94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 11 April 2025

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 7 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2025.1545574

This article is part of the Research TopicRelations and Policymaking across EU Actors, National Governments, Parliaments and PartiesView all 3 articles

Introduction: This study investigates the impact of the 2024 European Union (EU) elections on France, focusing on the interplay between EU institutions, national governments, parliaments, and political parties within the context of Eurocentrism. It examines how EU elections influence national policymaking and political competition in France, particularly in light of the rise of populist parties within the EU Parliament.

Methods: The research employs a multi-level qualitative and comparative approach, analyzing recent EU electoral outcomes and their consequences for French political behavior. Qualitative methods, including case studies and discourse analysis, are used to assess the dynamics between French political actors and EU institutions, as well as the shaping of domestic political agendas and Eurocentric narratives.

Results: The findings reveal that the 2024 EU elections significantly influenced French political dynamics, particularly through the growing presence of populist parties in the EU Parliament. These elections shaped national policymaking and political competition, reinforcing the Reif and Schmitt 1980’s concept of EU elections as “second-order elections”. The study highlights the dual role of EU elections in reflecting national political trends while driving supranational policy agendas. The results underscore the evolving relationship between national and supranational governance, emphasizing the challenges posed by populism and Euroscepticism to European integration.

Discussion: The study contributes to the understanding of inter-institutional relations and their impact on policymaking, offering insights for scholars and policymakers concerned with the future of the EU and its implications for member states like France. This research provides valuable perspectives on the 2024 EU elections and their consequences for France, highlighting the complexities of European integration in an era of rising populism. It calls for further exploration of the long-term effects of these dynamics on EU governance.

In his speech at the Sorbonne on April 25th, Emmanuel Macron reminded his audience that the EU is “mortal” (Macron, 2024). This indicates that the EU faces numerous internal and external challenges (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic, the energy crisis, the war in Ukraine, and counterproductive cooperation hindered by Eurosceptic movements). In this context, European elections mark a crucial step in ensuring a framework conducive to a safe, democratic, and prosperous EU amidst a rapidly changing geopolitical environment. Three key issues were at the heart of European concerns, both at the institutional and member state levels:

• The ongoing triple transformation – digital, energy, and climate – calls for decisive action without further delay. The Green Deal for Europe, adopted in 2019, highlights this urgency.

• The internal functioning of EU institutions is essential for their ability to act and uphold fundamental rules, procedures, and shared values in the context of EU enlargement.

• Uncertainties surrounding the future relations between the EU and China, the United States, and Russia underscore the need to make impactful decisions.

• Finally, defining the major lines of a European economic policy to defend the EU’s competitiveness, as illustrated by the recent report from Enrico Letta (soon to be complemented by a report from Mario Draghi).

However, these concerns do not appear to resonate with European citizens, and even less so with French voters, who tend to view European elections primarily as second-order national elections.

European Parliament elections impact supranational institutions, but their outcomes are often perceived and analyzed through the lens of national politics, influencing domestic political landscapes. This counterfactual framing, where European elections are treated as though they were national parliamentary elections, forms the core focus of this analysis. We aim to show the intersection between European elections and French national politics, while questioning the Europeanization of European elections and France’s Eurocentrism. Thus, in this research, we consider the European elections as a starting point for the analysis, where the results in favor of the far-right are interpreted at the national level as national results rather than European ones. This makes the European elections primarily national elections. The research question is: What explains the dual dynamic of European elections being perceived as national contests while simultaneously shaping the increasing role of far-right parties in the European Parliament?

The research is based on a qualitative analysis of EU elections statistics and results for France and on a particular study of the Rassemblement National (RN) results.

The results of the European elections in France highlighted the victory of the far-right through the success of the Rassemblement National (RN). This study first demonstrates the impact of the European elections on national politics, which corresponds to the nationalization of European elections. This conclusion was drawn based on the perceptions of the French, the election results, and the domestic policy decisions that followed these elections. Thus, French participation in the European elections was not driven by a European choice but rather by their euroscepticism.

The victory can be attributed to a strategic shift by the RN, which involves integrating Europe into its discourse. This strategy, which consists of criticizing Europe from within its institutions, has two key characteristics: euroscepticism—where the far-right’s rhetoric remains anti-European—and Europeanization, meaning participating in European decision-making bodies to reshape the supranational governance system to serve the party’s interests.

It was therefore essential to analyze the impact of the far-right’s growth within the European Parliament, whose function as a democratic platform is undoubtedly reinforced but which simultaneously weakens institutional balance at the supranational level (de Búrca, 2018).

Since the EU’s founding, France has played a crucial role, with its political elites influencing the integration process (Dinan, 2014). According to academics like Rosamond (2000) and Milward (1992), France’s involvement in the EU demonstrates a strategic balance between integration and sovereignty. The literature emphasizes how French policy is frequently motivated by a Eurocentric worldview that aims to uphold national interests while projecting European leadership on a global scale (Smith, 2008). In the early decades, France and Germany co-led the EU, but in the 1990s, economic disparities and EU expansions diminished its power. Nonetheless, outside developments such as Brexit and Macron’s assertive European agenda indicate that French involvement within the EU is on the rise again (Ducoux and Fejérdy, 2021).

The EU and France’s relationship has changed dramatically since its founding membership in the European Communities. While the Europeanization of public policy and legislation intensified, French political life and domestic institutions remained relatively unchanged until the 2010s (Rozenberg, 2020). This dynamic shifted notably with the 2017 election of President Emmanuel Macron, whose pro-European stance revitalized France’s influence in EU policymaking (Bora and Schramm, 2023).

Eurocentrism, characterized by the prioritization of European identity and interests, plays a central role in French EU policy. Scholars such as Habermas (2012) argue that France’s Eurocentric approach seeks to position the EU as a counterbalance to American hegemony. This approach influences France’s stance on key EU issues, including monetary policy, defense, and environmental regulations.

However, the literature highlights tensions within this Eurocentric framework. Authors like Schmidt (2006) note that France’s ambition to lead the EU often clashes with the realities of inter-institutional dynamics and the need for consensus among member states. During President Macron’s tenure (2017–2022), France regained influence in EU politics, leveraging domestic policy priorities to shape European fiscal, competition, and defense industrial policies (Bora and Schramm, 2023). Macron’s leadership, coupled with a balanced Franco-German relationship and external EU shocks, underscores France’s capacity to navigate and influence the inter-institutional dynamics of the EU.

The impact of EU elections on France is characterized by a complex interplay between national and supranational governance (Dehousse, 2016; Lequesne and Behal, 2019). This interplay is rooted in France’s historical engagement with the EU and its paradoxical stance on supranational integration—supportive in economic areas yet cautious in foreign and defense policies (Lequesne and Behal, 2019; Ducoux and Fejérdy, 2021).

Our article first relies on the theory of supranational governance (Jachtenfuchs, 2001; Moravcsik, 1998), which refers to the study of decision-making and regulatory dynamics within structures or institutions that transcend national borders, such as the European Union (EU). Sweet and Sandholtz (1997) highlight the EU’s transition toward a governance paradigm that goes beyond state sovereignty. This theory explores how supranational entities (the European Parliament, the European Commission) make decisions that go beyond nation-states and influence their functioning.

The creation of the European Parliament in 1974 and the first direct elections aimed to foster a common identity among Europeans, legitimize policies through democratic processes, and provide a public space for Europeans to exert more direct control over their collective future. European elections are an important democratic issue which legitimizes the EU’s role at supranational and intergovernmental level. The Rapport du groupe ad hoc pour l’examen du problème de l’accroissement des compétences du Parlement européen –Rapport Vedel (1972) (Report of the Ad Hoc Group for the Examination of the Problem of Expanding the Powers of the European Parliament). The Vedel report (1972) stated that: “to carry out the tasks which await the Community in the definitive period, it needs a Community democratic legitimacy in addition to that transmitted by the responsible governments” (1972, p. 17). The direct election of such an assembly was seen as favoring political integration at the supranational level and democratization (Costa, 2016). Some debates (Nugent, 2017; Hix and Høyland, 2011) argue that direct elections of the European Parliament might further undermine the sovereignty of member states and fail to deliver on the promises made in favor of that process. With an emphasis on the function of the European Parliament, Marsh and Mikhaylov (2010) elaborate on the relationship between European elections and EU governance. They contend that by supporting or undermining supranational organizations, EP elections have an impact on governance systems. With the Treaty of Lisbon giving it more power, the European Parliament has been crucial in determining legislative outcomes and establishing its control over EU governance (Marsh and Mikhaylov, 2010). The supranational governance model’s increasing sway over European politics is reflected in this development.

