94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 08 April 2025

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 7 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2025.1553889

This article is part of the Research TopicA Reflection on Conceptions and Theories of Emotion across Three Disciplines: Psychology, Political Psychology and Political ScienceView all articles

Affective polarization, characterized by animosity and distrust between partisan groups, threatens democratic resilience and social cohesion by fostering social distance, moral superiority, and political intolerance. This study conceptualizes affective polarization as a form of othering that undermines Aristotle’s concept of philia—political friendship—essential for mutual respect and dialogue. Using survey data from 4,006 respondents in Türkiye, we measure dimensions of polarization, including aversion to social interactions with out-groups, stereotyping, and the denial of basic rights to perceived opponents. Results reveal entrenched divisions, with in-groups attributing positive traits to themselves while assigning negative characteristics to out-groups, reinforcing a “them versus us” mentality. To complement these findings, a field experiment examines participants’ emotional responses to politically charged scenarios involving global warming, bilingualism, and headscarves. Strong negative emotions, including anger and disgust, are directed toward out-groups, highlighting the visceral intensity of polarization and its role in deepening societal divides. By framing affective polarization within the theoretical lens of philia and othering, this study underscores its implications for democratic governance, emphasizing the need for strategies to rebuild trust, reduce hostility, and foster inclusive dialogue rooted in civic values.

Aristotle’s concept of philia—political friendship—serves as the ethical foundation of social cohesion and democratic engagement. Encompassing mutual goodwill and respect, philia nurtures the relational ties that bind citizens together in pursuit of the common good. However, the contemporary rise of horizontal affective polarization disrupts this ideal, replacing mutual understanding with distrust, tribalism, and moral hierarchies. Affective polarization, as Iyengar (2019) argue, transforms political opponents into moral and social “others,” fostering animosity and eroding the civic virtues essential for dialogue and inclusivity. This paper examines affective polarization as a form of othering, exploring how it undermines philia and jeopardizes democratic resilience by reframing civic relationships in terms of moral superiority, exclusion, and antagonism.

The role of emotions in shaping political behavior has been a longstanding subject of inquiry in both political science and psychology. Traditional theories have often relied on valence-based models, categorizing emotions as simply positive or negative, or treating them as secondary to rational decision-making. However, Marcus (2023) critiques these approaches, arguing that existing emotion theories fail to account for the complexity of emotional processes, particularly their preconscious and regulatory functions in political engagement. This study builds on Marcus’s insights by examining how emotions—specifically anger, disgust, and anxiety—fuel affective polarization and political intolerance in Türkiye. By moving beyond valence-based frameworks, we demonstrate that emotions are not just passive reflections of political attitudes but active drivers of division and identity formation. Furthermore, this study introduces Aristotle’s concept of philia as a mechanism for regulating political emotions, aligning with Marcus’s call for a more integrated approach that considers how emotions can be managed for democratic cohesion. Through this theoretical synthesis and empirical validation, we contribute to a growing body of research that seeks to understand the profound role emotions play in democratic stability and breakdown.

Focusing on Türkiye’s deeply polarized political landscape, this study investigates the mechanisms through which affective polarization subverts civic unity. Drawing on Aristotle’s relational ethos and Marcus’ (2023) emotional regulation theory, we argue that affective polarization dismantles the foundations of philia, replacing shared goodwill with tribal loyalty and moral stratification. According to Marcus (2023) “understanding how emotion governs our responses to threats is critical of wellbeing of both democratic and autocratic regimes” (p. 14). The resulting dynamics of othering—manifested through social distance, moral superiority, and political intolerance—redefine civic life as a battleground of in-groups and out-groups. Social distance reflects the reluctance to engage in relationships, such as friendships or familial connections, with out-group members. Moral superiority emerges as in-groups attribute positive traits like patriotism and honor to themselves while assigning negative traits like selfishness and bigotry to out-groups. Political intolerance, perhaps the most alarming dimension, sees individuals rejecting fundamental rights for those perceived as morally deviant, thereby eroding the inclusive framework of democracy.

This study employs a robust mixed-method approach to illuminate these dynamics. Drawing on survey data from 4,006 respondents across Türkiye, we quantify the dimensions of affective polarization, revealing entrenched social distance, pervasive moral superiority, and widespread political intolerance. These findings expose the depth of societal divisions, where out-group members are viewed not as fellow citizens but as threats to moral and civic order. To complement the survey, a field experiment presents participants with politically charged scenarios on topics such as global warming, bilingualism, and headscarves. By analyzing participants’ emotional responses—ranging from anger and disgust to pride—we uncover the visceral intensity of polarization, particularly its ability to elicit extreme affective reactions toward out-groups.

In conceptualizing affective polarization as a type of othering, this paper bridges theoretical insights on philia with empirical evidence from Türkiye’s polarized society. It sheds light on how affective polarization deepens intergroup hostility and undermines the relational virtues essential for democratic cohesion. Ultimately, this research highlights the urgent need for strategies to counter polarization, rebuild social trust, and reinvigorate the civic ethos of philia as a pathway to resilience and inclusive governance.

In the last decade, there is a growing literature that analyzes how “politics became our identity” (Mason, 2018) and how affective polarization-hostility, animosity toward opposing political identity partisanship at the mass level is based on social identification (Iyengar et al., 2012; McCarty, 2019). However, affective polarization itself is more complex than is commonly acknowledged, and different possible manifestations of affective polarization should be considered for understanding its effect on democracy (Westphal, 2024). To rethink affective polarization as a type of othering may contribute to this endeavor.

Othering refers to a distant, unequal, hierarchical relationship in which the “other” group is considered inferior to the ingroup (Brons, 2015). Othering has created the inferiority of group identities which is thought to be counter to normality, constructing an unfamiliar threat, and involves a relationship of power, inclusion, and exclusion (Udah and Singh, 2019). The process of othering is not recognizing the individual for herself but perceiving only as a member of the other group. This perception of belonging to an out-group automatically reflects all the negative stereotypes and attitudes (Tajfel and Turner, 1979) and further distancing between her and self, which does not give a chance to find shared, common points. Similarly, Powell and Menendian (2016) describe othering as the expression of prejudice based on group-based differences, us/them mentality, and hostility toward the unfamiliar or unknown. Othering is always “not just about the other but is also about the self.” (Sonpar, 2015, p. 177).

Othering includes hierarchy- (moral) superiority of the self or the in-group, which leads to different degrees of humiliation, from dislike and disrespect to hate. One of the obstacles to equality among members emerges when the “others’” needs and, sometimes, fundamental rights are undermined by a lack of empathy toward the other, as dehumanization also draws the boundaries of our moral community (Opotow et al., 2005) and therefore, lack of concern, responsibility or duty toward those outside the moral community (Sonpar, 2015). As partisanship has started to be conceptualized as a social identity (Hogg et al., 1995; Tajfel and Turner, 1979), particularly in a polarized political context, negative feelings toward other party supporters can easily be observed in the form of othering, which challenges the basic premise of democracy-moral equality among citizens.

Although there is a discussion whether party supporters also have become more polarized along ideologies (Webster and Abramowitz, 2017) or not (Fiorina et al., 2005); consensus is growing on the idea that (the American) public has become “more strongly partisan, affectively polarized, and sorted” (Luttig, 2018). The real challenge is no longer the political elites or the distance between party positions but the increasing animosity, dislike, and distrust toward other party supporters-horizontal affective polarization-which threatens the co-existence (Iyengar et al., 2012; Mason, 2015, 2018). Druckman et al. (2021) argues that “partisan identity is the principal mechanism of affective polarization, and that policy preferences factor into affective polarization largely by signaling partisan identity” and their findings also show that policy disagreement in itself drives interpersonal affect (2022). Several studies showed that this social identification process leads to othering in many diverse contexts. The distance between citizens grows, and negative feelings between polarized party supporters present a type of othering that is more stated than racial one in the USA context (Iyengar and Westwood, 2015). The growing distance between ordinary citizens challenges social cohesion. West and Iyengar (2022) interestingly find that out-group bias persists even when attachment to partisan identity is diminished. In an important study, Reicher et al. (2008) offer a five-step social identity model of the development of collective hate: identification; exclusion; threat perception; self-enhancement of the ingroup as uniquely “good” and the endorsement of the eradication of the out-group, they argue that these steps are not always in strict linearity.

