators have also noted, living below the material standards of one’s society equates to possessing low social status—regardless of objective income—which can limit access to less tangible resources like education, opportunity, and security (308). Loss of these forms of social capital is thought to contribute to family dysfunction, health problems, and mood disorders (28).

Relatedly, countries with higher rates of wealth inequality in this meta-analysis also tended to have a higher percentage of women of childbearing age working full-time (Coef. = 0.553, SE = 0.126, p = 0.001, CI: = 0.250 to 856, R2 = 36.9%). This fact may partially explain why countries in which higher proportions of women of childbearing age work full-time have a higher prevalence of PPD. Working full-time while caring for young children can place multiple demands on new mothers (310, 311), causing stress and family discord linked to PPD. These findings militate for PPD intervention efforts focusing on providing support for working mothers.

Our finding that maternal mortality predicts 19% of the cross-national variation in PPD prevalence can be interpreted in several ways. First, suicide linked to mental illness is a major cause of maternal mortality in many countries (1, 2). However, maternal mortality is also a reliable proxy of poor access to medical care, consistent with our finding that higher rates of infant mortality and low birth weight also predicted higher national PPD prevalence. The relationship between maternal mortality and PPD is likely bidirectional, with PPD driving maternal mortality rates and poor healthcare driving both maternal mortality and PPD risk. Therefore, efforts to improve either of these outcomes are likely to evince spillover benefits improving the other. Relatedly, high total fertility rates predicted elevated PPD prevalence, suggesting that improved access to contraception associated with healthcare services may also reduce national PPD prevalence.

Limitations

Several methodological limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this meta-analysis and meta-regression. First, clinical interviews are the gold standard for PPD diagnosis, whereas our analysis focused on a widely used self-report measure. Self-report measures tend to yield higher estimates of PPD than clinical interviews, therefore, our estimates are likely higher than if we had focused on interview methods (6). However, given the serious consequences of PPD, we felt it was better to potentially overestimate than to underestimate national prevalence. Second, several countries had few studies (e.g., Finland, Mexico, and Nepal), rendering those national estimates less reliable relative to countries where the bulk of PPD research has been done (e.g., the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia). Finally, many potential predictors of cross-national PPD prevalence were beyond the scope of this study ranging from degree of cultural collectivism to rates of vitamin D deficiency (311–313). We hope that the data set provided in this study will allow future researchers to uncover additional structural, cultural and health predictors of cross-national variation in PPD prevalence.

Conclusion

In sum, our findings reveal that the global prevalence of PPD is both higher and more variable than previously thought, and that wealth inequality, maternal-child health indexes, and employment patterns explain most of the cross-national variation. Creating meaningful improvements in these areas presents enormous social challenges, yet the potential benefits of reducing PPD for mothers, families, and infants are equally great.

Author Contributions

JH-H conceptualized the research questions, conducted the analysis, wrote the paper, and approved this manuscript. TC-H and IA helped to compile the data set, write the manuscript, and approved this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Taylor Delaney, Lilly Murphy, Holly Rankin, Ian Nel, and Nicole Wright for assistance in compiling the data set. The authors would also like to acknowledge the work of Halbreich U, Karkun S, Norhayati MN, Hazlina NN, Asrenee AR, Emilin WW, Fisher A, Cabral de Mello C, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, and Holmes W for creating the careful systematic reviews on which this work heavily relied.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00248/full#supplementary-material.

References

1. Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull (2003) 67(1):219–29. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldg011

2. Miranda JJ, Patel V. Achieving the millennium development goals: does mental health play a role? PLoS Med (2005) 2(10):e291. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020291

3. Field T. Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: a review. Infant Behav. Dev. (2010) 33(1):1–6. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.04.005

4. Paulson JF, Dauber S, Leiferman JA. Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics (2006) 118(2):659–68. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2948

5. Grace SL, Evindar A, Stewart D. The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health (2003) 6(4):263–74. doi:10.1007/s00737-003-0024-6

6. O’hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry (1996) 8(1):37–54. doi:10.3109/09540269609037816

7. Fisher J, Cabral de MelloMello M, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull WHO (2012) 90(2):139–49. doi:10.2471/BLT.11.091850

8. Halbreich U, Karkun S. Cross-cultural and social diversity of prevalence of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord (2006) 91(2):97–111. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.051

9. Norhayati M, Hazlina NN, Asrenee A, Emilin W. Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: a literature review. J Affect Disord (2015) 175:34–52. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.041

10. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med (2009) 6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

11. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry (1987) 150(6):782–6. doi:10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

12. Yim S, Tanner Stapleton L, Guardino C, Hahn-Holbrook J, Dunkel Schetter C. Biological and psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression: systematic review and call for integration. Ann Rev Clin Psychol (2015) 11:99–37. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-101414-020426

13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnositic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: Am. Psychiatr. Publ.

14. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organisation (2004).

15. Ali G-C, Ryan G, De Silva MJ. Validated screening tools for common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One (2016) 11(6):e0156939. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156939

16. Evagorou O, Arvaniti A, Samakouri M. Cross-cultural approach of postpartum depression: manifestation, practices applied, risk factors and therapeutic interventions. Psychiatr Q (2016) 87(1):129–54. doi:10.1007/s11126-015-9367-1

17. Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. (2005). Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes: Summary.

18. Marshall J, Bethell K. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): Translated Versions – Validated. Perth, Western Australia: Department of Health, Government of Western Australia (2006).

19. UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2015: Reimagine the Future: Innovation for Every Child. New York, NY: UNICEF (2015).

20. Gibbons L, Belizán JM, Lauer JA, Betrán A, Merialdi M, Althabe F. The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. World Health Rep (2010) 30:1–31.

21. Ortiz I, Cummins M. (2011). Global Inequality: Beyond the bottom billion – a rapid review of income distribution in 141 countries.

23. Addati L, Cassirer N, Gilchrist K. Maternity and Paternity at Work: Law and Practice Across the World. Geneva: International Labour Office (2014).