In their book on European elections and domestic politics, Farrell and Schmitt-Beck (2005) highlight the Parliament’s involvement in the integration process, arguing that elections to the EP help create a more unified and politically integrated EU government. Schmitt-Beck and Farrell contend that European elections are not only provide a platform for citizens to express views on national politics but also reinforce the legitimacy of the supranational institutions in their ability to govern effectively. Inter-institutional dynamics, particularly between the European Parliament, the European Commission, and the Council of the EU, significantly shape the impact of EU elections on France. Studies by Moravcsik (1998) argue that France’s influence within these institutions depends on its ability to form strategic alliances. For instance, French MEPs often play key roles in shaping legislative agendas, particularly in areas aligned with French national interests. Studies by Hix and Lord (1997) reveal that French parties, particularly the Parti Socialiste (PS) and Les Républicains (LR), have historically influenced the balance of power within the European Parliament (EP). However, recent shifts towards far-right and far-left parties reflect broader societal concerns about globalization and identity (Börzel and Risse, 2018).

Thus, European elections highlight the concept of Europeanization (Cowles et al., 2001; Featherstone and Radaelli, 2003), which examines how European dynamics influence national policies. Europeanization refers to the mutual influence between the European Union (EU) and its member states, the interactions within and between member states driven by the EU, and the EU’s impact on applicant states. Ladrech (2002) coined and defined the term “Europeanization” to analyze the effect of the European Community on its member states. The theory applies to political systems and parties starting from the 2000s, especially with an analysis of European construction disrupting national political cleavages (Mair, 2000; Belot et al., 2013; Déloye and Hottinger, 2005; Roger, 2008). By mobilizing national actors, European elections are key elements of Europeanization (Baisnée and Pasquier, 2007; Conti, 2014).

The increasing prominence of EU concerns in national election campaigns and public debate is one example of how France has adapted to EU administration, reflecting both continuity and recent politicization (Rozenberg, 2020).

In French EU policy, Europeanization frequently results in eurocentrism, when domestic policy frameworks are dominated by European standards and priorities, potentially marginalizing local and national particularities in favor of more general EU goals.

The concept of Europeanization has not only been studied from the perspective of national policies but also from the viewpoint of political parties. Research by Reungoat (2014) provides significant insights into how parties, particularly the far-right Rassemblement National (RN), have been shaped by the process of European integration. Reungoat (2014) explores the way in which Europeanization affects party dynamics, particularly how the European Union (EU) and its institutions influence the strategies, positions, and identities of political parties. His analysis focuses on how parties, especially those on the fringes such as the Rassemblement National (RN), adapt to and interact with EU governance structures.

European elections, in particular, can further politicize European issues by forcing parties and citizens to reflect on their country’s role within the EU. This politicization can exacerbate national tensions and reshape traditional partisan divides around pro-European and anti-European axes. The public’s perception of national governance and European integration is gaged by EU elections, using Eurobarometers (2024). The growing politicization of EU issues in French domestic politics since the 1990s has mirrored rising Euroskepticism. Literature highlights the rise of Euroscepticism in France, as evidenced by the electoral success of parties like the Rassemblement National (RN) (Ivaldi, 2018). According to scholars like Hooghe and Marks (2009), French voters frequently utilize EU elections as a means of voicing their discontent with domestic policy, highlighting the interaction between national and European concerns. According to empirical research, EU issues were not very important in previous French elections, such 2002, when domestic politics overshadowed European themes (Drake, 2003). Recent elections, however, demonstrate a gradual integration of EU topics into the political agenda, reflecting shifts in public and party priorities (Ysmal, 2008). The European issue is taken into account by voters in their national voting behavior, especially in a context where party divisions on European issues have become more visible (Hutter and Grande, 2014).

In the early 2000s, Cees van der Eijk and Mark Franklin described the European issue as a “sleeping giant” that, if awakened, could profoundly disrupt national political orders (Franklin et al., 2004). Despite these challenges, France’s narrative of EU membership—as a founding and leading member state—remains central to its political identity (Rozenberg, 2020).

Regarding the electoral process, we explore three theoretical foundations: the second-order voting theory (Reif and Schmitt, 1980), electoral spillover theory (Rohrschneider, 1993, 1994), and democratic representation and legitimacy theory, rooted in the Enlightenment movement (Habermas, 2012). European elections are often viewed as second-order elections, where voters express discontent with national policies.

However, their impact on national politics can be significant if the results strengthen or weaken key parties, as seen in France with the rise of the Rassemblement National (RN). This paradigm is further developed by van Egmond (2005), who contends that European elections function as counterfactual national elections and that voters view them as chances to assess national governments rather than concerns affecting the entire EU, highlighting how the behavior of voters in EP elections mirrors national political dynamics, leading to a politicization of EU-level contests that reflects internal domestic politics. Additionally, European elections can have electoral spillover effects on national elections. The successes or failures of a party in European elections often influence its credibility and electoral strategy at the national level, altering political power dynamics. Finally, European elections challenge how citizens perceive political representation at both the supranational and national levels. The results can legitimize European integration or reinforce contestation, as shown by the negative sentiments toward the EU expressed by some French voters in 2024. Using Lipset and Rokkan’s (1967) theory of cleavages, we will show how European elections highlight new cleavages, such as those between globalists/pro-Europeans and populists/eurosceptics. This cleavage often transcends traditional ideological alignments, redefining political coalitions and creating fractures within parties.

By combining these theories, we can explain how European elections serve not only as a barometer for public opinion on the EU but also as a catalyst for national political transformations, exacerbating existing divisions and reshaping partisan alliances (Roger, 2007, 2009).

The methodology first involves analyzing quantitative data related to the European elections – particularly in France, that serves as a case study for exploring how national dynamics influence voter behavior in the context of European elections.

The data consist of statistics collected prior to the electoral deadline and the election results themselves.

The data can be analyzed using qualitative methodology to understand the political dynamics and voter behavior in the country. To better understand the dynamics of electoral decision-making in the context of the June 2024 European elections, Ipsos Sopra Steria, Cevipof, and Le Monde established a comprehensive survey framework known as the Enquête Électorale Européennes. This panel study involved more than 10,000 participants who were surveyed multiple times over the 12 months preceding the election on June 9, 2024.

The data was collected in five waves:

• Wave 1 – June 2023: Initial survey capturing baseline attitudes towards European elections and political preferences.

• Wave 2 – November 2023: Focused on evolving attitudes and the impact of emerging campaign themes on voter intention.

• Wave 3 – March 2024: Monitored changes in voter preferences following major political and economic developments at the national and EU levels.

• Wave 4 – April 2024: Provided insights into voter alignment and campaign effectiveness during the final weeks leading up to the elections.

• Wave 5 – June 2024: Conducted just before the election to measure finalized voter decisions and motivations.

This longitudinal approach allows for the analysis of changes in voter attitudes and behaviors over time, providing a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing electoral outcomes. The survey also examines how national and European issues intersect in shaping voter choices.

To analyze the perceptions of French citizens, we utilized data from the Eurobarometers published by the European Commission. Specifically, we referenced:

• European Commission (2023a). Eurobaromètre Standard 100. L’opinion publique dans l’Union européenne: Rapport national – France.

• European Commission (2023b). Standard Eurobarometer 100 - Autumn 2023.

Regular Eurobarometer surveys are used to gage public opinion in EU member states on a range of subjects, such as views toward national and European concerns, European integration, and faith in EU institutions. These surveys gave us important information about French residents’ perceptions of the EU, its policies, and their place in the European project, which we used in our study.

We could analyze trends and patterns in French public opinion, pinpoint important concerns affecting voting behavior, and place these findings in the larger European perspective by combining this data. Understanding how national priorities and European integration initiatives align—or do not—requires an awareness of these attitudes.

Lastly, in reference to the outcomes, we obtained the information from the official website of the European Parliament. This website offers thorough and trustworthy facts on European Parliament election outcomes for all member states, including voter turnout, party performance, and seat distribution.

In order to provide a thorough and multidimensional analysis of voter behavior and electoral dynamics, the study uses a triangulated methodology by combining data from several sources, such as official European Parliament election results, Eurobarometer reports, and Ipsos Sopra Steria surveys. Voter sentiments toward European integration, regional differences in political preferences, and the influence of national vs. EU-level concerns on voting decisions are among the themes identified by the research.

The survey waves also reveal themes including changing campaign narratives, economic concerns, and perceptions about EU institutions.

To identify recurrent trends in attitudes, responses from the Eurobarometer or Ipsos Sopra Steria panel poll can be categorized into categories such as nationalism, immigration concerns, trust in EU institutions, or environmental objectives.

Party performance, national issues, and EU policy are examples of broader categories.

Subcategories may concentrate on issues related to geopolitical stability, cultural identity, or the economy.

The analysis takes into account contemporary political-economic events in France and Europe, such as economic crises or discussions regarding EU sovereignty, as well as the historical background of French sentiments toward the EU.