It is crucial to understand the affective polarization and its dimensions as it threatens the basic principles of democracy (Finkel et al., 2020; Torcal and Harteveld, 2024). Partisan subjects are less altruistic, less trusting, and less likely to contribute to a mutually beneficial public good when paired with members of the opposing party (Whitt et al., 2021). To accept others’ democratic claims (Tappin and McKay, 2019) and defend the exercise of their rights are challenged and can even end in dehumanization (Finkel et al., 2020; Harel et al., 2020; Martherus et al., 2021; Moore-Berg et al., 2020). Finkel et al. (2020) identify three core ingredients of political sectarianism-othering, aversion, and moralization (2020). Similarly, by elaborating on evidence of partisan dehumanization during the 2016 U.S. Presidential campaign, Cassese (2021) demonstrates that partisans dehumanize their opponents in both subtle and blatant ways. The findings show that partisans who blatantly dehumanize opposing party members prefer greater social distance from their political opponents, and this is associated with perceptions of the greater moral distance between the parties, which is indicative of moral disengagement.

As affective polarization is fueled by social media, examples of online othering are often observed. Media discourse on a Facebook page demonstrates how affective polarization and dehumanization manifest through participation in a homogeneous enclave or echo chamber (Harel et al., 2020). Emotional responses to political content on social media, such as anger and disgust, reinforce affective polarization, particularly in polarized digital environments (Druckman et al., 2021; Iyengar, 2019; Törnberg, 2022).

Building on previous research on othering in Türkiye (Uyan-Semerci et al., 2017), this paper defines affective polarization as a form of othering characterized by three key dimensions: social distance between political party supporters, perceptions of moral superiority within one’s own party, and political intolerance toward supporters of the most distant party. To scrutinize this combination of affective polarization as a type of othering may contribute to understanding how and why horizontal affective polarization threatens democracy, as it endangers deliberation and social cohesion.

Traditional models of deliberative democracy prioritize rationality and impartiality as key pathways to legitimate political discourse (Benhabib, 1992; Habermas, 1996). While this emphasis on universal reason aims to ensure fairness, it often neglects crucial emotional, narrative, and relational dimensions of human interaction. Young (2002) critiques this “hyperrationality” as a culturally biased framework that privileges formal argumentation over affective and experiential modes of communication. Connolly (1991) also critiques Habermas’ emphasis on rationality, arguing that politics is inherently driven by affective and contingent factors rather than purely rational deliberation. He posits that agonistic pluralism, which embraces conflict and the emotional intensity of political life, offers a more realistic foundation for democratic engagement. This perspective challenges the hyperrational emphasis on consensus, advocating instead for productive contestation and emotional resonance in deliberation.

Parallel to Marcus’s (2023) critique of existing emotion theories highlighting the need for frameworks integrating emotion regulation into democratic engagement we propose Aristotle’s concept of philia as a mechanism that counterbalances affective polarization. Unlike traditional rationalist approaches that emphasize deliberation alone, philia fosters mutual goodwill and social cohesion by integrating emotional bonds into political life. This aligns with Marcus’s call for theories that not merely categorize emotions but explore how they can be moderate for democratic resilience.

To address these shortcomings, a proper understanding of democracy must integrate the relational ethos of philia by embracing emotional, narrative, and symbolic communication. philia, often translated as friendship, is a central concept in Aristotle’s philosophy, signifying mutual goodwill, understanding, and the pursuit of shared good for its own sake. Aristotle defines philia as “wanting for someone what one thinks good, for their sake and not for one’s own, and being inclined, so far as one can, to do such things for them” (Aristotle, 1909). This notion of philia extends beyond personal relationships and into political life, forming the ethical foundation of democratic systems.

According to Aristotle, philia serves as a crucial element in building and sustaining social cohesion for just regimes, as it is not confined to private relationships but is essential to political communities, acting as the relational glue that holds societies together (Aristotle, 2011). In democratic contexts, this relational virtue fosters solidarity and mutual support among citizens, creating an environment conducive to cooperative governance (Aristotle, 1943). Democracy relies on this shared sense of goodwill, necessitating individuals working together toward the common good. The political extension of friendship is between equals, giving a chance for a dialogue on equal grounds. Jang (2018) underlines that Aristotle’s concept of friendship between citizens, as a concord (homonoia), aims at promoting the common good and philia as a virtue, aimed at living well together, preserving the unity of the state. Schwarzenbach (2005) argues that alongside the fundamental democratic values of “freedom” and “equality,” political or civic friendship emerges as a crucial third value deserving of emphasis. The idea of the rule of “people” presupposes members of that people are equal and not enemies, contrary to horizontal affective polarization. Friendship between citizens (politike philia) is a necessary condition for the justice of any political regime. According to Schwarzenbach, however, individual friendship is about personal liking, intimate knowledge, and close emotional ties; political friendship, however, necessarily operates orderly construction of political institutions, rights, and social practices. This orderly construction of political institutions, rights and social practices requires a comprehensive understanding of political friendship (Schwarzenbach, 2005). However, as underlined by Marcus, in democratic societies, many norms are sources of dispute, particularly in a polarized society; violation of critical norms, intentionally or not, challenges safe cooperative behavior and leads to a rise in anger (2023).

philia offers a counterbalance to these divisive tendencies by promoting mutual goodwill and constructive engagement. Philia’s community-generating power aligns with the goals of deliberative democracy, fostering solidarity even among individuals with opposing views (Cooke, 2018). Additionally, Noelle-Neumann’s (1984) “spiral of silence” theory underscores the importance of creating environments where diverse voices can be heard without fear of marginalization (Noelle-Neumann, 1984). A flourishing democracy fosters avenues for civic involvement and social interaction that improve its residents’ overall quality of life. Public forums, cultural events, and community projects cultivate a sense of belonging and happiness, enhancing individual lives while strengthening the social fabric. A fundamental aspect of philia is the capacity to listen and empathize with others, cultivating an atmosphere of mutual understanding and respect. These relational dynamics are critical for fostering trust and cooperation, integral to the principles of deliberative democracy. philia transcends individual relationships, forming a basis for collective engagement where a shared commitment to the common good drives dialogue.

Habermas (1996) asserts that communicative practices grounded in mutual respect and the free exchange of ideas are not merely advantageous but foundational to the legitimacy of democratic governance. philia enriches this principle by ensuring that interactions are guided by an ethical commitment to valuing and understanding others rather than remaining purely transactional. Such practices enable the creation of democratic spaces where diverse voices are heard and deeply integrated into decision-making processes. This integration surpasses token representation, ensuring outcomes that genuinely reflect the collective will through inclusive and reasoned deliberation. By connecting the empathetic and relational values of philia with Habermas’s framework of communicative action, we can see the moral and practical synergy between interpersonal ethics and democratic legitimacy. philia transforms dialogue into more than the exchange of arguments; it becomes a process of mutual enrichment and co-creation, bridging differences to achieve collective judgment through authentic understanding. This relational foundation highlights that democratic governance is not merely procedural but also an expression of shared human values rooted in the concept of philia. Building on this, Benhabib (1992) introduces the concept of the “generalized other,” which aligns deeply with philia by emphasizing mutual respect, understanding, and goodwill. The “generalized other” framework advocates treating individuals as unique contributors to the democratic process rather than reducing them to representatives of group identities. This resonates with Aristotle’s articulation of philia, which calls for valuing others for their own sake, fostering relational bonds beyond private friendships to unite communities and political entities. Benhabib’s concept challenges the homogenization of individuals into rigid group categories, emphasizing instead the recognition of each person’s individuality and agency. Similarly, philia prioritizes an ethos in which individuals are appreciated as distinct contributors whose experiences and voices enrich collective efforts. By honoring these unique perspectives, deliberative democracy transcends procedural fairness, creating spaces of inclusion and collaboration grounded in empathy and respect.