24. Trends C. World Family Map: Mapping Family Change and Child Well-Being Outcomes. Child Trends (2014).

25. Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health (2013) 67(11):974–8. doi:10.1136/jech-2013-203104

26. Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods (2006) 11(2):193. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193

27. Valentine JC, Pigott TD, Rothstein HR. How many studies do you need? A primer on statistical power for meta-analysis. J Educ Behav Stat (2010) 35(2):215–47. doi:10.3102/1076998609346961

29. Affonso DD, De AK, Horowitz JA, Mayberry LJ. An international study exploring levels of postpartum depressive symptomatology. J Psychosom Res (2000) 49(3):207–16. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00176-8

30. Alcorn KL, O’Donovan A, Patrick JC, Creedy D, Devilly GJ. A prospective longitudinal study of the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from childbirth events. Psychol Med (2010) 40(11):1849–59. doi:10.1017/S0033291709992224

31. Armstrong KL, Haeringen AV, Dadds MR, Cash R. Sleep deprivation or postnatal depression in later infancy: separating the chicken from the egg. J Paediatr Child Health (1998) 34(3):260–2. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1754.1998.00213.x

32. Astbury J, Brown S, Lumley J, Small R. Birth events, birth experiences and social differences in postnatal depression. Aust J Public Health (1994) 18(2):176–84. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.1994.tb00222.x

33. Bilszta JC, Gu YZ, Meyer D, Buist AE. A geographic comparison of the prevalence and risk factors for postnatal depression in an Australian population. Aust N Z J Public Health (2008) 32(5):424–30. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00274.x

34. Boyce P, Hickey A. Psychosocial risk factors to major depression after childbirth. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2005) 40(8):605–12. doi:10.1007/s00127-005-0931-0

35. Boyce PM, Stubbs J, Todd AL. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation for an Australian sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (1993) 27(3):472–6. doi:10.3109/00048679309075805

36. Brooks J, Nathan E, Speelman C, Swalm D, Jacques A, Doherty D. Tailoring screening protocols for perinatal depression: prevalence of high risk across obstetric services in Western Australia. Arch Womens Ment Health (2009) 12(2):105–12. doi:10.1007/s00737-009-0048-7

37. Brown S, Lumley J. Changing childbirth: lessons from an Australian survey of 1336 women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol (1998) 105(2):143–55.

38. Buist AE, Austin MP, Hayes BA, Speelman C, Bilszta JL, Gemmill AW, et al. Postnatal mental health of women giving birth in Australia 2002-2004: findings from the beyondblue National Postnatal Depression Program. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2008) 42(1):66–73. doi:10.1080/00048670701732749

39. Condon JT, Corkindale C. The correlates of antenatal attachment in pregnant women. Br J Med Psychol (1997) 70(4):359–72. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1997.tb01912.x

40. Eastwood JG, Phung H, Barnett B. Postnatal depression and socio-demographic risk: factors associated with Edinburgh Depression Scale scores in a metropolitan area of New South Wales, Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2011) 45(12):1040–6. doi:10.3109/00048674.2011.619160

41. Eastwood JG, Jalaludin BB, Kemp LA, Phung HN, Barnett BW. Relationship of postnatal depressive symptoms to infant temperament, maternal expectations, social support and other potential risk factors: findings from a large Australian cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth (2012) 12:148. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-148

42. Edwards B, Galletly C, Semmler-Booth T, Dekker G. Antenatal psychosocial risk factors and depression among women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged suburbs in Adelaide, South Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2008) 42(1):45–50. doi:10.1080/00048670701732673

43. Griepsma J, Marcollo J, Casey C, Cherry F, Vary E, Walton V. The incidence of postnatal depression in a rural area and the needs of affected women. Aust J Adv Nurs (1994) 11(4):19–23.

44. Leigh B, Milgrom J. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry (2008) 8:24. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-8-24

45. Maloney DM. Postnatal depression: a study of mothers in the metropolitan area of Perth, Western Australia. Aust Coll Midwives Inc J (1998) 11(2):18–23. doi:10.1016/S1031-170X(98)80030-5

46. Miller RL, Pallant JF, Negri LM. Anxiety and stress in the postpartum: is there more to postnatal distress than depression? BMC Psychiatry (2006) 6:12. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-6-12

47. Stamp GE, Crowther CA. Postnatal depression: a South Australian prospective survey. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol (1994) 34(2):164–7. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.1994.tb02681.x

48. Stamp GE, Williams AS, Crowther CA. Predicting postnatal depression among pregnant women. Birth (1996) 23(4):218–23. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.1996.tb00498.x

49. White T, Matthey S, Boyd K, Barnett B. Postnatal depression and post-traumatic stress after childbirth: prevalence, course and co-occurrence. J Reprod Infant Psychol (2006) 24(2):107–20. doi:10.1080/02646830600643874

50. Willinick LA, Cotton SM. Risk factors for postnatal depression. Aust Midwifery (2004) 17(2):10–5. doi:10.1016/S1448-8272(04)80004-X

51. Wynter K, Rowe H, Fisher J. Common mental disorders in women and men in the first six months after the birth of their first infant: a community study in Victoria, Australia. J Affect Disord (2013) 151(3):980–5. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.021

52. Kohl C, Walch T, Huber R, Kemmler G, Neurauter G, Fuchs D, et al. Measurement of tryptophan, kynurenine and neopterin in women with and without postpartum blues. J Affect Disord (2005) 86(2):135–42. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.013

53. Al Dallal FH, Grant IN. Postnatal depression among Bahraini women: prevalence of symptoms and psychosocial risk factors. East Mediterr Health J (2012) 18(5):439–45. doi:10.4236/ojog.2015.511086

54. Edhborg M, Nasreen H, Kabir ZN. Impact of postpartum depressive and anxiety symptoms on mothers’ emotional tie to their infants 2–3 months postpartum: a population-based study from rural Bangladesh. Arch Womens Ment Health (2011) 14(4):307–16. doi:10.1007/s00737-011-0221-7

55. Gausia K, Fisher C, Ali M, Oosthuizen J. Magnitude and contributory factors of postnatal depression: a community-based cohort study from a rural subdistrict of Bangladesh. Psychol Med (2009) 39(6):999–7. doi:10.1017/S0033291708004455

56. Da-Silva VA, Moraes-Santos AR, Carvalho MS, Martins ML, Teixeira NA. Prenatal and postnatal depression among low income Brazilian women. Braz J Med Biol Res (1998) 31(6):799–804. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X1998000600012

57. de Almeida LS, Jansen K, Köhler CA, Pinheiro RT, da Silva RA, Bonini JS. Working and short-term memories are impaired in postpartum depression. J Affect Disord (2012) 136(3):1238–42. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.031

58. Filha MM, Ayers S, da Gama SG, do Carmo Leal M. Factors associated with postpartum depressive symptomatology in Brazil: the Birth in Brazil National Research Study, 2011/2012. J Affect Disord (2016) 194:159–67. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.020