The data was systematically accessed and analyzed to identify patterns and shifts in voter preferences across different election cycles. The methodology involved comparing historical and recent election data to assess the evolution of party performance, the impact of European issues on voter choices, and the role of national dynamics in shaping these results. With 30 seats won, the Patriots for Europe (PfE) group clearly dominates the French election results, demonstrating the Rassemblement National’s (RN) victory as the most popular party. The Left (GUE/NGL) won nine seats, demonstrating the enduring significance of leftist agendas, while the Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and Renew Europe came in second and third, respectively, with 13 seats. With six and five seats, respectively, the European People’s Party (EPP) and Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) continued to have consistent but smaller representations.

The information provides a longitudinal account of how campaign narratives, political events, and public opinion regarding EU policy affected voter preferences over time. Voter behavior shows patterns, such as:

• Consistent support for nationalist parties in specific regions.

• Shifts in leftist and environmentalist voter bases over time.

• Stable but minority representation for groups like the Greens/EFA.

Voter alignment with parties such as Rassemblement National is explained in detail by the analysis.

By examining the underlying narratives and voter motivations, qualitative research enhances these numerical findings. To do this, it is necessary to read the rise of populist parties and mainly the RN as an indication of the rise of nationalist and Euroskeptic attitudes. This change was probably influenced by a number of factors, including national sovereignty concerns, immigration policy discussions, and economic instability.

However, the tenacity of centrist forces like S&D and Renew Europe indicates that progressive social programs and EU integration continue to be top priorities for many voters. The Greens’ and EFA’s steady presence shows that environmental issues continue to be a major concern for certain voters, mirroring broader European tendencies toward sustainability and climate action.

Analyzing political speeches and campaign messaging using discourse analysis provides important insights into how parties present their agendas and interact with voters. This method focuses on the words, ideas, and stories used to create political identities, influence public opinion, and rally support. The Rassemblement National (RN) and Renaissance campaigns, as well as Emmanuel Macron’s speeches, demonstrate divergent tactics and ideological stances in the context of the European elections.

Macron frequently presents Europe as a solution to global issues like economic competition, security, and climate change in his speeches, notably his well-known Sorbonne Speech in 2017 and his campaign rhetoric for 2024. Macron promotes ideas like “strategic autonomy” and “European solidarity,” presenting the EU as a force for unity and sovereignty. His rhetoric frequently highlights hope and a forward-looking outlook, which appeals to voters who support Europe. Macron reiterated this theme during his Renaissance campaign in the 2024 European elections, portraying the party as the champion of a powerful and cohesive EU. Renaissance positioned itself as an alternative to Euroskeptic populism and reaffirmed its commitment to EU collaboration with slogans like “Europe that protects.”

Power and ideology are embedded in language (Barthes, 1967), and political campaigns are prime spaces where discourse is used to shape public opinion, legitimize power, and influence behavior (Fairclough, 1995). Campaigns construct narratives about the EU (e.g., integration vs. sovereignty) that reflect underlying ideologies (e.g., pro-Europeanism vs. euroscepticism).

Critical discourse analysis reveals that Macron’s language has a strong foundation in symbolic leadership. His speeches frequently highlight the moral and historical necessity of European unification in an effort to inspire younger, more educated, urban voters who believe that the EU is crucial to France’s standing in the world. Pro-European groups are successfully rallied by this framing, especially those who believe that the EU upholds principles like democracy and environmental sustainability.

In stark contrast, the RN, under Marine Le Pen’s leadership, employs a discourse that critiques the EU as an overreaching and elitist institution undermining French sovereignty. “Taking back control” and defending national identity against alleged threats from immigration and globalization are common themes in campaign messaging. The RN presents the European elections as a chance to oppose the federalist goals of the EU and advocate for a Europe of states as opposed to a supranational organization.

Discourse analysis demonstrates how the RN’s language plays on public anxieties and annoyances by emphasizing emotive appeals like “anger” and “betrayal” connected to EU policy. Targeted messaging is used by the party to appeal to working-class and rural people who feel excluded by Brussels’ laws and globalization. Campaign materials frequently draw attention to specific complaints, like the economic effects of EU trade policies or the perceived loss of border control. This language not only mobilizes the RN’s base but also seeks to expand its appeal among disenfranchised voters.

These framing strategies highlight how discourse shapes voter engagement by appealing to different values, emotions, and perceptions, according to the narrative theory (Fischer, 1988). For pro-European voters, Renaissance’s campaign embodies an optimistic vision of cooperation and progress. For Euroskeptic voters, the RN’s rhetoric offers a voice for sovereignty and national pride. RN constructs a narrative of “France for the French” and positions the EU as a threat to sovereignty, while Macron’s party emphasizes “reforming the EU from within.” This divergence illustrates the deep polarization in European attitudes and the critical role of political language in electoral outcomes. Furthermore to emotions appeals, we can add temporal framing that confirm the divergence. Campaigns use the past (e.g., loss of sovereignty), present (e.g., economic challenges), and future (e.g., reclaiming power from the EU) to shape voter perceptions. The attitudes of voters can also be analyzed from the Social Identity theory (Tajfel, 2010) that considers that voters’ political preferences are shaped by their identification with specific social groups and their perceived in-group vs. out-group dynamics.

A key foundation for comprehending the dynamics of the French elections for the European Parliament in 2024 is the interaction of rhetoric, voter behavior, and the alignment of national and European politics. Our method offers insights into the interactions between political platforms, campaign narratives, and voter attitudes in this dynamic environment by combining discourse analysis, panel survey data, and electoral outcomes. The results of the 2024 European elections, which showed a divided electorate and strong disagreements on European matters, have made political instability in France worse. In this fractured context, the RN’s Euroskeptic agenda and Renaissance’s pro-European platform represent opposite poles, making compromise difficult. In addition to reflecting larger social problems, this division has exacerbated the political atmosphere, making it more challenging to reach an agreement on France’s place in the EU.

The European elections were held on June 9, 2024. The turnout in France was 52.49%, slightly higher than the European average of 50.74% (European Parliament, 2024). France secured 81 seats.

