94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 02 April 2025

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 7 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2025.1556963

This article is part of the Research TopicRelations and Policymaking across EU Actors, National Governments, Parliaments and PartiesView all 3 articles

The growing role of cities in today’s globalized world is well known. As a result of their central position in many positive and negative global dynamics, cities are receiving more and more attention in various fields of study, including international relations (IR). In this context, COVID-19 was a turning point that once again demonstrated the international activism of cities, offering valid patterns of crisis response and management as an alternative to those of central governments. By observing this increased activism, this study has identified three main ways in which cities have developed international initiatives through unilateral, bilateral or multilateral actions, such as transnational city networks (TCNs), which have been one of the main tools used by cities to support or bypass central governments. Against this background, this study also sought to explore the main conditions that are associated with specific TCNs in providing solutions to the needs of their member cities in a time of crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. It did so through a qualitative comparative analysis focusing on some of the key characteristics of TCNs: top-down vs. bottom-up networks, relationships with IOs, mission and scope. The results indicate the conditions under which specific TCNs emerge as effective tools for international urban activism.

Cities are playing an increasingly important role on the international stage. Globalization has deprived states of some of their powers while creating opportunities for new actors to emerge. In this context, cities have indeed become more exposed to the global challenges posed by an interconnected world. At the same time, cities have managed to find ways to address these challenges and reaffirm their primary role as essential spaces for people to live and for innovative governance to develop. To understand the role of cities in international dynamics, we need a different framework, starting from our mental maps of international systems. We need to move from the classical state-centered map to a non-state-centered one.

The traditional mental map of international politics that we use to look at global dynamics usually sees the globe as a jigsaw puzzle of some 200 pieces, corresponding to the 193 states that are members of the United Nations. The state has been the focus of international relations for centuries, representing the unit of analysis of the international system (Marchetti and Menegazzi, 2022). This perspective is based on the state-centric worldview derived from the experience of the Westphalian system and the intellectual dominance of realism. Today, the world is indeed more complex, and there are new actors on the international stage. However, the nature of the international system was not state-centric even before the Westphalian system, when it was divided between large (supranational) empires. More recently, the mental map of international politics changed during the Cold War, when we essentially had only two tiles, the two blocs. From the late 1970s until the financial crisis of 2008, the puzzle had 5 or 8 pieces, corresponding to the member states of the G5 and G8 (Payne, 2008), and the dominance of the system was in the North of the world (the West), which no longer led the world through colonial control but through economic leadership and trade dynamics (Malik et al., 2024). Another interpretation of the puzzle of world politics can be found in Huntington’s civilizations, where we have a system of 9 macro-civilizations (Huntington, 1993). More recently, we have come to realize that the G8 countries are no longer able to govern the world alone, and the mind map has expanded to include several countries from the South. The G20 meetings have institutionalized this geostrategic enlargement. Today, much of the discussion is focused on the degree of polarity of the system: are we still living in a unipolar world under US hegemony? Or are we facing a bipolar system with China, or even a tripolar system with the EU playing a relevant role in the economic and normative spheres?

All these models still emphasize a state-centered approach. However, there is another model that we need to consider, especially if we want to understand the role of new actors such as cities: the model of a non-polar world (Avant et al., 2010; Haass, 2008; Hale et al., 2011; Khanna, 2011). The nonpolar world is one that is highly fused by globalization, where the realist state-centric exclusivity is rejected. From this perspective, the best conceptual map for understanding the global system is much more complex than the maps examined so far. On the one hand, the state is not a unitary act and its central role is declining in favor of a disaggregation into sub-state authorities with increasing transnational agency (Slaughter, 2009). Transnational governance networks are becoming more important, with courts, public authorities, interparliamentary assemblies and central banks all increasing their cooperation with international partners. Local authorities such as cities and regions are also following this pattern. On the other hand, the number and range of non-state actors (profit and non-profit) is also increasing. These new actors are demanding to be included in the international decision-making process. They are also acquiring authority, expertise and power to influence international affairs in parallel with and independent of state authorities. Cities and regions are among the most innovative non-state actors today.

As non-state actors, cities behave differently on the international stage than central governments. Cities promote unilateral actions to position themselves on the international stage by promoting their city branding or hosting international events such as sporting events and expos. Cities also act bilaterally by strengthening ties with foreign partners. Finally, similar to other non-state actors such as civil society organizations (CSOs), cities create and navigate transnational networks through which they often collaborate and actively lobby at various stages of global governance (Valeriani, 2021).

Focusing on the international activities of cities in the face of the pandemic, this paper shows how transnational city networks (TCNs) have responded to the pandemic. In doing so, the paper highlights how certain dynamics are consistent with the broader literature on networks and non-state actors, such as the role of international organizations in facilitating networked action and the ability/inability of TCNs to adapt to a new issue area they had not dealt with before. By TCNs the researchers refer here to formally and structurally organized networked organizations whose members are cities. In answering the research question, the paper first develops a typology of cities’ international actions, showing how different patterns of city diplomacy can be undertaken. At the same time, the in-depth focus on transnational city networks highlights the importance of complex systems of cooperation between cities and other international actors, such as international organizations (IOs).

The paper proceeds as follows. First, the paper provides a brief literature review on the role of cities in responding to the pandemic from an international relations (IR) perspective. Drawing on this literature, the paper then develops a taxonomy of city diplomacy in the context of the pandemic based on the literature review and observed global city initiatives during the pandemic. The paper then focuses on TCNs and examines the conditions under which specific network responses emerge. After reviewing the cases, the different responses to the crisis were categorized as sharing, self-production, and both. These three categories summarize the different response options available to TCNs. Sharing includes those practices in which TCNs use their platform to facilitate communication and knowledge sharing among members, self-production indicates a higher level of engagement in the production of in-house solutions such as guidelines and toolkits, and both include those cases of extreme activism in which all the different solutions were undertaken. The analysis takes into account several conditions drawn from the literature on transnational networks to examine whether the resources of the TCN, its focus on pre-pandemic health issues, and its partnership with an international organization played a role in defining the different solutions developed. This analysis is carried out through a small crisp set qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). The paper concludes by highlighting the main contributions, limitations and areas for future research.

