- 1Psychiatry Department, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

- 2College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia

- 3School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences and Medicine, Wolaita Sodo University, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia

Background: Alcohol is attributable to many diseases and injury-related health conditions, and it is the fifth leading risk factor of premature death globally. Hence, the objective of this study was to assess the proportion and associated factors of problematic alcohol use among University students.

Material and methods: Cross-sectional study was conducted among 725 randomly selected University students from November to December 2015. Data were collected by self-administered questionnaire, and problematic alcohol use was assessed by Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test. Chi-square test was used to show association of problematic use and each variable and major predicators was identified using logistic regression with 95% confidence interval (CI); and variables with p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

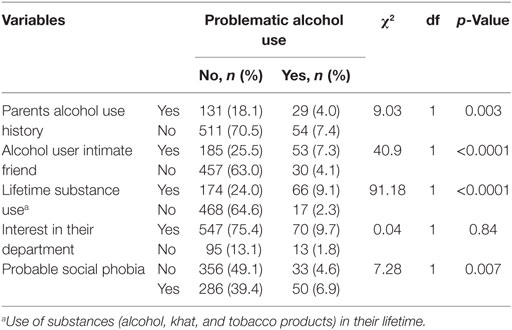

Results: About 83 (11.4%) of the samples were problematic alcohol users of which 6.8% had medium level problems and 4.6% had high level problems. Significantly associated variables with problematic alcohol use among students were presence of social phobia (AOR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.0, 2.8), lifetime use of any substance (AOR = 6.9, 95% CI: 3.8, 12.7), higher score in students cumulative grade point average (AOR = 0.6, 95% CI: 0.4, 0.9), and having intimate friend who use alcohol (AOR = 2.2, 95% CI: 1.3, 3.8).

Conclusion: Problematic alcohol use among university students was common and associated with social phobia, poor academic achievement, lifetime use of any substance, and peer pressure. Strong legislative control of alcohol in universities is important to reduce the burden of alcohol.

Introduction

Alcohol is the third leading preventable risk factor for the global burden of disease and responsible for 3.3 million deaths (5.9% of all global deaths). In 2012, World Health Organization reported that 7.6 and 4% of deaths were attributable to alcohol among males and females, respectively. Alcohol contributes to over 200 diseases and injury-related health conditions, mostly alcohol dependence, liver cirrhosis, cancers, and injuries. Alcohol misuse is the fifth leading risk factor of premature death globally; among people between the ages of 15 and 49 years, it is the first leading cause (1, 2).

Alcohol misuse was also reported as a strong predictor of students’ mental health in which, it was attributable for increased depressive symptoms accompanied with drinking to cope (3, 4), attempted suicide and self-harm behaviors (5, 6), and aggressive behaviors (7). Alcohol use was also associated with the use of novel psychoactive substances, a new trend exacerbated by the presence of alcohol (8). Moreover, students with problematic alcohol use are less likely to seek professional help for their mental health problem (9). Problematic alcohol use contributes to a significant proportion of students’ engagement in risky sexual behavior (10), poorer executive functions (11), and poor academic achievement (12–14).

The prevalence of problematic alcohol use in university students was widely variable and generally higher in developed countries (15). Students’ alcohol use in general ranged from 22 in Ethiopia to 94% in Ireland; and problematic alcohol use ranged from 2.5 in Germany to 53% in Ireland (15–18). In developed countries, on average, each student had 1.7 drinks daily with about three episodes abusive drinking per month and about 10% of probable alcohol dependence (18, 19). Alcohol was also common in Ethiopian university students in which 31% of students in Addis Ababa University and about 50% in Haramaya University reported current alcohol use (20, 21). Students consumed alcohol for the reason of social gathering and as the means of social interaction influenced by their peers (16, 19, 22). Many predictors of problematic alcohol use have been identified previously. Sex, socioeconomic status, living in dormitory with higher number of roommates, cultural norms about alcohol, and having families who use substance were the commonly mentioned factors affecting students’ problematic alcohol use (5, 16, 23, 24).

Problematic alcohol use by university students is an important public health issue due to its multiple and wide range of effects on physical, psychosocial, and mental health. Despite some researchers tried to show the prevalence of alcohol use among university students in Ethiopia, there is little/no evidence on how many of those students engaged in problematic alcohol use and probable alcohol dependence. Therefore, it is very important to conduct surveys on students’ alcohol use problem by including further possible predictors. Hence, the purpose of this study was to assess the level of problematic alcohol use and predictor factors among university students.