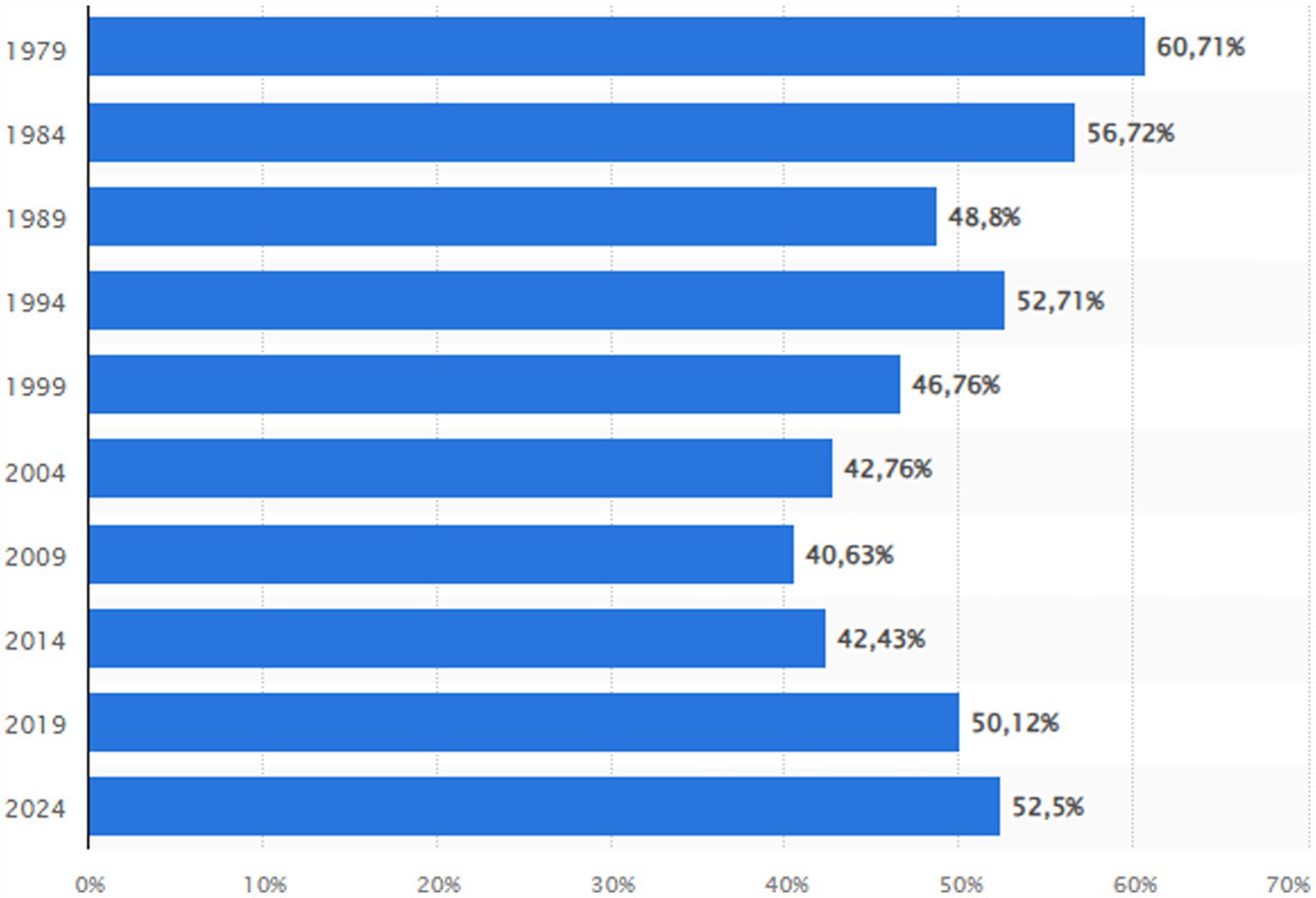

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the Proportion of French citizens participating in European Parliament elections between 1979 and 2024. For the French, European elections have long been considered second-order national elections. In 1979, 62% of European citizens voted (Statista, 2024). Since then, participation has steadily declined, despite a rebound in 2019. European elections in France have become increasingly prominent in political discourse and public opinion since 2002. For French voters, “the salience of Europe as a distinct and separate issue was… low… in 2002” (Drake, 2003). In 2007, electoral topics on the agenda were largely focused on domestic politics rather than EU politics. Europe was deeply integrated into the national sense of identity and mission for the French (Ysmal, 2008). Foreign and security policy were part of the party manifestos in 2002 (UMP and PS), considered a significant element in the construction of the European Union.

Figure 1. Proportion of French citizens participating in European Parliament elections between 1979 and 2024. This statistic shows the participation in European Parliament elections in France between 1979 and 2024. It was conducted by Statista in June 2024. Retrieved from: https://fr.statista.com/statistiques/573562/parlement-europeen-participation-aux-elections-europeennes-1979/.

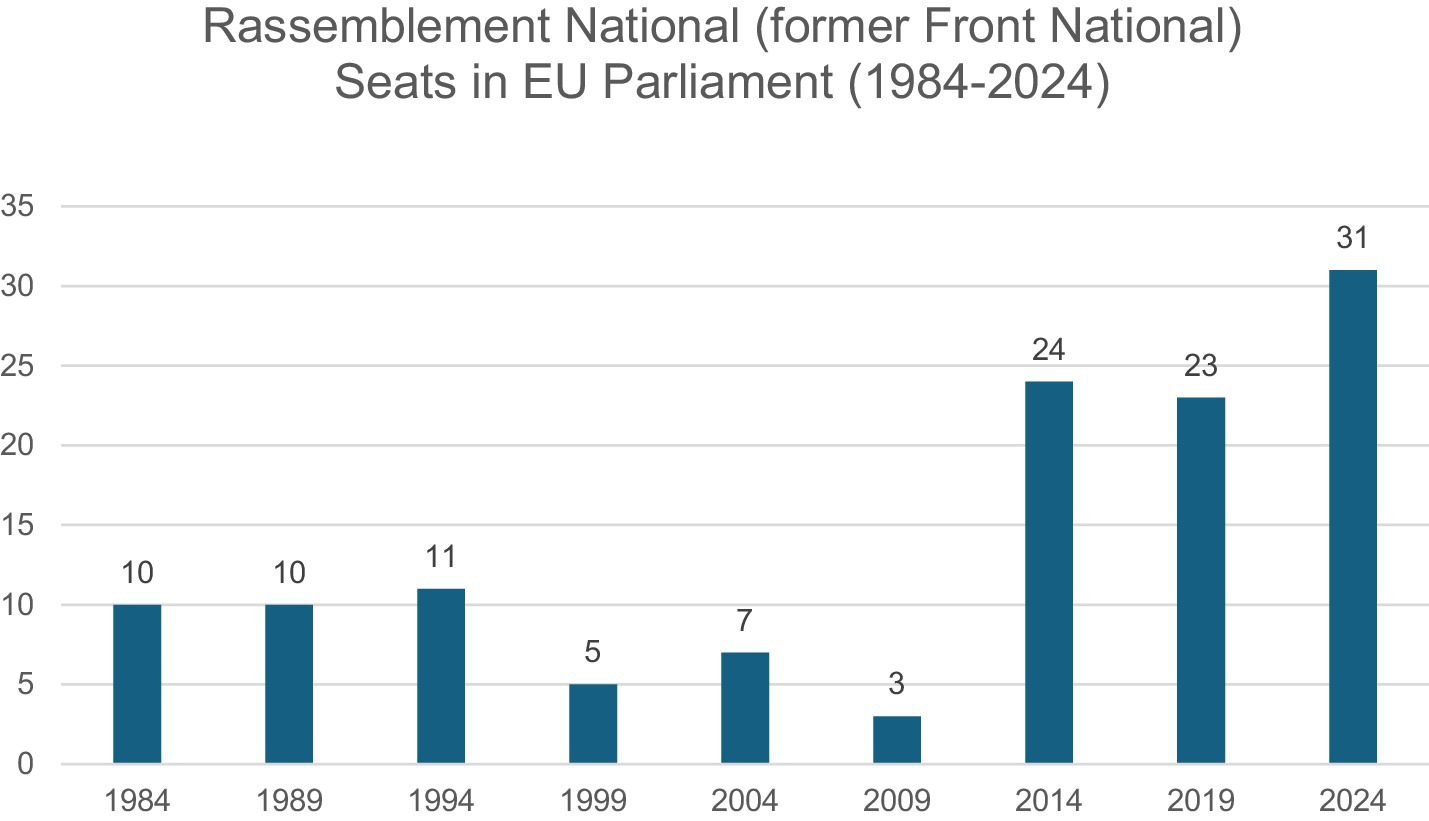

This is the second-order nature of EP elections that is reflected in lower voter turnout and different voting patterns compared to national elections (Reif and Schmitt, 1980; Hrbek, 2019). However, since 2014, there has been a resurgence in participation, albeit benefiting far-right parties that have gradually gained seats in the European Parliament: from 10 in 1984 to 31 seats in 2024, with a great increase in 2014 (+21 seats), as it is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Rassemblement national (former front national) seats in EU Parliament (1984–2024). Data retrieved from https://www.la-croix.com/france/resultats-election-europeennes-2019-2014-extreme-droite-rassemblement-national-vote-20240529.

Jordan Bardella, the head of the far-right National Rally (RN), and Marine Le Pen, the leader of the parliamentary group, both won significant victories in the French EP elections (European Parliament, 2024). They received roughly 31.4% of the vote. Indeed, with the splinter party Reconquête’s 5.5% vote share, the extreme right now holds almost 40% of the French vote, the biggest share to date. In contrast, even though French President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance party centered his platform on the idea of an existential conflict between pro- and anti-European forces, symbolized by the far right, the party only received 14.6% of the vote.

The main question then is if the far right is the premier force in France in the immediate after elections and now. Does the dissolving of the French Parliament decision a response to this victory or a confirmation of it?

The rise of the far right and its victory, as reflected in the 2024 election results, serve as a political catalyst, disrupting the balance of power both nationally and at the European level. This outcome challenges France’s eurocentrism as well as the process of Europeanization (Ladrech, 2002, 2010, 2012). Consequently, we seek to understand how the nationalization of European elections in France functions both as a driver of Europeanization and as a threat to this process. What does the Euroscepticism of radical parties (Taggart, 1998; Sitter, 2001; Taggart and Szczerbiak, 2003) mean in 2024?

Since 1984, the French Far-right has consistently secured seats in European elections (Birenbaum, 1992; Dezé, 2007, 2012) (Figure 2). The European Parliament serves as both a source of political legitimacy and financial resources for the National Rally (RN), reaching its peak with the case of the misappropriation of European funds allocated to parliamentary assistants in September 2024—a case tried in France rather than by the European Commission.

However, in 2019, upon leaving the European Parliament, the former president and founder of the RN, Jean-Marie Le Pen, harshly criticized the EU and its institutions. He declared, “Le souvenir que j’emporte de cette maison, c’est. un petit peu le sentiment d’inutilité” (“The memory I take from this house is somewhat the feeling of futility”), comparing the European Parliament to a “moulin à vent” (“windmill”). Continuing his critique of its futility, he said: “Ici, nous sommes dans un moulin à vent. Et comme le meunier d’Alphonse Daudet, nous ne charrions dans notre brouette que des sacs de sable au lieu des sacs de blé, pour faire illusion” (“Here, we are in a windmill. And like the miller of Alphonse Daudet, we carry in our wheelbarrow only bags of sand instead of bags of wheat, to create an illusion”) (Le Pen, 2019). For him, the EU undermines national sovereignty, particularly in terms of immigration control: “l’UE est. un carcan qui paralyze l’activité politique (…) contre un danger: la déferlante migratoire qui est. consécutive à l’explosion démographique du monde” (“The EU is a straitjacket that paralyzes political activity (…) against a danger: the migratory wave resulting from the world’s demographic explosion”) (Le Pen, 2019).