The process of internationalization of cities highlighted in the previous section is challenged (like all other global dynamics) by the spread of COVID-19 in 2020. The pandemic has compromised the basic pillars of globalization and interconnectedness, limiting the exchange of people and goods. But if COVID-19 has confined people to their homes, has it confined governance to national or local borders?

COVID-19 has surely stressed the role of the state as a responder to health crises, and cities and local governments have found themselves dealing with problems that highly impacted urban areas with cities being at the core of the fight against the virus. COVID has highly impacted urban life, posing new economic challenges, deepening inequalities, and limiting and changing mobility (Acuto et al., 2020). In the early phases of the pandemic, 90% of reported cases have been registered in cities (United Nations, 2020). COVID had an impact on urban infrastructures such as public transport and sanitary hotspots, but also on attractions like theaters, museums, cultural events, and restaurants, cities’ vibrant economic and social life has seen a sudden stop. While central governments have been called to manage the economy with various policies, local authorities have been called to manage the more practical aspects of the pandemic, especially as life started to enter normality again. Cities have tackled the pandemic realizing a series of different initiatives.

In short, the COVID pandemic has represented a huge crisis for the urban dimension. Cities are not new to facing crisis as they usual are the playing field of critical events, either man or nature made. Cities are often at the center of war and conflicts making an urban approach essential to understand contemporary violence and peace (Kaldor and Sassen, 2020). Similarly, using cities as lenses has proven insightful to understand the dynamics related to financial crises (Fujita, 2013). Moreover, cities resilience to climate critical events and terrorist attacks has also been deeply addressed (Coaffee and Lee, 2017). Among the crises that cities are exposed to there are indeed pandemics.

While COVID has been a major pandemic, bringing challenges never seen in recent times, cities have been exposed to other outbreaks in the past. A study (Meagher et al., 2021) has reviewed the lessons learned from the various health crises that have happened in the last 20 years from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) to Zika. The authors show how the outbreaks of these diseases have shown the necessity to coordinate international resources to identify priorities, problems, and solutions (Meagher et al., 2021), p. 4. New organizations were created in the previous crises. From an urban perspective, the most relevant is indeed the WHO-promoted symposium on Cities and Public Health Crises from which it is possible to derive a series of lessons on the role of cities in facing the pandemic that include the by now well-known criticalities given by the population density and relative social distancing, the social dimension of restrictions and lockdowns and the importance of communication by the authorities (World Health Organization, 2008).

How cities have managed and are managing the pandemic is a matter addressed across various fields. Cities have been on the frontline in fighting the pandemic both as it emerged and as it became part of the everyday life of many of their citizens. As the first front in the fighting of the contagion, cities have been centers for the management of the ills, the supply of emergency goods, and the implementation of all those measures needed to tackle the criticalities brought about by COVID-19. Around the world, during the pandemic, cities have undergone changes in their labor markets, housing policies, transport management and urban planning projects (Baum et al., 2022).

With its local and global externalities, such as travel restrictions and social distancing, and the multilevel mobilization of governance instruments, from international organizations to local authorities, the global COVID-19 pandemic is a perfect case study to understand the international responses of cities to the global crisis. The internationalization of cities is often seen as a dimension to be developed in times of peace in order to promote development and economic opportunities for local authorities and their citizens. The question is therefore how these strategies are used during crises such as the COVID-19 outbreak. Particularly in contrast to unilateral and bilateral actions, multilateral actions inherently possess a higher level of complexity given the interactions of multiple actors and the relationship with other international actors such as international organizations, manifesting a unique system that links the global with the local. How do these systems respond in times of crisis?

To answer this question, the paper starts with a review of the basic international strategies of cities, based on which a taxonomy is developed to distinguish between the three dimensions of international action of cities: unilateral, bilateral and multilateral. As the analysis will show, this typology helps to differentiate core aspects of cities’ responses, such as their interactions with international organizations or their propensity to build new relationships with cities.

The literature on the international activism of cities has some solid foundations, although it leaves room for further development. To understand the international behavior of cities during the pandemic, it is relevant to review the core features of the debate on city internationalism and diplomacy.

The concept of city diplomacy recognizes that cities are not only places in the world economy but that they also have a political role (Marchetti, 2021). Cities actively engage to develop and pursue specific interests and strategies (Barber, 2013); they cooperate to address common issues, and they contribute to setting the international agenda. Cities have an important role in the monitoring phase of the law-making process both nationally, regionally, and internationally. Therefore, city diplomacy summarizes the active role of cities in navigating the diffused streams of global governance.

The international dimension of cities, in terms of strategies implemented at the local level to engage with global dynamics, is a subject that is receiving more and more attention in international relations literature. Various approaches look at cities in these terms, from cities’ increasing role as international actors from a political economy perspective (Curtis, 2014) to a more detailed understanding of their networked actions (Acuto, 2013). The engagement of cities in international dynamics is also proven to happen under certain conditions such as resource availability, decentralization/local autonomy, and a political culture that favors international projects of local entities (Marchetti, 2021).

City diplomacy is the expression of the desire of citizens to have new points of access to global affairs. City diplomacy is not only an opportunity to strengthen relations with foreign counterparts, but also a tool to obtain benefits. Through internationalization strategies that include upgraded organizational forms, redirected resources, improved brand strategies, and increased soft power, cities can have a stronger impact on the international agenda. Through city diplomacy, cities can better engage with the different actors of the global arena such as international institutions, foreign governments, private actors, and civil society organizations.

The international activism of cities in recent decades has been addressed by various authors across various disciplines (Acuto, 2013; Foster and Iaione, 2022; Gutiérrez-Camps, 2013; Kavaratzis, 2004). Cities promote themselves abroad (city marketing and branding) to attract people and capital, but they also develop internationalization strategies of city diplomacy, building relationships with political counterparts for various purposes.