59. Lobato G, Moraes CL, Dias AS, Reichenheim ME. Postpartum depression according to time frames and sub-groups: a survey in primary health care settings in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Arch Womens Ment Health (2011) 14(3):187–93. doi:10.1007/s00737-011-0206-6

60. Lobato G, Brunner MA, Dias MA, Moraes CL, Reichenheim ME. Higher rates of postpartum depression among women lacking care after childbirth: clinical and epidemiological importance of missed postnatal visits. Arch Womens Ment Health (2012) 15(2):145–6. doi:10.1007/s00737-012-0256-4

61. Matijasevich A, Golding J, Smith GD, Santos IS, Barros AJ, Victora CG. Differentials and income-related inequalities in maternal depression during the first two years after childbirth: birth cohort studies from Brazil and the UK. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health (2009) 5(1):1. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-5-12

62. Melo EF, Cecatti JG, Pacagnella RC, Leite DF, Vulcani DE, Makuch MY. The prevalence of perinatal depression and its associated factors in two different settings in Brazil. J Affect Disord (2012) 136(3):1204–8. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.023

63. Morais M, Lucci TK, Otta E. Postpartum depression and child development in first year of life. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas) (2013) 30(1):7–17. doi:10.1590/S0103-166X2013000100002

64. Pinheiro RT, Coelho FM, Silva RA, Pinheiro KA, Oses JP, Quevedo Lde Á, et al. Association of a serotonin transporter gene polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and stressful life events with postpartum depressive symptoms: a population-based study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol (2013) 34(1):29–33. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2012.759555

65. Silva R, Jansen K, Souza L, Quevedo L, Barbosa L, Moraes I, et al. Sociodemographic risk factors of perinatal depression: a cohort study in the public health care system. Rev Bras Psiquiatr (2012) 34(2):143–8. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462012000200005

66. Bernazzani O, Saucier J, David H, Borgeat F. Psychosocial predictors of depressive symptomatology level in postpartum women. J Affect Disord (1997) 46(1):39–49. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00077-3

67. Bowen A, Bowen R, Butt P, Rahman K, Muhajarine N. Patterns of depression and treatment in pregnant and postpartum women. Can J Psychiatry (2012) 57(3):161–7. doi:10.1177/070674371205700305

68. DaCosta D, Dritsa M, Rippen N, Lowensteyn I, Khalifé S. Health-related quality of life in postpartum depressed women. Arch Womens Ment Health (2006) 9(2):95–102. doi:10.1007/s00737-005-0108-6

69. Dennis C, Letourneau N. Global and relationship-specific perceptions of support and the development of postpartum depressive symptomatology. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2007) 42(5):389–95. doi:10.1007/s00127-007-0172-5

70. Dennis C, Ross L. Women’s perceptions of partner support and conflict in the development of postpartum depressive symptoms. J Adv Nurs (2006) 56(6):588–99. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04059.x

71. Dennis C, Vigod S. The relationship between postpartum depression, domestic violence, childhood violence, and substance use: epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Violence Against Women (2013) 19(4):503–17. doi:10.1177/1077801213487057

72. Dennis CE, Janssen PA, Singer J. Identifying women at-risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2004) 110(5):338–46. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00337.x

73. Dennis C, Hodnett E, Kenton L, Weston J, Zupancic J, Stewart DE, et al. Effect of peer support on prevention of postnatal depression among high risk women: multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ (2009) 77:280–4.

74. Malta LA, McDonald SW, Hegadoren KM, Weller CA, Tough SC. Influence of interpersonal violence on maternal anxiety, depression, stress and parenting morale in the early postpartum: a community based pregnancy cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth (2012) 12:153. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-153

75. McDonald S, Wall J, Forbes K, Kingston D, Kehler H, Vekved M, et al. Development of a prenatal psychosocial screening tool for post-partum depression and anxiety. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol (2012) 26(4):316–27. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01286.x

76. Sword W, Landy CK, Thabane L, Watt S, Krueger P, Farine D, et al. Is mode of delivery associated with postpartum depression at 6 weeks: a prospective cohort study. BJOG (2011) 118(8):966–77. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02950.x

77. Verreault N, Da Costa D, Marchand A, Ireland K, Dritsa M, Khalifé S. Rates and risk factors associated with depressive symptoms during pregnancy and with postpartum onset. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol (2014) 35(3):84–91. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2014.947953

78. Vigod SN, Tarasoff LA, Bryja B, Dennis C, Yudin MH, Ross LE. Relation between place of residence and postpartum depression. Can Med Assoc J (2013) 185(13):1129–35. doi:10.1503/cmaj.122028

79. Florenzano R, Botto A, Muñiz C, Rojas J, Astorquiza J, Gutierrez L. Frecuencia de síntomas depresivos medidos con el EPDS en puérperas hospitalizadas en el hospital del Salvador [Frequency of depressive symptoms measured with the EPDS in postpartum women hospitalized at the Hospital del Salvador]. Revista Chilena de Neuro-Psiquiatría (2002) 40(Suppl 4):10. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S51436

80. Jadresic E, Jara C, Miranda M, Arrau B, Araya R. Trastornos emocionales en el embarazo y el puerperio: estudio prospectivo de 108 mujeres [Emotional disorders in pregnancy and postpartum: prospective study of 108 women]. Revista Chilena de Neuro-Psiquiatría (1992) 30(2):99–106.