The alignment between philia and the “generalized other” fosters a deliberative environment where relationships are built on mutual admiration, trust, and a shared commitment to the common good. This approach acknowledges that a democracy infused with philia thrives when it values the distinctiveness of its participants, transforming democratic spaces into arenas of meaningful connection and collective enrichment. Such spaces promote more prosperous and more authentic decisions, reflecting the ethical integrity and legitimacy essential to deliberative democracy.

philia’s listening, empathy, and respect principles remain at the heart of democratic dialogue, offering a framework for creating collaborative and inclusive spaces. By embracing these values, deliberative democracy not only achieves procedural legitimacy but also strengthens its moral foundation, ensuring outcomes that reflect both the collective will and the shared purpose of its participants. This approach aligns with the Somatic Marker Hypothesis (Damasio, 1996), which demonstrates that emotions are essential to decision-making by associating choices with positive or negative outcomes. In deliberative settings, emotional markers guide participants in evaluating options that resonate with personal and collective values. This connection reinforces philia’s emphasis on relationships and shared care as central to democratic engagement. Additionally, Appraisal Tendency Theory (Lerner and Keltner, 2000) highlights how specific emotions, such as empathy, shape individuals’ perceptions and interpretations of information. Empathy, a cornerstone of philia, enhances participants’ ability to engage with diverse perspectives, while emotions like fear or anger influence risk assessment and agency. Incorporating these emotional tendencies enriches deliberative processes by infusing them with depth and nuance, moving beyond rigid rationality.

The Dual-Process Theory (Kahneman, 2011) further underscores the role of emotions in decision-making. While System 1 (intuitive and emotional) processes guide rapid judgments, System 2 (deliberative and rational) thinking complements these responses by providing analytical depth. Recognizing the interplay between these systems ensures that deliberative models respect the emotional underpinnings of human cognition. Rather than opposing rationality, emotions complement it, shaping how individuals process information, make decisions, and connect with others. As Nussbaum (2001) argues, emotions are evaluative judgments reflecting what individuals value most. Similarly, Marcus (2002) highlights the motivational role of emotions in political engagement, noting that feelings inspire civic participation and collective action. These insights underscore the compatibility of emotions with rational deliberation and their essential role in fostering genuine democratic participation. Moreover, the Affective Intelligence Theory (Marcus et al., 2000) also emphasizes that emotions like anxiety and enthusiasm regulate political behavior. Anxiety prompts individuals to seek new information, fostering critical engagement, while enthusiasm reinforces existing commitments and motivates action. This dual role demonstrates how emotions enhance deliberation and mobilization in democratic contexts. The Social Intuitionist Model (Haidt, 2001) further illustrates how emotional intuitions drive moral judgments, often preceding rational deliberation. By recognizing this sequence, deliberative democracy can create spaces where emotional responses are valued alongside logical arguments, fostering inclusive and meaningful dialogue. Emotional intelligence is another essential component of effective deliberation. Defined by Goleman (1995) as the ability to recognize, understand, and manage one’s emotions while empathizing with others, emotional intelligence is critical for conflict resolution, consensus-building, and strengthening interpersonal relationships. Emotional intelligence in deliberative democracy aligns with philia’s relational values, underscoring the importance of human connections alongside logical arguments in establishing democratic legitimacy.

Fostering emotional intelligence creates spaces where participants feel genuinely included and respected. This approach bridges divides, reduces polarization, and builds trust—outcomes that directly counter the exclusionary tendencies of hyperrational frameworks. Additionally, theories such as the Broaden-and-Build Theory (Fredrickson, 2001) highlight how positive emotions like hope and gratitude enhance creative problem-solving and collaboration, making them indispensable in deliberative settings. The principle of collective judgment is central to democratic legitimacy, as noted by Habermas (1996), who argues that the “collective judgment of the people” forms the basis of democratic authority. This principle reflects the ethical dimensions of philia, which emphasizes collaboration, mutual benefit, and striving toward the common good. Aristotle’s framework of philia further supports this view, as it encompasses relationships based on mutual advantage, pleasure, and admiration (Aristotle, 2011). In a democracy, these relationships translate into institutions and practices that serve collective interests, enrich civic participation, and promote virtuous governance.

The role of emotions in shaping philia has been increasingly recognized in political science and social psychology. Anger, disgust, and anxiety, particularly, function as critical determinants of group cohesion, political engagement, and intergroup relations, often reinforcing or undermining the social structures that sustain philia. Research suggests that anger can enhance group solidarity and political engagement, fostering a sense of belonging and commitment within ideological or partisan communities; however, it also contributes to political polarization and the erosion of cross-group friendships (Wollebæk et al., 2019). Anxiety, by contrast, has a dual effect: while it can motivate political withdrawal and social avoidance, it can also drive radicalization under specific conditions, leading individuals to seek security in closed, ideologically homogeneous communities (Baboš et al., 2019). Disgust, the most socially divisive of these emotions, is linked to out-group rejection, xenophobia, and heightened authoritarian attitudes, which pose significant barriers to inclusive social bonds and pluralistic philia (Fournier et al., 2021). Moreover, the strategic use of these emotions in political communication further manipulates social cohesion; for instance, anger is deliberately invoked in political campaigns to mobilize voters, while emotions like “being moved” (kama muta) strengthen social ties within ideological circles (Grüning and Schubert, 2022). These findings underscore the pivotal role of emotions in shaping philia, highlighting their capacity to foster solidarity within groups while also serving as mechanisms for exclusion, political division, and ideological reinforcement. Ultimately, emotions function as both the glue that holds social bonds together and the fault lines that fracture them, making them an indispensable focus in the study of political and social dynamics.

Thus, affective polarization creates intergroup hostility, a sense of moral superiority, and increased social distance, leading to emotional reactions that fuel outgroup biases. Negative emotions such as anger and disgust serve to reinforce intergroup hostility. The political party supporters considered the “most distant” are viewed negatively through the lens of stereotypes rather than individual actions, which highlights the emotional repercussions of perceiving an opposing party supporter unfavorably. Policy disagreements signal partisan identity, heightening emotional reactions. It is important to note that affective polarization manifests differently depending on the context and specific issues at hand, indicating that the impact of polarization and partisan identity is not always consistent across various topics. The interplay between philia and the emotional dimensions of polarization is crucial, highlighting the need for strategies that mitigate affective polarization and foster constructive democratic deliberation.

The country’s societal fabric has long been marked by deep divides, crystallizing in an intense center-periphery cleavage and cultural struggles, or kulturkampfs, between secular and conservative segments (Kalaycıoğlu, 2012). These divisions, rooted in the rapid and late modernization efforts of state elites, have been further amplified by populist leaders who exploit these cultural and social divides (Çarkoğlu and Kalaycıoğlu, 2021; Mardin, 1973). Over time, societal rifts have manifested in significant periods of political turmoil. During the 1970s, Türkiye came close to civil war as ultraright and ultraleft factions clashed violently, leading to a military coup in 1980 (Sayarı, 2010). Another period of upheaval followed the Kurdish resurgence, which between 1980 and 2020 claimed over 30,000 lives, predominantly in the Southeastern region, and heightened nationalist sentiments among Turkish and Kurdish communities (Barkey and Fuller, 1997; Tezcür and Gürses, 2017). These cleavages—secular versus conservative, left versus right, and Kurdish versus Turkish nationalism—constitute Türkiye’s primary axes of political contestation.

These divisions have intensified recently. Under the 22-year single rule of the AKP, the conservative party with affective polarization has reached unprecedented levels. Studies reveal that Türkiye ranks highest in affective polarization among 53 surveyed countries, followed by Hungary, Bulgaria, and Montenegro (Orhan, 2022). Our earlier surveys highlight the extent of polarization, as supporters of different political parties demonstrate profound social distance, unwillingness to cooperate, strong moral prejudices, and low political tolerance (Erdoğan and Uyan-Semerci, 2018; Erdoğan and Uyan-Semerci, 2022). Political allegiance is increasingly defined by animosity toward opposing parties, a phenomenon known as negative partisanship (McCoy et al., 2018). This entrenched hostility undermines opportunities for cross-party collaboration and deepens societal divisions.