City diplomacy can take the shape of unilateral bilateral and multilateral actions. Cities can operate alone to foster their international image, attracting flows of people and capital, and promoting their international projection. Moreover, city authorities can strengthen their ties with specific foreign cities, giving birth to bilateral initiatives or signing twinning programs that are a classical tool of city diplomacy. Finally, cities can build or join international urban networks, where a plurality of urban actors cooperate on different issues and join efforts to have a major impact on the international policy processes. With their participation in transnational networks, cities are both socialized regarding global issues and at the same time, they can tackle them more efficiently (Acuto and Leffel, 2021).

To better understand city responses to the pandemic from a city diplomacy perspective, the research builds a taxonomy based on the internationalization strategies and cities responses to the pandemic. The taxonomy considers three types of responses: unilateral action, bilateral collaboration, and multilateral/network cooperation. The different categories describe different levels of engagement that cities can have with international partners. The first level encompasses those actions that have limited international implications (unilateral action). At this level, cities do not actively engage with international partners. However, it is still possible to identify patterns of norms diffusion and mimicking of international practices. Cities can opt for self-reliance or national tools to address the challenges they face; individual actions during the pandemic have shown how a synergy between local, regional, and national levels of governance is needed to develop a consistent response to crises (Lawrence, 2020); cities can then engage in the first stage of internationalization by strengthening ties with a specific partner (bilateral). Bilateral actions follow the classical pattern developed by the twinning programs, one of the most common strategies of cities internationalization; bilateral actions have proven successful in developing immediate responses to the pandemic, as well as sharing best practices and obtaining resources such as medical equipment that was lacking during specific phases of the pandemic. Finally, cities can engage in complex and interconnected relations, multiplying their partners and relying on formal or informal networks (multilateral/network). International city networks have been channels for the sharing of practical (responses and vaccination plans) and non-material (know-how) resources. Cities have used preexisting networks, and they have created new relations. Moreover, top-down initiatives have also taken place. International organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) have activated regional city networks such as WHO European Healthy Cities Network to coordinate actions across the region and to support city-level implementation of WHO guidance (WHO, 2021). In analyzing the actions that cities have undertaken during the pandemic, the analysis will try to highlight the pros and cons of each type of action to show how cities have dealt with their challenges as well as to show that city diplomacy has been a major tool in the hands of cities. Moreover, the analysis will focus on the conditions that have allowed city networks to implement various levels of responses.

Cities engage in diplomatic strategies even without engaging in partnerships with foreign counterparts. Cities can develop international strategies to increase their prestige, attracting tourism, workers, investments, and other resources. This is the case of international strategies that seek to promote a city image abroad. From basic branding strategies (Kavaratzis, 2004) to hosting international events such as Olympics or Expos, cities dedicate part of their resources to unilaterally engage with the world.

While these are common strategies to be implemented by cities during normal times, unilateral actions become more complex when it comes to crisis such as the pandemic, where much of the unilateral actions that city had to implement related more with the domestic dimension than the global one.

Before operating internationally, cities operate first and foremost at the local level in coordination with regional and national governments. The response to the COVID-19 pandemic followed a similar pattern with local administrators calling to implement national provisions and manage their various practical implications locally. Beyond the immediate response, which required direct communication with the central governments, cities have then started developing local solutions and plans to set the base for the management and the recovery from COVID-19. Local initiatives can be traced all over Europe and across various sectors that usually fall within the competencies of local authorities. These sectors include transportation and mobility, management of public space, housing and local economy protection, and reduction of education inequalities (Tosics, 2020). The fact that cities have engaged heavily with the domestic domain during the pandemic, does not mean that they have been completely excluded by the influence of the international dimension.

Effects of city diplomacy might not be formally constructed into explicit relations. However, cities can still look at international counterparts to understand which policies might be implemented and what their effects might be. Following usual patterns of policy diffusion (Simmons et al., 2007), urban policies can be adopted across different contexts through ideology, coercion, competition, and learning. While cities might be approached by all these different views. However, when it comes to COVID-19’s response, especially in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, mechanisms of coercion and competition are less suited to explain shared practices across contexts. Coercion sees the presence of a small number of players that can exercise influence over others (Owen, 2002). While there might be “more powerful” cities on the global stage shaping practices through direct and indirect influence (Gleditsch and Ward, 2008), the framework set by the pandemic does not seem to be suitable for this dynamic equalizing the stress test on different urban environments. As a different mechanism, competition sees the diffusion of policies as a result of a policy giving an advantage to an actor. Other actors will also implement similar policies even if they were not initially planning it because of competition for the acquired advantage. It would be a mistake to understand inter-cities dynamics without considering a competitive dimension. It would also be a mistake to believe that there is not a competitive component of cities’ relations when it comes to COVID-19. However, a competition approach is indeed more suited to explain certain conditions of the strategies implemented in the aftermath of the pandemic, such as competition for recovery funds, projects, and technologies, than the early responses when there were not many resources to compete for.

Mechanisms of ideology could help in explaining peaceful policy diffusion because of processes of social acceptance through (1) leading actors serving as examples, (2) epistemically communities supporting and therefore strengthening specific policies, (3) experts providing insights on the effects providing implementation support. However, such dynamics usually need relative time to take place (Edelman, 1992; Finnemore and Sikkink, 2001; Haveman, 1993). Similarly, to competitive mechanisms, processes of diffusion based on ideology might be inappropriate to study the early phases of cities’ responses to the pandemic, while could be more suited to understanding longer processes of mimicking and adaptation.

Instead, rational learning mechanisms are based on the idea that behind the diffusion of policies there is a cost-benefit analysis. Under these conditions, policymakers learn from the experiences of other contexts. While this might lead to mimicking also of suboptimal policies, policymakers usually engage in Bayesian updating, continuously adding information to the knowledge base (Huth and Russett, 1984; Powell, 1988; Vivalt and Coville, 2023). This learning mechanism is indeed more suited to frame the various similar initiatives that have spread across cities in the early phases of the pandemic response, cities ways of rethinking spaces have spread across Europe, with initiatives developing bike lanes, pedestrian areas, and rerouting public transport. While assessing a direct relation between initiatives following an explicit mimicking process is not the purpose of this paper, the framework offered by rational learning allows for a better comprehension of the array of similar city initiatives that have sprouted across Europe and the globe.