81. Jadresic E, Araya R, Jara C. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Chilean postpartum women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol (1995) 16(4):187–91. doi:10.3109/01674829509024468

82. Risco L, Jadresic E, Galleguillos T, Garay JL, González M, Hasbún J. Depresión posparto: alta frecuencia en puérperas chilenas, detección precoz, seguimiento y factores de riesgo [Postpartum depression: high frequency in Chilean postpartum, early detection, follow-up and risk factors]. Psiquiatría y Salud Integral (2002) 2:61–6. doi:10.4067/S0034-98872008000100006

83. Gao L, Chan SW, Mao Q. Depression, perceived stress, and social support among first-time Chinese mothers and fathers in the postpartum period. Res Nurs Health (2009) 32(1):50–8. doi:10.1002/nur.20306

84. Gao LL, Chan SW, You L, Li X. Experiences of postpartum depression among first-time mothers in mainland China. J Adv Nurs (2010) 66(2):303–12. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05169.x

85. Leung WC, Kung F, Lam J, Leung TW, Ho PC. Domestic violence and postnatal depression in a Chinese community. Int J Gynaecol Obstet (2002) 79(2):159–66. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00236-9

86. Xie R, He G, Liu A, Bradwejn J, Walker M, Wen SW. Fetal gender and postpartum depression in a cohort of Chinese women. Soc Sci Med (2007) 65(4):680–4. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.003

87. Xie RH, Lei J, Wang S, Xie H, Walker M, Wen SW. Cesarean section and postpartum depression in a cohort of Chinese women with a high cesarean delivery rate. J Womens Health (2011) 20(12):1881–6. doi:10.1089/jwh.2011.2842

88. Nielsen Forman D, Videbech P, Hedegaard M, Dalby Salvig J, Secher NJ. Postpartum depression: identification of women at risk. BJOG (2000) 107(10):1210–7. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11609.x

89. Hiltunen P, Raudaskoski T, Ebeling H, Moilanen I. Does pain relief during delivery decrease the risk of postnatal depression? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand (2004) 83(3):257–61. doi:10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.0302.x

90. Luoma I, Tamminen T, Kaukonen P, Laippala P, Puura K, Salmelin R, et al. Longitudinal study of maternal depressive symptoms and child well-being. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2001) 40(12):1367–74. doi:10.1097/00004583-200112000-00006

91. de Tychey C, Spitz E, Briançon S, Lighezzolo J, Girvan F, Rosati A, et al. Pre- and postnatal depression and coping: a comparative approach. J Affect Disord (2005) 85(3):323–6. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.004

92. Dubey C, Gupta N, Bhasin S, Muthal RA, Arora R. Prevalence and associated risk factors for postpartum depression in women attending a tertiary hospital, Delhi, India Int J Soc Psychiatry (2012) 58(6):577–80. doi:10.1177/0020764011415210

93. Fossey L, Papiernik E, Bydlowski M. Postpartum blues: a clinical syndrome and predictor of postnatal depression? J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol (1997) 18(1):17–21. doi:10.3109/01674829709085564

94. Gaillard A, Le Strat Y, Mandelbrot L, Keïta H, Dubertret C. Predictors of postpartum depression: prospective study of 264 women followed during pregnancy and postpartum. Psychiatry Res (2014) 215(2):341–6. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2013.10.003

95. Glangeaud-Freudenthal NMC, Kaminski M. Severe post-delivery blues: associated factors. Arch Womens Ment Health (1999) 2(1):37–44. doi:10.1007/s007370050033

96. Guedeney N, Fermanian J. Validation study of the French version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): new results about use and psychometric properties. Eur Psychiatry (1998) 13(2):83–9. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(98)80023-0

97. Sutter-Dallay AL, Giaconne-Marcesche V, Glatigny-Dallay E, Verdoux H. Women with anxiety disorders during pregnancy are at increased risk of intense postnatal depressive symptoms: a prospective survey of the MATQUID cohort. Eur Psychiatry (2004) 19(8):459–63. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.09.025

98. Ballestrem CL, Strauss M, Kächele H. Contribution to the epidemiology of postnatal depression in Germany – implications for the utilization of treatment. Arch Womens Ment Health (2005) 8(1):29–35. doi:10.1007/s00737-005-0068-x

99. Bergant AM, Nguyen T, Heim K, Ulmer H, Dapunt O. Deutschsprachige Fassung und Validierung der Edinburgh postnatal depression scale [German language version and validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr (1998) 123(3):35–40. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1023895

100. Mehta D, Quast C, Fasching PA, Seifert A, Voigt F, Beckmann MW, et al. The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism modulates the influence on environmental stressors on peripartum depression symptoms. J Affect Disord (2012) 136(3):1192–7. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.042

101. Reck C, Struben K, Backenstrass M, Stefenelli U, Reinig K, Fuchs T, et al. Prevalence, onset and comorbidity of postpartum anxiety and depressive disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2008) 118(6):459–68. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01264.x

102. Zaers S, Waschke M, Ehlert U. Depressive symptoms and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in women after childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol (2008) 29(1):61–71. doi:10.1080/01674820701804324

103. Chatzi L, Melaki V, Sarri K, Apostolaki I, Roumeliotaki T, Georgiou V, et al. Dietary patterns during pregnancy and the risk of postpartum depression: the mother-child ’Rhea’ cohort in Crete, Greece. Public Health Nutr (2011) 14(9):1663–70. doi:10.1017/S1368980010003629

104. Gonidakis F, Rabavilas AD, Varsou E, Kreatsas G, Christodoulou GN. A 6-month study of postpartum depression and related factors in Athens Greece. Compr Psychiatry (2008) 49(3):275–82. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.05.018

105. Koutra K, Vassilaki M, Georgiou V, Koutis A, Bitsios P, Chatzi L, et al. Antenatal maternal mental health as determinant of postpartum depression in a population based mother – child cohort (Rhea Study) in Crete, Greece. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2014) 49(5):711–21. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0758-z

106. Lambrinoudaki I, Rizos D, Armeni E, Pliatsika P, Leonardou A, Sygelou A, et al. Thyroid function and postpartum mood disturbances in Greek women. J Affect Disord (2010) 121(3):278–82. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.07.001

107. Thorpe KJ, Dragonas T, Golding J. The effects of psychosocial factors on the emotional well-being of women during pregnancy: a cross-cultural study of Britain and Greece. J Reprod Infant Psychol (1992) 10(4):191–204. doi:10.1080/02646839208403953

108. Lau Y, Chan KS. Influence of intimate partner violence during pregnancy and early postpartum depressive symptoms on breastfeeding among Chinese women in Hong Kong. J Midwifery Womens Health (2007) 52(2):e15–20. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.09.001

109. Lee DS, Yip SK, Chiu HK, Leung TS, Chan KM, Chau IL, et al. Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese women: validation of the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry (1998) 172:433–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.172.5.433

110. Lee DS, Chung TH. Postnatal depression: an update. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol (2007) 21(2):183–91. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.10.003

111. Leung SK, Martinson IM, Arthur D. Postpartum depression and related psychosocial variables in Hong Kong Chinese women: findings from a prospective study. Res Nurs Health (2005) 28(1):27–38. doi:10.1002/nur.20053