Several global and domestic factors contribute to Türkiye’s high level of polarization. Globally, challenges such as the 2008 financial crisis, immigration pressures, climate change, and the COVID-19 pandemic have heightened societal tensions and deepened existing divides (Carothers and O’Donohue, 2020). Domestically, long-standing ideological conflicts between secularists and Islamists, epitomized by debates over the wearing of headscarves in public institutions, serve as a recurring source of division. Similarly, ethnic tensions between Turks and Kurds, reflected in disputes over bilingualism and cultural representation, further exacerbate polarization (Erdoğan and Uyan-Semerci, 2022). These domestic issues underline the entrenched nature of ideological and identity-driven divides and resonate deeply within the Turkish socio-political context, providing fertile ground for the dynamics of affective polarization explored in this study. By incorporating these context-specific factors, we aim to highlight how such issues contribute to the broader patterns of othering and democratic challenges examined in this research.

Türkiye’s institutional framework has also played a pivotal role. The 2017 adoption of a presidential system concentrated executive power on the president, elected by a slim majority (52% of voters). The “perils of presidentialism,” a well-documented phenomenon, have been vividly illustrated in Türkiye, where this system has heightened the polarizing effects of executive dominance (Linz, 1990). With their winner-takes-all dynamics, majoritarian electoral systems further entrench political divisions (Çakır, 2020). Additionally, Türkiye has faced a series of referendum-like elections since 2007, compelling voters to align for or against a single figure—Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Each election deepens the divide between opposing camps, inflamed by political leaders’ divisive rhetoric, which fosters an “us versus them” narrative. Turkish politicians exacerbate societal polarization by exploiting cultural, ideological, and ethnic divisions through divisive rhetoric, such as framing opponents as existential threats or elites disconnected from the people (Aydın-Düzgit and Balta, 2019; Kocapınar and Kalaycıoğlu, 2024).

Nationalistic appeals, religious identity politics, and binary campaign messaging deepen divides, while partisan media and social media echo chambers amplify their narratives (Bozdağ and Koçer, 2022; Erçetin and Erdoğan, 2023). This rhetoric fosters distrust, entrenches hostility between groups, and undermines social cohesion and democratic norms (McCoy et al., 2018). Moreover, the media and digital platforms in Türkiye deepen societal polarization by amplifying biases and fostering echo chambers. Partisan media distorts information to favor specific factions, reducing trust in news institutions, while the shift to fragmented digital news sources has made the information landscape vulnerable to manipulation (Bulut and Yörük, 2017). Social media platforms like Twitter escalate mundane events into political debates, such as a pop star’s outing highlighting divides over LGBTI+ issues. In contrast, political trolling by pro-government entities fosters censorship and polarization (Bozdağ and Koçer, 2022). Ural (2023) argues that Turkish media actively contributes to affective polarization by framing political discourse through an Islamist/secularist divide. He concludes that media-driven affective intensities shape citizens’ emotional responses to political events.

Previous studies showed that emotions played a crucial role in the emergence of polarized political environment in Türkiye. Erişen and Erdoğan (2019) found that perceived threat and prejudice significantly explain shifts in political intolerance during the 2015 Turkish elections. Their study, using a nationally representative survey, demonstrated that citizens who felt threatened by opposing political groups were more likely to endorse authoritarian measures and limit civil liberties. Similarly, Erişen (2018) also found that while anger toward outgroups increases political intolerance, anxiety can sometimes lead to deliberation and reassessment of political stances.

In a recent study, Erişen (2024) examines the role of emotions in shaping populist attitudes in Turkey, demonstrating that anger is a key driver of right-wing populism, reinforcing authoritarian and nationalist tendencies. In contrast, enthusiasm exerts a weaker influence on populist attitudes, suggesting that emotional triggers vary in their political impact. Furthermore, political ideology mediates these effects, with right-wing voters being more susceptible to anger than enthusiasm. This study underscores the centrality of anger in mobilizing populist movements in Turkey, reinforcing the emotional dimension of political intolerance. Similarly, Erden (2024) explores how right-wing Turkish politics capitalizes on resentment, particularly through narratives of national victimhood that frame elites as corrupt adversaries of the people. By mobilizing anger and fear, such rhetoric deepens polarization and erodes democratic tolerance. Erden’s analysis highlights how polarization is not merely a social byproduct but a strategically cultivated political tool, emphasizing the role of emotional mobilization in shaping contemporary political dynamics. Kurtoğlu Eskişar and Çöltekin (2022), using machine learning techniques to analyze parliamentary speeches in Turkey between 2011 and 2021, found that anger dominates political rhetoric, especially from the opposition, whereas the ruling party maintains more stable emotions, despite its populist branding.

Our analyses are based on a survey conducted in November–December 2020 under pandemic conditions. The survey was part of a larger project that targets developing Strategies and Tools for Mitigating Polarization in Türkiye, aka TurkuazLab.1

Affective polarization begins with delineating an “other”—party elite/supporters as groups or individuals perceived as fundamentally different or opposed. In the United States, this is often straightforward, with Democrats and Republicans serving as binary opposites. However, in Türkiye’s multiparty context, the operationalization of “other/most distant” is more intricate due to the diversity of political parties and their constituencies.

To address this complexity, we utilized a two-step process. First, respondents were asked to rate their closeness to supporters of various political parties on a five-point scale, focusing on their emotional and ideological affinity rather than the parties themselves. This approach centered on interpersonal and social perceptions rather than abstract party ideologies. Participants then identified their favorite party constituency—the group they rated highest. In cases of ties, they specified their primary affiliation, ensuring clarity in their in-group identification. Respondents were also prompted to describe their attachment to this preferred group, capturing the intensity and breadth of in-group affiliation.

Following this, respondents were asked to identify the party constituency they perceived most distant from their group-horizontal affective polarization. We emphasized relational dynamics over institutional divisions by framing questions around party supporters rather than parties. This identified “other” became the focal point for subsequent measures of affective polarization, grounding the analysis in interpersonal rather than purely ideological terms.

Based on survey data collected in 2020, our analysis highlights persistent patterns in affective polarization in Türkiye. Consistent with findings from our previous studies (Erdoğan and Uyan-Semerci, 2018), HDP supporters were identified as the most distant out-group, with over 40% of respondents perceiving them as the primary “other.” This trend, which peaked in 2017 before slightly declining in 2020, reflects the enduring stigmatization of the HDP and the evolving nature of partisan hostility.

Perceptions of out-group hostility varied significantly among constituencies. For AKP supporters, CHP and HDP voters were the most distant groups. CHP supporters, in turn, viewed AKP and HDP constituencies as their primary out-groups. Meanwhile, HDP voters expressed equal hostility toward the AKP and MHP supporters. Interestingly, the two nationalist parties, MHP and İYİ Party, displayed divergent patterns: MHP supporters ranked CHP as their second most distant group, while İYİ Party supporters primarily regarded AKP supporters as the second most distant.

After determining which party supporters are regarded as the most distant, affective polarization as a type of othering is measured by social distance, moral superiority, and political intolerance.

Social distance was assessed using a series of questions adapted from Bogardus (1925) to evaluate respondents’ willingness to engage with out-group supporters in various social contexts. This well-established measure examines attitudes toward social interactions of increasing closeness, making it an effective tool to study intergroup relationships. While the term “social distance” gained additional connotations during the COVID-19 pandemic, where it was often associated with “spatial distancing” (Thunstrom et al., 2021), its traditional use remains highly relevant for understanding intergroup dynamics. Respondents were presented with hypothetical encounters to assess their willingness to interact with out-group supporters. These encounters ranged from casual neighborly relations to more intimate and impactful relationships, such as allowing their children to play together. This stepwise design allowed us to construct a gradient of social distance, revealing nuanced intergroup attitudes. The findings reveal substantial social distance between in-groups and out-groups, affecting the most distant party supporters in Turkish society. Nearly 75% of respondents said they would oppose their children marrying someone supporting an opposing political group. Similarly, 72% of participants were unwilling to engage in business with the supporters of the most distant party. The reluctance extended to interpersonal relationships, with 67% disapproving of friendships between their children and those of out-group supporters and 61% expressing discomfort with having supporters of the most distant party as their neighbors. These results reflect entrenched barriers to social interaction and a pervasive unwillingness to engage with those perceived as politically different. To quantify these attitudes, we constructed a social distance index ranging from 1 to 4, which revealed an average score of 3.0 (SD = 0.8), with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.91, underscoring the high degree of division in interpersonal and community contexts.