Individual actions show how cities are central in managing the practical issues related to the response to the pandemic, as the forefront of the fight against the virus, the autonomy given to cities in implementing policies, receiving and managing funding as well as developing tailored initiatives is crucial, especially in situations where immediate actions, massive mobilization, and systemic solutions are crucial to address the challenges posed by the crisis (Pisano et al., 2020). Although individual actions have stressed this role of cities, the distribution of authority in multileveled governance frameworks is subject to discussion. While some case studies show that preexisting schemes of policy-making arrangements do not seem to have been affected (Hirschhorn, 2021), others show how that innovation in governance can take the form of bottom-up processes with the experimentalism of innovative forms of governance can originate from cities themselves (McGuirk et al., 2021). Whether or not the pandemic will prompt innovation in the governance structure between local and national governments is something that can be assessed in the next years, as States slowly get out of the acute phases of the pandemic and start rethinking their structural arrangements. However, the early phases of the pandemic have indeed shown how even individually, cities have been active in acting against the virus.

A review of the various initiatives that cities have adopted to face the pandemic is offered by Eurocities that has mapped during the various phases of the crisis the different projects implemented at the urban level.1 Cities like Rome and Bordeaux have implemented emergency cycling plans usually following a temporary to permanent scheme. Madrid and Dublin have released a recovery mobility plan to manage the return to the use of public transport. Cities such as Nantes and Riga have offered housing support providing financial aid to those in need. Vienna has planned to build 1,000 municipal apartments in the next years. The city of Utrecht has increased national support to freelancers and small and medium enterprises with local initiatives such as the suspended collection of taxes and compensations. Similarly, Sofia has established a temporary economic council to elaborate measures to support local businesses that have worked on similar solutions. Unilateral actions have moved within the spaces and limits of urban governance, with cities attempting to manage local problems through local based solutions. Bilateral and multilateral actions have instead seen a higher level of engagement with transnationalism and international cooperation.

City to City (C2C) cooperation is at the base of city diplomacy (ISIG, 2015). Cities interact with foreign counterparts under institutionalized partnerships (twinning programs) or on specific issues and situations. Together with individual actions to face the pandemic, cities have also undergone a series of bilateral initiatives. These initiatives have mostly been focused on sharing experiences and know-how and procuring sanitary equipment when lacking through the national chains of acquisition. European cities have been active in developing such initiatives at the European level and internationally. For instance, Madrid and Buenos Aires have exchanged experiences concerning the food service sector, markets, gyms, and other public spaces in a bilateral meeting (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 2020).

European cities have also established numerous bilateral initiatives with their Chinese counterparts. Through its “mask diplomacy” (Verma, 2020; Wong, 2020) or foreign policy by proxies, China has actively promoted support to European cities in the form of medical equipment. This has often happened within the framework provided by preexisting twinning programs between European and Chinese cities. Belfast and its Chinese sister city Shenyang have exchanged masks and other protective equipment, at the beginning of the pandemic it was the European city that send the material to the Chinese counterpart returning the favor as the pandemic expanded in Europe (Kenwood, 2020). Similarly, working on the relations with its Chinese twinned cities (Macau and Shenzhen), the city of Porto has received a supply of ventilators necessary during the early weeks of the pandemic (Porto, 2020).

During the acute early phases of the pandemic, cities have also exchanged patients, trying to alleviate the pressure on local hospitals. In March 2020 Germany started accepting COVID-19 patients from border countries, and patients from hospitals in the Region Grand Est of France were transferred to Mannheim, Heidelberg, Freiburg, and Ulm (Zeitung, 2020). While patients from Lombardy in Italy were accepted in German Hospitals in six different German Lander (Bufacchi, 2020). While these initiatives are not promoted directly by cities, but rather by regional authorities (sometimes on the initiative of members of parliament), transfers have often seen cities again as the first respondents in their management. This again stresses the importance of putting cities in a multileveled governance framework that from the urban level reaches the international one passing through the regional, national, and European ones. This becomes even more relevant when looking at two different phenomena. While individual city actions have shown how cities are suited to manage the practical actions needed to deal with the limits imposed by the virus, international bilateral actions show that cities can intervene when other national authorities’ manifest incapacity to act or to provide for the needs of urban realities. These are the types of actions that fall within the assistance/cooperation category proposed before. Cities are shown to be active players in the international arena, filling gaps left by the state, and bypassing them when needed. Beyond bilateral action, cities can also use city diplomacy to coordinate in a multilateral framework, strengthening their response capacity, sharing experiences, and promoting aggregate instances to supranational and international organizations (Pipa and Bouchet, 2020).

The third level of actions that cities can undertake to engage with global dynamics is represented by networked actions. As far as the response to the pandemic is concerned, the city network represents an interesting case study as a series of different strategies and dynamics have been undertaken. Cities have relied on networks (1) to share experiences, (2) to track and share individual initiatives with their members, (3) to produce resources to provide cities with tools useful to better manage the crisis, (4) to fill the gap between the local and the global dimension, enhancing the work of IOs, and merging the various interests of cities providing aggregated strategies for international advocacy.

City networks originate following two distinct dynamics, a top-down and a bottom-up process. Top-down networks see the active promotion of a city’s initiatives by international or supranational actors such as International Organizations or the European Union. In promoting city networks, IOS recognizes the intrinsic value of cities as the ultimate level of implementation (Gutiérrez-Camps, 2013). Promoting urban collaboration allows IOs to close the gap between the international and the local levels more efficiently. Bottom-up processes see cities engage with partners without external inputs, they come together as there is the recognition that collective action can lead to more efficient results in providing specific public goods. In comparing city networks’ responses to the pandemic, this distinction appears clear. Nevertheless, even bottom-up networks can generate instances of hybrid partnerships that see the networks collaborate with international agencies on specific issues (Cogan, 2021).