Materials and Methods

Cross-sectional study was conducted among 725 randomly selected Wolaita Sodo University regular students from November to December 2015. Wolaita Sodo University is one the government owned Universities in southern Ethiopia. Regular students enrolled in the University in 2015/16 academic year were included in the study.

Problematic alcohol use was the outcome variable; and the independent variables were sociodemographic variables (sex, age, marital status, religion, residence, monthly pocket money, and ethnicity), substance use related variables (having intimate friend who use alcohol, parents alcohol use status, and lifetime substance use), and other variables (students’ interest in their field of study, any disabling or chronic illness, parenting style, and academic performance).

Data were collected by pretested self-administered questionnaire by trained data collectors and supervisors. Problematic alcohol use was assessed by Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), which was developed by World Health Organization to be used in culturally diversified settings. AUDIT has 10 items in which the first 8 items are Likert scale scored from 0 to 4 and the last two items are scored as 0, 2, and 4. Total score of 8 or more was considered as positive for problematic alcohol use. AUDIT scores in the range of 8–15 represented low level of alcohol problems, whereas scores of 16 and above represented high level of alcohol problems; and AUDIT scores of 20 and above clearly showed alcohol dependence (25). Social phobia was assessed by using the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN), which was developed by Connor et al. It was 17 items self-rating tool scored from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) and the sum score ranged from 0 to 68 (26). A student with a score of 20 and above on SPIN were considered as having social phobia. The other variables were assessed by structured questionnaire developed by reviewing different literatures; and the responses were based on the students report.

Data were entered in to EPI info software version 3.5.3 and then transported to SPSS version 20 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the result with respect to problem alcohol use with corresponding chi-square and p-value. Logistic regression was used to analyze the association between dependent and independent variables. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to show the strength of the associations, and variables with p-value of less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Ethical clearance was obtained from institutional review board of Wolaita Sodo University. The purpose of the study was fully explained for all participants in order to give them an informed choice to participate. Confidentiality was maintained by anonymous questionnaire and written informed consent was obtained from each participants.

Results

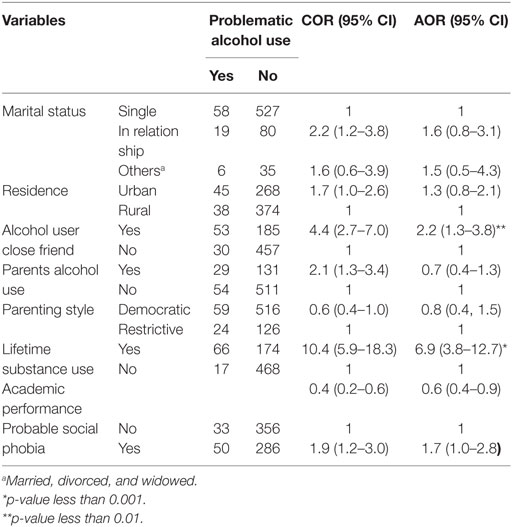

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents

From the total of 740 sample size, 725 participants were included in the study with the response rate of 97.97%. The mean age of the participants was 21.15 years (SD ± 1.7) and the reported monthly pocket money of the students ranged from 50 to 3,600 Ethiopian birr with the median value of 300 Ethiopian birr (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants with respect to problematic alcohol use (n = 725).

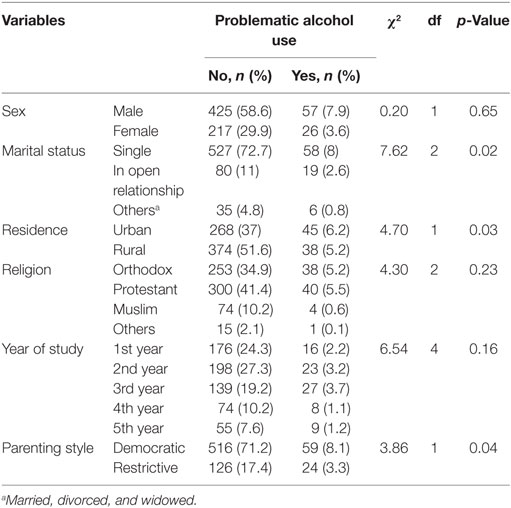

Substance Use and Related Characteristics of the Participants

From the total participants, 160 students had parents with alcohol use history and 29 (4%) of them were screened positive for alcohol use problem. Lifetime substance use (alcohol, tobacco products, or khat) was also reported by 240 students (Table 2).

Table 2. Substance use and related characteristics of the participants with respect to problematic alcohol use (n = 725).