Moral superiority, a critical dimension of affective polarization, refers to the belief that one’s group holds higher moral values than the out-group, often manifesting as prejudice and stereotyping (North and Fiske, 2015). We developed a comprehensive set of positive and negative adjectives based on prior research to measure this. Respondents were tasked with assigning these adjectives—including descriptors like “patriotic,” “honorable,” “arrogant,” and “selfish”—to both their in-group (supporters of their own party) and out-group (supporters of the most distant party). Moral superiority emerged as a significant dimension of affective polarization, with respondents overwhelmingly attributing positive traits such as patriotism, honor, and integrity to their in-group. Conversely, negative descriptors like arrogance, selfishness, and bigotry were consistently assigned to out-groups. These patterns suggest a deeply ingrained tendency to view out-group members’ moral and ethical qualities in a negative light.

We constructed the moral superiority index by adding the negative adjectives assigned to out-group supporters from the positive adjectives attributed to in-group supporters. This methodological approach allowed us to capture the intensity of perceived moral differences and the extent to which respondent’s exclusively associated positive traits with their in-group and negative traits with their out-group. By aggregating these associations, we gained valuable insights into the crystallization of affective polarization at the moral and emotional levels. Notably, only a small proportion of respondents refrained from making such attributions, highlighting the pervasive nature of moral judgments in polarized societies. The moral superiority index, which ranged from 0 to 12, exhibited a mean of 10.4 (SD = 2.3) and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.93, illustrating strong intergroup biases reinforcing affective polarization.

Political tolerance was evaluated through respondents’ willingness to extend fundamental political rights to the most distant party supporters and out-group supporters. Drawing on Gibson (2006) framework, we included questions about respondents’ attitudes toward organizing rallies, holding public meetings, and participating in elections. This dimension is critical for understanding how affective polarization impacts democratic norms, as tolerance for dissent and opposition is a cornerstone of democratic governance (Almond and Verba, 1963; Dahl, 1998).

In addition to these conventional measures, we introduced items probing attitudes toward more intrusive measures, such as surveillance and phone tapping of out-group members. These questions were designed to assess extreme manifestations of political intolerance, which, while less common in established democracies, are particularly relevant in Türkiye’s polarized context. By aggregating responses, we constructed a composite political tolerance index, highlighting the extent and intensity of political intolerance.

Political intolerance is a critical dimension of affective polarization as a type of othering, with respondents demonstrating varying levels of opposition to the political rights of out-group members. For example, 37% of participants opposed the right of out-group members to organize meetings, while 41% were against their participation in elections—a cornerstone of democratic governance. Additionally, 40.5% disagreed with out-group members organizing rallies, and 36.9% expressed opposition to press releases in their localities. Notably, 25.8% supported surveillance measures, including phone tapping, with an alarming 47.8% explicitly endorsing such actions for security reasons.

These findings indicate a troubling acceptance of restrictions on fundamental political freedoms, revealing extreme mistrust and hostility. The patterns depicted in the graph underscore the multifaceted nature of political intolerance, with significant resistance to even fundamental democratic rights like education tailored to specific group needs (35.1%) and press freedoms (36.9%). Such attitudes highlight the pervasive impact of affective polarization on democratic norms and the need for targeted interventions to rebuild trust and inclusivity. The political intolerance index, ranging from 1 to 5, recorded an average score of 3.1 (SD = 1.2) with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89, signaling significant challenges to inclusive governance (Figure 1).

These three dimensions of affective polarization, namely social distance, moral superiority, and intolerance are correlated to a degree (rSD-MS = 0.24, rSD-INTOL = 0.48, and rMS-INTOL = 0.17). These three variables produced a single-dimension factor explaining 53% of the total variation. Using the factor score of these different indicators, we constructed an index of affective polarization as a type of othering at the individual level.

Affective polarization understood as a type of othering, represents a profound challenge to democratic engagement and cohesion. This conceptualization highlights how political opponents are not merely seen as holding different views but are often dehumanized, viewed with moral disdain, and excluded from the scope of mutual goodwill essential for democratic dialogue. In this context, the experiment was designed to capture this process’s emotional and cognitive dimensions—specifically how individuals perceive and react to political outgroup members in polarized discussions. By focusing on emotions, the study provides critical insights into polarization’s visceral, often overlooked, drivers. Emotions like anger, disgust, and frustration are pivotal in reinforcing divisions, deepening moral hierarchies, and eroding the relational foundation of democracy, philia. As a form of civic friendship, philia is indispensable for sustaining dialogue, fostering mutual understanding, and upholding democratic principles. By examining these emotional responses in a controlled experimental setting, this study bridges the theoretical framework of othering with its real-world implications, offering a nuanced perspective on why affective polarization undermines democracy and how it might be mitigated.

This study employed a scenario-based experimental design to examine participants’ emotional and cognitive responses to polarized discussions on contentious political topics. The experiment aimed to simulate real-world political debates in Türkiye, where ideological divisions shape public discourse.

Participants were asked to imagine themselves as neutral observers of a group discussion involving supporters of different political parties. These discussions centered on four politically and socially significant issues—two related to global crises and two to domestic political cleavages.2

Global crises:

• Global warming

• The presence of Syrians in Türkiye (shortened as Syrians)

Domestic cleavages:

• The wearing of headscarves by civil servants (shortened as Headscarves)

• Using non-Turkish language in government offices (shortened as Bilingualism)

The domestic topics were chosen because they represent deep-seated social and political divisions, whereas global crises were included as potential “islands of agreement” where polarization might be less intense.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four scenarios, ensuring that the number of respondents per scenario was equal to maintain balance across conditions. In each scenario, one individual (the “detractor”) was portrayed as stubbornly defending their viewpoint, interrupting others, and rejecting alternative perspectives in an uncivilized way. The exact wording is used in each topic without mentioning their argument/position, but just the detractor’s behavior.

After being assigned to a scenario, participants completed the following tasks:

• Partisan attribution: identify the perceived partisan identity of the detractor based on their behavior and the topic of discussion.

• Emotional response: select one emotion from a predefined list of eight options: anger, disgust, joy, fear, hope, pride, sadness, and frustration.

• Emotional intensity: rate the intensity of their selected emotion on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = low intensity, 10 = high intensity).

This randomized design ensures that any observed differences in emotional and cognitive responses are driven not by self-selection biases but by experimental manipulations.

Accordingly, we expect that:

H1: Participants will disproportionately assign the detractor role to supporters of the other/“most distant” political party

H1a: Participants’ propensity to assign the detractor role to supporters of the other/“most distant” political party varies across the issues

H2: Affective Polarization deepens intergroup biases, leading participants to disproportionately assign the detractor role to “other”/“most distant” party supporters

H2a: The effect of affective polarization on the effect of polarization on the propensity of assigning the detractor role to supporters of the other/“most distant” party supporters varies across the issues.

H3: Affective Polarization increases the probability of reporting negative emotional responses when participants perceive the detractor as an opposing party supporter.

H3a: Affective Polarization’s effect on reporting negative emotional responses when participants perceive the detractor as an opposing party supporter varies across issues.

H4: The intensity and direction of emotions will vary according to the assigned partisan identity of the detractor.

H4a: The intensity and direction of emotions will vary according to the detractor's assigned partisan identity and across the issues.

For data analysis, we employed regression models to examine the effects of affective polarization on partisan attribution and emotional responses. Given the categorical nature of the dependent variable in the detractor attribution task, we used multinomial logistic regression to assess the likelihood of assigning the detractor role to a specific party supporter. Additionally, logistic regression was used to analyse the probability of respondents reporting negative emotions, while Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression was applied to measure the intensity of emotional responses on a continuous scale.

Regression analysis was chosen as the primary statistical approach because it allows for the estimation of relationships between predictor variables (e.g., affective polarization levels, issue type, demographic factors) and key outcome measures, while controlling for potential confounders. Other analytical techniques, such as ANOVA, were considered but deemed less suitable due to the need for covariate adjustments and interaction modeling. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS and STATA ensuring robust estimations and reproducibility.

The above Table 1 shows the respondents’ perceptions of which party a hypothetical individual supporting specific issues (e.g., global warming, headscarf, Syrians, bilingualism) is more likely to be associated with and indicates that some parties have stronger associations with some specific issues. The detractor in the headscarf-related discussion is related to the AKP. Similarly, the leading answer became the same party in the discussion about the presence of Syrians in Türkiye. In the scenario of global warming, the detractor is associated with the CHP, whereas the HDP is associated with bilingualism discussion, likely reflecting its association with pro-minority rights. This figure shows that not all issues are equally associated with each party’s supporters.