When looking at networked actions of cities during the pandemic, it is important to highlight that health-related issues were rarely directly addressed within urban networks, that usually focused on a variety of topics. Sanitary strategies and practices were indeed part of city networks’ actions before the pandemic. However, health was often contained as a sub-subject of major issue areas such as environment, disaster management, social inclusion, and sustainable development. Therefore, many major networks had to readapt their focus and activities to provide their members with the needed support during the pandemic. Such a readaptation is a common practice in non-governmental networks of for instance NGOs. At the same time, there is not a good theorization of if and how this might happen at the city level when it comes to city networks. If other practices of internationalization have been more easily identified and follow known patterns of action, the following analysis focuses on understanding how cities and city networks have reacted and how they have engaged with other international actors participate in this process.

To substantiate the taxonomy the analysis reviews different city initiatives to the pandemic according to the dimensions identified. This allowed us to show how cities have a large portfolio of options when they decide to engage internationally through different city diplomacy structures.

Mapping unilateral and bilateral actions of cities during the pandemic is not easy. However, the network Eurocities has created an online platform to gather and share information about the various initiatives implemented by its members providing a useful example and database of different implemented initiatives. A review of these data provides good evidence of the fact that cities have strengthened and used their unilateral capacities and bilateral during the pandemic. Data from Eurocities offer a unique understanding of what cities have done nationally and internationally during COVID-19 times. To help its members in sharing experiences and know how, Eurocities has developed the CovidNews platform where initiatives undertaken by cities in the face of the pandemic are gathered and organized to keep track of urban action across the members. As a matter of fact, the CovidNews platform represent a good example of the sharing initiatives that some networks have implemented during the crisis.

The platform incudes city profiles with relevant information on COVID-19 management and policies as well as a section on EU instruments including funding and support opportunities together with EU institution’s activities in the field of economy and underemployment as well as a review of the initiatives and publication of other international organizations with relations to urban actions like the WHO, the OECD, and the FAO.

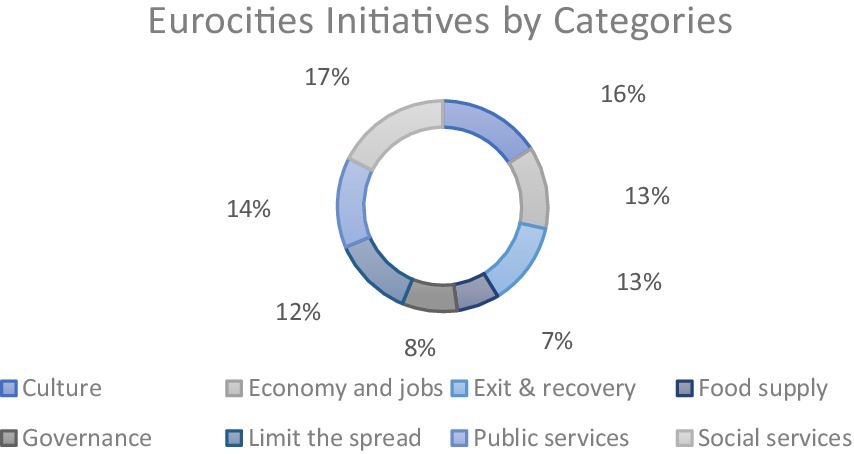

These initiatives have also been categorized by the network according to the various sectors they relate to. Eurocities has adopted eight categories.2 Every single initiative can have more than one category. Considering the aggregated categorization used by Eurocities, it can be noticed that initiatives in the field of social services (17%) and culture (16%) have been the ones more implemented, followed by those in public services (14%), economy and jobs (13%) and exit and recovery (13%) which are just a little bit more frequent than initiatives linked to exit & recovery (12%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Authors elaboration on data derived from CovidNews. The data obtained from the platform can also be used to have a picture of the initiatives scattered across the various member states. From the data it is possible to see that while some states have seen a more active participation of their cities, others did not have such an intense response.

According to these data, western Europe has seen its cities more active than eastern Europe (besides Turkey). Spain has the major number of reported cities initiatives (105). The data should not be taken as an absolute evaluation of city responsiveness to the pandemic. Yet, data offer a relative measure of city international visibility, participation and engagement. Spain’s result for instance sees the great number of reports on Madrid (52/105), Germany by the city of Dusseldorf (35/85) the UK by the city of Cardiff (32/86) and France by the city of Nantes (35/92) (see Figure 2). Besides considerations on initiative distribution across the network which could be interesting for further research on the topic, the review of the data and information provided by CovidNews clearly shows how cities have navigated existing ties during the crisis brought by the pandemic. The remaining question becomes whether this activism built on unilateral and bilateral actions can be applied to city networks as well.

The role of TCNs is well established in the literature, especially when focusing on issues such as climate action (Heikkinen, 2022) and migration (Lacroix and Spencer, 2022; Oomen et al., 2018). Similar to how civil society organizations use transnational civil society networks (TCSNs) (Valeriani, 2021), TCNs are used by cities to strengthen their institutional capacity, access resources, and gain international visibility (Heikkinen, 2022). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic health crisis, work has shown how TCNs have been used to amplify the voices of cities at the international level, as the case of C40 illustrates (Pipa and Bouchet, 2020). However, less attention has been paid to the capacity of these networks to produce resources specific to the crisis. By analyzing the data, three types of responses by TCNs have been identified: self-production, sharing or both. Indeed, most of the data shows that TCNs that acted during the pandemic used online platforms or webinars to share best practices and facilitate interaction among their members. Rarely did networks produce their own materials, toolkits and support initiatives for their members. Table 1 summarizes this information below.

The three different responses of TCNs mentioned above may be the result of different factors. Drawing on the existing literature, the research expects TCNs responses to be influenced by their ability to redirect their focus and change the problem (Al Jayousi and Nishide, 2024; Brown and Kalegaonkar, 1999). Consistent with resource dependency theory (Biermann and Harsch, 2017; Drees and Heugens, 2013; McCarthy and Zald, 1977; Zhan and Tang, 2013), the paper expects to see higher levels of engagement (self-production or both) in networks that have large resources, global outreach or partnerships with IOs that can provide both resources and expertise. Finally, the research expects networks that have previously focused on health-related issues to be better positioned to develop more complex solutions.