What, then, is the RN’s objective in campaigning for European elections and striving to win as many seats as possible? Is access to the European Parliament a national or European strategy? Does their penetration of European institutions serve as a means to legitimize the far-right party among French citizens? Or is it part of a broader European strategy aimed at dismantling the institutions from within, in line with radical Euroscepticism?

The RN has portrayed itself as the only political force capable of defending the uniqueness of the French social model against what it also calls “les institutions élitistes de Bruxelles” (“elitist institutions in Brussels”) (Varma, 2024). By doing so, the RN seeks to broaden its electoral base and solidify the leader’s position by tightening its control over the party apparatus (Reungoat, 2014). The 2003 reform in France, allows the RN to secure representation beyond the local and regional levels. In fact, French parties must reach a 5% threshold to be represented in the European Parliament. Within a closed national competition, the European election represents, among other factors, an essential vector for the professionalization of RN cadres (Kestel, 2008).

One of the main themes of Emmanuel Macron’s political campaigns has been his approach to portray elections as conflicts between factions that support and oppose Europe. In his Sorbonne speech, Macron (2017) laid out his vision for a stronger, more united Europe, emphasizing the need for deeper integration in areas such as defense, digital governance, and economic reforms. He called for a more cohesive European Union that addresses challenges like migration, security, and the digital economy, positioning France as a key driver of EU progress (Macron, 2017). Macron has effectively positioned himself as a champion of European integration, especially in the 2019 European Parliament (EP) elections and the 2022 presidential contest, by highlighting his dedication to the EU and drawing a comparison with his opponents’ euroskepticism.

Macron described the 2019 European Parliament elections as a struggle for the future of Europe, and called for “a genuine recomposition and a new stage in the European adventure” (Macron, 2019). La République En Marche! (LREM), his party, advocated policies focused on economic modernization, climate action, and closer EU cooperation. Pro-European voters who were worried about the emergence of nationalist parties like Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, which eventually garnered the most votes, found solace in this story. Macron’s positioning strengthened his reputation as a unifying pro-European leader in spite of the tight outcome.

Macron stepped up this strategy throughout the 2022 presidential campaign, especially during his second-round contest against Marine Le Pen. Macron won over supporters who appreciated the EU’s role in tackling global issues like security and climate change by portraying Le Pen’s euroskeptic program as a danger to France’s place in Europe. Despite mounting domestic obstacles, he was able to win re-election because to this tactic, which helped him rally support from centrist and left-leaning voters. Emmanuel Macron’s strategy of framing political contests as battles between pro-European and anti-European forces has had broader effects on French politics. His approach successfully unified pro-European voters, particularly younger, educated, and urban populations who view the EU as essential for addressing global challenges such as security, climate change, and economic stability. By highlighting the risks posed by euroskeptic forces, Macron effectively marginalized these opponents, often exposing internal conflicts and forcing them to defend their positions, thereby weakening their credibility. Additionally, Macron’s resolute pro-European stance has reinforced France’s leadership role within the EU, enhancing his image as a global leader and bolstering France’s influence on the international stage (Macron, 2024). He confirms 2 months before the European elections the key principles of the 2024–2029 agenda, namely a sovereign, united and democratic Europe, security and the fight against nationalism that «dare no longer say they want to leave the euro and Europe» and who instead have “a ‘yes but” speech” (Macron, 2024).

We aim to demonstrate the interconnection between European elections and France’s national politics.

First, we analyze the presence of European themes and issues in the candidates’ speeches and programs during the electoral campaign, as well as their alignment with the priorities of the French people.

Second, we examine the political and institutional response of President Macron—namely, the dissolution of the National Assembly, which we consider to be the political catalyst allowing us to question whether a victory for the RN at the European level also translates into a victory at the national level.

Thus, are European elections a reflection of national elections?

The first concerns the nationalization of European elections, reflected in the shift of the debate to a context of contestation in domestic politics. Among the key issues influencing French voters’ choices in the European elections, purchasing power ranks first (47%), followed by immigration (38%), and the healthcare system (29%) (Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne, 2024). France’s position in Europe and the world comes in fifth place (20%).

For populist parties like LFI and RN, the priority given to purchasing power and healthcare is particularly prominent (Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne, 2024). The three primary issues influencing RN voters’ choices are, in ascending order: immigration (76%), purchasing power (55%), and security of property and people (32%). For LFI voters, the three main concerns are social inequality (48%), security of property and people (46%), and purchasing power (44%). These results highlight that for both populist parties, the decisive issues are rooted in domestic politics, confirming the national stakes of European elections for these parties.

In contrast, for voters of the pro-European presidential party Renaissance, the most important issue is France’s position in Europe and the world (44%). The other two major topics are the war in Ukraine (35%) and environmental protection (30%). This starkly contrasts the voting intentions between pro-European parties like Renaissance and populist, Eurosceptic parties like LFI and RN.

This divide is also evident in voters’ feelings toward the EU a month before the June 2024 elections. For example, voters expressed anger and fear about the EU (Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne, 2024). Among LFI voters, 50% felt anger, while Renaissance voters expressed pride and enthusiasm (Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne, 2024).

Feelings about the EU closely mirror those about the situation in France: concern, anger, bitterness, and fear dominate among LFI and RN voters, while hope, pride, and enthusiasm prevail among Renaissance voters (Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne, 2024).

The data reveals a close link between voters’ perceptions of national and European issues, illustrating an alignment of emotions and voting intentions. This phenomenon can be analyzed from several perspectives.

Firstly, there is the polarization of perceptions between pro-European and Eurosceptic parties. Voters of pro-European parties, such as Renaissance, express predominantly positive feelings toward the EU, including pride and enthusiasm. These emotions reflect their ideological alignment with the values and projects of European integration. Conversely, voters of populist and Eurosceptic parties, such as La France Insoumise (LFI) and the Rassemblement National (RN), exhibit negative emotions such as anger, bitterness, and fear toward the EU. These sentiments reveal a rejection or criticism of European policies perceived as being contrary to their national interests.

Moreover, there is a similarity in emotions regarding national and European issues. The feelings evoked by the EU (anger, fear, bitterness, or pride, enthusiasm, hope) directly mirror those experienced by voters concerning the national situation. For example, LFI and RN voters, often critical of national governance, project their frustrations onto the EU, which they view as an extension of national dysfunctions. Conversely, Renaissance voters, confident in the European project, display similar optimism for both national and European issues, underscoring a coherence in their political outlook.

These contrasts highlight how the EU acts as a mirror of national dynamics, amplifying existing ideological divides. Pro-European voters see the EU as an opportunity for collective progress, a space for solidarity, and a means of addressing crises. On the other hand, Eurosceptic voters view the EU as a source of constraints and threats to national sovereignty.

Consequently, the impact on voting intentions is evident. Pro-European parties such as Renaissance capitalize on the support of voters convinced of the benefits of European integration. These parties benefit from an alignment between their rhetoric and their voters’ emotions. Conversely, populist and Eurosceptic parties mobilize their base by amplifying criticisms of the EU, aligning their strategy with national resentments.

The EU thus becomes a central issue in explaining political divisions and electoral choices, illustrating how national dynamics influence opinions on European policies.

It is from this perspective that we turn our attention to campaign messages and slogans. The RN, for instance, confirms its decision to remain in the European Union, aiming to avoid voter demobilization by nationalizing the June election at all costs and targeting Emmanuel Macron. The poster1 reflects an alignment of national and European rhetoric: “La France revient. L’Europe revit” (“France is back. Europe is revived”). The parallelism is evident. However, the part “L’Europe revit” (“Europe is revived”) does not appear on the 2024 campaign poster2, which confirms the nationalist trend of the RN in continuity with its 2019 campaign, thereby reinforcing the nationalization of the election. The focus is instead on “La France revient” (“France is back”), demonstrating the RN’s desire to influence the national democratic landscape.

As for Renaissance’s campaign message, it reflects clear Europhilia, highlighting France’s place and image in Europe: “Le 9 juin, nous avons Besoin d’Europe” (“On June 9, we need Europe”) and “L’Europe, c’est. nous” (“Europe, it is us”), that we can read in the last published poster at the end of the campaign.3 In this poster the tonality is more aggressive and assertive. The campaign is perceived as a battle, a Manichean battle against the RN.

On the campaign poster of Macronist candidate Valérie Hayer, the phrase “majorité présidentielle” (“presidential majority”) is added, showing the direct link between a victory in the European elections and success at the national level.4 This further illustrates the national stakes of the European elections.

The visuals underscores Macron’s central role in positioning Renaissance as a staunchly pro-European force. The campaign emphasizes his leadership in advancing European integration and addressing cross-border challenges, aligning with the party’s strategic appeal to voters supportive of a strong and united European Union (BFMTV, 2024). The caption accompanying the photo, seems to confirm this perception: “our project,” a direct reference to the famous “because it is our project” shouted by Emmanuel Macron at the end of his rally at Porte de Versailles in Paris in 2016 (RTL, 2016).