112. Tiwari A, Chan KL, Fong D, Leung WC, Brownridge DA, Lam H, et al. The impact of psychological abuse by an intimate partner on the mental health of pregnant women. BJOG (2008) 115(3):377–84. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01593.x

113. Nagy E, Molnar P, Pal A, Orvos H. Prevalence rates and socioeconomic characteristics of post-partum depression in Hungary. Psychiatry Res (2011) 185(1):113–20. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.05.005

114. Thome M. Predictors of postpartum depressive symptoms in Icelandic women. Arch Womens Ment Health (2000) 3(1):7–14. doi:10.1007/PL00010326

115. Ghosh A, Goswami S. Evaluation of post partum depression in a tertiary hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol India (2011) 61(5):528–30. doi:10.1007/s13224-011-0077-9

116. Jain A, Tyagi P, Kaur P, Puliyel J, Sreenivas V. Association of birth of girls with postnatal depression and exclusive breastfeeding: an observational study. BMJ Open (2014) 4(6):e003545. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003545

117. Mariam KA, Srinivasan K. Antenatal psychological distress and postnatal depression: a prospective study from an urban clinic. Asian J Psychiatry (2009) 2(2):71–3. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2009.04.002

118. Patel HL, Ganjiwale JD, Nimbalkar AS, Vani SN, Vasa R, Nimbalkar SM. Characteristics of Postpartum Depression in Anand District, Gujarat, India. J Trop Pediatr (2015) 61(5):364–9. doi:10.1093/tropej/fmv046

119. Patel V, Rodrigues M, DeSouza N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: a study of mothers in Goa, India. Am J Psychiatry (2002) 159(1):43–7. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.43

120. Andajani-Sutjahjo S, Manderson L, Astbury J. Complex emotions, complex problems: understanding the experiences of perinatal depression among new mothers in urban Indonesia. Cult Med Psychiatry (2007) 31(1):101–22. doi:10.1007/s11013-006-9040-0

121. Abbasi M, Van den Akker O, Bewley C. Persian couples’ experiences of depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life in the pre- and perinatal period. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol (2014) 35(1):16–21. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2013.865722

122. Abdollahi F, Rohani S, Sazlina GS, Zarghami M, Azhar MZ, Lye MS, et al. Bio-psycho-socio-demographic and obstetric predictors of postpartum depression in pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci (2014) 8(2):11–21.

123. Goshtasebi A, Alizadeh M, Gandevani SB. Association between maternal anaemia and postpartum depression in an urban sample of pregnant women in Iran. J Health Popul Nutr (2013) 31(3):398–402. doi:10.3329/jhpn.v31i3.16832

124. Kheirabadi GR, Maracy MR. Perinatal depression in a cohort study on Iranian women. J Res Med Sci (2010) 15(1):41–9.

125. Montazeri A, Torkan B, Omidvari S. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. BMC Psychiatry (2007) 7:11. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-7-11

126. Ahmed HM, Alalaf SK, Al-Tawil NG. Screening for postpartum depression using Kurdish version of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Arch Gynecol Obstet (2012) 285(5):1249–55. doi:10.1007/s00404-011-2165-6

127. Crotty F, Sheehan J. Prevalence and detection of postnatal depression in an Irish community sample. Ir J Psychol Med (2004) 21(4):117–21. doi:10.1017/S0790966700008533

128. Cryan E, Keogh F, Connolly E, Cody S, Quinlan A, Daly I. Depression among postnatal women in an urban Irish community. Ir J Psychol Med (2001) 18(1):5–10. doi:10.1017/S0790966700006145

129. Lane A, Keville R, Morris M, Kinsella A, Turner M, Barry S. Postnatal depression and elation among mothers and their partners: prevalence and predictors. Br J Psychiatry (1997) 171(6):550–5. doi:10.1192/bjp.171.6.550

130. Leahy-Warren P, McCarthy G, Corcoran P. First-time mothers: social support, maternal parental self-efficacy and postnatal depression. J Clin Nurs (2012) 21(3–4):388–97. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03701.x

131. Alfayumi-Zeadna S, Kaufman-Shriqui V, Zeadna A, Lauden A, Shoham-Vardi I. The association between sociodemographic characteristics and postpartum depression symptoms among Arab-Bedouin women in southern Israel. Depress Anxiety (2015) 32(2):120–8. doi:10.1002/da.22290

132. Bloch M, Rotenberg N, Koren D, Klein E. Risk factors associated with the development of postpartum mood disorders. J Affect Disord (2005) 88(1):9–18. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.04.007

133. Bloch M, Rotenberg N, Koren D, Klein E. Risk factors for early postpartum depressive symptoms. Gen Hosp Psychiatry (2006) 28(1):3–8. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.08.006

134. Dankner R, Goldberg RP, Fisch RZ, Crum RM. Cultural elements of postpartum depression. A study of 327 Jewish Jerusalem women. J Reprod Med (2000) 45(2):97–104.

135. Eilat-Tsanani S, Merom A, Romano S, Reshef A, Lavi I, Tabenkin H. The effect of postpartum depression on women’s consultations with physicians. Isr Med Assoc J (2006) 8(6):406–10.

136. Fisch RZ, Tadmor OP, Dankner R, Diamant YZ. Postnatal depression: a prospective study of its prevalence, incidence and psychosocial determinants in an Israeli sample. J Obstet Gynaecol Res (1997) 23(6):547–54. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.1997.tb00885.x

137. Glasser S, Barell V, Shoham A, Ziv A, Boyko V, Lusky A, et al. Prospective study of postpartum depression in an Israeli cohort: prevalence, incidence and demographic risk factors. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol (1998) 19(3):155–64. doi:10.3109/01674829809025693

138. Glasser S, Stoski E, Kneler V, Magnezi R. Postpartum depression among Israeli Bedouin women. Arch Womens Ment Health (2011) 14(3):203–8. doi:10.1007/s00737-011-0216-4

139. Benvenuti P, Ferrara M, Niccolai C, Valoriani V, Cox JL. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation for an Italian sample. J Affect Disord (1999) 53(2):137–41. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00102-5

140. Carpiniello B, Pariante CM, Serri F, Costa G, Carta MG. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in Italy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol (1997) 18(4):280–5. doi:10.3109/01674829709080700

141. Elisei S, Lucarini E, Murgia N, Ferranti L, Attademo L. Perinatal depression: a study of prevalence and of risk and protective factors. Psychiatr Danub (2013) 25(Suppl 2):S258–62.