These expectations are linked to a specific scope condition in the context of TCNs: dimension (number of members), outreach (geographical collocation of members), initial scope (whether health was among their missions before the pandemic), and relationship with IOs (whether they had partnerships with international organizations). The dimension and the geographical outreach of TCNs were taken into account in line with the assumption that larger networks have more resources and capacity to adapt to systemic changes. Therefore, cases with a large dimension were coded fully in (1), while those cases categorized as medium or small were coded as fully out (0). Similarly, cases with a global outreach were coded fully in; while those with a regional outreach were coded fully out. With regard to the condition focused on health, networks that were already active in the health field and therefore had an advantage in providing solutions to the pandemic were coded fully in (0), while those that were not active in the health sector were coded fully out. Finally, partnerships with IOs were considered as a dimension to measure whether TCNs played the role of bridging the gap between the national and the international. On this basis, TCNs with an IO relationship were coded fully in (0) and those without were coded fully out (0).

To identify patterns of conditions shared by different TCN responses, the paper conducts a small crisp set QCA analysis. In brief, QCA is a research method designed to identify different patterns of conditions in terms of necessity and sufficiency. Unlike traditional statistical approaches, QCA focuses on configuration, recognizing that multiple combinations of conditions can lead to the same outcome, a concept known as equifinality. It is particularly suited to small to medium-sized datasets, where the interaction of conditions can be systematically explored. This makes QCA a powerful tool for understanding complex, real-world phenomena, such as the response of cities during a pandemic. The analytical part of the study is based on the creation of a truth table, consisting of a set of calibrated raw data, into membership scores that outline all possible combinations of conditions and their corresponding outcomes (Annex 1 and Table 2). In this case, the identification of these combinations is facilitated by the Quine–McCluskey algorithm, which generates parsimonious solutions. The key parameters in QCA include consistency, which measures the extent to which the identified combinations align with the observed outcomes, and coverage, which quantifies the proportion of the outcome explained by these combinations (Duşa, 2019; Oana et al., 2021; Ragin, 2014).

The empirical benchmark against which the paper assesses these conditions consists of 42 different TCNs. The resulting dataset has been constructed using primary data from the websites of the TCNs, as well as official reports and documents or newspaper articles. This initial dataset was then reduced to 15 networks, as it originally included national city networks or city networks so small and specific that it was impossible to retrieve relevant information about their COVID-19 activities.

The results revealed multiple pathways for each of the TCNs’ responses. Starting with the first response, where networks provided platforms for knowledge sharing among member cities during the pandemic, the analysis identified two configurations that sufficiently explain this outcome. The first pathway combines the presence of IO partnerships with the absence of health initiatives (IOPartnership∗∼Health). The second path instead combines global outreach and partnerships with IOs (Outreach∗IOPartnership). These results suggest that in the presence of large platforms of global outreach, the intervention of an external international organization can favor the implementation of knowledge sharing initiatives in networks, even if these networks were previously focused on a different thematic area than health. The main TCNs involved in these relationships include UCLG, City Alliance and Cities4Health.

Self-produced responses refer to TCNs that produced unique solutions during a pandemic. These solutions differed from simple knowledge sharing and included specific initiatives such as toolkits, webinars and training. Three pathways were identified. First, cities that already had a health focus were more engaged in self-production. Contrary to what was previously observed, this highlights the central role of health-specific policies in promoting self-production. It also suggests an attempt on the part of the networks to use the adaptation of their online platforms into knowledge-sharing systems for the benefit of members as the most immediate solution, leaving more complex solutions to those networks that already presented certain skills in the specific sector. The second path combined the absence of global outreach with the presence of an IO partnership (∼Outreach∗IOPartnership), suggesting an interesting combination of IO engagement with regional rather than global networks. While the third path to self-production combined large resources and partnerships with IOs, it shows that there are also cities that align their goals with IOs and are successful in self-production. The WHO European Healthy Cities Network, Eurocities and UCLG are some of the networks covered by these combinations.

The last response includes cities that simultaneously engage in sharing and self-production, representing a dual strategy. Three configurations were identified. The first pathway included a large dimension combined with IO partnerships (Dimension∗IOPartnership), suggesting that resources and partnerships are crucial for balancing sharing and self-production. The second pathway involved global outreach combined with health (Outreach∗Health), lending support to the idea that outreach and health related preexisting strategies are key in achieving dual outcomes. Surprisingly, the third pathway included that the absence of both outreach and health combined with the presence of IOP partnership (∼Outreach∗IOPartnership∗∼Health) can also lead to such an outcome for the same cases. This suggests that besides other factors partnerships with IOs can allow TCNs to produce effective responses.

In general, these results show that very few major TCNs dealt with health issues before the pandemic. Indeed, the pandemic prompted a rapid response from those networks that had not dealt with the issue before. However, those networks that had been working on health issues before the pandemic showed great capacity to develop substantive initiatives during the pandemic, including the promotion of self-developed guidelines. However, it is important to note that health TCNs have strong links with WHO, which used TCNs during the pandemic to develop, publish and promote guidelines and toolkits for local authorities. The relationship with the IOs seems to be the real prerequisite for TCNs to develop their own initiatives during the pandemic. While several networks promoted joint initiatives, many of which were not health-related before COVID-19, only those that had direct relations with international organizations developed more substantial initiatives. This result seems to suggest two conclusions: first, TCNs, even those not involved in health before the pandemic, managed to adapt their platforms to provide basic assistance to their members in the form of best practice sharing moments and platforms. Second, structured relationships between TCNs and IOs have led to more substantial solutions.