What also favors this shift in the debate is the fact that national parties themselves are candidates in the European elections. Both Hayer and Bardella are French MPs before being candidates for EU elections, and the fact that they are both represented on posters with their party leader, confirms the alignment between national programs, national leadership and EU representations. In addition, no transnational lists exist (Sauger, 2015). By nature, a political competition organized within the national framework aimed at the designation of deputies who will sit in a supranational institution. The results of the European elections are proclaimed at the national level, but their legal effect pertains to European institutions (Maloingne, 2024). However, as Costa notes, “the supranational dimension of European elections remains limited” (2022).

The composition of the directly elected European Parliament does not precisely reflect the ‘real’ balance of political forces in the European Community. EU elections are more influenced by domestic political cleavages than by alternatives emerging from the EC. This is because European elections occur at different stages of the national political systems’ ‘electoral cycles.’ Such a relationship between a second-order arena and the chief arena of a political system is not unusual. A dozen national elections are held within the EU in 2024. In Belgium, federal and regional elections are held on the same day as the European elections, June 9. Presidential elections take place in 2024 in Finland, Slovakia, Lithuania, and Romania, while voters in Portugal, Austria, and Croatia are called to the polls for legislative elections.

This is also the case in France and Germany (Krpata et al., 2024). In both countries, European elections resemble a test to assess public opinion toward their national governments. In France, the European election and the resulting instability appear as an intermediate stage before the 2027 presidential elections, signaling a potential sanction for Emmanuel Macron and his party. In Germany, the regional elections of September 2024 confirmed the rise of the far right in Thuringia and Saxony, further destabilizing Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition. The AfD secured 30.63% of the vote, behind the CDU (31.91%) (Wahlrecht.de, 2024). Like Macron, Scholz positions himself in favor of EU reinforcement, particularly through security, defense, energy, and trade policies. In 2022, Olaf Scholz declared a “Zeitenwende” (“turning point”) (Scholz, 2022).

In France, if electoral competition is not structured around European issues, it tends to become increasingly influenced by them. First, the direct effects we have discussed concern the rise of anti-European movements. Indirect effects pertain to changes in the power dynamics, activities, and strategies of partisan actors (Mair, 2006, p. 154; Shemer-Kunz, 2013).

The high result achieved by the RN in the European elections becomes a means to break out of national isolation and serve as a bargaining tool for governmental alliances (Shemer-Kunz, 2013). Positioning itself as “the leading party of France,” the RN has exerted pressure on the President of the Republic and public opinion to be appointed at the head of the government.

President Macron’s decision to dissolve the National Assembly occurs within this context of social pressure, coming from both RN and LFI voters. This is a similar strategy to the one used in 2014, when Marine Le Pen promised to ask François Hollande to dissolve the National Assembly (Le Pen, 2014). Bardella (2024), the head of the far-right party Rassemblement National, adopts the same stance, calling to “sanction Macron’s Europe” and stating in an interview with RTL, “If I am ahead, I will obviously call for the dissolution of the National Assembly that same evening.”

Dissolution appears as a tool to force the electoral calendar, especially after the 2002 reform of the quinquennat. These electoral cycles are governed by the presidential election and the election of European Parliament members: 2002 and 2004, 2007 and 2009, 2022 and 2024. The duration of the presidential mandate aligns with that of members of the European Parliament in Brussels and Strasbourg. However, the 2002 reform impacts legislative elections, which are now largely seen as confirmation elections of the presidential choice, carrying significant weight.

Moreover, we observe a decline in voter participation for legislative elections, with abstention rates rising from 35 to 52% in the first round between 2002 and 2022. In contrast, voter participation rates in European elections have relatively increased: 40% in 2009, 42% in 2014, 50% in 2019, and 52% in 2024 (Harmsen and Schild, 2011). The latter observation reveals the rise of populist parties and the defeat of traditional parties and the parliamentary majority in the last three elections.

Thus, we can consider European elections as “mid-terms,” i.e., intermediate elections whose stakes are crucial for both the ruling power and populist parties. This is confirmed by populist leaders: Bardella stated that EU elections “are first and foremost mid-term elections” (2024). For Mélenchon (2024), leader of LFI: “Yes, the 2024 European election prepares the 2027 presidential election.” The researcher and professor Perrineau (2024) analyzed this by stating, “The attempt and temptation (…) is strong to use European elections as mid-term elections, as we say in the U.S., ‘mid-term elections,’ where voters express dissatisfaction with the current ruling team. Of course, the far-right plays a significant role when they are not in power.”

The dissolution of the National Assembly is thus a response by Macronist power to the results of the European elections, as if they carried the weight of a referendum. Certainly, dissolution poses a risk for Macron and his government, but it is part of a democratic process that echoes de Gaulle’s famous “I have heard you” policy. Macron’s decision confirms that these national stakes turn European elections into a matter of primary importance.

While European elections are still, in part, second-order elections, they are increasingly becoming moments where voters express a genuine European choice—whether in favor of further integration or critical of the EU (Hobolt and Spoon, 2012). In this context, it means that parties have positioned themselves on European issues, and citizens’ choices have been shaped by these positions regarding the EU and European integration. For example, regarding France’s role in Europe and the world, 20% of French voters believe this issue is decisive in their voting choice, while 24% believe the same issue has been addressed by candidates and the media (Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne, 2024).

Therefore, it is important not to underestimate the fact that while many Eurosceptic deputies have entered the European Parliament since 2014, this continuity—both in 2019 and 2024—demonstrates that voters made a choice regarding European integration—whether Europhilic or Eurosceptic. Notably, 38% of French voters had a positive image of the EU in 2023 [compared to 44% of Europeans (European Commission, 2023a, 2023b)], and attachment to the EU has been gradually increasing (55%, +2 points).

Indeed, according to the Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne (2024, p. 41–43) study, 53% of French voters primarily consider the parties’ proposals when determining their voting choice (51% in 2019). A remarkable 87% of French voters are motivated to vote due to the ideas and proposals of the parties (99% of LFI voters, 93% of Renaissance voters, and 94% of RN voters). Additionally, 81% of voters are motivated by the presence and actions of party members in the European Parliament (87% of LFI voters, 89% of Renaissance voters, and 77% of RN voters).

This data highlight the importance of European issues in shaping voter behavior, suggesting that voters are influenced by parties’ positions on the EU and European integration. The high percentage of motivated voters (87%) reflects the significant role of party platforms in mobilizing voters. Among these, 99% of LFI voters are the most motivated by party ideas, indicating strong alignment with their policy agenda. Voters highly value their party’s activity in the European Parliament, showcasing their influence at the EU level.

The findings underscore the central role of European issues in shaping electoral dynamics in France. The strong alignment of voters with party proposals and actions within the EU highlights the increasing politicization of European integration in domestic elections. Parties that clearly position themselves on European matters and demonstrate effectiveness in the European Parliament are better equipped to engage and mobilize their constituencies.

Parties with distinct and well-articulated stances on the EU are more capable of connecting with their electorate. The importance of party actions in the European Parliament emphasizes the need for a visible and effective presence in EU institutions. The data reveals that both pro-European and Eurosceptic parties can mobilize voters effectively when their narratives align with the electorate’s priorities.