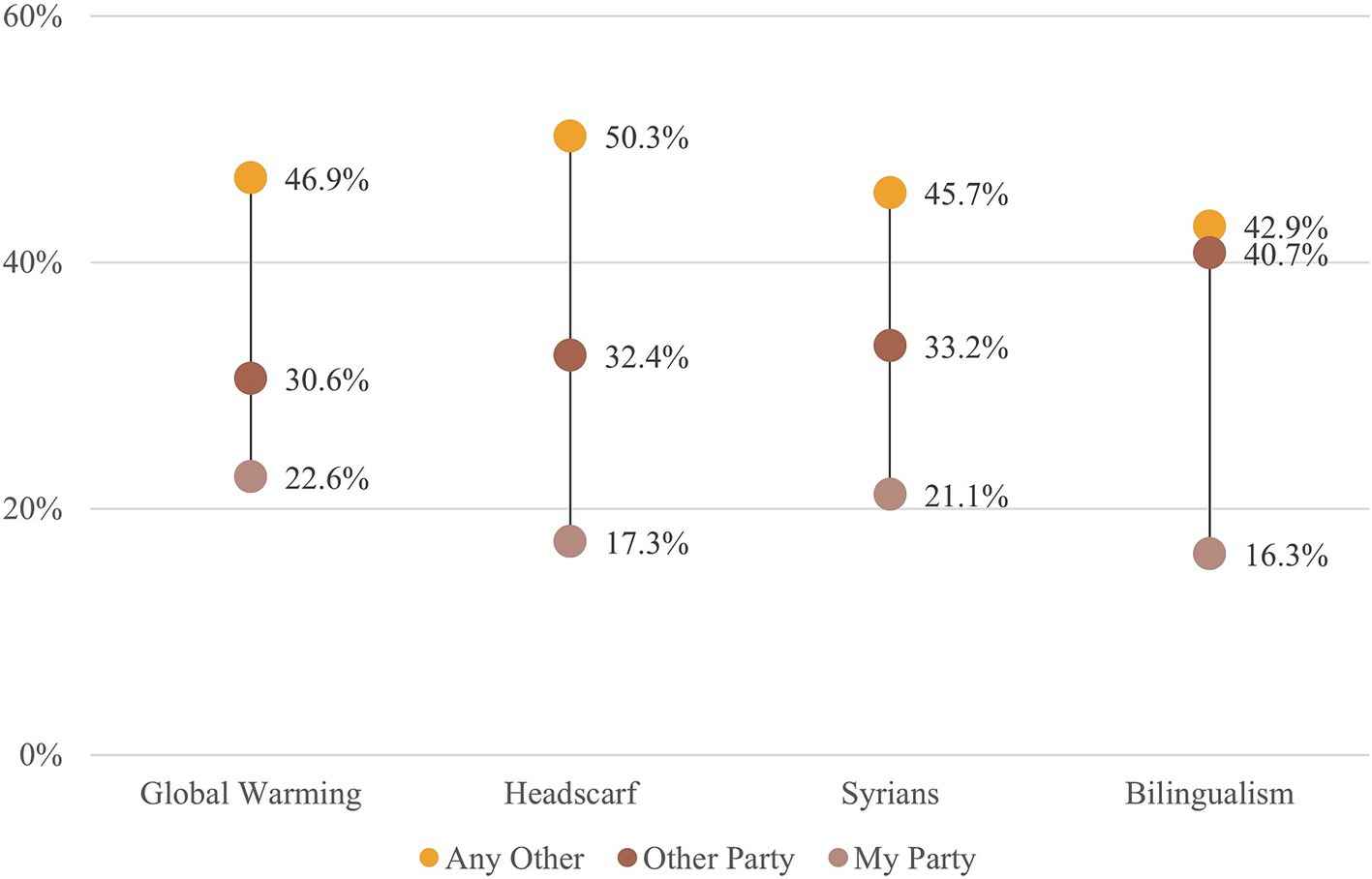

This figure examines how respondents assign the role of the detractor on four key issues (Figure 2). Respondents could attribute the detractor to their own party, the other party (a party they feel most ideologically distant from), or any other party. The findings reveal significant patterns in perceived political opposition, underscoring the polarization dynamics and issue-based alignment within Türkiye’s electorate.

The “Any Other” category dominates all four issues, suggesting that respondents frequently attribute opposition to parties beyond their own or their most distant rival. This trend is particularly notable for global warming, the headscarf, and bilingualism, indicating that these issues are broadly contested across the political landscape. The prominence of “Any Other” as the perceived detractor reflects the dispersed nature of political opposition, where respondents do not associate opposition with a single party but instead with a broader range of parties outside the primary political divide. This highlights the fragmented nature of Türkiye’s political system; based on the stated issue, multiple parties are perceived as detractors.

The “Other Party” category accounts for a substantial share of responses, particularly on polarizing topics like bilingualism, global warming, and Syrians, emphasizing the centrality of out-group antagonism in shaping perceptions of political opposition. This pattern reflects the salience of identity and nationalist politics, as issues such as bilingualism are strongly linked to cultural and ideological divides. Interestingly, respondents seldom associate their party with the role of detractor, demonstrating a clear pattern of in-group favoritism. However, bilingualism shows a slightly higher level of detractor attribution to respondents’ own parties than other issues, hinting at potential internal divisions or ambivalence within political groups on this specific issue. These findings support our hypotheses H1 and H1a, which state that participants are more likely to associate the detractor role with supporters of their most distant party, especially on contentious topics like bilingualism and Syrians. This aligns with the expected dynamics of affective polarization, where the “Other Party” elicited significant out-group attribution (Figure 3).

The above-presented results indicate a stark contrast in emotional reactions based on the detractor’s perceived party affiliation. The “Other Party” category elicited the highest negative emotions (over 80%), underscoring the intensity of out-group hostility in polarized political environments. This overwhelming negativity suggests that individuals are more likely to view detracting behavior from ideological opponents critically and antagonistically. Similarly, the “Any Other” category also elicited predominantly negative reactions (over 60%), though with a notable increase in neutral and uncertain responses compared to the “Other Party” category. This finding indicates that while general detractors are still met with negativity, the intensity of emotional reactions is somewhat moderated when the detractor is not tied to a primary political rival.

When the detractor was associated with “My Party,” the emotional responses showed a more nuanced pattern. Negative emotions decreased significantly compared to the other categories, while positive emotions were more prevalent (over 20%). This reflects the influence of in-group favoritism, as respondents tend to interpret similar domineering behavior from their party members in a less critical or favorable light. Participants reported significantly higher negative emotional intensity when the detractor was associated with the “Other Party,” reflecting out-group hostility. Conversely, detractors from “My Party” elicited more positive or neutral emotional responses, highlighting the role of partisanship in shaping emotions. These findings confirm our H3: Participants will report higher levels of negative emotions when they perceive the detractor as representing the opposing party (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Intensity and direction of emotions toward detractors from different parties (averages, −10 to 10).

According to the above figure, detractors associated with the “Other Party” elicited the strongest negative emotional intensity, with a mean score of −6.89 (s.e. = 0.15). This indicates that respondents experience the most intense hostility toward individuals from ideologically distant parties, reflecting the deeply polarized political environment. The heightened negativity in this category underscores the role of out-group hostility, where the actions of rival parties are viewed not only as disagreeable but as emotionally provocative. This finding aligns with broader patterns of affective polarization, where ideological opponents are met with strong emotional disdain.

In contrast, detractors affiliated with “My Party” evoked a positive emotional intensity, with a mean score of 2.34 (s.e. = 0.36). This reflects in-group favoritism, where respondents interpret domineering or polarizing behavior from their political group in a more favorable light. Positive emotional intensity suggests that individuals are more likely to excuse or support similar behaviors when they perceive the detractor as aligned with their values and beliefs. Meanwhile, detractors in the “Other” category—associated with general or less clearly defined parties—elicited moderate negative emotions (−5.77, s.e. = 0.15), suggesting disapproval that is less intense compared to “Other Party.” These findings collectively demonstrate that emotional reactions are strongly influenced by the perceived affiliation of the detractor, with the most significant disparity observed between rival and in-group affiliations. Accordingly, our H5, which states that the intensity and direction of emotions will vary according to the assigned partisan identity of the detractor, is supported (Table 2).