This study has shown that the pandemic has not limited international action on the part of cities, which have engaged globally at different levels to respond to the challenges posed by the crisis. The paper has identified three main categories that summarize different levels of engagement with the international arena: unilateral, bilateral and multilateral actions. The first two refer to two different ways of engaging with the international system: the first is a self-driven scouting of the international system for self-promotion, resources or know-how. The second is the identification of a partner with whom there is a structured relationship, which can be informal or formal if there is a written agreement. Both strategies were used by cities during the pandemic. The third level of engagement in city diplomacy is participation in TCNs. TCNs have tried to adapt to serve their members during the crisis. Although very few TCNs dealt with health-related issues before the pandemic, many of them were able to adapt their platforms to provide support and communication spaces for their members who actively engaged with them. By engaging with IOs and attempting to re-adapt their structures, TCNs appear to follow classic patterns of non-state actor-driven networks in the international system. Moreover, the TCNs that have developed home-grown solutions, such as guidelines and toolkits, are those that have relationships with IOs, suggesting that even in times of crisis, TCNs are an important intermediary between the international and the local. TCNs also appear to be limited in their capacity to fully readapt, especially if they have a focus on a different issue area and if they have access to limited resources. In addition, the findings contribute to the idea that TCNs play an important role in bridging the gap between the global and the local, which is a crucial tool for IOs interested in implementing their agendas and projects at the local level. In light of this, IOs should consider partnering with TCNs to maximize their results by providing resources and know-how to TCNs to increase their effectiveness and capacity. Indeed, TCNs represent the essential fabric of the internationalization of cities. While facing the challenges posed by the global system, participation in TCNs can help cities obtain material and immaterial resources and identify relevant partners to address challenges and crises. With these findings, this study, therefore, sought to contribute to the literature on city diplomacy and crisis management by demonstrating different action patterns and paving the way for further studies examining the interactions between cities, TCNs, and other actors.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

MV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1556963/full#supplementary-material

1. ^A good dataset of local initiatives in responding to the pandemic is offered by Eurocities https://covidnews.eurocities.eu/.

2. ^Culture; economy and jobs; exit & recovery; food supply; governance; limit the spread; public services; social services.

Acuto, M., Larcom, S., Keil, R., Ghojeh, M., Lindsay, T., Camponeschi, C., et al. (2020). Seeing COVID-19 through an urban lens. Nat. Sustain. 3, 977–978. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-00620-3

Acuto, M., and Leffel, B. (2021). Understanding the global ecosystem of city networks. Urban Stud. 58, 1758–1774. doi: 10.1177/0042098020929261

Al Jayousi, R., and Nishide, Y. (2024). Beyond the ‘NGOization’ of Civil Society: A Framework for Sustainable Community Led Development in Conflict Settings. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 35, 61–72. doi: 10.1007/s11266-023-00568-w

Avant, D. D., Martha, F., and Susan, K. S. (2010). 114 Who Governs the Globe? Cambridge University Press.

Ayuntamiento de Madrid. (2020). Madrid and Buenos Aires exchange experiences about the foodservice sector after the COVID-19 pandemic. Available online at: https://www.madrid.es/portales/munimadrid/es/Inicio/El-Ayuntamiento/Madrid-and-Buenos-Aires-exchange-experiences-about-the-foodservice-sector-after-the-COVID-19-pandemic/?vgnextfmt=default&vgnextoid=201aa62d677c2710VgnVCM1000001d4a900aRCRD&vgnextchannel=ce069e242ab26010VgnVCM100000dc0ca8c0RCRD. (Accessed March 22, 2023)

Barber, B. R. (2013). If mayors ruled the world: dysfunctional nations, rising cities. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Baum, S., Baker, E., Davies, A., Stone, J., and Taylor, E. (2022). Pandemic cities: the COVID-19 crisis and Australian urban regions. 1st Edn. Singapore: Springer.

Biermann, R., and Harsch, M. (2017). “Resource dependence theory” in Palgrave handbook of inter-organizational relations in world politics. eds. J. A. Koops and R. Biermann (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 135–155.

Brown, L. D., and Kalegaonkar, A. (1999). Addressing Civil Society’s Challenges: Support Organizations as Emerging Institutions. Citeseer. Available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=38cb1abc0ab992c7d20ad8ccc85ccb4d0502c416 (Accessed November 15, 2024).

Bufacchi, I. (2020). Coronavirus, Il Gesto Del Governo Tedesco: 47 Italiani Curati in Terapia Intensiva in Germania—Il Sole 24 ORE. Il Sole 24 Ore. Available online at: https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/coronavirus-47-italiani-curati-terapia-intensiva-germania-ADUmWAG

Drees, J. M., and Heugens, P. M. A. R. (2013). “Synthesizing and Extending Resource Dependence Theory ”. Journal of Management.

Cogan, J. K. (2021). “International organizations and cities” in Research handbook on international law and cities (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 158–172.

Edelman, L. B. (1992). Legal ambiguity and symbolic structures: organizational mediation of civil rights law. Am. J. Sociol. 97, 1531–1576. doi: 10.1086/229939

Finnemore, M., and Sikkink, K. (2001). Taking stock: the constructivist research program in international relations and comparative politics. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 4, 391–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.391

Foster, S. R., and Iaione, C. (2022). Co-cities: innovative transitions toward just and self-sustaining communities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gleditsch, K. S., and Ward, M. D. (2008). “Diffusion and the spread of democratic institutions” in The global diffusion of markets and democracy. eds. B. A. Simmons, F. Dobbin, and G. Garrett (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 261–302.

Gutiérrez-Camps, A. (2013). Local efforts and global impacts: a city-diplomacy initiative on decentralisation. Perspectives 21, 49–61.

Haass, R. N. (2008). The Age of Nonpolarity: What Will Follow US Dominance. Foreign affairs : 44–56.

Haveman, H. A. (1993). Follow the leader: mimetic isomorphism and entry into new markets. Adm. Sci. Q. 38, 593–627. doi: 10.2307/2393338

Heikkinen, M. (2022). The Role of Network Participation in Climate Change Mitigation: A City-Level Analysis. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 14, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/19463138.2022.2036163

Hirschhorn, F. (2021). A multi-level governance response to the COVID-19 crisis in public transport. Transp. Policy 112, 13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.08.007

Huntington, S. P. (1993). The Clash of Civilizations?. Foreign Affairs 72, 22–49. doi: 10.2307/20045621

Huth, P., and Russett, B. (1984). What makes deterrence work? Cases from 1900 to 1980. World Polit. 36, 496–526. doi: 10.2307/2010184

ISIG (2015). City-to-city cooperation toolkit. Gorizia: Institute of International Sociology & Council of Europe.