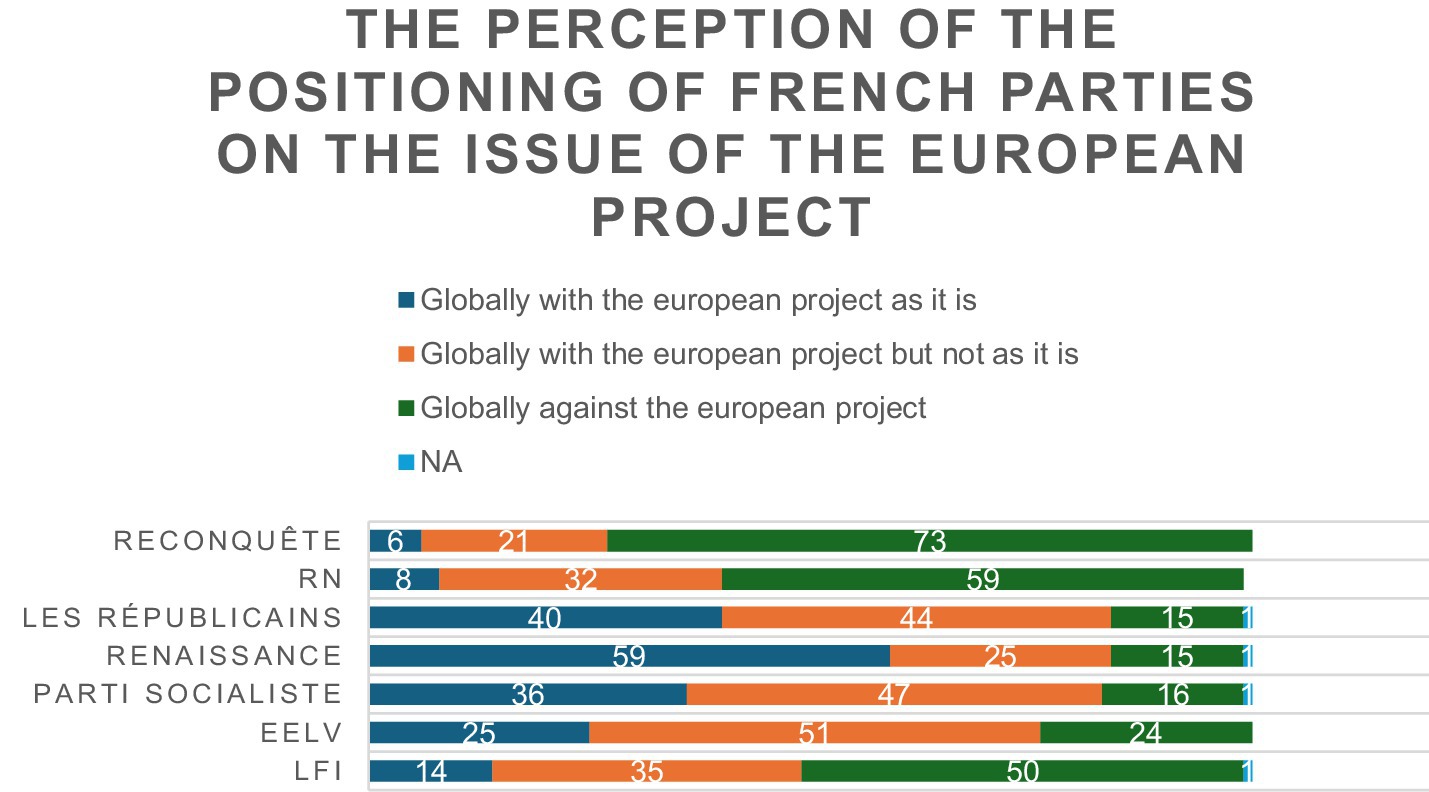

Indeed, as of May 2024, French voters believe (Figure 3) that populist parties such as LFI, RN, and Reconquête are generally unfavorable towards the European project. According to the same survey, 21% of French voters support the European project as it stands, while 22% are opposed to it (Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne, 2024).

Figure 3. The Perception of the positioning of French Parties on the issue of the European Project. Note. This chart summarizes the answers to the Question: “And would you say that each of the following parties is rather…? Data are retrieved from Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne (2024), p. 71.

We argue that in 2024, the electoral choice is fundamentally “European,” dependent on citizens’ attitudes toward European integration. Thus the anti-European is characterized by its euroscepticism and a definition of Europe à la carte. It is no longer a rejection of the EU, but the adoption of new choices more sovereign and less supranational (Harmsen, 2005). Indeed, the RN party’s platform is more Eurosceptic than outright anti-European. In the 2024 RN/Patriote.EU program (Rassemblement National, 2024), the party acknowledges its attachment to Europe, referring to it as “our European home,” but rejects the EU as it is currently perceived—namely, “distant and unknown institutions that are far removed from European citizens, along with powerful globalist forces, unelected bureaucrats, lobbies, and interest groups that disregard the voice of the majority and popular democracy, aiming to replace nations with a central European state.” The RN thus rejects an EU that undermines state sovereignty, advocating for a reduction in the supranational powers of EU institutions. This can be analyzed as partisan Euroscepticism (Szczerbiak, 2008; Szczerbiak and Taggart, 2008). Here, opposition to Europe is framed as a tool for competition rather than a core attribute (Dakowska, 2010). This Europeanization of discourse builds upon existing FN arguments, emphasizing a traditionalist valorization of the nation (Boily, 2005), denouncing a “superstate” Europe, rejecting “Euro-globalism,” criticizing immigration, and challenging the left–right political divide.

These two approaches – the nationalization of European elections and the European choice – confirm Reif and Schmitt's (1980) thesis on analyzing European elections as “second-order national elections,” a relevance that persists three decades later (Schmitt and Toygür, 2016). Indeed, factors such as the electoral cycle, party characteristics, and national political climates significantly impact EP election results (van Egmond, 2005; Schmitt and Toygür, 2016). The 2024 elections took place in an economic and political context where European integration was seen as a critical issue that must be reinforced according to new criteria. Hence, the nationalization of elections represents a reinforcement of the role of states in EU reform, both in terms of institutions and integration policies. Both Le Pen and Macron addressed a vision of Europe’s future:

« Nous, les forces patriotiques d’Europe, nous engageons à redonner l’avenir de notre continent aux peuples d’Europe, à reprendre nos institutions et à réorienter la politique européenne au service de nos nations et de nos peuples. » [“We, the patriotic forces of Europe, commit to giving the future of our continent back to the peoples of Europe, to reclaim our institutions, and to redirect European policy to serve our nations and our peoples”] (Rassemblement National, 2024).

« Nous proposons alors de bâtir une Europe plus unie, plus souveraine, plus démocratique. » [“We propose to build a more unified, more sovereign, more democratic Europe”] (Macron, 2024).

The European Parliament elections, initially intended to establish a direct link between citizens and EU decision-making (Navarro, 2009). The EU has evolved into a political order with its own action capacity, transforming governance beyond the state framework (Jachtenfuchs, 2001). This multi-level system of governance raises questions about legitimacy and efficiency in decision-making processes. While the EU has broad political competencies, the application of traditional governance concepts remains challenging, necessitating further research on institutional models and the effects of Europeanization on member states’ governance structures (Jachtenfuchs, 2001).

Indeed, since 2019 and for the first time in the history of European integration, the left and right governing blocs no longer hold, together, an absolute majority of seats in the European Parliament. This has resulted in more complex parliamentary majorities, which are expected to enrich the debate (Brack and Marié, 2024). According to Article 14–2 of the Treaty on the European Union, the European Parliament is composed of representatives of the citizens of the Union. The European Parliament is therefore not characterized by a two-party system and operates primarily through majority coalitions. The Far-right is thus Europeanized (Reungoat, 2014).

The European Parliament is thus a political forum for many protest movements, whether eurosceptic or simply bearers of visions (Roa Bastos, 2024).

The results of the 2024 European elections have essentially confirmed the electoral consolidation of the populist phenomenon in Europe, mainly the populist right (Gauthier, 2007; Ivaldi and Zankina, 2024). In 2024, these parties won 263 of the 720 seats – approximately 36%. Populists came first in the elections in six countries, with radical right populists winning in four countries. The new European Parliament centre of gravity has clearly shifted to the right, phenomenon that has growing influence on political debates and policy decisions in areas such as migration, climate change, EU enlargement, and support for Ukraine. The Populists’ Potential Influence in the European Parliament with 33.3–49.9% of Seats can be analyzed through five approaches.

The key focus is on how the division within the mainstream can either empower or limit populist influence.

The first impact is on the constitution of the EP. By preventing an absolute majority, populists can obstruct the election of important leadership roles, such the president of the European Parliament, if the mainstream is split. Populists can also limit the overall power of mainstream candidates by influencing the election of a leading candidate (Spitzenkandidat) for the European Commission.

The second effect is on the control of the European Commission. It takes a third of the EP seats to undermine the College of Commissioners’ political mandate or make it more difficult to nominate them. The legitimacy of the Commission may be impacted by populists’ influence over commissioner-designates’ approval.

Third, particularly under regular parliamentary procedures, populists have the power to sabotage or impede the legislative process, changing or delaying the legislative procedure. Additionally, they have the ability to undermine the EU’s foreign relations by influencing important EU international accords through the consent procedure.

Fourth, Populists can influence the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) and its related programs, affecting budget allocations. With enough seats, populists can block the rule-of-law mechanism under Article 7, which is designed to ensure EU countries uphold democratic principles.

Finally, if populists hold a significant portion of seats, they can influence the content of the European Parliament’s non-binding opinions or resolutions. A wide coalition might be required to counter their influence effectively.

Voters primarily view their participation in EU elections through a national lens, according to the nationalization of these elections. This can cause division in the European Parliament, where the conversation is shaped by more regional, national issues. The creation of a European political identity, which is a prerequisite for further European integration, may be hampered by this trend as the EU develops. In order to strengthen European identity and guarantee that European elections represent the varied political environments across member states, institutional adjustments could be necessary.

Policymakers may need to reconsider how European electoral systems are designed when EU elections start to resemble national elections more and more. To better reflect national political realities, proportional representation, for example, may be strengthened. However, the system could also be redesigned to promote transnational party alliances that prioritize European issues. This could assist in striking a balance between national interests and the EU’s overall objectives.