Prevalence and Associated Factors of Problematic Alcohol Use

The overall prevalence of problematic alcohol use among university students was 11.4% (95% CI: 9.1, 13.7) with 6.8% medium level problematic alcohol use and 4.6% high level problematic alcohol use. The occurrence of problematic alcohol use in male to female ratio was about 2:1. Variables that were significantly associated with problematic alcohol use of students were having alcohol user intimate friend (AOR = 2.2, 95% CI: 1.3, 3.8), ever use of substance (AOR = 6.9, 95% CI: 3.8, 12.7), academic achievement (grade point) (AOR = 0.6, 95% CI: 0.4, 0.9), and probable social phobia (AOR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.0, 2.8) (Table 3).

Discussion

Approximately 1 from 10 students had problematic alcohol use and 4.6% students were in high level problematic alcohol use, which was indicative for alcohol dependence. The finding was consistent with the Belgian University students in which problematic alcohol use was 14 and 3.6% probable dependence (14). It was also in line with the findings of international study for Bulgaria 9%, France 8.5%, and Hungary 8% (15). However, our finding was generally lower as compared with many other countries’ problematic alcohol use among college students. For instance, 47.6% of students in Spain were binge drinkers (27), 61% of students in England were positive for AUDIT scores (18), 40–45% of American college students were heavy drinkers (28), and South Africa 15% (15). The current finding was also much lower than the findings from Belgium 36.5%, Colombia 35%, Ireland 53%, and the study done in Italian young people in which binge drinking was reported by 67.6% of the participants (15, 29).

The main possible explanation for this difference might be the difference in socioeconomic status of the students. It was suggested by researchers that high socioeconomic status might increase the risk of problem alcohol use (15). Race was also another important explanation for the above discrepancy; the percentage of students who reported hazardous drinking was five times higher in whites than non-whites (18, 22, 28). Use of self-administered survey in the current study might also underestimate the prevalence of problematic alcohol use. On the other hand, the current finding was higher as compared with findings from Germany, Greece, Romania, and Italy in which students’ problem use of alcohol were 2.5–4.5% in those countries (15).

Peer pressure was an important predictor of problematic alcohol use in university students in which the odds of having problematic alcohol use among students who had alcohol user intimate friends were more than two times as compared with their counter parts. Direct or indirect encouragement from intimate friends was indicated as a major factor to be engaged in risk-taking behaviors. Students tend to drink more alcoholic beverages during social gatherings in the virtue of social interaction and high level of alcohol abuse was reported by students living in the dormitory with high density of roommates (19, 22, 30). In a Kenyan study, 75.1% of students admitted that they were introduced for substance abuse by their friends. Previous studies in Ethiopia also showed the influence of peers on students’ alcohol consumption; students whose friends consume alcohol were more likely to consume alcohol (16, 31).

Lifetime exposure for substances other than alcohol, like Khat and tobacco products was strongly and positively associated with students’ problematic alcohol use. Students who had ever used any substance other than alcohol were about seven times more likely to engage themselves in problematic alcohol use. This was supported by the study conducted in Ethiopia among medical students by which ever use of cigarette or khat was associated with current alcohol use (16). Having history of smoking was associated with higher risk of alcohol use disorder than who never smoked as implicated in previous studies (32). Individuals who used some kind of substance also engaged in further risk-taking behaviors like alcohol abuse and subsequent alcohol use disorder (10).

This research showed that high achievement in students’ academic performance was associated with low risk of problematic alcohol use. Alcohol abuse has significant effect on executive functions of an individual accompanied with blackouts, frequent injuries, less motivation in activities, and even moderate doses of alcohol use had risk of decreasing academic performance (11, 33). Even though there were some differences in male and female students (34), this finding was consistent with other studies conducted in different areas (13, 14, 35).

The other variable significantly associated with students problematic alcohol use in the current study was probable social phobia. Students who were screened positive for probable social phobia were 1.7 times more likely to have problematic alcohol use and this was supported by other studies in Nigeria and USA (36). This might be explained by the students’ tendency to use alcohol as self-medication to get away from their stress and fear (37–39).

Unlike other studies (16, 24, 31), sex, marital status, family history of substance use, and student’s origin of residence were not associated with problematic alcohol use. Even though the occurrence of problematic alcohol use in male to female ratio was 2:1, it was statistically not significant in the current finding.

Limitations of the Study

This study did not assess all possible associated substances and did not show the interaction effect of other substance use with problematic alcohol use. Since alcohol is a gateway drug, it is expected that students would also use other drugs in addition to alcohol. Even though we had tried to maintain privacy and encourage the participants to complete the real information, the result might be underestimated due to social desirability bias. The study also did not measure blood alcohol concentration of the participants, which would be very important to assess the current level of alcohol in the blood stream.