142. Giardinelli L, Innocenti A, Benni L, Stefanini MC, Lino G, Lunardi C, et al. Depression and anxiety in perinatal period: prevalence and risk factors in an Italian sample. Arch Womens Ment Health (2012) 15(1):21–30. doi:10.1007/s00737-011-0249-8

143. Gorman LL, O’Hara MW, Figueiredo B, Hayes S, Jacquemain F, Kammerer MH, et al. Adaptation of the Structured Clinical interview for DSM-IV Disorders for assessing depression in women during pregnancy and post-partum across countries and cultures. Br J Psychiatry (2004) 184(Suppl 46):s17–23. doi:10.1192/bjp.184.46.s17

144. Grussu P, Quatraro RM. Prevalence and risk factors for a high level of postnatal depression symptomatology in Italian women: a sample drawn from ante-natal classes. Eur Psychiatry (2009) 24(5):327–33. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.01.006

145. Mauri M, Oppo A, Montagnani MS, Borri C, Banti S, Camilleri V, et al. Beyond “postpartum depressions:” Specific anxiety diagnoses during pregnancy predict different outcomes: results from PND-ReScU. J Affect Disord (2010) 127(1):177–84. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.015

146. Oppo A, Mauri M, Ramacciotti D, Camilleri V, Banti S, Borri C, et al. Risk factors for postpartum depression: the role of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised (PDPI-R): results from the Perinatal Depression-Research & Screening Unit (PNDReScU) study. Arch Womens Ment Health (2009) 12(4):239–49. doi:10.1007/s00737-009-0071-8

147. Matsumoto K, Tsuchiya KJ, Itoh H, Kanayama N, Suda S, Matsuzaki H, et al. Age-specific 3-month cumulative incidence of postpartum depression: the Hamamatsu Birth Cohort (HBC) Study. J Affect Disord (2011) 133(3):607–10. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.024

148. Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Tanaka K, Yokoyama T, Ohya Y, Fukushima W, et al. Dietary folate and vitamins B12, B6, and B2 intake and the risk of postpartum depression in Japan: the Osaka maternal and child health study. J Affect Disord (2006) 96(1–2):133–8. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.024

149. Nishigori H, Sugawara J, Obara T, Nishigori T, Sato K, Sugiyama T, et al. Surveys of postpartum depression in Miyagi, Japan, after the great east Japan earthquake. Arch Womens Ment Health (2014) 17(6):579–81. doi:10.1007/s00737-014-0459-y

150. Nishizono-Maher A, Kishimoto J, Yoshida H, Urayama K, Miyato M, Otsuka Y, et al. The role of self-report questionnaire in the screening of postnatal depression a community sample survey in central Tokyo. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2004) 39(3):185–90. doi:10.1007/s00127-004-0727-7

151. Ohoka H, Koide T, Goto S, Murase S, Kanai A, Masuda T, et al. Effects of maternal depressive symptomatology during pregnancy and the postpartum period on infant-mother attachment. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2014) 68(8):631–9. doi:10.1111/pcn.12171

152. Shimizu A, Nishiumi H, Okumura Y, Watanabe K. Depressive symptoms and changes in physiological and social factors 1 week to 4 months postpartum in Japan. J Affect Disord (2015) 179:175–82. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.036

153. Tamaki R, Murata M, Okano T. Risk factors for postpartum depression in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (1997) 51(3):93–8. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.1997.tb02368.x

154. Ueda M, Yamashita H, Yoshida K. Impact of infant health problems on postnatal depression: pilot study to evaluate a health visiting system. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2006) 60(2):182–9. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01484.x

155. Watanabe M, Wada K, Sakata Y, Aratake Y, Kato N, Ohta H, et al. Maternity blues as predictor of postpartum depression: a prospective cohort study among Japanese women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol (2008) 29(3):211–7. doi:10.1080/01674820801990577

156. Yamashita H, Yoshida K, Nakano H, Tashiro N. Postnatal depression in Japanese women: detecting the early onset of postnatal depression by closely monitoring the postpartum mood. J Affect Disord (2000) 58(2):145–54. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00108-1

157. Bang KS. Infants’ temperament and health problems according to maternal postpartum depression. J Korean Acad Nurs (2011) 41(4):444–50. doi:10.4040/jkan.2011.41.4.444

158. Kim JJ, Gordon TJ, La Porte LM, Adams M, Kuendig JM, Silver RK. The utility of maternal depression screening in the third trimester. Am J Obstet Gynecol (2008) 199(5): 509.e1–5. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.018

159. Chaaya M, Campbell OM, El Kak F, Shaar D, Harb H, Kaddour A. Postpartum depression: prevalence and determinants in Lebanon. Arch Womens Ment Health (2002) 5(2):65–72. doi:10.1007/s00737-002-0140-8

160. El-Hachem C, Rohayem J, Khalil RB, Richa S, Kesrouani A, Gemayel R, et al. Early identification of women at risk of postpartum depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in a sample of Lebanese women. BioMed Cent Psychiatry (2014) 14(1):1–16. doi:10.1186/s12888-014-0242-7

161. Dow A, Dube Q, Pence BW, Van Rie A. Postpartum depression and HIV infection among women in Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999) 65(3):359–65. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000050

162. Azidah AK, Shaiful BI, Rusli N, Jamil MY. Postnatal depression and socio-cultural practices among postnatal mothers in Kota Bahru, Kelantan, Malaysia. Med J Malays (2006) 61(1):76–83.

163. Kadir AA, Daud MN, Yaacob MJ, Hussain NH. Relationship between obstetric risk factors and postnatal depression in Malaysian women. Int Med J (2009) 16(2):101–6.