Table 2. Determinants of association of detractors from different parties (multinomial regression, “the other” is the baseline).

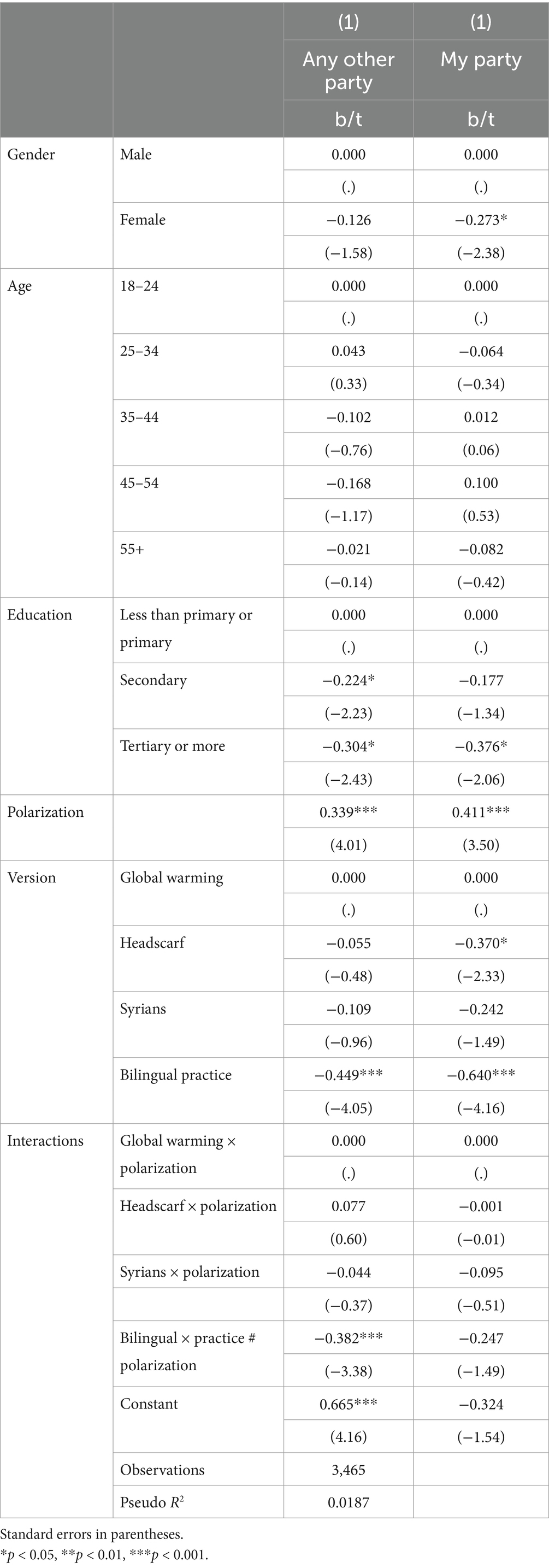

The multinomial regression analysis examines the factors influencing respondents’ choices to assign the detractor role to either “My Party” or “Any Other Party,” using “Other Party” as the baseline category. Independent variables include demographic characteristics (gender, age, education), polarization, issue-specific topics (versions), and interactions between issue versions and polarization. These results illuminate how demographic and ideological factors shape perceptions of political detractors in a polarized context.

Gender is a significant factor when evaluating “My Party” as the detractor. Women are significantly less likely than men to assign the detractor role to their own party (β = −0.273, p < 0.05), indicating a stronger sense of loyalty or a more favorable perception of their in-group. Interestingly, gender differences are insignificant when assigning the detractor role to “Any Other Party,” suggesting that gendered differences are more salient in evaluations of in-group behavior.

Education also plays a critical role in shaping perceptions. Respondents with tertiary education are less likely to assign the detractor role to “My Party” (β = −0.376, p < 0.05) and marginally less likely to assign it to “Any Other Party” (β = −0.304, p = 0.07). This suggests that higher education correlates with greater introspection and ideological nuance, particularly when evaluating in-group behavior. The more negligible, marginally significant effect for “Any Other Party” suggests that education’s influence is stronger in moderating in-group criticism rather than out-group evaluations.

Polarization significantly impacts detractor assignments. Higher affective polarization increases the likelihood of assigning the detractor role to both “My Party” (β = 0.339, p < 0.01) and “Any Other Party” (β = 0.411, p < 0.01). This underscores the role of polarization in framing political perceptions through a partisan lens, amplifying divisions within and between groups.

Issue-specific dynamics reveal notable patterns. The topic of bilingual practices substantially decreases the likelihood of assigning the detractor role to “My Party” (β = −0.640, p < 0.001) and “Any Other Party” (β = −0.449, p < 0.001). This indicates that identity-related issues elicit unique ideological responses, potentially shifting focus away from traditional partisan dynamics. Moreover, the interaction between bilingual practices and polarization significantly affects the likelihood of assigning the detractor role to “Any Other Party” (β = −0.382, p < 0.01). This suggests that polarization exacerbates the framing of detractors within partisan boundaries, especially when identity-related issues dominate the discussion.

According to these findings, we can say that our expectation about the role of affective polarization in assigning the role of detractor to “other/party” supporters (H2) is not supported because participants with higher levels of affective polarization scores assigned this role to their co-partisans and any other party’s supporters. Meanwhile, the same findings also suggest that polarization’s impact is heightened for identity-related issues compared to universal topics like global warming, confirming, or H2a, leaving a role in the impact of issue-specific factors (Table 3).

The above-presented logistic regression results examine the predictors of assigning negative emotions to a detractor during a politically charged discussion. The analysis includes demographic variables, education, perceived polarization, issue-specific topics (versions), detractor partisan affiliation, and interaction terms between polarization and detractor affiliation.

This analysis shows that topics strongly influence the assignment of negative emotions. Identity-related issues, such as Syrians (β = 0.671, p < 0.01) and bilingual practices (β = 0.834, p < 0.01), significantly increase the likelihood of negative emotional responses compared to the baseline topic of global warming. These findings highlight the heightened emotional resonance of cultural and ethnic issues in Türkiye’s polarized context, where such topics evoke stronger emotional reactions than less identity-driven issues.

Meanwhile, the detractor’s partisan affiliation is a major determinant of negative emotional responses. Respondents are significantly more likely to assign negative emotions to detractors from the “Other Party” (β = 0.446, p < 0.01), indicating out-group hostility. Conversely, detractors from “My Party” are significantly less likely to evoke negative emotions (β = −2.773, p < 0.01), underscoring the strength of in-group favoritism. This reflects a strong partisan divide where respondents are more forgiving of in-group behavior and harsher toward perceived out-group threats.

While the direct effect of polarization on negative emotions is not statistically significant (β = 0.068), its interaction with the detractor’s affiliation with the “Other Party” is significant (β = 0.336, p < 0.05). This suggests that in polarized individuals, out-group hostility intensifies, with heightened negative emotions directed toward detractors associated with rival parties. However, polarization does not significantly alter leniency toward in-group detractors, indicating that in-group favoritism remains consistent across varying levels of polarization.

These findings support our hypothesis that participants will report higher levels of negative emotions when they perceive the detractor as representing the opposing party (H3) and the moderating role of the issue (H3a). Polarization’s interaction with identity-related issues (e.g., bilingualism) resulted in stronger negative emotions. At the same time, its effect was less pronounced for topics like global warming, indicating variability across issues (Table 4).

The above table presents the results of an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis predicting the intensity and direction of respondents’ emotional reactions to a detractor in a politically charged discussion. The dependent variable reflects the positivity or negativity of these emotional responses, with higher values indicating more positive emotions. The predictors include demographic characteristics, education, polarization, issue versions, the partisan affiliation of the detractor, and interaction effects. The results highlight significant factors shaping respondents’ emotional reactions and their relationship to political polarization and partisan dynamics.