Conclusion

Significant proportion of students reported problematic alcohol use and was associated with peer pressure, lifetime substance use, poor academic performance, and probable social phobia. Developing preventive interventions focusing on risky behaviors and legislative control in the universities toward alcohol use problem is important. Further research is needed to indicate the combined effect of other substances to problematic alcohol use, and it would be also very important to assess depressive symptoms associated with alcohol.

Ethics Statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from institutional review board of Wolaita Sodo University. The purpose of the study was fully explained for all participants in order to give them an informed choice to participate. Confidentiality was maintained by anonymous questionnaire and written informed consent was obtained from each participants.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally for the whole process of this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Our grateful thank goes to the study participants for their genuine participation in this research and Wolaita Sodo University for financial support.

References

1. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (2012) 380(9859):2224–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61766-8

2. World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization (2014). 389 p.

3. Bravo AJ, Pearson MR, Henson JM. Drinking to cope with depressive symptoms and ruminative thinking: a multiple mediation model among college students. Subst Use Misuse (2017) 52(1):52–62. doi:10.1080/10826084.2016.1214151

4. Gonzalez VM, Reynolds B, Skewes MC. Role of impulsivity in the relationship between depression and alcohol problems among emerging adult college drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol (2011) 19(4):303–13. doi:10.1037/a0022720

5. Peltzer K, Pengpid S, Tepirou C. Associations of alcohol use with mental health and alcohol exposure among school-going students in Cambodia. Nagoya J Med Sci (2016) 78(4):415–22. doi:10.18999/nagjms.78.4.415

6. Toprak S, Cetin I, Guven T, Can G, Demircan C. Self-harm, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among college students. Psychiatry Res (2011) 187(1–2):140–4. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.09.009

7. Ali B, Ryan JS, Beck KH, Daughters SB. Trait aggression and problematic alcohol use among college students: the moderating effect of distress tolerance. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (2013) 37(12):2138–44. doi:10.1111/acer.12198

8. Martinotti G, Lupi M, Acciavatti T, Cinosi E, Santacroce R, Signorelli MS, et al. Novel psychoactive substances in young adults with and without psychiatric comorbidities. Biomed Res Int (2014) 2014:e815424. doi:10.1155/2014/815424

9. Hunt J, Eisenberg D. Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. J Adolesc Health (2010) 46(1):3–10. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.008

10. Kassa GM, Degu G, Yitayew M, Misganaw W, Muche M, Demelash T, et al. Risky sexual behaviors and associated factors among jiga high school and preparatory school students, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Int Sch Res Notices (2016) 2016:4315729. doi:10.1155/2016/4315729

11. Parada M, Corral M, Mota N, Crego A, Rodríguez Holguín S, Cadaveira F. Executive functioning and alcohol binge drinking in university students. Addict Behav (2012) 37(2):167–72. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.015

12. Mazur J, Tabak I, Dzielska A, Waż K, Oblacińska A. The relationship between multiple substance use, perceived academic achievements, and selected socio-demographic factors in a polish adolescent sample. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2016) 13(12). doi:10.3390/ijerph13121264

13. Singleton RA, Wolfson AR. Alcohol consumption, sleep, and academic performance among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs (2009) 70(3):355–63. doi:10.15288/jsad.2009.70.355

14. Aertgeerts B, Buntinx F. The relation between alcohol abuse or dependence and academic performance in first-year college students. J Adolesc Health (2002) 31(3):223–5. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00362-2

15. Dantzer C, Wardle J, Fuller R, Pampalone SZ, Steptoe A. International study of heavy drinking: attitudes and sociodemographic factors in university students. J Am Coll Health (2006) 55(2):83–9. doi:10.3200/jach.55.2.83-90

16. Deressa W, Azazh A. Substance use and its predictors among undergraduate medical students of Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health (2011) 11:660. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-660

17. Atwoli L, Mungla PA, Ndung’u MN, Kinoti KC, Ogot EM. Prevalence of substance use among college students in Eldoret, western Kenya. BMC Psychiatry (2011) 11:34. doi:10.1186/1471-244x-11-34

18. Heather N, Partington S, Partington E, Longstaff F, Allsop S, Jankowski M, et al. Alcohol use disorders and hazardous drinking among undergraduates at English universities. Alcohol Alcohol (2011) 46(3):270–7. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agr024

19. Lorant V, Nicaise P, Soto VE, d’Hoore W. Alcohol drinking among college students: college responsibility for personal troubles. BMC Public Health (2013) 13:615. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-615