164. Kit LK, Janet G, Jegasothy R. Incidence of postnatal depression in Malaysian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res (1997) 23(1):85–9. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.1997.tb00811.x

165. Yusuff AS, Tang L, Binns CW, Lee AH. Prevalence and risk factors for postnatal depression in Sabah, Malaysia: a cohort study. Women Birth (2015) 28(1):25–9. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2014.11.002

166. Felice E, Saliba J, Grech V, Cox J. Prevalence rates and psychosocial characteristics associated with depression in pregnancy and postpartum in Maltese women. J Affect Disord (2004) 82(2):297–301. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2003.11.011

167. deCastro F, Hinojosa-Ayala N, Hernandez-Prado B. Risk and protective factors associated with postnatal depression in Mexican adolescents. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol (2011) 32(4):210–7. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2011.626543

168. Flores-Quijano ME, Córdova A, Contreras-Ramírez V, Farias-Hernández L, Cruz Tolentino M, Casanueva E. Risk for postpartum depression, breastfeeding practices, and mammary gland permeability. J Hum Lact (2008) 24(1):50–7. doi:10.1177/0890334407310587

169. Agoub M, Moussaoui D, Battas O. Prevalence of postpartum depression in a Moroccan sample. Arch Womens Ment Health (2005) 8(1):37–43. doi:10.1007/s00737-005-0069-9

170. Alami KM, Kadri N, Berrada S. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth in a Moroccan sample. Arch Womens Ment Health (2006) 9(6):343–6. doi:10.1007/s00737-006-0154-8

171. Dørheim Ho-Yen S, Tschudi Bondevik G, Eberhard-Gran M, Bjorvatn B. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in the postnatal period in Lalitpur district, Nepal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand (2006) 85(10):1186–92. doi:10.1080/00016340600753158

172. Regmi S, Sligl W, Carter D, Grut W, Seear M. A controlled study of postpartum depression among Nepalese women: validation of the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale in Kathmandu. Trop Med Int Health (2002) 7(4):378–82. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00866.x

173. Blom EA, Jansen PW, Verhulst FC, Hofman A, Raat H, Jaddoe VV, et al. Perinatal complications increase the risk of postpartum depression: the generation R Study. BJOG (2010) 117(11):1390–8. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02660.x

174. Verkerk GJ, Denollet J, Van Heck GL, Van Son MJ, Pop VJ. Patient preference for counselling predicts postpartum depression: a prospective 1-year follow up study in high-risk women. J Affect Disord (2004) 83(1):43–8. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2004.04.011

175. Abbott MW, Williams MM. Postnatal depressive symptoms among Pacific mothers in Auckland: prevalence and risk factors. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2006) 40(3):230–8. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01779.x

176. Holt WJ. The detection of postnatal depression in general practice using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. N Z Med J (1995) 108(994):57–9.

177. McGill H, Burrows VL, Holland LA, Langer HJ, Sweet MA. Postnatal depression: a Christchurch study. N Z Med J (1995) 108(999):162–5.

178. Webster ML, Thompson JD, Mitchell EA, Werry JS. Postnatal depression in a community cohort. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (1994) 28(1):42–9. doi:10.3109/00048679409075844

179. Abiodun OA. Postnatal depression in primary care populations in Nigeria. Gen Hosp Psychiatry (2006) 28(2):133–6. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.11.002

180. Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Dada AO, Fasoto OO. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening tool for depression in late pregnancy among Nigerian women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol (2006) 27(4):267–72. doi:10.1080/01674820600915478

181. Adewuya AO, Fatoye FO, Ola BA, Ijaodola OR, Ibigbami SM. Sociodemographic and obstetric risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms in Nigerian women. J Psychiatr Pract (2015) 11(5):353–8. doi:10.1097/00131746-200509000-00009

182. Bakare MO, Okoye JO, Obindo JT. Introducing depression and developmental screenings into the National Programme on Immunization (NPI) in southeast Nigeria: an experimental cross-sectional assessment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry (2014) 36(1):105–12. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.09.005

183. Dørheim SK, Bondevik GT, Eberhard-Gran M, Bjorvatn B. Sleep and depression in postpartum women: a population-based study. Sleep (2009) 32(7):847–55. doi:10.1093/sleep/32.7.847

184. Dørheim SK, Bjorvatn B, Eberhard-Gran M. Can insomnia in pregnancy predict postpartum depression? A longitudinal, population-based study. PLoS One (2014) 9(4):e94674. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094674

185. Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, Opjordsmoen S, Samuelsen SO. Review of validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2001) 104(4):243–9. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00187.x

186. Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, Samuelsen SO, Opjordsmoen S. Depression in postpartum and non-postpartum women: prevalence and risk factors. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2002) 106(6):426–33. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02408.x

187. Eberhard-Gran M, Tambs K, Opjordsmoen S, Skrondal A, Eskild A. Depression during pregnancy and after delivery: a repeated measurement study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol (2004) 25(1):15–21. doi:10.1080/01674820410001737405

188. Glavin K, Smith L, Sørum R. Prevalence of postpartum depression in two municipalities in Norway. Scand J Caring Sci (2009) 23(4):705–10. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00667.x

189. Haga SM, Ulleberg P, Slinning K, Kraft P, Steen TB, Staff A. A longitudinal study of postpartum depressive symptoms: multilevel growth curve analyses of emotion regulation strategies, breastfeeding self-efficacy, and social support. Arch Womens Ment Health (2012) 15(3):175–84. doi:10.1007/s00737-012-0274-2

190. Markhus MW, Skotheim S, Graff IE, Frøyland L, Braarud HC, Stormark KM, et al. Low omega-3 index in pregnancy is a possible biological risk factor for postpartum depression. PLoS One (2013) 8:7. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067617

191. Nordeng H, Hansen C, Garthus-Niegel S, Eberhard-Gran M. Fear of childbirth, mental health, and medication use during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health (2012) 15(3):203–9. doi:10.1007/s00737-012-0278-y

192. Ahmad I, Khan M. Risk factors associated with post-natal depression in Pakistani women. Pak J Soc Clin Psychol (2005) 3:41–50. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1074-3

193. Husain N, Bevc I, Husain M, Chaudhry IB, Atif N, Rahman A. Prevalence and social correlates of postnatal depression in a low income country. Arch Womens Ment Health (2006) 9(4):197–202. doi:10.1007/s00737-006-0129-9

194. Ayoub KA. Prevalence of Postpartum Depression among Recently Delivering Mothers in Nablus District and Its Associated Factors (Unpublished Master’s Thesis). Nablus, Palestine: An-Najah National University (2014).