The partisan affiliation of the detractor plays a dominant role in shaping the intensity and direction of emotional responses. When the detractor is associated with the “Other Party” (an ideological rival), respondents express significantly more negative emotions (β = −0.834, p < 0.001), reflecting intense out-group hostility. In contrast, detractors from “My Party” elicit overwhelmingly positive emotions (β = 9.120, p < 0.001), showcasing in-group favoritism. These findings indicate that respondents are highly influenced by partisan biases, with their emotional evaluations shaped more by the political affiliation of the detractor than by the behavior itself. The stark difference in emotional responses underscores the role of partisanship in Türkiye’s polarized political environment, where political opponents are viewed with suspicion and hostility. At the same time, in-group members are treated with leniency and support.

Issue salience also plays a significant role in shaping respondents’ emotional reactions. Compared to the baseline topic of global warming, identity-related issues, such as Syrians (β = −0.957, p < 0.01) and bilingual practices (β = −1.444, p < 0.001), elicit significantly more negative emotional responses. These findings suggest that topics tied to ethnic and cultural politics provoke stronger negative emotions, likely due to their centrality in Türkiye’s political polarization. Interestingly, the headscarf as a debated issue does not significantly influence emotional responses, possibly reflecting its normalization in public discourse compared to the most contentious matters of migration and bilingualism. This variation highlights how the content of political discussions shapes emotional reactions, with identity-related topics particularly polarizing.

Polarization exhibits a marginally significant negative effect on emotional responses (β = −0.309, p < 0.1), indicating that higher levels of polarization are associated with more negative emotions. Furthermore, the interaction between polarization and “Other Party” affiliation (β = −0.571, p < 0.05) suggests that polarization intensifies negative emotional responses toward ideological rivals. However, the interaction between polarization and “My Party” affiliation (β = 0.843) is not significant, indicating that in-group favoritism remains stable regardless of polarization levels. These findings emphasize how polarization exacerbates hostility toward out-groups without significantly altering in-group dynamics. The results underscore the affective nature of political polarization, with respondents’ emotional responses shaped by partisan dynamics and the salience of identity-related issues in a deeply divided political landscape (Figure 5).

The above table and figure show that our H4, stating “the intensity and direction of emotions will vary according to the assigned partisan identity of the detractor,” is supported by findings that present “Other Party” detractors eliciting the most intense negative emotions and “My Party” detractors eliciting positive emotions, reflecting in-group favoritism and out-group hostility. Moreover, the intensity of emotional responses varied significantly across issues, with identity-related topics like Syrians and bilingualism eliciting more extreme reactions compared to global warming. The partisan affiliation of the detractor further shaped these variations, confirming our hypotheses H4a.

This study situates affective polarization within the broader framework of othering, unpacking its implications for democratic cohesion and political discourse in Türkiye. By conceptualizing affective polarization as a combination of social distance, moral superiority, and political intolerance, we illuminate how it undermines the relational ethos of democracy and fuels intergroup hostility.

The findings affirm that affective polarization is a potent form of othering, fostering hierarchical and antagonistic relationships between political partisans. As the theoretical framework highlights, othering involves dehumanizing out-group members, reducing them to negative stereotypes and eroding opportunities for mutual understanding. This process is evident in the Turkish context, where political divides are amplified through moral disengagement and perceived threats to identity. The results underscore how these dynamics deepen the distance between citizens, echoing global trends of heightened animosity and distrust among political partisans.

Crucially, conceptualizing affective polarization as a type of othering provides a framework for measurement and sheds light on why this polarization endangers democratic principles. By understanding the process of othering, we can better analyze how political partisanship fosters negative thoughts, emotions, and behaviors toward opposing party supporters, ultimately challenging the ethical foundation of democracy.

Our analysis highlights the salience of identity-driven issues, such as the presence of Syrians and language rights, in intensifying affective polarization. These findings are consistent with prior research, which shows that identity-based topics related to existing cleavages provoke stronger emotional reactions than broader, non-partisan issues like climate change. The heightened emotional intensity observed in these contexts reflects the role of nationalist rhetoric and media amplification in shaping public attitudes. These findings emphasize the importance of addressing identity politics and its role in perpetuating social and moral hierarchies within polarized societies.

By framing affective polarization as a type of othering, this study contributes to the efforts to reduce partisan animosity by emphasizing the need to address the underlying processes that perpetuate hostility toward opposing party supporters. Interventions informed by this conceptualization can target polarization’s cognitive, emotional, and structural dimensions, offering a holistic approach to fostering mutual understanding and reducing intergroup animosity.

The study contributes to understanding how affective polarization threatens the foundational principles of democracy. By fostering moral superiority and intolerance, affective polarization challenges the relational foundation of democratic engagement—philia—as articulated in Aristotelian philosophy. Philia, understood as mutual goodwill and respect, is essential for fostering cooperative governance and sustaining social cohesion. However, the dominance of animosity and moral disengagement in polarized environments undermines these relational dynamics, replacing them with antagonism and exclusion.

Our findings align with previous studies suggesting that partisanship increasingly functions as a social identity, shaping emotional and behavioral responses to political opponents. This identity-driven polarization reduces the likelihood of recognizing shared goals, undermining the trust and empathy necessary for constructive dialogue and collective action.

Philia offers a compelling counterbalance to the divisive tendencies of affective polarization. As a relational virtue, philia fosters empathy, mutual understanding, and the pursuit of shared good. By integrating the principles of philia into deliberative democracy, we can envision a framework where emotional and relational dimensions complement rational discourse, creating inclusive spaces for collaboration.

Our findings underscore the need for interventions that promote cross-group interactions, challenge stereotypes, and encourage narratives of shared identity. These efforts can mitigate the exclusionary dynamics of othering and rebuild the relational foundations of democratic engagement. Additionally, fostering emotional intelligence and creating platforms for open dialogue can help counteract the polarizing effects of media-driven echo chambers.

While this study provides valuable insights into the dynamics of affective polarization, it has certain limitations. The scenario-based experimental design, while effective in isolating key variables, may not fully capture the complexities of real-world political interactions. Participants’ responses to hypothetical scenarios may differ from their behavior in actual polarized contexts, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future studies could incorporate longitudinal designs to examine polarization in naturalistic settings and track its evolution over time.

Another limitation is the focus on specific identity-driven issues, such as language rights and immigration, which are particularly salient in the Turkish context. While these topics offer rich insights into the role of identity politics, the findings may not extend to other less divisive or more globally relevant issues. Expanding the range of topics to include broader, non-identity-based challenges could enhance our understanding of how affective polarization manifests across different domains.

Additionally, this study does not address the role of digital media in shaping polarization dynamics. With their tendency to amplify echo chambers and polarizing narratives, social media platforms play a critical role in exacerbating affective polarization. Investigating how digital environments influence polarization’s cognitive and emotional aspects would provide a more comprehensive picture of its drivers and potential mitigators.

Finally, while the study emphasizes the importance of philia as a relational virtue, it does not empirically evaluate interventions to foster empathy and dialogue across divisions. Future research could explore how practical applications of philia—such as cross-group dialogues, trust-building initiatives, and emotional intelligence training—can reduce partisan animosity and rebuild democratic trust.

In conclusion, this study situates affective polarization within the broader theoretical lens of othering, demonstrating its multidimensional impact on democracy and social cohesion. By emphasizing the relational values of philia and the role of targeted interventions, we propose a path forward for addressing polarization, fostering empathy, and strengthening democratic practices in deeply divided societies. By integrating Marcus’s (2023) critique of emotion theories with our empirical findings on affective polarization in Türkiye, this study advances a more comprehensive understanding of the role of emotions in democratic life. We demonstrate that emotions are not merely byproducts of political engagement but active drivers of polarization and intolerance. Furthermore, our argument for philia as an emotion-regulating mechanism aligns with Marcus’s call for frameworks that integrate emotion regulation into democratic resilience. This synthesis of theory and empirical evidence highlights the urgent need for policies that address the emotional underpinnings of polarization, moving beyond rationalist models toward a more relational and affective approach to democratic cohesion.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Istanbul Bilgi University Ethical Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their oral informed consent to participate in this study.

EE: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PU-S: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Funding for the data and the project is obtained from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) under the title of Strategies and Tools for Mitigating Polarization in Türkiye Project (TurkuazLab) www.turkuazlab.org.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.