Kaldor, M., and Sassen, S. (2020). Cities at war: global insecurity and urban resistance: Columbia University Press: New York

Kavaratzis, M. (2004). From city marketing to city branding: towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 1, 58–73. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990005

Kenwood, M. (2020). Belfast gets PPE shipment from Chinese sister city Shenyang in response to donation of coronavirus kit. Available online at: https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/health/coronavirus/belfast-gets-ppe-shipment-from-chinese-sister-city-shenyang-in-response-to-donation-of-coronavirus-kit/39150132.html. (Accessed March 22, 2023)

Lacroix, T., and Spencer, S. (2022). City networks and the multi‐level governance of migration.Global Networks, 22, 349–362. doi: 10.1111/glob.12381

Lawrence, R. J. (2020). Responding to COVID-19: What’s the problem? J. Urban Health 97, 583–587. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00456-4

Malik, A., Lenzen, M., Li, M., Mora, C., Carter, S., Giljum, S., et al. (2024). Polarizing and equalizing trends in international trade and sustainable development goals. Nat. Sustain. 7, 1359–1370. doi: 10.1038/s41893-024-01397-5

Marchetti, R. (2021). City diplomacy: from city-states to global cities. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Marchetti, R., and Menegazzi, S. (2022). Manuale di politica internazionale. Teorie per capire la politica globale. Roma: Luiss University Press.

McCarthy, J. D., and Zaid, M. N. Z. (1977). “Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 82, 1212–41. doi: 10.1086/226464

McGuirk, P., Dowling, R., Maalsen, S., and Baker, T. (2021). Urban governance innovation and COVID-19. Geogr. Res. 59, 188–195. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12456

Meagher, K., El Achi, N., Bowsher, G., Ekzayez, A., and Patel, P. (2021). Exploring the role of city networks in supporting urban resilience to COVID-19 in conflict-affected settings. Open Health 2, 1–20. doi: 10.1515/openhe-2021-0001

Oana, I.-E., Schneider, C. Q., and Thomann, E. (2021). Qualitative comparative analysis using R: a beginner’s guide. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Oomen, B., Baumgärtel, M. G., and Durmuş, E. (2018). Transnational city networks and migration policy. Available at: https://repository.uantwerpen.be/link/irua/192919

Owen, J. M. (2002). The foreign imposition of domestic institutions. Int. Organ. 56, 375–409. doi: 10.1162/002081802320005513

Payne, A. (2008). The G8 in a changing global economic order. Int. Aff. 84, 519–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2008.00721.x

Pipa, A. F., and Bouchet, M. (2020). Multilateralism restored? City diplomacy in the COVID-19 era. Hague J. Diplomacy 15, 599–610.

Pisano, G. P., Sadun, R., and Zanini, M. (2020). Lessons from Italy’s response to coronavirus. Harvard Business Review. Available online at: https://hbr.org/2020/03/lessons-from-italys-response-to-coronavirus

Porto. (2020). Rui Moreira já estabeleceu ligação entre Shenzhen e Hospital de São João para trazer ventiladores da China. Available online at: https://www.porto.pt/pt/noticia/rui-moreira-ja-estabeleceu-ligacao-entre-shenzhen-e-hospital-de-sao-joao-para-trazer-ventiladores-da-china/. (Accessed March 22, 2023)

Powell, R. (1988). Nuclear brinkmanship with two-sided incomplete information. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 82, 155–178. doi: 10.2307/1958063

Ragin, C. C. (2014). The comparative method: moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Simmons, B. A., Dobbin, F., and Garrett, G. (2007). The global diffusion of public policies: social construction, coercion, competition or learning? Annu. Rev. Sociol. 33, 449–472. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.090106.142507

Tosics, I. (2020). Cities against the pandemic. Brussels: Foundation for European Progressive Studies.

Valeriani, M. (2021). “Global complexity, civil society, and networks” in Global networks and European actors: navigating and managing complexity, globalisation, Europe, multilateralism. eds. G. Christou and J. Hasselbalch (London: Routledge), 163–180.

Verma, R. (2020). China’s diplomacy and changing the COVID-19 narrative. Int. J. 75, 248–258. doi: 10.1177/0020702020930054

Vivalt, E., and Coville, A. (2023). How do policymakers update their beliefs? J. Dev. Econ. 165:103121:103121. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2023.103121

WHO (2021). Healthy cities for building back better: political statement of the WHO European healthy cities network. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Wong, B. (2020). China’s mask diplomacy. The Diplomat. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2020/03/chinas-mask-diplomacy/

Zeitung, B. (2020). Baden-Württemberg nimmt schwerstkranke Corona-Patienten aus dem Elsass auf. Badische Zeitung. Available online at: https://www.badische-zeitung.de/baden-wuerttemberg-nimmt-schwerstkranke-corona-patienten-aus-dem-elsass-auf--184226003.html. (Accessed March 22, 2023).

Keywords: city diplomacy, COVID-19, global governance, non state actors, city networks, crisis response and management, QCA

Citation: Valeriani M, Marchetti R and Passalacqua CC (2025) Cities, states and the pandemic: challenges and opportunities for transnational city networks. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1556963. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1556963

Received: 07 January 2025; Accepted: 05 March 2025;

Published: 02 April 2025.

Edited by:

Marco Improta, University of Siena, ItalyReviewed by:

Sulaimon Adigun Muse, Lagos State University of Education (LASUED), NigeriaCopyright © 2025 Valeriani, Marchetti and Passalacqua. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: M. Valeriani, bXZhbGVyaWFuaUBsdWlzcy5pdA==; R. Marchetti, cm1hcmNoZXR0aUBsdWlzcy5pdA==; C. C. Passalacqua, Y2xhdWRpby5wYXNzYWxhY3F1YTJAdW5pYm8uaXQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.