195. Dudek D, Jaeschke R, Siwek M, Maczka G, Topór-Madry R, Rybakowski J. Postpartum depression: identifying associations with bipolarity and personality traits. Preliminary results from a cross-sectional study in Poland. Psychiatry Res (2014) 215(1):69–74. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2013.10.013

196. Augusto A, Kumar R, Calheiros JM, Matos E, Figueiredo E. Post-natal depression in an urban area of Portugal: comparison of childbearing women and matched controls. Psychol Med (1996) 26(1):135–41. doi:10.1017/S0033291700033778

197. Figueiredo B, Conde A. Anxiety and depression in women and men from early pregnancy to 3-months postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health (2011) 14(3):247–55. doi:10.1007/s00737-011-0217-3

198. Figueiredo B, Costa R. Mother’s stress, mood and emotional involvement with the infant: 3 months before and 3 months after childbirth. Arch Womens Ment Health (2009) 12(3):143–53. doi:10.1007/s00737-009-0059-4

199. Figueiredo B, Pacheco A, Costa R. Depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period in adolescent and adult Portuguese mothers. Arch Womens Ment Health (2007) 10(3):103–9. doi:10.1007/s00737-007-0178-8

200. Chee CI, Lee DS, Chong YS, Tan LK, Ng TR, Fones CL. Confinement and other psychosocial factors in perinatal depression: a transcultural study in Singapore. J Affect Disord (2005) 89(1–3):157–66. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.09.004

201. Kok LP, Chan PS, Ratnam SS. Postnatal depression in Singapore women. Singapore Med J (1994) 35(1):33–5.

202. Lawrie TA, Hofmeyr GJ, De Jager M, Berk M, Paiker J, Viljoen E. A double-blind randomised placebo controlled trial of postnatal norethisterone enanthate: the effect on postnatal depression and serum hormones. Br J Obstet Gynaecol (1998) 105(10):1082–90. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09940.x

203. Lawrie TA, Hofmeyr GJ, De Jager M, Berk M. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale on a cohort of South African women. S Afr Med J (1998) 88(10):1340–4.

204. Escribà-Agüir V, Artazcoz L. Gender differences in postpartum depression: a longitudinal cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health (2011) 65(4):320–6. doi:10.1136/jech.2008.085894

205. Garcia-Esteve L, Ascaso C, Ojuel J, Navarro P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Spanish mothers. J Affect Disord (2003) 75(1):71–6. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00020-4

206. Sebastián Romero E, Mas Lodo N, Martín Blázquez M, Raja Casillas MI, Izquierdo Zamarriego MJ, Valles Fernández N, et al. Depresión postparto en el área de salud de Toledo [Postpartum depression in the health area of Toledo]. Atención primaria (1992) 24(4):215–9.

207. Agnafors S, Sydsjö G, deKeyser L, Svedin CG. Symptoms of depression postpartum and 12 years later-associations to child mental health at 12 years of age. Matern Child Health J (2013) 17(3):405–14. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-0985-z

208. Bågedahl-Strindlund M, Monsen Börjesson K. Postnatal depression: a hidden illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand (1998) 98(4):272–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10083.x

209. Josefsson A, Berg G, Nordin C, Sydsjö G. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in late pregnancy and postpartum. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand (2001) 80(3):251–5. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.080003251.x

210. Lundh W, Gyllang C. Use of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in some Swedish child health care centres. Scand J Caring Sci (1993) 7(3):149–54. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.1993.tb00190.x

211. Rubertsson C, Wickberg B, Gustavsson P, Rådestad I. Depressive symptoms in early pregnancy, two months and one year postpartum-prevalence and psychosocial risk factors in a national Swedish sample. Arch Womens Ment Health (2005) 8(2):97–104. doi:10.1007/s00737-005-0078-8

212. Seimyr L, Edhborg M, Lundh W, Sjögren B. In the shadow of maternal depressed mood: experiences of parenthood during the first year after childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol (2004) 25(1):23–34. doi:10.1080/01674820410001737414

213. Sylvén SM, Ekselius L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Skalkidou A. Premenstrual syndrome and dysphoric disorder as risk factors for postpartum depression. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand (2013) 92(2):178–84. doi:10.1111/aogs.12041

214. Wickberg B, Hwang CP. Counselling of postnatal depression: a controlled study on a population based Swedish sample. J Affect Disord (1996) 39(3):209–16. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(96)00034-1

215. Burgut FT, Bener A, Ghuloum S, Sheikh J. A study of postpartum depression and maternal risk factors in Qatar. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol (2013) 34(2):90–7. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2013.786036

216. Alharbi AA, Abdulghani HM. Risk factors associated with postpartum depression in the Saudi population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat (2014) 10:311–6. doi:10.2147/NDT.S57556

217. Al-Modayfer O, Alatiq Y, Khair O, Abdelkawi S. Postpartum depression and related risk factors among Saudi females. Int J Cult Ment Health (2015) 8(3):316–24. doi:10.1080/17542863.2014.999691

218. Gürber S, Bielinski-Blattmann D, Lemola S, Jaussi C, von Wyl A, Surbek D, et al. Maternal mental health in the first 3-week postpartum: the impact of caregiver support and the subjective experience of childbirth–a longitudinal path model. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol (2012) 33(4):176–84. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2012.730584

219. Righetti-Veltema M, Conne-Perréard E, Bousquet A, Manzano J. Risk factors and predictive signs of postpartum depression. J Affect Disord (1998) 49(3):167–80. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00110-9

220. Chen HH, Hwang FM, Tai CJ, Chien LY. The interrelationships among acculturation, social support, and postpartum depression symptoms among marriage-based immigrant women in Taiwan: a cohort study. J Immigr Minor Health (2013) 15(1):17–23. doi:10.1007/s10903-012-9697-0

221. Chien LY, Tai CJ, Yeh MC. Domestic decision-making power, social support, and postpartum depression symptoms among immigrant and native women in Taiwan. Nurs Res (2012) 61(2):103–10. doi:10.1097/NNR.0b013e31824482b6

222. Heh S, Coombes L, Bartlett H. The association between depressive symptoms and social support in Taiwanese women during the month. Int J Nurs Stud (2004) 41(5):573–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.01.003

223. Heh S, Huang L, Ho S, Fu Y, Wang L. Effectiveness of an exercise support program in reducing the severity of postnatal depression in Taiwanese women. Birth (2008) 35(1):60–5. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00192

224. Huang YC, Mathers NJ. A comparison of sexual satisfaction and post-natal depression in the UK and Taiwan. Int Nurs Rev (2006) 53(3):197–204. doi:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2006.00459.x

225. Huang YC, Mathers NJ. Postnatal depression and the experience of South Asian marriage migrant women in Taiwan: survey and semi-structured interview study. Int J Nurs Stud (2008) 45(6):924–31. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.02.006

226. Lee SH, Liu LC, Kuo PC, Lee MS. Postpartum depression and correlated factors in women who received in vitro fertilization treatment. J Midwifery Womens Health (2011) 56(4):347–52. doi:10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00033.x