This would also help to lower euroskeptical behavior in the EU. Indeed, Euroskepticism can lead to institutional challenges. The adoption of important initiatives, like the Green Deal or a unified military strategy, may be delayed if euroskeptic parties in the European Parliament place more emphasis on reversing European integration than promoting it. To balance the desire for autonomy with the necessity of collective action, the EU may need to think about institutional changes that take these shifting dynamics into account, like encouraging a more transparent communication between the European Parliament and national governments. The effectiveness of the European Parliament may be weakened if it is seen as a platform for domestic politics rather than a legitimate legislative body. The European Parliament’s capacity to implement pan-European policies may be jeopardized if it is consistently viewed as a forum for national political agendas. This might lead to demands for the European Parliament to be reformed so that it serves as a truly representative body for all EU people instead of merely acting as a battlefield for national politics.

To combat Euroskepticism and capitalize on the growing involvement of far-right parties, the European Union will need to create more complex policies. This would entail encouraging more robust communication initiatives to outline the advantages of EU membership, particularly by emphasizing achievements like security cooperation, environmental preservation, and economic growth. By strengthening its policymaking in areas like immigration, labor rights, and economic inequality—where Euroskeptic parties frequently find fertile ground for their messages—the EU may also need to be more sensitive to the concerns of its citizens.

The study suggests that many Europeans are still disengaged from European politics, especially when it comes to the ways that EU policies affect their day-to-day lives.

If populists are perceived as the winners of the 2024 European elections, it is important to note that citizens’ opinions regarding European integration are increasingly manifested through abstention. Since the beginning of European elections, abstention can be analyzed as a reflection of the EU’s inability to mobilize voters (Steed, 1984; Chaussier and Labayle, 1995).

Belot and Van Ingelgom (2015) analyzed the 2014 European elections and demonstrated that:

• Voters abstain, especially for European reasons.

• Voting for a party different from one’s usual preference is not solely a form of protest against incumbent political forces but also reflects either support or rejection (or even ambivalence and distrust) toward the EU and the integration process.

In 2024, abstention in France stood at nearly 48%, and should be analyzed as a form of European abstention rather than a “traditional” one (considered as a sanction of national government. The protest vote and abstention reflect this disillusionment and disagreement with the government’s policies as such), given that both the RN and LFI do not advocate for withdrawal from the EU, but rather for a more social and sovereign Europe. Eurosceptic citizens, who hold negative opinions or seek the restoration of national sovereignty, often prefer abstention rather than voting, even for parties that are closest to their views.

The perception that European integration is not a significant issue in the European elections—neither for parties nor voters—was already noted at the beginning of the European democratic process (Menke and Gordon, 1980), due to voters’ lack of knowledge and the limited media visibility (Lodge, 1979; de Vreese et al., 2018). However, in 2024, national, European, and international media were highly engaged in making these elections visible. In France, for instance, a televised debate between former Prime Minister Gabriel Attal and RN candidate Jordan Bardella took place on May 23, 2024, contributing to the nationalization of European elections. According to Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne (2024), 58% of French citizens relied on television as their primary source of information about the European campaign, while 57% of young people preferred social media.

At the same time, while French citizens initially showed interest and hope for the European elections during the campaign, this shifted to disappointment (Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne, 2024).

If European elections offer voters a chance to express themselves, 62% of French voters believe they are ineffective in making their voices heard, in contrast to municipal elections, where 63% consider them effective (Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne, 2024).

This is partly explained by the “democratic deficit” that Europe suffers from, which is at least partially due to a “knowledge deficit,” leading to a decline in civic competence among the French population. In 2023, European politics remain largely unknown to the French population: two-thirds of respondents (68%) consider themselves poorly informed about European issues (European Commission, 2023a, 2023b, October–November, 20). By comparison, in 2007, only 18% of French respondents felt “very well” or “fairly well” informed about European political affairs, while 80% felt they were “not very well” or “not at all” informed. However, to address what appears to be a lack of information, 89% of French citizens support teaching the functioning of European institutions in schools (Cautrès, 2007). The lack of knowledge can also explain the low levels of trust in the European Parliament: 41% of French citizens expressed confidence in the EP in May 2024 (Ipsos – CEVIPOF – LE MONDE – FJJ – Institut Montaigne, 2024, p. 73–74), which has contributed to the radicalization of the French vote toward populist extremes in the 2024 European elections.

Should this “knowledge deficit” be seen as an epiphenomenon at the level of EU member states, tied to the “myth of the active citizen” (Rosanvallon, 2004). Voting is the most visible and institutional form of citizenship. Democracy of expression corresponds to society’s voice, the formulation of judgments on rulers and their actions, and the expression of demands.

In response, political parties and the EU ought to make more investments in voter education initiatives that emphasize the importance of the European elections. To increase awareness of the significance of EU involvement, these initiatives could involve media campaigns, outreach at colleges and universities, and cooperation with neighborhood organizations.

European elections, so that they have a real impact on the European decision-making process – dominated by the monopoly of the initiative of the European Commission and the co-decision procedure between the Parliament and the European Council, must be transnational. This means transforming the EU into “a transnational public space” such as recommended by Habermas (2012): “This political identity, from which Europe cannot dispense if it is to acquire the capacity for action, can only be forged in a transnational public space” (2006, 44). This means at first an emphasis on the necessity to create and to integrate the European identity in the political discourse and the political practices – namely during the elections; which was completely absent during the 2024 elections (Maloigne, 2024). The EU identity would encourage the creation of a “European demos” (Costa, 2022, 15) to integrate EU citizens into a human group making its decisions collectively for certain issues of general interest.

This means at second that the EU Commission and Parliament should build a primarily virtual arena where citizens from all EU Member States can participate in activities primarily connected to EU decision-making (Martines, 2023). These areas are particularly noteworthy because they allow EU citizens to publicly express their opinions and make their voices heard on all topics of EU action. They also help to strengthen principles like transparency, participation, and control, which are essential to a polity’s democratic life, albeit in a limited way. The Citizens’ Engagement Platform that are already implemented by the EU Commission is an informal space where citizens are selected randomly among the citizens of the 27 member States. In our case, the transnational space of expression would be effective with the creation of transnational European parties and not only lists that are involving the citizens only on the national level. The European parties should be transnational, with candidates and elected EMPs from the 27 member States. The Final Report on the Future of Europe published by the European Union Council (2022) mentioned in that sense: ““the Union’s electoral law in order to harmonize the modalities of the European elections […], moving towards pan-European or transnational lists” (2022, 85). The proposal goes further, suggesting to elect some deputies on the basis of transnational lists and some other on the basis of national lists (European Union Council, 2022, p. 85–86).

Transnational lists would help to engage a more EU centered dialog and program rather than a national dialog on national issues. This would contribute to a more Europeanization, that aligns with Ladrech (2002) two following types:

• “downloading, which implies a pressure on EU member states’ policies and governmental structures to adapt to EU standards,” and;

• “cross-loading, whereby the EU creates frames for the member states to exchange best practices and experiences, with little or no involvement from the institutions” (Dosenrode, 2020).

It is within national spaces that the European issue is constructed (Taggart and Szczerbiak, 2008; Neumayer, 2008) which is why organizational European positions are evolving and discourses on Europe must be contextualized with national competition frameworks to be understood. Therefore, the populist MEPs are European MEPs: “Eurodeputies are […] ‘European’ and not merely national lawmakers serving in a European institution” (Beauvallet and Michon, 2010, p. 147). While threatening the internal democracy of the EU, they are catalysts that oblige the EU to rethink the process of Europeanization based on the strategy of “cross-loading” and strengthening this process (Ladrech, 2002) and to view the European Parliament no more as a “‘second-tier’ parliament” (Corre-Basset, 2023, p. 420).

Finally, according to the Report on the Future of Europe (2022), “European citizens should have more weight in the election of the Commission President. This objective could be materialized through direct election of the President of the Commission or system of candidates heads of list” (2022, 86). This system of the first candidate is based on Article 17 § 7 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) which stipulates that the European Council, “taking into account the elections to the European Parliament […] shall propose to the European Parliament a candidate for the office of President of the Commission.”

Although the heads of state and government have no obligation to take this system into account when designating their next candidate for the presidency of the Commission, the main European parties have nevertheless selected one or more candidates to run for the head of the executive. The question here would if – in respect of the democratic process in the EU – the President of the Commission who should be elected would be from the head of the majority in the Parliament. The reelection of Ursula Von der Leyen means – who was designated as a SpitzenKandidat by her list, means tha this strategy is reimplemented (after being abandoned in 2019). Other parties also nominated Spitzenkandidaten for the election. But there is no indication that these names and especially of populist parties - would have been selected for the presidency of the European Commission in case their party won the European elections.

It is important to recognize a number of methodological limitations, even if this study offers insightful information about voter behavior and the dynamics of European elections.