20. Eshetu E, Gedif T. Prevalence of khat, cigarette and alcohol use among students of technology and pharmacy, Addis Ababa University. Ethiop Pharm J (2006) 24(2):116–24. doi:10.4314/epj.v24i2.35106

21. Tesfaye G, Derese A, Hambisa MT. Substance use and associated factors among university students in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Addict (2014) 2014:e969837. doi:10.1155/2014/969837

22. Wicki M, Kuntsche E, Gmel G. Drinking at European universities? A review of students’ alcohol use. Addict Behav (2010) 35(11):913–24. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.015

23. Dázio EMR, Zago MMF, Fava SMCL. Use of alcohol and other drugs among male university students and its meanings. Rev Esc Enferm USP (2016) 50(5):785–91. doi:10.1590/s0080-623420160000600011

24. Sahraian A, Sharifian M, Omidvar B, Javadpour A. Prevalence of substance abuse among the medical students in Southern Iran. Shiraz E Med J (2010) 11(4):198–202.

25. Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT—the Alcohol use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in Primary Care. 2nd edn. Geneva: World Health Organization (2001).

26. Connor KM, Davidson JRT, Churchill LE, Sherwood A, Weisler RH, Foa E. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN). Br J Psychiatry (2000) 176(4):379–86. doi:10.1192/bjp.176.4.379

27. Salas-Gomez D, Fernandez-Gorgojo M, Pozueta A, Diaz-Ceballos I, Lamarain M, Perez C, et al. Binge drinking in young university students is associated with alterations in executive functions related to their starting age. PLoS One (2016) 11(11). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166834

28. O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. J Stud Alcohol Suppl (2002) 14:23–39. doi:10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23

29. Martinotti G, Lupi M, Carlucci L, Santacroce R, Cinosi E, Acciavatti T, et al. Alcohol drinking patterns in young people: a survey-based study. J Health Psychol (2016) 21(9):1918–27. doi:10.1177/1359105316667795

30. Labrie JW, Hummer JF, Pedersen ER. Reasons for drinking in the college student context: the differential role and risk of the social motivator. J Stud Alcohol Drugs (2007) 68(3):393–8. doi:10.15288/jsad.2007.68.393

31. Kassa A, Wakgari N, Taddesse F. Determinants of alcohol use and khat chewing among Hawassa University students, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Afr Health Sci (2016) 16(3):822–30. doi:10.4314/ahs.v16i3.24

32. Grucza RA, Bierut LJ. Cigarette smoking and the risk for alcohol use disorders among adolescent drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (2006) 30(12):2046–54. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00255.x

33. Osain MW, Alekseevic VP. The effect of alcohol use on academic performance of university students. Ann Gen Psychiatry (2010) 9(Suppl 1):S215. doi:10.1186/1744-859x-9-s1-s215

34. Balsa AI, Giuliano LM, French MT. The effects of alcohol use on academic achievement in high school. Econ Educ Rev (2011) 30(1):1–15. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.06.015

35. El Ansari W, Stock C, Mills C. Is alcohol consumption associated with poor academic achievement in university students? Int J Prev Med (2013) 4(10):1175–88.

36. Schneier FR, Foose TE, Hasin DS, Heimberg RG, Liu SM, Grant BF, et al. Social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder co-morbidity in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med (2010) 40(6):977–88. doi:10.1017/S0033291709991231

37. Crum RM, Pratt LA. Risk of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in social phobia: a prospective analysis. Am J Psychiatry (2001) 158(10):1693–700. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1693

38. Olatunji BO, Cisler JM, Tolin DF. Quality of life in the anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev (2007) 27(5):572–81. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.015

Keywords: alcohol abuse, academic achievement, factors in students’ alcohol misuse, peer pressure, social phobia

Citation: Mekonen T, Fekadu W, Chane T and Bitew S (2017) Problematic Alcohol Use among University Students. Front. Psychiatry 8:86. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00086

Received: 01 March 2017; Accepted: 01 May 2017;

Published: 19 May 2017

Edited by:

Alain Dervaux, Centre Hospitalier Sainte-Anne, FranceReviewed by:

Giovanni Martinotti, University of Chieti-Pescara, ItalyMauro Ceccanti, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Copyright: © 2017 Mekonen, Fekadu, Chane and Bitew. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tesfa Mekonen, c21hcnRob3BlMUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Tesfa Mekonen

Tesfa Mekonen Wubalem Fekadu1

Wubalem Fekadu1 Shimelash Bitew

Shimelash Bitew